User login

Psychosis as a common thread across psychiatric disorders

Ask a psychiatrist to name a psychotic disorder, and the answer will most likely be “schizophrenia.” But if you closely examine the symptom structure of DSM-5 psychiatric disorders, you will note the presence of psychosis in almost all of them.

Fixed false beliefs and impaired reality testing are core features of psychosis. Those are certainly prominent in severe psychoses such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder. But psychosis is actually a continuum of varying severity across most psychiatric disorders, although they carry different diagnostic labels. Irrational false beliefs and impaired functioning due to poor reality testing are embedded among many DSM-5 disorders. Hallucinations are less common; they are perceptual aberrations, not thought abnormalities, although they can trigger delusional explanations as to their causation.

Consider the following:

- Bipolar disorder. A large proportion of patients with bipolar disorder manifest delusions, usually grandiose, but often paranoid or referential.

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). Although regarded as a “pure mood disorder,” the core symptoms of MDD—self-deprecation and sense of worthlessness—as well as the poor reality testing of suicidal thoughts (that death is a better option than living) are psychotic false beliefs.

- Anxiety and panic disorder. The central symptom in anxiety and panic attacks is a belief in impending doom and/or death. The fear in anxiety disorders is actually based on a false belief (eg, if I get on the plane, it will crash, and I will die). Thus, technically an irrational/psychotic thought process underpins the terror and fear of anxiety disorders.

- Borderline personality disorder. Frank psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid beliefs, are known to be a component of borderline personality disorder symptoms. Although these symptoms tend to be brief and episodic, they can have a deleterious effect on the person’s coping and relationships.

- Other personality disorders. While many individuals with narcissistic personality disorder are functional, their exaggerated sense of self-importance, entitlement, and self-aggrandizement certainly qualifies as a fixed false belief. Patients with other personality disorders, such as schizotypal and paranoid, are known to harbor false beliefs or magical thinking.

- Body dysmorphic disorder. False beliefs about one’s appearance (such as blemishes or asymmetry) are at the center of this disorder, and it meets the litmus test of a psychosis.

- Anorexia nervosa. This disorder is well known to be characterized by a fixed false belief that one is “fat,” even when the patient’s body borders on being cachectic in appearance according to objective observers.

- Autism. This spectrum of diseases includes false beliefs that drive the ritualistic or odd behaviors.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although obsessions are usually ego-dystonic, in severe cases, they become ego-syntonic, similar to delusions. On the other hand, compulsions are often driven by a false belief, such as believing that one’s hands are dirty and must be washed incessantly, or that the locks on the door must be rechecked repeatedly because an intruder may break into the house and harm the inhabitants.

- Neurodegenerative syndromes. Neurodegenerative syndromes are neuropsychiatric disorders that very frequently include psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid delusions, delusions of marital infidelity, Capgras syndrome, or folie à deux. These disorders include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontal temporal dementia, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Huntington’s chorea, temporal lobe epilepsy, stroke, xenomelia, reduplicative phenomena, etc. This reflects the common emergence of faulty thinking with disintegration of neural tissue, both gray and white matter.

Continue to: So it should not be...

So it should not be surprising that antipsychotic medications, especially second-generation agents, have been shown to be helpful as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in practically all the above psychiatric disorders, whether on-label or off-label.

Finally, it should also be noted that a case has been made for the existence of one dimension in all mental disorders manifesting in multiple psychopathologies.1 It is possible that a continuum of delusional thinking is a common thread across many psychiatric disorders due to this putative shared dimension. The milder form of this dimension may also explain the presence of pre-psychotic thinking in a significant proportion of the general population who do not seek psychiatric help.2 Just think of how many people you befriend, socialize with, and regard as perfectly “normal” endorse wild superstitions and astrological predictions, or believe in various conspiracy theories that have no basis in reality.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Caspi A, Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(9):831-844.

2. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179-195.

Ask a psychiatrist to name a psychotic disorder, and the answer will most likely be “schizophrenia.” But if you closely examine the symptom structure of DSM-5 psychiatric disorders, you will note the presence of psychosis in almost all of them.

Fixed false beliefs and impaired reality testing are core features of psychosis. Those are certainly prominent in severe psychoses such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder. But psychosis is actually a continuum of varying severity across most psychiatric disorders, although they carry different diagnostic labels. Irrational false beliefs and impaired functioning due to poor reality testing are embedded among many DSM-5 disorders. Hallucinations are less common; they are perceptual aberrations, not thought abnormalities, although they can trigger delusional explanations as to their causation.

Consider the following:

- Bipolar disorder. A large proportion of patients with bipolar disorder manifest delusions, usually grandiose, but often paranoid or referential.

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). Although regarded as a “pure mood disorder,” the core symptoms of MDD—self-deprecation and sense of worthlessness—as well as the poor reality testing of suicidal thoughts (that death is a better option than living) are psychotic false beliefs.

- Anxiety and panic disorder. The central symptom in anxiety and panic attacks is a belief in impending doom and/or death. The fear in anxiety disorders is actually based on a false belief (eg, if I get on the plane, it will crash, and I will die). Thus, technically an irrational/psychotic thought process underpins the terror and fear of anxiety disorders.

- Borderline personality disorder. Frank psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid beliefs, are known to be a component of borderline personality disorder symptoms. Although these symptoms tend to be brief and episodic, they can have a deleterious effect on the person’s coping and relationships.

- Other personality disorders. While many individuals with narcissistic personality disorder are functional, their exaggerated sense of self-importance, entitlement, and self-aggrandizement certainly qualifies as a fixed false belief. Patients with other personality disorders, such as schizotypal and paranoid, are known to harbor false beliefs or magical thinking.

- Body dysmorphic disorder. False beliefs about one’s appearance (such as blemishes or asymmetry) are at the center of this disorder, and it meets the litmus test of a psychosis.

- Anorexia nervosa. This disorder is well known to be characterized by a fixed false belief that one is “fat,” even when the patient’s body borders on being cachectic in appearance according to objective observers.

- Autism. This spectrum of diseases includes false beliefs that drive the ritualistic or odd behaviors.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although obsessions are usually ego-dystonic, in severe cases, they become ego-syntonic, similar to delusions. On the other hand, compulsions are often driven by a false belief, such as believing that one’s hands are dirty and must be washed incessantly, or that the locks on the door must be rechecked repeatedly because an intruder may break into the house and harm the inhabitants.

- Neurodegenerative syndromes. Neurodegenerative syndromes are neuropsychiatric disorders that very frequently include psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid delusions, delusions of marital infidelity, Capgras syndrome, or folie à deux. These disorders include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontal temporal dementia, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Huntington’s chorea, temporal lobe epilepsy, stroke, xenomelia, reduplicative phenomena, etc. This reflects the common emergence of faulty thinking with disintegration of neural tissue, both gray and white matter.

Continue to: So it should not be...

So it should not be surprising that antipsychotic medications, especially second-generation agents, have been shown to be helpful as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in practically all the above psychiatric disorders, whether on-label or off-label.

Finally, it should also be noted that a case has been made for the existence of one dimension in all mental disorders manifesting in multiple psychopathologies.1 It is possible that a continuum of delusional thinking is a common thread across many psychiatric disorders due to this putative shared dimension. The milder form of this dimension may also explain the presence of pre-psychotic thinking in a significant proportion of the general population who do not seek psychiatric help.2 Just think of how many people you befriend, socialize with, and regard as perfectly “normal” endorse wild superstitions and astrological predictions, or believe in various conspiracy theories that have no basis in reality.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

Ask a psychiatrist to name a psychotic disorder, and the answer will most likely be “schizophrenia.” But if you closely examine the symptom structure of DSM-5 psychiatric disorders, you will note the presence of psychosis in almost all of them.

Fixed false beliefs and impaired reality testing are core features of psychosis. Those are certainly prominent in severe psychoses such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder. But psychosis is actually a continuum of varying severity across most psychiatric disorders, although they carry different diagnostic labels. Irrational false beliefs and impaired functioning due to poor reality testing are embedded among many DSM-5 disorders. Hallucinations are less common; they are perceptual aberrations, not thought abnormalities, although they can trigger delusional explanations as to their causation.

Consider the following:

- Bipolar disorder. A large proportion of patients with bipolar disorder manifest delusions, usually grandiose, but often paranoid or referential.

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). Although regarded as a “pure mood disorder,” the core symptoms of MDD—self-deprecation and sense of worthlessness—as well as the poor reality testing of suicidal thoughts (that death is a better option than living) are psychotic false beliefs.

- Anxiety and panic disorder. The central symptom in anxiety and panic attacks is a belief in impending doom and/or death. The fear in anxiety disorders is actually based on a false belief (eg, if I get on the plane, it will crash, and I will die). Thus, technically an irrational/psychotic thought process underpins the terror and fear of anxiety disorders.

- Borderline personality disorder. Frank psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid beliefs, are known to be a component of borderline personality disorder symptoms. Although these symptoms tend to be brief and episodic, they can have a deleterious effect on the person’s coping and relationships.

- Other personality disorders. While many individuals with narcissistic personality disorder are functional, their exaggerated sense of self-importance, entitlement, and self-aggrandizement certainly qualifies as a fixed false belief. Patients with other personality disorders, such as schizotypal and paranoid, are known to harbor false beliefs or magical thinking.

- Body dysmorphic disorder. False beliefs about one’s appearance (such as blemishes or asymmetry) are at the center of this disorder, and it meets the litmus test of a psychosis.

- Anorexia nervosa. This disorder is well known to be characterized by a fixed false belief that one is “fat,” even when the patient’s body borders on being cachectic in appearance according to objective observers.

- Autism. This spectrum of diseases includes false beliefs that drive the ritualistic or odd behaviors.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although obsessions are usually ego-dystonic, in severe cases, they become ego-syntonic, similar to delusions. On the other hand, compulsions are often driven by a false belief, such as believing that one’s hands are dirty and must be washed incessantly, or that the locks on the door must be rechecked repeatedly because an intruder may break into the house and harm the inhabitants.

- Neurodegenerative syndromes. Neurodegenerative syndromes are neuropsychiatric disorders that very frequently include psychotic symptoms, such as paranoid delusions, delusions of marital infidelity, Capgras syndrome, or folie à deux. These disorders include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontal temporal dementia, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Huntington’s chorea, temporal lobe epilepsy, stroke, xenomelia, reduplicative phenomena, etc. This reflects the common emergence of faulty thinking with disintegration of neural tissue, both gray and white matter.

Continue to: So it should not be...

So it should not be surprising that antipsychotic medications, especially second-generation agents, have been shown to be helpful as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in practically all the above psychiatric disorders, whether on-label or off-label.

Finally, it should also be noted that a case has been made for the existence of one dimension in all mental disorders manifesting in multiple psychopathologies.1 It is possible that a continuum of delusional thinking is a common thread across many psychiatric disorders due to this putative shared dimension. The milder form of this dimension may also explain the presence of pre-psychotic thinking in a significant proportion of the general population who do not seek psychiatric help.2 Just think of how many people you befriend, socialize with, and regard as perfectly “normal” endorse wild superstitions and astrological predictions, or believe in various conspiracy theories that have no basis in reality.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Caspi A, Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(9):831-844.

2. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179-195.

1. Caspi A, Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(9):831-844.

2. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179-195.

Career Choices: Academic psychiatry

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Chief Resident at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York, talked with Donald W. Black, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa. Dr. Black is also Editor-in-Chief of

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the academic track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Black: I had always been interested in the idea of working at a medical school, and enjoyed writing and speaking. I was exposed to clinical research as a resident, and that confirmed my interest in academia, because I could envision combining all my interests, along with patient care. I always thought that patients were a major source of ideas for research and writing.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in academia?

Dr. Black: The pros include being able to influence future physicians through my teaching and writing; being able to pursue important research; and not being isolated from peers. Other advantages are being largely protected from utilization review; having more free time than peers in the private sector, who have difficulty finding coverage; and having defined benefits and a steady salary. I also share call with many peers.

When it comes to the cons, salaries are lower than in the private sector. The cons also include not being my own boss, and sometimes having to bend to the whims of an institution or supervisor.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: Are you required to conduct research?

Dr. Black: Yes. This is one of the best aspects of my job: being able to make clinical discoveries that I can disseminate through writing and speaking. Over time, this has become increasingly challenging due to the difficulty of obtaining research funding from foundations or the federal government. This has become highly problematic, particularly for clinical researchers, because the National Institutes of Health has clearly been favoring neuroscience.

Dr. Ahmed: What is your typical day like?

Dr. Black: Because of the many hats I wear (or have worn), each day is different from the other. I combine patient care with research, writing, speaking, teaching, and administration. As a tenure-track faculty member, I am expected to write grants, conduct research, and publish. My clinical-track peers primarily provide patient care and teach students and residents.

Dr. Ahmed: What is unique about working in a training institute vs private practice?

Continue to: Dr. Black...

Dr. Black: As an academic psychiatrist, I feel I have the best of both worlds: patient care combined with opportunities my private practice colleagues do not have. Because I have published widely, and have developed a reputation, I am frequently invited to speak at meetings throughout the United States, and sometimes internationally. Travel is a perk of academia, and as someone who loves travel, that is important.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see psychiatry going?

Dr. Black: Psychiatry will always be an important specialty because no one else truly cares about patients with psychiatric illnesses. Mental illness will not go away, and society needs highly trained individuals to provide care. There are many “me too” clinicians who now share in caring for patients with psychiatric illnesses, but psychiatrists will always have the most training, and are in a position to provide supervision to others and to direct mental health care teams.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for residents contemplating a career in academic psychiatry?

Dr. Black: Because most medical schools now have both tenure and clinical tracks, no one needs to feel left out. Those who are interested in scholarly activities will gravitate to the tenure tract, and all that requires in terms of grants and papers, while those who are primarily interested in patient care and teaching will choose the clinical track.

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Chief Resident at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York, talked with Donald W. Black, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa. Dr. Black is also Editor-in-Chief of

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the academic track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Black: I had always been interested in the idea of working at a medical school, and enjoyed writing and speaking. I was exposed to clinical research as a resident, and that confirmed my interest in academia, because I could envision combining all my interests, along with patient care. I always thought that patients were a major source of ideas for research and writing.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in academia?

Dr. Black: The pros include being able to influence future physicians through my teaching and writing; being able to pursue important research; and not being isolated from peers. Other advantages are being largely protected from utilization review; having more free time than peers in the private sector, who have difficulty finding coverage; and having defined benefits and a steady salary. I also share call with many peers.

When it comes to the cons, salaries are lower than in the private sector. The cons also include not being my own boss, and sometimes having to bend to the whims of an institution or supervisor.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: Are you required to conduct research?

Dr. Black: Yes. This is one of the best aspects of my job: being able to make clinical discoveries that I can disseminate through writing and speaking. Over time, this has become increasingly challenging due to the difficulty of obtaining research funding from foundations or the federal government. This has become highly problematic, particularly for clinical researchers, because the National Institutes of Health has clearly been favoring neuroscience.

Dr. Ahmed: What is your typical day like?

Dr. Black: Because of the many hats I wear (or have worn), each day is different from the other. I combine patient care with research, writing, speaking, teaching, and administration. As a tenure-track faculty member, I am expected to write grants, conduct research, and publish. My clinical-track peers primarily provide patient care and teach students and residents.

Dr. Ahmed: What is unique about working in a training institute vs private practice?

Continue to: Dr. Black...

Dr. Black: As an academic psychiatrist, I feel I have the best of both worlds: patient care combined with opportunities my private practice colleagues do not have. Because I have published widely, and have developed a reputation, I am frequently invited to speak at meetings throughout the United States, and sometimes internationally. Travel is a perk of academia, and as someone who loves travel, that is important.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see psychiatry going?

Dr. Black: Psychiatry will always be an important specialty because no one else truly cares about patients with psychiatric illnesses. Mental illness will not go away, and society needs highly trained individuals to provide care. There are many “me too” clinicians who now share in caring for patients with psychiatric illnesses, but psychiatrists will always have the most training, and are in a position to provide supervision to others and to direct mental health care teams.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for residents contemplating a career in academic psychiatry?

Dr. Black: Because most medical schools now have both tenure and clinical tracks, no one needs to feel left out. Those who are interested in scholarly activities will gravitate to the tenure tract, and all that requires in terms of grants and papers, while those who are primarily interested in patient care and teaching will choose the clinical track.

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Chief Resident at Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, New York, talked with Donald W. Black, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa. Dr. Black is also Editor-in-Chief of

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the academic track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Black: I had always been interested in the idea of working at a medical school, and enjoyed writing and speaking. I was exposed to clinical research as a resident, and that confirmed my interest in academia, because I could envision combining all my interests, along with patient care. I always thought that patients were a major source of ideas for research and writing.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in academia?

Dr. Black: The pros include being able to influence future physicians through my teaching and writing; being able to pursue important research; and not being isolated from peers. Other advantages are being largely protected from utilization review; having more free time than peers in the private sector, who have difficulty finding coverage; and having defined benefits and a steady salary. I also share call with many peers.

When it comes to the cons, salaries are lower than in the private sector. The cons also include not being my own boss, and sometimes having to bend to the whims of an institution or supervisor.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: Are you required to conduct research?

Dr. Black: Yes. This is one of the best aspects of my job: being able to make clinical discoveries that I can disseminate through writing and speaking. Over time, this has become increasingly challenging due to the difficulty of obtaining research funding from foundations or the federal government. This has become highly problematic, particularly for clinical researchers, because the National Institutes of Health has clearly been favoring neuroscience.

Dr. Ahmed: What is your typical day like?

Dr. Black: Because of the many hats I wear (or have worn), each day is different from the other. I combine patient care with research, writing, speaking, teaching, and administration. As a tenure-track faculty member, I am expected to write grants, conduct research, and publish. My clinical-track peers primarily provide patient care and teach students and residents.

Dr. Ahmed: What is unique about working in a training institute vs private practice?

Continue to: Dr. Black...

Dr. Black: As an academic psychiatrist, I feel I have the best of both worlds: patient care combined with opportunities my private practice colleagues do not have. Because I have published widely, and have developed a reputation, I am frequently invited to speak at meetings throughout the United States, and sometimes internationally. Travel is a perk of academia, and as someone who loves travel, that is important.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see psychiatry going?

Dr. Black: Psychiatry will always be an important specialty because no one else truly cares about patients with psychiatric illnesses. Mental illness will not go away, and society needs highly trained individuals to provide care. There are many “me too” clinicians who now share in caring for patients with psychiatric illnesses, but psychiatrists will always have the most training, and are in a position to provide supervision to others and to direct mental health care teams.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for residents contemplating a career in academic psychiatry?

Dr. Black: Because most medical schools now have both tenure and clinical tracks, no one needs to feel left out. Those who are interested in scholarly activities will gravitate to the tenure tract, and all that requires in terms of grants and papers, while those who are primarily interested in patient care and teaching will choose the clinical track.

Factors that change our brains; The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Factors that change our brains

I greatly enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial, “Your patient’s brain is different at every visit” (From the Editor,

In reading this editorial, it is clear that a myriad of factors we consider and address with our patients during each visit underly intricate neurobiologic mechanisms and processes that ever deepen our understanding of the brain. In discussing the changes taking place in our patients, I can’t help but wonder what changes are also occurring in our brains (as Dr. Nasrallah noted). What would be the resulting impact of these changes in our next patient interaction and/or subsequent interaction(s) with the same patient? Looking through the editorial’s bullet points, many (if not all) of the factors contributing to brain changes apply equally and naturally to clinicians as well as patients. In this light, the editorial serves not only as a broad guideline for patient psychoeducation but also as a reminder of wellness and well-being for clinicians.

As a “fresh-out-of-training” psychiatrist, I can definitely work on several of the factors, such as diet and exercise. Trainees and residents can be more susceptible to overlook and befall some of these factors and changes, and may already be basing the clinical advice they give to their patients on these same factors and changes. As a child psychiatrist, I value the importance of modeling healthy behaviors for my patients, and their families and with coworkers or colleagues. In accordance with the impact these factors have on our brains, it’s important to emphasize what we can do to further strengthen rapport and therapeutic value through modeling. I strive to model the desired behaviors, attitudes, and dynamics that are the external, observable manifestation or symptomology of what takes place in my brain. To do so, I understand I need to be mindful in proactively managing the contributing factors, such as those listed in Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial. I imagine patients and their families would easily notice if we are in suboptimal physical and/or mental health that results in us not being prompt, fully engaged, or receptive. I believe that attending to these facets during training falls under the umbrella of professionalism. Being a professional in our field often entails practicing what we preach. So, I’m grateful that what we preach is informed by our field’s exciting research, continued advancements, and expertise that benefits our patients and us professionally and personally.

Philip Yen-Tsun Liu, MD

Child and adolescent psychiatrist

innovaTel Telepsychiatry

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I would like to thank Dr. Liu for his thoughtful response to my editorial. He seems to be very cognizant of the fact that experiential neuroplasticity and brain tissue remodeling occurs in both the patient and physician. I admire his focus on psychoeducation, wellness, and professionalism. He is right that we as psychiatrists (and nurse practitioners) must be role models for our patients in multiple ways, because it may help enhance clinical outcomes and have a positive impact on their brains.

I would also like to point Dr. Liu to the editorial “The most powerful placebo is not a pill” (From the Editor,

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Sydney W. Souers Endowed Chair

Professor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

The APA’s stance on neuroimaging

Can anyone in the modern world argue that the brain is irrelevant to psychiatry? Yet surprisingly, in September 2018, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially declared that neuroimaging of the brain has no clinical value in psychiatry.1

Unfortunately, the APA focused almost exclusively on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neglected an extensive library of studies of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). The APA’s position on neuroimaging is as follows1,2:

- A neuroimaging finding must have a sensitivity and specificity (S/sp) of no less than 80%.

- The psychiatric imaging literature does not support using neuroimaging in psychiatric diagnostics or treatment.

- Neuroimaging has not had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

The APA set unrealistic standards for biomarkers in a field that lacks pathologic markers of specific disease entities.3 Moreover, numerous widely used tests fall below the APA’s unrealistic S/sp cutoff, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,4 Zung Depression Scale,5 the clock drawing test,6 and even the chest X-ray.3 Curiously, numerous replicated SPECT and PET studies were not included in the APA’s analysis.1-3 For example, in a study of 196 veterans, posttraumatic stress disorder was distinguished from traumatic brain injury with an S/sp of 0.92/0.85.7,8 Also, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has an S/sp of 0.84/0.74 in differentiating patients with Alzheimer’s disease from controls, while perfusion SPECT, using multi-detector cameras, has an S/sp of 0.93/0.84.3,9 Moreover, both FDG-PET and SPECT can differentiate other forms of dementia from Alzheimer’s disease, yielding an additional benefit compared to amyloid imaging alone.2,9 As President of the International Society of Applied Neuroimaging, I suggest neuroimaging should not be feared. Neuroimaging does not replace the diagnostician; rather, it aids him/her in a complex case.

Theodore A. Henderson, MD, PhD

President

Neuro-Luminance Brain Health Centers, Inc.

Denver, Colorado

Director

The Synaptic Space

Vice President

The Neuro-Laser Foundation

President

International Society of Applied Neuroimaging

Centennial, Colorado

Disclosure

The author has no ownership in, and receives no remuneration from, any neuroimaging company.

References

1. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018:175:

2. First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, et al. Data supplement for Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(suppl).

3. Henderson TA. Brain SPECT imaging in neuropsychiatric diagnosis and monitoring. EPatient. http://nmpangea.com/2018/10/09/738/. Published 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

4. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, et al. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163-2177.

5. Biggs JT, Wylie LT, Ziegler VE. Validity of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:381-385.

6. Seigerschmidt E, Mösch E, Siemen M, et al. The clock drawing test and questionable dementia: reliability and validity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(11):1048-1054.

7. Raji CA, Willeumier K, Taylor D, et al. Functional neuroimaging with default mode network regions distinguishes PTSD from TBI in a military veteran population. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(3):527-534.

8. Amen DG, Raji CA, Willeumier K, et al. Functional neuroimaging distinguishes posttraumatic stress disorder from traumatic brain injury in focused and large community datasets. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129659.

9. Henderson TA. The diagnosis and evaluation of dementia and mild cognitive impairment with emphasis on SPECT perfusion neuroimaging. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(4):176-206.

Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

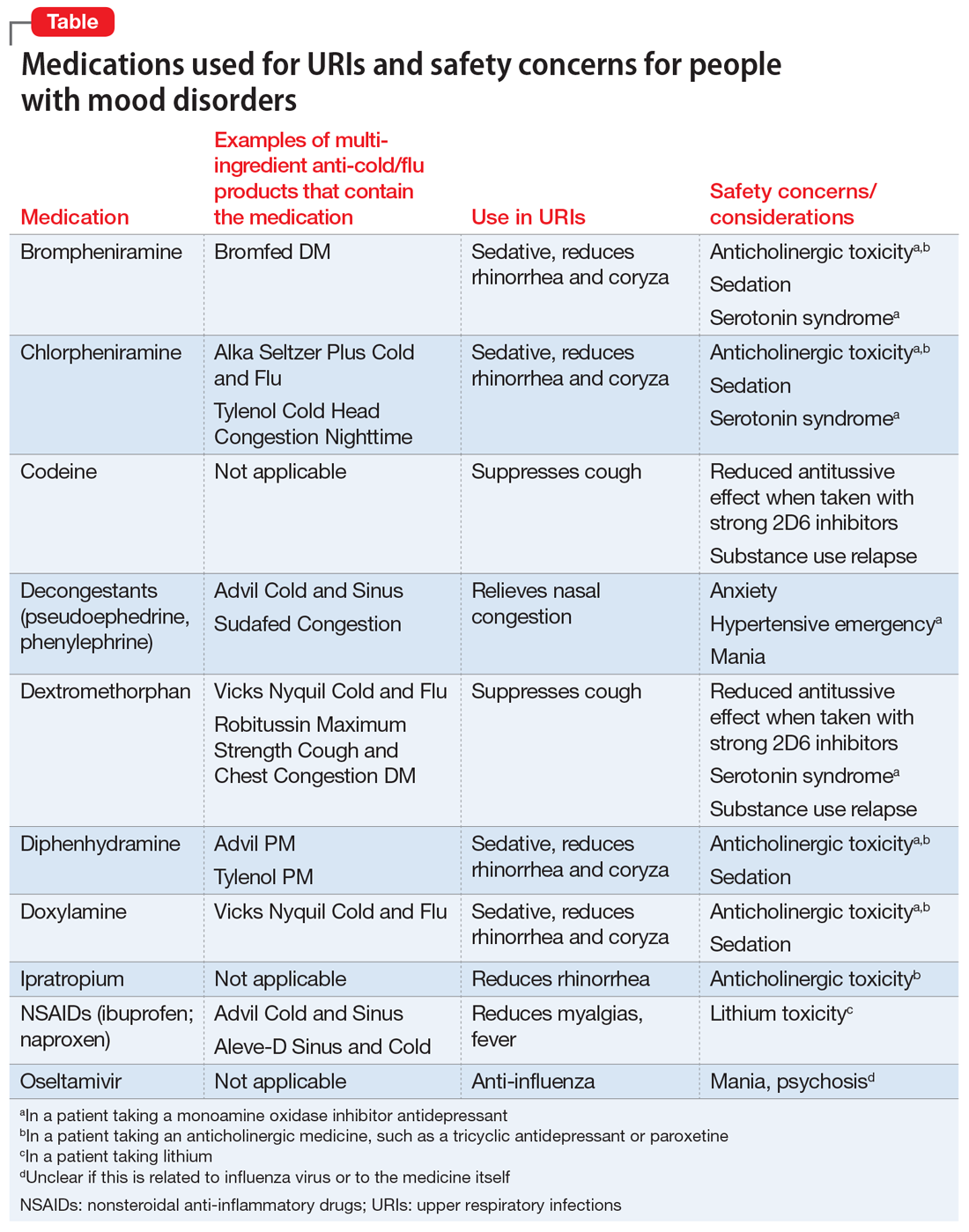

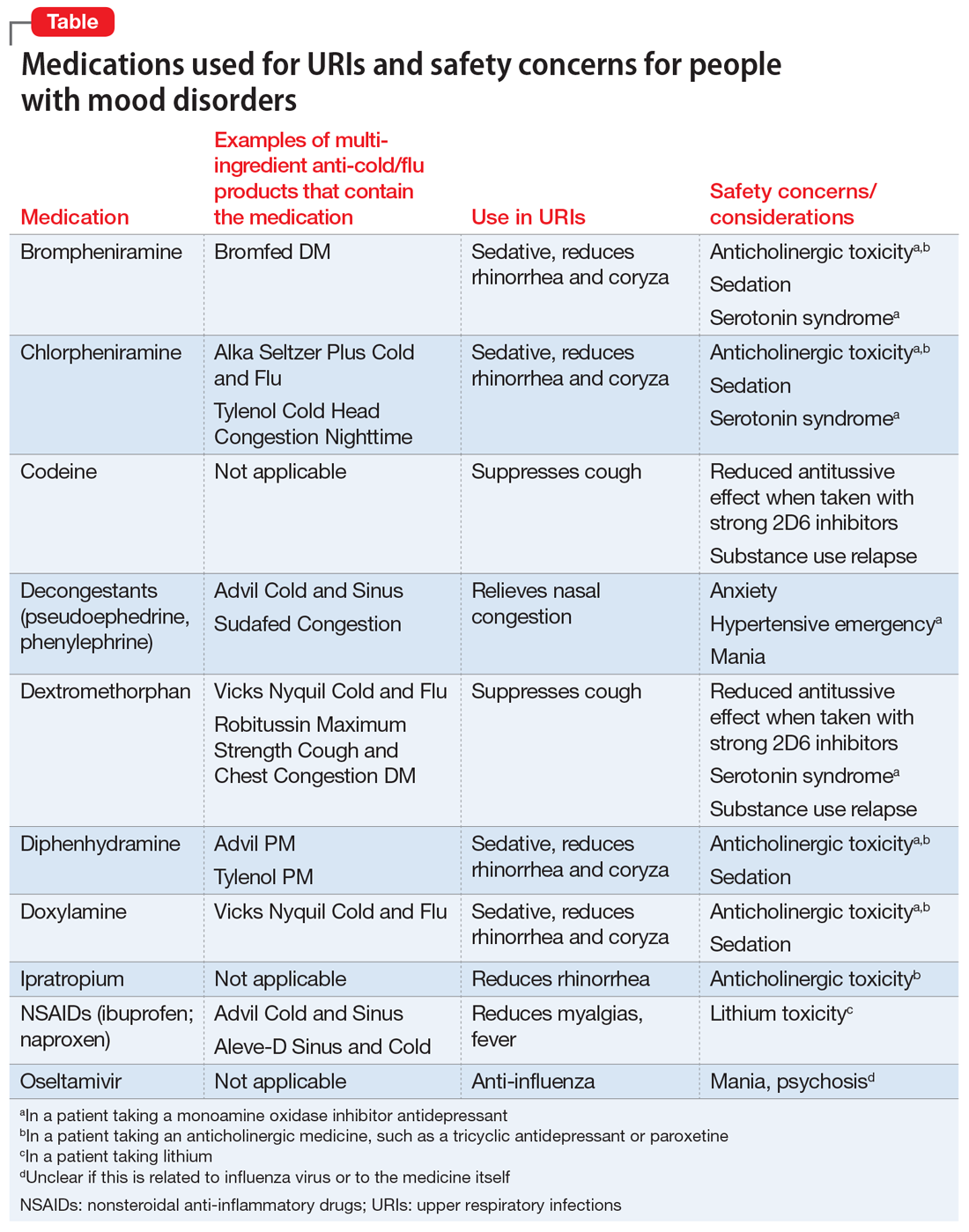

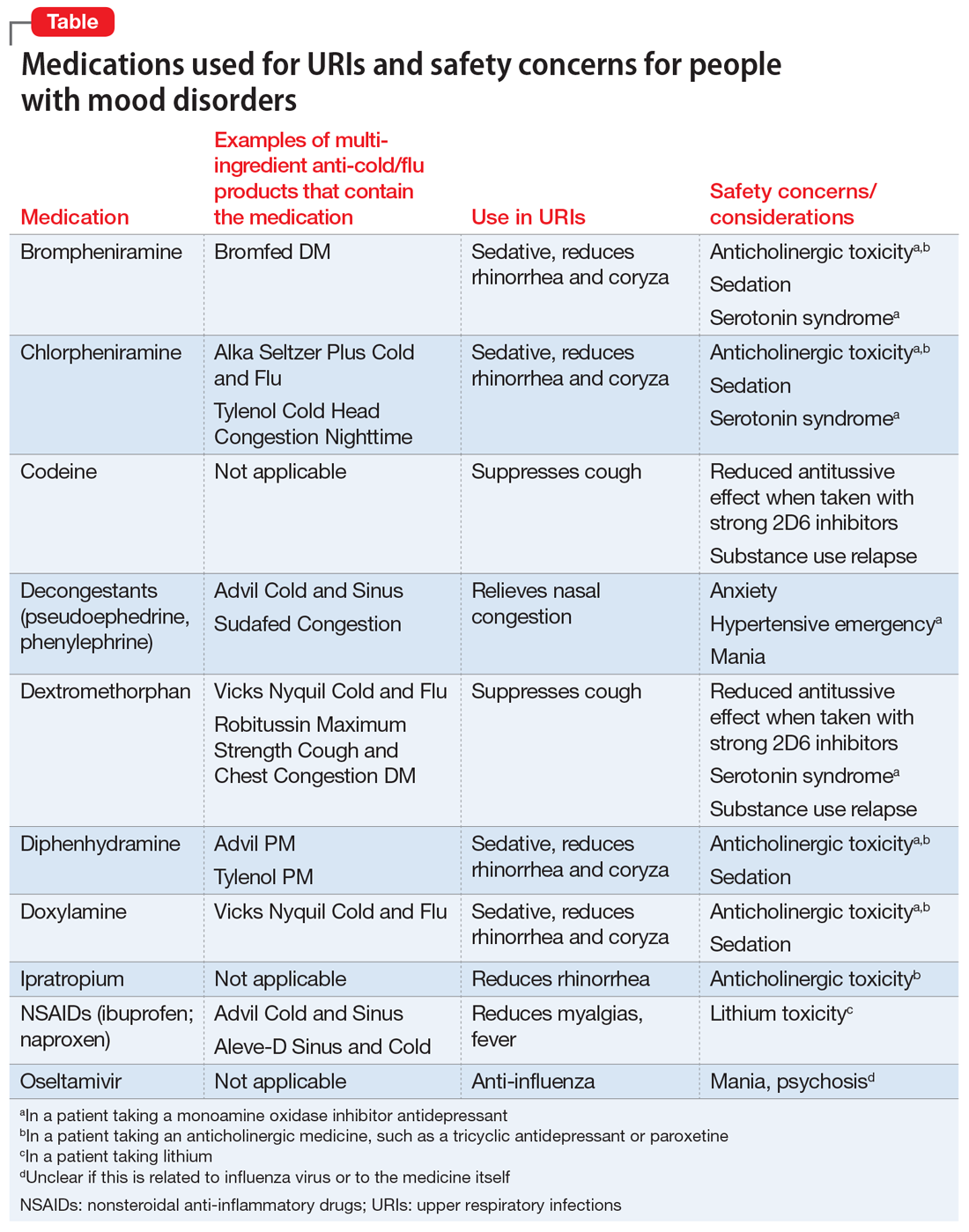

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26