User login

ICYMI: Elotuzumab reduces progression risk in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma

Patients with multiple myeloma who did not respond to treatment with lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor had a significantly lower risk of progression or death when receiving elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone, compared with pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone (hazard ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.86; P = .008), according to results of a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805762.

Study results of ELOQUENT-3 were presented earlier this year at the Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association.

Patients with multiple myeloma who did not respond to treatment with lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor had a significantly lower risk of progression or death when receiving elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone, compared with pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone (hazard ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.86; P = .008), according to results of a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805762.

Study results of ELOQUENT-3 were presented earlier this year at the Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association.

Patients with multiple myeloma who did not respond to treatment with lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor had a significantly lower risk of progression or death when receiving elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone, compared with pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone (hazard ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.86; P = .008), according to results of a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine 2018 Nov 7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805762.

Study results of ELOQUENT-3 were presented earlier this year at the Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Can biomarkers detect concussions? It’s complicated

A series of three studies in college students showed that some serum markers are associated with concussion but the background level of the markers can vary considerably. There was no association between the markers and history of concussion, and they markers varied significantly by sex and race.

The work, published in Neurology, suggests that there is hope for finding biomarkers for concussion, but much more work needs to be done.

Serum levels of amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), total tau, and S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B) were associated with concussion, especially when tests were performed within 4 hours of the injury. However, the varying background levels indicate that these biomarkers are not yet ready for clinical application.

All three studies looked at serum levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), and 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNPase).

In the first study, researchers recruited 415 college athletes without a concussion (61% male, 40% white). The researchers took measurements outside of the athletes’ competitive sports season to maximize the odds that the levels would represent a true baseline. The median time between blood draw and the last risk of head impact was 80 days (mean, 98.4 days; interquartile range, 38-204 days).

Males had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.75; P less than .001) and S100B (Cohen d = 0.56; P less than .001), while females had higher levels of CNPase (Cohen d = 0.43; P less than .001). White subjects had higher levels of Abeta42 (Cohen d = .28; P = .005) and CNPase (Cohen d = 0.46; P less than .001). Black subjects had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.61; P less than .001) and S100 B (Cohen d = 1.1; P less than .001).

The measurements were not particularly reliable, with retests over 6- to 12-month periods yielding varying results such that none of the test/retest cutoff points reached the cutoff for acceptable reliability.

The second study was an observational cohort study of the same 415 subjects. The researchers assessed the self-reported concussion history and the cumulative exposure to collision sports with serum levels of the above biomarkers. The only relationship between a biomarker history and self-reported concussions was higher baseline Abeta42, but that had a small effect size (P = .005). Among football players, there was no association between approximate number of head impacts and any baseline biomarker.

The third study looked at 31 subjects who had experienced a sports-related concussion, 29 of whom had had both a baseline and a postconcussion blood draw, and compared them with nonconcussed, demographically matched athletes.

Of all the biomarkers studied, only levels of S100B rose following a concussion, with 67% of concussed subjects experiencing such a change (P = .003). When the researchers restricted the analysis to subjects who had a blood draw within 4 hours of the concussion, 88% of the tests showed an increase (P = .001). UCH-L1 also rose in 86% of subjects, but this change was not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (P greater than .007).

Compared with controls, concussed individuals had significantly higher levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, and GFAP. Of the concussed patients, 79.4% had Abeta42 levels higher than the median of controls, 67.6% had higher levels of total tau than the median of controls, and 83.3% had higher levels of S100B. Restriction of analysis to blood drawn within 4 hours of the injury yielded values of 81.3%, 75.0%, and 88.2%, respectively.

When limited to blood draws taken within 4 hours of injury, the researchers found fair diagnostic accuracy for measurements of Abeta42 (area under the curve, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91), total tau (AUC, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90), and S100B (AUC, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.85). Abeta42 concentrations higher than 13.7 pg/mL were 75.0% sensitive and 82.4% specific to a sports-related concussion. Total tau concentrations higher than 1.7 pg/mL detected sports-related concussions at 75.0% sensitivity and 66.3% specificity, with acceptable diagnostic accuracy for white subjects (AUC, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.72-0.93). Also for white participants, S100B concentrations higher than 53 pg/mL predicted sports-related concussions with 83.3% sensitivity and 74.6% specificity.

The researchers found no associations between biomarkers and performance on clinical tests or time away from sports.

SOURCE: BM Asken et al. Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006613.

Concussion diagnosis has been constrained by reliance on subjective evidence, particularly in mild cases. Concussions also often result from a wide range of injuries, but focusing on sports-related concussions offers a chance to study biomarkers in a more controlled way.

These three studies represent the most comprehensive sports-related concussion biomarker work to date. The message may be that, for sports-related concussions, serum biomarkers may be able to detect the occurrence of a concussion, but they cannot predict motor, neurobehavioral, or neurocognitive outcome measures.

The study results also underline the need for larger, more complex prospective studies.

Erin Bigler, PhD, is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. Ellen Deibert, MD, is a neurologist in York, Pa. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006609 ). Dr. Bigler and Dr. Deibert have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Concussion diagnosis has been constrained by reliance on subjective evidence, particularly in mild cases. Concussions also often result from a wide range of injuries, but focusing on sports-related concussions offers a chance to study biomarkers in a more controlled way.

These three studies represent the most comprehensive sports-related concussion biomarker work to date. The message may be that, for sports-related concussions, serum biomarkers may be able to detect the occurrence of a concussion, but they cannot predict motor, neurobehavioral, or neurocognitive outcome measures.

The study results also underline the need for larger, more complex prospective studies.

Erin Bigler, PhD, is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. Ellen Deibert, MD, is a neurologist in York, Pa. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006609 ). Dr. Bigler and Dr. Deibert have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Concussion diagnosis has been constrained by reliance on subjective evidence, particularly in mild cases. Concussions also often result from a wide range of injuries, but focusing on sports-related concussions offers a chance to study biomarkers in a more controlled way.

These three studies represent the most comprehensive sports-related concussion biomarker work to date. The message may be that, for sports-related concussions, serum biomarkers may be able to detect the occurrence of a concussion, but they cannot predict motor, neurobehavioral, or neurocognitive outcome measures.

The study results also underline the need for larger, more complex prospective studies.

Erin Bigler, PhD, is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. Ellen Deibert, MD, is a neurologist in York, Pa. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006609 ). Dr. Bigler and Dr. Deibert have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A series of three studies in college students showed that some serum markers are associated with concussion but the background level of the markers can vary considerably. There was no association between the markers and history of concussion, and they markers varied significantly by sex and race.

The work, published in Neurology, suggests that there is hope for finding biomarkers for concussion, but much more work needs to be done.

Serum levels of amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), total tau, and S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B) were associated with concussion, especially when tests were performed within 4 hours of the injury. However, the varying background levels indicate that these biomarkers are not yet ready for clinical application.

All three studies looked at serum levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), and 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNPase).

In the first study, researchers recruited 415 college athletes without a concussion (61% male, 40% white). The researchers took measurements outside of the athletes’ competitive sports season to maximize the odds that the levels would represent a true baseline. The median time between blood draw and the last risk of head impact was 80 days (mean, 98.4 days; interquartile range, 38-204 days).

Males had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.75; P less than .001) and S100B (Cohen d = 0.56; P less than .001), while females had higher levels of CNPase (Cohen d = 0.43; P less than .001). White subjects had higher levels of Abeta42 (Cohen d = .28; P = .005) and CNPase (Cohen d = 0.46; P less than .001). Black subjects had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.61; P less than .001) and S100 B (Cohen d = 1.1; P less than .001).

The measurements were not particularly reliable, with retests over 6- to 12-month periods yielding varying results such that none of the test/retest cutoff points reached the cutoff for acceptable reliability.

The second study was an observational cohort study of the same 415 subjects. The researchers assessed the self-reported concussion history and the cumulative exposure to collision sports with serum levels of the above biomarkers. The only relationship between a biomarker history and self-reported concussions was higher baseline Abeta42, but that had a small effect size (P = .005). Among football players, there was no association between approximate number of head impacts and any baseline biomarker.

The third study looked at 31 subjects who had experienced a sports-related concussion, 29 of whom had had both a baseline and a postconcussion blood draw, and compared them with nonconcussed, demographically matched athletes.

Of all the biomarkers studied, only levels of S100B rose following a concussion, with 67% of concussed subjects experiencing such a change (P = .003). When the researchers restricted the analysis to subjects who had a blood draw within 4 hours of the concussion, 88% of the tests showed an increase (P = .001). UCH-L1 also rose in 86% of subjects, but this change was not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (P greater than .007).

Compared with controls, concussed individuals had significantly higher levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, and GFAP. Of the concussed patients, 79.4% had Abeta42 levels higher than the median of controls, 67.6% had higher levels of total tau than the median of controls, and 83.3% had higher levels of S100B. Restriction of analysis to blood drawn within 4 hours of the injury yielded values of 81.3%, 75.0%, and 88.2%, respectively.

When limited to blood draws taken within 4 hours of injury, the researchers found fair diagnostic accuracy for measurements of Abeta42 (area under the curve, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91), total tau (AUC, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90), and S100B (AUC, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.85). Abeta42 concentrations higher than 13.7 pg/mL were 75.0% sensitive and 82.4% specific to a sports-related concussion. Total tau concentrations higher than 1.7 pg/mL detected sports-related concussions at 75.0% sensitivity and 66.3% specificity, with acceptable diagnostic accuracy for white subjects (AUC, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.72-0.93). Also for white participants, S100B concentrations higher than 53 pg/mL predicted sports-related concussions with 83.3% sensitivity and 74.6% specificity.

The researchers found no associations between biomarkers and performance on clinical tests or time away from sports.

SOURCE: BM Asken et al. Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006613.

A series of three studies in college students showed that some serum markers are associated with concussion but the background level of the markers can vary considerably. There was no association between the markers and history of concussion, and they markers varied significantly by sex and race.

The work, published in Neurology, suggests that there is hope for finding biomarkers for concussion, but much more work needs to be done.

Serum levels of amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), total tau, and S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B) were associated with concussion, especially when tests were performed within 4 hours of the injury. However, the varying background levels indicate that these biomarkers are not yet ready for clinical application.

All three studies looked at serum levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), and 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNPase).

In the first study, researchers recruited 415 college athletes without a concussion (61% male, 40% white). The researchers took measurements outside of the athletes’ competitive sports season to maximize the odds that the levels would represent a true baseline. The median time between blood draw and the last risk of head impact was 80 days (mean, 98.4 days; interquartile range, 38-204 days).

Males had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.75; P less than .001) and S100B (Cohen d = 0.56; P less than .001), while females had higher levels of CNPase (Cohen d = 0.43; P less than .001). White subjects had higher levels of Abeta42 (Cohen d = .28; P = .005) and CNPase (Cohen d = 0.46; P less than .001). Black subjects had higher levels of UCH-L1 (Cohen d = 0.61; P less than .001) and S100 B (Cohen d = 1.1; P less than .001).

The measurements were not particularly reliable, with retests over 6- to 12-month periods yielding varying results such that none of the test/retest cutoff points reached the cutoff for acceptable reliability.

The second study was an observational cohort study of the same 415 subjects. The researchers assessed the self-reported concussion history and the cumulative exposure to collision sports with serum levels of the above biomarkers. The only relationship between a biomarker history and self-reported concussions was higher baseline Abeta42, but that had a small effect size (P = .005). Among football players, there was no association between approximate number of head impacts and any baseline biomarker.

The third study looked at 31 subjects who had experienced a sports-related concussion, 29 of whom had had both a baseline and a postconcussion blood draw, and compared them with nonconcussed, demographically matched athletes.

Of all the biomarkers studied, only levels of S100B rose following a concussion, with 67% of concussed subjects experiencing such a change (P = .003). When the researchers restricted the analysis to subjects who had a blood draw within 4 hours of the concussion, 88% of the tests showed an increase (P = .001). UCH-L1 also rose in 86% of subjects, but this change was not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (P greater than .007).

Compared with controls, concussed individuals had significantly higher levels of Abeta42, total tau, S100B, and GFAP. Of the concussed patients, 79.4% had Abeta42 levels higher than the median of controls, 67.6% had higher levels of total tau than the median of controls, and 83.3% had higher levels of S100B. Restriction of analysis to blood drawn within 4 hours of the injury yielded values of 81.3%, 75.0%, and 88.2%, respectively.

When limited to blood draws taken within 4 hours of injury, the researchers found fair diagnostic accuracy for measurements of Abeta42 (area under the curve, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91), total tau (AUC, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90), and S100B (AUC, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.64-0.85). Abeta42 concentrations higher than 13.7 pg/mL were 75.0% sensitive and 82.4% specific to a sports-related concussion. Total tau concentrations higher than 1.7 pg/mL detected sports-related concussions at 75.0% sensitivity and 66.3% specificity, with acceptable diagnostic accuracy for white subjects (AUC, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.72-0.93). Also for white participants, S100B concentrations higher than 53 pg/mL predicted sports-related concussions with 83.3% sensitivity and 74.6% specificity.

The researchers found no associations between biomarkers and performance on clinical tests or time away from sports.

SOURCE: BM Asken et al. Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006613.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Serum biomarkers show promise in concussion diagnosis, but much work remains.

Major finding: Serum levels of Abeta42, total tau, and S100B were elevated after concussions.

Study details: Prospective studies on 415 college athletes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Head Health Initiative, Banyan Biomarkers, and the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.

Sources: BM Asken et al. Neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006613.

Petrous Levounis: Substance Abuse Disorders

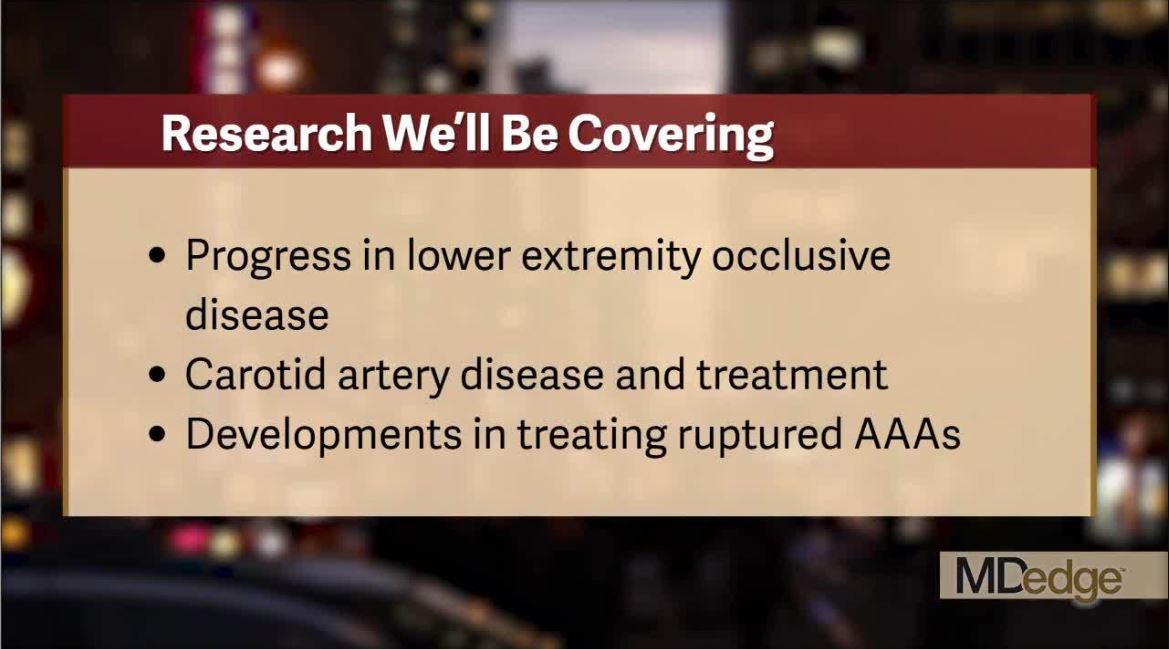

Catch all the action at the VEITHsymposium

The VEITHsymposium, held yearly in New York City, is a world-class meeting that covers the full range of vascular surgery and treatment. Frontline Medical Communications on behalf of our publication, Vascular Specialist, will be there to cover the newest and the best in devices, drugs, and surgical treatments for arterial and venous disease and the biological systems they impact.

Check out this video and get a flavor of what we will be covering live once the meeting starts. And be sure follow our continuing coverage next week at on our website and @VascularTweets. Also, check out our in depth reporting from the meeting afterward in the upcoming pages of Vascular Specialist.

The VEITHsymposium, held yearly in New York City, is a world-class meeting that covers the full range of vascular surgery and treatment. Frontline Medical Communications on behalf of our publication, Vascular Specialist, will be there to cover the newest and the best in devices, drugs, and surgical treatments for arterial and venous disease and the biological systems they impact.

Check out this video and get a flavor of what we will be covering live once the meeting starts. And be sure follow our continuing coverage next week at on our website and @VascularTweets. Also, check out our in depth reporting from the meeting afterward in the upcoming pages of Vascular Specialist.

The VEITHsymposium, held yearly in New York City, is a world-class meeting that covers the full range of vascular surgery and treatment. Frontline Medical Communications on behalf of our publication, Vascular Specialist, will be there to cover the newest and the best in devices, drugs, and surgical treatments for arterial and venous disease and the biological systems they impact.

Check out this video and get a flavor of what we will be covering live once the meeting starts. And be sure follow our continuing coverage next week at on our website and @VascularTweets. Also, check out our in depth reporting from the meeting afterward in the upcoming pages of Vascular Specialist.

Dark-roast dementia, cocktail dermatitis, and violent good guys

Dark roast has the most

The most … best chance … dark-roast coffee may protect your brain against Parkinson’s disease, okay? Rhyming can be hard. A Canadian study recently found that the compounds in brewed coffee, called phenylindanes, may have neuroprotective effects by inhibiting amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein. Researchers examined light roast, dark roast, and decaf dark roast and concluded that the dark roast contains stronger inhibitors. We always figured those ridiculous light-roast coffees were for the weak, but now we have proof.

Researchers also looked at the effect of caffeine. Sweet, sweet caffeine. While a potent psychoactive component, pure caffeine appeared to have no effect on amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein aggregation. Does this mean coffee is the cure for Parkinson’s disease? Not quite yet, but keep on chuggin’. And while you’re at it, have some pomegranate, too.

Cocktail dermatitis

Dermatologist Vincent DeLeo, MD, isn’t a psychic or a seer. But he plays one in the examination room. Every now and then, a patient walks in with noninflammatory blisters or hyperpigmentation, often on their hands. Dr. DeLeo takes a look and asks if the patient was enjoying some gin and tonics the previous weekend. “They think you’re God because of course they were,” he told an audience at the recent Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

The culprit? An allergy to the dark green skin of limes, a.k.a. “margarita photodermatitis.” Dr. DeLeo says it may take a few days for the blisters to appear. And he advised colleagues to not photo test the patient because it could make things worse. As for treatment, steroids can help. So can switching to Scotch and soda.

The animals are getting high

Australian animals are getting a contact high, according to a research team that studied stream invertebrates around Melbourne. When we consume pharmaceuticals, our bodies do not totally absorb them. Now, evidence shows that the residual drugs that leave our system are ending up in waterways. What does that mean? It means animals are getting free drugs, and that’s just not fair.

The water-dwelling invertebrates are also passing on these residual compounds to other animals, like spiders who eat invertebrate larvae. Researchers also predicted that platypuses in particular might soon be exposed to high levels of antidepressants. At least the platypuses will be happy.

Health care goes to the movies

Science, as many of those involved in the time-honored but often misunderstood pursuit of truthiness would agree, is a strange, wonderful, yet fickle mistress. One day, she’ll have you comparing the quantity and quality of infant stools or shoving whooping cough bacteria up people’s noses. And the next day, she’ll invite you to join her at the local mega-movie multiplex for the latest Hollywood blockbuster.

Just ask Robert Olympia, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates, who watched 10 superhero-based films from 2015 and 2016 and counted the violent acts committed by “good guys” and “bad guys.” Their analysis, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics in Orlando, shows that good guys committed 23 violent acts per hour, compared with 18 per hour for the bad guys. Young people who watch these movies “may be influenced by their portrayal of risk-taking behaviors and acts of violence. … Pediatric health care providers should educate families about the violence depicted in this genre of film and the potential dangers that may occur when children attempt to emulate these perceived heroes,” said Dr. Olympia.

Of course, his own superhero-ready name suggests that he may be battling – in a nonviolent way, we’re sure – Bleeding Ulcer, The Bowel Movement, Anal Fissure, Migraineur, and/or The Endoscopist in the next Avengers movie.

Dark roast has the most

The most … best chance … dark-roast coffee may protect your brain against Parkinson’s disease, okay? Rhyming can be hard. A Canadian study recently found that the compounds in brewed coffee, called phenylindanes, may have neuroprotective effects by inhibiting amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein. Researchers examined light roast, dark roast, and decaf dark roast and concluded that the dark roast contains stronger inhibitors. We always figured those ridiculous light-roast coffees were for the weak, but now we have proof.

Researchers also looked at the effect of caffeine. Sweet, sweet caffeine. While a potent psychoactive component, pure caffeine appeared to have no effect on amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein aggregation. Does this mean coffee is the cure for Parkinson’s disease? Not quite yet, but keep on chuggin’. And while you’re at it, have some pomegranate, too.

Cocktail dermatitis

Dermatologist Vincent DeLeo, MD, isn’t a psychic or a seer. But he plays one in the examination room. Every now and then, a patient walks in with noninflammatory blisters or hyperpigmentation, often on their hands. Dr. DeLeo takes a look and asks if the patient was enjoying some gin and tonics the previous weekend. “They think you’re God because of course they were,” he told an audience at the recent Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

The culprit? An allergy to the dark green skin of limes, a.k.a. “margarita photodermatitis.” Dr. DeLeo says it may take a few days for the blisters to appear. And he advised colleagues to not photo test the patient because it could make things worse. As for treatment, steroids can help. So can switching to Scotch and soda.

The animals are getting high

Australian animals are getting a contact high, according to a research team that studied stream invertebrates around Melbourne. When we consume pharmaceuticals, our bodies do not totally absorb them. Now, evidence shows that the residual drugs that leave our system are ending up in waterways. What does that mean? It means animals are getting free drugs, and that’s just not fair.

The water-dwelling invertebrates are also passing on these residual compounds to other animals, like spiders who eat invertebrate larvae. Researchers also predicted that platypuses in particular might soon be exposed to high levels of antidepressants. At least the platypuses will be happy.

Health care goes to the movies

Science, as many of those involved in the time-honored but often misunderstood pursuit of truthiness would agree, is a strange, wonderful, yet fickle mistress. One day, she’ll have you comparing the quantity and quality of infant stools or shoving whooping cough bacteria up people’s noses. And the next day, she’ll invite you to join her at the local mega-movie multiplex for the latest Hollywood blockbuster.

Just ask Robert Olympia, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates, who watched 10 superhero-based films from 2015 and 2016 and counted the violent acts committed by “good guys” and “bad guys.” Their analysis, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics in Orlando, shows that good guys committed 23 violent acts per hour, compared with 18 per hour for the bad guys. Young people who watch these movies “may be influenced by their portrayal of risk-taking behaviors and acts of violence. … Pediatric health care providers should educate families about the violence depicted in this genre of film and the potential dangers that may occur when children attempt to emulate these perceived heroes,” said Dr. Olympia.

Of course, his own superhero-ready name suggests that he may be battling – in a nonviolent way, we’re sure – Bleeding Ulcer, The Bowel Movement, Anal Fissure, Migraineur, and/or The Endoscopist in the next Avengers movie.

Dark roast has the most

The most … best chance … dark-roast coffee may protect your brain against Parkinson’s disease, okay? Rhyming can be hard. A Canadian study recently found that the compounds in brewed coffee, called phenylindanes, may have neuroprotective effects by inhibiting amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein. Researchers examined light roast, dark roast, and decaf dark roast and concluded that the dark roast contains stronger inhibitors. We always figured those ridiculous light-roast coffees were for the weak, but now we have proof.

Researchers also looked at the effect of caffeine. Sweet, sweet caffeine. While a potent psychoactive component, pure caffeine appeared to have no effect on amyloid-beta, tau, or alpha-synuclein aggregation. Does this mean coffee is the cure for Parkinson’s disease? Not quite yet, but keep on chuggin’. And while you’re at it, have some pomegranate, too.

Cocktail dermatitis

Dermatologist Vincent DeLeo, MD, isn’t a psychic or a seer. But he plays one in the examination room. Every now and then, a patient walks in with noninflammatory blisters or hyperpigmentation, often on their hands. Dr. DeLeo takes a look and asks if the patient was enjoying some gin and tonics the previous weekend. “They think you’re God because of course they were,” he told an audience at the recent Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

The culprit? An allergy to the dark green skin of limes, a.k.a. “margarita photodermatitis.” Dr. DeLeo says it may take a few days for the blisters to appear. And he advised colleagues to not photo test the patient because it could make things worse. As for treatment, steroids can help. So can switching to Scotch and soda.

The animals are getting high

Australian animals are getting a contact high, according to a research team that studied stream invertebrates around Melbourne. When we consume pharmaceuticals, our bodies do not totally absorb them. Now, evidence shows that the residual drugs that leave our system are ending up in waterways. What does that mean? It means animals are getting free drugs, and that’s just not fair.

The water-dwelling invertebrates are also passing on these residual compounds to other animals, like spiders who eat invertebrate larvae. Researchers also predicted that platypuses in particular might soon be exposed to high levels of antidepressants. At least the platypuses will be happy.

Health care goes to the movies

Science, as many of those involved in the time-honored but often misunderstood pursuit of truthiness would agree, is a strange, wonderful, yet fickle mistress. One day, she’ll have you comparing the quantity and quality of infant stools or shoving whooping cough bacteria up people’s noses. And the next day, she’ll invite you to join her at the local mega-movie multiplex for the latest Hollywood blockbuster.

Just ask Robert Olympia, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates, who watched 10 superhero-based films from 2015 and 2016 and counted the violent acts committed by “good guys” and “bad guys.” Their analysis, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics in Orlando, shows that good guys committed 23 violent acts per hour, compared with 18 per hour for the bad guys. Young people who watch these movies “may be influenced by their portrayal of risk-taking behaviors and acts of violence. … Pediatric health care providers should educate families about the violence depicted in this genre of film and the potential dangers that may occur when children attempt to emulate these perceived heroes,” said Dr. Olympia.

Of course, his own superhero-ready name suggests that he may be battling – in a nonviolent way, we’re sure – Bleeding Ulcer, The Bowel Movement, Anal Fissure, Migraineur, and/or The Endoscopist in the next Avengers movie.

FDA accepts priority review of dupilumab for adolescent atopic dermatitis

The Food and Drug Administration has accepted the who have not been well controlled with topical therapies or who are unable to use topical therapies.

In a statement, dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and Sanofi announced that the target action data for an FDA decision on dupilumab for adolescents is March 11, 2019. “Currently, there are no FDA-approved systemic biologic medicines to treat adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis,” the companies said in the statement.

The sBLA for dupilumab use in teens is based on data from a phase 3 study presented at the annual congress of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in September 2018. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo.

According to the companies, the most common adverse events included injection site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores. Conjunctivitis has also been reported in some patients.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is currently approved for treating uncontrolled moderate to severe AD in adults and, more recently, as an add-on maintenance treatment in patients with moderate to severe asthma aged 12 years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid–dependent asthma.

The FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications.

The Food and Drug Administration has accepted the who have not been well controlled with topical therapies or who are unable to use topical therapies.

In a statement, dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and Sanofi announced that the target action data for an FDA decision on dupilumab for adolescents is March 11, 2019. “Currently, there are no FDA-approved systemic biologic medicines to treat adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis,” the companies said in the statement.

The sBLA for dupilumab use in teens is based on data from a phase 3 study presented at the annual congress of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in September 2018. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo.

According to the companies, the most common adverse events included injection site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores. Conjunctivitis has also been reported in some patients.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is currently approved for treating uncontrolled moderate to severe AD in adults and, more recently, as an add-on maintenance treatment in patients with moderate to severe asthma aged 12 years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid–dependent asthma.

The FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications.

The Food and Drug Administration has accepted the who have not been well controlled with topical therapies or who are unable to use topical therapies.

In a statement, dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and Sanofi announced that the target action data for an FDA decision on dupilumab for adolescents is March 11, 2019. “Currently, there are no FDA-approved systemic biologic medicines to treat adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis,” the companies said in the statement.

The sBLA for dupilumab use in teens is based on data from a phase 3 study presented at the annual congress of European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in September 2018. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo.

According to the companies, the most common adverse events included injection site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores. Conjunctivitis has also been reported in some patients.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is currently approved for treating uncontrolled moderate to severe AD in adults and, more recently, as an add-on maintenance treatment in patients with moderate to severe asthma aged 12 years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid–dependent asthma.

The FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications.

MBDA score predicts, tracks RA patients’ responses to tofacitinib and rituximab

CHICAGO – The commercially available multibiomarker disease activity score assay and power Doppler ultrasound at baseline in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib predicted 12-week responses on some clinical, imaging, and biomarker endpoints, according to findings from an investigator-initiated, open-label study.

The blood test–based multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) score, which is calculated using measurements of 12 inflammatory biomarkers to score RA disease activity on a 0-100 point scale (Vectra DA, Myriad Autoimmune), also appears to track RA patients’ responses to rituximab, according to a post-hoc analysis of three cohort studies.

The findings of both studies were presented in posters at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. They are the first studies to evaluate early musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSUS) and MBDA score changes as predictors of response to tofacitinib in patients with RA, and the first to assess the ability of the MBDA score to track response to rituximab treatment. They provide valuable information that can help guide patient treatment and thereby improve outcomes, Elena Hitraya, MD, PhD, chief medical officer for Crescendo Bioscience/Myriad Autoimmune, San Francisco, said in an interview.

In the tofacitinib study, 25 RA patients with a mean age of 52 years, mean disease duration of 10.4 years, baseline Disease Activity Score 28-joint count (DAS28) greater than 3.2, and power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) scores greater than 10 were treated with the approved oral tofacitinib dose of 5 mg twice daily. Assessments at baseline, 2 weeks, and 12 weeks included MSUS to score 34 joints for PDUS and gray scale ultrasound (GSUS), MBDA score, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and DAS28, according to Amir Razmjou, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Statistically significant improvement was seen on all measures over the 12-week study period (all at P less than .0001). For example, from baseline to 12 weeks the PDUS score improved from 28.6 to 12.2, GSUS score improved from 48.4 to 37.9, MBDA score improved from 50.6 to 39.6, CDAI score improved from 39.9 to 21.6, and DAS28–erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) score improved from 6.3 to 4.6, they said, noting further that baseline PDUS and MBDA scores significantly predicted CDAI and DAS28 responses at 12 weeks (P less than .01).

In the rituximab study, the MBDA score tracked disease activity in 57 RA patients from three different cohorts with a mean age of 57 years and mean disease duration of 11.5 years. Changes in the MBDA score reflected the degree of treatment response, Nadia M.T. Roodenrijs of University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) and her colleagues reported.

All patients were treated with 1,000 mg rituximab and 100 mg methylprednisolone on days 1 and 15, and MBDA score was assessed at baseline and 6 months.

MBDA scores correlated significantly with change from baseline to 6 months in DAS28-ESR (r = 0.60), DAS28–high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, (DAS28-hsCRP; r = 0.48), ESR (r = 0.48), and hsCRP (r = 0.71), and with European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) good or moderate response at 6 months based on DAS28-ESR (adjusted odds ratio, 0.91).

Extensive work has been done to validate the MBDA score for assessing disease activity, and it has been shown to perform well for predicting response to a variety of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents, Dr. Hitraya explained.

Additionally, multiple studies have demonstrated that the MBDA score defines risk categories for radiographic progression and performs better than traditional measures of disease activity for identifying those at increased risk of radiographic progression, which can help physicians mitigate associated risks through increased surveillance and therapeutic choices, she said.

“Having data for these specific molecules [tofacitinib and rituximab] is very important for rheumatologists,” Dr. Hitraya said.

The tofacitinib study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Razmjou and Dr. Roodenrijs each reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Razmjou A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 582; Roodenrijs N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1500.

CHICAGO – The commercially available multibiomarker disease activity score assay and power Doppler ultrasound at baseline in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib predicted 12-week responses on some clinical, imaging, and biomarker endpoints, according to findings from an investigator-initiated, open-label study.

The blood test–based multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) score, which is calculated using measurements of 12 inflammatory biomarkers to score RA disease activity on a 0-100 point scale (Vectra DA, Myriad Autoimmune), also appears to track RA patients’ responses to rituximab, according to a post-hoc analysis of three cohort studies.

The findings of both studies were presented in posters at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. They are the first studies to evaluate early musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSUS) and MBDA score changes as predictors of response to tofacitinib in patients with RA, and the first to assess the ability of the MBDA score to track response to rituximab treatment. They provide valuable information that can help guide patient treatment and thereby improve outcomes, Elena Hitraya, MD, PhD, chief medical officer for Crescendo Bioscience/Myriad Autoimmune, San Francisco, said in an interview.

In the tofacitinib study, 25 RA patients with a mean age of 52 years, mean disease duration of 10.4 years, baseline Disease Activity Score 28-joint count (DAS28) greater than 3.2, and power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) scores greater than 10 were treated with the approved oral tofacitinib dose of 5 mg twice daily. Assessments at baseline, 2 weeks, and 12 weeks included MSUS to score 34 joints for PDUS and gray scale ultrasound (GSUS), MBDA score, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and DAS28, according to Amir Razmjou, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Statistically significant improvement was seen on all measures over the 12-week study period (all at P less than .0001). For example, from baseline to 12 weeks the PDUS score improved from 28.6 to 12.2, GSUS score improved from 48.4 to 37.9, MBDA score improved from 50.6 to 39.6, CDAI score improved from 39.9 to 21.6, and DAS28–erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) score improved from 6.3 to 4.6, they said, noting further that baseline PDUS and MBDA scores significantly predicted CDAI and DAS28 responses at 12 weeks (P less than .01).

In the rituximab study, the MBDA score tracked disease activity in 57 RA patients from three different cohorts with a mean age of 57 years and mean disease duration of 11.5 years. Changes in the MBDA score reflected the degree of treatment response, Nadia M.T. Roodenrijs of University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) and her colleagues reported.

All patients were treated with 1,000 mg rituximab and 100 mg methylprednisolone on days 1 and 15, and MBDA score was assessed at baseline and 6 months.

MBDA scores correlated significantly with change from baseline to 6 months in DAS28-ESR (r = 0.60), DAS28–high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, (DAS28-hsCRP; r = 0.48), ESR (r = 0.48), and hsCRP (r = 0.71), and with European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) good or moderate response at 6 months based on DAS28-ESR (adjusted odds ratio, 0.91).

Extensive work has been done to validate the MBDA score for assessing disease activity, and it has been shown to perform well for predicting response to a variety of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents, Dr. Hitraya explained.

Additionally, multiple studies have demonstrated that the MBDA score defines risk categories for radiographic progression and performs better than traditional measures of disease activity for identifying those at increased risk of radiographic progression, which can help physicians mitigate associated risks through increased surveillance and therapeutic choices, she said.

“Having data for these specific molecules [tofacitinib and rituximab] is very important for rheumatologists,” Dr. Hitraya said.

The tofacitinib study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Razmjou and Dr. Roodenrijs each reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Razmjou A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 582; Roodenrijs N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1500.

CHICAGO – The commercially available multibiomarker disease activity score assay and power Doppler ultrasound at baseline in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib predicted 12-week responses on some clinical, imaging, and biomarker endpoints, according to findings from an investigator-initiated, open-label study.

The blood test–based multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) score, which is calculated using measurements of 12 inflammatory biomarkers to score RA disease activity on a 0-100 point scale (Vectra DA, Myriad Autoimmune), also appears to track RA patients’ responses to rituximab, according to a post-hoc analysis of three cohort studies.

The findings of both studies were presented in posters at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. They are the first studies to evaluate early musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSUS) and MBDA score changes as predictors of response to tofacitinib in patients with RA, and the first to assess the ability of the MBDA score to track response to rituximab treatment. They provide valuable information that can help guide patient treatment and thereby improve outcomes, Elena Hitraya, MD, PhD, chief medical officer for Crescendo Bioscience/Myriad Autoimmune, San Francisco, said in an interview.

In the tofacitinib study, 25 RA patients with a mean age of 52 years, mean disease duration of 10.4 years, baseline Disease Activity Score 28-joint count (DAS28) greater than 3.2, and power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) scores greater than 10 were treated with the approved oral tofacitinib dose of 5 mg twice daily. Assessments at baseline, 2 weeks, and 12 weeks included MSUS to score 34 joints for PDUS and gray scale ultrasound (GSUS), MBDA score, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), and DAS28, according to Amir Razmjou, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Statistically significant improvement was seen on all measures over the 12-week study period (all at P less than .0001). For example, from baseline to 12 weeks the PDUS score improved from 28.6 to 12.2, GSUS score improved from 48.4 to 37.9, MBDA score improved from 50.6 to 39.6, CDAI score improved from 39.9 to 21.6, and DAS28–erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) score improved from 6.3 to 4.6, they said, noting further that baseline PDUS and MBDA scores significantly predicted CDAI and DAS28 responses at 12 weeks (P less than .01).

In the rituximab study, the MBDA score tracked disease activity in 57 RA patients from three different cohorts with a mean age of 57 years and mean disease duration of 11.5 years. Changes in the MBDA score reflected the degree of treatment response, Nadia M.T. Roodenrijs of University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) and her colleagues reported.

All patients were treated with 1,000 mg rituximab and 100 mg methylprednisolone on days 1 and 15, and MBDA score was assessed at baseline and 6 months.

MBDA scores correlated significantly with change from baseline to 6 months in DAS28-ESR (r = 0.60), DAS28–high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, (DAS28-hsCRP; r = 0.48), ESR (r = 0.48), and hsCRP (r = 0.71), and with European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) good or moderate response at 6 months based on DAS28-ESR (adjusted odds ratio, 0.91).

Extensive work has been done to validate the MBDA score for assessing disease activity, and it has been shown to perform well for predicting response to a variety of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents, Dr. Hitraya explained.

Additionally, multiple studies have demonstrated that the MBDA score defines risk categories for radiographic progression and performs better than traditional measures of disease activity for identifying those at increased risk of radiographic progression, which can help physicians mitigate associated risks through increased surveillance and therapeutic choices, she said.

“Having data for these specific molecules [tofacitinib and rituximab] is very important for rheumatologists,” Dr. Hitraya said.

The tofacitinib study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Razmjou and Dr. Roodenrijs each reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Razmjou A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 582; Roodenrijs N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1500.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Baseline PDUS and MBDA scores predicted 12-week CDAI and DAS28 responses to tofacitinib (P less than .01); MBDA scores correlated significantly with EULAR good or moderate response at 6 months (adjusted OR, 0.91).

Study details: An open-label study of 25 patients and a post-hoc analysis of three studies including 57 patients.

Disclosures: The tofacitinib study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Razmjou and Dr. Roodenrijs each reported having no disclosures. Dr. Hitraya is an employee of Myriad Genetics.

Source: Razmjou A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 582; Roodenrijs N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1500.

Valve-in-valve TAVR benefits maintained at 3 years

SAN DIEGO – Early benefits of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for patients with failing surgical aortic bioprosthetic valves are sustained for at least 3 years, based on results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Previously published data for the 365 patients from the PARTNER Valve-in-Valve study showed dramatic improvements at 30 days and 1 year in hemodynamic measures, mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, and quality of life (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2253-62).

At the 3-year mark, about one-third of patients had died, reported lead investigator John G. Webb, MD, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. “I think we can say that this reflects multiple comorbidities in this high-risk patient population with an STS [Society of Thoracic Surgery] risk score of 1.9%. Patients were selected for being at extreme risk,” he commented. “This is not unexpected. ... This is very comparable to what we saw in the early PARTNER trials as well.”

For survivors, however, the early benefits were still present and largely unattenuated at 3 years. For example, about half of patients were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I at 30 days, at 1 year, and at 3 years. And Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score, reflecting heart failure–related quality of life, averaged 70-77 at all three time points.

The proportion of patients needing yet another valve replacement (surgical or transcatheter), possibly signaling structural valve deterioration or degeneration, was less than 2% at 3 years, and hemodynamic parameters remained good.

Practical matters

Valve-in-valve TAVR need not be restricted to academic high-volume centers, according to Dr. Webb. “I run a regional program, and my regional program had a hub-and-spoke model where this was restricted to one institution, and four other institutions just did routine transfemoral TAVR. We had to give up that because these are some of the easiest TAVR procedures that we do. You have a radio-opaque valve, you know the angle, you know the size, it seals well, you don’t get annular rupture, you don’t need pacemakers very often.”

In addition, recent TCT registry data suggest that outcomes with valve-in-valve TAVR are better than those with native-valve TAVR, Dr. Webb noted. “There’s a knowledge base that’s required that routine TAVR operators may not have. But it can be taught, it can be learned, and it’s not a difficult procedure when you know how to do it.”

“This study is very, very useful for all of us,” commented press conference panelist Jeffrey J. Popma, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “But should we be reconsidering anticoagulation therapy in some of the valve-in-valve procedures? We have learned from the leaflet thrombosis data that one of the risk factors for that is a valve-in-valve procedure. Clinically, we have seen a few cases where thrombus does form in the nidus of all the material that’s there.”

“There was no sign of leaflet thrombosis playing a role in reintervention,” Dr. Webb replied. “[Reintervention] was performed for various reasons, including leaks and valves that were too small. So it wasn’t clear that leaflet thrombosis was a factor in this study. That being said, we weren’t looking for it; we didn’t have sensitive means [to detect it], we weren’t doing transesophageal echoes, we weren’t doing CTs.

“Personally, I suspect that maybe we should be routinely anticoagulating all of our valve implants,” he added. “We certainly do it for our mitral valves routinely, and although I can’t recommend it, I have to admit that we do do this for aortic valves in my particular center. But I have no data from this study to support that either way.”

Study details

The 365 patients studied came from both an initial registry and a continued access registry, but were largely similar on baseline characteristics. All underwent valve-in-valve TAVR with SAPIEN XT transcatheter heart valves.

Mortality in the cohort was 12.1% at 1 year, 22.2% at 2 years, and 32.7% at 3 years, according to results reported at the meeting, which is sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. In contrast, the rate of stroke was stable over time, at 5.1%, 5.1%, and 6.2%, respectively.

Repeat valve replacement (either surgical or transcatheter) had been performed in 0.6% of patients at 1 year, 0.6% at 2 years, and 1.9% at 3 years. “I think this is comparable to [what is seen in] surgical series,” Dr. Webb commented.

Between 30 days and 3 years, there were insignificant decreases in total aortic regurgitation that was moderate or worse in severity (from 2.9% to 2.5%) and paravalvular aortic regurgitation of these severities (from 2.6% to 1.4%). Although the valve used was older, “still, we had excellent sealing and aortic insufficiency was not a problem with these patients,” he noted.

In “interesting” findings, prevalence of mitral regurgitation that was moderate or worse continued falling, from 17.2% at 30 days to 8.6% at 3 years, and prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation that was moderate or worse did as well, from 21.8% to 18.8%.

“I was a little suspicious this was just a survival issue, that patients with severe mitral or tricuspid regurgitation died and, consequently, the average patient was less likely to have [these findings]. But the analysis that’s being done is linear mixed-effects analysis, which accounts for the survival bias,” Dr. Webb said.

The reasons for these trends are unknown, but possibly improved left ventricular function led to functional (rather than structural) improvements in mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

At 3 years, proportions of patients with various NYHA classes were much the same as they had been at 30 days: class I (51.4% vs. 53.9%), class II (34.6% vs. 35.7%), and class III (13.0% vs. 9.2%). Similarly, the mean KCCQ overall summary score at 30 days (70.8) was sustained at 3 years (73.1).

Risk of death did not differ significantly according to the surgical valve size as labeled, the surgical valve true internal dimensions, the mode of valve failure, the approach used (transfemoral vs. transthoracic), or the residual gradient after valve implantation.

Analysis of the registry data is ongoing. For example, the investigators will be looking more closely at determinants of outcomes, such as additional characteristics of the surgical valve alone and in combination with those of the new valve. “We are all very aware that a lot of the outcomes have to do with what surgical valves you had to begin with. I think that is really critical – what surgical valve is in there,” he said.

Dr. Webb reported that he receives grant/research support and honoraria from, and is on the steering committee for, Edwards Lifesciences. The registry is sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences.

SAN DIEGO – Early benefits of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for patients with failing surgical aortic bioprosthetic valves are sustained for at least 3 years, based on results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Previously published data for the 365 patients from the PARTNER Valve-in-Valve study showed dramatic improvements at 30 days and 1 year in hemodynamic measures, mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, and quality of life (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2253-62).

At the 3-year mark, about one-third of patients had died, reported lead investigator John G. Webb, MD, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. “I think we can say that this reflects multiple comorbidities in this high-risk patient population with an STS [Society of Thoracic Surgery] risk score of 1.9%. Patients were selected for being at extreme risk,” he commented. “This is not unexpected. ... This is very comparable to what we saw in the early PARTNER trials as well.”

For survivors, however, the early benefits were still present and largely unattenuated at 3 years. For example, about half of patients were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I at 30 days, at 1 year, and at 3 years. And Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score, reflecting heart failure–related quality of life, averaged 70-77 at all three time points.

The proportion of patients needing yet another valve replacement (surgical or transcatheter), possibly signaling structural valve deterioration or degeneration, was less than 2% at 3 years, and hemodynamic parameters remained good.

Practical matters

Valve-in-valve TAVR need not be restricted to academic high-volume centers, according to Dr. Webb. “I run a regional program, and my regional program had a hub-and-spoke model where this was restricted to one institution, and four other institutions just did routine transfemoral TAVR. We had to give up that because these are some of the easiest TAVR procedures that we do. You have a radio-opaque valve, you know the angle, you know the size, it seals well, you don’t get annular rupture, you don’t need pacemakers very often.”

In addition, recent TCT registry data suggest that outcomes with valve-in-valve TAVR are better than those with native-valve TAVR, Dr. Webb noted. “There’s a knowledge base that’s required that routine TAVR operators may not have. But it can be taught, it can be learned, and it’s not a difficult procedure when you know how to do it.”

“This study is very, very useful for all of us,” commented press conference panelist Jeffrey J. Popma, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “But should we be reconsidering anticoagulation therapy in some of the valve-in-valve procedures? We have learned from the leaflet thrombosis data that one of the risk factors for that is a valve-in-valve procedure. Clinically, we have seen a few cases where thrombus does form in the nidus of all the material that’s there.”

“There was no sign of leaflet thrombosis playing a role in reintervention,” Dr. Webb replied. “[Reintervention] was performed for various reasons, including leaks and valves that were too small. So it wasn’t clear that leaflet thrombosis was a factor in this study. That being said, we weren’t looking for it; we didn’t have sensitive means [to detect it], we weren’t doing transesophageal echoes, we weren’t doing CTs.

“Personally, I suspect that maybe we should be routinely anticoagulating all of our valve implants,” he added. “We certainly do it for our mitral valves routinely, and although I can’t recommend it, I have to admit that we do do this for aortic valves in my particular center. But I have no data from this study to support that either way.”

Study details

The 365 patients studied came from both an initial registry and a continued access registry, but were largely similar on baseline characteristics. All underwent valve-in-valve TAVR with SAPIEN XT transcatheter heart valves.

Mortality in the cohort was 12.1% at 1 year, 22.2% at 2 years, and 32.7% at 3 years, according to results reported at the meeting, which is sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. In contrast, the rate of stroke was stable over time, at 5.1%, 5.1%, and 6.2%, respectively.

Repeat valve replacement (either surgical or transcatheter) had been performed in 0.6% of patients at 1 year, 0.6% at 2 years, and 1.9% at 3 years. “I think this is comparable to [what is seen in] surgical series,” Dr. Webb commented.

Between 30 days and 3 years, there were insignificant decreases in total aortic regurgitation that was moderate or worse in severity (from 2.9% to 2.5%) and paravalvular aortic regurgitation of these severities (from 2.6% to 1.4%). Although the valve used was older, “still, we had excellent sealing and aortic insufficiency was not a problem with these patients,” he noted.

In “interesting” findings, prevalence of mitral regurgitation that was moderate or worse continued falling, from 17.2% at 30 days to 8.6% at 3 years, and prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation that was moderate or worse did as well, from 21.8% to 18.8%.

“I was a little suspicious this was just a survival issue, that patients with severe mitral or tricuspid regurgitation died and, consequently, the average patient was less likely to have [these findings]. But the analysis that’s being done is linear mixed-effects analysis, which accounts for the survival bias,” Dr. Webb said.

The reasons for these trends are unknown, but possibly improved left ventricular function led to functional (rather than structural) improvements in mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

At 3 years, proportions of patients with various NYHA classes were much the same as they had been at 30 days: class I (51.4% vs. 53.9%), class II (34.6% vs. 35.7%), and class III (13.0% vs. 9.2%). Similarly, the mean KCCQ overall summary score at 30 days (70.8) was sustained at 3 years (73.1).

Risk of death did not differ significantly according to the surgical valve size as labeled, the surgical valve true internal dimensions, the mode of valve failure, the approach used (transfemoral vs. transthoracic), or the residual gradient after valve implantation.

Analysis of the registry data is ongoing. For example, the investigators will be looking more closely at determinants of outcomes, such as additional characteristics of the surgical valve alone and in combination with those of the new valve. “We are all very aware that a lot of the outcomes have to do with what surgical valves you had to begin with. I think that is really critical – what surgical valve is in there,” he said.

Dr. Webb reported that he receives grant/research support and honoraria from, and is on the steering committee for, Edwards Lifesciences. The registry is sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences.

SAN DIEGO – Early benefits of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for patients with failing surgical aortic bioprosthetic valves are sustained for at least 3 years, based on results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Previously published data for the 365 patients from the PARTNER Valve-in-Valve study showed dramatic improvements at 30 days and 1 year in hemodynamic measures, mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, and quality of life (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2253-62).

At the 3-year mark, about one-third of patients had died, reported lead investigator John G. Webb, MD, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. “I think we can say that this reflects multiple comorbidities in this high-risk patient population with an STS [Society of Thoracic Surgery] risk score of 1.9%. Patients were selected for being at extreme risk,” he commented. “This is not unexpected. ... This is very comparable to what we saw in the early PARTNER trials as well.”

For survivors, however, the early benefits were still present and largely unattenuated at 3 years. For example, about half of patients were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I at 30 days, at 1 year, and at 3 years. And Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score, reflecting heart failure–related quality of life, averaged 70-77 at all three time points.

The proportion of patients needing yet another valve replacement (surgical or transcatheter), possibly signaling structural valve deterioration or degeneration, was less than 2% at 3 years, and hemodynamic parameters remained good.

Practical matters

Valve-in-valve TAVR need not be restricted to academic high-volume centers, according to Dr. Webb. “I run a regional program, and my regional program had a hub-and-spoke model where this was restricted to one institution, and four other institutions just did routine transfemoral TAVR. We had to give up that because these are some of the easiest TAVR procedures that we do. You have a radio-opaque valve, you know the angle, you know the size, it seals well, you don’t get annular rupture, you don’t need pacemakers very often.”

In addition, recent TCT registry data suggest that outcomes with valve-in-valve TAVR are better than those with native-valve TAVR, Dr. Webb noted. “There’s a knowledge base that’s required that routine TAVR operators may not have. But it can be taught, it can be learned, and it’s not a difficult procedure when you know how to do it.”

“This study is very, very useful for all of us,” commented press conference panelist Jeffrey J. Popma, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “But should we be reconsidering anticoagulation therapy in some of the valve-in-valve procedures? We have learned from the leaflet thrombosis data that one of the risk factors for that is a valve-in-valve procedure. Clinically, we have seen a few cases where thrombus does form in the nidus of all the material that’s there.”

“There was no sign of leaflet thrombosis playing a role in reintervention,” Dr. Webb replied. “[Reintervention] was performed for various reasons, including leaks and valves that were too small. So it wasn’t clear that leaflet thrombosis was a factor in this study. That being said, we weren’t looking for it; we didn’t have sensitive means [to detect it], we weren’t doing transesophageal echoes, we weren’t doing CTs.

“Personally, I suspect that maybe we should be routinely anticoagulating all of our valve implants,” he added. “We certainly do it for our mitral valves routinely, and although I can’t recommend it, I have to admit that we do do this for aortic valves in my particular center. But I have no data from this study to support that either way.”

Study details

The 365 patients studied came from both an initial registry and a continued access registry, but were largely similar on baseline characteristics. All underwent valve-in-valve TAVR with SAPIEN XT transcatheter heart valves.

Mortality in the cohort was 12.1% at 1 year, 22.2% at 2 years, and 32.7% at 3 years, according to results reported at the meeting, which is sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. In contrast, the rate of stroke was stable over time, at 5.1%, 5.1%, and 6.2%, respectively.

Repeat valve replacement (either surgical or transcatheter) had been performed in 0.6% of patients at 1 year, 0.6% at 2 years, and 1.9% at 3 years. “I think this is comparable to [what is seen in] surgical series,” Dr. Webb commented.

Between 30 days and 3 years, there were insignificant decreases in total aortic regurgitation that was moderate or worse in severity (from 2.9% to 2.5%) and paravalvular aortic regurgitation of these severities (from 2.6% to 1.4%). Although the valve used was older, “still, we had excellent sealing and aortic insufficiency was not a problem with these patients,” he noted.

In “interesting” findings, prevalence of mitral regurgitation that was moderate or worse continued falling, from 17.2% at 30 days to 8.6% at 3 years, and prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation that was moderate or worse did as well, from 21.8% to 18.8%.

“I was a little suspicious this was just a survival issue, that patients with severe mitral or tricuspid regurgitation died and, consequently, the average patient was less likely to have [these findings]. But the analysis that’s being done is linear mixed-effects analysis, which accounts for the survival bias,” Dr. Webb said.

The reasons for these trends are unknown, but possibly improved left ventricular function led to functional (rather than structural) improvements in mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

At 3 years, proportions of patients with various NYHA classes were much the same as they had been at 30 days: class I (51.4% vs. 53.9%), class II (34.6% vs. 35.7%), and class III (13.0% vs. 9.2%). Similarly, the mean KCCQ overall summary score at 30 days (70.8) was sustained at 3 years (73.1).

Risk of death did not differ significantly according to the surgical valve size as labeled, the surgical valve true internal dimensions, the mode of valve failure, the approach used (transfemoral vs. transthoracic), or the residual gradient after valve implantation.

Analysis of the registry data is ongoing. For example, the investigators will be looking more closely at determinants of outcomes, such as additional characteristics of the surgical valve alone and in combination with those of the new valve. “We are all very aware that a lot of the outcomes have to do with what surgical valves you had to begin with. I think that is really critical – what surgical valve is in there,” he said.

Dr. Webb reported that he receives grant/research support and honoraria from, and is on the steering committee for, Edwards Lifesciences. The registry is sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2018

Key clinical point: Early improvements in functional status and quality of life measures with valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement are maintained longer term.

Major finding: Improvements at 30 days post procedure were maintained at 3 years post procedure; patients had similar distributions of New York Heart Association classes (for example, class I in 53.9% and 51.4%, respectively) and similar heart failure–related quality of life scores (70.8 vs. 73.1, P = .29).

Study details: A multicenter, prospective cohort study of 365 patients who underwent valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement because of a failing surgical aortic bioprosthetic valve.

Disclosures: Dr. Webb reported that he receives grant/research support and honoraria from, and is on the steering committee for Edwards Lifesciences. The registry is sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences.

Two novel approaches for infected ventral hernia mesh

BOSTON – Deep according to Cleveland Clinic investigators.

When infected mesh is removed, however, there’s a novel approach that avoids the pitfalls of both immediate and staged abdominal wall reconstruction, according to a second team from the Georgetown University, Washington.

The two approaches were offered at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgery as alternatives to usual care. Infected ventral hernia mesh is a well-known headache for general surgeons, and management isn’t standardized. Surgeons are keenly alert for new approaches to improve outcomes; the presenters said they hoped their talks would help.

The work “is really pushing this forward, and giving us new data to manage a really vexing problem,” said an audience member.

Almost 80% salvageable

Infected meshes are usually removed, but the Cleveland Clinic investigators found that that’s often not necessary.

They reviewed 905 elective ventral hernia repairs at the clinic with synthetic sublay mesh in the retrorectus space. The median hernia width was about 15 cm, and the implanted mesh – usually medium- or heavy-weight polypropylene – had a mean area of 900 cm2, “so these were big hernias with a lot of mesh. [Patients] often come to us as a last resort because they’ve been told no elsewhere,” said lead investigator Dominykas Burneikis, MD.

Twenty-four patients (2.7%) developed deep surgical site infections below the anterior rectus fascia. Instead of returning to the OR for new mesh, the team opened, drained, and debrided the wounds, and patients received antibiotics plus negative pressure wound therapy.

Those measures were enough for all but one patient. Mesh was generally found to be granulating well into surrounding tissue, so it was left completely intact in 19 cases (79%), and just trimmed a bit in four others. One man had an excision after his skin flap died and the hernia recurred. At 8 months, 11 patients were completely healed, and 12 had granulating wounds with no visible mesh. There were no cutaneous fistulas.

In short, “we had an 80% mesh salvage rate at 8 months, [which] led us to conclude that most synthetic mesh infections after retrorectus sublay repair do not require explanation,” Dr. Burneikis said.

A hybrid approach

When infected mesh does need to come out, abdominal wall reconstruction is either done in the same procedure or months later. Immediate reconstruction generally means operating in a contaminated field, with subsequent rates of wound infection of up to 48%. Delayed closure, meanwhile, means long-term wound care and temporary hernia recurrence, among other problems.

The Georgetown team reported good outcomes with a hybrid approach that combines the benefits of both procedures while avoiding their pitfalls. In the first step, mesh is removed, the abdominal wall debrided, fistulas taken down, and cultures obtained, explained lead investigator and surgery resident Kieranjeet Nijhar, MD.

The wound is temporarily closed with a sterile plastic liner under negative pressure, and patients are taken to the floor for IV antibiotics based on culture results. Three days later, after the infection has been knocked down, the patient is returned to the OR for debridement to healthy tissue and definitive reconstruction with biologic mesh. It’s all done during the same hospitalization.

Dr. Nijhar reviewed 53 cases at Georgetown since 2009. Patients were a mean age of 58 years, with an average body mass index of 35.1 kg/m2. Infected mesh was most commonly underlain or retrorectus; mean defect size was 206 cm2. Patients spent an average of 11 days in the hospital.

During a mean follow-up of about 9 months, 17 patients (32%) had surgical site problems – infection, dehiscence, hematoma, or seroma – and hernia recurred in six (11.3%); the results compare favorably with especially immediate reconstruction. As in prior studies, higher age and bridge repair were associated with recurrence and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection with surgical site problems.

“We propose this as a potential alternative for” repairs of ventral hernias with infected mesh, Dr. Nijhar said.

Dr. Nijhar and Dr. Burneikis had no relevant disclosures. There was no external funding for the work.

BOSTON – Deep according to Cleveland Clinic investigators.

When infected mesh is removed, however, there’s a novel approach that avoids the pitfalls of both immediate and staged abdominal wall reconstruction, according to a second team from the Georgetown University, Washington.

The two approaches were offered at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgery as alternatives to usual care. Infected ventral hernia mesh is a well-known headache for general surgeons, and management isn’t standardized. Surgeons are keenly alert for new approaches to improve outcomes; the presenters said they hoped their talks would help.