User login

Pregnancy not a barrier to providing cutaneous surgery

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

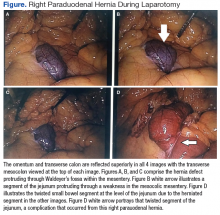

Right Paraduodenal Hernia

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

Paraduodenal hernia, also called mesocolic hernia, is a type of internal hernia that is thought to be caused by a congenital defect involving abnormal retroperitoneal fixation of the mesentery due to abnormal rotation of the midgut.1 Internal hernias account for only 1% of all hernias, and paraduodenal hernias make up 50% of those.2

Paraduodenal hernias can be classified as left or right with left being far more common than right, 75% and 25%, respectively.2 Due to the fixation abnormalities in the midgut, fossae are formed that help to classify left vs right paraduodenal hernias. Herniation through Landzert fossae results in a left paraduodenal hernia with the primary constituents of the hernia sac being the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.1 This result is due to an in utero defect of the small intestine herniated between the inferior mesenteric vein and posterior parietal attachments of the descending mesocolon to the retroperitoneal.3

In a right paraduodenal hernia, herniation occurs through Waldeyer fossae with the main contents of the hernia sac being the iliocolic, right colic, and middle colic vessels within the anterior wall and the superior mesenteric artery along the medial border of the hernia.1 Since there is a failure of rotation around the superior mesenteric artery, the majority of the small intestine remains to the right of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the small intestine being trapped between the posteriolateral peritoneum.3 Regardless of the type of paraduodenal hernia, patients usually will present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In these types of hernias, a computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast may suggest evidence of obstruction between the duodenum and jejunum, but this may be unclear. Although rare, clinical suspicion of paraduodenal hernia is necessary to prevent ensuing complications and mortality.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man presented to the emergency department with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, intermittent epigastric abdominal pain, and obstipation, which were suggestive of a small bowel obstruction. The patient reported similar intermittent episodes over the past 10 years that had resolved without surgery. The patient had no history of abdominal surgeries. A nasogastric tube was inserted and immediately drew out a significant amount of bilious contents. A CT scan indicated an obstruction at the proximal jejunum with suspicion of an internal hernia.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy soon after, which confirmed a right paraduodenal hernia (Figure). The surgery began laproscopically by retracting the omentum and transverse colon cranially to expose the ligament of Treitz. The hernia defect was identified on the mesentery where the proximal jejunum twisted on itself in a loop. The hernia was untwisted, and adhesions were removed. The posterior attachment of the hernia sac was freed with harmonic cautery and blunt dissection along with its attachment to the ligament of Treitz. In the process of freeing the herniation, a 1-cm enterotomy ensued, which did not contain succus or spillage of luminal contents at that time. Due to difficulties in visualizing the remainder of the small bowel, the procedure was converted to a laparotomy. This allowed complete freeing of the twisted loop of bowel.

Afterward, there was succus and bile draining from the enterotomy, so it was closed transversely in 2 layers, making sure there was a lumen between the layers. The first and second parts of the duodenum were examined followed by palpitation of the duodenal sweep. The remainder of the small bowel was visualized to the cecum, and the retroperitoneal space was dissected out of the hernia sac space. The abdomen was irrigated, and the omentum was draped back over the intestines. The fascia was closed followed by skin reapproximation with staples. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 6 with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Paraduodenal hernias are a type of internal hernia and a rare cause of intestinal obstruction accounting for about 0.5% of all hernias. Right paraduodenal hernias are far less common than left paraduodenal hernias and occur due to a defect in the jejunum mesentery called Waldeyer fossae.4 This is located at the third part of the duodenum and behind the superior mesenteric artery.4 Symptoms of paraduodenal hernias are nonspecific and may include nausea, vomiting, and intermittent cramping. Symptoms of obstruction can be intermittent due to the small bowel herniating through the fossae and then retracting.1 Computed tomography has good specificity and aides in the diagnosis of an internal hernia, but physicians must have a high index of suspicion as well.5

Definitive diagnosis and treatment of paraduodenal hernias involves laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy to visualize the internal hernia and its surrounding sac.4,5 All hernias should be repaired to prevent strangulation of the bowel, but internal hernias are even more important to fix because these hernias may not present until there is severe injury to the bowel.5 On identification of the paraduodenal hernia, it is important to release the bowel from the hernia sac, free up adhesions, and place small bowel segments back into the correct anatomical position.4,5

In the event of bowel injury, resection with reanastomosis is indicated. Careful dissection is important to prevent injury to the superior mesenteric artery, which supplies most of the small bowel and ascending colon.4,5 Injury to the superior mesenteric artery could lead to ischemia and gangrenous bowel.2 Immediate detection and early surgery intervention of these congenital hernias can prevent such complications.2 The literature includes reports of paraduodenal hernias with complications of gangrenous bowel that required small bowel resection.2 These complications further emphasize the need to proceed immediately with surgery if a paraduodenal hernia is suspected.

Conclusion

This rare cause of bowel obstruction was documented in order to emphasize the importance of having a high clinical suspicion for a paraduodenal hernia. This particular patient with no history of abdominal surgeries had previously dealt with bowel obstruction and would likely have this complication again without surgical intervention. Patients with paraduodenal hernias also are at risk for bowel ischemia, other high-risk complications, and even death.5 Although a CT scan provided information about an approximate location of the obstruction, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis. Going into the operation with paraduodenal hernia in the differential allowed the surgeon to be prepared for the appropriate anatomy involved with this procedure to minimize damage to important structures, such as the superior mesenteric artery and its branches.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

1. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

2. Fukada T, Mukai H, Shimamura F, Furukawa T, Miyazaki M. A causal relationship between right paraduodenal hernia and superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:159.

3. Skandalakis JE. Peritoneum, omenta, and internal hernias. In: Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, eds. Skandalakis Surgical Anatomy: The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. 1st ed. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publications; 2004:chap 10.

4. Papaziogas B, Souparis A, Makris J, Alexandrakis A, Papaziogas T. Surgical images: soft tissue. Right paraduodenal hernia. Can J Surg. 2004;47(3):195-196.

5. Manfredelli S, Andrea Z, Stefano P, et al. Rare small bowel obstruction: right paraduodenal hernia. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):412-415.

New telehealth legislation would provide for testing, expansion

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

A bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in late March 2017 would authorize the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test expanded telehealth services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Telehealth Innovation and Improvement Act (S.787), currently in the Senate Finance Committee, was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) and Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.). A similar bill they introduced in 2015 was never enacted.

However, there are physicians hoping to see this bill or others like it granted consideration. Currently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses only for certain telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved geographic areas, but the new bill would apply in suburban and urban areas as well, based on pilot testing of models and evaluating them for cost, quality, and effectiveness. Successful models would be covered by Medicare.

“Medicare has made some provisions for specific rural sites and niche areas, but writ large, there’s no prescribed way for people to just open a telemedicine shop and begin to bill,” said Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM, a member of the SHM Public Policy Committee.

With the exception of telestroke and critical care, “evidence is needed for the type of setting and type of clinical problems addressed by telemedicine. It’s not been tested enough,” added Dr. Flansbaum, who holds a dual appointment in hospital medicine and population health at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Penn. “How does it work for routine inpatient problems and how do hospitalists use it? We haven’t seen data there and that’s where a pilot comes in.”

Dr. Mac believes it inconsistent that, in many circumstances, physicians providing services via telemedicine technology are not reimbursed by Medicare and other payers.

“The expansion and ability to provide care in more unique ways – more specialties and in more environments – has expanded more quickly than the systems of reimbursement for professional fees have and it really is a bit of a hodgepodge now,” he said. “We certainly are pleased that this is getting attention and that we have leaders pushing for this in Congress. We don’t know for sure how the final legislation (on this bill) may look but hopefully there will be some form of this that will come to fruition.”

Whether telemedicine can reduce costs while improving outcomes, or improve outcomes without increasing costs, remains unsettled. A study published in Health Affairs in March 2017 indicates that while telehealth can improve access to care, it results in greater utilization, thereby increasing costs.1

The study relied on claims data for more than 300,000 patients in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System during 2011-2013. It looked at utilization of direct-to-consumer telehealth and spending for acute respiratory illness, one of the most common reasons patients seek telehealth services. While, per episode, telehealth visits cost 50% less than did an outpatient visit and less than 5% of an emergency department visit, annual spending per individual for acute respiratory illness went up $45 because, as the authors estimated, 88% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits represented new utilization.

Whether this would be the case for hospitalist patients remains to be tested.

“It gets back to whether or not you’re adding a necessary service or substituting a less expensive one for a more expensive one,” said Dr. Flansbaum. “Are physicians providing a needed service or adding unnecessary visits to the system?”

Jayne Lee, MD, has been a hospitalist with Eagle for nearly a decade. Before making the transition from an in-hospital physician to one treating patients from behind a robot – with assistance at the point of service from a nurse – she was working 10 shifts in a row at her home in the United States before traveling to her home in Paris. Dr. Mac offered her the opportunity to practice full time as a telehospitalist from overseas. Today, she is also the company’s chief medical officer and estimates she’s had more than 7,000 patient encounters using telemedicine technology.

Dr. Lee is licensed in multiple states – a barrier that plagues many would-be telehealth providers, but which Eagle has solved with its licensing and credentialing staff – and because she is often providing services at night to urban and rural areas, she sees a broad range of patients.

“We see things from coronary artery disease, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] exacerbations, and diabetes-related conditions to drug overdoses and alcohol abuse,” she said. “I enjoy seeing the variety of patients I encounter every night.”

Dr. Lee has to navigate each health system’s electronic medical records and triage systems but, she says, patient care has remained the same. And she’s providing services for hospitals that may not have another hospitalist to assign.

“Our practices keep growing, a sign that hospitals are needing our services now more than ever, given that there is a physician shortage and given the financial constraints we’re seeing in the healthcare system.” she said.

References

1. Ashwood JS, Mehrota A, Cowling D, et al. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Affairs. 2017; 36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130.

Some Transgender Women Are Reluctant to Combine Antiretroviral and Hormone Therapy

Transgender women are at high risk for HIV, but they are understandably concerned about taking both antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs and feminizing hormone therapy (HT). In a survey of 87 transgender women at a community-based AIDS service organization in Los Angeles, more than half of those living with HIV were worried about that, and many cited their concerns as a reason for not taking anti-HIV medications, HT, or both, say researchers from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Gilead Sciences.

Of the study participants, 69% were on some type of HT (including 25% who reported using HT without supervision from a qualified health professional). Transgender women living with HIV were more likely to use HT without supervision: 34% compared with 13% of those without HIV.

However, while 57% of the women living with HIV were concerned about drug interactions between ART and HT, only 49% of the participants had discussed the possibility with their health care team.

There is no scientific consensus on the safety and effectiveness of any combination of ART and HT in transgender women living with HIV, NIH says. Certain forms of ART and components of hormonal contraceptives interact, but because the drugs used in HT are at different dosages than in contraception, dose modifications or drug substitutions can reduce the risk of interactions.

The concerns also pose a problem for research, because transgender women may be reluctant to join clinical trials combining HT and ART. “Despite all indications that transgender women are a critical population in HIV care, very little is known about how to optimize coadministration of ART and hormonal therapies in this population,” said Jordan Lake, MD, study leader, who is continuing the research at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

“Making sure we are meeting the needs of transgender women living with HIV is key to addressing this pandemic,” said Judith Currier, MD, co-investigator and vice chair of the NIAID-supported AIDS Clinical Trials Network. “We need to provide an evidence-based response to these understandable concerns so that this key population and their sexual partners may reap the full benefits of effective HIV care.”

Source:

Drug interaction concerns may negatively affect HIV treatment adherence among transgender women. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/drug-interaction-concerns-may-negatively-affect-hiv-treatment-adherence-among-transgender-women. Published July 24, 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

Transgender women are at high risk for HIV, but they are understandably concerned about taking both antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs and feminizing hormone therapy (HT). In a survey of 87 transgender women at a community-based AIDS service organization in Los Angeles, more than half of those living with HIV were worried about that, and many cited their concerns as a reason for not taking anti-HIV medications, HT, or both, say researchers from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Gilead Sciences.

Of the study participants, 69% were on some type of HT (including 25% who reported using HT without supervision from a qualified health professional). Transgender women living with HIV were more likely to use HT without supervision: 34% compared with 13% of those without HIV.

However, while 57% of the women living with HIV were concerned about drug interactions between ART and HT, only 49% of the participants had discussed the possibility with their health care team.

There is no scientific consensus on the safety and effectiveness of any combination of ART and HT in transgender women living with HIV, NIH says. Certain forms of ART and components of hormonal contraceptives interact, but because the drugs used in HT are at different dosages than in contraception, dose modifications or drug substitutions can reduce the risk of interactions.

The concerns also pose a problem for research, because transgender women may be reluctant to join clinical trials combining HT and ART. “Despite all indications that transgender women are a critical population in HIV care, very little is known about how to optimize coadministration of ART and hormonal therapies in this population,” said Jordan Lake, MD, study leader, who is continuing the research at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

“Making sure we are meeting the needs of transgender women living with HIV is key to addressing this pandemic,” said Judith Currier, MD, co-investigator and vice chair of the NIAID-supported AIDS Clinical Trials Network. “We need to provide an evidence-based response to these understandable concerns so that this key population and their sexual partners may reap the full benefits of effective HIV care.”

Source:

Drug interaction concerns may negatively affect HIV treatment adherence among transgender women. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/drug-interaction-concerns-may-negatively-affect-hiv-treatment-adherence-among-transgender-women. Published July 24, 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

Transgender women are at high risk for HIV, but they are understandably concerned about taking both antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs and feminizing hormone therapy (HT). In a survey of 87 transgender women at a community-based AIDS service organization in Los Angeles, more than half of those living with HIV were worried about that, and many cited their concerns as a reason for not taking anti-HIV medications, HT, or both, say researchers from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Gilead Sciences.

Of the study participants, 69% were on some type of HT (including 25% who reported using HT without supervision from a qualified health professional). Transgender women living with HIV were more likely to use HT without supervision: 34% compared with 13% of those without HIV.

However, while 57% of the women living with HIV were concerned about drug interactions between ART and HT, only 49% of the participants had discussed the possibility with their health care team.

There is no scientific consensus on the safety and effectiveness of any combination of ART and HT in transgender women living with HIV, NIH says. Certain forms of ART and components of hormonal contraceptives interact, but because the drugs used in HT are at different dosages than in contraception, dose modifications or drug substitutions can reduce the risk of interactions.

The concerns also pose a problem for research, because transgender women may be reluctant to join clinical trials combining HT and ART. “Despite all indications that transgender women are a critical population in HIV care, very little is known about how to optimize coadministration of ART and hormonal therapies in this population,” said Jordan Lake, MD, study leader, who is continuing the research at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston.

“Making sure we are meeting the needs of transgender women living with HIV is key to addressing this pandemic,” said Judith Currier, MD, co-investigator and vice chair of the NIAID-supported AIDS Clinical Trials Network. “We need to provide an evidence-based response to these understandable concerns so that this key population and their sexual partners may reap the full benefits of effective HIV care.”

Source:

Drug interaction concerns may negatively affect HIV treatment adherence among transgender women. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/drug-interaction-concerns-may-negatively-affect-hiv-treatment-adherence-among-transgender-women. Published July 24, 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

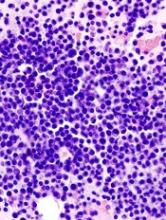

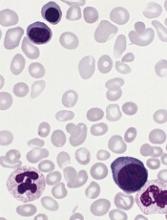

Tests can produce confusing results after HSCT in MM

Tests used to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma (MM) may often produce confusing results after patients have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), a new study suggests.

The tests—serum protein electrophoresis/serum immunofixation electrophoresis (SPEP/SIFE) and serum free light chain assay (SFLCA)—can sometimes produce an oligoclonal pattern that can be mistaken for an M spike and suggest disease recurrence.

The study showed that this confusing result was significantly more likely to occur after patients underwent HSCT than after they received chemotherapy.

Gurmukh Singh, MD, PhD, of Augusta University in Augusta, Georgia, reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Medicine Research.

For this study, Dr Singh looked at lab and clinical data on 251 MM patients treated from January 2010 to December 2016. One hundred and fifty-nine of those patients received autologous HSCTs.

Dr Singh compared results of SPEP/SIFE and/or SFLCA in patients who underwent HSCT and patients who did not. Each patient had at least 3 tests, and, for HSCT recipients, at least 2 of the tests occurred after transplant.

The incidence of oligoclonal patterns was significantly higher in HSCT recipients than in patients who had chemotherapy alone—57.9% and 8.8%, respectively (P=0.000003).

Only 5 of the 159 HSCT recipients had an oligoclonal pattern before treatment, but 92 of them had one afterward.

More than half of the oligoclonal patterns developed within the first year of HSCT. The earliest pattern was detected at 2 months—as soon as the first post-transplant tests were done—and a few occurred as late as 5 years later.

“We want to emphasize that oligoclonal bands should mostly be recognized as a response to treatment and not be mistaken as a recurrence of the original tumor,” Dr Singh said.

He explained that the key clarifier appears to be the location of the M spike when the diagnosis is made compared to the location of new spikes that may show up after HSCT.

“If the original peak was at location A, now the peak is location B, that allows us to determine that it is not the same abnormal, malignant antibody,” he said. “If it’s in a different location, it’s not the same protein. [T]his is just a normal response of recovery of the bone marrow that could be mistaken for recurrence of the disease.” ![]()

Tests used to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma (MM) may often produce confusing results after patients have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), a new study suggests.

The tests—serum protein electrophoresis/serum immunofixation electrophoresis (SPEP/SIFE) and serum free light chain assay (SFLCA)—can sometimes produce an oligoclonal pattern that can be mistaken for an M spike and suggest disease recurrence.

The study showed that this confusing result was significantly more likely to occur after patients underwent HSCT than after they received chemotherapy.

Gurmukh Singh, MD, PhD, of Augusta University in Augusta, Georgia, reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Medicine Research.

For this study, Dr Singh looked at lab and clinical data on 251 MM patients treated from January 2010 to December 2016. One hundred and fifty-nine of those patients received autologous HSCTs.

Dr Singh compared results of SPEP/SIFE and/or SFLCA in patients who underwent HSCT and patients who did not. Each patient had at least 3 tests, and, for HSCT recipients, at least 2 of the tests occurred after transplant.

The incidence of oligoclonal patterns was significantly higher in HSCT recipients than in patients who had chemotherapy alone—57.9% and 8.8%, respectively (P=0.000003).

Only 5 of the 159 HSCT recipients had an oligoclonal pattern before treatment, but 92 of them had one afterward.

More than half of the oligoclonal patterns developed within the first year of HSCT. The earliest pattern was detected at 2 months—as soon as the first post-transplant tests were done—and a few occurred as late as 5 years later.

“We want to emphasize that oligoclonal bands should mostly be recognized as a response to treatment and not be mistaken as a recurrence of the original tumor,” Dr Singh said.

He explained that the key clarifier appears to be the location of the M spike when the diagnosis is made compared to the location of new spikes that may show up after HSCT.

“If the original peak was at location A, now the peak is location B, that allows us to determine that it is not the same abnormal, malignant antibody,” he said. “If it’s in a different location, it’s not the same protein. [T]his is just a normal response of recovery of the bone marrow that could be mistaken for recurrence of the disease.” ![]()

Tests used to assess treatment response in multiple myeloma (MM) may often produce confusing results after patients have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), a new study suggests.

The tests—serum protein electrophoresis/serum immunofixation electrophoresis (SPEP/SIFE) and serum free light chain assay (SFLCA)—can sometimes produce an oligoclonal pattern that can be mistaken for an M spike and suggest disease recurrence.

The study showed that this confusing result was significantly more likely to occur after patients underwent HSCT than after they received chemotherapy.

Gurmukh Singh, MD, PhD, of Augusta University in Augusta, Georgia, reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Medicine Research.

For this study, Dr Singh looked at lab and clinical data on 251 MM patients treated from January 2010 to December 2016. One hundred and fifty-nine of those patients received autologous HSCTs.

Dr Singh compared results of SPEP/SIFE and/or SFLCA in patients who underwent HSCT and patients who did not. Each patient had at least 3 tests, and, for HSCT recipients, at least 2 of the tests occurred after transplant.

The incidence of oligoclonal patterns was significantly higher in HSCT recipients than in patients who had chemotherapy alone—57.9% and 8.8%, respectively (P=0.000003).

Only 5 of the 159 HSCT recipients had an oligoclonal pattern before treatment, but 92 of them had one afterward.

More than half of the oligoclonal patterns developed within the first year of HSCT. The earliest pattern was detected at 2 months—as soon as the first post-transplant tests were done—and a few occurred as late as 5 years later.

“We want to emphasize that oligoclonal bands should mostly be recognized as a response to treatment and not be mistaken as a recurrence of the original tumor,” Dr Singh said.

He explained that the key clarifier appears to be the location of the M spike when the diagnosis is made compared to the location of new spikes that may show up after HSCT.

“If the original peak was at location A, now the peak is location B, that allows us to determine that it is not the same abnormal, malignant antibody,” he said. “If it’s in a different location, it’s not the same protein. [T]his is just a normal response of recovery of the bone marrow that could be mistaken for recurrence of the disease.” ![]()

Insured cancer patients report ‘overwhelming’ financial distress

A study of 300 US cancer patients showed that paying for care can cause “overwhelming” financial distress, even when patients have health insurance.

Sixteen percent of the patients studied reported “high or overwhelming” financial distress, spending a median of 31% of their monthly household income on healthcare, not including insurance premiums.

They had a median monthly out-of-pocket cost of $728 (range, $6 to $47,250).

Fumiko Chino, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and her colleagues reported these findings in a letter to JAMA Oncology.

The researchers interviewed 300 insured cancer patients for this study. They had a median age of 59.6, and 68.3% were married.

Fifty-six percent of patients had private insurance, 35.7% had Medicare, and 7.3% had Medicaid.

Annual household incomes were as follows:

- 45.7%, $60,000 or greater

- 15.7%, $40,000 to $59,999

- 17.7%, $20,000 to 39,999

- 13.7%, lower than $20,000

- 7.3%, unknown.

The median monthly out-of-pocket cost for care was $592 (range, $3-$47,250), not including insurance premiums. The median relative cost of care was 11% of a patient’s monthly household income.

“Those who spend more than 10% of their income on healthcare costs are considered underinsured,” Dr Chino said. “Learning about the cost-sharing burden on some insured patients is important right now, given the uncertainty in health insurance.”

Most of the patients studied (83.7%, n=251) reported no, low, or average financial distress. Their median relative cost of care was 10% of their monthly household income, and their median monthly out-of-pocket cost was $565 (range, $3 to $26,756). Six percent of these patients had Medicaid, 39% had Medicare, and 53.8% had private insurance.

For the 16.3% of patients (n=49) who reported high or overwhelming financial distress, 67.3% had private insurance, 18.4% had Medicare, and 14.3% had Medicaid. As stated above, their median relative cost of care was 31% of their monthly household income, and their median monthly out-of-pocket cost was $728 (range, $6 to $47,250).

“This study adds to the growing evidence that we need to intervene,” said study author Yousuf Zafar, MD, of Duke Cancer Institute.

“We know there are a lot of barriers that prevent patients from talking about cost with their providers. We need to create tools for patients at risk of financial toxicity and connect them with resources in a timely fashion so they can afford their care.” ![]()

A study of 300 US cancer patients showed that paying for care can cause “overwhelming” financial distress, even when patients have health insurance.