User login

Breaking down blockchain: How this novel technology will unfetter health care

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

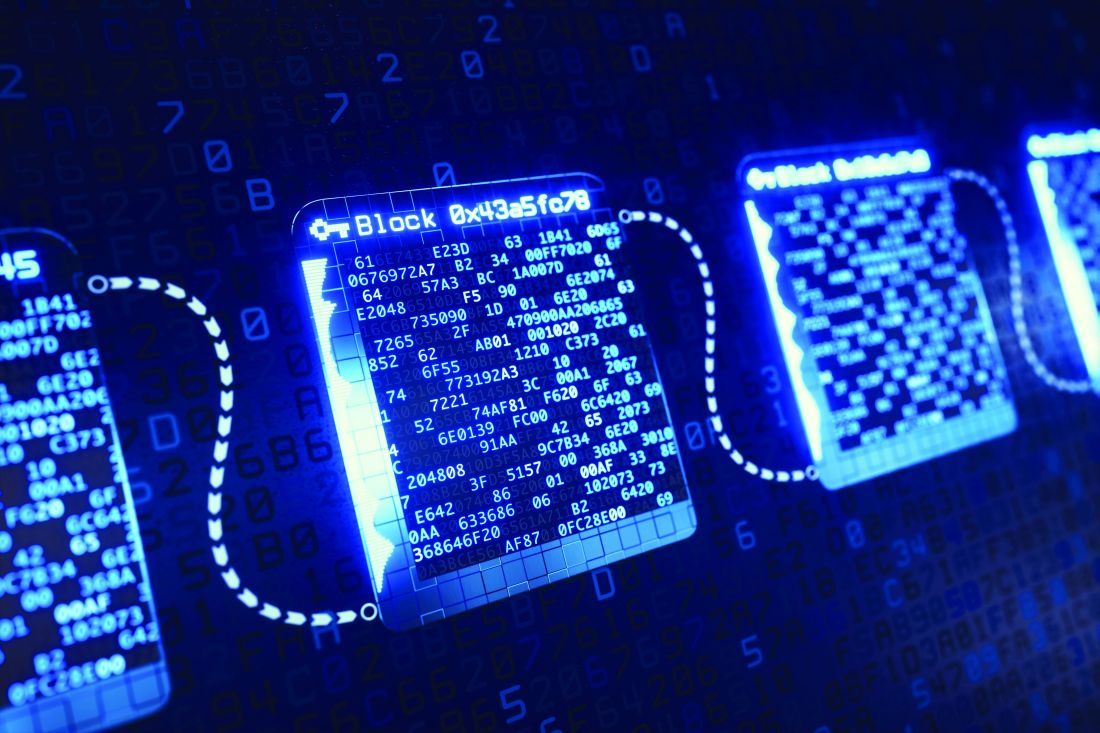

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

Keeping Your Brain in Shape

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

Every year, thousands of us vow to “get in shape” by eating right and exercising. (Whether we keep that resolution is another story.) But while we view physical exercise as a way to lose or maintain weight, reduce stress, or even hone athletic skills, we seldom think about exercising one of the most important muscles in our body: the brain.

“What?” you say. “The brain is not like other muscles.” No, it’s not … and yet, it isn’t as different as we used to think. Historically (maybe histologically?), it was believed that if nerve cells in the adult brain were damaged or had died, they, unlike other cells in t

But since the late 1990s, scientists have been debunking the negative myths about our brains as we age. They are not as static and unable to change as we have been led to fear! In fact, in 1998, American and Swedish scientists demonstrated that adult humans can generate new brain cells.1,2 Moreover, the brain does replicate neurons in the hippocampus, the area in our brains that is central to learning and memory. Neurons continue to grow and change beyond the first years of development and well into adulthood.

So learning (and teaching) movements to encourage the rebuilding of our neurons is key to keeping our minds sharp. In his work, Ratey found that “our physical movements can directly influence our ability to learn, think, and remember.”3 He also tells us that exercise enhances circulation to the brain, “priming it for improved function, including mental health as well as cognitive ability.”4

No, you can’t put your brain on a treadmill to get, and help keep, it “in shape.” But you can do something to maintain mental sharpness and delay decline in mental agility. And these exercises don’t require a health club membership or special equipment. They can be done anytime, anywhere … and no one knows you are doing them!

I’m talking about neurobics, a term coined to describe exercises that keep us mentally fit.5 The purpose of these activities is to work our brains in nonroutine or unexpected ways, using all of our senses to experience, or re-experience, a common activity.

Not sure what that means? Here are some examples:

Spend time in a new environment. Go to a different park or a new store. Travel, by the way, seems to slow age-related mental decline.

Continue to: Smell new odors in the morning

Smell new odors in the morning. Have new scents, like a bottle of mint extract, ready to smell first thing in the morning, to “wake up” your brain.

Take a shower with your eyes closed. Other senses become more active when you cannot see, and a shower engages several.

Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand. This may be difficult for some of us—and it definitely requires full attention the first time you try it!

Learn to read braille. This is a tough one, but learning to read with your fingers definitely involves one of your senses in a new context. Or, you could try learning American Sign Language, which also uses your fingers to communicate.

Respond to a situation differently. Catch yourself in a normal, unconscious response to a situation, and choose to respond in an alternate (and preferably better) way.

Continue to: Find a new route to work

Find a new route to work. It doesn’t have to be longer, just different. You may even find a faster way to work once you break your routine.

Act confidently. In a situation you are unsure about, choose to act confidently. You’ll notice that your mind gets very active once you adopt the assumption that you will know what to do.

Distinguish coins using only your sense of touch. This brain exercise can be used to kill time while waiting for an appointment. If you really want a challenge, see if you can distinguish paper currency denominations by touch.

Leave the lights off in the house. Get around your home by memory and feel. This certainly fully engages your attention—but be careful, of course!

If you give neurobics a try, let me know what you think! Or if you have other tips for staying mentally “fit,” please share them. I can be reached at [email protected]. And thank you to my friend Gail, who suggested this topic to me!

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

1. Kempermann G, Gage FH. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Scientific American. 1999;280(5):38-44.

2. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(11):1313-1317.

3. Ratey J. A User’s Guide to the Brain: Perception, Attention, and the Four Theaters of the Brain. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2002.

4. Ratey J. SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2008.

5. Katz LC, Rubin M. Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 1999.

Defeating the opioid epidemic

The U.S. Surgeon General weighs in.

Vice Admiral Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, is the 20th Surgeon General of the United States, a post created in 1871.

Dr. Adams holds degrees in biochemistry and psychology from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County; a master’s degree in public health from the University of California, Berkeley; and a medical degree from the Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is a board-certified anesthesiologist and associate clinical professor of anesthesia at Indiana University.

At the 2018 Executive Advisory Board meeting of the Doctors Company, Richard E. Anderson, MD, FACP, chairman and chief executive officer of the Doctors Company, spoke with Dr. Adams about the opioid epidemic’s enormous impact on communities and health services in the United States.

Dr. Anderson: Dr. Adams, you’ve been busy since taking over as Surgeon General of the United States. What are some of the key challenges that you’re facing in this office?

Dr. Adams: You know, there are many challenges facing our country, but it boils down to a lack of wellness. We know that only 10% of health is due to health care, 20% of health is genetics, and the rest is a combination of behavior and environment.

My motto is “better health through better partnerships,” because I firmly believe that if we break out of our silos and reach across the traditional barriers that have been put up by funding, by reimbursement, and by infrastructure, then we can ultimately achieve wellness in our communities.

You asked what I’ve been focused on as Surgeon General. Well, I’m focused on three main areas right now.

No. 1 is the opioid epidemic. It is a scourge across our country. A person dies every 12½ minutes from an opioid overdose and that’s far too many. Especially when we know that many of those deaths can be prevented.

Another area I’m focused on is demonstrating the link between community health and economic prosperity. We want folks to invest in health because we know that not only will it achieve better health for individuals and communities but it will create a more prosperous nation, also.

And finally, I’m raising awareness about the links between our nation’s health and our safety and security – particularly our national security. Unfortunately, 7 out of 10 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 years old in our country are ineligible for military service. That’s because they can’t pass the physical, they can’t meet the educational requirements, or they have a criminal record.

So, our nation’s poor health is not just a matter of diabetes or heart disease 20 or 30 years down the road. We are literally a less-safe country right now because we’re an unhealthy country.

Dr. Anderson: Regarding the opioid epidemic, what are some of the programs that are available today that you find effective? What would you like to see us do as a nation to respond to the epidemic?

Dr. Adams: Recently, I was at a hospital in Alaska where they have implemented a neonatal abstinence syndrome protocol and program that is being looked at around the country – and others are attempting to replicate it.

We know that if you keep mom and baby together, baby does better, mom does better, hospital stays are shorter, costs go down, and you’re keeping that family unit intact. This prevents future problems for both the baby and the mother. That’s just one small example.

I’m also very happy to see that the prescribing of opioids is going down 20%-25% across the country. And there are even larger decreases in the military and veteran communities. That’s really a testament to doctors and the medical profession finally waking up. And I say this as a physician myself, as an anesthesiologist, as someone who is involved in acute and chronic pain management.

Four out of five people with substance use disorder say they started with a prescription opioid. Many physicians will say, “Those aren’t my patients,” but unfortunately when we look at the PDMP [prescription drug monitoring program] data across the country we do a poor job of predicting who is and who isn’t going to divert. It may not be your patient, but it could be their son or the babysitter who is diverting those overprescribed opioids.

One thing that I really think we need to lean into as health care practitioners is providing medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. We know that the gold standard for treatment and recovery is medication-assisted treatment of some form. But we also know it’s not nearly available enough and that there are barriers on the federal and state levels.

We need you to continue to talk to your congressional representatives and let them know which barriers you perceive because the data waiver comes directly from Congress.

Still, any ER can prescribe up to 3 days of MAT to someone. I’d much rather have our ER doctors putting patients on MAT and then connecting them to treatment, than sending them back out into the arms of a drug dealer after they put them into acute withdrawal with naloxone.

We also have too many pregnant women who want help but can’t find any treatment because no one out there will take care of pregnant moms. We need folks to step up to the plate and get that data waiver in our ob/gyn and primary care sectors.

Ultimately, we need hospitals and health care leaders to create an environment that makes providers feel comfortable providing that service by giving them the training and the support to be able to do it.

We also need to make sure we’re co-prescribing naloxone for those who are at risk for opioid overdose.

Dr. Anderson: Just so we are clear, are you in favor of regular prescribing of naloxone, along with prescriptions for opioids? Is that correct?

Dr. Adams: I issued the first Surgeon General’s advisory from more than 10 years earlier this year to help folks understand that over half of our opioid overdoses occur in a home setting. We all know that an anoxic brain injury occurs in 4-5 minutes. We also know that most ambulances and first responders aren’t going to show up in 4-5 minutes.

If we want to make a dent in this overdose epidemic, we need everyone to consider themselves a first responder. We need to look at it the same as we look at CPR; we need everyone carrying naloxone. That was one of the big pushes from my Surgeon General’s advisory.

How can providers help? Well, they can coprescribe naloxone to folks on high morphine milligram equivalents (MME) who are at risk. If grandma has naloxone at home and her grandson overdoses in the garage, then at least it’s in the same house. Naloxone is not the treatment for the opioid epidemic. But we can’t get someone who is dead into treatment.

I have no illusions that simply making naloxone available is going to turn the tide, but it certainly is an important part of it.

Dr. Anderson: From your unique viewpoint, how much progress do you see in relation to the opioid epidemic? Do you think we’re approaching an inflection point, or do you think there’s a long way to go before this starts to turn around?

Dr. Adams: When I talk about the opioid epidemic, I have two angles. No.1, I want to raise awareness about the opioid epidemic – the severity of it, and how everyone can lean into it in their own way. Whether it’s community citizens, providers, law enforcement, the business community, whomever.

But in addition to raising awareness, I want to instill hope.

I was in Huntington, West Virginia, just a few weeks ago at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. They’ve been able to turn their opioid overdose rates around by providing peer recovery coaches to individuals and making sure naloxone is available throughout the community. You save the life and then you connect them to care.

We know that the folks who are at highest risk for overdose deaths are the ones who just overdosed. They come out of the ER where we’ve watched them for a few hours and then we send them right back out into the arms of the drug dealer to do exactly what we know they will do medically because we’ve thrown them into withdrawal and they try to get their next fix.

If we can partner with law enforcement, then we can turn our opioid overdose rates around.

A story of recovery that I want to share with you is about a guy named Jonathan, who I met when I was in Rhode Island.

Jonathan overdosed, but his roommate had access to naloxone, which he administered. Jonathan was taken to the ER and then connected with a peer recovery coach. He is now in recovery and has actually become a peer recovery coach himself. Saving this one life will now enable us to save many more.

Yet we still prescribe more than 80% of the world’s opioids to less than 5% of the world’s population. So, we still have an overprescribing epidemic, but we’ve surpassed the inflection point there. Prescribing is coming down.

But another part of this epidemic was that we squeezed the balloon in one place and, as prescribing opioids went down, lots of people switched over to heroin. That’s when we really first started to see overdose rates go up.

Well, it’s important for folks to know that, through law enforcement, through partnerships with the public health community, through an increase in syringe service programs, and through other touch points, heroin use is now going down in most places.

Unfortunately, now we’re seeing the third wave of the epidemic, and that’s fentanyl and carfentanil.

The U.S. Surgeon General weighs in.

The U.S. Surgeon General weighs in.

Vice Admiral Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, is the 20th Surgeon General of the United States, a post created in 1871.

Dr. Adams holds degrees in biochemistry and psychology from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County; a master’s degree in public health from the University of California, Berkeley; and a medical degree from the Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is a board-certified anesthesiologist and associate clinical professor of anesthesia at Indiana University.

At the 2018 Executive Advisory Board meeting of the Doctors Company, Richard E. Anderson, MD, FACP, chairman and chief executive officer of the Doctors Company, spoke with Dr. Adams about the opioid epidemic’s enormous impact on communities and health services in the United States.

Dr. Anderson: Dr. Adams, you’ve been busy since taking over as Surgeon General of the United States. What are some of the key challenges that you’re facing in this office?

Dr. Adams: You know, there are many challenges facing our country, but it boils down to a lack of wellness. We know that only 10% of health is due to health care, 20% of health is genetics, and the rest is a combination of behavior and environment.

My motto is “better health through better partnerships,” because I firmly believe that if we break out of our silos and reach across the traditional barriers that have been put up by funding, by reimbursement, and by infrastructure, then we can ultimately achieve wellness in our communities.

You asked what I’ve been focused on as Surgeon General. Well, I’m focused on three main areas right now.

No. 1 is the opioid epidemic. It is a scourge across our country. A person dies every 12½ minutes from an opioid overdose and that’s far too many. Especially when we know that many of those deaths can be prevented.

Another area I’m focused on is demonstrating the link between community health and economic prosperity. We want folks to invest in health because we know that not only will it achieve better health for individuals and communities but it will create a more prosperous nation, also.

And finally, I’m raising awareness about the links between our nation’s health and our safety and security – particularly our national security. Unfortunately, 7 out of 10 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 years old in our country are ineligible for military service. That’s because they can’t pass the physical, they can’t meet the educational requirements, or they have a criminal record.

So, our nation’s poor health is not just a matter of diabetes or heart disease 20 or 30 years down the road. We are literally a less-safe country right now because we’re an unhealthy country.

Dr. Anderson: Regarding the opioid epidemic, what are some of the programs that are available today that you find effective? What would you like to see us do as a nation to respond to the epidemic?

Dr. Adams: Recently, I was at a hospital in Alaska where they have implemented a neonatal abstinence syndrome protocol and program that is being looked at around the country – and others are attempting to replicate it.

We know that if you keep mom and baby together, baby does better, mom does better, hospital stays are shorter, costs go down, and you’re keeping that family unit intact. This prevents future problems for both the baby and the mother. That’s just one small example.

I’m also very happy to see that the prescribing of opioids is going down 20%-25% across the country. And there are even larger decreases in the military and veteran communities. That’s really a testament to doctors and the medical profession finally waking up. And I say this as a physician myself, as an anesthesiologist, as someone who is involved in acute and chronic pain management.

Four out of five people with substance use disorder say they started with a prescription opioid. Many physicians will say, “Those aren’t my patients,” but unfortunately when we look at the PDMP [prescription drug monitoring program] data across the country we do a poor job of predicting who is and who isn’t going to divert. It may not be your patient, but it could be their son or the babysitter who is diverting those overprescribed opioids.

One thing that I really think we need to lean into as health care practitioners is providing medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. We know that the gold standard for treatment and recovery is medication-assisted treatment of some form. But we also know it’s not nearly available enough and that there are barriers on the federal and state levels.

We need you to continue to talk to your congressional representatives and let them know which barriers you perceive because the data waiver comes directly from Congress.

Still, any ER can prescribe up to 3 days of MAT to someone. I’d much rather have our ER doctors putting patients on MAT and then connecting them to treatment, than sending them back out into the arms of a drug dealer after they put them into acute withdrawal with naloxone.

We also have too many pregnant women who want help but can’t find any treatment because no one out there will take care of pregnant moms. We need folks to step up to the plate and get that data waiver in our ob/gyn and primary care sectors.

Ultimately, we need hospitals and health care leaders to create an environment that makes providers feel comfortable providing that service by giving them the training and the support to be able to do it.

We also need to make sure we’re co-prescribing naloxone for those who are at risk for opioid overdose.

Dr. Anderson: Just so we are clear, are you in favor of regular prescribing of naloxone, along with prescriptions for opioids? Is that correct?

Dr. Adams: I issued the first Surgeon General’s advisory from more than 10 years earlier this year to help folks understand that over half of our opioid overdoses occur in a home setting. We all know that an anoxic brain injury occurs in 4-5 minutes. We also know that most ambulances and first responders aren’t going to show up in 4-5 minutes.

If we want to make a dent in this overdose epidemic, we need everyone to consider themselves a first responder. We need to look at it the same as we look at CPR; we need everyone carrying naloxone. That was one of the big pushes from my Surgeon General’s advisory.

How can providers help? Well, they can coprescribe naloxone to folks on high morphine milligram equivalents (MME) who are at risk. If grandma has naloxone at home and her grandson overdoses in the garage, then at least it’s in the same house. Naloxone is not the treatment for the opioid epidemic. But we can’t get someone who is dead into treatment.

I have no illusions that simply making naloxone available is going to turn the tide, but it certainly is an important part of it.

Dr. Anderson: From your unique viewpoint, how much progress do you see in relation to the opioid epidemic? Do you think we’re approaching an inflection point, or do you think there’s a long way to go before this starts to turn around?

Dr. Adams: When I talk about the opioid epidemic, I have two angles. No.1, I want to raise awareness about the opioid epidemic – the severity of it, and how everyone can lean into it in their own way. Whether it’s community citizens, providers, law enforcement, the business community, whomever.

But in addition to raising awareness, I want to instill hope.

I was in Huntington, West Virginia, just a few weeks ago at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. They’ve been able to turn their opioid overdose rates around by providing peer recovery coaches to individuals and making sure naloxone is available throughout the community. You save the life and then you connect them to care.

We know that the folks who are at highest risk for overdose deaths are the ones who just overdosed. They come out of the ER where we’ve watched them for a few hours and then we send them right back out into the arms of the drug dealer to do exactly what we know they will do medically because we’ve thrown them into withdrawal and they try to get their next fix.

If we can partner with law enforcement, then we can turn our opioid overdose rates around.

A story of recovery that I want to share with you is about a guy named Jonathan, who I met when I was in Rhode Island.

Jonathan overdosed, but his roommate had access to naloxone, which he administered. Jonathan was taken to the ER and then connected with a peer recovery coach. He is now in recovery and has actually become a peer recovery coach himself. Saving this one life will now enable us to save many more.

Yet we still prescribe more than 80% of the world’s opioids to less than 5% of the world’s population. So, we still have an overprescribing epidemic, but we’ve surpassed the inflection point there. Prescribing is coming down.

But another part of this epidemic was that we squeezed the balloon in one place and, as prescribing opioids went down, lots of people switched over to heroin. That’s when we really first started to see overdose rates go up.

Well, it’s important for folks to know that, through law enforcement, through partnerships with the public health community, through an increase in syringe service programs, and through other touch points, heroin use is now going down in most places.

Unfortunately, now we’re seeing the third wave of the epidemic, and that’s fentanyl and carfentanil.

Vice Admiral Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, is the 20th Surgeon General of the United States, a post created in 1871.

Dr. Adams holds degrees in biochemistry and psychology from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County; a master’s degree in public health from the University of California, Berkeley; and a medical degree from the Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is a board-certified anesthesiologist and associate clinical professor of anesthesia at Indiana University.

At the 2018 Executive Advisory Board meeting of the Doctors Company, Richard E. Anderson, MD, FACP, chairman and chief executive officer of the Doctors Company, spoke with Dr. Adams about the opioid epidemic’s enormous impact on communities and health services in the United States.

Dr. Anderson: Dr. Adams, you’ve been busy since taking over as Surgeon General of the United States. What are some of the key challenges that you’re facing in this office?

Dr. Adams: You know, there are many challenges facing our country, but it boils down to a lack of wellness. We know that only 10% of health is due to health care, 20% of health is genetics, and the rest is a combination of behavior and environment.

My motto is “better health through better partnerships,” because I firmly believe that if we break out of our silos and reach across the traditional barriers that have been put up by funding, by reimbursement, and by infrastructure, then we can ultimately achieve wellness in our communities.

You asked what I’ve been focused on as Surgeon General. Well, I’m focused on three main areas right now.

No. 1 is the opioid epidemic. It is a scourge across our country. A person dies every 12½ minutes from an opioid overdose and that’s far too many. Especially when we know that many of those deaths can be prevented.

Another area I’m focused on is demonstrating the link between community health and economic prosperity. We want folks to invest in health because we know that not only will it achieve better health for individuals and communities but it will create a more prosperous nation, also.

And finally, I’m raising awareness about the links between our nation’s health and our safety and security – particularly our national security. Unfortunately, 7 out of 10 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 years old in our country are ineligible for military service. That’s because they can’t pass the physical, they can’t meet the educational requirements, or they have a criminal record.

So, our nation’s poor health is not just a matter of diabetes or heart disease 20 or 30 years down the road. We are literally a less-safe country right now because we’re an unhealthy country.

Dr. Anderson: Regarding the opioid epidemic, what are some of the programs that are available today that you find effective? What would you like to see us do as a nation to respond to the epidemic?

Dr. Adams: Recently, I was at a hospital in Alaska where they have implemented a neonatal abstinence syndrome protocol and program that is being looked at around the country – and others are attempting to replicate it.

We know that if you keep mom and baby together, baby does better, mom does better, hospital stays are shorter, costs go down, and you’re keeping that family unit intact. This prevents future problems for both the baby and the mother. That’s just one small example.

I’m also very happy to see that the prescribing of opioids is going down 20%-25% across the country. And there are even larger decreases in the military and veteran communities. That’s really a testament to doctors and the medical profession finally waking up. And I say this as a physician myself, as an anesthesiologist, as someone who is involved in acute and chronic pain management.

Four out of five people with substance use disorder say they started with a prescription opioid. Many physicians will say, “Those aren’t my patients,” but unfortunately when we look at the PDMP [prescription drug monitoring program] data across the country we do a poor job of predicting who is and who isn’t going to divert. It may not be your patient, but it could be their son or the babysitter who is diverting those overprescribed opioids.

One thing that I really think we need to lean into as health care practitioners is providing medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. We know that the gold standard for treatment and recovery is medication-assisted treatment of some form. But we also know it’s not nearly available enough and that there are barriers on the federal and state levels.

We need you to continue to talk to your congressional representatives and let them know which barriers you perceive because the data waiver comes directly from Congress.

Still, any ER can prescribe up to 3 days of MAT to someone. I’d much rather have our ER doctors putting patients on MAT and then connecting them to treatment, than sending them back out into the arms of a drug dealer after they put them into acute withdrawal with naloxone.

We also have too many pregnant women who want help but can’t find any treatment because no one out there will take care of pregnant moms. We need folks to step up to the plate and get that data waiver in our ob/gyn and primary care sectors.

Ultimately, we need hospitals and health care leaders to create an environment that makes providers feel comfortable providing that service by giving them the training and the support to be able to do it.

We also need to make sure we’re co-prescribing naloxone for those who are at risk for opioid overdose.

Dr. Anderson: Just so we are clear, are you in favor of regular prescribing of naloxone, along with prescriptions for opioids? Is that correct?

Dr. Adams: I issued the first Surgeon General’s advisory from more than 10 years earlier this year to help folks understand that over half of our opioid overdoses occur in a home setting. We all know that an anoxic brain injury occurs in 4-5 minutes. We also know that most ambulances and first responders aren’t going to show up in 4-5 minutes.

If we want to make a dent in this overdose epidemic, we need everyone to consider themselves a first responder. We need to look at it the same as we look at CPR; we need everyone carrying naloxone. That was one of the big pushes from my Surgeon General’s advisory.

How can providers help? Well, they can coprescribe naloxone to folks on high morphine milligram equivalents (MME) who are at risk. If grandma has naloxone at home and her grandson overdoses in the garage, then at least it’s in the same house. Naloxone is not the treatment for the opioid epidemic. But we can’t get someone who is dead into treatment.

I have no illusions that simply making naloxone available is going to turn the tide, but it certainly is an important part of it.

Dr. Anderson: From your unique viewpoint, how much progress do you see in relation to the opioid epidemic? Do you think we’re approaching an inflection point, or do you think there’s a long way to go before this starts to turn around?

Dr. Adams: When I talk about the opioid epidemic, I have two angles. No.1, I want to raise awareness about the opioid epidemic – the severity of it, and how everyone can lean into it in their own way. Whether it’s community citizens, providers, law enforcement, the business community, whomever.

But in addition to raising awareness, I want to instill hope.

I was in Huntington, West Virginia, just a few weeks ago at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. They’ve been able to turn their opioid overdose rates around by providing peer recovery coaches to individuals and making sure naloxone is available throughout the community. You save the life and then you connect them to care.

We know that the folks who are at highest risk for overdose deaths are the ones who just overdosed. They come out of the ER where we’ve watched them for a few hours and then we send them right back out into the arms of the drug dealer to do exactly what we know they will do medically because we’ve thrown them into withdrawal and they try to get their next fix.

If we can partner with law enforcement, then we can turn our opioid overdose rates around.

A story of recovery that I want to share with you is about a guy named Jonathan, who I met when I was in Rhode Island.

Jonathan overdosed, but his roommate had access to naloxone, which he administered. Jonathan was taken to the ER and then connected with a peer recovery coach. He is now in recovery and has actually become a peer recovery coach himself. Saving this one life will now enable us to save many more.

Yet we still prescribe more than 80% of the world’s opioids to less than 5% of the world’s population. So, we still have an overprescribing epidemic, but we’ve surpassed the inflection point there. Prescribing is coming down.

But another part of this epidemic was that we squeezed the balloon in one place and, as prescribing opioids went down, lots of people switched over to heroin. That’s when we really first started to see overdose rates go up.

Well, it’s important for folks to know that, through law enforcement, through partnerships with the public health community, through an increase in syringe service programs, and through other touch points, heroin use is now going down in most places.

Unfortunately, now we’re seeing the third wave of the epidemic, and that’s fentanyl and carfentanil.

Sore on nose

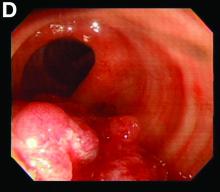

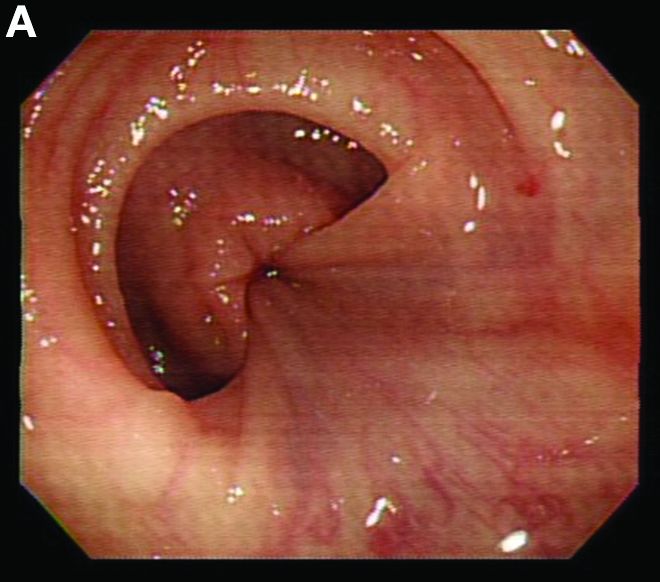

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that it could be a skin cancer because any nonhealing lesion in sun-exposed areas could be skin cancer (especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma).

He explained this to the patient and obtained written consent for a shave biopsy. He told the patient that the biopsy would likely leave an indentation in the involved area, but since treating the sore would likely require a second surgery, this indented area could be cut out and repaired with sutures. The patient indicated that he was more concerned about getting a proper diagnosis than he was about the appearance of the biopsy site.

The physician injected the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. (Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths.”) The shave biopsy was performed using a Dermablade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was referred for Mohs surgery to get the best cure and cosmetic result.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

American Heart Association guideline on the management of blood cholesterol

The purpose of this guideline is to provide direction for the management of patients with high blood cholesterol to decrease the incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease. The update was undertaken because new evidence has emerged since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline about additional cholesterol-lowering agents including ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement and therapeutic modalities

In adults aged 20 years and older who are not on lipid-lowering therapy, measurement of a lipid profile is recommended and is an effective way to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and documenting baseline LDL-C.

Statin therapy is divided into three categories: High-intensity statin therapy aims for lowering LDL-C levels by more than 50%, moderate-intensity therapy by 30%-49%, and low-intensity therapy by less than 30%.

Cholesterol management groups

In all individuals at all ages, emphasizing a heart-healthy lifestyle, meaning appropriate diet and exercise, to decrease the risk of developing ASCVD should be advised.

Individuals fall into groups with distinct risk of ASCVD or recurrence of ASCVD and the recommendations are organized according to these risk groups.

Secondary ASCVD prevention: Patients who already have ASCVD by virtue of having had an event or established diagnosis (MI, angina, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease) fall into the secondary prevention category:

- Patients aged 75 years and younger with clinical ASCVD: High-intensity statin therapy should be initiated with aim to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%. In patients who experience statin-related side effects, a moderate-intensity statin should be initiated with the aim to reduce LDL-C by 30%-49%.

- In very high-risk patients with an LDL-C above 70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the use of a non–statin cholesterol-lowering agent with an LDL-C goal under 70 mg/dL. Ezetimibe (Zetia) can be used initially and if LDL-C remains above 70 mg/dL, then consideration can be given to the addition of a PCSK9-inhibitor therapy (strength of recommendation: ezetimibe – moderate; PCSK9 – strong). The guideline discusses that, even though the evidence supports the efficacy of PCSK9s in reducing the incidence of ASCVD events, the expense of PCSK9 inhibitors give them a high cost, compared with value.

- For patients more than age 75 years with established ASCVD, it is reasonable to continue high-intensity statin therapy if patient is tolerating treatment.

Severe hypercholesterolemia:

- Patients with LDL-C above 190 mg/dL do not need a 10-year risk score calculated. These individuals should receive maximally tolerated statin therapy.

- If patient is unable to achieve 50% reduction in LDL-C and/or have an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL, the addition of ezetimibe therapy is reasonable.

- If LDL-C is still greater than 100mg/dL on a statin plus ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered. It should be recognized that the addition of a PCSK9 in this circumstance is classified as a weak recommendation.

Diabetes mellitus in adults:

- In patients aged 40-75 years with diabetes, regardless of 10-year ASCVD risk, should be prescribed a moderate-intensity statin (strong recommendation).

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and multiple ASCVD risk factors, it is reasonable to prescribe high-intensity statin therapy with goal to reduce LDL-C by more than 50%.

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL-C levels by 50% or more.

- In patients aged 20-39 years with diabetes that is either of long duration (at least 10 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus; at least 20 years, type 1 diabetes mellitus), or with end-organ damage including albuminuria, chronic renal insufficiency, retinopathy, neuropathy, or ankle-brachial index below 0.9, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy (weak recommendation).

Primary prevention in adults: Adults with LDL 70-189 mg/dL and a 10-year risk of a first ASCVD event (fatal and nonfatal MI or stroke) should be estimated by using the pooled cohort equation. Adults should be categorized according to calculated risk of developing ASCVD: low risk (less than 5%), borderline risk (5% to less than 7.5%), intermediate risk (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), and high risk (20% and higher) (strong recommendation:

- Individualized risk and treatment discussion should be done with clinician and patient.

- Adults in the intermediate-risk group (7.5% and higher to less than 20%), should be placed on moderate-intensity statin with LDL-C goal reduction of more than 30%; for optimal risk reduction, especially in high-risk patients, an LDL-C reduction of more than 50% (strong recommendation).

- Risk-enhancing factors can favor initiation of intensification of statin therapy.

- If a decision about statin therapy is uncertain, consider measuring coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels. If CAC is zero, statin therapy may be withheld or delayed, except those with diabetes as above, smokers, and strong familial hypercholesterolemia with premature ASCVD. If CAC score is 1-99, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy for patients older than age 55 years; If CAC score is 100 or higher or in the 75th percentile or higher, it is reasonable to initiate a statin.

Statin safety: Prior to initiation of a statin, a clinician-patient discussion is recommended detailing ASCVD risk reduction and the potential for side effects/drug interactions. In patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), a detailed account for secondary causes is recommended. In patients with true SAMS, it is recommended to check a creatine kinase level and hepatic function panel; however, routine measurements are not useful. In patients with statin-associated side effects that are not severe, reassess and rechallenge patient to achieve maximal lowering of LDL-C with a modified dosing regimen.

The bottom line

Lifestyle modification is important at all ages, with specific population-guided strategies for lowering cholesterol in subgroups as discussed above. Major changes to the AHA/ACC Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines now mention new agents for lowering cholesterol and using CAC levels as predictability scoring.

Reference

Grundy SM et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018 Nov 10.

Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Palko is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Hospital.

The purpose of this guideline is to provide direction for the management of patients with high blood cholesterol to decrease the incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease. The update was undertaken because new evidence has emerged since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline about additional cholesterol-lowering agents including ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement and therapeutic modalities

In adults aged 20 years and older who are not on lipid-lowering therapy, measurement of a lipid profile is recommended and is an effective way to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and documenting baseline LDL-C.

Statin therapy is divided into three categories: High-intensity statin therapy aims for lowering LDL-C levels by more than 50%, moderate-intensity therapy by 30%-49%, and low-intensity therapy by less than 30%.

Cholesterol management groups

In all individuals at all ages, emphasizing a heart-healthy lifestyle, meaning appropriate diet and exercise, to decrease the risk of developing ASCVD should be advised.

Individuals fall into groups with distinct risk of ASCVD or recurrence of ASCVD and the recommendations are organized according to these risk groups.

Secondary ASCVD prevention: Patients who already have ASCVD by virtue of having had an event or established diagnosis (MI, angina, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease) fall into the secondary prevention category:

- Patients aged 75 years and younger with clinical ASCVD: High-intensity statin therapy should be initiated with aim to reduce LDL-C levels by 50%. In patients who experience statin-related side effects, a moderate-intensity statin should be initiated with the aim to reduce LDL-C by 30%-49%.

- In very high-risk patients with an LDL-C above 70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the use of a non–statin cholesterol-lowering agent with an LDL-C goal under 70 mg/dL. Ezetimibe (Zetia) can be used initially and if LDL-C remains above 70 mg/dL, then consideration can be given to the addition of a PCSK9-inhibitor therapy (strength of recommendation: ezetimibe – moderate; PCSK9 – strong). The guideline discusses that, even though the evidence supports the efficacy of PCSK9s in reducing the incidence of ASCVD events, the expense of PCSK9 inhibitors give them a high cost, compared with value.

- For patients more than age 75 years with established ASCVD, it is reasonable to continue high-intensity statin therapy if patient is tolerating treatment.

Severe hypercholesterolemia:

- Patients with LDL-C above 190 mg/dL do not need a 10-year risk score calculated. These individuals should receive maximally tolerated statin therapy.

- If patient is unable to achieve 50% reduction in LDL-C and/or have an LDL-C level of 100 mg/dL, the addition of ezetimibe therapy is reasonable.

- If LDL-C is still greater than 100mg/dL on a statin plus ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered. It should be recognized that the addition of a PCSK9 in this circumstance is classified as a weak recommendation.

Diabetes mellitus in adults:

- In patients aged 40-75 years with diabetes, regardless of 10-year ASCVD risk, should be prescribed a moderate-intensity statin (strong recommendation).

- In adults with diabetes mellitus and multiple ASCVD risk factors, it is reasonable to prescribe high-intensity statin therapy with goal to reduce LDL-C by more than 50%.