User login

Cost-effective wound healing described with fetal bovine collagen matrix

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

CMS targets Part B drug policy in 2019 regulatory updates

Doctors could see changes in how they are paid by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for the drugs they administer in their office, depending on the outcome of two recent regulatory actions proposed by the agency.

The more immediate action could see an alteration to payment rates for newly launched drugs. The more long-term action could be the relaunch of the Competitive Acquisition Program, although there is much more uncertainty surrounding that change.

CMS is seeking to lower the Part B add-on payment for drugs that are new to market and do not yet have an average sales price (ASP) established. The proposal calls for these drugs to be reimbursed at the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) plus 3%, rather than the current rate of WAC plus 6%. The change is part of the proposed physician fee schedule for 2019.

The add-on payment has no statutory definition as to what it is intended to cover, but CMS noted in the proposed rule that it “is widely believed to include services associated with drug acquisition that are not separately paid for, such as handling and storage, as well as additional mark-ups in drug distribution channels.”

Agency officials said that the add-on payment has raised concerns in recent years “because more revenue can be generated from percentage-based add-on payments for expensive drugs, and an opportunity to generate more revenue may create an incentive for the use of more expensive drugs.”

CMS also noted that once an ASP has been established – generally after a drug has been available for several months – the price for that drug is generally lower than the WAC price and, citing a 2014 HHS Office of Inspector General report, noted that “WACs often do not reflect the actual market price for drugs.”

The move to lower payments to WAC plus 3% for new drugs is consistent with a recent recommendation from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).

CMS added that the reduction would reduce beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, since copayments are a percentage of the total cost of the drug, including the add-on payment amount.

“The proposed approach would help Medicare beneficiaries afford to pay for new drugs by reducing out-of-pocket expenses and would help counteract the effects of increasing launch prices for newly approved drugs and biologicals,” CMS said in the proposed regulation.

But the American College of Rheumatology raised concerns about the proposal. Specifically, ACR is concerned that plans to cut add-on payments for new drugs “could slow market uptake of biosimilars and thwart the Administration’s efforts to reduce drug prices,” the group said in a statement.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) also took issue with the proposal. “This is a payment cut from the current rate of Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) plus 6%, or what is really plus 4.3% when factoring in the sequester,” the COA said in a statement. “COA believes that this payment cut for new cancer therapies will result in drug manufacturers actually increasing WAC list prices so that their new products will not be at a competitive disadvantage to existing products, which are reimbursed at average sales price (ASP) plus 6%.”

The second proposal, which could take longer to materialize, revolves around the potential relaunch of the failed competitive acquisition program (CAP) for Part B drugs. CMS is currently requesting information, with questions on what a revamped program could look like if the agency were to move forward with it. The request for information is part of the proposed rule updating the Outpatient Prospective Payment System for 2019.

Under the original CAP, physicians who participated in the program would order drugs from an approved vendor, who would then bill Medicare and collect cost-sharing payments from the beneficiary. The original program was in operation for 18 months, ending on Dec. 31, 2008, after it had little participation and faced other concerns.

More recently, MedPAC recommended a revised version of the program, which they dubbed the Part B Drug Value Program (DVP). Under this construct, private vendors would acquire drugs at lower prices using various negotiation tools, and physicians would be encouraged to make more value-based use decisions based on opportunities for shared savings though their Medicare billing for the use of Part B drugs.

CMS is asking for feedback on a wide range of questions on how the revamped CAP program should be designed, including program design, which suppliers and drugs to include, how to incentivize participation, how to structure outcomes-based arrangements, and whether indication-based pricing should be used.

Doctors could see changes in how they are paid by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for the drugs they administer in their office, depending on the outcome of two recent regulatory actions proposed by the agency.

The more immediate action could see an alteration to payment rates for newly launched drugs. The more long-term action could be the relaunch of the Competitive Acquisition Program, although there is much more uncertainty surrounding that change.

CMS is seeking to lower the Part B add-on payment for drugs that are new to market and do not yet have an average sales price (ASP) established. The proposal calls for these drugs to be reimbursed at the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) plus 3%, rather than the current rate of WAC plus 6%. The change is part of the proposed physician fee schedule for 2019.

The add-on payment has no statutory definition as to what it is intended to cover, but CMS noted in the proposed rule that it “is widely believed to include services associated with drug acquisition that are not separately paid for, such as handling and storage, as well as additional mark-ups in drug distribution channels.”

Agency officials said that the add-on payment has raised concerns in recent years “because more revenue can be generated from percentage-based add-on payments for expensive drugs, and an opportunity to generate more revenue may create an incentive for the use of more expensive drugs.”

CMS also noted that once an ASP has been established – generally after a drug has been available for several months – the price for that drug is generally lower than the WAC price and, citing a 2014 HHS Office of Inspector General report, noted that “WACs often do not reflect the actual market price for drugs.”

The move to lower payments to WAC plus 3% for new drugs is consistent with a recent recommendation from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).

CMS added that the reduction would reduce beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, since copayments are a percentage of the total cost of the drug, including the add-on payment amount.

“The proposed approach would help Medicare beneficiaries afford to pay for new drugs by reducing out-of-pocket expenses and would help counteract the effects of increasing launch prices for newly approved drugs and biologicals,” CMS said in the proposed regulation.

But the American College of Rheumatology raised concerns about the proposal. Specifically, ACR is concerned that plans to cut add-on payments for new drugs “could slow market uptake of biosimilars and thwart the Administration’s efforts to reduce drug prices,” the group said in a statement.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) also took issue with the proposal. “This is a payment cut from the current rate of Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) plus 6%, or what is really plus 4.3% when factoring in the sequester,” the COA said in a statement. “COA believes that this payment cut for new cancer therapies will result in drug manufacturers actually increasing WAC list prices so that their new products will not be at a competitive disadvantage to existing products, which are reimbursed at average sales price (ASP) plus 6%.”

The second proposal, which could take longer to materialize, revolves around the potential relaunch of the failed competitive acquisition program (CAP) for Part B drugs. CMS is currently requesting information, with questions on what a revamped program could look like if the agency were to move forward with it. The request for information is part of the proposed rule updating the Outpatient Prospective Payment System for 2019.

Under the original CAP, physicians who participated in the program would order drugs from an approved vendor, who would then bill Medicare and collect cost-sharing payments from the beneficiary. The original program was in operation for 18 months, ending on Dec. 31, 2008, after it had little participation and faced other concerns.

More recently, MedPAC recommended a revised version of the program, which they dubbed the Part B Drug Value Program (DVP). Under this construct, private vendors would acquire drugs at lower prices using various negotiation tools, and physicians would be encouraged to make more value-based use decisions based on opportunities for shared savings though their Medicare billing for the use of Part B drugs.

CMS is asking for feedback on a wide range of questions on how the revamped CAP program should be designed, including program design, which suppliers and drugs to include, how to incentivize participation, how to structure outcomes-based arrangements, and whether indication-based pricing should be used.

Doctors could see changes in how they are paid by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for the drugs they administer in their office, depending on the outcome of two recent regulatory actions proposed by the agency.

The more immediate action could see an alteration to payment rates for newly launched drugs. The more long-term action could be the relaunch of the Competitive Acquisition Program, although there is much more uncertainty surrounding that change.

CMS is seeking to lower the Part B add-on payment for drugs that are new to market and do not yet have an average sales price (ASP) established. The proposal calls for these drugs to be reimbursed at the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) plus 3%, rather than the current rate of WAC plus 6%. The change is part of the proposed physician fee schedule for 2019.

The add-on payment has no statutory definition as to what it is intended to cover, but CMS noted in the proposed rule that it “is widely believed to include services associated with drug acquisition that are not separately paid for, such as handling and storage, as well as additional mark-ups in drug distribution channels.”

Agency officials said that the add-on payment has raised concerns in recent years “because more revenue can be generated from percentage-based add-on payments for expensive drugs, and an opportunity to generate more revenue may create an incentive for the use of more expensive drugs.”

CMS also noted that once an ASP has been established – generally after a drug has been available for several months – the price for that drug is generally lower than the WAC price and, citing a 2014 HHS Office of Inspector General report, noted that “WACs often do not reflect the actual market price for drugs.”

The move to lower payments to WAC plus 3% for new drugs is consistent with a recent recommendation from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).

CMS added that the reduction would reduce beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, since copayments are a percentage of the total cost of the drug, including the add-on payment amount.

“The proposed approach would help Medicare beneficiaries afford to pay for new drugs by reducing out-of-pocket expenses and would help counteract the effects of increasing launch prices for newly approved drugs and biologicals,” CMS said in the proposed regulation.

But the American College of Rheumatology raised concerns about the proposal. Specifically, ACR is concerned that plans to cut add-on payments for new drugs “could slow market uptake of biosimilars and thwart the Administration’s efforts to reduce drug prices,” the group said in a statement.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) also took issue with the proposal. “This is a payment cut from the current rate of Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) plus 6%, or what is really plus 4.3% when factoring in the sequester,” the COA said in a statement. “COA believes that this payment cut for new cancer therapies will result in drug manufacturers actually increasing WAC list prices so that their new products will not be at a competitive disadvantage to existing products, which are reimbursed at average sales price (ASP) plus 6%.”

The second proposal, which could take longer to materialize, revolves around the potential relaunch of the failed competitive acquisition program (CAP) for Part B drugs. CMS is currently requesting information, with questions on what a revamped program could look like if the agency were to move forward with it. The request for information is part of the proposed rule updating the Outpatient Prospective Payment System for 2019.

Under the original CAP, physicians who participated in the program would order drugs from an approved vendor, who would then bill Medicare and collect cost-sharing payments from the beneficiary. The original program was in operation for 18 months, ending on Dec. 31, 2008, after it had little participation and faced other concerns.

More recently, MedPAC recommended a revised version of the program, which they dubbed the Part B Drug Value Program (DVP). Under this construct, private vendors would acquire drugs at lower prices using various negotiation tools, and physicians would be encouraged to make more value-based use decisions based on opportunities for shared savings though their Medicare billing for the use of Part B drugs.

CMS is asking for feedback on a wide range of questions on how the revamped CAP program should be designed, including program design, which suppliers and drugs to include, how to incentivize participation, how to structure outcomes-based arrangements, and whether indication-based pricing should be used.

Five common pitfalls of retailing skin care

Others believe that providing patients with the correct skin care product recommendations for their skin’s needs is a crucial step to improving outcomes and educating patients.

There is a wide range of challenges related to skin care retail that many physicians face. I will be running a course on Skin Care Retail at the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery meeting in October in Scottsdale, Ariz., if you want to learn more or share your opinions. I have surveyed plastic surgeons and dermatologists via LinkedIn about what they believe are some of the biggest pitfalls to retailing skin care. Here, I will share some of their insights and suggestions for overcoming these obstacles.

1. Patients are more knowledgeable about skin care than ever before

Facing an increasing number of over-the-counter skin care products available, as well as buzzwords like “organic ingredients” and “vegan,” patients are now bombarded with information from a variety of different sources. Because of this, patients come to the doctor with preconceived ideas that can affect compliance if their specific needs and beliefs are not properly addressed.

For New York plastic surgeon Sonita M. Sadio, MD, this is one of the reasons why she chooses not to sell skin care in her office.

“My practice is highly consultative, and ongoing skin care recommendations are a significant part of what I do to optimize patient outcomes,” Dr. Sadio said. “Patients are well-educated about skin care today. They know their ingredients and insist on clean formulations, free of certain ingredients, such as ‘cruelty-free’ and ‘vegan.’ Others feel deprived if they are not using an expensive product in elegant packaging. Still, others insist on drugstore favorites or ‘eco’ offerings and have their own sense of what that means. My job is to optimize the clinical outcome while also meeting these patients needs to ensure compliance.”

Not all doctors have the time, knowledge or desire to personally design each patient’s skin care regimen. Many delegate this to the staff. However, it is impossible to ensure that your staff matches patients to the proper products unless they have had extensive training on both skin care products and how to match them to the patient’s skin issues.

2. Patients are wary when the doctors sells only one product brand

Many studies have shown that, although consumers desire a choice when making purchases, they get overwhelmed if they are presented with too many options. One study showed that it is optimal to carry at least 3 brands of products. For this reason, limiting the skin care you sell to one brand or doing your own private label is not optimal.

New York dermatologist Rebecca Tamez, MD, pointed out the same problem when selling practice-specific skin care. “At my previous job, we sold skin care products directly to patients. I had no issues selling products that were readily available in drugstores or online (such as Vanicream and EltaMD). We usually sold these around the same cost as the drugstore or Amazon. However, it was harder to sell the practice-specific skin care line. I feel patients were more wary of these products.”

3. Doctors do not want to feel like salespeople

If you have read my Dermatology News columns in the past, you may know that I think it is unethical for dermatologists to not offer specific skin care advice to their patients. If patients do not get ethical and scientific recommendations from us, they will follow the advice of a friend or salesperson or purchase based on often inflated marketing claims.

Dermatologists often tell me: “I am not a cosmetic dermatologist so I do not sell skin care.” I feel strongly that general dermatologists should be giving specific written skin care recommendations for their patients too. Acne, rosacea, melasma, eczema, psoriasis, keratosis pilaris, and many other conditions will improve faster with an efficacious skin care regimen, assuming the patient is compliant with the instructions. Retailing skin care improves compliance by eliminating a few barriers to beginning the skin care regimen. I believe that the mindset of dermatologists needs to change: It is not about selling products to patients, it is about educating them on what to use and offering the products out of convenience and the desire to improve compliance.

Meadowbrook, Pa., dermatologist Michael A. Tomeo, MD, explained an obstacle faced by many dermatologists:

“I suspect, like many of my colleagues,” said Dr. Tomeo, “that I am held back in terms of salesmanship, having been trained in the traditional way. Physicians of my generation were taught to be ethical and professional and to focus on academic and clinical excellence, and salesmanship and advertising one’s services were frowned upon. It takes time to reset one’s former proclivities. Cosmeceuticals and nutraceuticals are revolutionizing the skin care world, and as experts in all things skin, we need to be well informed and offer our patients safe, effective, and cutting-edge treatments.”

4. Providers are concerned about product costs and time constraints

Providing excellent patient care and improving outcomes is at the forefront of our business, but financial concerns and time constraints prevent some doctors from offering skin care to their patients.

Rochester Hills, Mich., plastic surgeon Richard Hainer, MD, has found that “skin care is often too complex with too many products and is not very profitable.” For those reasons, Dr. Hainer has chosen not to retail skin care in his practice.

Nampa, Idaho, dermatologist Ryan S. Owsley, MD, explained that “the required minimum purchases by some of the product lines can leave the practice with expired product if it is not selling a particular line well. Cost can also be an issue for some patients in the area we are located.”

As a burn survivor and burn surgeon, Mark McDonough, MD, from Orlando “has a long history with skin care and rejuvenation. I did have a private label skin care line, including a moisturizer, a hydroquinone product, a retinol cream, and a sunscreen,” Dr. McDonough said. “However, and regrettably, I have not kept up with marketing and promotion, with most of my energy invested in trauma and disease survivors through a book, a blog, and my platform through my website.”

Doing your own product line is costly and spending the time and resources to promote it is not always possible. Buying the minimum order of products is often expensive, and you will not be able to sell them without a proven methodology in place. New products enter the market frequently, and it is expensive to always carry the latest technologies because new minimum orders must be met with each new brand that you add.

5. Selling skin care requires ongoing education

Properly recommending and retailing skin care involves physician, staff, and patient education. Unfortunately, most practices rely on training from the cosmeceutical sales reps who obviously have a brand bias. There is minimal unbiased “brand agnostic” skin care training for dermatologists and their staff. In fact, the AAD meeting has only a few skin care lectures in the program. Plastic surgeon Gaurav Bharti, MD, of Charlotte, N.C., explained that “motivating staff to help with retail skin care can be challenging. The first step is to get the staff familiar with the products with open discussions with the representatives. The next step has been to have the staff actually use the products and believe in them. Once they believe in the product, we have used an incentivization model that’s simple, transparent, and predictable.”

We are all too busy to spend adequate time with our patients, so it is critical that our staff be able to properly recommended skin care for us. We have to ensure that our staff is taking an ethical and scientific approach to skin care retail rather than a financial one. Rigorous staff training on how to match skin care products to skin type is the key to improving outcomes with skin care recommendations.

In a similar sense, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Richard Williams, MD, commented that “aestheticians often succumb to the desires of our patients to carry too many products in inventory, for which they do not have enough knowledge of the product’s benefits. This can be a very frustrating challenge.”

Conclusion

Although there are many obstacles to retailing skin care in your medical practice, the benefits that it provides to both your patients (improved outcomes) and your practice (increased profitability) far outweigh the challenges. I solved these pitfalls in my own practice by developing a standardized staff training program and skin care diagnostic software that is now used by over 100 medical practices. If you want to start retaining skin care, my advice is develop a training plan and a methodology for the recommendation and patient education process before you spend a lot of money on the required minimum product order. Feel free to contact me for advice. Alternatively, if you already do a great job of retailing skin care and want to provide tips to include in my American Society for Dermatologic Surgery course, contact me on LinkedIn or [email protected]. You can also find blogs I have written on skin care retail advice at STSFranchise.com.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014); she also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems.

Others believe that providing patients with the correct skin care product recommendations for their skin’s needs is a crucial step to improving outcomes and educating patients.

There is a wide range of challenges related to skin care retail that many physicians face. I will be running a course on Skin Care Retail at the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery meeting in October in Scottsdale, Ariz., if you want to learn more or share your opinions. I have surveyed plastic surgeons and dermatologists via LinkedIn about what they believe are some of the biggest pitfalls to retailing skin care. Here, I will share some of their insights and suggestions for overcoming these obstacles.

1. Patients are more knowledgeable about skin care than ever before

Facing an increasing number of over-the-counter skin care products available, as well as buzzwords like “organic ingredients” and “vegan,” patients are now bombarded with information from a variety of different sources. Because of this, patients come to the doctor with preconceived ideas that can affect compliance if their specific needs and beliefs are not properly addressed.

For New York plastic surgeon Sonita M. Sadio, MD, this is one of the reasons why she chooses not to sell skin care in her office.

“My practice is highly consultative, and ongoing skin care recommendations are a significant part of what I do to optimize patient outcomes,” Dr. Sadio said. “Patients are well-educated about skin care today. They know their ingredients and insist on clean formulations, free of certain ingredients, such as ‘cruelty-free’ and ‘vegan.’ Others feel deprived if they are not using an expensive product in elegant packaging. Still, others insist on drugstore favorites or ‘eco’ offerings and have their own sense of what that means. My job is to optimize the clinical outcome while also meeting these patients needs to ensure compliance.”

Not all doctors have the time, knowledge or desire to personally design each patient’s skin care regimen. Many delegate this to the staff. However, it is impossible to ensure that your staff matches patients to the proper products unless they have had extensive training on both skin care products and how to match them to the patient’s skin issues.

2. Patients are wary when the doctors sells only one product brand

Many studies have shown that, although consumers desire a choice when making purchases, they get overwhelmed if they are presented with too many options. One study showed that it is optimal to carry at least 3 brands of products. For this reason, limiting the skin care you sell to one brand or doing your own private label is not optimal.

New York dermatologist Rebecca Tamez, MD, pointed out the same problem when selling practice-specific skin care. “At my previous job, we sold skin care products directly to patients. I had no issues selling products that were readily available in drugstores or online (such as Vanicream and EltaMD). We usually sold these around the same cost as the drugstore or Amazon. However, it was harder to sell the practice-specific skin care line. I feel patients were more wary of these products.”

3. Doctors do not want to feel like salespeople

If you have read my Dermatology News columns in the past, you may know that I think it is unethical for dermatologists to not offer specific skin care advice to their patients. If patients do not get ethical and scientific recommendations from us, they will follow the advice of a friend or salesperson or purchase based on often inflated marketing claims.

Dermatologists often tell me: “I am not a cosmetic dermatologist so I do not sell skin care.” I feel strongly that general dermatologists should be giving specific written skin care recommendations for their patients too. Acne, rosacea, melasma, eczema, psoriasis, keratosis pilaris, and many other conditions will improve faster with an efficacious skin care regimen, assuming the patient is compliant with the instructions. Retailing skin care improves compliance by eliminating a few barriers to beginning the skin care regimen. I believe that the mindset of dermatologists needs to change: It is not about selling products to patients, it is about educating them on what to use and offering the products out of convenience and the desire to improve compliance.

Meadowbrook, Pa., dermatologist Michael A. Tomeo, MD, explained an obstacle faced by many dermatologists:

“I suspect, like many of my colleagues,” said Dr. Tomeo, “that I am held back in terms of salesmanship, having been trained in the traditional way. Physicians of my generation were taught to be ethical and professional and to focus on academic and clinical excellence, and salesmanship and advertising one’s services were frowned upon. It takes time to reset one’s former proclivities. Cosmeceuticals and nutraceuticals are revolutionizing the skin care world, and as experts in all things skin, we need to be well informed and offer our patients safe, effective, and cutting-edge treatments.”

4. Providers are concerned about product costs and time constraints

Providing excellent patient care and improving outcomes is at the forefront of our business, but financial concerns and time constraints prevent some doctors from offering skin care to their patients.

Rochester Hills, Mich., plastic surgeon Richard Hainer, MD, has found that “skin care is often too complex with too many products and is not very profitable.” For those reasons, Dr. Hainer has chosen not to retail skin care in his practice.

Nampa, Idaho, dermatologist Ryan S. Owsley, MD, explained that “the required minimum purchases by some of the product lines can leave the practice with expired product if it is not selling a particular line well. Cost can also be an issue for some patients in the area we are located.”

As a burn survivor and burn surgeon, Mark McDonough, MD, from Orlando “has a long history with skin care and rejuvenation. I did have a private label skin care line, including a moisturizer, a hydroquinone product, a retinol cream, and a sunscreen,” Dr. McDonough said. “However, and regrettably, I have not kept up with marketing and promotion, with most of my energy invested in trauma and disease survivors through a book, a blog, and my platform through my website.”

Doing your own product line is costly and spending the time and resources to promote it is not always possible. Buying the minimum order of products is often expensive, and you will not be able to sell them without a proven methodology in place. New products enter the market frequently, and it is expensive to always carry the latest technologies because new minimum orders must be met with each new brand that you add.

5. Selling skin care requires ongoing education

Properly recommending and retailing skin care involves physician, staff, and patient education. Unfortunately, most practices rely on training from the cosmeceutical sales reps who obviously have a brand bias. There is minimal unbiased “brand agnostic” skin care training for dermatologists and their staff. In fact, the AAD meeting has only a few skin care lectures in the program. Plastic surgeon Gaurav Bharti, MD, of Charlotte, N.C., explained that “motivating staff to help with retail skin care can be challenging. The first step is to get the staff familiar with the products with open discussions with the representatives. The next step has been to have the staff actually use the products and believe in them. Once they believe in the product, we have used an incentivization model that’s simple, transparent, and predictable.”

We are all too busy to spend adequate time with our patients, so it is critical that our staff be able to properly recommended skin care for us. We have to ensure that our staff is taking an ethical and scientific approach to skin care retail rather than a financial one. Rigorous staff training on how to match skin care products to skin type is the key to improving outcomes with skin care recommendations.

In a similar sense, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Richard Williams, MD, commented that “aestheticians often succumb to the desires of our patients to carry too many products in inventory, for which they do not have enough knowledge of the product’s benefits. This can be a very frustrating challenge.”

Conclusion

Although there are many obstacles to retailing skin care in your medical practice, the benefits that it provides to both your patients (improved outcomes) and your practice (increased profitability) far outweigh the challenges. I solved these pitfalls in my own practice by developing a standardized staff training program and skin care diagnostic software that is now used by over 100 medical practices. If you want to start retaining skin care, my advice is develop a training plan and a methodology for the recommendation and patient education process before you spend a lot of money on the required minimum product order. Feel free to contact me for advice. Alternatively, if you already do a great job of retailing skin care and want to provide tips to include in my American Society for Dermatologic Surgery course, contact me on LinkedIn or [email protected]. You can also find blogs I have written on skin care retail advice at STSFranchise.com.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014); she also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems.

Others believe that providing patients with the correct skin care product recommendations for their skin’s needs is a crucial step to improving outcomes and educating patients.

There is a wide range of challenges related to skin care retail that many physicians face. I will be running a course on Skin Care Retail at the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery meeting in October in Scottsdale, Ariz., if you want to learn more or share your opinions. I have surveyed plastic surgeons and dermatologists via LinkedIn about what they believe are some of the biggest pitfalls to retailing skin care. Here, I will share some of their insights and suggestions for overcoming these obstacles.

1. Patients are more knowledgeable about skin care than ever before

Facing an increasing number of over-the-counter skin care products available, as well as buzzwords like “organic ingredients” and “vegan,” patients are now bombarded with information from a variety of different sources. Because of this, patients come to the doctor with preconceived ideas that can affect compliance if their specific needs and beliefs are not properly addressed.

For New York plastic surgeon Sonita M. Sadio, MD, this is one of the reasons why she chooses not to sell skin care in her office.

“My practice is highly consultative, and ongoing skin care recommendations are a significant part of what I do to optimize patient outcomes,” Dr. Sadio said. “Patients are well-educated about skin care today. They know their ingredients and insist on clean formulations, free of certain ingredients, such as ‘cruelty-free’ and ‘vegan.’ Others feel deprived if they are not using an expensive product in elegant packaging. Still, others insist on drugstore favorites or ‘eco’ offerings and have their own sense of what that means. My job is to optimize the clinical outcome while also meeting these patients needs to ensure compliance.”

Not all doctors have the time, knowledge or desire to personally design each patient’s skin care regimen. Many delegate this to the staff. However, it is impossible to ensure that your staff matches patients to the proper products unless they have had extensive training on both skin care products and how to match them to the patient’s skin issues.

2. Patients are wary when the doctors sells only one product brand

Many studies have shown that, although consumers desire a choice when making purchases, they get overwhelmed if they are presented with too many options. One study showed that it is optimal to carry at least 3 brands of products. For this reason, limiting the skin care you sell to one brand or doing your own private label is not optimal.

New York dermatologist Rebecca Tamez, MD, pointed out the same problem when selling practice-specific skin care. “At my previous job, we sold skin care products directly to patients. I had no issues selling products that were readily available in drugstores or online (such as Vanicream and EltaMD). We usually sold these around the same cost as the drugstore or Amazon. However, it was harder to sell the practice-specific skin care line. I feel patients were more wary of these products.”

3. Doctors do not want to feel like salespeople

If you have read my Dermatology News columns in the past, you may know that I think it is unethical for dermatologists to not offer specific skin care advice to their patients. If patients do not get ethical and scientific recommendations from us, they will follow the advice of a friend or salesperson or purchase based on often inflated marketing claims.

Dermatologists often tell me: “I am not a cosmetic dermatologist so I do not sell skin care.” I feel strongly that general dermatologists should be giving specific written skin care recommendations for their patients too. Acne, rosacea, melasma, eczema, psoriasis, keratosis pilaris, and many other conditions will improve faster with an efficacious skin care regimen, assuming the patient is compliant with the instructions. Retailing skin care improves compliance by eliminating a few barriers to beginning the skin care regimen. I believe that the mindset of dermatologists needs to change: It is not about selling products to patients, it is about educating them on what to use and offering the products out of convenience and the desire to improve compliance.

Meadowbrook, Pa., dermatologist Michael A. Tomeo, MD, explained an obstacle faced by many dermatologists:

“I suspect, like many of my colleagues,” said Dr. Tomeo, “that I am held back in terms of salesmanship, having been trained in the traditional way. Physicians of my generation were taught to be ethical and professional and to focus on academic and clinical excellence, and salesmanship and advertising one’s services were frowned upon. It takes time to reset one’s former proclivities. Cosmeceuticals and nutraceuticals are revolutionizing the skin care world, and as experts in all things skin, we need to be well informed and offer our patients safe, effective, and cutting-edge treatments.”

4. Providers are concerned about product costs and time constraints

Providing excellent patient care and improving outcomes is at the forefront of our business, but financial concerns and time constraints prevent some doctors from offering skin care to their patients.

Rochester Hills, Mich., plastic surgeon Richard Hainer, MD, has found that “skin care is often too complex with too many products and is not very profitable.” For those reasons, Dr. Hainer has chosen not to retail skin care in his practice.

Nampa, Idaho, dermatologist Ryan S. Owsley, MD, explained that “the required minimum purchases by some of the product lines can leave the practice with expired product if it is not selling a particular line well. Cost can also be an issue for some patients in the area we are located.”

As a burn survivor and burn surgeon, Mark McDonough, MD, from Orlando “has a long history with skin care and rejuvenation. I did have a private label skin care line, including a moisturizer, a hydroquinone product, a retinol cream, and a sunscreen,” Dr. McDonough said. “However, and regrettably, I have not kept up with marketing and promotion, with most of my energy invested in trauma and disease survivors through a book, a blog, and my platform through my website.”

Doing your own product line is costly and spending the time and resources to promote it is not always possible. Buying the minimum order of products is often expensive, and you will not be able to sell them without a proven methodology in place. New products enter the market frequently, and it is expensive to always carry the latest technologies because new minimum orders must be met with each new brand that you add.

5. Selling skin care requires ongoing education

Properly recommending and retailing skin care involves physician, staff, and patient education. Unfortunately, most practices rely on training from the cosmeceutical sales reps who obviously have a brand bias. There is minimal unbiased “brand agnostic” skin care training for dermatologists and their staff. In fact, the AAD meeting has only a few skin care lectures in the program. Plastic surgeon Gaurav Bharti, MD, of Charlotte, N.C., explained that “motivating staff to help with retail skin care can be challenging. The first step is to get the staff familiar with the products with open discussions with the representatives. The next step has been to have the staff actually use the products and believe in them. Once they believe in the product, we have used an incentivization model that’s simple, transparent, and predictable.”

We are all too busy to spend adequate time with our patients, so it is critical that our staff be able to properly recommended skin care for us. We have to ensure that our staff is taking an ethical and scientific approach to skin care retail rather than a financial one. Rigorous staff training on how to match skin care products to skin type is the key to improving outcomes with skin care recommendations.

In a similar sense, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Richard Williams, MD, commented that “aestheticians often succumb to the desires of our patients to carry too many products in inventory, for which they do not have enough knowledge of the product’s benefits. This can be a very frustrating challenge.”

Conclusion

Although there are many obstacles to retailing skin care in your medical practice, the benefits that it provides to both your patients (improved outcomes) and your practice (increased profitability) far outweigh the challenges. I solved these pitfalls in my own practice by developing a standardized staff training program and skin care diagnostic software that is now used by over 100 medical practices. If you want to start retaining skin care, my advice is develop a training plan and a methodology for the recommendation and patient education process before you spend a lot of money on the required minimum product order. Feel free to contact me for advice. Alternatively, if you already do a great job of retailing skin care and want to provide tips to include in my American Society for Dermatologic Surgery course, contact me on LinkedIn or [email protected]. You can also find blogs I have written on skin care retail advice at STSFranchise.com.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014); she also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems.

MOC: ACOG’s role in developing a solution to the heated controversy

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) has decided to trade the phrase “maintenance of certification” (MOC) for “continuing board certification,” a seemingly minor change that has an important backstory. This is the story of how the physician community flexed its collective muscle and how the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) helped broker an important détente and pathway in a highly contentious issue.

Founded in 1933 as a nonprofit organization dedicated to maintaining high uniform standards among physicians, the ABMS and many of its specialty boards have found themselves, for more than a decade, under heavy fire from physicians (especially family physicians, internists, and surgeons), their 24 subspecialties, and the state medical societies representing them.

The ObGyn experience with the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG), however, is better for a number of reasons. Historically, ABOG and ACOG have worked closely together, which is an anomaly among boards as many boards have an arms-length or even an antagonistic relationship with their specialty society.

The discussion below outlines physician concerns with the ABMS and related boards and describes efforts to address and rebuild the continuing board certification process.

Direct and indirect costs

Physicians are very concerned with the costs involved in MOC. Measurable costs include testing fees, while indirect costs include time, stress, travel to test centers, and threats to livelihood for failing a high-stakes examination. Physicians want the high-stakes exam eliminated.

Relevance to practice

Physicians often feel that the MOC has little relevance to their practice, which fuels a sense of resentment toward boards that they believe are dominated by physicians who no longer practice. Subspecialists feel farther away from general practice and the base exams. Generalists feel that the exams miss the points of their daily practice.

Lack of data to show improved quality of care

Physicians want to know that the MOC is worth their time, effort, and money because it improves patient care. To date, however, empirical or clinical data on patient outcomes are absent or ambiguous; most studies lack high-level data or do not investigate the MOC requirements. Physicians want to know what the best MOC practices are, what improves care, and that practices that make no difference will be discarded. In addition, they want timely knowledge alerts when evidence changes.

Relationship to licensing, employment, privileging, credentialing, and reimbursement

Hospitals, insurers, and states increasingly—and inappropriately—use board certification as the primary (sometimes only) default measure of a physician’s fitness for patient care. Physicians without board certification often are denied hospital privileges, inclusion in insurance panels, and even medical licenses. This changes certification from a voluntary physician self-improvement exercise into a can’t-earn-a-living-without-it cudgel.

Variation

Boards vary significantly in their MOC requirements and costs. The importance of an equal standard across all boards is a clear theme among physician concerns.

Role and authority of the ABMS and related boards

Many physicians are frustrated with the perceived autocratic nature of their boards—boards that lack transparency, do not solicit or allow input from practicing physicians, and are unresponsive to physician concerns.

According to Susan Ramin, MD, ABOG Associate Executive Director, ABOG is leading in a number of these areas, including:

- rapidly disseminating clinical information on emerging topics, such as Zika virus infection and opioid misuse

- offering physician choice of testing categories

- exempting high scorers from the secured written exam, which saved physicians a total of $881,000 in exam fees

- crediting physicians for what they already are doing, including serving on maternal mortality review committees, participating in registries, and participating in the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)

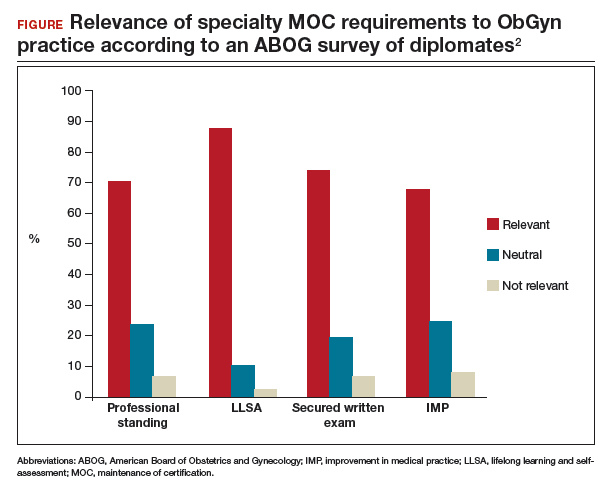

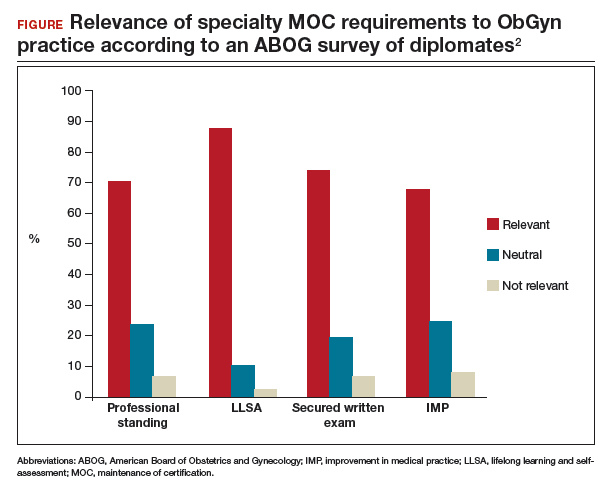

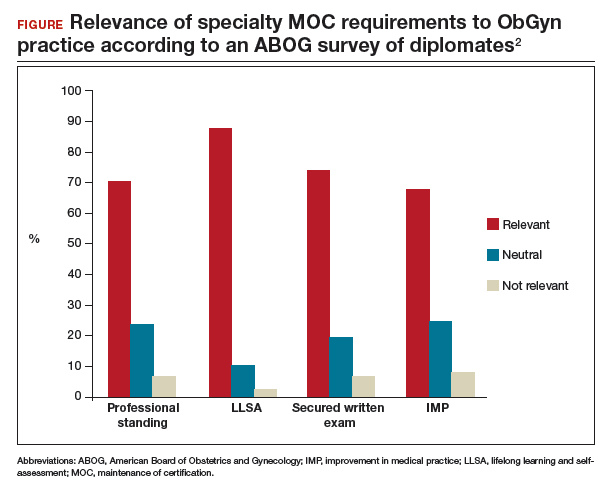

- providing Lifelong Learning and Self-Assessment (LLSA) articles that, according to 90% of diplomates surveyed, are beneficial to their clinical practice (FIGURE).1,2

Our colleague physicians are not so lucky. In a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine Perspective, one physician called out the American Board of Internal Medicine as “a private, self-appointed certifying organization,” a not-for-profit organization that has “grown into a $55-million-per-year business.”3 He concluded that “many physicians are waking up to the fact that our profession is increasingly controlled by people not directly involved in patient care who have lost contact with the realities of day-to-day clinical practice.”3

State and society responses to MOC requirements

Frustration with an inability to resolve these concerns has grown steadily, bubbling over into state governments. The American Medical Association developed “model state legislation intended to prohibit hospitals, health care insurers, and state boards of medicine and osteopathic medicine from requiring participation in MOC processes as a condition of credentialing, privileging, insurance panel participation, licensure, or licensure renewal.”4

Some states are proposing or have enacted legislation that prohibits the use of MOC as a criterion for licensure, privileging, employment, reimbursement, and/or insurance panel participation. Eight states (Arizona, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Maine, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee) have enacted laws to prohibit the use of MOC for initial and renewal licensure decisions. Many states are actively considering MOC-related legislation, including Alaska, Florida, Iowa, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Legislation is not the only outlet for physician frustration. Some medical specialty societies are considering dropping board certification as a membership requirement; physicians are exploring developing alternative boards; and some physicians are defying the board certification requirement altogether, with thousands signing anti-MOC petitions.

ACOG asserts importance of maintaining self-regulation

While other specialties are actively advocating state legislation, ACOG and ABOG have worked together to oppose state legislation, believing that physician self-regulation is paramount. In fact, in 2017, ACOG and ABOG issued a joint statement urging state lawmakers to “not interfere with our decades of successful self-regulation and to realize that each medical society has its own experience with its MOC program.”5

Negotiations lead to new initiative

This brings us to an interesting situation. ACOG’s Executive Vice President and CEO Hal Lawrence III, MD, was tapped (in his position as Chair of the Specialty Society CEO Consortium) to represent physician specialties in negotiations and discussions with the boards, which were represented by Lois Nora, MD, JD, President and CEO of the ABMS, and state medical societies, represented by Donald Palmisano Jr, JD, Executive Director and CEO of the Medical Association of Georgia. Many state medical societies, boards, and physician specialty organizations participated in these meetings.

Throughout months of debate, Dr. Lawrence urged his colleagues to stay at the table and do the hard work of reaching an agreement, rather than ask politicians to solve medicine’s problems. This approach was leveraged by the serious efforts and threats of state legislation, which brought the boards to the table. In August 2017, 41 state medical societies and 33 national medical specialty societies wrote to Dr. Nora expressing their concerns that “professional self-regulation is under attack. Concerns regarding the usefulness of the high-stakes exam, the exorbitant costs of the MOC process, and the lack of transparent communication from the certifying boards have led to damaging the MOC brand, and creating state-based attacks on the MOC process.”6

In December 2017, Dr. Lawrence and Mr. Palmisano led a meeting of principals from the national medical specialty societies and state medical societies with leaders of ABMS and 8 specialty boards, including ABOG, an opportunity to secure meaningful change. Dr. Lawrence began by stressing that the interests of physicians and patients would be best served by all parties coming together and collaborating on a meaningful solution, to repair trust and preserve physician self-regulation.

Dr. Ramin presented ABOG’s approach to continuous certification, lifelong learning, and self-assessment. The American Board of Urology and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology indicated that they were basing important changes in their MOC process on ABOG’s work, including using 5 modules (1 general and 4 specific to the physician’s practice) and multiple open-book mini-exams based on selected journal articles as an alternative to the 10-year MOC exam.

The Vision Initiative. At that meeting and others, the ABMS and other boards heard physicians’ candid and sometimes blunt concerns. Dr. Nora spoke to the recently announced Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future program, also known as the “Vision Initiative,” a process designed to fundamentally rebuild the continuing certification process with input and guidance from practicing physicians. Physician response seemed uniform: Seeing is believing.

Importantly, all participants at the December meeting agreed to work together to rebuild trust and ensure professionalism and professional self-regulation, reflected in this Statement of Shared Purpose:

ABMS certifying boards and national medical specialty societies will collaborate to resolve differences in the process of ongoing certification and to fulfill the principles of professional self-regulation, achieving appropriate standardization, and assuring that ongoing certification is relevant to the practices of physicians without undue burden. Furthermore, the boards and societies, and their organizations (ABMS and CMSS [Council of Medical Specialty Societies]), will undertake necessary changes in a timely manner, and will commit to ongoing communication with state medical associations to solicit their input.4

Two ObGyns participating in the Vision Initiative are Haywood Brown, MD, ACOG’s Immediate Past President, and George Wendel, MD, ABOG’s Executive Director. The Vision Initiative is composed of 3 parts. Part 1, Organization, is complete. The committee is currently working on part 2, Envisioning the Future, an information-gathering component that includes physician surveys, hearings, open solicited input, and identifying new and better approaches. After the final report is delivered to the ABMS in February 2019, part 3, Implementation, will begin.

The Vision Initiative offers physicians an important opportunity to help shape the future of continuing education and certification. ObGyns and other physicians should consider reviewing and commenting on the draft report, due in November, during the public comment period. Visit https://visioninitiative.org for more information and to sign up for email updates.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. From pilot to permanent: ABOG's program offering an innovative pathway integrating lifelong learning and self-assessment and external assessment is approved. https://www.abog.org/new/ABOG_PilotToPermanent.aspx. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- Ramin S. American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology MOC program. PowerPoint presentation; December 4, 2017.

- Teirstein PS. Boarded to death--why maintenance of certification is bad for doctors and patients. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):106-108.

- AMA Council on Medical Education. Executive summary. 2017. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/council-on-med-ed/a18-cme-02.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG-ABOG joint statement: political interference in physician maintenance of skills threatens women's health care. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/State-Legislative-Activities/2017ACOG-ABMS-MOC-Statement.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20180706T1615538746. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- Letter to Lois Nora, MD, JD. August 18, 2017. https://www.mainemed.com/sites/default/files/content/MOC%20Letter%20082117.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2018.

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) has decided to trade the phrase “maintenance of certification” (MOC) for “continuing board certification,” a seemingly minor change that has an important backstory. This is the story of how the physician community flexed its collective muscle and how the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) helped broker an important détente and pathway in a highly contentious issue.

Founded in 1933 as a nonprofit organization dedicated to maintaining high uniform standards among physicians, the ABMS and many of its specialty boards have found themselves, for more than a decade, under heavy fire from physicians (especially family physicians, internists, and surgeons), their 24 subspecialties, and the state medical societies representing them.

The ObGyn experience with the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG), however, is better for a number of reasons. Historically, ABOG and ACOG have worked closely together, which is an anomaly among boards as many boards have an arms-length or even an antagonistic relationship with their specialty society.

The discussion below outlines physician concerns with the ABMS and related boards and describes efforts to address and rebuild the continuing board certification process.

Direct and indirect costs

Physicians are very concerned with the costs involved in MOC. Measurable costs include testing fees, while indirect costs include time, stress, travel to test centers, and threats to livelihood for failing a high-stakes examination. Physicians want the high-stakes exam eliminated.

Relevance to practice

Physicians often feel that the MOC has little relevance to their practice, which fuels a sense of resentment toward boards that they believe are dominated by physicians who no longer practice. Subspecialists feel farther away from general practice and the base exams. Generalists feel that the exams miss the points of their daily practice.

Lack of data to show improved quality of care

Physicians want to know that the MOC is worth their time, effort, and money because it improves patient care. To date, however, empirical or clinical data on patient outcomes are absent or ambiguous; most studies lack high-level data or do not investigate the MOC requirements. Physicians want to know what the best MOC practices are, what improves care, and that practices that make no difference will be discarded. In addition, they want timely knowledge alerts when evidence changes.

Relationship to licensing, employment, privileging, credentialing, and reimbursement

Hospitals, insurers, and states increasingly—and inappropriately—use board certification as the primary (sometimes only) default measure of a physician’s fitness for patient care. Physicians without board certification often are denied hospital privileges, inclusion in insurance panels, and even medical licenses. This changes certification from a voluntary physician self-improvement exercise into a can’t-earn-a-living-without-it cudgel.

Variation

Boards vary significantly in their MOC requirements and costs. The importance of an equal standard across all boards is a clear theme among physician concerns.

Role and authority of the ABMS and related boards

Many physicians are frustrated with the perceived autocratic nature of their boards—boards that lack transparency, do not solicit or allow input from practicing physicians, and are unresponsive to physician concerns.

According to Susan Ramin, MD, ABOG Associate Executive Director, ABOG is leading in a number of these areas, including:

- rapidly disseminating clinical information on emerging topics, such as Zika virus infection and opioid misuse

- offering physician choice of testing categories

- exempting high scorers from the secured written exam, which saved physicians a total of $881,000 in exam fees

- crediting physicians for what they already are doing, including serving on maternal mortality review committees, participating in registries, and participating in the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)

- providing Lifelong Learning and Self-Assessment (LLSA) articles that, according to 90% of diplomates surveyed, are beneficial to their clinical practice (FIGURE).1,2

Our colleague physicians are not so lucky. In a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine Perspective, one physician called out the American Board of Internal Medicine as “a private, self-appointed certifying organization,” a not-for-profit organization that has “grown into a $55-million-per-year business.”3 He concluded that “many physicians are waking up to the fact that our profession is increasingly controlled by people not directly involved in patient care who have lost contact with the realities of day-to-day clinical practice.”3

State and society responses to MOC requirements

Frustration with an inability to resolve these concerns has grown steadily, bubbling over into state governments. The American Medical Association developed “model state legislation intended to prohibit hospitals, health care insurers, and state boards of medicine and osteopathic medicine from requiring participation in MOC processes as a condition of credentialing, privileging, insurance panel participation, licensure, or licensure renewal.”4

Some states are proposing or have enacted legislation that prohibits the use of MOC as a criterion for licensure, privileging, employment, reimbursement, and/or insurance panel participation. Eight states (Arizona, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Maine, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee) have enacted laws to prohibit the use of MOC for initial and renewal licensure decisions. Many states are actively considering MOC-related legislation, including Alaska, Florida, Iowa, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Legislation is not the only outlet for physician frustration. Some medical specialty societies are considering dropping board certification as a membership requirement; physicians are exploring developing alternative boards; and some physicians are defying the board certification requirement altogether, with thousands signing anti-MOC petitions.

ACOG asserts importance of maintaining self-regulation

While other specialties are actively advocating state legislation, ACOG and ABOG have worked together to oppose state legislation, believing that physician self-regulation is paramount. In fact, in 2017, ACOG and ABOG issued a joint statement urging state lawmakers to “not interfere with our decades of successful self-regulation and to realize that each medical society has its own experience with its MOC program.”5

Negotiations lead to new initiative

This brings us to an interesting situation. ACOG’s Executive Vice President and CEO Hal Lawrence III, MD, was tapped (in his position as Chair of the Specialty Society CEO Consortium) to represent physician specialties in negotiations and discussions with the boards, which were represented by Lois Nora, MD, JD, President and CEO of the ABMS, and state medical societies, represented by Donald Palmisano Jr, JD, Executive Director and CEO of the Medical Association of Georgia. Many state medical societies, boards, and physician specialty organizations participated in these meetings.

Throughout months of debate, Dr. Lawrence urged his colleagues to stay at the table and do the hard work of reaching an agreement, rather than ask politicians to solve medicine’s problems. This approach was leveraged by the serious efforts and threats of state legislation, which brought the boards to the table. In August 2017, 41 state medical societies and 33 national medical specialty societies wrote to Dr. Nora expressing their concerns that “professional self-regulation is under attack. Concerns regarding the usefulness of the high-stakes exam, the exorbitant costs of the MOC process, and the lack of transparent communication from the certifying boards have led to damaging the MOC brand, and creating state-based attacks on the MOC process.”6

In December 2017, Dr. Lawrence and Mr. Palmisano led a meeting of principals from the national medical specialty societies and state medical societies with leaders of ABMS and 8 specialty boards, including ABOG, an opportunity to secure meaningful change. Dr. Lawrence began by stressing that the interests of physicians and patients would be best served by all parties coming together and collaborating on a meaningful solution, to repair trust and preserve physician self-regulation.

Dr. Ramin presented ABOG’s approach to continuous certification, lifelong learning, and self-assessment. The American Board of Urology and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology indicated that they were basing important changes in their MOC process on ABOG’s work, including using 5 modules (1 general and 4 specific to the physician’s practice) and multiple open-book mini-exams based on selected journal articles as an alternative to the 10-year MOC exam.

The Vision Initiative. At that meeting and others, the ABMS and other boards heard physicians’ candid and sometimes blunt concerns. Dr. Nora spoke to the recently announced Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future program, also known as the “Vision Initiative,” a process designed to fundamentally rebuild the continuing certification process with input and guidance from practicing physicians. Physician response seemed uniform: Seeing is believing.

Importantly, all participants at the December meeting agreed to work together to rebuild trust and ensure professionalism and professional self-regulation, reflected in this Statement of Shared Purpose:

ABMS certifying boards and national medical specialty societies will collaborate to resolve differences in the process of ongoing certification and to fulfill the principles of professional self-regulation, achieving appropriate standardization, and assuring that ongoing certification is relevant to the practices of physicians without undue burden. Furthermore, the boards and societies, and their organizations (ABMS and CMSS [Council of Medical Specialty Societies]), will undertake necessary changes in a timely manner, and will commit to ongoing communication with state medical associations to solicit their input.4

Two ObGyns participating in the Vision Initiative are Haywood Brown, MD, ACOG’s Immediate Past President, and George Wendel, MD, ABOG’s Executive Director. The Vision Initiative is composed of 3 parts. Part 1, Organization, is complete. The committee is currently working on part 2, Envisioning the Future, an information-gathering component that includes physician surveys, hearings, open solicited input, and identifying new and better approaches. After the final report is delivered to the ABMS in February 2019, part 3, Implementation, will begin.