User login

Guideline authors inconsistently disclose conflicts

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730; Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

Statement from the AGA on the integrity of AGA’s clinical guideline process

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) understands how important it is for AGA members, patients, and the public at large to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. In developing guidelines, our goal is to maintain a high level of methodologic rigor through the utilization of an evidence-based approach that is very transparent.

However, not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Academy of Medicine’s (formerly the Institute of Medicine’s) standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines. The guideline should be based on a systematic review of the evidence, focus on transparency, have a rigorous conflict of interest system in place, include the involvement of an unconflicted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system-trained methodologist, ideally as a cochair, and the recommendations should be concise and actionable. AGA follows a transparent, independent guideline development process that is not subject to company influence or bias and fully complies with the Academy of Medicine’s criteria for trustworthy guidelines.

AGA has been proactive in developing policies to minimize bias in our guidelines. AGA requires that the Chair of the Guideline Development Group, and a majority of Guideline (and other clinical practice documents) Development Group members are free of conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of the guideline. At the time of invitation, we ask our panel members to disclose any and all potential conflicts. Furthermore, all author disclosures are verified by means of accessing publicly available sources (such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payment database) prior to their involvement on the panel.

AGA strives to be transparent in reporting commercial bias and independent of any industry influence in the development of our clinical practice documents. Our goal is to produce the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines possible for our members.

Learn more about AGA’s clinical guideline process (https://www.gastro.org/guidelines).

Yngve T. Falck-Ytter, MD, AGAF, is chair, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, is chair-elect, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730; Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

Statement from the AGA on the integrity of AGA’s clinical guideline process

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) understands how important it is for AGA members, patients, and the public at large to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. In developing guidelines, our goal is to maintain a high level of methodologic rigor through the utilization of an evidence-based approach that is very transparent.

However, not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Academy of Medicine’s (formerly the Institute of Medicine’s) standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines. The guideline should be based on a systematic review of the evidence, focus on transparency, have a rigorous conflict of interest system in place, include the involvement of an unconflicted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system-trained methodologist, ideally as a cochair, and the recommendations should be concise and actionable. AGA follows a transparent, independent guideline development process that is not subject to company influence or bias and fully complies with the Academy of Medicine’s criteria for trustworthy guidelines.

AGA has been proactive in developing policies to minimize bias in our guidelines. AGA requires that the Chair of the Guideline Development Group, and a majority of Guideline (and other clinical practice documents) Development Group members are free of conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of the guideline. At the time of invitation, we ask our panel members to disclose any and all potential conflicts. Furthermore, all author disclosures are verified by means of accessing publicly available sources (such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payment database) prior to their involvement on the panel.

AGA strives to be transparent in reporting commercial bias and independent of any industry influence in the development of our clinical practice documents. Our goal is to produce the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines possible for our members.

Learn more about AGA’s clinical guideline process (https://www.gastro.org/guidelines).

Yngve T. Falck-Ytter, MD, AGAF, is chair, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, is chair-elect, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730; Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

Statement from the AGA on the integrity of AGA’s clinical guideline process

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) understands how important it is for AGA members, patients, and the public at large to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. In developing guidelines, our goal is to maintain a high level of methodologic rigor through the utilization of an evidence-based approach that is very transparent.

However, not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Academy of Medicine’s (formerly the Institute of Medicine’s) standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines. The guideline should be based on a systematic review of the evidence, focus on transparency, have a rigorous conflict of interest system in place, include the involvement of an unconflicted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system-trained methodologist, ideally as a cochair, and the recommendations should be concise and actionable. AGA follows a transparent, independent guideline development process that is not subject to company influence or bias and fully complies with the Academy of Medicine’s criteria for trustworthy guidelines.

AGA has been proactive in developing policies to minimize bias in our guidelines. AGA requires that the Chair of the Guideline Development Group, and a majority of Guideline (and other clinical practice documents) Development Group members are free of conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of the guideline. At the time of invitation, we ask our panel members to disclose any and all potential conflicts. Furthermore, all author disclosures are verified by means of accessing publicly available sources (such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payment database) prior to their involvement on the panel.

AGA strives to be transparent in reporting commercial bias and independent of any industry influence in the development of our clinical practice documents. Our goal is to produce the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines possible for our members.

Learn more about AGA’s clinical guideline process (https://www.gastro.org/guidelines).

Yngve T. Falck-Ytter, MD, AGAF, is chair, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, is chair-elect, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

DRESS Syndrome Induced by Telaprevir: A Potentially Fatal Adverse Event in Chronic Hepatitis C Therapy

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

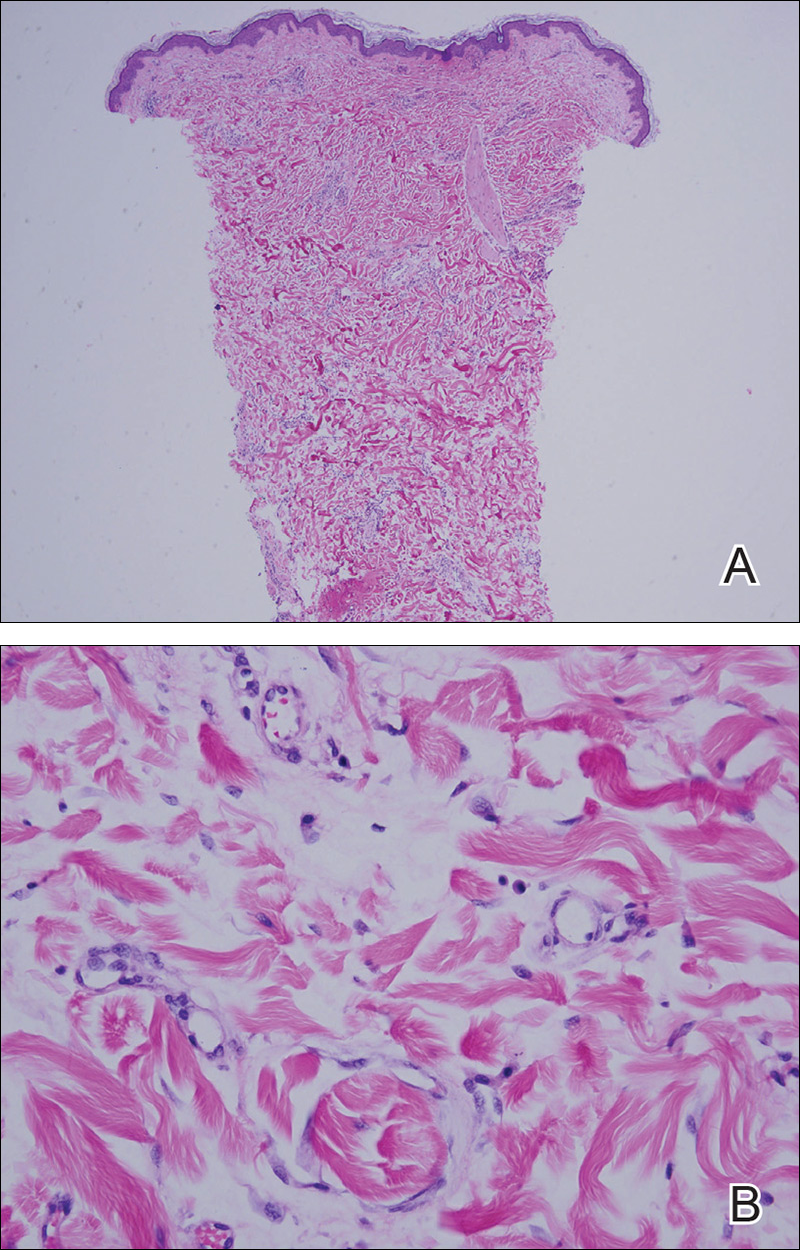

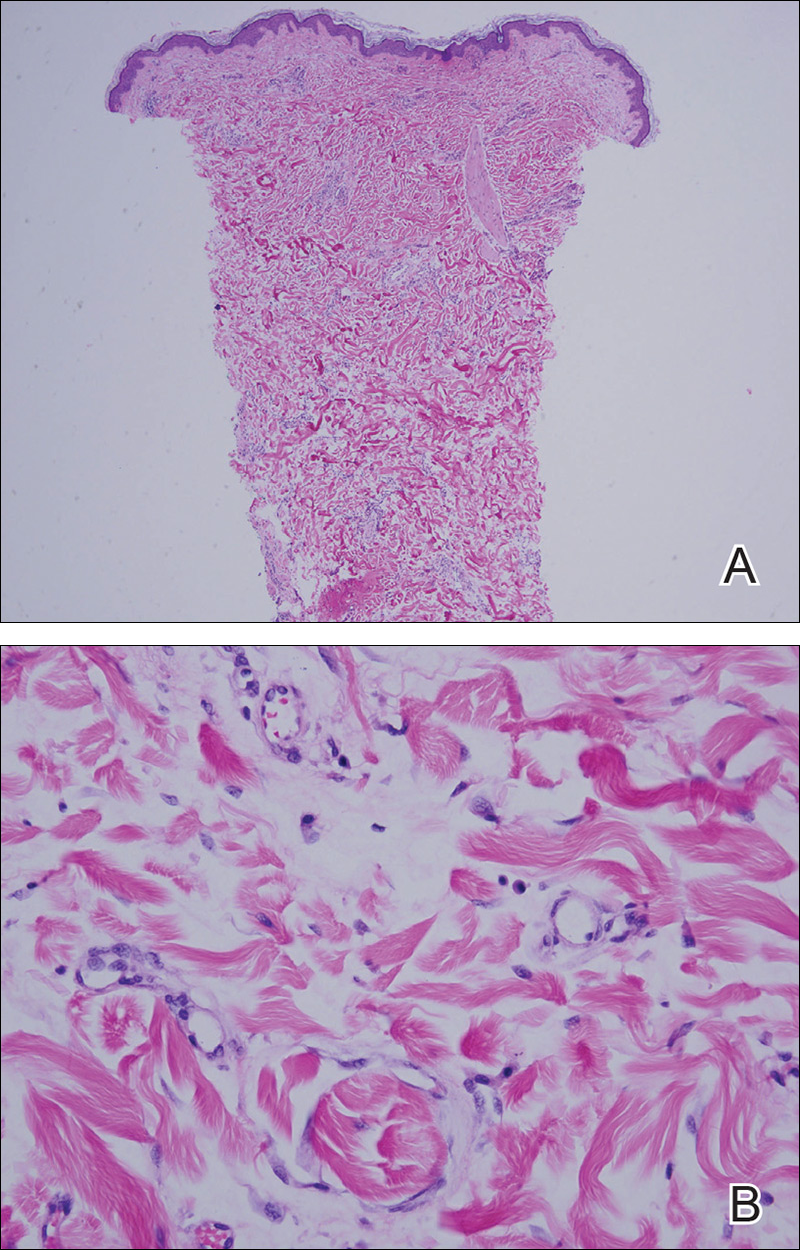

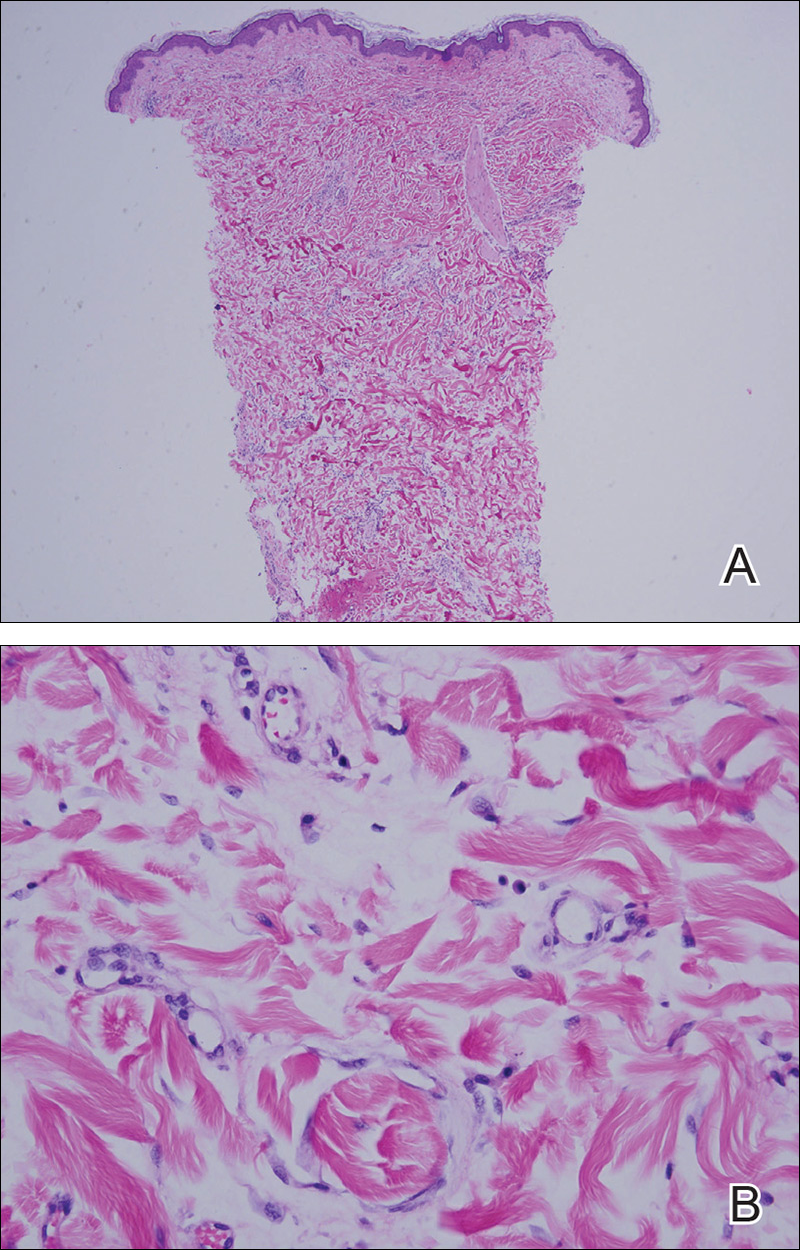

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

Practice Points

- DRESS syndrome is characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests.

- Severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages; in the third and fourth stages, adequate patient monitoring is necessary.

- Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. Its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

Night sweats

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

Eumycetoma Pedis in an Albanian Farmer

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

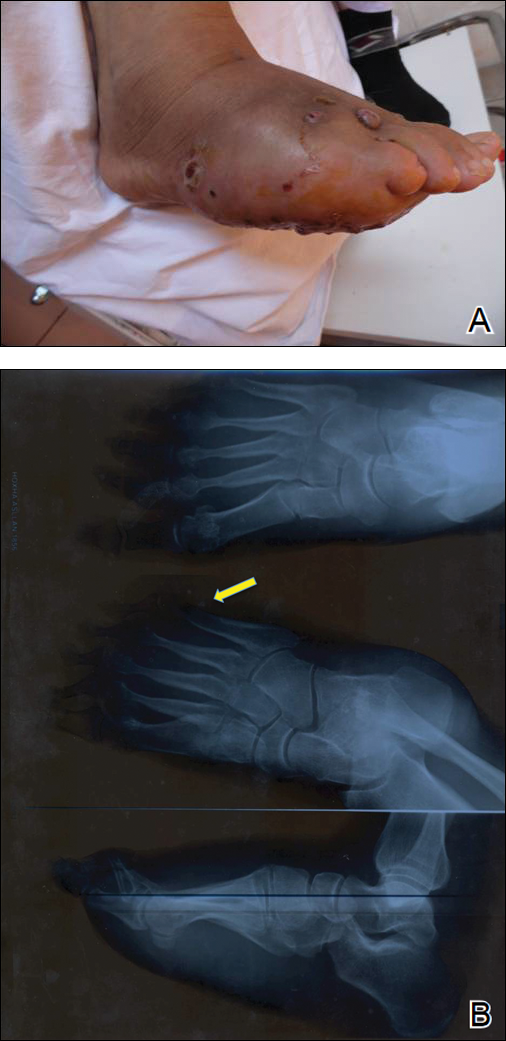

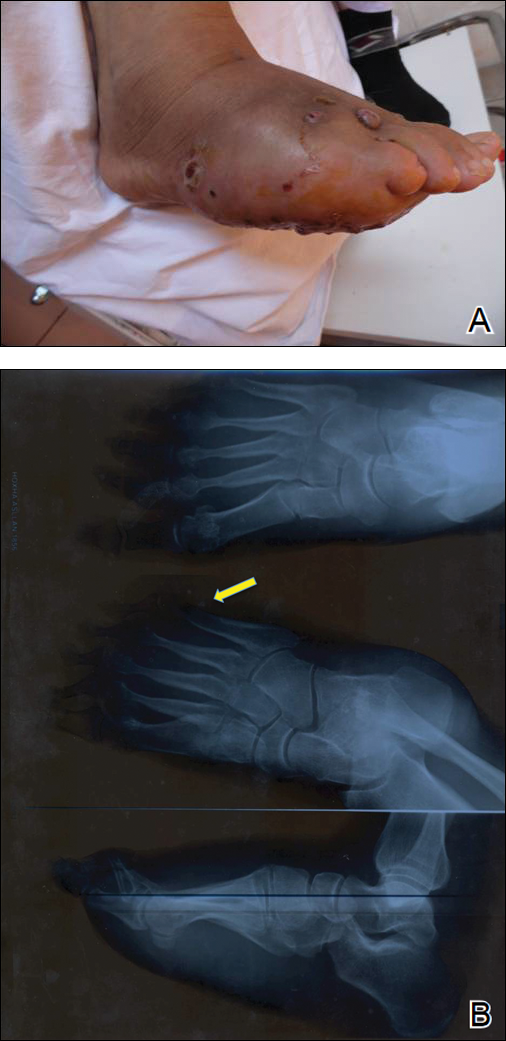

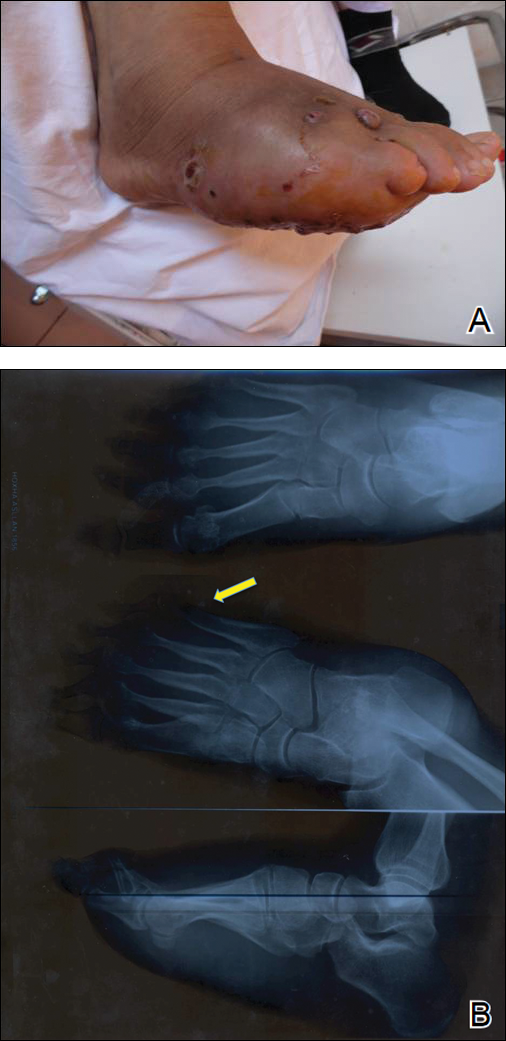

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

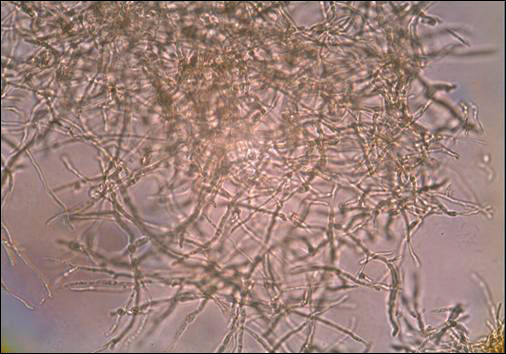

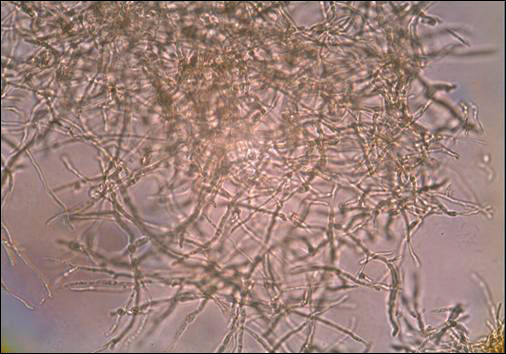

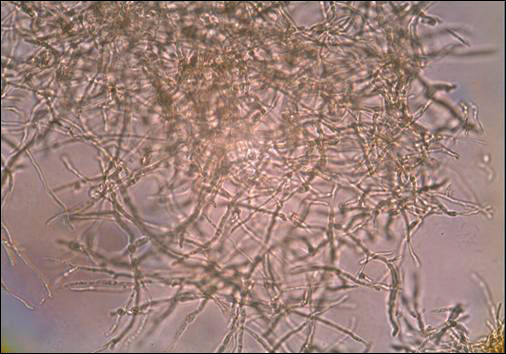

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

Practice Points