User login

Parkinsonism and Vitamin C Deficiency

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

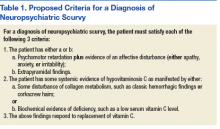

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

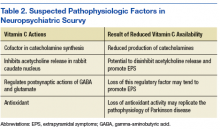

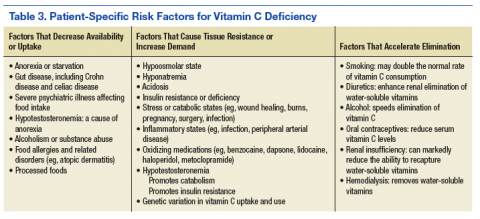

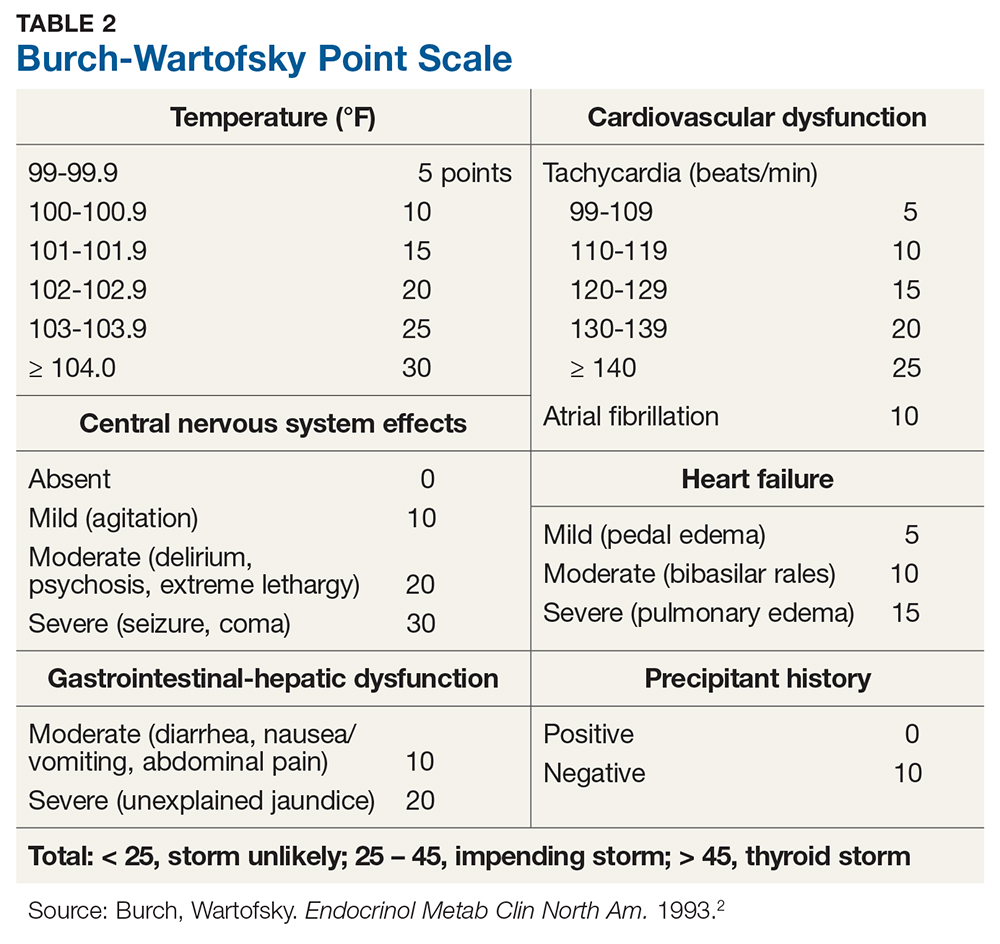

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency is known to affect brain function and is associated with parkinsonism.1 In 1752, James Lind, MD, described emotional and behavioral changes that herald the onset of scurvy and precede hemorrhagic findings.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) today refers to this stage as latent scurvy.3 The 2 case studies that follow present examples of patients with vitamin C deficiencies whose parkinsonism responded robustly to vitamin C replacement. These cases suggest that vitamin C deficiency may be a treatable cause of parkinsonism.

Case 1

Mr. A, a 60-year-old white male, was admitted to the Medicine Service for alcohol detoxification. The patient had a history of alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal seizures, tobacco dependence, and hyperlipidemia. He took no medications as an outpatient. On admission Mr. A’s body mass index (BMI) was 27.2. An initial examination revealed a marked resting tremor of the patient’s right hand with cogwheeling, which had not been present in examinations conducted in the previous 3 years. Mr. A had no prior history of a tremor. He had no cerebellar findings and no evidence of asterixis or of tremulousness associated with high-output cardiac states, such as de Musset sign.

Mr. A reported he had experienced the tremor for a month and that it had been worsening. He also was having difficulty using his dominant right hand, for routine daily activities. Mr. A was oriented, and his short-term memory was intact. He was ill-appearing, irritable with psychomotor slowing, and did not wish to rise from his bed. He had no gingival or periungual bleeding and did not bruise easily. He had no corkscrew hairs. The patient was started on no medications known to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

In the hospital, the tremor persisted unabated for 2 days. On the third day, Mr. A was started on 1,000 mg vitamin C IV twice daily. He received a total of 2,000 mg IV that day, but the IV fell out, and he refused its replacement. Several hours later, Mr. A stated that he felt much better, got out of bed, and asked to go outside to smoke. The author noted complete resolution of the right hand tremor and cogwheeling 20 hours after starting the vitamin C IV. Mr. A refused a repeat serum vitamin C assay.

Laboratory studies initially revealed that Mr. A had hyponatremia with a serum sodium of 121 mmol/L (normal range: 133 to 145 mmol/L) as well as hypokalemia with a serum potassium of 3.2 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L). He was hypoosmolar, with a serum osmolality of 276 mOsm/kg (normal range: 278 to 305 mOsm/kg). His vitamin C level was low at 0.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4 to 2.0 mg/dL). Mr. A also had a serum vitamin C level drawn 2 years prior that showed no symptoms of EPS, and at that time, the reading was 0.7 mg/dL. At admission to Medicine Services, Mr. A had a serum alcohol level of 211 mg/dL. Neuroimaging revealed diffuse cerebral and cerebellar volume loss.

Normal laboratory results included serum levels of vitamin B12, red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, free and total carnitine, alkaline phosphatase, manganese, and zinc. A urine drug screen was negative.

Case 2

Mr. B, a 69-year-old black male, was admitted to the hospital for depression complicated by alcohol dependence. He also had tobacco dependence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout. The patient’s BMI at admission was 16.1. Mr. B appeared ill, was worried about his health, and remained recumbent unless asked to move. He reported that his right hand had begun to shake at rest in the month prior to admission. The tremor made it difficult for him to drink. He pointed out stains on his hospital gurney from an attempt to drink orange juice prior to being assessed.

A physical examination revealed a distinct resting tremor with cogwheeling of the right hand; there was no other evidence of EPS, nor was there evidence of cognitive, cerebellar, or skin abnormalities, such as hemorrhages or corkscrew hairs. Asterixis was absent as was evidence of a high-output cardiac state that might produce a tremor, such as de Musset sign. A serum vitamin C level was obtained and returned at 0.0 mg/dL. A head computed tomography scan obtained the next day revealed mild cerebellar volume loss. A serum alkaline phosphatase level was elevated slightly at 136 U/L (normal range: 42 to 113 U/L). Normal serum values were returned for zinc, vitamins B12 and folate, rapid plasma reagin, sodium, and serum osmolality. A urine drug screen was negative, and serum alcohol level was < 5.0 mg/dL.

Mr. B took no medications expected to cause EPS. He received no micronutrient replacement until the day after admission when he began receiving oral vitamin C 1,000 mg twice a day. After receiving 3 doses, Mr. B’s resting tremor and cogwheeling completely resolved. He noticed he had stopped shaking and could now drink without spilling fluids. He also got out of bed and began interacting with others. Mr. B said he felt he was “doing well.” A repeat serum vitamin C level was 0.2 mg/dL on that day. The improvement was sustained over 3 days, and Mr. B was discharged to home.

Discussion

Both Mr. A and Mr. B presented with a typical picture of latent scurvy and the additional finding of parkinsonism. These cases are important for 2 reasons. First, the swift and full response of these patients’ parkinsonism to vitamin C replacement underscores the importance of considering a vitamin C deficiency when confronted with EPS. And second, both patients lacked signs of bleeding or of impaired collagen synthesis. This differs from the classic presentation of scurvy as a disorder primarily of collagen metabolism.4

Lind described the onset of scurvy as one in which striking emotional and behavior changes developed and later were followed by abnormal bleeding and even death.2 These early changes also were recognized by Shapter in 1847.5 Furthermore, the evidence that exists about the time-course of scurvy’s development suggests that neuropsychiatric findings precede the hemorrhagic.6 Indeed, classic skin findings, such as petechiae or corkscrew hairs, may develop years after the onset of neuropsychiatric changes.7,8

Despite WHO characterizing it as latent scurvy, the distinct syndromal presentation of hypovitaminosis C with parkinsonism along with the rapid response to vitamin C replacement argues for its recognition as a distinct clinical entity and not just a prelude to the hemorrhagic state. To assist in recognizing neuropsychiatric scurvy, the author suggests the operationalized approach described in Table 1.9

Pathophysiology

Vitamin C has an intimate role in the normal functioning of the basal ganglia. It is involved in the synthesis of catechecholamines, the regulation of the release and postsynaptic activities of various neurotransmitters, and managing the oxyradical toxicity of aerobic metabolism. Table 2 outlines some of the normal brain functions of vitamin C and the potential consequences of inadequate central vitamin C.9,10 Risk factors for vitamin C deficiency include those affecting the uptake, response to, and elimination of this vitamin (Table 3).11-14

The potential role of alcohol use by both patients also warrants mention. Current data suggest a nonlinear relationship between alcohol use and neurotoxicity. Epidemiologic data show that moderate alcohol consumption protects against the development of such neurodegenerative processes as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease.15,16 But the cases here reflect excessive use of alcohol. In this situation, a variety of progressive insults, such as those caused by oxyradical toxicity as well as malnutrition may foster the development of basal ganglia dysfunction.17

Measuring Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin C may be determined in several ways. The most frequently used laboratory measure of vitamin C status is the serum vitamin C level. This level is included in the WHO’s recommendations for diagnosis.3 However, this assay is limited because when facing total body depletion, the kidneys may restrict the elimination of vitamin C and tend to maintain serum vitamin C levels even as target tissue levels fall. An interesting example of this is the 0.2 mg/dL value that each patient registered. In Mr. A’s case, this reflected a systemic deficit of vitamin C, while in Mr. B’s case it correlated with the onset of effective repletion of body’s stores.

A fall in urinary output of vitamin C is another marker of hypovitaminosis C. When available, this laboratory test can be used with the serum level to assess total body stores of vitamin C. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets also store vitamin C. These target tissues tend to saturate when the oral intake ranges between 100 mg to 200 mg a day. This is the same point at which serum vitamin C levels peak and level off in normal, healthy adults.18,19 Once again, the limited availability of target-tissue assays puts these studies out of reach for most clinicians.

No evaluation is complete without some assurance of what the disease is not. Deficiencies of biotin, zinc, folate, and B12 all may affect the function of the basal ganglia.20 The biotin deficiencies literature is particularly robust. Biotin deficiencies affecting basal ganglia function are best known as inherited disorders of metabolism.21 Manganese intoxication also may present as a movement disorder.22

Treatment

Treatment of neuropsychiatric scurvy has relied on IV administration of vitamin C. Although the bioavailability of oral vitamin C among healthy adult volunteers is nearly complete up to about 200 mg a day, a patient with neuropsychiatric scurvy may need substantially more than that amount to accommodate total body deficiencies and increased demands.23 The IV route allows serum vitamin C levels up to 100 times higher than by the oral route.24 Mr. B is, in fact, the first person reported in the literature with neuropsychiatric scurvy to respond to oral vitamin C replacement alone. Once repletion of vitamin C is complete, it is useful to consider a maintenance replacement dose based on a patient’s risk factors and needs.

A healthy adult should ingest about 120 mg of vitamin C daily. Smokers and pregnant women may require more, but this recommendation was intended to address their needs as well.25 Many commercial multivitamins use the old recommended daily allowance of 60 mg, so it may be safest to recommend specifically a vitamin C tablet with at least 120 mg when ordering vitamin C replacement.

Tight control of the serum vitamin C concentration means that little additional vitamin C will be taken up by the gut beyond 200 mg orally a day, which helps minimize any concerns about long-term toxicity. It takes several weeks to deplete vitamin C from the human body when vitamin C is removed from the diet, so a patient with a previously treated deficiency of vitamin C should wait a month before a repeat serum vitamin C level measurement.

The half life of vitamin C is normally ≤ 2 hours. When renal function is intact, vitamin C in excess of immediate need is lost through renal filtration. Toxicity is rare under these conditions.26 When vitamin C toxicity has been reported, it has occurred in the setting of prolonged supplementation, usually when a patient already experienced a renal injury. The main toxicities attributed to vitamin C are oxalate crystal formation with subsequent renal injury and exacerbation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD).24

Oxalate formation due to vitamin C replacement is uncommon, but patients with preexisting calcium oxalate stones may be at risk for further stone formation when they receive additional vitamin C.27 This is most likely to occur when treatment with parenteral vitamin C is prolonged, which is not typical for patients with neuropsychiatric scurvy who tend to respond rapidly to vitamin C replenishment. Reports of acute hemolytic episodes among patient with G6PD deficiency receiving vitamin C exist, although these cases are rare.28 Furthermore, some authors advocate for the use of ascorbic acid to treat methemoglobinemia associated with G6PD deficiency, when methylene blue is not available.29 It may be reasonable to begin treatment with oral vitamin C for patients with NPS and G6PD deficiency. This is equivalent to a low-dose form of vitamin C replacement and may help avoid the theoretically pro-oxidant effects of larger, IV doses of vitamin C.30

Conclusion

The recent discovery of movement disorders in scurvy has enlarged the picture of vitamin C deficiency. The cases here demonstrate how hypovitaminosis C with central nervous system manifestations may be identified and treated. This relationship fits well within the established basic science and clinical framework for scurvy, and the clinical implications for scurvy remain in many ways unchanged. First, malnutrition must be considered even when a patient’s habitus suggests he is well fed. Also, it is more likely to see scurvy without all of the classic findings than an end-stage case of the disease.31 In the right clinical setting, it is reasonable to think of a vitamin C deficiency before the patient develops bleeding gums and corkscrew hairs. And as is typical of vitamin deficiencies, the treatment of a vitamin C deficiency usually results in swift improvement. Finally, for those who treat movement disorders or who prescribe agents such as antipsychotics that may cause movement disorders, it is important to recognize vitamin C deficiency as another potential explanation for EPS.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

1. Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K, et al. Lymphocyte vitamin C levels as potential biomarker for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):406-408.

2. Lind J. The diagnostics, or symptoms. A Treatise on the Scurvy, in Three Parts. 3rd ed. London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls, T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co., G. Pearch, and Woodfall; 1772:98-129.

3. World Health Organization. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NHD_99.11.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 6, 2017.

4. Sasseville D. Scurvy: curse and cure in New France. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):431.

5. Shapter T. On the recent occurrence of scurvy in Exeter and the neighbourhood. Prov Med Surg J. 1847;11(11):281-285.

6. Kinsman RA, Hood J. Some behavioral effects of ascorbic acid deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(4):455-464.

7. DeSantis J. Scurvy and psychiatric symptoms. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1993;29(1):18-22.

8. Walter JF. Scurvy resulting from a self-imposed diet. West J Med. 1979;130(2):177-179.

9. Brown TM. Neuropsychiatric scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):12-20.

10. Feuerstein TJ, Weinheimer G, Lang G, Ginap T, Rossner R. Inhibition by ascorbic acid of NMDA-evoked acetylcholine release in rabbit caudate nucleus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348(5):549-551.

11. Kim J, Kwon J, Noh G, Lee SS. The effects of elimination diet on nutritional status in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7(6):488-494.

12. Langlois M, Duprez D, Delanghe J, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863-1868.

13. Nappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An atypical case of methemoglobinemia due to self-administered benzocaine. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:670979.

14. Wright AD, Stevens E, Ali M, Carroll DW, Brown TM. The neuropsychiatry of scurvy. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):179-185.

15. Bate C, Williams A. Ethanol protects cultured neurons against amyloid-β and α-synuclein-induced synapse damage. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(8):1406-1412.

16. Vasanthi HR, Parameswari RP, DeLeiris J, Das DK. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1505-1512.

17. Vaglini F, Viaggi C, Piro V, et al. Acetaldehyde and parkinsonism: role of CYP450 2E1. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:71.

18. Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9842-9846.

19. Levine M, Padayatty SJ, Espey MG. Vitamin C: a concentration-function approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):78-88.

20. Quiroga MJ, Carroll DW, Brown TM. Ascorbate- and zinc-responsive parkinsonism. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(11):1515-1520.

21. Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology. 2013;80(3):261-267.

22. Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT. Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:277-312.

23. Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3704-3709.

24. Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, Jameson MB, Findlay MP. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):22-37.

25. Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1086-1107.

26. Nielsen TK, Højgaard M, Andersen JT, Poulsen HE, Lykkesfeldt J, Mikines KJ. Elimination of ascorbic acid after high-dose infusion in prostate cancer patients: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):343-348.

27. Baxmann AC, De O G Mendonça C, Heilberg IP. Effect of vitamin C supplements on urinary oxalate and pH in calcium stone-forming patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1066-1071.

28. Huang YC, Chang TK, Fu YC, Jan SL. C for colored urine: acute hemolysis induced by high-dose ascorbic acid. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):984.

29. Rino PB, Scolnik D, Fustiñana A, Mitelpunkt A, Glatstein M. Ascorbic acid for the treatment of methemoglobinemia: the experience of a large tertiary care pediatric hospital. Am J Ther. 2014;21(4):240-243.

30. Du J, Cullen JJ, Buettner GR. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826(2):443-457.

31. Fouron JC, Chicoine L. Le scorbut: aspects particuliers de l’association rachitisme-scorbut. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;86(26):1191-1196.

Testing the Limits of Dual Antiplatelet Treatment for PCI Patients

What’s the right duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for patients who have had drug-eluting stents implanted? According to researchers from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, Korea, long-term clinical outcomes are similar whether patients receive therapy for less than or longer than 12 months.

The researchers conducted a retrospective study of 512 patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) and were event free at 12 months. They separated the patients into 2 groups: 199 received aspirin and clopidogrel for ≤ 12 months, and 313 for > 12 months. The primary outcome was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event (MACCE) during follow-up. Median follow-up was 64 months.

Related: Statins for the Physically Fit: Do They Help or Hurt?

No significant differences were seen between the groups in the incidence of MACCE: 21.6% of the patients in the ≤ 12-month group and 17.6% of the patients in the > 12-month group developed MACCE. After propensity matching, moderate or severe bleeding rates were also similar (1.6% in the shorter duration group and 2.2% in the longer duration group).

The researchers note that previously published data showed that longer duration DAPT was not associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with CTO, although other subsets of complex PCI, such as longer stent length, bifurcation stenting, or multiple stents showed better clinical outcomes. To the best of their knowledge, the researchers add, theirs is the first study to directly compare DAPT durations in patients with CTO-PCI.

Related: A Heart Failure Management Program Using Shared Medical Appointments

Source:

Lee SH, Yang JH, Choi SH, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176737.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176737.

What’s the right duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for patients who have had drug-eluting stents implanted? According to researchers from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, Korea, long-term clinical outcomes are similar whether patients receive therapy for less than or longer than 12 months.

The researchers conducted a retrospective study of 512 patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) and were event free at 12 months. They separated the patients into 2 groups: 199 received aspirin and clopidogrel for ≤ 12 months, and 313 for > 12 months. The primary outcome was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event (MACCE) during follow-up. Median follow-up was 64 months.

Related: Statins for the Physically Fit: Do They Help or Hurt?

No significant differences were seen between the groups in the incidence of MACCE: 21.6% of the patients in the ≤ 12-month group and 17.6% of the patients in the > 12-month group developed MACCE. After propensity matching, moderate or severe bleeding rates were also similar (1.6% in the shorter duration group and 2.2% in the longer duration group).

The researchers note that previously published data showed that longer duration DAPT was not associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with CTO, although other subsets of complex PCI, such as longer stent length, bifurcation stenting, or multiple stents showed better clinical outcomes. To the best of their knowledge, the researchers add, theirs is the first study to directly compare DAPT durations in patients with CTO-PCI.

Related: A Heart Failure Management Program Using Shared Medical Appointments

Source:

Lee SH, Yang JH, Choi SH, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176737.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176737.

What’s the right duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for patients who have had drug-eluting stents implanted? According to researchers from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, Korea, long-term clinical outcomes are similar whether patients receive therapy for less than or longer than 12 months.

The researchers conducted a retrospective study of 512 patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) and were event free at 12 months. They separated the patients into 2 groups: 199 received aspirin and clopidogrel for ≤ 12 months, and 313 for > 12 months. The primary outcome was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event (MACCE) during follow-up. Median follow-up was 64 months.

Related: Statins for the Physically Fit: Do They Help or Hurt?

No significant differences were seen between the groups in the incidence of MACCE: 21.6% of the patients in the ≤ 12-month group and 17.6% of the patients in the > 12-month group developed MACCE. After propensity matching, moderate or severe bleeding rates were also similar (1.6% in the shorter duration group and 2.2% in the longer duration group).

The researchers note that previously published data showed that longer duration DAPT was not associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with CTO, although other subsets of complex PCI, such as longer stent length, bifurcation stenting, or multiple stents showed better clinical outcomes. To the best of their knowledge, the researchers add, theirs is the first study to directly compare DAPT durations in patients with CTO-PCI.

Related: A Heart Failure Management Program Using Shared Medical Appointments

Source:

Lee SH, Yang JH, Choi SH, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176737.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176737.

Sleep Apnea on the Rise Among Veterans

Male veterans who reported mild-to-moderate psychological distress in the previous year had 61% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea, according to a California State University study. Those with serious psychological distress had 138% higher odds. The average prevalence of sleep apnea was 5.9%, but the proportions rose from 3.7% in 2005 to 8.1% in 2014.

The researchers analyzed data from the 2005-2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. They cite other research that found the age-adjusted prevalence of sleep apnea among U.S. veterans increased almost 6-fold from 2000 to 2010. They also point to an evaluation of veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn that found that 69.2% of 159 veterans screened were at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

An even stronger risk factor was asthma. Veterans with a past-year diagnosis of asthma had 256% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea than among those without asthma. The researchers note that men and women may be asymptomatic when they are recruited but develop asthma due to environmental factors during deployment. The researchers urge more and better screening regardless of whether the service member had asthma symptoms during recruitment.

Their study is unique, the researchers say, in that it demonstrates a putative relationship between sleep apnea and mental illness. They suggest multidisciplinary interventions, including peer-support strategies to improve veterans’ mental health and community-based resources to help improve access to health care. Above all, the researchers urge more rigorous screening of sleep apnea and better sleep apnea treatment for veterans.

Male veterans who reported mild-to-moderate psychological distress in the previous year had 61% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea, according to a California State University study. Those with serious psychological distress had 138% higher odds. The average prevalence of sleep apnea was 5.9%, but the proportions rose from 3.7% in 2005 to 8.1% in 2014.

The researchers analyzed data from the 2005-2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. They cite other research that found the age-adjusted prevalence of sleep apnea among U.S. veterans increased almost 6-fold from 2000 to 2010. They also point to an evaluation of veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn that found that 69.2% of 159 veterans screened were at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

An even stronger risk factor was asthma. Veterans with a past-year diagnosis of asthma had 256% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea than among those without asthma. The researchers note that men and women may be asymptomatic when they are recruited but develop asthma due to environmental factors during deployment. The researchers urge more and better screening regardless of whether the service member had asthma symptoms during recruitment.

Their study is unique, the researchers say, in that it demonstrates a putative relationship between sleep apnea and mental illness. They suggest multidisciplinary interventions, including peer-support strategies to improve veterans’ mental health and community-based resources to help improve access to health care. Above all, the researchers urge more rigorous screening of sleep apnea and better sleep apnea treatment for veterans.

Male veterans who reported mild-to-moderate psychological distress in the previous year had 61% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea, according to a California State University study. Those with serious psychological distress had 138% higher odds. The average prevalence of sleep apnea was 5.9%, but the proportions rose from 3.7% in 2005 to 8.1% in 2014.

The researchers analyzed data from the 2005-2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. They cite other research that found the age-adjusted prevalence of sleep apnea among U.S. veterans increased almost 6-fold from 2000 to 2010. They also point to an evaluation of veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn that found that 69.2% of 159 veterans screened were at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

An even stronger risk factor was asthma. Veterans with a past-year diagnosis of asthma had 256% higher odds of experiencing sleep apnea than among those without asthma. The researchers note that men and women may be asymptomatic when they are recruited but develop asthma due to environmental factors during deployment. The researchers urge more and better screening regardless of whether the service member had asthma symptoms during recruitment.

Their study is unique, the researchers say, in that it demonstrates a putative relationship between sleep apnea and mental illness. They suggest multidisciplinary interventions, including peer-support strategies to improve veterans’ mental health and community-based resources to help improve access to health care. Above all, the researchers urge more rigorous screening of sleep apnea and better sleep apnea treatment for veterans.

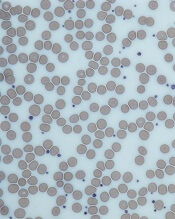

Glucose metabolism deemed key to platelet survival

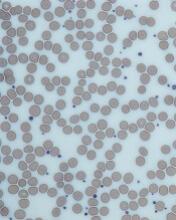

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

Team characterizes RIMs in childhood cancer survivors

Neuroscientists say they have uncovered genetic differences between radiation-induced meningiomas (RIMs) and sporadic meningiomas (SMs).

Their work suggests RIMs have a different “mutational landscape” from SMs, a finding that may have “significant therapeutic implications” for childhood cancer survivors who undergo cranial radiation.

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

“Radiation-induced meningiomas appear the same [as SMs] on MRI and pathology, feel the same during surgery, and look the same under the operating microscope,” Dr Zadeh said.

“What’s different is they are more aggressive, tend to recur in multiples, and invade the brain, causing significant morbidity and limitations (or impairments) for individuals who survive following childhood radiation. By understanding the biology, the goal is to identify a therapeutic strategy that could be implemented early on after childhood radiation to prevent the formation of these tumors in the first place.”

To better understand the biology, Dr Zadeh and her colleagues analyzed 31 RIMs. This included 18 tumors from 16 patients with childhood cancers, 9 with leukemia.

The researchers found NF2 gene rearrangements in 12 of the RIMs and noted that such rearrangements have not been observed in SMs.

On the other hand, recurrent mutations characteristic of SMs—AKT1, KLF4, TRAF7, and SMO—were not found in the RIMs.

The researchers also noted that, overall, chromosomal aberrations in RIMs were more complex than those observed in SMs. And combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 22q was common in RIMs (16/18).

“Our research identified a specific rearrangement involving the NF2 gene that causes radiation-induced meningiomas,” said Kenneth Aldape, MD, of University Health Network in Toronto.

“But there are likely other genetic rearrangements that are occurring as a result of that radiation-induced DNA damage. So one of the next steps is to identify what the radiation is doing to the DNA of the meninges.”

“In addition, identifying the subset of childhood cancer patients who are at highest risk to develop meningioma is critical so that they could be followed closely for early detection and management.” ![]()

Neuroscientists say they have uncovered genetic differences between radiation-induced meningiomas (RIMs) and sporadic meningiomas (SMs).

Their work suggests RIMs have a different “mutational landscape” from SMs, a finding that may have “significant therapeutic implications” for childhood cancer survivors who undergo cranial radiation.

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

“Radiation-induced meningiomas appear the same [as SMs] on MRI and pathology, feel the same during surgery, and look the same under the operating microscope,” Dr Zadeh said.

“What’s different is they are more aggressive, tend to recur in multiples, and invade the brain, causing significant morbidity and limitations (or impairments) for individuals who survive following childhood radiation. By understanding the biology, the goal is to identify a therapeutic strategy that could be implemented early on after childhood radiation to prevent the formation of these tumors in the first place.”

To better understand the biology, Dr Zadeh and her colleagues analyzed 31 RIMs. This included 18 tumors from 16 patients with childhood cancers, 9 with leukemia.

The researchers found NF2 gene rearrangements in 12 of the RIMs and noted that such rearrangements have not been observed in SMs.

On the other hand, recurrent mutations characteristic of SMs—AKT1, KLF4, TRAF7, and SMO—were not found in the RIMs.

The researchers also noted that, overall, chromosomal aberrations in RIMs were more complex than those observed in SMs. And combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 22q was common in RIMs (16/18).

“Our research identified a specific rearrangement involving the NF2 gene that causes radiation-induced meningiomas,” said Kenneth Aldape, MD, of University Health Network in Toronto.