User login

A Patient With Diabetes, Renal Disease, and Melanoma

Patients who are on hemodialysis and who have cancer present a “unique challenge,” say clinicians from Dartmouth-Hitchcock in New Hampshire.

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at risk of drug accumulation and toxicity. Many anticancer drugs and their metabolites are excreted by the kidney, but data to guide dose and schedule adjustments in renal dialysis are “scant,” the clinicians say. They cite a study that found 72% of dialysis patients receiving anticancer drugs needed dosage adjustments for at least 1 drug. The study researchers also found a significant number of chemotherapy drugs for which there were no available recommendations in dialysis patients.

However, a safe and effective alternative for these patients may exist. The clinicians report on a case—to the best of their knowledge, the first such—of a patient with metastatic melanoma who was successfully treated with pembrolizumab while on hemodialysis.

The patient, who had diabetes and ESRD, also had melanoma in his ear, which metastasized. After discussing his therapeutic options—including the limited data on available immunotherapy drugs—clinicians and the patient agreed to proceed with pembrolizumab, an IgG4-κ human antiprogrammed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody. Pembrolizumab has been shown to improve survival rates in patients with melanoma, although it had not been reported in patients with melanoma on dialysis.

The patient received pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg/dose, repeated every 3 weeks. After 1 dose, his abdominal pain and appetite improved. Serum lactate dehydrogenase dropped from 1,182 to 354 units/L. He continued on dialysis 3 times a week with stable serum creatinine levels. After 3 cycles, the computerized tomography scan showed the pulmonary nodules had resolved, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was significantly reduced. After 10 cycles, he was in complete remission.

Pembrolizumab has distinct benefits for patients like theirs, the clinicians suggest. For one, the molecular weight of the antibody means it is not dialysable, so ultrafiltration (reducing drug exposure) is not the issue it might be. The drug can likely be given without regard to the timing of dialysis. Another benefit for these patients who are usually immunocompromised is that PD-1 antibodies “disrupt” the interactions that create an “immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment” and allow T-cell antitumor activity, the clinicians say.

Their report demonstrates that PD-1 antibodies can be effective in dialysis-dependent ESRD, they say, but add that further research into the induced immune response is warranted. In clinical trials, a small number of patients on pembrolizumab (0.4%) developed immune-mediated nephritis. That might not be as crucial for patients who are already on hemodialysis, the clinicians note, but they caution that the adverse effect (AE) could be a risk for patients with normal renal function or chronic kidney disease. However, their patient experienced no pembrolizumab-related AEs other than mild fatigue.

Source:

Chang R, Shirai K. BMJ Case Rep. 2016; pii: bcr2016216426.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216426.

Patients who are on hemodialysis and who have cancer present a “unique challenge,” say clinicians from Dartmouth-Hitchcock in New Hampshire.

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at risk of drug accumulation and toxicity. Many anticancer drugs and their metabolites are excreted by the kidney, but data to guide dose and schedule adjustments in renal dialysis are “scant,” the clinicians say. They cite a study that found 72% of dialysis patients receiving anticancer drugs needed dosage adjustments for at least 1 drug. The study researchers also found a significant number of chemotherapy drugs for which there were no available recommendations in dialysis patients.

However, a safe and effective alternative for these patients may exist. The clinicians report on a case—to the best of their knowledge, the first such—of a patient with metastatic melanoma who was successfully treated with pembrolizumab while on hemodialysis.

The patient, who had diabetes and ESRD, also had melanoma in his ear, which metastasized. After discussing his therapeutic options—including the limited data on available immunotherapy drugs—clinicians and the patient agreed to proceed with pembrolizumab, an IgG4-κ human antiprogrammed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody. Pembrolizumab has been shown to improve survival rates in patients with melanoma, although it had not been reported in patients with melanoma on dialysis.

The patient received pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg/dose, repeated every 3 weeks. After 1 dose, his abdominal pain and appetite improved. Serum lactate dehydrogenase dropped from 1,182 to 354 units/L. He continued on dialysis 3 times a week with stable serum creatinine levels. After 3 cycles, the computerized tomography scan showed the pulmonary nodules had resolved, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was significantly reduced. After 10 cycles, he was in complete remission.

Pembrolizumab has distinct benefits for patients like theirs, the clinicians suggest. For one, the molecular weight of the antibody means it is not dialysable, so ultrafiltration (reducing drug exposure) is not the issue it might be. The drug can likely be given without regard to the timing of dialysis. Another benefit for these patients who are usually immunocompromised is that PD-1 antibodies “disrupt” the interactions that create an “immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment” and allow T-cell antitumor activity, the clinicians say.

Their report demonstrates that PD-1 antibodies can be effective in dialysis-dependent ESRD, they say, but add that further research into the induced immune response is warranted. In clinical trials, a small number of patients on pembrolizumab (0.4%) developed immune-mediated nephritis. That might not be as crucial for patients who are already on hemodialysis, the clinicians note, but they caution that the adverse effect (AE) could be a risk for patients with normal renal function or chronic kidney disease. However, their patient experienced no pembrolizumab-related AEs other than mild fatigue.

Source:

Chang R, Shirai K. BMJ Case Rep. 2016; pii: bcr2016216426.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216426.

Patients who are on hemodialysis and who have cancer present a “unique challenge,” say clinicians from Dartmouth-Hitchcock in New Hampshire.

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at risk of drug accumulation and toxicity. Many anticancer drugs and their metabolites are excreted by the kidney, but data to guide dose and schedule adjustments in renal dialysis are “scant,” the clinicians say. They cite a study that found 72% of dialysis patients receiving anticancer drugs needed dosage adjustments for at least 1 drug. The study researchers also found a significant number of chemotherapy drugs for which there were no available recommendations in dialysis patients.

However, a safe and effective alternative for these patients may exist. The clinicians report on a case—to the best of their knowledge, the first such—of a patient with metastatic melanoma who was successfully treated with pembrolizumab while on hemodialysis.

The patient, who had diabetes and ESRD, also had melanoma in his ear, which metastasized. After discussing his therapeutic options—including the limited data on available immunotherapy drugs—clinicians and the patient agreed to proceed with pembrolizumab, an IgG4-κ human antiprogrammed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody. Pembrolizumab has been shown to improve survival rates in patients with melanoma, although it had not been reported in patients with melanoma on dialysis.

The patient received pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg/dose, repeated every 3 weeks. After 1 dose, his abdominal pain and appetite improved. Serum lactate dehydrogenase dropped from 1,182 to 354 units/L. He continued on dialysis 3 times a week with stable serum creatinine levels. After 3 cycles, the computerized tomography scan showed the pulmonary nodules had resolved, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was significantly reduced. After 10 cycles, he was in complete remission.

Pembrolizumab has distinct benefits for patients like theirs, the clinicians suggest. For one, the molecular weight of the antibody means it is not dialysable, so ultrafiltration (reducing drug exposure) is not the issue it might be. The drug can likely be given without regard to the timing of dialysis. Another benefit for these patients who are usually immunocompromised is that PD-1 antibodies “disrupt” the interactions that create an “immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment” and allow T-cell antitumor activity, the clinicians say.

Their report demonstrates that PD-1 antibodies can be effective in dialysis-dependent ESRD, they say, but add that further research into the induced immune response is warranted. In clinical trials, a small number of patients on pembrolizumab (0.4%) developed immune-mediated nephritis. That might not be as crucial for patients who are already on hemodialysis, the clinicians note, but they caution that the adverse effect (AE) could be a risk for patients with normal renal function or chronic kidney disease. However, their patient experienced no pembrolizumab-related AEs other than mild fatigue.

Source:

Chang R, Shirai K. BMJ Case Rep. 2016; pii: bcr2016216426.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216426.

High healthcare costs follow CCSs into adulthood

New research suggests survivors of childhood cancer can incur high out-of-pocket medical costs into adulthood and may forgo healthcare to lessen this financial burden.

The study showed that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) were more likely than non-CCSs to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income.

And these high costs were associated with delaying care or skipping it altogether.

These findings were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Survivors who reported spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs were not only more likely to report financial burden, they also were at risk for undertaking behaviors potentially detrimental to their health in order to save money,” said study author Ryan Nipp, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“While studies have identified associations between financial burden and patients’ treatment outcomes, quality of life, and even survival among adults with cancer, as far as we know, this is the first to report these associations in survivors of childhood cancer.”

For this research, Dr Nipp and his colleagues surveyed participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. This included adults who had been treated for childhood cancers between 1970 and 1986 along with a control group of siblings not affected by cancer.

In 2011 and 2012, participants were asked to provide information about their health insurance, the out-of-pocket healthcare costs they paid during the previous year, and sociodemographic information such as annual income and employment status.

The researchers also asked participants whether medical costs posed a financial burden and, if so, what measures they had taken to deal with that burden.

Study population

The researchers received complete responses from 580 CCSs and 173 of their siblings without a history of cancer. The most common cancer diagnosis was leukemia (33%), followed by Hodgkin lymphoma (14%), while non-Hodgkin lymphoma was less common (7%).

CCSs were a mean of 30.2 years from diagnosis. Use of chemotherapy (77%), radiation (66%), and surgery (81%) were common. Few patients had cancer recurrence (13%) or second cancers (5%).

There was no significant difference between CCSs and their siblings with regard to age at the time of the survey (P=0.071), household income (P=0.053), education (P=0.345), health insurance status (P=0.317), or having at least 1 hospitalization in the past year (P=0.270).

However, CCSs were significantly more likely than siblings to have chronic health conditions (P<0.001). Forty percent of CCSs had severe or life-threatening chronic conditions, compared to 17% of siblings.

Seventy-six percent of CCSs and 80% of siblings were employed. Twenty-nine percent of CCSs and 39% of siblings had household incomes exceeding $100,000. Twelve percent of CCSs and 5% of siblings had household incomes below $20,000.

Ninety-one percent of CCSs and 93% of siblings were insured. Most subjects in both groups (81% and 87%, respectively) had employer-sponsored insurance.

Results

CCSs were significantly more likely than their siblings to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income—10% and 3%, respectively (P<0.001).

Among CCSs, those with higher out-of-pocket costs (≥10% vs <10% of income) were more likely to have household incomes below $50,000 (odds ratio [OR]=5.5) and to report being hospitalized in the past year (OR=2.3).

CCSs with a higher percentage of their income spent on out-of-pocket costs were also more likely to:

- Have problems paying their medical bills (OR=8.8)

- Report inability to pay for basic costs of living such as food, heat, or rent (OR=6.1)

- Defer healthcare for a medical problem (OR=3.1)

- Skip a test, treatment, or follow-up (OR=2.1)

- Consider filing for bankruptcy (OR=6.4).

“A more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between high out-of-pocket medical costs and the adverse effects of increased financial burden on cancer survivors could be instrumental in helping us identify those at risk for higher costs to help us address their financial challenges and improve health outcomes,” Dr Nipp said.

“It could also help inform policy changes to help meet the unique needs of cancer survivors and improve our understanding of how both higher costs and resulting financial burden influence patients’ approach to their medical care and decision-making.” ![]()

New research suggests survivors of childhood cancer can incur high out-of-pocket medical costs into adulthood and may forgo healthcare to lessen this financial burden.

The study showed that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) were more likely than non-CCSs to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income.

And these high costs were associated with delaying care or skipping it altogether.

These findings were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Survivors who reported spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs were not only more likely to report financial burden, they also were at risk for undertaking behaviors potentially detrimental to their health in order to save money,” said study author Ryan Nipp, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“While studies have identified associations between financial burden and patients’ treatment outcomes, quality of life, and even survival among adults with cancer, as far as we know, this is the first to report these associations in survivors of childhood cancer.”

For this research, Dr Nipp and his colleagues surveyed participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. This included adults who had been treated for childhood cancers between 1970 and 1986 along with a control group of siblings not affected by cancer.

In 2011 and 2012, participants were asked to provide information about their health insurance, the out-of-pocket healthcare costs they paid during the previous year, and sociodemographic information such as annual income and employment status.

The researchers also asked participants whether medical costs posed a financial burden and, if so, what measures they had taken to deal with that burden.

Study population

The researchers received complete responses from 580 CCSs and 173 of their siblings without a history of cancer. The most common cancer diagnosis was leukemia (33%), followed by Hodgkin lymphoma (14%), while non-Hodgkin lymphoma was less common (7%).

CCSs were a mean of 30.2 years from diagnosis. Use of chemotherapy (77%), radiation (66%), and surgery (81%) were common. Few patients had cancer recurrence (13%) or second cancers (5%).

There was no significant difference between CCSs and their siblings with regard to age at the time of the survey (P=0.071), household income (P=0.053), education (P=0.345), health insurance status (P=0.317), or having at least 1 hospitalization in the past year (P=0.270).

However, CCSs were significantly more likely than siblings to have chronic health conditions (P<0.001). Forty percent of CCSs had severe or life-threatening chronic conditions, compared to 17% of siblings.

Seventy-six percent of CCSs and 80% of siblings were employed. Twenty-nine percent of CCSs and 39% of siblings had household incomes exceeding $100,000. Twelve percent of CCSs and 5% of siblings had household incomes below $20,000.

Ninety-one percent of CCSs and 93% of siblings were insured. Most subjects in both groups (81% and 87%, respectively) had employer-sponsored insurance.

Results

CCSs were significantly more likely than their siblings to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income—10% and 3%, respectively (P<0.001).

Among CCSs, those with higher out-of-pocket costs (≥10% vs <10% of income) were more likely to have household incomes below $50,000 (odds ratio [OR]=5.5) and to report being hospitalized in the past year (OR=2.3).

CCSs with a higher percentage of their income spent on out-of-pocket costs were also more likely to:

- Have problems paying their medical bills (OR=8.8)

- Report inability to pay for basic costs of living such as food, heat, or rent (OR=6.1)

- Defer healthcare for a medical problem (OR=3.1)

- Skip a test, treatment, or follow-up (OR=2.1)

- Consider filing for bankruptcy (OR=6.4).

“A more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between high out-of-pocket medical costs and the adverse effects of increased financial burden on cancer survivors could be instrumental in helping us identify those at risk for higher costs to help us address their financial challenges and improve health outcomes,” Dr Nipp said.

“It could also help inform policy changes to help meet the unique needs of cancer survivors and improve our understanding of how both higher costs and resulting financial burden influence patients’ approach to their medical care and decision-making.” ![]()

New research suggests survivors of childhood cancer can incur high out-of-pocket medical costs into adulthood and may forgo healthcare to lessen this financial burden.

The study showed that childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) were more likely than non-CCSs to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income.

And these high costs were associated with delaying care or skipping it altogether.

These findings were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Survivors who reported spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs were not only more likely to report financial burden, they also were at risk for undertaking behaviors potentially detrimental to their health in order to save money,” said study author Ryan Nipp, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“While studies have identified associations between financial burden and patients’ treatment outcomes, quality of life, and even survival among adults with cancer, as far as we know, this is the first to report these associations in survivors of childhood cancer.”

For this research, Dr Nipp and his colleagues surveyed participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. This included adults who had been treated for childhood cancers between 1970 and 1986 along with a control group of siblings not affected by cancer.

In 2011 and 2012, participants were asked to provide information about their health insurance, the out-of-pocket healthcare costs they paid during the previous year, and sociodemographic information such as annual income and employment status.

The researchers also asked participants whether medical costs posed a financial burden and, if so, what measures they had taken to deal with that burden.

Study population

The researchers received complete responses from 580 CCSs and 173 of their siblings without a history of cancer. The most common cancer diagnosis was leukemia (33%), followed by Hodgkin lymphoma (14%), while non-Hodgkin lymphoma was less common (7%).

CCSs were a mean of 30.2 years from diagnosis. Use of chemotherapy (77%), radiation (66%), and surgery (81%) were common. Few patients had cancer recurrence (13%) or second cancers (5%).

There was no significant difference between CCSs and their siblings with regard to age at the time of the survey (P=0.071), household income (P=0.053), education (P=0.345), health insurance status (P=0.317), or having at least 1 hospitalization in the past year (P=0.270).

However, CCSs were significantly more likely than siblings to have chronic health conditions (P<0.001). Forty percent of CCSs had severe or life-threatening chronic conditions, compared to 17% of siblings.

Seventy-six percent of CCSs and 80% of siblings were employed. Twenty-nine percent of CCSs and 39% of siblings had household incomes exceeding $100,000. Twelve percent of CCSs and 5% of siblings had household incomes below $20,000.

Ninety-one percent of CCSs and 93% of siblings were insured. Most subjects in both groups (81% and 87%, respectively) had employer-sponsored insurance.

Results

CCSs were significantly more likely than their siblings to have out-of-pocket medical costs that were at least 10% of their annual income—10% and 3%, respectively (P<0.001).

Among CCSs, those with higher out-of-pocket costs (≥10% vs <10% of income) were more likely to have household incomes below $50,000 (odds ratio [OR]=5.5) and to report being hospitalized in the past year (OR=2.3).

CCSs with a higher percentage of their income spent on out-of-pocket costs were also more likely to:

- Have problems paying their medical bills (OR=8.8)

- Report inability to pay for basic costs of living such as food, heat, or rent (OR=6.1)

- Defer healthcare for a medical problem (OR=3.1)

- Skip a test, treatment, or follow-up (OR=2.1)

- Consider filing for bankruptcy (OR=6.4).

“A more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between high out-of-pocket medical costs and the adverse effects of increased financial burden on cancer survivors could be instrumental in helping us identify those at risk for higher costs to help us address their financial challenges and improve health outcomes,” Dr Nipp said.

“It could also help inform policy changes to help meet the unique needs of cancer survivors and improve our understanding of how both higher costs and resulting financial burden influence patients’ approach to their medical care and decision-making.” ![]()

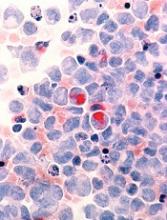

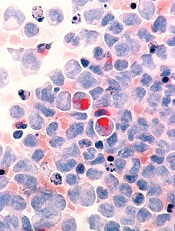

Vitamin C regulates HSCs, curbs AML development

Researchers have described a molecular mechanism that could help explain the link between low vitamin C (ascorbate) levels and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team found that mice with low levels of ascorbate in their blood experience a notable increase in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) frequency and function.

This, in turn, accelerates AML development, partly by inhibiting the tumor suppressor Tet2.

Sean Morrison, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

“We have known for a while that people with lower levels of ascorbate (vitamin C) are at increased cancer risk, but we haven’t fully understood why,” Dr Morrison said. “Our research provides part of the explanation, at least for the blood-forming system.”

Dr Morrison and his colleagues developed a technique for analyzing the metabolic profiles of rare cell populations and used it to compare HSCs to restricted hematopoietic progenitors.

The researchers found that each hematopoietic cell type had a “distinct metabolic signature,” and both human and mouse HSCs had “unusually high” levels of ascorbate, which decreased as the cells differentiated.

To determine if ascorbate is important for HSC function, the team studied mice that lacked gulonolactone oxidase (Gulo), an enzyme mice use to synthesize their own ascorbate. Loss of the enzyme requires Gulo-deficient mice to obtain ascorbate exclusively through their diet like humans do.

So when the researchers fed the mice a standard diet, which contains little ascorbate, the animals’ ascorbate levels were depleted.

The team expected ascorbate depletion might lead to loss of HSC function, but they found the opposite was true. HSCs actually gained function, and this increased the incidence of AML in the mice.

This increase is partly tied to how ascorbate affects Tet2. The researchers found that ascorbate depletion can limit Tet2 function in tissues in a way that increases the risk of AML.

In addition, ascorbate depletion cooperated with Flt3 internal tandem duplication mutations to accelerate leukemogenesis. But the researchers were able to suppress leukemogenesis by feeding animals higher levels of ascorbate.

“Stem cells use ascorbate to regulate the abundance of certain chemical modifications on DNA, which are part of the epigenome,” said study author Michalis Agathocleous, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

“So when stem cells don’t receive enough vitamin C, the epigenome can become damaged in a way that increases stem cell function but also increases the risk of leukemia.”

The researchers said further studies are needed to better understand the potential clinical implications of these findings.

However, the findings may have implications for older patients with clonal hematopoiesis. This condition increases a person’s risk of developing leukemia, but it is not well understood why certain patients develop leukemia and others do not. The results of this study might offer an explanation.

“One of the most common mutations in patients with clonal hematopoiesis is a loss of one copy of TET2,” Dr Morrison said. “Our results suggest patients with clonal hematopoiesis and a TET2 mutation should be particularly careful to get 100% of their daily vitamin C requirement. Because these patients only have one good copy of TET2 left, they need to maximize the residual TET2 tumor-suppressor activity to protect themselves from cancer.” ![]()

Researchers have described a molecular mechanism that could help explain the link between low vitamin C (ascorbate) levels and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team found that mice with low levels of ascorbate in their blood experience a notable increase in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) frequency and function.

This, in turn, accelerates AML development, partly by inhibiting the tumor suppressor Tet2.

Sean Morrison, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

“We have known for a while that people with lower levels of ascorbate (vitamin C) are at increased cancer risk, but we haven’t fully understood why,” Dr Morrison said. “Our research provides part of the explanation, at least for the blood-forming system.”

Dr Morrison and his colleagues developed a technique for analyzing the metabolic profiles of rare cell populations and used it to compare HSCs to restricted hematopoietic progenitors.

The researchers found that each hematopoietic cell type had a “distinct metabolic signature,” and both human and mouse HSCs had “unusually high” levels of ascorbate, which decreased as the cells differentiated.

To determine if ascorbate is important for HSC function, the team studied mice that lacked gulonolactone oxidase (Gulo), an enzyme mice use to synthesize their own ascorbate. Loss of the enzyme requires Gulo-deficient mice to obtain ascorbate exclusively through their diet like humans do.

So when the researchers fed the mice a standard diet, which contains little ascorbate, the animals’ ascorbate levels were depleted.

The team expected ascorbate depletion might lead to loss of HSC function, but they found the opposite was true. HSCs actually gained function, and this increased the incidence of AML in the mice.

This increase is partly tied to how ascorbate affects Tet2. The researchers found that ascorbate depletion can limit Tet2 function in tissues in a way that increases the risk of AML.

In addition, ascorbate depletion cooperated with Flt3 internal tandem duplication mutations to accelerate leukemogenesis. But the researchers were able to suppress leukemogenesis by feeding animals higher levels of ascorbate.

“Stem cells use ascorbate to regulate the abundance of certain chemical modifications on DNA, which are part of the epigenome,” said study author Michalis Agathocleous, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

“So when stem cells don’t receive enough vitamin C, the epigenome can become damaged in a way that increases stem cell function but also increases the risk of leukemia.”

The researchers said further studies are needed to better understand the potential clinical implications of these findings.

However, the findings may have implications for older patients with clonal hematopoiesis. This condition increases a person’s risk of developing leukemia, but it is not well understood why certain patients develop leukemia and others do not. The results of this study might offer an explanation.

“One of the most common mutations in patients with clonal hematopoiesis is a loss of one copy of TET2,” Dr Morrison said. “Our results suggest patients with clonal hematopoiesis and a TET2 mutation should be particularly careful to get 100% of their daily vitamin C requirement. Because these patients only have one good copy of TET2 left, they need to maximize the residual TET2 tumor-suppressor activity to protect themselves from cancer.” ![]()

Researchers have described a molecular mechanism that could help explain the link between low vitamin C (ascorbate) levels and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team found that mice with low levels of ascorbate in their blood experience a notable increase in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) frequency and function.

This, in turn, accelerates AML development, partly by inhibiting the tumor suppressor Tet2.

Sean Morrison, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

“We have known for a while that people with lower levels of ascorbate (vitamin C) are at increased cancer risk, but we haven’t fully understood why,” Dr Morrison said. “Our research provides part of the explanation, at least for the blood-forming system.”

Dr Morrison and his colleagues developed a technique for analyzing the metabolic profiles of rare cell populations and used it to compare HSCs to restricted hematopoietic progenitors.

The researchers found that each hematopoietic cell type had a “distinct metabolic signature,” and both human and mouse HSCs had “unusually high” levels of ascorbate, which decreased as the cells differentiated.

To determine if ascorbate is important for HSC function, the team studied mice that lacked gulonolactone oxidase (Gulo), an enzyme mice use to synthesize their own ascorbate. Loss of the enzyme requires Gulo-deficient mice to obtain ascorbate exclusively through their diet like humans do.

So when the researchers fed the mice a standard diet, which contains little ascorbate, the animals’ ascorbate levels were depleted.

The team expected ascorbate depletion might lead to loss of HSC function, but they found the opposite was true. HSCs actually gained function, and this increased the incidence of AML in the mice.

This increase is partly tied to how ascorbate affects Tet2. The researchers found that ascorbate depletion can limit Tet2 function in tissues in a way that increases the risk of AML.

In addition, ascorbate depletion cooperated with Flt3 internal tandem duplication mutations to accelerate leukemogenesis. But the researchers were able to suppress leukemogenesis by feeding animals higher levels of ascorbate.

“Stem cells use ascorbate to regulate the abundance of certain chemical modifications on DNA, which are part of the epigenome,” said study author Michalis Agathocleous, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

“So when stem cells don’t receive enough vitamin C, the epigenome can become damaged in a way that increases stem cell function but also increases the risk of leukemia.”

The researchers said further studies are needed to better understand the potential clinical implications of these findings.

However, the findings may have implications for older patients with clonal hematopoiesis. This condition increases a person’s risk of developing leukemia, but it is not well understood why certain patients develop leukemia and others do not. The results of this study might offer an explanation.

“One of the most common mutations in patients with clonal hematopoiesis is a loss of one copy of TET2,” Dr Morrison said. “Our results suggest patients with clonal hematopoiesis and a TET2 mutation should be particularly careful to get 100% of their daily vitamin C requirement. Because these patients only have one good copy of TET2 left, they need to maximize the residual TET2 tumor-suppressor activity to protect themselves from cancer.” ![]()

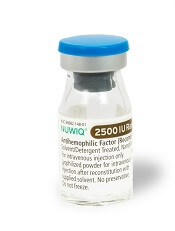

FDA approves new strengths of hemophilia therapy

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved new product strengths for the factor VIII therapy simoctocog alfa (NUWIQ®).

Simoctocog alfa is the first B-domain-deleted recombinant factor VIII product derived from a human cell line—not chemically modified or fused with another protein—designed to treat hemophilia A.

Simoctocog alfa is FDA-approved to treat adults and children with hemophilia A. This includes on-demand treatment and control of bleeding episodes, routine prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, and perioperative management of bleeding.

Now, the FDA has approved single-dose simoctocog alfa vial strengths of 2500, 3000, and 4000 International Units (IU), which will be available for order in the US starting September 2017.

These new vial strengths will be provided in addition to the already available strengths of 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 IU.

“The new vial options will benefit patients, physicians, and healthcare professionals by providing greater treatment flexibility and convenience,” said Flemming Nielsen, president of Octapharma USA, makers of simoctocog alfa.

According to Octapharma, the additional vial strengths offer benefits beyond potentially reducing the number of vials used per patient. The new vial sizes may benefit heavier patients who could use fewer product vials and, in some cases, just one vial.

More vial options will increase dosing flexibility by allowing physicians to select various vial combinations to align closer to the prescribed dose. The new vial sizes could be particularly beneficial to patients using a pharmacokinetic (PK)-guided, personalized prophylaxis approach.

Results of Octapharma’s clinical trial on the PK-guided dosing with simoctocog alfa were published in Haemophilia in April.

This study, known as GENA-21 or NuPreviq, enrolled 66 previously treated adults with severe hemophilia A. Patients were originally started on infusions 3 times a week or every other day. Subsequent dosing intervals were then determined based on individual PK data.

The median dosing interval with PK-guided prophylaxis was 3.5 days, and 57% of patients were able to decrease infusions to twice-weekly or less.

The median weekly prophylaxis dose was reduced by 7.2%, from 100.0 IU kg−1 with standard prophylaxis to 92.8 IU kg−1 during the last 2 months of personalized prophylaxis.

For all bleeds, the mean annualized bleeding rate (ABR) during personalized prophylaxis was 1.45, and the median was 0 (interquartile range, [IQR]: 0, 1.9).

For spontaneous bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.79, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0). For joint bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.91, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0).

None of the patients developed FVIII inhibitors. There were no treatment-related serious or severe adverse events, clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory parameters, or cases of thromboembolism.

The ongoing trial GENA-21b is designed to confirm the results of GENA-21. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved new product strengths for the factor VIII therapy simoctocog alfa (NUWIQ®).

Simoctocog alfa is the first B-domain-deleted recombinant factor VIII product derived from a human cell line—not chemically modified or fused with another protein—designed to treat hemophilia A.

Simoctocog alfa is FDA-approved to treat adults and children with hemophilia A. This includes on-demand treatment and control of bleeding episodes, routine prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, and perioperative management of bleeding.

Now, the FDA has approved single-dose simoctocog alfa vial strengths of 2500, 3000, and 4000 International Units (IU), which will be available for order in the US starting September 2017.

These new vial strengths will be provided in addition to the already available strengths of 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 IU.

“The new vial options will benefit patients, physicians, and healthcare professionals by providing greater treatment flexibility and convenience,” said Flemming Nielsen, president of Octapharma USA, makers of simoctocog alfa.

According to Octapharma, the additional vial strengths offer benefits beyond potentially reducing the number of vials used per patient. The new vial sizes may benefit heavier patients who could use fewer product vials and, in some cases, just one vial.

More vial options will increase dosing flexibility by allowing physicians to select various vial combinations to align closer to the prescribed dose. The new vial sizes could be particularly beneficial to patients using a pharmacokinetic (PK)-guided, personalized prophylaxis approach.

Results of Octapharma’s clinical trial on the PK-guided dosing with simoctocog alfa were published in Haemophilia in April.

This study, known as GENA-21 or NuPreviq, enrolled 66 previously treated adults with severe hemophilia A. Patients were originally started on infusions 3 times a week or every other day. Subsequent dosing intervals were then determined based on individual PK data.

The median dosing interval with PK-guided prophylaxis was 3.5 days, and 57% of patients were able to decrease infusions to twice-weekly or less.

The median weekly prophylaxis dose was reduced by 7.2%, from 100.0 IU kg−1 with standard prophylaxis to 92.8 IU kg−1 during the last 2 months of personalized prophylaxis.

For all bleeds, the mean annualized bleeding rate (ABR) during personalized prophylaxis was 1.45, and the median was 0 (interquartile range, [IQR]: 0, 1.9).

For spontaneous bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.79, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0). For joint bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.91, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0).

None of the patients developed FVIII inhibitors. There were no treatment-related serious or severe adverse events, clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory parameters, or cases of thromboembolism.

The ongoing trial GENA-21b is designed to confirm the results of GENA-21. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved new product strengths for the factor VIII therapy simoctocog alfa (NUWIQ®).

Simoctocog alfa is the first B-domain-deleted recombinant factor VIII product derived from a human cell line—not chemically modified or fused with another protein—designed to treat hemophilia A.

Simoctocog alfa is FDA-approved to treat adults and children with hemophilia A. This includes on-demand treatment and control of bleeding episodes, routine prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, and perioperative management of bleeding.

Now, the FDA has approved single-dose simoctocog alfa vial strengths of 2500, 3000, and 4000 International Units (IU), which will be available for order in the US starting September 2017.

These new vial strengths will be provided in addition to the already available strengths of 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 IU.

“The new vial options will benefit patients, physicians, and healthcare professionals by providing greater treatment flexibility and convenience,” said Flemming Nielsen, president of Octapharma USA, makers of simoctocog alfa.

According to Octapharma, the additional vial strengths offer benefits beyond potentially reducing the number of vials used per patient. The new vial sizes may benefit heavier patients who could use fewer product vials and, in some cases, just one vial.

More vial options will increase dosing flexibility by allowing physicians to select various vial combinations to align closer to the prescribed dose. The new vial sizes could be particularly beneficial to patients using a pharmacokinetic (PK)-guided, personalized prophylaxis approach.

Results of Octapharma’s clinical trial on the PK-guided dosing with simoctocog alfa were published in Haemophilia in April.

This study, known as GENA-21 or NuPreviq, enrolled 66 previously treated adults with severe hemophilia A. Patients were originally started on infusions 3 times a week or every other day. Subsequent dosing intervals were then determined based on individual PK data.

The median dosing interval with PK-guided prophylaxis was 3.5 days, and 57% of patients were able to decrease infusions to twice-weekly or less.

The median weekly prophylaxis dose was reduced by 7.2%, from 100.0 IU kg−1 with standard prophylaxis to 92.8 IU kg−1 during the last 2 months of personalized prophylaxis.

For all bleeds, the mean annualized bleeding rate (ABR) during personalized prophylaxis was 1.45, and the median was 0 (interquartile range, [IQR]: 0, 1.9).

For spontaneous bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.79, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0). For joint bleeds, the mean ABR was 0.91, and the median was 0 (IQR: 0, 0).

None of the patients developed FVIII inhibitors. There were no treatment-related serious or severe adverse events, clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory parameters, or cases of thromboembolism.

The ongoing trial GENA-21b is designed to confirm the results of GENA-21. ![]()

Worsening rash

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected pustular psoriasis, which was confirmed by a dermatologist the patient saw the following day. The dermatologist confirmed this diagnosis by performing a 4-mm punch biopsy, which included an area of new pustules on the patient’s arm. When a rash is extensive, it’s best to biopsy new lesions from the upper body, rather than old lesions below the waist.

Pustular psoriasis can lead to confluent pustules, a condition in which the skin peels off in sheets, resulting in dehydration and a risk of sepsis. This is why you shouldn’t prescribe oral prednisone for any rash before you know that it’s not psoriasis. While oral prednisone may be an effective treatment for many types of dermatitis, it can exacerbate psoriasis (as it did with this patient), and is therefore not an effective or safe treatment for it.

Knowing that pustular psoriasis can become a dermatologic emergency, the FP prescribed oral cyclosporine for the most rapid result. The patient’s blood pressure and kidney function were normal, so it was only necessary for the FP to order baseline laboratory tests. At the follow-up appointment 2 days later, the patient’s condition was already improving and there were no new pustules. Her vital signs remained stable and the pathology report confirmed pustular psoriasis.

The dermatologist planned to transition the patient from cyclosporine to acitretin, determining it was safe to prescribe an oral retinoid. The patient’s hysterectomy 2 years earlier also eliminated concerns about acitretin’s teratogenic potency. The dermatologist prescribed acitretin with directions for the patient to begin taking it in one week, tapering off the cyclosporine once the pustular psoriasis was significantly better.

After a month, the patient was off of cyclosporine completely. Her skin was clear while using daily acitretin. Monitoring of lab tests did not show any adverse effects of the patient using these 2 potentially toxic medications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in the United States

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Clinical Question: What is the epidemiology of meningitis and encephalitis in adults in the United States?

Background: Previous epidemiologic studies have been smaller with less clinical information available and without steroid usage rates.

Study Design: A retrospective database review.

Setting: The Premier HealthCare Database, including hospitals of all types and sizes.

Synopsis: Of patients aged 18 or older, 26,429 were included with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of meningitis or encephalitis from 2011-2014. Enterovirus was the most common infectious cause (51%), followed by unknown etiology (19%), bacterial (14%), herpetic (8%), fungal (3%), and arboviruses (1%). Of patients, 4.2% had HIV.

Steroids were given on the first day of antibiotics in 25.9%. The only statistical mortality benefit was found with steroid use in pneumococcal meningitis (6.7% vs. 12.5%; P = .0245), with a trend toward increased mortality for steroids in fungal meningitis.

Of patients, 87.2% were admitted through the ED, though 22.5% of lumbar punctures were done after admission and 77.4% were discharged home.

Bottom Line: Enterovirus was the most common cause of adult meningoencephalitis, and patients with pneumococcal meningitis who received steroids had decreased mortality.

Citation: Hasbun R, Ning R, Balada-Llasat JM, Chung J, Duff S, Bozzette S, et al. Meningitis and encephalitis in the United States from 2011-2014. Published online, Apr 17, 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix319.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine and pediatrics.

Remediation for surgical trainees may lower attrition

Remediation programs and program director attitudes can make the difference in attrition rates among general surgery residents, according to a survey-based study.

A study by the Association of American Medical Colleges, projects a shortage of 29,000 general surgeons by 2030. Some residency programs are taking steps lower program dropout rates, which has been reported as high as 26% in some programs, according to Alexander Schwed, MD, general surgeon at Harbor–University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center.

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues conducted a survey of 21 general surgery residency program directors. In those programs, the overall attrition rate was found to be much lower than expected – 8.8% over a 5-year period (JAMA Surg. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2656).

The survey showed that programs that implemented resident remediation had lower attrition rates, (21.0% vs 6.8%; P less than .001).

“The association between increased use of remediation by residency programs and low rates of resident attrition is novel,” the investigators wrote. “Nevertheless, based on our findings, high-attrition programs could lower their attrition rates through the increased use of resident remediation and increased focus on resident education.”

Both high- and low-attrition programs selected to participate in the study showed relatively similar median numbers of residents, with low-attrition programs reporting a median of 28 participants per year, and high-attrition programs reporting with 35.

Other similarities between low- and high-attrition programs include percentage of female and minority residents, median of 33.3% and 39.8% respectively, and the number of cases performed by first-, second-, and third-year residents.

The other difference between the six low-attrition programs and the five high-attrition programs was the attitude of the program directors regarding their role in the training of residents, according to researchers.

Investigators asked directors a series of questions using a Likert scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 4 representing “strongly agree.”

Program directors from high- and low-attrition programs tended to agree strongly (scoring 3.8 and 3.2, respectively) with the statement that one of their main roles as a program leader was to “redirect residents who should not be surgeons.”

When asked whether “some degree of resident attrition is a necessary phenomenon,” directors from low-attrition programs scored 2.2, while those from high-attrition programs indicated stronger agreement with an overall score of 3.2.

Directors from programs with high dropout rates were also more likely to consider a 6% dropout rate to be too low, compared with directors from low-attrition programs who thought it was too high.

“When we recruit residents, we are very careful to recruit those who seem to buy into our mission, our vision, and our ideals and fit in well with our culture,” said Sharmila Dissanaike, MD, FACS, department of surgery chair at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, in an interview. “We emphasize teamwork, collegiality, and an ‘all for one and one for all’ type of mentality.”

This kind of recruitment includes having current residents be a part of the process, Dr. Dissanaike explained, and encouraging current and potential residents to have an informal dinner to get to know one another better.

For the department of surgery at Texas Tech, the collaborative culture combined with a remediation program has resulted in a drop in attrition from 20% down to 7% in recent years, Dr. Dissanaike said. In addition, the current success of her program can be partly attributed to a recent decision to maintain the number of incoming residents at five, she said.*

Larger programs can achieve similar improvement, she noted and the rising demand for surgeons makes it essential to find a solution that incorporates the benefits of both types of programs.

“We need more surgeons, we need more Graduate Medical Education spots, we need more training spots for general surgeons,” said Dr. Dissanaike. “I think within those large programs we need to find ways to structure smaller groups, maybe little pods, to help support residents so they don’t get lost.”

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues expressed concern that institutional barriers, such as the focus on test scores, may impede directors from embracing remediation.

“Greater emphasis on the written and oral General Surgery Qualifying Examination pass rates, which are now publicly posted and used by residency review committees, will likely exert pressure on program directors, who may fear that attempting to remediate a resident with poor medical knowledge may affect their program’s 5-year board pass rates,” the investigators wrote. “Our study suggests that such fears may be unfounded because programs with high levels of remediation and low attrition had similar board pass rates as those with high attrition.”

Dr. Schwed and his coinvestigators acknowledged that the programs studied may not be representative of U.S. residencies and selection bias may have affected the findings.

Researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 10/26/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of incoming residents in the program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Remediation programs and program director attitudes can make the difference in attrition rates among general surgery residents, according to a survey-based study.

A study by the Association of American Medical Colleges, projects a shortage of 29,000 general surgeons by 2030. Some residency programs are taking steps lower program dropout rates, which has been reported as high as 26% in some programs, according to Alexander Schwed, MD, general surgeon at Harbor–University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center.

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues conducted a survey of 21 general surgery residency program directors. In those programs, the overall attrition rate was found to be much lower than expected – 8.8% over a 5-year period (JAMA Surg. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2656).

The survey showed that programs that implemented resident remediation had lower attrition rates, (21.0% vs 6.8%; P less than .001).

“The association between increased use of remediation by residency programs and low rates of resident attrition is novel,” the investigators wrote. “Nevertheless, based on our findings, high-attrition programs could lower their attrition rates through the increased use of resident remediation and increased focus on resident education.”

Both high- and low-attrition programs selected to participate in the study showed relatively similar median numbers of residents, with low-attrition programs reporting a median of 28 participants per year, and high-attrition programs reporting with 35.

Other similarities between low- and high-attrition programs include percentage of female and minority residents, median of 33.3% and 39.8% respectively, and the number of cases performed by first-, second-, and third-year residents.

The other difference between the six low-attrition programs and the five high-attrition programs was the attitude of the program directors regarding their role in the training of residents, according to researchers.

Investigators asked directors a series of questions using a Likert scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 4 representing “strongly agree.”

Program directors from high- and low-attrition programs tended to agree strongly (scoring 3.8 and 3.2, respectively) with the statement that one of their main roles as a program leader was to “redirect residents who should not be surgeons.”

When asked whether “some degree of resident attrition is a necessary phenomenon,” directors from low-attrition programs scored 2.2, while those from high-attrition programs indicated stronger agreement with an overall score of 3.2.

Directors from programs with high dropout rates were also more likely to consider a 6% dropout rate to be too low, compared with directors from low-attrition programs who thought it was too high.

“When we recruit residents, we are very careful to recruit those who seem to buy into our mission, our vision, and our ideals and fit in well with our culture,” said Sharmila Dissanaike, MD, FACS, department of surgery chair at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, in an interview. “We emphasize teamwork, collegiality, and an ‘all for one and one for all’ type of mentality.”

This kind of recruitment includes having current residents be a part of the process, Dr. Dissanaike explained, and encouraging current and potential residents to have an informal dinner to get to know one another better.

For the department of surgery at Texas Tech, the collaborative culture combined with a remediation program has resulted in a drop in attrition from 20% down to 7% in recent years, Dr. Dissanaike said. In addition, the current success of her program can be partly attributed to a recent decision to maintain the number of incoming residents at five, she said.*

Larger programs can achieve similar improvement, she noted and the rising demand for surgeons makes it essential to find a solution that incorporates the benefits of both types of programs.

“We need more surgeons, we need more Graduate Medical Education spots, we need more training spots for general surgeons,” said Dr. Dissanaike. “I think within those large programs we need to find ways to structure smaller groups, maybe little pods, to help support residents so they don’t get lost.”

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues expressed concern that institutional barriers, such as the focus on test scores, may impede directors from embracing remediation.

“Greater emphasis on the written and oral General Surgery Qualifying Examination pass rates, which are now publicly posted and used by residency review committees, will likely exert pressure on program directors, who may fear that attempting to remediate a resident with poor medical knowledge may affect their program’s 5-year board pass rates,” the investigators wrote. “Our study suggests that such fears may be unfounded because programs with high levels of remediation and low attrition had similar board pass rates as those with high attrition.”

Dr. Schwed and his coinvestigators acknowledged that the programs studied may not be representative of U.S. residencies and selection bias may have affected the findings.

Researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 10/26/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of incoming residents in the program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Remediation programs and program director attitudes can make the difference in attrition rates among general surgery residents, according to a survey-based study.

A study by the Association of American Medical Colleges, projects a shortage of 29,000 general surgeons by 2030. Some residency programs are taking steps lower program dropout rates, which has been reported as high as 26% in some programs, according to Alexander Schwed, MD, general surgeon at Harbor–University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center.

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues conducted a survey of 21 general surgery residency program directors. In those programs, the overall attrition rate was found to be much lower than expected – 8.8% over a 5-year period (JAMA Surg. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2656).

The survey showed that programs that implemented resident remediation had lower attrition rates, (21.0% vs 6.8%; P less than .001).

“The association between increased use of remediation by residency programs and low rates of resident attrition is novel,” the investigators wrote. “Nevertheless, based on our findings, high-attrition programs could lower their attrition rates through the increased use of resident remediation and increased focus on resident education.”

Both high- and low-attrition programs selected to participate in the study showed relatively similar median numbers of residents, with low-attrition programs reporting a median of 28 participants per year, and high-attrition programs reporting with 35.

Other similarities between low- and high-attrition programs include percentage of female and minority residents, median of 33.3% and 39.8% respectively, and the number of cases performed by first-, second-, and third-year residents.

The other difference between the six low-attrition programs and the five high-attrition programs was the attitude of the program directors regarding their role in the training of residents, according to researchers.

Investigators asked directors a series of questions using a Likert scale with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 4 representing “strongly agree.”

Program directors from high- and low-attrition programs tended to agree strongly (scoring 3.8 and 3.2, respectively) with the statement that one of their main roles as a program leader was to “redirect residents who should not be surgeons.”

When asked whether “some degree of resident attrition is a necessary phenomenon,” directors from low-attrition programs scored 2.2, while those from high-attrition programs indicated stronger agreement with an overall score of 3.2.

Directors from programs with high dropout rates were also more likely to consider a 6% dropout rate to be too low, compared with directors from low-attrition programs who thought it was too high.

“When we recruit residents, we are very careful to recruit those who seem to buy into our mission, our vision, and our ideals and fit in well with our culture,” said Sharmila Dissanaike, MD, FACS, department of surgery chair at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, in an interview. “We emphasize teamwork, collegiality, and an ‘all for one and one for all’ type of mentality.”

This kind of recruitment includes having current residents be a part of the process, Dr. Dissanaike explained, and encouraging current and potential residents to have an informal dinner to get to know one another better.

For the department of surgery at Texas Tech, the collaborative culture combined with a remediation program has resulted in a drop in attrition from 20% down to 7% in recent years, Dr. Dissanaike said. In addition, the current success of her program can be partly attributed to a recent decision to maintain the number of incoming residents at five, she said.*

Larger programs can achieve similar improvement, she noted and the rising demand for surgeons makes it essential to find a solution that incorporates the benefits of both types of programs.

“We need more surgeons, we need more Graduate Medical Education spots, we need more training spots for general surgeons,” said Dr. Dissanaike. “I think within those large programs we need to find ways to structure smaller groups, maybe little pods, to help support residents so they don’t get lost.”

Dr. Schwed and his colleagues expressed concern that institutional barriers, such as the focus on test scores, may impede directors from embracing remediation.

“Greater emphasis on the written and oral General Surgery Qualifying Examination pass rates, which are now publicly posted and used by residency review committees, will likely exert pressure on program directors, who may fear that attempting to remediate a resident with poor medical knowledge may affect their program’s 5-year board pass rates,” the investigators wrote. “Our study suggests that such fears may be unfounded because programs with high levels of remediation and low attrition had similar board pass rates as those with high attrition.”

Dr. Schwed and his coinvestigators acknowledged that the programs studied may not be representative of U.S. residencies and selection bias may have affected the findings.

Researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*Correction, 10/26/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of incoming residents in the program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the 21 programs surveyed, there was an average attrition rate of 8.8% over 5 years.

Data source: Survey of 21 general surgery residency program directors between July 2010 and June 2015.

Disclosures: Investigators report no relevant financial disclosures.

Practicing medicine for all, regardless of differences

I’m a doctor, specifically a neurologist.

I’m also a father with three kids.

I’m also a small business owner and part of the American economy. My practice is small, but provides jobs to two awesome women and in doing so allows them to have insurance, raise their families with job security, own homes, and contribute to the economy. I’m not required to by law, but I provide both with insurance coverage and a retirement plan. I pay my taxes on time and to the penny.

I’m a third-generation American, and a first-generation native Arizonan.

I’m a Phoenix Suns, ASU Sun Devils, and Creighton Bluejays basketball fan.

And, somewhere in all of the above, I’m Jewish.

I’ve never understood hate very well. To me, people are people. I’ve never treated patients differently based on race, religion, political beliefs, or pretty much any other factor. That’s part of my job, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

For the same reason, I don’t understand anti-Semitism. I’ve never ripped anyone off and try very hard to practice ethical medicine, doing what’s right for patients and not for my pocketbook. Some could even argue that this approach has cost me financially over time.

My first direct experience with hate was in 1975, when my family moved from central Phoenix to the suburbs. When we were building our house and meeting future neighbors, one lady circulated a petition to keep Jews out of the neighborhood. A few weeks later, when the school year started, her kids looked me and my sister over and asked us where our horns were.

I don’t encounter it, at least not directly, as much anymore. Perhaps one to two times a year someone will call my office to make an appointment and will ask what my religion is. My secretary tells them that we don’t discuss this professionally here.

But it never goes away entirely. There are always those looking to blame anyone who is slightly different from them for economic and social changes, perhaps because it’s easier than actually working together to solve things. Or because they find it a welcome distraction from the real issues facing our society.

The recent events in Charlottesville are frightening to all of us, regardless of religion, who are trying to get along in everyday life. All I’ve ever wanted is to be able to work and raise my family in peace, yet we’re faced with a stark reminder of those who see this as a threat. Worse, their fires are stoked by seeming indifference (at best) and overt support (at worst) at the highest level of our government – one founded on freedom of religion.

Hate is hate, whether it’s ISIS, the Westboro Baptist Church, KKK, Kahane Chai, or the modern interpretations of Nazism lurking in Europe and America. Although they’ve always been there, today the Internet has given them a larger voice. People whom I’ve never done anything to consider me an enemy.

My kids’ school is a block from a mosque, so I drive by it all the time. It’s an attractive, well-maintained building. Sometimes I see younger kids running around out in the yard, or others playing basketball on a court between buildings. Its proximity has never bothered me. But, like myself, I know those inside are hated by others who don’t even know them. Like me, all they’ve done is raise kids, work, and pay taxes.

There have always been, and will always be, bad people in all religions, races, and ethnic groups. This is the nature of humans. But the association of hating all because of a few is very troubling. I believe the majority of people are good and that none are born hating others.

I try hard to run a blind practice: treating all patients as equal, and giving them the best care I can, regardless of who they are, what they believe, or where they’re from.

Unfortunately, too many people seem to find it easier to slap labels on anyone who doesn’t look or think like them, and decide that’s all they need to hate them and avoid looking at the person inside.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m a doctor, specifically a neurologist.

I’m also a father with three kids.

I’m also a small business owner and part of the American economy. My practice is small, but provides jobs to two awesome women and in doing so allows them to have insurance, raise their families with job security, own homes, and contribute to the economy. I’m not required to by law, but I provide both with insurance coverage and a retirement plan. I pay my taxes on time and to the penny.

I’m a third-generation American, and a first-generation native Arizonan.

I’m a Phoenix Suns, ASU Sun Devils, and Creighton Bluejays basketball fan.

And, somewhere in all of the above, I’m Jewish.

I’ve never understood hate very well. To me, people are people. I’ve never treated patients differently based on race, religion, political beliefs, or pretty much any other factor. That’s part of my job, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

For the same reason, I don’t understand anti-Semitism. I’ve never ripped anyone off and try very hard to practice ethical medicine, doing what’s right for patients and not for my pocketbook. Some could even argue that this approach has cost me financially over time.

My first direct experience with hate was in 1975, when my family moved from central Phoenix to the suburbs. When we were building our house and meeting future neighbors, one lady circulated a petition to keep Jews out of the neighborhood. A few weeks later, when the school year started, her kids looked me and my sister over and asked us where our horns were.

I don’t encounter it, at least not directly, as much anymore. Perhaps one to two times a year someone will call my office to make an appointment and will ask what my religion is. My secretary tells them that we don’t discuss this professionally here.

But it never goes away entirely. There are always those looking to blame anyone who is slightly different from them for economic and social changes, perhaps because it’s easier than actually working together to solve things. Or because they find it a welcome distraction from the real issues facing our society.

The recent events in Charlottesville are frightening to all of us, regardless of religion, who are trying to get along in everyday life. All I’ve ever wanted is to be able to work and raise my family in peace, yet we’re faced with a stark reminder of those who see this as a threat. Worse, their fires are stoked by seeming indifference (at best) and overt support (at worst) at the highest level of our government – one founded on freedom of religion.