User login

CHMP recommends generic deferiprone

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Deferiprone Lipomed to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major.

Deferiprone Lipomed is a generic version of the iron chelating agent Ferriprox, which has been authorized in the European Union since August 1999.

According to the CHMP, studies have shown that Deferiprone Lipomed is of satisfactory quality and bioequivalent to Ferriprox.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Deferiprone Lipomed will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Deferiprone Lipomed will be available as 500-mg film-coated tablets.

The drug will be authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major when current chelation therapy is contraindicated or inadequate

- In combination with another chelator in patients with thalassemia major when monotherapy with any iron chelator is ineffective or when prevention or treatment of life-threatening consequences of iron overload justifies rapid or intensive correction.

According to the prescribing information for Ferriprox, the combination of iron chelators should be considered on a case-by-case basis, and patients should be monitored for response and adverse events.

Fatalities and life-threatening situations (caused by agranulocytosis) have been reported with the combination of deferiprone and deferoxamine.

Combination therapy is not recommended when monotherapy with either chelator is adequate or when serum ferritin falls below 500 μg/l. Additionally, there are limited data on the combined use of Ferriprox and deferasirox.

The applicant for Deferiprone Lipomed is Lipomed GmbH.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Deferiprone Lipomed to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major.

Deferiprone Lipomed is a generic version of the iron chelating agent Ferriprox, which has been authorized in the European Union since August 1999.

According to the CHMP, studies have shown that Deferiprone Lipomed is of satisfactory quality and bioequivalent to Ferriprox.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Deferiprone Lipomed will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Deferiprone Lipomed will be available as 500-mg film-coated tablets.

The drug will be authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major when current chelation therapy is contraindicated or inadequate

- In combination with another chelator in patients with thalassemia major when monotherapy with any iron chelator is ineffective or when prevention or treatment of life-threatening consequences of iron overload justifies rapid or intensive correction.

According to the prescribing information for Ferriprox, the combination of iron chelators should be considered on a case-by-case basis, and patients should be monitored for response and adverse events.

Fatalities and life-threatening situations (caused by agranulocytosis) have been reported with the combination of deferiprone and deferoxamine.

Combination therapy is not recommended when monotherapy with either chelator is adequate or when serum ferritin falls below 500 μg/l. Additionally, there are limited data on the combined use of Ferriprox and deferasirox.

The applicant for Deferiprone Lipomed is Lipomed GmbH.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Deferiprone Lipomed to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major.

Deferiprone Lipomed is a generic version of the iron chelating agent Ferriprox, which has been authorized in the European Union since August 1999.

According to the CHMP, studies have shown that Deferiprone Lipomed is of satisfactory quality and bioequivalent to Ferriprox.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Deferiprone Lipomed will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Deferiprone Lipomed will be available as 500-mg film-coated tablets.

The drug will be authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy to treat iron overload in patients with thalassemia major when current chelation therapy is contraindicated or inadequate

- In combination with another chelator in patients with thalassemia major when monotherapy with any iron chelator is ineffective or when prevention or treatment of life-threatening consequences of iron overload justifies rapid or intensive correction.

According to the prescribing information for Ferriprox, the combination of iron chelators should be considered on a case-by-case basis, and patients should be monitored for response and adverse events.

Fatalities and life-threatening situations (caused by agranulocytosis) have been reported with the combination of deferiprone and deferoxamine.

Combination therapy is not recommended when monotherapy with either chelator is adequate or when serum ferritin falls below 500 μg/l. Additionally, there are limited data on the combined use of Ferriprox and deferasirox.

The applicant for Deferiprone Lipomed is Lipomed GmbH.

CHMP backs generic lenalidomide

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Lenalidomide Accord as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Lenalidomide Accord is a generic version of the immunomodulatory agent Revlimid, which has been authorized in the European Union since June 2007.

The CHMP said studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality of Lenalidomide Accord and its bioequivalence to Revlimid.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Lenalidomide Accord will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Lenalidomide Accord will be available as capsules (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 25 mg) and authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy for the maintenance treatment of adults with newly diagnosed MM who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant

- In combination with melphalan and prednisone followed by lenalidomide maintenance in adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant

- In combination with dexamethasone to treat MM in adults who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

The applicant for Lenalidomide Accord is Accord Healthcare Limited.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Lenalidomide Accord as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Lenalidomide Accord is a generic version of the immunomodulatory agent Revlimid, which has been authorized in the European Union since June 2007.

The CHMP said studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality of Lenalidomide Accord and its bioequivalence to Revlimid.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Lenalidomide Accord will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Lenalidomide Accord will be available as capsules (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 25 mg) and authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy for the maintenance treatment of adults with newly diagnosed MM who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant

- In combination with melphalan and prednisone followed by lenalidomide maintenance in adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant

- In combination with dexamethasone to treat MM in adults who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

The applicant for Lenalidomide Accord is Accord Healthcare Limited.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for Lenalidomide Accord as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Lenalidomide Accord is a generic version of the immunomodulatory agent Revlimid, which has been authorized in the European Union since June 2007.

The CHMP said studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality of Lenalidomide Accord and its bioequivalence to Revlimid.

The CHMP’s recommendation for Lenalidomide Accord will be reviewed by the European Commission, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The European Commission usually makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

If approved, Lenalidomide Accord will be available as capsules (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 25 mg) and authorized for the following uses:

- As monotherapy for the maintenance treatment of adults with newly diagnosed MM who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant

- In combination with melphalan and prednisone followed by lenalidomide maintenance in adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant

- In combination with dexamethasone to treat MM in adults who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

The applicant for Lenalidomide Accord is Accord Healthcare Limited.

Catatonia: How to identify and treat it

Is catatonia a rare condition that belongs in the history books, or is it more prevalent than we think? If we think we don’t see it often, how will we recognize it? And how do we treat it? This article reviews the evolution of our understanding of the phenomenology and therapy of this interesting and complex condition.

History of the concept

In 1874, Kahlbaum1,2 was the first to propose a syndrome of motor dysfunction characterized by mutism, immobility, staring gaze, negativism, stereotyped behavior, waxy flexibility, and verbal stereotypies that he called catatonia. Kahlbaum conceptualized catatonia as a distinct disorder,3 but Kraepelin reformulated it as a feature of dementia praecox.4 Although Bleuler felt that catatonia could occur in other psychiatric disorders and in normal people,4 he also included catatonia as a marker of schizophrenia, where it remained from DSM-I through DSM-IV.3 As was believed to be true of schizophrenia, Kraepelin considered catatonia to be characterized by poor prognosis, whereas Bleuler eliminated poor prognosis as a criterion for catatonia.3

In DSM-IV, catatonia was still a subtype of schizophrenia, but for the first time it was expanded diagnostically to become both a specifier in mood disorders, and a syndrome resulting from a general medical condition.5,6 In DSM-5, catatonic schizophrenia was deleted, and catatonia became a specifier for 10 disorders, including schizophrenia, mood disorders, and general medical conditions.3,5-9 In ICD-10, however, catatonia is still associated primarily with schizophrenia.10

A wide range of presentations

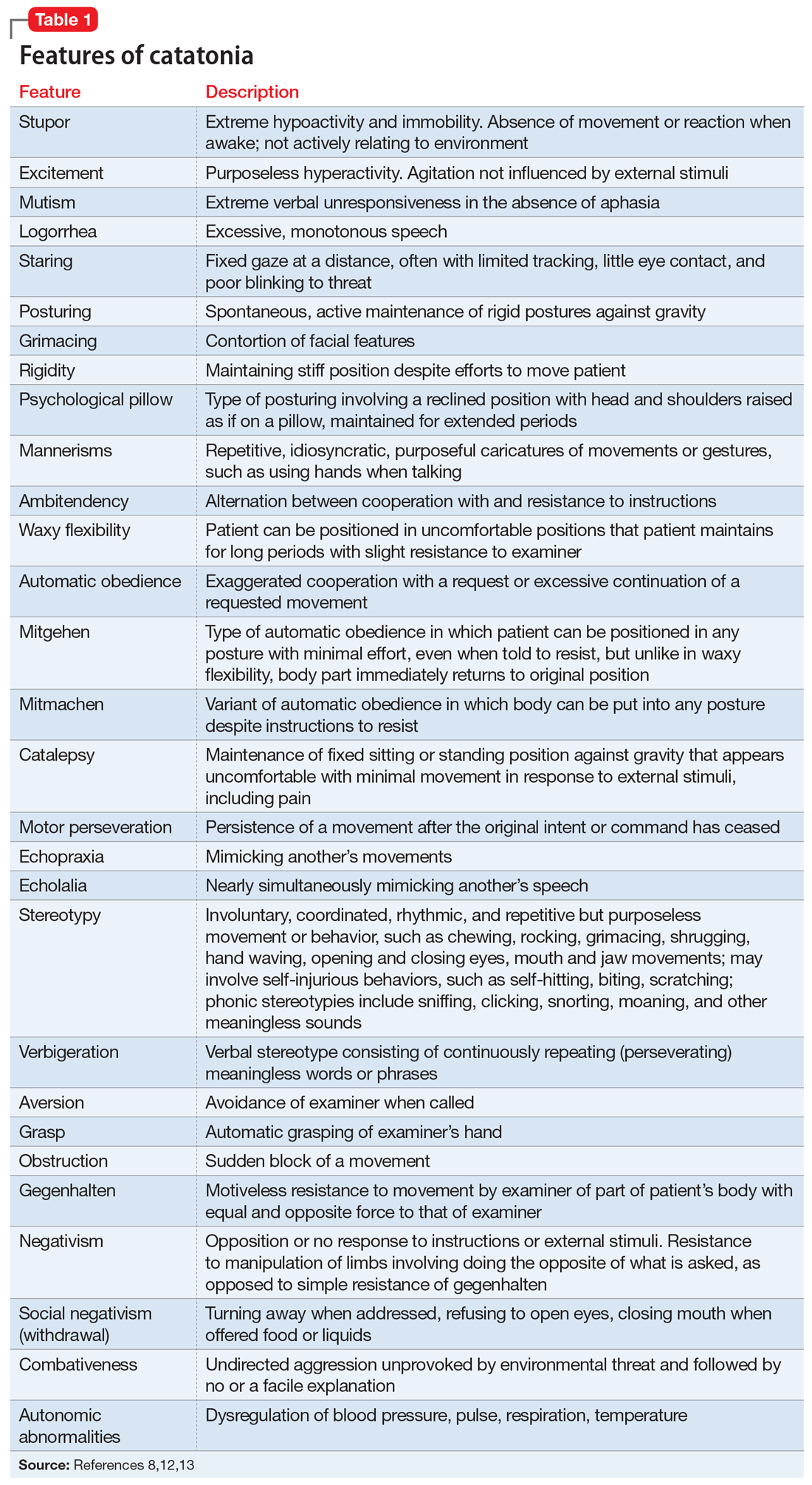

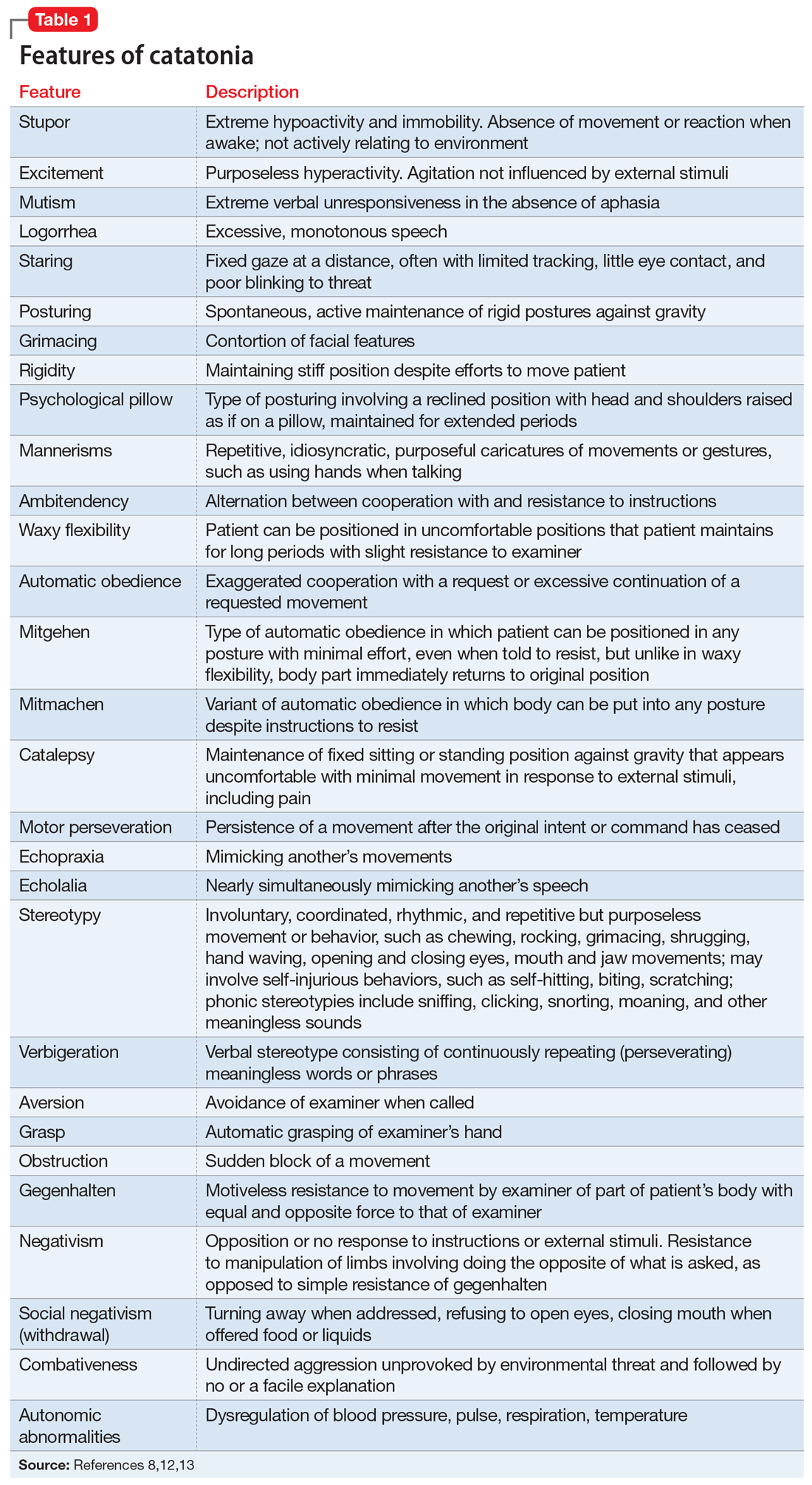

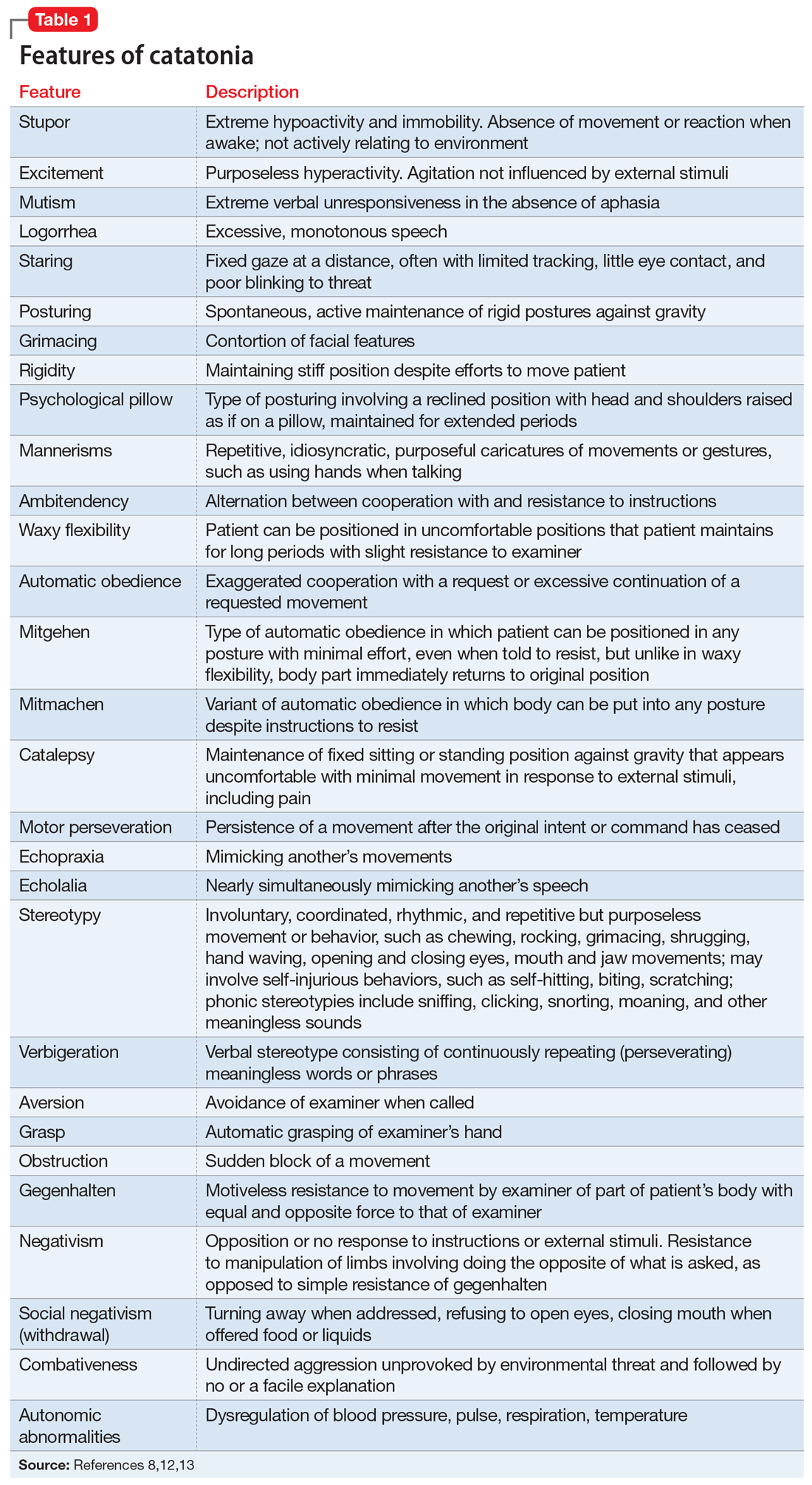

Catatonia is a cyclical syndrome characterized by alterations in motor, behavioral, and vocal signs occurring in the context of medical, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders.8 The most common features are immobility, waxy flexibility, stupor, mutism, negativism, echolalia, echopraxia, peculiarities of voluntary movement, and rigidity.7,11 Features of catatonia that have been repeatedly described through the years are summarized in Table 1.8,12,13 In general, presentations of catatonia are not specific to any psychiatric or medical etiology.13,14

Catatonia often is described along a continuum from retarded/stuporous to excited,14,15 and from benign to malignant.13 Examples of these ranges of presentation include5,12,13,15-19:

Stuporous/retarded catatonia (Kahlbaum syndrome) is a primarily negative syndrome in which stupor, mutism, negativism, obsessional slowness, and posturing predominate. Akinetic mutism and coma vigil are sometimes considered to be types of stuporous catatonia, as occasionally are locked-in syndrome and abulia caused by anterior cingulate lesions.

Excited catatonia (hyperkinetic variant, Bell’s mania, oneirophrenia, oneroid state/syndrome, catatonia raptus) is characterized by agitation, combativeness, verbigeration, stereotypies, grimacing, and echo phenomena (echopraxia and echolalia).

Continue to: Malignant (lethal) catatonia

Malignant (lethal) catatonia consists of catatonia accompanied by excitement, stupor, altered level of consciousness, catalepsy, hyperthermia, and autonomic instability with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, and labile blood pressure. Autonomic dysregulation, fever, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure can be causes of morbidity and mortality. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)—which is associated with dopamine antagonists, especially antipsychotics—is considered a form of malignant catatonia and has a mortality rate of 10% to 20%. Signs of NMS include muscle rigidity, fever, diaphoresis, rigor, altered consciousness, mutism, tachycardia, hypertension, leukocytosis, and laboratory evidence of muscle damage. Serotonin syndrome can be difficult to distinguish from malignant catatonia, but it is usually not associated with waxy flexibility and rigidity.

Several specific subtypes of catatonia that may exist anywhere along dimensions of activity and severity also have been described:

Periodic catatonia. In 1908, Kraepelin described a form of periodic catatonia, with rapid shifts from excitement to stupor.4 Later, Gjessing described periodic catatonia in schizophrenia and reported success treating it with high doses of thyroid hormone.4 Today, periodic catatonia refers to the rapid onset of recurrent, brief hypokinetic or hyperkinetic episodes lasting 4 to 10 days and recurring during the course of weeks to years. Patients often are asymptomatic between episodes except for grimacing, stereotypies, and negativism later in the course.13,15 At least some forms of periodic catatonia are familial,4 with autosomal dominant transmission possibly linked to chromosome 15q15.13

A familial form of catatonia has been described that has a poor response to standard therapies (benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]), but in view of the high comorbidity of catatonia and bipolar disorder, it is difficult to determine whether this is a separate condition, or a group of patients with bipolar disorder.5

Late (ie, late-onset) catatonia is well described in the Japanese literature.10 Reported primarily in women without a known medical illness or brain disorder, late catatonia begins with prodromal hypochondriacal or depressive symptoms during a stressful situation, followed by unprovoked anxiety and agitation. Some patients develop hallucinations, delusions, and recurrent excitement, along with anxiety and agitation. The next stage involves typical catatonic features (mainly excitement, retardation, negativism, and autonomic disturbance), progressing to stupor, mutism, verbal stereotypies, and negativism, including refusal of food. Most patients have residual symptoms following improvement. A few cases have been noted to remit with ECT, with relapse when treatment was discontinued. Late catatonia has been thought to be associated with late-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or to be an independent entity.

Continue to: Untreated catatonia can have...

Untreated catatonia can have serious medical complications, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, aspiration pneumonia, infection, metabolic disorders, decubitus ulcers, malnutrition, dehydration, contractures, thrombosis, urinary retention, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and cardiac arrest.11,12,16,20,21 Mortality approaches 10%.12 In children and adolescents, catatonia increases the risk of premature death (including by suicide) 60-fold.22

Not as rare as you might think

With the shift from inpatient to outpatient care driven by deinstitutionalization, longitudinal close observation became less common, and clinicians got the impression that the dramatic catatonia that was common in the hospital had become rare.3 The impression that catatonia was unimportant was strengthened by expanding industry promotion of antipsychotic medications while ignoring catatonia, for which the industry had no specific treatment.3 With recent research, however, catatonia has been reported in 7% to 38% of adult psychiatric patients, including 9% to 25% of inpatients, 20% to 25% of patients with mania,3,5 and 20% of patients with major depressive episodes.7 Catatonia has been noted in .6% to 18% of adolescent psychiatric inpatients (especially in communication and social disorders programs),5,8,22 some children,5 and 6% to 18% of adult and juvenile patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).23 In the medical setting, catatonia occurs in 12% to 37% of patients with delirium,8,14,17,18,20,24 7% to 45% of medically ill patients, including those with no psychiatric history,12,13 and 4% of ICU patients.12 Several substances have been linked to catatonia; these are discussed later.11 Contrary to earlier impressions, catatonia is more common in mood disorders, particularly mixed bipolar disorder, especially mania,5 than in schizophrenia.7,8,17,25

Pathophysiology/etiology

Conditions associated with catatonia have different features that act through a final common pathway,7 possibly related to the neurobiology of an extreme fear response called tonic immobility that has been conserved through evolution.8 This mechanism may be mediated by decreased dopamine signaling in basal ganglia, orbitofrontal, and limbic systems, including the hypothalamus and basal forebrain.3,17,20 Subcortical reduction of dopaminergic neurotransmission appears to be related to reduced GABAA receptor signaling and dysfunction of N-methyl-

Up to one-quarter of cases of catatonia are secondary to medical (mostly neurologic) factors or substances.15 Table 25,13,15 lists common medical and neurological causes. Medications and substances known to cause catatonia are noted in Table 3.5,8,13,16,26

Catatonia can be a specifier, or a separate condition

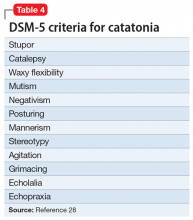

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia are summarized in Table 4.28 With these features, catatonia can be a specifier for depressive, bipolar, or psychotic disorders; a complication of a medical disorder; or another separate diagnosis.8 The diagnosis of catatonia in DSM-5 is made when the clinical picture is dominated by ≥3 of the following core features8,15:

- motoric immobility as evidenced by catalepsy (including waxy flexibility) or stupor

- excessive purposeless motor activity that is not influenced by external stimuli

- extreme negativism or mutism

- peculiarities of voluntary movement such as posturing, stereotyped movements, prominent mannerisms, or prominent grimacing

- echolalia or echopraxia.

Continue to: DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more...

DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more restrictive than DSM-IV criteria. As a result, they exclude a significant number of patients who would be considered catatonic in other systems.29 For example, DSM-5 criteria do not include common features noted in Table 1,8,12,13 such as rigidity and staring.14,29 If the diagnosis is not obvious, it might be suspected in the presence of >1 of posturing, automatic obedience, or waxy flexibility, or >2 of echopraxia/echolalia, gegenhalten, negativism, mitgehen, or stereotypy/vergiberation.12 Clues to catatonia that are not included in formal diagnostic systems and are easily confused with features of psychosis include whispered or robotic speech, uncharacteristic foreign accent, tiptoe walking, hopping, rituals, and odd mannerisms.5

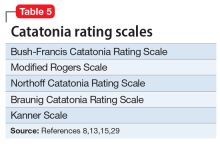

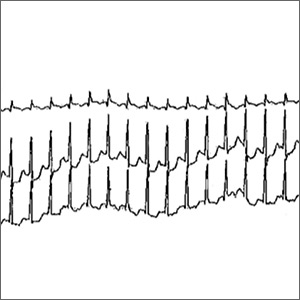

There are several catatonia rating scales containing between 14 and 40 items that are useful in diagnosing and following treatment response in catatonia (Table 58,13,15,29). Of these, the Kanner Scale is primarily applied in neuropsychiatric settings, while the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) has had the most widespread use. The BFCRS consists of 23 items, the first 14 of which are used as a screening instrument. It requires 2 of its first 14 items to diagnose catatonia, while DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 signs.29 If the diagnosis remains in doubt, a benzodiazepine agonist test can be instructive.9,12 The presence of catatonia is suggested by significant improvement, ideally assessed prospectively by improvement of BFCRS scores, shortly after administration of a single dose of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam or 5 mg diazepam IV, or 10 mg zolpidem orally. Further evaluation generally consists of a careful medical and psychiatric histories of patient and family, review of all medications, history of substance use with toxicology as indicated, physical examination focusing on autonomic dysregulation, examination for delirium, and laboratory tests as suggested by the history and examination that may include complete blood count, creatine kinase, serum iron, blood urea nitrogen, electrolytes, creatinine, prolactin, anti-NMDA antibodies, thyroid function tests, serology, metabolic panel, human immunodeficiency virus testing, EEG, and neuroimaging.8,15,16

A complex differential diagnosis

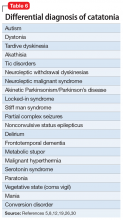

Manifestations of numerous psychiatric and neurologic disorders can mimic or be identical to those of catatonia. The differential diagnosis is complicated by the fact that some of these disorders can cause catatonia, which is then masked by the primary disorder; some disorders (eg, NMS) are forms of catatonia. Table 65,8,12,19,26,30 lists conditions to consider.

Some of these conditions warrant discussion. ASD may have catatonia-like features such as echolalia, echopraxia, excitement, combativeness, grimacing, mutism, logorrhea, verbigeration, catalepsy, mannerisms, rigidity, staring and withdrawal.8 Catatonia may also be a stage of deterioration of autism, in which case it is characterized by increases in slowness of movement and speech, reliance on physical or verbal prompting from others, passivity, and lack of motivation.23 At the same time, catatonic features such as mutism, stereotypic speech, repetitive behavior, echolalia, posturing, mannerisms, purposeless agitation, and rigidity in catatonia can be misinterpreted as signs of ASD.8 Catatonia should be suspected as a complication of longstanding ASD in the presence of a consistent, marked change in motor behavior, such as immobility, decreased speech, stupor, excitement, or mixtures or alternations of stupor and excitement.8 Freezing while doing something, difficulty crossing lines, or uncharacteristic persistence of a particular behavior may also herald the presence of catatonia with ASD.8

Catatonia caused by a neurologic or metabolic factor or a substance can be difficult to distinguish from delirium complicated by catatonia. Delirium may be identified in patients with catatonia by the presence of a waxing and waning level of consciousness (vs fluctuating behavior in catatonia) and slowing of the EEG.12,15 Antipsychotic medications can improve delirium but worsen catatonia, while benzodiazepines can improve catatonia but worsen delirium.

Continue to: Among other neurologic syndromes...

Among other neurologic syndromes that can be confused with catatonia, locked-in syndrome consists of total immobility except for vertical extraocular movements and blinking. In this state, patients attempt to communicate with their eyes, while catatonic patients do not try to communicate. There is no response to a lorazepam challenge test. Stiff man syndrome is associated with painful spasms precipitated by touch, noise, or emotional stimuli. Baclofen can resolve stiff man syndrome, but it can induce catatonia. Paratonia refers to generalized increased motor tone that is idiopathic, or associated with neurodegeneration, encephalopathy, or medications. The only motor sign is increased tone, and other signs of catatonia are absent. Catatonia is usually associated with some motor behaviors and interaction with the environment, even if it is negative, while the coma vigil patient is completely unresponsive. Frontotemporal dementia is progressive, while catatonia usually improves without residual dementia.30

Benzodiazepines, ECT are the usual treatments

Experience dictates that the general principles of treatment noted in Table 712,15,23,31 apply to all patients with catatonia. Since the first reported improvement of catatonia with amobarbital in 1930,6 there have been no controlled studies of specific treatments of catatonia.13 Meaningful treatment trials are either naturalistic, or have been performed only for NMS and malignant catatonia.5 However, multiple case reports and case series suggest that treatments with agents that have anticonvulsant properties (benzodiazepines, barbiturates) and ECT are effective.5

Benzodiazepines and related compounds. Case series have suggested a 60% to 80% remission rate of catatonia with benzodiazepines, the most commonly utilized of which has been lorazepam.7,13,32 Treatment begins with a lorazepam challenge test of 1 to 2 mg in adults and 0.5 to 1 mg in children and geriatric patients,9,15 administered orally (including via nasogastric tube), IM, or IV. Following a response (≥50% improvement), the dose is increased to 2 mg 3 times per day. The dose is further increased to 6 to 16 mg/d, and sometimes up to 30 mg/d.9,11 Oral is less effective than sublingual or IM administration.11 Diazepam can be helpful at doses 5 times the lorazepam dose.9,17 A zo

One alternative benzodiazepine protocol utilizes an initial IV dose of 2 mg lorazepam, repeated 3 to 5 times per day; the dose is increased to 10 to 12 mg/d if the first doses are partially effective.16 A lorazepam/diazepam approach involves a combination of IM lorazepam and IV diazepam.11 The protocol begins with 2 mg of IM lorazepam. If there is no effect within 2 hours, a second 2 mg dose is administered, followed by an IV infusion of 10 mg diazepam in 500 ml of normal saline at 1.25 mg/hour until catatonia remits.

An Indian study of 107 patients (mean age 26) receiving relatively low doses of lorazepam (3 to 6 mg/d for at least 3 days) found that factors suggesting a robust response include a shorter duration of catatonia and waxy flexibility, while passivity, mutism, and auditory hallucinations describing the patient in the third person were associated with a poorer acute response.31 Catatonia with marked retardation and mutism complicating schizophrenia, especially with chronic negative symptoms, may be associated with a lower response rate to benzodiazepines.20,33 Maintenance lorazepam has been effective in reducing relapse and recurrence.11 There are no controlled studies of maintenance treatment with benzodiazepines, but clinical reports suggest that doses in the range of 4 to 10 mg/d are effective.32

Continue to: ECT was used for catatonia in 1934...

ECT was first used for catatonia in 1934, when Laszlo Meduna used chemically induced seizures in catatonic patients who had been on tube feeding for months and no longer needed it after treatment.6,7 As was true for other disorders, this approach was replaced by ECT.7 In various case series, the effectiveness of ECT in catatonia has been 53% to 100%.7,13,15 Right unilateral ECT has been reported to be effective with 1 treatment.21 However, the best-established approach is with bitemporal ECT with a suprathreshold stimulus,9 usually with an acute course of 6 to 20 treatments.20 ECT has been reported to be equally safe and effective in adolescents and adults.34 Continued ECT is usually necessary until the patient has returned to baseline.9

ECT usually is recommended within 24 hours for treatment-resistant malignant catatonia or refusal to eat or drink, and within 2 to 3 days if medications are not sufficiently effective in other forms of catatonia.12,15,20 If ECT is initiated after a benzodiazepine trial, the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil is administered first to reverse the anticonvulsant effect.9 Some experts recommend using a muscle relaxant other than succinylcholine in the presence of evidence of muscle damage.7

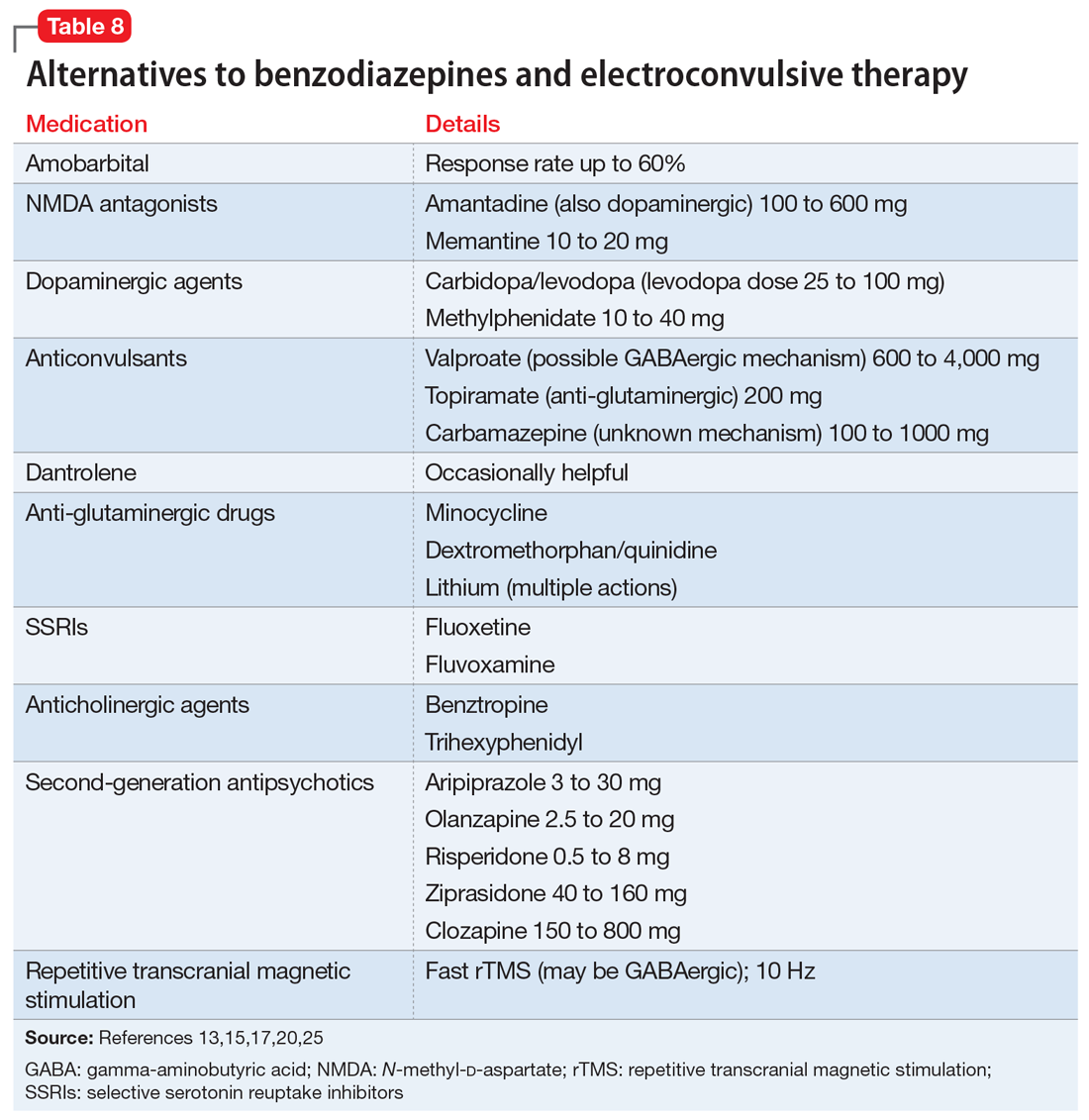

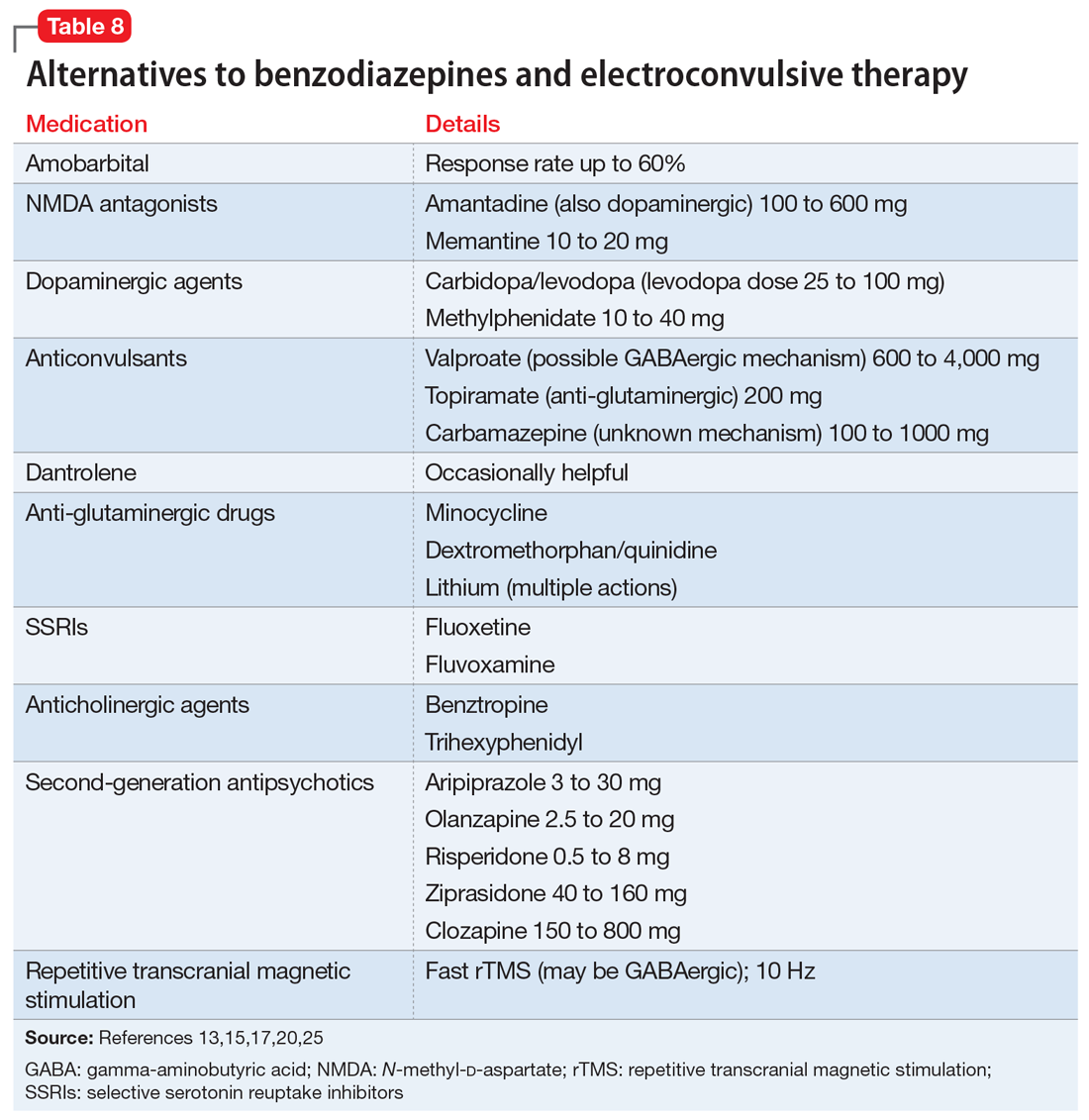

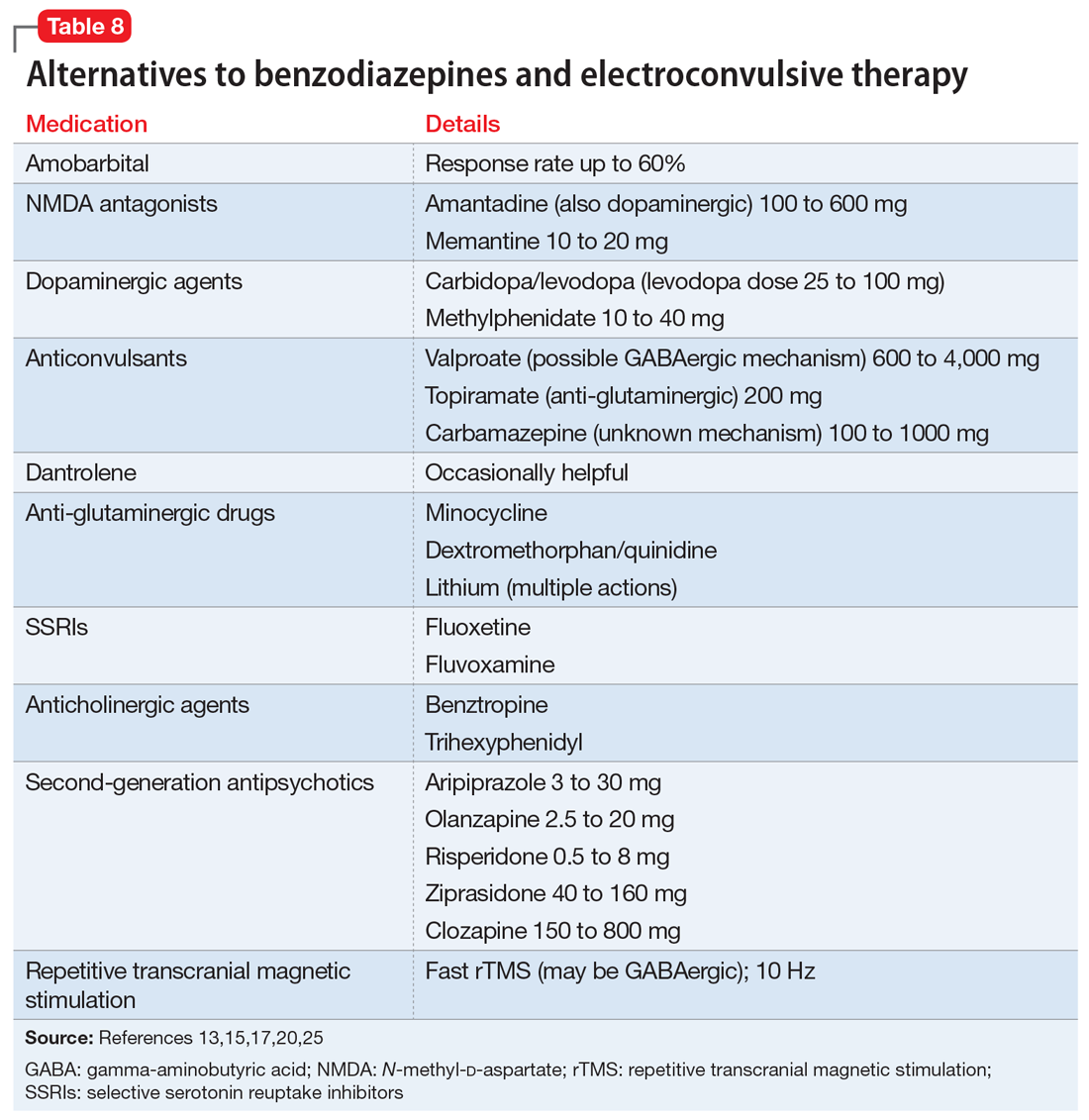

Alternatives to benzodiazepines and ECT. Based on case reports, the treatments described in Table 813,15,17,20,25 have been used for patients with catatonia who do not tolerate or respond to standard treatments. The largest number of case reports have been with NMDA antagonists, while the presumed involvement of reduced dopamine signaling suggests that dopaminergic medications should be helpful. Dantrolene, which blocks release of calcium from intracellular stores and has been used to treat malignant hyperthermia, is sometimes used for NMS, often with disappointing results.

Whereas first-generation antipsychotics definitely increase the risk of catatonia and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) probably do so, SGAs are sometimes necessary to treat persistent psychosis in patients with schizophrenia who develop catatonia. Of these medications, clozapine may be most desirable because of low potency for dopamine receptor blockade and modulation of glutamatergic signaling. Partial dopamine agonism by aripiprazole, and the potential for increased subcortical prefrontal dopamine release resulting from serotonin 5HT2A antagonism and 5HT1A agonism by other SGAs, could also be helpful or at least not harmful in catatonia. Lorazepam is usually administered along with these medications to ameliorate treatment-emergent exacerbation of catatonia.

There are no controlled studies of any of these treatments. Based on case reports, most experts would recommend initiating treatment of catatonia with lorazepam, followed by ECT if necessary or in the presence of life-threatening catatonia. If ECT is not available, ineffective, or not tolerated, the first alternatives to be considered would be an NMDA antagonist or an anticonvulsant.20

Continue to: Course varies by patient, underlying cause

Course varies by patient, underlying cause

The response to benzodiazepines or ECT can vary from episode to episode11 and is similar in adults and younger patients.22 Many patients recover completely after a single episode, while relapse after remission occurs repeatedly in periodic catatonia, which involves chronic alternating stupor and excitement waxing and waning over years.11 Relapses may occur frequently, or every few years.11 Some cases of catatonia initially have an episodic course and become chronic and deteriorating, possibly paralleling the original descriptions of the natural history of untreated catatonia, while malignant catatonia can be complicated by medical morbidity or death.4 The long-term prognosis generally depends on the underlying cause of catatonia.5

Bottom Line

Much more common than many clinicians realize, catatonia can be overlooked because symptoms can mimic or overlap with features of an underlying medical or neurologic disorder. Suspect catatonia when one of these illnesses has an unexpected course or an inadequate treatment response. Be alert to characteristic changes in behavior and speech. A benzodiazepine challenge can be used to diagnose and begin treatment of catatonia. Consider electroconvulsive therapy sooner rather than later, especially for severely ill patients.

Related Resources

- Gibson RC, Walcott G. Benzodiazepines for catatonia in people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006570.

- Newcastle University. Catatonia. https://youtu.be/_s1lzxHRO4U.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Amobarbital • Amytal

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Azithromycin • Zithromax

Baclofen • Lioresal

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dantrolene • Dantrium

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Dextromethorphan/quinidine • Neudexta

Diazepam • Valium

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Flumazenil • Romazicon

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Minocycline • Minocin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Succinylcholine • Anectine

Topiramate • Topamax

Trihexyphenidyl • Artane

Valproate • Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Kahlbaum KL. Catatonia. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1973.

2. Kahlbaum KL. Die Katatonie oder das Spannungsirresein. Berlin: Hirschwald; 1874.

3. Tang VM, Duffin J. Catatonia in the history of psychiatry: construction and deconstruction of a disease concept. Perspect Biol Med. 2014;57(4):524-537.

4. Carroll BT. Kahlbaum’s catatonia revisited. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55(5):431-436.

5. Taylor MA, Fink M. Catatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its own. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1233-1241.

6. Fink M, Fricchione GL, Rummans T, et al. Catatonia is a systemic medical syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(3):250-251.

7. Medda P, Toni C, Luchini F, et al. Catatonia in 26 patients with bipolar disorder: clinical features and response to electroconvulsive therapy. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(8):892-901.

8. Mazzone L, Postorino V, Valeri G, et al. Catatonia in patients with autism: prevalence and management. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(3):205-215.

9. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. Optimizing ECT technique in treating catatonia. J ECT. 2016;32(3):149-150.

10. Kocha H, Moriguchi S, Mimura M. Revisiting the concept of late catatonia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1485-1490.

11. Lin CC, Hung YL, Tsai MC, et al. Relapses and recurrences of catatonia: 30-case analysis and literature review. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:157-165.

12. Saddawi-Konefka D, Berg SM, Nejad SH, et al. Catatonia in the ICU: An important and underdiagnosed cause of altered mental status. A case series and review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2013;42(3):e234-e241.

13. Wijemanne S, Jankovic J. Movement disorders in catatonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(8):825-832.

14. Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Ghormode D, et al. Catatonia in inpatients with psychiatric disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and mood disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(3):919-925.

15. Oldham MA, Lee HB. Catatonia vis-à-vis delirium: the significance of recognizing catatonia in altered mental status. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):554-559.

16. Tuerlings JH, van Waarde JA, Verwey B. A retrospective study of 34 catatonic patients: analysis of clinical ‘care and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(6):631-635.

17. Ohi K, Kuwata A, Shimada T, et al. Response to benzodiazepines and the clinical course in malignant catatonia associated with schizophrenia: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(16):e6566. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006566.

18. Komatsu T, Nomura T, Takami H, et al. Catatonic symptoms appearing before autonomic symptoms help distinguish neuroleptic malignant syndrome from malignant catatonia. Intern Med. 2016;55(19):2893-2897.

19. Lang FU, Lang S, Becker T, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome or catatonia? Trying to solve the catatonic dilemma. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(1):1-5.

20. Beach SR, Gomez-Bernal F, Huffman JC, et al. Alternative treatment strategies for catatonia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:1-19.

21. Kugler JL, Hauptman AJ, Collier SJ, et al. Treatment of catatonia with ultrabrief right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy: a case series. J ECT. 2015;31(3):192-196.

22. Raffin M, Zugaj-Bensaou L, Bodeau N, et al. Treatment use in a prospective naturalistic cohort of children and adolescents with catatonia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(4):441-449.

23. DeJong H, Bunton P, Hare DJ. A systematic review of interventions used to treat catatonic symptoms in people with autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(9):2127-2136.

24. Wachtel L, Commins E, Park MH, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and delirious mania as malignant catatonia in autism: prompt relief with electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(4):319-320.

25. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: subtype or syndrome in DSM? Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1875-1876.

26. Khan M, Pace L, Truong A, et al. Catatonia secondary to synthetic cannabinoid use in two patients with no previous psychosis. Am J Addictions. 2016;25(1):25-27.

27. Komatsu T, Nomura T, Takami H, et al. Catatonic symptoms appearing before autonomic symptoms help distinguish neuroleptic malignant syndrome from malignant catatonia. Intern Med. 2016;55(19):2893-2897.

28. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

29. Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, et al. The diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1-3):256-262.

30. Ducharme S, Dickerson BC, Larvie M, et al. Differentiating frontotemporal dementia from catatonia: a complex neuropsychiatric challenge. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(2):e174-e176.

31. Narayanaswamy JC, Tibrewal P, Zutshi A, et al. Clinical predictors of response to treatment in catatonia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(3):312-316.

32. Thamizh JS, Harshini M, Selvakumar N, et al. Maintenance lorazepam for treatment of recurrent catatonic states: a case series and implications. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;22:147-149

33. Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Chow LY, et al. Lorazepam for chronic catatonia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;142(4):393-398.

34. Flamarique I, Baeza I, de la Serna E, et al. Long-term effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in adolescents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(5):517-524.

Is catatonia a rare condition that belongs in the history books, or is it more prevalent than we think? If we think we don’t see it often, how will we recognize it? And how do we treat it? This article reviews the evolution of our understanding of the phenomenology and therapy of this interesting and complex condition.

History of the concept

In 1874, Kahlbaum1,2 was the first to propose a syndrome of motor dysfunction characterized by mutism, immobility, staring gaze, negativism, stereotyped behavior, waxy flexibility, and verbal stereotypies that he called catatonia. Kahlbaum conceptualized catatonia as a distinct disorder,3 but Kraepelin reformulated it as a feature of dementia praecox.4 Although Bleuler felt that catatonia could occur in other psychiatric disorders and in normal people,4 he also included catatonia as a marker of schizophrenia, where it remained from DSM-I through DSM-IV.3 As was believed to be true of schizophrenia, Kraepelin considered catatonia to be characterized by poor prognosis, whereas Bleuler eliminated poor prognosis as a criterion for catatonia.3

In DSM-IV, catatonia was still a subtype of schizophrenia, but for the first time it was expanded diagnostically to become both a specifier in mood disorders, and a syndrome resulting from a general medical condition.5,6 In DSM-5, catatonic schizophrenia was deleted, and catatonia became a specifier for 10 disorders, including schizophrenia, mood disorders, and general medical conditions.3,5-9 In ICD-10, however, catatonia is still associated primarily with schizophrenia.10

A wide range of presentations

Catatonia is a cyclical syndrome characterized by alterations in motor, behavioral, and vocal signs occurring in the context of medical, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders.8 The most common features are immobility, waxy flexibility, stupor, mutism, negativism, echolalia, echopraxia, peculiarities of voluntary movement, and rigidity.7,11 Features of catatonia that have been repeatedly described through the years are summarized in Table 1.8,12,13 In general, presentations of catatonia are not specific to any psychiatric or medical etiology.13,14

Catatonia often is described along a continuum from retarded/stuporous to excited,14,15 and from benign to malignant.13 Examples of these ranges of presentation include5,12,13,15-19:

Stuporous/retarded catatonia (Kahlbaum syndrome) is a primarily negative syndrome in which stupor, mutism, negativism, obsessional slowness, and posturing predominate. Akinetic mutism and coma vigil are sometimes considered to be types of stuporous catatonia, as occasionally are locked-in syndrome and abulia caused by anterior cingulate lesions.

Excited catatonia (hyperkinetic variant, Bell’s mania, oneirophrenia, oneroid state/syndrome, catatonia raptus) is characterized by agitation, combativeness, verbigeration, stereotypies, grimacing, and echo phenomena (echopraxia and echolalia).

Continue to: Malignant (lethal) catatonia

Malignant (lethal) catatonia consists of catatonia accompanied by excitement, stupor, altered level of consciousness, catalepsy, hyperthermia, and autonomic instability with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, and labile blood pressure. Autonomic dysregulation, fever, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure can be causes of morbidity and mortality. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)—which is associated with dopamine antagonists, especially antipsychotics—is considered a form of malignant catatonia and has a mortality rate of 10% to 20%. Signs of NMS include muscle rigidity, fever, diaphoresis, rigor, altered consciousness, mutism, tachycardia, hypertension, leukocytosis, and laboratory evidence of muscle damage. Serotonin syndrome can be difficult to distinguish from malignant catatonia, but it is usually not associated with waxy flexibility and rigidity.

Several specific subtypes of catatonia that may exist anywhere along dimensions of activity and severity also have been described:

Periodic catatonia. In 1908, Kraepelin described a form of periodic catatonia, with rapid shifts from excitement to stupor.4 Later, Gjessing described periodic catatonia in schizophrenia and reported success treating it with high doses of thyroid hormone.4 Today, periodic catatonia refers to the rapid onset of recurrent, brief hypokinetic or hyperkinetic episodes lasting 4 to 10 days and recurring during the course of weeks to years. Patients often are asymptomatic between episodes except for grimacing, stereotypies, and negativism later in the course.13,15 At least some forms of periodic catatonia are familial,4 with autosomal dominant transmission possibly linked to chromosome 15q15.13

A familial form of catatonia has been described that has a poor response to standard therapies (benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]), but in view of the high comorbidity of catatonia and bipolar disorder, it is difficult to determine whether this is a separate condition, or a group of patients with bipolar disorder.5

Late (ie, late-onset) catatonia is well described in the Japanese literature.10 Reported primarily in women without a known medical illness or brain disorder, late catatonia begins with prodromal hypochondriacal or depressive symptoms during a stressful situation, followed by unprovoked anxiety and agitation. Some patients develop hallucinations, delusions, and recurrent excitement, along with anxiety and agitation. The next stage involves typical catatonic features (mainly excitement, retardation, negativism, and autonomic disturbance), progressing to stupor, mutism, verbal stereotypies, and negativism, including refusal of food. Most patients have residual symptoms following improvement. A few cases have been noted to remit with ECT, with relapse when treatment was discontinued. Late catatonia has been thought to be associated with late-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or to be an independent entity.

Continue to: Untreated catatonia can have...

Untreated catatonia can have serious medical complications, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, aspiration pneumonia, infection, metabolic disorders, decubitus ulcers, malnutrition, dehydration, contractures, thrombosis, urinary retention, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and cardiac arrest.11,12,16,20,21 Mortality approaches 10%.12 In children and adolescents, catatonia increases the risk of premature death (including by suicide) 60-fold.22

Not as rare as you might think

With the shift from inpatient to outpatient care driven by deinstitutionalization, longitudinal close observation became less common, and clinicians got the impression that the dramatic catatonia that was common in the hospital had become rare.3 The impression that catatonia was unimportant was strengthened by expanding industry promotion of antipsychotic medications while ignoring catatonia, for which the industry had no specific treatment.3 With recent research, however, catatonia has been reported in 7% to 38% of adult psychiatric patients, including 9% to 25% of inpatients, 20% to 25% of patients with mania,3,5 and 20% of patients with major depressive episodes.7 Catatonia has been noted in .6% to 18% of adolescent psychiatric inpatients (especially in communication and social disorders programs),5,8,22 some children,5 and 6% to 18% of adult and juvenile patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).23 In the medical setting, catatonia occurs in 12% to 37% of patients with delirium,8,14,17,18,20,24 7% to 45% of medically ill patients, including those with no psychiatric history,12,13 and 4% of ICU patients.12 Several substances have been linked to catatonia; these are discussed later.11 Contrary to earlier impressions, catatonia is more common in mood disorders, particularly mixed bipolar disorder, especially mania,5 than in schizophrenia.7,8,17,25

Pathophysiology/etiology

Conditions associated with catatonia have different features that act through a final common pathway,7 possibly related to the neurobiology of an extreme fear response called tonic immobility that has been conserved through evolution.8 This mechanism may be mediated by decreased dopamine signaling in basal ganglia, orbitofrontal, and limbic systems, including the hypothalamus and basal forebrain.3,17,20 Subcortical reduction of dopaminergic neurotransmission appears to be related to reduced GABAA receptor signaling and dysfunction of N-methyl-

Up to one-quarter of cases of catatonia are secondary to medical (mostly neurologic) factors or substances.15 Table 25,13,15 lists common medical and neurological causes. Medications and substances known to cause catatonia are noted in Table 3.5,8,13,16,26

Catatonia can be a specifier, or a separate condition

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia are summarized in Table 4.28 With these features, catatonia can be a specifier for depressive, bipolar, or psychotic disorders; a complication of a medical disorder; or another separate diagnosis.8 The diagnosis of catatonia in DSM-5 is made when the clinical picture is dominated by ≥3 of the following core features8,15:

- motoric immobility as evidenced by catalepsy (including waxy flexibility) or stupor

- excessive purposeless motor activity that is not influenced by external stimuli

- extreme negativism or mutism

- peculiarities of voluntary movement such as posturing, stereotyped movements, prominent mannerisms, or prominent grimacing

- echolalia or echopraxia.

Continue to: DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more...

DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more restrictive than DSM-IV criteria. As a result, they exclude a significant number of patients who would be considered catatonic in other systems.29 For example, DSM-5 criteria do not include common features noted in Table 1,8,12,13 such as rigidity and staring.14,29 If the diagnosis is not obvious, it might be suspected in the presence of >1 of posturing, automatic obedience, or waxy flexibility, or >2 of echopraxia/echolalia, gegenhalten, negativism, mitgehen, or stereotypy/vergiberation.12 Clues to catatonia that are not included in formal diagnostic systems and are easily confused with features of psychosis include whispered or robotic speech, uncharacteristic foreign accent, tiptoe walking, hopping, rituals, and odd mannerisms.5

There are several catatonia rating scales containing between 14 and 40 items that are useful in diagnosing and following treatment response in catatonia (Table 58,13,15,29). Of these, the Kanner Scale is primarily applied in neuropsychiatric settings, while the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) has had the most widespread use. The BFCRS consists of 23 items, the first 14 of which are used as a screening instrument. It requires 2 of its first 14 items to diagnose catatonia, while DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 signs.29 If the diagnosis remains in doubt, a benzodiazepine agonist test can be instructive.9,12 The presence of catatonia is suggested by significant improvement, ideally assessed prospectively by improvement of BFCRS scores, shortly after administration of a single dose of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam or 5 mg diazepam IV, or 10 mg zolpidem orally. Further evaluation generally consists of a careful medical and psychiatric histories of patient and family, review of all medications, history of substance use with toxicology as indicated, physical examination focusing on autonomic dysregulation, examination for delirium, and laboratory tests as suggested by the history and examination that may include complete blood count, creatine kinase, serum iron, blood urea nitrogen, electrolytes, creatinine, prolactin, anti-NMDA antibodies, thyroid function tests, serology, metabolic panel, human immunodeficiency virus testing, EEG, and neuroimaging.8,15,16

A complex differential diagnosis

Manifestations of numerous psychiatric and neurologic disorders can mimic or be identical to those of catatonia. The differential diagnosis is complicated by the fact that some of these disorders can cause catatonia, which is then masked by the primary disorder; some disorders (eg, NMS) are forms of catatonia. Table 65,8,12,19,26,30 lists conditions to consider.

Some of these conditions warrant discussion. ASD may have catatonia-like features such as echolalia, echopraxia, excitement, combativeness, grimacing, mutism, logorrhea, verbigeration, catalepsy, mannerisms, rigidity, staring and withdrawal.8 Catatonia may also be a stage of deterioration of autism, in which case it is characterized by increases in slowness of movement and speech, reliance on physical or verbal prompting from others, passivity, and lack of motivation.23 At the same time, catatonic features such as mutism, stereotypic speech, repetitive behavior, echolalia, posturing, mannerisms, purposeless agitation, and rigidity in catatonia can be misinterpreted as signs of ASD.8 Catatonia should be suspected as a complication of longstanding ASD in the presence of a consistent, marked change in motor behavior, such as immobility, decreased speech, stupor, excitement, or mixtures or alternations of stupor and excitement.8 Freezing while doing something, difficulty crossing lines, or uncharacteristic persistence of a particular behavior may also herald the presence of catatonia with ASD.8

Catatonia caused by a neurologic or metabolic factor or a substance can be difficult to distinguish from delirium complicated by catatonia. Delirium may be identified in patients with catatonia by the presence of a waxing and waning level of consciousness (vs fluctuating behavior in catatonia) and slowing of the EEG.12,15 Antipsychotic medications can improve delirium but worsen catatonia, while benzodiazepines can improve catatonia but worsen delirium.

Continue to: Among other neurologic syndromes...

Among other neurologic syndromes that can be confused with catatonia, locked-in syndrome consists of total immobility except for vertical extraocular movements and blinking. In this state, patients attempt to communicate with their eyes, while catatonic patients do not try to communicate. There is no response to a lorazepam challenge test. Stiff man syndrome is associated with painful spasms precipitated by touch, noise, or emotional stimuli. Baclofen can resolve stiff man syndrome, but it can induce catatonia. Paratonia refers to generalized increased motor tone that is idiopathic, or associated with neurodegeneration, encephalopathy, or medications. The only motor sign is increased tone, and other signs of catatonia are absent. Catatonia is usually associated with some motor behaviors and interaction with the environment, even if it is negative, while the coma vigil patient is completely unresponsive. Frontotemporal dementia is progressive, while catatonia usually improves without residual dementia.30

Benzodiazepines, ECT are the usual treatments

Experience dictates that the general principles of treatment noted in Table 712,15,23,31 apply to all patients with catatonia. Since the first reported improvement of catatonia with amobarbital in 1930,6 there have been no controlled studies of specific treatments of catatonia.13 Meaningful treatment trials are either naturalistic, or have been performed only for NMS and malignant catatonia.5 However, multiple case reports and case series suggest that treatments with agents that have anticonvulsant properties (benzodiazepines, barbiturates) and ECT are effective.5

Benzodiazepines and related compounds. Case series have suggested a 60% to 80% remission rate of catatonia with benzodiazepines, the most commonly utilized of which has been lorazepam.7,13,32 Treatment begins with a lorazepam challenge test of 1 to 2 mg in adults and 0.5 to 1 mg in children and geriatric patients,9,15 administered orally (including via nasogastric tube), IM, or IV. Following a response (≥50% improvement), the dose is increased to 2 mg 3 times per day. The dose is further increased to 6 to 16 mg/d, and sometimes up to 30 mg/d.9,11 Oral is less effective than sublingual or IM administration.11 Diazepam can be helpful at doses 5 times the lorazepam dose.9,17 A zo

One alternative benzodiazepine protocol utilizes an initial IV dose of 2 mg lorazepam, repeated 3 to 5 times per day; the dose is increased to 10 to 12 mg/d if the first doses are partially effective.16 A lorazepam/diazepam approach involves a combination of IM lorazepam and IV diazepam.11 The protocol begins with 2 mg of IM lorazepam. If there is no effect within 2 hours, a second 2 mg dose is administered, followed by an IV infusion of 10 mg diazepam in 500 ml of normal saline at 1.25 mg/hour until catatonia remits.

An Indian study of 107 patients (mean age 26) receiving relatively low doses of lorazepam (3 to 6 mg/d for at least 3 days) found that factors suggesting a robust response include a shorter duration of catatonia and waxy flexibility, while passivity, mutism, and auditory hallucinations describing the patient in the third person were associated with a poorer acute response.31 Catatonia with marked retardation and mutism complicating schizophrenia, especially with chronic negative symptoms, may be associated with a lower response rate to benzodiazepines.20,33 Maintenance lorazepam has been effective in reducing relapse and recurrence.11 There are no controlled studies of maintenance treatment with benzodiazepines, but clinical reports suggest that doses in the range of 4 to 10 mg/d are effective.32

Continue to: ECT was used for catatonia in 1934...

ECT was first used for catatonia in 1934, when Laszlo Meduna used chemically induced seizures in catatonic patients who had been on tube feeding for months and no longer needed it after treatment.6,7 As was true for other disorders, this approach was replaced by ECT.7 In various case series, the effectiveness of ECT in catatonia has been 53% to 100%.7,13,15 Right unilateral ECT has been reported to be effective with 1 treatment.21 However, the best-established approach is with bitemporal ECT with a suprathreshold stimulus,9 usually with an acute course of 6 to 20 treatments.20 ECT has been reported to be equally safe and effective in adolescents and adults.34 Continued ECT is usually necessary until the patient has returned to baseline.9

ECT usually is recommended within 24 hours for treatment-resistant malignant catatonia or refusal to eat or drink, and within 2 to 3 days if medications are not sufficiently effective in other forms of catatonia.12,15,20 If ECT is initiated after a benzodiazepine trial, the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil is administered first to reverse the anticonvulsant effect.9 Some experts recommend using a muscle relaxant other than succinylcholine in the presence of evidence of muscle damage.7

Alternatives to benzodiazepines and ECT. Based on case reports, the treatments described in Table 813,15,17,20,25 have been used for patients with catatonia who do not tolerate or respond to standard treatments. The largest number of case reports have been with NMDA antagonists, while the presumed involvement of reduced dopamine signaling suggests that dopaminergic medications should be helpful. Dantrolene, which blocks release of calcium from intracellular stores and has been used to treat malignant hyperthermia, is sometimes used for NMS, often with disappointing results.

Whereas first-generation antipsychotics definitely increase the risk of catatonia and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) probably do so, SGAs are sometimes necessary to treat persistent psychosis in patients with schizophrenia who develop catatonia. Of these medications, clozapine may be most desirable because of low potency for dopamine receptor blockade and modulation of glutamatergic signaling. Partial dopamine agonism by aripiprazole, and the potential for increased subcortical prefrontal dopamine release resulting from serotonin 5HT2A antagonism and 5HT1A agonism by other SGAs, could also be helpful or at least not harmful in catatonia. Lorazepam is usually administered along with these medications to ameliorate treatment-emergent exacerbation of catatonia.

There are no controlled studies of any of these treatments. Based on case reports, most experts would recommend initiating treatment of catatonia with lorazepam, followed by ECT if necessary or in the presence of life-threatening catatonia. If ECT is not available, ineffective, or not tolerated, the first alternatives to be considered would be an NMDA antagonist or an anticonvulsant.20

Continue to: Course varies by patient, underlying cause

Course varies by patient, underlying cause

The response to benzodiazepines or ECT can vary from episode to episode11 and is similar in adults and younger patients.22 Many patients recover completely after a single episode, while relapse after remission occurs repeatedly in periodic catatonia, which involves chronic alternating stupor and excitement waxing and waning over years.11 Relapses may occur frequently, or every few years.11 Some cases of catatonia initially have an episodic course and become chronic and deteriorating, possibly paralleling the original descriptions of the natural history of untreated catatonia, while malignant catatonia can be complicated by medical morbidity or death.4 The long-term prognosis generally depends on the underlying cause of catatonia.5

Bottom Line

Much more common than many clinicians realize, catatonia can be overlooked because symptoms can mimic or overlap with features of an underlying medical or neurologic disorder. Suspect catatonia when one of these illnesses has an unexpected course or an inadequate treatment response. Be alert to characteristic changes in behavior and speech. A benzodiazepine challenge can be used to diagnose and begin treatment of catatonia. Consider electroconvulsive therapy sooner rather than later, especially for severely ill patients.

Related Resources

- Gibson RC, Walcott G. Benzodiazepines for catatonia in people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006570.

- Newcastle University. Catatonia. https://youtu.be/_s1lzxHRO4U.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Amobarbital • Amytal

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Azithromycin • Zithromax

Baclofen • Lioresal

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dantrolene • Dantrium

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Dextromethorphan/quinidine • Neudexta

Diazepam • Valium

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Flumazenil • Romazicon

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Minocycline • Minocin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Succinylcholine • Anectine

Topiramate • Topamax

Trihexyphenidyl • Artane

Valproate • Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Is catatonia a rare condition that belongs in the history books, or is it more prevalent than we think? If we think we don’t see it often, how will we recognize it? And how do we treat it? This article reviews the evolution of our understanding of the phenomenology and therapy of this interesting and complex condition.

History of the concept

In 1874, Kahlbaum1,2 was the first to propose a syndrome of motor dysfunction characterized by mutism, immobility, staring gaze, negativism, stereotyped behavior, waxy flexibility, and verbal stereotypies that he called catatonia. Kahlbaum conceptualized catatonia as a distinct disorder,3 but Kraepelin reformulated it as a feature of dementia praecox.4 Although Bleuler felt that catatonia could occur in other psychiatric disorders and in normal people,4 he also included catatonia as a marker of schizophrenia, where it remained from DSM-I through DSM-IV.3 As was believed to be true of schizophrenia, Kraepelin considered catatonia to be characterized by poor prognosis, whereas Bleuler eliminated poor prognosis as a criterion for catatonia.3

In DSM-IV, catatonia was still a subtype of schizophrenia, but for the first time it was expanded diagnostically to become both a specifier in mood disorders, and a syndrome resulting from a general medical condition.5,6 In DSM-5, catatonic schizophrenia was deleted, and catatonia became a specifier for 10 disorders, including schizophrenia, mood disorders, and general medical conditions.3,5-9 In ICD-10, however, catatonia is still associated primarily with schizophrenia.10

A wide range of presentations

Catatonia is a cyclical syndrome characterized by alterations in motor, behavioral, and vocal signs occurring in the context of medical, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders.8 The most common features are immobility, waxy flexibility, stupor, mutism, negativism, echolalia, echopraxia, peculiarities of voluntary movement, and rigidity.7,11 Features of catatonia that have been repeatedly described through the years are summarized in Table 1.8,12,13 In general, presentations of catatonia are not specific to any psychiatric or medical etiology.13,14

Catatonia often is described along a continuum from retarded/stuporous to excited,14,15 and from benign to malignant.13 Examples of these ranges of presentation include5,12,13,15-19:

Stuporous/retarded catatonia (Kahlbaum syndrome) is a primarily negative syndrome in which stupor, mutism, negativism, obsessional slowness, and posturing predominate. Akinetic mutism and coma vigil are sometimes considered to be types of stuporous catatonia, as occasionally are locked-in syndrome and abulia caused by anterior cingulate lesions.

Excited catatonia (hyperkinetic variant, Bell’s mania, oneirophrenia, oneroid state/syndrome, catatonia raptus) is characterized by agitation, combativeness, verbigeration, stereotypies, grimacing, and echo phenomena (echopraxia and echolalia).

Continue to: Malignant (lethal) catatonia

Malignant (lethal) catatonia consists of catatonia accompanied by excitement, stupor, altered level of consciousness, catalepsy, hyperthermia, and autonomic instability with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, and labile blood pressure. Autonomic dysregulation, fever, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure can be causes of morbidity and mortality. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)—which is associated with dopamine antagonists, especially antipsychotics—is considered a form of malignant catatonia and has a mortality rate of 10% to 20%. Signs of NMS include muscle rigidity, fever, diaphoresis, rigor, altered consciousness, mutism, tachycardia, hypertension, leukocytosis, and laboratory evidence of muscle damage. Serotonin syndrome can be difficult to distinguish from malignant catatonia, but it is usually not associated with waxy flexibility and rigidity.

Several specific subtypes of catatonia that may exist anywhere along dimensions of activity and severity also have been described:

Periodic catatonia. In 1908, Kraepelin described a form of periodic catatonia, with rapid shifts from excitement to stupor.4 Later, Gjessing described periodic catatonia in schizophrenia and reported success treating it with high doses of thyroid hormone.4 Today, periodic catatonia refers to the rapid onset of recurrent, brief hypokinetic or hyperkinetic episodes lasting 4 to 10 days and recurring during the course of weeks to years. Patients often are asymptomatic between episodes except for grimacing, stereotypies, and negativism later in the course.13,15 At least some forms of periodic catatonia are familial,4 with autosomal dominant transmission possibly linked to chromosome 15q15.13

A familial form of catatonia has been described that has a poor response to standard therapies (benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]), but in view of the high comorbidity of catatonia and bipolar disorder, it is difficult to determine whether this is a separate condition, or a group of patients with bipolar disorder.5

Late (ie, late-onset) catatonia is well described in the Japanese literature.10 Reported primarily in women without a known medical illness or brain disorder, late catatonia begins with prodromal hypochondriacal or depressive symptoms during a stressful situation, followed by unprovoked anxiety and agitation. Some patients develop hallucinations, delusions, and recurrent excitement, along with anxiety and agitation. The next stage involves typical catatonic features (mainly excitement, retardation, negativism, and autonomic disturbance), progressing to stupor, mutism, verbal stereotypies, and negativism, including refusal of food. Most patients have residual symptoms following improvement. A few cases have been noted to remit with ECT, with relapse when treatment was discontinued. Late catatonia has been thought to be associated with late-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or to be an independent entity.

Continue to: Untreated catatonia can have...

Untreated catatonia can have serious medical complications, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, aspiration pneumonia, infection, metabolic disorders, decubitus ulcers, malnutrition, dehydration, contractures, thrombosis, urinary retention, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and cardiac arrest.11,12,16,20,21 Mortality approaches 10%.12 In children and adolescents, catatonia increases the risk of premature death (including by suicide) 60-fold.22

Not as rare as you might think

With the shift from inpatient to outpatient care driven by deinstitutionalization, longitudinal close observation became less common, and clinicians got the impression that the dramatic catatonia that was common in the hospital had become rare.3 The impression that catatonia was unimportant was strengthened by expanding industry promotion of antipsychotic medications while ignoring catatonia, for which the industry had no specific treatment.3 With recent research, however, catatonia has been reported in 7% to 38% of adult psychiatric patients, including 9% to 25% of inpatients, 20% to 25% of patients with mania,3,5 and 20% of patients with major depressive episodes.7 Catatonia has been noted in .6% to 18% of adolescent psychiatric inpatients (especially in communication and social disorders programs),5,8,22 some children,5 and 6% to 18% of adult and juvenile patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).23 In the medical setting, catatonia occurs in 12% to 37% of patients with delirium,8,14,17,18,20,24 7% to 45% of medically ill patients, including those with no psychiatric history,12,13 and 4% of ICU patients.12 Several substances have been linked to catatonia; these are discussed later.11 Contrary to earlier impressions, catatonia is more common in mood disorders, particularly mixed bipolar disorder, especially mania,5 than in schizophrenia.7,8,17,25

Pathophysiology/etiology

Conditions associated with catatonia have different features that act through a final common pathway,7 possibly related to the neurobiology of an extreme fear response called tonic immobility that has been conserved through evolution.8 This mechanism may be mediated by decreased dopamine signaling in basal ganglia, orbitofrontal, and limbic systems, including the hypothalamus and basal forebrain.3,17,20 Subcortical reduction of dopaminergic neurotransmission appears to be related to reduced GABAA receptor signaling and dysfunction of N-methyl-

Up to one-quarter of cases of catatonia are secondary to medical (mostly neurologic) factors or substances.15 Table 25,13,15 lists common medical and neurological causes. Medications and substances known to cause catatonia are noted in Table 3.5,8,13,16,26

Catatonia can be a specifier, or a separate condition

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia are summarized in Table 4.28 With these features, catatonia can be a specifier for depressive, bipolar, or psychotic disorders; a complication of a medical disorder; or another separate diagnosis.8 The diagnosis of catatonia in DSM-5 is made when the clinical picture is dominated by ≥3 of the following core features8,15:

- motoric immobility as evidenced by catalepsy (including waxy flexibility) or stupor

- excessive purposeless motor activity that is not influenced by external stimuli

- extreme negativism or mutism

- peculiarities of voluntary movement such as posturing, stereotyped movements, prominent mannerisms, or prominent grimacing

- echolalia or echopraxia.

Continue to: DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more...

DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of catatonia are more restrictive than DSM-IV criteria. As a result, they exclude a significant number of patients who would be considered catatonic in other systems.29 For example, DSM-5 criteria do not include common features noted in Table 1,8,12,13 such as rigidity and staring.14,29 If the diagnosis is not obvious, it might be suspected in the presence of >1 of posturing, automatic obedience, or waxy flexibility, or >2 of echopraxia/echolalia, gegenhalten, negativism, mitgehen, or stereotypy/vergiberation.12 Clues to catatonia that are not included in formal diagnostic systems and are easily confused with features of psychosis include whispered or robotic speech, uncharacteristic foreign accent, tiptoe walking, hopping, rituals, and odd mannerisms.5

There are several catatonia rating scales containing between 14 and 40 items that are useful in diagnosing and following treatment response in catatonia (Table 58,13,15,29). Of these, the Kanner Scale is primarily applied in neuropsychiatric settings, while the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) has had the most widespread use. The BFCRS consists of 23 items, the first 14 of which are used as a screening instrument. It requires 2 of its first 14 items to diagnose catatonia, while DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 signs.29 If the diagnosis remains in doubt, a benzodiazepine agonist test can be instructive.9,12 The presence of catatonia is suggested by significant improvement, ideally assessed prospectively by improvement of BFCRS scores, shortly after administration of a single dose of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam or 5 mg diazepam IV, or 10 mg zolpidem orally. Further evaluation generally consists of a careful medical and psychiatric histories of patient and family, review of all medications, history of substance use with toxicology as indicated, physical examination focusing on autonomic dysregulation, examination for delirium, and laboratory tests as suggested by the history and examination that may include complete blood count, creatine kinase, serum iron, blood urea nitrogen, electrolytes, creatinine, prolactin, anti-NMDA antibodies, thyroid function tests, serology, metabolic panel, human immunodeficiency virus testing, EEG, and neuroimaging.8,15,16

A complex differential diagnosis

Manifestations of numerous psychiatric and neurologic disorders can mimic or be identical to those of catatonia. The differential diagnosis is complicated by the fact that some of these disorders can cause catatonia, which is then masked by the primary disorder; some disorders (eg, NMS) are forms of catatonia. Table 65,8,12,19,26,30 lists conditions to consider.

Some of these conditions warrant discussion. ASD may have catatonia-like features such as echolalia, echopraxia, excitement, combativeness, grimacing, mutism, logorrhea, verbigeration, catalepsy, mannerisms, rigidity, staring and withdrawal.8 Catatonia may also be a stage of deterioration of autism, in which case it is characterized by increases in slowness of movement and speech, reliance on physical or verbal prompting from others, passivity, and lack of motivation.23 At the same time, catatonic features such as mutism, stereotypic speech, repetitive behavior, echolalia, posturing, mannerisms, purposeless agitation, and rigidity in catatonia can be misinterpreted as signs of ASD.8 Catatonia should be suspected as a complication of longstanding ASD in the presence of a consistent, marked change in motor behavior, such as immobility, decreased speech, stupor, excitement, or mixtures or alternations of stupor and excitement.8 Freezing while doing something, difficulty crossing lines, or uncharacteristic persistence of a particular behavior may also herald the presence of catatonia with ASD.8

Catatonia caused by a neurologic or metabolic factor or a substance can be difficult to distinguish from delirium complicated by catatonia. Delirium may be identified in patients with catatonia by the presence of a waxing and waning level of consciousness (vs fluctuating behavior in catatonia) and slowing of the EEG.12,15 Antipsychotic medications can improve delirium but worsen catatonia, while benzodiazepines can improve catatonia but worsen delirium.

Continue to: Among other neurologic syndromes...

Among other neurologic syndromes that can be confused with catatonia, locked-in syndrome consists of total immobility except for vertical extraocular movements and blinking. In this state, patients attempt to communicate with their eyes, while catatonic patients do not try to communicate. There is no response to a lorazepam challenge test. Stiff man syndrome is associated with painful spasms precipitated by touch, noise, or emotional stimuli. Baclofen can resolve stiff man syndrome, but it can induce catatonia. Paratonia refers to generalized increased motor tone that is idiopathic, or associated with neurodegeneration, encephalopathy, or medications. The only motor sign is increased tone, and other signs of catatonia are absent. Catatonia is usually associated with some motor behaviors and interaction with the environment, even if it is negative, while the coma vigil patient is completely unresponsive. Frontotemporal dementia is progressive, while catatonia usually improves without residual dementia.30

Benzodiazepines, ECT are the usual treatments

Experience dictates that the general principles of treatment noted in Table 712,15,23,31 apply to all patients with catatonia. Since the first reported improvement of catatonia with amobarbital in 1930,6 there have been no controlled studies of specific treatments of catatonia.13 Meaningful treatment trials are either naturalistic, or have been performed only for NMS and malignant catatonia.5 However, multiple case reports and case series suggest that treatments with agents that have anticonvulsant properties (benzodiazepines, barbiturates) and ECT are effective.5

Benzodiazepines and related compounds. Case series have suggested a 60% to 80% remission rate of catatonia with benzodiazepines, the most commonly utilized of which has been lorazepam.7,13,32 Treatment begins with a lorazepam challenge test of 1 to 2 mg in adults and 0.5 to 1 mg in children and geriatric patients,9,15 administered orally (including via nasogastric tube), IM, or IV. Following a response (≥50% improvement), the dose is increased to 2 mg 3 times per day. The dose is further increased to 6 to 16 mg/d, and sometimes up to 30 mg/d.9,11 Oral is less effective than sublingual or IM administration.11 Diazepam can be helpful at doses 5 times the lorazepam dose.9,17 A zo

One alternative benzodiazepine protocol utilizes an initial IV dose of 2 mg lorazepam, repeated 3 to 5 times per day; the dose is increased to 10 to 12 mg/d if the first doses are partially effective.16 A lorazepam/diazepam approach involves a combination of IM lorazepam and IV diazepam.11 The protocol begins with 2 mg of IM lorazepam. If there is no effect within 2 hours, a second 2 mg dose is administered, followed by an IV infusion of 10 mg diazepam in 500 ml of normal saline at 1.25 mg/hour until catatonia remits.