User login

Perifollicular Papules on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

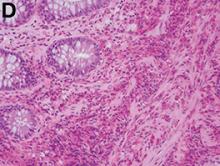

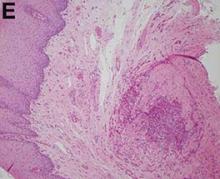

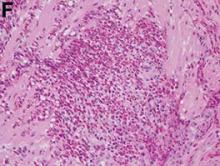

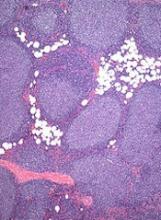

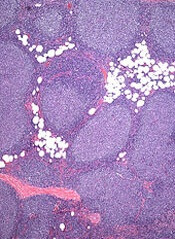

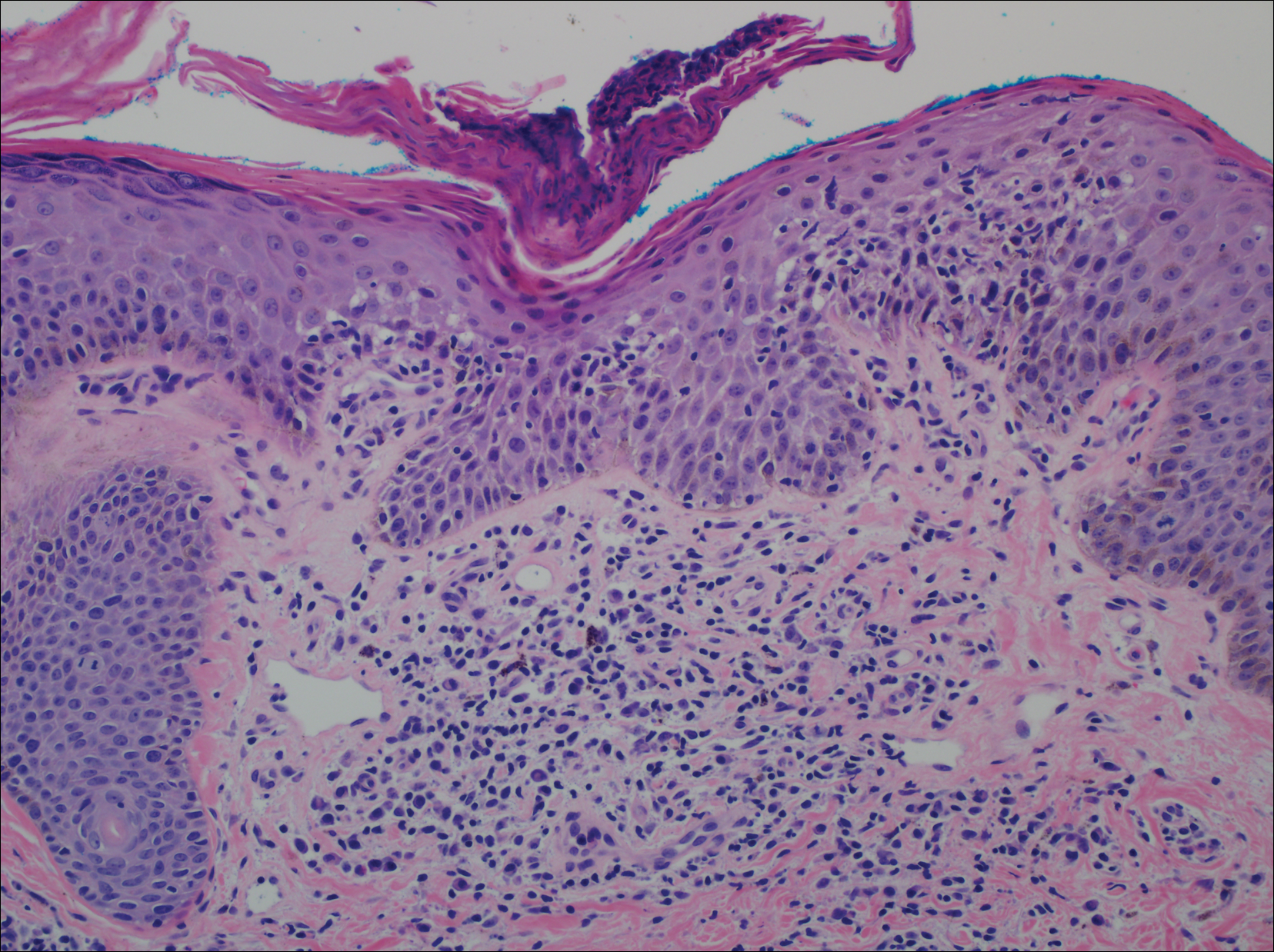

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

The Diagnosis: Disseminate and Recurrent Infundibulofolliculitis

A punch biopsy of a representative lesion on the trunk was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a chronic lymphohistiocytic proliferation, focal spongiosis, and lymphocytic exocytosis primarily involving the isthmus of the hair follicle (Figure 1). At the follicular opening there was associated parakeratosis of the adjacent epidermis (Figure 2). Given these clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis (DRIF) was made.

Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis was first described by Hitch and Lund1 in 1968 in a healthy 27-year-old black man as a widespread recurrent follicular eruption. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis usually affects young adult males with darkly pigmented skin.2,3 It has less commonly been described in children, females, and white individuals.3,4 Associations with atopy, systemic diseases, or medications are unknown.3-6 The onset usually is sudden and the disease course may be characterized by intermittent recurrences. Pruritus usually is reported but may be mild.5

Histopathology is characterized by spongiosis centered on the infundibulum of the hair follicle and a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Neutrophils also may be identified.3 Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis can be differentiated histologically from clinically similar entities such as keratosis pilaris, which has a keratin plug filling the infundibulum; lichen nitidus, which is characterized by a clawlike downgrowth of the rete ridges surrounding a central foci of inflammation; or folliculitis, which is characterized by perifollicular suppurative inflammation.

Treatment of DRIF is anecdotal and limited to case reports. Vitamin A alone or in combination with vitamin E has been reported to lead to some improvement.5 Tetracycline-class antibiotics, keratolytics, antihistamines, and topical retinoids have not been successful, and mixed results have been seen with topical steroids.5-7 There is a reported case of improvement with a 3-week regimen of psoralen plus UVA followed by twice-weekly maintenance.8 Promising results in the treatment of DRIF have been shown with oral isotretinoin once daily.3-5 Finally, DRIF may resolve independently6; therefore, treatment of DRIF should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:432-435.

- Hitch JM, Lund HZ. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulo-folliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:580-583.

- Calka O, Metin A, Ozen S. A case of disseminated and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with systemic isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 2002;29:431-434.

- Aroni K, Grapsa A, Agapitos E. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:434-435.

- Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Davaris P. Disseminated and recurrent infundibular folliculitis (D.R.I.F.): report of a case successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatol. 1998;25:51-53.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:174-175.

- Hinds GA, Heald PW. A case of disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis responsive to treatment with topical steroids. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

- Goihman-Yahr M. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis: response to psoralen plus UVA therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:75-78.

A 40-year-old black man presented with numerous perifollicular flesh-colored papules on the back, chest, abdomen, and proximal aspect of the arms of 6 years' duration. He described these lesions as persistent, nonpainful, and nonpruritic. He previously was treated with an unknown cream without any benefit. These lesions were cosmetically bothersome.

Hospitalists need critical care training pathway

Dear Editor,

It is with great interest that we read the article “Hospitalists trained in family medicine seek critical care training pathway” by Claudia Stahl.1 We would like to thank the authors for the article and at the same time emphasize the relevance and necessity of critical care knowledge for hospitalists taking care of critically ill patients.

It is a well-known fact that hospitalists provide an ICU level of services, especially in community hospitals. There are step-down or intermediate-care units across large hospitals, which also are staffed mostly by hospitalists. So we strongly support the family medicine track having a critical care training pathway, and at the same time encourage internal medicine graduates to pursue a critical care certification program. It not only is helpful, but at times also proven to be beneficial for hospitalists who care for critically ill patients to have critical care knowledge.

There was lot of excitement in 2012 when SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, 1-year, critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least 3 years of clinical job experience, instead of the 2-year fellowship.2 However, there was a quick backlash from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), who criticized the “inadequacy” of 1 year of fellowship training for HM physicians3, and so the excitement abated.

It may not be possible for hospitalists to take 2- to 3-year breaks from their career to pursue a critical care fellowship. There are certain courses, like Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) and critical care updates for hospitalists; however, the duration of these courses is not enough to give the exhaustive training that we need. Many hospitalists work week-on/week-off schedules, and we are willing to invest some of our off time to pursue a year-long course. We believe a year-long course, if structurally sound, might be able to teach the skill sets to provide quality care to our critically ill patients.

Considering the paucity of available critical care training, we believe there is a strong necessity to develop long-term critical care training targeted at hospitalists caring for critically ill patients. Whether you are a family medicine graduate, an internal medicine graduate, or an advanced practitioner, once you are a hospitalist you are a hospitalist for life – irrespective of your future practice – as you continuously strive for quality of patient care and patient safety and satisfaction.

Primary author

Venkatrao Medarametla, MBBS

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Medical Director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

[email protected]

Secondary authors

Prasanth Prabhakaran, MD

Sureshkumar Chirumamilla, MD

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

References

1. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/133078/hospitalists-trained-family-medicine-seek-critical-care-training-pathway

2. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

Dear Editor,

It is with great interest that we read the article “Hospitalists trained in family medicine seek critical care training pathway” by Claudia Stahl.1 We would like to thank the authors for the article and at the same time emphasize the relevance and necessity of critical care knowledge for hospitalists taking care of critically ill patients.

It is a well-known fact that hospitalists provide an ICU level of services, especially in community hospitals. There are step-down or intermediate-care units across large hospitals, which also are staffed mostly by hospitalists. So we strongly support the family medicine track having a critical care training pathway, and at the same time encourage internal medicine graduates to pursue a critical care certification program. It not only is helpful, but at times also proven to be beneficial for hospitalists who care for critically ill patients to have critical care knowledge.

There was lot of excitement in 2012 when SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, 1-year, critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least 3 years of clinical job experience, instead of the 2-year fellowship.2 However, there was a quick backlash from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), who criticized the “inadequacy” of 1 year of fellowship training for HM physicians3, and so the excitement abated.

It may not be possible for hospitalists to take 2- to 3-year breaks from their career to pursue a critical care fellowship. There are certain courses, like Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) and critical care updates for hospitalists; however, the duration of these courses is not enough to give the exhaustive training that we need. Many hospitalists work week-on/week-off schedules, and we are willing to invest some of our off time to pursue a year-long course. We believe a year-long course, if structurally sound, might be able to teach the skill sets to provide quality care to our critically ill patients.

Considering the paucity of available critical care training, we believe there is a strong necessity to develop long-term critical care training targeted at hospitalists caring for critically ill patients. Whether you are a family medicine graduate, an internal medicine graduate, or an advanced practitioner, once you are a hospitalist you are a hospitalist for life – irrespective of your future practice – as you continuously strive for quality of patient care and patient safety and satisfaction.

Primary author

Venkatrao Medarametla, MBBS

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Medical Director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

[email protected]

Secondary authors

Prasanth Prabhakaran, MD

Sureshkumar Chirumamilla, MD

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

References

1. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/133078/hospitalists-trained-family-medicine-seek-critical-care-training-pathway

2. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

Dear Editor,

It is with great interest that we read the article “Hospitalists trained in family medicine seek critical care training pathway” by Claudia Stahl.1 We would like to thank the authors for the article and at the same time emphasize the relevance and necessity of critical care knowledge for hospitalists taking care of critically ill patients.

It is a well-known fact that hospitalists provide an ICU level of services, especially in community hospitals. There are step-down or intermediate-care units across large hospitals, which also are staffed mostly by hospitalists. So we strongly support the family medicine track having a critical care training pathway, and at the same time encourage internal medicine graduates to pursue a critical care certification program. It not only is helpful, but at times also proven to be beneficial for hospitalists who care for critically ill patients to have critical care knowledge.

There was lot of excitement in 2012 when SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, 1-year, critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least 3 years of clinical job experience, instead of the 2-year fellowship.2 However, there was a quick backlash from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), who criticized the “inadequacy” of 1 year of fellowship training for HM physicians3, and so the excitement abated.

It may not be possible for hospitalists to take 2- to 3-year breaks from their career to pursue a critical care fellowship. There are certain courses, like Fundamental Critical Care Support (FCCS) and critical care updates for hospitalists; however, the duration of these courses is not enough to give the exhaustive training that we need. Many hospitalists work week-on/week-off schedules, and we are willing to invest some of our off time to pursue a year-long course. We believe a year-long course, if structurally sound, might be able to teach the skill sets to provide quality care to our critically ill patients.

Considering the paucity of available critical care training, we believe there is a strong necessity to develop long-term critical care training targeted at hospitalists caring for critically ill patients. Whether you are a family medicine graduate, an internal medicine graduate, or an advanced practitioner, once you are a hospitalist you are a hospitalist for life – irrespective of your future practice – as you continuously strive for quality of patient care and patient safety and satisfaction.

Primary author

Venkatrao Medarametla, MBBS

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Medical Director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

[email protected]

Secondary authors

Prasanth Prabhakaran, MD

Sureshkumar Chirumamilla, MD

Hospital Medicine, Baystate Medical Center

References

1. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/133078/hospitalists-trained-family-medicine-seek-critical-care-training-pathway

2. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

Clinical Challenges - June 2017 What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Ravi B. Parikh, MD, George A. Alba, MD, and Lawrence R. Zukerberg, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144;272, 467).

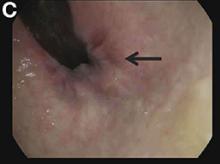

Upon admittance to the general medicine service, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. She did not have any stigmata of chronic liver disease. Her abdomen was distended and diffusely tender with rebound tenderness and guarding (Figure A). Serum studies were notable for white blood cell count of 14.5 x 103/microL, with 46% eosinophils (absolute count 6660/mm3). Other values, including serum human chorionic gonadotropin, were normal.

What is the diagnosis? What is the appropriate management?

Children and Teens at Rising Risk for Diabetes

Diabetes is on the rise among children and teens in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2012, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rose 1.8% annually and type 2 DM (T2DM) rose 4.8% annually, according to findings from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. The study involved 11,245 participants aged ≤ 19 years with T1 DM and 2,846 aged 10 to 19 years with T2DM.

Minority racial and ethnic groups saw the highest increases. The greatest rise (4.2%) in T1 DM was among Hispanics. The greatest increases of T2DM were in non-Hispanic blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. The annual rate among Native American youth was 8.9%, followed by 8.5% among Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, and 6.3% among non-Hispanic blacks. The researchers note that the results for Native Americans cannot be generalized to all Native American youth nationwide.

Across all ethnic/racial groups, T 1DM increased more each year in males (2.2%) than in females (1.4%). Type 2 DM, by contrast, increased twice as fast in girls as boys aged 10 to 19 years (6.2% vs 3.7%).

The study is the first to estimate trends in newly diagnosed cases of diabetes among people aged < 20 years from the 5 major racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

Diabetes is on the rise among children and teens in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2012, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rose 1.8% annually and type 2 DM (T2DM) rose 4.8% annually, according to findings from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. The study involved 11,245 participants aged ≤ 19 years with T1 DM and 2,846 aged 10 to 19 years with T2DM.

Minority racial and ethnic groups saw the highest increases. The greatest rise (4.2%) in T1 DM was among Hispanics. The greatest increases of T2DM were in non-Hispanic blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. The annual rate among Native American youth was 8.9%, followed by 8.5% among Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, and 6.3% among non-Hispanic blacks. The researchers note that the results for Native Americans cannot be generalized to all Native American youth nationwide.

Across all ethnic/racial groups, T 1DM increased more each year in males (2.2%) than in females (1.4%). Type 2 DM, by contrast, increased twice as fast in girls as boys aged 10 to 19 years (6.2% vs 3.7%).

The study is the first to estimate trends in newly diagnosed cases of diabetes among people aged < 20 years from the 5 major racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

Diabetes is on the rise among children and teens in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2012, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rose 1.8% annually and type 2 DM (T2DM) rose 4.8% annually, according to findings from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. The study involved 11,245 participants aged ≤ 19 years with T1 DM and 2,846 aged 10 to 19 years with T2DM.

Minority racial and ethnic groups saw the highest increases. The greatest rise (4.2%) in T1 DM was among Hispanics. The greatest increases of T2DM were in non-Hispanic blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. The annual rate among Native American youth was 8.9%, followed by 8.5% among Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, and 6.3% among non-Hispanic blacks. The researchers note that the results for Native Americans cannot be generalized to all Native American youth nationwide.

Across all ethnic/racial groups, T 1DM increased more each year in males (2.2%) than in females (1.4%). Type 2 DM, by contrast, increased twice as fast in girls as boys aged 10 to 19 years (6.2% vs 3.7%).

The study is the first to estimate trends in newly diagnosed cases of diabetes among people aged < 20 years from the 5 major racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

Sunny Side's Up

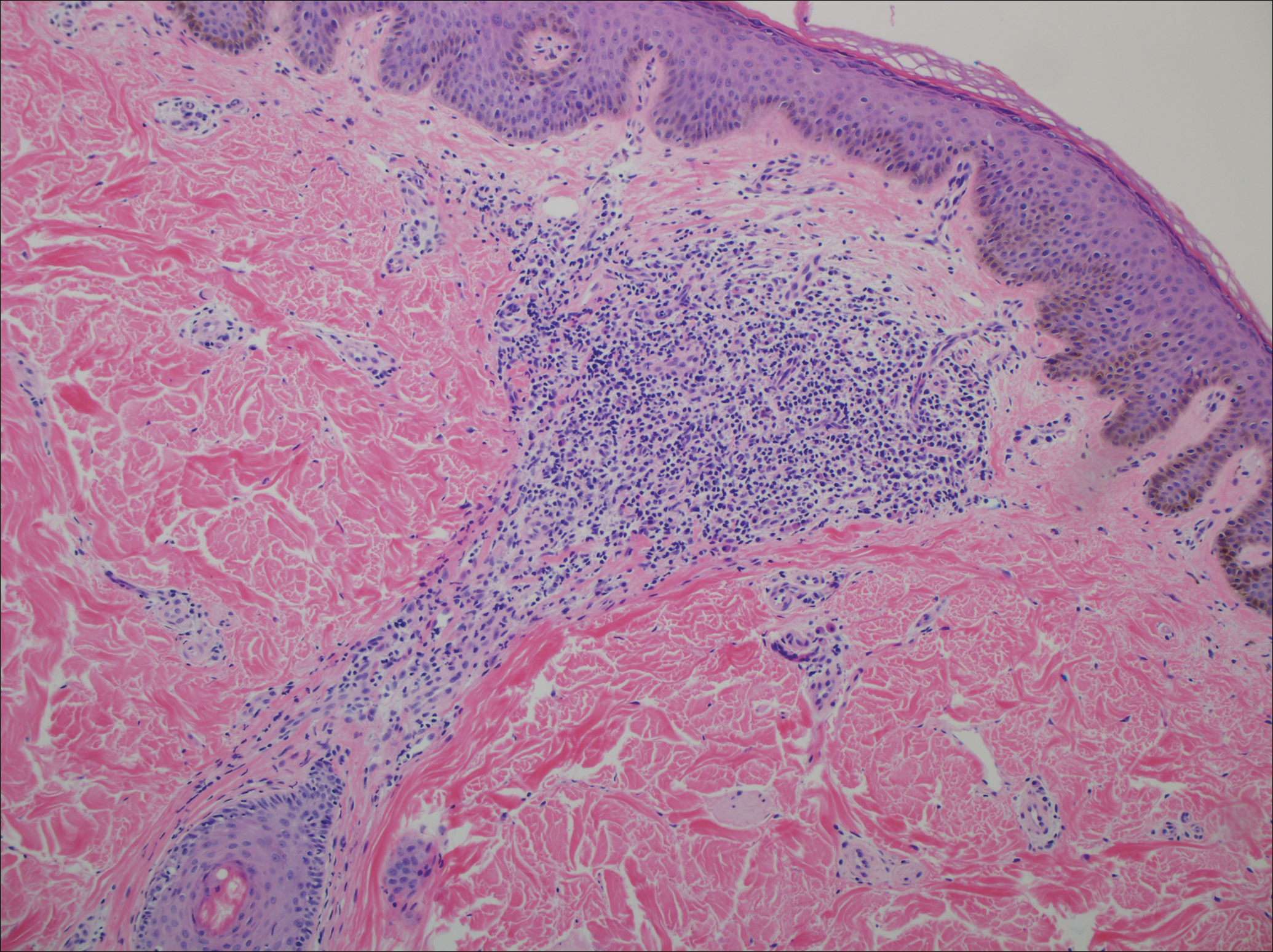

A year ago, this 60-year-old man noticed an asymptomatic lesion on the dorsum of his right hand. When it grew in size over the course of a few months, he showed it to his primary care provider, who believed it to be a wart and froze it with liquid nitrogen. This reduced its size, but only temporarily. It has since been treated with topical and oral antibiotics to no avail.

The patient has had several basal cell carcinomas removed from his face, arms, and trunk in the past.

EXAMINATION

On the mid dorsum of the patient’s right hand is a 1.5-cm ovoid nodule with a smooth surface and very firm feel. It appears in the context of fully sun-exposed, sun-damaged skin. Several scars are noted in the area, consistent with his history of sun-caused skin cancers.

The lesion is removed by deep shave biopsy, and the base curetted. The entire lesion is sent to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report shows a low-grade, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—in this case, a keratoacanthoma (KA). This common form of SCC is usually found on the sun-exposed skin of older patients. The lesions can range in size from 3 mm to 3 cm or larger and are usually round to oval and dome-like, with symmetrical architecture and, often, a central keratotic core. The differential includes cysts, warts, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, KAs are composed of uniformly staining (blue) cells of similar size and shape (connoting relative benignancy), to which we apply the term well-differentiated. Poorly-differentiated cellular composition manifests with cells of different sizes, shapes, and colors; these characteristics suggest more aggressive malignancy.

Even though KAs are skin cancers, they are quite low-grade, which means they rarely metastasize; if left alone, they can resolve completely over time. However, their odd appearance and rapid growth are usually concerning enough to prompt their removal.

When suspected KAs are removed, it’s essential that the entire lesion be submitted for pathologic examination. This allows for the architecture of the entire lesion—its cellular composition and margins—to be evaluated. When only part of the lesion is removed for biopsy, the diagnosis will be “squamous cell carcinoma, well differentiated, without evidence of invasion.” In the minds of many dermatology providers, this diagnosis demands excision—but a KA lesion completely removed by shave biopsy is considered cured.

Histologic examination of these lesions is not always as straightforward as in this case. KAs can be poorly differentiated or demonstrate focal areas of invasion, which justifies excision with margins.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratoacanthoma (KA) is an extremely common low-grade squamous cell carcinoma most often seen on directly sun-exposed skin (eg, hands, arms, face, ears) of older, sun-damaged patients.

- KA typically manifests as a round to oval, dome-like, firm nodule, often with a central keratotic core and a history of rapid growth.

- It’s important to remove these lesions in one piece (eg, by deep shave biopsy) because identification is based on architecture and cellular composition.

- The pathology report will show a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with architecture consistent with KA.

- Although some believe that excision is necessary, a deep shave biopsy performed with clear margins is adequate treatment.

A year ago, this 60-year-old man noticed an asymptomatic lesion on the dorsum of his right hand. When it grew in size over the course of a few months, he showed it to his primary care provider, who believed it to be a wart and froze it with liquid nitrogen. This reduced its size, but only temporarily. It has since been treated with topical and oral antibiotics to no avail.

The patient has had several basal cell carcinomas removed from his face, arms, and trunk in the past.

EXAMINATION

On the mid dorsum of the patient’s right hand is a 1.5-cm ovoid nodule with a smooth surface and very firm feel. It appears in the context of fully sun-exposed, sun-damaged skin. Several scars are noted in the area, consistent with his history of sun-caused skin cancers.

The lesion is removed by deep shave biopsy, and the base curetted. The entire lesion is sent to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report shows a low-grade, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—in this case, a keratoacanthoma (KA). This common form of SCC is usually found on the sun-exposed skin of older patients. The lesions can range in size from 3 mm to 3 cm or larger and are usually round to oval and dome-like, with symmetrical architecture and, often, a central keratotic core. The differential includes cysts, warts, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, KAs are composed of uniformly staining (blue) cells of similar size and shape (connoting relative benignancy), to which we apply the term well-differentiated. Poorly-differentiated cellular composition manifests with cells of different sizes, shapes, and colors; these characteristics suggest more aggressive malignancy.

Even though KAs are skin cancers, they are quite low-grade, which means they rarely metastasize; if left alone, they can resolve completely over time. However, their odd appearance and rapid growth are usually concerning enough to prompt their removal.

When suspected KAs are removed, it’s essential that the entire lesion be submitted for pathologic examination. This allows for the architecture of the entire lesion—its cellular composition and margins—to be evaluated. When only part of the lesion is removed for biopsy, the diagnosis will be “squamous cell carcinoma, well differentiated, without evidence of invasion.” In the minds of many dermatology providers, this diagnosis demands excision—but a KA lesion completely removed by shave biopsy is considered cured.

Histologic examination of these lesions is not always as straightforward as in this case. KAs can be poorly differentiated or demonstrate focal areas of invasion, which justifies excision with margins.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratoacanthoma (KA) is an extremely common low-grade squamous cell carcinoma most often seen on directly sun-exposed skin (eg, hands, arms, face, ears) of older, sun-damaged patients.

- KA typically manifests as a round to oval, dome-like, firm nodule, often with a central keratotic core and a history of rapid growth.

- It’s important to remove these lesions in one piece (eg, by deep shave biopsy) because identification is based on architecture and cellular composition.

- The pathology report will show a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with architecture consistent with KA.

- Although some believe that excision is necessary, a deep shave biopsy performed with clear margins is adequate treatment.

A year ago, this 60-year-old man noticed an asymptomatic lesion on the dorsum of his right hand. When it grew in size over the course of a few months, he showed it to his primary care provider, who believed it to be a wart and froze it with liquid nitrogen. This reduced its size, but only temporarily. It has since been treated with topical and oral antibiotics to no avail.

The patient has had several basal cell carcinomas removed from his face, arms, and trunk in the past.

EXAMINATION

On the mid dorsum of the patient’s right hand is a 1.5-cm ovoid nodule with a smooth surface and very firm feel. It appears in the context of fully sun-exposed, sun-damaged skin. Several scars are noted in the area, consistent with his history of sun-caused skin cancers.

The lesion is removed by deep shave biopsy, and the base curetted. The entire lesion is sent to pathology.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report shows a low-grade, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—in this case, a keratoacanthoma (KA). This common form of SCC is usually found on the sun-exposed skin of older patients. The lesions can range in size from 3 mm to 3 cm or larger and are usually round to oval and dome-like, with symmetrical architecture and, often, a central keratotic core. The differential includes cysts, warts, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, KAs are composed of uniformly staining (blue) cells of similar size and shape (connoting relative benignancy), to which we apply the term well-differentiated. Poorly-differentiated cellular composition manifests with cells of different sizes, shapes, and colors; these characteristics suggest more aggressive malignancy.

Even though KAs are skin cancers, they are quite low-grade, which means they rarely metastasize; if left alone, they can resolve completely over time. However, their odd appearance and rapid growth are usually concerning enough to prompt their removal.

When suspected KAs are removed, it’s essential that the entire lesion be submitted for pathologic examination. This allows for the architecture of the entire lesion—its cellular composition and margins—to be evaluated. When only part of the lesion is removed for biopsy, the diagnosis will be “squamous cell carcinoma, well differentiated, without evidence of invasion.” In the minds of many dermatology providers, this diagnosis demands excision—but a KA lesion completely removed by shave biopsy is considered cured.

Histologic examination of these lesions is not always as straightforward as in this case. KAs can be poorly differentiated or demonstrate focal areas of invasion, which justifies excision with margins.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratoacanthoma (KA) is an extremely common low-grade squamous cell carcinoma most often seen on directly sun-exposed skin (eg, hands, arms, face, ears) of older, sun-damaged patients.

- KA typically manifests as a round to oval, dome-like, firm nodule, often with a central keratotic core and a history of rapid growth.

- It’s important to remove these lesions in one piece (eg, by deep shave biopsy) because identification is based on architecture and cellular composition.

- The pathology report will show a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with architecture consistent with KA.

- Although some believe that excision is necessary, a deep shave biopsy performed with clear margins is adequate treatment.

Single-cell analysis reveals TKI-resistant CML stem cells

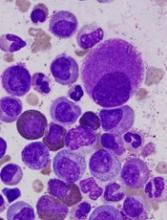

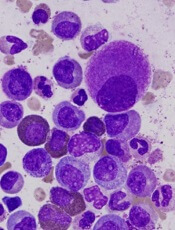

Researchers say they’ve developed a technique for single-cell analysis that has revealed a population of treatment-resistant stem cells in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

“It is increasingly recognized that tumors contain a variety of different cell types, including so-called cancer stem cells, that drive the growth and relapse of a patient’s cancer,” said study author Adam Mead, BM BCh, PhD, of University of Oxford in the UK.

“These cells can be very rare and extremely difficult to find after treatment as they become hidden within the normal tissue. We used a new genetic technique to identify and analyze single cancer stem cells in leukemia patients before and after treatment.”

Dr Mead and his colleagues detailed this research in Nature Medicine.

The team’s single-cell analysis technique combines high-sensitivity mutation detection with whole-transcriptome analysis.

The researchers used the method to analyze stem cells from patients with CML and found the cells to be heterogeneous.

In addition, the team was able to identify a subset of CML stem cells that proved resistant to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

“We found that, even in individual cases of leukemia, there are various types of cancer stem cell that respond differently to the treatment,” Dr Mead said.

“A small number of these cells are highly resistant to the treatment and are likely to be responsible for disease recurrence when the treatment is stopped. Our research allowed us uniquely to analyze these crucial cells that evade treatment so that we might learn how to more effectively eradicate them.”

The researchers said these TKI-resistant CML stem cells were “transcriptionally distinct” from normal hematopoietic stem cells.

The TKI-resistant cells were characterized by dysregulation of specific genes and pathways—TGF-β, TNF-α, JAK–STAT, CTNNB1, and NFKB1A—that could potentially be targeted to improve the treatment of CML.

The researchers also said their single-cell analysis technique can be used beyond CML.

“This technique could be adapted to analyze a range of different cancers to help predict both the likely response to treatment and the risk of the disease returning in the future,” Dr Mead said. “This should eventually enable treatment to be tailored to target each and every type of cancer stem cell that may be present.” ![]()

Researchers say they’ve developed a technique for single-cell analysis that has revealed a population of treatment-resistant stem cells in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

“It is increasingly recognized that tumors contain a variety of different cell types, including so-called cancer stem cells, that drive the growth and relapse of a patient’s cancer,” said study author Adam Mead, BM BCh, PhD, of University of Oxford in the UK.

“These cells can be very rare and extremely difficult to find after treatment as they become hidden within the normal tissue. We used a new genetic technique to identify and analyze single cancer stem cells in leukemia patients before and after treatment.”

Dr Mead and his colleagues detailed this research in Nature Medicine.

The team’s single-cell analysis technique combines high-sensitivity mutation detection with whole-transcriptome analysis.

The researchers used the method to analyze stem cells from patients with CML and found the cells to be heterogeneous.

In addition, the team was able to identify a subset of CML stem cells that proved resistant to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

“We found that, even in individual cases of leukemia, there are various types of cancer stem cell that respond differently to the treatment,” Dr Mead said.

“A small number of these cells are highly resistant to the treatment and are likely to be responsible for disease recurrence when the treatment is stopped. Our research allowed us uniquely to analyze these crucial cells that evade treatment so that we might learn how to more effectively eradicate them.”

The researchers said these TKI-resistant CML stem cells were “transcriptionally distinct” from normal hematopoietic stem cells.

The TKI-resistant cells were characterized by dysregulation of specific genes and pathways—TGF-β, TNF-α, JAK–STAT, CTNNB1, and NFKB1A—that could potentially be targeted to improve the treatment of CML.

The researchers also said their single-cell analysis technique can be used beyond CML.

“This technique could be adapted to analyze a range of different cancers to help predict both the likely response to treatment and the risk of the disease returning in the future,” Dr Mead said. “This should eventually enable treatment to be tailored to target each and every type of cancer stem cell that may be present.” ![]()

Researchers say they’ve developed a technique for single-cell analysis that has revealed a population of treatment-resistant stem cells in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

“It is increasingly recognized that tumors contain a variety of different cell types, including so-called cancer stem cells, that drive the growth and relapse of a patient’s cancer,” said study author Adam Mead, BM BCh, PhD, of University of Oxford in the UK.

“These cells can be very rare and extremely difficult to find after treatment as they become hidden within the normal tissue. We used a new genetic technique to identify and analyze single cancer stem cells in leukemia patients before and after treatment.”

Dr Mead and his colleagues detailed this research in Nature Medicine.

The team’s single-cell analysis technique combines high-sensitivity mutation detection with whole-transcriptome analysis.

The researchers used the method to analyze stem cells from patients with CML and found the cells to be heterogeneous.

In addition, the team was able to identify a subset of CML stem cells that proved resistant to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

“We found that, even in individual cases of leukemia, there are various types of cancer stem cell that respond differently to the treatment,” Dr Mead said.

“A small number of these cells are highly resistant to the treatment and are likely to be responsible for disease recurrence when the treatment is stopped. Our research allowed us uniquely to analyze these crucial cells that evade treatment so that we might learn how to more effectively eradicate them.”

The researchers said these TKI-resistant CML stem cells were “transcriptionally distinct” from normal hematopoietic stem cells.

The TKI-resistant cells were characterized by dysregulation of specific genes and pathways—TGF-β, TNF-α, JAK–STAT, CTNNB1, and NFKB1A—that could potentially be targeted to improve the treatment of CML.

The researchers also said their single-cell analysis technique can be used beyond CML.

“This technique could be adapted to analyze a range of different cancers to help predict both the likely response to treatment and the risk of the disease returning in the future,” Dr Mead said. “This should eventually enable treatment to be tailored to target each and every type of cancer stem cell that may be present.” ![]()

First generic version of clofarabine available in US

Clofarabine Injection, the first-to-market generic version of Sanofi Genzyme’s Clolar, is now available in the US.

The generic, a product of Fresenius Kabi, is available as a single dose vial containing 20 mg per 20 mL clofarabine.

Clofarabine is a purine nucleoside metabolic inhibitor indicated for the treatment of patients ages 1 to 21 with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Clolar was granted accelerated approval for this indication in the US in 2004.

The approval was based on response rates observed in ALL patients. There are no trials verifying that clofarabine confers improvement in survival or disease-related symptoms in ALL patients.

Clofarabine was assessed in a single-arm, phase 2 trial of 61 pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory ALL.

The patients’ median age was 12 (range, 1 to 20 years), and their median number of prior treatment regimens was 3 (range, 2 to 6).

The patients received clofarabine at 52 mg/m2 intravenously over 2 hours daily for 5 days, every 2 to 6 weeks.

The overall response rate was 30%. Seven patient achieved a complete response (CR), 5 had a CR without platelet recovery, and 6 patients had a partial response.

The median duration of CR in patients who did not go on to hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 6 weeks.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were febrile neutropenia, anorexia, hypotension, and nausea.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2006. ![]()

Clofarabine Injection, the first-to-market generic version of Sanofi Genzyme’s Clolar, is now available in the US.

The generic, a product of Fresenius Kabi, is available as a single dose vial containing 20 mg per 20 mL clofarabine.

Clofarabine is a purine nucleoside metabolic inhibitor indicated for the treatment of patients ages 1 to 21 with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Clolar was granted accelerated approval for this indication in the US in 2004.

The approval was based on response rates observed in ALL patients. There are no trials verifying that clofarabine confers improvement in survival or disease-related symptoms in ALL patients.

Clofarabine was assessed in a single-arm, phase 2 trial of 61 pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory ALL.

The patients’ median age was 12 (range, 1 to 20 years), and their median number of prior treatment regimens was 3 (range, 2 to 6).

The patients received clofarabine at 52 mg/m2 intravenously over 2 hours daily for 5 days, every 2 to 6 weeks.

The overall response rate was 30%. Seven patient achieved a complete response (CR), 5 had a CR without platelet recovery, and 6 patients had a partial response.

The median duration of CR in patients who did not go on to hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 6 weeks.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were febrile neutropenia, anorexia, hypotension, and nausea.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2006. ![]()

Clofarabine Injection, the first-to-market generic version of Sanofi Genzyme’s Clolar, is now available in the US.

The generic, a product of Fresenius Kabi, is available as a single dose vial containing 20 mg per 20 mL clofarabine.

Clofarabine is a purine nucleoside metabolic inhibitor indicated for the treatment of patients ages 1 to 21 with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Clolar was granted accelerated approval for this indication in the US in 2004.

The approval was based on response rates observed in ALL patients. There are no trials verifying that clofarabine confers improvement in survival or disease-related symptoms in ALL patients.

Clofarabine was assessed in a single-arm, phase 2 trial of 61 pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory ALL.

The patients’ median age was 12 (range, 1 to 20 years), and their median number of prior treatment regimens was 3 (range, 2 to 6).

The patients received clofarabine at 52 mg/m2 intravenously over 2 hours daily for 5 days, every 2 to 6 weeks.

The overall response rate was 30%. Seven patient achieved a complete response (CR), 5 had a CR without platelet recovery, and 6 patients had a partial response.

The median duration of CR in patients who did not go on to hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 6 weeks.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were febrile neutropenia, anorexia, hypotension, and nausea.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2006. ![]()

FDA grants priority review to NDA for copanlisib

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to the new drug application (NDA) for copanlisib, an intravenous PI3K inhibitor.

The NDA is for copanlisib as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior therapies.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The application for copanlisib is supported by data from the CHRONOS-1 trial. This phase 2 trial enrolled 141 patients with relapsed/refractory, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Most of these patients had FL (n=104).

In all patients, copanlisib produced an objective response rate of 59.2%, with a complete response rate of 12%. The median duration of response exceeded 98 weeks.

In the FL subset, copanlisib produced an overall response rate of 58.7%, with a complete response rate of 14.4%. The median duration of response exceeded 52 weeks.

In the entire cohort, there were 3 deaths considered related to copanlisib.

The most common treatment-related adverse events were transient hyperglycemia (all grades: 49%/grade 3-4: 40%) and hypertension (all grades: 29%/grade 3: 23%).

“Patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma have a poor prognosis, and new treatment options which are well tolerated and effective are needed to prolong progression-free survival and improve quality of life for these patients,” said Martin Dreyling, MD, a professor at the University of Munich Hospital (Grosshadern) in Germany and lead investigator of the CHRONOS-1 study.

“Based on the CHRONOS-1 results, where copanlisib showed durable efficacy with a manageable and distinct safety profile, the compound may have the potential to address this unmet medical need.”

Data from CHRONOS-1 were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Data from the FL subset of the trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting in June.

Copanlisib is being developed by Bayer. The compound has fast track and orphan drug designations from the FDA.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the NDA or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to the new drug application (NDA) for copanlisib, an intravenous PI3K inhibitor.

The NDA is for copanlisib as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior therapies.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The application for copanlisib is supported by data from the CHRONOS-1 trial. This phase 2 trial enrolled 141 patients with relapsed/refractory, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Most of these patients had FL (n=104).

In all patients, copanlisib produced an objective response rate of 59.2%, with a complete response rate of 12%. The median duration of response exceeded 98 weeks.

In the FL subset, copanlisib produced an overall response rate of 58.7%, with a complete response rate of 14.4%. The median duration of response exceeded 52 weeks.

In the entire cohort, there were 3 deaths considered related to copanlisib.

The most common treatment-related adverse events were transient hyperglycemia (all grades: 49%/grade 3-4: 40%) and hypertension (all grades: 29%/grade 3: 23%).

“Patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma have a poor prognosis, and new treatment options which are well tolerated and effective are needed to prolong progression-free survival and improve quality of life for these patients,” said Martin Dreyling, MD, a professor at the University of Munich Hospital (Grosshadern) in Germany and lead investigator of the CHRONOS-1 study.

“Based on the CHRONOS-1 results, where copanlisib showed durable efficacy with a manageable and distinct safety profile, the compound may have the potential to address this unmet medical need.”

Data from CHRONOS-1 were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Data from the FL subset of the trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting in June.

Copanlisib is being developed by Bayer. The compound has fast track and orphan drug designations from the FDA.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the NDA or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to the new drug application (NDA) for copanlisib, an intravenous PI3K inhibitor.

The NDA is for copanlisib as a treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior therapies.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The application for copanlisib is supported by data from the CHRONOS-1 trial. This phase 2 trial enrolled 141 patients with relapsed/refractory, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Most of these patients had FL (n=104).

In all patients, copanlisib produced an objective response rate of 59.2%, with a complete response rate of 12%. The median duration of response exceeded 98 weeks.

In the FL subset, copanlisib produced an overall response rate of 58.7%, with a complete response rate of 14.4%. The median duration of response exceeded 52 weeks.

In the entire cohort, there were 3 deaths considered related to copanlisib.

The most common treatment-related adverse events were transient hyperglycemia (all grades: 49%/grade 3-4: 40%) and hypertension (all grades: 29%/grade 3: 23%).

“Patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma have a poor prognosis, and new treatment options which are well tolerated and effective are needed to prolong progression-free survival and improve quality of life for these patients,” said Martin Dreyling, MD, a professor at the University of Munich Hospital (Grosshadern) in Germany and lead investigator of the CHRONOS-1 study.

“Based on the CHRONOS-1 results, where copanlisib showed durable efficacy with a manageable and distinct safety profile, the compound may have the potential to address this unmet medical need.”

Data from CHRONOS-1 were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Data from the FL subset of the trial are scheduled to be presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting in June.

Copanlisib is being developed by Bayer. The compound has fast track and orphan drug designations from the FDA.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the NDA or biologic license application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA. ![]()

Itchy rash on forearms

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Alternating therapy in renal cell carcinoma fails to show an advantage

There was no efficacy or safety advantage for alternating everolimus with pazopanib over pazopanib alone in patients with metastatic or locally advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), according to a newly published randomized trial.

The study hypothesis was that alternating the two drugs would improve outcomes and reduce toxicity, but differences between arms for the major outcomes were not clinically significant, according to results of a multicenter trial led by Geert A. Cirkel, MD, of the department of medical oncology, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Investigators randomized 101 patients with histologically confirmed ccRCC to receive 8 weeks of pazopanib in a daily dose of 800 mg alternated with 8 weeks of everolimus in a daily dose of 10 mg or 800 mg per day of continuous pazopanib. Patients remained on either regimen until disease progression.

Median time until first progression or death was 7.4 months for the experimental alternating arm versus 9.4 months for the control arm of continuous single-agent pazopanib (P = .37), Dr. Cirkel and associates reported (JAMA Onc. 2017 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5202).

Progression-free survival after starting on a second-line therapy was 20.2 months for the alternating treatment vs. 14.5 months for the control, but the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference was not significant (P = .86).

There was no apparent toxicity or tolerability advantage from alternating therapy. Nearly 40% of patients in both arms required pazopanib dose reductions, while 14% in the alternating arm also required an everolimus dose reduction. The incidence of serious adverse events possibly related to treatment was comparable between arms.

Quality of life was measured with several tools, including the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Kidney Symptom Index Disease-Related Symptoms (FKSI-DRS), but no significant differences between treatment arms were observed in any measure.

Current guidelines recommend pazopanib, which is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, as a first-line therapy in ccRCC. Everolimus, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, is recommended in the second-line setting. Noting that resistance to pazopanib has been shown to be reversible after a period of withdrawal in experimental studies, the authors had speculated an on-off strategy with everolimus might better preserve the efficacy of pazopanib, providing longer periods of disease control. They had also hypothesized that the cumulative adverse events might be less if the drugs were sequenced, allowing recovery from each set of drug-specific adverse events.

Several potential explanations were offered for the lack of improved efficacy from alternating everolimus with pazopanib. For one, the improved activity of pazopanib after withdrawal in experimental models was observed after drug-free periods. The authors questioned whether a period of tumor regrowth may be needed in order to overcome pazopanib resistance.

The study may still have supported the use of an alternating regimen if the alternating therapy had led to a significantly improved quality of life, but the authors found none, a outcome that they characterized as unexpected. They concluded that there are no apparent advantages for the alternating regimen of pazopanib and everolimus relative to pazopanib alone.

There was no efficacy or safety advantage for alternating everolimus with pazopanib over pazopanib alone in patients with metastatic or locally advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), according to a newly published randomized trial.

The study hypothesis was that alternating the two drugs would improve outcomes and reduce toxicity, but differences between arms for the major outcomes were not clinically significant, according to results of a multicenter trial led by Geert A. Cirkel, MD, of the department of medical oncology, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Investigators randomized 101 patients with histologically confirmed ccRCC to receive 8 weeks of pazopanib in a daily dose of 800 mg alternated with 8 weeks of everolimus in a daily dose of 10 mg or 800 mg per day of continuous pazopanib. Patients remained on either regimen until disease progression.

Median time until first progression or death was 7.4 months for the experimental alternating arm versus 9.4 months for the control arm of continuous single-agent pazopanib (P = .37), Dr. Cirkel and associates reported (JAMA Onc. 2017 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5202).

Progression-free survival after starting on a second-line therapy was 20.2 months for the alternating treatment vs. 14.5 months for the control, but the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference was not significant (P = .86).

There was no apparent toxicity or tolerability advantage from alternating therapy. Nearly 40% of patients in both arms required pazopanib dose reductions, while 14% in the alternating arm also required an everolimus dose reduction. The incidence of serious adverse events possibly related to treatment was comparable between arms.

Quality of life was measured with several tools, including the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Kidney Symptom Index Disease-Related Symptoms (FKSI-DRS), but no significant differences between treatment arms were observed in any measure.

Current guidelines recommend pazopanib, which is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, as a first-line therapy in ccRCC. Everolimus, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, is recommended in the second-line setting. Noting that resistance to pazopanib has been shown to be reversible after a period of withdrawal in experimental studies, the authors had speculated an on-off strategy with everolimus might better preserve the efficacy of pazopanib, providing longer periods of disease control. They had also hypothesized that the cumulative adverse events might be less if the drugs were sequenced, allowing recovery from each set of drug-specific adverse events.

Several potential explanations were offered for the lack of improved efficacy from alternating everolimus with pazopanib. For one, the improved activity of pazopanib after withdrawal in experimental models was observed after drug-free periods. The authors questioned whether a period of tumor regrowth may be needed in order to overcome pazopanib resistance.

The study may still have supported the use of an alternating regimen if the alternating therapy had led to a significantly improved quality of life, but the authors found none, a outcome that they characterized as unexpected. They concluded that there are no apparent advantages for the alternating regimen of pazopanib and everolimus relative to pazopanib alone.

There was no efficacy or safety advantage for alternating everolimus with pazopanib over pazopanib alone in patients with metastatic or locally advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), according to a newly published randomized trial.

The study hypothesis was that alternating the two drugs would improve outcomes and reduce toxicity, but differences between arms for the major outcomes were not clinically significant, according to results of a multicenter trial led by Geert A. Cirkel, MD, of the department of medical oncology, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Investigators randomized 101 patients with histologically confirmed ccRCC to receive 8 weeks of pazopanib in a daily dose of 800 mg alternated with 8 weeks of everolimus in a daily dose of 10 mg or 800 mg per day of continuous pazopanib. Patients remained on either regimen until disease progression.

Median time until first progression or death was 7.4 months for the experimental alternating arm versus 9.4 months for the control arm of continuous single-agent pazopanib (P = .37), Dr. Cirkel and associates reported (JAMA Onc. 2017 Apr 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5202).

Progression-free survival after starting on a second-line therapy was 20.2 months for the alternating treatment vs. 14.5 months for the control, but the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference was not significant (P = .86).

There was no apparent toxicity or tolerability advantage from alternating therapy. Nearly 40% of patients in both arms required pazopanib dose reductions, while 14% in the alternating arm also required an everolimus dose reduction. The incidence of serious adverse events possibly related to treatment was comparable between arms.

Quality of life was measured with several tools, including the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Kidney Symptom Index Disease-Related Symptoms (FKSI-DRS), but no significant differences between treatment arms were observed in any measure.

Current guidelines recommend pazopanib, which is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, as a first-line therapy in ccRCC. Everolimus, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, is recommended in the second-line setting. Noting that resistance to pazopanib has been shown to be reversible after a period of withdrawal in experimental studies, the authors had speculated an on-off strategy with everolimus might better preserve the efficacy of pazopanib, providing longer periods of disease control. They had also hypothesized that the cumulative adverse events might be less if the drugs were sequenced, allowing recovery from each set of drug-specific adverse events.

Several potential explanations were offered for the lack of improved efficacy from alternating everolimus with pazopanib. For one, the improved activity of pazopanib after withdrawal in experimental models was observed after drug-free periods. The authors questioned whether a period of tumor regrowth may be needed in order to overcome pazopanib resistance.

The study may still have supported the use of an alternating regimen if the alternating therapy had led to a significantly improved quality of life, but the authors found none, a outcome that they characterized as unexpected. They concluded that there are no apparent advantages for the alternating regimen of pazopanib and everolimus relative to pazopanib alone.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The median time to progression or death was 7.4 months for the combination versus 9.4 months for pazopanib alone (P = .37).

Data source: Randomized, multicenter controlled trial.

Disclosures: The principal investigator Dr. Cirkel reports travel expenses from Novartis, which, along with GlaxoSmithKline, provided funding for this study.