User login

Deep Soft Tissue Mass of the Knee

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

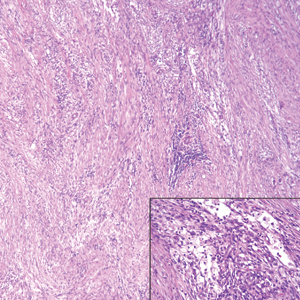

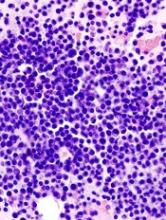

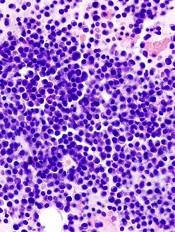

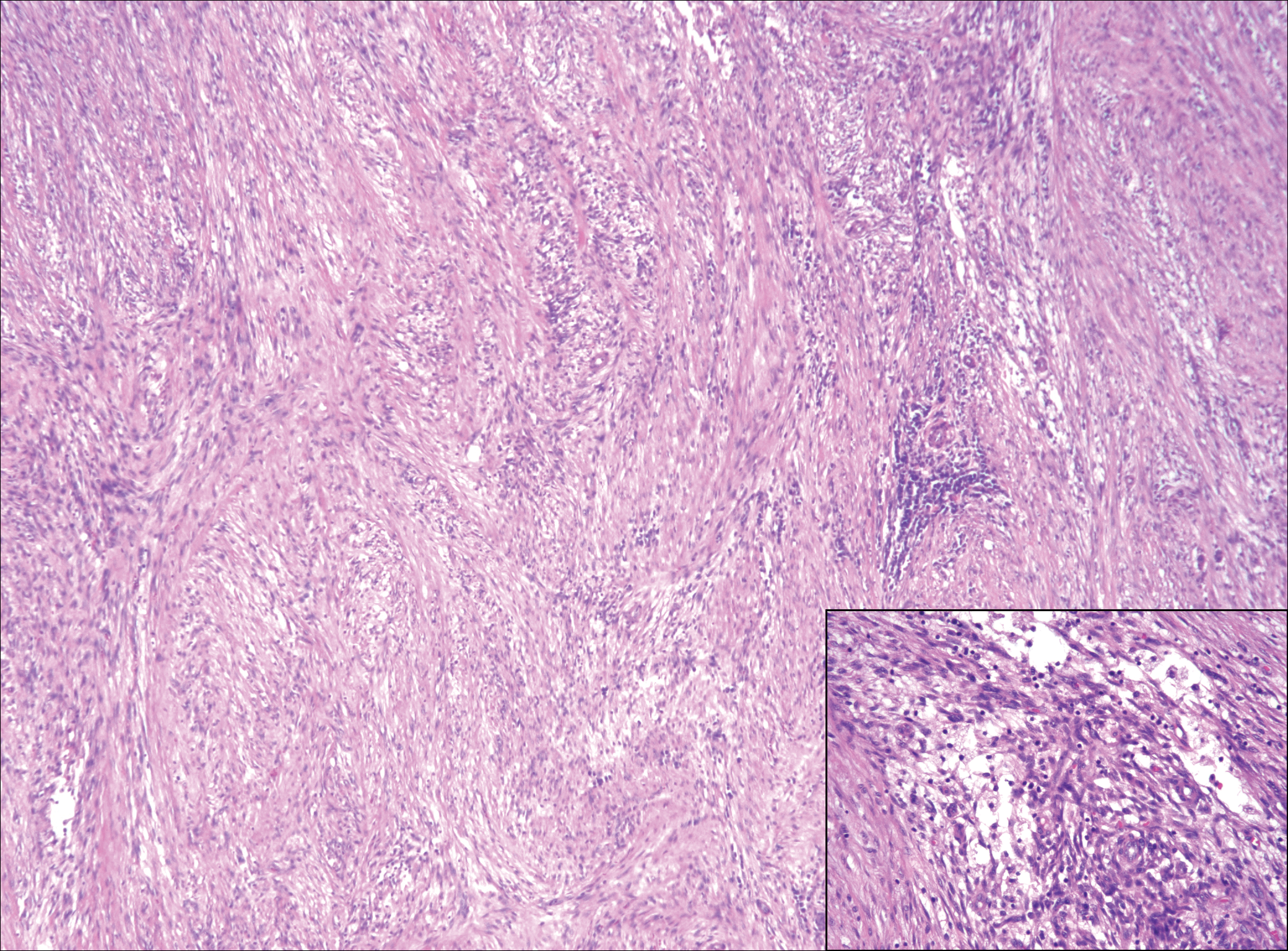

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

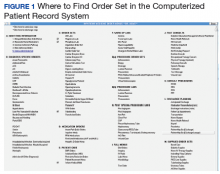

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

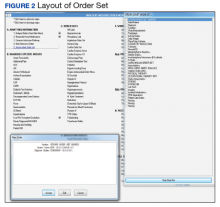

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

A 16-year-old adolescent girl presented with a bump over the left posterior knee of 1 month's duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She denied recent trauma or injury to the area. On physical examination there was a visible and palpable tense nontender mass the size of an egg over the left posterior knee. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a lobulated mass-like focus of T2 hyperintensity centered at the subcutaneous tissues and superficial myofascial plane of the gastrocnemius on the posterior knee. Complete excision of the lesion was performed and demonstrated a 2.6.2 ×2.9.2 ×2.1-cm mass within subcutaneous adipose tissue. There was no microscopic involvement of skeletal muscle. Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor was performed that was positive for smooth muscle actin and negative for desmin, S-100, CD34, pan-cytokeratin, and β-catenin. Fluorescent in situ hybridization testing demonstrated rearrangement of the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6 gene, USP6, locus (17p13).

Submit Comments on VTE Guidelines by July 25

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) seeks comments by July 25 on draft clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism: VTE Prevention in Surgical Hospitalized Patients.

The draft recommendations and a link to the online survey where comments are collected are available here.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) seeks comments by July 25 on draft clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism: VTE Prevention in Surgical Hospitalized Patients.

The draft recommendations and a link to the online survey where comments are collected are available here.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) seeks comments by July 25 on draft clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism: VTE Prevention in Surgical Hospitalized Patients.

The draft recommendations and a link to the online survey where comments are collected are available here.

New and Noteworthy Information—July 2018

Adequate Sleep Associated With Lower Dementia Risk

Short and long daily sleep duration are risk factors for dementia and death in adults age 60 and older, according to a study published online ahead of print June 6 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,517 adults without dementia for 10 years. Self-reported daily sleep durations were grouped into five categories. The association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and death was determined using Cox proportional hazards models. During follow-up, 294 participants developed dementia, and 282 died. Age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates of dementia and all-cause mortality were significantly greater in subjects who slept less than 5.0 hours/day or 10.0 or more hours/day than in people who slept from 5.0 to 6.9 hours/day.

Ohara T, Honda T, Hata J, et al. Association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and mortality in a Japanese community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jun 6 [Epub ahead of print].

Rivaroxaban Not Superior to Aspirin for Stroke Prevention

Rivaroxaban is not superior to aspirin in the prevention of recurrent stroke, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers compared the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban at a daily dose of 15 mg with aspirin at a daily dose of 100 mg for the prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with recent ischemic stroke that was presumed to be from cerebral embolism. The primary outcome was the first recurrence of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or systemic embolism in a time-to-event analysis. At 459 sites, 3,609 patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban, and 3,604 were randomized to aspirin. Recurrent ischemic stroke occurred in 172 patients in the rivaroxaban group and in 160 in the aspirin group.

Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H, et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-2201.

Disintegrating Brain Lesions May Indicate Worsening MS

Atrophied lesion volume may indicate increasing disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print June 1 in the Journal of Neuroimaging. A total of 192 patients with clinically isolated syndrome or MS received 3T MRI at baseline and at five years. Investigators quantified lesions at baseline and calculated new and enlarging lesion volumes during the study interval. Atrophied lesion volume was calculated by combining baseline lesion masks with follow-up SIENAX-derived CSF partial volume maps. The researchers evaluated correlations between these measures and disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Atrophied lesion volume was different between MS subtypes and exceeded new lesion volume accumulation in progressive MS. Atrophied lesion volume was the only significant correlate of EDSS change.

Dwyer MG, Bergsland N, Ramasamy DP, et al. Atrophied brain lesion volume: a new imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2018 Jun 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Do Migraineurs Seek Behavioral Treatment After a Referral?

A significant number of migraineurs are not using effective behavioral treatments for migraine, according to a study published online ahead of print June 5 in Pain Medicine. In a prospective cohort study, researchers tracked 234 patients with migraine who presented to an academic headache center and referred 69 of them for behavioral treatment with an appropriately trained therapist. Fifty-three of the referred patients completed a follow-up interview within three months of their initial appointment and were included in the analysis. Of the patients referred for behavioral treatment, 30 made an appointment. Investigators found no differences between people who started behavioral therapy and people who did not. Study authors did find that people who had previously seen a psychologist for migraine were more likely to initiate therapy.

Minen MT, Azarchi S, Sobolev R, et al. Factors related to migraine patients’ decisions to initiate behavioral migraine treatment following a headache specialist’s recommendation: a prospective observational study. Pain Med. 2018 Jun 5 [Epub ahead of print].

TIA Associated With Increased Five-Year Risk of Stroke

People with transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at risk for a cardiovascular event in the following five years, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers evaluated patients who had had a TIA within seven days before enrollment in a registry of TIA clinics. Of 61 sites, 42 had follow-up data on more than 50% of their enrolled patients at five years. The study’s primary outcome was a composite of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or death from cardiovascular causes, with an emphasis on events that occurred in the second through fifth years. At five years, stroke had occurred in 345 of the 3,847 patients included in the follow-up study, and 149 of them had a stroke during the second through fifth years of follow-up.

Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2182-2190.

Follow-Up Care for TBI Is Not Delivered Adequately

Follow-up care for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) is not delivered optimally, according to a study published May 25 in JAMA Network Open. In a cohort study, researchers surveyed 831 participants in the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI initiative about their care after hospital discharge. Follow-up care was defined as providing TBI-related educational materials at discharge, calling patients within two weeks after release, seeing a healthcare provider within two weeks, and seeing a healthcare provider within three months. Approximately 42% of participants reported receiving TBI-related educational material at discharge, and 44% reported seeing a physician or other medical practitioner within three months after injury. Of patients with a positive finding on CT, 39% had not seen a medical practitioner at three months after injury.

Seabury SA, Gaudette E, Goldman DP, et al. Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(1):e180210.

Researchers Examine Mortality Rate of Pediatric Stroke

In-hospital mortality occurs in 2.6% of children with arterial ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the May issue of Pediatrics. The retrospective study included 915 infants younger than 1 month and 2,273 children age 1 month to 18 years with stroke at 87 hospitals in 24 countries. Death during hospitalization and cause of death were ascertained from medical records. A total of 14 neonates and 70 children died during hospitalization. Of 48 cases with reported causes of death, 31 were stroke-related. Remaining deaths were attributed to medical disease. In multivariable analysis, congenital heart disease, posterior plus anterior circulation stroke, and stroke presentation without seizures were associated with in-hospital mortality for neonates. Hispanic ethnicity, congenital heart disease, and posterior plus anterior circulation stroke were associated with in-hospital mortality for children.

Beslow LA, Dowling MM, Hassanein SMA, et al. Mortality after pediatric arterial ischemic stroke. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5).

FDA Approves zEEG Dry Electrode Headset

The FDA has approved the zEEG dry electrode EEG headset for clinical use. The zEEG headset is backed by a cloud platform that allows users to upload data instantly, provides tools for analysis, and enables remote interpretation by neurologists. A clinical study found that the zEEG headset provided EEG signal quality that was comparable to that of an approved, traditional EEG system. In two study cohorts, a total of 30 patients were studied for time periods of as long as two hours, and the zEEG device performed at least as well as the reference device, based on predefined acceptance criteria. Study results will be published in the coming months. Zeto, headquartered in Santa Clara, California, markets the device.

South Asian Americans Have High Cardiovascular Mortality

South Asians living in the United States have higher mortality from heart conditions caused by atherosclerosis, such as heart attack and stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print May 24 in Circulation. Investigators reviewed the literature relevant to South Asian populations’ demographics and risk factors, health behaviors, and interventions, including physical activity, diet, medications, and community strategies. South Asians have higher proportional mortality rates from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, compared with other Asian groups, largely because of the lower risk observed in East Asian populations. A majority of the risk in South Asians can be explained by the increased prevalence of known risk factors, especially factors related to insulin resistance. The authors found no unique risk factors in this population.

Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 May 24 [Epub ahead of print].

How Much Exercise Improves Cognition in Older Adults?

Exercising for at least 52 hours over six months is associated with improved cognitive performance in older adults with and without cognitive impairment, according to a study published online ahead of print May 30 in Neurology. Researchers reviewed data for 98 randomized, controlled exercise trials including 11,061 participants with an average age of 73. About 59% of the participants were healthy adults, 26% had mild cognitive impairment, and 15% had dementia. Researchers collected data on exercise session length, intensity, weekly frequency, and amount of exercise over time. Aerobic exercise was the most common form of exercise. In healthy people and people with cognitive impairment, longer term exposure to exercise, at least 52 hours conducted over an average of about six months, improved the brain’s processing speed.

Gomes-Osman J, Cabral DF, Morris TP, et al. Exercise for cognitive brain health in aging. Neurology. 2018 May 30 [Epub ahead of print].

Blood Biomarkers Detect Subconcussive Head Trauma

Blood biomarkers can detect the neurologic injury associated with repetitive subconcussive head trauma, according to a study published online ahead of print May 29 in the Journal of Neurosurgery. A total of 35 National Collegiate Athletic Association football players underwent blood sampling throughout the 2016 football season. Samples were analyzed for plasma concentrations of tau and serum concentrations of neurofilament light. Athletes were categorized as starters or nonstarters, and the investigators assessed between-group differences and time-course differences. In nonstarters, plasma concentrations of tau decreased over the season. Starters had lower plasma concentrations of tau. Plasma concentrations of tau could not be used to distinguish between starters and nonstarters. Serum concentrations of neurofilament light increased as head impacts increased, specifically in starters. Serum neurofilament light distinguished starters from nonstarters.

Oliver JM, Anzalone AJ, Stone JD, et al. Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. 2018 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Model Estimates Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia

Most people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease will not develop dementia during their lifetimes, according to a study published online ahead of print May 7 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers used a multistate model for Alzheimer’s disease along with US death rates to estimate lifetime and 10-year risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia vary by age, gender, and preclinical or clinical disease state. A 70-year-old male with amyloid but no signs of neurodegeneration and no memory loss has a lifetime risk of 19.9%. The lifetime risks for a female with amyloidosis are 8.4% at age 90 and 29.3% at age 65. People younger than 85 with mild cognitive impairment, amyloidosis, and neurodegeneration have lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia greater than 50%.

Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N. Estimation of lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia using biomarkers for preclinical disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

Depression Is Associated With Brain and Memory Outcomes

In a sample of mostly Caribbean Hispanic, stroke-free older adults, greater depressive symptoms were associated with worse episodic memory, smaller cerebral volume, and silent infarcts, according to a study published online ahead of print May 9 in Neurology. Researchers analyzed data from the Northern Manhattan Study. A total of 1,111 participants underwent baseline evaluations of depressive symptoms, MRI markers, and cognitive function. At baseline, 22% of participants had greater depressive symptoms. Greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with worse baseline episodic memory in models adjusted for sociodemographics, vascular risk factors, behavioral factors, and antidepressant medications. Furthermore, greater depressive symptoms were associated with smaller cerebral parenchymal fraction and increased odds of subclinical brain infarcts, after adjustment for sociodemographics, behavioral factors, and vascular risk factors.

Al Hazzouri AZ, Caunca MR, Nobrega JC. Greater depressive symptoms, cognition, and markers of brain aging. Neurology. 2018 May 9 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

Adequate Sleep Associated With Lower Dementia Risk

Short and long daily sleep duration are risk factors for dementia and death in adults age 60 and older, according to a study published online ahead of print June 6 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,517 adults without dementia for 10 years. Self-reported daily sleep durations were grouped into five categories. The association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and death was determined using Cox proportional hazards models. During follow-up, 294 participants developed dementia, and 282 died. Age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates of dementia and all-cause mortality were significantly greater in subjects who slept less than 5.0 hours/day or 10.0 or more hours/day than in people who slept from 5.0 to 6.9 hours/day.

Ohara T, Honda T, Hata J, et al. Association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and mortality in a Japanese community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jun 6 [Epub ahead of print].

Rivaroxaban Not Superior to Aspirin for Stroke Prevention

Rivaroxaban is not superior to aspirin in the prevention of recurrent stroke, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers compared the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban at a daily dose of 15 mg with aspirin at a daily dose of 100 mg for the prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with recent ischemic stroke that was presumed to be from cerebral embolism. The primary outcome was the first recurrence of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or systemic embolism in a time-to-event analysis. At 459 sites, 3,609 patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban, and 3,604 were randomized to aspirin. Recurrent ischemic stroke occurred in 172 patients in the rivaroxaban group and in 160 in the aspirin group.

Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H, et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-2201.

Disintegrating Brain Lesions May Indicate Worsening MS

Atrophied lesion volume may indicate increasing disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print June 1 in the Journal of Neuroimaging. A total of 192 patients with clinically isolated syndrome or MS received 3T MRI at baseline and at five years. Investigators quantified lesions at baseline and calculated new and enlarging lesion volumes during the study interval. Atrophied lesion volume was calculated by combining baseline lesion masks with follow-up SIENAX-derived CSF partial volume maps. The researchers evaluated correlations between these measures and disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Atrophied lesion volume was different between MS subtypes and exceeded new lesion volume accumulation in progressive MS. Atrophied lesion volume was the only significant correlate of EDSS change.

Dwyer MG, Bergsland N, Ramasamy DP, et al. Atrophied brain lesion volume: a new imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2018 Jun 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Do Migraineurs Seek Behavioral Treatment After a Referral?

A significant number of migraineurs are not using effective behavioral treatments for migraine, according to a study published online ahead of print June 5 in Pain Medicine. In a prospective cohort study, researchers tracked 234 patients with migraine who presented to an academic headache center and referred 69 of them for behavioral treatment with an appropriately trained therapist. Fifty-three of the referred patients completed a follow-up interview within three months of their initial appointment and were included in the analysis. Of the patients referred for behavioral treatment, 30 made an appointment. Investigators found no differences between people who started behavioral therapy and people who did not. Study authors did find that people who had previously seen a psychologist for migraine were more likely to initiate therapy.

Minen MT, Azarchi S, Sobolev R, et al. Factors related to migraine patients’ decisions to initiate behavioral migraine treatment following a headache specialist’s recommendation: a prospective observational study. Pain Med. 2018 Jun 5 [Epub ahead of print].

TIA Associated With Increased Five-Year Risk of Stroke

People with transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at risk for a cardiovascular event in the following five years, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers evaluated patients who had had a TIA within seven days before enrollment in a registry of TIA clinics. Of 61 sites, 42 had follow-up data on more than 50% of their enrolled patients at five years. The study’s primary outcome was a composite of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or death from cardiovascular causes, with an emphasis on events that occurred in the second through fifth years. At five years, stroke had occurred in 345 of the 3,847 patients included in the follow-up study, and 149 of them had a stroke during the second through fifth years of follow-up.

Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2182-2190.

Follow-Up Care for TBI Is Not Delivered Adequately

Follow-up care for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) is not delivered optimally, according to a study published May 25 in JAMA Network Open. In a cohort study, researchers surveyed 831 participants in the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI initiative about their care after hospital discharge. Follow-up care was defined as providing TBI-related educational materials at discharge, calling patients within two weeks after release, seeing a healthcare provider within two weeks, and seeing a healthcare provider within three months. Approximately 42% of participants reported receiving TBI-related educational material at discharge, and 44% reported seeing a physician or other medical practitioner within three months after injury. Of patients with a positive finding on CT, 39% had not seen a medical practitioner at three months after injury.

Seabury SA, Gaudette E, Goldman DP, et al. Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(1):e180210.

Researchers Examine Mortality Rate of Pediatric Stroke

In-hospital mortality occurs in 2.6% of children with arterial ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the May issue of Pediatrics. The retrospective study included 915 infants younger than 1 month and 2,273 children age 1 month to 18 years with stroke at 87 hospitals in 24 countries. Death during hospitalization and cause of death were ascertained from medical records. A total of 14 neonates and 70 children died during hospitalization. Of 48 cases with reported causes of death, 31 were stroke-related. Remaining deaths were attributed to medical disease. In multivariable analysis, congenital heart disease, posterior plus anterior circulation stroke, and stroke presentation without seizures were associated with in-hospital mortality for neonates. Hispanic ethnicity, congenital heart disease, and posterior plus anterior circulation stroke were associated with in-hospital mortality for children.

Beslow LA, Dowling MM, Hassanein SMA, et al. Mortality after pediatric arterial ischemic stroke. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5).

FDA Approves zEEG Dry Electrode Headset

The FDA has approved the zEEG dry electrode EEG headset for clinical use. The zEEG headset is backed by a cloud platform that allows users to upload data instantly, provides tools for analysis, and enables remote interpretation by neurologists. A clinical study found that the zEEG headset provided EEG signal quality that was comparable to that of an approved, traditional EEG system. In two study cohorts, a total of 30 patients were studied for time periods of as long as two hours, and the zEEG device performed at least as well as the reference device, based on predefined acceptance criteria. Study results will be published in the coming months. Zeto, headquartered in Santa Clara, California, markets the device.

South Asian Americans Have High Cardiovascular Mortality

South Asians living in the United States have higher mortality from heart conditions caused by atherosclerosis, such as heart attack and stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print May 24 in Circulation. Investigators reviewed the literature relevant to South Asian populations’ demographics and risk factors, health behaviors, and interventions, including physical activity, diet, medications, and community strategies. South Asians have higher proportional mortality rates from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, compared with other Asian groups, largely because of the lower risk observed in East Asian populations. A majority of the risk in South Asians can be explained by the increased prevalence of known risk factors, especially factors related to insulin resistance. The authors found no unique risk factors in this population.

Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 May 24 [Epub ahead of print].

How Much Exercise Improves Cognition in Older Adults?

Exercising for at least 52 hours over six months is associated with improved cognitive performance in older adults with and without cognitive impairment, according to a study published online ahead of print May 30 in Neurology. Researchers reviewed data for 98 randomized, controlled exercise trials including 11,061 participants with an average age of 73. About 59% of the participants were healthy adults, 26% had mild cognitive impairment, and 15% had dementia. Researchers collected data on exercise session length, intensity, weekly frequency, and amount of exercise over time. Aerobic exercise was the most common form of exercise. In healthy people and people with cognitive impairment, longer term exposure to exercise, at least 52 hours conducted over an average of about six months, improved the brain’s processing speed.

Gomes-Osman J, Cabral DF, Morris TP, et al. Exercise for cognitive brain health in aging. Neurology. 2018 May 30 [Epub ahead of print].

Blood Biomarkers Detect Subconcussive Head Trauma

Blood biomarkers can detect the neurologic injury associated with repetitive subconcussive head trauma, according to a study published online ahead of print May 29 in the Journal of Neurosurgery. A total of 35 National Collegiate Athletic Association football players underwent blood sampling throughout the 2016 football season. Samples were analyzed for plasma concentrations of tau and serum concentrations of neurofilament light. Athletes were categorized as starters or nonstarters, and the investigators assessed between-group differences and time-course differences. In nonstarters, plasma concentrations of tau decreased over the season. Starters had lower plasma concentrations of tau. Plasma concentrations of tau could not be used to distinguish between starters and nonstarters. Serum concentrations of neurofilament light increased as head impacts increased, specifically in starters. Serum neurofilament light distinguished starters from nonstarters.

Oliver JM, Anzalone AJ, Stone JD, et al. Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. 2018 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Model Estimates Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia

Most people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease will not develop dementia during their lifetimes, according to a study published online ahead of print May 7 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers used a multistate model for Alzheimer’s disease along with US death rates to estimate lifetime and 10-year risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia vary by age, gender, and preclinical or clinical disease state. A 70-year-old male with amyloid but no signs of neurodegeneration and no memory loss has a lifetime risk of 19.9%. The lifetime risks for a female with amyloidosis are 8.4% at age 90 and 29.3% at age 65. People younger than 85 with mild cognitive impairment, amyloidosis, and neurodegeneration have lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia greater than 50%.

Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N. Estimation of lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia using biomarkers for preclinical disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

Depression Is Associated With Brain and Memory Outcomes

In a sample of mostly Caribbean Hispanic, stroke-free older adults, greater depressive symptoms were associated with worse episodic memory, smaller cerebral volume, and silent infarcts, according to a study published online ahead of print May 9 in Neurology. Researchers analyzed data from the Northern Manhattan Study. A total of 1,111 participants underwent baseline evaluations of depressive symptoms, MRI markers, and cognitive function. At baseline, 22% of participants had greater depressive symptoms. Greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with worse baseline episodic memory in models adjusted for sociodemographics, vascular risk factors, behavioral factors, and antidepressant medications. Furthermore, greater depressive symptoms were associated with smaller cerebral parenchymal fraction and increased odds of subclinical brain infarcts, after adjustment for sociodemographics, behavioral factors, and vascular risk factors.

Al Hazzouri AZ, Caunca MR, Nobrega JC. Greater depressive symptoms, cognition, and markers of brain aging. Neurology. 2018 May 9 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

Adequate Sleep Associated With Lower Dementia Risk

Short and long daily sleep duration are risk factors for dementia and death in adults age 60 and older, according to a study published online ahead of print June 6 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. In a prospective cohort study, researchers followed 1,517 adults without dementia for 10 years. Self-reported daily sleep durations were grouped into five categories. The association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and death was determined using Cox proportional hazards models. During follow-up, 294 participants developed dementia, and 282 died. Age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates of dementia and all-cause mortality were significantly greater in subjects who slept less than 5.0 hours/day or 10.0 or more hours/day than in people who slept from 5.0 to 6.9 hours/day.

Ohara T, Honda T, Hata J, et al. Association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and mortality in a Japanese community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jun 6 [Epub ahead of print].

Rivaroxaban Not Superior to Aspirin for Stroke Prevention

Rivaroxaban is not superior to aspirin in the prevention of recurrent stroke, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers compared the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban at a daily dose of 15 mg with aspirin at a daily dose of 100 mg for the prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with recent ischemic stroke that was presumed to be from cerebral embolism. The primary outcome was the first recurrence of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or systemic embolism in a time-to-event analysis. At 459 sites, 3,609 patients were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban, and 3,604 were randomized to aspirin. Recurrent ischemic stroke occurred in 172 patients in the rivaroxaban group and in 160 in the aspirin group.

Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H, et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-2201.

Disintegrating Brain Lesions May Indicate Worsening MS

Atrophied lesion volume may indicate increasing disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print June 1 in the Journal of Neuroimaging. A total of 192 patients with clinically isolated syndrome or MS received 3T MRI at baseline and at five years. Investigators quantified lesions at baseline and calculated new and enlarging lesion volumes during the study interval. Atrophied lesion volume was calculated by combining baseline lesion masks with follow-up SIENAX-derived CSF partial volume maps. The researchers evaluated correlations between these measures and disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Atrophied lesion volume was different between MS subtypes and exceeded new lesion volume accumulation in progressive MS. Atrophied lesion volume was the only significant correlate of EDSS change.

Dwyer MG, Bergsland N, Ramasamy DP, et al. Atrophied brain lesion volume: a new imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2018 Jun 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Do Migraineurs Seek Behavioral Treatment After a Referral?

A significant number of migraineurs are not using effective behavioral treatments for migraine, according to a study published online ahead of print June 5 in Pain Medicine. In a prospective cohort study, researchers tracked 234 patients with migraine who presented to an academic headache center and referred 69 of them for behavioral treatment with an appropriately trained therapist. Fifty-three of the referred patients completed a follow-up interview within three months of their initial appointment and were included in the analysis. Of the patients referred for behavioral treatment, 30 made an appointment. Investigators found no differences between people who started behavioral therapy and people who did not. Study authors did find that people who had previously seen a psychologist for migraine were more likely to initiate therapy.

Minen MT, Azarchi S, Sobolev R, et al. Factors related to migraine patients’ decisions to initiate behavioral migraine treatment following a headache specialist’s recommendation: a prospective observational study. Pain Med. 2018 Jun 5 [Epub ahead of print].

TIA Associated With Increased Five-Year Risk of Stroke

People with transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at risk for a cardiovascular event in the following five years, according to a study published June 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers evaluated patients who had had a TIA within seven days before enrollment in a registry of TIA clinics. Of 61 sites, 42 had follow-up data on more than 50% of their enrolled patients at five years. The study’s primary outcome was a composite of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or death from cardiovascular causes, with an emphasis on events that occurred in the second through fifth years. At five years, stroke had occurred in 345 of the 3,847 patients included in the follow-up study, and 149 of them had a stroke during the second through fifth years of follow-up.

Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2182-2190.

Follow-Up Care for TBI Is Not Delivered Adequately

Follow-up care for patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) is not delivered optimally, according to a study published May 25 in JAMA Network Open. In a cohort study, researchers surveyed 831 participants in the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI initiative about their care after hospital discharge. Follow-up care was defined as providing TBI-related educational materials at discharge, calling patients within two weeks after release, seeing a healthcare provider within two weeks, and seeing a healthcare provider within three months. Approximately 42% of participants reported receiving TBI-related educational material at discharge, and 44% reported seeing a physician or other medical practitioner within three months after injury. Of patients with a positive finding on CT, 39% had not seen a medical practitioner at three months after injury.

Seabury SA, Gaudette E, Goldman DP, et al. Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(1):e180210.

Researchers Examine Mortality Rate of Pediatric Stroke

In-hospital mortality occurs in 2.6% of children with arterial ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the May issue of Pediatrics. The retrospective study included 915 infants younger than 1 month and 2,273 children age 1 month to 18 years with stroke at 87 hospitals in 24 countries. Death during hospitalization and cause of death were ascertained from medical records. A total of 14 neonates and 70 children died during hospitalization. Of 48 cases with reported causes of death, 31 were stroke-related. Remaining deaths were attributed to medical disease. In multivariable analysis, congenital heart disease, posterior plus anterior circulation stroke, and stroke presentation without seizures were associated with in-hospital mortality for neonates. Hispanic ethnicity, congenital heart disease, and posterior plus anterior circulation stroke were associated with in-hospital mortality for children.

Beslow LA, Dowling MM, Hassanein SMA, et al. Mortality after pediatric arterial ischemic stroke. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5).

FDA Approves zEEG Dry Electrode Headset

The FDA has approved the zEEG dry electrode EEG headset for clinical use. The zEEG headset is backed by a cloud platform that allows users to upload data instantly, provides tools for analysis, and enables remote interpretation by neurologists. A clinical study found that the zEEG headset provided EEG signal quality that was comparable to that of an approved, traditional EEG system. In two study cohorts, a total of 30 patients were studied for time periods of as long as two hours, and the zEEG device performed at least as well as the reference device, based on predefined acceptance criteria. Study results will be published in the coming months. Zeto, headquartered in Santa Clara, California, markets the device.

South Asian Americans Have High Cardiovascular Mortality

South Asians living in the United States have higher mortality from heart conditions caused by atherosclerosis, such as heart attack and stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print May 24 in Circulation. Investigators reviewed the literature relevant to South Asian populations’ demographics and risk factors, health behaviors, and interventions, including physical activity, diet, medications, and community strategies. South Asians have higher proportional mortality rates from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, compared with other Asian groups, largely because of the lower risk observed in East Asian populations. A majority of the risk in South Asians can be explained by the increased prevalence of known risk factors, especially factors related to insulin resistance. The authors found no unique risk factors in this population.

Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 May 24 [Epub ahead of print].

How Much Exercise Improves Cognition in Older Adults?

Exercising for at least 52 hours over six months is associated with improved cognitive performance in older adults with and without cognitive impairment, according to a study published online ahead of print May 30 in Neurology. Researchers reviewed data for 98 randomized, controlled exercise trials including 11,061 participants with an average age of 73. About 59% of the participants were healthy adults, 26% had mild cognitive impairment, and 15% had dementia. Researchers collected data on exercise session length, intensity, weekly frequency, and amount of exercise over time. Aerobic exercise was the most common form of exercise. In healthy people and people with cognitive impairment, longer term exposure to exercise, at least 52 hours conducted over an average of about six months, improved the brain’s processing speed.

Gomes-Osman J, Cabral DF, Morris TP, et al. Exercise for cognitive brain health in aging. Neurology. 2018 May 30 [Epub ahead of print].

Blood Biomarkers Detect Subconcussive Head Trauma

Blood biomarkers can detect the neurologic injury associated with repetitive subconcussive head trauma, according to a study published online ahead of print May 29 in the Journal of Neurosurgery. A total of 35 National Collegiate Athletic Association football players underwent blood sampling throughout the 2016 football season. Samples were analyzed for plasma concentrations of tau and serum concentrations of neurofilament light. Athletes were categorized as starters or nonstarters, and the investigators assessed between-group differences and time-course differences. In nonstarters, plasma concentrations of tau decreased over the season. Starters had lower plasma concentrations of tau. Plasma concentrations of tau could not be used to distinguish between starters and nonstarters. Serum concentrations of neurofilament light increased as head impacts increased, specifically in starters. Serum neurofilament light distinguished starters from nonstarters.

Oliver JM, Anzalone AJ, Stone JD, et al. Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. 2018 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

Model Estimates Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia

Most people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease will not develop dementia during their lifetimes, according to a study published online ahead of print May 7 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers used a multistate model for Alzheimer’s disease along with US death rates to estimate lifetime and 10-year risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia vary by age, gender, and preclinical or clinical disease state. A 70-year-old male with amyloid but no signs of neurodegeneration and no memory loss has a lifetime risk of 19.9%. The lifetime risks for a female with amyloidosis are 8.4% at age 90 and 29.3% at age 65. People younger than 85 with mild cognitive impairment, amyloidosis, and neurodegeneration have lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia greater than 50%.

Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N. Estimation of lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia using biomarkers for preclinical disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

Depression Is Associated With Brain and Memory Outcomes

In a sample of mostly Caribbean Hispanic, stroke-free older adults, greater depressive symptoms were associated with worse episodic memory, smaller cerebral volume, and silent infarcts, according to a study published online ahead of print May 9 in Neurology. Researchers analyzed data from the Northern Manhattan Study. A total of 1,111 participants underwent baseline evaluations of depressive symptoms, MRI markers, and cognitive function. At baseline, 22% of participants had greater depressive symptoms. Greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with worse baseline episodic memory in models adjusted for sociodemographics, vascular risk factors, behavioral factors, and antidepressant medications. Furthermore, greater depressive symptoms were associated with smaller cerebral parenchymal fraction and increased odds of subclinical brain infarcts, after adjustment for sociodemographics, behavioral factors, and vascular risk factors.

Al Hazzouri AZ, Caunca MR, Nobrega JC. Greater depressive symptoms, cognition, and markers of brain aging. Neurology. 2018 May 9 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

Study spotlights risk factors for albuminuria in youth with T2DM

TORONTO – When Brandy Wicklow, MD, began her pediatric endocrinology fellowship at McGill University in 2006, about 12 per 100,000 children in Manitoba, Canada, were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus each year. By 2016 that rate had more than doubled, to 26 per 100,000 children.

“If you look just at indigenous youth in our province, it’s probably one of the highest rates ever reported, with 95 per 100,000 Manitoba First Nation children diagnosed with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Wicklow, a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of Manitoba and the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba.

Many indigenous populations also face an increased risk for primary renal disease. One study reviewed the charts 90 of Canadian First Nation children and adolescents with T2DM (Diabetes Care. 2009;32[5]:786-90). Of 10 who had renal biopsies performed, nine had immune complex disease/glomerulosclerosis, two had mild diabetes-related lesions, and seven had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS); yet none had classic nephropathy. An analysis of Chinese youth that included 216 renal biopsies yielded similar findings (Intl Urol Nephrol. 2012;45[1]:173-9).

It’s also known that early-onset T2DM is associated with substantially increased incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and mortality in middle age. For example, one study of Pima Indians found that those who were diagnosed with T2DM earlier than 20 years of age had a one in five chance of developing ESRD, while those who were diagnosed at age 20 years or older had a one in two chance of ESRD (JAMA. 2006;296[4]:421-6). In a separate analysis, researchers estimated the remaining lifetime risks for ESRD among Aboriginal people in Australia with and without diabetes (Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103[3]:e24-6). The value for young adults with diabetes was high, about one in two at the age of 30 years, while it decreased with age to one in seven at 60 years.

“One of the first biomarkers we see in terms of renal disease in kids with T2DM is albuminuria,” Dr. Wicklow said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “The question is, why do kids with type 2 get more renal disease than kids with type 1 diabetes?” The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) study from 2006 found that hypertension, increased body mass index, increased weight circumference, and increased lipids were factors, while the SEARCH study from 2015 found that ethnicity, increased weight to height ratio, and mean arterial pressure were factors.

“Insulin resistance is significantly associated with albuminuria,” Dr. Wicklow continued. “It’s also been shown to be associated with hyperfiltration. Some of the markers of insulin resistance are important but they make up about 19% of the variance between type 1 and type 2, which means there are other variables that we’re not measuring.”

Enter ICARE (Improving Renal Complications in Adolescents with Type 2 Diabetes through Research), an ongoing prospective cohort study that Dr. Wicklow and her associates launched in 2014 at eight centers in Canada. It aims to examine the biopsychosocial risk factors for albuminuria in youth with T2DM and the mechanisms for renal injury. “Our theoretical framework was that biological exposures that we are aware of, such as glycemic control, hypertension, and lipids, would all be important in the development of albuminuria and renal disease in kids,” said Dr. Wicklow, who is the study’s coprimary investigator along with Allison Dart, MD. “But what we thought was novel was that psychological exposures either as socioeconomic status or as mental health factors would also directly impinge on renal health with respect to chronic inflammation in the body, inflammation in the kidneys, and long-term kidney damage.”

The first phase of ICARE involved a detailed phenotypic assessment of youth, including anthropometrics, biochemistry, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, overnight urine collections for albumin excretion, renal ultrasound, and iohexol-derived glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Phase 2 included an evaluation of psychological factors, including hair-derived cortisol; validated questionnaires for perceived stress, distress, and resiliency; and a detailed evaluation of systemic and urine inflammatory biomarkers. Annual follow-up is carried out to assess temporal associations between clinical risk factors and renal outcomes, including progression of albuminuria.

At the meeting, Dr. Wicklow reported on 187 youth enrolled to date. Of these, 96% were of indigenous ethnicity, 57 had albuminuria and 130 did not, and the mean ages of the groups were 16 years and 15 years, respectively. At baseline, a higher proportion of those in the albuminuria group were female (74% vs. 64% of those in the no albuminuria group, respectively), had a higher mean hemoglobin A1c (11% vs. 9%), and had hypertension (94% vs. 72%). She noted that upon presentation to the clinic, only 23% of participants had HbA1c levels less than 7%, only 26% had ranges between 7% and 9%, and about 40% did not have any hypertension. Of those who did, 27% had nighttime-only hypertension, and only 2% had daytime-only hypertension.

“The other risk factor these kids have for developing ESRD is that the majority were exposed to diabetes in pregnancy,” Dr. Wicklow said. “Murine models of maternal diabetes exposure have demonstrated that offspring have small kidneys, less ureteric bud branching, and a lower number of nephrons. Most of the human clinical cohort studies look at associations between development of diabetes and parental hypertension, maternal smoking, and maternal education. There is likely an impact at birth that sets these kids up for development of type 2 diabetes.”

In addition, results from clinical cohort studies have found that depression, mental stress, and distress are high in youth with T2DM. “Preliminary data suggest that if you have positive mental health, or coping strategies, or someone has worked through this with you and you are resilient, you might benefit in terms of overall glycemic control,” she said. For example, ICARE investigators have found that the higher the score on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), the greater the risk of renal inflammation as measured by monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1; P = .02). “Mental health seems to be something that can directly impact your health from a biological standpoint, and we might be able to find biomarkers of that risk,” Dr. Wicklow said. “Where does the stress come from? Most of my patients are indigenous, so it’s not surprising that the history in Canada of colonization of residential schools has left a lasting impression on these families and communities in terms of loss of language, loss of culture, and loss of land. There’s a community-based stress and a family-based stress that these children feel.”

Social factors also play a big role. She presented baseline findings from 196 youth with T2DM and 456 with T1DM, including measures such as the Socioeconomic Factor Index-Version 2 (SEFI-2), a way to assess socioeconomic characteristics based on Canadian Census data that reflects nonmedical social determinants of health. “It looks at factors like number of rooms in the house, single-parent households, maternal education attainment, and family income,” Dr. Wicklow explained. “The higher the SEFI-2 score, the lower your socioeconomic status is for the area you live in. Kids with T2DM generally live in areas of lower SES and lower socioeconomic index. They often live far away from health care providers. Many do not attend school and many are not with their biologic families, so we’ve had a lot of issues addressing child and family services, in particular in the phase of a chronic illness where our expectation is one thing and the family’s and community’s expectations of what’s realistic in terms of treatment and goals is another. We also have a lot of adolescent pregnancies.”

To date, about 80% of youth with T1D have seen a health care provider within the first year after transition from the pediatric diabetes clinic, compared with just over 50% of kids with T2D. “We transition youth with T1DM to internists, while our youth with T2DM go to itinerant physicians often back in their communities and/or rural family physicians,” she said. Between baseline and year 2, the rate of hospital admissions remained similar among T1DM at 11.6 and 11.8 admissions per 100 patient-years, respectively, but the number of hospital admissions for T2DM patients jumped from 20.1 to 25.5 admissions per 100 patient-years. “Kids with type 2 are showing up in the hospital a lot more than those with type 1 diabetes, but not for diabetes-related diagnoses,” Dr. Wicklow said. “We’re starting to look through the data now, and most of our kids are showing up with mental health complaints and issues. That’s why they’re getting hospitalized.”

Among ICARE study participants who have completed 3 years of follow-up, about 52% had albuminuria at their baseline visit and 48% sustained albuminuria throughout the study. About 26% progressed from normal levels of albuminuria to microalbuminuria, from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria, or from normal levels of albuminuria to macroalbuminuria. In addition, 16% persisted in the category that they were in, and 10% regressed. “The good news is, some of our kids get better over time,” Dr. Wicklow said. “The bad news is that the majority do not.”

Going forward, Dr. Wicklow and her associates work with an ICARE advisory group composed of children and families “who sit with us and talk about what mental health needs might be important, and how we should organize our study in a follow-up of the kids, to try and answer some of the questions that are important,” she said. “Working with the concept of the study’s theoretical framework, they acknowledged that the biological exposures are important, but they were also concerned about food security, finding strength/resilience within the community, and finding coping factors in terms of keeping themselves healthy with their diabetes. For some communities, they are concerned with basic needs. We’re working with them to help them progress, and to figure out how to best study children with type 2 diabetes.”

ICARE has received support from Diabetes Canada, Research Manitoba, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba (specifically the Diabetes Research Envisioned and Accomplished in Manitoba (DREAM) theme), and the University of Manitoba. Dr. Wicklow reported having no financial disclosures.