User login

This drug works, but wait till you hear what’s in it

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

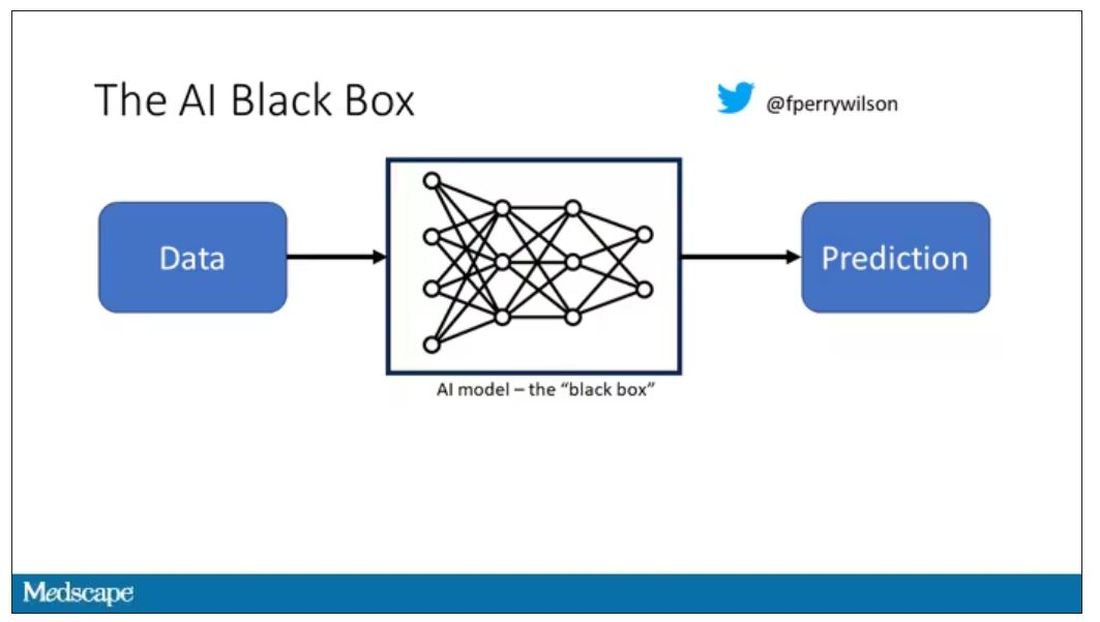

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

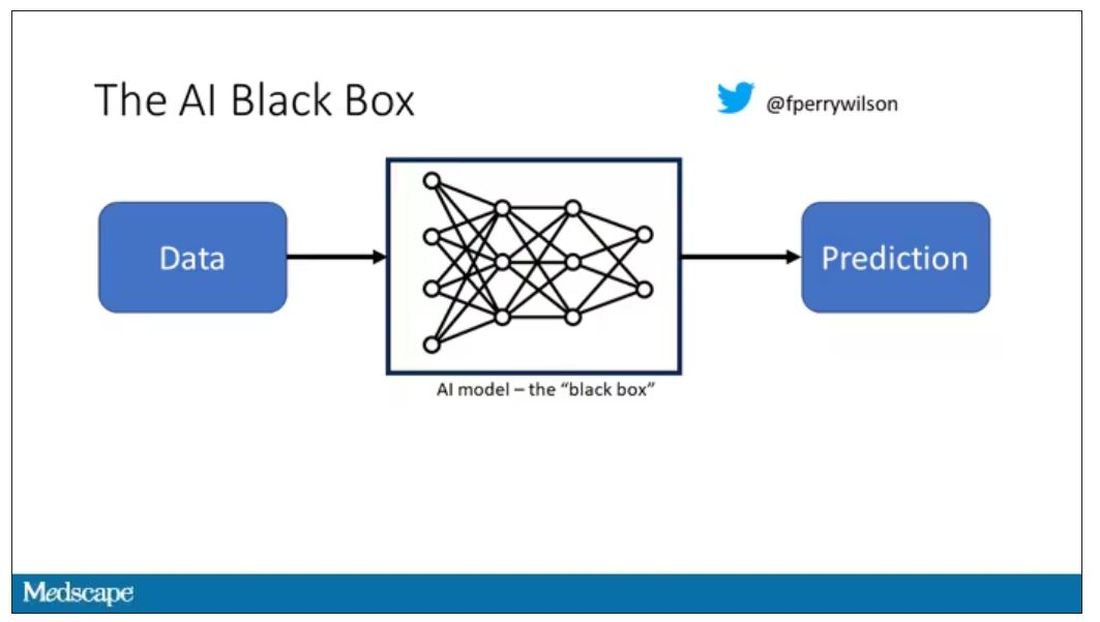

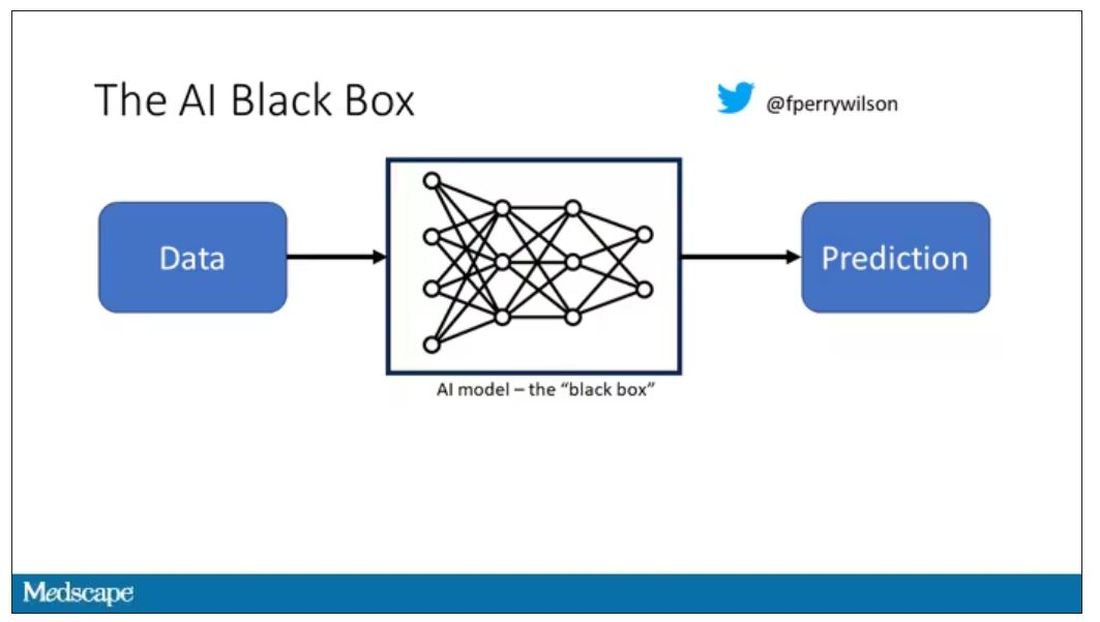

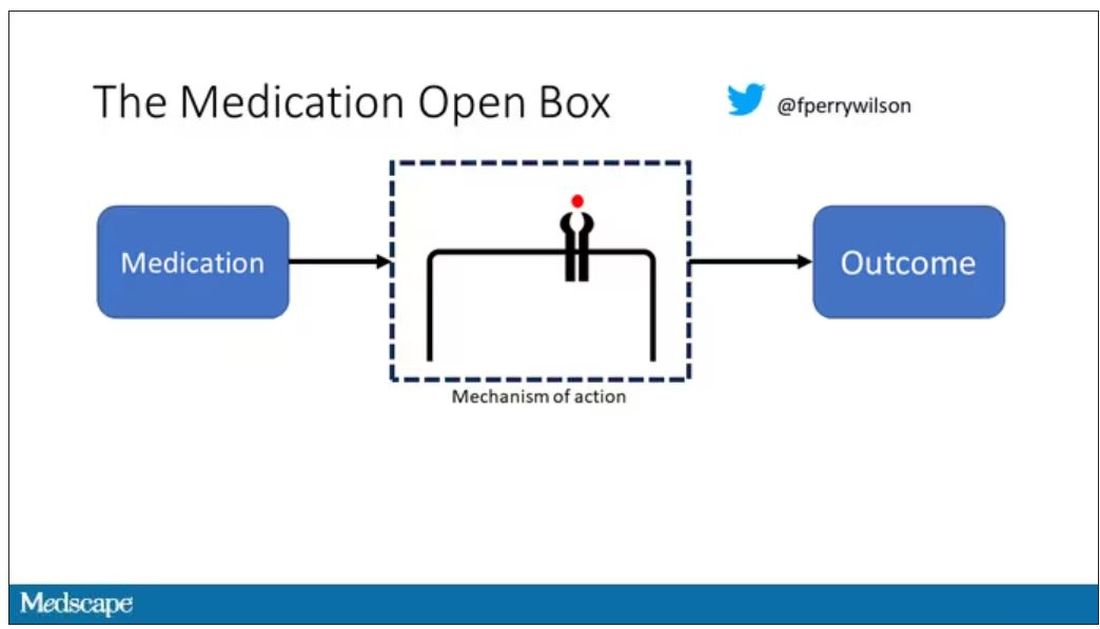

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

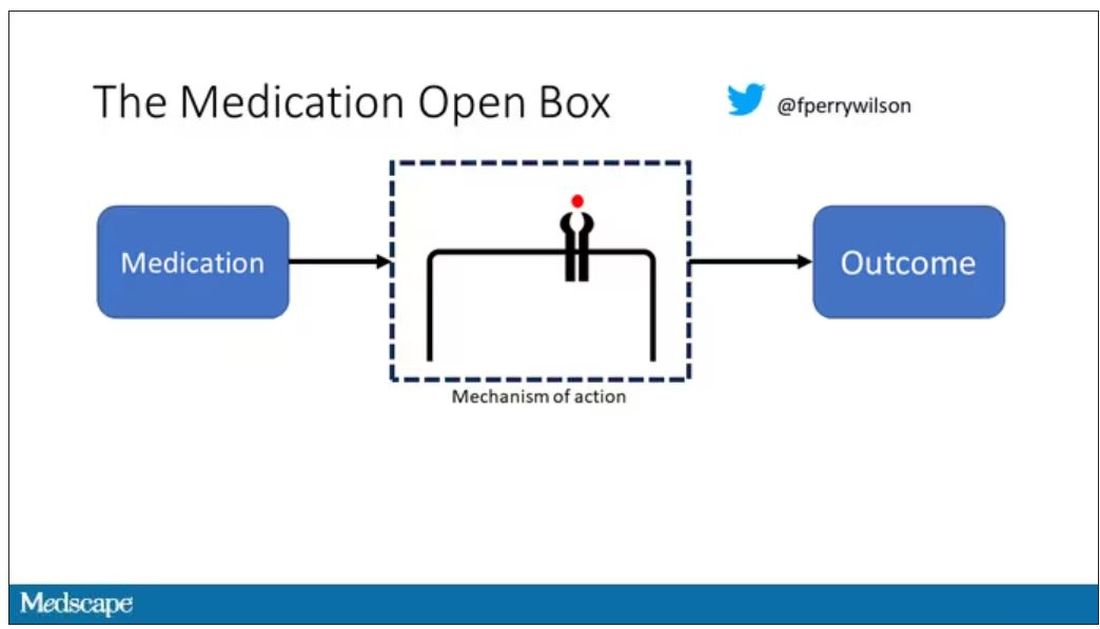

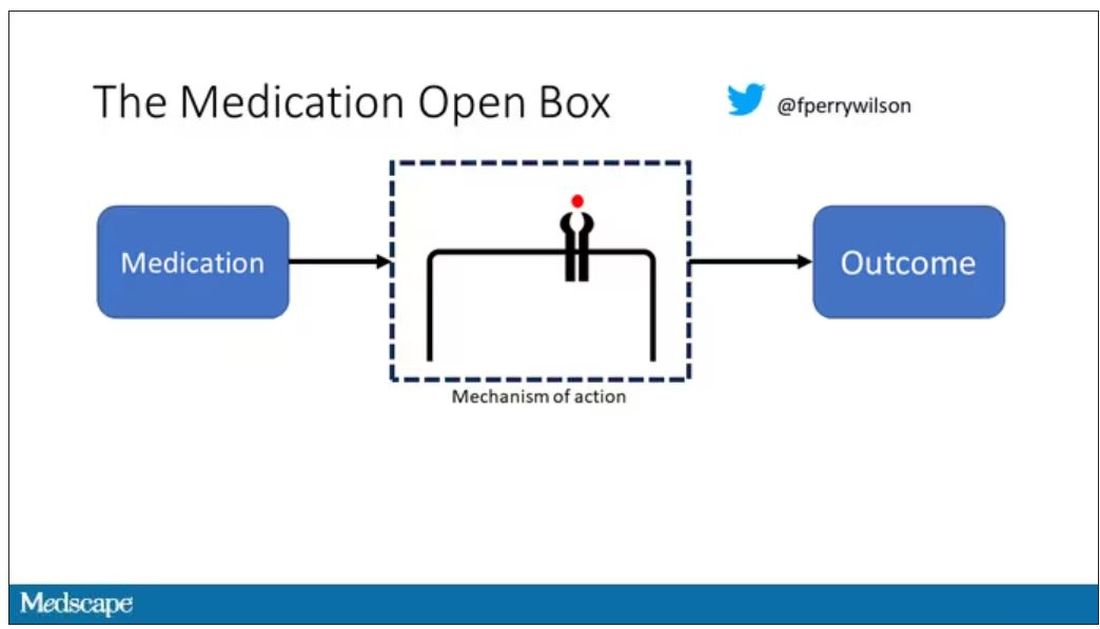

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

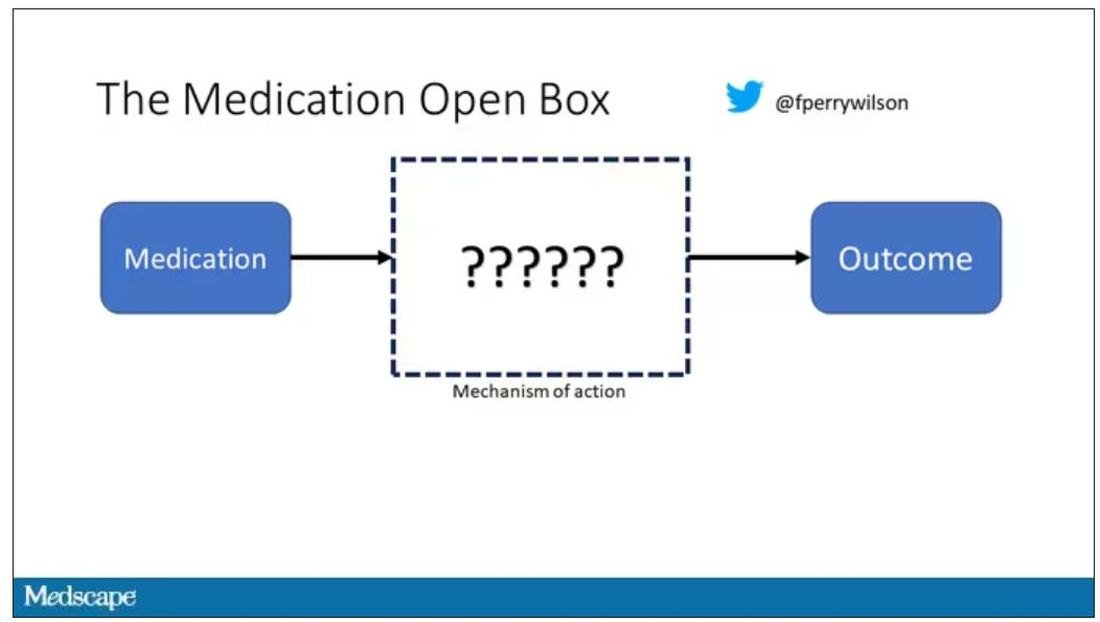

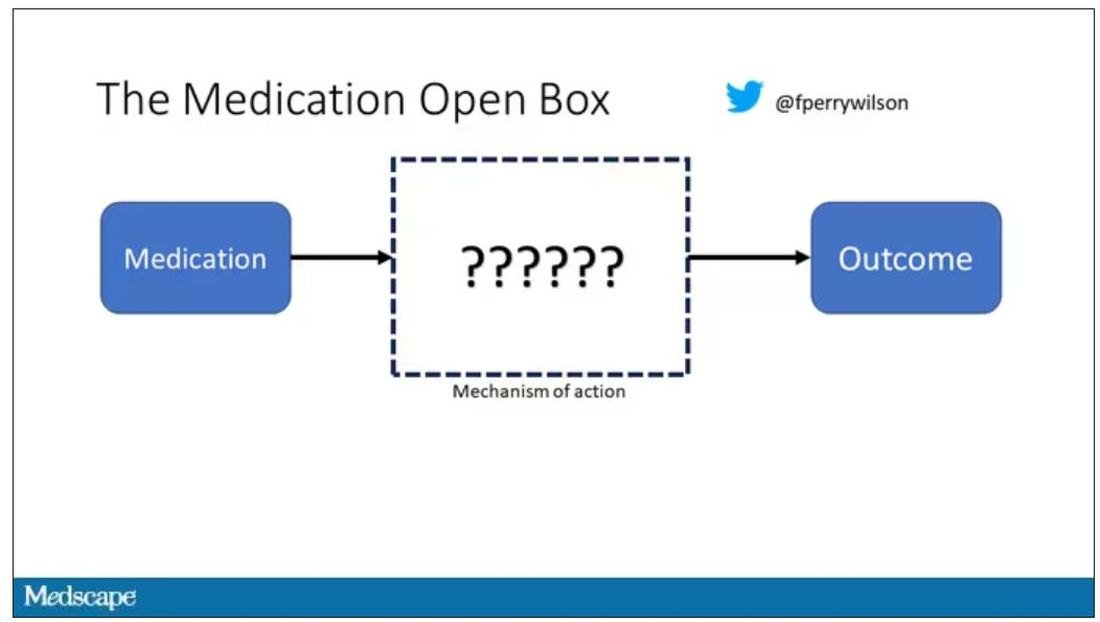

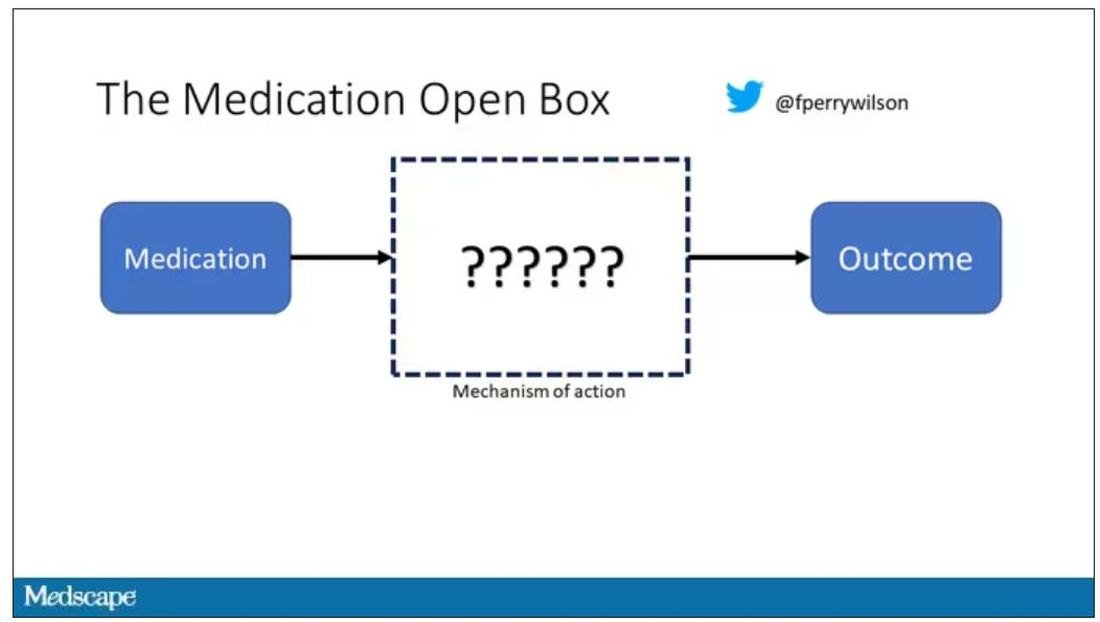

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

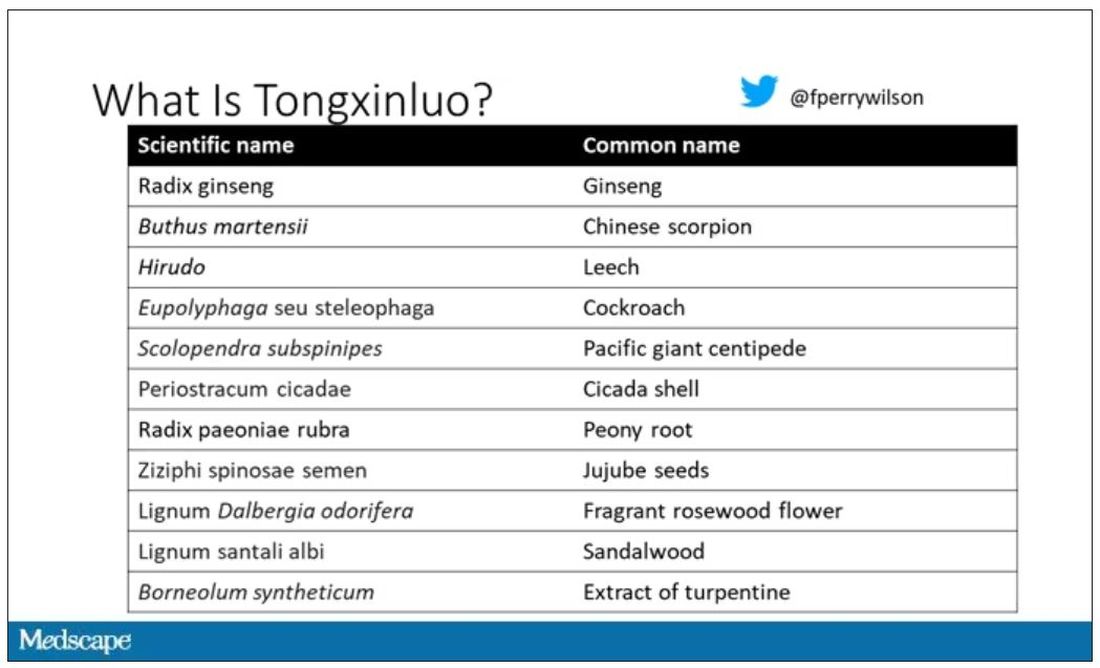

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

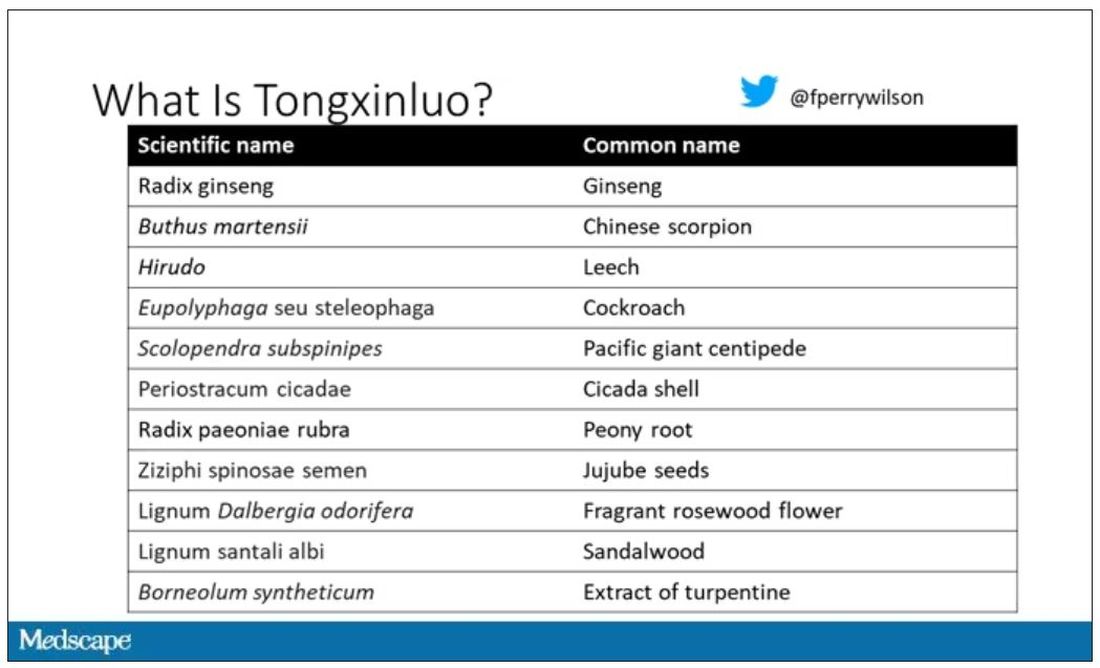

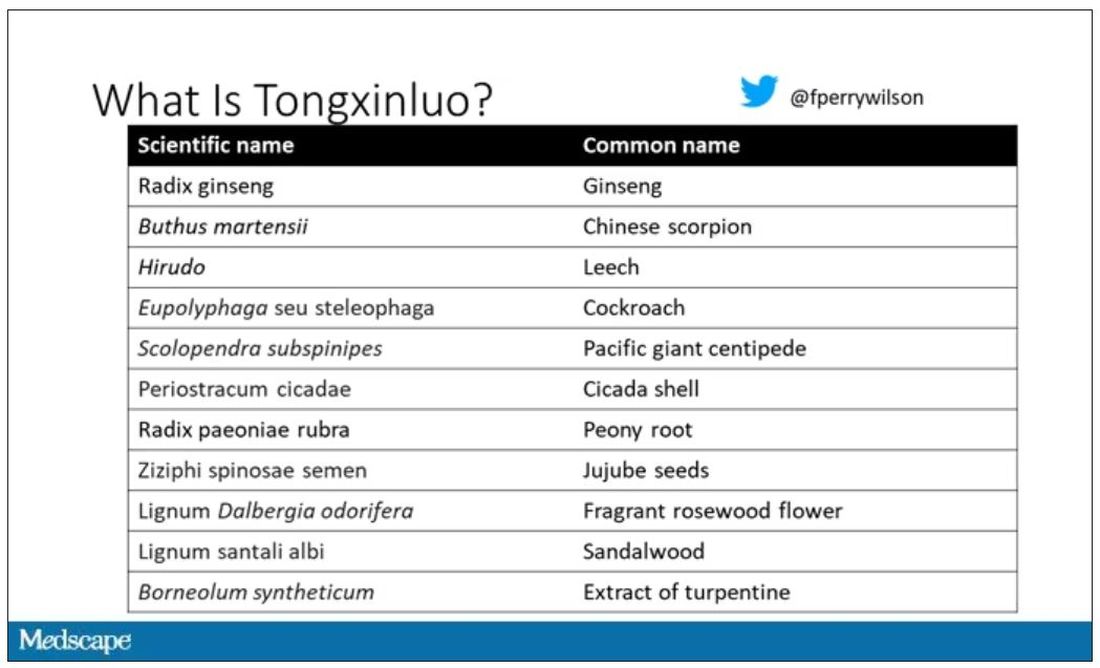

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

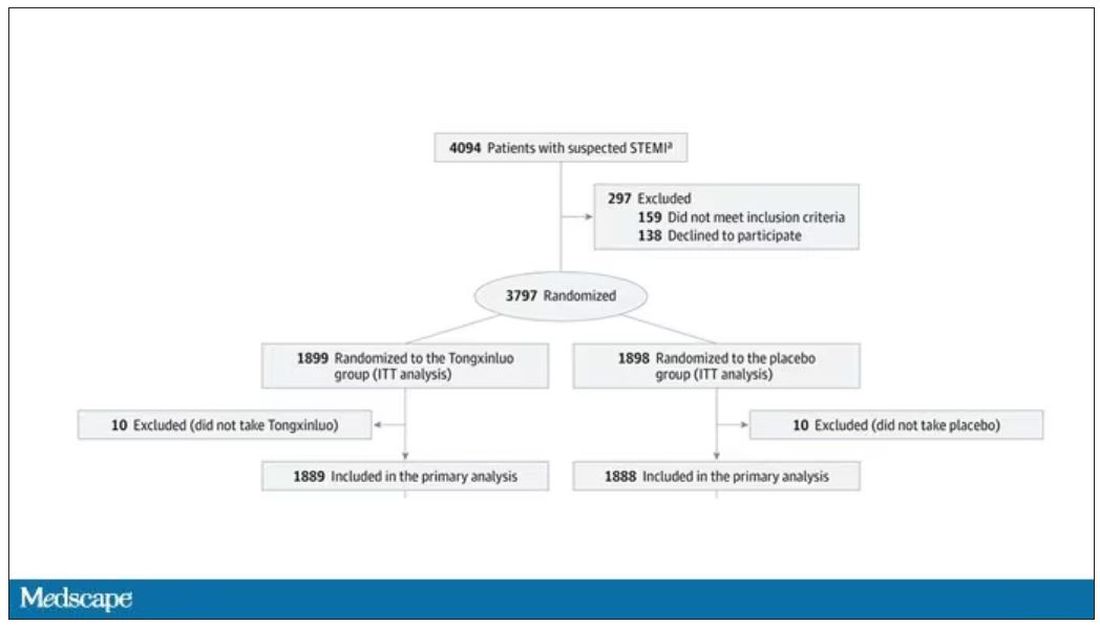

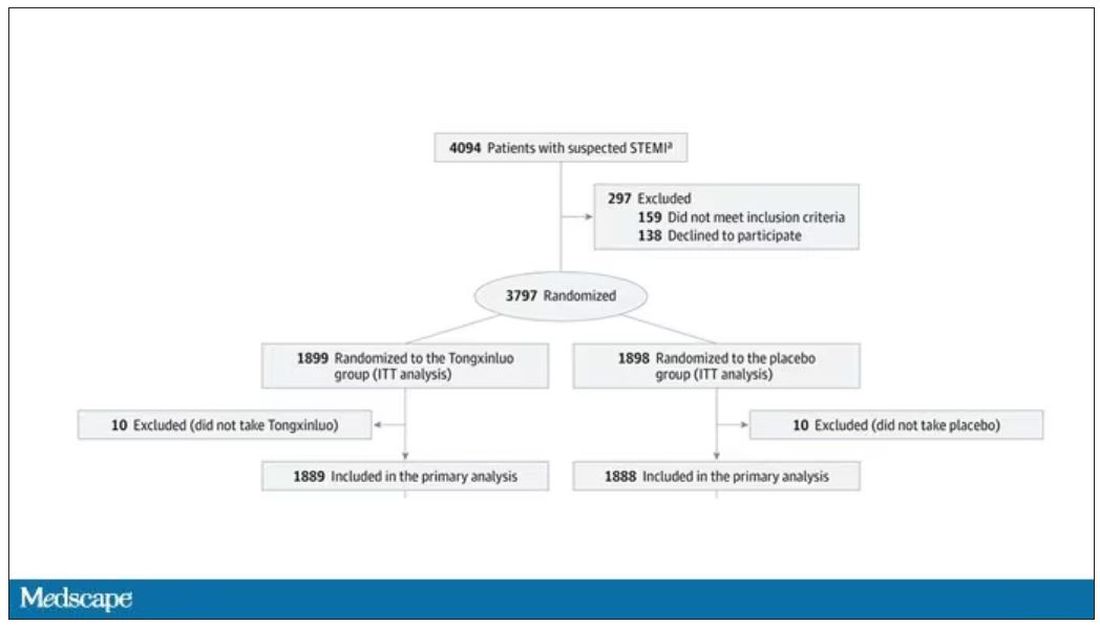

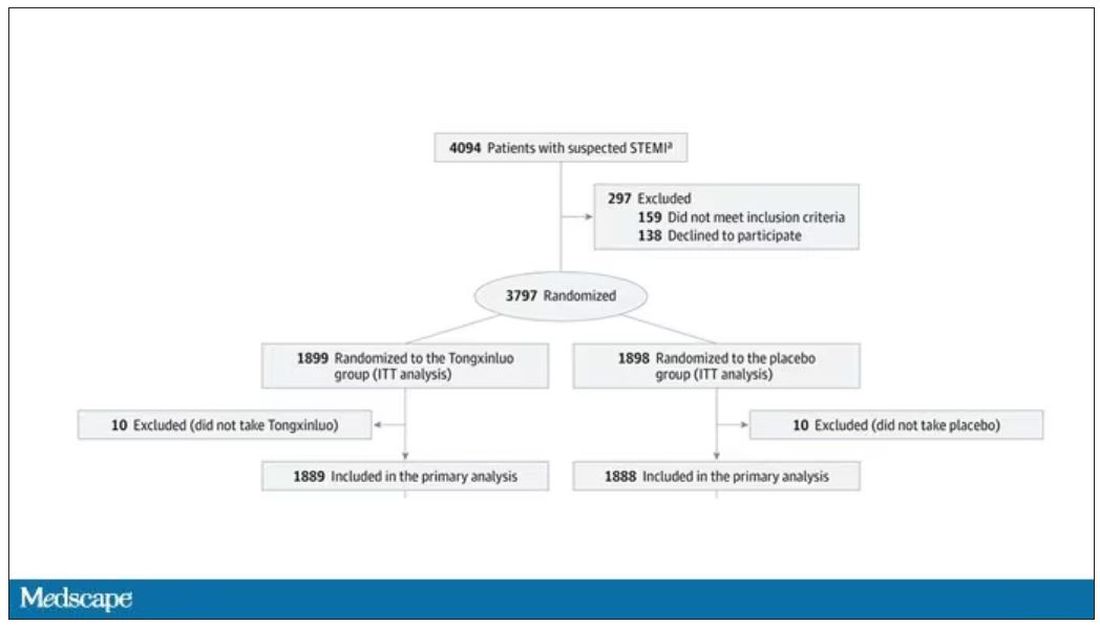

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

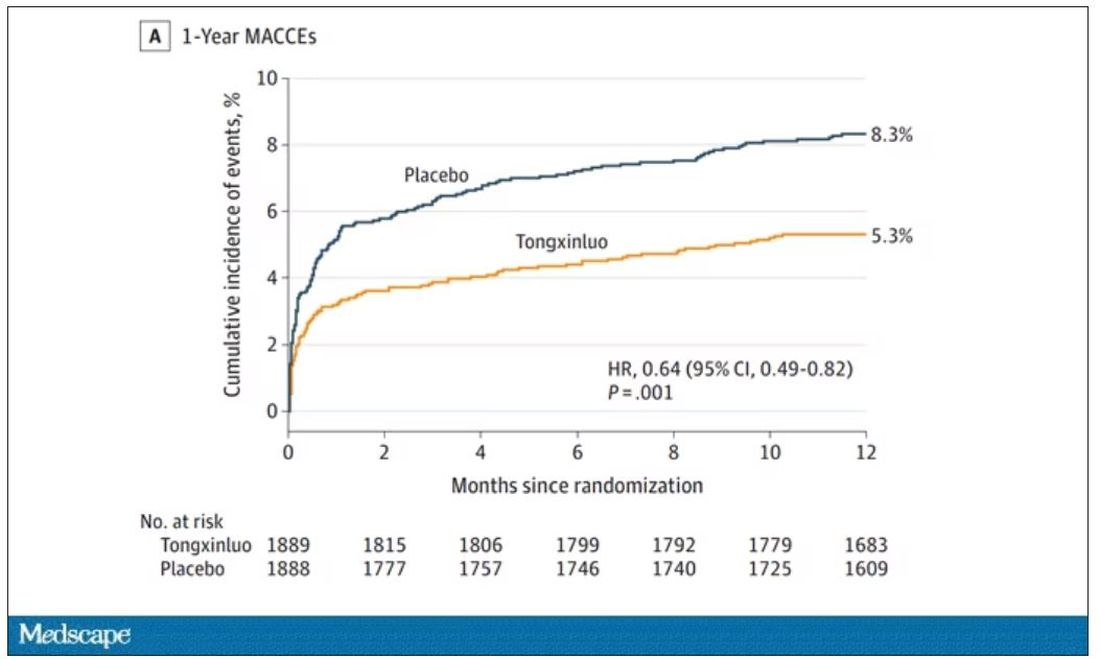

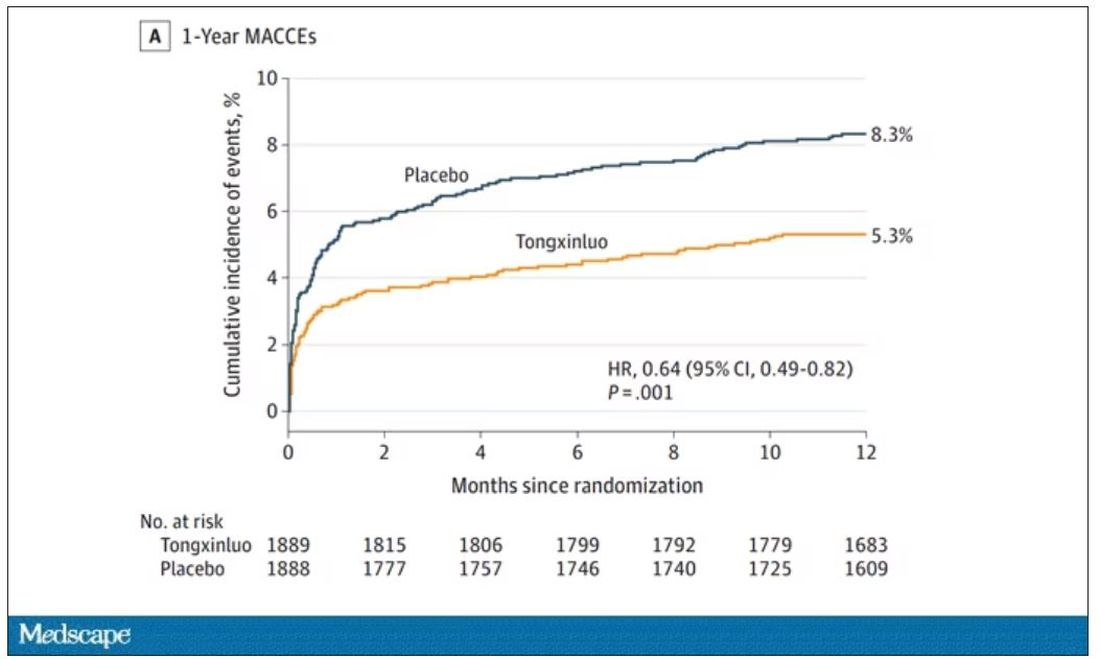

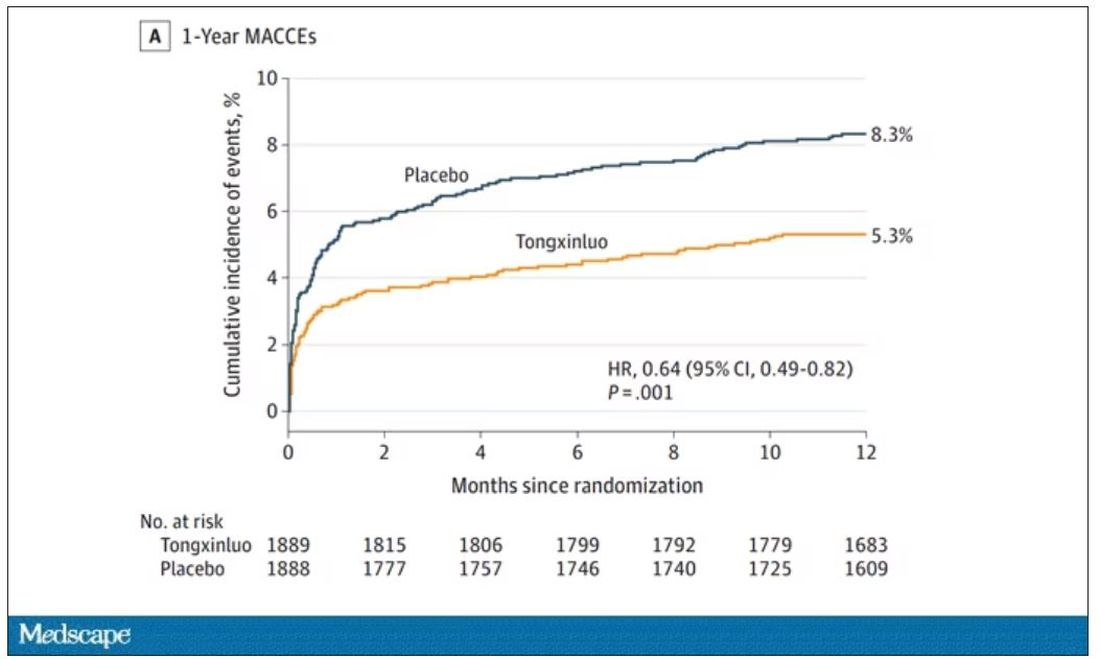

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

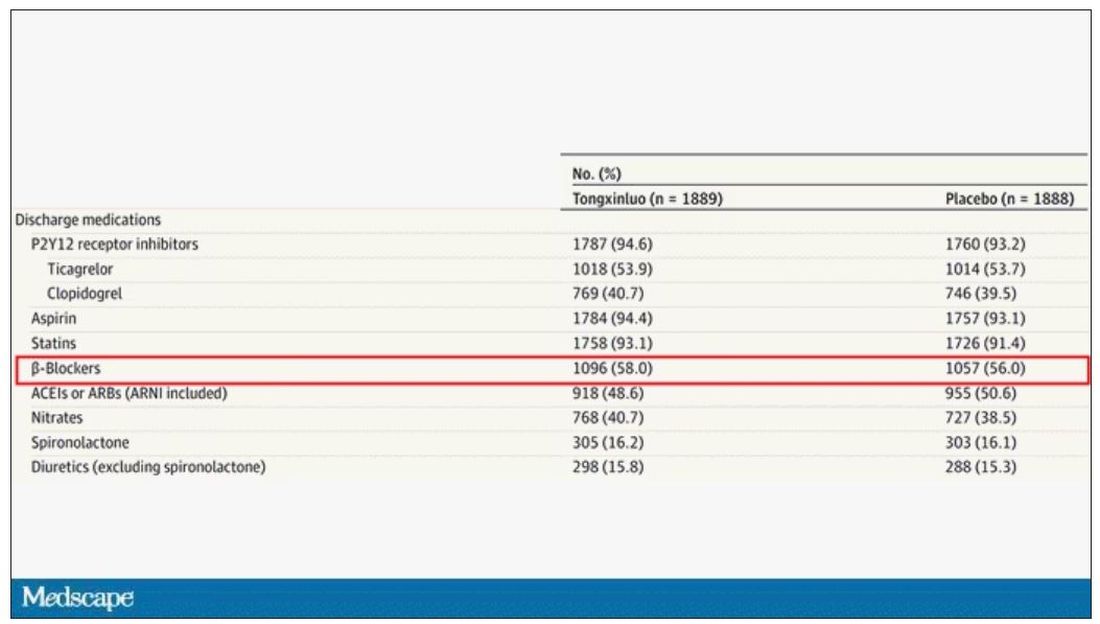

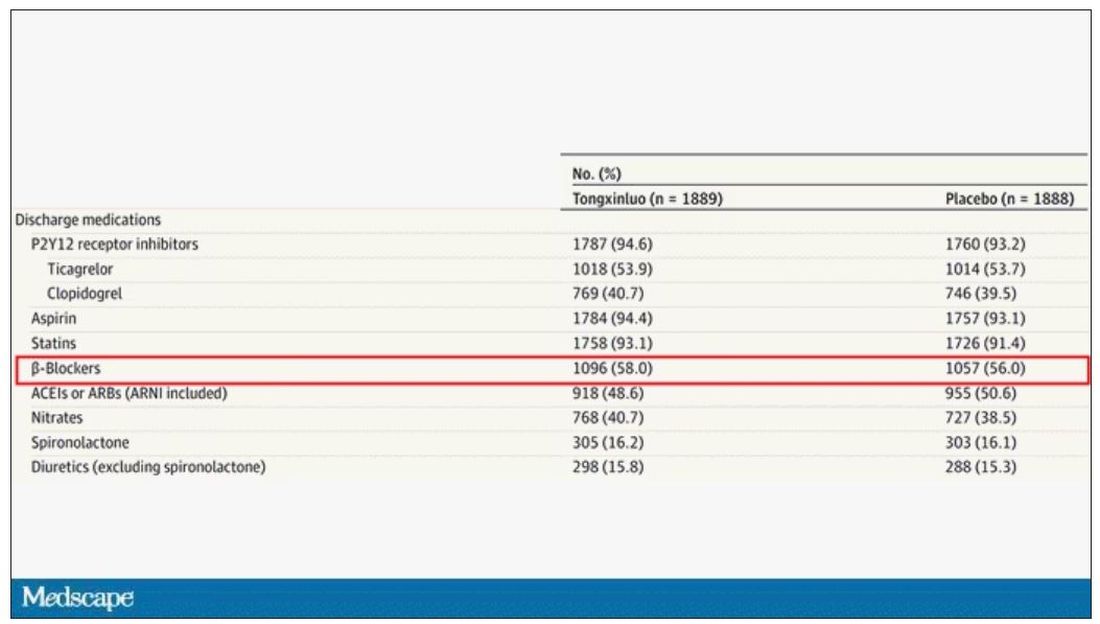

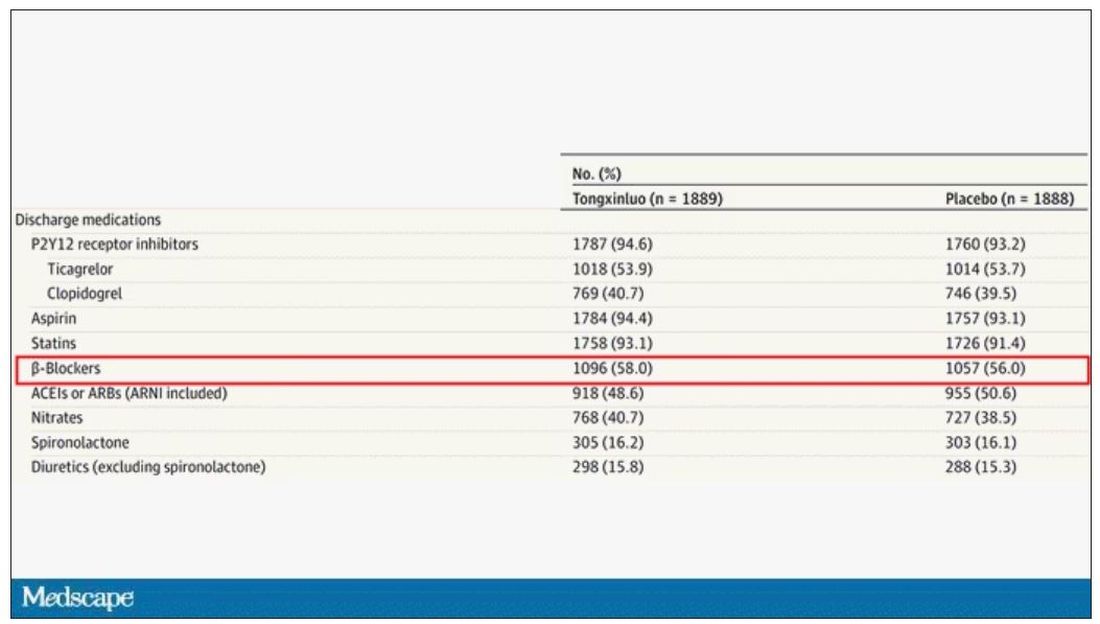

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As some of you may know, I do a fair amount of clinical research developing and evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

A thorny issue that comes up as algorithms have gotten more complicated is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a model that is very accurate at predicting death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain how it makes its predictions – how it works. “It just works” is not good enough to build trust.

It’s easier to build trust when you’re talking about a medication rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure drug comes out that lowers blood pressure, importantly, we know why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action and, for most of the drugs in our arsenal, we know what that mechanism is.

But what if there were a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say we have no idea how it works. That’s what came across my desk today in what I believe is the largest, most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medication in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices that are fundamentally different from how we practice medicine in the West.

It’s a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose what substance to give what patient. That personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine nearly impossible to study in the typical randomized trial framework because treatments are not chosen solely on the basis of disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is rife with practices and beliefs that can legitimately be called pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herb nephropathy,” I can tell you that some of the practices may be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there is nothing there. I do not subscribe to the “argument from antiquity” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non–science-based medicine practices could still identify therapies that work.

And with that, let me introduce you to Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart,” and it is a substance that has been used for centuries by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to treat angina but was approved by the Chinese state medicine agency for use in 1996.

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a single chemical – far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine running a trial of this concoction in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board signing off, given the ingredient list.

But let’s set that aside and talk about the study itself.

While I don’t have access to any primary data, the write-up of the study suggests that it was highly rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look just like the Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to smell like them as well.

Researchers and participants were blinded, and the statistical analysis was done both by the primary team and an independent research agency, also in China.

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, 30-day major cardiovascular and cerebral events, were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

One-year outcomes were similarly good; 8.3% of the placebo group suffered a major cardiovascular or cerebral event in that time frame, compared with 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if this were a pure chemical compound from a major pharmaceutical company, well, you might be seeing a new treatment for heart attack – and a boost in stock price.

But there are some issues here, generalizability being a big one. This study was done entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Moreover, the quality of post-MI care in this study is quite a bit worse than what we’d see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients being discharged on a beta-blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard supplementary treatments are the usual reasons we worry about new medication trials. And those concerns seem to pale before the big one I have here which is, you know – we don’t know why this works.

Is it the extract of leech in the preparation perhaps thinning the blood a bit? Or is it the antioxidants in the ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or the sandalwood?

This trial doesn’t read to me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine but rather as an example of missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries that Tongxinluo has been used could have identified one, or perhaps more, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

Purity of medical substances is incredibly important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact with other treatments we give patients in predictable ways. Pure substances can be quantified for purity by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and they can be assessed for adulteration. In short, pure substances pose less risk.

Now, I know that may come off as particularly sterile. Some people will feel that a “natural” substance has some inherent benefit over pure compounds. And, of course, there is something soothing about imagining a traditional preparation handed down over centuries, being prepared with care by a single practitioner, in contrast to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I get it. But natural is not the same as safe. I am glad I have access to purified aspirin and don’t have to chew willow bark. I like my pure penicillin and am glad I don’t have to make a mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I applaud the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They have generated data that are incredibly exciting, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-elevation MI on our hands; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care is not the mixture that is Tongxinluo, but it might be in the mixture.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available now.

‘Frame running’ may help boost physical activity in MS

MILAN – , a pilot study suggests.

“Frame running” uses a three-wheeled frame with a saddle and body supports but no pedals to allow individuals with disabilities and balance impairments to walk and run under their own power.

Eight individuals with multiple sclerosis and moderate to severe walking impairments took part in a 12-week frame running intervention, which improved both objective physical performance and patient-reported outcomes measures.

“Frame running presents a feasible and enjoyable exercise option for people with multiple sclerosis,” lead author Gary McEwan, PhD, research fellow at the Centre for Health, Activity and Rehabilitation Research at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, and colleagues conclude.

It may, they add, “have potential to improve measures of physical function and the ability to perform mobility-related daily activities.”

The findings were presented at the 9th Joint ECTRIMS-ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dearth of exercise opportunities

The authors note regular physical activity and exercise are “amongst the most important adjunct therapies for managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis,” and yet people with the disease are significantly less physically active than the general population.

This is particularly the case for individuals at the upper end of the disability spectrum, they continue, and may reflect the “relative dearth of exercise opportunities that are suitable for those with more severe mobility impairments.”

In recent years, frame running has emerged as a form of exercise that allows individuals with walking difficulties to engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity in a safe manner, but its feasibility in multiple sclerosis has not been investigated.

The researchers recruited people with multiple sclerosis who had moderate to severe walking impairments to take part in a 12-week frame running intervention, comprising a 1-hour session every week.

The 6-minute frame running test (6MFRT) and an adapted shuttle frame running test (SFRT) were used to assess physical function at baseline and after the intervention. Recruitment, retention, and attendance rates were recorded.

The participants also completed a series of patient-reported outcome measures, alongside the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, to calculate self-perceived abilities in activities of daily living, and semistructured interviews to capture their experiences of the intervention.

The camaraderie of physical activity

With six females and two males enrolled in the study, the team reported that the recruitment rate was 47.1%, the retention rate was 75%, and attendance was 86.7%. No adverse events were reported, they note.

The results indicate there were improvements in performance on the physical measures, with small effect sizes on both the 6MFRT (d = 0.37) and the SFRT (d = 0.30).

There were also improvements on the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (d = 0.27), the Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (d = 0.20), and the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (d = 0.46), again with small effect sizes.

A medium effect size was seen for improvements on the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (d = 0.73), and 80% of the participants reported “changes in performance and in satisfaction with their activities of daily living,” the team says.

The qualitative data also suggested the patients found frame running to be “safe and enjoyable,” with key highlights being the “social aspect and camaraderie developed amongst participants.”

Mix of physical interventions

Approached for comment, Robert Motl, MD, professor of kinesiology and nutrition, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, said it “makes a lot of sense” that frame running can improve walking-related outcomes.

He told this news organization that, “for people who have balance-related problems, using their legs in that rhythmical way could really have some great benefits for walking.”

However, Dr. Motl said he is a “little more skeptical about the benefits for balance, because to improve balance you have to be doing something that challenges upright posture.”

With the frame, “I don’t think you’re having to regulate upright posture while you’re doing that intervention, because you have stability with three points and the ground,” he said. “So, I wonder a little bit about that as an outcome.”

Dr. Motl nevertheless underlined that walking can certainly improve physical activity, “and all the other things like vascular function, cardiovascular fitness,” and so on.

Consequently, frame running “could be part of the mix of things for people who are having a disability, particularly individuals who have some balance dysfunction and [for whom] ambulating might put them at risk of falling.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the Multiple Sclerosis Society UK. The study authors and Dr. Modl report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN – , a pilot study suggests.

“Frame running” uses a three-wheeled frame with a saddle and body supports but no pedals to allow individuals with disabilities and balance impairments to walk and run under their own power.

Eight individuals with multiple sclerosis and moderate to severe walking impairments took part in a 12-week frame running intervention, which improved both objective physical performance and patient-reported outcomes measures.

“Frame running presents a feasible and enjoyable exercise option for people with multiple sclerosis,” lead author Gary McEwan, PhD, research fellow at the Centre for Health, Activity and Rehabilitation Research at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, and colleagues conclude.

It may, they add, “have potential to improve measures of physical function and the ability to perform mobility-related daily activities.”

The findings were presented at the 9th Joint ECTRIMS-ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dearth of exercise opportunities

The authors note regular physical activity and exercise are “amongst the most important adjunct therapies for managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis,” and yet people with the disease are significantly less physically active than the general population.

This is particularly the case for individuals at the upper end of the disability spectrum, they continue, and may reflect the “relative dearth of exercise opportunities that are suitable for those with more severe mobility impairments.”

In recent years, frame running has emerged as a form of exercise that allows individuals with walking difficulties to engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity in a safe manner, but its feasibility in multiple sclerosis has not been investigated.

The researchers recruited people with multiple sclerosis who had moderate to severe walking impairments to take part in a 12-week frame running intervention, comprising a 1-hour session every week.

The 6-minute frame running test (6MFRT) and an adapted shuttle frame running test (SFRT) were used to assess physical function at baseline and after the intervention. Recruitment, retention, and attendance rates were recorded.

The participants also completed a series of patient-reported outcome measures, alongside the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, to calculate self-perceived abilities in activities of daily living, and semistructured interviews to capture their experiences of the intervention.

The camaraderie of physical activity

With six females and two males enrolled in the study, the team reported that the recruitment rate was 47.1%, the retention rate was 75%, and attendance was 86.7%. No adverse events were reported, they note.

The results indicate there were improvements in performance on the physical measures, with small effect sizes on both the 6MFRT (d = 0.37) and the SFRT (d = 0.30).

There were also improvements on the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (d = 0.27), the Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (d = 0.20), and the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (d = 0.46), again with small effect sizes.

A medium effect size was seen for improvements on the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (d = 0.73), and 80% of the participants reported “changes in performance and in satisfaction with their activities of daily living,” the team says.

The qualitative data also suggested the patients found frame running to be “safe and enjoyable,” with key highlights being the “social aspect and camaraderie developed amongst participants.”

Mix of physical interventions

Approached for comment, Robert Motl, MD, professor of kinesiology and nutrition, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, said it “makes a lot of sense” that frame running can improve walking-related outcomes.

He told this news organization that, “for people who have balance-related problems, using their legs in that rhythmical way could really have some great benefits for walking.”

However, Dr. Motl said he is a “little more skeptical about the benefits for balance, because to improve balance you have to be doing something that challenges upright posture.”

With the frame, “I don’t think you’re having to regulate upright posture while you’re doing that intervention, because you have stability with three points and the ground,” he said. “So, I wonder a little bit about that as an outcome.”

Dr. Motl nevertheless underlined that walking can certainly improve physical activity, “and all the other things like vascular function, cardiovascular fitness,” and so on.

Consequently, frame running “could be part of the mix of things for people who are having a disability, particularly individuals who have some balance dysfunction and [for whom] ambulating might put them at risk of falling.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the Multiple Sclerosis Society UK. The study authors and Dr. Modl report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN – , a pilot study suggests.

“Frame running” uses a three-wheeled frame with a saddle and body supports but no pedals to allow individuals with disabilities and balance impairments to walk and run under their own power.

Eight individuals with multiple sclerosis and moderate to severe walking impairments took part in a 12-week frame running intervention, which improved both objective physical performance and patient-reported outcomes measures.

“Frame running presents a feasible and enjoyable exercise option for people with multiple sclerosis,” lead author Gary McEwan, PhD, research fellow at the Centre for Health, Activity and Rehabilitation Research at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, and colleagues conclude.

It may, they add, “have potential to improve measures of physical function and the ability to perform mobility-related daily activities.”

The findings were presented at the 9th Joint ECTRIMS-ACTRIMS Meeting.

Dearth of exercise opportunities

The authors note regular physical activity and exercise are “amongst the most important adjunct therapies for managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis,” and yet people with the disease are significantly less physically active than the general population.

This is particularly the case for individuals at the upper end of the disability spectrum, they continue, and may reflect the “relative dearth of exercise opportunities that are suitable for those with more severe mobility impairments.”

In recent years, frame running has emerged as a form of exercise that allows individuals with walking difficulties to engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity in a safe manner, but its feasibility in multiple sclerosis has not been investigated.

The researchers recruited people with multiple sclerosis who had moderate to severe walking impairments to take part in a 12-week frame running intervention, comprising a 1-hour session every week.

The 6-minute frame running test (6MFRT) and an adapted shuttle frame running test (SFRT) were used to assess physical function at baseline and after the intervention. Recruitment, retention, and attendance rates were recorded.

The participants also completed a series of patient-reported outcome measures, alongside the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, to calculate self-perceived abilities in activities of daily living, and semistructured interviews to capture their experiences of the intervention.

The camaraderie of physical activity

With six females and two males enrolled in the study, the team reported that the recruitment rate was 47.1%, the retention rate was 75%, and attendance was 86.7%. No adverse events were reported, they note.

The results indicate there were improvements in performance on the physical measures, with small effect sizes on both the 6MFRT (d = 0.37) and the SFRT (d = 0.30).

There were also improvements on the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (d = 0.27), the Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (d = 0.20), and the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (d = 0.46), again with small effect sizes.

A medium effect size was seen for improvements on the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (d = 0.73), and 80% of the participants reported “changes in performance and in satisfaction with their activities of daily living,” the team says.

The qualitative data also suggested the patients found frame running to be “safe and enjoyable,” with key highlights being the “social aspect and camaraderie developed amongst participants.”

Mix of physical interventions

Approached for comment, Robert Motl, MD, professor of kinesiology and nutrition, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, said it “makes a lot of sense” that frame running can improve walking-related outcomes.

He told this news organization that, “for people who have balance-related problems, using their legs in that rhythmical way could really have some great benefits for walking.”

However, Dr. Motl said he is a “little more skeptical about the benefits for balance, because to improve balance you have to be doing something that challenges upright posture.”

With the frame, “I don’t think you’re having to regulate upright posture while you’re doing that intervention, because you have stability with three points and the ground,” he said. “So, I wonder a little bit about that as an outcome.”

Dr. Motl nevertheless underlined that walking can certainly improve physical activity, “and all the other things like vascular function, cardiovascular fitness,” and so on.

Consequently, frame running “could be part of the mix of things for people who are having a disability, particularly individuals who have some balance dysfunction and [for whom] ambulating might put them at risk of falling.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the Multiple Sclerosis Society UK. The study authors and Dr. Modl report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECTRIMS 2023

Hitting the snooze button may provide cognitive benefit

TOPLINE:

Challenging conventional wisdom,

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did two studies to determine why intermittent morning alarms are used and how they affect sleep, cognition, cortisol, and mood.

- Study 1 was a survey of 1,732 healthy adults (mean age 34 years; 66% women) designed to elucidate the characteristics of people who snooze and why they choose to delay their waking in this way.

- Study 2 was a within-subject polysomnography study of 31 healthy habitual snoozers (mean age 27 years; 18 women) designed to explore the acute effects of snoozing on sleep architecture, sleepiness, cognitive ability, mood, and cortisol awakening response.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 69% reported using the snooze button or setting multiple alarms at least sometimes, most often on workdays (71%), with an average snooze time per morning of 22 minutes.

- Sleep quality did not differ between snoozers and nonsnoozers, but snoozers were more likely to feel mentally drowsy on waking (odds ratio, 3.0; P < .001) and had slightly shorter sleep time on workdays (13 minutes).

- In the polysomnography study, compared with waking up abruptly, 30 minutes of snoozing in the morning improved or did not affect performance on standard cognitive tests completed directly on final awakening.

- Snoozing resulted in about 6 minutes of lost sleep, but it prevented awakening from slow-wave sleep and had no clear effects on the cortisol awakening response, morning sleepiness, mood, or overnight sleep architecture.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that there is no reason to stop snoozing in the morning if you enjoy it, at least not for snooze times around 30 minutes. In fact, it may even help those with morning drowsiness to be slightly more awake once they get up,” corresponding author Tina Sundelin, PhD, of Stockholm University, said in a statement.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study 1 focused on waking preferences in a convenience sample of adults. Study 2 included only habitual snoozers making it difficult to generalize the findings to people who don’t usually snooze. The study investigated only the effect of 30 minutes of snoozing on the studied parameters. It’s possible that shorter or longer snooze times have different cognitive effects.

DISCLOSURES:

Support for the study was provided by the Stress Research Institute, Stockholm University, and a grant from Vetenskapsrådet. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Challenging conventional wisdom,

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did two studies to determine why intermittent morning alarms are used and how they affect sleep, cognition, cortisol, and mood.

- Study 1 was a survey of 1,732 healthy adults (mean age 34 years; 66% women) designed to elucidate the characteristics of people who snooze and why they choose to delay their waking in this way.

- Study 2 was a within-subject polysomnography study of 31 healthy habitual snoozers (mean age 27 years; 18 women) designed to explore the acute effects of snoozing on sleep architecture, sleepiness, cognitive ability, mood, and cortisol awakening response.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 69% reported using the snooze button or setting multiple alarms at least sometimes, most often on workdays (71%), with an average snooze time per morning of 22 minutes.

- Sleep quality did not differ between snoozers and nonsnoozers, but snoozers were more likely to feel mentally drowsy on waking (odds ratio, 3.0; P < .001) and had slightly shorter sleep time on workdays (13 minutes).

- In the polysomnography study, compared with waking up abruptly, 30 minutes of snoozing in the morning improved or did not affect performance on standard cognitive tests completed directly on final awakening.

- Snoozing resulted in about 6 minutes of lost sleep, but it prevented awakening from slow-wave sleep and had no clear effects on the cortisol awakening response, morning sleepiness, mood, or overnight sleep architecture.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that there is no reason to stop snoozing in the morning if you enjoy it, at least not for snooze times around 30 minutes. In fact, it may even help those with morning drowsiness to be slightly more awake once they get up,” corresponding author Tina Sundelin, PhD, of Stockholm University, said in a statement.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study 1 focused on waking preferences in a convenience sample of adults. Study 2 included only habitual snoozers making it difficult to generalize the findings to people who don’t usually snooze. The study investigated only the effect of 30 minutes of snoozing on the studied parameters. It’s possible that shorter or longer snooze times have different cognitive effects.

DISCLOSURES:

Support for the study was provided by the Stress Research Institute, Stockholm University, and a grant from Vetenskapsrådet. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Challenging conventional wisdom,

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers did two studies to determine why intermittent morning alarms are used and how they affect sleep, cognition, cortisol, and mood.

- Study 1 was a survey of 1,732 healthy adults (mean age 34 years; 66% women) designed to elucidate the characteristics of people who snooze and why they choose to delay their waking in this way.

- Study 2 was a within-subject polysomnography study of 31 healthy habitual snoozers (mean age 27 years; 18 women) designed to explore the acute effects of snoozing on sleep architecture, sleepiness, cognitive ability, mood, and cortisol awakening response.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 69% reported using the snooze button or setting multiple alarms at least sometimes, most often on workdays (71%), with an average snooze time per morning of 22 minutes.

- Sleep quality did not differ between snoozers and nonsnoozers, but snoozers were more likely to feel mentally drowsy on waking (odds ratio, 3.0; P < .001) and had slightly shorter sleep time on workdays (13 minutes).

- In the polysomnography study, compared with waking up abruptly, 30 minutes of snoozing in the morning improved or did not affect performance on standard cognitive tests completed directly on final awakening.

- Snoozing resulted in about 6 minutes of lost sleep, but it prevented awakening from slow-wave sleep and had no clear effects on the cortisol awakening response, morning sleepiness, mood, or overnight sleep architecture.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that there is no reason to stop snoozing in the morning if you enjoy it, at least not for snooze times around 30 minutes. In fact, it may even help those with morning drowsiness to be slightly more awake once they get up,” corresponding author Tina Sundelin, PhD, of Stockholm University, said in a statement.

SOURCE:

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study 1 focused on waking preferences in a convenience sample of adults. Study 2 included only habitual snoozers making it difficult to generalize the findings to people who don’t usually snooze. The study investigated only the effect of 30 minutes of snoozing on the studied parameters. It’s possible that shorter or longer snooze times have different cognitive effects.

DISCLOSURES:

Support for the study was provided by the Stress Research Institute, Stockholm University, and a grant from Vetenskapsrådet. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physical activity in children tied to increased brain volume

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators used data on 1,088 children (52% girls) in the Generation R Study, a 4-year longitudinal population-based cohort study in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- At age 10 years, children and their caregivers reported on children’s level of physical activity and sports involvement.

- Investigators measured changes in participants’ brain volume via MRI at ages 10 and 14 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Every 1 additional hour per week in sports participation was associated with a 64.0-mm3 larger volume change in subcortical gray matter (P = .04).

- Every 1 additional hour per week in total physical activity was associated with a 154.0-mm3 larger volume change in total white matter (P = .02).

- Total physical activity reported by any source (P = .03) and child reports of outdoor play (P = .01) were associated with increased amygdala volume over time.

- Total physical activity reported by the children was associated with hippocampal volume increases (P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

“Physical activity is one of the most promising environmental exposures favorably influencing health across the lifespan,” the authors write. “This study adds to prior literature by highlighting the neurodevelopmental benefits physical activity may have on the architecture of the amygdala and hippocampus.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fernando Estévez-López, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, the SPORT Research Group and CERNEP Research Center at the University of Almería (Spain), and Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It was published online on in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study only accounted for confounders at baseline, does not establish causation, and utilized unvalidated questionnaires to gather information on physical activity.

DISCLOSURES:

Individual authors report receiving financial support, but there was no specific funding for this study. Dr. Estévez-López reports no relevant financial conflicts. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators used data on 1,088 children (52% girls) in the Generation R Study, a 4-year longitudinal population-based cohort study in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- At age 10 years, children and their caregivers reported on children’s level of physical activity and sports involvement.

- Investigators measured changes in participants’ brain volume via MRI at ages 10 and 14 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Every 1 additional hour per week in sports participation was associated with a 64.0-mm3 larger volume change in subcortical gray matter (P = .04).

- Every 1 additional hour per week in total physical activity was associated with a 154.0-mm3 larger volume change in total white matter (P = .02).

- Total physical activity reported by any source (P = .03) and child reports of outdoor play (P = .01) were associated with increased amygdala volume over time.

- Total physical activity reported by the children was associated with hippocampal volume increases (P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

“Physical activity is one of the most promising environmental exposures favorably influencing health across the lifespan,” the authors write. “This study adds to prior literature by highlighting the neurodevelopmental benefits physical activity may have on the architecture of the amygdala and hippocampus.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fernando Estévez-López, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, the SPORT Research Group and CERNEP Research Center at the University of Almería (Spain), and Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It was published online on in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study only accounted for confounders at baseline, does not establish causation, and utilized unvalidated questionnaires to gather information on physical activity.

DISCLOSURES:

Individual authors report receiving financial support, but there was no specific funding for this study. Dr. Estévez-López reports no relevant financial conflicts. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators used data on 1,088 children (52% girls) in the Generation R Study, a 4-year longitudinal population-based cohort study in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- At age 10 years, children and their caregivers reported on children’s level of physical activity and sports involvement.

- Investigators measured changes in participants’ brain volume via MRI at ages 10 and 14 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Every 1 additional hour per week in sports participation was associated with a 64.0-mm3 larger volume change in subcortical gray matter (P = .04).

- Every 1 additional hour per week in total physical activity was associated with a 154.0-mm3 larger volume change in total white matter (P = .02).

- Total physical activity reported by any source (P = .03) and child reports of outdoor play (P = .01) were associated with increased amygdala volume over time.

- Total physical activity reported by the children was associated with hippocampal volume increases (P = .02).

IN PRACTICE:

“Physical activity is one of the most promising environmental exposures favorably influencing health across the lifespan,” the authors write. “This study adds to prior literature by highlighting the neurodevelopmental benefits physical activity may have on the architecture of the amygdala and hippocampus.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fernando Estévez-López, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, the SPORT Research Group and CERNEP Research Center at the University of Almería (Spain), and Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It was published online on in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study only accounted for confounders at baseline, does not establish causation, and utilized unvalidated questionnaires to gather information on physical activity.

DISCLOSURES:

Individual authors report receiving financial support, but there was no specific funding for this study. Dr. Estévez-López reports no relevant financial conflicts. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Postmenopausal stress linked to mood, cognitive symptoms

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

“This work suggests that markers of hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activation that capture total cortisol secretion over multiple months, [such as] hair cortisol, strongly correlate with cognitive performance on attention and working memory tasks, whereas measures of more acute cortisol, [such as] salivary cortisol, may be more strongly associated with depression symptom severity and verbal learning,” Christina Metcalf, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry in the Colorado Center for Women’s Behavioral Health and Wellness at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, told attendees. “Given the associations with chronic stress, there’s a lot of potential here to increase our knowledge about how women are doing and managing stress and life stressors during this life transition,” she said.

The study involved collecting hair and saliva samples from 43 healthy women in late perimenopause or early postmenopause with an average age of 51. The participants were predominantly white and college educated. The hair sample was taken within 2 cm of the scalp, and the saliva samples were collected the day after the hair sample collection, at the start and end of a 30-minute rest period that took place between 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. local time.

All the participants had an intact uterus and at least one ovary. None of the participants were current smokers or had recent alcohol or drug dependence, and none had used hormones within the previous 6 months. The study also excluded women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, who had bleached hair or no hair, who were taking steroids, beta blockers or opioid medication, and who had recently taken NSAIDS.

Measuring hair cortisol more feasible

The study was conducted remotely, with participants using video conferencing to communicate with the study personnel and then completing study procedures at home, including 2 days of cognitive testing with the California Verbal Learning Test – Third Edition and the n-back and continuous performance tasks. The participants also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

Participants with higher levels of hair cortisol and salivary cortisol also had more severe depression symptoms (P < .001). Hair cortisol was also significantly associated with attention and working memory: Women with higher levels had fewer correct answers on the 0-back and 1-back trials (P < .01) and made more mistakes on the 2-back trial (P < .001). They also scored with less specificity on the continuous performance tasks (P = .022).

Although no association existed between hair cortisol levels and verbal learning or verbal memory (P > .05), participants with higher hair cortisol did score worse on the immediate recall trials (P = .034). Salivary cortisol levels, on the other hand, showed no association with memory recall trials, attention or working memory (P > .05).

Measuring cortisol from hair samples is more feasible than using saliva samples and may offer valuable insights regarding hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activity “to consider alongside the cognitive and mental health of late peri-/early postmenopausal women,” Dr. Metcalf told attendees. The next step is to find out whether the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis axis is a modifiable biomarker that can be used to improve executive function.

The study was limited by its small population, its cross-sectional design, and the lack of covariates in the current analyses.

Monitor symptoms in midlife

Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc, a professor of psychiatry and executive director of the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study findings were not surprising given how common the complaints of stress and depressive symptoms are.

“Mood changes are linked with acute, immediate cortisol levels at the same point in time, and cognitive symptoms were linked to more chronically elevated cortisol levels,” Dr. Joffe said in an interview. “Women and their providers should monitor for these challenging brain symptoms in midlife as they affect performance and quality of life and are linked with changes in the HPA axis as stress biomarkers.”

Because the study is small and has a cross-sectional design, it’s not possible to determine the direction of the associations or to make any inferences about causation, Dr. Joffe said.

“We cannot make the conclusion that stress is adversely affecting mood and cognitive performance given the design limitations. It is possible that mood and cognitive issues contributed to these stress markers,” Dr. Joffe said.“However, it is known that the experience of stress is linked with vulnerability to mood and cognitive symptoms, and also that mood and cognitive symptoms induce significant stress.”

The research was funded by the Menopause Society, Colorado University, the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Metcalf had no disclosures. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck, Pfizer and Sage, and has been a consultant or advisor for Bayer, Merck and Hello Therapeutics.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

“This work suggests that markers of hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activation that capture total cortisol secretion over multiple months, [such as] hair cortisol, strongly correlate with cognitive performance on attention and working memory tasks, whereas measures of more acute cortisol, [such as] salivary cortisol, may be more strongly associated with depression symptom severity and verbal learning,” Christina Metcalf, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry in the Colorado Center for Women’s Behavioral Health and Wellness at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, told attendees. “Given the associations with chronic stress, there’s a lot of potential here to increase our knowledge about how women are doing and managing stress and life stressors during this life transition,” she said.

The study involved collecting hair and saliva samples from 43 healthy women in late perimenopause or early postmenopause with an average age of 51. The participants were predominantly white and college educated. The hair sample was taken within 2 cm of the scalp, and the saliva samples were collected the day after the hair sample collection, at the start and end of a 30-minute rest period that took place between 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. local time.

All the participants had an intact uterus and at least one ovary. None of the participants were current smokers or had recent alcohol or drug dependence, and none had used hormones within the previous 6 months. The study also excluded women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, who had bleached hair or no hair, who were taking steroids, beta blockers or opioid medication, and who had recently taken NSAIDS.

Measuring hair cortisol more feasible

The study was conducted remotely, with participants using video conferencing to communicate with the study personnel and then completing study procedures at home, including 2 days of cognitive testing with the California Verbal Learning Test – Third Edition and the n-back and continuous performance tasks. The participants also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

Participants with higher levels of hair cortisol and salivary cortisol also had more severe depression symptoms (P < .001). Hair cortisol was also significantly associated with attention and working memory: Women with higher levels had fewer correct answers on the 0-back and 1-back trials (P < .01) and made more mistakes on the 2-back trial (P < .001). They also scored with less specificity on the continuous performance tasks (P = .022).

Although no association existed between hair cortisol levels and verbal learning or verbal memory (P > .05), participants with higher hair cortisol did score worse on the immediate recall trials (P = .034). Salivary cortisol levels, on the other hand, showed no association with memory recall trials, attention or working memory (P > .05).

Measuring cortisol from hair samples is more feasible than using saliva samples and may offer valuable insights regarding hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activity “to consider alongside the cognitive and mental health of late peri-/early postmenopausal women,” Dr. Metcalf told attendees. The next step is to find out whether the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis axis is a modifiable biomarker that can be used to improve executive function.

The study was limited by its small population, its cross-sectional design, and the lack of covariates in the current analyses.

Monitor symptoms in midlife

Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc, a professor of psychiatry and executive director of the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study findings were not surprising given how common the complaints of stress and depressive symptoms are.

“Mood changes are linked with acute, immediate cortisol levels at the same point in time, and cognitive symptoms were linked to more chronically elevated cortisol levels,” Dr. Joffe said in an interview. “Women and their providers should monitor for these challenging brain symptoms in midlife as they affect performance and quality of life and are linked with changes in the HPA axis as stress biomarkers.”

Because the study is small and has a cross-sectional design, it’s not possible to determine the direction of the associations or to make any inferences about causation, Dr. Joffe said.

“We cannot make the conclusion that stress is adversely affecting mood and cognitive performance given the design limitations. It is possible that mood and cognitive issues contributed to these stress markers,” Dr. Joffe said.“However, it is known that the experience of stress is linked with vulnerability to mood and cognitive symptoms, and also that mood and cognitive symptoms induce significant stress.”

The research was funded by the Menopause Society, Colorado University, the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Metcalf had no disclosures. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck, Pfizer and Sage, and has been a consultant or advisor for Bayer, Merck and Hello Therapeutics.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

“This work suggests that markers of hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activation that capture total cortisol secretion over multiple months, [such as] hair cortisol, strongly correlate with cognitive performance on attention and working memory tasks, whereas measures of more acute cortisol, [such as] salivary cortisol, may be more strongly associated with depression symptom severity and verbal learning,” Christina Metcalf, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry in the Colorado Center for Women’s Behavioral Health and Wellness at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, told attendees. “Given the associations with chronic stress, there’s a lot of potential here to increase our knowledge about how women are doing and managing stress and life stressors during this life transition,” she said.

The study involved collecting hair and saliva samples from 43 healthy women in late perimenopause or early postmenopause with an average age of 51. The participants were predominantly white and college educated. The hair sample was taken within 2 cm of the scalp, and the saliva samples were collected the day after the hair sample collection, at the start and end of a 30-minute rest period that took place between 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. local time.

All the participants had an intact uterus and at least one ovary. None of the participants were current smokers or had recent alcohol or drug dependence, and none had used hormones within the previous 6 months. The study also excluded women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, who had bleached hair or no hair, who were taking steroids, beta blockers or opioid medication, and who had recently taken NSAIDS.

Measuring hair cortisol more feasible

The study was conducted remotely, with participants using video conferencing to communicate with the study personnel and then completing study procedures at home, including 2 days of cognitive testing with the California Verbal Learning Test – Third Edition and the n-back and continuous performance tasks. The participants also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

Participants with higher levels of hair cortisol and salivary cortisol also had more severe depression symptoms (P < .001). Hair cortisol was also significantly associated with attention and working memory: Women with higher levels had fewer correct answers on the 0-back and 1-back trials (P < .01) and made more mistakes on the 2-back trial (P < .001). They also scored with less specificity on the continuous performance tasks (P = .022).

Although no association existed between hair cortisol levels and verbal learning or verbal memory (P > .05), participants with higher hair cortisol did score worse on the immediate recall trials (P = .034). Salivary cortisol levels, on the other hand, showed no association with memory recall trials, attention or working memory (P > .05).

Measuring cortisol from hair samples is more feasible than using saliva samples and may offer valuable insights regarding hypothalamic-pituitary-axis activity “to consider alongside the cognitive and mental health of late peri-/early postmenopausal women,” Dr. Metcalf told attendees. The next step is to find out whether the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis axis is a modifiable biomarker that can be used to improve executive function.

The study was limited by its small population, its cross-sectional design, and the lack of covariates in the current analyses.

Monitor symptoms in midlife

Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc, a professor of psychiatry and executive director of the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study findings were not surprising given how common the complaints of stress and depressive symptoms are.

“Mood changes are linked with acute, immediate cortisol levels at the same point in time, and cognitive symptoms were linked to more chronically elevated cortisol levels,” Dr. Joffe said in an interview. “Women and their providers should monitor for these challenging brain symptoms in midlife as they affect performance and quality of life and are linked with changes in the HPA axis as stress biomarkers.”

Because the study is small and has a cross-sectional design, it’s not possible to determine the direction of the associations or to make any inferences about causation, Dr. Joffe said.

“We cannot make the conclusion that stress is adversely affecting mood and cognitive performance given the design limitations. It is possible that mood and cognitive issues contributed to these stress markers,” Dr. Joffe said.“However, it is known that the experience of stress is linked with vulnerability to mood and cognitive symptoms, and also that mood and cognitive symptoms induce significant stress.”

The research was funded by the Menopause Society, Colorado University, the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Metcalf had no disclosures. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck, Pfizer and Sage, and has been a consultant or advisor for Bayer, Merck and Hello Therapeutics.

AT NAMS 2023

Specialized care may curb suicide risk in veterans with disabilities

TOPLINE:

Investigators speculate that veteran status may mitigate suicide risk given increased provision of disability-related care through the Department of Veterans Affairs, but they acknowledge that more research is needed to confirm this theory.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study includes analysis of self-reported data collected from 2015 to 2020 from 231,000 NSDUH respondents, 9% of whom were veterans; 20% reported at least one disability.

- Respondents were asked questions about suicide, veteran status, and the number and type of disability they had, if applicable.

- Disabilities included those related to hearing, sight, and concentration, memory, decision-making, ambulation, or functional status (at home or outside the home).

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 4.4% of the sample reported suicide ideation, planning, or attempt.

- Among participants with one disability, being a veteran was associated with a 43% lower risk of suicide planning (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57; P = .03).

- Among those with two disabilities, veterans had a 54% lower likelihood of having a history of suicide attempt, compared with nonveterans (aOR, 0.46; P = .02).

- Compared with U.S. veterans reporting 1, 2, and ≥ 3 disabilities, U.S. veterans with no disabilities were 50%, 160%, and 127% more likely, respectively, to report suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“The observed buffering effect of veteran status among people with a disability may be reflective of characteristics of disability-related care offered through the Department of Veterans Affairs,” the authors write. “It is possible that VA services could act as a protective factor for suicide-related outcomes for veterans with disabilities by improving access, quality of care, and understanding of their disability context.”

SOURCE:

Rebecca K. Blais, PhD, of Arizona State University, Tempe, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Assessments were based on self-reported information and there was no information about disability severity, which may have influenced suicide risk among veterans and nonveterans.

DISCLOSURES:

Coauthor Anne Kirby, PhD, received grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study as well as grants from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and personal fees from University of Pittsburgh outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Investigators speculate that veteran status may mitigate suicide risk given increased provision of disability-related care through the Department of Veterans Affairs, but they acknowledge that more research is needed to confirm this theory.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study includes analysis of self-reported data collected from 2015 to 2020 from 231,000 NSDUH respondents, 9% of whom were veterans; 20% reported at least one disability.

- Respondents were asked questions about suicide, veteran status, and the number and type of disability they had, if applicable.

- Disabilities included those related to hearing, sight, and concentration, memory, decision-making, ambulation, or functional status (at home or outside the home).

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 4.4% of the sample reported suicide ideation, planning, or attempt.

- Among participants with one disability, being a veteran was associated with a 43% lower risk of suicide planning (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57; P = .03).

- Among those with two disabilities, veterans had a 54% lower likelihood of having a history of suicide attempt, compared with nonveterans (aOR, 0.46; P = .02).

- Compared with U.S. veterans reporting 1, 2, and ≥ 3 disabilities, U.S. veterans with no disabilities were 50%, 160%, and 127% more likely, respectively, to report suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“The observed buffering effect of veteran status among people with a disability may be reflective of characteristics of disability-related care offered through the Department of Veterans Affairs,” the authors write. “It is possible that VA services could act as a protective factor for suicide-related outcomes for veterans with disabilities by improving access, quality of care, and understanding of their disability context.”

SOURCE:

Rebecca K. Blais, PhD, of Arizona State University, Tempe, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Assessments were based on self-reported information and there was no information about disability severity, which may have influenced suicide risk among veterans and nonveterans.

DISCLOSURES:

Coauthor Anne Kirby, PhD, received grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study as well as grants from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and personal fees from University of Pittsburgh outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Investigators speculate that veteran status may mitigate suicide risk given increased provision of disability-related care through the Department of Veterans Affairs, but they acknowledge that more research is needed to confirm this theory.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study includes analysis of self-reported data collected from 2015 to 2020 from 231,000 NSDUH respondents, 9% of whom were veterans; 20% reported at least one disability.

- Respondents were asked questions about suicide, veteran status, and the number and type of disability they had, if applicable.

- Disabilities included those related to hearing, sight, and concentration, memory, decision-making, ambulation, or functional status (at home or outside the home).

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 4.4% of the sample reported suicide ideation, planning, or attempt.

- Among participants with one disability, being a veteran was associated with a 43% lower risk of suicide planning (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57; P = .03).

- Among those with two disabilities, veterans had a 54% lower likelihood of having a history of suicide attempt, compared with nonveterans (aOR, 0.46; P = .02).

- Compared with U.S. veterans reporting 1, 2, and ≥ 3 disabilities, U.S. veterans with no disabilities were 50%, 160%, and 127% more likely, respectively, to report suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“The observed buffering effect of veteran status among people with a disability may be reflective of characteristics of disability-related care offered through the Department of Veterans Affairs,” the authors write. “It is possible that VA services could act as a protective factor for suicide-related outcomes for veterans with disabilities by improving access, quality of care, and understanding of their disability context.”

SOURCE:

Rebecca K. Blais, PhD, of Arizona State University, Tempe, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Assessments were based on self-reported information and there was no information about disability severity, which may have influenced suicide risk among veterans and nonveterans.

DISCLOSURES:

Coauthor Anne Kirby, PhD, received grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study as well as grants from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and personal fees from University of Pittsburgh outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy, linked to fracture risk

VANCOUVER – Patients who undergo either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sleeve gastrectomy are at an increased risk of fracture, compared with patients with obesity who do not undergo surgery, according to a new analysis of a predominantly male group of U.S. veterans.

Previous studies involving premenopausal women have found a risk of bone mineral density loss and fracture with bariatric surgery, but little was known about the risk among men. Research has also shown an increase in risk after RYGB, but there is less information on risks associated with sleeve gastrectomy, though it is now the most common surgery for weight loss.

Bone density loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to be significant, according to Eileen H. Koh, MD. “It’s quite a lot of bone loss, quickly,” said Dr. Koh, a graduated fellow from the endocrinology program at the University of California, San Francisco, who is moving to the University of Washington, Seattle.

Those observations generally come from studies of younger women. The purpose of the new study “was to see if we see the same risk of fracture in veterans who are older men, so kind of the opposite of the typical bariatric patient,” said Dr. Koh, who presented the research at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

The researchers analyzed data from 8,299 U.S. veterans who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (41%), RYGB (51%), adjustable gastric banding (4%), or an unspecified bariatric procedure (4%) between 2000 and 2020. They were matched with 24,877 individuals with obesity who did not undergo surgery. The investigators excluded individuals who were at high risk of fracture because of another condition, such as organ transplantation or dialysis. Men made up 70% of both surgical and nonsurgical groups. The mean age was 52 years for both, and 89% and 88% were not Hispanic or Latino, respectively. The proportion of White individuals was 72% and 64%, and the proportion of Black individuals was 18% and 24%.

After adjustment for demographic variables and comorbidities, bariatric surgery was associated with a 68% increased risk of fracture (hazard ratio, 1.68; 95% confidence interval, 1.57-1.80), including hip fractures (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.98-2.97), spine (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.61-2.06), radius/ulna (HR, 2.38; 95% CI, 2.05-2.77), humerus (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.28-1.89), pelvis (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.68-3.46), and tibia/fibula/ankle (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.33-1.69). Increased fracture risk was associated with RYGB (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.75-2.12) and sleeve gastrectomy (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.33-1.69) but not adjustable gastric banding.

Compared with sleeve gastrectomy, adjustable gastric banding was associated with a decreased risk of fracture (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.84; P = .0012).

The study’s predominantly male population is important because men also get osteoporosis and are frequently overlooked, according to Anne Schafer, MD, who was the lead author of the study. “Even after they fracture, men are sometimes less likely to get care to prevent the next fracture. We’ve shown here that especially men who are on the older side, who go through surgical weight loss, do have a higher risk of fracture compared to those who are similarly obese but have not had the operation,” said Dr. Schafer, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of endocrinology and metabolism at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.