User login

A 4-year-old with a lesion on her cheek, which grew and became firmer over two months

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

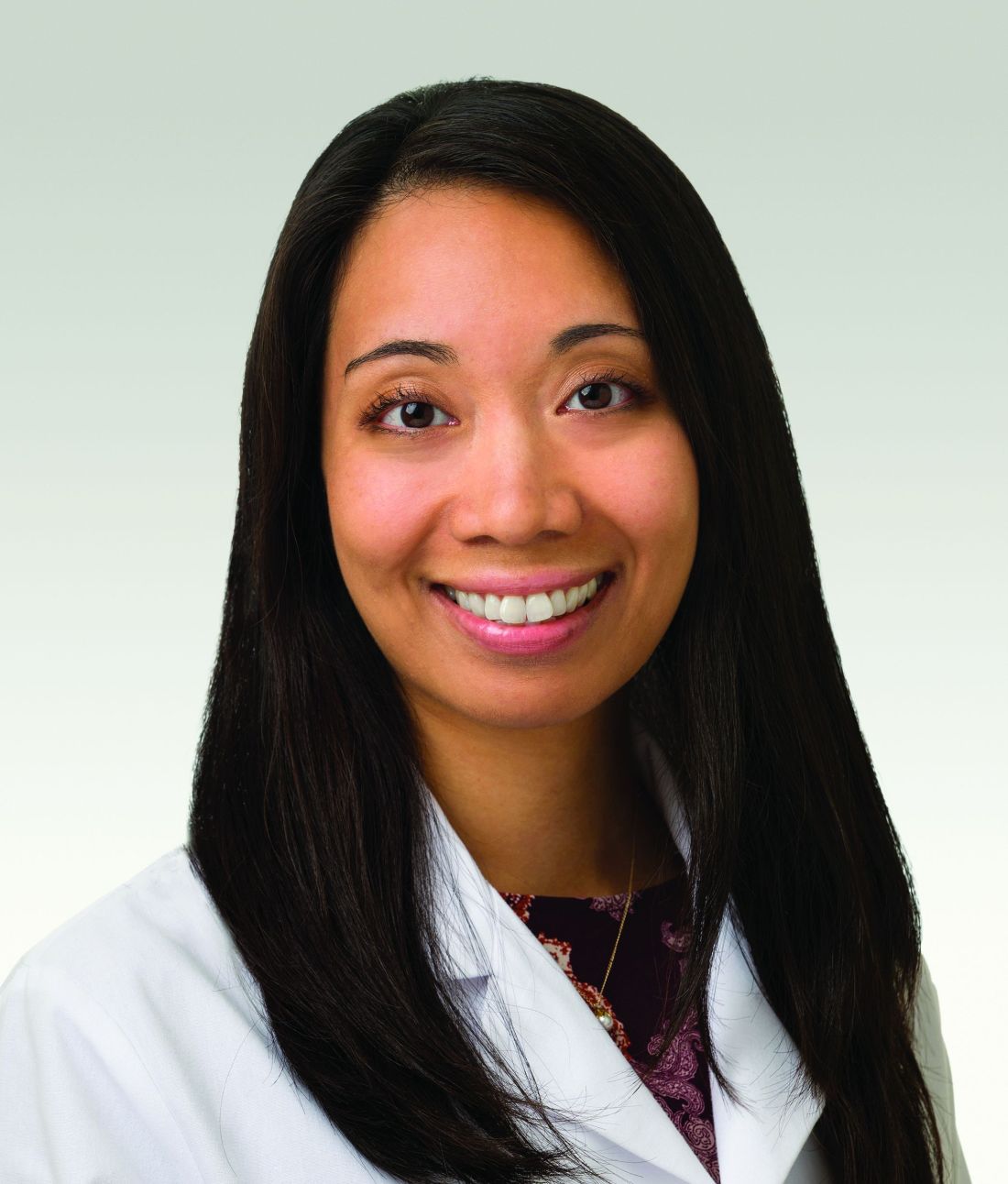

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

A 4-year-old female is brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent lesion on the cheek.

The mother of the child reports that the lesion started as a small "bug bite" and then started growing and getting firmer for the past 2 months. The girl has developed other smaller red, pimple-like lesions on the cheeks and one of them is starting to increase in size.

She denies any tenderness on the area or any purulent discharge. She has had no fevers, chills, weight loss, nose bleeds, fatigue, or any other symptoms. The mother has not noted any changes on the child's body odor, any rapid growth, or hair on her axillary or pubic area. She was treated with three different courses of oral antibiotics including cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and clindamycin, as well as topical mupirocin, with no improvement.

Her past medical history is significant for several episodes of eyelid cysts that were treated with warm compresses and topical erythromycin ointment. The family history is significant for the father having severe acne as a teenager. She has two cats, she has not traveled, and she has an older sister who has no lesions.

On physical examination she is a lovely 4-year-old female in no acute distress. Her height is on the 70th percentile and weight on the 40th percentile for her age. Her blood pressure is 95/84 with a heart rate of 96. On skin examination she has several pink macules and papules on her bilateral cheeks. On the left cheek there are two pink nodules: One is 1 cm, and the other is 7 mm. The nodules are not tender. There is no warmth, fluctuance, or discharge from the lesions.

She has no cervical lymphadenopathy. She has no axillary or pubic hair. She is Tanner stage I.

PHM20 Virtual: Can’t miss heart disease for hospitalists

PHM20 Virtual session title

Can’t Miss Heart Disease for Hospitalists

Presenter

Erich Maul, DO, MPH, FAAP, SFHM

Session summary

Dr. Erich Maul, professor of pediatrics, medical director for progressive care and acute care, and chief of hospital pediatrics at Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, presented an engaging, case-based approach to evaluate heart disease when “on call.” He iterated the importance of recognizing congenital heart disease, especially since 25% of these patients usually need surgical intervention within the first month of diagnosis and about 50% of congenital heart disease patients do not have a murmur.

Presenting cases seen during a busy hospitalist call night, Dr. Maul highlighted that patients can present with signs of heart failure, cyanosis, sepsis or hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, and respiratory distress or failure. He discussed the presentation, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. He also provided examples of common arrhythmias and provided refreshers on management using basic life support (BLS) and pediatric advanced life support.

Key takeaways

- Always start with the nine steps to resuscitation: ABC (airway, breathing, circulation), ABC, oxygen, access, monitoring.

- Early BLS is important.

- Congenital heart disease often presents with either cyanosis, hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, or respiratory distress.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist practicing at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

PHM20 Virtual session title

Can’t Miss Heart Disease for Hospitalists

Presenter

Erich Maul, DO, MPH, FAAP, SFHM

Session summary

Dr. Erich Maul, professor of pediatrics, medical director for progressive care and acute care, and chief of hospital pediatrics at Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, presented an engaging, case-based approach to evaluate heart disease when “on call.” He iterated the importance of recognizing congenital heart disease, especially since 25% of these patients usually need surgical intervention within the first month of diagnosis and about 50% of congenital heart disease patients do not have a murmur.

Presenting cases seen during a busy hospitalist call night, Dr. Maul highlighted that patients can present with signs of heart failure, cyanosis, sepsis or hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, and respiratory distress or failure. He discussed the presentation, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. He also provided examples of common arrhythmias and provided refreshers on management using basic life support (BLS) and pediatric advanced life support.

Key takeaways

- Always start with the nine steps to resuscitation: ABC (airway, breathing, circulation), ABC, oxygen, access, monitoring.

- Early BLS is important.

- Congenital heart disease often presents with either cyanosis, hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, or respiratory distress.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist practicing at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

PHM20 Virtual session title

Can’t Miss Heart Disease for Hospitalists

Presenter

Erich Maul, DO, MPH, FAAP, SFHM

Session summary

Dr. Erich Maul, professor of pediatrics, medical director for progressive care and acute care, and chief of hospital pediatrics at Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, presented an engaging, case-based approach to evaluate heart disease when “on call.” He iterated the importance of recognizing congenital heart disease, especially since 25% of these patients usually need surgical intervention within the first month of diagnosis and about 50% of congenital heart disease patients do not have a murmur.

Presenting cases seen during a busy hospitalist call night, Dr. Maul highlighted that patients can present with signs of heart failure, cyanosis, sepsis or hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, and respiratory distress or failure. He discussed the presentation, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. He also provided examples of common arrhythmias and provided refreshers on management using basic life support (BLS) and pediatric advanced life support.

Key takeaways

- Always start with the nine steps to resuscitation: ABC (airway, breathing, circulation), ABC, oxygen, access, monitoring.

- Early BLS is important.

- Congenital heart disease often presents with either cyanosis, hypoperfusion, failure to thrive, or respiratory distress.

Dr. Tantoco is an academic med-peds hospitalist practicing at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is an instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago.

SGLT2 inhibitors with metformin look safe for bone

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

FROM OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL

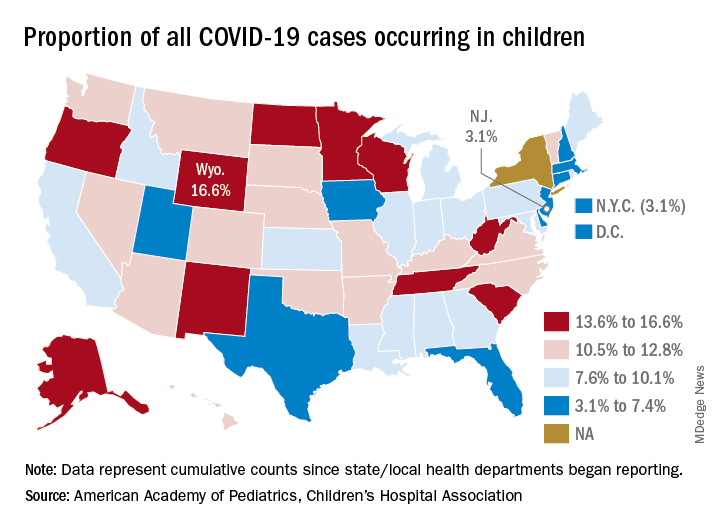

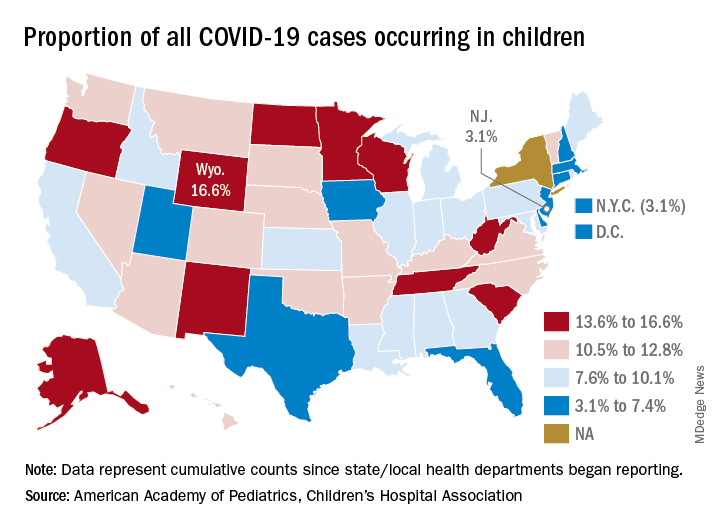

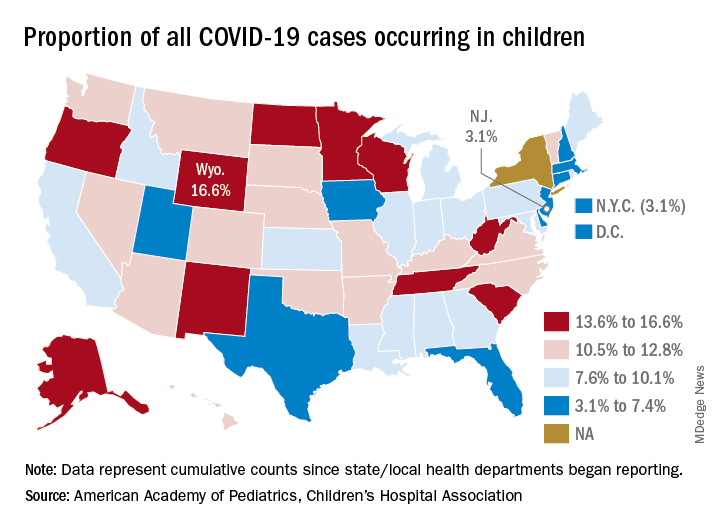

COVID-19 child case count now over 400,000

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

according to a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 406,000 children who have tested positive for COVID-19 represent 9.1% of all cases reported so far by 49 states (New York does not provide age distribution), New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Since the proportion of child cases also was 9.1% on Aug. 6, the most recent week is the first without an increase since tracking began in mid-April, the report shows.

State-level data show that Wyoming has the highest percentage of child cases (16.6%) after Alabama changed its “definition of child case from 0-24 to 0-17 years, resulting in a downward revision of cumulative child cases,” the AAP and the CHA said. Alabama’s proportion of such cases dropped from 22.5% to 9.0%.

New Jersey had the lowest rate (3.1%) again this week, along with New York City, but both were up slightly from the week before, when New Jersey was at 2.9% and N.Y.C. was 3.0%. The only states, other than Alabama, that saw declines over the last week were Arkansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia. Texas, however, has reported age for only 8% of its confirmed cases, the report noted.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases as of Aug. 13 was 538 per 100,000 children, up from 500.7 per 100,000 a week earlier. Arizona was again highest among the states with a rate of 1,254 per 100,000 (up from 1,206) and Vermont was lowest at 121, although Puerto Rico (114) and Guam (88) were lower still, the AAP/CHA data indicate.

For the nine states that report testing information for children, Arizona has the highest positivity rate at 18.3% and West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%. Data on hospitalizations – available from 21 states and N.Y.C. – show that 3,849 children have been admitted, with rates varying from 0.2% of children in Hawaii to 8.8% in the Big Apple, according to the report.

More specific information on child cases, such as symptoms or underlying conditions, is not being provided by states at this time, the AAP and CHA pointed out.

Are aging physicians a burden?

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

HFNC more comfortable for posthypercapnic patients with COPD

Following invasive ventilation for severe hypercapnic respiratory failure, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had similar levels of treatment failure if they received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, recent research in Critical Care has suggested.

However, for patients with COPD weaned off invasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy was “more comfortable and better tolerated,” compared with noninvasive ventilation (NIV). In addition, “airway care interventions and the incidence of nasofacial skin breakdown associated with HFNC were significantly lower than in NIV,” according to Dingyu Tan of the Clinical Medical College of Yangzhou (China) University, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, and colleagues. “HFNC appears to be an effective means of respiratory support for COPD patients extubated after severe hypercapnic respiratory failure,” they said.

The investigators screened patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure for enrollment, including those who met Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, were 85 years old or younger and caring for themselves, had bronchopulmonary infection–induced respiratory failure, and had achieved pulmonary infection control criteria. Exclusion criteria were:

- Patients under age 18 years.

- Presence of oral or facial trauma.

- Poor sputum excretion ability.

- Hemodynamic instability that would contraindicate use of NIV.

- Poor cough during PIC window.

- Poor short-term prognosis.

- Failure of the heart, brain, liver or kidney.

- Patients who could not consent to treatment.

Patients were determined to have failed treatment if they returned to invasive mechanical ventilation or switched from one treatment to another (HFNC to NIV or NIV to HFNC). Investigators also performed an arterial blood gas analysis, recorded the number of duration of airway care interventions, and monitored vital signs at 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours after extubation as secondary analyses.

Overall, 44 patients randomized to receive HFNC and 42 patients randomized for NIV were available for analysis. The investigators found 22.7% of patients in the HFNC group and 28.6% in the NIV group experienced treatment failure (risk difference, –5.8%; 95% confidence interval, −23.8 to 12.4%; P = .535), with patients in the HFNC group experiencing a significantly lower level of treatment intolerance, compared with patients in the NIV group (risk difference, –50.0%; 95% CI, −74.6 to −12.9%; P = .015). There were no significant differences between either group regarding intubation (−0.65%; 95% CI, −16.01 to 14.46%), while rate of switching treatments was lower in the HFNC group but not significant (−5.2%; 95% CI, −19.82 to 9.05%).

Patients in both the HFNC and NIV groups had faster mean respiratory rates 1 hour after extubation (P < .050). After 24 hours, the NIV group had higher-than-baseline respiratory rates, compared with the HFNC group, which had returned to normal (20 vs. 24.5 breaths per minute; P < .050). Both groups had returned to baseline by 48 hours after extubation. At 1 hour after extubation, patients in the HFNC group had lower PaO2/FiO2 (P < .050) and pH values (P < .050), and higher PaCO2 values (P less than .050), compared with baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in PaO2/FiO2, pH, and PaCO2 values in either group at 24 hours or 48 hours after extubation.

Daily airway care interventions were significantly higher on average in the NIV group, compared with the HFNC group (7 vs. 6; P = .0006), and the HFNC group also had significantly better comfort scores (7 vs. 5; P < .001) as measured by a modified visual analog scale, as well as incidence of nasal and facial skin breakdown (0 vs. 9.6%; P = .027), compared with the NIV group.

Results difficult to apply to North American patients

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, a professor specializing in critical care at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview the results of this trial may not be applicable for patients with infection-related respiratory failure and COPD in North America “due to the differences in common weaning practices between North America and China.”

For example, the trial used the pulmonary infection control (PIC) window criteria for extubation, which requires a significant decrease in radiographic infiltrates, improvement in quality and quantity of sputum, normalizing of leukocyte count, a synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) rate of 10-12 breaths per minute, and pressure support less than 10-12 cm/H2O (Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1255-67).

“The process used to achieve these measures is not standardized. In North America, daily awakening and screening for spontaneous breathing trials would be usual, but this was not reported in the current trial,” he explained.

Differences in patient population also make the application of the results difficult, Dr. Bowton said. “Only 60% of the patients had spirometrically confirmed COPD and fewer than half were on at least dual inhaled therapy prior to hospitalization with only one-third taking beta agonists or anticholinergic agents,” he noted. “The cause of respiratory failure was infectious, requiring an infiltrate on chest radiograph; thus, patients with hypercarbic respiratory failure without a new infiltrate were excluded from the study. On average, patients were hypercarbic, yet alkalemic at the time of extubation; the PaCO2 and pH at the time of intubation were not reported.

“This study suggests that in some patients with COPD and respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, HFO [high-flow oxygen] may be better tolerated and equally effective as NIPPV [noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation] at mitigating the need for reintubation following extubation. In this patient population where hypoxemia prior to extubation was not severe, the mechanisms by which HFO is beneficial remain speculative,” he said.

This study was funded by the Rui E special fund for emergency medicine research and the Yangzhou Science and Technology Development Plan. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Bowton reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan D et al. Crit Care. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03214-9.

Following invasive ventilation for severe hypercapnic respiratory failure, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had similar levels of treatment failure if they received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, recent research in Critical Care has suggested.

However, for patients with COPD weaned off invasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy was “more comfortable and better tolerated,” compared with noninvasive ventilation (NIV). In addition, “airway care interventions and the incidence of nasofacial skin breakdown associated with HFNC were significantly lower than in NIV,” according to Dingyu Tan of the Clinical Medical College of Yangzhou (China) University, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, and colleagues. “HFNC appears to be an effective means of respiratory support for COPD patients extubated after severe hypercapnic respiratory failure,” they said.

The investigators screened patients with COPD and hypercapnic respiratory failure for enrollment, including those who met Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, were 85 years old or younger and caring for themselves, had bronchopulmonary infection–induced respiratory failure, and had achieved pulmonary infection control criteria. Exclusion criteria were:

- Patients under age 18 years.

- Presence of oral or facial trauma.

- Poor sputum excretion ability.

- Hemodynamic instability that would contraindicate use of NIV.

- Poor cough during PIC window.

- Poor short-term prognosis.

- Failure of the heart, brain, liver or kidney.

- Patients who could not consent to treatment.

Patients were determined to have failed treatment if they returned to invasive mechanical ventilation or switched from one treatment to another (HFNC to NIV or NIV to HFNC). Investigators also performed an arterial blood gas analysis, recorded the number of duration of airway care interventions, and monitored vital signs at 1 hour, 24 hours, and 48 hours after extubation as secondary analyses.

Overall, 44 patients randomized to receive HFNC and 42 patients randomized for NIV were available for analysis. The investigators found 22.7% of patients in the HFNC group and 28.6% in the NIV group experienced treatment failure (risk difference, –5.8%; 95% confidence interval, −23.8 to 12.4%; P = .535), with patients in the HFNC group experiencing a significantly lower level of treatment intolerance, compared with patients in the NIV group (risk difference, –50.0%; 95% CI, −74.6 to −12.9%; P = .015). There were no significant differences between either group regarding intubation (−0.65%; 95% CI, −16.01 to 14.46%), while rate of switching treatments was lower in the HFNC group but not significant (−5.2%; 95% CI, −19.82 to 9.05%).

Patients in both the HFNC and NIV groups had faster mean respiratory rates 1 hour after extubation (P < .050). After 24 hours, the NIV group had higher-than-baseline respiratory rates, compared with the HFNC group, which had returned to normal (20 vs. 24.5 breaths per minute; P < .050). Both groups had returned to baseline by 48 hours after extubation. At 1 hour after extubation, patients in the HFNC group had lower PaO2/FiO2 (P < .050) and pH values (P < .050), and higher PaCO2 values (P less than .050), compared with baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in PaO2/FiO2, pH, and PaCO2 values in either group at 24 hours or 48 hours after extubation.