User login

Rowell Syndrome: Targeting a True Definition

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

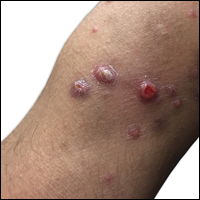

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

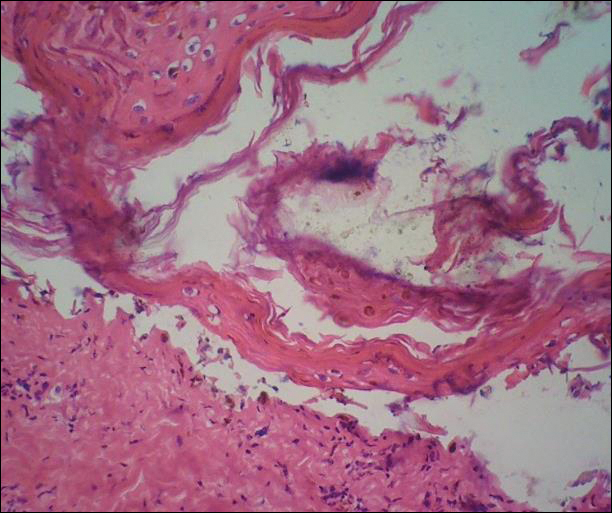

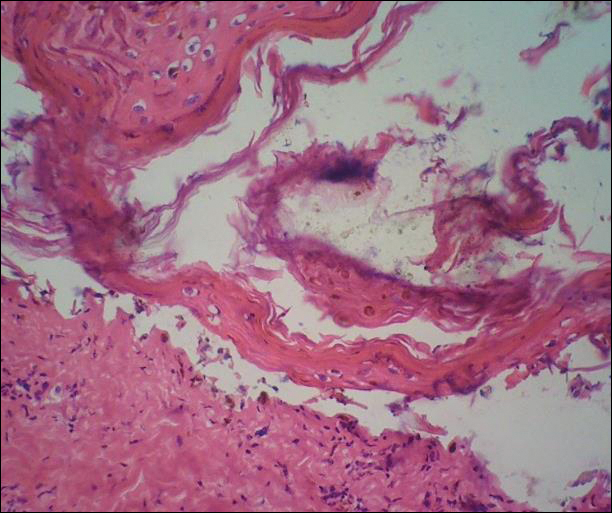

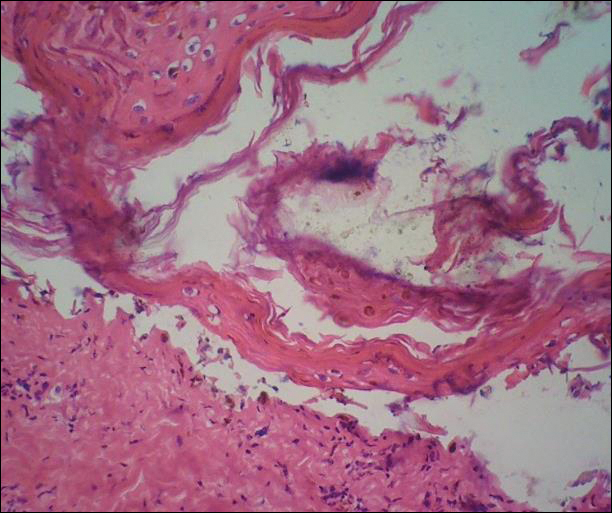

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit secondary to the acute development of an erythematous rash with tissue sloughing that involved acral sites and mucosal surfaces. Her medical history was notable for anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A (SS-A)–positive lupus erythematosus (LE) with a morphologic semblance to subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE). Prior treatment had included oral corticosteroids. In addition, she reported a concurrent history of acral and mucosal lesions that appeared to flare with her lupus. The nature of these lesions was not clear to the patient or her physicians. Before this particular episode, her primary care physician had attempted to wean her off of the corticosteroids. As she dropped below 20 mg of prednisone daily, new lesions developed. The patient stated that her social situation was poor and that these lesions did seem to develop more frequently during times of physical and emotional stress. She recounted her first episode developing during her second pregnancy. Oral prednisone and over-the-counter calcium with vitamin D were her only reported medications. She denied the use of any other medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and recent antibiotic therapy.

Dermatology was called in for consultation, and physical examination revealed areas of epidermal sloughing on the hands and feet. Complete clinical exposure of the underlying dermis was noted with remarkable tenderness. These lesions were noted to be in various stages of healing (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays a lesion in early development. The mucosal surfaces of the lips and eyes demonstrated hemorrhagic crusting, and some tissue sloughing was noted on the ears. A widespread erythematous exanthema with fine scaling was noted on the face, neck, chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs (Figure 3).

Laboratory evaluation revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B (SS-B) antibodies, and anti–double-stranded DNA. The hemoglobin level was 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL) and hematocrit was 28.8% (reference range, 36%–47%). The mean corpuscular hemoglobin level was 32 pg/cell (reference range, 27–31 pg/cell), and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration was 32.5 g/dL (reference range, 30–35 g/dL). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 IgM were all found to be negative.

A deep shave biopsy obtained from the patient’s right knee revealed an atrophic interface dermatitis associated with a lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis accompanied by abundant mesenchymal mucin deposition (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) from the same area demonstrated IgG and IgM along the dermoepidermal junction with some granular deposition. Frozen sections performed on acral lesions demonstrated epidermal necrosis (Figure 5). Direct immunofluorescence of acral lesions was negative. In light of these findings, a diagnosis of Rowell syndrome (RS) was suspected to be the most likely explanation for the presentation.

Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics were administered, and over a 2-week hospitalization, the lesions on the feet and hands slowly reepithelialized. Physical therapy was required to aid in ambulation. The patient was discharged on a tapering course of oral prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. After 6 months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, the patient continued to experience recurrent bouts of acral lesions, and pulse doses of oral prednisone were required. The lesions currently are controlled with azathioprine 50 mg twice daily and prednisone 10 mg by mouth daily.

Comment

The 4 prototypical patients identified by Rowell et al1 in 1963 in the first account of the eponymous syndrome were all females with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and perniosis. In addition, they all displayed positive RF and saline extract of human tissue antibodies (analogous to anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B).2 Since then, at least 132 patients with clinical symptoms suspicious of RS have been identified with variations on these original criteria.3 The reported permutations of the lupus component of the disease include cutaneous LE (CLE), bullous systemic LE, necrotic lesions associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, annular/polycyclic SCLE, systemic LE (SLE) without CLE, SLE with lupus nephritis, SLE with pericarditis, SLE with systemic vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis.2 In addition, variations of the erythema multiforme (EM)–like lesions found in reported cases include changes to their gross appearance (flat vs raised), location (acral or mucosal involvement), and resemblance to other conditions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis).2,3 From this information alone, it is clear that, as further cases have been chronicled, defining exact criteria for the disease has been challenging.

The essential question concerning the existence of RS hinges on the strength of its distinctiveness: Is it a unique disorder or merely another variant of lupus? Antiga et al2 concluded that it should be characterized as a variant of SCLE. Lee at al4 agreed, stating that “[i]n view of the lack of specific features that distinguish RS from LE, Kuhn et al5 suggested that [RS] is probably not a distinct entity and is now widely considered to be a variant of SCLE.” One of the primary contributors to this conclusion is that the laboratory findings of reported patients with SCLE have more closely mirrored the original cases from Rowell et al’s1 report than those of typical LE. Patients with SCLE have demonstrated positive ANA antibodies in 60% to 80% of cases, positive anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies in 40% to 100% of cases, positive anti-La/SS-B antibodies in 12% to 42% of cases, positive anti–double-stranded DNA in 1.2% to 10% of cases, and positive RF antibodies in 33% of cases.2 An argument could certainly be made to ascribe our patient’s condition to an SCLE variant, as 4 of 5 preceding laboratory findings were found to be positive; however, the majority of reported cases of SCLE have been linked to drugs (ie, hydrochlorothiazide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, terbinafine),2 which has not commonly been the attributable etiology of other cases of RS, including the 4 cases reported by Rowell et al.1

In a review of the literature on RS since 2010 in addition to their report of 132 new cases, Torchia et al3 outlined a set of diagnostic standards for the condition consisting of major and minor criteria. According to the authors, if all 4 major and 1 minor criteria are met, the patient meets the standards for true RS. The major criteria include the following: (1) presence of chronic CLE [DLE and/or chilblain]; (2) presence of EM-like lesions [typical or atypical targets]; (3) at least 1 positivity among speckled ANA, anti-Ro/SS-A, and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; and (4) negative DIF on lesional EM-like targetoid lesions. The minor criteria include the following: (1) absence of infectious or pharmacologic triggers; (2) absence of typical EM location (acral and mucosal); and (3) presence of at least 1 additional American College of Rheumatology criterion for diagnosis of SLE8 besides discoid rash and positive ANA antibodies and excluding photosensitivity, malar rash, and oral ulcers. Using these criteria, the patient in our case met the standards for diagnosis of RS.

One area of disagreement that has been encountered in the literature is the exact histologic determination of true RS, specifically related to the microscopic findings of the EM-like lesions. Two cases presented by Modi et al6 were interpreted under the stipulation that true RS must contain histologic LE and histologic EM. Because the EM-appearing lesions revealed LE histology, the cases were concluded to be variants of LE. These cases are similar to our case in that the EM-like lesions in our patient demonstrated LE pathology. Torchia et al,3 as demonstrated in the above criteria, seemed to be less concerned about the histology of the EM-like lesions, only requiring them to show negative DIF.

Conclusion

In the search for answers concerning RS, many unanswered questions remain: Where should the line be drawn in the inclusion of so many variations of both the LE and EM components of the condition? Also, should these elements even be approached as distinct components in the first place? Viewing the majority of RS cases as simply simultaneous LE and EM, Shteyngarts et al7 concluded that “the concomitant occurrence of EM with LE did not change the course, therapy, or prognosis of either disease. SLE and DLE can coexist with EM, but the coexistence does not impart any unusual characteristic to either illness. Rowell’s syndrome is not reproducible, and the immunologic disturbances in such patients are probably coincidental.”

If the condition is a genuine pathological individuality, should we not view the seemingly separate LE and EM as the product of a single underlying biochemical process? These questions and others in the search for a true definition of the disease should continue to be debated. It is clear that further investigation is warranted in the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the pathology.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Rowell NR, Beck JS, Anderson JR. Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions: a syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-180.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Bonciani D, et al. The last word on the so-called ‘Rowell’s syndrome’? Lupus. 2012;21:577-585.

- Torchia D, Romanelli P, Kerdel FA. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-421.

- Lee A, Batra P, Furer V, et al. Rowell syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus + erythema multiforme). Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Kuhn A, Sticherling M, Bonsmann G. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:1124-1140.

- Modi GM, Shen A, Mazloom A, et al. Lupus erythematosus masquerading as erythema multiforme: does Rowell syndrome really exist? Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:5.

- Shteyngarts AR, Warner MR, Camisa C. Lupus erythematosus associated with erythema multiforme: does Rowell’s syndrome exist? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 pt 1):773-777.

- Lupus diagnosis. Lupus Research Alliance website. http://lupusresearchinstitute.org/lupus-facts/lupus-diagnosis. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Practice Points

- Rowell syndrome (RS) is an often unrecognized unique presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- There have been a variety of historical criteria that have sought to characterize RS.

Chronic Diffuse Erythematous Papulonodules

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

A 29-year-old man from Saudi Arabia presented with slightly tender skin lesions occurring in crops every few months over the last 7 years. The lesions typically would occur on the inguinal area, lower abdomen, buttocks, thighs, or arms, resolving within a few weeks despite no treatment. The patient denied having systemic symptoms such as fevers, chills, sweats, chest pain, shortness of breath, or unexpected weight loss. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous papulonodules, some ulcerated with a superficial crust, grouped predominantly on the medial aspect of the right upper arm and left lower inguinal region. Isolated lesions also were present on the forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, abdomen, and thighs. The grouped papulonodules were intermixed with faint hyperpigmented macules indicative of prior lesions. No oral lesions were noted, and there was no marked axillary or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Genetic predisposition to hypercalcemia linked to CAD, MI

in a large mendelian randomization study published online July 25 in JAMA.

Each 0.5-mg rise in genetically predicted serum calcium concentration increased the odds of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction by about 25%, reported Susanna C. Larsson, Ph.D., of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and her associates. It remains unclear whether short- or medium-term calcium supplementation also increases the risk of these outcomes, they added.

Observational studies have linked high serum calcium with cardiovascular disease, but such studies are subject to confounding, the researchers noted. Randomized trials indicate that calcium supplementation might contribute to MI, but the trials are not designed to quantify long-term risks. Therefore, the investigators evaluated a proxy for lifelong hypercalcemia – six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been linked to high serum calcium, but not to other CAD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes, fasting glucose and insulin levels, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, major lipids, or hypertension (JAMA. 2017 Jul 25;318[4]:371-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8981).

To examine how these SNPs affect the risk of CAD and MI, the researchers analyzed summary statistics for 184,305 individuals from a meta-analysis of CAD genome-wide association studies (Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121-30), including 60,801 cases (of whom about 70% also had MI) and 123,504 controls.

Together, these six SNPs explained about 0.8% of variations in serum calcium levels. Each 0.5-mg/dL (about one standard deviation) increase in genetically predicted serum calcium level significantly increased the risk of CAD (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.45; P = .003) and MI (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05-1.46; P = .009). The genetic variant rs1801725 exerted the greatest effect on serum calcium levels, the investigators noted. This SNP affects the CASR gene, which encodes a calcium-sensing receptor that “plays a key role in calcium homeostasis.” However, four of the other five variants also had odds ratios above 1.0, and three had odds ratios above 1.25. A sensitivity analysis that excluded the CASR variant generated an identical odds ratio, although the confidence interval was wider. Studies of other risk factors for CAD have yielded odds ratios between 1.3 (triglyceride levels) and 1.7 (LDL cholesterol levels), the researchers noted.

A link between calcium supplementation and MI remains debatable. However, supplementation can lead to hypercalcemia and greater formation of insoluble calciprotein particles, the investigators said. Coronary artery disease might result from downstream effects on vascular calcification, vascular cells, blood coagulation pathways, or gene expression, but such mechanisms need more study, they added.

This analysis included men and women from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Estonia, Lebanon, China, Korea, India, Pakistan and Greece. Participants tended to be men in their 50s and 60s, but more than half of studies lacked data on age and sex. Nearly all participants were of white European ancestry.

Karolinska Institutet supported Dr. Larsson. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

in a large mendelian randomization study published online July 25 in JAMA.

Each 0.5-mg rise in genetically predicted serum calcium concentration increased the odds of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction by about 25%, reported Susanna C. Larsson, Ph.D., of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and her associates. It remains unclear whether short- or medium-term calcium supplementation also increases the risk of these outcomes, they added.

Observational studies have linked high serum calcium with cardiovascular disease, but such studies are subject to confounding, the researchers noted. Randomized trials indicate that calcium supplementation might contribute to MI, but the trials are not designed to quantify long-term risks. Therefore, the investigators evaluated a proxy for lifelong hypercalcemia – six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been linked to high serum calcium, but not to other CAD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes, fasting glucose and insulin levels, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, major lipids, or hypertension (JAMA. 2017 Jul 25;318[4]:371-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8981).

To examine how these SNPs affect the risk of CAD and MI, the researchers analyzed summary statistics for 184,305 individuals from a meta-analysis of CAD genome-wide association studies (Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121-30), including 60,801 cases (of whom about 70% also had MI) and 123,504 controls.

Together, these six SNPs explained about 0.8% of variations in serum calcium levels. Each 0.5-mg/dL (about one standard deviation) increase in genetically predicted serum calcium level significantly increased the risk of CAD (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.45; P = .003) and MI (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05-1.46; P = .009). The genetic variant rs1801725 exerted the greatest effect on serum calcium levels, the investigators noted. This SNP affects the CASR gene, which encodes a calcium-sensing receptor that “plays a key role in calcium homeostasis.” However, four of the other five variants also had odds ratios above 1.0, and three had odds ratios above 1.25. A sensitivity analysis that excluded the CASR variant generated an identical odds ratio, although the confidence interval was wider. Studies of other risk factors for CAD have yielded odds ratios between 1.3 (triglyceride levels) and 1.7 (LDL cholesterol levels), the researchers noted.

A link between calcium supplementation and MI remains debatable. However, supplementation can lead to hypercalcemia and greater formation of insoluble calciprotein particles, the investigators said. Coronary artery disease might result from downstream effects on vascular calcification, vascular cells, blood coagulation pathways, or gene expression, but such mechanisms need more study, they added.

This analysis included men and women from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Estonia, Lebanon, China, Korea, India, Pakistan and Greece. Participants tended to be men in their 50s and 60s, but more than half of studies lacked data on age and sex. Nearly all participants were of white European ancestry.

Karolinska Institutet supported Dr. Larsson. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

in a large mendelian randomization study published online July 25 in JAMA.

Each 0.5-mg rise in genetically predicted serum calcium concentration increased the odds of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction by about 25%, reported Susanna C. Larsson, Ph.D., of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, and her associates. It remains unclear whether short- or medium-term calcium supplementation also increases the risk of these outcomes, they added.

Observational studies have linked high serum calcium with cardiovascular disease, but such studies are subject to confounding, the researchers noted. Randomized trials indicate that calcium supplementation might contribute to MI, but the trials are not designed to quantify long-term risks. Therefore, the investigators evaluated a proxy for lifelong hypercalcemia – six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that have been linked to high serum calcium, but not to other CAD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes, fasting glucose and insulin levels, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, major lipids, or hypertension (JAMA. 2017 Jul 25;318[4]:371-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8981).

To examine how these SNPs affect the risk of CAD and MI, the researchers analyzed summary statistics for 184,305 individuals from a meta-analysis of CAD genome-wide association studies (Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121-30), including 60,801 cases (of whom about 70% also had MI) and 123,504 controls.

Together, these six SNPs explained about 0.8% of variations in serum calcium levels. Each 0.5-mg/dL (about one standard deviation) increase in genetically predicted serum calcium level significantly increased the risk of CAD (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.45; P = .003) and MI (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05-1.46; P = .009). The genetic variant rs1801725 exerted the greatest effect on serum calcium levels, the investigators noted. This SNP affects the CASR gene, which encodes a calcium-sensing receptor that “plays a key role in calcium homeostasis.” However, four of the other five variants also had odds ratios above 1.0, and three had odds ratios above 1.25. A sensitivity analysis that excluded the CASR variant generated an identical odds ratio, although the confidence interval was wider. Studies of other risk factors for CAD have yielded odds ratios between 1.3 (triglyceride levels) and 1.7 (LDL cholesterol levels), the researchers noted.

A link between calcium supplementation and MI remains debatable. However, supplementation can lead to hypercalcemia and greater formation of insoluble calciprotein particles, the investigators said. Coronary artery disease might result from downstream effects on vascular calcification, vascular cells, blood coagulation pathways, or gene expression, but such mechanisms need more study, they added.

This analysis included men and women from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Estonia, Lebanon, China, Korea, India, Pakistan and Greece. Participants tended to be men in their 50s and 60s, but more than half of studies lacked data on age and sex. Nearly all participants were of white European ancestry.

Karolinska Institutet supported Dr. Larsson. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Genetic predisposition to higher serum calcium levels was significantly associated with coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction.

Major finding: Each 0.5-mg per dL rise in serum calcium increased the odds of these outcomes by about 25% (odds ratios, 1.25 and 1.24, respectively).

Data source: A mendelian randomization study of 60,801 cases of coronary artery disease, 123,504 controls, and six single nucleotide polymorphisms linked to serum calcium but not to other risk factors for coronary artery disease.

Disclosures: Karolinska Institutet supported Dr. Larsson. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Hereditary Hypotrichosis Simplex of the Scalp

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.

A 7-year-old girl presented with gradual thinning of the scalp hair of 3 to 4 years’ duration. Her mother reported the patient had normal hair density at birth. Over the next several years, she was noted to have an inability to grow lengthy hair. At approximately 3 years of age, thinning of scalp hair was identified. There was no prior history of increased shedding, hypohidrosis, or tooth or nail abnormalities. Family history revealed fine hair in her older sister and fine thin hair at the frontal scalp in her mother. Her mother reported similar inability to grow lengthy hair. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated short blonde hair with diffuse thinning of the crown (Figure 1). The longest hair was approximately 10 cm in length. Follicular ostia were without erythema or scale but notably fewer in number on the crown. Eyebrows, eyelashes, teeth, and fingernails were without abnormalities. A hair pull test was negative and hair mount revealed normal bulb and shaft. Microscopy of hair shafts under polarized light was unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were obtained and submitted for vertical and horizontal sectioning. Sections demonstrated an intact epidermis, decreased follicle number, and small follicles with hypoplastic velluslike appearance (Figure 2). Fibrosis and inflammation were not seen; there was no increase in catagen or telogen hairs. Clinical and histopathological findings were consistent with HHS.

Hereditary hypotrichosis localized to the scalp was first described by Toribio and Quinones5 in 1974 in a large Spanish family presenting with normal scalp hair at birth followed by gradual diffuse hair loss. Hair loss that usually began in school-aged children with subsequent few fine hairs remaining on the scalp by the third decade of life was identified in these individuals.Eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic, axillary, and other truncal hairs were normal.5 Several similar cases of HHS localized to the scalp have since been reported.2,6 Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, with the exception of 1 reported sporadic case.3

Research on HHS has primarily focused on genetic analyses of several affected families. Betz et al7 mapped the gene for HHS to band 6p21.3 in 2 families of Danish origin and in the Spanish family initially described by Toribio and Quinones.5 Three years later, a nonsense mutation in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin was described.8 Despite these genetic advances, the pathogenesis of HHS and the role that corneodesmosin may play remain unclear.

Generalized forms of hypotrichosis (OMIM #605389) have long been reported and described as loss of scalp hair with involvement of eyebrows, eyelashes, and other body hair.9 Genetic studies have allowed for genome-wide linkage analysis, linking 3 families with this more generalized HHS phenotype to chromosome 18; specifically, an Italian family with sparse scalp and body hair but normal eyelashes and eyebrows,4 and 2 Pakistani families with thinning scalp hair and sparse truncal hair.10 A mutation in the APC downregulated 1 gene, APCDD1, also has been identified in these families.10 These genetic findings indicate that the generalized form of HHS is a distinct syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of HHS includes Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis, loose anagen hair syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and androgenetic alopecia. Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis usually presents as near-complete absence of scalp hair at birth, development of wiry twisted hair in childhood, and progressive alopecia.3 Loose anagen hair syndrome usually demonstrates a ruffled cuticle on hair pull test and remits in late childhood. Polarization of the hair shaft can identify patients with trichothiodystrophy. Follicular miniaturization may lead one to consider early-onset androgenetic alopecia in some patients.

There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.2,3,5 As with other hair loss disorders, wigs or additional over-the-counter cosmetic options may be considered.3 Currently, there are no known patient resources specific for HHS. Therefore, our patient’s family was referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation website (https://naaf.org/) for resources on discussing alopecia with school-aged children. The psychological impact of alopecia should not be overlooked and psychiatric referral should be provided, if needed. Examination of family members along with clinical monitoring are recommended. Genetic counseling also may be offered.3

- Rodríguez Díaz E, Fernández Blasco G, Martín Pascual A, et al. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Dermatology. 1995;191:139-141.

- Ibsen HH, Clemmensen OJ, Brandrup F. Familial hypotrichosis of the scalp. autosomal dominant inheritance in four generations. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:349-351.

- Cambiaghi S, Barbareschi M. A sporadic case of congenital hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp: difficulties in diagnosis and classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:301-304.

- Baumer A, Belli S, Trueb RM, et al. An autosomal dominant form of hereditary hypotrichosis simple maps to 18p11.32-p11.23 in an Italian family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:443-448.

- Toribio J, Quinones PA. Heredity hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:687-696.

- Kohn G, Metzker A. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp. Clin Genet. 1987;32:120-124.

- Betz RC, Lee YA, Bygum A, et al. A gene for hypotrichosis simplex of the scalp maps to chromosome 6p21.3. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1979-1983.

- Levy-Nissenbaum E, Betz R, Frydman M, et al. Hypotrichosis of the scalp is associated with nonsense mutations in CDSN encoding corneodesmosin. Nat Genet. 2003;34:151-153.

- Just M, Ribera M, Fuente MJ, et al. Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Dermatology. 1998;196:339-342.

- Shimomura Y, Agalliu D, Vonica A, et al. APCDD1 is a novel Wnt inhibitor mutated in hereditary hypotrichosis simplex. Nature. 2011;44:1043-1047.

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.

A 7-year-old girl presented with gradual thinning of the scalp hair of 3 to 4 years’ duration. Her mother reported the patient had normal hair density at birth. Over the next several years, she was noted to have an inability to grow lengthy hair. At approximately 3 years of age, thinning of scalp hair was identified. There was no prior history of increased shedding, hypohidrosis, or tooth or nail abnormalities. Family history revealed fine hair in her older sister and fine thin hair at the frontal scalp in her mother. Her mother reported similar inability to grow lengthy hair. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated short blonde hair with diffuse thinning of the crown (Figure 1). The longest hair was approximately 10 cm in length. Follicular ostia were without erythema or scale but notably fewer in number on the crown. Eyebrows, eyelashes, teeth, and fingernails were without abnormalities. A hair pull test was negative and hair mount revealed normal bulb and shaft. Microscopy of hair shafts under polarized light was unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were obtained and submitted for vertical and horizontal sectioning. Sections demonstrated an intact epidermis, decreased follicle number, and small follicles with hypoplastic velluslike appearance (Figure 2). Fibrosis and inflammation were not seen; there was no increase in catagen or telogen hairs. Clinical and histopathological findings were consistent with HHS.

Hereditary hypotrichosis localized to the scalp was first described by Toribio and Quinones5 in 1974 in a large Spanish family presenting with normal scalp hair at birth followed by gradual diffuse hair loss. Hair loss that usually began in school-aged children with subsequent few fine hairs remaining on the scalp by the third decade of life was identified in these individuals.Eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic, axillary, and other truncal hairs were normal.5 Several similar cases of HHS localized to the scalp have since been reported.2,6 Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, with the exception of 1 reported sporadic case.3

Research on HHS has primarily focused on genetic analyses of several affected families. Betz et al7 mapped the gene for HHS to band 6p21.3 in 2 families of Danish origin and in the Spanish family initially described by Toribio and Quinones.5 Three years later, a nonsense mutation in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin was described.8 Despite these genetic advances, the pathogenesis of HHS and the role that corneodesmosin may play remain unclear.

Generalized forms of hypotrichosis (OMIM #605389) have long been reported and described as loss of scalp hair with involvement of eyebrows, eyelashes, and other body hair.9 Genetic studies have allowed for genome-wide linkage analysis, linking 3 families with this more generalized HHS phenotype to chromosome 18; specifically, an Italian family with sparse scalp and body hair but normal eyelashes and eyebrows,4 and 2 Pakistani families with thinning scalp hair and sparse truncal hair.10 A mutation in the APC downregulated 1 gene, APCDD1, also has been identified in these families.10 These genetic findings indicate that the generalized form of HHS is a distinct syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of HHS includes Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis, loose anagen hair syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and androgenetic alopecia. Marie-Unna hereditary hypotrichosis usually presents as near-complete absence of scalp hair at birth, development of wiry twisted hair in childhood, and progressive alopecia.3 Loose anagen hair syndrome usually demonstrates a ruffled cuticle on hair pull test and remits in late childhood. Polarization of the hair shaft can identify patients with trichothiodystrophy. Follicular miniaturization may lead one to consider early-onset androgenetic alopecia in some patients.

There is no effective treatment of HHS. Due to potential phenotypic variation, patients should be counseled that they may experience progressive or possible total loss of scalp hair by the third decade of life.2,3,5 As with other hair loss disorders, wigs or additional over-the-counter cosmetic options may be considered.3 Currently, there are no known patient resources specific for HHS. Therefore, our patient’s family was referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation website (https://naaf.org/) for resources on discussing alopecia with school-aged children. The psychological impact of alopecia should not be overlooked and psychiatric referral should be provided, if needed. Examination of family members along with clinical monitoring are recommended. Genetic counseling also may be offered.3

To the Editor:

Hereditary hypotrichosis simplex (HHS)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 146520) is a rare form of hypotrichosis that typically presents in school-aged children as worsening hair loss localized to the scalp.1 Most patients are unaffected at birth and otherwise healthy without abnormalities of the nails, teeth, or perspiration. Examination of the scalp reveals normal follicular ostia and absence of scale and erythema; however, decreased follicular density may be noted.1 The histopathologic findings of HHS reveal velluslike hair follicles without associated fibrosis or inflammation.2 Examination of hair follicles with light microscopy is unremarkable.3,4 Historically, this condition has been largely regarded as autosomal dominant, with variable severity also described within families. Herein, we report a case of this rare disease in a child, with 2 family members displaying a less severe phenotype.