User login

Insurance coverage gainers outnumber coverage losers

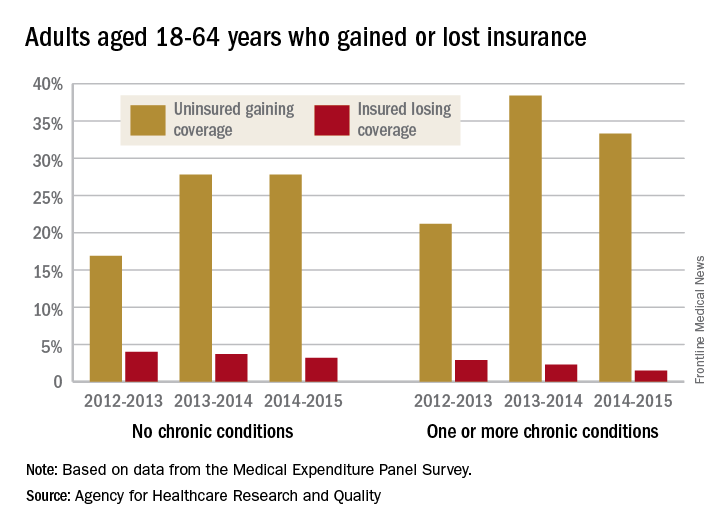

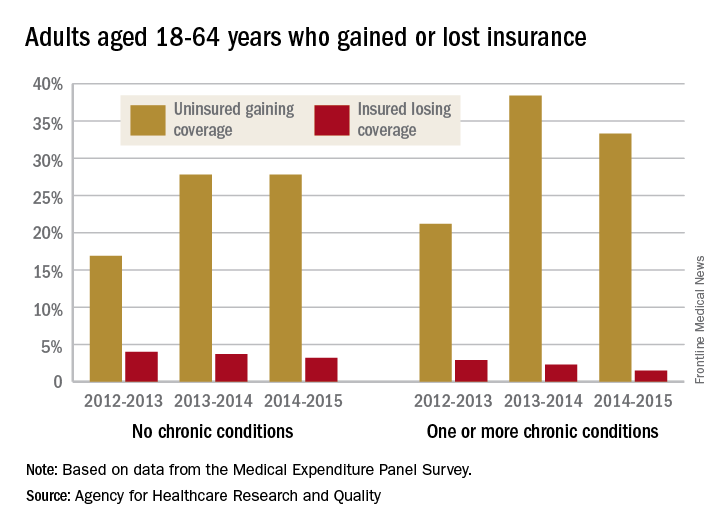

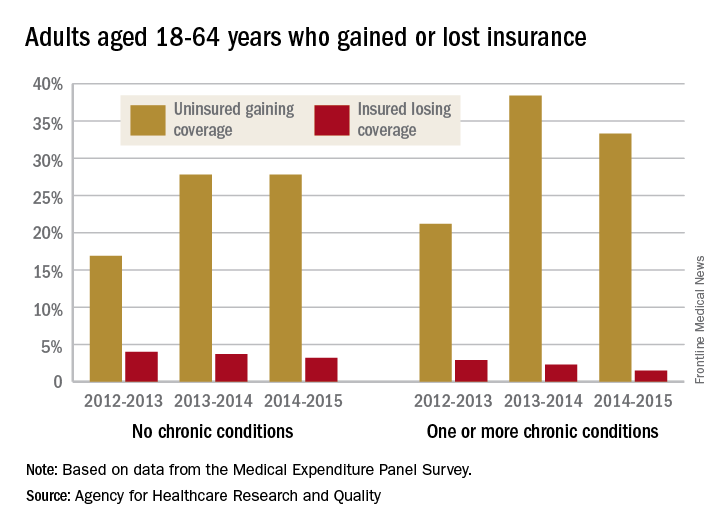

Fewer nonelderly adults lost their health insurance in 2015 than in 2013, while more gained coverage, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The presence of chronic conditions played a part for those who lost coverage. From 2012 to 2013, 2.9% of adults aged 18-64 years with one or more chronic conditions lost their insurance, compared with 1.5% who lost coverage from 2014 to 2015. Those with no chronic conditions saw a corresponding drop from 4% to 3.2%, but that change was not significant, AHRQ investigators reported.

For this analysis, the chronic conditions were active asthma, arthritis, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, bronchitis, and stroke. The source of the data was the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Fewer nonelderly adults lost their health insurance in 2015 than in 2013, while more gained coverage, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The presence of chronic conditions played a part for those who lost coverage. From 2012 to 2013, 2.9% of adults aged 18-64 years with one or more chronic conditions lost their insurance, compared with 1.5% who lost coverage from 2014 to 2015. Those with no chronic conditions saw a corresponding drop from 4% to 3.2%, but that change was not significant, AHRQ investigators reported.

For this analysis, the chronic conditions were active asthma, arthritis, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, bronchitis, and stroke. The source of the data was the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Fewer nonelderly adults lost their health insurance in 2015 than in 2013, while more gained coverage, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The presence of chronic conditions played a part for those who lost coverage. From 2012 to 2013, 2.9% of adults aged 18-64 years with one or more chronic conditions lost their insurance, compared with 1.5% who lost coverage from 2014 to 2015. Those with no chronic conditions saw a corresponding drop from 4% to 3.2%, but that change was not significant, AHRQ investigators reported.

For this analysis, the chronic conditions were active asthma, arthritis, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, bronchitis, and stroke. The source of the data was the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Noninvasive NASH test could help monitor hepatotoxicity in patients on methotrexate

A noninvasive test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic fibrosis could be used to help detect worsening hepatic fibrosis in psoriasis patients who are on long-term methotrexate therapy, according to the authors of a retrospective study published online Aug. 23.

To evaluate the use of the noninvasive test to monitor for hepatic fibrosis in this group of patients and guide the management of methotrexate (MTX) without a liver biopsy, investigators conducted an analysis of 107 patients with psoriasis who were on long-term MTX treatment, for whom the NASH FibroSure test was used between January 2007 and December 2013. All the patients were white, fifty were men, the mean age was 83 years, and almost all of the patients had a body mass index of 28 or more (16% had a BMI between 28 and 30, and 81% had a BMI over 30).

The NASH FibroSure test, which was developed for use in patients suspected of having nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), combines analyses of 10 biochemical markers combined with age, sex, height, and weight to calculate the degree of hepatic fibrosis. The test has a reported sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 78% in detecting risk of significant fibrosis, according to Bruce Bauer, MD, of Pariser Dermatology Specialists, Norfolk, Va., and his coinvestigators (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2083).

Among the 107 patients, the investigators found a statistically significant correlation “between worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative methotrexate” dose among women (P = .02), but not among men (P = .11). In addition, women with a BMI of 28 or more were more likely to have worsening fibrosis scores (P = .03). “There were no differences between men and women with regard to prevalence of a BMI of 28 or more, diabetes, age older than 65 years, or chronic kidney disease,” which they said, suggests that among women, “obesity influences the progression of fibrosis scores.”

The investigators advised providers not to disregard any potential warning signs when using FibroSure on men. “No differences between the cohorts were observed that would explain the association of worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative MTX dose among women but not men,” they wrote. “However, given the implications of the progression of hepatic fibrosis, we still recommend discontinuing MTX for male patients who demonstrate worsening fibrosis scores.”

While the test may not be able to replace liver biopsy, based on these results, the investigators noted that noninvasive tests such as this one could help significantly reduce the number of liver biopsies needed.

They pointed out that because the study was conducted at one center, the next step is to conduct “a prospective, randomized, multi-institutional analysis of NASH FibroSure and liver biopsies for patients with psoriasis receiving MTX vs. other treatments, including a larger cohort of men and women with different racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

One of the four authors reported receiving research funding from T2 Biosystems. Dr. Bauer and the two other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Marshfield Clinic Resident Research Program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

A noninvasive test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic fibrosis could be used to help detect worsening hepatic fibrosis in psoriasis patients who are on long-term methotrexate therapy, according to the authors of a retrospective study published online Aug. 23.

To evaluate the use of the noninvasive test to monitor for hepatic fibrosis in this group of patients and guide the management of methotrexate (MTX) without a liver biopsy, investigators conducted an analysis of 107 patients with psoriasis who were on long-term MTX treatment, for whom the NASH FibroSure test was used between January 2007 and December 2013. All the patients were white, fifty were men, the mean age was 83 years, and almost all of the patients had a body mass index of 28 or more (16% had a BMI between 28 and 30, and 81% had a BMI over 30).

The NASH FibroSure test, which was developed for use in patients suspected of having nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), combines analyses of 10 biochemical markers combined with age, sex, height, and weight to calculate the degree of hepatic fibrosis. The test has a reported sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 78% in detecting risk of significant fibrosis, according to Bruce Bauer, MD, of Pariser Dermatology Specialists, Norfolk, Va., and his coinvestigators (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2083).

Among the 107 patients, the investigators found a statistically significant correlation “between worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative methotrexate” dose among women (P = .02), but not among men (P = .11). In addition, women with a BMI of 28 or more were more likely to have worsening fibrosis scores (P = .03). “There were no differences between men and women with regard to prevalence of a BMI of 28 or more, diabetes, age older than 65 years, or chronic kidney disease,” which they said, suggests that among women, “obesity influences the progression of fibrosis scores.”

The investigators advised providers not to disregard any potential warning signs when using FibroSure on men. “No differences between the cohorts were observed that would explain the association of worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative MTX dose among women but not men,” they wrote. “However, given the implications of the progression of hepatic fibrosis, we still recommend discontinuing MTX for male patients who demonstrate worsening fibrosis scores.”

While the test may not be able to replace liver biopsy, based on these results, the investigators noted that noninvasive tests such as this one could help significantly reduce the number of liver biopsies needed.

They pointed out that because the study was conducted at one center, the next step is to conduct “a prospective, randomized, multi-institutional analysis of NASH FibroSure and liver biopsies for patients with psoriasis receiving MTX vs. other treatments, including a larger cohort of men and women with different racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

One of the four authors reported receiving research funding from T2 Biosystems. Dr. Bauer and the two other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Marshfield Clinic Resident Research Program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

A noninvasive test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic fibrosis could be used to help detect worsening hepatic fibrosis in psoriasis patients who are on long-term methotrexate therapy, according to the authors of a retrospective study published online Aug. 23.

To evaluate the use of the noninvasive test to monitor for hepatic fibrosis in this group of patients and guide the management of methotrexate (MTX) without a liver biopsy, investigators conducted an analysis of 107 patients with psoriasis who were on long-term MTX treatment, for whom the NASH FibroSure test was used between January 2007 and December 2013. All the patients were white, fifty were men, the mean age was 83 years, and almost all of the patients had a body mass index of 28 or more (16% had a BMI between 28 and 30, and 81% had a BMI over 30).

The NASH FibroSure test, which was developed for use in patients suspected of having nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), combines analyses of 10 biochemical markers combined with age, sex, height, and weight to calculate the degree of hepatic fibrosis. The test has a reported sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 78% in detecting risk of significant fibrosis, according to Bruce Bauer, MD, of Pariser Dermatology Specialists, Norfolk, Va., and his coinvestigators (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2083).

Among the 107 patients, the investigators found a statistically significant correlation “between worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative methotrexate” dose among women (P = .02), but not among men (P = .11). In addition, women with a BMI of 28 or more were more likely to have worsening fibrosis scores (P = .03). “There were no differences between men and women with regard to prevalence of a BMI of 28 or more, diabetes, age older than 65 years, or chronic kidney disease,” which they said, suggests that among women, “obesity influences the progression of fibrosis scores.”

The investigators advised providers not to disregard any potential warning signs when using FibroSure on men. “No differences between the cohorts were observed that would explain the association of worsening fibrosis scores and cumulative MTX dose among women but not men,” they wrote. “However, given the implications of the progression of hepatic fibrosis, we still recommend discontinuing MTX for male patients who demonstrate worsening fibrosis scores.”

While the test may not be able to replace liver biopsy, based on these results, the investigators noted that noninvasive tests such as this one could help significantly reduce the number of liver biopsies needed.

They pointed out that because the study was conducted at one center, the next step is to conduct “a prospective, randomized, multi-institutional analysis of NASH FibroSure and liver biopsies for patients with psoriasis receiving MTX vs. other treatments, including a larger cohort of men and women with different racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

One of the four authors reported receiving research funding from T2 Biosystems. Dr. Bauer and the two other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Marshfield Clinic Resident Research Program.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was a significant correlation between worsening fibrosis scores on the test and cumulative methotrexate dose among women (P = .02), but not among men (P = .11).

Data source: A retrospective single-center study analyzing the test in 107 psoriasis patients on methotrexate, collected between January 2007 and December 2013.

Disclosures: One of the four authors received research funding from T2 Biosystems. There were no other financial disclosures.

National Trends (2007-2013) of Clostridium difficile Infection in Patients with Septic Shock: Impact on Outcome

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is the most common infectious cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea.1 Development of a CDI during hospitalization is associated with increases in morbidity, mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost.2-5 The prevalence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased dramatically from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s to almost 9 cases per 1000 discharges; however, the CDI rate since 2007 appears to have plateaued.6,7 Antibiotic use has historically been the most important risk factor for acquiring CDI; however, use of acid-suppressing agents, chemotherapy, chronic comorbidities, and healthcare exposure all also increase the risk of CDI.7-10 The elderly (> 65 years of age) are particularly at risk for developing CDI and having worse clinical outcomes with CDI.6,7

Patients with septic shock (SS) often have multiple CDI risk factors (in particular, extensive antibiotic exposure) and thus, represent a population at a particularly high risk for acquiring a CDI during hospitalization. However, little data are available on the prevalence of CDI acquired in patients hospitalized with SS. We sought to determine the national-level temporal trends in the prevalence of CDI in patients with SS and the impact of CDI complicating SS on clinical outcomes between 2007 and 2013.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) for this study. The NIS is a database developed by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).11 It is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States and has been used by researchers and policy makers to analyze national trends in outcomes and healthcare utilization. The NIS database now approximates a 20% stratified sample of all discharges from all participating US hospitals. Sampling weights are provided by the manufacturer and can be used to produce national-level estimates. Following the redesign of the NIS in 2012, new sampling weights were provided for trend analysis for the years prior to 2012 to account for the new design. Every hospitalization is deidentified and converted into one unique entry that provides information on demographics, hospital characteristics, 1 primary and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses, comorbidities, LOS, in-hospital mortality, and procedures performed during stay. The discharge diagnoses are provided in the form of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes.

The NRD is a database developed for HCUP that contains about 35 million discharges each year and supports readmission data analyses. In 2013, the NRD contained data from 21 geographically diverse states, accounting for 49.1% of all US hospitalizations. Diagnosis, comorbidities, and outcomes are presented in a similar manner to NIS.

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study. Data from the NIS between 2007 and 2013 were used for the analysis. Demographic data obtained included age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index,12 hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Cases with information missing on key demographic variables (age, gender, and race) were excluded. Only adults (>18 years of age) were included for the analysis.

SS was identified by either (1) ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for SS (785.52) or (2) presence of vasopressor use (00.17) along with ICD-9-CM codes of sepsis, severe sepsis, septicemia, bacteremia, or fungemia. This approach is consistent with what has been utilized in other studies to identify cases of sepsis or SS from administrative databases.13-15 The appendix provides a complete list of ICD-9-CM codes used in the study. CDI was identified by ICD-9-CM code 008.45 among the secondary diagnosis. This code has been shown to have good accuracy for identifying CDI using administrative data.16 To minimize the inclusion of cases in which a CDI was present at admission, hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of CDI were not included as cases of CDI complicating SS.

We used NRD 2013 for estimating the effect of CDI on 30-day readmission after initial hospitalizations with SS. We used the criteria for index admissions and 30-day readmissions as defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. We excluded patients who died during their index admission, patients with index discharges in December due to a lack of sufficient time to capture 30-day readmissions, and patients with missing information on key variables. We also excluded patients who were not a resident of the state of index hospitalization since readmission across state boundaries could not be identified in NRD. Manufacturer provided sampling weights were used to produce national level estimates. The cases of SS and CDI were identified by ICD-9-CM codes using the methodology described above.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was the total and yearly prevalence of CDI in patients with SS from 2007 to 2013. The secondary outcomes were mortality, LOS, and 30-day readmissions in patients with SS with and without CDI.

Statistical Analysis

Weighted data from NIS were used for all analyses. Demographics, hospital characteristics, and outcomes of all patients with SS were obtained. The prevalence of CDI was calculated for each calendar year. The temporal trends of outcomes (LOS and in-hospital mortality) of patients were plotted for patients with SS with and without CDI. A χ2 test of trend for proportions was used with the Cochran-Armitage test to calculate statistical significance of changes in prevalence. To test for statistical significance of the temporal trends of LOS, a univariate linear regression was used, with calendar year as a covariate. Independent samples t test, a Mann-Whitney U test, and a χ2 test were used to determine statistical significance of parameters between the group with CDI and the group without CDI.

Prolonged LOS was defined either as a LOS > 75th or > 90th percentile of LOS among all patients with SS. To identify if CDI was associated with a prolonged LOS after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was used. Variables included in the regression model were age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index, hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Data on cases were available for all the above covariates except hospital characteristics, such as teaching status, location, and bed size (these were missing for 0.7% of hospitals).

Stata 13.1.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) were used to perform statistical analyses. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

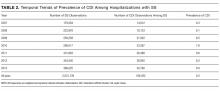

A total of 2,031,739 hospitalizations of adults with SS were identified between 2007 and 2013. CDI was present in 166,432 (8.2%) of these patients. Demographic data are displayed in Table 1. CDI was more commonly observed in elderly patients (> 65 years) with SS; 9.3% among the elderly versus 6.6% among individuals < 65 years; P < 0.001. The prevalence of CDI was greater in urban than in rural hospitals (8.4% vs 5.4%; P < 0.001) and greater in teaching than in nonteaching hospitals (8.7% vs 7.7%; P < 0.001). The prevalence of CDI in SS remained stable between 2007 and 2013 (Table 2).

Mortality

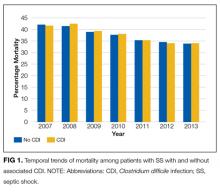

In the overall study cohort, the in-hospital mortality for SS was 37%. The in-hospital mortality rate of patients with SS complicated by a CDI was comparable to the mortality rate of patients without a CDI (37.1% vs 37.0%; P = 0.48). The mortality of patients with SS, with or without CDI, progressively decreased from 2007 to 2013 (P value for trend < 0.001 for each group; Figure 1).

Length of Stay

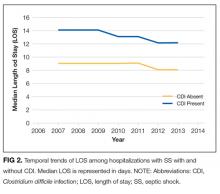

The median LOS for all patients with SS was 9 days. Patients with CDI had a longer median LOS than did those without CDI (13 vs 9 days; P < 0.001). Between 2007 and 2013, the median LOS of CDI group decreased from 14 to 12 days (P < 0.001) while that of non-CDI group decreased from 9 to 8 days (P < 0.001; Figure 2). We also examined LOS among subgroups who were discharged alive and those who died during hospitalization. For patients who were discharged alive, the LOS with and without CDI was 15 days versus 10 days, respectively (P < 0.001). For patients who died during hospitalization, LOS with and without CDI was 10 days versus 6 days, respectively (P < 0.001).

The 75th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 17 days. An LOS > 17 days was observed in 36.9% of SS patients with CDI versus 22.7% without CDI (P < 0.001). After adjusting for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 17 days were significantly greater for SS patients with CDI (odds ratio [OR] 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.06-2.15; P < 0.001).

The 90th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 29 days. An LOS > 29 days was observed in 17.5% of SS patients with a CDI versus 9.1% without a CDI (P < 0.001). After adjustment for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 29 days were significantly greater for SS patients with a CDI (OR 2.25; 95% CI, 2.22-2.28; P < 0.001).

Hospital Readmission

In 2013, patients with SS and CDI had a higher rate of 30-day readmission as compared to patients with SS without CDI (9.8% vs 7.4% respectively; P < 0.001). The multivariate adjusted OR for 30-day readmission for patients with SS and a CDI was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.22-1.31; P < 0.001).

Additional Analyses

Lastly, we performed an additional analysis to confirm our hypothesis that a CDI by itself is rarely a cause of SS, and that CDI as the principal diagnosis would constitute an extremely low number of patients with SS in an administrative dataset. In NIS 2013, there were 105,750 cases with CDI as the primary diagnosis. A total of 4470 (4.2%) had a secondary diagnosis of sepsis and only 930 (0.9%) cases had a secondary diagnosis of SS.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on the prevalence and outcome of CDI complicating SS. By using a large nationally representative sample, we found CDI was very prevalent among individuals hospitalized with SS and, at a level in excess of that seen in other populations. Of interest, we did not observe an increase in mortality of SS when complicated by CDI. On the other hand, patients with SS complicated by CDI were more much likely to have a prolonged hospital LOS and a higher risk of 30-day hospital readmission.

The prevalence of CDI exploded between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, including community, hospital, and intensive care unit (ICU)–related disease.6,7,17-20 Patients with SS often have multiple risk factors associated with CDI and thus represent a high-risk population for developing CDI.7 Our findings are consistent with the suggestion that individuals with SS are at a higher risk of developing CDI. Compared to the rate of CDI in all hospitalized patients, our data suggest an almost 10-fold increase in CDI rate for patients with SS.6 Patients with SS and CDI may account for as much as 10% of total CDIs.6,7 As has been reported for CDI in general, we observed that CDI complicating SS was more common in those > 65 years of age.4,21 The prevalence of CDI we observed in patients with SS was also higher than has been reported in ICU patients in general (1%), and higher than reported for patients requiring mechanical ventilation (6.6%), including prolonged mechanical ventilation (5.3%); further supporting the conclusion that patients with SS are a particularly high-risk group for acquiring CDI, even compared with other ICU patients.20,22,23 Similarly, the rate of CDI among SS was 8 times higher than that of recently reported hospital-onset CDI among patients with sepsis in general (incidence 1.08%).24 We have no data regarding why patients with SS have a higher rate of CDI; however, the intensity and duration of antibiotic treatment of these patients may certainly play a role.25 It has recently been reported that CDI in itself can be a precursor leading to intestinal dysbiosis that can increase the risk of subsequent sepsis. Similarly, patients with SS may have higher prevalence of dysbiosis that, in turn, might predispose them to CDI at a higher rate than other individuals.

Following the increase in CDIs in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, since 2007 the overall prevalence of CDIs has been stable, albeit at the higher rate. More recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported a decrease in hospital onset CDI after 2011.26

The finding that CDI in SS patients was not associated with an increase in mortality is consistent with other reports of CDI in ICU patients in general as well as higher-risk ICU populations such as patients requiring mechanical ventilation, including those on long-term mechanical ventilator support.17,18,20,22,23 Why the mortality of ICU patients with CDI is not increased is not completely clear. It has been suggested that this may be related to early recognition and treatment of CDI developing in the ICU.22 Along these lines, it has been previously observed that for patients with CDI on mechanical ventilation, patients who were transferred to the ICU from the ward had worse clinical outcomes compared to patients directly admitted to the ICU, likely due to delayed recognition and treatment in the former.22 Similarly, ICU patients in whom CDI was identified prior to ICU admission had more severe CDI, and mortality that was directly related to CDI was only observed in patients who had CDI identified pre-ICU transfer.18 The increase in mortality observed in patients with sepsis in general with CDI may reflect similar factors.24 We observed a trend of decreasing mortality in SS patients with or without CDI during 2007 to 2013 consistent to what has been generally reported in SS.13,14

The increase in LOS observed in SS patients with CDI is also consistent with what has been observed in other ICU populations, as well as in patients with sepsis in general.17,22-24 Of note, in addition to the increase in median LOS, we found a significant increase in the number of patients with a prolonged LOS associated with having SS with CDI. It is important to note that development of CDI during hospitalization is affected by pre-CDI hospital LOS, so prolonged LOS may not be solely attributable to CDI. The interaction between LOS and CDI remains complex in which higher LOS might be associated with higher incidence of CDI occurrence, and once established, CDI might be associated with changes in LOS for the remaining hospitalization.

Hospitalized patients with CDI have an overall higher resource utilization than those without CDI.27 A recent review has estimated the overall attributable cost of CDI to be $6.3 billion; the attributable cost per case of hospital acquired CDI being 1.5 times the cost of community-acquired CDI.5 We did not look at cost directly. However, in the high-CDI risk ICU population requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation, those with CDI had a substantial increase in total costs.23 Given the substantial increase in LOS associated with CDI complicating SS, there would likely be a significant increase in hospital costs related to providing care for these patients. Further adding to the potential burden of CDI is our finding that CDI and SS was associated with an increase in 30-day hospital readmission rate. This is consistent with a recent report that ICU patients with CDI who are discharged from the hospital have a 25% 30-day hospital readmission rate.28 However, we do not have data either as to the reason for hospital readmission or whether the initial CDI or CDI recurrence played a role. This suggests that, in addition to intervention directed toward preventing CDI, efforts should be directed towards identifying factors that can be modified in CDI patients prior to or after hospital discharge.

This study has several limitations. Using an administrative database (such as NIS) has an inherent limitation of coding errors and reporting bias can lead to misclassification of cohort definition (SS) and outcome (CDI). To minimize bias due to coding errors, we used previously validated ICD-9-CM codes and approach to identify individuals with SS and CDI.13-15 Although the SS population was identified with ICD-9-CM codes using an administrative database, the in-hospital mortality for our septic population was similar to previously reported mortality of SS, suggesting the population selected was appropriate.13 SS due to CDI could not be identified; however, CDI by itself causing SS is rare, as described in recent literature.29,30 An important potential bias that needs to be acknowledged is the immortal time bias. The occurrence of CDI in itself can be influenced by pre-CDI hospital LOS. Patients who were extremely sick could have died early in their hospital course before they could acquire CDI, which would influence the mortality difference between the group with CDI and group without CDI. Furthermore, we did not have information on either the treatment of CDI or SS or any measures of severity of illness, which could lead to residual confounding despite adjusting for multiple variables. In terms of readmission data, it was necessary to exclude nonresidents of a state for the 30-day readmission analysis, as readmissions could not be tracked across state boundaries by using the NRD. This might have resulted in an underrepresentation of the readmission burden. Lastly, it was not possible to identify mortality after hospital discharge as the NIS provides only in-hospital mortality.

In conclusion, CDI is more prevalent in SS than are other ICU populations or the hospital population in general, and CDI complicating SS is associated with significant increase in LOS and risk of 30-day hospital readmission. How much of the increase in resource utilization and cost are in fact attributable to CDI in this population remains to be studied. Our finding of high prevalence of CDI in the SS population further emphasizes the importance of maintaining and furthering approaches to reduce incidence of hospital acquired CDI. While reducing unnecessary antibiotics is important, a multipronged approach that includes education and infection control interventions has also been shown to reduce the incidence of CDI in the ICU.31 Given the economic burden of CDI, implementing these strategies to reduce CDI is warranted. Similarly, the risk of 30-day hospital readmission with CDI highlights the importance of identifying the factors that contribute to hospital readmission prior to initial hospital discharge. Programs to reduce CDI will not only improve outcomes directly attributable to CDI but also decrease the reservoir of CDI. Finally, to the extent that CDI can be reduced in the ICU, the utilization of ICU resources will be more effective.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report. Author Contributions: KC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. KC, AG, AC, KK, and HC contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. Guarantor statement: Kshitij Chatterjee takes responsibility for (is the guarantor of) the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

1. Polage CR, Solnick JV, Cohen SH. Nosocomial diarrhea: evaluation and treatment of causes other than Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):982-989. Doi: 10.1093/cid/cis551. PubMed

2. Kyne L, Hamel MB, Polavaram R, Kelly CP. Health care costs and mortality associated with nosocomial diarrhea due to Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(3):346-353. Doi: 10.1086/338260. PubMed

3. Dubberke ER, Olsen MA. Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S88-S92. Doi: 10.1093/cid/cis335. PubMed

4. Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825-834. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. PubMed

5. Zhang S, Palazuelos-Munoz S, Balsells EM, Nair H, Chit A, Kyaw MH. Cost of hospital management of Clostridium difficile infection in United States-a meta-analysis and modelling study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):447. Doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1786-6. PubMed

6. Lessa FC, Gould CV, McDonald LC. Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 2):S65-S70. Doi: 10.1093/cid/cis319. PubMed

7. Depestel DD, Aronoff DM. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(5):464-475. Doi: 10.1177/0897190013499521. PubMed

8. Dial S., Delaney JAC, Barkun AN, Suissa S. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA. 2005;294(23):2989-2995. Doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2989. PubMed

9. Aseeri M., Schroeder T, Kramer J, Zackula R. Gastric acid suppression by proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2308-2313. Doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01975.x. PubMed

10. Cunningham R, Dial S. Is over-use of proton pump inhibitors fuelling the current epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea? J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(1):1-6. Doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.023. PubMed

11. HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed on April 23, 2016.

12. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. PubMed

13. Goto T, Yoshida K, Tsugawa Y, Filbin MR, Camargo CA, Hasegawa K. Mortality trends in U.S. adults with septic shock, 2005-2011: a serial cross-sectional analysis of nationally-representative data. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:294. Doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1620-1. PubMed

14. Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000-2007). Chest. 2011;140(5):1223-1231. Doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0352. PubMed

15. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546-1554. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. PubMed

16. Scheurer DB, Hicks LS, Cook EF, Schnipper JL. Accuracy of ICD-9 coding for Clostridium difficile infections: a retrospective cohort. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(6):1010-1013. Doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007655. PubMed

17. Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas NT, Romney M, Wong H. Length of stay and mortality due to Clostridium difficile infection acquired in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2013;28(4):335-340. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.008. PubMed

18. Bouza E, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Alcalá L, et al. Is Clostridium difficile infection an increasingly common severe disease in adult intensive care units? A 10-year experience. J Crit Care. 2015;30(3):543-549. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.02.011. PubMed

19. Karanika S, Paudel S, Zervou FN, Grigoras C, Zacharioudakis IM, Mylonakis E. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):ofv186. Doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv186. PubMed

20. Zahar JR, Schwebel C, Adrie C, et al. Outcome of ICU patients with Clostridium difficile infection. Crit Care. 2012;16(6):R215. Doi: 10.1186/cc11852. PubMed

21. Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Wang L, Baser O, Yu H. Mortality and costs in clostridium difficile infection among the elderly in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1331-1336. Doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.188. PubMed

22. Micek ST, Schramm G, Morrow L, et al. Clostridium difficile infection: a multicenter study of epidemiology and outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(8):1968-1975. Doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a40d5. PubMed

23. Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Sadigov S, Higgins TL, Kollef MH, Shorr AF. Epidemiology and outcomes of clostridium difficile-associated disease among patients on prolonged acute mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2009;136(3):752-758. Doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0596. PubMed

24. Lagu T, Stefan MS, Haessler S, et al. The impact of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection on outcomes of hospitalized patients with sepsis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(7):411-417. Doi: 10.1002/jhm.2199. PubMed

25. Prescott HC, Dickson RP, Rogers MA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Hospitalization type and subsequent severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(5):581-588. Doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0483OC. PubMed

26. Healthcare-associated Infections (HAI) Progress Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance/progress-report/index.html. Accessed on July 29, 2017.

27. Song X, Bartlett JG, Speck K, Naegeli A, Carroll K, Perl TM. Rising economic impact of clostridium difficile-associated disease in adult hospitalized patient population. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(9):823-828. Doi: 10.1086/588756. PubMed

28. Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Clostridium difficile recurrence is a strong predictor of 30-day rehospitalization among patients in intensive care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(3):273-279. Doi: 10.1017/ice.2014.47. PubMed

29. Loftus KV, Wilson PM. A curiously rare case of septic shock from Clostridium difficile colitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. Doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000496. PubMed

30. Bermejo C, Maseda E, Salgado P, Gabilondo G., Gilsanz F. Septic shock due to a community acquired Clostridium difficile infection. A case study and a review of the literature. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanimvol. 2014;61(4):219-222. PubMed

31. You E, Song H, Cho J, Lee J. Reduction in the incidence of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection through infection control interventions other than the restriction of antimicrobial use. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;22:9-10. 2014. PubMed

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is the most common infectious cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea.1 Development of a CDI during hospitalization is associated with increases in morbidity, mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost.2-5 The prevalence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased dramatically from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s to almost 9 cases per 1000 discharges; however, the CDI rate since 2007 appears to have plateaued.6,7 Antibiotic use has historically been the most important risk factor for acquiring CDI; however, use of acid-suppressing agents, chemotherapy, chronic comorbidities, and healthcare exposure all also increase the risk of CDI.7-10 The elderly (> 65 years of age) are particularly at risk for developing CDI and having worse clinical outcomes with CDI.6,7

Patients with septic shock (SS) often have multiple CDI risk factors (in particular, extensive antibiotic exposure) and thus, represent a population at a particularly high risk for acquiring a CDI during hospitalization. However, little data are available on the prevalence of CDI acquired in patients hospitalized with SS. We sought to determine the national-level temporal trends in the prevalence of CDI in patients with SS and the impact of CDI complicating SS on clinical outcomes between 2007 and 2013.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) for this study. The NIS is a database developed by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).11 It is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States and has been used by researchers and policy makers to analyze national trends in outcomes and healthcare utilization. The NIS database now approximates a 20% stratified sample of all discharges from all participating US hospitals. Sampling weights are provided by the manufacturer and can be used to produce national-level estimates. Following the redesign of the NIS in 2012, new sampling weights were provided for trend analysis for the years prior to 2012 to account for the new design. Every hospitalization is deidentified and converted into one unique entry that provides information on demographics, hospital characteristics, 1 primary and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses, comorbidities, LOS, in-hospital mortality, and procedures performed during stay. The discharge diagnoses are provided in the form of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes.

The NRD is a database developed for HCUP that contains about 35 million discharges each year and supports readmission data analyses. In 2013, the NRD contained data from 21 geographically diverse states, accounting for 49.1% of all US hospitalizations. Diagnosis, comorbidities, and outcomes are presented in a similar manner to NIS.

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study. Data from the NIS between 2007 and 2013 were used for the analysis. Demographic data obtained included age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index,12 hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Cases with information missing on key demographic variables (age, gender, and race) were excluded. Only adults (>18 years of age) were included for the analysis.

SS was identified by either (1) ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for SS (785.52) or (2) presence of vasopressor use (00.17) along with ICD-9-CM codes of sepsis, severe sepsis, septicemia, bacteremia, or fungemia. This approach is consistent with what has been utilized in other studies to identify cases of sepsis or SS from administrative databases.13-15 The appendix provides a complete list of ICD-9-CM codes used in the study. CDI was identified by ICD-9-CM code 008.45 among the secondary diagnosis. This code has been shown to have good accuracy for identifying CDI using administrative data.16 To minimize the inclusion of cases in which a CDI was present at admission, hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of CDI were not included as cases of CDI complicating SS.

We used NRD 2013 for estimating the effect of CDI on 30-day readmission after initial hospitalizations with SS. We used the criteria for index admissions and 30-day readmissions as defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. We excluded patients who died during their index admission, patients with index discharges in December due to a lack of sufficient time to capture 30-day readmissions, and patients with missing information on key variables. We also excluded patients who were not a resident of the state of index hospitalization since readmission across state boundaries could not be identified in NRD. Manufacturer provided sampling weights were used to produce national level estimates. The cases of SS and CDI were identified by ICD-9-CM codes using the methodology described above.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was the total and yearly prevalence of CDI in patients with SS from 2007 to 2013. The secondary outcomes were mortality, LOS, and 30-day readmissions in patients with SS with and without CDI.

Statistical Analysis

Weighted data from NIS were used for all analyses. Demographics, hospital characteristics, and outcomes of all patients with SS were obtained. The prevalence of CDI was calculated for each calendar year. The temporal trends of outcomes (LOS and in-hospital mortality) of patients were plotted for patients with SS with and without CDI. A χ2 test of trend for proportions was used with the Cochran-Armitage test to calculate statistical significance of changes in prevalence. To test for statistical significance of the temporal trends of LOS, a univariate linear regression was used, with calendar year as a covariate. Independent samples t test, a Mann-Whitney U test, and a χ2 test were used to determine statistical significance of parameters between the group with CDI and the group without CDI.

Prolonged LOS was defined either as a LOS > 75th or > 90th percentile of LOS among all patients with SS. To identify if CDI was associated with a prolonged LOS after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was used. Variables included in the regression model were age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index, hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Data on cases were available for all the above covariates except hospital characteristics, such as teaching status, location, and bed size (these were missing for 0.7% of hospitals).

Stata 13.1.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) were used to perform statistical analyses. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 2,031,739 hospitalizations of adults with SS were identified between 2007 and 2013. CDI was present in 166,432 (8.2%) of these patients. Demographic data are displayed in Table 1. CDI was more commonly observed in elderly patients (> 65 years) with SS; 9.3% among the elderly versus 6.6% among individuals < 65 years; P < 0.001. The prevalence of CDI was greater in urban than in rural hospitals (8.4% vs 5.4%; P < 0.001) and greater in teaching than in nonteaching hospitals (8.7% vs 7.7%; P < 0.001). The prevalence of CDI in SS remained stable between 2007 and 2013 (Table 2).

Mortality

In the overall study cohort, the in-hospital mortality for SS was 37%. The in-hospital mortality rate of patients with SS complicated by a CDI was comparable to the mortality rate of patients without a CDI (37.1% vs 37.0%; P = 0.48). The mortality of patients with SS, with or without CDI, progressively decreased from 2007 to 2013 (P value for trend < 0.001 for each group; Figure 1).

Length of Stay

The median LOS for all patients with SS was 9 days. Patients with CDI had a longer median LOS than did those without CDI (13 vs 9 days; P < 0.001). Between 2007 and 2013, the median LOS of CDI group decreased from 14 to 12 days (P < 0.001) while that of non-CDI group decreased from 9 to 8 days (P < 0.001; Figure 2). We also examined LOS among subgroups who were discharged alive and those who died during hospitalization. For patients who were discharged alive, the LOS with and without CDI was 15 days versus 10 days, respectively (P < 0.001). For patients who died during hospitalization, LOS with and without CDI was 10 days versus 6 days, respectively (P < 0.001).

The 75th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 17 days. An LOS > 17 days was observed in 36.9% of SS patients with CDI versus 22.7% without CDI (P < 0.001). After adjusting for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 17 days were significantly greater for SS patients with CDI (odds ratio [OR] 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.06-2.15; P < 0.001).

The 90th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 29 days. An LOS > 29 days was observed in 17.5% of SS patients with a CDI versus 9.1% without a CDI (P < 0.001). After adjustment for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 29 days were significantly greater for SS patients with a CDI (OR 2.25; 95% CI, 2.22-2.28; P < 0.001).

Hospital Readmission

In 2013, patients with SS and CDI had a higher rate of 30-day readmission as compared to patients with SS without CDI (9.8% vs 7.4% respectively; P < 0.001). The multivariate adjusted OR for 30-day readmission for patients with SS and a CDI was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.22-1.31; P < 0.001).

Additional Analyses

Lastly, we performed an additional analysis to confirm our hypothesis that a CDI by itself is rarely a cause of SS, and that CDI as the principal diagnosis would constitute an extremely low number of patients with SS in an administrative dataset. In NIS 2013, there were 105,750 cases with CDI as the primary diagnosis. A total of 4470 (4.2%) had a secondary diagnosis of sepsis and only 930 (0.9%) cases had a secondary diagnosis of SS.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on the prevalence and outcome of CDI complicating SS. By using a large nationally representative sample, we found CDI was very prevalent among individuals hospitalized with SS and, at a level in excess of that seen in other populations. Of interest, we did not observe an increase in mortality of SS when complicated by CDI. On the other hand, patients with SS complicated by CDI were more much likely to have a prolonged hospital LOS and a higher risk of 30-day hospital readmission.

The prevalence of CDI exploded between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, including community, hospital, and intensive care unit (ICU)–related disease.6,7,17-20 Patients with SS often have multiple risk factors associated with CDI and thus represent a high-risk population for developing CDI.7 Our findings are consistent with the suggestion that individuals with SS are at a higher risk of developing CDI. Compared to the rate of CDI in all hospitalized patients, our data suggest an almost 10-fold increase in CDI rate for patients with SS.6 Patients with SS and CDI may account for as much as 10% of total CDIs.6,7 As has been reported for CDI in general, we observed that CDI complicating SS was more common in those > 65 years of age.4,21 The prevalence of CDI we observed in patients with SS was also higher than has been reported in ICU patients in general (1%), and higher than reported for patients requiring mechanical ventilation (6.6%), including prolonged mechanical ventilation (5.3%); further supporting the conclusion that patients with SS are a particularly high-risk group for acquiring CDI, even compared with other ICU patients.20,22,23 Similarly, the rate of CDI among SS was 8 times higher than that of recently reported hospital-onset CDI among patients with sepsis in general (incidence 1.08%).24 We have no data regarding why patients with SS have a higher rate of CDI; however, the intensity and duration of antibiotic treatment of these patients may certainly play a role.25 It has recently been reported that CDI in itself can be a precursor leading to intestinal dysbiosis that can increase the risk of subsequent sepsis. Similarly, patients with SS may have higher prevalence of dysbiosis that, in turn, might predispose them to CDI at a higher rate than other individuals.

Following the increase in CDIs in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, since 2007 the overall prevalence of CDIs has been stable, albeit at the higher rate. More recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported a decrease in hospital onset CDI after 2011.26

The finding that CDI in SS patients was not associated with an increase in mortality is consistent with other reports of CDI in ICU patients in general as well as higher-risk ICU populations such as patients requiring mechanical ventilation, including those on long-term mechanical ventilator support.17,18,20,22,23 Why the mortality of ICU patients with CDI is not increased is not completely clear. It has been suggested that this may be related to early recognition and treatment of CDI developing in the ICU.22 Along these lines, it has been previously observed that for patients with CDI on mechanical ventilation, patients who were transferred to the ICU from the ward had worse clinical outcomes compared to patients directly admitted to the ICU, likely due to delayed recognition and treatment in the former.22 Similarly, ICU patients in whom CDI was identified prior to ICU admission had more severe CDI, and mortality that was directly related to CDI was only observed in patients who had CDI identified pre-ICU transfer.18 The increase in mortality observed in patients with sepsis in general with CDI may reflect similar factors.24 We observed a trend of decreasing mortality in SS patients with or without CDI during 2007 to 2013 consistent to what has been generally reported in SS.13,14

The increase in LOS observed in SS patients with CDI is also consistent with what has been observed in other ICU populations, as well as in patients with sepsis in general.17,22-24 Of note, in addition to the increase in median LOS, we found a significant increase in the number of patients with a prolonged LOS associated with having SS with CDI. It is important to note that development of CDI during hospitalization is affected by pre-CDI hospital LOS, so prolonged LOS may not be solely attributable to CDI. The interaction between LOS and CDI remains complex in which higher LOS might be associated with higher incidence of CDI occurrence, and once established, CDI might be associated with changes in LOS for the remaining hospitalization.

Hospitalized patients with CDI have an overall higher resource utilization than those without CDI.27 A recent review has estimated the overall attributable cost of CDI to be $6.3 billion; the attributable cost per case of hospital acquired CDI being 1.5 times the cost of community-acquired CDI.5 We did not look at cost directly. However, in the high-CDI risk ICU population requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation, those with CDI had a substantial increase in total costs.23 Given the substantial increase in LOS associated with CDI complicating SS, there would likely be a significant increase in hospital costs related to providing care for these patients. Further adding to the potential burden of CDI is our finding that CDI and SS was associated with an increase in 30-day hospital readmission rate. This is consistent with a recent report that ICU patients with CDI who are discharged from the hospital have a 25% 30-day hospital readmission rate.28 However, we do not have data either as to the reason for hospital readmission or whether the initial CDI or CDI recurrence played a role. This suggests that, in addition to intervention directed toward preventing CDI, efforts should be directed towards identifying factors that can be modified in CDI patients prior to or after hospital discharge.

This study has several limitations. Using an administrative database (such as NIS) has an inherent limitation of coding errors and reporting bias can lead to misclassification of cohort definition (SS) and outcome (CDI). To minimize bias due to coding errors, we used previously validated ICD-9-CM codes and approach to identify individuals with SS and CDI.13-15 Although the SS population was identified with ICD-9-CM codes using an administrative database, the in-hospital mortality for our septic population was similar to previously reported mortality of SS, suggesting the population selected was appropriate.13 SS due to CDI could not be identified; however, CDI by itself causing SS is rare, as described in recent literature.29,30 An important potential bias that needs to be acknowledged is the immortal time bias. The occurrence of CDI in itself can be influenced by pre-CDI hospital LOS. Patients who were extremely sick could have died early in their hospital course before they could acquire CDI, which would influence the mortality difference between the group with CDI and group without CDI. Furthermore, we did not have information on either the treatment of CDI or SS or any measures of severity of illness, which could lead to residual confounding despite adjusting for multiple variables. In terms of readmission data, it was necessary to exclude nonresidents of a state for the 30-day readmission analysis, as readmissions could not be tracked across state boundaries by using the NRD. This might have resulted in an underrepresentation of the readmission burden. Lastly, it was not possible to identify mortality after hospital discharge as the NIS provides only in-hospital mortality.

In conclusion, CDI is more prevalent in SS than are other ICU populations or the hospital population in general, and CDI complicating SS is associated with significant increase in LOS and risk of 30-day hospital readmission. How much of the increase in resource utilization and cost are in fact attributable to CDI in this population remains to be studied. Our finding of high prevalence of CDI in the SS population further emphasizes the importance of maintaining and furthering approaches to reduce incidence of hospital acquired CDI. While reducing unnecessary antibiotics is important, a multipronged approach that includes education and infection control interventions has also been shown to reduce the incidence of CDI in the ICU.31 Given the economic burden of CDI, implementing these strategies to reduce CDI is warranted. Similarly, the risk of 30-day hospital readmission with CDI highlights the importance of identifying the factors that contribute to hospital readmission prior to initial hospital discharge. Programs to reduce CDI will not only improve outcomes directly attributable to CDI but also decrease the reservoir of CDI. Finally, to the extent that CDI can be reduced in the ICU, the utilization of ICU resources will be more effective.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report. Author Contributions: KC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. KC, AG, AC, KK, and HC contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. Guarantor statement: Kshitij Chatterjee takes responsibility for (is the guarantor of) the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is the most common infectious cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea.1 Development of a CDI during hospitalization is associated with increases in morbidity, mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost.2-5 The prevalence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased dramatically from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s to almost 9 cases per 1000 discharges; however, the CDI rate since 2007 appears to have plateaued.6,7 Antibiotic use has historically been the most important risk factor for acquiring CDI; however, use of acid-suppressing agents, chemotherapy, chronic comorbidities, and healthcare exposure all also increase the risk of CDI.7-10 The elderly (> 65 years of age) are particularly at risk for developing CDI and having worse clinical outcomes with CDI.6,7

Patients with septic shock (SS) often have multiple CDI risk factors (in particular, extensive antibiotic exposure) and thus, represent a population at a particularly high risk for acquiring a CDI during hospitalization. However, little data are available on the prevalence of CDI acquired in patients hospitalized with SS. We sought to determine the national-level temporal trends in the prevalence of CDI in patients with SS and the impact of CDI complicating SS on clinical outcomes between 2007 and 2013.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) for this study. The NIS is a database developed by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).11 It is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States and has been used by researchers and policy makers to analyze national trends in outcomes and healthcare utilization. The NIS database now approximates a 20% stratified sample of all discharges from all participating US hospitals. Sampling weights are provided by the manufacturer and can be used to produce national-level estimates. Following the redesign of the NIS in 2012, new sampling weights were provided for trend analysis for the years prior to 2012 to account for the new design. Every hospitalization is deidentified and converted into one unique entry that provides information on demographics, hospital characteristics, 1 primary and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses, comorbidities, LOS, in-hospital mortality, and procedures performed during stay. The discharge diagnoses are provided in the form of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes.

The NRD is a database developed for HCUP that contains about 35 million discharges each year and supports readmission data analyses. In 2013, the NRD contained data from 21 geographically diverse states, accounting for 49.1% of all US hospitalizations. Diagnosis, comorbidities, and outcomes are presented in a similar manner to NIS.

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study. Data from the NIS between 2007 and 2013 were used for the analysis. Demographic data obtained included age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index,12 hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Cases with information missing on key demographic variables (age, gender, and race) were excluded. Only adults (>18 years of age) were included for the analysis.

SS was identified by either (1) ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for SS (785.52) or (2) presence of vasopressor use (00.17) along with ICD-9-CM codes of sepsis, severe sepsis, septicemia, bacteremia, or fungemia. This approach is consistent with what has been utilized in other studies to identify cases of sepsis or SS from administrative databases.13-15 The appendix provides a complete list of ICD-9-CM codes used in the study. CDI was identified by ICD-9-CM code 008.45 among the secondary diagnosis. This code has been shown to have good accuracy for identifying CDI using administrative data.16 To minimize the inclusion of cases in which a CDI was present at admission, hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of CDI were not included as cases of CDI complicating SS.

We used NRD 2013 for estimating the effect of CDI on 30-day readmission after initial hospitalizations with SS. We used the criteria for index admissions and 30-day readmissions as defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. We excluded patients who died during their index admission, patients with index discharges in December due to a lack of sufficient time to capture 30-day readmissions, and patients with missing information on key variables. We also excluded patients who were not a resident of the state of index hospitalization since readmission across state boundaries could not be identified in NRD. Manufacturer provided sampling weights were used to produce national level estimates. The cases of SS and CDI were identified by ICD-9-CM codes using the methodology described above.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was the total and yearly prevalence of CDI in patients with SS from 2007 to 2013. The secondary outcomes were mortality, LOS, and 30-day readmissions in patients with SS with and without CDI.

Statistical Analysis

Weighted data from NIS were used for all analyses. Demographics, hospital characteristics, and outcomes of all patients with SS were obtained. The prevalence of CDI was calculated for each calendar year. The temporal trends of outcomes (LOS and in-hospital mortality) of patients were plotted for patients with SS with and without CDI. A χ2 test of trend for proportions was used with the Cochran-Armitage test to calculate statistical significance of changes in prevalence. To test for statistical significance of the temporal trends of LOS, a univariate linear regression was used, with calendar year as a covariate. Independent samples t test, a Mann-Whitney U test, and a χ2 test were used to determine statistical significance of parameters between the group with CDI and the group without CDI.

Prolonged LOS was defined either as a LOS > 75th or > 90th percentile of LOS among all patients with SS. To identify if CDI was associated with a prolonged LOS after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was used. Variables included in the regression model were age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index, hospital characteristics (hospital region, hospital-bed size, urban versus rural location, and teaching status), calendar year, and use of mechanical ventilation. Data on cases were available for all the above covariates except hospital characteristics, such as teaching status, location, and bed size (these were missing for 0.7% of hospitals).

Stata 13.1.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) were used to perform statistical analyses. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 2,031,739 hospitalizations of adults with SS were identified between 2007 and 2013. CDI was present in 166,432 (8.2%) of these patients. Demographic data are displayed in Table 1. CDI was more commonly observed in elderly patients (> 65 years) with SS; 9.3% among the elderly versus 6.6% among individuals < 65 years; P < 0.001. The prevalence of CDI was greater in urban than in rural hospitals (8.4% vs 5.4%; P < 0.001) and greater in teaching than in nonteaching hospitals (8.7% vs 7.7%; P < 0.001). The prevalence of CDI in SS remained stable between 2007 and 2013 (Table 2).

Mortality

In the overall study cohort, the in-hospital mortality for SS was 37%. The in-hospital mortality rate of patients with SS complicated by a CDI was comparable to the mortality rate of patients without a CDI (37.1% vs 37.0%; P = 0.48). The mortality of patients with SS, with or without CDI, progressively decreased from 2007 to 2013 (P value for trend < 0.001 for each group; Figure 1).

Length of Stay

The median LOS for all patients with SS was 9 days. Patients with CDI had a longer median LOS than did those without CDI (13 vs 9 days; P < 0.001). Between 2007 and 2013, the median LOS of CDI group decreased from 14 to 12 days (P < 0.001) while that of non-CDI group decreased from 9 to 8 days (P < 0.001; Figure 2). We also examined LOS among subgroups who were discharged alive and those who died during hospitalization. For patients who were discharged alive, the LOS with and without CDI was 15 days versus 10 days, respectively (P < 0.001). For patients who died during hospitalization, LOS with and without CDI was 10 days versus 6 days, respectively (P < 0.001).

The 75th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 17 days. An LOS > 17 days was observed in 36.9% of SS patients with CDI versus 22.7% without CDI (P < 0.001). After adjusting for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 17 days were significantly greater for SS patients with CDI (odds ratio [OR] 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.06-2.15; P < 0.001).

The 90th percentile of LOS of the total SS cohort was 29 days. An LOS > 29 days was observed in 17.5% of SS patients with a CDI versus 9.1% without a CDI (P < 0.001). After adjustment for patient and provider level variables, the odds of a LOS > 29 days were significantly greater for SS patients with a CDI (OR 2.25; 95% CI, 2.22-2.28; P < 0.001).

Hospital Readmission

In 2013, patients with SS and CDI had a higher rate of 30-day readmission as compared to patients with SS without CDI (9.8% vs 7.4% respectively; P < 0.001). The multivariate adjusted OR for 30-day readmission for patients with SS and a CDI was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.22-1.31; P < 0.001).

Additional Analyses

Lastly, we performed an additional analysis to confirm our hypothesis that a CDI by itself is rarely a cause of SS, and that CDI as the principal diagnosis would constitute an extremely low number of patients with SS in an administrative dataset. In NIS 2013, there were 105,750 cases with CDI as the primary diagnosis. A total of 4470 (4.2%) had a secondary diagnosis of sepsis and only 930 (0.9%) cases had a secondary diagnosis of SS.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on the prevalence and outcome of CDI complicating SS. By using a large nationally representative sample, we found CDI was very prevalent among individuals hospitalized with SS and, at a level in excess of that seen in other populations. Of interest, we did not observe an increase in mortality of SS when complicated by CDI. On the other hand, patients with SS complicated by CDI were more much likely to have a prolonged hospital LOS and a higher risk of 30-day hospital readmission.

The prevalence of CDI exploded between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, including community, hospital, and intensive care unit (ICU)–related disease.6,7,17-20 Patients with SS often have multiple risk factors associated with CDI and thus represent a high-risk population for developing CDI.7 Our findings are consistent with the suggestion that individuals with SS are at a higher risk of developing CDI. Compared to the rate of CDI in all hospitalized patients, our data suggest an almost 10-fold increase in CDI rate for patients with SS.6 Patients with SS and CDI may account for as much as 10% of total CDIs.6,7 As has been reported for CDI in general, we observed that CDI complicating SS was more common in those > 65 years of age.4,21 The prevalence of CDI we observed in patients with SS was also higher than has been reported in ICU patients in general (1%), and higher than reported for patients requiring mechanical ventilation (6.6%), including prolonged mechanical ventilation (5.3%); further supporting the conclusion that patients with SS are a particularly high-risk group for acquiring CDI, even compared with other ICU patients.20,22,23 Similarly, the rate of CDI among SS was 8 times higher than that of recently reported hospital-onset CDI among patients with sepsis in general (incidence 1.08%).24 We have no data regarding why patients with SS have a higher rate of CDI; however, the intensity and duration of antibiotic treatment of these patients may certainly play a role.25 It has recently been reported that CDI in itself can be a precursor leading to intestinal dysbiosis that can increase the risk of subsequent sepsis. Similarly, patients with SS may have higher prevalence of dysbiosis that, in turn, might predispose them to CDI at a higher rate than other individuals.

Following the increase in CDIs in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, since 2007 the overall prevalence of CDIs has been stable, albeit at the higher rate. More recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported a decrease in hospital onset CDI after 2011.26

The finding that CDI in SS patients was not associated with an increase in mortality is consistent with other reports of CDI in ICU patients in general as well as higher-risk ICU populations such as patients requiring mechanical ventilation, including those on long-term mechanical ventilator support.17,18,20,22,23 Why the mortality of ICU patients with CDI is not increased is not completely clear. It has been suggested that this may be related to early recognition and treatment of CDI developing in the ICU.22 Along these lines, it has been previously observed that for patients with CDI on mechanical ventilation, patients who were transferred to the ICU from the ward had worse clinical outcomes compared to patients directly admitted to the ICU, likely due to delayed recognition and treatment in the former.22 Similarly, ICU patients in whom CDI was identified prior to ICU admission had more severe CDI, and mortality that was directly related to CDI was only observed in patients who had CDI identified pre-ICU transfer.18 The increase in mortality observed in patients with sepsis in general with CDI may reflect similar factors.24 We observed a trend of decreasing mortality in SS patients with or without CDI during 2007 to 2013 consistent to what has been generally reported in SS.13,14

The increase in LOS observed in SS patients with CDI is also consistent with what has been observed in other ICU populations, as well as in patients with sepsis in general.17,22-24 Of note, in addition to the increase in median LOS, we found a significant increase in the number of patients with a prolonged LOS associated with having SS with CDI. It is important to note that development of CDI during hospitalization is affected by pre-CDI hospital LOS, so prolonged LOS may not be solely attributable to CDI. The interaction between LOS and CDI remains complex in which higher LOS might be associated with higher incidence of CDI occurrence, and once established, CDI might be associated with changes in LOS for the remaining hospitalization.

Hospitalized patients with CDI have an overall higher resource utilization than those without CDI.27 A recent review has estimated the overall attributable cost of CDI to be $6.3 billion; the attributable cost per case of hospital acquired CDI being 1.5 times the cost of community-acquired CDI.5 We did not look at cost directly. However, in the high-CDI risk ICU population requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation, those with CDI had a substantial increase in total costs.23 Given the substantial increase in LOS associated with CDI complicating SS, there would likely be a significant increase in hospital costs related to providing care for these patients. Further adding to the potential burden of CDI is our finding that CDI and SS was associated with an increase in 30-day hospital readmission rate. This is consistent with a recent report that ICU patients with CDI who are discharged from the hospital have a 25% 30-day hospital readmission rate.28 However, we do not have data either as to the reason for hospital readmission or whether the initial CDI or CDI recurrence played a role. This suggests that, in addition to intervention directed toward preventing CDI, efforts should be directed towards identifying factors that can be modified in CDI patients prior to or after hospital discharge.

This study has several limitations. Using an administrative database (such as NIS) has an inherent limitation of coding errors and reporting bias can lead to misclassification of cohort definition (SS) and outcome (CDI). To minimize bias due to coding errors, we used previously validated ICD-9-CM codes and approach to identify individuals with SS and CDI.13-15 Although the SS population was identified with ICD-9-CM codes using an administrative database, the in-hospital mortality for our septic population was similar to previously reported mortality of SS, suggesting the population selected was appropriate.13 SS due to CDI could not be identified; however, CDI by itself causing SS is rare, as described in recent literature.29,30 An important potential bias that needs to be acknowledged is the immortal time bias. The occurrence of CDI in itself can be influenced by pre-CDI hospital LOS. Patients who were extremely sick could have died early in their hospital course before they could acquire CDI, which would influence the mortality difference between the group with CDI and group without CDI. Furthermore, we did not have information on either the treatment of CDI or SS or any measures of severity of illness, which could lead to residual confounding despite adjusting for multiple variables. In terms of readmission data, it was necessary to exclude nonresidents of a state for the 30-day readmission analysis, as readmissions could not be tracked across state boundaries by using the NRD. This might have resulted in an underrepresentation of the readmission burden. Lastly, it was not possible to identify mortality after hospital discharge as the NIS provides only in-hospital mortality.

In conclusion, CDI is more prevalent in SS than are other ICU populations or the hospital population in general, and CDI complicating SS is associated with significant increase in LOS and risk of 30-day hospital readmission. How much of the increase in resource utilization and cost are in fact attributable to CDI in this population remains to be studied. Our finding of high prevalence of CDI in the SS population further emphasizes the importance of maintaining and furthering approaches to reduce incidence of hospital acquired CDI. While reducing unnecessary antibiotics is important, a multipronged approach that includes education and infection control interventions has also been shown to reduce the incidence of CDI in the ICU.31 Given the economic burden of CDI, implementing these strategies to reduce CDI is warranted. Similarly, the risk of 30-day hospital readmission with CDI highlights the importance of identifying the factors that contribute to hospital readmission prior to initial hospital discharge. Programs to reduce CDI will not only improve outcomes directly attributable to CDI but also decrease the reservoir of CDI. Finally, to the extent that CDI can be reduced in the ICU, the utilization of ICU resources will be more effective.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report. Author Contributions: KC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. KC, AG, AC, KK, and HC contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. Guarantor statement: Kshitij Chatterjee takes responsibility for (is the guarantor of) the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

1. Polage CR, Solnick JV, Cohen SH. Nosocomial diarrhea: evaluation and treatment of causes other than Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):982-989. Doi: 10.1093/cid/cis551. PubMed

2. Kyne L, Hamel MB, Polavaram R, Kelly CP. Health care costs and mortality associated with nosocomial diarrhea due to Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(3):346-353. Doi: 10.1086/338260. PubMed