User login

Your guide to ASH 2018: Abstracts to watch

With more than 3,000 scientific abstracts at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, it can be tough to figure out what research is most relevant to practice. But the editorial advisory board of Hematology News is making it easier this year with their picks for what to watch and why.

Lymphomas

Brian T. Hill, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, offered his top picks in lymphoma research. Results of the phase 3 international Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 will be presented during the ASH plenary session at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Hall AB of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 6). The study compared bendamustine plus rituximab with ibrutinib and the combination of ibrutinib plus rituximab to see if the ibrutinib-containing therapies would have superior progression-free survival (PFS) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), compared with chemoimmunotherapy. Results indicate that ibrutinib had superior PFS in older patients with CLL and could be a standard of care in this population.

The study is worth watching because it is the first report of a head-to-head trial of chemotherapy versus ibrutinib for first-line treatment of CLL, Dr. Hill said.

Two more studies offer important reports of “real world” experiences with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

In one multicenter retrospective study, researchers evaluated the outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma when it is used a standard care. The researchers will report that 30-day responses in the real-world setting were comparable to the best responses seen in the ZUMA-1 trial. The full results will be reported at 9:30 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 91).

Another retrospective analysis looked at the use of axi-cell and revealed some critical differences from ZUMA-1, specifically the overall response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) rate were lower than those reported in the pivotal clinical trial. The findings will be reported at 9:45 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 92).

Researchers will also present the unblinded results from the ECHELON-2 study, which compared the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) versus standard CHOP for the treatment of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The results will be presented at 6:15 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego convention center (Abstract 997).

Previously reported blinded pooled data showed that the treatment was well tolerated with 3-year PFS of 53% and OS of 73%.

“This should be a new standard of care for T-cell lymphomas,” Dr. Hill said.

CAR T-cell therapy

There are a number of abstracts featuring the latest results on CAR T-cell therapy. Helen Heslop, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, recommended an updated analysis from the ELIANA study, which looked at the efficacy and safety of tisagenlecleucel in for children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“Longer-term follow-up of the ELIANA study shows encouraging remission-duration data in pediatric and young adults with ALL without additional therapy,” Dr. Heslop said.

The findings will be presented at 4:30 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6A at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 895).

Another notable presentation will feature results from a phase 1B/2 trial evaluating infusion of CAR T cells targeting the CD30 molecule and encoding the CD28 endodomain (CD30.CAR-Ts) after lymphodepleting chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory CD30+ Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers will report that there was a significant PFS advances for who received the highest dose level of the CAR T treatment, combined with bendamustine and fludarabine.

The study will be presented at 11 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 681).

Dr. Heslop also recommends another study being presented in the same session, which also shows encouraging results with CD30.CAR-Ts. Dr. Heslop is one of the co-investigators on the phase 1 RELY-30 trial, which is evaluating the efficacy of CD30.CAR-Ts after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Preliminary results suggest a substantial improvement in efficacy. The findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 680).

MDS/MPN

Vikas Gupta, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, highlighted three abstracts to watch in the areas of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN).

The phase 3 Medalist trial is a randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of luspatercept to treatment anemia in patients with MDS with ring sideroblasts who require red blood cell transfusion. The researchers will report significantly reduced transfusion burdens for luspatercept, compared with placebo.

“This is a practice-changing, pivotal trial in the field of MDS for the treatment of anemia,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 during the plenary session in Hall AB in the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 1).

Also during the Sunday plenary session is a presentation on MPN therapy (Abstract 4). Researchers will present data on secreted mutant calreticulins as rogue cytokines trigger thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR) activation, specifically in CALR-mutated cells.

“This study investigates in to the mechanistic oncogenetic aspects of mutant calreticulin, and has potential for therapeutic approaches in the future,” Dr. Gupta said.

The ASH meeting will also feature the final analysis of the MPN-RC 112 consortium trial of pegylated interferon alfa-2a versus hydroxyurea for the treatment of high-risk polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET). The researchers will report that the CR rates at 12 and 24 months were similar in patients treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and hydroxyurea, but pegylated interferon alfa-2a was associated with a higher rate of serious toxicities.

“There is a continuous debate on optimal first-line cytoreductive therapy for high risk PV/ET, and this is one of the first randomized study to answer this question,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 7 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Grand Hall D at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 577).

AML

For attendees interested in the latest developments in acute myeloid leukemia, Thomas Fischer, MD, of Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg (Germany), highlighted three don’t-miss sessions.

In an analysis of a large cohort of FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients in the RATIFY trial, researchers looked at the prognostic impact of ITD insertion site.

“Interestingly, in this large cohort of 452 FLT3-ITD mutated AML, the negative prognostic impact of beta1-sheet insertion site of FLT3-ITD could be confirmed,” Dr. Fischer said. “Further analysis of a potential predictive effect on outcome of midostaurin treatment is ongoing and will be very interesting.”

The findings will be presented at 5 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 435).

Another notable presentation features results from the phase 2 RADIUS trial, a randomized study comparing standard of care, with and without midostaurin, after allogeneic stem cell transplant in FLT3-ITD–mutated AML.

“Here, efficacy and toxicity of midostaurin was investigated in a [minimal residual disease] situation post-alloSCT,” Dr. Fischer said. “Interestingly, adding midostaurin to standard of care reduced the risk of relapse at 18 months post-alloSCT by 46%.”

The complete findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 662).

Dr. Fischer singled out another study looking at the efficacy and safety of single-agent quizartinib in patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML. In this large, randomized trial the researchers noted a significant improvement in CR rates and survival benefit with the single agent FLT3 inhibitors, compared with salvage chemotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory mutated AML.

The findings will be presented at 8 a.m. on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 563).

Notable posters

Iberia Romina Sosa, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, suggested several posters worth visiting in the areas of thrombosis and bleeding.

Poster 1134 looks at the TNF-alpha driven inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the platelet hyperreactivity of aging and MPN.

How do you know if your therapy for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is working? Poster 3736 examines the measurement of cell-derived microparticles as a possible tool to monitor response to therapy.

You don’t have to be taking aspirin to have a bleeding profile characteristic with consumption of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor. Poster 1156 provides a first report of a platelet function disorder caused by autosomal recessive inheritance of PTGS1.

Poster 2477 takes a closer look at fitusiran, an antithrombin inhibitor, which improves thrombin generation in patients with hemophilia A or B. Protocol amendments for safety monitoring move fitusiran to phase 3 trials, Dr. Sosa said.

With more than 3,000 scientific abstracts at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, it can be tough to figure out what research is most relevant to practice. But the editorial advisory board of Hematology News is making it easier this year with their picks for what to watch and why.

Lymphomas

Brian T. Hill, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, offered his top picks in lymphoma research. Results of the phase 3 international Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 will be presented during the ASH plenary session at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Hall AB of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 6). The study compared bendamustine plus rituximab with ibrutinib and the combination of ibrutinib plus rituximab to see if the ibrutinib-containing therapies would have superior progression-free survival (PFS) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), compared with chemoimmunotherapy. Results indicate that ibrutinib had superior PFS in older patients with CLL and could be a standard of care in this population.

The study is worth watching because it is the first report of a head-to-head trial of chemotherapy versus ibrutinib for first-line treatment of CLL, Dr. Hill said.

Two more studies offer important reports of “real world” experiences with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

In one multicenter retrospective study, researchers evaluated the outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma when it is used a standard care. The researchers will report that 30-day responses in the real-world setting were comparable to the best responses seen in the ZUMA-1 trial. The full results will be reported at 9:30 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 91).

Another retrospective analysis looked at the use of axi-cell and revealed some critical differences from ZUMA-1, specifically the overall response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) rate were lower than those reported in the pivotal clinical trial. The findings will be reported at 9:45 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 92).

Researchers will also present the unblinded results from the ECHELON-2 study, which compared the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) versus standard CHOP for the treatment of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The results will be presented at 6:15 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego convention center (Abstract 997).

Previously reported blinded pooled data showed that the treatment was well tolerated with 3-year PFS of 53% and OS of 73%.

“This should be a new standard of care for T-cell lymphomas,” Dr. Hill said.

CAR T-cell therapy

There are a number of abstracts featuring the latest results on CAR T-cell therapy. Helen Heslop, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, recommended an updated analysis from the ELIANA study, which looked at the efficacy and safety of tisagenlecleucel in for children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“Longer-term follow-up of the ELIANA study shows encouraging remission-duration data in pediatric and young adults with ALL without additional therapy,” Dr. Heslop said.

The findings will be presented at 4:30 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6A at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 895).

Another notable presentation will feature results from a phase 1B/2 trial evaluating infusion of CAR T cells targeting the CD30 molecule and encoding the CD28 endodomain (CD30.CAR-Ts) after lymphodepleting chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory CD30+ Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers will report that there was a significant PFS advances for who received the highest dose level of the CAR T treatment, combined with bendamustine and fludarabine.

The study will be presented at 11 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 681).

Dr. Heslop also recommends another study being presented in the same session, which also shows encouraging results with CD30.CAR-Ts. Dr. Heslop is one of the co-investigators on the phase 1 RELY-30 trial, which is evaluating the efficacy of CD30.CAR-Ts after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Preliminary results suggest a substantial improvement in efficacy. The findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 680).

MDS/MPN

Vikas Gupta, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, highlighted three abstracts to watch in the areas of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN).

The phase 3 Medalist trial is a randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of luspatercept to treatment anemia in patients with MDS with ring sideroblasts who require red blood cell transfusion. The researchers will report significantly reduced transfusion burdens for luspatercept, compared with placebo.

“This is a practice-changing, pivotal trial in the field of MDS for the treatment of anemia,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 during the plenary session in Hall AB in the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 1).

Also during the Sunday plenary session is a presentation on MPN therapy (Abstract 4). Researchers will present data on secreted mutant calreticulins as rogue cytokines trigger thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR) activation, specifically in CALR-mutated cells.

“This study investigates in to the mechanistic oncogenetic aspects of mutant calreticulin, and has potential for therapeutic approaches in the future,” Dr. Gupta said.

The ASH meeting will also feature the final analysis of the MPN-RC 112 consortium trial of pegylated interferon alfa-2a versus hydroxyurea for the treatment of high-risk polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET). The researchers will report that the CR rates at 12 and 24 months were similar in patients treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and hydroxyurea, but pegylated interferon alfa-2a was associated with a higher rate of serious toxicities.

“There is a continuous debate on optimal first-line cytoreductive therapy for high risk PV/ET, and this is one of the first randomized study to answer this question,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 7 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Grand Hall D at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 577).

AML

For attendees interested in the latest developments in acute myeloid leukemia, Thomas Fischer, MD, of Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg (Germany), highlighted three don’t-miss sessions.

In an analysis of a large cohort of FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients in the RATIFY trial, researchers looked at the prognostic impact of ITD insertion site.

“Interestingly, in this large cohort of 452 FLT3-ITD mutated AML, the negative prognostic impact of beta1-sheet insertion site of FLT3-ITD could be confirmed,” Dr. Fischer said. “Further analysis of a potential predictive effect on outcome of midostaurin treatment is ongoing and will be very interesting.”

The findings will be presented at 5 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 435).

Another notable presentation features results from the phase 2 RADIUS trial, a randomized study comparing standard of care, with and without midostaurin, after allogeneic stem cell transplant in FLT3-ITD–mutated AML.

“Here, efficacy and toxicity of midostaurin was investigated in a [minimal residual disease] situation post-alloSCT,” Dr. Fischer said. “Interestingly, adding midostaurin to standard of care reduced the risk of relapse at 18 months post-alloSCT by 46%.”

The complete findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 662).

Dr. Fischer singled out another study looking at the efficacy and safety of single-agent quizartinib in patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML. In this large, randomized trial the researchers noted a significant improvement in CR rates and survival benefit with the single agent FLT3 inhibitors, compared with salvage chemotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory mutated AML.

The findings will be presented at 8 a.m. on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 563).

Notable posters

Iberia Romina Sosa, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, suggested several posters worth visiting in the areas of thrombosis and bleeding.

Poster 1134 looks at the TNF-alpha driven inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the platelet hyperreactivity of aging and MPN.

How do you know if your therapy for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is working? Poster 3736 examines the measurement of cell-derived microparticles as a possible tool to monitor response to therapy.

You don’t have to be taking aspirin to have a bleeding profile characteristic with consumption of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor. Poster 1156 provides a first report of a platelet function disorder caused by autosomal recessive inheritance of PTGS1.

Poster 2477 takes a closer look at fitusiran, an antithrombin inhibitor, which improves thrombin generation in patients with hemophilia A or B. Protocol amendments for safety monitoring move fitusiran to phase 3 trials, Dr. Sosa said.

With more than 3,000 scientific abstracts at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, it can be tough to figure out what research is most relevant to practice. But the editorial advisory board of Hematology News is making it easier this year with their picks for what to watch and why.

Lymphomas

Brian T. Hill, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, offered his top picks in lymphoma research. Results of the phase 3 international Alliance North American Intergroup Study A041202 will be presented during the ASH plenary session at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Hall AB of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 6). The study compared bendamustine plus rituximab with ibrutinib and the combination of ibrutinib plus rituximab to see if the ibrutinib-containing therapies would have superior progression-free survival (PFS) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), compared with chemoimmunotherapy. Results indicate that ibrutinib had superior PFS in older patients with CLL and could be a standard of care in this population.

The study is worth watching because it is the first report of a head-to-head trial of chemotherapy versus ibrutinib for first-line treatment of CLL, Dr. Hill said.

Two more studies offer important reports of “real world” experiences with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

In one multicenter retrospective study, researchers evaluated the outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma when it is used a standard care. The researchers will report that 30-day responses in the real-world setting were comparable to the best responses seen in the ZUMA-1 trial. The full results will be reported at 9:30 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 91).

Another retrospective analysis looked at the use of axi-cell and revealed some critical differences from ZUMA-1, specifically the overall response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) rate were lower than those reported in the pivotal clinical trial. The findings will be reported at 9:45 a.m. PT on Saturday, Dec. 1 in Pacific Ballroom 20 of the Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina (Abstract 92).

Researchers will also present the unblinded results from the ECHELON-2 study, which compared the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) versus standard CHOP for the treatment of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The results will be presented at 6:15 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego convention center (Abstract 997).

Previously reported blinded pooled data showed that the treatment was well tolerated with 3-year PFS of 53% and OS of 73%.

“This should be a new standard of care for T-cell lymphomas,” Dr. Hill said.

CAR T-cell therapy

There are a number of abstracts featuring the latest results on CAR T-cell therapy. Helen Heslop, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, recommended an updated analysis from the ELIANA study, which looked at the efficacy and safety of tisagenlecleucel in for children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“Longer-term follow-up of the ELIANA study shows encouraging remission-duration data in pediatric and young adults with ALL without additional therapy,” Dr. Heslop said.

The findings will be presented at 4:30 p.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6A at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 895).

Another notable presentation will feature results from a phase 1B/2 trial evaluating infusion of CAR T cells targeting the CD30 molecule and encoding the CD28 endodomain (CD30.CAR-Ts) after lymphodepleting chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory CD30+ Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers will report that there was a significant PFS advances for who received the highest dose level of the CAR T treatment, combined with bendamustine and fludarabine.

The study will be presented at 11 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F at the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 681).

Dr. Heslop also recommends another study being presented in the same session, which also shows encouraging results with CD30.CAR-Ts. Dr. Heslop is one of the co-investigators on the phase 1 RELY-30 trial, which is evaluating the efficacy of CD30.CAR-Ts after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Preliminary results suggest a substantial improvement in efficacy. The findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in room 6F of the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 680).

MDS/MPN

Vikas Gupta, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, highlighted three abstracts to watch in the areas of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN).

The phase 3 Medalist trial is a randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of luspatercept to treatment anemia in patients with MDS with ring sideroblasts who require red blood cell transfusion. The researchers will report significantly reduced transfusion burdens for luspatercept, compared with placebo.

“This is a practice-changing, pivotal trial in the field of MDS for the treatment of anemia,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 2 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 during the plenary session in Hall AB in the San Diego Convention Center (Abstract 1).

Also during the Sunday plenary session is a presentation on MPN therapy (Abstract 4). Researchers will present data on secreted mutant calreticulins as rogue cytokines trigger thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR) activation, specifically in CALR-mutated cells.

“This study investigates in to the mechanistic oncogenetic aspects of mutant calreticulin, and has potential for therapeutic approaches in the future,” Dr. Gupta said.

The ASH meeting will also feature the final analysis of the MPN-RC 112 consortium trial of pegylated interferon alfa-2a versus hydroxyurea for the treatment of high-risk polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET). The researchers will report that the CR rates at 12 and 24 months were similar in patients treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and hydroxyurea, but pegylated interferon alfa-2a was associated with a higher rate of serious toxicities.

“There is a continuous debate on optimal first-line cytoreductive therapy for high risk PV/ET, and this is one of the first randomized study to answer this question,” Dr. Gupta said.

The findings will be presented at 7 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Grand Hall D at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 577).

AML

For attendees interested in the latest developments in acute myeloid leukemia, Thomas Fischer, MD, of Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg (Germany), highlighted three don’t-miss sessions.

In an analysis of a large cohort of FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients in the RATIFY trial, researchers looked at the prognostic impact of ITD insertion site.

“Interestingly, in this large cohort of 452 FLT3-ITD mutated AML, the negative prognostic impact of beta1-sheet insertion site of FLT3-ITD could be confirmed,” Dr. Fischer said. “Further analysis of a potential predictive effect on outcome of midostaurin treatment is ongoing and will be very interesting.”

The findings will be presented at 5 p.m. PT on Sunday, Dec. 2 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 435).

Another notable presentation features results from the phase 2 RADIUS trial, a randomized study comparing standard of care, with and without midostaurin, after allogeneic stem cell transplant in FLT3-ITD–mutated AML.

“Here, efficacy and toxicity of midostaurin was investigated in a [minimal residual disease] situation post-alloSCT,” Dr. Fischer said. “Interestingly, adding midostaurin to standard of care reduced the risk of relapse at 18 months post-alloSCT by 46%.”

The complete findings will be presented at 10:45 a.m. PT on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 662).

Dr. Fischer singled out another study looking at the efficacy and safety of single-agent quizartinib in patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML. In this large, randomized trial the researchers noted a significant improvement in CR rates and survival benefit with the single agent FLT3 inhibitors, compared with salvage chemotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory mutated AML.

The findings will be presented at 8 a.m. on Monday, Dec. 3 in Seaport Ballroom F at the Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego (Abstract 563).

Notable posters

Iberia Romina Sosa, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, suggested several posters worth visiting in the areas of thrombosis and bleeding.

Poster 1134 looks at the TNF-alpha driven inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the platelet hyperreactivity of aging and MPN.

How do you know if your therapy for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is working? Poster 3736 examines the measurement of cell-derived microparticles as a possible tool to monitor response to therapy.

You don’t have to be taking aspirin to have a bleeding profile characteristic with consumption of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor. Poster 1156 provides a first report of a platelet function disorder caused by autosomal recessive inheritance of PTGS1.

Poster 2477 takes a closer look at fitusiran, an antithrombin inhibitor, which improves thrombin generation in patients with hemophilia A or B. Protocol amendments for safety monitoring move fitusiran to phase 3 trials, Dr. Sosa said.

Stroke, arterial dissection events reported with Lemtrada, FDA says

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.

Symptoms include sudden onset of the following: severe headache or neck pain; numbness or weakness in the arms or legs, especially on only one side of the body; confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech; vision problems in one or both eyes; and dizziness, loss of balance, or difficulty walking.

As a result of the reports, the FDA has updated the drug label prescribing information and the patient Medication Guide to reflect these risks, and added the risk of stroke to the medication’s existing boxed warning.

Health care providers should remind patients of the potential for stroke and arterial dissection at each treatment visit and advise them to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any of the symptoms reported in previous cases. “The diagnosis is often complicated because early symptoms such as headache and neck pain are not specific,” according to the agency, but patients complaining of such symptoms should be evaluated immediately.

Alemtuzumab was also approved in May 2001 for treating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) under the brand name Campath. The FDA will update the Campath label to reflect the new warnings and risks.

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.

Symptoms include sudden onset of the following: severe headache or neck pain; numbness or weakness in the arms or legs, especially on only one side of the body; confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech; vision problems in one or both eyes; and dizziness, loss of balance, or difficulty walking.

As a result of the reports, the FDA has updated the drug label prescribing information and the patient Medication Guide to reflect these risks, and added the risk of stroke to the medication’s existing boxed warning.

Health care providers should remind patients of the potential for stroke and arterial dissection at each treatment visit and advise them to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any of the symptoms reported in previous cases. “The diagnosis is often complicated because early symptoms such as headache and neck pain are not specific,” according to the agency, but patients complaining of such symptoms should be evaluated immediately.

Alemtuzumab was also approved in May 2001 for treating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) under the brand name Campath. The FDA will update the Campath label to reflect the new warnings and risks.

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.

Symptoms include sudden onset of the following: severe headache or neck pain; numbness or weakness in the arms or legs, especially on only one side of the body; confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech; vision problems in one or both eyes; and dizziness, loss of balance, or difficulty walking.

As a result of the reports, the FDA has updated the drug label prescribing information and the patient Medication Guide to reflect these risks, and added the risk of stroke to the medication’s existing boxed warning.

Health care providers should remind patients of the potential for stroke and arterial dissection at each treatment visit and advise them to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any of the symptoms reported in previous cases. “The diagnosis is often complicated because early symptoms such as headache and neck pain are not specific,” according to the agency, but patients complaining of such symptoms should be evaluated immediately.

Alemtuzumab was also approved in May 2001 for treating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) under the brand name Campath. The FDA will update the Campath label to reflect the new warnings and risks.

Feds call for EHR interoperability. Again.

WASHINGTON – In what feels like a tradition, the need to solve interoperability issues was front and center once again as the key goal presented by Health and Human Services officials at the annual meeting of the Office of the National Coordinator.

“It is actually impossible to move to a future health system, the one that we need ... without a truly interoperable system,” HHS Deputy Secretary Eric Hargan said Nov. 29 during a keynote address.

“Patients need to be able to access their own records. Period,” he added.

Mr. Hargan emphasized that the HHS will define what it wants to see regarding interoperability, but leave it up to vendors and developers to come up with solutions on how this will be accomplished.

One example that he mentioned is Blue Button 2.0, a part of the MyHealthEData initiative, which allows Medicare patients to connect their claims data to apps to help them make informed decisions about their care.

“The use of apps here reflects to potential, we believe, for patient-centered technology to improve health,” Mr. Hargan said.

He also noted that the agency is looking at how existing law and regulation – such as the antikickback statute, the Stark law, HIPAA, and federal privacy regulations – might be hindering the transition to value-based care.

This analysis is “specifically focused on understanding as quickly as we can ... how current interpretations of these laws may be impeding value-based transformation and coordinated care,” Mr. Hargan said.

ONC is also taking a look at reducing provider burden, issuing a draft strategy for comment that specifically targets provider burden related to the use of EHRs and offer up a series of recommendations to help address it.

WASHINGTON – In what feels like a tradition, the need to solve interoperability issues was front and center once again as the key goal presented by Health and Human Services officials at the annual meeting of the Office of the National Coordinator.

“It is actually impossible to move to a future health system, the one that we need ... without a truly interoperable system,” HHS Deputy Secretary Eric Hargan said Nov. 29 during a keynote address.

“Patients need to be able to access their own records. Period,” he added.

Mr. Hargan emphasized that the HHS will define what it wants to see regarding interoperability, but leave it up to vendors and developers to come up with solutions on how this will be accomplished.

One example that he mentioned is Blue Button 2.0, a part of the MyHealthEData initiative, which allows Medicare patients to connect their claims data to apps to help them make informed decisions about their care.

“The use of apps here reflects to potential, we believe, for patient-centered technology to improve health,” Mr. Hargan said.

He also noted that the agency is looking at how existing law and regulation – such as the antikickback statute, the Stark law, HIPAA, and federal privacy regulations – might be hindering the transition to value-based care.

This analysis is “specifically focused on understanding as quickly as we can ... how current interpretations of these laws may be impeding value-based transformation and coordinated care,” Mr. Hargan said.

ONC is also taking a look at reducing provider burden, issuing a draft strategy for comment that specifically targets provider burden related to the use of EHRs and offer up a series of recommendations to help address it.

WASHINGTON – In what feels like a tradition, the need to solve interoperability issues was front and center once again as the key goal presented by Health and Human Services officials at the annual meeting of the Office of the National Coordinator.

“It is actually impossible to move to a future health system, the one that we need ... without a truly interoperable system,” HHS Deputy Secretary Eric Hargan said Nov. 29 during a keynote address.

“Patients need to be able to access their own records. Period,” he added.

Mr. Hargan emphasized that the HHS will define what it wants to see regarding interoperability, but leave it up to vendors and developers to come up with solutions on how this will be accomplished.

One example that he mentioned is Blue Button 2.0, a part of the MyHealthEData initiative, which allows Medicare patients to connect their claims data to apps to help them make informed decisions about their care.

“The use of apps here reflects to potential, we believe, for patient-centered technology to improve health,” Mr. Hargan said.

He also noted that the agency is looking at how existing law and regulation – such as the antikickback statute, the Stark law, HIPAA, and federal privacy regulations – might be hindering the transition to value-based care.

This analysis is “specifically focused on understanding as quickly as we can ... how current interpretations of these laws may be impeding value-based transformation and coordinated care,” Mr. Hargan said.

ONC is also taking a look at reducing provider burden, issuing a draft strategy for comment that specifically targets provider burden related to the use of EHRs and offer up a series of recommendations to help address it.

REPORTING FROM ONC 2018

Death row executions raise questions about competence

AUSTIN, TEX. – More than one-quarter of inmates executed during a recent 7-year period had a history confirming or suggesting they had a mental illness that might have called their competence for execution into question, according to new research.

Capital punishment remains legal in 31 U.S. states. In Ford v. Wainwright, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1986 that executing a person lacking competence violates the Eighth Amendment, yet many people with a history of mental illness have been executed, said Paulina Riess, MD, of the BronxCare Health System in New York, and her colleagues.

The question of appropriately determining whether someone is competent enough to be executed also is controversial, Dr. Riess and her colleagues noted in their research abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. “The decision of whether one is competent ultimately falls into the hands of a forensic evaluator whose opinion should represent a clear and detailed explanation of a prison’s understanding, awareness, and comprehension of the pending execution.”

They also collected data on inmates’ age, race, instant offense, method of execution, and years spent on death row.

When the authors searched the literature for an evidence-based tool to provide “information regarding any history of mental illness pertaining to executed prisoners,” they found none and therefore relied on media coverage for their data on history of mental illness or disability or psychotropic medication treatment.

They found that 26% had a history of psychiatric illness, mental disability, or treatment with psychiatric medications.

Among 273 people executed from 2010-2017, all but 5 were men. Texas had the most executions at 80, followed by Florida (27), Georgia (23), Ohio (22), Oklahoma (21), and Alabama (17). Other states in the analysis included Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia.

Five of the inmates were aged older than 70 years, and seven were under 30 years old. Most were aged 31-40 years (73 inmates) or 40-50 years (108 inmates). The racial breakdown was 147 whites, 90 blacks, 35 Hispanics, and 1 Native American.

Lethal injection was the method of execution for all – except one who died by firing squad and two who died by electrocution. Seven inmates had been convicted for mass murder or serial killing (one of whom also had a robbery conviction). The others all had homicide convictions, 61 of whom had at least one other conviction in addition to homicide – predominantly robbery or rape.

Of those with information available, 117 inmates spent 11-20 years on death row, 64 spent 21-30 years, and 15 spent 31-40 years. Only five inmates spent fewer than 5 years on death row, and 49 inmates spent 5-10 years.

The need to rely on media reports for data collection is a limitation of the study. “While gathering demographic information, team members unanimously reported a history of trauma in a large portion of those executed during the 7-year span examined,” the authors reported. “This is another limitation as trauma history could have been included as a separate variable.”

No disclosures were reported.

AUSTIN, TEX. – More than one-quarter of inmates executed during a recent 7-year period had a history confirming or suggesting they had a mental illness that might have called their competence for execution into question, according to new research.

Capital punishment remains legal in 31 U.S. states. In Ford v. Wainwright, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1986 that executing a person lacking competence violates the Eighth Amendment, yet many people with a history of mental illness have been executed, said Paulina Riess, MD, of the BronxCare Health System in New York, and her colleagues.

The question of appropriately determining whether someone is competent enough to be executed also is controversial, Dr. Riess and her colleagues noted in their research abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. “The decision of whether one is competent ultimately falls into the hands of a forensic evaluator whose opinion should represent a clear and detailed explanation of a prison’s understanding, awareness, and comprehension of the pending execution.”

They also collected data on inmates’ age, race, instant offense, method of execution, and years spent on death row.

When the authors searched the literature for an evidence-based tool to provide “information regarding any history of mental illness pertaining to executed prisoners,” they found none and therefore relied on media coverage for their data on history of mental illness or disability or psychotropic medication treatment.

They found that 26% had a history of psychiatric illness, mental disability, or treatment with psychiatric medications.

Among 273 people executed from 2010-2017, all but 5 were men. Texas had the most executions at 80, followed by Florida (27), Georgia (23), Ohio (22), Oklahoma (21), and Alabama (17). Other states in the analysis included Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia.

Five of the inmates were aged older than 70 years, and seven were under 30 years old. Most were aged 31-40 years (73 inmates) or 40-50 years (108 inmates). The racial breakdown was 147 whites, 90 blacks, 35 Hispanics, and 1 Native American.

Lethal injection was the method of execution for all – except one who died by firing squad and two who died by electrocution. Seven inmates had been convicted for mass murder or serial killing (one of whom also had a robbery conviction). The others all had homicide convictions, 61 of whom had at least one other conviction in addition to homicide – predominantly robbery or rape.

Of those with information available, 117 inmates spent 11-20 years on death row, 64 spent 21-30 years, and 15 spent 31-40 years. Only five inmates spent fewer than 5 years on death row, and 49 inmates spent 5-10 years.

The need to rely on media reports for data collection is a limitation of the study. “While gathering demographic information, team members unanimously reported a history of trauma in a large portion of those executed during the 7-year span examined,” the authors reported. “This is another limitation as trauma history could have been included as a separate variable.”

No disclosures were reported.

AUSTIN, TEX. – More than one-quarter of inmates executed during a recent 7-year period had a history confirming or suggesting they had a mental illness that might have called their competence for execution into question, according to new research.

Capital punishment remains legal in 31 U.S. states. In Ford v. Wainwright, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1986 that executing a person lacking competence violates the Eighth Amendment, yet many people with a history of mental illness have been executed, said Paulina Riess, MD, of the BronxCare Health System in New York, and her colleagues.

The question of appropriately determining whether someone is competent enough to be executed also is controversial, Dr. Riess and her colleagues noted in their research abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. “The decision of whether one is competent ultimately falls into the hands of a forensic evaluator whose opinion should represent a clear and detailed explanation of a prison’s understanding, awareness, and comprehension of the pending execution.”

They also collected data on inmates’ age, race, instant offense, method of execution, and years spent on death row.

When the authors searched the literature for an evidence-based tool to provide “information regarding any history of mental illness pertaining to executed prisoners,” they found none and therefore relied on media coverage for their data on history of mental illness or disability or psychotropic medication treatment.

They found that 26% had a history of psychiatric illness, mental disability, or treatment with psychiatric medications.

Among 273 people executed from 2010-2017, all but 5 were men. Texas had the most executions at 80, followed by Florida (27), Georgia (23), Ohio (22), Oklahoma (21), and Alabama (17). Other states in the analysis included Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia.

Five of the inmates were aged older than 70 years, and seven were under 30 years old. Most were aged 31-40 years (73 inmates) or 40-50 years (108 inmates). The racial breakdown was 147 whites, 90 blacks, 35 Hispanics, and 1 Native American.

Lethal injection was the method of execution for all – except one who died by firing squad and two who died by electrocution. Seven inmates had been convicted for mass murder or serial killing (one of whom also had a robbery conviction). The others all had homicide convictions, 61 of whom had at least one other conviction in addition to homicide – predominantly robbery or rape.

Of those with information available, 117 inmates spent 11-20 years on death row, 64 spent 21-30 years, and 15 spent 31-40 years. Only five inmates spent fewer than 5 years on death row, and 49 inmates spent 5-10 years.

The need to rely on media reports for data collection is a limitation of the study. “While gathering demographic information, team members unanimously reported a history of trauma in a large portion of those executed during the 7-year span examined,” the authors reported. “This is another limitation as trauma history could have been included as a separate variable.”

No disclosures were reported.

REPORTING FROM THE AAPL ANNUAL MEETING

AHA jewels, readmissions not best at ‘Best Hospitals,’ and more

and study findings challenge cholesterol guidelines for patients with type 1 diabetes. Also, we take a closer look at how smoke-free policies affect blood pressure, and how magazine-ranked “Best Hospitals” actually perform.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

and study findings challenge cholesterol guidelines for patients with type 1 diabetes. Also, we take a closer look at how smoke-free policies affect blood pressure, and how magazine-ranked “Best Hospitals” actually perform.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

and study findings challenge cholesterol guidelines for patients with type 1 diabetes. Also, we take a closer look at how smoke-free policies affect blood pressure, and how magazine-ranked “Best Hospitals” actually perform.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in U.S.

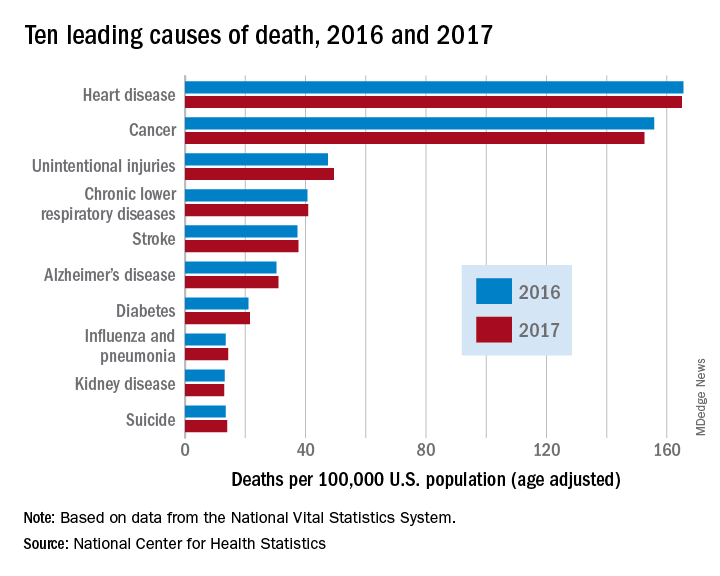

The 10 leading causes of death in the United States remained unchanged over the past year, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Though life expectancy at birth decreased to 78.6 years in 2017, down from 78.7 years in 2016, that change was driven primarily by suicide and drug overdose.

However, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, at 165 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2017. This represents a slight, statistically nonsignificant, decrease from the 165.5 deaths per 100,000 caused by heart disease in the previous year.

Other diseases related to cardiometabolic health saw increases. Stroke and diabetes each caused a small but significant increase in deaths in 2017, which saw a 1-year increase to 37.6 from 37.3 stroke deaths per 100,000 people. Diabetes deaths increased to 21.5 from 21 per 100,000 the previous year. Stroke was the fifth and diabetes the seventh most common cause of death, according to the data brief published by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Alzheimer’s disease deaths also increased significantly, from 30.3 per 100,000 in 2016 to 31 per 100,000 in 2017. Although Alzheimer’s exact etiology remains under study, cardiovascular disease factors and Alzheimer’s disease share many risk factors and are often comorbid .

“With a slight decrease in deaths from heart disease in 2017 and a slight increase in deaths from stroke, this lack of any major movement in these areas has been a trend we’ve seen the last couple of years,” said Ivor Benjamin, MD, president of the American Heart Association, in a press release. “It is discouraging after experiencing decades when heart disease and stroke death rates both dropped more dramatically.”

Infant deaths from congenital malformations decreased from 2016 to 2017, from 122.1 to 118.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. “While the report doesn’t specify death rates for specific types of congenital malformations, this is heartening news as it could reflect fewer deaths from congenital heart defects,” said the AHA in its release.

According to the CDC, the 10 leading causes of death together account for about three quarters of United States deaths. Cancer caused nearly as many deaths as heart disease – 152.5 per 100,000. This represented a significant decrease from the 155.8 cancer deaths per 100,000 seen in 2016. The remaining top 10 causes of death, in decreasing order, were unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide.

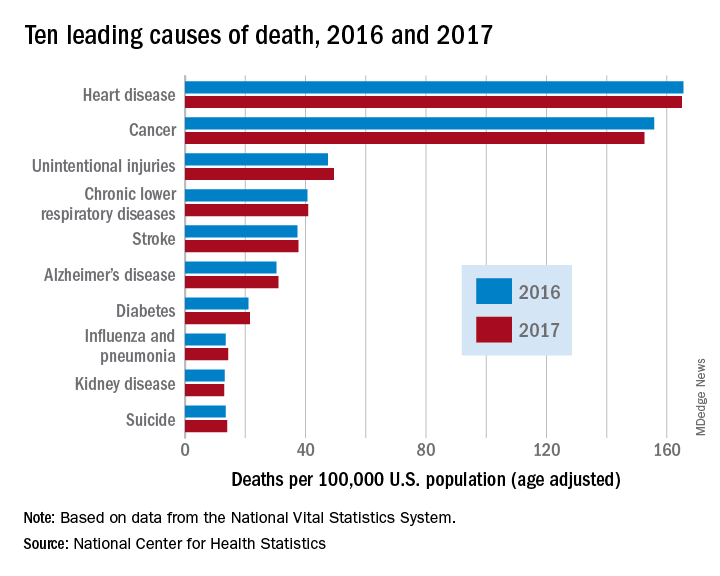

The 10 leading causes of death in the United States remained unchanged over the past year, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Though life expectancy at birth decreased to 78.6 years in 2017, down from 78.7 years in 2016, that change was driven primarily by suicide and drug overdose.

However, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, at 165 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2017. This represents a slight, statistically nonsignificant, decrease from the 165.5 deaths per 100,000 caused by heart disease in the previous year.

Other diseases related to cardiometabolic health saw increases. Stroke and diabetes each caused a small but significant increase in deaths in 2017, which saw a 1-year increase to 37.6 from 37.3 stroke deaths per 100,000 people. Diabetes deaths increased to 21.5 from 21 per 100,000 the previous year. Stroke was the fifth and diabetes the seventh most common cause of death, according to the data brief published by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Alzheimer’s disease deaths also increased significantly, from 30.3 per 100,000 in 2016 to 31 per 100,000 in 2017. Although Alzheimer’s exact etiology remains under study, cardiovascular disease factors and Alzheimer’s disease share many risk factors and are often comorbid .

“With a slight decrease in deaths from heart disease in 2017 and a slight increase in deaths from stroke, this lack of any major movement in these areas has been a trend we’ve seen the last couple of years,” said Ivor Benjamin, MD, president of the American Heart Association, in a press release. “It is discouraging after experiencing decades when heart disease and stroke death rates both dropped more dramatically.”

Infant deaths from congenital malformations decreased from 2016 to 2017, from 122.1 to 118.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. “While the report doesn’t specify death rates for specific types of congenital malformations, this is heartening news as it could reflect fewer deaths from congenital heart defects,” said the AHA in its release.

According to the CDC, the 10 leading causes of death together account for about three quarters of United States deaths. Cancer caused nearly as many deaths as heart disease – 152.5 per 100,000. This represented a significant decrease from the 155.8 cancer deaths per 100,000 seen in 2016. The remaining top 10 causes of death, in decreasing order, were unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide.

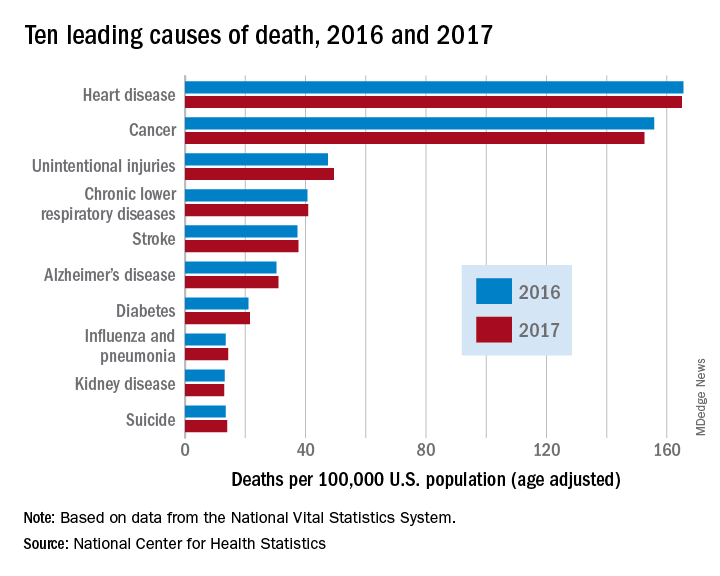

The 10 leading causes of death in the United States remained unchanged over the past year, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Though life expectancy at birth decreased to 78.6 years in 2017, down from 78.7 years in 2016, that change was driven primarily by suicide and drug overdose.

However, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, at 165 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2017. This represents a slight, statistically nonsignificant, decrease from the 165.5 deaths per 100,000 caused by heart disease in the previous year.

Other diseases related to cardiometabolic health saw increases. Stroke and diabetes each caused a small but significant increase in deaths in 2017, which saw a 1-year increase to 37.6 from 37.3 stroke deaths per 100,000 people. Diabetes deaths increased to 21.5 from 21 per 100,000 the previous year. Stroke was the fifth and diabetes the seventh most common cause of death, according to the data brief published by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Alzheimer’s disease deaths also increased significantly, from 30.3 per 100,000 in 2016 to 31 per 100,000 in 2017. Although Alzheimer’s exact etiology remains under study, cardiovascular disease factors and Alzheimer’s disease share many risk factors and are often comorbid .

“With a slight decrease in deaths from heart disease in 2017 and a slight increase in deaths from stroke, this lack of any major movement in these areas has been a trend we’ve seen the last couple of years,” said Ivor Benjamin, MD, president of the American Heart Association, in a press release. “It is discouraging after experiencing decades when heart disease and stroke death rates both dropped more dramatically.”

Infant deaths from congenital malformations decreased from 2016 to 2017, from 122.1 to 118.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. “While the report doesn’t specify death rates for specific types of congenital malformations, this is heartening news as it could reflect fewer deaths from congenital heart defects,” said the AHA in its release.

According to the CDC, the 10 leading causes of death together account for about three quarters of United States deaths. Cancer caused nearly as many deaths as heart disease – 152.5 per 100,000. This represented a significant decrease from the 155.8 cancer deaths per 100,000 seen in 2016. The remaining top 10 causes of death, in decreasing order, were unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide.

FROM A CDC DATA BRIEF

Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

In the year prior to HIV diagnosis, there were high rates of missed opportunities for HIV testing and sexual history documentation, according to a retrospective study of youth with HIV aged 14-26 years who were treated at an HIV clinic. These results demonstrate a failed need for routine HIV screening and counseling in adolescents, according to Nellie Riendeau Lazar, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

The researchers retrospectively identified 301 subjects between January 2009 and April 2015 who met their study criteria. A total of 58 of these (19%) had at least one visit in the care network in the year prior to diagnosis and their entry into the adolescent HIV clinic, and they were analyzed for missed diagnosis. The adolescent HIV clinic is part of a large care network in the Philadelphia area that includes a pediatric emergency department and a tertiary care hospital. At the time of the study, there were 31 primary care sites, according to the authors.

The mean age of the subjects in the study was 17. The majority (80%) were young men, African-American (93%), and men who have sex with men (81%). There were no significant differences seen in demographics between those with and without prior visits in the health system (J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802).

The 58 subjects were seen in 179 health care visits in the year prior to their diagnosis: 56% outpatient, 40% emergency department, and 4% inpatient visits. Only 59% of these visits had any documentation of sexual history and “the overwhelming majority of those noting sexual activity included no other information,” such as number of partners, sex of partners, or condom use, according to the researchers.

Among the total cohort, 183 of 301 had never had an HIV test prior to their first positive test, even though 26% had been seen in the care network in the 3 years prior to their diagnosis. Among the 58 in the missed opportunity analysis, only 48% had HIV testing, even though 88% (51) had documented symptoms in their visits that could have been consistent with acute infection.

“Our findings support the most recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), recommending routine HIV screening for all adolescents, regardless of risk,” the researchers stated. “Adolescents may not always disclose sexual activity during routine assessment, and provider level barriers limit the reach of risk-based testing algorithms,” they added.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lazar NR et al. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802.

In the year prior to HIV diagnosis, there were high rates of missed opportunities for HIV testing and sexual history documentation, according to a retrospective study of youth with HIV aged 14-26 years who were treated at an HIV clinic. These results demonstrate a failed need for routine HIV screening and counseling in adolescents, according to Nellie Riendeau Lazar, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

The researchers retrospectively identified 301 subjects between January 2009 and April 2015 who met their study criteria. A total of 58 of these (19%) had at least one visit in the care network in the year prior to diagnosis and their entry into the adolescent HIV clinic, and they were analyzed for missed diagnosis. The adolescent HIV clinic is part of a large care network in the Philadelphia area that includes a pediatric emergency department and a tertiary care hospital. At the time of the study, there were 31 primary care sites, according to the authors.

The mean age of the subjects in the study was 17. The majority (80%) were young men, African-American (93%), and men who have sex with men (81%). There were no significant differences seen in demographics between those with and without prior visits in the health system (J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802).

The 58 subjects were seen in 179 health care visits in the year prior to their diagnosis: 56% outpatient, 40% emergency department, and 4% inpatient visits. Only 59% of these visits had any documentation of sexual history and “the overwhelming majority of those noting sexual activity included no other information,” such as number of partners, sex of partners, or condom use, according to the researchers.

Among the total cohort, 183 of 301 had never had an HIV test prior to their first positive test, even though 26% had been seen in the care network in the 3 years prior to their diagnosis. Among the 58 in the missed opportunity analysis, only 48% had HIV testing, even though 88% (51) had documented symptoms in their visits that could have been consistent with acute infection.

“Our findings support the most recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), recommending routine HIV screening for all adolescents, regardless of risk,” the researchers stated. “Adolescents may not always disclose sexual activity during routine assessment, and provider level barriers limit the reach of risk-based testing algorithms,” they added.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lazar NR et al. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802.

In the year prior to HIV diagnosis, there were high rates of missed opportunities for HIV testing and sexual history documentation, according to a retrospective study of youth with HIV aged 14-26 years who were treated at an HIV clinic. These results demonstrate a failed need for routine HIV screening and counseling in adolescents, according to Nellie Riendeau Lazar, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

The researchers retrospectively identified 301 subjects between January 2009 and April 2015 who met their study criteria. A total of 58 of these (19%) had at least one visit in the care network in the year prior to diagnosis and their entry into the adolescent HIV clinic, and they were analyzed for missed diagnosis. The adolescent HIV clinic is part of a large care network in the Philadelphia area that includes a pediatric emergency department and a tertiary care hospital. At the time of the study, there were 31 primary care sites, according to the authors.

The mean age of the subjects in the study was 17. The majority (80%) were young men, African-American (93%), and men who have sex with men (81%). There were no significant differences seen in demographics between those with and without prior visits in the health system (J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802).

The 58 subjects were seen in 179 health care visits in the year prior to their diagnosis: 56% outpatient, 40% emergency department, and 4% inpatient visits. Only 59% of these visits had any documentation of sexual history and “the overwhelming majority of those noting sexual activity included no other information,” such as number of partners, sex of partners, or condom use, according to the researchers.

Among the total cohort, 183 of 301 had never had an HIV test prior to their first positive test, even though 26% had been seen in the care network in the 3 years prior to their diagnosis. Among the 58 in the missed opportunity analysis, only 48% had HIV testing, even though 88% (51) had documented symptoms in their visits that could have been consistent with acute infection.

“Our findings support the most recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), recommending routine HIV screening for all adolescents, regardless of risk,” the researchers stated. “Adolescents may not always disclose sexual activity during routine assessment, and provider level barriers limit the reach of risk-based testing algorithms,” they added.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lazar NR et al. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Key clinical point: Only 51% of youth with symptoms suggesting acute retroviral syndrome were tested.

Major finding: HIV testing was performed in only 48% of the subjects seen in the year prior to their diagnosis.

Study details: Retrospective review of subjects with HIV aged 14-26 years, comparing those with and without HIV screening within the year prior to diagnosis.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lazar NR et al. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:799-802.

Open enrollment: Weekly volume down again

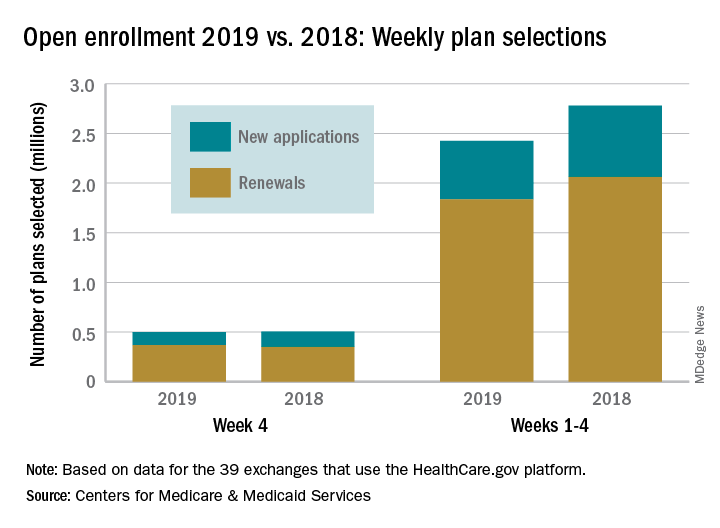

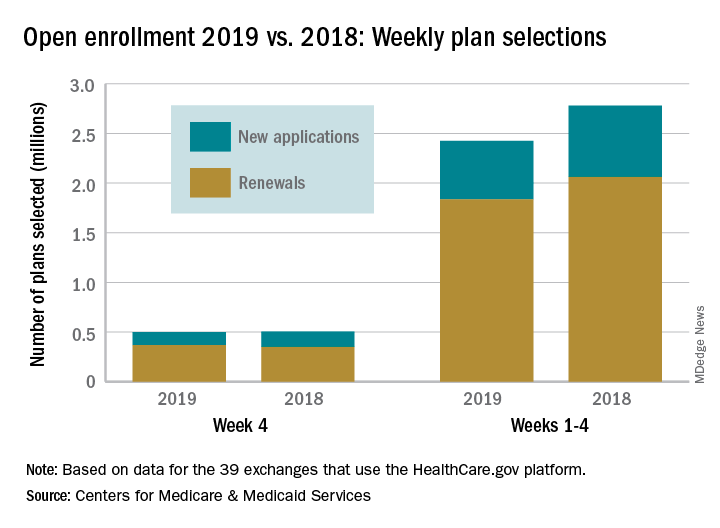

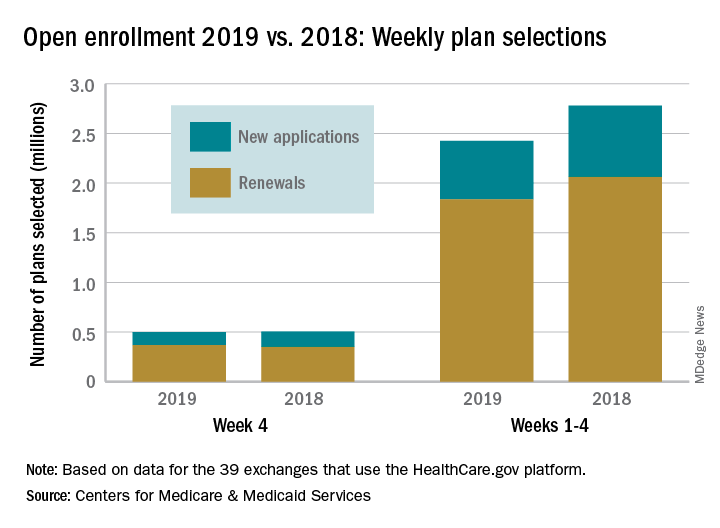

Plan selections at HealthCare.gov fell for the second week in a row as overall volume for open enrollment 2019 continues to lag behind last year, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Just over 500,000 plans – 369,000 renewals and 131,000 new applications – were selected during week 4 (Nov. 18-24) for the 2019 coverage year in the 39 states that use the HealthCare.gov platform, which is down from 748,000 for week 3 and 805,000 for week 2. A similar pattern of decreases in weeks 3 and 4 was seen during last year’s open-enrollment period.

For the entire open enrollment so far this year, a little over 2.42 million plans have been selected, which is down by 12.8% from last year’s 4-week total of 2.78 million selections, the CMS data show.

Plan selections at HealthCare.gov fell for the second week in a row as overall volume for open enrollment 2019 continues to lag behind last year, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Just over 500,000 plans – 369,000 renewals and 131,000 new applications – were selected during week 4 (Nov. 18-24) for the 2019 coverage year in the 39 states that use the HealthCare.gov platform, which is down from 748,000 for week 3 and 805,000 for week 2. A similar pattern of decreases in weeks 3 and 4 was seen during last year’s open-enrollment period.

For the entire open enrollment so far this year, a little over 2.42 million plans have been selected, which is down by 12.8% from last year’s 4-week total of 2.78 million selections, the CMS data show.

Plan selections at HealthCare.gov fell for the second week in a row as overall volume for open enrollment 2019 continues to lag behind last year, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Just over 500,000 plans – 369,000 renewals and 131,000 new applications – were selected during week 4 (Nov. 18-24) for the 2019 coverage year in the 39 states that use the HealthCare.gov platform, which is down from 748,000 for week 3 and 805,000 for week 2. A similar pattern of decreases in weeks 3 and 4 was seen during last year’s open-enrollment period.

For the entire open enrollment so far this year, a little over 2.42 million plans have been selected, which is down by 12.8% from last year’s 4-week total of 2.78 million selections, the CMS data show.

Weight loss cuts risk of psoriatic arthritis

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese psoriasis patients have it within their power to reduce their risk of developing psoriatic arthritis through weight loss, according to a large British longitudinal study.

Of the three modifiable lifestyle factors evaluated in the study as potential risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients – body mass index, smoking, and alcohol intake – reduction in BMI over time was clearly the winning strategy, Neil McHugh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The message from this study of 90,189 incident cases of psoriasis identified in the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink was unequivocal: “If you’re overweight and have psoriasis and you lose weight, you reduce your chance of developing a nasty form of arthritis,” said Dr. McHugh, professor of pharmacoepidemiology and a rheumatologist at the University of Bath, England.

“As psoriatic arthritis affects around 20% of people with psoriasis, weight reduction amongst those who are obese may have the potential to greatly reduce their risk of psoriatic arthritis in addition to providing additional health benefits,” he added.

Among the more than 90,000 patients diagnosed with psoriasis, 1,409 subsequently developed psoriatic arthritis, with an overall incidence rate of 2.72 cases per 1,000 person-years. Baseline BMI was strongly associated in stepwise fashion with subsequent psoriatic arthritis. Psoriasis patients with a baseline BMI of 25-29.9 kg/m2 were at an adjusted 1.76-fold increased risk of later developing psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis patients having a BMI of less than 25. For those with a BMI of 30-34.9 kg/m2, the risk of subsequent psoriatic arthritis was increased 2.04-fold. And for those with a baseline BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, the risk was increased 2.42-fold in analyses adjusted for age, sex, psoriasis duration and severity, history of trauma, and diabetes.

In contrast, the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis wasn’t significantly different between psoriasis patients who were nonsmokers, ex-smokers, or current smokers. And while there was a significantly increased risk of developing psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients who were current drinkers, compared with nondrinkers, the risk in ex-drinkers and heavy drinkers was similar to that in nondrinkers, a counterintuitive finding Dr. McHugh suspects was a distortion due to small numbers.

While the observed relationship between baseline BMI and subsequent risk of psoriatic arthritis was informative, it only tells part of the story, since body weight so often changes over time. Dr. McHugh and his coinvestigators had data on change in BMI over the course of 10 years of follow-up in 15,627 psoriasis patients free of psoriatic arthritis at the time their psoriasis was diagnosed. The researchers developed a BMI risk calculator that expressed the effect of change in BMI over time on the cumulative risk of developing psoriatic arthritis.

“We were able to show that if, for instance, you started with a BMI of 25 at baseline and ended up with a BMI of 30, your risk of psoriatic arthritis goes up by 13%, whereas if you start at 30 and come down to 25, your risk decreases by 13%. And the more weight you lose, the greater you reduce your risk of developing psoriatic arthritis,” the rheumatologist explained in an interview.

Indeed, with more extreme changes in BMI over the course of a decade following diagnosis of psoriasis – for example, dropping from a baseline BMI of 36 kg/m2 to 23 kg/m2 – the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis fell by close to 30%.

Dr. McHugh reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research.

SOURCE: Green A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 2134.

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese psoriasis patients have it within their power to reduce their risk of developing psoriatic arthritis through weight loss, according to a large British longitudinal study.

Of the three modifiable lifestyle factors evaluated in the study as potential risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients – body mass index, smoking, and alcohol intake – reduction in BMI over time was clearly the winning strategy, Neil McHugh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The message from this study of 90,189 incident cases of psoriasis identified in the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink was unequivocal: “If you’re overweight and have psoriasis and you lose weight, you reduce your chance of developing a nasty form of arthritis,” said Dr. McHugh, professor of pharmacoepidemiology and a rheumatologist at the University of Bath, England.

“As psoriatic arthritis affects around 20% of people with psoriasis, weight reduction amongst those who are obese may have the potential to greatly reduce their risk of psoriatic arthritis in addition to providing additional health benefits,” he added.

Among the more than 90,000 patients diagnosed with psoriasis, 1,409 subsequently developed psoriatic arthritis, with an overall incidence rate of 2.72 cases per 1,000 person-years. Baseline BMI was strongly associated in stepwise fashion with subsequent psoriatic arthritis. Psoriasis patients with a baseline BMI of 25-29.9 kg/m2 were at an adjusted 1.76-fold increased risk of later developing psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis patients having a BMI of less than 25. For those with a BMI of 30-34.9 kg/m2, the risk of subsequent psoriatic arthritis was increased 2.04-fold. And for those with a baseline BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, the risk was increased 2.42-fold in analyses adjusted for age, sex, psoriasis duration and severity, history of trauma, and diabetes.

In contrast, the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis wasn’t significantly different between psoriasis patients who were nonsmokers, ex-smokers, or current smokers. And while there was a significantly increased risk of developing psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients who were current drinkers, compared with nondrinkers, the risk in ex-drinkers and heavy drinkers was similar to that in nondrinkers, a counterintuitive finding Dr. McHugh suspects was a distortion due to small numbers.

While the observed relationship between baseline BMI and subsequent risk of psoriatic arthritis was informative, it only tells part of the story, since body weight so often changes over time. Dr. McHugh and his coinvestigators had data on change in BMI over the course of 10 years of follow-up in 15,627 psoriasis patients free of psoriatic arthritis at the time their psoriasis was diagnosed. The researchers developed a BMI risk calculator that expressed the effect of change in BMI over time on the cumulative risk of developing psoriatic arthritis.

“We were able to show that if, for instance, you started with a BMI of 25 at baseline and ended up with a BMI of 30, your risk of psoriatic arthritis goes up by 13%, whereas if you start at 30 and come down to 25, your risk decreases by 13%. And the more weight you lose, the greater you reduce your risk of developing psoriatic arthritis,” the rheumatologist explained in an interview.

Indeed, with more extreme changes in BMI over the course of a decade following diagnosis of psoriasis – for example, dropping from a baseline BMI of 36 kg/m2 to 23 kg/m2 – the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis fell by close to 30%.

Dr. McHugh reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research.

SOURCE: Green A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 2134.

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese psoriasis patients have it within their power to reduce their risk of developing psoriatic arthritis through weight loss, according to a large British longitudinal study.

Of the three modifiable lifestyle factors evaluated in the study as potential risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients – body mass index, smoking, and alcohol intake – reduction in BMI over time was clearly the winning strategy, Neil McHugh, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.