User login

Eosinophilic esophagitis: Frequently asked questions (and answers) for the early-career gastroenterologist

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

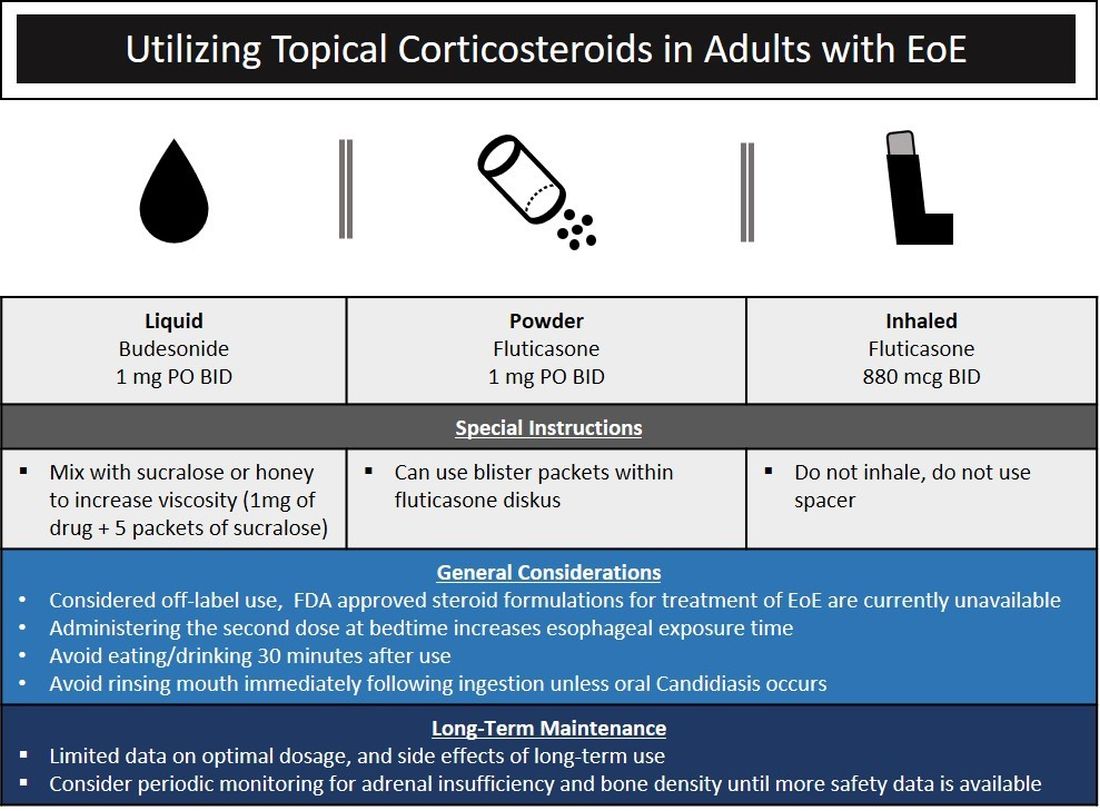

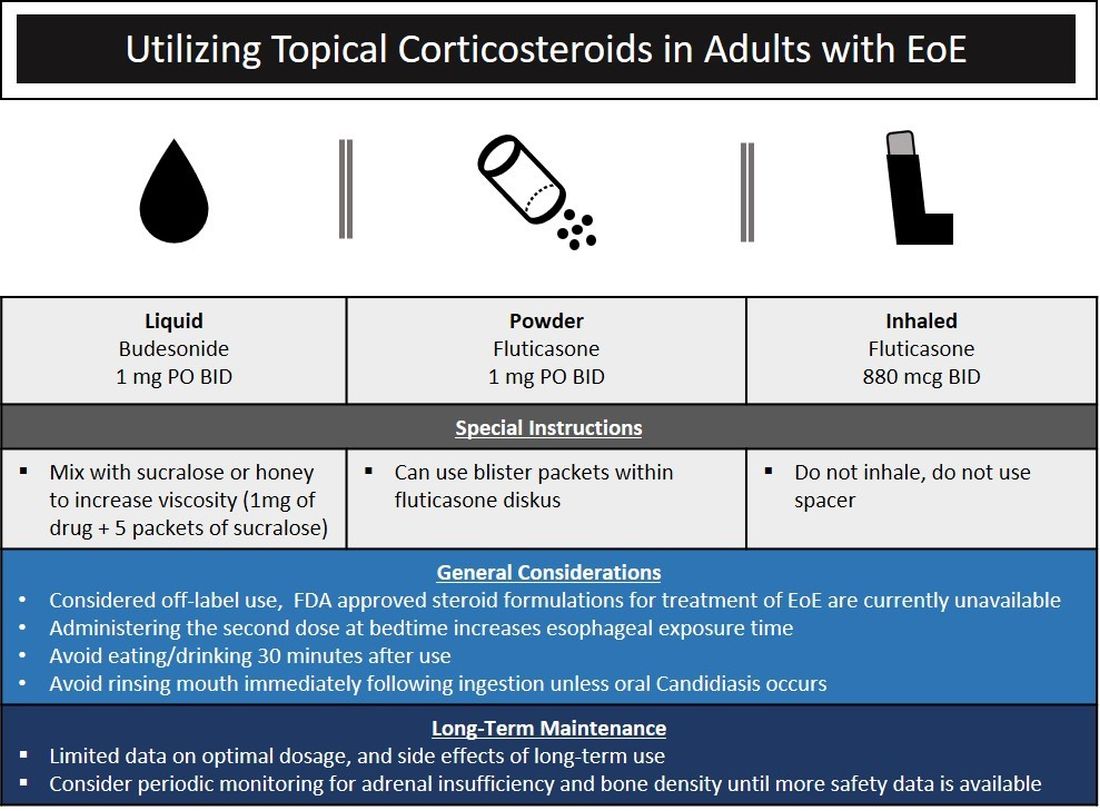

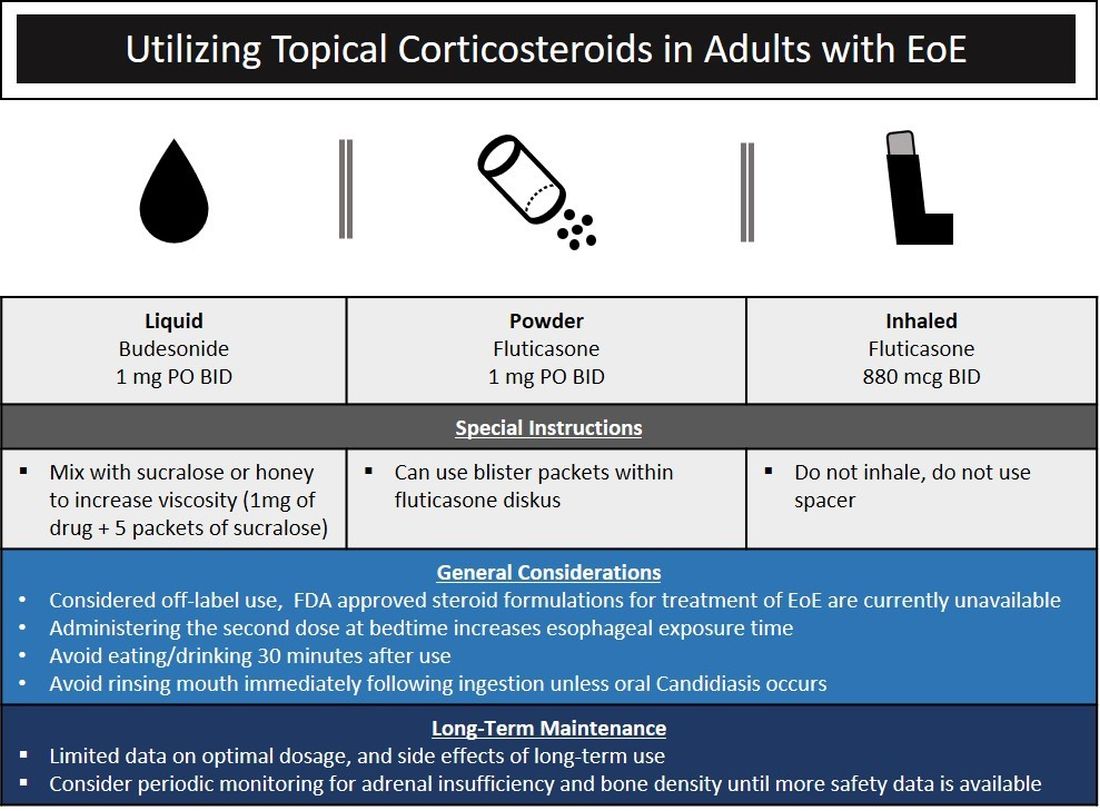

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

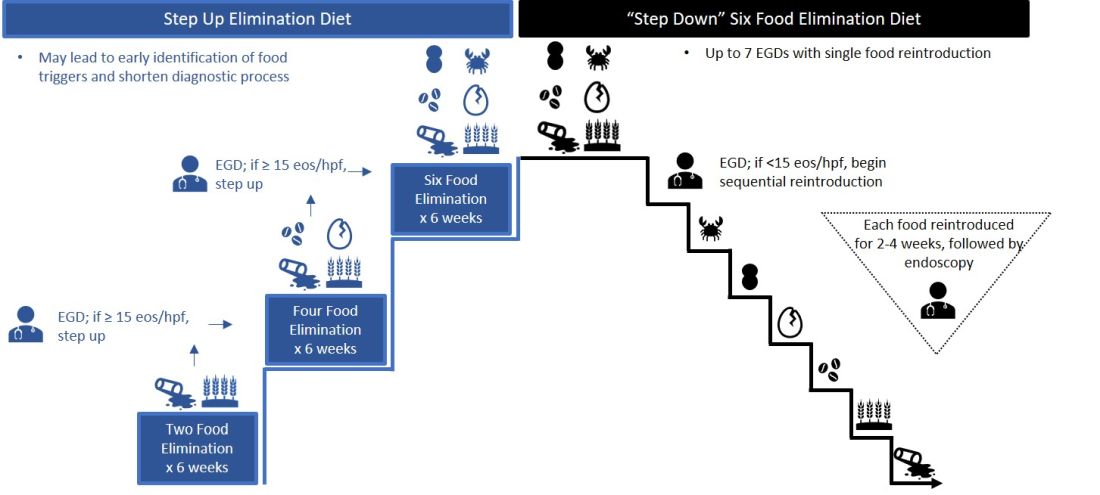

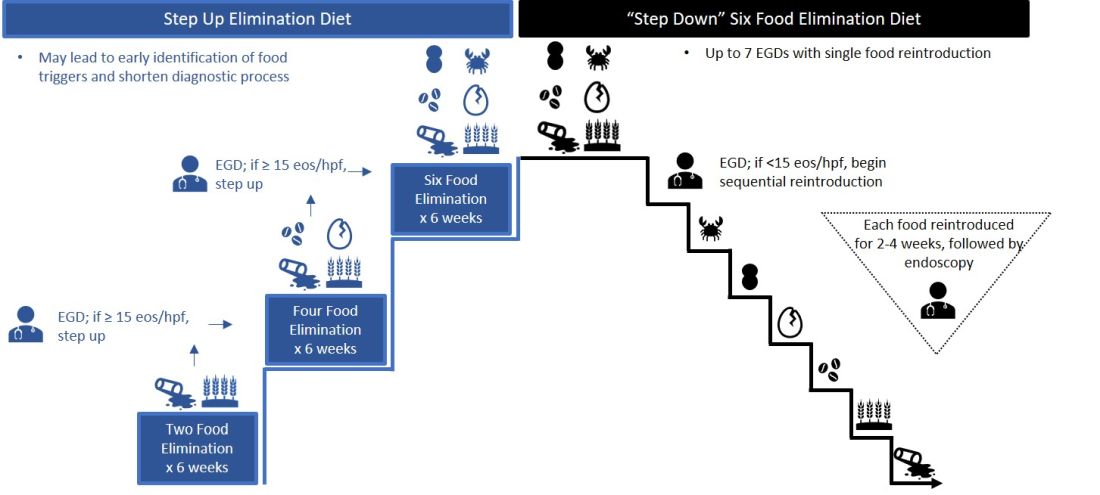

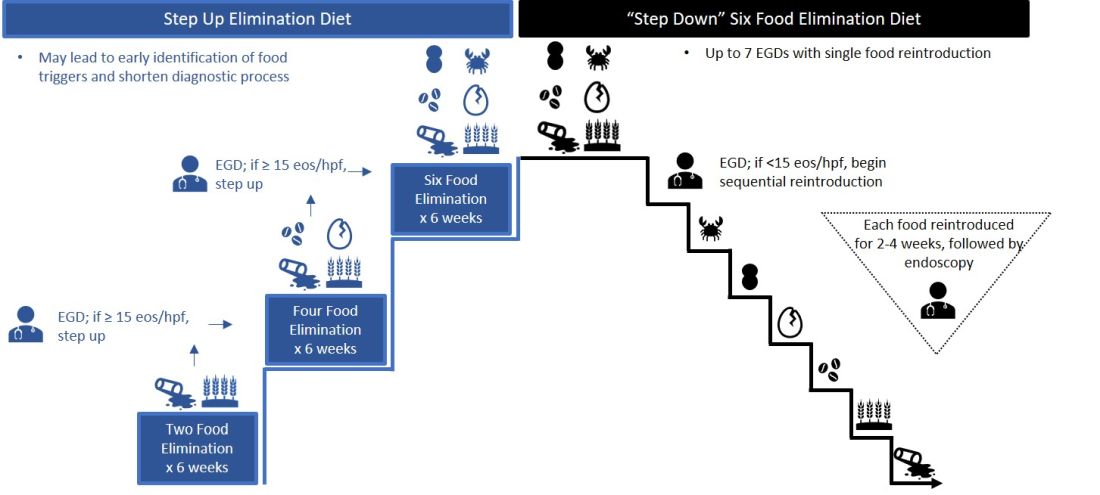

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

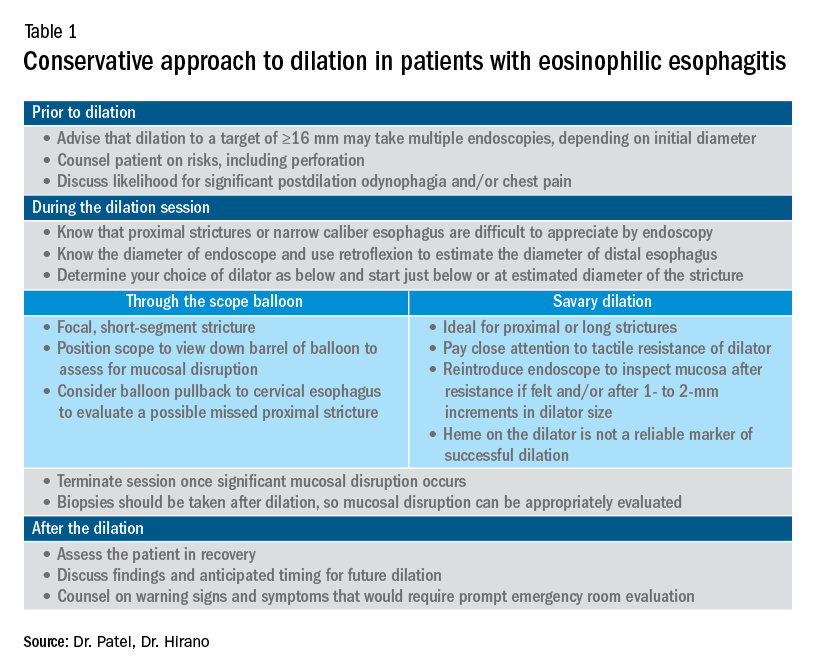

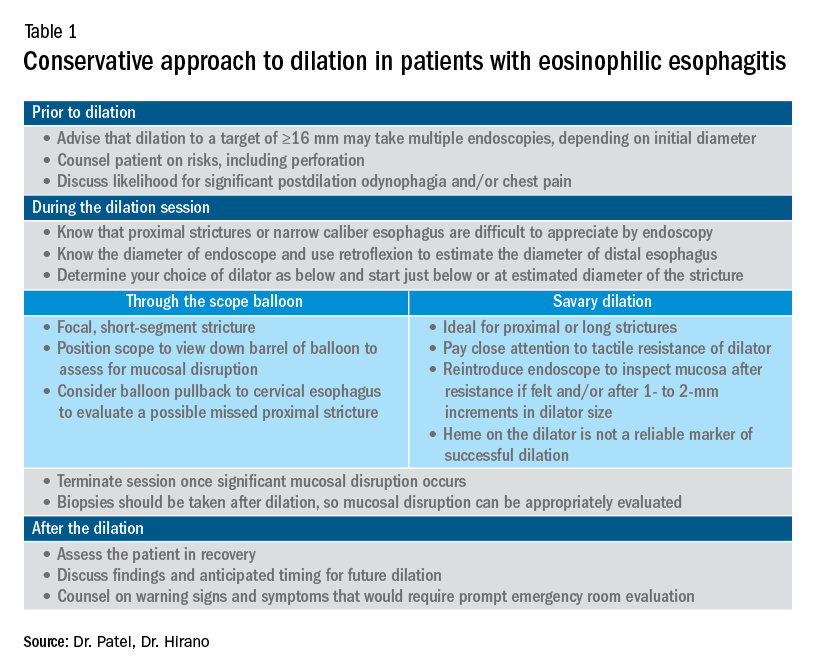

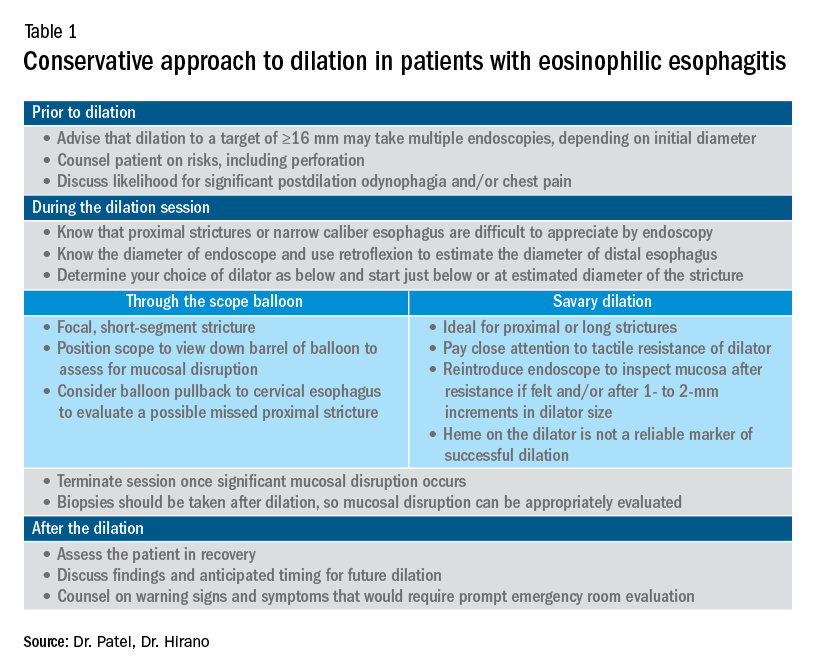

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.

4. Furuta GT et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

5. Liacouras CA et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20 e6; quiz 1-2.

6. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022-33 e10.

7. Hirano I et al. Gut. 2013;62:489-95.

8. Rank MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1789-810 e15.

9. Arias A et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639-48.

10. Molina-Infante J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1365-72.

11. Gentile N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333-40.

12. Hirano I. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:601-6.

13. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1776-86.

14. Collins MH et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-8.

15. Furuta GT et al. Gut. 2013;62:1395-405.

16. Katzka DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77-83 e2.

17. Kwiatek MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82-90.

18. Nicodeme F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1101-7 e1.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.

4. Furuta GT et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

5. Liacouras CA et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20 e6; quiz 1-2.

6. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022-33 e10.

7. Hirano I et al. Gut. 2013;62:489-95.

8. Rank MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1789-810 e15.

9. Arias A et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639-48.

10. Molina-Infante J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1365-72.

11. Gentile N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333-40.

12. Hirano I. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:601-6.

13. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1776-86.

14. Collins MH et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-8.

15. Furuta GT et al. Gut. 2013;62:1395-405.

16. Katzka DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77-83 e2.

17. Kwiatek MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82-90.

18. Nicodeme F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1101-7 e1.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.

4. Furuta GT et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

5. Liacouras CA et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20 e6; quiz 1-2.

6. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022-33 e10.

7. Hirano I et al. Gut. 2013;62:489-95.

8. Rank MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1789-810 e15.

9. Arias A et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639-48.

10. Molina-Infante J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1365-72.

11. Gentile N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333-40.

12. Hirano I. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:601-6.

13. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1776-86.

14. Collins MH et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-8.

15. Furuta GT et al. Gut. 2013;62:1395-405.

16. Katzka DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77-83 e2.

17. Kwiatek MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82-90.

18. Nicodeme F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1101-7 e1.

Letter from the Editor: Stay safe and, please, wear a mask

“Beginning immediately, the University of Michigan will require all students, staff, faculty, and visitors to wear a face covering that covers the mouth and nose while anywhere on campus grounds.” (Mark S. Schlissel MD, PhD – President, University of Michigan – July 15).

Executive Order 2020-147 (Michigan’s Governor Whitmer) mandated appropriate facial covering for all indoor spaces and crowded outdoor spaces. Additionally, businesses will be held responsible if they allow entry to anyone not wearing a mask.

While enforcement is proving to be a nightmare, masking combined with social distancing, hand washing, and staying home are the only effective levers we have to slow the spread of COVID-19. As of today, 138,000 Americans have died, and we anticipate 240,000 deaths by November 1. By now, most of us (myself included) have had a friend or relative die of this virus. America is not winning this battle and we have yet to see an effective, coordinated national response. Four forces are killing our citizens: COVID-19, structural racism, economic/health inequities, and divisive politics. We should do better.

Although Michigan and Minnesota (my home states) have slowed the virus enough to maintain resource capacity, just last weekend a single house party in a suburb near Ann Arbor resulted in 40 new infections. Thirty-nine states have rising case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths. We are still in the early innings of this game. Michigan Medicine is actively planning our response to a second surge, which will be combined with increases of influenza and RSV infections.

This month we continue to cover the rapidly emerging information about COVID-19 and digestive implications. There are other interesting articles, including guidance around BRCA risk for colorectal cancer, eosinophilic esophagitis, probiotics, and the emerging impact of AI on endoscopy. Enjoy – stay safe, wash hands, socially distance, and please, wear a mask.

“Respect science, respect nature, respect each other” (Thomas Friedman).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

“Beginning immediately, the University of Michigan will require all students, staff, faculty, and visitors to wear a face covering that covers the mouth and nose while anywhere on campus grounds.” (Mark S. Schlissel MD, PhD – President, University of Michigan – July 15).

Executive Order 2020-147 (Michigan’s Governor Whitmer) mandated appropriate facial covering for all indoor spaces and crowded outdoor spaces. Additionally, businesses will be held responsible if they allow entry to anyone not wearing a mask.

While enforcement is proving to be a nightmare, masking combined with social distancing, hand washing, and staying home are the only effective levers we have to slow the spread of COVID-19. As of today, 138,000 Americans have died, and we anticipate 240,000 deaths by November 1. By now, most of us (myself included) have had a friend or relative die of this virus. America is not winning this battle and we have yet to see an effective, coordinated national response. Four forces are killing our citizens: COVID-19, structural racism, economic/health inequities, and divisive politics. We should do better.

Although Michigan and Minnesota (my home states) have slowed the virus enough to maintain resource capacity, just last weekend a single house party in a suburb near Ann Arbor resulted in 40 new infections. Thirty-nine states have rising case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths. We are still in the early innings of this game. Michigan Medicine is actively planning our response to a second surge, which will be combined with increases of influenza and RSV infections.

This month we continue to cover the rapidly emerging information about COVID-19 and digestive implications. There are other interesting articles, including guidance around BRCA risk for colorectal cancer, eosinophilic esophagitis, probiotics, and the emerging impact of AI on endoscopy. Enjoy – stay safe, wash hands, socially distance, and please, wear a mask.

“Respect science, respect nature, respect each other” (Thomas Friedman).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

“Beginning immediately, the University of Michigan will require all students, staff, faculty, and visitors to wear a face covering that covers the mouth and nose while anywhere on campus grounds.” (Mark S. Schlissel MD, PhD – President, University of Michigan – July 15).

Executive Order 2020-147 (Michigan’s Governor Whitmer) mandated appropriate facial covering for all indoor spaces and crowded outdoor spaces. Additionally, businesses will be held responsible if they allow entry to anyone not wearing a mask.

While enforcement is proving to be a nightmare, masking combined with social distancing, hand washing, and staying home are the only effective levers we have to slow the spread of COVID-19. As of today, 138,000 Americans have died, and we anticipate 240,000 deaths by November 1. By now, most of us (myself included) have had a friend or relative die of this virus. America is not winning this battle and we have yet to see an effective, coordinated national response. Four forces are killing our citizens: COVID-19, structural racism, economic/health inequities, and divisive politics. We should do better.

Although Michigan and Minnesota (my home states) have slowed the virus enough to maintain resource capacity, just last weekend a single house party in a suburb near Ann Arbor resulted in 40 new infections. Thirty-nine states have rising case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths. We are still in the early innings of this game. Michigan Medicine is actively planning our response to a second surge, which will be combined with increases of influenza and RSV infections.

This month we continue to cover the rapidly emerging information about COVID-19 and digestive implications. There are other interesting articles, including guidance around BRCA risk for colorectal cancer, eosinophilic esophagitis, probiotics, and the emerging impact of AI on endoscopy. Enjoy – stay safe, wash hands, socially distance, and please, wear a mask.

“Respect science, respect nature, respect each other” (Thomas Friedman).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

COVID-19–related skin changes: The hidden racism in documentation

Belatedly, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on patients of color is getting attention. By now, we’ve read the headlines. Black people in the United States make up about 13% of the population but account for almost three times (34%) as many deaths. This story repeats – in other countries and in other minority communities.

Early detection is critical both to initiate supportive care and to isolate affected individuals and limit spread. Skin manifestations of COVID-19, especially those that occur early in the disease (eg, vesicular eruptions) or have prognostic significance (livedo, retiform purpura, necrosis), are critical to this goal of early recognition.

In this context, a recent systematic literature review looked at all articles describing skin manifestations associated with COVID-19. The investigators identified 46 articles published between March and May 2020 which included a total of 130 clinical images.

The following findings from this study are striking:

- 92% of the published images of COVID-associated skin manifestations were in I-III.

- Only 6% of COVID skin lesions included in the articles were in patients with skin type IV.

- None showed COVID skin lesions in skin types V or VI.

- Only six of the articles reported race and ethnicity demographics. In those, 91% of the patients were White and 9% were Hispanic.

These results reveal a critical lack of representative clinical images of COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color. This deficiency is made all the more egregious given the fact that patients of color, including those who are Black, Latinx, and Native American, have been especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer disproportionate disease-related morbidity and mortality.

As the study authors point out, skin manifestations in people of color often differ significantly from findings in White skin (for example, look at the figure depicting the rash typical of Kawasaki disease in a dark-skinned child compared with a light-skinned child). It is not a stretch to suggest that skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 may look very different in darker skin.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Almost half of dermatologists feel that they’ve had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types. Skin of color remains underrepresented in medical journals.

Like other forms of passive, institutional racism, this deficiency will only be improved if dermatologists and dermatology publications actively seek out COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color and prioritize sharing these images. A medical student in the United Kingdom has gotten the ball rolling, compiling a handbook of clinical signs in darker skin types as part of a student-staff partnership at St. George’s Hospital and the University of London. At this time, Mind the Gap is looking for a publisher.

Dr. Lipper is an assistant clinical professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a staff physician in the department of dermatology at Danbury (Conn.) Hospital. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Belatedly, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on patients of color is getting attention. By now, we’ve read the headlines. Black people in the United States make up about 13% of the population but account for almost three times (34%) as many deaths. This story repeats – in other countries and in other minority communities.

Early detection is critical both to initiate supportive care and to isolate affected individuals and limit spread. Skin manifestations of COVID-19, especially those that occur early in the disease (eg, vesicular eruptions) or have prognostic significance (livedo, retiform purpura, necrosis), are critical to this goal of early recognition.

In this context, a recent systematic literature review looked at all articles describing skin manifestations associated with COVID-19. The investigators identified 46 articles published between March and May 2020 which included a total of 130 clinical images.

The following findings from this study are striking:

- 92% of the published images of COVID-associated skin manifestations were in I-III.

- Only 6% of COVID skin lesions included in the articles were in patients with skin type IV.

- None showed COVID skin lesions in skin types V or VI.

- Only six of the articles reported race and ethnicity demographics. In those, 91% of the patients were White and 9% were Hispanic.

These results reveal a critical lack of representative clinical images of COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color. This deficiency is made all the more egregious given the fact that patients of color, including those who are Black, Latinx, and Native American, have been especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer disproportionate disease-related morbidity and mortality.

As the study authors point out, skin manifestations in people of color often differ significantly from findings in White skin (for example, look at the figure depicting the rash typical of Kawasaki disease in a dark-skinned child compared with a light-skinned child). It is not a stretch to suggest that skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 may look very different in darker skin.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Almost half of dermatologists feel that they’ve had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types. Skin of color remains underrepresented in medical journals.

Like other forms of passive, institutional racism, this deficiency will only be improved if dermatologists and dermatology publications actively seek out COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color and prioritize sharing these images. A medical student in the United Kingdom has gotten the ball rolling, compiling a handbook of clinical signs in darker skin types as part of a student-staff partnership at St. George’s Hospital and the University of London. At this time, Mind the Gap is looking for a publisher.

Dr. Lipper is an assistant clinical professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a staff physician in the department of dermatology at Danbury (Conn.) Hospital. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Belatedly, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on patients of color is getting attention. By now, we’ve read the headlines. Black people in the United States make up about 13% of the population but account for almost three times (34%) as many deaths. This story repeats – in other countries and in other minority communities.

Early detection is critical both to initiate supportive care and to isolate affected individuals and limit spread. Skin manifestations of COVID-19, especially those that occur early in the disease (eg, vesicular eruptions) or have prognostic significance (livedo, retiform purpura, necrosis), are critical to this goal of early recognition.

In this context, a recent systematic literature review looked at all articles describing skin manifestations associated with COVID-19. The investigators identified 46 articles published between March and May 2020 which included a total of 130 clinical images.

The following findings from this study are striking:

- 92% of the published images of COVID-associated skin manifestations were in I-III.

- Only 6% of COVID skin lesions included in the articles were in patients with skin type IV.

- None showed COVID skin lesions in skin types V or VI.

- Only six of the articles reported race and ethnicity demographics. In those, 91% of the patients were White and 9% were Hispanic.

These results reveal a critical lack of representative clinical images of COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color. This deficiency is made all the more egregious given the fact that patients of color, including those who are Black, Latinx, and Native American, have been especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer disproportionate disease-related morbidity and mortality.

As the study authors point out, skin manifestations in people of color often differ significantly from findings in White skin (for example, look at the figure depicting the rash typical of Kawasaki disease in a dark-skinned child compared with a light-skinned child). It is not a stretch to suggest that skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 may look very different in darker skin.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Almost half of dermatologists feel that they’ve had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types. Skin of color remains underrepresented in medical journals.

Like other forms of passive, institutional racism, this deficiency will only be improved if dermatologists and dermatology publications actively seek out COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color and prioritize sharing these images. A medical student in the United Kingdom has gotten the ball rolling, compiling a handbook of clinical signs in darker skin types as part of a student-staff partnership at St. George’s Hospital and the University of London. At this time, Mind the Gap is looking for a publisher.

Dr. Lipper is an assistant clinical professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a staff physician in the department of dermatology at Danbury (Conn.) Hospital. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical student in the UK creates handbook of clinical signs on darker skin

.

Malone Mukwende, a second year student at St. George’s, University of London, had the idea after only being taught about clinical signs and symptoms on White skin.

The handbook is called Mind the Gap. It contains side-by-side images demonstrating how illnesses and diseases can present in light and dark skin.

He hopes the handbook will help future doctors spot and diagnose potentially life-threatening diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people.

It comes as nearly 200,000 people have signed a petition calling for medical schools to include BAME representation in clinical teaching.

It points to Kawasaki disease, a rare condition affecting young children. On white skin it appears as a red rash but on darker skin it shows up differently and is much harder to spot.

Medscape UK asked Malone Mukwende about the handbook.

Q&A

Where did the idea come from for Mind the Gap?

On arrival at medical school I noticed the lack of teaching on darker skins. We were often being taught to look for symptoms such as red rashes. I was aware that this would not appear as described in my own skin. When flagging to tutors it was clear that they didn’t know of any other way to describe these conditions and I knew that I had to make a change to that. After extensively asking peer tutors and also lecturers it was clear there was a major gap in the current medical education and a lot of the time I was being told to go and look for it myself.

Following on from that I undertook a staff-student partnership at my university with two members of staff who helped me to create Mind the Gap.

Who did you collaborate with at St. George’s?

I worked with Margot Turner, a senior lecturer in diversity, and Dr. Peter Tamony, a clinical lecturer. We were a dynamic team that had a common goal in mind.

When will the handbook be available?

We are currently working on the best way of disseminating the work to the public. There has been an incredible response since I posted it on my social media, with posts being seen over 3 million times, as well as numerous press features. I am hoping to provide a further update on when the book will be out toward the end of July.

What do you think of the petition to medical schools to include more teaching of the effects of illness and diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic people?

The petition closely ties in with the work that I am doing. It is clear that there is an urgent need to increase the medical education on darker skins so that the profession can serve the patient population. We saw in the recent COVID-19 pandemic that the worst affected group of people were from a BAME background.

There are a host of reasons as to why this may have been the case. However another factor may be that healthcare professionals weren’t able to identify these signs and symptoms in time. Some of the coronavirus guidance from royal colleges stated information such as looking for patients to be ‘blue around the lips’. This may have led to slower identification of coronavirus.

To see over 180,000 signatures on the petition was a positive step in the right direction. It is clear to see that this is a big issue. If we fail to act now that the issue has been identified, we run the risk of lives being lost.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Malone Mukwende, a second year student at St. George’s, University of London, had the idea after only being taught about clinical signs and symptoms on White skin.

The handbook is called Mind the Gap. It contains side-by-side images demonstrating how illnesses and diseases can present in light and dark skin.

He hopes the handbook will help future doctors spot and diagnose potentially life-threatening diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people.

It comes as nearly 200,000 people have signed a petition calling for medical schools to include BAME representation in clinical teaching.

It points to Kawasaki disease, a rare condition affecting young children. On white skin it appears as a red rash but on darker skin it shows up differently and is much harder to spot.

Medscape UK asked Malone Mukwende about the handbook.

Q&A

Where did the idea come from for Mind the Gap?

On arrival at medical school I noticed the lack of teaching on darker skins. We were often being taught to look for symptoms such as red rashes. I was aware that this would not appear as described in my own skin. When flagging to tutors it was clear that they didn’t know of any other way to describe these conditions and I knew that I had to make a change to that. After extensively asking peer tutors and also lecturers it was clear there was a major gap in the current medical education and a lot of the time I was being told to go and look for it myself.

Following on from that I undertook a staff-student partnership at my university with two members of staff who helped me to create Mind the Gap.

Who did you collaborate with at St. George’s?

I worked with Margot Turner, a senior lecturer in diversity, and Dr. Peter Tamony, a clinical lecturer. We were a dynamic team that had a common goal in mind.

When will the handbook be available?

We are currently working on the best way of disseminating the work to the public. There has been an incredible response since I posted it on my social media, with posts being seen over 3 million times, as well as numerous press features. I am hoping to provide a further update on when the book will be out toward the end of July.

What do you think of the petition to medical schools to include more teaching of the effects of illness and diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic people?

The petition closely ties in with the work that I am doing. It is clear that there is an urgent need to increase the medical education on darker skins so that the profession can serve the patient population. We saw in the recent COVID-19 pandemic that the worst affected group of people were from a BAME background.

There are a host of reasons as to why this may have been the case. However another factor may be that healthcare professionals weren’t able to identify these signs and symptoms in time. Some of the coronavirus guidance from royal colleges stated information such as looking for patients to be ‘blue around the lips’. This may have led to slower identification of coronavirus.

To see over 180,000 signatures on the petition was a positive step in the right direction. It is clear to see that this is a big issue. If we fail to act now that the issue has been identified, we run the risk of lives being lost.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Malone Mukwende, a second year student at St. George’s, University of London, had the idea after only being taught about clinical signs and symptoms on White skin.

The handbook is called Mind the Gap. It contains side-by-side images demonstrating how illnesses and diseases can present in light and dark skin.

He hopes the handbook will help future doctors spot and diagnose potentially life-threatening diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people.

It comes as nearly 200,000 people have signed a petition calling for medical schools to include BAME representation in clinical teaching.

It points to Kawasaki disease, a rare condition affecting young children. On white skin it appears as a red rash but on darker skin it shows up differently and is much harder to spot.

Medscape UK asked Malone Mukwende about the handbook.

Q&A

Where did the idea come from for Mind the Gap?

On arrival at medical school I noticed the lack of teaching on darker skins. We were often being taught to look for symptoms such as red rashes. I was aware that this would not appear as described in my own skin. When flagging to tutors it was clear that they didn’t know of any other way to describe these conditions and I knew that I had to make a change to that. After extensively asking peer tutors and also lecturers it was clear there was a major gap in the current medical education and a lot of the time I was being told to go and look for it myself.

Following on from that I undertook a staff-student partnership at my university with two members of staff who helped me to create Mind the Gap.

Who did you collaborate with at St. George’s?

I worked with Margot Turner, a senior lecturer in diversity, and Dr. Peter Tamony, a clinical lecturer. We were a dynamic team that had a common goal in mind.

When will the handbook be available?

We are currently working on the best way of disseminating the work to the public. There has been an incredible response since I posted it on my social media, with posts being seen over 3 million times, as well as numerous press features. I am hoping to provide a further update on when the book will be out toward the end of July.

What do you think of the petition to medical schools to include more teaching of the effects of illness and diseases on Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic people?

The petition closely ties in with the work that I am doing. It is clear that there is an urgent need to increase the medical education on darker skins so that the profession can serve the patient population. We saw in the recent COVID-19 pandemic that the worst affected group of people were from a BAME background.

There are a host of reasons as to why this may have been the case. However another factor may be that healthcare professionals weren’t able to identify these signs and symptoms in time. Some of the coronavirus guidance from royal colleges stated information such as looking for patients to be ‘blue around the lips’. This may have led to slower identification of coronavirus.

To see over 180,000 signatures on the petition was a positive step in the right direction. It is clear to see that this is a big issue. If we fail to act now that the issue has been identified, we run the risk of lives being lost.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Staggering’ increase in COVID-linked depression, anxiety

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a dramatic increase in depression, anxiety, psychosis, and suicidality, new research shows.

The new data, released by Mental Health America (MHA), came from individuals who completed a voluntary online mental health screen.

As of the end of June, over 169,000 additional participants reported having moderate to severe depression or anxiety, compared with participants who completed the screen prior to the pandemic.

In June alone, 18,000 additional participants were found to be at risk for psychosis, continuing a rising pattern that began in May, when 16,000 reported psychosis risk.

“We continue to see staggering numbers that indicate increased rates in depression and anxiety because of COVID-19,” Paul Gionfriddo, president and CEO of MHA, said in a release.