User login

Pooled Analysis Clarifies VNS Efficacy in Cluster Headache

BOSTON—Noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is well tolerated and effectively aborts episodic cluster headache attacks, according to a pooled analysis described at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. The treatment does not effectively abort attacks in chronic cluster headache, however.

A Pooled Analysis of Two Trials

He and his colleagues studied ElectroCore's gammaCore noninvasive VNS device as an acute treatment of cluster headache in the double-blind, randomized, controlled ACT1 and ACT2 trials. Each trial included more than 100 patients with episodic or chronic cluster headache. The two studies took place at 20 centers in the United States and nine centers in the United Kingdom and Europe.

Treatment was delivered on the patient's right side in ACT1, and on the side ipsilateral to the attack in ACT2. In ACT1, patients were allowed three stimulations, or a total of six minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT2, patients were permitted as many as six stimulations, representing 12 minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT1, the primary end point was response rate (ie, the proportion of patients who achieved pain relief at 15 minutes). The primary end point in ACT2 was pain freedom at 15 minutes, and a secondary end point was the 50% responder rate (ie, mild or no pain) at 15 minutes.

Each study was underpowered for an analysis of results according to headache frequency, so the investigators performed a pooled analysis of the two studies. This examination included a fixed-effects meta-analysis and a first-order interaction test between the treatment group and the cluster headache subgroup to determine whether the magnitude of treatment effect varied significantly by cluster headache subtype.

In all, 253 patients were included in the pooled analysis, 131 of whom had episodic cluster headache, and 122 of whom had chronic cluster headache. Patients' mean age was 46.6. Approximately 21% of patients were female, 2.4% were Asian, and 4.7% were black.

Efficacy in Episodic, But Not Chronic Cluster Headache

Among patients with episodic cluster headache, the rate of pain freedom for all treated attacks at 15 minutes was significantly higher with VNS than with sham (15% vs 6% in ACT1, 35% vs 7% in ACT2, and 24% vs 7% in the pooled analysis). Among patients with chronic cluster headache, the researchers did not find significant differences in this end point between treatment groups (5% vs 14% in ACT1, 7% vs 9% in ACT2, and 7% vs 11% in the pooled analysis).

For patients with episodic cluster headache, the 50% responder rate was 34% in ACT1, 64% in ACT2, and 42% in the pooled analysis. For patients with chronic cluster headache, the responder rates were 13.6% in ACT1, 29.4% in ACT2, and 23.2% in the pooled analysis. For the proportion of attacks that became pain free, the interaction test was significant for ACT1 and the pooled analysis, but it was not significant for ACT2. For the 50% responder end point, the interaction test was significant for ACT1, ACT2, and the pooled analysis.

In April 2017, the FDA cleared the gammaCore device for the acute treatment of pain associated with episodic cluster headache in adults. The device is now available in the US, said Mr. Liebler.

“We are going to continue to examine the mechanism of action [of noninvasive VNS] and the reasons for possible [treatment] failure in chronic cluster headache,” said Mr. Liebler. These investigations could provide further clinical insight and clarify the pathogenesis of cluster headache, he added.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Silberstein SD, Mechtler LL, Kudrow DB, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for the acute treatment of cluster headache: findings from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled ACT1 study. Headache. 2016;56(8):1317-1332.

BOSTON—Noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is well tolerated and effectively aborts episodic cluster headache attacks, according to a pooled analysis described at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. The treatment does not effectively abort attacks in chronic cluster headache, however.

A Pooled Analysis of Two Trials

He and his colleagues studied ElectroCore's gammaCore noninvasive VNS device as an acute treatment of cluster headache in the double-blind, randomized, controlled ACT1 and ACT2 trials. Each trial included more than 100 patients with episodic or chronic cluster headache. The two studies took place at 20 centers in the United States and nine centers in the United Kingdom and Europe.

Treatment was delivered on the patient's right side in ACT1, and on the side ipsilateral to the attack in ACT2. In ACT1, patients were allowed three stimulations, or a total of six minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT2, patients were permitted as many as six stimulations, representing 12 minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT1, the primary end point was response rate (ie, the proportion of patients who achieved pain relief at 15 minutes). The primary end point in ACT2 was pain freedom at 15 minutes, and a secondary end point was the 50% responder rate (ie, mild or no pain) at 15 minutes.

Each study was underpowered for an analysis of results according to headache frequency, so the investigators performed a pooled analysis of the two studies. This examination included a fixed-effects meta-analysis and a first-order interaction test between the treatment group and the cluster headache subgroup to determine whether the magnitude of treatment effect varied significantly by cluster headache subtype.

In all, 253 patients were included in the pooled analysis, 131 of whom had episodic cluster headache, and 122 of whom had chronic cluster headache. Patients' mean age was 46.6. Approximately 21% of patients were female, 2.4% were Asian, and 4.7% were black.

Efficacy in Episodic, But Not Chronic Cluster Headache

Among patients with episodic cluster headache, the rate of pain freedom for all treated attacks at 15 minutes was significantly higher with VNS than with sham (15% vs 6% in ACT1, 35% vs 7% in ACT2, and 24% vs 7% in the pooled analysis). Among patients with chronic cluster headache, the researchers did not find significant differences in this end point between treatment groups (5% vs 14% in ACT1, 7% vs 9% in ACT2, and 7% vs 11% in the pooled analysis).

For patients with episodic cluster headache, the 50% responder rate was 34% in ACT1, 64% in ACT2, and 42% in the pooled analysis. For patients with chronic cluster headache, the responder rates were 13.6% in ACT1, 29.4% in ACT2, and 23.2% in the pooled analysis. For the proportion of attacks that became pain free, the interaction test was significant for ACT1 and the pooled analysis, but it was not significant for ACT2. For the 50% responder end point, the interaction test was significant for ACT1, ACT2, and the pooled analysis.

In April 2017, the FDA cleared the gammaCore device for the acute treatment of pain associated with episodic cluster headache in adults. The device is now available in the US, said Mr. Liebler.

“We are going to continue to examine the mechanism of action [of noninvasive VNS] and the reasons for possible [treatment] failure in chronic cluster headache,” said Mr. Liebler. These investigations could provide further clinical insight and clarify the pathogenesis of cluster headache, he added.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Silberstein SD, Mechtler LL, Kudrow DB, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for the acute treatment of cluster headache: findings from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled ACT1 study. Headache. 2016;56(8):1317-1332.

BOSTON—Noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is well tolerated and effectively aborts episodic cluster headache attacks, according to a pooled analysis described at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. The treatment does not effectively abort attacks in chronic cluster headache, however.

A Pooled Analysis of Two Trials

He and his colleagues studied ElectroCore's gammaCore noninvasive VNS device as an acute treatment of cluster headache in the double-blind, randomized, controlled ACT1 and ACT2 trials. Each trial included more than 100 patients with episodic or chronic cluster headache. The two studies took place at 20 centers in the United States and nine centers in the United Kingdom and Europe.

Treatment was delivered on the patient's right side in ACT1, and on the side ipsilateral to the attack in ACT2. In ACT1, patients were allowed three stimulations, or a total of six minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT2, patients were permitted as many as six stimulations, representing 12 minutes of treatment per attack. In ACT1, the primary end point was response rate (ie, the proportion of patients who achieved pain relief at 15 minutes). The primary end point in ACT2 was pain freedom at 15 minutes, and a secondary end point was the 50% responder rate (ie, mild or no pain) at 15 minutes.

Each study was underpowered for an analysis of results according to headache frequency, so the investigators performed a pooled analysis of the two studies. This examination included a fixed-effects meta-analysis and a first-order interaction test between the treatment group and the cluster headache subgroup to determine whether the magnitude of treatment effect varied significantly by cluster headache subtype.

In all, 253 patients were included in the pooled analysis, 131 of whom had episodic cluster headache, and 122 of whom had chronic cluster headache. Patients' mean age was 46.6. Approximately 21% of patients were female, 2.4% were Asian, and 4.7% were black.

Efficacy in Episodic, But Not Chronic Cluster Headache

Among patients with episodic cluster headache, the rate of pain freedom for all treated attacks at 15 minutes was significantly higher with VNS than with sham (15% vs 6% in ACT1, 35% vs 7% in ACT2, and 24% vs 7% in the pooled analysis). Among patients with chronic cluster headache, the researchers did not find significant differences in this end point between treatment groups (5% vs 14% in ACT1, 7% vs 9% in ACT2, and 7% vs 11% in the pooled analysis).

For patients with episodic cluster headache, the 50% responder rate was 34% in ACT1, 64% in ACT2, and 42% in the pooled analysis. For patients with chronic cluster headache, the responder rates were 13.6% in ACT1, 29.4% in ACT2, and 23.2% in the pooled analysis. For the proportion of attacks that became pain free, the interaction test was significant for ACT1 and the pooled analysis, but it was not significant for ACT2. For the 50% responder end point, the interaction test was significant for ACT1, ACT2, and the pooled analysis.

In April 2017, the FDA cleared the gammaCore device for the acute treatment of pain associated with episodic cluster headache in adults. The device is now available in the US, said Mr. Liebler.

“We are going to continue to examine the mechanism of action [of noninvasive VNS] and the reasons for possible [treatment] failure in chronic cluster headache,” said Mr. Liebler. These investigations could provide further clinical insight and clarify the pathogenesis of cluster headache, he added.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Silberstein SD, Mechtler LL, Kudrow DB, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for the acute treatment of cluster headache: findings from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled ACT1 study. Headache. 2016;56(8):1317-1332.

Studies backing certain FDA approvals found lacking

, two studies showed.

Between 2009 and 2013, the FDA granted accelerated approval for 22 drugs with 24 indications, which were supported by 30 preapproval studies with a median of 132 subjects. Only 12 of those studies (40%) were randomized, and only 6 (20%) were double blind. Eight (27%) included fewer than 100 subjects, and 20 (67%) included fewer than 200, reported Huseyin Naci, PhD, of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and his colleagues.

Further, at a minimum of 3 years after the approval, only half of the 38 confirmatory studies required by the FDA were completed, and, ultimately, only 25 of the 48 (66%) examined clinical efficacy, only 7 (18%) evaluated longer follow-up, and only 6 (16%) focused on safety, the investigators reported (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:626-36).

The proportion of studies that were randomized was slightly, but not significantly greater in the postapproval vs. preapproval period (56% vs. 40%), and only one was double blind. For 10 of 24 indications (42%), postapproval study requirements were completed and demonstrated efficacy based on surrogate measures, the investigators said.

Of the 14 remaining indications (58%) for which FDA study requirements had not yet been met, 2 (8%) had at least one confirmatory study that failed to demonstrate clinical benefit (without apparent action on the part of the FDA to rescind approval or impose additional requirements), 2 (8%) had a least one confirmatory study that was terminated, and 3 (13%) had at least one confirmatory study that was delayed by more than a year. The required studies for the remaining indications were progressing as planned, but for eight indications, clinical benefit had not yet been confirmed at 5 or more years after approval.

Similar concerns were seen in a review of clinical studies used to support high-risk medical device modification approvals. Such devices often undergo numerous modifications that receive FDA approval through one of six premarket approval (PMA) supplement pathways, and a total of 83 studies that supported 78 panel-track supplements (one of the 6 pathways and the only one that always required clinical data) approved between April 19, 2006, and Oct. 9, 2015, were identified. Nearly all (98%) of those 78 modifications were supported by just one study; only 45% of those studies were randomized clinical trials, and only 30% were blinded, reported Sarah Y. Zheng, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:619-25).

The median number of patients in the studies was 185, and the median follow-up was 180 days. Further, of 150 primary endpoints in the studies, 121 (81%) were surrogate endpoints, 57 (38%) were compared with controls, and 6 (11%) of those involved retrospective rather than active controls.

Age and sex were not reported for all enrolled patients in 40% and 30% of the studies, respectively, and in the case of one device modification study, 91% of enrolled patients were not included in the primary analysis.

“Given the extensive modification of many PMA supplement devices and the median preapproval follow-up of 6 months, obtaining additional data via [postapproval studies] is critical. However, the FDA required [postapproval studies] for the minority (37%) of the panel-track supplements,” the investigators noted, adding that only 13% of initiated postapproval studies were completed between 3 and 5 years after FDA approval, and that no warning letters, penalties, or fines were administered for noncompliance.

“These findings suggest that the quality of studies and data evaluated to support approval by the FDA of modifications of high-risk devices should be improved,” they concluded.

Dr. Zheng and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Naci reported having no conflicts of interest. One coauthor, Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, reported receiving unrelated grants from the FDA Office of Generic Drugs and Division of Health Communication.

The findings by Naci and colleagues and Zheng and colleagues raise concerns about whether the current regulatory system is too permissive in not requiring traditional randomized controlled trials for postmarketing evaluation of drugs that receive accelerated approval, and for high-risk medical device supplemental design modifications, Robert Califf, MD, wrote in an editorial.

However, randomization and blinding are not always feasible, and “despite the concerns raised by these two articles … it is important to remember that decisions about postmarket requirements and monitoring of these studies are overseen by full-time FDA employees with no financial conflicts,” he said, adding that “this underscores the importance of a talented workforce at the FDA with the variety of skills needed to assimilate information about manufacturing, quality systems, clinical outcomes, and the well-being and preferences of patients.”

A sweeping overhaul of the overall system is also needed, and is underway, he said, noting that substantial progress in balancing safety with access to effective therapies will come from systemic changes in the ecosystem rather than from imposing more severe demands on individual products (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:614-6).

Indeed, it is time to seriously consider how increasingly robust data and analytic capabilities and more efficient prospective research systems can be used to address the concerns raised in these articles, he said, adding that “as technological improvements and … connected networks of health systems make it feasible to conduct high-quality, low-cost RCTs [randomized, controlled trials] and to continuously monitor product performance, the impediments to progress are mostly those built into the culture of medicine and health care.”

Dr. Califf is with Duke Health and Duke University, Durham, N.C. He was the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Food and Drug Administration, from February 2016 to January 2017. He currently receives consulting payments from Merck and is employed as a scientific adviser by Verily Life Sciences (Alphabet).

The findings by Naci and colleagues and Zheng and colleagues raise concerns about whether the current regulatory system is too permissive in not requiring traditional randomized controlled trials for postmarketing evaluation of drugs that receive accelerated approval, and for high-risk medical device supplemental design modifications, Robert Califf, MD, wrote in an editorial.

However, randomization and blinding are not always feasible, and “despite the concerns raised by these two articles … it is important to remember that decisions about postmarket requirements and monitoring of these studies are overseen by full-time FDA employees with no financial conflicts,” he said, adding that “this underscores the importance of a talented workforce at the FDA with the variety of skills needed to assimilate information about manufacturing, quality systems, clinical outcomes, and the well-being and preferences of patients.”

A sweeping overhaul of the overall system is also needed, and is underway, he said, noting that substantial progress in balancing safety with access to effective therapies will come from systemic changes in the ecosystem rather than from imposing more severe demands on individual products (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:614-6).

Indeed, it is time to seriously consider how increasingly robust data and analytic capabilities and more efficient prospective research systems can be used to address the concerns raised in these articles, he said, adding that “as technological improvements and … connected networks of health systems make it feasible to conduct high-quality, low-cost RCTs [randomized, controlled trials] and to continuously monitor product performance, the impediments to progress are mostly those built into the culture of medicine and health care.”

Dr. Califf is with Duke Health and Duke University, Durham, N.C. He was the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Food and Drug Administration, from February 2016 to January 2017. He currently receives consulting payments from Merck and is employed as a scientific adviser by Verily Life Sciences (Alphabet).

The findings by Naci and colleagues and Zheng and colleagues raise concerns about whether the current regulatory system is too permissive in not requiring traditional randomized controlled trials for postmarketing evaluation of drugs that receive accelerated approval, and for high-risk medical device supplemental design modifications, Robert Califf, MD, wrote in an editorial.

However, randomization and blinding are not always feasible, and “despite the concerns raised by these two articles … it is important to remember that decisions about postmarket requirements and monitoring of these studies are overseen by full-time FDA employees with no financial conflicts,” he said, adding that “this underscores the importance of a talented workforce at the FDA with the variety of skills needed to assimilate information about manufacturing, quality systems, clinical outcomes, and the well-being and preferences of patients.”

A sweeping overhaul of the overall system is also needed, and is underway, he said, noting that substantial progress in balancing safety with access to effective therapies will come from systemic changes in the ecosystem rather than from imposing more severe demands on individual products (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:614-6).

Indeed, it is time to seriously consider how increasingly robust data and analytic capabilities and more efficient prospective research systems can be used to address the concerns raised in these articles, he said, adding that “as technological improvements and … connected networks of health systems make it feasible to conduct high-quality, low-cost RCTs [randomized, controlled trials] and to continuously monitor product performance, the impediments to progress are mostly those built into the culture of medicine and health care.”

Dr. Califf is with Duke Health and Duke University, Durham, N.C. He was the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, Food and Drug Administration, from February 2016 to January 2017. He currently receives consulting payments from Merck and is employed as a scientific adviser by Verily Life Sciences (Alphabet).

, two studies showed.

Between 2009 and 2013, the FDA granted accelerated approval for 22 drugs with 24 indications, which were supported by 30 preapproval studies with a median of 132 subjects. Only 12 of those studies (40%) were randomized, and only 6 (20%) were double blind. Eight (27%) included fewer than 100 subjects, and 20 (67%) included fewer than 200, reported Huseyin Naci, PhD, of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and his colleagues.

Further, at a minimum of 3 years after the approval, only half of the 38 confirmatory studies required by the FDA were completed, and, ultimately, only 25 of the 48 (66%) examined clinical efficacy, only 7 (18%) evaluated longer follow-up, and only 6 (16%) focused on safety, the investigators reported (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:626-36).

The proportion of studies that were randomized was slightly, but not significantly greater in the postapproval vs. preapproval period (56% vs. 40%), and only one was double blind. For 10 of 24 indications (42%), postapproval study requirements were completed and demonstrated efficacy based on surrogate measures, the investigators said.

Of the 14 remaining indications (58%) for which FDA study requirements had not yet been met, 2 (8%) had at least one confirmatory study that failed to demonstrate clinical benefit (without apparent action on the part of the FDA to rescind approval or impose additional requirements), 2 (8%) had a least one confirmatory study that was terminated, and 3 (13%) had at least one confirmatory study that was delayed by more than a year. The required studies for the remaining indications were progressing as planned, but for eight indications, clinical benefit had not yet been confirmed at 5 or more years after approval.

Similar concerns were seen in a review of clinical studies used to support high-risk medical device modification approvals. Such devices often undergo numerous modifications that receive FDA approval through one of six premarket approval (PMA) supplement pathways, and a total of 83 studies that supported 78 panel-track supplements (one of the 6 pathways and the only one that always required clinical data) approved between April 19, 2006, and Oct. 9, 2015, were identified. Nearly all (98%) of those 78 modifications were supported by just one study; only 45% of those studies were randomized clinical trials, and only 30% were blinded, reported Sarah Y. Zheng, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:619-25).

The median number of patients in the studies was 185, and the median follow-up was 180 days. Further, of 150 primary endpoints in the studies, 121 (81%) were surrogate endpoints, 57 (38%) were compared with controls, and 6 (11%) of those involved retrospective rather than active controls.

Age and sex were not reported for all enrolled patients in 40% and 30% of the studies, respectively, and in the case of one device modification study, 91% of enrolled patients were not included in the primary analysis.

“Given the extensive modification of many PMA supplement devices and the median preapproval follow-up of 6 months, obtaining additional data via [postapproval studies] is critical. However, the FDA required [postapproval studies] for the minority (37%) of the panel-track supplements,” the investigators noted, adding that only 13% of initiated postapproval studies were completed between 3 and 5 years after FDA approval, and that no warning letters, penalties, or fines were administered for noncompliance.

“These findings suggest that the quality of studies and data evaluated to support approval by the FDA of modifications of high-risk devices should be improved,” they concluded.

Dr. Zheng and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Naci reported having no conflicts of interest. One coauthor, Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, reported receiving unrelated grants from the FDA Office of Generic Drugs and Division of Health Communication.

, two studies showed.

Between 2009 and 2013, the FDA granted accelerated approval for 22 drugs with 24 indications, which were supported by 30 preapproval studies with a median of 132 subjects. Only 12 of those studies (40%) were randomized, and only 6 (20%) were double blind. Eight (27%) included fewer than 100 subjects, and 20 (67%) included fewer than 200, reported Huseyin Naci, PhD, of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and his colleagues.

Further, at a minimum of 3 years after the approval, only half of the 38 confirmatory studies required by the FDA were completed, and, ultimately, only 25 of the 48 (66%) examined clinical efficacy, only 7 (18%) evaluated longer follow-up, and only 6 (16%) focused on safety, the investigators reported (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:626-36).

The proportion of studies that were randomized was slightly, but not significantly greater in the postapproval vs. preapproval period (56% vs. 40%), and only one was double blind. For 10 of 24 indications (42%), postapproval study requirements were completed and demonstrated efficacy based on surrogate measures, the investigators said.

Of the 14 remaining indications (58%) for which FDA study requirements had not yet been met, 2 (8%) had at least one confirmatory study that failed to demonstrate clinical benefit (without apparent action on the part of the FDA to rescind approval or impose additional requirements), 2 (8%) had a least one confirmatory study that was terminated, and 3 (13%) had at least one confirmatory study that was delayed by more than a year. The required studies for the remaining indications were progressing as planned, but for eight indications, clinical benefit had not yet been confirmed at 5 or more years after approval.

Similar concerns were seen in a review of clinical studies used to support high-risk medical device modification approvals. Such devices often undergo numerous modifications that receive FDA approval through one of six premarket approval (PMA) supplement pathways, and a total of 83 studies that supported 78 panel-track supplements (one of the 6 pathways and the only one that always required clinical data) approved between April 19, 2006, and Oct. 9, 2015, were identified. Nearly all (98%) of those 78 modifications were supported by just one study; only 45% of those studies were randomized clinical trials, and only 30% were blinded, reported Sarah Y. Zheng, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues (JAMA. 2017 Aug 15;318[7]:619-25).

The median number of patients in the studies was 185, and the median follow-up was 180 days. Further, of 150 primary endpoints in the studies, 121 (81%) were surrogate endpoints, 57 (38%) were compared with controls, and 6 (11%) of those involved retrospective rather than active controls.

Age and sex were not reported for all enrolled patients in 40% and 30% of the studies, respectively, and in the case of one device modification study, 91% of enrolled patients were not included in the primary analysis.

“Given the extensive modification of many PMA supplement devices and the median preapproval follow-up of 6 months, obtaining additional data via [postapproval studies] is critical. However, the FDA required [postapproval studies] for the minority (37%) of the panel-track supplements,” the investigators noted, adding that only 13% of initiated postapproval studies were completed between 3 and 5 years after FDA approval, and that no warning letters, penalties, or fines were administered for noncompliance.

“These findings suggest that the quality of studies and data evaluated to support approval by the FDA of modifications of high-risk devices should be improved,” they concluded.

Dr. Zheng and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Naci reported having no conflicts of interest. One coauthor, Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, reported receiving unrelated grants from the FDA Office of Generic Drugs and Division of Health Communication.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For 8 of 24 drug indications, clinical benefit had not yet been confirmed at 5 or more years after approval, and only 13% of initiated postapproval studies were completed between 3 and 5 years after FDA device supplement approvals.

Data source: A review of FDA documents regarding 22 drugs with 24 indications, and a descriptive study of 83 clinical studies supporting 78 panel-track supplements.

Disclosures: Dr. Zheng and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Naci reported having no conflicts of interest. One coauthor, Aaron S. Kesselheim, MD, reported receiving unrelated grants from the FDA Office of Generic Drugs and Division of Health Communication.

Cannabidiol Changes Serum Levels of Antiepileptic Drugs

The pharmaceutical formulation of cannabidiol (CBD) is associated with significant changes in serum levels of clobazam, rufinamide, topiramate, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine, according to research published online ahead of print August 6 in Epilepsia. Furthermore, patients taking CBD and valproate may have abnormal liver function test results.

“A perception exists that since CBD is plant-based, it is natural and safe; and while this may be mostly true, our study shows that CBD, just like other antiepileptic drugs [AEDs], has interactions with other seizure drugs that patients and providers need to be aware of,” said Tyler Gaston, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Patients in a Compassionate-Use Study

Few data about CBD’s interactions with AEDs are available. To gain more information, Dr. Gaston and colleagues examined 42 children and 39 adults in the University of Alabama’s open-label compassionate-use study of CBD as an add-on therapy for treatment-resistant epilepsy. At baseline, the investigators obtained participants’ serum AED levels. Participants initiated treatment with 5 mg/kg/day of CBD along with their other AEDs. Every two weeks, participants underwent a physical examination and laboratory testing. The investigators obtained serum AED levels and increased the dose of CBD by 5 mg/kg/day to a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day. AED doses were adjusted if a clinical symptom or laboratory result was related to a potential interaction.

Dr. Gaston and colleagues used a mixed linear model to determine whether the plasma levels of each AED changed significantly with increasing CBD dose.

Many Serum Levels Remained in Therapeutic Range

The mean age of pediatric participants was 10, and 20 of the children were female. The mean age of adults was 29, and 20 of the adult participants were female. The mean number of concomitant AEDs at enrollment for all participants was three.

The investigators noted increases in serum levels of topiramate, rufinamide, and N-desmethylclobazam (ie, the active metabolite of clobazam) and a decrease in serum levels of clobazam with increasing CBD dose. They also observed increases in serum levels of zonisamide and eslicarbazepine with increasing CBD dose in adults. All mean level changes were within the accepted therapeutic range, except for those in clobazam and N-desmethylclobazam. Sedation was more frequent with higher N-desmethylclobazam levels in adults. Levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase were significantly higher in participants taking concomitant valproate.

One of the study’s limitations was that the sample sizes of patients taking each AED were small, which may have masked potential interactions with CBD, according to the researchers. In addition, the naturalistic study design resulted in significant noise in the data for which the researchers could not completely account in their analyses. Nevertheless, “this study emphasizes the importance of monitoring serum AED levels and liver function tests during treatment with CBD,” said Dr. Gaston.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gaston TE, Bebin EM, Cutter GR, et al. Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017 Aug 6 [Epub ahead of print].

The pharmaceutical formulation of cannabidiol (CBD) is associated with significant changes in serum levels of clobazam, rufinamide, topiramate, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine, according to research published online ahead of print August 6 in Epilepsia. Furthermore, patients taking CBD and valproate may have abnormal liver function test results.

“A perception exists that since CBD is plant-based, it is natural and safe; and while this may be mostly true, our study shows that CBD, just like other antiepileptic drugs [AEDs], has interactions with other seizure drugs that patients and providers need to be aware of,” said Tyler Gaston, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Patients in a Compassionate-Use Study

Few data about CBD’s interactions with AEDs are available. To gain more information, Dr. Gaston and colleagues examined 42 children and 39 adults in the University of Alabama’s open-label compassionate-use study of CBD as an add-on therapy for treatment-resistant epilepsy. At baseline, the investigators obtained participants’ serum AED levels. Participants initiated treatment with 5 mg/kg/day of CBD along with their other AEDs. Every two weeks, participants underwent a physical examination and laboratory testing. The investigators obtained serum AED levels and increased the dose of CBD by 5 mg/kg/day to a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day. AED doses were adjusted if a clinical symptom or laboratory result was related to a potential interaction.

Dr. Gaston and colleagues used a mixed linear model to determine whether the plasma levels of each AED changed significantly with increasing CBD dose.

Many Serum Levels Remained in Therapeutic Range

The mean age of pediatric participants was 10, and 20 of the children were female. The mean age of adults was 29, and 20 of the adult participants were female. The mean number of concomitant AEDs at enrollment for all participants was three.

The investigators noted increases in serum levels of topiramate, rufinamide, and N-desmethylclobazam (ie, the active metabolite of clobazam) and a decrease in serum levels of clobazam with increasing CBD dose. They also observed increases in serum levels of zonisamide and eslicarbazepine with increasing CBD dose in adults. All mean level changes were within the accepted therapeutic range, except for those in clobazam and N-desmethylclobazam. Sedation was more frequent with higher N-desmethylclobazam levels in adults. Levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase were significantly higher in participants taking concomitant valproate.

One of the study’s limitations was that the sample sizes of patients taking each AED were small, which may have masked potential interactions with CBD, according to the researchers. In addition, the naturalistic study design resulted in significant noise in the data for which the researchers could not completely account in their analyses. Nevertheless, “this study emphasizes the importance of monitoring serum AED levels and liver function tests during treatment with CBD,” said Dr. Gaston.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gaston TE, Bebin EM, Cutter GR, et al. Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017 Aug 6 [Epub ahead of print].

The pharmaceutical formulation of cannabidiol (CBD) is associated with significant changes in serum levels of clobazam, rufinamide, topiramate, zonisamide, and eslicarbazepine, according to research published online ahead of print August 6 in Epilepsia. Furthermore, patients taking CBD and valproate may have abnormal liver function test results.

“A perception exists that since CBD is plant-based, it is natural and safe; and while this may be mostly true, our study shows that CBD, just like other antiepileptic drugs [AEDs], has interactions with other seizure drugs that patients and providers need to be aware of,” said Tyler Gaston, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Patients in a Compassionate-Use Study

Few data about CBD’s interactions with AEDs are available. To gain more information, Dr. Gaston and colleagues examined 42 children and 39 adults in the University of Alabama’s open-label compassionate-use study of CBD as an add-on therapy for treatment-resistant epilepsy. At baseline, the investigators obtained participants’ serum AED levels. Participants initiated treatment with 5 mg/kg/day of CBD along with their other AEDs. Every two weeks, participants underwent a physical examination and laboratory testing. The investigators obtained serum AED levels and increased the dose of CBD by 5 mg/kg/day to a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day. AED doses were adjusted if a clinical symptom or laboratory result was related to a potential interaction.

Dr. Gaston and colleagues used a mixed linear model to determine whether the plasma levels of each AED changed significantly with increasing CBD dose.

Many Serum Levels Remained in Therapeutic Range

The mean age of pediatric participants was 10, and 20 of the children were female. The mean age of adults was 29, and 20 of the adult participants were female. The mean number of concomitant AEDs at enrollment for all participants was three.

The investigators noted increases in serum levels of topiramate, rufinamide, and N-desmethylclobazam (ie, the active metabolite of clobazam) and a decrease in serum levels of clobazam with increasing CBD dose. They also observed increases in serum levels of zonisamide and eslicarbazepine with increasing CBD dose in adults. All mean level changes were within the accepted therapeutic range, except for those in clobazam and N-desmethylclobazam. Sedation was more frequent with higher N-desmethylclobazam levels in adults. Levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase were significantly higher in participants taking concomitant valproate.

One of the study’s limitations was that the sample sizes of patients taking each AED were small, which may have masked potential interactions with CBD, according to the researchers. In addition, the naturalistic study design resulted in significant noise in the data for which the researchers could not completely account in their analyses. Nevertheless, “this study emphasizes the importance of monitoring serum AED levels and liver function tests during treatment with CBD,” said Dr. Gaston.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Gaston TE, Bebin EM, Cutter GR, et al. Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017 Aug 6 [Epub ahead of print].

Headache Trajectories Differ Five Years After TBI

BOSTON—Over five years after traumatic brain injury (TBI), a relatively large (24% to 30%) group of individuals experience chronic headache pain and a significant functional impact of headache, according to a pattern analysis of headache pain and impact following moderate to severe TBI. These results were presented at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. “Identification of members within these groups may be important to assist with an appropriate intensity of treatment to improve satisfaction with life and employment opportunity after TBI,” said Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. “The identification of trajectory membership may also be useful in evaluation of appropriate subjects for inclusion in studies of headache treatment after TBI.”

Headache is the most common symptom following TBI of any severity. Dr. Lucas and her research colleagues have previously reported high rates of headache in a prospective cohort of patients who experienced moderate to severe TBI. These patients have been followed for five years. New or worse headache occurred at a rate of 37% at three months, 33% at six months, 34% at 12 months, and 35% at 60 months post injury. The present study examined whether certain patterns or trajectories of headache occur over five years after TBI and whether demographic or injury characteristics are related to these trajectories. Trajectory type was also examined in relation to satisfaction with life and employment status five years after injury.

Data on 316 individuals were evaluated at five years. These patients were initially enrolled during inpatient rehabilitation after moderate to severe TBI. Enrollment was performed in person in the hospital. Structured telephone interviews were conducted at three, six, 12, and 60 months after TBI. At each time point, individuals who reported headache in the previous three months were asked to rate their headache pain on a 0 to 10 scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain) and to complete the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6). Discrete mixture modeling was used to estimate trajectory groups based on pain rating and on headache impact scores.

Four trajectories were found for headache pain over five years: minimal pain over time (25% of individuals), worsening pain over time (37%), improving pain over time (7%), and chronic pain over time (30%). A chronic pain trajectory was more common in females, those incurring TBI by violence, those who were unemployed prior to injury, those with a headache history prior to injury, and those with mental health problems. Those with a chronic pain trajectory had significantly lower satisfaction with life five years after injury, compared with other trajectory groups.

A chronic impact trajectory was more common in females and in those who incurred TBI by violence, had a prior history of headache, or were unemployed prior to injury. At five years post TBI, the chronic impact group was significantly more likely to be unemployed and less satisfied with life, compared with individuals in the minimal or worsening impact trajectory groups. Those employed prior to injury were more frequently in the worsening group for pain and impact, compared with those not employed prior to injury. No relationship was found for other demographic and injury data, including age, posttraumatic amnesia, or substance abuse prior to injury.

BOSTON—Over five years after traumatic brain injury (TBI), a relatively large (24% to 30%) group of individuals experience chronic headache pain and a significant functional impact of headache, according to a pattern analysis of headache pain and impact following moderate to severe TBI. These results were presented at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. “Identification of members within these groups may be important to assist with an appropriate intensity of treatment to improve satisfaction with life and employment opportunity after TBI,” said Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. “The identification of trajectory membership may also be useful in evaluation of appropriate subjects for inclusion in studies of headache treatment after TBI.”

Headache is the most common symptom following TBI of any severity. Dr. Lucas and her research colleagues have previously reported high rates of headache in a prospective cohort of patients who experienced moderate to severe TBI. These patients have been followed for five years. New or worse headache occurred at a rate of 37% at three months, 33% at six months, 34% at 12 months, and 35% at 60 months post injury. The present study examined whether certain patterns or trajectories of headache occur over five years after TBI and whether demographic or injury characteristics are related to these trajectories. Trajectory type was also examined in relation to satisfaction with life and employment status five years after injury.

Data on 316 individuals were evaluated at five years. These patients were initially enrolled during inpatient rehabilitation after moderate to severe TBI. Enrollment was performed in person in the hospital. Structured telephone interviews were conducted at three, six, 12, and 60 months after TBI. At each time point, individuals who reported headache in the previous three months were asked to rate their headache pain on a 0 to 10 scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain) and to complete the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6). Discrete mixture modeling was used to estimate trajectory groups based on pain rating and on headache impact scores.

Four trajectories were found for headache pain over five years: minimal pain over time (25% of individuals), worsening pain over time (37%), improving pain over time (7%), and chronic pain over time (30%). A chronic pain trajectory was more common in females, those incurring TBI by violence, those who were unemployed prior to injury, those with a headache history prior to injury, and those with mental health problems. Those with a chronic pain trajectory had significantly lower satisfaction with life five years after injury, compared with other trajectory groups.

A chronic impact trajectory was more common in females and in those who incurred TBI by violence, had a prior history of headache, or were unemployed prior to injury. At five years post TBI, the chronic impact group was significantly more likely to be unemployed and less satisfied with life, compared with individuals in the minimal or worsening impact trajectory groups. Those employed prior to injury were more frequently in the worsening group for pain and impact, compared with those not employed prior to injury. No relationship was found for other demographic and injury data, including age, posttraumatic amnesia, or substance abuse prior to injury.

BOSTON—Over five years after traumatic brain injury (TBI), a relatively large (24% to 30%) group of individuals experience chronic headache pain and a significant functional impact of headache, according to a pattern analysis of headache pain and impact following moderate to severe TBI. These results were presented at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. “Identification of members within these groups may be important to assist with an appropriate intensity of treatment to improve satisfaction with life and employment opportunity after TBI,” said Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD, Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. “The identification of trajectory membership may also be useful in evaluation of appropriate subjects for inclusion in studies of headache treatment after TBI.”

Headache is the most common symptom following TBI of any severity. Dr. Lucas and her research colleagues have previously reported high rates of headache in a prospective cohort of patients who experienced moderate to severe TBI. These patients have been followed for five years. New or worse headache occurred at a rate of 37% at three months, 33% at six months, 34% at 12 months, and 35% at 60 months post injury. The present study examined whether certain patterns or trajectories of headache occur over five years after TBI and whether demographic or injury characteristics are related to these trajectories. Trajectory type was also examined in relation to satisfaction with life and employment status five years after injury.

Data on 316 individuals were evaluated at five years. These patients were initially enrolled during inpatient rehabilitation after moderate to severe TBI. Enrollment was performed in person in the hospital. Structured telephone interviews were conducted at three, six, 12, and 60 months after TBI. At each time point, individuals who reported headache in the previous three months were asked to rate their headache pain on a 0 to 10 scale (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain) and to complete the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6). Discrete mixture modeling was used to estimate trajectory groups based on pain rating and on headache impact scores.

Four trajectories were found for headache pain over five years: minimal pain over time (25% of individuals), worsening pain over time (37%), improving pain over time (7%), and chronic pain over time (30%). A chronic pain trajectory was more common in females, those incurring TBI by violence, those who were unemployed prior to injury, those with a headache history prior to injury, and those with mental health problems. Those with a chronic pain trajectory had significantly lower satisfaction with life five years after injury, compared with other trajectory groups.

A chronic impact trajectory was more common in females and in those who incurred TBI by violence, had a prior history of headache, or were unemployed prior to injury. At five years post TBI, the chronic impact group was significantly more likely to be unemployed and less satisfied with life, compared with individuals in the minimal or worsening impact trajectory groups. Those employed prior to injury were more frequently in the worsening group for pain and impact, compared with those not employed prior to injury. No relationship was found for other demographic and injury data, including age, posttraumatic amnesia, or substance abuse prior to injury.

Model Predicts Outcomes After AED Withdrawal

An evidence-based model allows neurologists to predict individual patient outcomes following the withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), according to research published in the July issue of Epilepsia. The model indicates a patient’s risk of relapse and chance of long-term seizure freedom. The model therefore might help physicians and patients make individualized choices about treatment, said the authors.

Patients with epilepsy who have achieved seizure freedom may want to discontinue their AEDs to avoid their associated side effects. Discontinuation raises the risk of seizure recurrence, however. Previous prognostic meta-analyses have been unable to calculate individual outcome predictors’ effect sizes because of the heterogeneous methods and reporting in the literature.

Analyzing Individual Participant Data

To overcome this limitation, Herm J. Lamberink, MD, a doctoral student at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis using individual participant data from previous studies. They reviewed PubMed and Embase for articles that reported on patients with epilepsy who were seizure-free and had started withdrawal of AEDs. Eligible articles contained information regarding seizure recurrences during and after withdrawal. The investigators selected 25 candidate predictors based on a systematic review of the predictors of seizure recurrence after AED withdrawal.

Dr. Lamberink and colleagues identified 45 studies that included 7,082 patients in all. The meta-analysis included 10 studies with 1,769 patients. The populations included selected and nonselected children and adults. Median follow-up time was 5.3 years. In all, 812 patients (46%) had seizure relapse, which was a higher rate than the average reported in the literature. Approximately 9% of participants for whom data were available had seizures in their last year of follow-up, which suggests that they had not regained lasting seizure control.

Model Had Stable Performance

Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, age at onset of epilepsy, history of febrile seizures, number of seizures before remission, absence of a self-limiting epilepsy syndrome, developmental delay, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizure recurrence. Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, number of AEDs before withdrawal, female sex, family history of epilepsy, number of seizures before remission, focal seizures, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizures in the last year of follow-up.

The adjusted concordance statistics for the model were 0.65 for predicting seizure recurrence and 0.71 for predicting long-term seizure freedom. Internal–external cross validation indicated that the model had good and stable performance in all cohorts.

One limitation of the study is that the population included only participants who attempted to withdraw AEDs. In addition, too few cases of epileptic encephalopathy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy were included in the population to determine whether these disorders predict outcomes after AED withdrawal.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Lamberink HJ, Otte WM, Geerts AT, et al. Individualised prediction model of seizure recurrence and long-term outcomes after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in seizure-free patients: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):523-531.

An evidence-based model allows neurologists to predict individual patient outcomes following the withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), according to research published in the July issue of Epilepsia. The model indicates a patient’s risk of relapse and chance of long-term seizure freedom. The model therefore might help physicians and patients make individualized choices about treatment, said the authors.

Patients with epilepsy who have achieved seizure freedom may want to discontinue their AEDs to avoid their associated side effects. Discontinuation raises the risk of seizure recurrence, however. Previous prognostic meta-analyses have been unable to calculate individual outcome predictors’ effect sizes because of the heterogeneous methods and reporting in the literature.

Analyzing Individual Participant Data

To overcome this limitation, Herm J. Lamberink, MD, a doctoral student at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis using individual participant data from previous studies. They reviewed PubMed and Embase for articles that reported on patients with epilepsy who were seizure-free and had started withdrawal of AEDs. Eligible articles contained information regarding seizure recurrences during and after withdrawal. The investigators selected 25 candidate predictors based on a systematic review of the predictors of seizure recurrence after AED withdrawal.

Dr. Lamberink and colleagues identified 45 studies that included 7,082 patients in all. The meta-analysis included 10 studies with 1,769 patients. The populations included selected and nonselected children and adults. Median follow-up time was 5.3 years. In all, 812 patients (46%) had seizure relapse, which was a higher rate than the average reported in the literature. Approximately 9% of participants for whom data were available had seizures in their last year of follow-up, which suggests that they had not regained lasting seizure control.

Model Had Stable Performance

Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, age at onset of epilepsy, history of febrile seizures, number of seizures before remission, absence of a self-limiting epilepsy syndrome, developmental delay, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizure recurrence. Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, number of AEDs before withdrawal, female sex, family history of epilepsy, number of seizures before remission, focal seizures, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizures in the last year of follow-up.

The adjusted concordance statistics for the model were 0.65 for predicting seizure recurrence and 0.71 for predicting long-term seizure freedom. Internal–external cross validation indicated that the model had good and stable performance in all cohorts.

One limitation of the study is that the population included only participants who attempted to withdraw AEDs. In addition, too few cases of epileptic encephalopathy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy were included in the population to determine whether these disorders predict outcomes after AED withdrawal.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Lamberink HJ, Otte WM, Geerts AT, et al. Individualised prediction model of seizure recurrence and long-term outcomes after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in seizure-free patients: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):523-531.

An evidence-based model allows neurologists to predict individual patient outcomes following the withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), according to research published in the July issue of Epilepsia. The model indicates a patient’s risk of relapse and chance of long-term seizure freedom. The model therefore might help physicians and patients make individualized choices about treatment, said the authors.

Patients with epilepsy who have achieved seizure freedom may want to discontinue their AEDs to avoid their associated side effects. Discontinuation raises the risk of seizure recurrence, however. Previous prognostic meta-analyses have been unable to calculate individual outcome predictors’ effect sizes because of the heterogeneous methods and reporting in the literature.

Analyzing Individual Participant Data

To overcome this limitation, Herm J. Lamberink, MD, a doctoral student at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis using individual participant data from previous studies. They reviewed PubMed and Embase for articles that reported on patients with epilepsy who were seizure-free and had started withdrawal of AEDs. Eligible articles contained information regarding seizure recurrences during and after withdrawal. The investigators selected 25 candidate predictors based on a systematic review of the predictors of seizure recurrence after AED withdrawal.

Dr. Lamberink and colleagues identified 45 studies that included 7,082 patients in all. The meta-analysis included 10 studies with 1,769 patients. The populations included selected and nonselected children and adults. Median follow-up time was 5.3 years. In all, 812 patients (46%) had seizure relapse, which was a higher rate than the average reported in the literature. Approximately 9% of participants for whom data were available had seizures in their last year of follow-up, which suggests that they had not regained lasting seizure control.

Model Had Stable Performance

Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, age at onset of epilepsy, history of febrile seizures, number of seizures before remission, absence of a self-limiting epilepsy syndrome, developmental delay, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizure recurrence. Epilepsy duration before remission, seizure-free interval before AED withdrawal, number of AEDs before withdrawal, female sex, family history of epilepsy, number of seizures before remission, focal seizures, and epileptiform abnormality on EEG before withdrawal were independent predictors of seizures in the last year of follow-up.

The adjusted concordance statistics for the model were 0.65 for predicting seizure recurrence and 0.71 for predicting long-term seizure freedom. Internal–external cross validation indicated that the model had good and stable performance in all cohorts.

One limitation of the study is that the population included only participants who attempted to withdraw AEDs. In addition, too few cases of epileptic encephalopathy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy were included in the population to determine whether these disorders predict outcomes after AED withdrawal.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Lamberink HJ, Otte WM, Geerts AT, et al. Individualised prediction model of seizure recurrence and long-term outcomes after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in seizure-free patients: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(7):523-531.

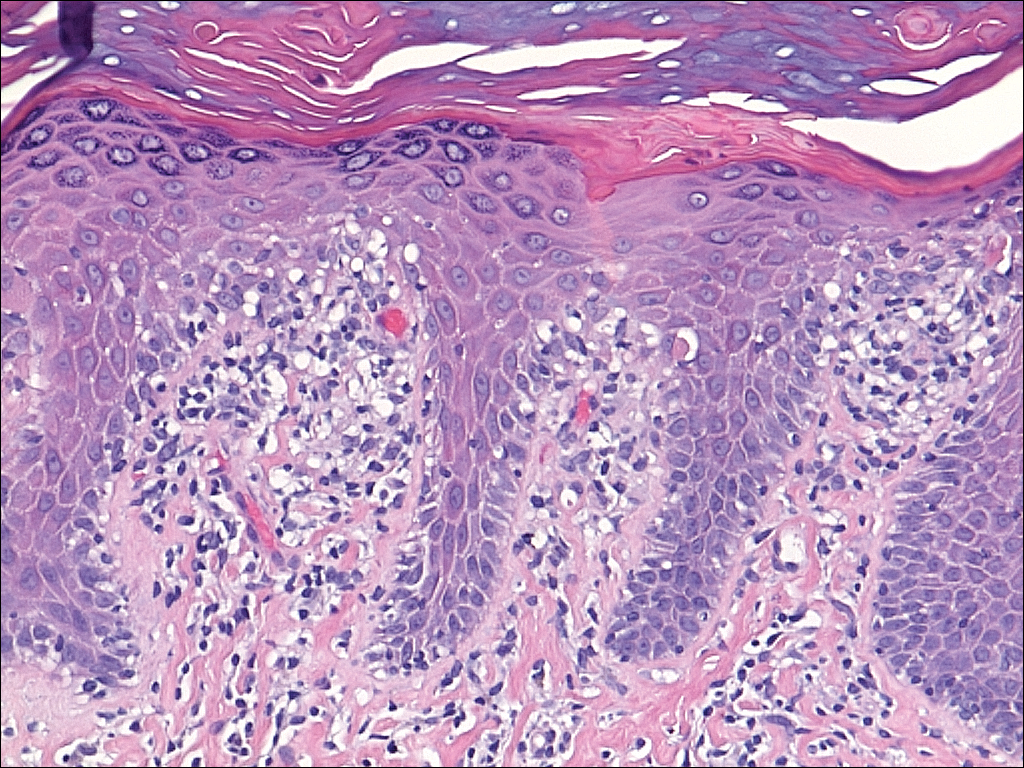

Sunny With a Chance of Skin Damage

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

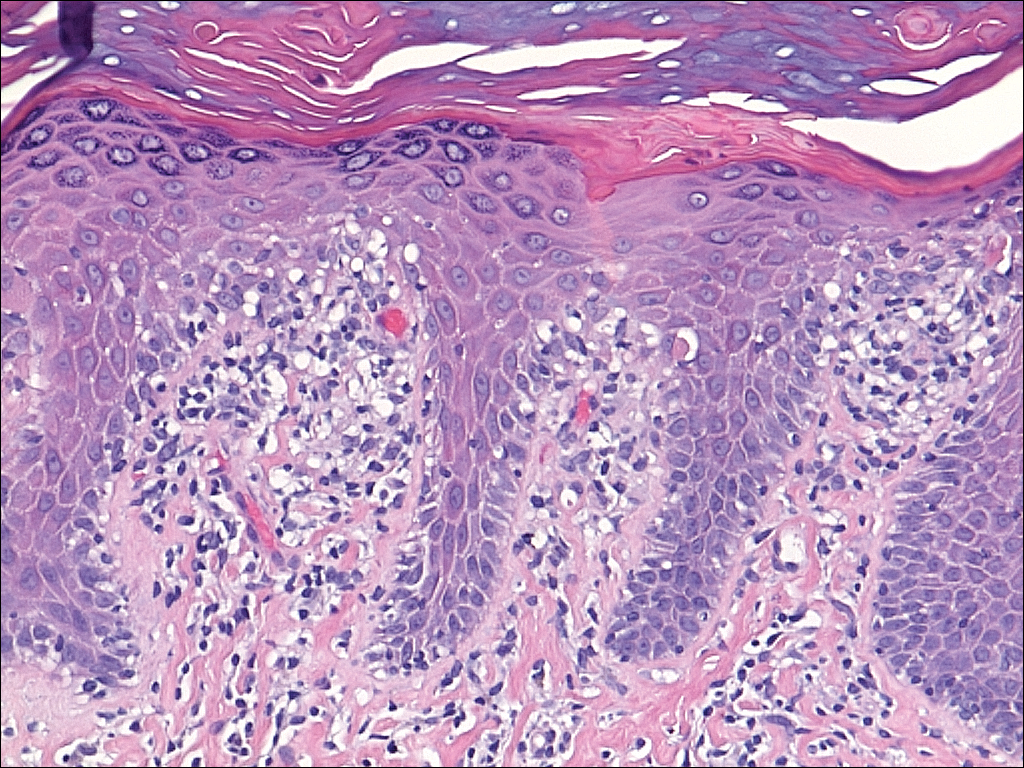

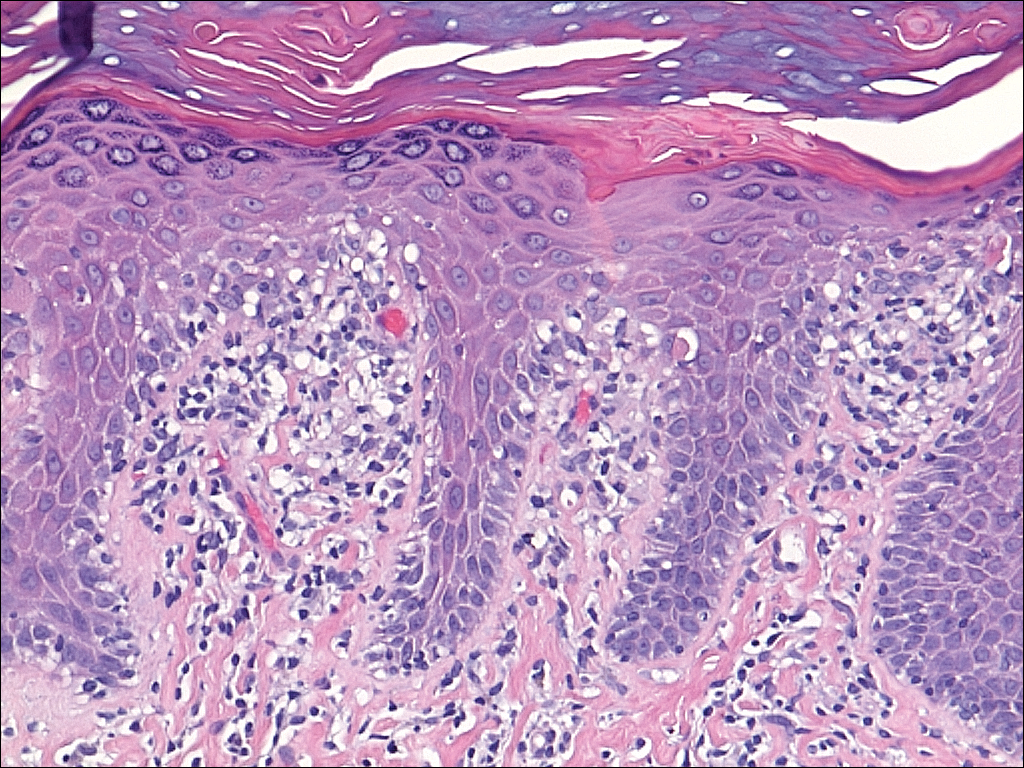

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

A 56-year-old woman has several lesions she is worried might be cancerous. Added to that, there have been changes to her facial skin over the past several years that are increasingly obvious to her friends and family and therefore concerning to the patient.

She has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, which were removed from her trunk in the distant past. She has lived in the southwestern United States all her life and has been smoking cigarettes since age 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s skin is quite fair, with abundant evidence of sun damage. She looks considerably older than her stated age.

Fortunately, no skin cancers are found on examination, but many closed and open comedones can be seen on both of her cheeks, stippled on rough, weathered skin. Solar elastosis manifests in this area as diffuse white thickening—what some might call “chicken skin.”

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is a fairly common result of chronic overexposure to UV sources; it is especially prevalent among men who smoke. For reasons not fully understood, the changes associated with FRS tend to be relegated to the bilateral malar cheeks, roughly even with the eyes. Apart from the patient being female, this case is quite typical.

Chronic overexposure to UV light is known to result in dermatologic changes such as solar elastosis and the aforementioned whitish plaques—which, on microscopic exam, are simply basophilic degeneration of the dermis. This degeneration can be seen all over the face, but it is particularly evident on the forehead and cheeks; the concentration of comedones on the cheeks is unique to FRS.

Treatment options include lasers and peels, which involve considerable expenditure of time and money. While the comedones can be extracted, they are likely to recur unless more invasive methods are used.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS) is seen primarily in men with chronic overexposure to sunlight—particularly those who smoke.

- FRS is characterized by localized collections of open and closed comedones superimposed on thickened, white “chicken skin” (solar elastosis).

- These changes typically occur on the bilateral cheeks of patients in the later decades of life, though they have been seen on patients in their 20s.

- Treatment is possible by means of laser resurfacing and/or chemical peels.

Lessons on using cannabinoids for pediatric epilepsy

DENVER – holds useful lessons for physicians in states where legal marijuana is a far more recent development, Amy R. Brooks-Kayal, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society.

Medical marijuana has been legal in Colorado for nearly 20 years. But the drug’s potential role in treating intractable pediatric epilepsy started getting a lot more attention in 2013 when a CNN report by Sanjay Gupta, MD, chronicled a child’s remarkable turnaround in response to medical marijuana. The story triggered a migration to the state by what has been termed “marijuana refugees”: desperate families with children who had the most severe, complex, treatment-refractory seizure disorders, said Dr. Brooks-Kayal, professor of pediatrics and neurology and chief of pediatric neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The situation, fortunately, has improved. There is now phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evidence of efficacy for an investigational proprietary cannabidiol oral solution known as Epidiolex for children and young adults with Dravet syndrome and drug-resistant seizures, as well as documentation of multiple adverse effects (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 25;376[21]:2011-20).

Dr. Brooks-Kayal, a past president of the American Epilepsy Society, said she believes this medication is potentially approvable by the Food and Drug Administration.

“In the world of new seizure medications, what is usually required by the FDA is a 50% reduction in seizures, which this agent gets close to reaching. But it does have a higher adverse event rate than many of our medications. However, this is a tough crowd. These are very, very difficult-to-treat children. So I think any addition to our armamentarium for these kids is going to be beneficial,” she said. “Unfortunately, though, it’s not going to be the panacea that I think some of our families are looking for.”

Based upon the Colorado experience, Dr. Brooks-Kayal offered the following suggestions for colleagues around the country as they begin fielding questions from families about medical marijuana for pediatric epilepsy:

- Provide families with the current data, discuss what’s known and still unknown, and encourage families to disclose the use of cannabinoids so the child can be monitored.

- Have the family keep a seizure diary. Get a baseline EEG and another at about 12 weeks. Do routine laboratory monitoring every 4 weeks, including liver function tests. “We think CBDs [cannabinoids] have the potential to worsen liver function,” she said.

- Stress the importance of leaving other seizure medications unchanged. “When this first started, the medical marijuana providers were recommending patients stop their other medications. The providers don’t do that anymore, fortunately,” Dr. Brooks-Kayal said. “Every week we were putting a child in a medically induced coma because they had status epilepticus, and it was the only way to stop their seizures. They started using marijuana products, they were sure it was going to be the cure, they stopped all their other medications, and they developed status epilepticus.”

- Establish policies with the hospital administration and pharmacy about how to handle marijuana products when a child is in the hospital. The Children’s Hospital Colorado pharmacy cannot store or dispense marijuana products because of federal regulations. And again, it’s unsafe to stop seizure medications abruptly, including marijuana products. Informed consent procedures need to be developed for when patients on cannabinoids are hospitalized.

- Encourage families to participate in one of the six Food and Drug Administration–approved double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of Epidiolex for Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, and infantile spasms sponsored by GW Pharmaceuticals.

Breaking down the evidence

Here’s what’s known and what is still unknown about the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids for the treatment of refractory pediatric epilepsy, according to Dr. Brooks-Kayal.

The knowns

Cannabinoids show activity against seizures in animal models. Moreover, initial clinical data suggest they may decrease seizures in some children with refractory epilepsy. This evidence includes a retrospective study from Children’s Hospital Colorado reliant upon parental reports of improvement (Epilepsy Behav. 2015 Apr;45:49-52), an Israeli retrospective study (Seizure. 2016 Feb;35:41-4), a positive open-label trial of an investigational oral oil-based solution of a pharmaceutical-grade cannabidiol known as Epidiolex (Lancet Neurol. 2016 Mar;15[3]:270-8), and evidence from a Food and Drug Administration–authorized phase 3, randomized clinical trial of Epidiolex (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 25;376[21]:2011-20).

The incidence of short-term adverse events associated with cannabinoids is substantial. The rate seems to be higher with Epidiolex than with many other medical marijuana products, although the potency is greater, too. These include somnolence, fatigue, and convulsions.

In addition, gastrointestinal side effects are common with Epidiolex. “Some are probably due to the oil base; some [are] probably due to the cannabidiol itself,” said Dr. Brooks-Kayal.

The unknowns

What types of seizures does it work for? This is under study in a series of FDA-authorized phase 3 randomized trials.

What is the placebo-subtracted response rate to cannabidiol? In the randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the median monthly frequency of seizures decreased from 12.4 to 5.9 with cannabidiol, compared with a reduction from 14.9 to 14.1 with placebo. This needs confirmation in additional trials.

What’s the optimal dose? The randomized trial tested just one dose – 20 mg/kg per day.

What are the drug interactions and their possible impact on cannabidiol efficacy? Outcomes appear to be better in patients on concomitant clobazam (Onfi), perhaps because of the significantly higher blood levels of clobazam’s major metabolite in children on cannabidiol.

Long-term effects

The jury is still out on the long-term adverse effects. “These medical marijuana products are being given by families to 2- and 3-month-olds. It will be years before we know about potential long-term cognitive and behavioral effects,” Dr. Brooks-Kayal said.

Dr. Brooks-Kayal reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

DENVER – holds useful lessons for physicians in states where legal marijuana is a far more recent development, Amy R. Brooks-Kayal, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society.

Medical marijuana has been legal in Colorado for nearly 20 years. But the drug’s potential role in treating intractable pediatric epilepsy started getting a lot more attention in 2013 when a CNN report by Sanjay Gupta, MD, chronicled a child’s remarkable turnaround in response to medical marijuana. The story triggered a migration to the state by what has been termed “marijuana refugees”: desperate families with children who had the most severe, complex, treatment-refractory seizure disorders, said Dr. Brooks-Kayal, professor of pediatrics and neurology and chief of pediatric neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The situation, fortunately, has improved. There is now phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evidence of efficacy for an investigational proprietary cannabidiol oral solution known as Epidiolex for children and young adults with Dravet syndrome and drug-resistant seizures, as well as documentation of multiple adverse effects (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 25;376[21]:2011-20).

Dr. Brooks-Kayal, a past president of the American Epilepsy Society, said she believes this medication is potentially approvable by the Food and Drug Administration.

“In the world of new seizure medications, what is usually required by the FDA is a 50% reduction in seizures, which this agent gets close to reaching. But it does have a higher adverse event rate than many of our medications. However, this is a tough crowd. These are very, very difficult-to-treat children. So I think any addition to our armamentarium for these kids is going to be beneficial,” she said. “Unfortunately, though, it’s not going to be the panacea that I think some of our families are looking for.”

Based upon the Colorado experience, Dr. Brooks-Kayal offered the following suggestions for colleagues around the country as they begin fielding questions from families about medical marijuana for pediatric epilepsy:

- Provide families with the current data, discuss what’s known and still unknown, and encourage families to disclose the use of cannabinoids so the child can be monitored.

- Have the family keep a seizure diary. Get a baseline EEG and another at about 12 weeks. Do routine laboratory monitoring every 4 weeks, including liver function tests. “We think CBDs [cannabinoids] have the potential to worsen liver function,” she said.