User login

The Pop That Stopped the Soccer Game

ANSWER

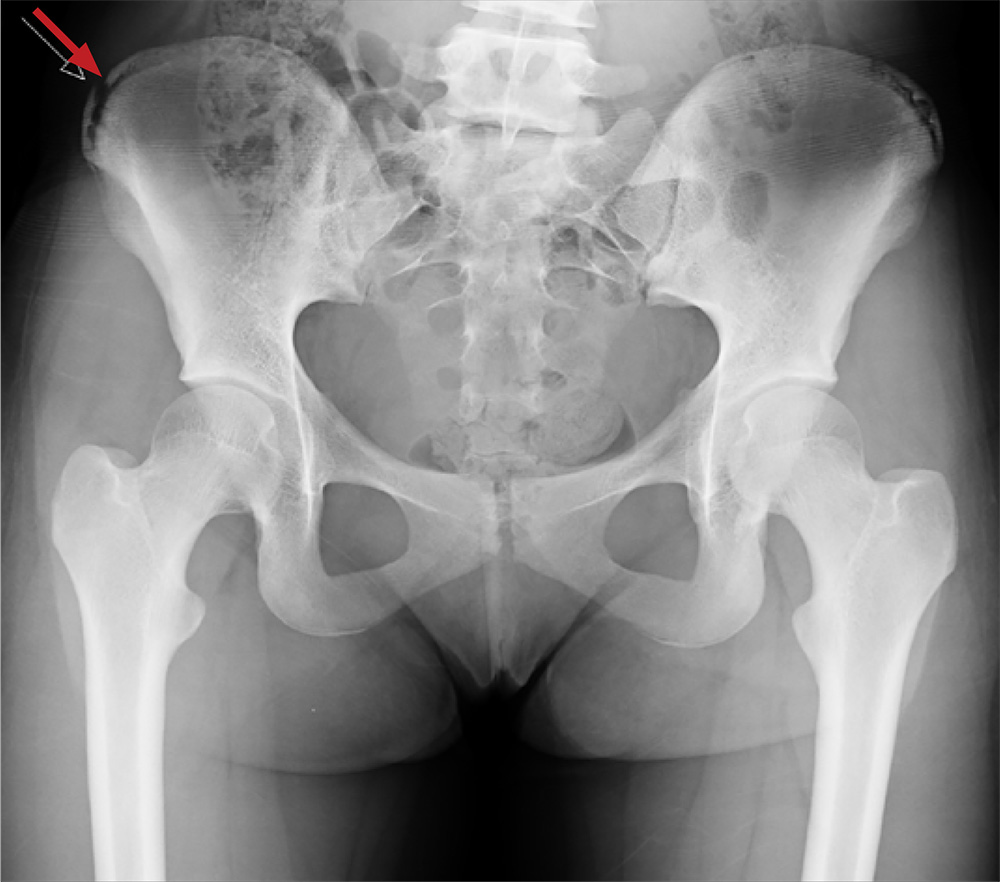

The radiograph shows an avulsion fracture of the right iliac crest. While the patient does have a growth plate in this location, there is asymmetry between the right and left sides.

Pelvic avulsion fractures can be easy to overlook and are often misdiagnosed as strains. Providers must remember that the pelvis serves as an insertion site for multiple muscles; in both adolescent and adult patients, certain activities (eg, sprinting, jumping, kicking) can increase tension and result in a bone avulsion. Affected patients typically report a popping sensation, pain with range of motion, and point tenderness over the fracture.

Avulsion fractures can usually be identified on x-ray; CT and MRI are used only when definitive diagnosis is unclear. Treatment consists of conservative management—rest, protected weight bearing, and physical therapy. Surgery is typically reserved for those with > 2 cm displacement of the fracture fragment.

In athletes, a gradual return to sports is advised, with full participation at four to 12 weeks postinjury. Possible complications include recurrent symptoms, prolonged healing time, nonunion, malunion, or hip weakness.

This patient was placed on crutches with non-weight-bearing status for one week. She used OTC pain medication as needed. The patient completed a four-week course of physical therapy and returned to full weight-bearing status. After six weeks, the patient had returned to full activity with pain-free range of motion and full strength.

ANSWER

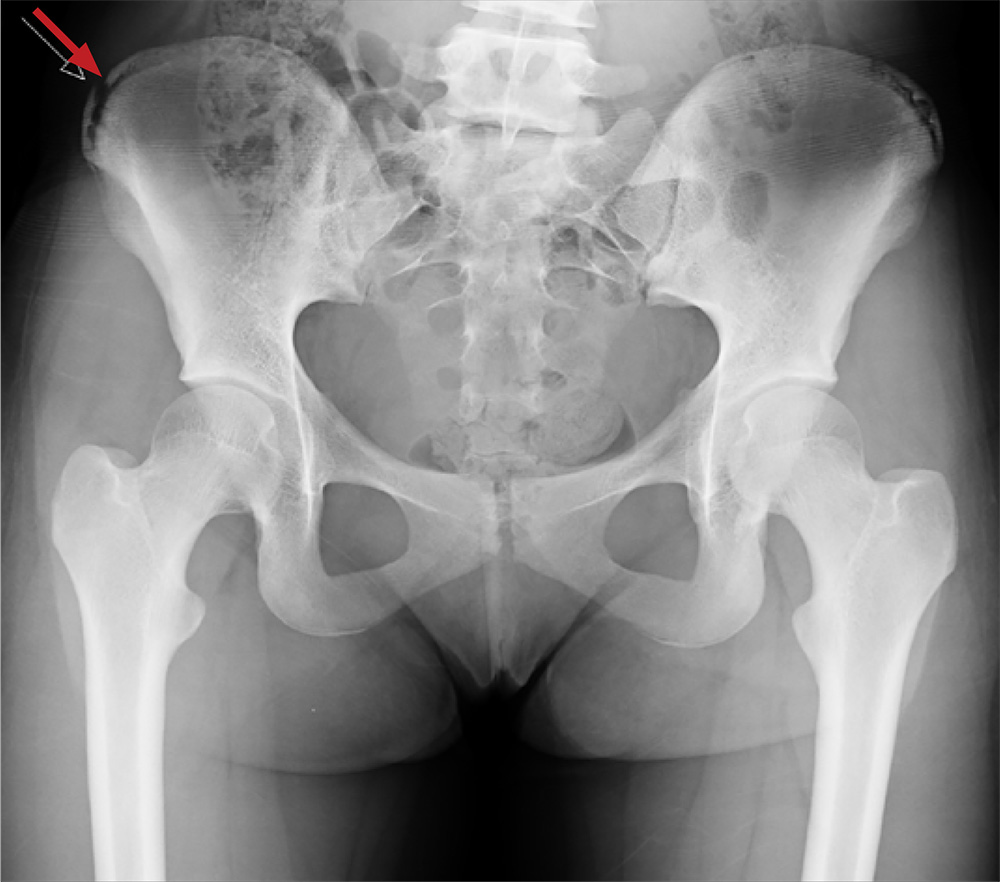

The radiograph shows an avulsion fracture of the right iliac crest. While the patient does have a growth plate in this location, there is asymmetry between the right and left sides.

Pelvic avulsion fractures can be easy to overlook and are often misdiagnosed as strains. Providers must remember that the pelvis serves as an insertion site for multiple muscles; in both adolescent and adult patients, certain activities (eg, sprinting, jumping, kicking) can increase tension and result in a bone avulsion. Affected patients typically report a popping sensation, pain with range of motion, and point tenderness over the fracture.

Avulsion fractures can usually be identified on x-ray; CT and MRI are used only when definitive diagnosis is unclear. Treatment consists of conservative management—rest, protected weight bearing, and physical therapy. Surgery is typically reserved for those with > 2 cm displacement of the fracture fragment.

In athletes, a gradual return to sports is advised, with full participation at four to 12 weeks postinjury. Possible complications include recurrent symptoms, prolonged healing time, nonunion, malunion, or hip weakness.

This patient was placed on crutches with non-weight-bearing status for one week. She used OTC pain medication as needed. The patient completed a four-week course of physical therapy and returned to full weight-bearing status. After six weeks, the patient had returned to full activity with pain-free range of motion and full strength.

ANSWER

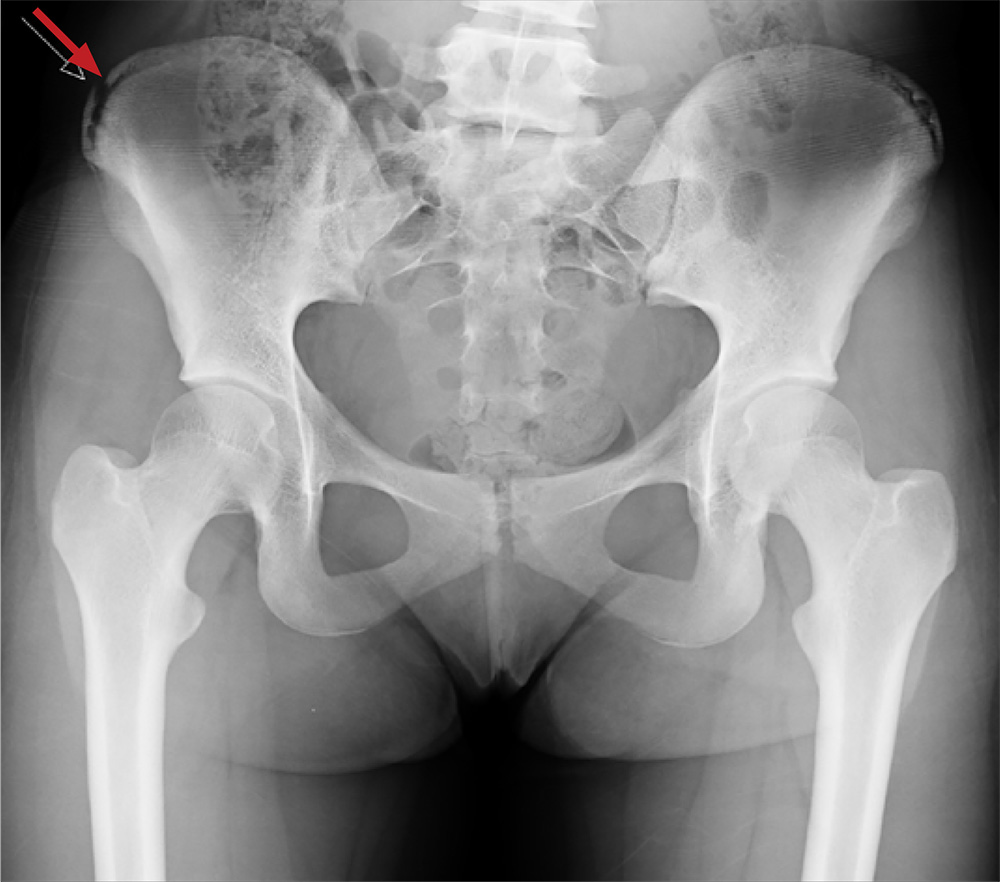

The radiograph shows an avulsion fracture of the right iliac crest. While the patient does have a growth plate in this location, there is asymmetry between the right and left sides.

Pelvic avulsion fractures can be easy to overlook and are often misdiagnosed as strains. Providers must remember that the pelvis serves as an insertion site for multiple muscles; in both adolescent and adult patients, certain activities (eg, sprinting, jumping, kicking) can increase tension and result in a bone avulsion. Affected patients typically report a popping sensation, pain with range of motion, and point tenderness over the fracture.

Avulsion fractures can usually be identified on x-ray; CT and MRI are used only when definitive diagnosis is unclear. Treatment consists of conservative management—rest, protected weight bearing, and physical therapy. Surgery is typically reserved for those with > 2 cm displacement of the fracture fragment.

In athletes, a gradual return to sports is advised, with full participation at four to 12 weeks postinjury. Possible complications include recurrent symptoms, prolonged healing time, nonunion, malunion, or hip weakness.

This patient was placed on crutches with non-weight-bearing status for one week. She used OTC pain medication as needed. The patient completed a four-week course of physical therapy and returned to full weight-bearing status. After six weeks, the patient had returned to full activity with pain-free range of motion and full strength.

A 13-year-old girl presents with her mother for evaluation of right hip pain following a soccer game two days ago. The patient says she felt a “pop” in her right hip while running and kicking the ball. She was escorted off the field, unable to finish the game.

Since then, she has had pain over the right superior pelvic region. She rates the pain as a 1/10 at rest but 7/10 with ambulation. She is unwilling to bear weight secondary to discomfort and has been using crutches provided by her trainer. She has been using ice and ibuprofen without relief. Her medical history is unremarkable.

On physical exam, you note a well-developed, well-nourished female in no acute distress. No ecchymosis, erythema, or abrasions can be seen on skin exam. The patient has point tenderness over the right iliac crest. She has mild pain and weakness with hip flexion and significant pain with abduction. The extremity is neurovascularly intact.

A pelvic radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

ESMO, ASCO seek improved cancer services

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have called for renewed political commitment to improve cancer services and reduce cancer deaths.

ASCO and ESMO issued a joint statement in which they asked heads of state and health ministers to attend the United Nations Civil Society Hearing on Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) in September and reconfirm their commitment to “pass legislation and invest in actions that will reduce the burden of NCDs, including cancer.”

Specifically, ESMO and ASCO said governments should:

- Implement the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution

- Develop and strengthen educational programs that provide lifestyle recommendations to reduce cancer risk (eg, prevent tobacco use, encourage healthy weight control, etc.)

- Develop efficient and cost-effective primary prevention measures (eg, Helicobacter pylori eradication)

- Ensure timely access to screening, early stage diagnosis, and treatment for all stages of cancer

- Strengthen health systems so they can provide cancer services to all who need them

- Provide essential secondary healthcare services that ensure an adequate number of well-trained oncology professionals who have access to necessary resources

- Aim to reduce premature mortality by 25% by 2025 and by 33% by 2030 across all NCDs.

“Recent UN and WHO reports1,2,3,4 note that, unless countries significantly scale-up their actions and investments, they will not meet agreed targets to reduce deaths from non-communicable diseases,” said ESMO President Josep Tabernero, MD, PhD.

“We are concerned that governments may find it easier to achieve their targets by reducing deaths from only some NCDs, leaving cancer patients behind. We believe there are cost-effective ways to improve cancer care and stand ready to assist countries in doing this by providing our expertise in cancer management to support implementation of the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution.”

“We urge member states to consider our joint call and amendments to strengthen the political declaration to be approved during the UN high-level meeting on 27 September and thus change the future outlook for cancer patients worldwide.”

1. United Nations Report by the Secretary General, Document A_72_662, 21 December 2017: http://www.who.int/ncds/governance/high-level-commission/A_72_662.pdf

2. World Health Assembly Report by the WHO Director General, Document WHA 71.2, 26 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_R2-en.pdf

3. WHO Independent High-Level Commission on NCDs Report, Time to Deliver, 1 June 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272710/9789241514163-eng.pdf?ua=1

4. WHO Report Saving Lives, Spending Less, 21 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272534/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.8-eng.pdf

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have called for renewed political commitment to improve cancer services and reduce cancer deaths.

ASCO and ESMO issued a joint statement in which they asked heads of state and health ministers to attend the United Nations Civil Society Hearing on Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) in September and reconfirm their commitment to “pass legislation and invest in actions that will reduce the burden of NCDs, including cancer.”

Specifically, ESMO and ASCO said governments should:

- Implement the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution

- Develop and strengthen educational programs that provide lifestyle recommendations to reduce cancer risk (eg, prevent tobacco use, encourage healthy weight control, etc.)

- Develop efficient and cost-effective primary prevention measures (eg, Helicobacter pylori eradication)

- Ensure timely access to screening, early stage diagnosis, and treatment for all stages of cancer

- Strengthen health systems so they can provide cancer services to all who need them

- Provide essential secondary healthcare services that ensure an adequate number of well-trained oncology professionals who have access to necessary resources

- Aim to reduce premature mortality by 25% by 2025 and by 33% by 2030 across all NCDs.

“Recent UN and WHO reports1,2,3,4 note that, unless countries significantly scale-up their actions and investments, they will not meet agreed targets to reduce deaths from non-communicable diseases,” said ESMO President Josep Tabernero, MD, PhD.

“We are concerned that governments may find it easier to achieve their targets by reducing deaths from only some NCDs, leaving cancer patients behind. We believe there are cost-effective ways to improve cancer care and stand ready to assist countries in doing this by providing our expertise in cancer management to support implementation of the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution.”

“We urge member states to consider our joint call and amendments to strengthen the political declaration to be approved during the UN high-level meeting on 27 September and thus change the future outlook for cancer patients worldwide.”

1. United Nations Report by the Secretary General, Document A_72_662, 21 December 2017: http://www.who.int/ncds/governance/high-level-commission/A_72_662.pdf

2. World Health Assembly Report by the WHO Director General, Document WHA 71.2, 26 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_R2-en.pdf

3. WHO Independent High-Level Commission on NCDs Report, Time to Deliver, 1 June 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272710/9789241514163-eng.pdf?ua=1

4. WHO Report Saving Lives, Spending Less, 21 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272534/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.8-eng.pdf

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have called for renewed political commitment to improve cancer services and reduce cancer deaths.

ASCO and ESMO issued a joint statement in which they asked heads of state and health ministers to attend the United Nations Civil Society Hearing on Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) in September and reconfirm their commitment to “pass legislation and invest in actions that will reduce the burden of NCDs, including cancer.”

Specifically, ESMO and ASCO said governments should:

- Implement the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution

- Develop and strengthen educational programs that provide lifestyle recommendations to reduce cancer risk (eg, prevent tobacco use, encourage healthy weight control, etc.)

- Develop efficient and cost-effective primary prevention measures (eg, Helicobacter pylori eradication)

- Ensure timely access to screening, early stage diagnosis, and treatment for all stages of cancer

- Strengthen health systems so they can provide cancer services to all who need them

- Provide essential secondary healthcare services that ensure an adequate number of well-trained oncology professionals who have access to necessary resources

- Aim to reduce premature mortality by 25% by 2025 and by 33% by 2030 across all NCDs.

“Recent UN and WHO reports1,2,3,4 note that, unless countries significantly scale-up their actions and investments, they will not meet agreed targets to reduce deaths from non-communicable diseases,” said ESMO President Josep Tabernero, MD, PhD.

“We are concerned that governments may find it easier to achieve their targets by reducing deaths from only some NCDs, leaving cancer patients behind. We believe there are cost-effective ways to improve cancer care and stand ready to assist countries in doing this by providing our expertise in cancer management to support implementation of the 2017 World Health Assembly Cancer Resolution.”

“We urge member states to consider our joint call and amendments to strengthen the political declaration to be approved during the UN high-level meeting on 27 September and thus change the future outlook for cancer patients worldwide.”

1. United Nations Report by the Secretary General, Document A_72_662, 21 December 2017: http://www.who.int/ncds/governance/high-level-commission/A_72_662.pdf

2. World Health Assembly Report by the WHO Director General, Document WHA 71.2, 26 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_R2-en.pdf

3. WHO Independent High-Level Commission on NCDs Report, Time to Deliver, 1 June 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272710/9789241514163-eng.pdf?ua=1

4. WHO Report Saving Lives, Spending Less, 21 May 2018: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272534/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.8-eng.pdf

FDA revises guidance on screening blood for Zika

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a revised guidance on testing donated blood and blood components for Zika virus.

The revised guidance states that it is no longer necessary to screen every donation individually.

Pooled donations can be tested for Zika virus in most cases, although, in areas where there is an increased risk of mosquito-borne transmission of Zika, donations should be tested individually.

The FDA said the revised guidance is a result of careful consideration of all available scientific evidence, including consultation with other public health agencies, and following the recommendations of the December 2017 meeting of the Blood Products Advisory Committee.

“When Zika virus first emerged, the unknown course of the epidemic and the observed severe effects from the disease indicated that individual donor testing was needed to ensure the continued safety of the blood supply,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“Now, given the significant decrease in cases of Zika virus infection in the US and its territories, we are moving away from testing each individual donation to testing pooled donations. This is usually more cost-effective and less burdensome for blood establishments. However, the FDA will continue to monitor the situation closely, and as appropriate, reconsider what measures are needed to maintain the safety of the blood supply.”

The FDA’s revised guidance replaces the August 2016 guidance, which recommended universal nucleic acid testing of individual units of blood donated in US states and territories.

The revised guidance explains that, to comply with applicable testing regulations, blood establishments must continue to test all donated whole blood and blood components for Zika virus using a nucleic acid test.

However, in many cases, pooled testing of donations using an FDA-licensed screening test is a sufficient method for complying with these regulations. If there is an increased risk of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus in a specific area, donations should be tested individually.

As an alternative to pooled or individual testing, blood establishments can use an FDA-approved pathogen-reduction device for plasma and certain platelet products.

The FDA said these recommendations will continue to ensure the safety of the US blood supply by reducing the risk of Zika virus transmission while also reducing the burden of testing for blood establishments.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a revised guidance on testing donated blood and blood components for Zika virus.

The revised guidance states that it is no longer necessary to screen every donation individually.

Pooled donations can be tested for Zika virus in most cases, although, in areas where there is an increased risk of mosquito-borne transmission of Zika, donations should be tested individually.

The FDA said the revised guidance is a result of careful consideration of all available scientific evidence, including consultation with other public health agencies, and following the recommendations of the December 2017 meeting of the Blood Products Advisory Committee.

“When Zika virus first emerged, the unknown course of the epidemic and the observed severe effects from the disease indicated that individual donor testing was needed to ensure the continued safety of the blood supply,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“Now, given the significant decrease in cases of Zika virus infection in the US and its territories, we are moving away from testing each individual donation to testing pooled donations. This is usually more cost-effective and less burdensome for blood establishments. However, the FDA will continue to monitor the situation closely, and as appropriate, reconsider what measures are needed to maintain the safety of the blood supply.”

The FDA’s revised guidance replaces the August 2016 guidance, which recommended universal nucleic acid testing of individual units of blood donated in US states and territories.

The revised guidance explains that, to comply with applicable testing regulations, blood establishments must continue to test all donated whole blood and blood components for Zika virus using a nucleic acid test.

However, in many cases, pooled testing of donations using an FDA-licensed screening test is a sufficient method for complying with these regulations. If there is an increased risk of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus in a specific area, donations should be tested individually.

As an alternative to pooled or individual testing, blood establishments can use an FDA-approved pathogen-reduction device for plasma and certain platelet products.

The FDA said these recommendations will continue to ensure the safety of the US blood supply by reducing the risk of Zika virus transmission while also reducing the burden of testing for blood establishments.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a revised guidance on testing donated blood and blood components for Zika virus.

The revised guidance states that it is no longer necessary to screen every donation individually.

Pooled donations can be tested for Zika virus in most cases, although, in areas where there is an increased risk of mosquito-borne transmission of Zika, donations should be tested individually.

The FDA said the revised guidance is a result of careful consideration of all available scientific evidence, including consultation with other public health agencies, and following the recommendations of the December 2017 meeting of the Blood Products Advisory Committee.

“When Zika virus first emerged, the unknown course of the epidemic and the observed severe effects from the disease indicated that individual donor testing was needed to ensure the continued safety of the blood supply,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“Now, given the significant decrease in cases of Zika virus infection in the US and its territories, we are moving away from testing each individual donation to testing pooled donations. This is usually more cost-effective and less burdensome for blood establishments. However, the FDA will continue to monitor the situation closely, and as appropriate, reconsider what measures are needed to maintain the safety of the blood supply.”

The FDA’s revised guidance replaces the August 2016 guidance, which recommended universal nucleic acid testing of individual units of blood donated in US states and territories.

The revised guidance explains that, to comply with applicable testing regulations, blood establishments must continue to test all donated whole blood and blood components for Zika virus using a nucleic acid test.

However, in many cases, pooled testing of donations using an FDA-licensed screening test is a sufficient method for complying with these regulations. If there is an increased risk of local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus in a specific area, donations should be tested individually.

As an alternative to pooled or individual testing, blood establishments can use an FDA-approved pathogen-reduction device for plasma and certain platelet products.

The FDA said these recommendations will continue to ensure the safety of the US blood supply by reducing the risk of Zika virus transmission while also reducing the burden of testing for blood establishments.

GOP Doctors Caucus seeks lower MIPS threshold

The House GOP Doctors Caucus is pushing officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid to lower the exclusion threshold for participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

In a letter to CMS Administrator Seema Verma, the lawmakers noted that about 60% of health care providers are excluded from MIPS – one track of the agency’s Quality Payment Program – mostly because of the high participation threshold set by the agency.

Since the program provides incentive payments to doctors by shifting Medicare Part B payments, the low participation is also lowering the payments available for high-level performance.

“The most notable ramification of the current threshold has been lower maximum positive updates on how MIPS ultimately adjusts Part B payments,” the lawmakers wrote. “For example, high performers are estimated to receive an aggregate payment adjustment in 2019 of 1.1% – based on their 2017 performance – even though adjustments of up to 4% are authorized.”

This payment trend “fails to incentivize meaningful participation in MIPS,” they wrote.

The current MIPS threshold excludes any physician or practice that generates $90,000 or less in Part B billing or sees 200 or fewer Medicare patients. The agency had initially set the threshold lower, at $30,000 or less in billing or 100 patients but created a larger exemption based on feedback from many physician groups.

The five members of the House GOP Doctors Caucus who signed on to the letter are Phil Roe (Tenn.), Andy Harris (Md.), Earl “Buddy” Carter (Ga.), Larry Bucshon (Ind.), and Scott DesJarlais (Tenn.).

The House GOP Doctors Caucus is pushing officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid to lower the exclusion threshold for participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

In a letter to CMS Administrator Seema Verma, the lawmakers noted that about 60% of health care providers are excluded from MIPS – one track of the agency’s Quality Payment Program – mostly because of the high participation threshold set by the agency.

Since the program provides incentive payments to doctors by shifting Medicare Part B payments, the low participation is also lowering the payments available for high-level performance.

“The most notable ramification of the current threshold has been lower maximum positive updates on how MIPS ultimately adjusts Part B payments,” the lawmakers wrote. “For example, high performers are estimated to receive an aggregate payment adjustment in 2019 of 1.1% – based on their 2017 performance – even though adjustments of up to 4% are authorized.”

This payment trend “fails to incentivize meaningful participation in MIPS,” they wrote.

The current MIPS threshold excludes any physician or practice that generates $90,000 or less in Part B billing or sees 200 or fewer Medicare patients. The agency had initially set the threshold lower, at $30,000 or less in billing or 100 patients but created a larger exemption based on feedback from many physician groups.

The five members of the House GOP Doctors Caucus who signed on to the letter are Phil Roe (Tenn.), Andy Harris (Md.), Earl “Buddy” Carter (Ga.), Larry Bucshon (Ind.), and Scott DesJarlais (Tenn.).

The House GOP Doctors Caucus is pushing officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid to lower the exclusion threshold for participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

In a letter to CMS Administrator Seema Verma, the lawmakers noted that about 60% of health care providers are excluded from MIPS – one track of the agency’s Quality Payment Program – mostly because of the high participation threshold set by the agency.

Since the program provides incentive payments to doctors by shifting Medicare Part B payments, the low participation is also lowering the payments available for high-level performance.

“The most notable ramification of the current threshold has been lower maximum positive updates on how MIPS ultimately adjusts Part B payments,” the lawmakers wrote. “For example, high performers are estimated to receive an aggregate payment adjustment in 2019 of 1.1% – based on their 2017 performance – even though adjustments of up to 4% are authorized.”

This payment trend “fails to incentivize meaningful participation in MIPS,” they wrote.

The current MIPS threshold excludes any physician or practice that generates $90,000 or less in Part B billing or sees 200 or fewer Medicare patients. The agency had initially set the threshold lower, at $30,000 or less in billing or 100 patients but created a larger exemption based on feedback from many physician groups.

The five members of the House GOP Doctors Caucus who signed on to the letter are Phil Roe (Tenn.), Andy Harris (Md.), Earl “Buddy” Carter (Ga.), Larry Bucshon (Ind.), and Scott DesJarlais (Tenn.).

For some opioid overdose survivors, stigma from clinicians hinders recovery

SAN DIEGO – After an opioid-related overdose, intentions to reduce opioid use or injection are often complicated by unmanaged withdrawal symptoms and perceptions of disrespect from first responders and/or hospital staff, results from a small, exploratory study suggest.

“The opportunity for getting someone out of an overdose experience and into harm reduction, medication-assisted treatment, whatever it may be, is great,” lead study author Luther C. Elliott, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “But the stigmatizing experiences of survivors tend to lead them in a beeline out of the emergency department.”

In an effort to better understand the impacts of nonfatal overdose on subsequent substance abuse patterns and overdose risk behaviors, Alex S. Bennett, PhD, Dr. Elliott, and Brett Wolfson-Stofko, PhD, interviewed 20 recent overdose survivors about their experiences. All study participants had been administered naloxone by a professional first responder and taken to an emergency department via ambulance. Next, the researchers juxtaposed their narratives with perspectives from nine emergency medical technicians (EMTs), six emergency department staff members, and six medical staff members.

“Each stakeholder was asked about their experiences with opioid-involved overdose and about the potential for staging effective interventions with persons who have been recently reversed,” explained Dr. Elliott, a medical anthropologist at the New York City–based National Development and Research Institutes.

The researchers found that 67% of EMT/emergency medical services (EMS) personnel had a history of discussing opioid-related overdose or need for treatment, while 57% had self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. For example, one EMT/EMS study participant described responding to overdose calls as taxing. “It takes away from what I would call real patients. …When I hear you took this drug by yourself and I have to go save [you], how is that fair?”

All nine emergency medicine physicians queried had a history of intervening and self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. One physician response was as follows: “If I’m going to see the same person over and over again, I’ve tried my best to help you and you go back to the same thing over and over again, at some point, I’m not going to have any compassion.”

Of the 20 survivors, 30% indicated no reported change in their behavioral disposition after the overdose, 10% reported delayed change, and 60% reported immediate change. Barriers to change, expressed by some of the survivors, included receiving higher doses of naloxone than necessary to reverse an opioid-related overdose, and perceived disrespect from emergency department staff. For example, one survivor contended that hospital staff “left me in the hallway. I kept asking for water and they’re like, ‘We have none.’ They brought me some ice chips finally to shut me up, because I kept trying to walk out.”

Dr. Elliott said he was surprised to learn how much EMS staff and emergency medicine physicians attempted informal interventions by just talking with survivors. “They’ve used a combination of shaming techniques, like, ‘Do you realize you almost died? You’ve got to stop using drugs.’ The stigmatizing attitudes combined with the willingness and the desire to intervene were most surprising to me.

In their abstract, he and his associates wrote that providing stakeholders “with even a brief general introduction to psychosocial interventions and sample scripts of supportive, motivational, and nonstigmatizing conversations between caregivers and the people experiencing opioid dependency may represent a positive advance in this direction.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors reported having no financial disclosures and said the study content is solely their responsibility – and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

SAN DIEGO – After an opioid-related overdose, intentions to reduce opioid use or injection are often complicated by unmanaged withdrawal symptoms and perceptions of disrespect from first responders and/or hospital staff, results from a small, exploratory study suggest.

“The opportunity for getting someone out of an overdose experience and into harm reduction, medication-assisted treatment, whatever it may be, is great,” lead study author Luther C. Elliott, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “But the stigmatizing experiences of survivors tend to lead them in a beeline out of the emergency department.”

In an effort to better understand the impacts of nonfatal overdose on subsequent substance abuse patterns and overdose risk behaviors, Alex S. Bennett, PhD, Dr. Elliott, and Brett Wolfson-Stofko, PhD, interviewed 20 recent overdose survivors about their experiences. All study participants had been administered naloxone by a professional first responder and taken to an emergency department via ambulance. Next, the researchers juxtaposed their narratives with perspectives from nine emergency medical technicians (EMTs), six emergency department staff members, and six medical staff members.

“Each stakeholder was asked about their experiences with opioid-involved overdose and about the potential for staging effective interventions with persons who have been recently reversed,” explained Dr. Elliott, a medical anthropologist at the New York City–based National Development and Research Institutes.

The researchers found that 67% of EMT/emergency medical services (EMS) personnel had a history of discussing opioid-related overdose or need for treatment, while 57% had self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. For example, one EMT/EMS study participant described responding to overdose calls as taxing. “It takes away from what I would call real patients. …When I hear you took this drug by yourself and I have to go save [you], how is that fair?”

All nine emergency medicine physicians queried had a history of intervening and self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. One physician response was as follows: “If I’m going to see the same person over and over again, I’ve tried my best to help you and you go back to the same thing over and over again, at some point, I’m not going to have any compassion.”

Of the 20 survivors, 30% indicated no reported change in their behavioral disposition after the overdose, 10% reported delayed change, and 60% reported immediate change. Barriers to change, expressed by some of the survivors, included receiving higher doses of naloxone than necessary to reverse an opioid-related overdose, and perceived disrespect from emergency department staff. For example, one survivor contended that hospital staff “left me in the hallway. I kept asking for water and they’re like, ‘We have none.’ They brought me some ice chips finally to shut me up, because I kept trying to walk out.”

Dr. Elliott said he was surprised to learn how much EMS staff and emergency medicine physicians attempted informal interventions by just talking with survivors. “They’ve used a combination of shaming techniques, like, ‘Do you realize you almost died? You’ve got to stop using drugs.’ The stigmatizing attitudes combined with the willingness and the desire to intervene were most surprising to me.

In their abstract, he and his associates wrote that providing stakeholders “with even a brief general introduction to psychosocial interventions and sample scripts of supportive, motivational, and nonstigmatizing conversations between caregivers and the people experiencing opioid dependency may represent a positive advance in this direction.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors reported having no financial disclosures and said the study content is solely their responsibility – and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

SAN DIEGO – After an opioid-related overdose, intentions to reduce opioid use or injection are often complicated by unmanaged withdrawal symptoms and perceptions of disrespect from first responders and/or hospital staff, results from a small, exploratory study suggest.

“The opportunity for getting someone out of an overdose experience and into harm reduction, medication-assisted treatment, whatever it may be, is great,” lead study author Luther C. Elliott, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “But the stigmatizing experiences of survivors tend to lead them in a beeline out of the emergency department.”

In an effort to better understand the impacts of nonfatal overdose on subsequent substance abuse patterns and overdose risk behaviors, Alex S. Bennett, PhD, Dr. Elliott, and Brett Wolfson-Stofko, PhD, interviewed 20 recent overdose survivors about their experiences. All study participants had been administered naloxone by a professional first responder and taken to an emergency department via ambulance. Next, the researchers juxtaposed their narratives with perspectives from nine emergency medical technicians (EMTs), six emergency department staff members, and six medical staff members.

“Each stakeholder was asked about their experiences with opioid-involved overdose and about the potential for staging effective interventions with persons who have been recently reversed,” explained Dr. Elliott, a medical anthropologist at the New York City–based National Development and Research Institutes.

The researchers found that 67% of EMT/emergency medical services (EMS) personnel had a history of discussing opioid-related overdose or need for treatment, while 57% had self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. For example, one EMT/EMS study participant described responding to overdose calls as taxing. “It takes away from what I would call real patients. …When I hear you took this drug by yourself and I have to go save [you], how is that fair?”

All nine emergency medicine physicians queried had a history of intervening and self-reported fatigue or burnout with opioid-related overdose patients. One physician response was as follows: “If I’m going to see the same person over and over again, I’ve tried my best to help you and you go back to the same thing over and over again, at some point, I’m not going to have any compassion.”

Of the 20 survivors, 30% indicated no reported change in their behavioral disposition after the overdose, 10% reported delayed change, and 60% reported immediate change. Barriers to change, expressed by some of the survivors, included receiving higher doses of naloxone than necessary to reverse an opioid-related overdose, and perceived disrespect from emergency department staff. For example, one survivor contended that hospital staff “left me in the hallway. I kept asking for water and they’re like, ‘We have none.’ They brought me some ice chips finally to shut me up, because I kept trying to walk out.”

Dr. Elliott said he was surprised to learn how much EMS staff and emergency medicine physicians attempted informal interventions by just talking with survivors. “They’ve used a combination of shaming techniques, like, ‘Do you realize you almost died? You’ve got to stop using drugs.’ The stigmatizing attitudes combined with the willingness and the desire to intervene were most surprising to me.

In their abstract, he and his associates wrote that providing stakeholders “with even a brief general introduction to psychosocial interventions and sample scripts of supportive, motivational, and nonstigmatizing conversations between caregivers and the people experiencing opioid dependency may represent a positive advance in this direction.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors reported having no financial disclosures and said the study content is solely their responsibility – and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AT CPDD 2018

Key clinical point: The majority of emergency medical services personnel and emergency department physicians indicated a history of attempting to discuss positive health change with overdose survivors.

Major finding: Of the 20 survivors interviewed, 30% indicated no reported change in their behavioral disposition after the overdose, 10% reported delayed change, and 60% reported immediate change.

Study details: An exploratory study of 20 opioid overdose survivors who were interviewed about their experiences.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Damned documentation

Sorry, but I can’t help you. What I can do is tell you you’re not alone. Datamania is now an endemic malady. Everybody has it and everybody’s doing it, even some you’d never imagine. If misery loves company, you should soon be head over heels.

1. Tiers for Tots

“What are the parents like?” I ask.

“They’re great!” Tracy says. “They want their kids to be creative and play.”

She frowns. “But my boss insists I give him data.”

“Data? What data?”

“Studies show that letter recognition in kindergarten correlates with reading ability in third grade,” she says. “So I have to test the kids and provide him with the data.”

“And what if the kids flub letter recognition?”

Tracy’s smile is now rueful. “Then they might need a Tier 2 intervention.”

“Good grief! What is a Tier 2 intervention?”

“It’s time consuming,” she says. “It takes a lot of one-on-one work, me and the kid.”

Less play all around, I guess. But documentation must be done, and data delivered. By the kindergarten teacher!

2. Filing for firefighters

Bruce has been a firefighter for 30 years, and it’s starting to wear him down. The physical exertion? The stress? Nah.

“The paperwork is driving me crazy,” he says.

“What paperwork?”

“In between calls, we spend hours filling out forms,” he says.

“Which forms?”

“At the scene, you go to work on the fire and help people get to safety. Then you see how they’re doing, and refer the ones who need it for medical help.

“Used to be,” says Bruce, “that you’d eyeball someone, ask them how they felt and if they needed to go to the hospital. If they said they were OK, they were good to leave.”

“And now?”

“Now we have to cover ourselves. We need to document how they look, what they say, what we asked them, what they answered. They have to sign a release that we asked them what we needed to ask and they answered what we needed to hear, that they said they were OK and didn’t need to go to the ER and signed off on it. Takes a lot of time.”

And paper. Maybe little kids who used to dream of being firefighters will start to dream that they’ll be file clerks with big red hats.

3. Your personal banker doesn’t know you!

Marina looks frazzled. “Stress at work,” she says. “It gets worse all the time.”

I know Marina works at a community bank. “What’s the problem?” I ask. “More restrictions on lending?”

“Oh sure,” she says, “but that’s an old story. Now there are new regulations to prevent money laundering. We have to know the identity of anybody who makes a deposit.”

“Sounds reasonable.”

“In principle sure,” she says. “But in practice what happens is this: Somebody wants to make any change – to add a relative, upgrade to a newer checking account. Even if they’ve been our depositors for 20 years, we have to ask them to produce all kinds of personal information for us to show regulators if they ask if we know people we’ve known forever.”

“Do the regulators ever ask?”

“Of course not,” says Marina. “But we have to fill out the forms, which take all day.”

It’s everywhere, folks. Bureaucratization is pervasive. No one can escape. Where is Franz Kafka now that we need him?

We in medicine know this all too well, of course. Perhaps the leading cause of physician retirement is introducing EHR into the institutions they work at.

There are, of course, always reasons and justifications for bureaucratic rules. You know them all, and it doesn’t matter. Fish gotta swim and clerks gotta file. Besides, it is now an article of faith that from large data sets shall go forth great wisdom. In precision medicine. Also, in kindergarten.

Sorry, but I have to go. I’m doing my charts, and there are templates to paste and boilers to plate.

As the apocryphal cardiologist may have said, “Hey, things could be worse. I could be younger.”

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Sorry, but I can’t help you. What I can do is tell you you’re not alone. Datamania is now an endemic malady. Everybody has it and everybody’s doing it, even some you’d never imagine. If misery loves company, you should soon be head over heels.

1. Tiers for Tots

“What are the parents like?” I ask.

“They’re great!” Tracy says. “They want their kids to be creative and play.”

She frowns. “But my boss insists I give him data.”

“Data? What data?”

“Studies show that letter recognition in kindergarten correlates with reading ability in third grade,” she says. “So I have to test the kids and provide him with the data.”

“And what if the kids flub letter recognition?”

Tracy’s smile is now rueful. “Then they might need a Tier 2 intervention.”

“Good grief! What is a Tier 2 intervention?”

“It’s time consuming,” she says. “It takes a lot of one-on-one work, me and the kid.”

Less play all around, I guess. But documentation must be done, and data delivered. By the kindergarten teacher!

2. Filing for firefighters

Bruce has been a firefighter for 30 years, and it’s starting to wear him down. The physical exertion? The stress? Nah.

“The paperwork is driving me crazy,” he says.

“What paperwork?”

“In between calls, we spend hours filling out forms,” he says.

“Which forms?”

“At the scene, you go to work on the fire and help people get to safety. Then you see how they’re doing, and refer the ones who need it for medical help.

“Used to be,” says Bruce, “that you’d eyeball someone, ask them how they felt and if they needed to go to the hospital. If they said they were OK, they were good to leave.”

“And now?”

“Now we have to cover ourselves. We need to document how they look, what they say, what we asked them, what they answered. They have to sign a release that we asked them what we needed to ask and they answered what we needed to hear, that they said they were OK and didn’t need to go to the ER and signed off on it. Takes a lot of time.”

And paper. Maybe little kids who used to dream of being firefighters will start to dream that they’ll be file clerks with big red hats.

3. Your personal banker doesn’t know you!

Marina looks frazzled. “Stress at work,” she says. “It gets worse all the time.”

I know Marina works at a community bank. “What’s the problem?” I ask. “More restrictions on lending?”

“Oh sure,” she says, “but that’s an old story. Now there are new regulations to prevent money laundering. We have to know the identity of anybody who makes a deposit.”

“Sounds reasonable.”

“In principle sure,” she says. “But in practice what happens is this: Somebody wants to make any change – to add a relative, upgrade to a newer checking account. Even if they’ve been our depositors for 20 years, we have to ask them to produce all kinds of personal information for us to show regulators if they ask if we know people we’ve known forever.”

“Do the regulators ever ask?”

“Of course not,” says Marina. “But we have to fill out the forms, which take all day.”

It’s everywhere, folks. Bureaucratization is pervasive. No one can escape. Where is Franz Kafka now that we need him?

We in medicine know this all too well, of course. Perhaps the leading cause of physician retirement is introducing EHR into the institutions they work at.

There are, of course, always reasons and justifications for bureaucratic rules. You know them all, and it doesn’t matter. Fish gotta swim and clerks gotta file. Besides, it is now an article of faith that from large data sets shall go forth great wisdom. In precision medicine. Also, in kindergarten.

Sorry, but I have to go. I’m doing my charts, and there are templates to paste and boilers to plate.

As the apocryphal cardiologist may have said, “Hey, things could be worse. I could be younger.”

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Sorry, but I can’t help you. What I can do is tell you you’re not alone. Datamania is now an endemic malady. Everybody has it and everybody’s doing it, even some you’d never imagine. If misery loves company, you should soon be head over heels.

1. Tiers for Tots

“What are the parents like?” I ask.

“They’re great!” Tracy says. “They want their kids to be creative and play.”

She frowns. “But my boss insists I give him data.”

“Data? What data?”

“Studies show that letter recognition in kindergarten correlates with reading ability in third grade,” she says. “So I have to test the kids and provide him with the data.”

“And what if the kids flub letter recognition?”

Tracy’s smile is now rueful. “Then they might need a Tier 2 intervention.”

“Good grief! What is a Tier 2 intervention?”

“It’s time consuming,” she says. “It takes a lot of one-on-one work, me and the kid.”

Less play all around, I guess. But documentation must be done, and data delivered. By the kindergarten teacher!

2. Filing for firefighters

Bruce has been a firefighter for 30 years, and it’s starting to wear him down. The physical exertion? The stress? Nah.

“The paperwork is driving me crazy,” he says.

“What paperwork?”

“In between calls, we spend hours filling out forms,” he says.

“Which forms?”

“At the scene, you go to work on the fire and help people get to safety. Then you see how they’re doing, and refer the ones who need it for medical help.

“Used to be,” says Bruce, “that you’d eyeball someone, ask them how they felt and if they needed to go to the hospital. If they said they were OK, they were good to leave.”

“And now?”

“Now we have to cover ourselves. We need to document how they look, what they say, what we asked them, what they answered. They have to sign a release that we asked them what we needed to ask and they answered what we needed to hear, that they said they were OK and didn’t need to go to the ER and signed off on it. Takes a lot of time.”

And paper. Maybe little kids who used to dream of being firefighters will start to dream that they’ll be file clerks with big red hats.

3. Your personal banker doesn’t know you!

Marina looks frazzled. “Stress at work,” she says. “It gets worse all the time.”

I know Marina works at a community bank. “What’s the problem?” I ask. “More restrictions on lending?”

“Oh sure,” she says, “but that’s an old story. Now there are new regulations to prevent money laundering. We have to know the identity of anybody who makes a deposit.”

“Sounds reasonable.”

“In principle sure,” she says. “But in practice what happens is this: Somebody wants to make any change – to add a relative, upgrade to a newer checking account. Even if they’ve been our depositors for 20 years, we have to ask them to produce all kinds of personal information for us to show regulators if they ask if we know people we’ve known forever.”

“Do the regulators ever ask?”

“Of course not,” says Marina. “But we have to fill out the forms, which take all day.”

It’s everywhere, folks. Bureaucratization is pervasive. No one can escape. Where is Franz Kafka now that we need him?

We in medicine know this all too well, of course. Perhaps the leading cause of physician retirement is introducing EHR into the institutions they work at.

There are, of course, always reasons and justifications for bureaucratic rules. You know them all, and it doesn’t matter. Fish gotta swim and clerks gotta file. Besides, it is now an article of faith that from large data sets shall go forth great wisdom. In precision medicine. Also, in kindergarten.

Sorry, but I have to go. I’m doing my charts, and there are templates to paste and boilers to plate.

As the apocryphal cardiologist may have said, “Hey, things could be worse. I could be younger.”

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Investigational solriamfetol may improve multiple sleep measures

BALTIMORE – Multiple studies based on phase 3 clinical trials of the investigational drug solriamfetol have found that it may be effective for improving next-day wakefulness and work productivity in people with narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea, and that the drug can maintain its effect throughout the day as well as for up to 6 months, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Solriamfetol, developed by Jazz Pharmaceuticals, is the subject of a new drug application accepted by the Food and Drug Administration in March of 2018 for the treatment of excessive sleepiness due to narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Solriamfetol is a selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

The drug was the subject of four different studies presented at SLEEP 2018 that drilled down into its effect on specific aspects of narcolepsy or OSA, or both. One study explored results in narcoleptic patients with and without cataplexy. Another study investigated the drug’s maintenance of efficacy after 6 months of treatment. A third study looked at the drug’s impact on next-day function, work productivity, and quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. And the fourth study researched how solriamfetol helped maintain wakefulness throughout the day.

Yves Dauvilliers, MD, reported that the 150- and 300-mg doses of solriamfetol were effective in improving both sleep latency, as measured with maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores in both cataplexic (n = 117) and noncataplexic (n = 114) narcolepsy. The objective of the study was to reevaluate the safety of solriamfetol in these narcoleptic subgroups from the phase 3 trial, said Dr. Dauvilliers, a faculty member at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montpellier (France).

In patients with cataplexy, the 150-mg dose increased sleep latency from a baseline of 0 to 7.9 after a week and sustained that for 12 weeks; doubling the dose raised that to 10.3 after a week, reaching 10.7 in week 12. Gains were even more dramatic in noncataplexic patients, with the 150-mg dose improving sleep latency to 12.8 at week 1 and 11.6 at week 12, and the 300-mg dose resulting in a gain of 16.8 after a week, trailing off to 13.8 after 12 weeks, Dr. Dauvilliers said.

The study also evaluated ESS scores for three dosing levels – 75, 150, and 300 mg – plus placebo. In the group with cataplexy, ESS at week 12 improved from a baseline of 0 to –3.1, –5.6, and –6.3 for the three dosing groups, respectively, vs. –1.8 for placebo. In the noncataplexy patients with narcolepsy, the improvements in ESS at week 12 were –4.5, –5.2 and –6.4, respectively, vs. –1.5 for placebo.

“At 150 mg and 300 mg, solriamfetol seems to be very effective in treating excessive sleepiness with narcolepsy, with the same efficacy in the group with and without cataplexy – with efficacy even after just 1 week of treatment,” Dr. Dauvilliers said.

Atul Malhotra, MD, and his coresearchers investigated the long-term safety and efficacy of solriamfetol out to 42 weeks in patients with narcolepsy or OSA who completed previous clinical trials, which were 6- and 12-week trials. The study involved an open-label phase from weeks 14 to 27, a 2-week randomized withdrawal phase and then safety follow-up after week 40. In the open-label phase, ESS scores for the overall treatment group (n = 519) improved from 15.9 at baseline to 8.3 at week 40, with variation between the OSA (n = 333) and narcolepsy (n = 186) groups: from 15.2 at baseline to 6.5 at week 40 for the former and from 17.3 to 11.4 for the latter.

In the randomized withdrawal phase, ESS scores for those on solriamfetol (n = 139) migrated upward from 7.3 to 8.5 – but for the placebo group (n = 141) ESS rose from 7.8 to 12.6, a difference of 3.7 favoring the treatment group, said Dr. Malhotra, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine and the Kenneth M. Moser Professor in the department of medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. Most patients in the placebo group had worsening of symptoms based on global impression of change – 64.5% vs. 28.2% in the treatment group in the self-reported cohort, and 63.8% vs. 28.7% in the clinician-evaluated cohort.

“The open-label phase demonstrated maintenance-of-efficacy after 1 year,” Dr. Malhotra said. “The safety profile was consistent with prior placebo-controlled studies of solriamfetol. Epworth sleepiness score and adverse event data demonstrated a lack of rebound sleepiness or withdrawal after abrupt discontinuation of solriamfetol during the randomized washout phase. So the bottom line is it looks to be a durable, effective treatment without major side effects.”

Helene A. Emsellem, MD, led a study into how solriamfetol can impact daily activity in patients with narcolepsy. “Solriamfetol at 300 mg reduced activity impairment outside the workplace and, at 150 mg, reduced activity and work impairment from baseline to week 12 on the measures of functionality at work and in private life,” said Dr. Emsellem, of George Washington University Medical Center, Washington. She is medical director of the Center for Sleep & Wake Disorders, Chevy Chase, Md.

Patients on 300 mg solriamfetol (n = 43) gained an average 3.01 on the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire short version (FOSQ-10) total score from baseline to week 12. That compares with gains of 2.57 in the 150-mg group (n = 51), 2.39 in the 75-mg group (n = 49), and 1.56 in the placebo group (n = 52, P = .05). The study looked at activity across four different measures in terms of reduced impairment, as measured by percentage reductions in the negative. The 150-mg group showed most improvement in impairment while working and overall work impairment, with changes of –22.02% and –19.77%, respectively, vs. –11.62% and –10.59% for the 300-mg dose. However, the higher dose showed greater improvement in general activity impairment: –21.17% vs. –17.84% in the 150-mg dose (P less than .05).

Notably, there was little difference across the dosing groups in improvement in work time missed, “I think mostly because there wasn’t much absenteeism to start with,” Dr. Emsellem said.

The 300-mg group also showed greater gains in physical component summary, based on answers to the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, averaging a gain of 3.29 from baseline vs. 2.65 for 150 mg, 2.54 for 75 mg, and 1.06 for placebo. However, on the mental component summary of the survey, the 300-mg group showed the smallest increase: 0.68 vs. 2.05 (150 mg), 1.55 (75 mg), and 0.78 (placebo), respectively (P less than . 05).

In reporting on the effects of solriamfetol through the day, Paula K. Schweitzer, PhD, director of research at the Sleep Medicine and Research Center at St. Luke’s Hospital, Chesterfield, Mo., noted that sustained full-day efficacy may be a limitation of other wake-promoting medications (Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:252-57; Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:761-74). The objective of her study was to evaluate the efficacy of solriamfetol through the day over five sequential MWT trials. Her research involved two double-blind, 12-week studies in patients with either narcolepsy (n = 231) or OSA (n = 459) who were randomized to placebo or one of four doses of solriamfetol: 37.5 mg (in OSA only) and 75, 150, and 300 mg. Patients took the drug orally in the morning.

“Solriamfetol significantly increased sleep latency on all five sequential MWT trials at doses of 150 and 300 mg in the narcolepsy patients, and at doses of 75, 150, and 300 mg in the OSA patients.” Dr. Schweitzer said.

The 150- and 300-mg doses showed the greatest improvement over smaller doses and placebo in both the narcolepsy and OSA groups. In the narcolepsy patients, changes from baseline in MWT sleep latency in the first trial, at approximately 1 hour post dose, were 9.9 (150 mg), 9.9 (300 mg), and –0.6 (placebo) minutes; and in the fifth trial, approximately 9 hours post dose, were 9.3 (150 mg), 12.3 (300 mg), and 3.1 (placebo) minutes. In the OSA patients, changes from baseline in the first trial were 10.9 (150 mg), 12.5 (300 mg), and –0.4 (placebo) minutes; and in the fifth trial, changes were 8.1 (150 mg), 7.6 (300 mg), and 0.2 (placebo) minutes.

“These data demonstrate sustained efficacy over approximately 9 hours following morning dosing for solriamfetol at 150-300 mg in narcolepsy patients and 75-300 mg in OSA patients.” Dr. Schweitzer said.

She also noted that rates of insomnia through the day were less than 5% in each study population combined across dose groups.

Reporting of adverse events was similar across treatment groups in all four studies. The most common adverse event was headache, ranging from around 10% for OSA to 24.2% in patients with cataplexic narcolepsy (n = 91), followed by nausea, decreased appetite, anxiety, and nasopharyngitis. Dr. Malhotra’s study, which involved the largest population of OSA (n = 417) and narcolepsy (n = 226) patients, showed overall rates of at least one adverse event of 75.1% and 74.8%, respectively. His study also showed an overall rate of 5% for respiratory tract infection, and nine patients (1.4%) who had serious cardiovascular adverse events – two cases of atrial fibrillation, and one each of acute MI, angina pectoris, chest discomfort, chest pain, noncardiac chest pain, cerebrovascular accident, and pulmonary embolism.

Dr. Schweitzer noted that the adverse events were mild to moderate in severity, with discontinuation rates of 5% to 7% in the treatment group. Dr. Dauvilliers said the safety results were consistent with previous studies.

All four researchers reported receiving grant/research support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, sponsor of the study.

SOURCE: Dauvilliers Y et al. Abstract 0619; Malhotra A et al. Abstract 0620; Emsellem H et al. Abstract 0621; Schweitzer PK et al. Abstract 0622. Presented at Sleep 2018.

BALTIMORE – Multiple studies based on phase 3 clinical trials of the investigational drug solriamfetol have found that it may be effective for improving next-day wakefulness and work productivity in people with narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea, and that the drug can maintain its effect throughout the day as well as for up to 6 months, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Solriamfetol, developed by Jazz Pharmaceuticals, is the subject of a new drug application accepted by the Food and Drug Administration in March of 2018 for the treatment of excessive sleepiness due to narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Solriamfetol is a selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

The drug was the subject of four different studies presented at SLEEP 2018 that drilled down into its effect on specific aspects of narcolepsy or OSA, or both. One study explored results in narcoleptic patients with and without cataplexy. Another study investigated the drug’s maintenance of efficacy after 6 months of treatment. A third study looked at the drug’s impact on next-day function, work productivity, and quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. And the fourth study researched how solriamfetol helped maintain wakefulness throughout the day.

Yves Dauvilliers, MD, reported that the 150- and 300-mg doses of solriamfetol were effective in improving both sleep latency, as measured with maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores in both cataplexic (n = 117) and noncataplexic (n = 114) narcolepsy. The objective of the study was to reevaluate the safety of solriamfetol in these narcoleptic subgroups from the phase 3 trial, said Dr. Dauvilliers, a faculty member at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montpellier (France).

In patients with cataplexy, the 150-mg dose increased sleep latency from a baseline of 0 to 7.9 after a week and sustained that for 12 weeks; doubling the dose raised that to 10.3 after a week, reaching 10.7 in week 12. Gains were even more dramatic in noncataplexic patients, with the 150-mg dose improving sleep latency to 12.8 at week 1 and 11.6 at week 12, and the 300-mg dose resulting in a gain of 16.8 after a week, trailing off to 13.8 after 12 weeks, Dr. Dauvilliers said.

The study also evaluated ESS scores for three dosing levels – 75, 150, and 300 mg – plus placebo. In the group with cataplexy, ESS at week 12 improved from a baseline of 0 to –3.1, –5.6, and –6.3 for the three dosing groups, respectively, vs. –1.8 for placebo. In the noncataplexy patients with narcolepsy, the improvements in ESS at week 12 were –4.5, –5.2 and –6.4, respectively, vs. –1.5 for placebo.

“At 150 mg and 300 mg, solriamfetol seems to be very effective in treating excessive sleepiness with narcolepsy, with the same efficacy in the group with and without cataplexy – with efficacy even after just 1 week of treatment,” Dr. Dauvilliers said.

Atul Malhotra, MD, and his coresearchers investigated the long-term safety and efficacy of solriamfetol out to 42 weeks in patients with narcolepsy or OSA who completed previous clinical trials, which were 6- and 12-week trials. The study involved an open-label phase from weeks 14 to 27, a 2-week randomized withdrawal phase and then safety follow-up after week 40. In the open-label phase, ESS scores for the overall treatment group (n = 519) improved from 15.9 at baseline to 8.3 at week 40, with variation between the OSA (n = 333) and narcolepsy (n = 186) groups: from 15.2 at baseline to 6.5 at week 40 for the former and from 17.3 to 11.4 for the latter.

In the randomized withdrawal phase, ESS scores for those on solriamfetol (n = 139) migrated upward from 7.3 to 8.5 – but for the placebo group (n = 141) ESS rose from 7.8 to 12.6, a difference of 3.7 favoring the treatment group, said Dr. Malhotra, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine and the Kenneth M. Moser Professor in the department of medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. Most patients in the placebo group had worsening of symptoms based on global impression of change – 64.5% vs. 28.2% in the treatment group in the self-reported cohort, and 63.8% vs. 28.7% in the clinician-evaluated cohort.

“The open-label phase demonstrated maintenance-of-efficacy after 1 year,” Dr. Malhotra said. “The safety profile was consistent with prior placebo-controlled studies of solriamfetol. Epworth sleepiness score and adverse event data demonstrated a lack of rebound sleepiness or withdrawal after abrupt discontinuation of solriamfetol during the randomized washout phase. So the bottom line is it looks to be a durable, effective treatment without major side effects.”

Helene A. Emsellem, MD, led a study into how solriamfetol can impact daily activity in patients with narcolepsy. “Solriamfetol at 300 mg reduced activity impairment outside the workplace and, at 150 mg, reduced activity and work impairment from baseline to week 12 on the measures of functionality at work and in private life,” said Dr. Emsellem, of George Washington University Medical Center, Washington. She is medical director of the Center for Sleep & Wake Disorders, Chevy Chase, Md.

Patients on 300 mg solriamfetol (n = 43) gained an average 3.01 on the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire short version (FOSQ-10) total score from baseline to week 12. That compares with gains of 2.57 in the 150-mg group (n = 51), 2.39 in the 75-mg group (n = 49), and 1.56 in the placebo group (n = 52, P = .05). The study looked at activity across four different measures in terms of reduced impairment, as measured by percentage reductions in the negative. The 150-mg group showed most improvement in impairment while working and overall work impairment, with changes of –22.02% and –19.77%, respectively, vs. –11.62% and –10.59% for the 300-mg dose. However, the higher dose showed greater improvement in general activity impairment: –21.17% vs. –17.84% in the 150-mg dose (P less than .05).

Notably, there was little difference across the dosing groups in improvement in work time missed, “I think mostly because there wasn’t much absenteeism to start with,” Dr. Emsellem said.

The 300-mg group also showed greater gains in physical component summary, based on answers to the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, averaging a gain of 3.29 from baseline vs. 2.65 for 150 mg, 2.54 for 75 mg, and 1.06 for placebo. However, on the mental component summary of the survey, the 300-mg group showed the smallest increase: 0.68 vs. 2.05 (150 mg), 1.55 (75 mg), and 0.78 (placebo), respectively (P less than . 05).

In reporting on the effects of solriamfetol through the day, Paula K. Schweitzer, PhD, director of research at the Sleep Medicine and Research Center at St. Luke’s Hospital, Chesterfield, Mo., noted that sustained full-day efficacy may be a limitation of other wake-promoting medications (Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:252-57; Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:761-74). The objective of her study was to evaluate the efficacy of solriamfetol through the day over five sequential MWT trials. Her research involved two double-blind, 12-week studies in patients with either narcolepsy (n = 231) or OSA (n = 459) who were randomized to placebo or one of four doses of solriamfetol: 37.5 mg (in OSA only) and 75, 150, and 300 mg. Patients took the drug orally in the morning.

“Solriamfetol significantly increased sleep latency on all five sequential MWT trials at doses of 150 and 300 mg in the narcolepsy patients, and at doses of 75, 150, and 300 mg in the OSA patients.” Dr. Schweitzer said.

The 150- and 300-mg doses showed the greatest improvement over smaller doses and placebo in both the narcolepsy and OSA groups. In the narcolepsy patients, changes from baseline in MWT sleep latency in the first trial, at approximately 1 hour post dose, were 9.9 (150 mg), 9.9 (300 mg), and –0.6 (placebo) minutes; and in the fifth trial, approximately 9 hours post dose, were 9.3 (150 mg), 12.3 (300 mg), and 3.1 (placebo) minutes. In the OSA patients, changes from baseline in the first trial were 10.9 (150 mg), 12.5 (300 mg), and –0.4 (placebo) minutes; and in the fifth trial, changes were 8.1 (150 mg), 7.6 (300 mg), and 0.2 (placebo) minutes.

“These data demonstrate sustained efficacy over approximately 9 hours following morning dosing for solriamfetol at 150-300 mg in narcolepsy patients and 75-300 mg in OSA patients.” Dr. Schweitzer said.

She also noted that rates of insomnia through the day were less than 5% in each study population combined across dose groups.

Reporting of adverse events was similar across treatment groups in all four studies. The most common adverse event was headache, ranging from around 10% for OSA to 24.2% in patients with cataplexic narcolepsy (n = 91), followed by nausea, decreased appetite, anxiety, and nasopharyngitis. Dr. Malhotra’s study, which involved the largest population of OSA (n = 417) and narcolepsy (n = 226) patients, showed overall rates of at least one adverse event of 75.1% and 74.8%, respectively. His study also showed an overall rate of 5% for respiratory tract infection, and nine patients (1.4%) who had serious cardiovascular adverse events – two cases of atrial fibrillation, and one each of acute MI, angina pectoris, chest discomfort, chest pain, noncardiac chest pain, cerebrovascular accident, and pulmonary embolism.

Dr. Schweitzer noted that the adverse events were mild to moderate in severity, with discontinuation rates of 5% to 7% in the treatment group. Dr. Dauvilliers said the safety results were consistent with previous studies.

All four researchers reported receiving grant/research support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, sponsor of the study.

SOURCE: Dauvilliers Y et al. Abstract 0619; Malhotra A et al. Abstract 0620; Emsellem H et al. Abstract 0621; Schweitzer PK et al. Abstract 0622. Presented at Sleep 2018.

BALTIMORE – Multiple studies based on phase 3 clinical trials of the investigational drug solriamfetol have found that it may be effective for improving next-day wakefulness and work productivity in people with narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea, and that the drug can maintain its effect throughout the day as well as for up to 6 months, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Solriamfetol, developed by Jazz Pharmaceuticals, is the subject of a new drug application accepted by the Food and Drug Administration in March of 2018 for the treatment of excessive sleepiness due to narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Solriamfetol is a selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

The drug was the subject of four different studies presented at SLEEP 2018 that drilled down into its effect on specific aspects of narcolepsy or OSA, or both. One study explored results in narcoleptic patients with and without cataplexy. Another study investigated the drug’s maintenance of efficacy after 6 months of treatment. A third study looked at the drug’s impact on next-day function, work productivity, and quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. And the fourth study researched how solriamfetol helped maintain wakefulness throughout the day.

Yves Dauvilliers, MD, reported that the 150- and 300-mg doses of solriamfetol were effective in improving both sleep latency, as measured with maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores in both cataplexic (n = 117) and noncataplexic (n = 114) narcolepsy. The objective of the study was to reevaluate the safety of solriamfetol in these narcoleptic subgroups from the phase 3 trial, said Dr. Dauvilliers, a faculty member at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montpellier (France).

In patients with cataplexy, the 150-mg dose increased sleep latency from a baseline of 0 to 7.9 after a week and sustained that for 12 weeks; doubling the dose raised that to 10.3 after a week, reaching 10.7 in week 12. Gains were even more dramatic in noncataplexic patients, with the 150-mg dose improving sleep latency to 12.8 at week 1 and 11.6 at week 12, and the 300-mg dose resulting in a gain of 16.8 after a week, trailing off to 13.8 after 12 weeks, Dr. Dauvilliers said.

The study also evaluated ESS scores for three dosing levels – 75, 150, and 300 mg – plus placebo. In the group with cataplexy, ESS at week 12 improved from a baseline of 0 to –3.1, –5.6, and –6.3 for the three dosing groups, respectively, vs. –1.8 for placebo. In the noncataplexy patients with narcolepsy, the improvements in ESS at week 12 were –4.5, –5.2 and –6.4, respectively, vs. –1.5 for placebo.

“At 150 mg and 300 mg, solriamfetol seems to be very effective in treating excessive sleepiness with narcolepsy, with the same efficacy in the group with and without cataplexy – with efficacy even after just 1 week of treatment,” Dr. Dauvilliers said.

Atul Malhotra, MD, and his coresearchers investigated the long-term safety and efficacy of solriamfetol out to 42 weeks in patients with narcolepsy or OSA who completed previous clinical trials, which were 6- and 12-week trials. The study involved an open-label phase from weeks 14 to 27, a 2-week randomized withdrawal phase and then safety follow-up after week 40. In the open-label phase, ESS scores for the overall treatment group (n = 519) improved from 15.9 at baseline to 8.3 at week 40, with variation between the OSA (n = 333) and narcolepsy (n = 186) groups: from 15.2 at baseline to 6.5 at week 40 for the former and from 17.3 to 11.4 for the latter.

In the randomized withdrawal phase, ESS scores for those on solriamfetol (n = 139) migrated upward from 7.3 to 8.5 – but for the placebo group (n = 141) ESS rose from 7.8 to 12.6, a difference of 3.7 favoring the treatment group, said Dr. Malhotra, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine and the Kenneth M. Moser Professor in the department of medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. Most patients in the placebo group had worsening of symptoms based on global impression of change – 64.5% vs. 28.2% in the treatment group in the self-reported cohort, and 63.8% vs. 28.7% in the clinician-evaluated cohort.

“The open-label phase demonstrated maintenance-of-efficacy after 1 year,” Dr. Malhotra said. “The safety profile was consistent with prior placebo-controlled studies of solriamfetol. Epworth sleepiness score and adverse event data demonstrated a lack of rebound sleepiness or withdrawal after abrupt discontinuation of solriamfetol during the randomized washout phase. So the bottom line is it looks to be a durable, effective treatment without major side effects.”

Helene A. Emsellem, MD, led a study into how solriamfetol can impact daily activity in patients with narcolepsy. “Solriamfetol at 300 mg reduced activity impairment outside the workplace and, at 150 mg, reduced activity and work impairment from baseline to week 12 on the measures of functionality at work and in private life,” said Dr. Emsellem, of George Washington University Medical Center, Washington. She is medical director of the Center for Sleep & Wake Disorders, Chevy Chase, Md.

Patients on 300 mg solriamfetol (n = 43) gained an average 3.01 on the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire short version (FOSQ-10) total score from baseline to week 12. That compares with gains of 2.57 in the 150-mg group (n = 51), 2.39 in the 75-mg group (n = 49), and 1.56 in the placebo group (n = 52, P = .05). The study looked at activity across four different measures in terms of reduced impairment, as measured by percentage reductions in the negative. The 150-mg group showed most improvement in impairment while working and overall work impairment, with changes of –22.02% and –19.77%, respectively, vs. –11.62% and –10.59% for the 300-mg dose. However, the higher dose showed greater improvement in general activity impairment: –21.17% vs. –17.84% in the 150-mg dose (P less than .05).

Notably, there was little difference across the dosing groups in improvement in work time missed, “I think mostly because there wasn’t much absenteeism to start with,” Dr. Emsellem said.