User login

S100B biomarker could reduce CT scans in children with mTBI

according to Charlotte Oris, PharmD, of the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France, and her associates.

In a meta-analysis of eight prospective cohort studies including a total of 601 children published in Pediatrics, researchers looked at the association between S100B serum levels and CT findings in 373 patients. The median serum concentrations of S100B were 0.47 mcg/L for patients with intracerebral lesions and 0.21 mcg/L for those without lesions (P less than .001).

Additionally, researchers collected data from 358 individuals included in two studies for the origin of mTBI. The median concentrations of S100B were 0.39 mcg/L for road accidents, 0.29 mcg/L for domestic accidents, and 0.18 mcg/L for sport-related accidents. The difference was statistically significant between the road accidents group and the domestic accidents group (P less than .001) and the difference between the road accidents group and the sport-related accidents group (P less than .001). It is noted that S100B specificity could be higher after a sport-related trauma.

“S100B protein serum levels, in combination with the PECARN [Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network] algorithm, could reduce the need for CT scans by one-third. In our additional analysis, based on 373 children, the importance of taking a blood sample 3 hours or less after trauma was underscored,” the researchers said.

“S100B represents a promising biomarker with 100% sensitivity. The limited specificity of S100B could be reevaluated for future research by using a combination of different brain biomarkers,” Dr. Oris and her colleagues concluded.

SOURCE: Oris C et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0037.

according to Charlotte Oris, PharmD, of the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France, and her associates.

In a meta-analysis of eight prospective cohort studies including a total of 601 children published in Pediatrics, researchers looked at the association between S100B serum levels and CT findings in 373 patients. The median serum concentrations of S100B were 0.47 mcg/L for patients with intracerebral lesions and 0.21 mcg/L for those without lesions (P less than .001).

Additionally, researchers collected data from 358 individuals included in two studies for the origin of mTBI. The median concentrations of S100B were 0.39 mcg/L for road accidents, 0.29 mcg/L for domestic accidents, and 0.18 mcg/L for sport-related accidents. The difference was statistically significant between the road accidents group and the domestic accidents group (P less than .001) and the difference between the road accidents group and the sport-related accidents group (P less than .001). It is noted that S100B specificity could be higher after a sport-related trauma.

“S100B protein serum levels, in combination with the PECARN [Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network] algorithm, could reduce the need for CT scans by one-third. In our additional analysis, based on 373 children, the importance of taking a blood sample 3 hours or less after trauma was underscored,” the researchers said.

“S100B represents a promising biomarker with 100% sensitivity. The limited specificity of S100B could be reevaluated for future research by using a combination of different brain biomarkers,” Dr. Oris and her colleagues concluded.

SOURCE: Oris C et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0037.

according to Charlotte Oris, PharmD, of the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France, and her associates.

In a meta-analysis of eight prospective cohort studies including a total of 601 children published in Pediatrics, researchers looked at the association between S100B serum levels and CT findings in 373 patients. The median serum concentrations of S100B were 0.47 mcg/L for patients with intracerebral lesions and 0.21 mcg/L for those without lesions (P less than .001).

Additionally, researchers collected data from 358 individuals included in two studies for the origin of mTBI. The median concentrations of S100B were 0.39 mcg/L for road accidents, 0.29 mcg/L for domestic accidents, and 0.18 mcg/L for sport-related accidents. The difference was statistically significant between the road accidents group and the domestic accidents group (P less than .001) and the difference between the road accidents group and the sport-related accidents group (P less than .001). It is noted that S100B specificity could be higher after a sport-related trauma.

“S100B protein serum levels, in combination with the PECARN [Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network] algorithm, could reduce the need for CT scans by one-third. In our additional analysis, based on 373 children, the importance of taking a blood sample 3 hours or less after trauma was underscored,” the researchers said.

“S100B represents a promising biomarker with 100% sensitivity. The limited specificity of S100B could be reevaluated for future research by using a combination of different brain biomarkers,” Dr. Oris and her colleagues concluded.

SOURCE: Oris C et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0037.

Does Migraine Transiently Open the Blood–Brain Barrier?

STOWE, VT—Experimental evidence suggests that migraine, particularly migraine with aura, is associated with cortical spreading depression (CSD) that transiently disrupts the blood–brain barrier (BBB). For some, the question is not whether this disruption occurs, but whether it is clinically relevant. For others, even the basic premise of a CSD-mediated disruption of the BBB is suspect. At the Headache Cooperative of New England’s 28th Annual Stowe Headache Symposium, a debate between two researchers from opposing sides of this controversy indicated that there was little common ground.

“Experiments in mice suggest that CSD might open the BBB and activate pain-sensitive fibers. However, you have heard nothing about data from humans, and in fact, many migraine patients report aura symptoms without head pain,” said Messoud Ashina, MD, PhD, Director of the Human Migraine Research Unit at the Danish Headache Center in Glostrup.

On the contrary, the scientific evidence that CSD opens the BBB is “incontrovertible,” according to Cenk Ayata, MD, PhD, Director of the Neurovascular Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown. “It is not a matter of whether the BBB opens, it is a matter of magnitude,” he said. “The critical question is whether it is clinically relevant.”

This controversy is of particular current interest. Although CSD has long been suspected to mediate migraine pain, a transient opening of the BBB may greatly affect the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies in development for migraine prophylaxis and treatment. Monoclonal antibodies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) have shown promise in ongoing trials, but an opportunity to target the CNS directly could improve their efficacy. Monoclonal antibodies are too large to cross the BBB without increasing the latter’s permeability.

What Is CSD?

CSD is a wave of intense neurologic depolarization that is considered the electrophysiologic substrate of migraine aura, according to Dr. Ayata. The “massive transmembrane ion and water shifts hit the cerebral vasculature during CSD like a tsunami,” he said. Citing more than two decades’ worth of research, Dr. Ayata explained that CSD is accompanied by upregulation of multiple neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that trigger large blood flow responses and disrupt cerebrovascular reflexes, such as neurovascular coupling.

Initial studies of the role of CSD and its potential for disrupting the BBB were primarily related to stroke and head trauma. Numerous studies have supported the hypothesis that CSD is the underlying mechanism of migraine aura and a putative trigger for migraine headache. The specific sequence of events leading to CSD in migraine remains unclear, but Dr. Ayata and colleagues have conducted experiments that suggest that “CSD alone, without attendant tissue injury, can produce a transient opening of the BBB.”

In murine models of migraine, Evans blue leaked into the CNS after noninvasive induction of CSD. No leakage was observed in control animals that underwent a sham induction. Other controlled experiments that included objective measures of brain edema after CSD corroborated the association between CSD and BBB disruption.

“The opening of the BBB starts sometime between three and six hours [after induction of CSD], reaches a peak at six to 12 hours, and then gradually declines over the next 24 hours or so,” said Dr. Ayata. The BBB is completely restored at 48 hours, he added.

The Potential Role of Transcytosis

The BBB consists of astrocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells with tight junctions that prevent most blood-borne substances from crossing into the CNS. Various processes can breach the BBB, and Dr. Ayata’s group is focusing on transcytosis. They hypothesize that ion pumps and other transporters cannot explain their observations that molecules as large as 70 kDa can pass through the BBB.

Transcytosis permits macromolecules from the luminal side of the endothelial cell to be brought into the cell by pinocytotic vesicles and to be released on the other side. It is a plausible mechanism for passage through the BBB, according to Dr. Ayata. Electron microscopy studies of BBB tissue from murine models strongly support this hypothesis.

“We found a significant increase in pinocytotic vesicles starting between three and six hours, but then a gradual decline to normal levels over the next 48 hours. This time course is exactly what we found in terms of leakage,” said Dr. Ayata. There was no evident change in endothelial tight junctions or in any other structure likely to provide an alternative mechanism for the observed BBB disruption, he added.

Although BBB disruption in an animal model of migraine is not proof of the same phenomenon in humans, Dr. Ayata suggested that the results are consistent with clinical observations. For example, a series of papers from 1985 to the present, including studies undertaken with gadolinium enhancement, found an association between severe migraine and documented edema. A twin study and studies of familial hemiplegic migraine also showed that CSD contributes to migraine pathogenesis and causes disruption of the BBB, he said.

Human Data Are Lacking

Although early studies provide a basis for the hypothesis that CSD is associated with migraine and might disrupt the BBB, clinical studies have consistently failed to link CSD with evidence of BBB disruption, said Dr. Ashina. In 1981, Olesen and colleagues reported cerebral hypoperfusion, a potential sign of CSD, followed by transient increases in cerebral perfusion (ie, hyperemia) during experimentally induced migraine aura.

“In some patients, headache disappeared when the hyperemia was observed, so there was no correlation,” said Dr. Ashina. Moreover, no changes in blood flow were observed when the same studies were conducted in patients with migraine without aura, and none of the studies reported changes in the permeability of the BBB in migraineurs with and without aura, according to Dr. Ashina. He and his colleagues at the Danish Headache Center remain active in this research.

He cited a 2017 study by Hougaard et al of 19 migraineurs with aura and 19 migraineurs without aura. Tissue perfusion in various parts of the brain was measured to assess change in BBB permeability. Patients underwent 3-T MRI during and in the absence of migraine attacks. “In aura patients, we found hyperperfusion in the brainstem during the headache phase of migraine with aura, while the BBB remained intact during attacks of migraine with aura,” said Dr. Ashina. Using sensitivity analyses, they looked for changes as small as 15%, but found nothing.

Other studies have looked more indirectly at the likelihood that the BBB is disrupted during migraine, but these, such as one that evaluated extracranial arterial dilatation during migraine attacks, have also been negative, according to Dr. Ashina. Studies of putative mechanisms for BBB disruption, such as one that evaluated the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases, have also failed to support BBB disruption. “Nothing out there provides any evidence whatsoever that relates directly to BBB opening during migraine attacks with or without aura,” said Dr. Ashina.

If the BBB undergoes a transient disruption during migraine, it remains unclear whether this disruption is clinically meaningful or provides new opportunities to time treatment. The introduction of monoclonal antibodies for migraine may inspire the research needed to resolve this question.

Dr. Ashina has financial relationships with Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Dr. Ayata has no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

—Ted Bosworth

Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(5):454-461.

Amin FM, Hougaard A, Cramer SP, et al. Intact blood-brain barrier during spontaneous attacks of migraine without aura: a 3T DCE-MRI study. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(9):1116-1124.

Ashina M, Tvedskov JF, Lipka K, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases during and outside of migraine attacks without aura. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(3):303-310.

Ayata C, Lauritzen M. Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(3):953-993.

Hougaard A, Amin FM, Christensen CE, et al. Increased brainstem perfusion, but no blood-brain barrier disruption, during attacks of migraine with aura. Brain. 2017;140(6):1633-1642.

Olesen J, Larsen B, Lauritzen M. Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol. 1981;9(4):344-352.

STOWE, VT—Experimental evidence suggests that migraine, particularly migraine with aura, is associated with cortical spreading depression (CSD) that transiently disrupts the blood–brain barrier (BBB). For some, the question is not whether this disruption occurs, but whether it is clinically relevant. For others, even the basic premise of a CSD-mediated disruption of the BBB is suspect. At the Headache Cooperative of New England’s 28th Annual Stowe Headache Symposium, a debate between two researchers from opposing sides of this controversy indicated that there was little common ground.

“Experiments in mice suggest that CSD might open the BBB and activate pain-sensitive fibers. However, you have heard nothing about data from humans, and in fact, many migraine patients report aura symptoms without head pain,” said Messoud Ashina, MD, PhD, Director of the Human Migraine Research Unit at the Danish Headache Center in Glostrup.

On the contrary, the scientific evidence that CSD opens the BBB is “incontrovertible,” according to Cenk Ayata, MD, PhD, Director of the Neurovascular Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown. “It is not a matter of whether the BBB opens, it is a matter of magnitude,” he said. “The critical question is whether it is clinically relevant.”

This controversy is of particular current interest. Although CSD has long been suspected to mediate migraine pain, a transient opening of the BBB may greatly affect the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies in development for migraine prophylaxis and treatment. Monoclonal antibodies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) have shown promise in ongoing trials, but an opportunity to target the CNS directly could improve their efficacy. Monoclonal antibodies are too large to cross the BBB without increasing the latter’s permeability.

What Is CSD?

CSD is a wave of intense neurologic depolarization that is considered the electrophysiologic substrate of migraine aura, according to Dr. Ayata. The “massive transmembrane ion and water shifts hit the cerebral vasculature during CSD like a tsunami,” he said. Citing more than two decades’ worth of research, Dr. Ayata explained that CSD is accompanied by upregulation of multiple neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that trigger large blood flow responses and disrupt cerebrovascular reflexes, such as neurovascular coupling.

Initial studies of the role of CSD and its potential for disrupting the BBB were primarily related to stroke and head trauma. Numerous studies have supported the hypothesis that CSD is the underlying mechanism of migraine aura and a putative trigger for migraine headache. The specific sequence of events leading to CSD in migraine remains unclear, but Dr. Ayata and colleagues have conducted experiments that suggest that “CSD alone, without attendant tissue injury, can produce a transient opening of the BBB.”

In murine models of migraine, Evans blue leaked into the CNS after noninvasive induction of CSD. No leakage was observed in control animals that underwent a sham induction. Other controlled experiments that included objective measures of brain edema after CSD corroborated the association between CSD and BBB disruption.

“The opening of the BBB starts sometime between three and six hours [after induction of CSD], reaches a peak at six to 12 hours, and then gradually declines over the next 24 hours or so,” said Dr. Ayata. The BBB is completely restored at 48 hours, he added.

The Potential Role of Transcytosis

The BBB consists of astrocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells with tight junctions that prevent most blood-borne substances from crossing into the CNS. Various processes can breach the BBB, and Dr. Ayata’s group is focusing on transcytosis. They hypothesize that ion pumps and other transporters cannot explain their observations that molecules as large as 70 kDa can pass through the BBB.

Transcytosis permits macromolecules from the luminal side of the endothelial cell to be brought into the cell by pinocytotic vesicles and to be released on the other side. It is a plausible mechanism for passage through the BBB, according to Dr. Ayata. Electron microscopy studies of BBB tissue from murine models strongly support this hypothesis.

“We found a significant increase in pinocytotic vesicles starting between three and six hours, but then a gradual decline to normal levels over the next 48 hours. This time course is exactly what we found in terms of leakage,” said Dr. Ayata. There was no evident change in endothelial tight junctions or in any other structure likely to provide an alternative mechanism for the observed BBB disruption, he added.

Although BBB disruption in an animal model of migraine is not proof of the same phenomenon in humans, Dr. Ayata suggested that the results are consistent with clinical observations. For example, a series of papers from 1985 to the present, including studies undertaken with gadolinium enhancement, found an association between severe migraine and documented edema. A twin study and studies of familial hemiplegic migraine also showed that CSD contributes to migraine pathogenesis and causes disruption of the BBB, he said.

Human Data Are Lacking

Although early studies provide a basis for the hypothesis that CSD is associated with migraine and might disrupt the BBB, clinical studies have consistently failed to link CSD with evidence of BBB disruption, said Dr. Ashina. In 1981, Olesen and colleagues reported cerebral hypoperfusion, a potential sign of CSD, followed by transient increases in cerebral perfusion (ie, hyperemia) during experimentally induced migraine aura.

“In some patients, headache disappeared when the hyperemia was observed, so there was no correlation,” said Dr. Ashina. Moreover, no changes in blood flow were observed when the same studies were conducted in patients with migraine without aura, and none of the studies reported changes in the permeability of the BBB in migraineurs with and without aura, according to Dr. Ashina. He and his colleagues at the Danish Headache Center remain active in this research.

He cited a 2017 study by Hougaard et al of 19 migraineurs with aura and 19 migraineurs without aura. Tissue perfusion in various parts of the brain was measured to assess change in BBB permeability. Patients underwent 3-T MRI during and in the absence of migraine attacks. “In aura patients, we found hyperperfusion in the brainstem during the headache phase of migraine with aura, while the BBB remained intact during attacks of migraine with aura,” said Dr. Ashina. Using sensitivity analyses, they looked for changes as small as 15%, but found nothing.

Other studies have looked more indirectly at the likelihood that the BBB is disrupted during migraine, but these, such as one that evaluated extracranial arterial dilatation during migraine attacks, have also been negative, according to Dr. Ashina. Studies of putative mechanisms for BBB disruption, such as one that evaluated the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases, have also failed to support BBB disruption. “Nothing out there provides any evidence whatsoever that relates directly to BBB opening during migraine attacks with or without aura,” said Dr. Ashina.

If the BBB undergoes a transient disruption during migraine, it remains unclear whether this disruption is clinically meaningful or provides new opportunities to time treatment. The introduction of monoclonal antibodies for migraine may inspire the research needed to resolve this question.

Dr. Ashina has financial relationships with Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Dr. Ayata has no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

—Ted Bosworth

Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(5):454-461.

Amin FM, Hougaard A, Cramer SP, et al. Intact blood-brain barrier during spontaneous attacks of migraine without aura: a 3T DCE-MRI study. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(9):1116-1124.

Ashina M, Tvedskov JF, Lipka K, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases during and outside of migraine attacks without aura. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(3):303-310.

Ayata C, Lauritzen M. Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(3):953-993.

Hougaard A, Amin FM, Christensen CE, et al. Increased brainstem perfusion, but no blood-brain barrier disruption, during attacks of migraine with aura. Brain. 2017;140(6):1633-1642.

Olesen J, Larsen B, Lauritzen M. Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol. 1981;9(4):344-352.

STOWE, VT—Experimental evidence suggests that migraine, particularly migraine with aura, is associated with cortical spreading depression (CSD) that transiently disrupts the blood–brain barrier (BBB). For some, the question is not whether this disruption occurs, but whether it is clinically relevant. For others, even the basic premise of a CSD-mediated disruption of the BBB is suspect. At the Headache Cooperative of New England’s 28th Annual Stowe Headache Symposium, a debate between two researchers from opposing sides of this controversy indicated that there was little common ground.

“Experiments in mice suggest that CSD might open the BBB and activate pain-sensitive fibers. However, you have heard nothing about data from humans, and in fact, many migraine patients report aura symptoms without head pain,” said Messoud Ashina, MD, PhD, Director of the Human Migraine Research Unit at the Danish Headache Center in Glostrup.

On the contrary, the scientific evidence that CSD opens the BBB is “incontrovertible,” according to Cenk Ayata, MD, PhD, Director of the Neurovascular Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown. “It is not a matter of whether the BBB opens, it is a matter of magnitude,” he said. “The critical question is whether it is clinically relevant.”

This controversy is of particular current interest. Although CSD has long been suspected to mediate migraine pain, a transient opening of the BBB may greatly affect the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies in development for migraine prophylaxis and treatment. Monoclonal antibodies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) have shown promise in ongoing trials, but an opportunity to target the CNS directly could improve their efficacy. Monoclonal antibodies are too large to cross the BBB without increasing the latter’s permeability.

What Is CSD?

CSD is a wave of intense neurologic depolarization that is considered the electrophysiologic substrate of migraine aura, according to Dr. Ayata. The “massive transmembrane ion and water shifts hit the cerebral vasculature during CSD like a tsunami,” he said. Citing more than two decades’ worth of research, Dr. Ayata explained that CSD is accompanied by upregulation of multiple neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that trigger large blood flow responses and disrupt cerebrovascular reflexes, such as neurovascular coupling.

Initial studies of the role of CSD and its potential for disrupting the BBB were primarily related to stroke and head trauma. Numerous studies have supported the hypothesis that CSD is the underlying mechanism of migraine aura and a putative trigger for migraine headache. The specific sequence of events leading to CSD in migraine remains unclear, but Dr. Ayata and colleagues have conducted experiments that suggest that “CSD alone, without attendant tissue injury, can produce a transient opening of the BBB.”

In murine models of migraine, Evans blue leaked into the CNS after noninvasive induction of CSD. No leakage was observed in control animals that underwent a sham induction. Other controlled experiments that included objective measures of brain edema after CSD corroborated the association between CSD and BBB disruption.

“The opening of the BBB starts sometime between three and six hours [after induction of CSD], reaches a peak at six to 12 hours, and then gradually declines over the next 24 hours or so,” said Dr. Ayata. The BBB is completely restored at 48 hours, he added.

The Potential Role of Transcytosis

The BBB consists of astrocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells with tight junctions that prevent most blood-borne substances from crossing into the CNS. Various processes can breach the BBB, and Dr. Ayata’s group is focusing on transcytosis. They hypothesize that ion pumps and other transporters cannot explain their observations that molecules as large as 70 kDa can pass through the BBB.

Transcytosis permits macromolecules from the luminal side of the endothelial cell to be brought into the cell by pinocytotic vesicles and to be released on the other side. It is a plausible mechanism for passage through the BBB, according to Dr. Ayata. Electron microscopy studies of BBB tissue from murine models strongly support this hypothesis.

“We found a significant increase in pinocytotic vesicles starting between three and six hours, but then a gradual decline to normal levels over the next 48 hours. This time course is exactly what we found in terms of leakage,” said Dr. Ayata. There was no evident change in endothelial tight junctions or in any other structure likely to provide an alternative mechanism for the observed BBB disruption, he added.

Although BBB disruption in an animal model of migraine is not proof of the same phenomenon in humans, Dr. Ayata suggested that the results are consistent with clinical observations. For example, a series of papers from 1985 to the present, including studies undertaken with gadolinium enhancement, found an association between severe migraine and documented edema. A twin study and studies of familial hemiplegic migraine also showed that CSD contributes to migraine pathogenesis and causes disruption of the BBB, he said.

Human Data Are Lacking

Although early studies provide a basis for the hypothesis that CSD is associated with migraine and might disrupt the BBB, clinical studies have consistently failed to link CSD with evidence of BBB disruption, said Dr. Ashina. In 1981, Olesen and colleagues reported cerebral hypoperfusion, a potential sign of CSD, followed by transient increases in cerebral perfusion (ie, hyperemia) during experimentally induced migraine aura.

“In some patients, headache disappeared when the hyperemia was observed, so there was no correlation,” said Dr. Ashina. Moreover, no changes in blood flow were observed when the same studies were conducted in patients with migraine without aura, and none of the studies reported changes in the permeability of the BBB in migraineurs with and without aura, according to Dr. Ashina. He and his colleagues at the Danish Headache Center remain active in this research.

He cited a 2017 study by Hougaard et al of 19 migraineurs with aura and 19 migraineurs without aura. Tissue perfusion in various parts of the brain was measured to assess change in BBB permeability. Patients underwent 3-T MRI during and in the absence of migraine attacks. “In aura patients, we found hyperperfusion in the brainstem during the headache phase of migraine with aura, while the BBB remained intact during attacks of migraine with aura,” said Dr. Ashina. Using sensitivity analyses, they looked for changes as small as 15%, but found nothing.

Other studies have looked more indirectly at the likelihood that the BBB is disrupted during migraine, but these, such as one that evaluated extracranial arterial dilatation during migraine attacks, have also been negative, according to Dr. Ashina. Studies of putative mechanisms for BBB disruption, such as one that evaluated the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases, have also failed to support BBB disruption. “Nothing out there provides any evidence whatsoever that relates directly to BBB opening during migraine attacks with or without aura,” said Dr. Ashina.

If the BBB undergoes a transient disruption during migraine, it remains unclear whether this disruption is clinically meaningful or provides new opportunities to time treatment. The introduction of monoclonal antibodies for migraine may inspire the research needed to resolve this question.

Dr. Ashina has financial relationships with Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Dr. Ayata has no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

—Ted Bosworth

Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(5):454-461.

Amin FM, Hougaard A, Cramer SP, et al. Intact blood-brain barrier during spontaneous attacks of migraine without aura: a 3T DCE-MRI study. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(9):1116-1124.

Ashina M, Tvedskov JF, Lipka K, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases during and outside of migraine attacks without aura. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(3):303-310.

Ayata C, Lauritzen M. Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(3):953-993.

Hougaard A, Amin FM, Christensen CE, et al. Increased brainstem perfusion, but no blood-brain barrier disruption, during attacks of migraine with aura. Brain. 2017;140(6):1633-1642.

Olesen J, Larsen B, Lauritzen M. Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol. 1981;9(4):344-352.

Study pits cryolipolysis versus HIFU for fat reduction in the flank region

DALLAS – While cryolipolysis and high-intensity focused ultrasound are both effective at reducing subcutaneous fat in the flank region, cryolipolysis appeared to be less painful and more effective in a small, randomized trial.

Noninvasive subcutaneous fat reduction is becoming increasingly popular, study author Farhaad R. Riyaz, MD, observed at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “High-intensity focused ultrasound seems to be less popular than cryolipolysis. It uses sound waves to create heat and is similar in technology to light traveling through a magnifying glass to create heat at a focal point. But the two technologies really haven’t been rigorously compared in the literature,” he added.

Dr. Riyaz and his associates in the division of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, enrolled 12 healthy female participants with a body mass index between 18 and 30 kg/m2 and moderate fat in the abdomen flanks. In the split-body, parallel-group trial, the subjects were randomized to cryolipolysis on one flank and to high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) on the contralateral side. Study participants were asked to maintain their weight throughout the 12-week study. Treatments were performed at baseline, week 4, and week 8, with a follow-up visit at week 12. The primary outcome was thickness of subcutaneous fat as measured by ultrasound; secondary outcomes included pain, patient-reported improvement, and total circumference of the abdomen and flanks.

The mean age of the 12 participants was 39 years, 8 were white, and most had Fitzpatrick skin types II and IV (33% and 42%, respectively). Dr. Riyaz reported that (P = .0007 and P = .0341, respectively), as measured by diagnostic ultrasound. The researchers noted significantly less fat in the flanks on the sides treated with cryolipolysis, compared with the sides treated with HIFU (P = .007). Study participants reported significantly more pain with HIFU compared with cryolipolysis (P = .0002).

“Although participant-reported improvement in the appearance of their flanks was significant for both treatments [P less than .0001], patients couldn’t appreciate a difference between the side that was treated with HIFU and the side that was treated with cryolipolysis,” Dr. Riyaz said. “In addition, the total abdominal circumference did not change throughout the study for either group.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

DALLAS – While cryolipolysis and high-intensity focused ultrasound are both effective at reducing subcutaneous fat in the flank region, cryolipolysis appeared to be less painful and more effective in a small, randomized trial.

Noninvasive subcutaneous fat reduction is becoming increasingly popular, study author Farhaad R. Riyaz, MD, observed at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “High-intensity focused ultrasound seems to be less popular than cryolipolysis. It uses sound waves to create heat and is similar in technology to light traveling through a magnifying glass to create heat at a focal point. But the two technologies really haven’t been rigorously compared in the literature,” he added.

Dr. Riyaz and his associates in the division of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, enrolled 12 healthy female participants with a body mass index between 18 and 30 kg/m2 and moderate fat in the abdomen flanks. In the split-body, parallel-group trial, the subjects were randomized to cryolipolysis on one flank and to high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) on the contralateral side. Study participants were asked to maintain their weight throughout the 12-week study. Treatments were performed at baseline, week 4, and week 8, with a follow-up visit at week 12. The primary outcome was thickness of subcutaneous fat as measured by ultrasound; secondary outcomes included pain, patient-reported improvement, and total circumference of the abdomen and flanks.

The mean age of the 12 participants was 39 years, 8 were white, and most had Fitzpatrick skin types II and IV (33% and 42%, respectively). Dr. Riyaz reported that (P = .0007 and P = .0341, respectively), as measured by diagnostic ultrasound. The researchers noted significantly less fat in the flanks on the sides treated with cryolipolysis, compared with the sides treated with HIFU (P = .007). Study participants reported significantly more pain with HIFU compared with cryolipolysis (P = .0002).

“Although participant-reported improvement in the appearance of their flanks was significant for both treatments [P less than .0001], patients couldn’t appreciate a difference between the side that was treated with HIFU and the side that was treated with cryolipolysis,” Dr. Riyaz said. “In addition, the total abdominal circumference did not change throughout the study for either group.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

DALLAS – While cryolipolysis and high-intensity focused ultrasound are both effective at reducing subcutaneous fat in the flank region, cryolipolysis appeared to be less painful and more effective in a small, randomized trial.

Noninvasive subcutaneous fat reduction is becoming increasingly popular, study author Farhaad R. Riyaz, MD, observed at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “High-intensity focused ultrasound seems to be less popular than cryolipolysis. It uses sound waves to create heat and is similar in technology to light traveling through a magnifying glass to create heat at a focal point. But the two technologies really haven’t been rigorously compared in the literature,” he added.

Dr. Riyaz and his associates in the division of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago, enrolled 12 healthy female participants with a body mass index between 18 and 30 kg/m2 and moderate fat in the abdomen flanks. In the split-body, parallel-group trial, the subjects were randomized to cryolipolysis on one flank and to high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) on the contralateral side. Study participants were asked to maintain their weight throughout the 12-week study. Treatments were performed at baseline, week 4, and week 8, with a follow-up visit at week 12. The primary outcome was thickness of subcutaneous fat as measured by ultrasound; secondary outcomes included pain, patient-reported improvement, and total circumference of the abdomen and flanks.

The mean age of the 12 participants was 39 years, 8 were white, and most had Fitzpatrick skin types II and IV (33% and 42%, respectively). Dr. Riyaz reported that (P = .0007 and P = .0341, respectively), as measured by diagnostic ultrasound. The researchers noted significantly less fat in the flanks on the sides treated with cryolipolysis, compared with the sides treated with HIFU (P = .007). Study participants reported significantly more pain with HIFU compared with cryolipolysis (P = .0002).

“Although participant-reported improvement in the appearance of their flanks was significant for both treatments [P less than .0001], patients couldn’t appreciate a difference between the side that was treated with HIFU and the side that was treated with cryolipolysis,” Dr. Riyaz said. “In addition, the total abdominal circumference did not change throughout the study for either group.”

He reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Both cryolipolysis and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) are effective at reducing subcutaneous fat in the flank region.

Major finding: At week 12 follow-up, both cryolipolysis and HIFU significantly reduced fat in the flanks, compared with baseline (P = .0007 and P = .0341, respectively), as measured by diagnostic ultrasound.

Study details: A split-body, parallel-group trial in which 12 women were randomized to cryolipolysis on one flank and to HIFU on the contralateral side.

Disclosures: Dr. Riyaz reported having no financial disclosures.

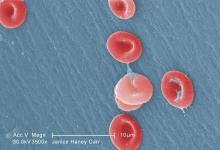

Too few Michigan children with SCD receive pneumococcal, meningococcal vaccines

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Key clinical point: Too few children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are receiving Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–recommended meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccines, including PCV13 and PPSV23.

Major finding:

Study details: The findings are based on a cohort study of children with and without SCD born in Michigan between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

Source: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Making a difference: ACOG’s guidance on low-dose aspirin for preventing superimposed preeclampsia

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

Commentary—A Logical and Modern Approach

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-Alzheimer’s disease contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all patients with Alzheimer’s disease at autopsy; these non-Alzheimer’s disease pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

This expensive framework might unintentionally lock out research that does not employ all these biomarkers either because of cost or because of clinical series–based studies. These biomarkers generally can be obtained only if paid for by a third party—typically a drug company. Some investigators may feel coerced into participating in studies they might not otherwise be inclined to do.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even more nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Scottsdale

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-Alzheimer’s disease contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all patients with Alzheimer’s disease at autopsy; these non-Alzheimer’s disease pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

This expensive framework might unintentionally lock out research that does not employ all these biomarkers either because of cost or because of clinical series–based studies. These biomarkers generally can be obtained only if paid for by a third party—typically a drug company. Some investigators may feel coerced into participating in studies they might not otherwise be inclined to do.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even more nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Scottsdale

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-Alzheimer’s disease contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all patients with Alzheimer’s disease at autopsy; these non-Alzheimer’s disease pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

This expensive framework might unintentionally lock out research that does not employ all these biomarkers either because of cost or because of clinical series–based studies. These biomarkers generally can be obtained only if paid for by a third party—typically a drug company. Some investigators may feel coerced into participating in studies they might not otherwise be inclined to do.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even more nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

—Richard J. Caselli, MD

Professor of Neurology

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Scottsdale

Suicide prevention starts with the patient’s narrative

WASHINGTON – An effective approach to suicide prevention engages the patient in a therapeutic relationship that starts with the patient’s narrative, Katherine A. Comtois, PhD, said at the American Association of Suicidality annual conference.

“The narrative should be the first touch” with the patient, advised Dr. Comtois, professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Start the narrative and form a connection, and then get to the other stuff.” She also recommended that therapists place themselves next to the patient, “court” the patient, be persistent, give positive reinforcement, and “give it all you’ve got.”

She endorsed the Aeschi model for suicide prevention, the treatment approaches recommended in The Way Forward, published in 2014 by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, and application of dialectical behavior therapy.

Dr. Comtois subdivided therapeutic interventions into two broad categories: management and treatment.

Management uses interventions aimed at modifying risk factors and reducing risks that relate to suicide, such as connectedness, treatment of the diagnosis, means safety, and safety planning; external factors that affect suicide risk. Although a collaborative approach between the therapist and patient is ideal for achieving management goals, it is not mandatory.

Treatment involves interventions that get at the internal factors that intrinsically drive a patient to suicide and aims to resolve the risk they pose. By necessity, treatment is a collaborative process. Ideally over time, the collaboration allows the patients gain confidence and take responsibility for self-managing their internal suicide risks.

She stressed the importance of a therapist orienting a patient to the management style to expect, “so what you do is not a surprise.” The therapist should listen to the patient’s goals, and carefully review expectations and a step-by-step plan. If the patient identifies potential problems and limitations, Dr. Comtois suggested commiserating with the patient about difficulties but not justifying them. For example, reviewing with patients how likely you will be to answer their phone call, what would likely happen during and as a result of a call, and offer the patients your advice on what to do if you can’t answer their call.

Dr. Comtois acknowledged that some clinicians fear managing and treating a suicidal patient, and advised “getting past your fear to help the client find a path forward. If you can get past your fear” the intervention often boils down to “clinical common sense: Things you would know how to handle if suicide weren’t involved.” If clinicians feel they can’t help, she suggested learning new skills to make assistance possible, or referring the patient to someone else who could help. “Negligence is not making a wrong decision; it’s doing nothing. Liability risk is often a huge fear,” but if the clinician at least makes a consult, that reduces the risk of potential negligence. She warned against referring suicidal patients to a hospital emergency department. “In this day and age, the emergency department is not a source of treatment; it’s a gatekeeper.”

While published evidence documents the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy and case management for preventing suicide and self-harm biological treatments, including antidepressants, lithium, and other psychopharmacology have not been effective, she said.

Dr. Comtois had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – An effective approach to suicide prevention engages the patient in a therapeutic relationship that starts with the patient’s narrative, Katherine A. Comtois, PhD, said at the American Association of Suicidality annual conference.

“The narrative should be the first touch” with the patient, advised Dr. Comtois, professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Start the narrative and form a connection, and then get to the other stuff.” She also recommended that therapists place themselves next to the patient, “court” the patient, be persistent, give positive reinforcement, and “give it all you’ve got.”

She endorsed the Aeschi model for suicide prevention, the treatment approaches recommended in The Way Forward, published in 2014 by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, and application of dialectical behavior therapy.

Dr. Comtois subdivided therapeutic interventions into two broad categories: management and treatment.

Management uses interventions aimed at modifying risk factors and reducing risks that relate to suicide, such as connectedness, treatment of the diagnosis, means safety, and safety planning; external factors that affect suicide risk. Although a collaborative approach between the therapist and patient is ideal for achieving management goals, it is not mandatory.

Treatment involves interventions that get at the internal factors that intrinsically drive a patient to suicide and aims to resolve the risk they pose. By necessity, treatment is a collaborative process. Ideally over time, the collaboration allows the patients gain confidence and take responsibility for self-managing their internal suicide risks.

She stressed the importance of a therapist orienting a patient to the management style to expect, “so what you do is not a surprise.” The therapist should listen to the patient’s goals, and carefully review expectations and a step-by-step plan. If the patient identifies potential problems and limitations, Dr. Comtois suggested commiserating with the patient about difficulties but not justifying them. For example, reviewing with patients how likely you will be to answer their phone call, what would likely happen during and as a result of a call, and offer the patients your advice on what to do if you can’t answer their call.

Dr. Comtois acknowledged that some clinicians fear managing and treating a suicidal patient, and advised “getting past your fear to help the client find a path forward. If you can get past your fear” the intervention often boils down to “clinical common sense: Things you would know how to handle if suicide weren’t involved.” If clinicians feel they can’t help, she suggested learning new skills to make assistance possible, or referring the patient to someone else who could help. “Negligence is not making a wrong decision; it’s doing nothing. Liability risk is often a huge fear,” but if the clinician at least makes a consult, that reduces the risk of potential negligence. She warned against referring suicidal patients to a hospital emergency department. “In this day and age, the emergency department is not a source of treatment; it’s a gatekeeper.”

While published evidence documents the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy and case management for preventing suicide and self-harm biological treatments, including antidepressants, lithium, and other psychopharmacology have not been effective, she said.

Dr. Comtois had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – An effective approach to suicide prevention engages the patient in a therapeutic relationship that starts with the patient’s narrative, Katherine A. Comtois, PhD, said at the American Association of Suicidality annual conference.

“The narrative should be the first touch” with the patient, advised Dr. Comtois, professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Start the narrative and form a connection, and then get to the other stuff.” She also recommended that therapists place themselves next to the patient, “court” the patient, be persistent, give positive reinforcement, and “give it all you’ve got.”