User login

Perianal Basal Cell Carcinoma Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the United States1 and most commonly occurs in sun-exposed areas. Although BCCs can and do develop on other non–sun-exposed areas of the body, BCCs of the perianal or genital regions are very rare (0.27% of cases). It is estimated that perianal BCCs account for less than 0.08% of all BCCs.2

We present a case of a superficial nodular perianal BCC that was discovered following an annual total-body skin examination and was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS).

Case Report

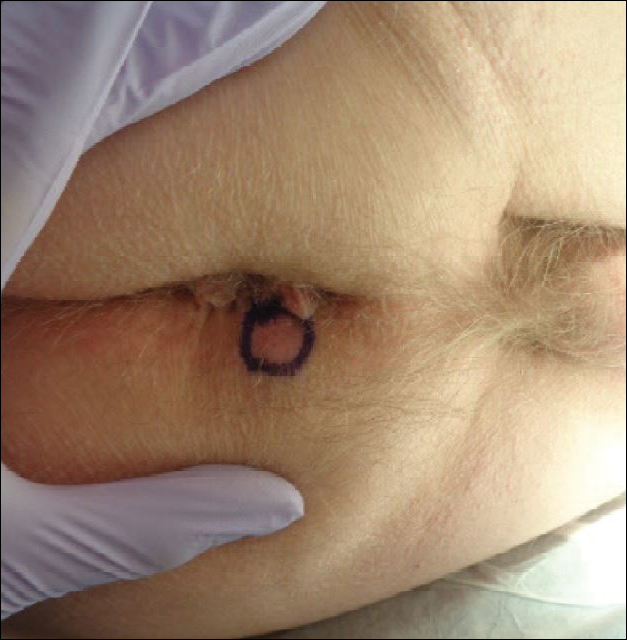

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for an annual total-body skin examination as well as evaluation of a new submental skin lesion. The patient’s medical history included successfully treated malignant melanoma in situ, multiple actinic keratoses, and an eccrine carcinoma. His family history was noncontributory. Inspection of the submental lesion revealed a pearly, 1.8-cm, telangiectatic, nodular plaque that was highly suspected to be a BCC. During the examination, a 1-cm pinkish-red plaque was found on the skin in the left perianal region (Figure 1). The patient was unaware of the lesion and did not report any symptoms upon questioning.

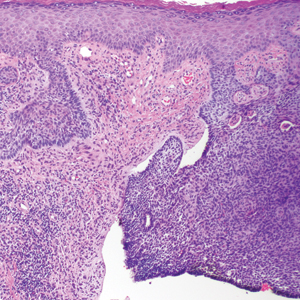

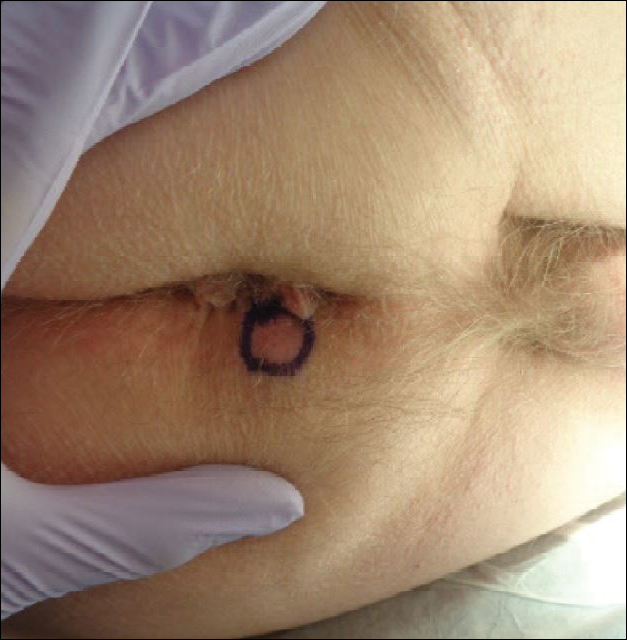

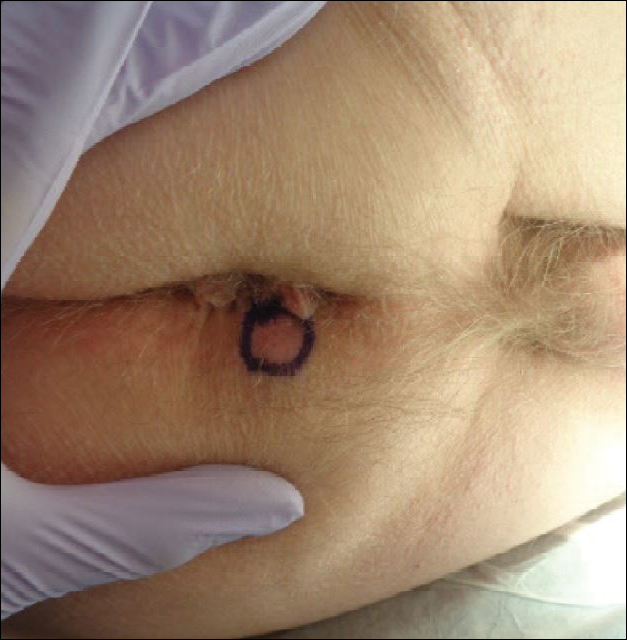

A shave biopsy of the submental lesion confirmed a diagnosis of micronodular BCC, and the patient was referred for MMS. It was decided to reevaluate the perianal lesion clinically at a follow-up appointment 2 months later and biopsy if it had not resolved. However, the patient did not attend the 2-month follow-up visit as scheduled, and it was not until the following year at his next annual total-body skin examination that the perianal lesion was rechecked. The lesion was unchanged at the time and was similar to the previous findings in both appearance and size. A punch biopsy was performed, and the pathology showed a superficial nodular perianal BCC (Figure 2). The perianal BCC was excised during a 2-stage MMS procedure with no recurrence at 6-month follow-up (Figure 3).

Comment

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the differential diagnosis for this perianal lesion included an inflammatory or infectious dermatosis. Its asymptomatic nature made it difficult to determine how long it had been present. The lack of resolution on reevaluation of the lesion 1 year later raised the possibilities of amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and lichen planus. Basal cell carcinoma was much lower in the differential diagnosis, as BCCs rarely are found in this area of the body; in fact, BCCs account for 0.2% of all anorectal neoplasms,3 and less than 0.08% of BCCs will occur in the perianal region.2

This challenging presentation is common for BCCs found in the perianal and perineal regions, as they are difficult to diagnose and often are overlooked as inflammatory dermatoses.4,5 The infrequency of perianal BCC reported in the literature as well as the predominance of BCC in sun-exposed areas makes it difficult for dermatologists to diagnose perianal BCC without biopsy. Another feature indicative of this diagnostic difficulty is that the average size of perianal and perineal BCCs has been found to be 1.95 cm.2 Without thorough and routine total-body skin examinations, there is no reliable way to catch asymptomatic BCCs in the perianal region until they have progressed far enough to become symptomatic. When possible, we recommend that dermatologists check the genital and anal regions during skin examinations and biopsy any suspicious lesions.

This case also highlights the challenge of missed appointments, which dermatologists also consistently face. Nonattendance rates in US dermatology clinics have been estimated at 17%,6 18.6%,7 19.4%,8 and 23.9%9 and present a challenge for even the best-run practices. Among patients with missed appointments, the most frequently stated reason in one survey was forgetting, and 24% of those contacted reported that they had not been reminded of their appointment.8 Many of the patients surveyed also expressed that they had preferred methods of receiving reminders such as e-mail or text message, which fell outside of traditional contact methods (eg, phone calls, voicemails). Confirming appointments ahead of time can reduce the number of missed appointments due to patient forgetfulness, and incorporating multiple communication modalities may lead to more effective appointment reminders.

Conclusion

Perianal BCC is challenging to diagnose and easy to overlook. Basal cell carcinoma is rarely found in the perianal regions and accounts for a fraction of all anorectal neoplasms. We recommend thorough total-body skin examinations that include the genital region and gluteal cleft when possible and encourage physicians to biopsy suspicious lesions in these regions. Routine, thorough total-body skin examinations can reveal neoplasms when they are smaller and asymptomatic. When surgical excision is indicated, MMS is an effective way to preserve as much tissue as possible and minimize recurrence.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Gibson GE, Ahmed I. Perianal and genital basal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:68-71.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- Bulur I, Boyuk E, Saracoglu ZN, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:25-28.

- Collins PS, Farber GA, Hegre AM. Basal-cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:711-714.

- Penneys NS, Glaser DA. The incidence of cancellation and nonattendance at a dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;40:714-718.

- Cronin P, DeCoste L, Kimball A. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149:1435-1437.

- Moustafa FA, Ramsey L, Huang KE, et al. Factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. Cutis. 2015;96:E20-E23.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the United States1 and most commonly occurs in sun-exposed areas. Although BCCs can and do develop on other non–sun-exposed areas of the body, BCCs of the perianal or genital regions are very rare (0.27% of cases). It is estimated that perianal BCCs account for less than 0.08% of all BCCs.2

We present a case of a superficial nodular perianal BCC that was discovered following an annual total-body skin examination and was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS).

Case Report

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for an annual total-body skin examination as well as evaluation of a new submental skin lesion. The patient’s medical history included successfully treated malignant melanoma in situ, multiple actinic keratoses, and an eccrine carcinoma. His family history was noncontributory. Inspection of the submental lesion revealed a pearly, 1.8-cm, telangiectatic, nodular plaque that was highly suspected to be a BCC. During the examination, a 1-cm pinkish-red plaque was found on the skin in the left perianal region (Figure 1). The patient was unaware of the lesion and did not report any symptoms upon questioning.

A shave biopsy of the submental lesion confirmed a diagnosis of micronodular BCC, and the patient was referred for MMS. It was decided to reevaluate the perianal lesion clinically at a follow-up appointment 2 months later and biopsy if it had not resolved. However, the patient did not attend the 2-month follow-up visit as scheduled, and it was not until the following year at his next annual total-body skin examination that the perianal lesion was rechecked. The lesion was unchanged at the time and was similar to the previous findings in both appearance and size. A punch biopsy was performed, and the pathology showed a superficial nodular perianal BCC (Figure 2). The perianal BCC was excised during a 2-stage MMS procedure with no recurrence at 6-month follow-up (Figure 3).

Comment

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the differential diagnosis for this perianal lesion included an inflammatory or infectious dermatosis. Its asymptomatic nature made it difficult to determine how long it had been present. The lack of resolution on reevaluation of the lesion 1 year later raised the possibilities of amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and lichen planus. Basal cell carcinoma was much lower in the differential diagnosis, as BCCs rarely are found in this area of the body; in fact, BCCs account for 0.2% of all anorectal neoplasms,3 and less than 0.08% of BCCs will occur in the perianal region.2

This challenging presentation is common for BCCs found in the perianal and perineal regions, as they are difficult to diagnose and often are overlooked as inflammatory dermatoses.4,5 The infrequency of perianal BCC reported in the literature as well as the predominance of BCC in sun-exposed areas makes it difficult for dermatologists to diagnose perianal BCC without biopsy. Another feature indicative of this diagnostic difficulty is that the average size of perianal and perineal BCCs has been found to be 1.95 cm.2 Without thorough and routine total-body skin examinations, there is no reliable way to catch asymptomatic BCCs in the perianal region until they have progressed far enough to become symptomatic. When possible, we recommend that dermatologists check the genital and anal regions during skin examinations and biopsy any suspicious lesions.

This case also highlights the challenge of missed appointments, which dermatologists also consistently face. Nonattendance rates in US dermatology clinics have been estimated at 17%,6 18.6%,7 19.4%,8 and 23.9%9 and present a challenge for even the best-run practices. Among patients with missed appointments, the most frequently stated reason in one survey was forgetting, and 24% of those contacted reported that they had not been reminded of their appointment.8 Many of the patients surveyed also expressed that they had preferred methods of receiving reminders such as e-mail or text message, which fell outside of traditional contact methods (eg, phone calls, voicemails). Confirming appointments ahead of time can reduce the number of missed appointments due to patient forgetfulness, and incorporating multiple communication modalities may lead to more effective appointment reminders.

Conclusion

Perianal BCC is challenging to diagnose and easy to overlook. Basal cell carcinoma is rarely found in the perianal regions and accounts for a fraction of all anorectal neoplasms. We recommend thorough total-body skin examinations that include the genital region and gluteal cleft when possible and encourage physicians to biopsy suspicious lesions in these regions. Routine, thorough total-body skin examinations can reveal neoplasms when they are smaller and asymptomatic. When surgical excision is indicated, MMS is an effective way to preserve as much tissue as possible and minimize recurrence.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the United States1 and most commonly occurs in sun-exposed areas. Although BCCs can and do develop on other non–sun-exposed areas of the body, BCCs of the perianal or genital regions are very rare (0.27% of cases). It is estimated that perianal BCCs account for less than 0.08% of all BCCs.2

We present a case of a superficial nodular perianal BCC that was discovered following an annual total-body skin examination and was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS).

Case Report

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for an annual total-body skin examination as well as evaluation of a new submental skin lesion. The patient’s medical history included successfully treated malignant melanoma in situ, multiple actinic keratoses, and an eccrine carcinoma. His family history was noncontributory. Inspection of the submental lesion revealed a pearly, 1.8-cm, telangiectatic, nodular plaque that was highly suspected to be a BCC. During the examination, a 1-cm pinkish-red plaque was found on the skin in the left perianal region (Figure 1). The patient was unaware of the lesion and did not report any symptoms upon questioning.

A shave biopsy of the submental lesion confirmed a diagnosis of micronodular BCC, and the patient was referred for MMS. It was decided to reevaluate the perianal lesion clinically at a follow-up appointment 2 months later and biopsy if it had not resolved. However, the patient did not attend the 2-month follow-up visit as scheduled, and it was not until the following year at his next annual total-body skin examination that the perianal lesion was rechecked. The lesion was unchanged at the time and was similar to the previous findings in both appearance and size. A punch biopsy was performed, and the pathology showed a superficial nodular perianal BCC (Figure 2). The perianal BCC was excised during a 2-stage MMS procedure with no recurrence at 6-month follow-up (Figure 3).

Comment

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the differential diagnosis for this perianal lesion included an inflammatory or infectious dermatosis. Its asymptomatic nature made it difficult to determine how long it had been present. The lack of resolution on reevaluation of the lesion 1 year later raised the possibilities of amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and lichen planus. Basal cell carcinoma was much lower in the differential diagnosis, as BCCs rarely are found in this area of the body; in fact, BCCs account for 0.2% of all anorectal neoplasms,3 and less than 0.08% of BCCs will occur in the perianal region.2

This challenging presentation is common for BCCs found in the perianal and perineal regions, as they are difficult to diagnose and often are overlooked as inflammatory dermatoses.4,5 The infrequency of perianal BCC reported in the literature as well as the predominance of BCC in sun-exposed areas makes it difficult for dermatologists to diagnose perianal BCC without biopsy. Another feature indicative of this diagnostic difficulty is that the average size of perianal and perineal BCCs has been found to be 1.95 cm.2 Without thorough and routine total-body skin examinations, there is no reliable way to catch asymptomatic BCCs in the perianal region until they have progressed far enough to become symptomatic. When possible, we recommend that dermatologists check the genital and anal regions during skin examinations and biopsy any suspicious lesions.

This case also highlights the challenge of missed appointments, which dermatologists also consistently face. Nonattendance rates in US dermatology clinics have been estimated at 17%,6 18.6%,7 19.4%,8 and 23.9%9 and present a challenge for even the best-run practices. Among patients with missed appointments, the most frequently stated reason in one survey was forgetting, and 24% of those contacted reported that they had not been reminded of their appointment.8 Many of the patients surveyed also expressed that they had preferred methods of receiving reminders such as e-mail or text message, which fell outside of traditional contact methods (eg, phone calls, voicemails). Confirming appointments ahead of time can reduce the number of missed appointments due to patient forgetfulness, and incorporating multiple communication modalities may lead to more effective appointment reminders.

Conclusion

Perianal BCC is challenging to diagnose and easy to overlook. Basal cell carcinoma is rarely found in the perianal regions and accounts for a fraction of all anorectal neoplasms. We recommend thorough total-body skin examinations that include the genital region and gluteal cleft when possible and encourage physicians to biopsy suspicious lesions in these regions. Routine, thorough total-body skin examinations can reveal neoplasms when they are smaller and asymptomatic. When surgical excision is indicated, MMS is an effective way to preserve as much tissue as possible and minimize recurrence.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Gibson GE, Ahmed I. Perianal and genital basal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:68-71.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- Bulur I, Boyuk E, Saracoglu ZN, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:25-28.

- Collins PS, Farber GA, Hegre AM. Basal-cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:711-714.

- Penneys NS, Glaser DA. The incidence of cancellation and nonattendance at a dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;40:714-718.

- Cronin P, DeCoste L, Kimball A. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149:1435-1437.

- Moustafa FA, Ramsey L, Huang KE, et al. Factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. Cutis. 2015;96:E20-E23.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Gibson GE, Ahmed I. Perianal and genital basal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:68-71.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- Bulur I, Boyuk E, Saracoglu ZN, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:25-28.

- Collins PS, Farber GA, Hegre AM. Basal-cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:711-714.

- Penneys NS, Glaser DA. The incidence of cancellation and nonattendance at a dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;40:714-718.

- Cronin P, DeCoste L, Kimball A. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149:1435-1437.

- Moustafa FA, Ramsey L, Huang KE, et al. Factors associated with missed dermatology appointments. Cutis. 2015;96:E20-E23.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

Practice Points

- Basal cell carcinoma is less common in non–sun-exposed areas of the body and is exceptionally rare in the perineal and perianal regions.

- Thorough total-body skin examinations may lead to early detection of asymptomatic skin lesions, allowing for earlier and less invasive treatment.

- Appointment attendance and patient compliance are common challenges that dermatologists face. Patient reminders via their preferred method of communication may help reduce missed dermatology appointments.

MDedge Daily News: How to handle opioid constipation

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

SAMHSA Helps Translate Science Into Real-Life Practice

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has launched a new Resource Center, aiming to give communities, clinicians, policy makers, and others the tools they need to put evidence-based information into practice.

The Evidence-Based Resource Center (www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center) provides new or updated Treatment Improvement Protocols, tool kits, resource guides, clinical practice guidelines , and other science-based resources. The website has an easy-to-use point-and-click system. Users can search by topic, resource, target population, and target audience. The site also includes an opioid-specific resources section.

The center is part of a new comprehensive approach that allows rapid development and dissemination of the latest expert consensus on prevention, treatment, and recovery, SAMHSA says. It also provides communities and practitioners with tools to facilitate comprehensive needs assessment, match interventions to those needs, support implementation, and evaluate and incorporate continuous quality improvement as they translate science into action.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has launched a new Resource Center, aiming to give communities, clinicians, policy makers, and others the tools they need to put evidence-based information into practice.

The Evidence-Based Resource Center (www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center) provides new or updated Treatment Improvement Protocols, tool kits, resource guides, clinical practice guidelines , and other science-based resources. The website has an easy-to-use point-and-click system. Users can search by topic, resource, target population, and target audience. The site also includes an opioid-specific resources section.

The center is part of a new comprehensive approach that allows rapid development and dissemination of the latest expert consensus on prevention, treatment, and recovery, SAMHSA says. It also provides communities and practitioners with tools to facilitate comprehensive needs assessment, match interventions to those needs, support implementation, and evaluate and incorporate continuous quality improvement as they translate science into action.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has launched a new Resource Center, aiming to give communities, clinicians, policy makers, and others the tools they need to put evidence-based information into practice.

The Evidence-Based Resource Center (www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center) provides new or updated Treatment Improvement Protocols, tool kits, resource guides, clinical practice guidelines , and other science-based resources. The website has an easy-to-use point-and-click system. Users can search by topic, resource, target population, and target audience. The site also includes an opioid-specific resources section.

The center is part of a new comprehensive approach that allows rapid development and dissemination of the latest expert consensus on prevention, treatment, and recovery, SAMHSA says. It also provides communities and practitioners with tools to facilitate comprehensive needs assessment, match interventions to those needs, support implementation, and evaluate and incorporate continuous quality improvement as they translate science into action.

‘Essential’ genes could be targeted to treat malaria

More than 2000 genes are “essential” for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, according to research published in Science.

Researchers identified 2680 genes that appear necessary for growth and survival during P falciparum’s asexual blood stage.

The researchers therefore believe these genes could be viable therapeutic targets for P falciparum malaria.

“Malaria parasites are extremely technically difficult to manipulate and sequence, and, until this study, only a few of P falciparum’s essential genes had been determined,” said study author Iraad Bronner, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK.

“Our technological advances enabled us to identify all the essential genes in P falciparum—the first time this has been possible for a human malaria parasite.”

To determine which genes P falciparum needs to survive and thrive, the researchers disrupted the parasite’s genes.

The team used piggyBac-transposon insertional mutagenesis to inactivate genes at random and then used DNA sequencing technology to identify which genes were affected.

The researchers made more than 38,000 mutations, then looked for genes that hadn’t been changed, implying they were essential for P falciparum to survive and grow.

This revealed 2680 non-mutable genes, about 1000 of which are conserved in all Plasmodium species and have unknown functions.

“What our team has done is develop a way to analyze every gene in this parasite’s genome,” said study author John H. Adams, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“Using our genetic analysis tools, we’re able to determine the relative importance of each gene for parasite survival. This understanding will help guide future drug development efforts targeting those essential genes.”

The researchers noted that the proteasome pathway had a “high ratio of essential to dispensable genes,” and recent research has linked this pathway to resistance to artemisinin combination therapy.

“We need new drug targets against malaria now more than ever, since our current antimalarial drugs are failing,” said study author Julian C. Rayner, PhD, of Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“This is the first large-scale genetic study in the major human malaria parasite P falciparum and gives a list of 2680 essential genes that researchers can prioritize as promising possible drug targets. We hope this functional genomics approach will help to speed up the pipeline to develop new treatments for this devastating disease.”

More than 2000 genes are “essential” for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, according to research published in Science.

Researchers identified 2680 genes that appear necessary for growth and survival during P falciparum’s asexual blood stage.

The researchers therefore believe these genes could be viable therapeutic targets for P falciparum malaria.

“Malaria parasites are extremely technically difficult to manipulate and sequence, and, until this study, only a few of P falciparum’s essential genes had been determined,” said study author Iraad Bronner, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK.

“Our technological advances enabled us to identify all the essential genes in P falciparum—the first time this has been possible for a human malaria parasite.”

To determine which genes P falciparum needs to survive and thrive, the researchers disrupted the parasite’s genes.

The team used piggyBac-transposon insertional mutagenesis to inactivate genes at random and then used DNA sequencing technology to identify which genes were affected.

The researchers made more than 38,000 mutations, then looked for genes that hadn’t been changed, implying they were essential for P falciparum to survive and grow.

This revealed 2680 non-mutable genes, about 1000 of which are conserved in all Plasmodium species and have unknown functions.

“What our team has done is develop a way to analyze every gene in this parasite’s genome,” said study author John H. Adams, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“Using our genetic analysis tools, we’re able to determine the relative importance of each gene for parasite survival. This understanding will help guide future drug development efforts targeting those essential genes.”

The researchers noted that the proteasome pathway had a “high ratio of essential to dispensable genes,” and recent research has linked this pathway to resistance to artemisinin combination therapy.

“We need new drug targets against malaria now more than ever, since our current antimalarial drugs are failing,” said study author Julian C. Rayner, PhD, of Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“This is the first large-scale genetic study in the major human malaria parasite P falciparum and gives a list of 2680 essential genes that researchers can prioritize as promising possible drug targets. We hope this functional genomics approach will help to speed up the pipeline to develop new treatments for this devastating disease.”

More than 2000 genes are “essential” for the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, according to research published in Science.

Researchers identified 2680 genes that appear necessary for growth and survival during P falciparum’s asexual blood stage.

The researchers therefore believe these genes could be viable therapeutic targets for P falciparum malaria.

“Malaria parasites are extremely technically difficult to manipulate and sequence, and, until this study, only a few of P falciparum’s essential genes had been determined,” said study author Iraad Bronner, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK.

“Our technological advances enabled us to identify all the essential genes in P falciparum—the first time this has been possible for a human malaria parasite.”

To determine which genes P falciparum needs to survive and thrive, the researchers disrupted the parasite’s genes.

The team used piggyBac-transposon insertional mutagenesis to inactivate genes at random and then used DNA sequencing technology to identify which genes were affected.

The researchers made more than 38,000 mutations, then looked for genes that hadn’t been changed, implying they were essential for P falciparum to survive and grow.

This revealed 2680 non-mutable genes, about 1000 of which are conserved in all Plasmodium species and have unknown functions.

“What our team has done is develop a way to analyze every gene in this parasite’s genome,” said study author John H. Adams, PhD, of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

“Using our genetic analysis tools, we’re able to determine the relative importance of each gene for parasite survival. This understanding will help guide future drug development efforts targeting those essential genes.”

The researchers noted that the proteasome pathway had a “high ratio of essential to dispensable genes,” and recent research has linked this pathway to resistance to artemisinin combination therapy.

“We need new drug targets against malaria now more than ever, since our current antimalarial drugs are failing,” said study author Julian C. Rayner, PhD, of Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“This is the first large-scale genetic study in the major human malaria parasite P falciparum and gives a list of 2680 essential genes that researchers can prioritize as promising possible drug targets. We hope this functional genomics approach will help to speed up the pipeline to develop new treatments for this devastating disease.”

Study shows increased risk of VTE among earthquake evacuees

New research has revealed a link between earthquake evacuation and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The study showed that people who spent the night in their cars after the Kumamoto earthquakes had an increased risk of VTE.

Researchers have therefore called for education about the risk of VTE among people who remain seated and immobile in vehicles for prolonged periods.

“Preventive awareness activities by professional medical teams, supported by education in the media about the risk of VTEs after spending the night in a vehicle, and raising awareness of evacuation centers could lead to a reduced number of victims of VTE,” said Seiji Hokimoto, MD, PhD, of Kumamoto University in Kumamoto, Japan.

Dr Hokimoto and colleagues made this point in a letter published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The researchers studied the aftermath of the Kumamoto earthquakes that occurred in April 2016.

The team noted that a high number of aftershocks at night prompted many people to evacuate their homes. Although some individuals reached a public evacuation shelter, many were forced to stay in their vehicles overnight.

To assess the impact of remaining seated in cars for extended periods of time, the researchers gathered data from 21 local medical institutions.

They found that 51 patients were hospitalized for VTE after the earthquakes, including 35 who developed pulmonary embolism (PE).

Most of the patients who developed VTE had spent the night in a vehicle (82.4%, n=42).

The researchers found that VTE patients who spent the night in a vehicle were significantly younger than patients who did not, with mean ages of 64.6 ± 13.3 and 79.8 ± 12.1, respectively (P=0.001).

The mean time to onset of VTE after the earthquakes was significantly shorter in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—7.3 ± 5.3 days vs 20.1 ± 25.6 days (P=0.003).

And the incidence of PE was significantly higher in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—83% vs 33% (P=0.001).

“This is a dramatic example of the risks inherent in spending prolonged periods immobilized in a cramped position,” said Stanley Nattel, MD, editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

“It is an important reminder of a public health point and reinforces the need to get up and walk around regularly when on an airplane or when forced to stay in a car for a long time.”

New research has revealed a link between earthquake evacuation and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The study showed that people who spent the night in their cars after the Kumamoto earthquakes had an increased risk of VTE.

Researchers have therefore called for education about the risk of VTE among people who remain seated and immobile in vehicles for prolonged periods.

“Preventive awareness activities by professional medical teams, supported by education in the media about the risk of VTEs after spending the night in a vehicle, and raising awareness of evacuation centers could lead to a reduced number of victims of VTE,” said Seiji Hokimoto, MD, PhD, of Kumamoto University in Kumamoto, Japan.

Dr Hokimoto and colleagues made this point in a letter published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The researchers studied the aftermath of the Kumamoto earthquakes that occurred in April 2016.

The team noted that a high number of aftershocks at night prompted many people to evacuate their homes. Although some individuals reached a public evacuation shelter, many were forced to stay in their vehicles overnight.

To assess the impact of remaining seated in cars for extended periods of time, the researchers gathered data from 21 local medical institutions.

They found that 51 patients were hospitalized for VTE after the earthquakes, including 35 who developed pulmonary embolism (PE).

Most of the patients who developed VTE had spent the night in a vehicle (82.4%, n=42).

The researchers found that VTE patients who spent the night in a vehicle were significantly younger than patients who did not, with mean ages of 64.6 ± 13.3 and 79.8 ± 12.1, respectively (P=0.001).

The mean time to onset of VTE after the earthquakes was significantly shorter in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—7.3 ± 5.3 days vs 20.1 ± 25.6 days (P=0.003).

And the incidence of PE was significantly higher in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—83% vs 33% (P=0.001).

“This is a dramatic example of the risks inherent in spending prolonged periods immobilized in a cramped position,” said Stanley Nattel, MD, editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

“It is an important reminder of a public health point and reinforces the need to get up and walk around regularly when on an airplane or when forced to stay in a car for a long time.”

New research has revealed a link between earthquake evacuation and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The study showed that people who spent the night in their cars after the Kumamoto earthquakes had an increased risk of VTE.

Researchers have therefore called for education about the risk of VTE among people who remain seated and immobile in vehicles for prolonged periods.

“Preventive awareness activities by professional medical teams, supported by education in the media about the risk of VTEs after spending the night in a vehicle, and raising awareness of evacuation centers could lead to a reduced number of victims of VTE,” said Seiji Hokimoto, MD, PhD, of Kumamoto University in Kumamoto, Japan.

Dr Hokimoto and colleagues made this point in a letter published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

The researchers studied the aftermath of the Kumamoto earthquakes that occurred in April 2016.

The team noted that a high number of aftershocks at night prompted many people to evacuate their homes. Although some individuals reached a public evacuation shelter, many were forced to stay in their vehicles overnight.

To assess the impact of remaining seated in cars for extended periods of time, the researchers gathered data from 21 local medical institutions.

They found that 51 patients were hospitalized for VTE after the earthquakes, including 35 who developed pulmonary embolism (PE).

Most of the patients who developed VTE had spent the night in a vehicle (82.4%, n=42).

The researchers found that VTE patients who spent the night in a vehicle were significantly younger than patients who did not, with mean ages of 64.6 ± 13.3 and 79.8 ± 12.1, respectively (P=0.001).

The mean time to onset of VTE after the earthquakes was significantly shorter in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—7.3 ± 5.3 days vs 20.1 ± 25.6 days (P=0.003).

And the incidence of PE was significantly higher in patients who spent the night in a vehicle—83% vs 33% (P=0.001).

“This is a dramatic example of the risks inherent in spending prolonged periods immobilized in a cramped position,” said Stanley Nattel, MD, editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

“It is an important reminder of a public health point and reinforces the need to get up and walk around regularly when on an airplane or when forced to stay in a car for a long time.”

Blood type linked to death risk after trauma

Having type O blood is associated with high death rates in severe trauma patients, according to a study published in Critical Care.

Researchers found that severe trauma patients with type O blood had a death rate of 28%, compared to a rate of 11% in patients with other blood types.

“Loss of blood is the leading cause of death in patients with severe trauma, but studies on the association between different blood types and the risk of trauma death have been scarce,” said study author Wataru Takayama, of Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital of Medicine in Japan.

“We wanted to test the hypothesis that trauma survival is affected by differences in blood types.”

To do this, the researchers evaluated the medical records of 901 patients with severe trauma who had been transported to either of 2 tertiary emergency critical care medical centers in Japan from 2013 to 2016.

Most patients had type O (n=284, 32%) or type A blood (n=285, 32%), followed by type B (n=209, 23%) and type AB (n=123, 13%).

The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with type O blood than in patients with the other blood types—28% and 11%, respectively (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis, mortality was significantly higher for patients with type O blood. The adjusted odds ratio was 2.86 (P<0.001).

Patients with type O blood have been shown to have lower levels of von Willebrand factor than patients with other blood types. The researchers suggested that a lower level of von Willebrand factor is a possible explanation for the higher death rate in trauma patients with blood type O.

“Our results also raise questions about how emergency transfusion of O type red blood cells to a severe trauma patient could affect homeostasis . . . and if this is different from other blood types,” Dr Takayama said.

“Further research is necessary to investigate the results of our study and develop the best treatment strategy for severe trauma patients.”

In particular, further research is needed to determine if the findings from this study apply to other ethnic groups, as all the patients in this study were Japanese.

In addition, the researchers didn’t evaluate the impact of the individual blood types A, AB, or B on severe trauma death rates. They only compared type O to non-O blood types, which may have diluted the effect of individual blood types on patient survival.

Having type O blood is associated with high death rates in severe trauma patients, according to a study published in Critical Care.

Researchers found that severe trauma patients with type O blood had a death rate of 28%, compared to a rate of 11% in patients with other blood types.

“Loss of blood is the leading cause of death in patients with severe trauma, but studies on the association between different blood types and the risk of trauma death have been scarce,” said study author Wataru Takayama, of Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital of Medicine in Japan.

“We wanted to test the hypothesis that trauma survival is affected by differences in blood types.”

To do this, the researchers evaluated the medical records of 901 patients with severe trauma who had been transported to either of 2 tertiary emergency critical care medical centers in Japan from 2013 to 2016.

Most patients had type O (n=284, 32%) or type A blood (n=285, 32%), followed by type B (n=209, 23%) and type AB (n=123, 13%).

The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with type O blood than in patients with the other blood types—28% and 11%, respectively (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis, mortality was significantly higher for patients with type O blood. The adjusted odds ratio was 2.86 (P<0.001).

Patients with type O blood have been shown to have lower levels of von Willebrand factor than patients with other blood types. The researchers suggested that a lower level of von Willebrand factor is a possible explanation for the higher death rate in trauma patients with blood type O.

“Our results also raise questions about how emergency transfusion of O type red blood cells to a severe trauma patient could affect homeostasis . . . and if this is different from other blood types,” Dr Takayama said.

“Further research is necessary to investigate the results of our study and develop the best treatment strategy for severe trauma patients.”

In particular, further research is needed to determine if the findings from this study apply to other ethnic groups, as all the patients in this study were Japanese.

In addition, the researchers didn’t evaluate the impact of the individual blood types A, AB, or B on severe trauma death rates. They only compared type O to non-O blood types, which may have diluted the effect of individual blood types on patient survival.

Having type O blood is associated with high death rates in severe trauma patients, according to a study published in Critical Care.

Researchers found that severe trauma patients with type O blood had a death rate of 28%, compared to a rate of 11% in patients with other blood types.

“Loss of blood is the leading cause of death in patients with severe trauma, but studies on the association between different blood types and the risk of trauma death have been scarce,” said study author Wataru Takayama, of Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital of Medicine in Japan.

“We wanted to test the hypothesis that trauma survival is affected by differences in blood types.”

To do this, the researchers evaluated the medical records of 901 patients with severe trauma who had been transported to either of 2 tertiary emergency critical care medical centers in Japan from 2013 to 2016.

Most patients had type O (n=284, 32%) or type A blood (n=285, 32%), followed by type B (n=209, 23%) and type AB (n=123, 13%).

The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with type O blood than in patients with the other blood types—28% and 11%, respectively (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis, mortality was significantly higher for patients with type O blood. The adjusted odds ratio was 2.86 (P<0.001).

Patients with type O blood have been shown to have lower levels of von Willebrand factor than patients with other blood types. The researchers suggested that a lower level of von Willebrand factor is a possible explanation for the higher death rate in trauma patients with blood type O.

“Our results also raise questions about how emergency transfusion of O type red blood cells to a severe trauma patient could affect homeostasis . . . and if this is different from other blood types,” Dr Takayama said.

“Further research is necessary to investigate the results of our study and develop the best treatment strategy for severe trauma patients.”

In particular, further research is needed to determine if the findings from this study apply to other ethnic groups, as all the patients in this study were Japanese.

In addition, the researchers didn’t evaluate the impact of the individual blood types A, AB, or B on severe trauma death rates. They only compared type O to non-O blood types, which may have diluted the effect of individual blood types on patient survival.

Interferon-gamma release assay trumps tuberculin skin test in school-aged children

The interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) was significantly more sensitive than a tuberculin skin test as an adjunct tuberculosis diagnosis of children aged 5 years and older, according to data from a population-based study of 778 cases.

IGRAs have shown greater specificity than tuberculin skin tests (TSTs), but data on their sensitivity to TB in children are limited, wrote Alexander W. Kay, MD, of the California Department of Public Health and his colleagues in a study published in Pediatrics.

Children younger than 1 year of age and those with CNS disease were significantly more likely to have indeterminate IGRA results, the researchers noted.

The study results were limited by the use of mainly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based IGRA, which limited the data on enzyme-linked immunospot tests, the researchers said. The findings also were limited by the small number of children younger than 5 years.

However, the study is the largest North American analysis of IGRA in children, and based on the findings, “we argue that an IGRA should be considered the test of choice when evaluating children 5-18 years old for TB disease in high-resource, low-TB burden settings,” Dr. Kay and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coauthor Shamim Islam, MD, disclosed financial support from Qiagen, maker of the QuantiFERON test. Dr. Kay and the other investigators had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kay A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3918.

The interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) was significantly more sensitive than a tuberculin skin test as an adjunct tuberculosis diagnosis of children aged 5 years and older, according to data from a population-based study of 778 cases.

IGRAs have shown greater specificity than tuberculin skin tests (TSTs), but data on their sensitivity to TB in children are limited, wrote Alexander W. Kay, MD, of the California Department of Public Health and his colleagues in a study published in Pediatrics.

Children younger than 1 year of age and those with CNS disease were significantly more likely to have indeterminate IGRA results, the researchers noted.

The study results were limited by the use of mainly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based IGRA, which limited the data on enzyme-linked immunospot tests, the researchers said. The findings also were limited by the small number of children younger than 5 years.

However, the study is the largest North American analysis of IGRA in children, and based on the findings, “we argue that an IGRA should be considered the test of choice when evaluating children 5-18 years old for TB disease in high-resource, low-TB burden settings,” Dr. Kay and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coauthor Shamim Islam, MD, disclosed financial support from Qiagen, maker of the QuantiFERON test. Dr. Kay and the other investigators had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kay A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3918.

The interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) was significantly more sensitive than a tuberculin skin test as an adjunct tuberculosis diagnosis of children aged 5 years and older, according to data from a population-based study of 778 cases.

IGRAs have shown greater specificity than tuberculin skin tests (TSTs), but data on their sensitivity to TB in children are limited, wrote Alexander W. Kay, MD, of the California Department of Public Health and his colleagues in a study published in Pediatrics.

Children younger than 1 year of age and those with CNS disease were significantly more likely to have indeterminate IGRA results, the researchers noted.

The study results were limited by the use of mainly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based IGRA, which limited the data on enzyme-linked immunospot tests, the researchers said. The findings also were limited by the small number of children younger than 5 years.

However, the study is the largest North American analysis of IGRA in children, and based on the findings, “we argue that an IGRA should be considered the test of choice when evaluating children 5-18 years old for TB disease in high-resource, low-TB burden settings,” Dr. Kay and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coauthor Shamim Islam, MD, disclosed financial support from Qiagen, maker of the QuantiFERON test. Dr. Kay and the other investigators had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kay A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3918.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Sensitivity was 96% for IGRA versus 83% for TST among children aged 5-18 years.

Study details: The data come from TB patients aged 18 years and younger enrolled in the California TB registry during 2010-2015.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coauthor Shamim Islam, MD, disclosed financial support from Qiagen, maker of the QuantiFERON test; Dr. Kay and the other investigators had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kay A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 4. doi: 10. 1542/ peds. 2017- 3918.

Abstract: Risk of colorectal cancer after a negative colonoscopy in low-to-moderate risk individuals: impact of a 10-year colonoscopy

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Murthy, S.K., et al, Endoscopy 49(12):1228, December 2017

BACKGROUND: Repeat colonoscopy is recommended ten years after a negative screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) in low-risk persons, but the real-world benefit of this recommendation is uncertain.

METHODS: These Canadian authors, coordinated at the University of Ottawa, performed a retrospective cohort study to determine the utility of ten-year repeat screening colonoscopy using population-level data from Ontario adults aged 50-74 years with a low to moderate risk of CRC (no relevant gastrointestinal disorders) who had a negative colonoscopy in 1996-2001 and a repeat negative screening within eight to twelve years, excluding those with intervening events (CRC detection, colectomy, or lower endoscopy). The primary outcome was early incident CRC in the group having repeat screening within twelve years compared with an unexposed control group matched by age, sex and year of baseline colonoscopy.

RESULTS: A total of 13,350 matched pairs (median age 68 years; 56% female) were analyzed for CRC incidence over a median follow-up of 4.5 years. The cumulative probability of CRC over three, five and eight years following a negative baseline colonoscopy was 0.16%, 0.30%, and 0.54%, respectively. Among patients having repeat colonoscopy, 46 developed CRC, compared with 52 in unexposed controls, for cumulative probabilities of 0.70% and 0.77%, respectively, and a hazard ratio of 0.91 (95% CI 0.68-1.22) after adjusting for competing risks and comorbidity burden. CRC-related mortality was also similar between groups (8 and 9 patients). Short follow-up was a study limitation.

CONCLUSIONS: Repeat colonoscopy within eight to twelve years of a negative screen was not associated with subsequent CRC incidence, which raises questions about the utility of ten-year repeat screening. 21 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Murthy, S.K., et al, Endoscopy 49(12):1228, December 2017

BACKGROUND: Repeat colonoscopy is recommended ten years after a negative screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) in low-risk persons, but the real-world benefit of this recommendation is uncertain.

METHODS: These Canadian authors, coordinated at the University of Ottawa, performed a retrospective cohort study to determine the utility of ten-year repeat screening colonoscopy using population-level data from Ontario adults aged 50-74 years with a low to moderate risk of CRC (no relevant gastrointestinal disorders) who had a negative colonoscopy in 1996-2001 and a repeat negative screening within eight to twelve years, excluding those with intervening events (CRC detection, colectomy, or lower endoscopy). The primary outcome was early incident CRC in the group having repeat screening within twelve years compared with an unexposed control group matched by age, sex and year of baseline colonoscopy.

RESULTS: A total of 13,350 matched pairs (median age 68 years; 56% female) were analyzed for CRC incidence over a median follow-up of 4.5 years. The cumulative probability of CRC over three, five and eight years following a negative baseline colonoscopy was 0.16%, 0.30%, and 0.54%, respectively. Among patients having repeat colonoscopy, 46 developed CRC, compared with 52 in unexposed controls, for cumulative probabilities of 0.70% and 0.77%, respectively, and a hazard ratio of 0.91 (95% CI 0.68-1.22) after adjusting for competing risks and comorbidity burden. CRC-related mortality was also similar between groups (8 and 9 patients). Short follow-up was a study limitation.

CONCLUSIONS: Repeat colonoscopy within eight to twelve years of a negative screen was not associated with subsequent CRC incidence, which raises questions about the utility of ten-year repeat screening. 21 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Murthy, S.K., et al, Endoscopy 49(12):1228, December 2017

BACKGROUND: Repeat colonoscopy is recommended ten years after a negative screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) in low-risk persons, but the real-world benefit of this recommendation is uncertain.

METHODS: These Canadian authors, coordinated at the University of Ottawa, performed a retrospective cohort study to determine the utility of ten-year repeat screening colonoscopy using population-level data from Ontario adults aged 50-74 years with a low to moderate risk of CRC (no relevant gastrointestinal disorders) who had a negative colonoscopy in 1996-2001 and a repeat negative screening within eight to twelve years, excluding those with intervening events (CRC detection, colectomy, or lower endoscopy). The primary outcome was early incident CRC in the group having repeat screening within twelve years compared with an unexposed control group matched by age, sex and year of baseline colonoscopy.

RESULTS: A total of 13,350 matched pairs (median age 68 years; 56% female) were analyzed for CRC incidence over a median follow-up of 4.5 years. The cumulative probability of CRC over three, five and eight years following a negative baseline colonoscopy was 0.16%, 0.30%, and 0.54%, respectively. Among patients having repeat colonoscopy, 46 developed CRC, compared with 52 in unexposed controls, for cumulative probabilities of 0.70% and 0.77%, respectively, and a hazard ratio of 0.91 (95% CI 0.68-1.22) after adjusting for competing risks and comorbidity burden. CRC-related mortality was also similar between groups (8 and 9 patients). Short follow-up was a study limitation.

CONCLUSIONS: Repeat colonoscopy within eight to twelve years of a negative screen was not associated with subsequent CRC incidence, which raises questions about the utility of ten-year repeat screening. 21 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

Learn more about the Primary Care Medical Abstracts and podcasts, for which you can earn up to 9 CME credits per month.

Copyright © The Center for Medical Education

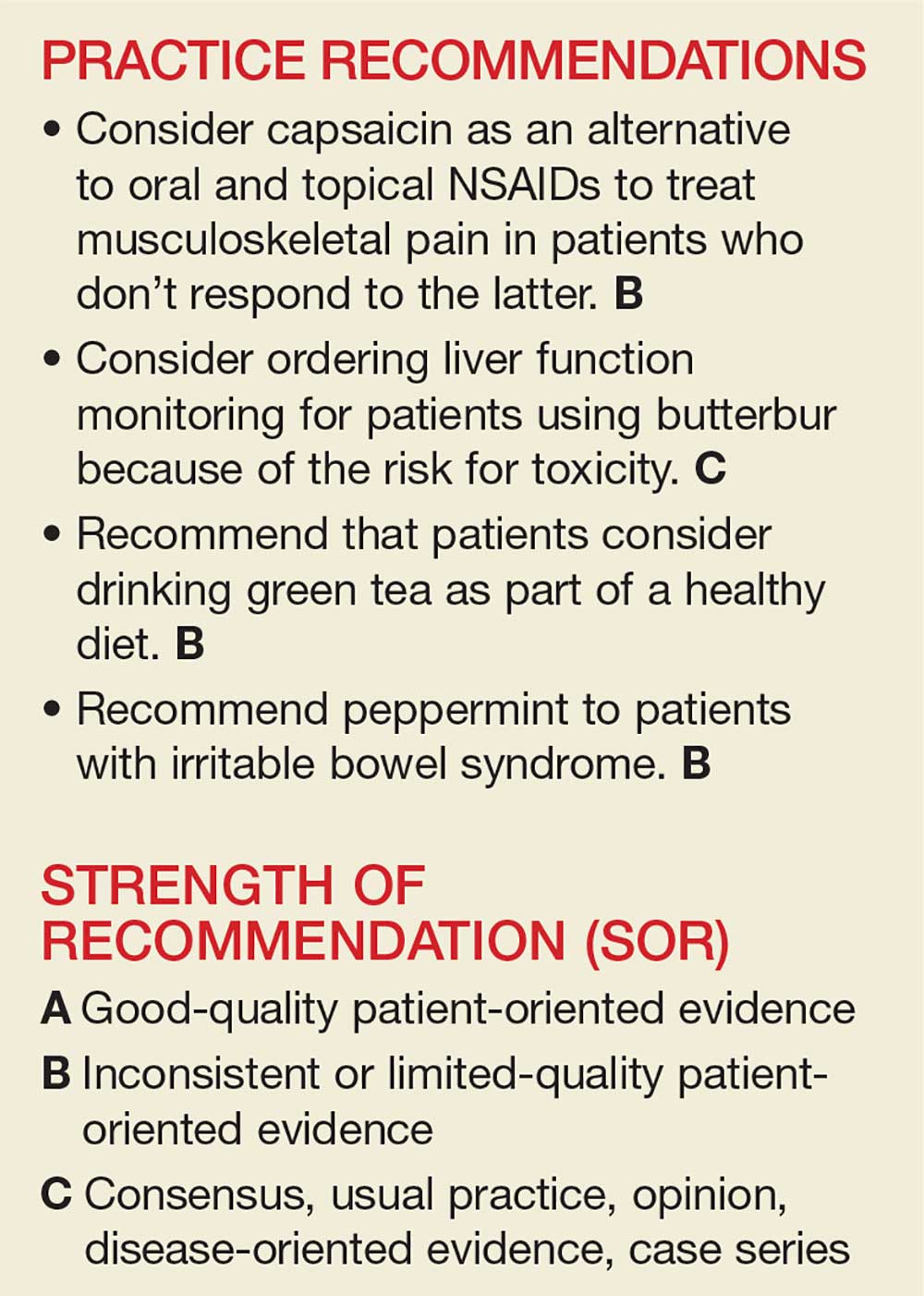

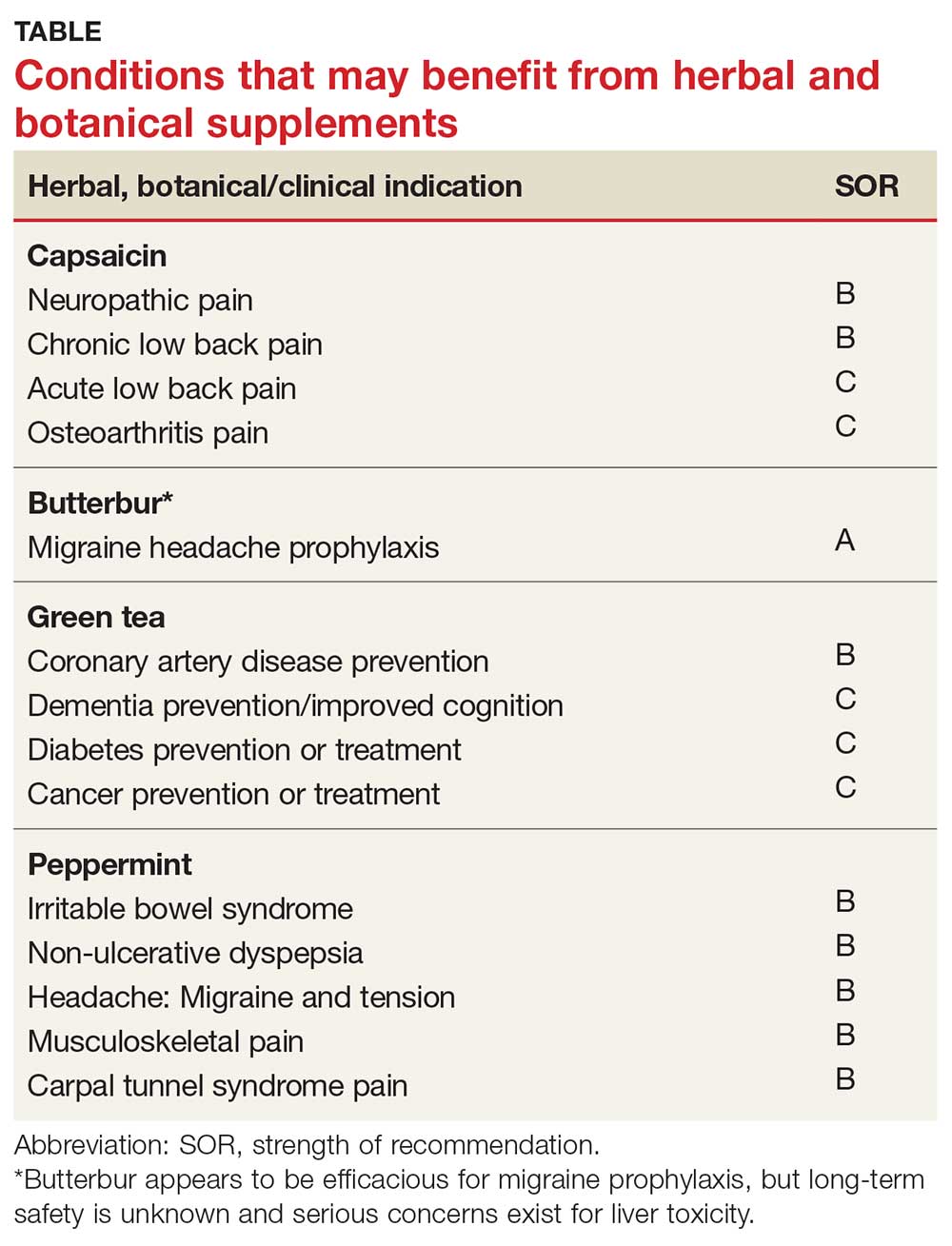

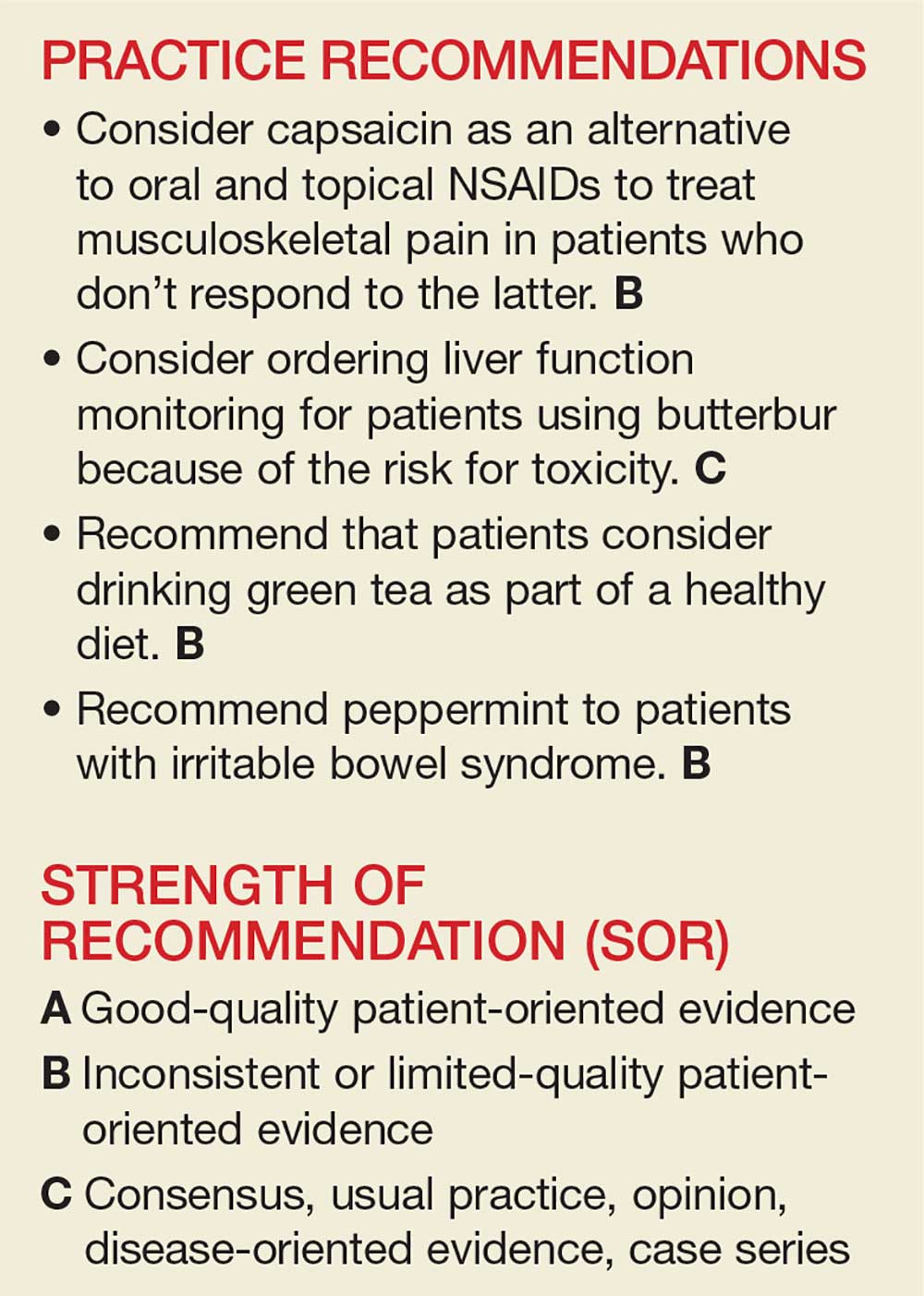

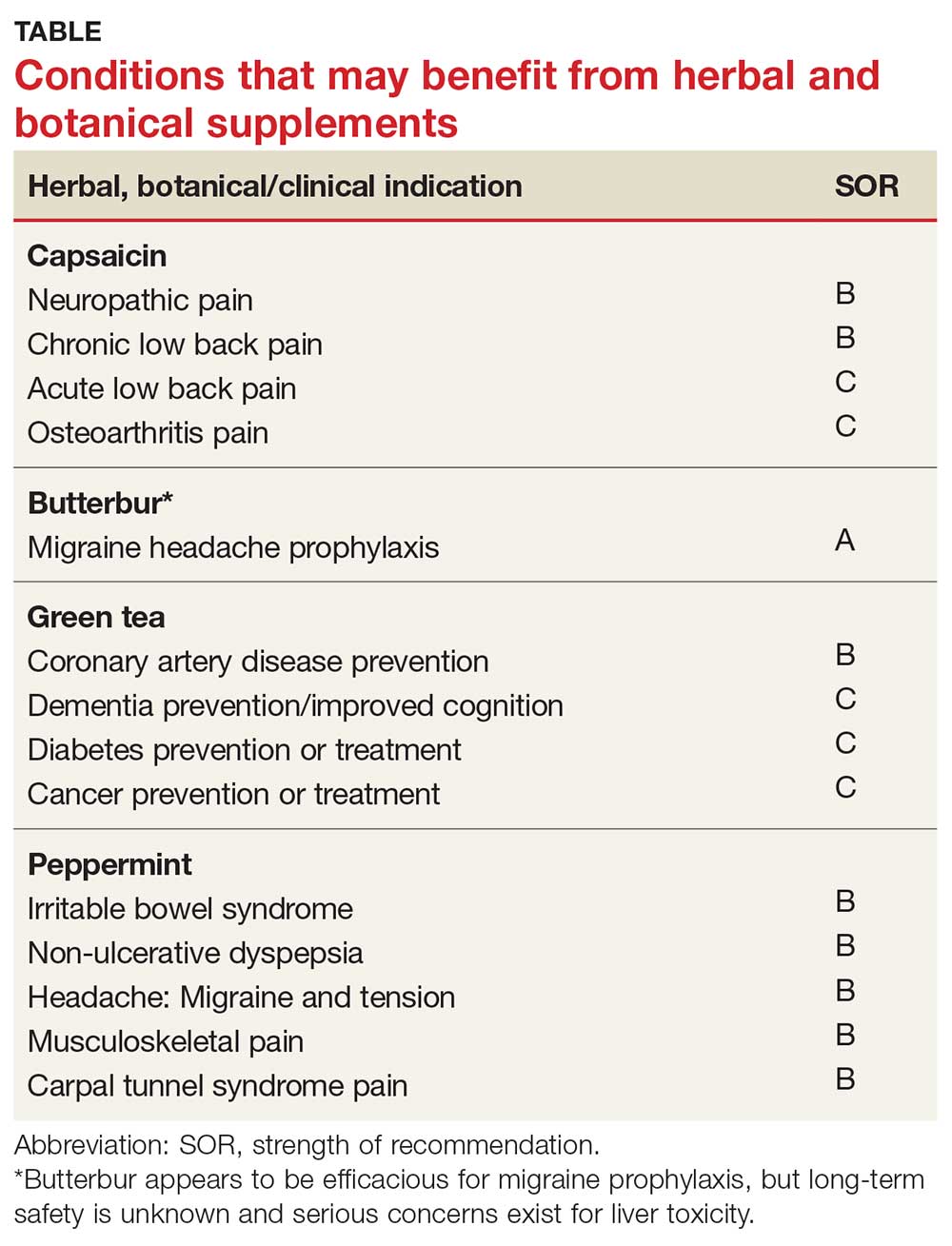

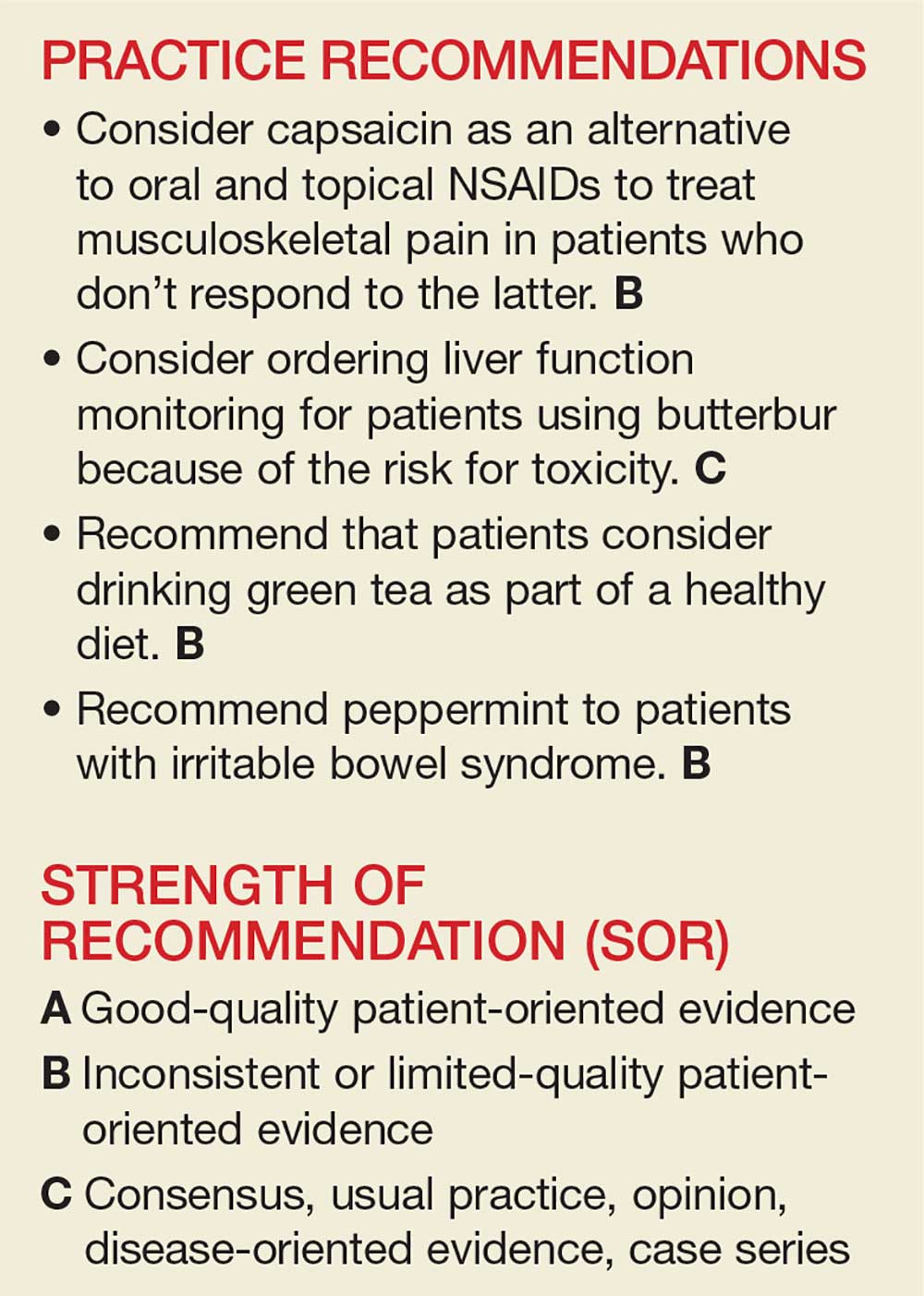

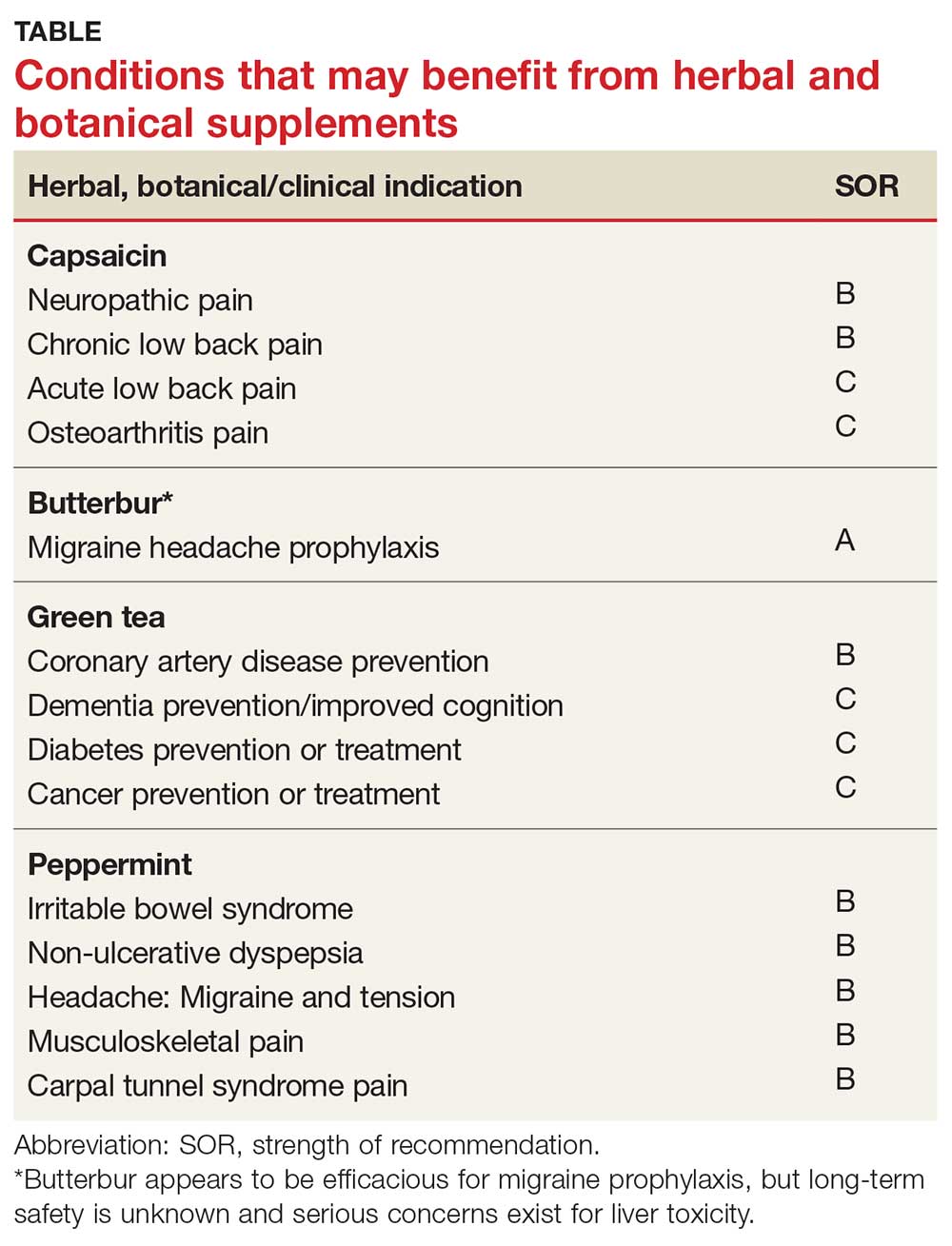

The Evidence for Herbal and Botanical Remedies

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, a division of the National Institutes of Medicine, estimates that 38% of American adults use complementary and alternative medicine (including 17.7% who say they use “natural products”).1 Despite the popularity of these products, many providers remain skeptical—and for good reason. Enthusiasts may offer dramatic anecdotes to “prove” their supplements’ worth, but little scientific support is available for most herbal remedies. There are, however, exceptions—capsaicin, butterbur, green tea, and peppermint—as this review of the medical literature reveals.

Worth noting as you consider this—or any—review of herbals is that while there is limited scientific evidence to establish the safety and efficacy of most herbal products, they are nonetheless freely sold without FDA approval because, under current regulations, they are considered dietary supplements. That legal designation means companies can manufacture, sell, and market herbs without first demonstrating safety and efficacy, as is required for pharmaceutical drugs. Because herbal medications do not require the same testing through the large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) required for pharmaceuticals, evidence is often based on smaller RCTs and other studies of lower overall quality. Despite these limitations, we believe it’s worth keeping an open mind about the value of evidence-based herbal and botanical treatments.

CAPSAICIN

Capsaicin, an active compound in chili peppers, provokes a burning sensation but also has a long history of use in pain treatment.2 Qutenza, an FDA-approved, chemically synthesized 8% capsaicin patch, is identical to the naturally occurring molecule.2 Topical capsaicin exerts its therapeutic effect by rapidly depleting substance P, thus reducing the transmission of pain from C fibers to higher neurologic centers in the area of administration.3

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown capsaicin is effective for various painful conditions, including peripheral diabetic neuropathy, osteoarthritis (OA), low back pain (LBP), and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Peripheral neuropathy. A Cochrane review of six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of at least six weeks’ duration using topical 8% capsaicin to treat PHN and HIV-associated neuropathy concluded that high-concentration topical capsaicin provided more relief in patients with high pain levels than control patients who received a subtherapeutic (0.04%) capsaicin cream. Number-needed-to-treat values were between 8 and 12. Local adverse events were common, but not consistently reported enough to calculate a number needed to harm.4

OA. In randomized trials, capsaicin provided mild-to-moderate efficacy for patients with hand and knee OA, when compared with placebo.5-7 A systematic review of capsaicin for all osteoarthritic conditions noted that there was consistent evidence that capsaicin gel was effective for OA.8 However, a 2013 Cochrane review of only knee OA noted that capsicum extract did not provide significant clinical improvement for pain or function and resulted in a significant number of adverse events.9

LBP. Based on a 2014 Cochrane review of three trials (755 subjects) of moderate quality, capsicum frutescens cream or plaster appeared more efficacious than placebo in people with chronic LBP.10 Based on current (low-quality) evidence in one trial, however, it’s not clear whether topical capsicum cream is more beneficial for acute LBP than placebo.10

PHN. Topical capsaicin is an FDA-approved treatment for PHN. A review and cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrated that 8% capsaicin had significantly higher effectiveness rates than the oral agents (tricyclic antidepressants, duloxetine, gabapentin, pregabalin) used to treat PHN.11 The cost of the capsaicin patch was similar to a topical lidocaine patch and oral products for PHN.11 A meta-analysis of seven RCTs indicated that 8% topical capsaicin was superior to the low-dose capsaicin patch for relieving pain associated with PHN.12

Continue to: Adverse effects

Adverse effects

Very few toxic effects have been reported during a half-century of capsaicin use. Those that have been reported are mainly limited to mild local reactions.2 The most common adverse effect of topical capsaicin is local irritation (burning, stinging, and erythema), which was reported in approximately 40% of patients.6 Nevertheless, more than 90% of the subjects in clinical studies were able to complete the studies, and pain rapidly resolved after patch removal.2 Washing with soap and water may help prevent the compound from spreading to other parts of the body unintentionally.

The safety of the patch has been demonstrated with repeated dosing every three months for up to one year. However, the long-term risks of chronic capsaicin use and its effect on epidermal innervation are uncertain.5

The bottom line

Capsaicin appears to be an effective treatment for neuropathy and chronic LBP. It is FDA approved for the treatment of PHN. It may also benefit patients with OA and acute LBP. Serious adverse effects are uncommon with topical use. Common adverse effects include burning pain and irritation in the area of application, which can be intense and cause discontinuation.2

Continue to: BUTTERBUR

BUTTERBUR

Petasites hybridus, also known as butterbur, is a member of the daisy family, Asteraceae, and is a perennial plant found throughout Europe and Asia.13 It was used as a remedy for ulcers, wounds, and inflammation in ancient Greece. Its calcium channel–blocking effects may counteract vasoconstriction and play a role in preventing hyperexcitation of neurons.14 Sesquiterpenes, the pharmacologically active compounds in butterbur, have strong anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory effects through lipoxygenase and leukotriene inhibition.14

Migraine headache. Butterbur appears to be effective in migraine prophylaxis. Several studies have shown butterbur to significantly reduce the number of migraine attacks per month when compared with placebo. In a small, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study on the efficacy and tolerability of a special butterbur root extract (Petadolex) for the prevention of migraine, response rate was 45% in the butterbur group vs 15% in the placebo group. Butterbur was well tolerated.15 Similar results were found in another RCT in which butterbur 75 mg bid significantly reduced migraine frequency by 48%, compared with 26% for the placebo group.16 Butterbur was well tolerated in this study, too, and no serious adverse events occurred. Findings suggest that 75 mg bid may be a good option for migraine prevention, given the agent’s safety profile.

Petadolex may also be a good option in pediatric migraine. A 2005 study in children and adolescents found that 77% of patients experienced a reduction in attacks by at least 50% with butterbur. Patients were treated with 50 mg to 150 mg over four months.17

In their 2012 guidelines for migraine prevention, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and American Headache Society gave butterbur a Level A recommendation, concluding that butterbur should be offered to patients with migraine to reduce the frequency and severity of migraine attacks.18 However, the AAN changed its position in 2015, redacting the recommendation due to serious safety concerns.19

Allergic rhinitis. Although the data are not convincing, some studies have shown that butterbur may be beneficial for the treatment of allergic rhinitis.20,21

Continue to: Adverse effects

Adverse effects

While the butterbur plant itself contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA), which are hepatotoxic and carcinogenic, extracts of butterbur root that are almost completely free from these alkaloids are available. Patients who choose to use butterbur should be advised to use only products that are certified and labeled PA free.

Petadolex, the medication used in migraine studies, was initially approved by the German health regulatory authority, but approval was later withdrawn due to concerns about liver toxicity.22 In 2012, the United Kingdom’s Medicines and Health Care Products Regulatory Agency withdrew all butterbur products from the market due to associated cases of liver toxicity.22 Butterbur products are still available in the US market, and the risks and benefits should be discussed with all patients considering this treatment. Liver function monitoring is recommended for all patients using butterbur.22

The herb can also cause dyspepsia, headache, itchy eyes, gastrointestinal symptoms, asthma, fatigue, and drowsiness. Additionally, people who are allergic to ragweed and daisies may have allergic reactions to butterbur. Eructation (belching) occurred in 7% of patients in a pediatric study.17

The bottom line

Butterbur appears to be efficacious for migraine prophylaxis, but long-term safety is unknown and serious concerns exist for liver toxicity.

Continue to: GREEN TEA

GREEN TEA

Most tea leaves come from the Camellia sinensis bush, but green and black tea are processed differently to produce different end products.23 It is estimated that green tea accounts for approximately a quarter of all tea consumption and is most commonly consumed in Asian countries.23 The health-promoting effects of green tea are mainly attributed to its polyphenol content.24 Of the many types of tea, green tea has the highest concentration of polyphenols, including catechins, which are powerful antioxidants.23,24 Green tea has been used in traditional Chinese and Indian medicine to control bleeding, improve digestion, and promote overall health.23

Dementia. Green tea polyphenols may enhance cognition and may protect against the development of dementia. In-vitro studies have shown that green tea reduces hydrogen peroxide and ß-amyloid peptides, which are significant in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.25 A 12-subject double-blind study found green tea increased working memory and had an impact on frontoparietal brain connections.26 Furthermore, a cohort study with 13,645 Japanese participants over a five-year period found that frequent green tea consumption (> 5 cups per day) was associated with a lower risk for dementia.27 Additional studies are needed, but green tea may be useful in the treatment or prevention of dementia in the future.

Coronary artery disease. In one study, green tea plasma and urinary concentrations were associated with plasma biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.28 In one review, the consumption of green tea was associated with a statistically significant reduction in LDL cholesterol.29 Furthermore, a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies concluded that increased tea consumption (of any type) is associated with a reduced risk for coronary heart disease, cardiac death, stroke, and total mortality.30

Cancer. Many studies have shown that green tea may reduce the risk for cancer, although epidemiologic evidence is inconsistent. Studies have shown that cancer rates tend to be lower in those who consume higher levels of green tea.31,32 Whether this can be attributed solely to green tea remains debatable. Several other studies have shown that polyphenols in green tea can inhibit the growth of cancer cells, but the exact mechanism by which tea interacts with cancerous cells is unknown.23

Several population-based studies have been performed, mostly in Japan, which showed green tea consumption reduced the risk for cancer. Fewer prostate cancer cases have been reported in men who consume green tea.33 While studies have been performed to determine whether green tea has effects on pancreatic, esophageal, ovarian, breast, bladder, and colorectal cancer, the evidence remains inadequate.32

Diabetes. Green tea has been shown in several studies to have a beneficial effect on diabetes. A retrospective Japanese cohort study showed that those who consumed green tea were one-third less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.34 A 10-year study from Taiwan found lower body fat and smaller waist circumference in those who consumed green tea regularly.35 A 2014 meta-analysis and systematic review of tea (any type) consumption and the risk for diabetes concluded that three or more cups of tea per day was associated with a lower risk for diabetes.36 Another meta-analysis of 17 RCTs focused on green tea concluded that green tea improves glucose control and A1C values.37

Continue to: Adverse effects

Adverse effects

There have been concerns about potential hepatotoxicity induced by green tea intake.38 However, a systematic review of 34 RCTs on liver-related adverse events from green tea showed only a slight elevation in liver function tests; no serious liver-related adverse events were reported.38 This review suggested that liver-related adverse events after intake of green tea extracts are rare.38

Consuming green tea in the diet may lower the risk for adverse effects since the concentration consumed is generally much lower than that found in extracts.

Contraindications to drinking green tea are few. Individuals with caffeine sensitivities could experience insomnia, anxiety, irritability, or upset stomach. Additionally, patients who are taking anticoagulation drugs, such as warfarin, should avoid green tea due to its vitamin K content, which can counter the effects of warfarin. Pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with heart problems or high blood pressure, kidney or liver problems, stomach ulcers, or anxiety disorders should use caution with green tea consumption.

The bottom line

Green tea consumption in the diet appears to be safe and may have beneficial effects on weight, dementia, and risk for diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Patients may want to consider drinking green tea as part of a healthy diet, in combination with exercise.

Continue to: PEPPERMINT

PEPPERMINT

Mentha piperita, also known as peppermint, is a hybrid between water mint and spearmint. It is found throughout Europe and North America and is commonly used in tea and toothpaste and as a flavoring for gum. Menthol and methyl salicylate are the main active ingredients in peppermint, and peppermint has calcium channel–blocker effects.39 Menthol has been shown to help regulate cold and pain sensation through the TRPM8 receptor.40 The peppermint herb is used both orally and topically, and has been studied in the treatment of multiple conditions.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It appears that peppermint inhibits spontaneous peristaltic activity, which reduces gastric emptying, decreases basal tone in the gastrointestinal tract, and slows down peristalsis in the gut.39

The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines currently note that there is moderate-quality evidence for peppermint oil in the treatment of IBS.41 A Cochrane review concluded that peppermint appears to be beneficial for IBS-related symptoms and pain.42 In a systematic review of nine studies from 2014, peppermint oil was found to be more effective than placebo for IBS symptoms such as pain, bloating, gas, and diarrhea.43 The review also indicated that peppermint oil is safe, with heartburn being the most common complaint.43 A 2016 study also found that triple-coated microspheres containing peppermint oil reduced the frequency and intensity of IBS symptoms.44

Non-ulcer dyspepsia. In combination with caraway oil, peppermint oil can be used to reduce symptoms of non-ulcer dyspepsia.45,46 A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study found that 43.3% of subjects improved with a peppermint-caraway oil combination after eight weeks, compared with 3.5% receiving placebo.46

Barium enema–related colonic spasm. Peppermint can relax the lower esophageal sphincter, and it has been shown to be useful as an antispasmodic agent for barium enema–related colonic spasm.47,48

Itching/skin irritation. Peppermint, when applied topically, has been used to calm pruritus and relieve irritation and inflammation. It has a soothing and cooling effect on the skin. At least one study found it to be effective in the treatment of pruritus gravidarum, although the study population consisted of only 96 subjects.49

Migraine headache. Initial small trials suggest that menthol is likely beneficial for migraine headaches. A pilot trial of 25 patients treated with topical menthol 6% gel for an acute migraine attack showed a significant improvement in headache intensity two hours after gel application.50 In a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of 35 patients, a menthol 10% solution was shown to be more efficacious as abortive treatment of migraine headaches than placebo.51

Tension headache. In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study, topical peppermint oil showed a significant clinical reduction in tension headache pain.52 Another small, randomized, double-blind trial showed that tiger balm (containing menthol as the main ingredient) also produced statistically significant improvement in tension headache discomfort compared with placebo.53

Continue to: Musculoskeletal pain

Musculoskeletal pain. A small study comparing topical menthol to ice for muscle soreness noted decreased perceived discomfort with menthol.54 Menthol has also been shown to reduce pain in patients with knee OA.55

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). A triple-blind RCT concluded that topical menthol acutely reduced pain intensity in slaughterhouse workers with CTS, and it should be considered as an effective nonsystemic alternative to regular analgesics in the workplace management of chronic and neuropathic pain.56

Adverse effects

Peppermint appears to be safe for most adults when used in small doses, and serious adverse effects are rare.43,57 While peppermint tea appears to be safe in moderate-to-large amounts, people allergic to plants in the peppermint family (eg, mint, thyme, sage, rosemary, marjoram, basil, lavender) may experience allergic reactions with swelling, wheals, or erythema. Peppermint may also cause heartburn due to relaxation of the cardiac sphincter.

Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, flushing, and headache.58 The herb may also be both hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic at extremely high doses.59 Other considerations for women are that it can trigger menstruation and should be avoided during pregnancy. Due to uncertain efficacy in this population, peppermint oil should not be used on the face of infants, young children, or pregnant women.58,59

The bottom line

Peppermint appears to be safe and well tolerated. It is useful in alleviating IBS symptoms and may be effective in the treatment of non-ulcerative dyspepsia, musculoskeletal pain, headache, and CTS.54,55

1. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/2007/camsurvey_fs1.htm. Accessed April 19, 2018.

2. Wallace M, Pappagallo M. Qutenza: a capsaicin 8% patch for the management of postherpetic neuralgia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:15-27.

3. Rains C, Bryson HM. Topical capsaicin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential in post-herpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy and osteoarthritis. Drugs Aging. 1995;7:317-328.

4. Derry S, Sven-Rice A, Cole P, et al. Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD007393.

5. Mason L, Moore RA, Derry S, et al. Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328:991.

6. Deal CL, Schnitzer TJ, Lipstein E, et al. Treatment of arthritis with topical capsaicin: a double-blind trial. Clin Ther. 1991; 13:383.

7. McCarthy GM, McCarty DJ. Effect of topical capsaicin in the therapy of painful osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:604.

8. De Silva V, El-Metwally A, Ernst E, et al; Arthritis Research UK Working Group on Complementary and Alternative Medicines. Evidence for the efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines in the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:911-920.

9. Cameron M, Chrubasik S. Topical herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5): CD010538.

10. Oltean H, Robbins C, van Tulder MW, et al. Herbal medicine for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12): CD004504.

11. Armstrong EP, Malone DC, McCarberg B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a new 8% capsaicin patch compared to existing therapies for postherpetic neuralgia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:939-950.

12. Mou J, Paillard F, Turnbull B, et al. Efficacy of Qutenza (capsaicin) 8% patch for neuropathic pain: a meta-analysis of the Qutenza Clinical Trials Database. Pain. 2013;154:1632-1639.

13. Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Alternative headache treatments: nutraceuticals, behavioral and physical treatments. Headache. 2011;51:469-483.

14. D’Andrea G, Cevoli S, Cologno D. Herbal therapy in migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(suppl 1):135-140.

15. Diener HC, Rahlfs VW, Danesch U. The first placebo-controlled trial of a special butterbur root extract for the prevention of migraine: reanalysis of efficacy criteria. Eur Neurol. 2004;51:89-97.