User login

New cholesterol, physical activity guidelines on tap at AHA 2018

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

AHA 3-day format syncs with new direction in scientific meetings

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

OV-101 shows promise for Angelman syndrome

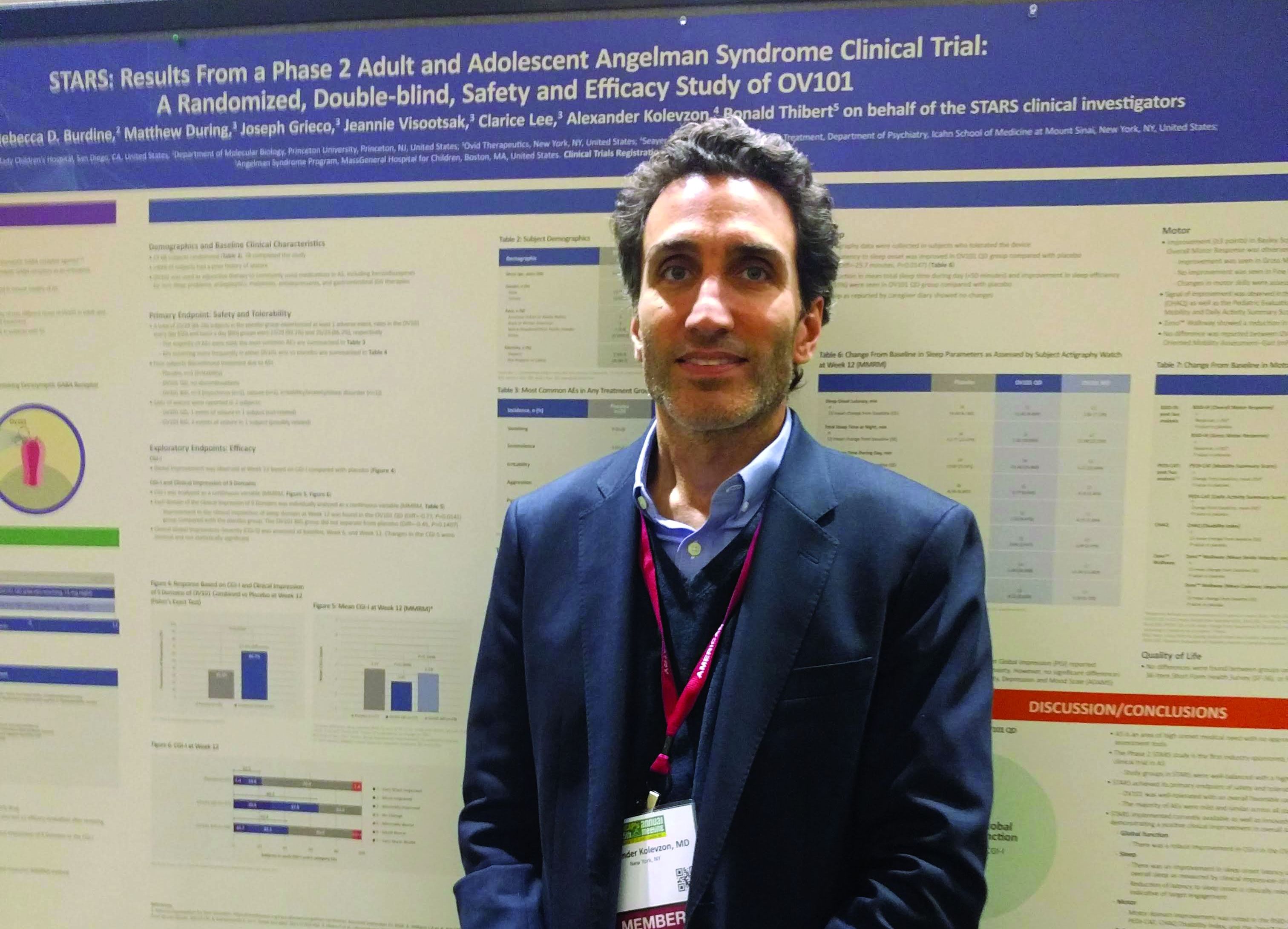

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Key clinical point: A new drug may improve sleep outcomes in Angelman Syndrome.

Major finding: Patients who received a single daily dose of OV-101 scored better than study participants given placebo on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale.

Study details: Randomized, controlled phase 2 trial (n = 88).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Ovid Therapeutics. Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for Ovid Therapeutics and several other drug companies.

Source: AACAP 2018 New Research Poster 3.1. .

Ligelizumab outperformed omalizumab for refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria

.

“For sure, ligelizumab is the highlight of this year in urticariology,” Marcus Maurer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. An ongoing phase 3 trial will now compare more than 1,000 patients with CSU who will be randomized to ligelizumab, omalizumab, or placebo.

Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, and this translated into greater therapeutic efficacy in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, explained Dr. Maurer, professor of dermatology and allergy at Charité University in Berlin.

Study participants, all refractory to histamine1 antihistamines and in many cases to leukotriene receptor antagonists as well, were randomized to omalizumab at 300 mg, placebo, or to ligelizumab at 24 mg, 72 mg, or 240 mg administered by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks for 20 weeks. The study showed that the effective dose of ligelizumab lies somewhere between 72 and 240 mg; the 24-mg dose won’t be pursued in further studies.

“Three things are important in the comparison between ligelizumab and omalizumab: First, ligelizumab works faster – and omalizumab is a fast-working drug in urticaria. As early as week 4 after initiation of treatment, ligelizumab resulted in a significantly higher response rate,” he said.

Second, a complete response rate as defined by an Urticaria Activity Score over the past 7 days (UAS7) of 0 was achieved by more than 50% of patients on ligelizumab at 240 mg, a rate twice that seen in the omalizumab group. Indeed, more patients were symptom-free on ligelizumab at 72 mg or 240 mg than on omalizumab throughout the 20-week study.

And third, time to relapse after treatment discontinuation was markedly longer with ligelizumab.

“Once you stop the treatment, we expect patients to come back because we didn’t cure the disease, we blocked the signs and symptoms by blocking mast cell degranulation. Relapse after the last injection occurred at about 4 weeks with omalizumab versus 10 weeks for ligelizumab on average. That’s amazing,” Dr. Maurer said.

At week 20, the mean reductions from baseline in UAS7 scores were 13.6 points with placebo, 15.2 points with the lowest dose of ligelizumab, 18.2 points with omalizumab, 23.1 points with ligelizumab at 72 mg, and 22.5 points for ligelizumab at 240 mg.

The side effect profiles for both biologics were essentially the same as for placebo with the exception of a 5.9% rate of mild injection site reactions with ligelizumab at the 240-mg dose versus 2.3% with placebo.

Many clinicians have noticed a significant limitation of omalizumab: It is less effective in patients with more complex CSU having an autoimmune overlay, type 2b angioedema, and/or long disease duration.

“This does not seem to be the case with ligelizumab. Even for the difficult-to-treat subpopulations of CSU, ligelizumab appears to be a drug that can protect against mast cell degranulation. We see a reduction in angioedema activity; we see a reduction in wheal size and number; we see a reduction in the itch – so across all the symptoms in the difficult subpopulations, this is the better drug. Now we have to make it work in the phase 3 trials to bring it to clinical practice,” he said.

Dr. Maurer reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to and paid speaker for Novartis, which markets omalizumab and is developing ligelizumab.

.

“For sure, ligelizumab is the highlight of this year in urticariology,” Marcus Maurer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. An ongoing phase 3 trial will now compare more than 1,000 patients with CSU who will be randomized to ligelizumab, omalizumab, or placebo.

Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, and this translated into greater therapeutic efficacy in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, explained Dr. Maurer, professor of dermatology and allergy at Charité University in Berlin.

Study participants, all refractory to histamine1 antihistamines and in many cases to leukotriene receptor antagonists as well, were randomized to omalizumab at 300 mg, placebo, or to ligelizumab at 24 mg, 72 mg, or 240 mg administered by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks for 20 weeks. The study showed that the effective dose of ligelizumab lies somewhere between 72 and 240 mg; the 24-mg dose won’t be pursued in further studies.

“Three things are important in the comparison between ligelizumab and omalizumab: First, ligelizumab works faster – and omalizumab is a fast-working drug in urticaria. As early as week 4 after initiation of treatment, ligelizumab resulted in a significantly higher response rate,” he said.

Second, a complete response rate as defined by an Urticaria Activity Score over the past 7 days (UAS7) of 0 was achieved by more than 50% of patients on ligelizumab at 240 mg, a rate twice that seen in the omalizumab group. Indeed, more patients were symptom-free on ligelizumab at 72 mg or 240 mg than on omalizumab throughout the 20-week study.

And third, time to relapse after treatment discontinuation was markedly longer with ligelizumab.

“Once you stop the treatment, we expect patients to come back because we didn’t cure the disease, we blocked the signs and symptoms by blocking mast cell degranulation. Relapse after the last injection occurred at about 4 weeks with omalizumab versus 10 weeks for ligelizumab on average. That’s amazing,” Dr. Maurer said.

At week 20, the mean reductions from baseline in UAS7 scores were 13.6 points with placebo, 15.2 points with the lowest dose of ligelizumab, 18.2 points with omalizumab, 23.1 points with ligelizumab at 72 mg, and 22.5 points for ligelizumab at 240 mg.

The side effect profiles for both biologics were essentially the same as for placebo with the exception of a 5.9% rate of mild injection site reactions with ligelizumab at the 240-mg dose versus 2.3% with placebo.

Many clinicians have noticed a significant limitation of omalizumab: It is less effective in patients with more complex CSU having an autoimmune overlay, type 2b angioedema, and/or long disease duration.

“This does not seem to be the case with ligelizumab. Even for the difficult-to-treat subpopulations of CSU, ligelizumab appears to be a drug that can protect against mast cell degranulation. We see a reduction in angioedema activity; we see a reduction in wheal size and number; we see a reduction in the itch – so across all the symptoms in the difficult subpopulations, this is the better drug. Now we have to make it work in the phase 3 trials to bring it to clinical practice,” he said.

Dr. Maurer reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to and paid speaker for Novartis, which markets omalizumab and is developing ligelizumab.

.

“For sure, ligelizumab is the highlight of this year in urticariology,” Marcus Maurer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. An ongoing phase 3 trial will now compare more than 1,000 patients with CSU who will be randomized to ligelizumab, omalizumab, or placebo.

Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, and this translated into greater therapeutic efficacy in the multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, explained Dr. Maurer, professor of dermatology and allergy at Charité University in Berlin.

Study participants, all refractory to histamine1 antihistamines and in many cases to leukotriene receptor antagonists as well, were randomized to omalizumab at 300 mg, placebo, or to ligelizumab at 24 mg, 72 mg, or 240 mg administered by subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks for 20 weeks. The study showed that the effective dose of ligelizumab lies somewhere between 72 and 240 mg; the 24-mg dose won’t be pursued in further studies.

“Three things are important in the comparison between ligelizumab and omalizumab: First, ligelizumab works faster – and omalizumab is a fast-working drug in urticaria. As early as week 4 after initiation of treatment, ligelizumab resulted in a significantly higher response rate,” he said.

Second, a complete response rate as defined by an Urticaria Activity Score over the past 7 days (UAS7) of 0 was achieved by more than 50% of patients on ligelizumab at 240 mg, a rate twice that seen in the omalizumab group. Indeed, more patients were symptom-free on ligelizumab at 72 mg or 240 mg than on omalizumab throughout the 20-week study.

And third, time to relapse after treatment discontinuation was markedly longer with ligelizumab.

“Once you stop the treatment, we expect patients to come back because we didn’t cure the disease, we blocked the signs and symptoms by blocking mast cell degranulation. Relapse after the last injection occurred at about 4 weeks with omalizumab versus 10 weeks for ligelizumab on average. That’s amazing,” Dr. Maurer said.

At week 20, the mean reductions from baseline in UAS7 scores were 13.6 points with placebo, 15.2 points with the lowest dose of ligelizumab, 18.2 points with omalizumab, 23.1 points with ligelizumab at 72 mg, and 22.5 points for ligelizumab at 240 mg.

The side effect profiles for both biologics were essentially the same as for placebo with the exception of a 5.9% rate of mild injection site reactions with ligelizumab at the 240-mg dose versus 2.3% with placebo.

Many clinicians have noticed a significant limitation of omalizumab: It is less effective in patients with more complex CSU having an autoimmune overlay, type 2b angioedema, and/or long disease duration.

“This does not seem to be the case with ligelizumab. Even for the difficult-to-treat subpopulations of CSU, ligelizumab appears to be a drug that can protect against mast cell degranulation. We see a reduction in angioedema activity; we see a reduction in wheal size and number; we see a reduction in the itch – so across all the symptoms in the difficult subpopulations, this is the better drug. Now we have to make it work in the phase 3 trials to bring it to clinical practice,” he said.

Dr. Maurer reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to and paid speaker for Novartis, which markets omalizumab and is developing ligelizumab.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Ligelizumab shows considerable promise for chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Major finding: The complete response rate was two times higher with ligelizumab than it was with omalizumab.

Study details: This phase 2b randomized, double-blind, multicenter, active- and placebo-controlled, 20-week study included 382 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to and paid speaker for Novartis, which is developing ligelizumab.

FDA approves adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

AGA is taking the lead in educating health care providers and patients about biosimilars and how they can be used for IBD patient care. Learn more at www.gastro.org/biosimilars.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

AGA is taking the lead in educating health care providers and patients about biosimilars and how they can be used for IBD patient care. Learn more at www.gastro.org/biosimilars.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) for a variety of conditions, according to Sandoz, the drug’s manufacturer and a division of Novartis.

FDA approval for Hyrimoz is based on a randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel biosimilarity study that demonstrated equivalence for all primary pharmacokinetic parameters, according to the press release. A second study confirmed these results in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with Hyrimoz having a safety profile similar to that of adalimumab. Hyrimoz was approved in Europe in July 2018.

Hyrimoz has been approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patients aged 4 years and older, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. The most common adverse events associated with the drug, according to the label, are infections, injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

Hyrimoz is the third adalimumab biosimilar approved by the FDA.

“Biosimilars can help people suffering from chronic, debilitating conditions gain expanded access to important medicines that may change the outcome of their disease. With the FDA approval of Hyrimoz, Sandoz is one step closer to offering U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases the same critical access already available in Europe,” Stefan Hendriks, global head of biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Novartis website.

AGA is taking the lead in educating health care providers and patients about biosimilars and how they can be used for IBD patient care. Learn more at www.gastro.org/biosimilars.

Epileptic Medications Linked to Stroke in Patients with Alzheimer Disease

Among people with Alzheimer Disease, the risk of developing a stroke is significantly greater if they are using antiepileptic drugs, according to a large study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

- The Medication Use and Alzheimer’s Disease cohort, which includes all the people in Finland who have been clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer disease (70,718) from 2005 to 2011, was analyzed to look for a correlation between the disease and antiepileptic drug use.

- Patients who had used the medications were about 37% more likely to have experienced a stroke, compared to nondrug users (hazard ratio [HR], 1.37).

- The likelihood of having a stroke in this patient population was greatest during the first 3 months of taking antiepileptic medication (HR, 2.36).

- The association between drug use and ischemic stroke was less than that observed between drug use and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.34 vs 1.44).

Sarycheva T, Lavikainen P, Taipale H, et al. Antiepileptic Drug Use and the Risk of Stroke Among Community-Dwelling People with Alzheimer Disease: A Matched Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7: e009742. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009742.

Among people with Alzheimer Disease, the risk of developing a stroke is significantly greater if they are using antiepileptic drugs, according to a large study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

- The Medication Use and Alzheimer’s Disease cohort, which includes all the people in Finland who have been clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer disease (70,718) from 2005 to 2011, was analyzed to look for a correlation between the disease and antiepileptic drug use.

- Patients who had used the medications were about 37% more likely to have experienced a stroke, compared to nondrug users (hazard ratio [HR], 1.37).

- The likelihood of having a stroke in this patient population was greatest during the first 3 months of taking antiepileptic medication (HR, 2.36).

- The association between drug use and ischemic stroke was less than that observed between drug use and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.34 vs 1.44).

Sarycheva T, Lavikainen P, Taipale H, et al. Antiepileptic Drug Use and the Risk of Stroke Among Community-Dwelling People with Alzheimer Disease: A Matched Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7: e009742. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009742.

Among people with Alzheimer Disease, the risk of developing a stroke is significantly greater if they are using antiepileptic drugs, according to a large study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

- The Medication Use and Alzheimer’s Disease cohort, which includes all the people in Finland who have been clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer disease (70,718) from 2005 to 2011, was analyzed to look for a correlation between the disease and antiepileptic drug use.

- Patients who had used the medications were about 37% more likely to have experienced a stroke, compared to nondrug users (hazard ratio [HR], 1.37).

- The likelihood of having a stroke in this patient population was greatest during the first 3 months of taking antiepileptic medication (HR, 2.36).

- The association between drug use and ischemic stroke was less than that observed between drug use and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.34 vs 1.44).

Sarycheva T, Lavikainen P, Taipale H, et al. Antiepileptic Drug Use and the Risk of Stroke Among Community-Dwelling People with Alzheimer Disease: A Matched Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7: e009742. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009742.

Treatment Options for Pilonidal Sinus

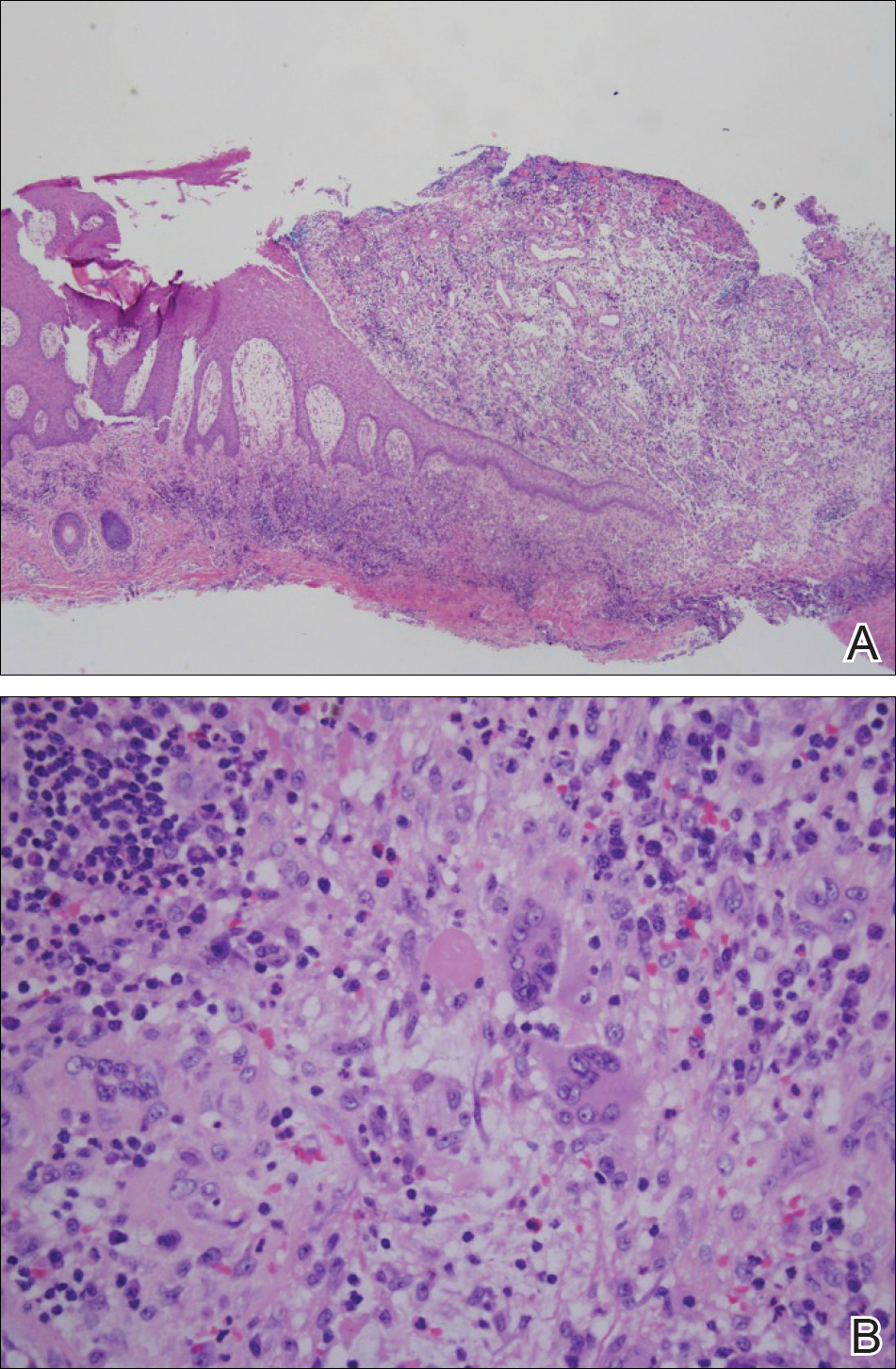

Pilonidal disease was first described by Mayo1 in 1833 who hypothesized that the underlying etiology is incomplete separation of the mesoderm and ectoderm layers during embryogenesis. In 1880, Hodges2 coined the term pilonidal sinus; he postulated that sinus formation was incited by hair.2 Today, Hodges theory is known as the acquired theory: hair induces a foreign body response in surrounding tissue, leading to sinus formation. Although pilonidal cysts can occur anywhere on the body, they most commonly extend cephalad in the sacrococcygeal and upper gluteal cleft (Figure 1).3,4 An acute pilonidal cyst typically presents with pain, tenderness, and swelling, similar to the presentation of a superficial abscess in other locations; however, a clue to the diagnosis is the presence of cutaneous pits along the midline of the gluteal cleft.5 Chronic pilonidal disease varies based on the extent of inflammation and scarring; the underlying cavity communicates with the overlying skin through sinuses and often drains with pressure.6

Pilonidal sinuses are rare before puberty or after 40 years of age7 and occur primarily in hirsute men. The ratio of men to women affected is between 3:1 and 4:1.8 Although pilonidal sinuses account for only 15% of anal suppurations, complications arising from pilonidal sinuses are a considerable cause of morbidity, resulting in loss of productivity in otherwise healthy individuals.9 Complications include chronic nonhealing wounds,10 as recurrent pilonidal sinuses tend to become colonized with gram-positive and facultative anaerobic bacteria, whereas primary pilonidal cysts more commonly become infected with anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria.11 Long-standing disease increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma arising within sinus tracts.10,12

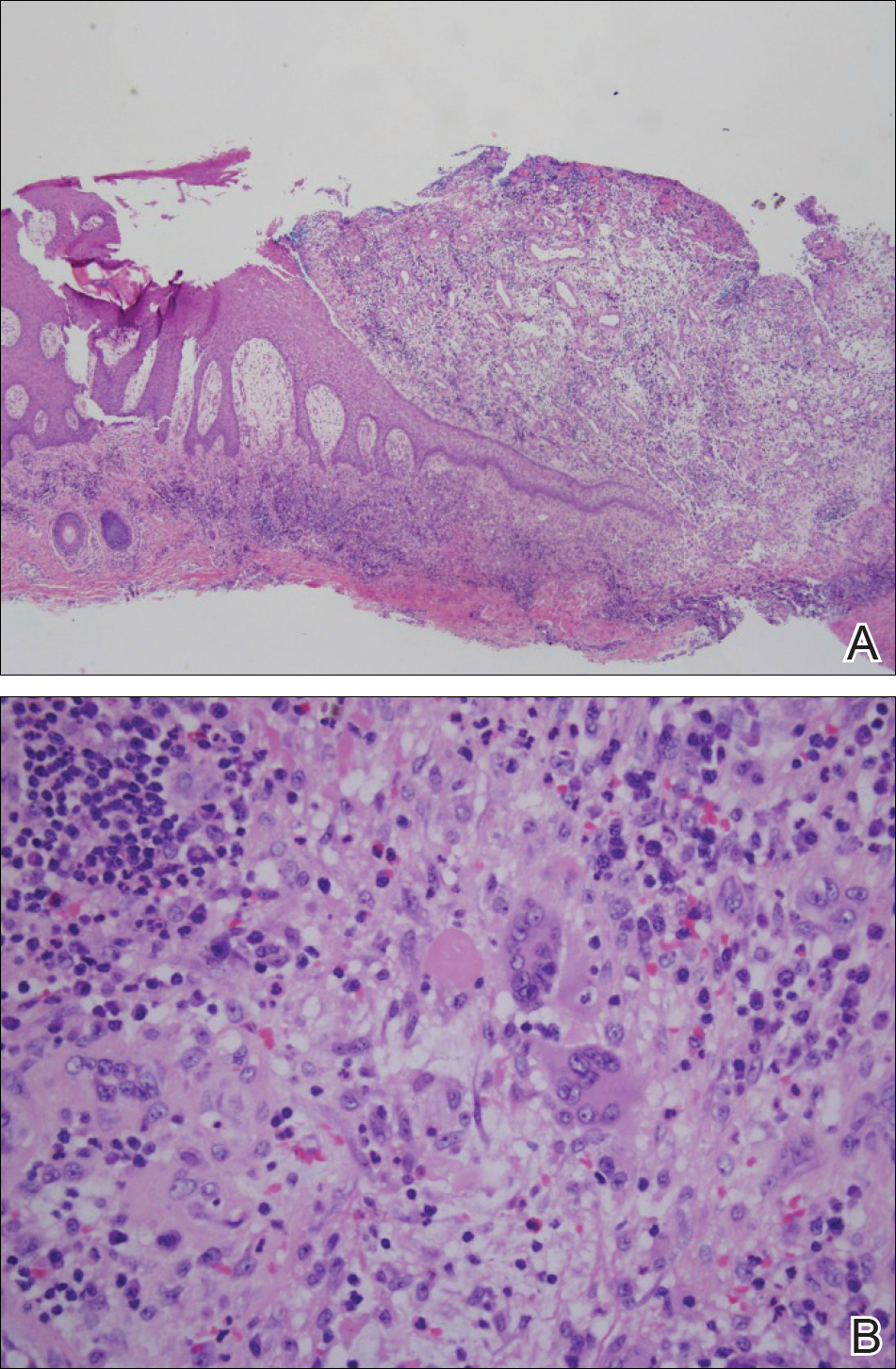

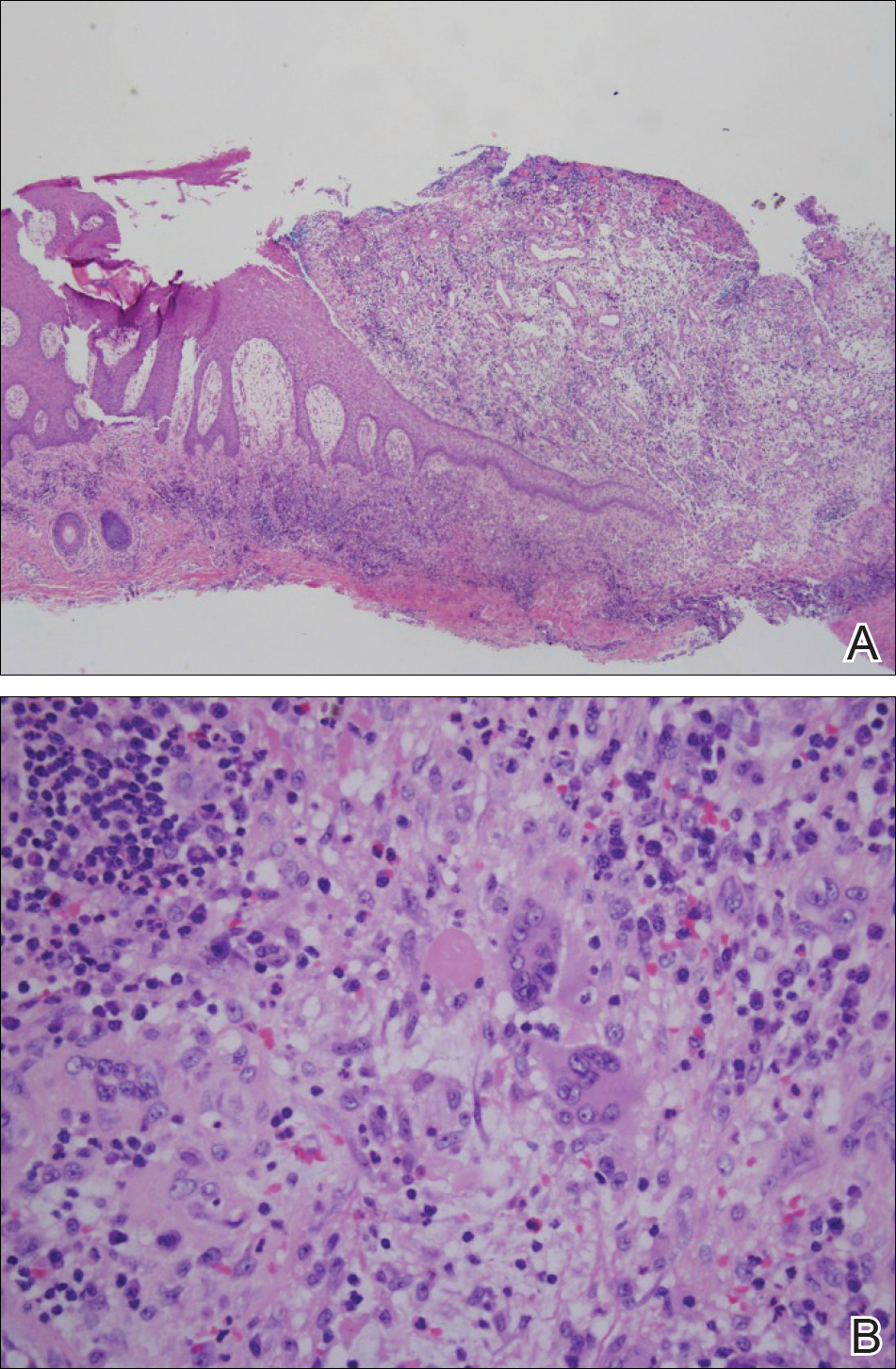

Histopathologically, pilonidal cysts are not true cysts because they lack an epithelial lining. Examination of the cavity commonly reveals hair, debris, and granulation tissue with surrounding foreign-body giant cells (Figure 2).5

The preferred treatment of pilonidal cysts continues to be debated. In this article, we review evidence supporting current modalities including conservative and surgical techniques as well as novel laser therapy for the treatment of pilonidal disease.

Conservative Management Techniques

Phenol Injections

Liquid or crystallized phenol injections have been used for treatment of mild to moderate pilonidal cysts.13 Excess debris is removed by curettage, and phenol is administered through the existing orifices or pits without pressure. The phenol remains in the cavity for 1 to 3 minutes before aspiration. Remaining cyst contents are removed through tissue manipulation, and the sinus is washed with saline. Mean healing time is 20 days (range, +/−14 days).13

Classically, phenol injections have a failure rate of 30% to 40%, especially with multiple sinuses and suppurative disease6; however, the success rate improves with limited disease (ie, no more than 1–3 sinus pits).3 With multiple treatment sessions, a recurrence rate as low as 2% over 25 months has been reported.14 Phenol injection also has been proposed as an adjuvant therapy to pit excision to minimize the need for extensive surgery.15

Simple Incision and Drainage

Simple incision and drainage has a crucial role in the treatment of acute pilonidal disease to decrease pain and relieve tension. Off-midline incisions have been recommended for because the resulting closures fared better against sheer forces applied by the gluteal muscles on the cleft.6 Therefore, the incision often is made off-midline from the gluteal cleft even when the cyst lies directly on the gluteal cleft.

Rates of healing vary widely after incision and drainage, ranging from 45% to 82%.6 Primary pilonidal cysts may respond well, particularly if the cavity is abraded; in one series, 79% (58/73) of patients did not have a recurrence at the average follow-up of 60 months.16

Excision and Unroofing

Techniques for excision and unroofing without primary closure include 2 variants: wide and limited. The wide technique consists of an inwardly slanted excision that is deepest in the center of the cavity. The inward sloping angle of the incision aids in healing because it allows granulation to progress evenly from the base of the wound upward. The depth of the incision should spare the fascia and leave as much fatty tissue as possible while still resecting the entire cavity and associated pits.6 Limited incision techniques aim to shorten the healing period by making smaller incisions into the sinuses, pits, and secondary tracts, and they are frequently supplemented with curettage.6 Noteworthy disadvantages include prolonged healing time, need for professional wound management, and extended medical observation.5 The average duration of wound healing in a study of 300 patients was 5.4 weeks (range, +/−1.1 weeks),17 and the recurrence rate has ranged from 5% to 13%.18,19 Care must be taken to respond to numerous possible complications, including excessive exudation and granulation, superinfection, and walling off.6

Although the cost of treatment varies by hospital, location, and a patient’s insurance coverage, patient reports to the Pilonidal Support Alliance indicate that the cost of conservative management ranges from $500 to $2000.20

Excision and Primary Closure

An elliptical excision that includes some of the lateral margin is excised down to the level of the fascia. Adjacent lateral tracts may be excised by expanding the incision. To close the wound, edges are approximated with placement of deep and superficial sutures. Wound healing typically occurs faster than secondary granulation, as seen in one randomized controlled trial with a mean of 10 days for primary closure compared to 13 weeks for secondary intention.21 However, as with any surgical procedure, postoperative complications can delay wound healing.19 The recurrence rate after primary closure varies considerably, ranging from 10% to 38%.18,21-23 The average cost of an excision ranges from $3000 to $6000.20

A

Surgical Techniques

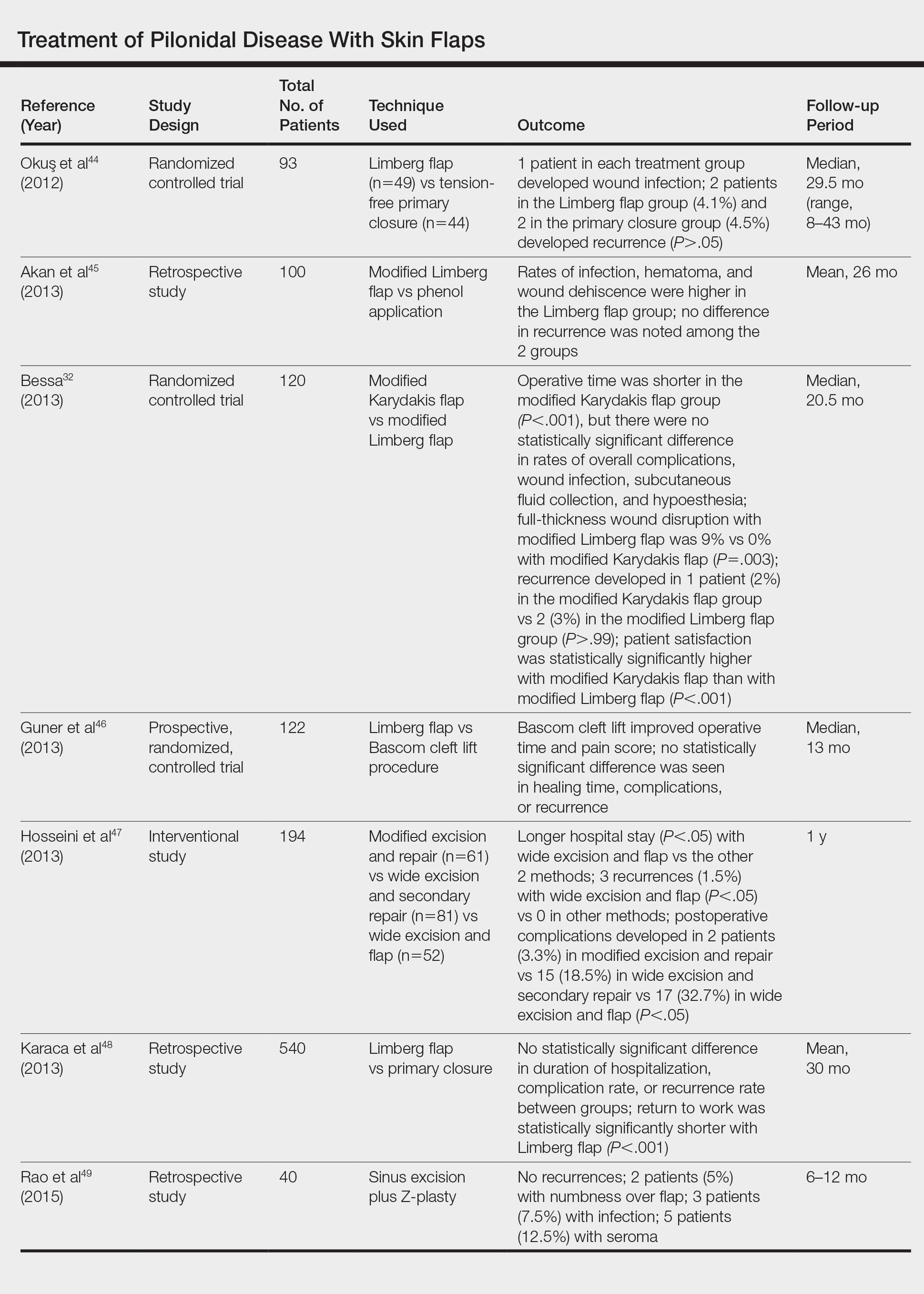

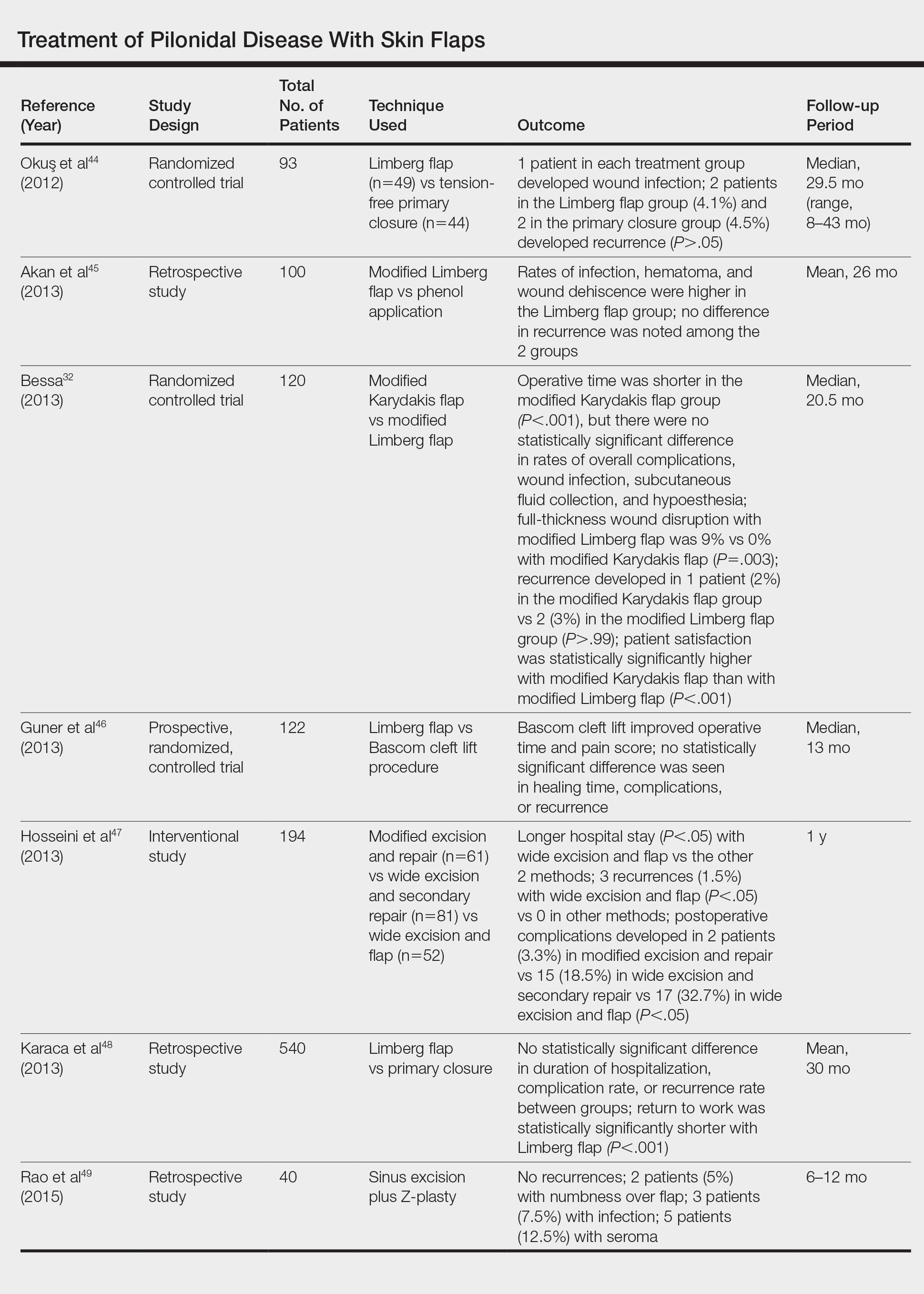

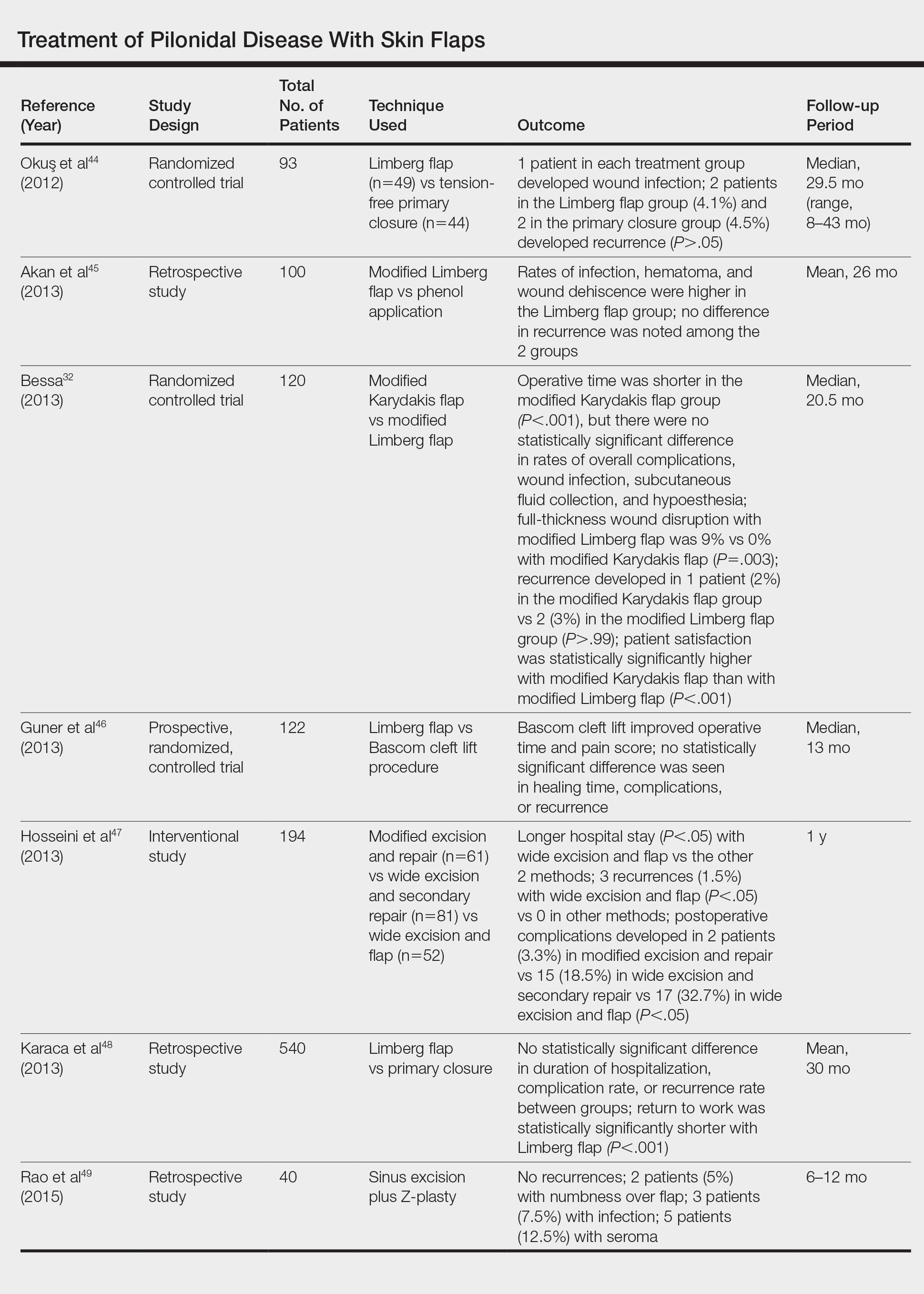

For severe or recurrent pilonidal disease, skin flaps often are required. Several flaps have been developed, including advancement, Bascom cleft lift, Karydakis, and modified Limberg flap. Flaps require a vascular pedicle but allow for closure without tension.26 The cost of a flap procedure, ranging from $10,000 to $30,000, is greater than the cost of excision or other conservative therapy20; however, with a lower recurrence rate of pilonidal disease following flap procedures compared to other treatments, patients may save more on treatment over the long-term.

Advancement Flaps

The most commonly used advancement flaps are the V-Y advancement flap and Z-plasty. The V-Y advancement flap creates a full-thickness V-shaped incision down to gluteal fascia that is closed to form a postrepair suture line in the shape of a Y.5 Depending on the size of the defect, the flaps may be utilized unilaterally or bilaterally. A defect as large as 8 to 10 cm can be covered unilaterally; however, defects larger than 10 cm commonly require a bilateral flap.26 The V-Y advancement flap failed to show superiority to primary closure techniques based on complications, recurrence, and patient satisfaction in a large randomized controlled trial.27

Performing a Z-plasty requires excision of diseased tissue with recruitment of lateral flaps incised down to the level of the fascia. The lateral edges are transposed to increase transverse length.26 No statistically significant difference in infection or recurrence rates was noted between excision alone and excision plus Z-plasty; however, wounds were reported to heal faster in patients receiving excision plus Z-plasty (41 vs 15 days).28

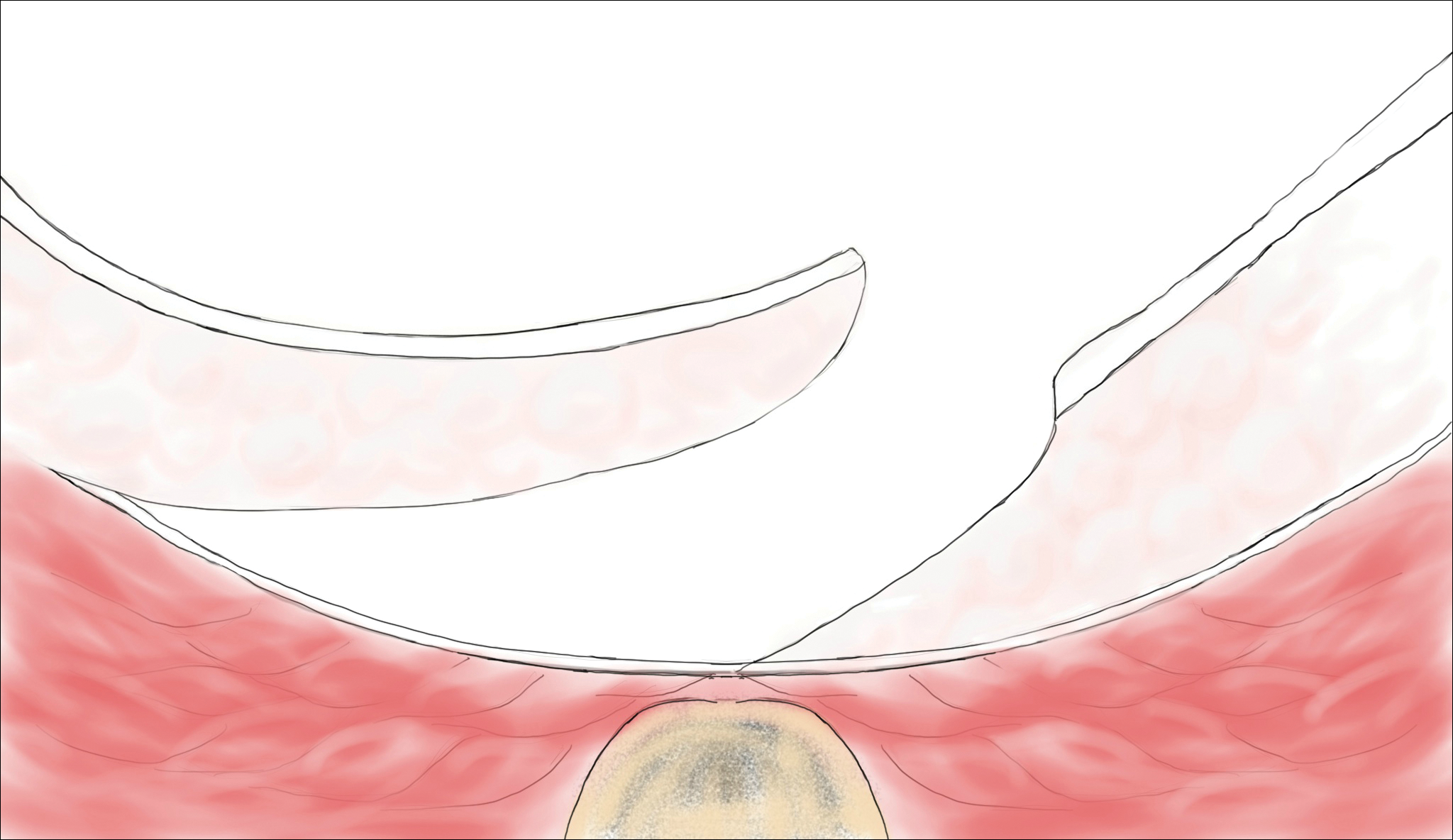

Cleft Lift Closure

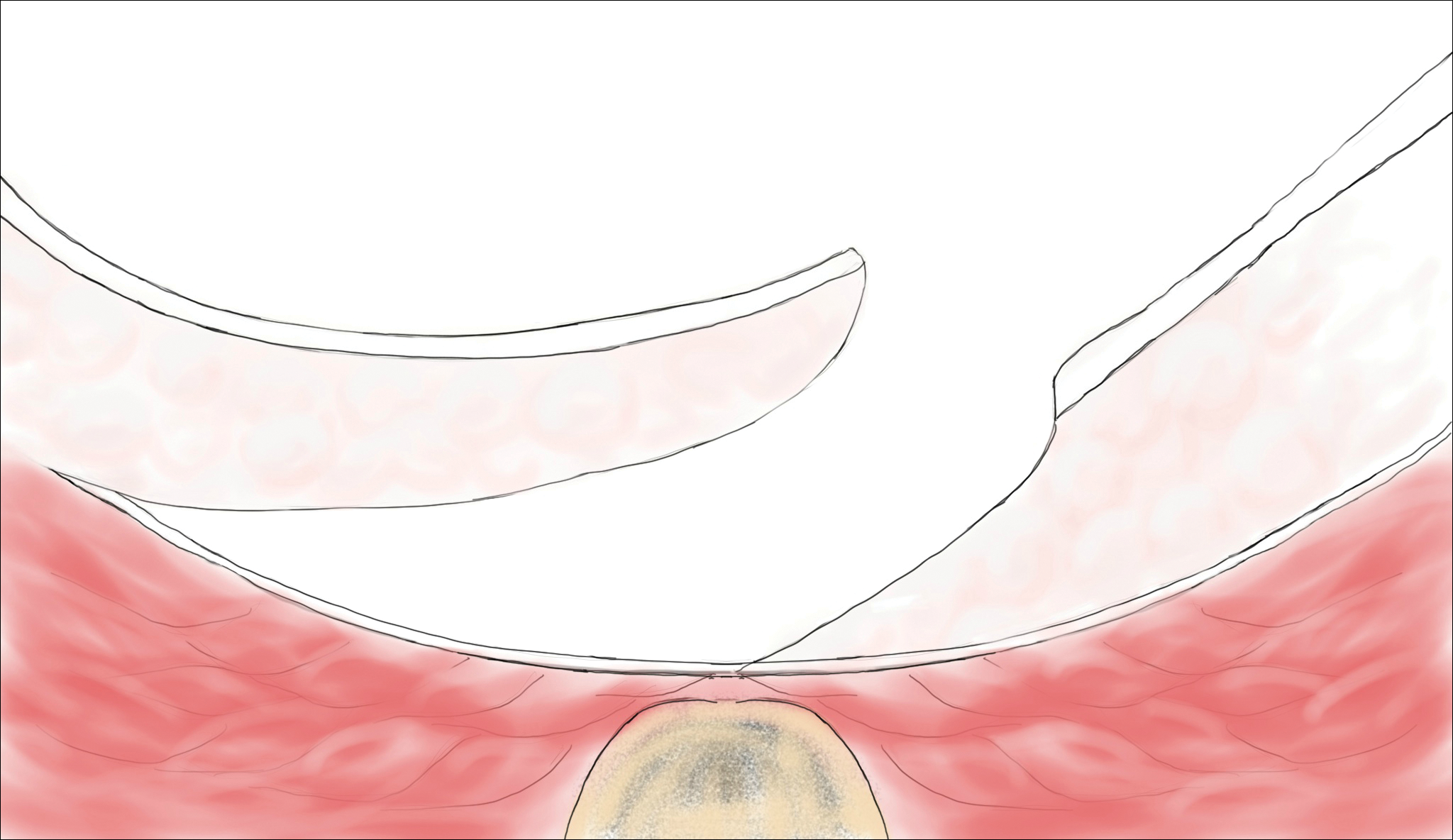

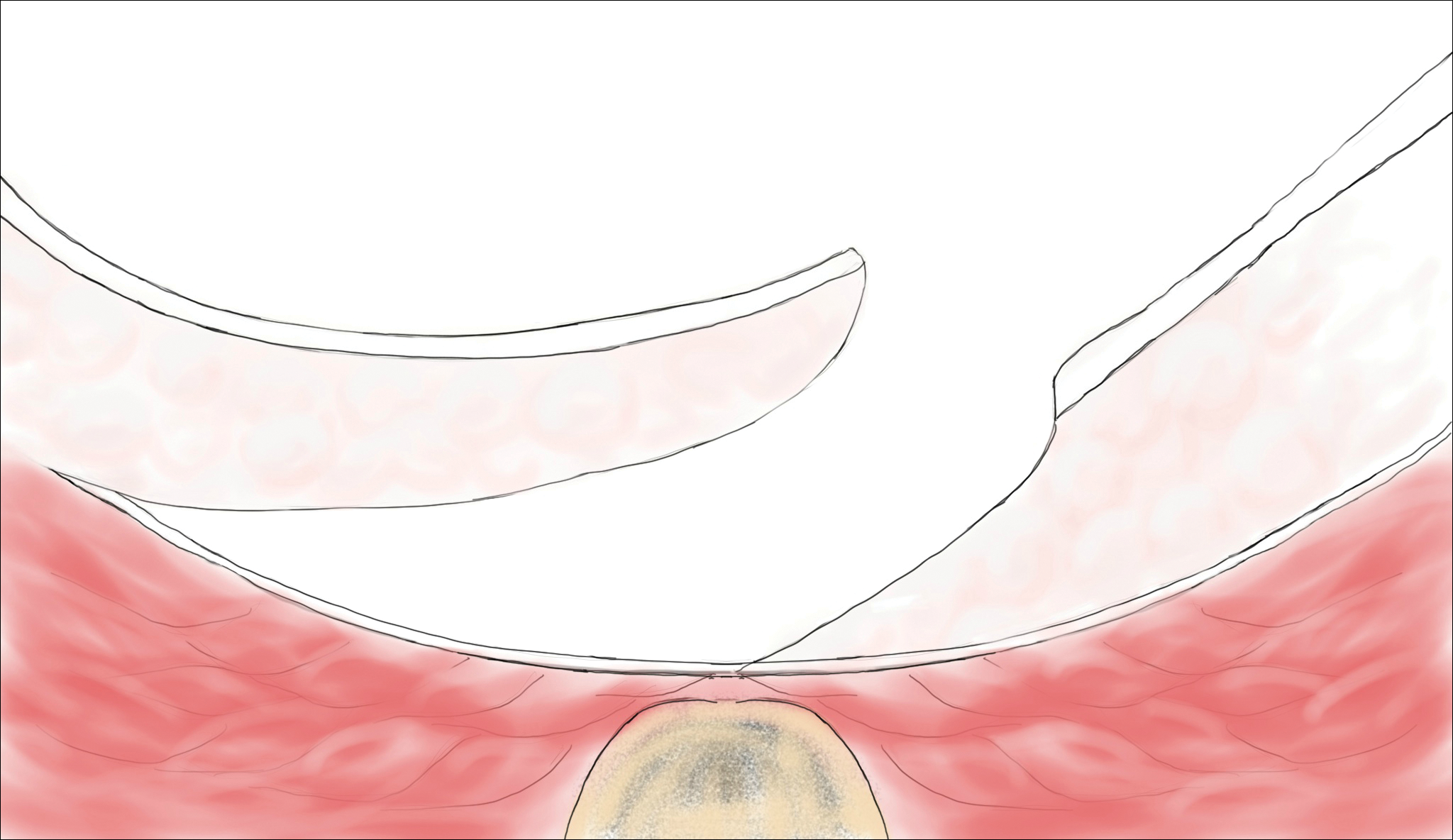

In 1987, Bascom29 introduced the cleft lift closure for recurrent pilonidal disease. This technique aims to reduce or eliminate lateral gluteal forces on the wounds by filling the gluteal cleft.5 The sinus tracts are excised and a full-thickness skin flap is extended across the cleft and closed off-midline. The adipose tissue fills in the previous space of the gluteal cleft. In the initial study, no recurrences were reported in 30 patients who underwent this procedure at 2-year follow-up; similarly, in another case series of 26 patients who underwent the procedure, no recurrences were noted at a median follow-up of 3 years.30 Compared to excision with secondary wound healing and primary closure on the midline, the Bascom cleft lift demonstrated a decrease in wound healing time (62, 52, and 29 days, respectively).31

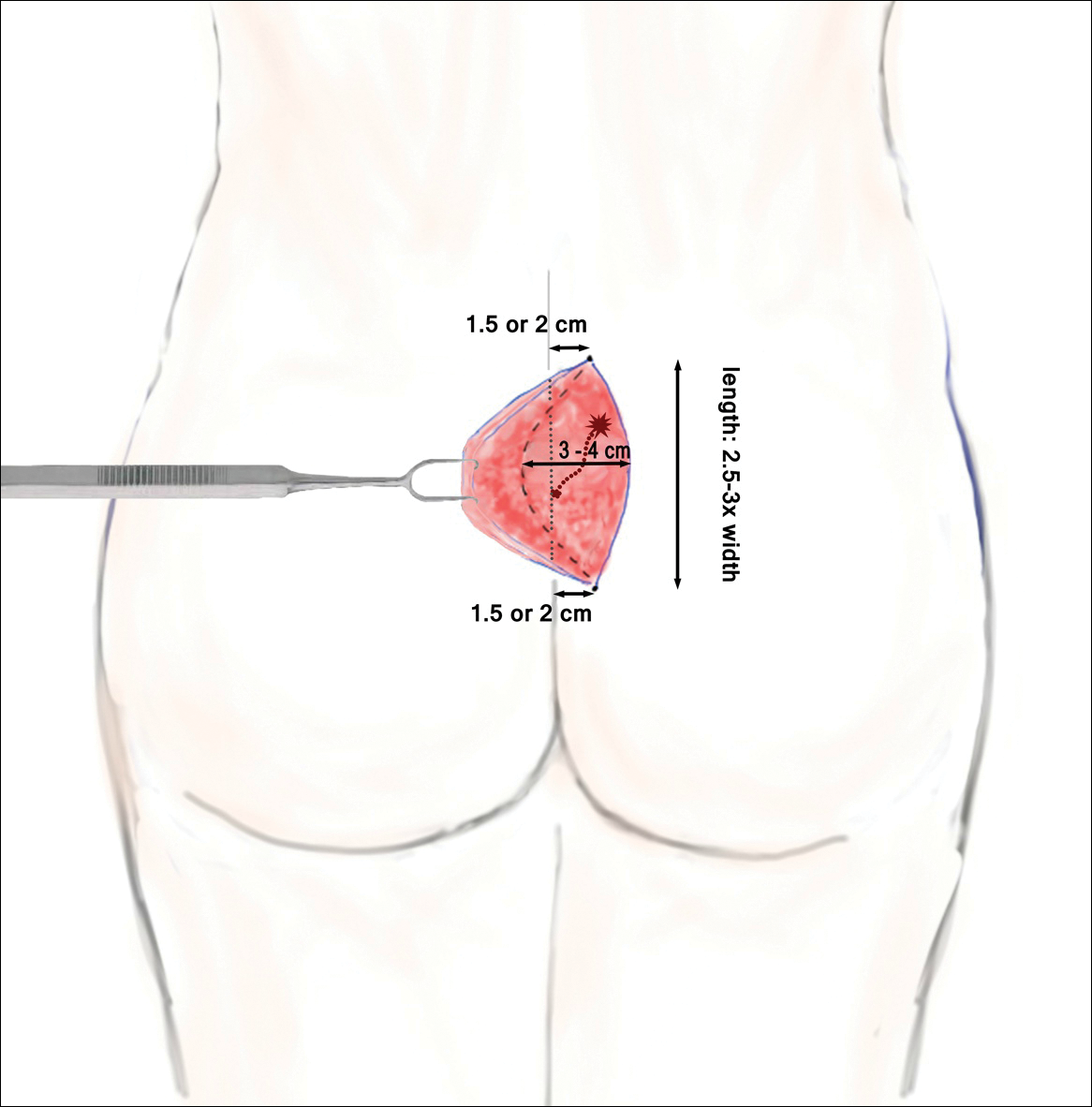

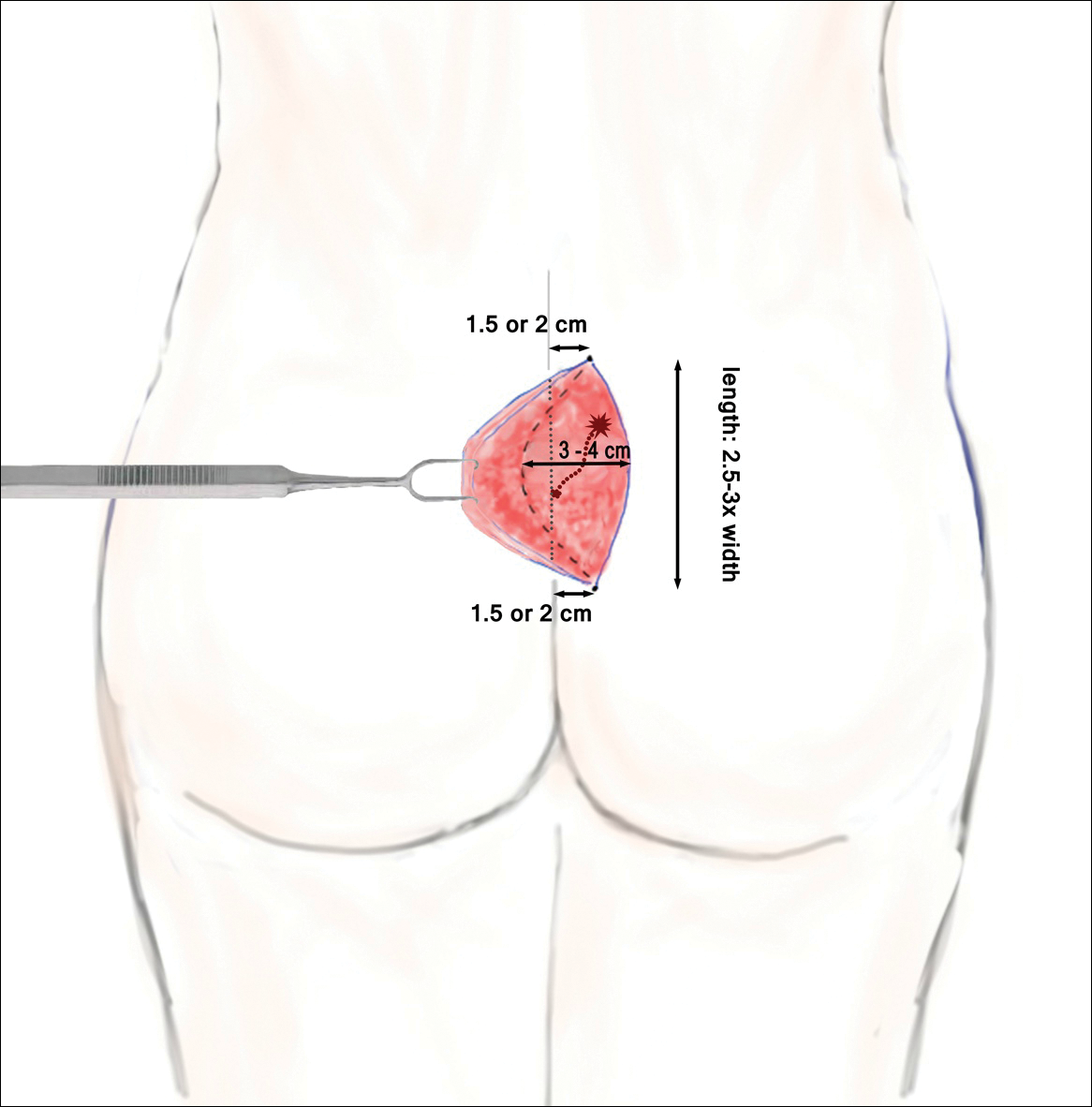

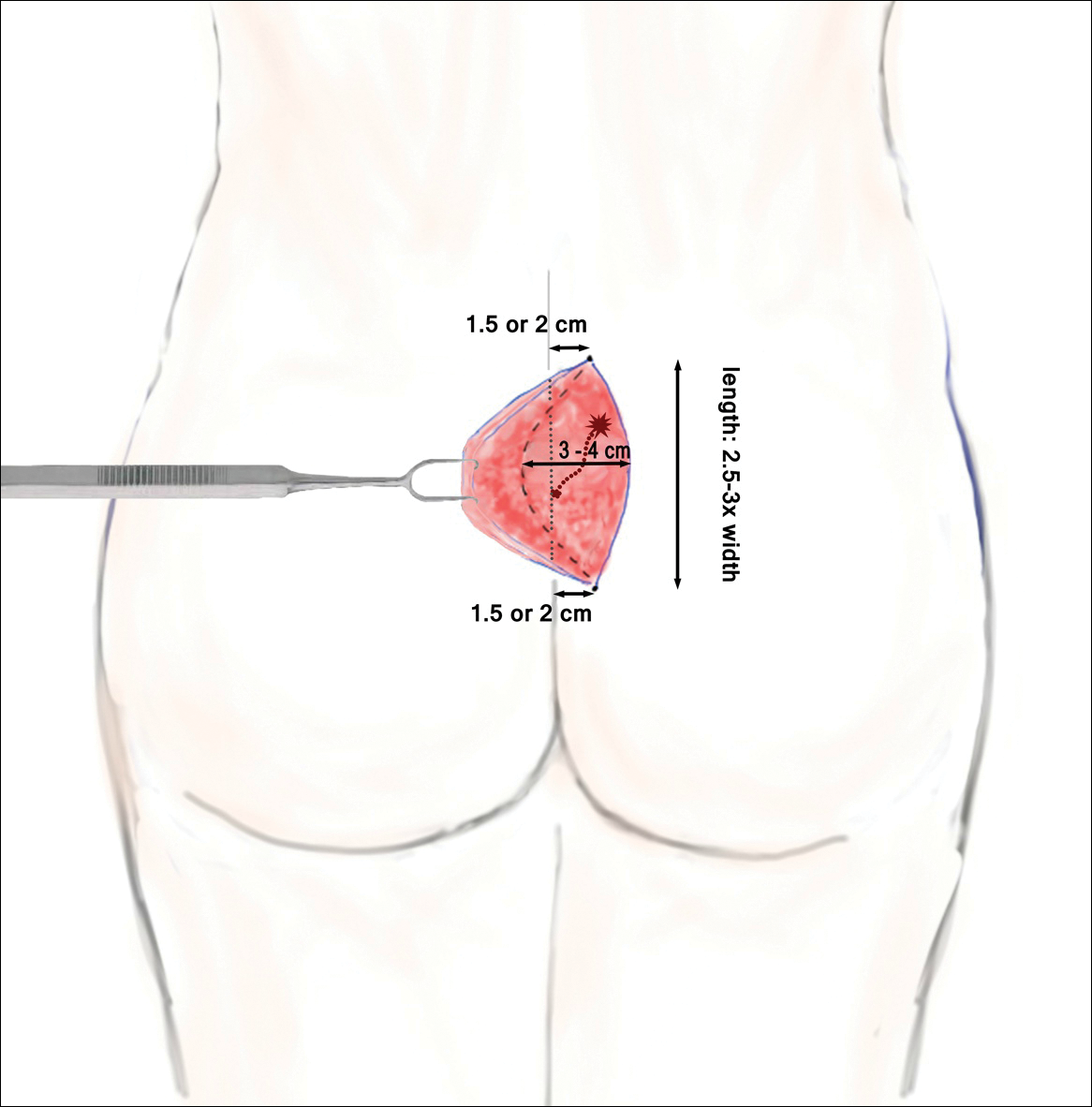

The classic Karydakis flap consists of an oblique elliptical excision of diseased tissue with fixation of the flap base to the sacral fascia (Figures 4 and 5). The flap is closed by suturing the edge off-midline.32 This technique prevents a midline wound and aims to remodel and flatten the natal cleft. Karydakis33 performed the most important study for treatment of pilonidal disease with the Karydakis flap, which included more than 5000 patients. The results showed a 0.9% recurrence rate and an 8.5% wound complication rate over a 2- to 20-year follow-up.33 These results have been substantiated by more recent studies, which produced similar results: a 1.8% to 5.3% infection rate and a recurrence rate of 0.9% to 4.4%.34,35

In the modified Karydakis flap, the same excision and closure is performed without tacking the flap to the sacral fascia, aiming to prevent formation of a new vulnerable raphe by flattening the natal cleft. The infection rate was similar to the classic Karydakis flap, and no recurrences were noted during a 20-month follow-up.36

Limberg Flap

The Limberg flap is derived from a rhomboid flap. In the classic Limberg flap, a midline rhomboid incision to the presacral fascia including the sinus is performed. The flap gains mobility by extending the excision laterally to the fascia of the gluteus maximus muscle. A variant of the original flap includes the modified Limberg flap, which lateralizes the midline sutures and flattens the intergluteal sulcus. Compared to the traditional Limberg approach, the modified Limberg flap was associated with a lower failure rate at both early and late time points and a lower rate of infection37,38; however, based on the data it is unclear when primary closure should be favored over a Limberg flap. Several studies show the recurrence rate to be identical; however, hospital stay and pain were reduced in the Limberg flap group compared to primary closure.39,40

Results from randomized controlled trials comparing the modified Limberg flap to the Karydakis flap vary. One of the largest prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing the 2 flaps included 269 patients.Results showed a lower postoperative complication rate, lower pain scores, shorter operation time, and shorter hospital stay with the Karydakis flap compared to the Limberg flap, though no difference in recurrence was noted between the 2 groups.41

Tw

Overall, larger prospective trials are needed to clarify the differences in outcomes between flap techniques. In

Laser Therapy

Lasers are emerging as primary and adjuvant treatment options for pilonidal sinuses. Depilation with alexandrite, diode, and Nd:YAG lasers has demonstrated the most consistent evidence.50-54 Th

Large randomized controlled trials are needed to fully determine the utility of laser therapy as a primary or adjuvant treatment in pilonidal disease; however, given that laser therapies address the core pathogenesis of pilonidal disease and generally are well tolerated, their use may be strongly considered.

Conclusion

With mild pilonidal disease, more conservative measures can be employed; however, in cases of recurrent or suppurative disease or extensive scarring, excision with flap closure typically is required. Although no single surgical procedure has been identified as superior, one review demonstrated that off-midline procedures are statistically superior to midline closure in healing time, surgical site infection, and recurrence rate.24 Novel techniques continue to emerge in the management of pilonidal disease, including laser therapy. This modality shows promise as either a primary or adjuvant treatment; however, large randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm early findings.

Given that pilonidal disease most commonly occurs in the actively employed population, we recommend that dermatologic surgeons discuss treatment options with patients who have pilonidal disease, taking into consideration cost, length of hospital stay, and recovery time when deciding on a treatment course.

- Mayo OH. Observations on Injuries and Diseases of the Rectum. London, England: Burgess and Hill; 1833.

- Hodges RM. Pilonidal sinus. Boston Med Surg J. 1880;103:485-486.

- Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Ozkan OV, et al. Interdigital pilonidal sinus: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1400-1403.

- Stone MS. Cysts with a lining of stratified epithelium. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Limited; 2012:1917-1929.

- Khanna A, Rombeau JL. Pilonidal disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:46-53.

- de Parades V, Bouchard D, Janier M, et al. Pilonidal sinus disease. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:237-247.

- Harris CL, Laforet K, Sibbald RG, et al. Twelve common mistakes in pilonidal sinus care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:325-332.

- Lindholt-Jensen C, Lindholt J, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG laser treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Oueidat D, Rizkallah A, Dirani M, et al. 25 years’ experience in the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Open J Gastro. 2014;4:1-5.

- Gordon P, Grant L, Irwin T. Recurrent pilonidal sepsis. Ulster Med J. 2014;83:10-12.

- Ardelt M, Dittmar Y, Kocijan R, et al. Microbiology of the infected recurrent sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Int Wound J. 2016;13:231-237.

- Eryilmaz R, Bilecik T, Okan I, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma arising in a neglected pilonidal sinus: report of a case and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:446-450.

- Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Review of phenol treatment in sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:189-193.

- Dag A, Colak T, Turkmenoglu O, et al. Phenol procedure for pilonidal sinus disease and risk factors for treatment failure. Surgery. 2012;151:113-117.

- Olmez A, Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Treatment of pilonidal disease by combination of pit excision and phenol application. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:201-206.

- Jensen SL, Harling H. Prognosis after simple incision and drainage for a first-episode acute pilonidal abscess. Br J Surg. 1988;75:60-61.

- Kepenekci I, Demirkan A, Celasin H, et al. Unroofing and curettage for the treatment of acute and chronic pilonidal disease. World J Surg. 2010;34:153-157.

- Søndenaa K, Nesvik I, Anderson E, et al. Recurrent pilonidal sinus after excision with closed or open treatment: final results of a randomized trial. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:237-240.

- Spivak H, Brooks VL, Nussbaum M, et al. Treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1136-1139.

- Pilonidal surgery costs. Pilonidal Support Alliance website. https://www.pilonidal.org/treatments/surgical-costs/. Updated January 30, 2016. Accessed October 14, 2018.21. al-Hassan HK, Francis IM, Neglén P. Primary closure or secondary granulation after excision of pilonidal sinus? Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:695-699.

- Khaira HS, Brown JH. Excision and primary suture of pilonidal sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:242-244.

- Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the post anal (pilonidal) sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:201-203.

- Al-Khamis A, McCallum I, King PM, et al. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD006213.

- McCallum I, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:868-871.

- Lee PJ, Raniga S, Biyani DK, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Colorect Dis. 2008;10:639-650.

- Nursal TZ, Ezer A, Calişkan K, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing V-Y advancement flaps with primary suture methods in pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;199:170-177.

- Fazeli MS, Adel MG, Lebaschi AH. Comparison of outcomes in Z-plasty and delayed healing by secondary intention of the wound after excision in the sacral pilonidal sinus: results of a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Col Rectum. 2006;49:1831-1836.

- Bascom JU. Repeat pilonidal operations. Am J Surg. 1987;154:118-122.

- Nordon IM, Senapati A, Cripps NP. A prospective randomized controlled trial of simple Bascom’s technique versus Bascom’s cleft closure in the treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2009;197:189-192.

- Dudnik R, Veldkamp J, Nienhujis S, et al. Secondary healing versus midline closure and modified Bascom natal cleft lift for pilonidal sinus disease. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:110-113.

- Bessa SS. Comparison of short-term results between the modified Karydakis flap and the modified Limberg flap in the management of pilonidal sinus disease: a randomized controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:491-498.

- Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:385-389.

- Kitchen PR. Pilonidal sinus: excision and primary closure with a lateralised wound - the Karydakis operation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1982;52:302-305.

- Akinci OF, Coskun A, Uzunköy A. Simple and effective surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus: asymmetric excision and primary closure using suction drain and subcuticular skin closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:701-706.

- Bessa SS. Results of the lateral advancing flap operation (modified Karydakis procedure) for the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1935-1940.

- Mentes BB, Leventoglu S, Chin A, et al. Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Surg Today. 2004;34:419-423.

- Cihan A, Ucan BH, Comert M, et al. Superiority of asymmetric modified Limberg flap for surgical treatment of pilonidal cyst disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:244-249.

- Muzi MG, Milito G, Cadeddu F, et al. Randomized comparison of Limberg flap versus modified primary closure for treatment of pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:9-14.

- Tavassoli A, Noorshafiee S, Nazarzadeh R. Comparison of excision with primary repair versus Limberg flap. Int J Surg. 2011;9:343-346.

- Ates M, Dirican A, Sarac M, et al. Short and long-term results of the Karydakis flap versus the Limberg flap for treating pilonidal sinus disease: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2011;202:568-573.

- Can MF, Sevinc MM, Hancerliogullari O, et al. Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with saccrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:318-327.

- Ersoy E, Devay AO, Aktimur R, et al. Comparison of short-term results after Limberg and Karydakis procedures for pilonidal disease: randomized prospective analysis of 100 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:705-710.

- Okuş A, Sevinç B, Karahan O, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and tension-free primary closure during pilonidal sinus surgery. World J Surg. 2012;36:431-435.

- Akan K, Tihan D, Duman U, et al. Comparison of surgical Limberg flap technique and crystallized phenol application in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a retrospective study. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2013;29:162-166.

- Guner A, Boz A, Ozkan OF, et al. Limberg flap versus Bascom cleft lift techniques for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: prospective, randomized trial. World J Surg. 2013;37:2074-2080.

- Hosseini H, Heidari A, Jafarnejad B. Comparison of three surgical methods in treatment of patients with pilonidal sinus: modified excision and repair/wide excision/wide excision and flap in RASOUL, OMID and SADR hospitals (2004-2007). Indian J Surg. 2013;75:395-400.

- Karaca AS, Ali R, Capar M, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease, in terms of quality of life and complications. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:236-239.

- Rao J, Deora H, Mandia R. A retrospective study of 50 cases of pilonidal sinus with excision of tract and Z-plasty as treatment of choice for both primary and recurrent cases. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(suppl 2):691-693.

- Landa N, Aller O, Landa-Gundin N, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent pilonidal sinus with laser epilation. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:726-728.

- Oram Y, Kahraman D, Karincaoğlu Y, et al. Evaluation of 60 patients with pilonidal sinus treated with laser epilation after surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:88-91.

- Benedetto AV, Lewis AT. Pilonidal sinus disease treated by depilation using an 800 nm diode laser and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:587-591.

- Lindholt-Jensen CS, Lindholt JS, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Jain V, Jain A. Use of lasers for the management of refractory cases of hidradenitis suppurativa and pilonidal sinus. J Cutan Aesthet. 2012;5:190-192.