User login

MDedge Daily News: The human cost of depression’s wonder drug

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Does depression’s wonder drug have a long-term cost? CPAP compliance may prevent return trips to the hospital, stem cells deliver durable results in stroke, and short-term health plans may be poised for a comeback.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Does depression’s wonder drug have a long-term cost? CPAP compliance may prevent return trips to the hospital, stem cells deliver durable results in stroke, and short-term health plans may be poised for a comeback.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Does depression’s wonder drug have a long-term cost? CPAP compliance may prevent return trips to the hospital, stem cells deliver durable results in stroke, and short-term health plans may be poised for a comeback.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

‘Antagonistic’ Markers for Cancer Prognosis

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling is fundamental to DNA metabolism, and SMARCA4 (or BRG1) is the most frequently mutated chromatin remodeling ATPase in cancer.

SMARCA4 is often mutated or silenced in tumors, suggesting a role as tumor suppressor, say researchers from Universidad de Sevilla-Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Spain. However, they note, recent reports show SMARCA4 also is required for tumor cell growth. So they performed a meta-analysis using gene expression, prognosis, and clinicopathologic data to clarify the role of SMARCA4 in cancer.

The researchers concluded that expression of SMARCA4 and another ATPase, SMARCA2, have a “high prognostic value.” Although the SMARCA4 gene is mostly overexpressed in tumors, the researchers say, SMARCA2 is almost invariably downregulated.

The data demonstrate that levels of SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 expression correlate with opposite prognosis in several types of tumors. The SMARCA4 upregulation is associated with a poor prognosis for breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, liposarcoma, and uveal melanoma, for instance. High expression of SMARCA4 can be used as a prognosis marker for those types of tumors, the researchers say. Exactly how the outcomes are linked to SMARCA4 is not yet clear, but the researchers point to research that found SMARCA4 promotes breast cancer by reprogramming lipid synthesis and is required for maintaining repopulation of hematopoietic stem cells in leukemia. (SMARCA4 is highly expressed in stem cells.)

By contrast, high levels of SMARCA2 expression were associated with a good prognosis in breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, and liposarcoma.

The researchers say that SMARCA4 expression is mostly associated to cell types that constantly undergo proliferation or self-renewal and SMARCA2 is absent from stem cells and inversely correlated with proliferation in several types of cells, suggesting the “attractive possibility” that they contribute to a type of equilibrium in proliferating-undifferentiated vs quiescent-differentiated conditions. That “antagonistic” behavior, the researchers suggest, should be taken into account when designing specific drugs that target one but not the other ATPase.

Source:

Guerrero-Martínez JA, Reyes JC. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:2043.

doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20217-3.

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling is fundamental to DNA metabolism, and SMARCA4 (or BRG1) is the most frequently mutated chromatin remodeling ATPase in cancer.

SMARCA4 is often mutated or silenced in tumors, suggesting a role as tumor suppressor, say researchers from Universidad de Sevilla-Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Spain. However, they note, recent reports show SMARCA4 also is required for tumor cell growth. So they performed a meta-analysis using gene expression, prognosis, and clinicopathologic data to clarify the role of SMARCA4 in cancer.

The researchers concluded that expression of SMARCA4 and another ATPase, SMARCA2, have a “high prognostic value.” Although the SMARCA4 gene is mostly overexpressed in tumors, the researchers say, SMARCA2 is almost invariably downregulated.

The data demonstrate that levels of SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 expression correlate with opposite prognosis in several types of tumors. The SMARCA4 upregulation is associated with a poor prognosis for breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, liposarcoma, and uveal melanoma, for instance. High expression of SMARCA4 can be used as a prognosis marker for those types of tumors, the researchers say. Exactly how the outcomes are linked to SMARCA4 is not yet clear, but the researchers point to research that found SMARCA4 promotes breast cancer by reprogramming lipid synthesis and is required for maintaining repopulation of hematopoietic stem cells in leukemia. (SMARCA4 is highly expressed in stem cells.)

By contrast, high levels of SMARCA2 expression were associated with a good prognosis in breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, and liposarcoma.

The researchers say that SMARCA4 expression is mostly associated to cell types that constantly undergo proliferation or self-renewal and SMARCA2 is absent from stem cells and inversely correlated with proliferation in several types of cells, suggesting the “attractive possibility” that they contribute to a type of equilibrium in proliferating-undifferentiated vs quiescent-differentiated conditions. That “antagonistic” behavior, the researchers suggest, should be taken into account when designing specific drugs that target one but not the other ATPase.

Source:

Guerrero-Martínez JA, Reyes JC. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:2043.

doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20217-3.

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling is fundamental to DNA metabolism, and SMARCA4 (or BRG1) is the most frequently mutated chromatin remodeling ATPase in cancer.

SMARCA4 is often mutated or silenced in tumors, suggesting a role as tumor suppressor, say researchers from Universidad de Sevilla-Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Spain. However, they note, recent reports show SMARCA4 also is required for tumor cell growth. So they performed a meta-analysis using gene expression, prognosis, and clinicopathologic data to clarify the role of SMARCA4 in cancer.

The researchers concluded that expression of SMARCA4 and another ATPase, SMARCA2, have a “high prognostic value.” Although the SMARCA4 gene is mostly overexpressed in tumors, the researchers say, SMARCA2 is almost invariably downregulated.

The data demonstrate that levels of SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 expression correlate with opposite prognosis in several types of tumors. The SMARCA4 upregulation is associated with a poor prognosis for breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, liposarcoma, and uveal melanoma, for instance. High expression of SMARCA4 can be used as a prognosis marker for those types of tumors, the researchers say. Exactly how the outcomes are linked to SMARCA4 is not yet clear, but the researchers point to research that found SMARCA4 promotes breast cancer by reprogramming lipid synthesis and is required for maintaining repopulation of hematopoietic stem cells in leukemia. (SMARCA4 is highly expressed in stem cells.)

By contrast, high levels of SMARCA2 expression were associated with a good prognosis in breast and ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, and liposarcoma.

The researchers say that SMARCA4 expression is mostly associated to cell types that constantly undergo proliferation or self-renewal and SMARCA2 is absent from stem cells and inversely correlated with proliferation in several types of cells, suggesting the “attractive possibility” that they contribute to a type of equilibrium in proliferating-undifferentiated vs quiescent-differentiated conditions. That “antagonistic” behavior, the researchers suggest, should be taken into account when designing specific drugs that target one but not the other ATPase.

Source:

Guerrero-Martínez JA, Reyes JC. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:2043.

doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20217-3.

Shock Treatment When It’s Needed Most

When blood pressure drops dangerously low, organ failure and death are real possibilities. Most deaths from trauma-related shock happen within 24 hours. But not all critically ill hypotensive patients respond to available therapies. A newly approved injectable drug could be a lifesaver for those patients.

Giapreza (angiotensin II/La Jolla Pharmaceutical, San Diego, CA) injection for intravenous infusion has been approved to increase blood pressure in cases of septic or other distributive shock. In a clinical trial of 321 patients with shock and critically low blood pressure, significantly more responded to treatment with Giapreza, compared with placebo. Giapreza effectively raised blood pressure when added to conventional treatments.

Giapreza can cause dangerous blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis. The FDA advises prophylactic treatment for blood clots.

When blood pressure drops dangerously low, organ failure and death are real possibilities. Most deaths from trauma-related shock happen within 24 hours. But not all critically ill hypotensive patients respond to available therapies. A newly approved injectable drug could be a lifesaver for those patients.

Giapreza (angiotensin II/La Jolla Pharmaceutical, San Diego, CA) injection for intravenous infusion has been approved to increase blood pressure in cases of septic or other distributive shock. In a clinical trial of 321 patients with shock and critically low blood pressure, significantly more responded to treatment with Giapreza, compared with placebo. Giapreza effectively raised blood pressure when added to conventional treatments.

Giapreza can cause dangerous blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis. The FDA advises prophylactic treatment for blood clots.

When blood pressure drops dangerously low, organ failure and death are real possibilities. Most deaths from trauma-related shock happen within 24 hours. But not all critically ill hypotensive patients respond to available therapies. A newly approved injectable drug could be a lifesaver for those patients.

Giapreza (angiotensin II/La Jolla Pharmaceutical, San Diego, CA) injection for intravenous infusion has been approved to increase blood pressure in cases of septic or other distributive shock. In a clinical trial of 321 patients with shock and critically low blood pressure, significantly more responded to treatment with Giapreza, compared with placebo. Giapreza effectively raised blood pressure when added to conventional treatments.

Giapreza can cause dangerous blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis. The FDA advises prophylactic treatment for blood clots.

Exercise doesn’t offset VTE risk from TV viewing

Getting the recommended amount of physical activity does not eliminate the increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with frequent TV viewing, according to research published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis.

In a study of more than 15,000 Americans, people who reported watching TV “very often” had nearly twice the risk of VTE as people who said they “never or seldom” watched TV.

People who watched TV very often had an increased VTE risk even when researchers adjusted for physical activity levels, smoking status, body mass index, and other factors.

“These results suggest that even individuals who regularly engage in physical activity should not ignore the potential harms of prolonged sedentary behaviors such as TV viewing,” said study author Yasuhiko Kubota, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“Avoiding frequent TV viewing, increasing physical activity, and controlling body weight might be beneficial to prevent VTE.”

Kubota and his colleagues came to these conclusions after analyzing data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, an ongoing, population-based, prospective study conducted in the US.

The researchers evaluated 15,158 Americans who were 45 to 64 years of age when ARIC started in 1987.

Study subjects were initially asked about their health status, whether they exercised or smoked, and whether they were overweight or not. Over the years, ARIC team members have been in regular contact with subjects to ask about any hospital treatment they might have received.

When subjects were asked about their TV viewing habits, most said they watched TV “sometimes” (n=7094). Fewer subjects said they watched TV “often” (n=4023), “never or seldom” (n=2815), and “very often” (n=1226).

Results

Via hospital records and imaging tests, Kubota and his colleagues identified 691 cases of VTE in the study cohort.

In assessing the risk of VTE, the researchers compared the “never or seldom” TV viewing group to the other viewing groups.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, and race, “sometimes” viewers had a hazard ratio (HR) of VTE of 1.17, the “often” group had an HR of 1.31, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.88.

In a second model, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned factors as well as smoking status, leisure-time physical activity, eGFR, and prevalent cardiovascular disease.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.16, the “often” group had an HR of 1.26, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.71.

In a third model, Kubota and his colleagues adjusted for all of the aforementioned factors as well as body mass index.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.13, the “often” group had an HR of 1.20, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.53.

The researchers noted that subjects who met the American Heart Association’s recommended level of physical activity but watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 1.80. Subjects with a poor physical activity level who watched TV “very often” had an HR of 2.07.

Kubota and his colleagues also found that obese subjects had an increased risk of VTE, and TV viewing appeared to add to that risk.

Obese subjects who watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 3.70. For obese subjects who “never or seldom” watched TV, the HR was 1.90.

Getting the recommended amount of physical activity does not eliminate the increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with frequent TV viewing, according to research published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis.

In a study of more than 15,000 Americans, people who reported watching TV “very often” had nearly twice the risk of VTE as people who said they “never or seldom” watched TV.

People who watched TV very often had an increased VTE risk even when researchers adjusted for physical activity levels, smoking status, body mass index, and other factors.

“These results suggest that even individuals who regularly engage in physical activity should not ignore the potential harms of prolonged sedentary behaviors such as TV viewing,” said study author Yasuhiko Kubota, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“Avoiding frequent TV viewing, increasing physical activity, and controlling body weight might be beneficial to prevent VTE.”

Kubota and his colleagues came to these conclusions after analyzing data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, an ongoing, population-based, prospective study conducted in the US.

The researchers evaluated 15,158 Americans who were 45 to 64 years of age when ARIC started in 1987.

Study subjects were initially asked about their health status, whether they exercised or smoked, and whether they were overweight or not. Over the years, ARIC team members have been in regular contact with subjects to ask about any hospital treatment they might have received.

When subjects were asked about their TV viewing habits, most said they watched TV “sometimes” (n=7094). Fewer subjects said they watched TV “often” (n=4023), “never or seldom” (n=2815), and “very often” (n=1226).

Results

Via hospital records and imaging tests, Kubota and his colleagues identified 691 cases of VTE in the study cohort.

In assessing the risk of VTE, the researchers compared the “never or seldom” TV viewing group to the other viewing groups.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, and race, “sometimes” viewers had a hazard ratio (HR) of VTE of 1.17, the “often” group had an HR of 1.31, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.88.

In a second model, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned factors as well as smoking status, leisure-time physical activity, eGFR, and prevalent cardiovascular disease.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.16, the “often” group had an HR of 1.26, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.71.

In a third model, Kubota and his colleagues adjusted for all of the aforementioned factors as well as body mass index.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.13, the “often” group had an HR of 1.20, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.53.

The researchers noted that subjects who met the American Heart Association’s recommended level of physical activity but watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 1.80. Subjects with a poor physical activity level who watched TV “very often” had an HR of 2.07.

Kubota and his colleagues also found that obese subjects had an increased risk of VTE, and TV viewing appeared to add to that risk.

Obese subjects who watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 3.70. For obese subjects who “never or seldom” watched TV, the HR was 1.90.

Getting the recommended amount of physical activity does not eliminate the increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with frequent TV viewing, according to research published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis.

In a study of more than 15,000 Americans, people who reported watching TV “very often” had nearly twice the risk of VTE as people who said they “never or seldom” watched TV.

People who watched TV very often had an increased VTE risk even when researchers adjusted for physical activity levels, smoking status, body mass index, and other factors.

“These results suggest that even individuals who regularly engage in physical activity should not ignore the potential harms of prolonged sedentary behaviors such as TV viewing,” said study author Yasuhiko Kubota, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“Avoiding frequent TV viewing, increasing physical activity, and controlling body weight might be beneficial to prevent VTE.”

Kubota and his colleagues came to these conclusions after analyzing data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, an ongoing, population-based, prospective study conducted in the US.

The researchers evaluated 15,158 Americans who were 45 to 64 years of age when ARIC started in 1987.

Study subjects were initially asked about their health status, whether they exercised or smoked, and whether they were overweight or not. Over the years, ARIC team members have been in regular contact with subjects to ask about any hospital treatment they might have received.

When subjects were asked about their TV viewing habits, most said they watched TV “sometimes” (n=7094). Fewer subjects said they watched TV “often” (n=4023), “never or seldom” (n=2815), and “very often” (n=1226).

Results

Via hospital records and imaging tests, Kubota and his colleagues identified 691 cases of VTE in the study cohort.

In assessing the risk of VTE, the researchers compared the “never or seldom” TV viewing group to the other viewing groups.

In a model adjusted for age, sex, and race, “sometimes” viewers had a hazard ratio (HR) of VTE of 1.17, the “often” group had an HR of 1.31, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.88.

In a second model, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned factors as well as smoking status, leisure-time physical activity, eGFR, and prevalent cardiovascular disease.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.16, the “often” group had an HR of 1.26, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.71.

In a third model, Kubota and his colleagues adjusted for all of the aforementioned factors as well as body mass index.

In this model, “sometimes” viewers had an HR of VTE of 1.13, the “often” group had an HR of 1.20, and the “very often” group had an HR of 1.53.

The researchers noted that subjects who met the American Heart Association’s recommended level of physical activity but watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 1.80. Subjects with a poor physical activity level who watched TV “very often” had an HR of 2.07.

Kubota and his colleagues also found that obese subjects had an increased risk of VTE, and TV viewing appeared to add to that risk.

Obese subjects who watched TV “very often” had an HR of VTE of 3.70. For obese subjects who “never or seldom” watched TV, the HR was 1.90.

Bleeding lesion on nose

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Gene therapy for hemophilia A gets fast-track review

The investigational gene therapy SPK-8011 for the treatment of hemophilia A is getting an accelerated review at the Food and Drug Administration, according to Spark Therapeutics.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to the gene therapy product in February and orphan drug status in January.

The investigational gene therapy SPK-8011 for the treatment of hemophilia A is getting an accelerated review at the Food and Drug Administration, according to Spark Therapeutics.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to the gene therapy product in February and orphan drug status in January.

The investigational gene therapy SPK-8011 for the treatment of hemophilia A is getting an accelerated review at the Food and Drug Administration, according to Spark Therapeutics.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to the gene therapy product in February and orphan drug status in January.

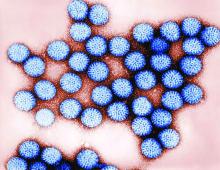

Newborn oral rotavirus vaccine held effective

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

A new oral rotavirus vaccine administered within the first few days of life appears effective against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in newborns, a study has found.

Julie E. Bines, MD, from the RV3 Rotavirus Vaccine Program at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, and her coauthors reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns in Indonesia. Participants were randomized to three doses of oral human neonatal rotavirus vaccine either on a neonatal schedule (0-5 days, 8-10 weeks, and 14-16 weeks of age) or an infant schedule (8-10 weeks, 14-16 weeks, and 18-20 weeks of age), or the equivalent schedules of placebo.

That efficacy was 77% in those who received the doses on the infant schedule.

Overall, severe rotavirus gastroenteritis was reported in 5.6% of the placebo group, compared with 2.1% of the combined vaccine group. The time from randomization to first episode of gastroenteritis was significantly longer among participants who received the vaccine, compared with those who received placebo.

“The use of a neonatal dose was investigated in the early phase of development of the rotavirus vaccine but was not pursued because of concerns regarding inadequate immune responses and safety,” wrote Dr. Bines and her associates

They noted that the results of this trial compared favorably with the efficacy of licensed vaccines in similar low-income countries that experienced a high burden of rotavirus disease.

The rates of severe adverse events were similar across all the trial groups. There were no episodes of intussusception seen within the 21-day risk period after immunization, either in the vaccine or placebo groups. However, there was one episode of intussusception in a child on the infant schedule group, which occurred 114 days after the third dose of the vaccine.

“Because intussusception is rare in newborns, the administration of a rotavirus vaccine at the time of birth may offer a safety advantage,” Dr. Bines and her associates said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants, and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

SOURCE: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A new oral rotavirus vaccine given to newborns was associated with significant reductions in the incidence of severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Major finding: A new oral rotavirus vaccine given within the first 5 days of life showed 94% efficacy at 12 months of age.

Data source: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial in 1,513 healthy newborns.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council, PT Bio Farma, and the Victorian government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Authors declared fees, grants and institutional support from the study sponsors, and three authors also declared a stake in the patent of the RV3-BB vaccine, which is licensed to PT Bio Farma.

Source: Bines JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:719-30.

Pre–bariatric surgery weight loss improves outcomes

Preoperative weight loss improves bariatric surgery outcomes, according to findings from a single-institution retrospective analysis. The weight loss came from following a 4-week low-calorie diet (LCD) and was of greatest benefit to patients who lost 8% or more of their excess weight. These patients had a greater loss of excess weight in the 12 months following surgery, as well as shorter average hospital length of stay.

Preliminary studies indicated that short-term weight loss before surgery might reduce surgical complexity by reducing the size of the liver and intra-abdominal fat mass, but it remained uncertain what effect weight loss might have on long-term outcomes.

The LCD included 1,200 kcal/day (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat), which were consumed through five meal-replacement products and one food-based meal. Liquids included at least 80 ounces of calorie-free, caffeine-free, carbonation-free beverages per day. Patients were also instructed to conduct 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day.

Deborah A. Hutcheon, DCN, and her fellow researchers analyzed data from their own institution, where a presurgical 4-week LCD with a target loss of 8% or more of excess weight had been standard policy already. The population included 355 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (n = 167) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (n = 188) between January 2014 and January 2016.

Almost two-thirds (63.3%) of patients achieved the target weight loss before surgery. There were some differences between the two groups. The group that achieved the target contained a greater proportion of men than did the other group (25.5% vs. 13.7%, respectively; P = .013), a higher proportion of white patients (84.8% vs. 74.1%; P = .011), and a higher proportion of patients taking antihypertensive medications (68.3% vs. 57.3%; P = .048). The two groups had similar rates of preoperative comorbidities and surgery types.

Those who achieved the target weight loss had a shorter hospital length of stay (1.8 days vs. 2.1 days; P = .006). They also had a higher percentage loss of excess weight at 3 months (42.3% vs. 36.1%; P less than .001), 6 months (56.0% vs. 47.5%; P less than .001), and at 12 months (65.1% vs. 55.7%; P = .003).

After controlling for patient characteristics, insurance status, 12-month diet compliance, and surgery type, successful presurgery weight loss was associated with greater weight loss at 12 months.

SOURCE: Hutcheon DA et al. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.12.032.

Preoperative weight loss improves bariatric surgery outcomes, according to findings from a single-institution retrospective analysis. The weight loss came from following a 4-week low-calorie diet (LCD) and was of greatest benefit to patients who lost 8% or more of their excess weight. These patients had a greater loss of excess weight in the 12 months following surgery, as well as shorter average hospital length of stay.

Preliminary studies indicated that short-term weight loss before surgery might reduce surgical complexity by reducing the size of the liver and intra-abdominal fat mass, but it remained uncertain what effect weight loss might have on long-term outcomes.

The LCD included 1,200 kcal/day (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat), which were consumed through five meal-replacement products and one food-based meal. Liquids included at least 80 ounces of calorie-free, caffeine-free, carbonation-free beverages per day. Patients were also instructed to conduct 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day.

Deborah A. Hutcheon, DCN, and her fellow researchers analyzed data from their own institution, where a presurgical 4-week LCD with a target loss of 8% or more of excess weight had been standard policy already. The population included 355 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (n = 167) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (n = 188) between January 2014 and January 2016.

Almost two-thirds (63.3%) of patients achieved the target weight loss before surgery. There were some differences between the two groups. The group that achieved the target contained a greater proportion of men than did the other group (25.5% vs. 13.7%, respectively; P = .013), a higher proportion of white patients (84.8% vs. 74.1%; P = .011), and a higher proportion of patients taking antihypertensive medications (68.3% vs. 57.3%; P = .048). The two groups had similar rates of preoperative comorbidities and surgery types.

Those who achieved the target weight loss had a shorter hospital length of stay (1.8 days vs. 2.1 days; P = .006). They also had a higher percentage loss of excess weight at 3 months (42.3% vs. 36.1%; P less than .001), 6 months (56.0% vs. 47.5%; P less than .001), and at 12 months (65.1% vs. 55.7%; P = .003).

After controlling for patient characteristics, insurance status, 12-month diet compliance, and surgery type, successful presurgery weight loss was associated with greater weight loss at 12 months.

SOURCE: Hutcheon DA et al. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.12.032.

Preoperative weight loss improves bariatric surgery outcomes, according to findings from a single-institution retrospective analysis. The weight loss came from following a 4-week low-calorie diet (LCD) and was of greatest benefit to patients who lost 8% or more of their excess weight. These patients had a greater loss of excess weight in the 12 months following surgery, as well as shorter average hospital length of stay.

Preliminary studies indicated that short-term weight loss before surgery might reduce surgical complexity by reducing the size of the liver and intra-abdominal fat mass, but it remained uncertain what effect weight loss might have on long-term outcomes.

The LCD included 1,200 kcal/day (45% carbohydrates, 35% protein, 20% fat), which were consumed through five meal-replacement products and one food-based meal. Liquids included at least 80 ounces of calorie-free, caffeine-free, carbonation-free beverages per day. Patients were also instructed to conduct 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day.

Deborah A. Hutcheon, DCN, and her fellow researchers analyzed data from their own institution, where a presurgical 4-week LCD with a target loss of 8% or more of excess weight had been standard policy already. The population included 355 patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (n = 167) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (n = 188) between January 2014 and January 2016.

Almost two-thirds (63.3%) of patients achieved the target weight loss before surgery. There were some differences between the two groups. The group that achieved the target contained a greater proportion of men than did the other group (25.5% vs. 13.7%, respectively; P = .013), a higher proportion of white patients (84.8% vs. 74.1%; P = .011), and a higher proportion of patients taking antihypertensive medications (68.3% vs. 57.3%; P = .048). The two groups had similar rates of preoperative comorbidities and surgery types.

Those who achieved the target weight loss had a shorter hospital length of stay (1.8 days vs. 2.1 days; P = .006). They also had a higher percentage loss of excess weight at 3 months (42.3% vs. 36.1%; P less than .001), 6 months (56.0% vs. 47.5%; P less than .001), and at 12 months (65.1% vs. 55.7%; P = .003).

After controlling for patient characteristics, insurance status, 12-month diet compliance, and surgery type, successful presurgery weight loss was associated with greater weight loss at 12 months.

SOURCE: Hutcheon DA et al. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.12.032.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Weight loss before bariatric surgery boosts results.

Major finding: Patients who lost at least 8% of excess body weight had an average of 65.1% loss of excess weight at 12 months, compared with the 55.7% seen in those who did not.

Data source: Retrospective, single-center analysis (n = 355).

Disclosures: No source of funding was disclosed.

Source: Hutcheon DA et al. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.12.032.

Basiliximab/BEAM may improve post-ASCT outcomes in PTCL

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Combining a radio-labeled, anti-CD25, monoclonal antibody with BEAM chemotherapy appears to be an effective and safe conditioning regimen prior to autologous stem cell transplant in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), investigators report.

In a phase 1 trial, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 10.6 months for patients treated with the yttrium-90–labeled, chimeric, anti-CD25 antibody basiliximab (Simulect) at one of three dose levels plus standard dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan), said Jasmine Zain, MD, of the City of Hope Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

There have been no significant cases of delayed transplant engraftment or unexpected increases in either mucositis or infectious complications, she said at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

“With standard conditioning, I think the best outcome we have seen is that at 5 years we have about 45% to 50% event-free survival, depending on the histology,” she said. “So we’re hoping we will surpass that.”

The first patient to receive a transplant in the study was treated in July 2015, and since most relapses in this patient population tend to occur within 2 years of transplant, the investigators expect that they will get a better idea of the results in the near future, Dr. Zain said.

PTCL generally has a poor prognosis, and many centers have turned to high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant as a consolidation strategy for patients who are in their first or subsequent complete remissions, as well as for patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

“We in this field consider autologous stem cell transplant to be not curative for PTCL. It is true that some patients will achieve long-term remission and even long-term survival,” she said. ”But overall, even with long-term data, it seems like most patients will eventually relapse.”

The goal of the ongoing study is to determine whether adding basiliximab to BEAM could improve outcomes in the long run.

Unlike ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) – an yttrium-90–labeled antibody that’s been combined with rituximab to target CD20 in relapsed or refractory low-grade follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma – basiliximab is targeted to CD25, which is preferentially expressed on T cells.

Basiliximab has been shown to inhibit growth of human anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) tumors and improve survival in mice bearing human tumor xenografts.

Because the beta particles that basiliximab emits cannot be detected on conventional scans, the antibody is also labeled with an indium-111 radiotracer for purposes of tracking.

At the time of Dr. Zain’s presentation, 13 patients ranging from 19 to 77 years of age were enrolled in the phase 1 trial. The patients were assigned to receive basiliximab at a dose of either 0.4, 0.5, or 0.6 mCi/kg in combination with standard dose BEAM.

The first patient treated had delayed engraftment of platelets; all subsequent patients had engraftment as expected.

There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities at any dose level and no treatment-related mortality. The most frequent toxicity was grade 2 stomatitis, which occurred in three patients each in the 0.4 and 0.6 miC/kg levels and in four patients at the 0.5 miC/kg level of basiliximab. There were no dose-limiting toxicities.

As of the data cutoff, three patients have experienced relapses, and two of those patients died from disease progression. The times from transplant to relapse were 301 days and 218 days in the two patients who died, and it was 108 days in the third patient.

Dose expansion is continuing in the study, with an additional seven patients scheduled for treatment at the 0.6 miC/kg dose, Dr. Zain said.

Dr. Zain did not report information on conflicts of interest. The study is supported by City of Hope Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute. The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

SOURCE: Zain J et al. TCLF 2018.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Combining a radio-labeled, anti-CD25, monoclonal antibody with BEAM chemotherapy appears to be an effective and safe conditioning regimen prior to autologous stem cell transplant in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), investigators report.

In a phase 1 trial, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 10.6 months for patients treated with the yttrium-90–labeled, chimeric, anti-CD25 antibody basiliximab (Simulect) at one of three dose levels plus standard dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan), said Jasmine Zain, MD, of the City of Hope Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

There have been no significant cases of delayed transplant engraftment or unexpected increases in either mucositis or infectious complications, she said at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

“With standard conditioning, I think the best outcome we have seen is that at 5 years we have about 45% to 50% event-free survival, depending on the histology,” she said. “So we’re hoping we will surpass that.”

The first patient to receive a transplant in the study was treated in July 2015, and since most relapses in this patient population tend to occur within 2 years of transplant, the investigators expect that they will get a better idea of the results in the near future, Dr. Zain said.

PTCL generally has a poor prognosis, and many centers have turned to high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant as a consolidation strategy for patients who are in their first or subsequent complete remissions, as well as for patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

“We in this field consider autologous stem cell transplant to be not curative for PTCL. It is true that some patients will achieve long-term remission and even long-term survival,” she said. ”But overall, even with long-term data, it seems like most patients will eventually relapse.”

The goal of the ongoing study is to determine whether adding basiliximab to BEAM could improve outcomes in the long run.

Unlike ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) – an yttrium-90–labeled antibody that’s been combined with rituximab to target CD20 in relapsed or refractory low-grade follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma – basiliximab is targeted to CD25, which is preferentially expressed on T cells.

Basiliximab has been shown to inhibit growth of human anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) tumors and improve survival in mice bearing human tumor xenografts.

Because the beta particles that basiliximab emits cannot be detected on conventional scans, the antibody is also labeled with an indium-111 radiotracer for purposes of tracking.

At the time of Dr. Zain’s presentation, 13 patients ranging from 19 to 77 years of age were enrolled in the phase 1 trial. The patients were assigned to receive basiliximab at a dose of either 0.4, 0.5, or 0.6 mCi/kg in combination with standard dose BEAM.

The first patient treated had delayed engraftment of platelets; all subsequent patients had engraftment as expected.

There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities at any dose level and no treatment-related mortality. The most frequent toxicity was grade 2 stomatitis, which occurred in three patients each in the 0.4 and 0.6 miC/kg levels and in four patients at the 0.5 miC/kg level of basiliximab. There were no dose-limiting toxicities.

As of the data cutoff, three patients have experienced relapses, and two of those patients died from disease progression. The times from transplant to relapse were 301 days and 218 days in the two patients who died, and it was 108 days in the third patient.

Dose expansion is continuing in the study, with an additional seven patients scheduled for treatment at the 0.6 miC/kg dose, Dr. Zain said.

Dr. Zain did not report information on conflicts of interest. The study is supported by City of Hope Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute. The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

SOURCE: Zain J et al. TCLF 2018.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Combining a radio-labeled, anti-CD25, monoclonal antibody with BEAM chemotherapy appears to be an effective and safe conditioning regimen prior to autologous stem cell transplant in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), investigators report.

In a phase 1 trial, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 10.6 months for patients treated with the yttrium-90–labeled, chimeric, anti-CD25 antibody basiliximab (Simulect) at one of three dose levels plus standard dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan), said Jasmine Zain, MD, of the City of Hope Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

There have been no significant cases of delayed transplant engraftment or unexpected increases in either mucositis or infectious complications, she said at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

“With standard conditioning, I think the best outcome we have seen is that at 5 years we have about 45% to 50% event-free survival, depending on the histology,” she said. “So we’re hoping we will surpass that.”

The first patient to receive a transplant in the study was treated in July 2015, and since most relapses in this patient population tend to occur within 2 years of transplant, the investigators expect that they will get a better idea of the results in the near future, Dr. Zain said.

PTCL generally has a poor prognosis, and many centers have turned to high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant as a consolidation strategy for patients who are in their first or subsequent complete remissions, as well as for patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

“We in this field consider autologous stem cell transplant to be not curative for PTCL. It is true that some patients will achieve long-term remission and even long-term survival,” she said. ”But overall, even with long-term data, it seems like most patients will eventually relapse.”

The goal of the ongoing study is to determine whether adding basiliximab to BEAM could improve outcomes in the long run.

Unlike ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) – an yttrium-90–labeled antibody that’s been combined with rituximab to target CD20 in relapsed or refractory low-grade follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma – basiliximab is targeted to CD25, which is preferentially expressed on T cells.

Basiliximab has been shown to inhibit growth of human anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) tumors and improve survival in mice bearing human tumor xenografts.

Because the beta particles that basiliximab emits cannot be detected on conventional scans, the antibody is also labeled with an indium-111 radiotracer for purposes of tracking.

At the time of Dr. Zain’s presentation, 13 patients ranging from 19 to 77 years of age were enrolled in the phase 1 trial. The patients were assigned to receive basiliximab at a dose of either 0.4, 0.5, or 0.6 mCi/kg in combination with standard dose BEAM.

The first patient treated had delayed engraftment of platelets; all subsequent patients had engraftment as expected.

There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities at any dose level and no treatment-related mortality. The most frequent toxicity was grade 2 stomatitis, which occurred in three patients each in the 0.4 and 0.6 miC/kg levels and in four patients at the 0.5 miC/kg level of basiliximab. There were no dose-limiting toxicities.

As of the data cutoff, three patients have experienced relapses, and two of those patients died from disease progression. The times from transplant to relapse were 301 days and 218 days in the two patients who died, and it was 108 days in the third patient.

Dose expansion is continuing in the study, with an additional seven patients scheduled for treatment at the 0.6 miC/kg dose, Dr. Zain said.

Dr. Zain did not report information on conflicts of interest. The study is supported by City of Hope Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute. The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

SOURCE: Zain J et al. TCLF 2018.

REPORTING FROM TLCF 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median progression-free survival posttransplant was 10.6 months.

Study details: A phase 1, dose-finding trial in 13 patients with PTCL.

Disclosures: Dr. Zain did not report information on conflicts of interest. The study is supported by City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, Calif., and the National Cancer Institute.

Source: Zain J et al. TLCF 2018.

Treatment priorities often differ between RA patients, clinicians

Patients with RA and their clinicians approach treatment goals differently based on knowledge, illness experience, and competing priorities, according to findings from a qualitative study.

The results of this study underscore “the tension between having an explicit shared goal between clinicians and patients, and experiencing inherently different – and at times opposing – conceptualization of how one formulates or achieves said goal,” wrote Jennifer L. Barton, MD, of the Department of Veteran Affairs Portland Health Care System and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her coauthors.

Two domains – disease knowledge and psychosocial dynamics – emerged across all focus groups, Dr. Barton and her colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Disease knowledge and education

In the knowledge domain, themes that emerged were informed choice, medication adherence and safety, and clinician assumption of patients’ inability to interpret information. Patients disclosed, for instance, a desire for more information on disease progression and medication side effects to inform future clinician visits, and often sought such information on the Internet.

“Patients highlighted the importance of RA knowledge to understanding what was happening to them physically and the impact of medication on their bodies, and their need to seek information outside of the clinical visit,” the authors noted.

Whereas patients discussed medications in the context of informed decision making, “many clinicians connected RA education to risk of nonadherence and medication safety,” the authors reported. Additionally, “patients did not discuss their adherence to clinician treatment recommendations, though patients expressed dissatisfaction with clinicians who they believed dismissed their medication concerns.”

Some clinicians expressed frustration with patients’ self-education efforts and attitudes toward alternative medicine, and patients reported feeling as though doctors had “diminished the importance of information” they shared.

“Several clinicians voiced perceived paradoxes in current expectations of their professional role as an expert who also defers to patient preferences,” the authors said. “Many clinicians voiced frustration with patients seeking knowledge from what they considered unreliable sources, which prompted varying levels of comfort among clinicians with some adopting a more paternalistic stance.”

Psychosocial dynamics of RA illness

The psychosocial dynamics domain focused on stress and found that patients’ experiences with RA informed their treatment preferences and affected patient-provider communication. For instance, patients who experienced inability to participate in activities because of pain or fatigue prioritized treatment goals aimed at pain reduction and increased energy, with minimal side effects.

“In contrast, clinicians talked about using objective clinical markers” to inform treatment strategy, the authors said. Although they acknowledged the psychosocial stress experienced by patients, clinicians cited limited time and resources as a main reason for their inability to adequately address these concerns.

Both patients and clinicians acknowledged the role of fear in the disease experience, with providers asserting that patients’ fear “disrupted effective communication and complicated patient willingness to follow treatment recommendations,” the authors said.

Lastly, both patients and clinicians described treatment decisions as a “negotiation” in which patients’ priorities of quality of life improvements, such as pain reduction, often were at odds with objective clinical goals of the provider, such as addressing underlying damage.

“Patients indicated that clinician goals focused on objective clinical markers and helping patients achieve remission; however, patients expressed a desire for clinicians to look beyond clinical markers and consider patients’ quality of life goals as well as being open to multiple treatment possibilities,” the authors said.

Areas for improvement

The results of the study highlight potential areas for improvement in patient-clinician communication, namely by balancing the imparting of clinician knowledge with sincere consideration of patient preferences and priorities. “The mismatch in attitudes towards the goal of knowledge between patients and clinicians may lead to suboptimal communication and lack of trust,” the authors wrote. “Patients’ desire for information on a range of RA topics is important, but the value attached to that knowledge is where patients and clinicians diverge.”

Resources aimed at facilitating a conversation around goals may lead to greater goal concordance, which could potentially result in more high value treatment, the authors concluded. “With tools and training to support patient goal-directed care in rheumatology, improved outcomes and reduced disparities may be achieved.”

The study was funded by a grant to Dr. Barton from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barton JL et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/acr.23541.

Patients with RA and their clinicians approach treatment goals differently based on knowledge, illness experience, and competing priorities, according to findings from a qualitative study.

The results of this study underscore “the tension between having an explicit shared goal between clinicians and patients, and experiencing inherently different – and at times opposing – conceptualization of how one formulates or achieves said goal,” wrote Jennifer L. Barton, MD, of the Department of Veteran Affairs Portland Health Care System and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her coauthors.

Two domains – disease knowledge and psychosocial dynamics – emerged across all focus groups, Dr. Barton and her colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Disease knowledge and education

In the knowledge domain, themes that emerged were informed choice, medication adherence and safety, and clinician assumption of patients’ inability to interpret information. Patients disclosed, for instance, a desire for more information on disease progression and medication side effects to inform future clinician visits, and often sought such information on the Internet.

“Patients highlighted the importance of RA knowledge to understanding what was happening to them physically and the impact of medication on their bodies, and their need to seek information outside of the clinical visit,” the authors noted.

Whereas patients discussed medications in the context of informed decision making, “many clinicians connected RA education to risk of nonadherence and medication safety,” the authors reported. Additionally, “patients did not discuss their adherence to clinician treatment recommendations, though patients expressed dissatisfaction with clinicians who they believed dismissed their medication concerns.”

Some clinicians expressed frustration with patients’ self-education efforts and attitudes toward alternative medicine, and patients reported feeling as though doctors had “diminished the importance of information” they shared.

“Several clinicians voiced perceived paradoxes in current expectations of their professional role as an expert who also defers to patient preferences,” the authors said. “Many clinicians voiced frustration with patients seeking knowledge from what they considered unreliable sources, which prompted varying levels of comfort among clinicians with some adopting a more paternalistic stance.”

Psychosocial dynamics of RA illness

The psychosocial dynamics domain focused on stress and found that patients’ experiences with RA informed their treatment preferences and affected patient-provider communication. For instance, patients who experienced inability to participate in activities because of pain or fatigue prioritized treatment goals aimed at pain reduction and increased energy, with minimal side effects.

“In contrast, clinicians talked about using objective clinical markers” to inform treatment strategy, the authors said. Although they acknowledged the psychosocial stress experienced by patients, clinicians cited limited time and resources as a main reason for their inability to adequately address these concerns.

Both patients and clinicians acknowledged the role of fear in the disease experience, with providers asserting that patients’ fear “disrupted effective communication and complicated patient willingness to follow treatment recommendations,” the authors said.

Lastly, both patients and clinicians described treatment decisions as a “negotiation” in which patients’ priorities of quality of life improvements, such as pain reduction, often were at odds with objective clinical goals of the provider, such as addressing underlying damage.

“Patients indicated that clinician goals focused on objective clinical markers and helping patients achieve remission; however, patients expressed a desire for clinicians to look beyond clinical markers and consider patients’ quality of life goals as well as being open to multiple treatment possibilities,” the authors said.

Areas for improvement

The results of the study highlight potential areas for improvement in patient-clinician communication, namely by balancing the imparting of clinician knowledge with sincere consideration of patient preferences and priorities. “The mismatch in attitudes towards the goal of knowledge between patients and clinicians may lead to suboptimal communication and lack of trust,” the authors wrote. “Patients’ desire for information on a range of RA topics is important, but the value attached to that knowledge is where patients and clinicians diverge.”

Resources aimed at facilitating a conversation around goals may lead to greater goal concordance, which could potentially result in more high value treatment, the authors concluded. “With tools and training to support patient goal-directed care in rheumatology, improved outcomes and reduced disparities may be achieved.”

The study was funded by a grant to Dr. Barton from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barton JL et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/acr.23541.

Patients with RA and their clinicians approach treatment goals differently based on knowledge, illness experience, and competing priorities, according to findings from a qualitative study.

The results of this study underscore “the tension between having an explicit shared goal between clinicians and patients, and experiencing inherently different – and at times opposing – conceptualization of how one formulates or achieves said goal,” wrote Jennifer L. Barton, MD, of the Department of Veteran Affairs Portland Health Care System and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and her coauthors.

Two domains – disease knowledge and psychosocial dynamics – emerged across all focus groups, Dr. Barton and her colleagues reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

Disease knowledge and education

In the knowledge domain, themes that emerged were informed choice, medication adherence and safety, and clinician assumption of patients’ inability to interpret information. Patients disclosed, for instance, a desire for more information on disease progression and medication side effects to inform future clinician visits, and often sought such information on the Internet.

“Patients highlighted the importance of RA knowledge to understanding what was happening to them physically and the impact of medication on their bodies, and their need to seek information outside of the clinical visit,” the authors noted.

Whereas patients discussed medications in the context of informed decision making, “many clinicians connected RA education to risk of nonadherence and medication safety,” the authors reported. Additionally, “patients did not discuss their adherence to clinician treatment recommendations, though patients expressed dissatisfaction with clinicians who they believed dismissed their medication concerns.”

Some clinicians expressed frustration with patients’ self-education efforts and attitudes toward alternative medicine, and patients reported feeling as though doctors had “diminished the importance of information” they shared.

“Several clinicians voiced perceived paradoxes in current expectations of their professional role as an expert who also defers to patient preferences,” the authors said. “Many clinicians voiced frustration with patients seeking knowledge from what they considered unreliable sources, which prompted varying levels of comfort among clinicians with some adopting a more paternalistic stance.”

Psychosocial dynamics of RA illness

The psychosocial dynamics domain focused on stress and found that patients’ experiences with RA informed their treatment preferences and affected patient-provider communication. For instance, patients who experienced inability to participate in activities because of pain or fatigue prioritized treatment goals aimed at pain reduction and increased energy, with minimal side effects.

“In contrast, clinicians talked about using objective clinical markers” to inform treatment strategy, the authors said. Although they acknowledged the psychosocial stress experienced by patients, clinicians cited limited time and resources as a main reason for their inability to adequately address these concerns.

Both patients and clinicians acknowledged the role of fear in the disease experience, with providers asserting that patients’ fear “disrupted effective communication and complicated patient willingness to follow treatment recommendations,” the authors said.

Lastly, both patients and clinicians described treatment decisions as a “negotiation” in which patients’ priorities of quality of life improvements, such as pain reduction, often were at odds with objective clinical goals of the provider, such as addressing underlying damage.

“Patients indicated that clinician goals focused on objective clinical markers and helping patients achieve remission; however, patients expressed a desire for clinicians to look beyond clinical markers and consider patients’ quality of life goals as well as being open to multiple treatment possibilities,” the authors said.

Areas for improvement

The results of the study highlight potential areas for improvement in patient-clinician communication, namely by balancing the imparting of clinician knowledge with sincere consideration of patient preferences and priorities. “The mismatch in attitudes towards the goal of knowledge between patients and clinicians may lead to suboptimal communication and lack of trust,” the authors wrote. “Patients’ desire for information on a range of RA topics is important, but the value attached to that knowledge is where patients and clinicians diverge.”

Resources aimed at facilitating a conversation around goals may lead to greater goal concordance, which could potentially result in more high value treatment, the authors concluded. “With tools and training to support patient goal-directed care in rheumatology, improved outcomes and reduced disparities may be achieved.”

The study was funded by a grant to Dr. Barton from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barton JL et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/acr.23541.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In the knowledge domain, recurrent issues were informed choice, medication adherence, and clinician assumption of patient inability to interpret information; the psychosocial dynamics domain found that patient illness experience affected treatment decisions and patient-provider communication.

Data source: A qualitative focus group study of 19 RA patients and 18 clinicians.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant to Dr. Barton from the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Barton JL et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Feb 13. doi: 10.1002/acr.23541.