User login

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Coagulation in cirrhosis

Cirrhosis can involve “precarious” changes in hemostatic pathways that tip the scales toward either bleeding or hypercoagulation, experts wrote in an American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update.

Based on current evidence, clinicians should not routinely correct thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis prior to low-risk procedures, such as therapeutic paracentesis, thoracentesis, and routine upper endoscopy for variceal ligation, Jacqueline G. O’Leary, MD, of Dallas VA Medical Center and her three coreviewers wrote in Gastroenterology.

To optimize clot formation prior to high-risk procedures, and in patients with active bleeding, a platelet count above 50,000 per mcL is still recommended. However, it may be more meaningful to couple that platelet target with a fibrinogen level above 120 mg/dL rather than rely on the international normalized ratio (INR), the experts wrote. Not only does INR vary significantly depending on which thromboplastin is used in the test, but “correcting” INR with a fresh frozen plasma infusion does not affect thrombin production and worsens portal hypertension. Using cryoprecipitate to replenish fibrinogen has less impact on portal hypertension. “Global tests of clot formation, such as rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), thromboelastography (TEG), sonorheometry, and thrombin generation may eventually have a role in the evaluation of clotting in patients with cirrhosis but currently lack validated target levels,” the experts wrote.

They advised clinicians to limit the use of blood products (such as fresh frozen plasma and pooled platelet transfusions) because of cost and the risk of exacerbated portal hypertension, infection, and immunologic complications. For severe anemia and uremia, red blood cell transfusion (250 mL) can be considered. Platelet-rich plasma from one donor is less immunologically risky than a pooled platelet transfusion. Thrombopoietin agonists are “a good alternative” to platelet transfusion but require about 10 days for response. Alternative prothrombotic therapies include oral thrombopoietin receptor agonists (avatrombopag and lusutrombopag) to boost platelet count before an invasive procedure, antifibrinolytic therapy (aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) for persistent bleeding from mucosal oozing or puncture wounds. Desmopressin should only be considered for patients with comorbid renal failure.

For anticoagulation, the practice update recommends considering systemic heparin infusion for cirrhotic patients with symptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or portal vein thrombosis (PVT). However, the anti–factor Xa assay will not reliably monitor response if patients have low liver-derived antithrombin III (heparin cofactor). “With newly diagnosed PVT, the decision to intervene with directed therapy rests on the extent of the thrombosis, presence or absence of attributable symptoms, and the risk of bleeding and falls,” the experts stated.

Six-month follow-up imaging is recommended to assess anticoagulation efficacy. More frequent imaging can be considered for PVT patients considered at high risk for therapeutic anticoagulation. If clots do not fully resolve after 6 months of treatment, options including extending therapy with the same agent, switching to a different anticoagulant class, or receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). “The role for TIPS in PVT is evolving and may address complications like portal hypertensive bleeding, medically refractory clot, and the need for repeated banding after variceal bleeding,” the experts noted.

Prophylaxis of DVT is recommended for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Vitamin K antagonists and direct-acting oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) are alternatives to heparin for anticoagulation of cirrhotic patients with either PVT and DVT, the experts wrote. However, DOACs are not recommended for most Child-Pugh B patients or for any Child-Pugh C patients.

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary JG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.070.

Cirrhosis can involve “precarious” changes in hemostatic pathways that tip the scales toward either bleeding or hypercoagulation, experts wrote in an American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update.

Based on current evidence, clinicians should not routinely correct thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis prior to low-risk procedures, such as therapeutic paracentesis, thoracentesis, and routine upper endoscopy for variceal ligation, Jacqueline G. O’Leary, MD, of Dallas VA Medical Center and her three coreviewers wrote in Gastroenterology.

To optimize clot formation prior to high-risk procedures, and in patients with active bleeding, a platelet count above 50,000 per mcL is still recommended. However, it may be more meaningful to couple that platelet target with a fibrinogen level above 120 mg/dL rather than rely on the international normalized ratio (INR), the experts wrote. Not only does INR vary significantly depending on which thromboplastin is used in the test, but “correcting” INR with a fresh frozen plasma infusion does not affect thrombin production and worsens portal hypertension. Using cryoprecipitate to replenish fibrinogen has less impact on portal hypertension. “Global tests of clot formation, such as rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), thromboelastography (TEG), sonorheometry, and thrombin generation may eventually have a role in the evaluation of clotting in patients with cirrhosis but currently lack validated target levels,” the experts wrote.

They advised clinicians to limit the use of blood products (such as fresh frozen plasma and pooled platelet transfusions) because of cost and the risk of exacerbated portal hypertension, infection, and immunologic complications. For severe anemia and uremia, red blood cell transfusion (250 mL) can be considered. Platelet-rich plasma from one donor is less immunologically risky than a pooled platelet transfusion. Thrombopoietin agonists are “a good alternative” to platelet transfusion but require about 10 days for response. Alternative prothrombotic therapies include oral thrombopoietin receptor agonists (avatrombopag and lusutrombopag) to boost platelet count before an invasive procedure, antifibrinolytic therapy (aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) for persistent bleeding from mucosal oozing or puncture wounds. Desmopressin should only be considered for patients with comorbid renal failure.

For anticoagulation, the practice update recommends considering systemic heparin infusion for cirrhotic patients with symptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or portal vein thrombosis (PVT). However, the anti–factor Xa assay will not reliably monitor response if patients have low liver-derived antithrombin III (heparin cofactor). “With newly diagnosed PVT, the decision to intervene with directed therapy rests on the extent of the thrombosis, presence or absence of attributable symptoms, and the risk of bleeding and falls,” the experts stated.

Six-month follow-up imaging is recommended to assess anticoagulation efficacy. More frequent imaging can be considered for PVT patients considered at high risk for therapeutic anticoagulation. If clots do not fully resolve after 6 months of treatment, options including extending therapy with the same agent, switching to a different anticoagulant class, or receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). “The role for TIPS in PVT is evolving and may address complications like portal hypertensive bleeding, medically refractory clot, and the need for repeated banding after variceal bleeding,” the experts noted.

Prophylaxis of DVT is recommended for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Vitamin K antagonists and direct-acting oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) are alternatives to heparin for anticoagulation of cirrhotic patients with either PVT and DVT, the experts wrote. However, DOACs are not recommended for most Child-Pugh B patients or for any Child-Pugh C patients.

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary JG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.070.

Cirrhosis can involve “precarious” changes in hemostatic pathways that tip the scales toward either bleeding or hypercoagulation, experts wrote in an American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update.

Based on current evidence, clinicians should not routinely correct thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis prior to low-risk procedures, such as therapeutic paracentesis, thoracentesis, and routine upper endoscopy for variceal ligation, Jacqueline G. O’Leary, MD, of Dallas VA Medical Center and her three coreviewers wrote in Gastroenterology.

To optimize clot formation prior to high-risk procedures, and in patients with active bleeding, a platelet count above 50,000 per mcL is still recommended. However, it may be more meaningful to couple that platelet target with a fibrinogen level above 120 mg/dL rather than rely on the international normalized ratio (INR), the experts wrote. Not only does INR vary significantly depending on which thromboplastin is used in the test, but “correcting” INR with a fresh frozen plasma infusion does not affect thrombin production and worsens portal hypertension. Using cryoprecipitate to replenish fibrinogen has less impact on portal hypertension. “Global tests of clot formation, such as rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM), thromboelastography (TEG), sonorheometry, and thrombin generation may eventually have a role in the evaluation of clotting in patients with cirrhosis but currently lack validated target levels,” the experts wrote.

They advised clinicians to limit the use of blood products (such as fresh frozen plasma and pooled platelet transfusions) because of cost and the risk of exacerbated portal hypertension, infection, and immunologic complications. For severe anemia and uremia, red blood cell transfusion (250 mL) can be considered. Platelet-rich plasma from one donor is less immunologically risky than a pooled platelet transfusion. Thrombopoietin agonists are “a good alternative” to platelet transfusion but require about 10 days for response. Alternative prothrombotic therapies include oral thrombopoietin receptor agonists (avatrombopag and lusutrombopag) to boost platelet count before an invasive procedure, antifibrinolytic therapy (aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) for persistent bleeding from mucosal oozing or puncture wounds. Desmopressin should only be considered for patients with comorbid renal failure.

For anticoagulation, the practice update recommends considering systemic heparin infusion for cirrhotic patients with symptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or portal vein thrombosis (PVT). However, the anti–factor Xa assay will not reliably monitor response if patients have low liver-derived antithrombin III (heparin cofactor). “With newly diagnosed PVT, the decision to intervene with directed therapy rests on the extent of the thrombosis, presence or absence of attributable symptoms, and the risk of bleeding and falls,” the experts stated.

Six-month follow-up imaging is recommended to assess anticoagulation efficacy. More frequent imaging can be considered for PVT patients considered at high risk for therapeutic anticoagulation. If clots do not fully resolve after 6 months of treatment, options including extending therapy with the same agent, switching to a different anticoagulant class, or receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). “The role for TIPS in PVT is evolving and may address complications like portal hypertensive bleeding, medically refractory clot, and the need for repeated banding after variceal bleeding,” the experts noted.

Prophylaxis of DVT is recommended for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Vitamin K antagonists and direct-acting oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) are alternatives to heparin for anticoagulation of cirrhotic patients with either PVT and DVT, the experts wrote. However, DOACs are not recommended for most Child-Pugh B patients or for any Child-Pugh C patients.

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary JG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.070.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Stable COPD: Initiating and Optimizing Therapy

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by irreversible obstructive ventilatory defects.1-4 It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting 5% of the population in the United States and ranking as the third leading cause of death in 2008.5,6 The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. In this 3-part review, we discuss the management of stable COPD in the context of 3 common clinical scenarios: initiating and optimizing therapy, managing acute exacerbations, and managing advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man with COPD underwent pulmonary function testing (PFT), which demonstrated an obstructive ventilatory defect: forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio (FEV1/FVC), 0.45; FEV1, 2 L (65% of predicted); and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, 15 mL/min/mm Hg (65% of predicted). He has dyspnea with strenuous exercise but is comfortable at rest and with minimal exercise. He has had 1 exacerbation in the past year, and this was treated on an outpatient basis with steroids and antibiotics. His medication regimen includes inhaled tiotropium once daily and inhaled albuterol as needed that he uses roughly twice a week.

What determines the appropriate therapy for a given COPD patient?

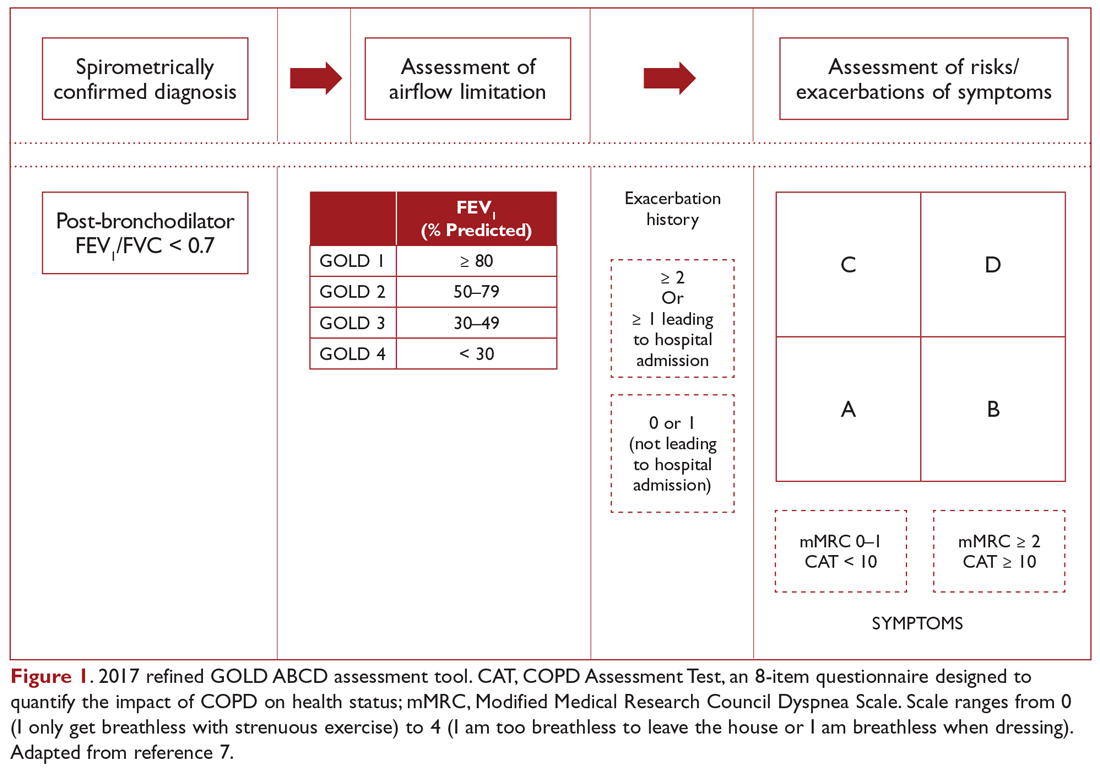

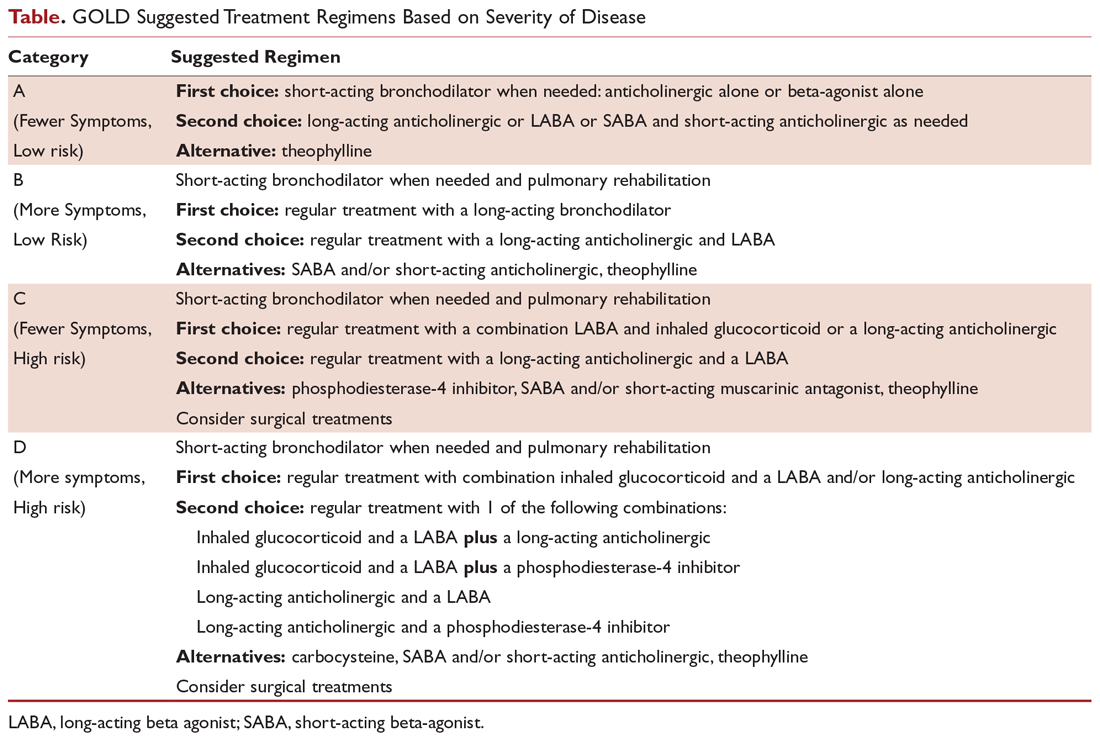

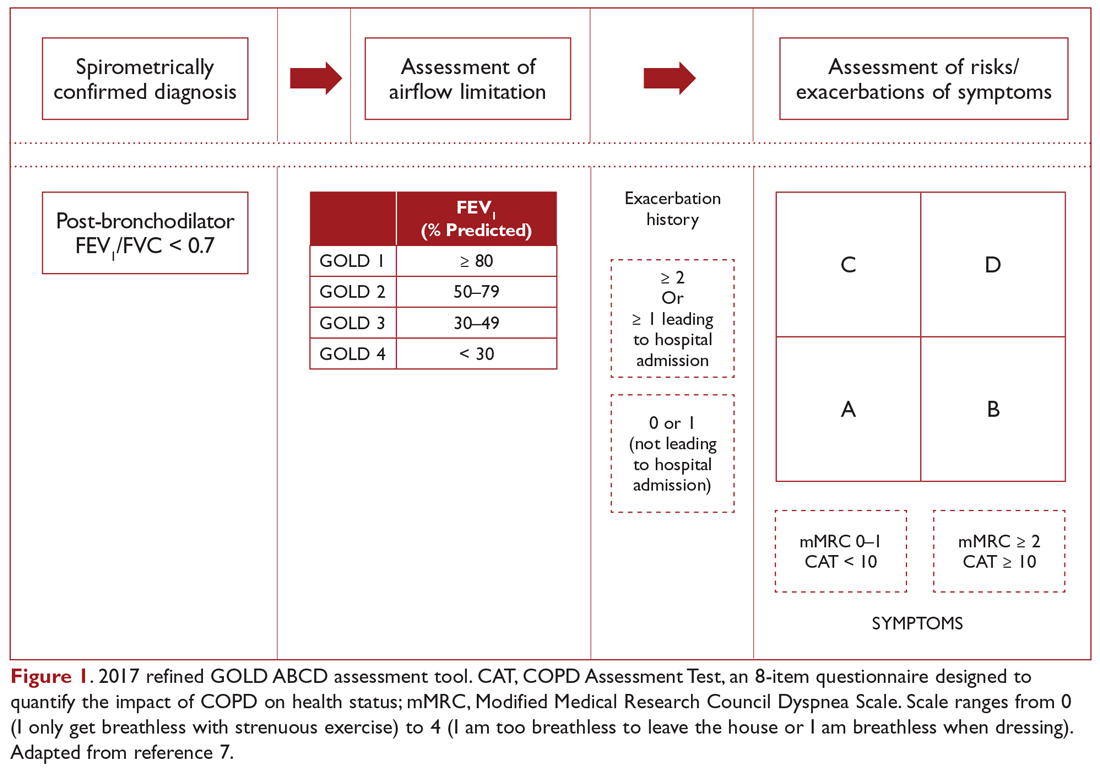

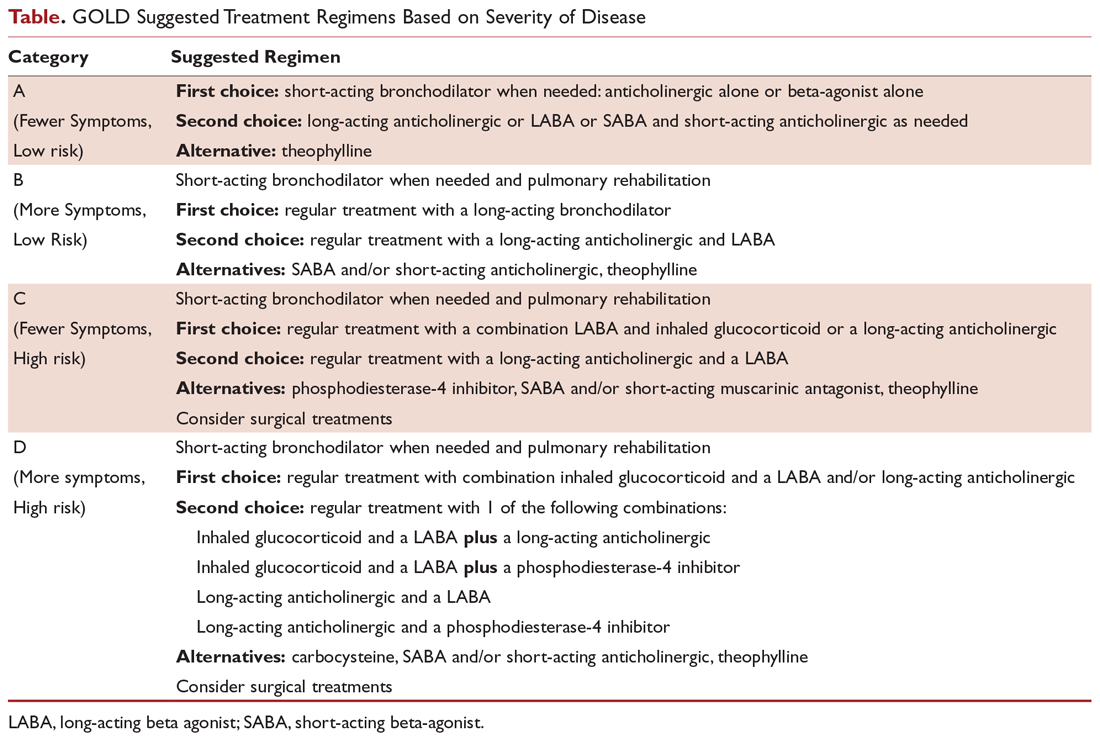

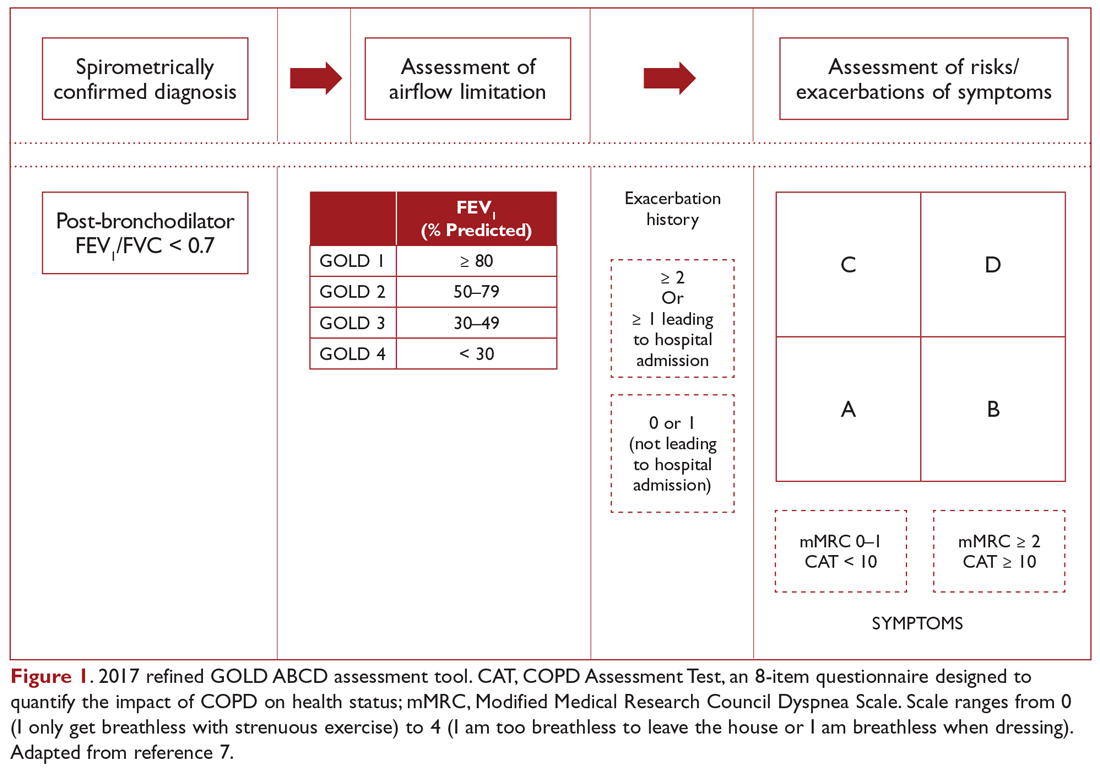

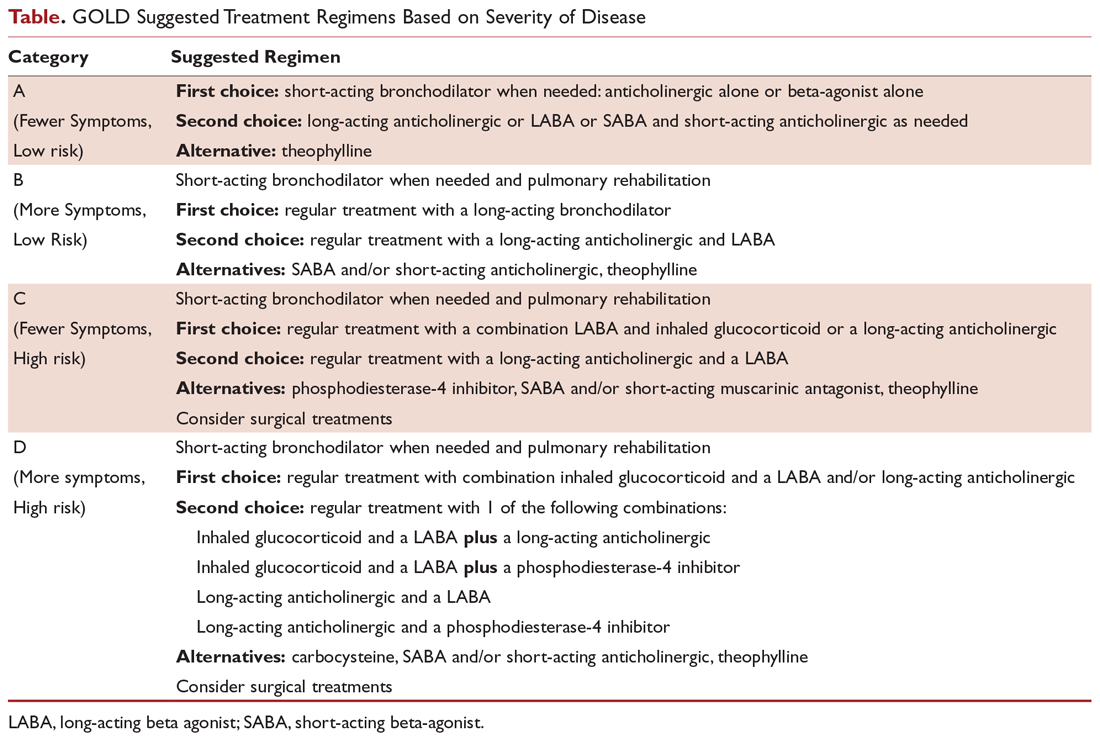

COPD management is guided by disease severity that is measured using a multimodal staging system developed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). The initial classification adopted by the GOLD 2011 report encompassed 4 categories based on symptoms, number of exacerbations, and degree of airflow limitation on PFT. However, in 2017 the GOLD ABCD classification was modified to consider only symptoms and risk of exacerbation in classifying patients, regardless of performance on spirometry and FEV1 (Figure 1).7,8 This approach was intended to make therapy more individualized based on the patient clinical profile. The Table provides a summary of the recommended treatments according to classification based on the GOLD 2017 report.

The patient in our clinical scenario can be classified as GOLD category B.

What is the approach to building a pharmacologic regimen for the patient with COPD?

The backbone of the pharmacologic regimen for COPD includes short- and long-acting bronchodilators. They are usually given in an inhaled form to maximize local effects on the lungs and minimize systemic side effects. There are 2 main classes of bronchodilators, beta-agonists and muscarinic antagonists, and each targets specific receptors on the surface of airway smooth muscle cells. Beta- agonists work by stimulating beta-2 receptors, resulting in bronchodilation, while muscarinic antagonists work by blocking the bronchoconstrictor action of M3 muscarinic receptors. Inhaled corticosteroids can be added to long-acting bronchodilator therapy but cannot be used as stand-alone therapy. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator that is used infrequently due to its narrow therapeutic index, toxicity, and multiple drug interactions.

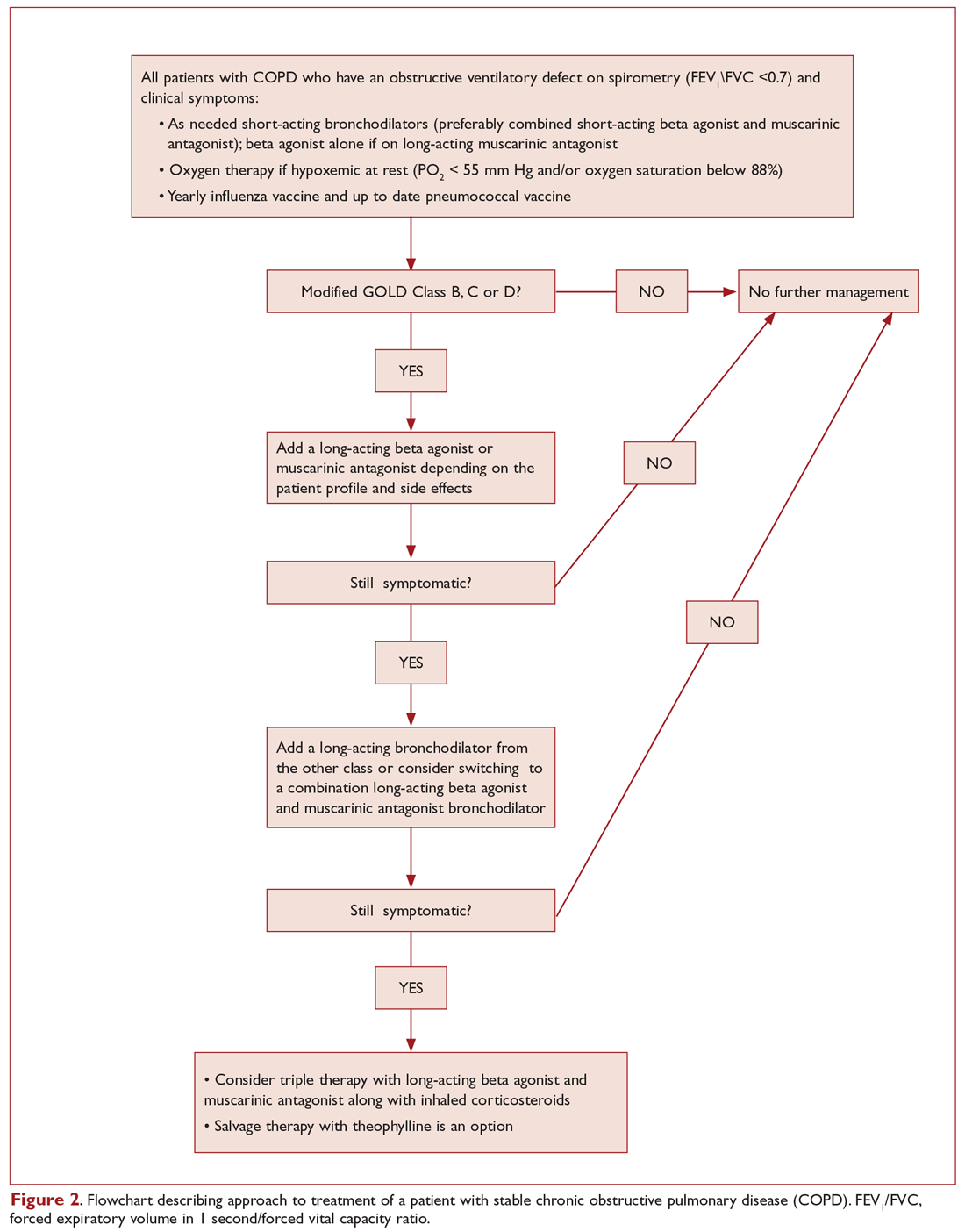

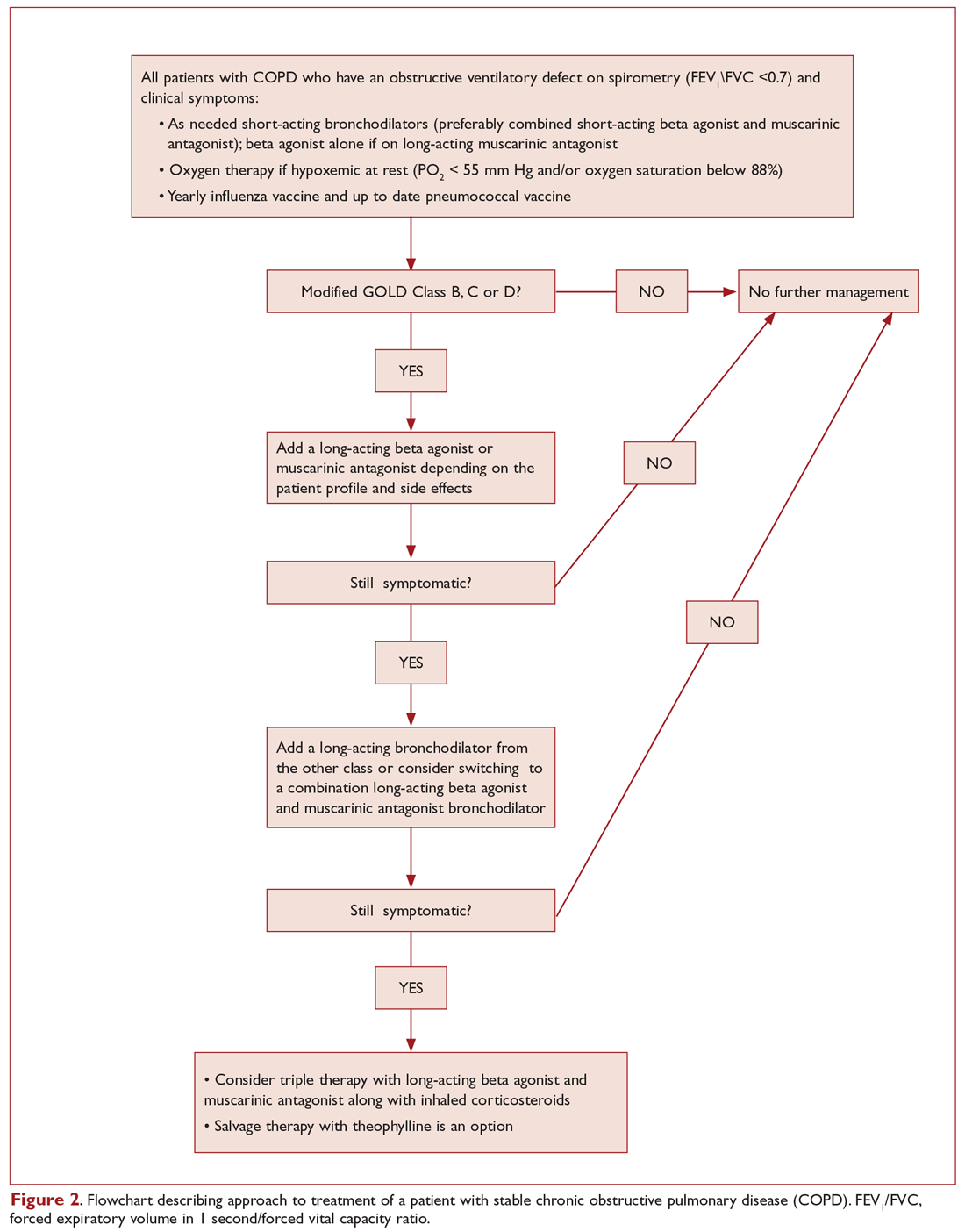

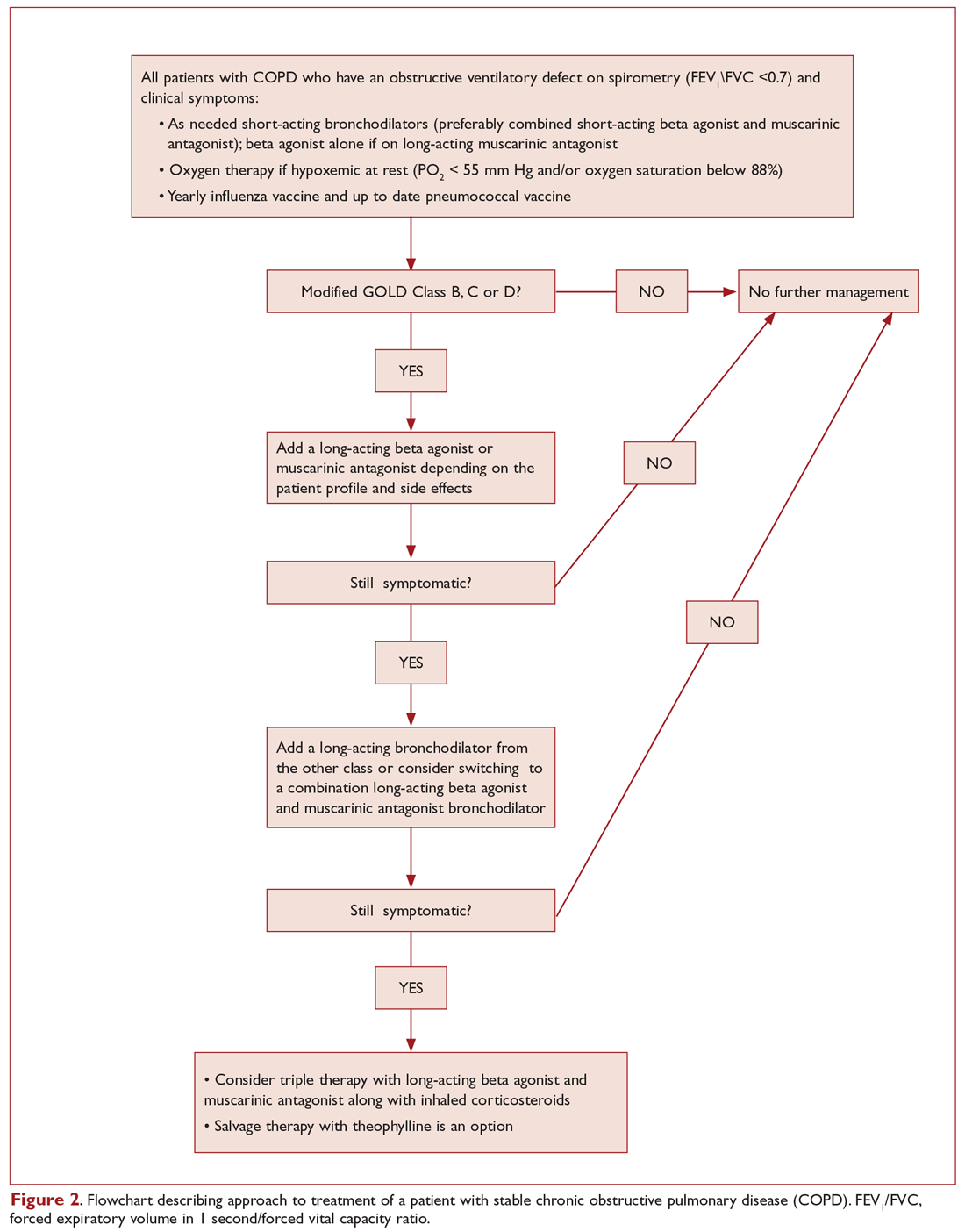

Figure 2 presents an approach to building a treatment plan for the patient with stable COPD.

Who should be on short-acting bronchodilators? What is the best agent? Should it be scheduled or used as needed?

All patients with COPD should be an on inhaled short-acting bronchodilator as needed for relief of symptoms.7 Both short-acting beta-agonists (albuterol and levalbuterol) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium) have been shown in clinical trials and meta-analyses to improve symptoms and lung function in patients with stable COPD9,10 and seem to have comparative efficacy when compared head-to-head in trials.11 However, the airway bronchodilator effect achieved by both classes seems to be additive when used in combination and is also associated with fewer exacerbations compared to albuterol alone.12 On the other hand, adding albuterol to ipratropium increased the bronchodilator response but did not reduce the exacerbation rate.11-13 Inhaled short-acting beta-agonists when used as needed rather than scheduled are associated with less medication use without any significant difference in symptoms or lung function.14

The side effects related to using recommended doses of a short-acting bronchodilator are minimal. In retrospective studies, short-acting beta-agonists increased the risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias.15 Levalbuterol, the active enantiomer of albuterol (R-albuterol) developed for the theoretical benefits of reduced tachycardia, increased tolerability, and better or equal efficacy compared to racemic albuterol, failed to show a clinically significant difference in inducing tachycardia.16 Beta-agonist overuse is associated with tremor and in severe cases hypokalemia, which happens mainly when patients try to achieve maximal bronchodilation; the clinically used doses of beta agonists are associated with fewer side effects but achieve less than maximal bronchodilation.17 Ipratropium can produce systemic anticholinergic side effects, urinary retention being the most clinically significant, especially when combined with long-acting anticholinergic agents.18

In light of the above discussion, a combination of a short-acting beta-agonist and a muscarinic antagonist is recommended in all patients with COPD, unless the patient is on a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA).7,18 In the latter case, a short-acting beta agonist used as a rescue inhaler is the best option. In our patient, albuterol was the choice for his short-acting bronchodilator, as he was using the LAMA tiotropium.

Are short-acting bronchodilators enough? What do we use for maintenance therapy?

All patients with COPD who are category B or higher according to the modified GOLD staging system should be on a long-acting bronchodilator:7,19 either a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) or a LAMA. Long-acting bronchodilators work on the same receptors as their short-acting counterparts but have structural differences. Salmeterol is the prototype long-acting selective beta-2 agonist. It is structurally similar to albuterol but has an elongated side chain that allows it to bind firmly to the area of beta receptors and stimulate them repetitively, resulting in an extended-duration of action.20 Tiotropium on the other hand is a quaternary ammonium of ipratropium that is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist.21 Compared to ipratropium, tiotropium dissociates more quickly from M2 receptors, which is responsible for the undesired anticholinergic effects, while at the same time it binds M1 and M3 receptors for a prolonged time, resulting in an extended duration of action.21 Revefenacin is a new lung-selective LAMA that is under development and has shown promise among those with moderate to very severe COPD. Results are only limited to phase 3 trials, and clinical studies are still underway.22

The currently available LABAs include salmeterol, formoterol, arformoterol, olodaterol, and indacaterol. The last 2 have the advantage of once-daily dosing rather than twice daily.23,24 LABAs have been shown to improve lung function, exacerbation rate, and quality of life in multiple clinical trials.23,25 Vilanterol is another LABA that has a long duration of action and can be used once daily,26 but is only available in a combination with umeclidinium, a LAMA. Several LAMAs are approved for use in COPD, including the prototype tiotropium, in addition to aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium. These have been shown in clinical trials to improve lung function, symptoms, and exacerbation rate.27-30

Patients can be started on either a LAMA or LABA depending on the individual patient's needs and the agent's adverse effects.7 Both have comparable adverse effects and efficacy, as detailed below. Concerning adverse effects, there is conflicting data concerning an association of cardiovascular events with both classes of long-acting bronchodilators. While clinical trials failed to show an increased risk,25,31,32 several retrospective studies showed an increased risk of emergency room visits and hospitalizations due to tachyarrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke upon initiation of long-acting bronchodilators.33,34 There was no difference in risk for adverse cardiovascular events between LABA and LAMA in 1 Canadian study, and slightly more with LABA in a study using an American database.33,34 Wang et al reported that the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects, defined as hospitalizations and emergency room visits from heart failure, arrythmia, stroke, or ischemia, was 1.5 times the baseline risk in the first 30 days of starting a LABA or LAMA.35 The risk was subsequently the same as baseline or even lower after that period. Urinary retention is another possible complication of LAMA supported by evidence from meta-analyses and retrospective studies, but not clinical trials; the possibility of urinary retention should be discussed with patients upon initiation.36,37 Concerns about increased mortality with the soft mist formulation of tiotropium were put to rest by the Tiotropium Safety and Performance in Respimat (TIOSPIR) trial, which showed no increased mortality compared to Handihaler.38

As far as efficacy and benefits, tiotropium and salmeterol were compared head-to-head in a clinical trial, and tiotropium increased the time before developing first exacerbation and decreased the overall rate of exacerbations.39 No difference in hospitalization rate or mortality was noted in 1 meta-analysis, although tiotropium was more effective in reducing exacerbations.40 The choice of agent should be made based on patient comorbidities and side effects. For example, an elderly patient with severe benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary retention should try a LABA, while a LAMA would be a better first agent for a patient with severe tachycardia induced by albuterol.

What is the role of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are believed to work in COPD by reducing airway inflammation.41 ICS should not be used alone for COPD management and are always combined with a LABA.7 Several ICS formulations are approved for use in COPD, including budesonide and fluticasone. ICS has been shown to decrease symptoms and exacerbations, with modest effect on lung function and no change in mortality.42 Side effects include oral candidiasis, dysphonia, and skin bruising.43 There is also an increased risk of pneumonia.44 ICS are best reserved for patients with a component of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS).45 ACOS is characterized by persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.46

What if the patient is still symptomatic on a LABA or LAMA?

For patients whose symptoms are not controlled on one class of LABA, recommendations are to add a bronchodilator from the other class.7 There are also multiple combined LAMA-LABA inhalers that are approved in the United States and can possibly improve adherence to therapy. These include tiotropium-olodaterol, umeclidinium-vilanterol, glycopyrronium-indacaterol, and glycopyrrolate-formoterol. In a large systematic review and meta-analysis comparing LABA-LAMA combination to either agent alone, there was a modest improvement in post-bronchodilator FEV1 and quality of life, with no change in hospital admissions, mortality, or adverse effects.47 Interestingly, adding tiotropium to LABA reduced exacerbations, although adding LABA to tiotropium did not.47

Current guidelines recommend that patients in GOLD categories C and D who are not well controlled should receive a combination of LABA-ICS.7 However, a new randomized trial showed better reduction of exacerbations and decreased occurrence of pneumonia in patients receiving LAMA-LABA compared to LABA-ICS.48 In light of this new evidence, it is prudent to use a LAMA-LABA combination before adding ICS.

Triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS is a common approach for patients with severe uncontrolled disease and has been shown to decrease exacerbations and improve quality of life.7,49 Adding tiotropium to LABA-ICS decreased exacerbations and improved quality of life and airflow in the landmark UPLIFT trial.27 In another clinical trial, triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS compared to tiotropium alone decreased severe exacerbations, pre-bronchodilator FEV1, and morning symptoms.50 A combination of triple therapy with fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol was recently noted to result in a lower rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations, preserve lung function, and maintain health-related quality of life, as compared with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or umeclidinium/vilanterol combination therapy among those with symptomatic COPD with a history of exacerbations.51

Is there a role for theophylline? Other agents?

Theophylline

Theophylline is an oral adenosine diphosphate antagonist with indirect adrenergic activity, which is responsible for the bronchodilator therapeutic effect in patients with obstructive lung disease. It is also thought to work by an additional mechanism that decreases inflammation in the airways.52 Theophylline has a serious adverse-effect profile that includes ventricular arrhythmias, seizures, vomiting, and tremor.53 It is metabolized in the liver and has multiple drug interactions and a narrow therapeutic index. It has been shown to improve lung function, gas exchange and symptoms in meta-analysis and clinical trials.54,55

In light of the nature of the adverse effects and the wide array of safer and more effective pharmacologic agents available, theophylline should be avoided early on in the treatment of COPD. Its use can be justified as an add-on therapy in patients with refractory disease on triple therapy for symptomatic relief.53 If used, the therapeutic range of theophylline for COPD is 8 to 12 mcg/mL peak level measured 3 to 7 hours after morning dose, and this level is usually achieved using a daily dose of 10 mg per kilogram of body weight for nonobese patients.56

Systemic Steroids

Oral steroids are used in COPD exacerbations but should never be used chronically in COPD patients, regardless of disease severity, as they increase morbidity and mortality without improving symptoms or lung function.57,58 The dose of systemic steroids should be tapered and finally discontinued.

Mucolytics

Classes of mucolytics include thiol derivatives, inhaled dornase alfa, hypertonic saline, and iodine preparations. Thiol derivatives such as N-acetylcysteine are the most widely studied.59 There is no consistent evidence of beneficial role of mucolytics in COPD patients.7,59 The PANTHEON trial showed decreased exacerbations with N-acetylcysteine (1.16 exacerbations per patient-year compared to 1.49 exacerbations per patient-year in the placebo group; risk ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.90; P = 0.001) but had methodologic issues including high drop-out rate, exclusion of patients on oxygen, and a large of proportion of nonsmokers.60

Long-Term Antibiotics

There is no role for long-term antibiotics in the management of COPD.7 Macrolides are an exception but are used for their anti-inflammatory effects rather than their antibiotic effects. They should be reserved for patients with frequent exacerbations on optimal therapy and will be discussed later in the review.61

What nonpharmacologic treatments are recommended for COPD patients?

Smoking cessation, oxygen therapy for severe hypoxemia (resting O2 saturation ≤ 88% or PaO2 ≤ 55 mm Hg), vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus, and appropriate nutrition should be provided in all COPD patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation is indicated for patients in GOLD categories B, C, and D.7 It improves symptoms, quality of life, exercise tolerance, and health care utilization. Beneficial effects last for about 2 years.62,63

What other diagnoses should be considered in patients who continue to be symptomatic on optimal therapy?

Other diseases that share the same risk factors as COPD and can contribute to dyspnea, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, thromboembolic disease, and pulmonary hypertension, should be considered. In addition, all patients with refractory disease should have a careful assessment of their inhaler technique, continued smoking, need for oxygen therapy, and associated deconditioning.

1. Segreti A, Stirpe E, Rogliani P, Cazzola M. Defining phenotypes in COPD: an aid to personalized healthcare. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18:381-388.

2. Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:598-604.

3. Aubier M, Marthan R, Berger P, et al. [COPD and inflammation: statement from a French expert group: inflammation and remodelling mechanisms]. Rev Mal Respir. 2010;27:1254-1266.

4. Wang ZL. Evolving role of systemic inflammation in comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:3467-3478.

5. Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370:741-750.

6. Miniño AM, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59:1-126.

7. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD 2017. www.goldcopd.org. Accessed July 9, 2019.

8. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:648-654.

9. Wadbo M, Löfdahl CG, Larsson K, et al. Effects of formoterol and ipratropium bromide in COPD: a 3-month placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1138-1146.

10. Ram FS, Sestini P. Regular inhaled short acting beta2 agonists for the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2003;58:580-584.

11. Colice GL. Nebulized bronchodilators for outpatient management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1996;100(1A):11S-8S.

12. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a combination of ipratropium and albuterol is more effective than either agent alone. An 85-day multicenter trial. COMBIVENT Inhalation Aerosol Study Group. Chest. 1994;105:1411-1419.

13. Friedman M, Serby CW, Menjoge SS, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a combination of ipratropium plus albuterol compared with ipratropium alone and albuterol alone in COPD. Chest. 1999;115:635-641.

14. Cook D, Guyatt G, Wong E, et al. Regular versus as-needed short-acting inhaled beta-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:85-90.

15. Wilchesky M, Ernst P, Brophy JM, et al. Bronchodilator use and the risk of arrhythmia in COPD: part 2: reassessment in the larger Quebec cohort. Chest. 2012;142:305-311.

16. Scott VL, Frazee LA. Retrospective comparison of nebulized levalbuterol and albuterol for adverse events in patients with acute airflow obstruction. Am J Ther. 2003;10:341-347.

17. Wong CS, Pavord ID, Williams J, et al. Bronchodilator, cardiovascular, and hypokalaemic effects of fenoterol, salbutamol, and terbutaline in asthma. Lancet. 1990;336:1396-1399.

18. Cole JM, Sheehan AH, Jordan JK. Concomitant use of ipratropium and tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1717-1721.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

20. Pearlman DS, Chervinsky P, LaForce C, et al. A comparison of salmeterol with albuterol in the treatment of mild-to-moderate asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1420-1425.

21. Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(6 Pt 1):1640-1645.

22. Ferguson GT, Feldman G, Pudi KK, et al. improvements in lung function with nebulized revefenacin in the treatment of patients with moderate to very severe COPD: results from two replicate phase III clinical trials. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;6:154-165.

23. Donohue JF, Fogarty C, Lötvall J, et al. Once-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol versus tiotropium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:155-162.

24. Koch A, Pizzichini E, Hamilton A, et al. Lung function efficacy and symptomatic benefit of olodaterol once daily delivered via Respimat versus placebo and formoterol twice daily in patients with GOLD 2-4 COPD: results from two replicate 48-week studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:697-714.

25. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:775-789.

26. Hanania NA, Feldman G, Zachgo W, et al. The efficacy and safety of the novel long-acting β2 agonist vilanterol in patients with COPD: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Chest. 2012;142:119-127.

27. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543-1554.

28. Decramer ML, Chapman KR, Dahl R, et al. Once-daily indacaterol versus tiotropium for patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (INVIGORATE): a randomised, blinded, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:524-533.

29. Jones PW, Singh D, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily aclidinium bromide in COPD patients: the ATTAIN study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:830-836.

30. D’Urzo A, Ferguson GT, van Noord JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily NVA237 in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: the GLOW1 trial. Respir Res. 2011;12:156.

31. Antoniu SA. UPLIFT Study: the effects of long-term therapy with inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evaluation of: Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543-1554. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:719–22.

32. Nelson HS, Gross NJ, Levine B, et al. Cardiac safety profile of nebulized formoterol in adults with COPD: a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double- blind, double-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2167-2178.

33. Gershon A, Croxford R, Calzavara A, et al. Cardiovascular safety of inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1175-1185.

34. Aljaafareh A, Valle JR, Lin YL, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events after initiation of long-acting bronchodilators in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease: A population-based study. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116671337.

35. Wang MT, Liou JT, Lin CW, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk with inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nested case-Control Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:229-238.

36. O’Connor AB. Tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:185-186.

37. Kesten S, Jara M, Wentworth C, Lanes S. Pooled clinical trial analysis of tiotropium safety. Chest. 2006;130:1695-1703.

38. Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D, et al. Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1491-1501.

39. Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1093-1103.

40. Chong J, Karner C, Poole P. Tiotropium versus long-acting beta-agonists for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):CD009157.

41. Gan WQ, Man SF, Sin DD. Effects of inhaled corticosteroids on sputum cell counts in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2005;5:3.

42. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(7):CD002991.

43. Roland NJ, Bhalla RK, Earis J. The local side effects of inhaled corticosteroids: current understanding and review of the literature. Chest. 2004;126:213-219.

44. Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2407-2416.

45. Lee SY, Park HY, Kim EK, et al. Combination therapy of inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists in asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2797-2803.

46. Postma DS, Rabe KF. The asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1241-1249.

47. Farne HA, Cates CJ. Long-acting beta2-agonist in addition to tiotropium versus either tiotropium or long-acting beta2-agonist alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD008989.

48. Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2222-2234.

49. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:545-555.

50. Welte T, Miravitlles M, Hernandez P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:741-750.

51. Lipson DA, Barnhart, Brealey N, et al; IMPACT Investigators. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1671-1680.

52. Gallelli L, Falcone D, Cannataro R, et al. Theophylline action on primary human bronchial epithelial cells under proinflammatory stimuli and steroidal drugs: a therapeutic rationale approach. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:265-272.

53. Paloucek FP, Rodvold KA. Evaluation of theophylline overdoses and toxicities. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:135-144.

54. Ram FS, Jones PW, Castro AA, et al. Oral theophylline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(4):CD003902.

55. Murciano D, Auclair MH, Pariente R, Aubier M. A randomized, controlled trial of theophylline in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1521-1525.

56. Devereux G, Cotton S, Barnes P, et al. Use of low-dose oral theophylline as an adjunct to inhaled corticosteroids in preventing exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:267.

57. Walters JA, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Oral corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(3):CD005374.

58. Horita N, Miyazawa N, Morita S, et al. Evidence suggesting that oral corticosteroids increase mortality in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2014;15:37.

59. Poole P, Chong J, Cates CJ. Mucolytic agents versus placebo for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(7):CD001287.

60. Zheng JP, Wen FQ, Bai CX, et al. Twice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:187-194.

61. Seemungal TA, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, et al. Long-term erythromycin therapy is associated with decreased chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1139-1147.

62. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM, Prewitt LM. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:823-832.

63. Güell R, Casan P, Belda J, et al. Long-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation of COPD: a randomized trial. Chest. 2000;117:976-983.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by irreversible obstructive ventilatory defects.1-4 It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting 5% of the population in the United States and ranking as the third leading cause of death in 2008.5,6 The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. In this 3-part review, we discuss the management of stable COPD in the context of 3 common clinical scenarios: initiating and optimizing therapy, managing acute exacerbations, and managing advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man with COPD underwent pulmonary function testing (PFT), which demonstrated an obstructive ventilatory defect: forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio (FEV1/FVC), 0.45; FEV1, 2 L (65% of predicted); and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, 15 mL/min/mm Hg (65% of predicted). He has dyspnea with strenuous exercise but is comfortable at rest and with minimal exercise. He has had 1 exacerbation in the past year, and this was treated on an outpatient basis with steroids and antibiotics. His medication regimen includes inhaled tiotropium once daily and inhaled albuterol as needed that he uses roughly twice a week.

What determines the appropriate therapy for a given COPD patient?

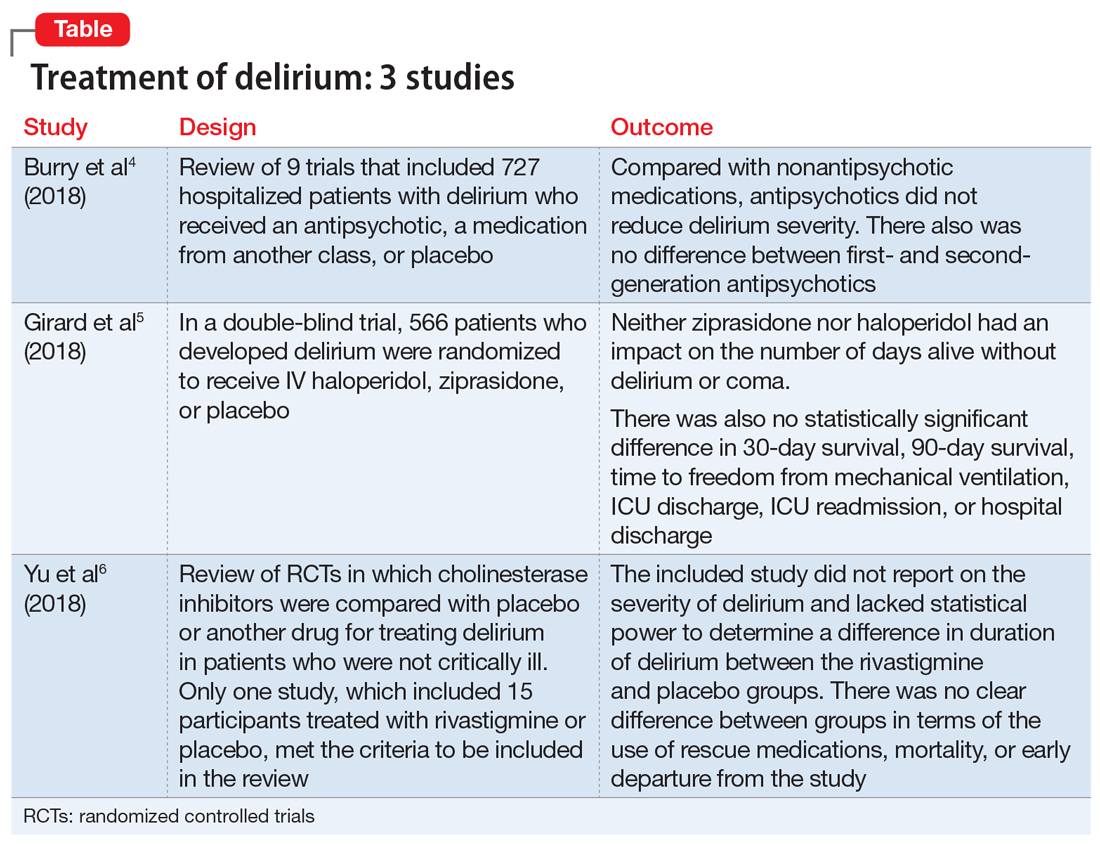

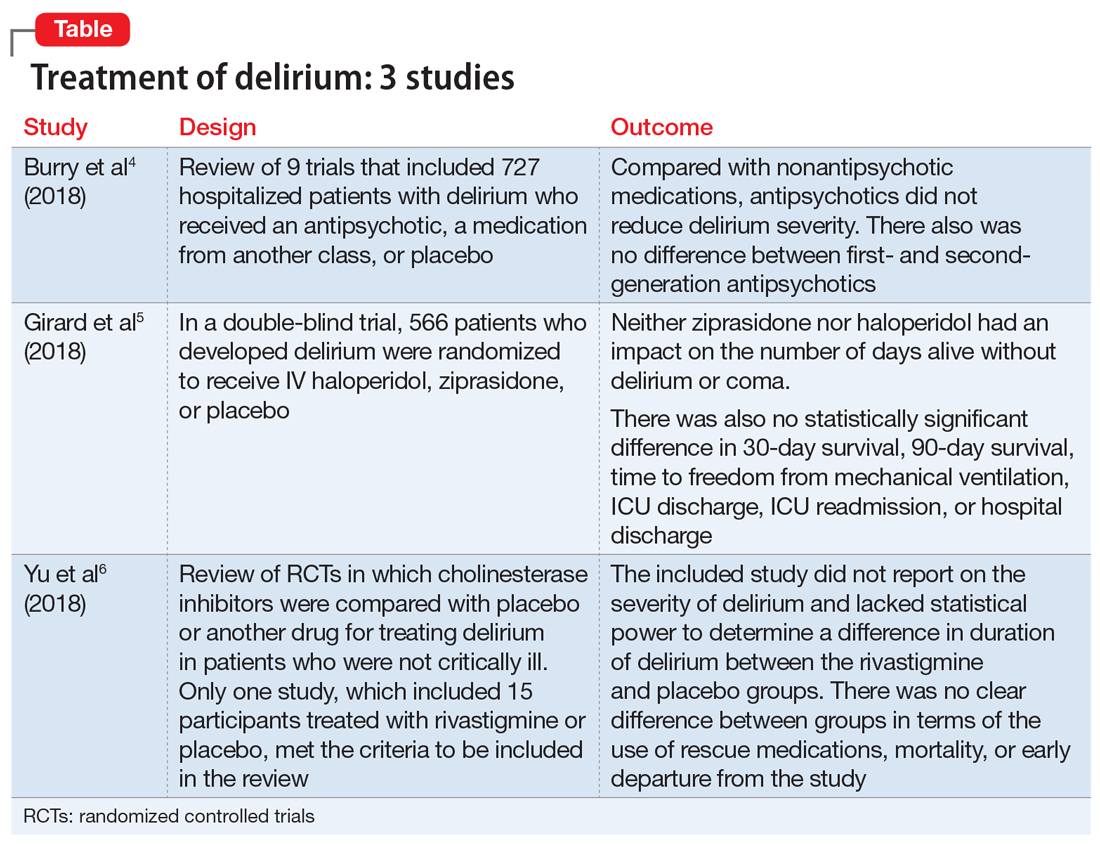

COPD management is guided by disease severity that is measured using a multimodal staging system developed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). The initial classification adopted by the GOLD 2011 report encompassed 4 categories based on symptoms, number of exacerbations, and degree of airflow limitation on PFT. However, in 2017 the GOLD ABCD classification was modified to consider only symptoms and risk of exacerbation in classifying patients, regardless of performance on spirometry and FEV1 (Figure 1).7,8 This approach was intended to make therapy more individualized based on the patient clinical profile. The Table provides a summary of the recommended treatments according to classification based on the GOLD 2017 report.

The patient in our clinical scenario can be classified as GOLD category B.

What is the approach to building a pharmacologic regimen for the patient with COPD?

The backbone of the pharmacologic regimen for COPD includes short- and long-acting bronchodilators. They are usually given in an inhaled form to maximize local effects on the lungs and minimize systemic side effects. There are 2 main classes of bronchodilators, beta-agonists and muscarinic antagonists, and each targets specific receptors on the surface of airway smooth muscle cells. Beta- agonists work by stimulating beta-2 receptors, resulting in bronchodilation, while muscarinic antagonists work by blocking the bronchoconstrictor action of M3 muscarinic receptors. Inhaled corticosteroids can be added to long-acting bronchodilator therapy but cannot be used as stand-alone therapy. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator that is used infrequently due to its narrow therapeutic index, toxicity, and multiple drug interactions.

Figure 2 presents an approach to building a treatment plan for the patient with stable COPD.

Who should be on short-acting bronchodilators? What is the best agent? Should it be scheduled or used as needed?

All patients with COPD should be an on inhaled short-acting bronchodilator as needed for relief of symptoms.7 Both short-acting beta-agonists (albuterol and levalbuterol) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium) have been shown in clinical trials and meta-analyses to improve symptoms and lung function in patients with stable COPD9,10 and seem to have comparative efficacy when compared head-to-head in trials.11 However, the airway bronchodilator effect achieved by both classes seems to be additive when used in combination and is also associated with fewer exacerbations compared to albuterol alone.12 On the other hand, adding albuterol to ipratropium increased the bronchodilator response but did not reduce the exacerbation rate.11-13 Inhaled short-acting beta-agonists when used as needed rather than scheduled are associated with less medication use without any significant difference in symptoms or lung function.14

The side effects related to using recommended doses of a short-acting bronchodilator are minimal. In retrospective studies, short-acting beta-agonists increased the risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias.15 Levalbuterol, the active enantiomer of albuterol (R-albuterol) developed for the theoretical benefits of reduced tachycardia, increased tolerability, and better or equal efficacy compared to racemic albuterol, failed to show a clinically significant difference in inducing tachycardia.16 Beta-agonist overuse is associated with tremor and in severe cases hypokalemia, which happens mainly when patients try to achieve maximal bronchodilation; the clinically used doses of beta agonists are associated with fewer side effects but achieve less than maximal bronchodilation.17 Ipratropium can produce systemic anticholinergic side effects, urinary retention being the most clinically significant, especially when combined with long-acting anticholinergic agents.18

In light of the above discussion, a combination of a short-acting beta-agonist and a muscarinic antagonist is recommended in all patients with COPD, unless the patient is on a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA).7,18 In the latter case, a short-acting beta agonist used as a rescue inhaler is the best option. In our patient, albuterol was the choice for his short-acting bronchodilator, as he was using the LAMA tiotropium.

Are short-acting bronchodilators enough? What do we use for maintenance therapy?

All patients with COPD who are category B or higher according to the modified GOLD staging system should be on a long-acting bronchodilator:7,19 either a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) or a LAMA. Long-acting bronchodilators work on the same receptors as their short-acting counterparts but have structural differences. Salmeterol is the prototype long-acting selective beta-2 agonist. It is structurally similar to albuterol but has an elongated side chain that allows it to bind firmly to the area of beta receptors and stimulate them repetitively, resulting in an extended-duration of action.20 Tiotropium on the other hand is a quaternary ammonium of ipratropium that is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist.21 Compared to ipratropium, tiotropium dissociates more quickly from M2 receptors, which is responsible for the undesired anticholinergic effects, while at the same time it binds M1 and M3 receptors for a prolonged time, resulting in an extended duration of action.21 Revefenacin is a new lung-selective LAMA that is under development and has shown promise among those with moderate to very severe COPD. Results are only limited to phase 3 trials, and clinical studies are still underway.22

The currently available LABAs include salmeterol, formoterol, arformoterol, olodaterol, and indacaterol. The last 2 have the advantage of once-daily dosing rather than twice daily.23,24 LABAs have been shown to improve lung function, exacerbation rate, and quality of life in multiple clinical trials.23,25 Vilanterol is another LABA that has a long duration of action and can be used once daily,26 but is only available in a combination with umeclidinium, a LAMA. Several LAMAs are approved for use in COPD, including the prototype tiotropium, in addition to aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium. These have been shown in clinical trials to improve lung function, symptoms, and exacerbation rate.27-30

Patients can be started on either a LAMA or LABA depending on the individual patient's needs and the agent's adverse effects.7 Both have comparable adverse effects and efficacy, as detailed below. Concerning adverse effects, there is conflicting data concerning an association of cardiovascular events with both classes of long-acting bronchodilators. While clinical trials failed to show an increased risk,25,31,32 several retrospective studies showed an increased risk of emergency room visits and hospitalizations due to tachyarrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke upon initiation of long-acting bronchodilators.33,34 There was no difference in risk for adverse cardiovascular events between LABA and LAMA in 1 Canadian study, and slightly more with LABA in a study using an American database.33,34 Wang et al reported that the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects, defined as hospitalizations and emergency room visits from heart failure, arrythmia, stroke, or ischemia, was 1.5 times the baseline risk in the first 30 days of starting a LABA or LAMA.35 The risk was subsequently the same as baseline or even lower after that period. Urinary retention is another possible complication of LAMA supported by evidence from meta-analyses and retrospective studies, but not clinical trials; the possibility of urinary retention should be discussed with patients upon initiation.36,37 Concerns about increased mortality with the soft mist formulation of tiotropium were put to rest by the Tiotropium Safety and Performance in Respimat (TIOSPIR) trial, which showed no increased mortality compared to Handihaler.38

As far as efficacy and benefits, tiotropium and salmeterol were compared head-to-head in a clinical trial, and tiotropium increased the time before developing first exacerbation and decreased the overall rate of exacerbations.39 No difference in hospitalization rate or mortality was noted in 1 meta-analysis, although tiotropium was more effective in reducing exacerbations.40 The choice of agent should be made based on patient comorbidities and side effects. For example, an elderly patient with severe benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary retention should try a LABA, while a LAMA would be a better first agent for a patient with severe tachycardia induced by albuterol.

What is the role of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are believed to work in COPD by reducing airway inflammation.41 ICS should not be used alone for COPD management and are always combined with a LABA.7 Several ICS formulations are approved for use in COPD, including budesonide and fluticasone. ICS has been shown to decrease symptoms and exacerbations, with modest effect on lung function and no change in mortality.42 Side effects include oral candidiasis, dysphonia, and skin bruising.43 There is also an increased risk of pneumonia.44 ICS are best reserved for patients with a component of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS).45 ACOS is characterized by persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.46

What if the patient is still symptomatic on a LABA or LAMA?

For patients whose symptoms are not controlled on one class of LABA, recommendations are to add a bronchodilator from the other class.7 There are also multiple combined LAMA-LABA inhalers that are approved in the United States and can possibly improve adherence to therapy. These include tiotropium-olodaterol, umeclidinium-vilanterol, glycopyrronium-indacaterol, and glycopyrrolate-formoterol. In a large systematic review and meta-analysis comparing LABA-LAMA combination to either agent alone, there was a modest improvement in post-bronchodilator FEV1 and quality of life, with no change in hospital admissions, mortality, or adverse effects.47 Interestingly, adding tiotropium to LABA reduced exacerbations, although adding LABA to tiotropium did not.47

Current guidelines recommend that patients in GOLD categories C and D who are not well controlled should receive a combination of LABA-ICS.7 However, a new randomized trial showed better reduction of exacerbations and decreased occurrence of pneumonia in patients receiving LAMA-LABA compared to LABA-ICS.48 In light of this new evidence, it is prudent to use a LAMA-LABA combination before adding ICS.

Triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS is a common approach for patients with severe uncontrolled disease and has been shown to decrease exacerbations and improve quality of life.7,49 Adding tiotropium to LABA-ICS decreased exacerbations and improved quality of life and airflow in the landmark UPLIFT trial.27 In another clinical trial, triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS compared to tiotropium alone decreased severe exacerbations, pre-bronchodilator FEV1, and morning symptoms.50 A combination of triple therapy with fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol was recently noted to result in a lower rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations, preserve lung function, and maintain health-related quality of life, as compared with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or umeclidinium/vilanterol combination therapy among those with symptomatic COPD with a history of exacerbations.51

Is there a role for theophylline? Other agents?

Theophylline

Theophylline is an oral adenosine diphosphate antagonist with indirect adrenergic activity, which is responsible for the bronchodilator therapeutic effect in patients with obstructive lung disease. It is also thought to work by an additional mechanism that decreases inflammation in the airways.52 Theophylline has a serious adverse-effect profile that includes ventricular arrhythmias, seizures, vomiting, and tremor.53 It is metabolized in the liver and has multiple drug interactions and a narrow therapeutic index. It has been shown to improve lung function, gas exchange and symptoms in meta-analysis and clinical trials.54,55

In light of the nature of the adverse effects and the wide array of safer and more effective pharmacologic agents available, theophylline should be avoided early on in the treatment of COPD. Its use can be justified as an add-on therapy in patients with refractory disease on triple therapy for symptomatic relief.53 If used, the therapeutic range of theophylline for COPD is 8 to 12 mcg/mL peak level measured 3 to 7 hours after morning dose, and this level is usually achieved using a daily dose of 10 mg per kilogram of body weight for nonobese patients.56

Systemic Steroids

Oral steroids are used in COPD exacerbations but should never be used chronically in COPD patients, regardless of disease severity, as they increase morbidity and mortality without improving symptoms or lung function.57,58 The dose of systemic steroids should be tapered and finally discontinued.

Mucolytics

Classes of mucolytics include thiol derivatives, inhaled dornase alfa, hypertonic saline, and iodine preparations. Thiol derivatives such as N-acetylcysteine are the most widely studied.59 There is no consistent evidence of beneficial role of mucolytics in COPD patients.7,59 The PANTHEON trial showed decreased exacerbations with N-acetylcysteine (1.16 exacerbations per patient-year compared to 1.49 exacerbations per patient-year in the placebo group; risk ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.90; P = 0.001) but had methodologic issues including high drop-out rate, exclusion of patients on oxygen, and a large of proportion of nonsmokers.60

Long-Term Antibiotics

There is no role for long-term antibiotics in the management of COPD.7 Macrolides are an exception but are used for their anti-inflammatory effects rather than their antibiotic effects. They should be reserved for patients with frequent exacerbations on optimal therapy and will be discussed later in the review.61

What nonpharmacologic treatments are recommended for COPD patients?

Smoking cessation, oxygen therapy for severe hypoxemia (resting O2 saturation ≤ 88% or PaO2 ≤ 55 mm Hg), vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus, and appropriate nutrition should be provided in all COPD patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation is indicated for patients in GOLD categories B, C, and D.7 It improves symptoms, quality of life, exercise tolerance, and health care utilization. Beneficial effects last for about 2 years.62,63

What other diagnoses should be considered in patients who continue to be symptomatic on optimal therapy?

Other diseases that share the same risk factors as COPD and can contribute to dyspnea, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, thromboembolic disease, and pulmonary hypertension, should be considered. In addition, all patients with refractory disease should have a careful assessment of their inhaler technique, continued smoking, need for oxygen therapy, and associated deconditioning.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by irreversible obstructive ventilatory defects.1-4 It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting 5% of the population in the United States and ranking as the third leading cause of death in 2008.5,6 The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. In this 3-part review, we discuss the management of stable COPD in the context of 3 common clinical scenarios: initiating and optimizing therapy, managing acute exacerbations, and managing advanced disease.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man with COPD underwent pulmonary function testing (PFT), which demonstrated an obstructive ventilatory defect: forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio (FEV1/FVC), 0.45; FEV1, 2 L (65% of predicted); and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, 15 mL/min/mm Hg (65% of predicted). He has dyspnea with strenuous exercise but is comfortable at rest and with minimal exercise. He has had 1 exacerbation in the past year, and this was treated on an outpatient basis with steroids and antibiotics. His medication regimen includes inhaled tiotropium once daily and inhaled albuterol as needed that he uses roughly twice a week.

What determines the appropriate therapy for a given COPD patient?

COPD management is guided by disease severity that is measured using a multimodal staging system developed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). The initial classification adopted by the GOLD 2011 report encompassed 4 categories based on symptoms, number of exacerbations, and degree of airflow limitation on PFT. However, in 2017 the GOLD ABCD classification was modified to consider only symptoms and risk of exacerbation in classifying patients, regardless of performance on spirometry and FEV1 (Figure 1).7,8 This approach was intended to make therapy more individualized based on the patient clinical profile. The Table provides a summary of the recommended treatments according to classification based on the GOLD 2017 report.

The patient in our clinical scenario can be classified as GOLD category B.

What is the approach to building a pharmacologic regimen for the patient with COPD?

The backbone of the pharmacologic regimen for COPD includes short- and long-acting bronchodilators. They are usually given in an inhaled form to maximize local effects on the lungs and minimize systemic side effects. There are 2 main classes of bronchodilators, beta-agonists and muscarinic antagonists, and each targets specific receptors on the surface of airway smooth muscle cells. Beta- agonists work by stimulating beta-2 receptors, resulting in bronchodilation, while muscarinic antagonists work by blocking the bronchoconstrictor action of M3 muscarinic receptors. Inhaled corticosteroids can be added to long-acting bronchodilator therapy but cannot be used as stand-alone therapy. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator that is used infrequently due to its narrow therapeutic index, toxicity, and multiple drug interactions.

Figure 2 presents an approach to building a treatment plan for the patient with stable COPD.

Who should be on short-acting bronchodilators? What is the best agent? Should it be scheduled or used as needed?

All patients with COPD should be an on inhaled short-acting bronchodilator as needed for relief of symptoms.7 Both short-acting beta-agonists (albuterol and levalbuterol) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium) have been shown in clinical trials and meta-analyses to improve symptoms and lung function in patients with stable COPD9,10 and seem to have comparative efficacy when compared head-to-head in trials.11 However, the airway bronchodilator effect achieved by both classes seems to be additive when used in combination and is also associated with fewer exacerbations compared to albuterol alone.12 On the other hand, adding albuterol to ipratropium increased the bronchodilator response but did not reduce the exacerbation rate.11-13 Inhaled short-acting beta-agonists when used as needed rather than scheduled are associated with less medication use without any significant difference in symptoms or lung function.14

The side effects related to using recommended doses of a short-acting bronchodilator are minimal. In retrospective studies, short-acting beta-agonists increased the risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias.15 Levalbuterol, the active enantiomer of albuterol (R-albuterol) developed for the theoretical benefits of reduced tachycardia, increased tolerability, and better or equal efficacy compared to racemic albuterol, failed to show a clinically significant difference in inducing tachycardia.16 Beta-agonist overuse is associated with tremor and in severe cases hypokalemia, which happens mainly when patients try to achieve maximal bronchodilation; the clinically used doses of beta agonists are associated with fewer side effects but achieve less than maximal bronchodilation.17 Ipratropium can produce systemic anticholinergic side effects, urinary retention being the most clinically significant, especially when combined with long-acting anticholinergic agents.18

In light of the above discussion, a combination of a short-acting beta-agonist and a muscarinic antagonist is recommended in all patients with COPD, unless the patient is on a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA).7,18 In the latter case, a short-acting beta agonist used as a rescue inhaler is the best option. In our patient, albuterol was the choice for his short-acting bronchodilator, as he was using the LAMA tiotropium.

Are short-acting bronchodilators enough? What do we use for maintenance therapy?

All patients with COPD who are category B or higher according to the modified GOLD staging system should be on a long-acting bronchodilator:7,19 either a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) or a LAMA. Long-acting bronchodilators work on the same receptors as their short-acting counterparts but have structural differences. Salmeterol is the prototype long-acting selective beta-2 agonist. It is structurally similar to albuterol but has an elongated side chain that allows it to bind firmly to the area of beta receptors and stimulate them repetitively, resulting in an extended-duration of action.20 Tiotropium on the other hand is a quaternary ammonium of ipratropium that is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist.21 Compared to ipratropium, tiotropium dissociates more quickly from M2 receptors, which is responsible for the undesired anticholinergic effects, while at the same time it binds M1 and M3 receptors for a prolonged time, resulting in an extended duration of action.21 Revefenacin is a new lung-selective LAMA that is under development and has shown promise among those with moderate to very severe COPD. Results are only limited to phase 3 trials, and clinical studies are still underway.22

The currently available LABAs include salmeterol, formoterol, arformoterol, olodaterol, and indacaterol. The last 2 have the advantage of once-daily dosing rather than twice daily.23,24 LABAs have been shown to improve lung function, exacerbation rate, and quality of life in multiple clinical trials.23,25 Vilanterol is another LABA that has a long duration of action and can be used once daily,26 but is only available in a combination with umeclidinium, a LAMA. Several LAMAs are approved for use in COPD, including the prototype tiotropium, in addition to aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium. These have been shown in clinical trials to improve lung function, symptoms, and exacerbation rate.27-30

Patients can be started on either a LAMA or LABA depending on the individual patient's needs and the agent's adverse effects.7 Both have comparable adverse effects and efficacy, as detailed below. Concerning adverse effects, there is conflicting data concerning an association of cardiovascular events with both classes of long-acting bronchodilators. While clinical trials failed to show an increased risk,25,31,32 several retrospective studies showed an increased risk of emergency room visits and hospitalizations due to tachyarrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke upon initiation of long-acting bronchodilators.33,34 There was no difference in risk for adverse cardiovascular events between LABA and LAMA in 1 Canadian study, and slightly more with LABA in a study using an American database.33,34 Wang et al reported that the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects, defined as hospitalizations and emergency room visits from heart failure, arrythmia, stroke, or ischemia, was 1.5 times the baseline risk in the first 30 days of starting a LABA or LAMA.35 The risk was subsequently the same as baseline or even lower after that period. Urinary retention is another possible complication of LAMA supported by evidence from meta-analyses and retrospective studies, but not clinical trials; the possibility of urinary retention should be discussed with patients upon initiation.36,37 Concerns about increased mortality with the soft mist formulation of tiotropium were put to rest by the Tiotropium Safety and Performance in Respimat (TIOSPIR) trial, which showed no increased mortality compared to Handihaler.38

As far as efficacy and benefits, tiotropium and salmeterol were compared head-to-head in a clinical trial, and tiotropium increased the time before developing first exacerbation and decreased the overall rate of exacerbations.39 No difference in hospitalization rate or mortality was noted in 1 meta-analysis, although tiotropium was more effective in reducing exacerbations.40 The choice of agent should be made based on patient comorbidities and side effects. For example, an elderly patient with severe benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary retention should try a LABA, while a LAMA would be a better first agent for a patient with severe tachycardia induced by albuterol.

What is the role of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are believed to work in COPD by reducing airway inflammation.41 ICS should not be used alone for COPD management and are always combined with a LABA.7 Several ICS formulations are approved for use in COPD, including budesonide and fluticasone. ICS has been shown to decrease symptoms and exacerbations, with modest effect on lung function and no change in mortality.42 Side effects include oral candidiasis, dysphonia, and skin bruising.43 There is also an increased risk of pneumonia.44 ICS are best reserved for patients with a component of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS).45 ACOS is characterized by persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.46

What if the patient is still symptomatic on a LABA or LAMA?

For patients whose symptoms are not controlled on one class of LABA, recommendations are to add a bronchodilator from the other class.7 There are also multiple combined LAMA-LABA inhalers that are approved in the United States and can possibly improve adherence to therapy. These include tiotropium-olodaterol, umeclidinium-vilanterol, glycopyrronium-indacaterol, and glycopyrrolate-formoterol. In a large systematic review and meta-analysis comparing LABA-LAMA combination to either agent alone, there was a modest improvement in post-bronchodilator FEV1 and quality of life, with no change in hospital admissions, mortality, or adverse effects.47 Interestingly, adding tiotropium to LABA reduced exacerbations, although adding LABA to tiotropium did not.47

Current guidelines recommend that patients in GOLD categories C and D who are not well controlled should receive a combination of LABA-ICS.7 However, a new randomized trial showed better reduction of exacerbations and decreased occurrence of pneumonia in patients receiving LAMA-LABA compared to LABA-ICS.48 In light of this new evidence, it is prudent to use a LAMA-LABA combination before adding ICS.

Triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS is a common approach for patients with severe uncontrolled disease and has been shown to decrease exacerbations and improve quality of life.7,49 Adding tiotropium to LABA-ICS decreased exacerbations and improved quality of life and airflow in the landmark UPLIFT trial.27 In another clinical trial, triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS compared to tiotropium alone decreased severe exacerbations, pre-bronchodilator FEV1, and morning symptoms.50 A combination of triple therapy with fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol was recently noted to result in a lower rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations, preserve lung function, and maintain health-related quality of life, as compared with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or umeclidinium/vilanterol combination therapy among those with symptomatic COPD with a history of exacerbations.51

Is there a role for theophylline? Other agents?

Theophylline

Theophylline is an oral adenosine diphosphate antagonist with indirect adrenergic activity, which is responsible for the bronchodilator therapeutic effect in patients with obstructive lung disease. It is also thought to work by an additional mechanism that decreases inflammation in the airways.52 Theophylline has a serious adverse-effect profile that includes ventricular arrhythmias, seizures, vomiting, and tremor.53 It is metabolized in the liver and has multiple drug interactions and a narrow therapeutic index. It has been shown to improve lung function, gas exchange and symptoms in meta-analysis and clinical trials.54,55

In light of the nature of the adverse effects and the wide array of safer and more effective pharmacologic agents available, theophylline should be avoided early on in the treatment of COPD. Its use can be justified as an add-on therapy in patients with refractory disease on triple therapy for symptomatic relief.53 If used, the therapeutic range of theophylline for COPD is 8 to 12 mcg/mL peak level measured 3 to 7 hours after morning dose, and this level is usually achieved using a daily dose of 10 mg per kilogram of body weight for nonobese patients.56

Systemic Steroids

Oral steroids are used in COPD exacerbations but should never be used chronically in COPD patients, regardless of disease severity, as they increase morbidity and mortality without improving symptoms or lung function.57,58 The dose of systemic steroids should be tapered and finally discontinued.

Mucolytics

Classes of mucolytics include thiol derivatives, inhaled dornase alfa, hypertonic saline, and iodine preparations. Thiol derivatives such as N-acetylcysteine are the most widely studied.59 There is no consistent evidence of beneficial role of mucolytics in COPD patients.7,59 The PANTHEON trial showed decreased exacerbations with N-acetylcysteine (1.16 exacerbations per patient-year compared to 1.49 exacerbations per patient-year in the placebo group; risk ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.90; P = 0.001) but had methodologic issues including high drop-out rate, exclusion of patients on oxygen, and a large of proportion of nonsmokers.60

Long-Term Antibiotics

There is no role for long-term antibiotics in the management of COPD.7 Macrolides are an exception but are used for their anti-inflammatory effects rather than their antibiotic effects. They should be reserved for patients with frequent exacerbations on optimal therapy and will be discussed later in the review.61

What nonpharmacologic treatments are recommended for COPD patients?

Smoking cessation, oxygen therapy for severe hypoxemia (resting O2 saturation ≤ 88% or PaO2 ≤ 55 mm Hg), vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus, and appropriate nutrition should be provided in all COPD patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation is indicated for patients in GOLD categories B, C, and D.7 It improves symptoms, quality of life, exercise tolerance, and health care utilization. Beneficial effects last for about 2 years.62,63

What other diagnoses should be considered in patients who continue to be symptomatic on optimal therapy?

Other diseases that share the same risk factors as COPD and can contribute to dyspnea, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, thromboembolic disease, and pulmonary hypertension, should be considered. In addition, all patients with refractory disease should have a careful assessment of their inhaler technique, continued smoking, need for oxygen therapy, and associated deconditioning.

1. Segreti A, Stirpe E, Rogliani P, Cazzola M. Defining phenotypes in COPD: an aid to personalized healthcare. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18:381-388.

2. Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:598-604.

3. Aubier M, Marthan R, Berger P, et al. [COPD and inflammation: statement from a French expert group: inflammation and remodelling mechanisms]. Rev Mal Respir. 2010;27:1254-1266.

4. Wang ZL. Evolving role of systemic inflammation in comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:3467-3478.

5. Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370:741-750.

6. Miniño AM, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59:1-126.

7. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD 2017. www.goldcopd.org. Accessed July 9, 2019.

8. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:648-654.

9. Wadbo M, Löfdahl CG, Larsson K, et al. Effects of formoterol and ipratropium bromide in COPD: a 3-month placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1138-1146.

10. Ram FS, Sestini P. Regular inhaled short acting beta2 agonists for the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2003;58:580-584.

11. Colice GL. Nebulized bronchodilators for outpatient management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1996;100(1A):11S-8S.

12. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a combination of ipratropium and albuterol is more effective than either agent alone. An 85-day multicenter trial. COMBIVENT Inhalation Aerosol Study Group. Chest. 1994;105:1411-1419.

13. Friedman M, Serby CW, Menjoge SS, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a combination of ipratropium plus albuterol compared with ipratropium alone and albuterol alone in COPD. Chest. 1999;115:635-641.

14. Cook D, Guyatt G, Wong E, et al. Regular versus as-needed short-acting inhaled beta-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:85-90.

15. Wilchesky M, Ernst P, Brophy JM, et al. Bronchodilator use and the risk of arrhythmia in COPD: part 2: reassessment in the larger Quebec cohort. Chest. 2012;142:305-311.

16. Scott VL, Frazee LA. Retrospective comparison of nebulized levalbuterol and albuterol for adverse events in patients with acute airflow obstruction. Am J Ther. 2003;10:341-347.

17. Wong CS, Pavord ID, Williams J, et al. Bronchodilator, cardiovascular, and hypokalaemic effects of fenoterol, salbutamol, and terbutaline in asthma. Lancet. 1990;336:1396-1399.

18. Cole JM, Sheehan AH, Jordan JK. Concomitant use of ipratropium and tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1717-1721.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

20. Pearlman DS, Chervinsky P, LaForce C, et al. A comparison of salmeterol with albuterol in the treatment of mild-to-moderate asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1420-1425.

21. Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(6 Pt 1):1640-1645.

22. Ferguson GT, Feldman G, Pudi KK, et al. improvements in lung function with nebulized revefenacin in the treatment of patients with moderate to very severe COPD: results from two replicate phase III clinical trials. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;6:154-165.

23. Donohue JF, Fogarty C, Lötvall J, et al. Once-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol versus tiotropium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:155-162.

24. Koch A, Pizzichini E, Hamilton A, et al. Lung function efficacy and symptomatic benefit of olodaterol once daily delivered via Respimat versus placebo and formoterol twice daily in patients with GOLD 2-4 COPD: results from two replicate 48-week studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:697-714.