User login

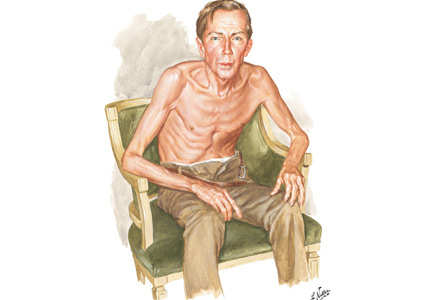

Thinker’s sign

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

See Mangione and Aronowitz editorials

Mechanical pressure induced by friction of the elbows on the thighs may result in proliferation of the stratum corneum and the release of hemosiderin from erythrocytes, resulting in the skin changes seen in this patient, which because of the tripod positioning are known as “thinker’s sign,” a term coined in 1963 by Rothenberg1 to describe findings in patients with chronic pulmonary disease and advanced respiratory insufficiency. It is also referred to as the Dahl sign, based on a report by Dahl of similar findings in patients with emphysema.2

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

- Rothenberg HJ. The thinker's sign. JAMA 1963; 184:902–903. pmid:13975358

- Dahl MV. Emphysema. Arch Dermatol 1970; 101(1):117. pmid:5416788

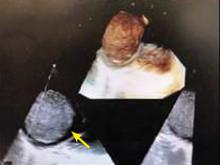

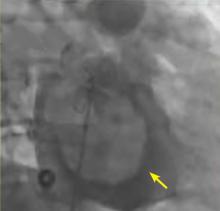

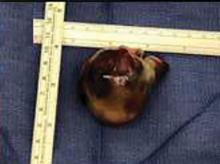

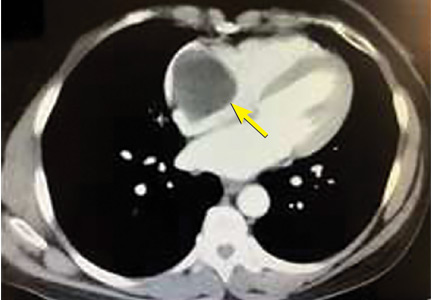

A right atrial mass

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

PRIMARY HEART TUMORS ARE RARE

The most common neoplasms that metastasize to the heart are malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia, breast, and lung cancers. The layers of the heart affected by malignant neoplasms in order of frequency from highest to lowest are the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and endocardium.3

MYXOMA: A PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

The most common type of primary cardiac tumor is myxoma. Most—75% to 80%—occur in the left atrium, while 15% to 20% occur in the right atrium.5 Right atrial myxomas are usually found in the intraatrial septum at the border of the fossa ovalis.6 Myxomas can occur at any age, but are most common in women between the third and sixth decades.2

The cause of atrial myxomas is currently unknown. Most cases are sporadic. However, 10% are familial, with an autosomal-dominant pattern.7

The clinical symptoms of right atrial myxoma depend on the tumor’s size, location, and mobility and on the patient’s physical activity and body position.4 Common presenting symptoms include shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, cough, hemoptysis, and fatigue. Thirty percent of patients present with constitutional symptoms.4

Auscultation may reveal a characteristic “tumor plop” early in diastole.4,7 About 35% of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and globulin levels and anemia. Our patient did not.

Embolization occurs in about 10% of cases of right-sided myxoma and can result in pulmonary artery embolism or a stroke. Pulmonary artery embolism occurs with myxoma embolization to the lungs. Strokes can occur in patients who have a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, through which embolism to the systemic arterial circulation can occur.

The primary treatment for myxoma is complete resection of the tumor and its base with wide safety margins. This is particularly important to prevent recurrence of the myxoma and need for repeat operations, with their risk of surgical complications.9

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

- Dujardin KS, Click RL, Oh JK. The role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing cardiac mass removal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13(12):1080–1083. pmid:11119275

- Jang KH, Shin DH, Lee C, Jang JK, Cheong S, Yoo SY. Left atrial mass with stalk: thrombus or myxoma? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010; 18(4):154–156. doi:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.4.154

- Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 2013; 128(16):1790–1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790

- Aggarwal SK, Barik R, Sarma TC, et al. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: new insights from the developing world. Am Heart J 2007; 154(6):1102–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.032

- Diaz A, Di Salvo C, Lawrence D, Hayward M. Left atrial and right ventricular myxoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare tumour. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 12(4):622–623. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.255661

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1610–1617. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332407

- Kolluru A, Desai D, Cohen GI. The etiology of atrial myxoma tumor plop. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(21):e371. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.085

- Kassab R, Wehbe L, Badaoui G, el Asmar B, Jebara V, Ashoush R. Recurrent cerebrovascular accident: unusual and isolated manifestation of myxoma of the left atrium. J Med Liban 1999; 47(4):246–250. French. pmid:10641454

- Guhathakurta S, Riordan JP. Surgical treatment of right atrial myxoma. Tex Heart Inst J 2000; 27(1):61–63. pmid:10830633

New CLTI Global Guidelines Available

On May 31, new global guidelines on the best ways to treat Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia were co-published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery and the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. This comes after four years of collaboration between vascular experts from around the world. According to the SVS’ own Dr. Conte, a co-editor, the group created a unique practice guideline that reflects the spectrum of the diseases and the approaches seen worldwide. Read the guidelines in the JVS here.

On May 31, new global guidelines on the best ways to treat Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia were co-published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery and the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. This comes after four years of collaboration between vascular experts from around the world. According to the SVS’ own Dr. Conte, a co-editor, the group created a unique practice guideline that reflects the spectrum of the diseases and the approaches seen worldwide. Read the guidelines in the JVS here.

On May 31, new global guidelines on the best ways to treat Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia were co-published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery and the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. This comes after four years of collaboration between vascular experts from around the world. According to the SVS’ own Dr. Conte, a co-editor, the group created a unique practice guideline that reflects the spectrum of the diseases and the approaches seen worldwide. Read the guidelines in the JVS here.

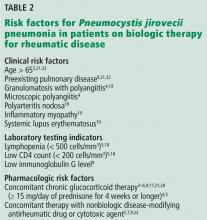

Do patients on biologic drugs for rheumatic disease need PCP prophylaxis?

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.

You can observe a lot by watching

"I have trained myself to see what others overlook."

—Sherlock Holmes1

The article by Grandjean and Huber in this issue2 is a timely reminder of the importance of skilled observation in medical care. Osler3 considered observation to represent “the whole art of medicine,” but warned that “for some men it is quite as difficult to record an observation in brief and plain language.” This insight captures not only the never-ending feud between written and visual communication, but also the higher efficiency of images. Leonardo da Vinci, a visual thinker with a touch of dyslexia,4 often boasted in colorful terms about the superiority of the visual. Next to his amazing rendition of a bovine heart he scribbled, “[Writer] how could you describe this heart in words without filling a whole book? So, don’t bother with words unless you are speaking to the blind…you will always be overruled by the painter.”5

See related article and editorial

Ironically, physicians have often preferred the written over the visual. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., professor of anatomy at Harvard Medical School and renowned essayist, once wrote a scathing review of a new anatomy textbook that, according to him, had just too many pictures. “Let a student have illustrations,” he thundered “and just so surely will he use them at the expense of the text.”6 The book was Gray’s Anatomy, but Holmes’ tirade exemplifies the conundrum of our profession: to become physicians we must read (and memorize) lots of written text, with little emphasis on how much more efficiently information might be conveyed through a single picture.

This trend is probably worsening. When I first came to the United States 43 years ago, I was amazed at how many of my professors immediately grabbed a sheet of paper and started drawing their explanations to my questions. But I have not seen much of this lately, and that is a pity, since pictures are undoubtedly a better way of communicating.

OBSERVING A PATIENT WITH COPD

Netter’s patient is also exhaling through pursed lips. This reduces the respiratory rate and carbon dioxide level, while improving distribution of ventilation,9,10 oxygen saturation, tidal volume, inspiratory muscle strength, and diaphragmatic efficiency.11,12 Since less inspiratory force is required for each breath, dyspnea is also improved.13,14 Diagnostically, pursed‑lip breathing increases the probability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with a likelihood ratio of 5.05.15

The man in The Pink Puffer is using accessory respiratory muscles, which not only represents one of the earliest signs of airway obstruction, but also reflects severe disease. In fact, use of accessory respiratory muscles occurs in more than 90% of COPD patients admitted for acute exacerbations.7

Lastly, Netter’s patient exhibits inspiratory retraction of supraclavicular fossae and interspaces (tirage), which indicates increased airway resistance and reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).16,17 A clavicular “lift” of more than 5 mm correlates with an FEV1 of 0.6 L.18

But what is odd about this patient is what Netter did not portray: clubbing. This goes against the conventional wisdom of the time but is actually correct, since we now know that clubbing is more a feature of chronic bronchitis than emphysema.19 In fact, if present in a “pink puffer,” it should suggest an underlying malignancy. Hence, Netter reminds us that we should never convince ourselves that we see something simply because we know it should be there. Instead, we should always rely on what we see. This is, after all, how Vesalius debunked Galen’s anatomic errors: by seeing for himself. Tom McCrae, Osler’s right-hand man at Johns Hopkins, used to warn his students that one misses more by not seeing than by not knowing. Leonardo put it simply: “Wisdom is the daughter of [visual] experience.”20 In the end, Netter’s drawing reminds us that a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

TEACHING STUDENTS TO OBSERVE

Unfortunately, detecting detail is difficult. It is also very difficult to teach. For the past few months I’ve been asking astute clinicians how they observe, and most of them seem befuddled, as if I had asked which muscles they contract in order to walk. They just walk. And they just observe.

So, how can we rekindle this important but underappreciated component of the physician’s skill set? First of all, by becoming cognizant of its fundamental role in medicine. Second, by accepting that this is something that cannot be easily tested by single-best- answer, black-and-white, multiple-choice exams. Recognizing the complexity of clinical skills reminds us that not all that counts in medicine can be counted, and not all that can be counted counts. Yet it also provides a hurdle, since testing typically drives curriculum. If we cannot assess observation, how can we reincorporate it in the curriculum? Lastly, we need to regain ownership of the teaching of this skill. No art instructor can properly identify and interpret clinical findings. Hence, physicians ought to teach it. In the end, learning how to properly observe is a personal and lifelong effort. As Osler put it, “There is no more difficult art to acquire than the art of observation.”21

Leonardo used to quip that “There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, and those who do not see.”22 Yet this time Leonardo might have been wrong. There are really only two kinds of people: those who have been taught how to observe and those who have not. Leonardo was lucky enough to have been apprenticed to an artist whose nickname was Verrocchio, which resembles the Italian words vero occhio, a “fine eye.” Without Verrocchio, even Leonardo might not have become such a skilled observer. How many Verrocchios are around today?

- Doyle AC. A case of identity. In: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London, UK: George Newnes; 1892.

- Grandjean R, Huber LC. Thinker’s sign. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(7):439. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.19036

- Osler W. The natural method of teaching the subject of medicine. JAMA 1901; 36(24):1673–1679. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470240001001

- Mangione S, Del Maestro R. Was Leonardo da Vinci dyslexic? Am J Med 2019 Mar 7; pii:S0002-9343(19)30214-1. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.019

- Leonardo Da Vinci. Studies of the Heart of an Ox, Great Vessels and Bronchial Tree (c. 1513); pen and ink on blue paper, Windsor, London, UK Royal Library (19071r).

- Holmes OW Sr. Gray’s Anatomy. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1859; 60(25):489–496.

- O’Neill S, McCarthy DS. Postural relief of dyspnoea in severe chronic airflow limitation: relationship to respiratory muscle strength. Thorax 1983; 38(8):595–600. pmid:6612651

- Banzett RB, Topulos GP, Leith DE, Nations CS. Bracing arms increases the capacity for sustained hyperpnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138(1):106–109. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/138.1.106

- Mueller RE, Petty TL, Filley GF. Ventilation and arterial blood gas changes induced by pursed lips breathing. J Appl Physiol 1970; 28(6):784–789. doi:10.1152/jappl.1970.28.6.784

- Thoman RL, Stoker GL, Ross JC. The efficacy of pursed-lips breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1966; 93(1):100–106.

- Breslin EH. The pattern of respiratory muscle recruitment during pursed-lip breathing. Chest 1992; 101(1):75–78. pmid:1729114

- Jones AY, Dean E, Chow CC. Comparison of the oxygen cost of breathing exercises and spontaneous breathing in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther 2003; 83(5):424–431. pmid:12718708

- el-Manshawi A, Killian KJ, Summers E, Jones NL. Breathlessness during exercise with and without resistive loading. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986; 61(3):896–905. doi:10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.896