User login

The Clinical Diversity of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects individuals worldwide.1 Although AD previously was commonly described as a skin-limited disease of childhood characterized by eczema in the flexural folds and pruritus, our current understanding supports a more heterogeneous condition.2 We review the wide range of cutaneous presentations of AD with a focus on clinical and morphological presentations across diverse skin types—commonly referred to as skin of color (SOC).

Defining SOC in Relation to AD

The terms SOC, race, and ethnicity are used interchangeably, but their true meanings are distinct. Traditionally, race has been defined as a biological concept, grouping cohorts of individuals with a large degree of shared ancestry and genetic similarities,3 and ethnicity as a social construct, grouping individuals with common racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds.4 In practice, both concepts can broadly be envisioned as mixed social, political, and economic constructs, as no one gene or biologic characteristic distinguishes one racial or ethnic group from another.5

The US Census Bureau recognizes 5 racial groupings: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.6 Hispanic or Latinx origin is considered an ethnicity. It is important to note the limitations of these labels, as they do not completely encapsulate the heterogeneity of the US population. Overgeneralization of racial and ethnic categories may dull or obscure true differences among populations.7

From an evolutionary perspective, skin pigmentation represents the product of 2 opposing clines produced by natural selection in response to both need for and protection from UV radiation across lattitudes.8 Defining SOC is not quite as simple. Skin of color often is equated with certain racial/ethnic groups, or even binary categories of Black vs non-Black or White vs non-White. Others may use the Fitzpatrick scale to discuss SOC, though this scale was originally created to measure the response of skin to UVA radiation exposure.9 The reality is that SOC is a complex term that cannot simply be defined by a certain group of skin tones, races, ethnicities, and/or Fitzpatrick skin types. With this in mind, SOC in the context of this article will often refer to non-White individuals based on the investigators’ terminology, but this definition is not all-encompassing.

Historically in medicine, racial/ethnic differences in outcomes have been equated to differences in biology/genetics without consideration of many external factors.10 The effects of racism, economic stability, health care access, environment, and education quality rarely are discussed, though they have a major impact on health and may better define associations with race or an SOC population. A discussion of the structural and social determinants of health contributing to disease outcomes should accompany any race-based guidelines to prevent inaccurately pathologizing race or SOC.10

Within the scope of AD, social determinants of health play an important role in contributing to disease morbidity. Environmental factors, including tobacco smoke, climate, pollutants, water hardness, und urban living, are related to AD prevalence and severity.11 Higher socioeconomic status is associated with increased AD rates,12 yet lower socioeconomic status is associated with more severe disease.13 Barriers to health care access and suboptimal care drive worse AD outcomes.14 Underrepresentation in clinical trials prevents the generalizability and safety of AD treatments.15 Disparities in these health determinants associated with AD likely are among the most important drivers of observed differences in disease presentation, severity, burden, and even prevalence—more so than genetics or ancestry alone16—yet this relationship is poorly understood and often presented as a consequence of race. It is critical to redefine the narrative when considering the heterogeneous presentations of AD in patients with SOC and acknowledge the limitations of current terminology when attempting to capture clinical diversity in AD, including in this review, where published findings often are limited by race-based analysis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of AD has been increasing over the last few decades, and rates vary by region. In the United States, the prevalence of childhood and adult AD is 13% and 7%, respectively.17,18 Globally, higher rates of pediatric AD are seen in Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia (SEA), and Latin America compared to South Asia, Northern Europe, and Eastern Europe.19 The prevalence of AD varies widely within the same continent and country; for example, throughout Africa, prevalence was found to be anywhere between 4.7% and 23.3%.20

Lesion Morphology

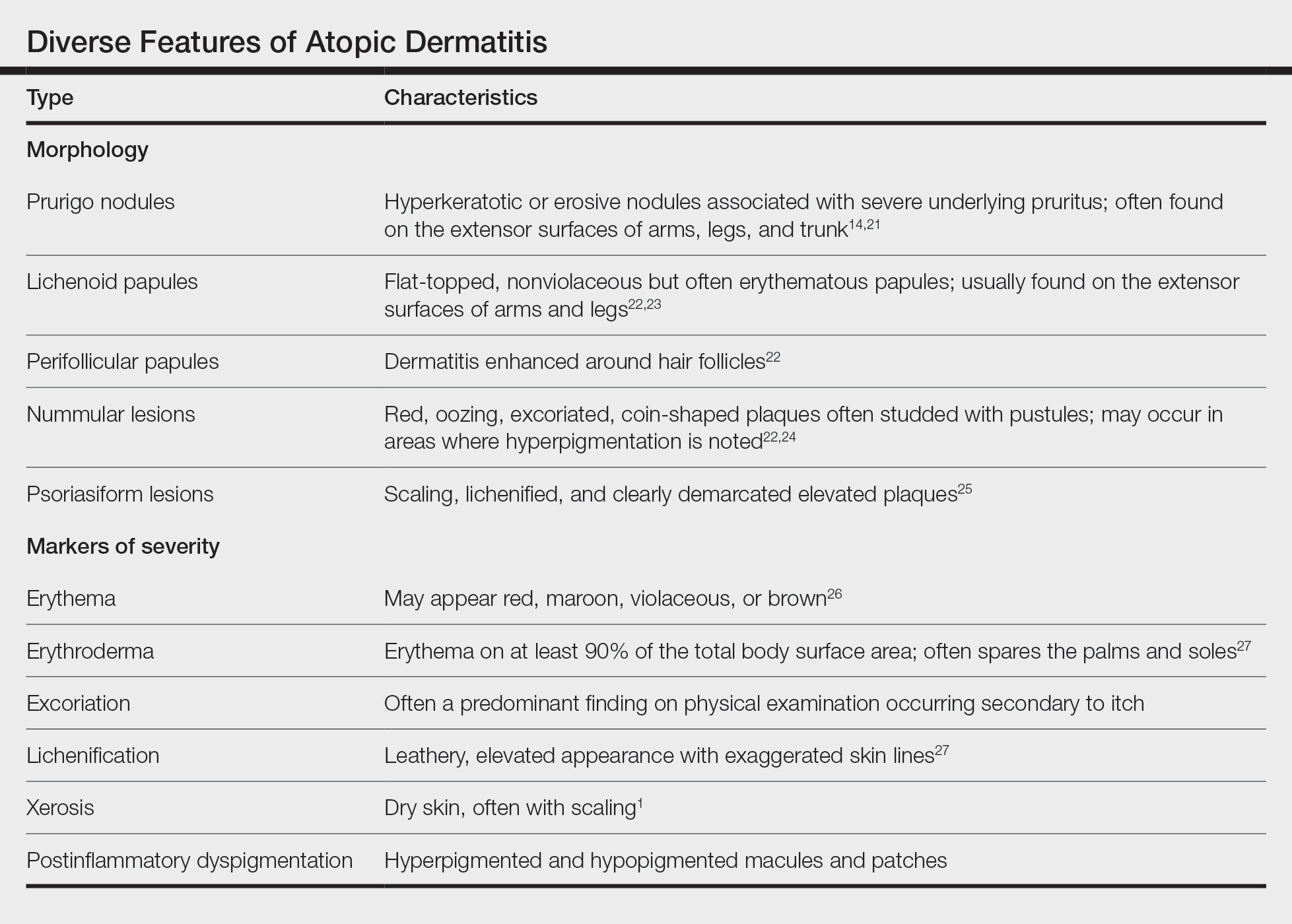

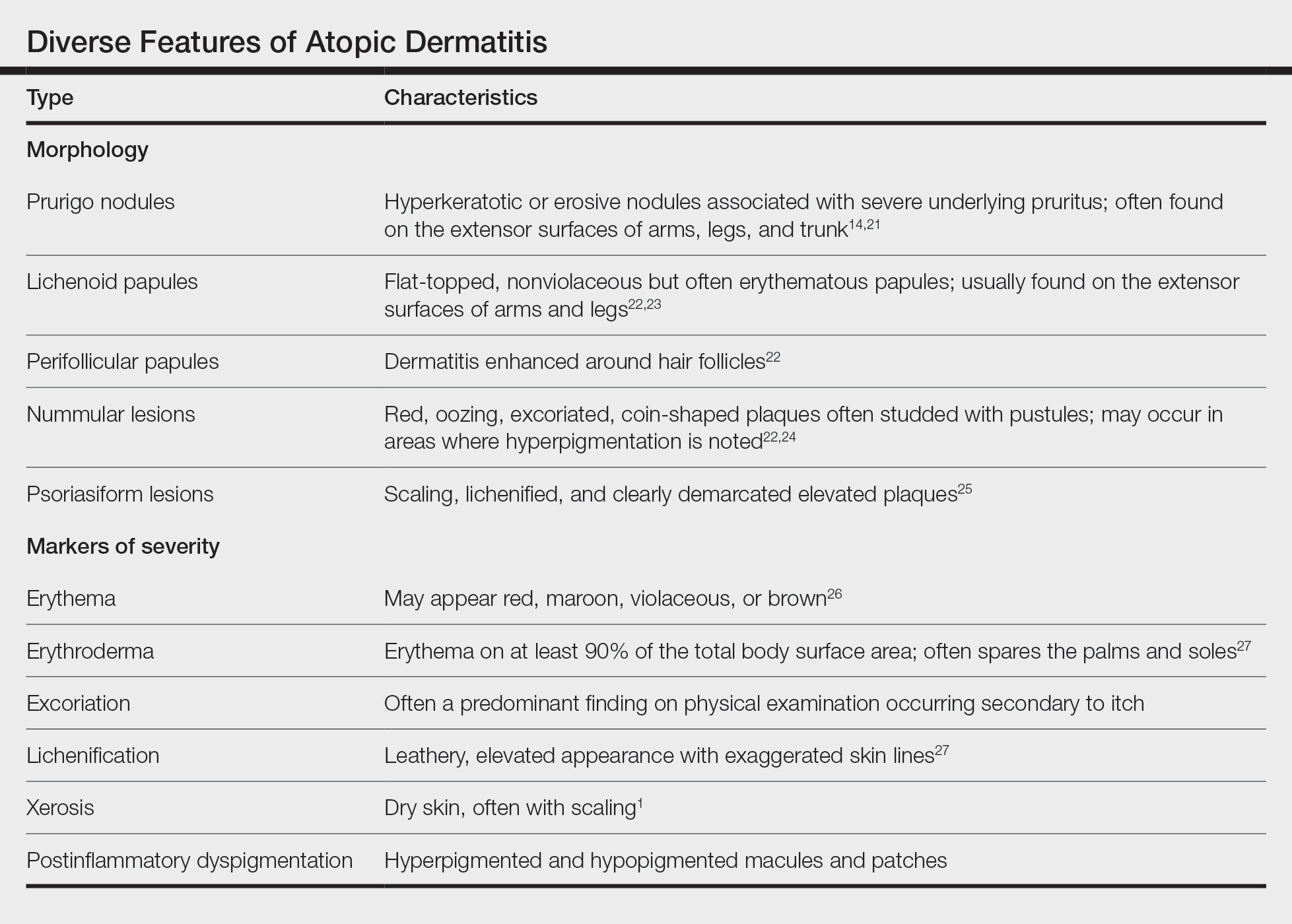

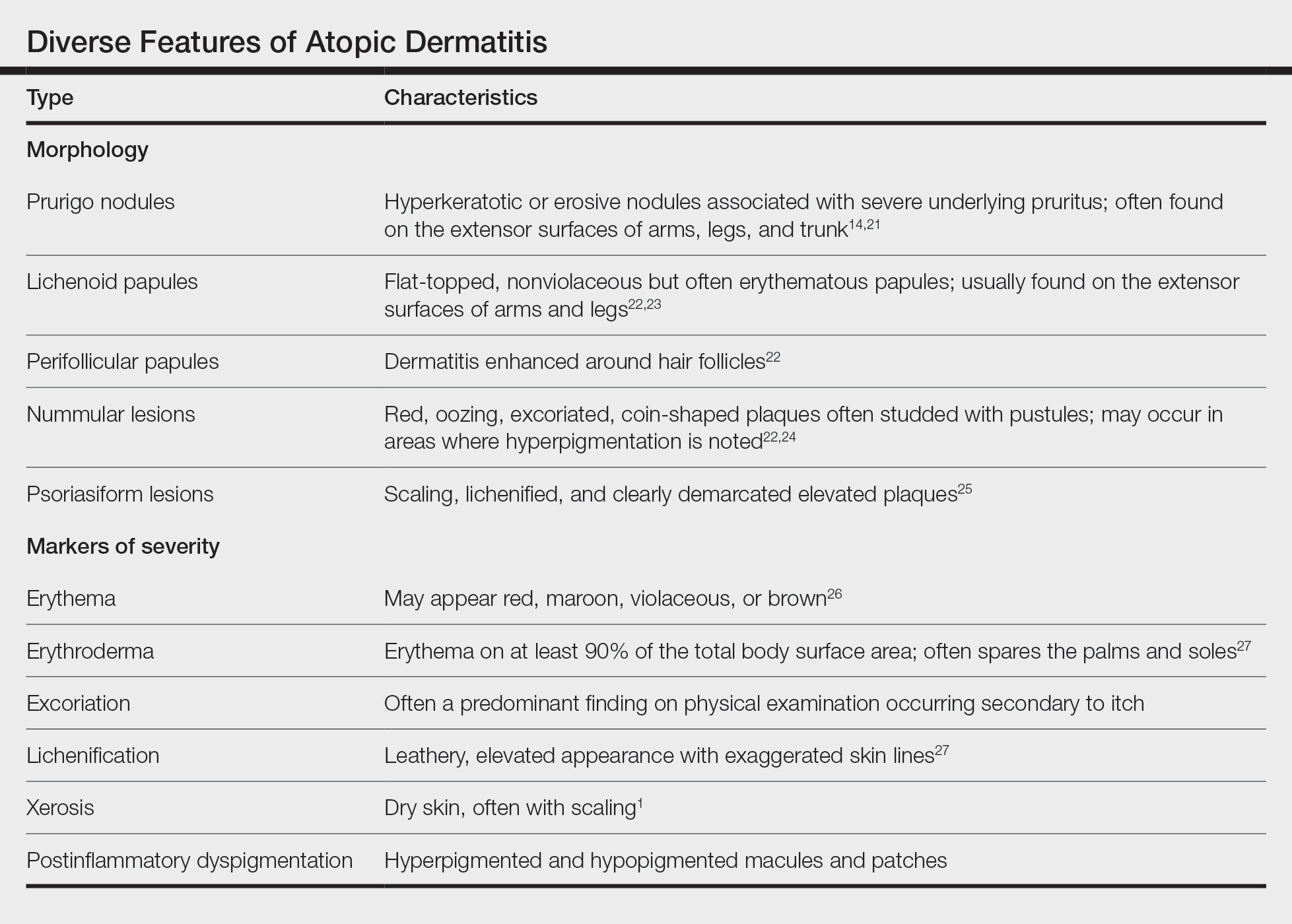

Although AD lesions often are described as pruritic erythematous papules and plaques, other common morphologies in SOC populations include prurigo nodules, lichenoid papules, perifollicular papules, nummular lesions, and psoriasiform lesions (Table). Instead of applying normative terms such as classic vs atypical to AD morphology, we urge clinicians to be familiar with the full spectrum of AD skin signs.

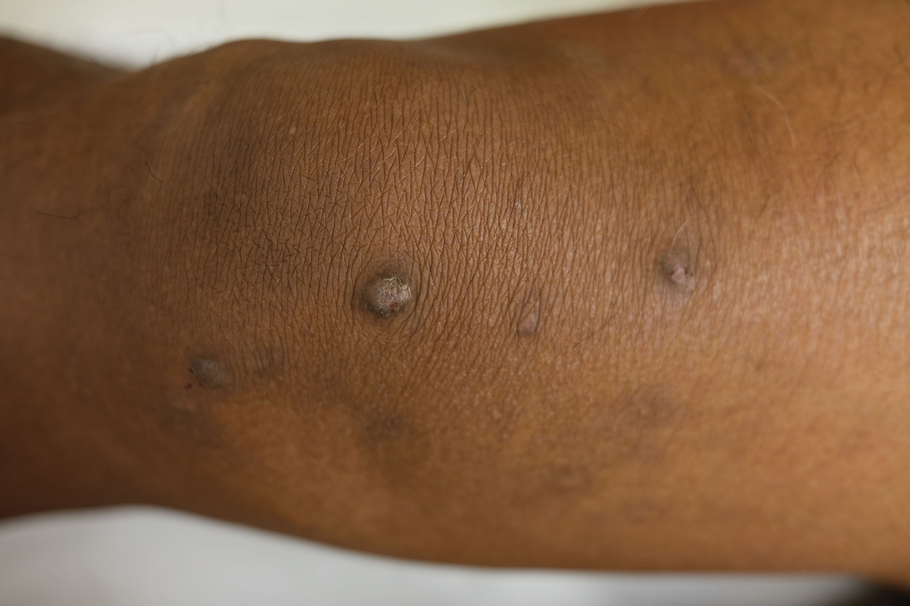

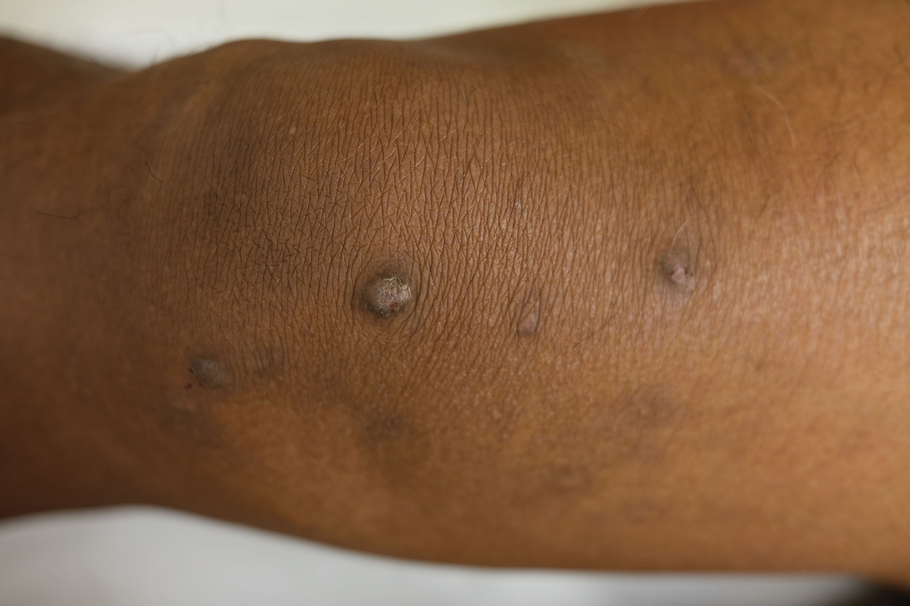

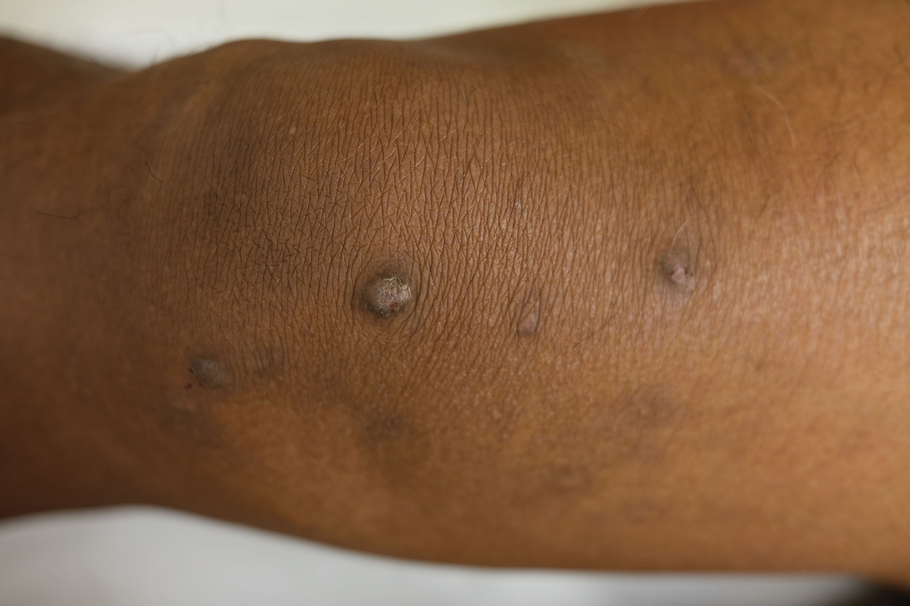

Prurigo Nodules—Prurigo nodules are hyperkeratotic or erosive nodules with severe pruritus, often grouped symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1).14,21 The skin between lesions usually is unaffected but can be dry or lichenified or display postinflammatory pigmentary changes.14 Prurigo nodules are common. In a study of a cohort of patients with prurigo nodularis (N=108), nearly half (46.3%) were determined to have either an atopic predisposition or underlying AD as a contributing cause of the lesions.21

Prurigo nodules as a phenotype of AD may be more common in certain SOC populations. Studies from SEA have reported a higher prevalence of prurigo nodules among patients with AD.28 Although there are limited formal studies assessing the true prevalence of this lesion type in African American AD patients in the United States, clinical evidence supports more frequent appearance of prurigo nodules in non-White patients.29 Contributing factors include suboptimal care for AD in SOC populations and/or barriers to health care access, resulting in more severe disease that increases the risk for this lesion type.14

Lichenoid Papules—Papular lichenoid lesions often present on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs in AD (Figure 2).22 In a study of Nigerian patients with AD (N=1019), 54.1% had lichenoid papules.24 A systematic review of AD characteristics by region similarly reported an increased prevalence of this lesion type in African studies.28 Lichenoid variants of AD have been well described in SOC patients in the United States.23 In contrast to the lesions of lichen planus, the lichenoid papules of AD usually are round, rarely display koebnerization, do not have Wickham striae, and predominantly are located on extensor surfaces.

Perifollicular Papules—Perifollicular accentuation—dermatitis enhanced around hair follicles—is a well-described lesional morphology of AD that is noted in all racial/ethnic groups (Figure 3).22 In fact, perifollicular accentuation is included as one of the Hanifin and Rajka minor criteria for AD.30 Studies performed in Nigeria and India showed perifollicular accentuation in up to 70% of AD patients.24,31 In a study of adult Thai patients (N=56), follicular lesions were found more frequently in intrinsic AD (29%) compared with extrinsic AD (12%).32

Nummular and Psoriasiform Lesions—Nummular lesions may be red, oozing, excoriated, studded with pustules and/or present on the extensor extremities (Figure 4). In SOC patients, these lesions often occur in areas where hyperpigmentation is noted.22 Studies in the United States and Mexico demonstrated that 15% to 17% of AD patients displayed nummular lesions.23,33 Similar to follicular papules, nummular lesions were linked to intrinsic AD in a study of adult Thai patients.32

Psoriasiform lesions show prominent scaling, lichenification, and clear demarcation.25 It has been reported that the psoriasiform phenotype of AD is more common in Asian patients,25 though this is likely an oversimplification. The participants in these studies were of Japanese and Korean ancestry, which covers a broad geographic region, and the grouping of individuals under a heterogeneous Asian category is unlikely to convey generalizable biologic or clinical information. Unsurprisingly, a systematic review of AD characteristics by region noted considerable phenotypical differences among patients in SEA, East Asia, Iran, and India.28

Disease Severity

Several factors contribute to AD disease severity,34 including objective assessments of inflammation, such as erythema and lichenification (Table), as well as subjective measures of symptoms, such as itch. The severity of AD is exacerbated by the social determinants of health, and a lower socioeconomic status, lower household income, lower parental education level and health, dilapidated housing, and presence of garbage on the street are among factors linked to worse AD disease severity.13,17 Although non-White individuals with AD often are reported to have more severe disease than their White counterparts,35 these types of health determinants may be the most relevant causes of observed differences.

Erythema—Erythema is a feature of inflammation used in the AD severity assessment. Erythema may appear in shades beyond red, including maroon, violaceous, or brown, in patients with darker pigmented skin, which may contribute to diagnosis of AD at a later disease stage.26 Multiple AD severity scoring tools, such as the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis and Eczema Area and Severity Index, include erythema as a measure, which can lead to underestimation of AD severity in SOC populations. After adjusting for erythema score, one study found that Black children with AD had a risk for severe disease that was 6-times higher than White children.36 Dermatological training must adequately teach physicians to recognize erythema across all skin tones.37

Erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis) is rapidly spreading erythema on at least 90% of the total body surface area, often sparing the palms and soles.32 Erythroderma is a potentially life-threatening manifestation of severe AD. Although erythroderma may have many underlying causes, AD has been reported to be the cause in 5% to 24% of cases,38 and compared to studies in Europe, the prevalence of erythroderma was higher in East Asian studies of AD.28

Excoriation and Pruritus—Pruritus is a defining characteristic of AD, and the resulting excoriations often are predominant on physical examination, which is a key part of severity scores. Itch is the most prevalent symptom among patients with AD, and a greater itch severity has been linked to decreased health-related quality of life, increased mental health symptoms, impaired sleep, and decreased daily function.39,40 The burden of itch may be greater in SOC populations. The impact of itch on quality of life among US military veterans was significantly higher in those who identified as non-White (P=.05).41 In another study of US military veterans, African American individuals reported a significantly higher emotional impact from itch (P<.05).42

Lichenification—Lichenification is thickening of the skin due to chronic rubbing and scratching that causes a leathery elevated appearance with exaggerated skin lines.27 Lichenification is included as a factor in common clinical scoring tools, with greater lichenification indicating greater disease severity. Studies from SEA and Africa suggested a higher prevalence of lichenification in AD patients.28 A greater itch burden and thus increased rubbing/scratching in these populations may contribute to some of these findings.42,43

Xerosis—Xerosis (or dry skin) is a common finding in AD that results from increased transepidermal water loss due to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier.44 In a systematic review of AD characteristics by region, xerosis was among the top 5 most reported AD features globally in all regions except SEA.28 Xerosis may be more stigmatizing in SOC populations because of the greater visibility of scaling and dryness on darker skin tones.1

Postinflammatory Dyspigmentation—Postinflammatory pigment alteration may be a consequence of AD lesions, resulting in hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules and patches. Patients with AD with darker skin tones are more likely to develop postinflammatory dyspigmentation.26 A study of AD patients in Nigeria found that 63% displayed postinflammatory dyspigmentation.45 Dyschromia, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, is one of the most common reasons for SOC patients to seek dermatologic care.46 Postinflammatory pigment alteration can cause severe distress in patients, even more so than the cutaneous findings of AD. Although altered skin pigmentation usually returns to normal over weeks to months, skin depigmentation from chronic excoriation may be permanent.26 Appropriately treating hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation in SOC populations can greatly improve quality of life.47

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory disease that presents with many clinical phenotypes. Dermatologists should be trained to recognize the heterogeneous signs of AD present across the diverse skin types in SOC patients. Future research should move away from race-based analyses and focus on the complex interplay of environmental factors, social determinants of health, and skin pigmentation, as well as how these factors drive variations in AD lesional morphology and inflammation.

- Alexis A, Woolery-Lloyd H, Andriessen A, et al. Insights in skin of color patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of skincare in improving outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:462-470. doi:10.36849/jdd.6609

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. The heterogeneity of atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:172-176. doi:10.36849/JDD.6408

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F. Defining skin of color. Cutis. 2002;69:435-437.

- Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: the essential role of cultural broker programs. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/culturalbroker/8_Definitions/2_Definitions.html#:~:text=ethnic%3A%20Of%20or%20relating%20to,or%20cultural%20origin%20or%20background

- Shoo BA, Kashani-Sabet M. Melanoma arising in African-, Asian-, Latino- and Native-American populations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:96-102. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.005

- US Census Bureau. About the topic of race. Revised March 1, 2022. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

- Williams HC. Have you ever seen an Asian/Pacific Islander? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:673-674. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.5.673

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Colloquium paper: human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(Suppl 2):8962-8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871. doi:10.1001/archderm.124.6.869

- Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race—the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:872-878. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2025768

- Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:15-26. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2016.1212660

- Fu T, Keiser E, Linos E, et al. Eczema and sensitization to common allergens in the United States: a multiethnic, population-based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/pde.12237

- Tackett KJ, Jenkins F, Morrell DS, et al. Structural racism and its influence on the severity of atopic dermatitis in African American children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:142-146. doi:10.1111/pde.14058

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Polcari I, Becker L, Stein SL, et al. Filaggrin gene mutations in African Americans with both ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:489-492. doi:10.1111/pde.12355

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000034

- Hua T, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: epidemiology, association with marital status, and atopy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:622-624. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.019

- Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, et al. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251-8.e23. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009

- Ait-Khaled N, Odhiambo J, Pearce N, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Africa: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. Allergy. 2007;62:247-258. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01325.x

- Iking A, Grundmann S, Chatzigeorgakidis E, et al. Prurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:550-557. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04481.x

- Silverberg NB. Typical and atypical clinical appearance of atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:354-359. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.03.007

- Allen HB, Jones NP, Bowen SE. Lichenoid and other clinical presentations of atopic dermatitis in an inner city practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:503-504. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.033

- Nnoruka EN. Current epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:739-744. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02360.x

- Noda S, Suárez-Fariñas M, Ungar B, et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1254-1264. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Girolomoni G, de Bruin-Weller M, Aoki V, et al. Nomenclature and clinical phenotypes of atopic dermatitis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211002979. doi:10.1177/20406223211002979

- Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:390-401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.035

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01740.x

- Hanifin JM. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Dutta A, De A, Das S, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of the usefulness of the minor features of Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:583-590. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_1046_20

- Kulthanan K, Boochangkool K, Tuchinda P, et al. Clinical features of the extrinsic and intrinsic types of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:80-86. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.2.80

- Julián-Gónzalez RE, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Durán-McKinster C, et al. Less common clinical manifestations of atopic dermatitis: prevalence by age. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:580-583. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01739.x

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Evaluating the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:688-689. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.005

- Kim Y, Blomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- McKenzie S, Brown-Korsah JB, Syder NC, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color. part II: differences in clinical presentation and disparities in cutaneous disorders in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1261-1270. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.067

- Cuellar-Barboza A, Ocampo-Candiani J, Herz-Ruelas ME. A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of adult erythroderma [in English, Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:777-790. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2018.05.011

- Lei DK, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, et al. Validation of patient-reported outcomes information system sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:875-882. doi:10.1111/bjd.18920

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340-347. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006

- Carr CW, Veledar E, Chen SC. Factors mediating the impact of chronic pruritus on quality of life. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:613-620. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7696

- Shaw FM, Luk KMH, Chen KH, et al. Racial disparities in the impact of chronic pruritus: a cross-sectional study on quality of life and resource utilization in United States veterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.016

- Oh CC, Li H, Lee W, et al. Biopsychosocial factors associated with prurigo nodularis in endogenous eczema. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:525. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164451

- Vyumvuhore R, Michael-Jubeli R, Verzeaux L, et al. Lipid organization in xerosis: the key of the problem? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:549-554. doi:10.1111/ics.12496

- George AO. Atopic dermatitis in Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:237-239. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb04811.x

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Dupilumab improves atopic dermatitis and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patient with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:776-778. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4937

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects individuals worldwide.1 Although AD previously was commonly described as a skin-limited disease of childhood characterized by eczema in the flexural folds and pruritus, our current understanding supports a more heterogeneous condition.2 We review the wide range of cutaneous presentations of AD with a focus on clinical and morphological presentations across diverse skin types—commonly referred to as skin of color (SOC).

Defining SOC in Relation to AD

The terms SOC, race, and ethnicity are used interchangeably, but their true meanings are distinct. Traditionally, race has been defined as a biological concept, grouping cohorts of individuals with a large degree of shared ancestry and genetic similarities,3 and ethnicity as a social construct, grouping individuals with common racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds.4 In practice, both concepts can broadly be envisioned as mixed social, political, and economic constructs, as no one gene or biologic characteristic distinguishes one racial or ethnic group from another.5

The US Census Bureau recognizes 5 racial groupings: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.6 Hispanic or Latinx origin is considered an ethnicity. It is important to note the limitations of these labels, as they do not completely encapsulate the heterogeneity of the US population. Overgeneralization of racial and ethnic categories may dull or obscure true differences among populations.7

From an evolutionary perspective, skin pigmentation represents the product of 2 opposing clines produced by natural selection in response to both need for and protection from UV radiation across lattitudes.8 Defining SOC is not quite as simple. Skin of color often is equated with certain racial/ethnic groups, or even binary categories of Black vs non-Black or White vs non-White. Others may use the Fitzpatrick scale to discuss SOC, though this scale was originally created to measure the response of skin to UVA radiation exposure.9 The reality is that SOC is a complex term that cannot simply be defined by a certain group of skin tones, races, ethnicities, and/or Fitzpatrick skin types. With this in mind, SOC in the context of this article will often refer to non-White individuals based on the investigators’ terminology, but this definition is not all-encompassing.

Historically in medicine, racial/ethnic differences in outcomes have been equated to differences in biology/genetics without consideration of many external factors.10 The effects of racism, economic stability, health care access, environment, and education quality rarely are discussed, though they have a major impact on health and may better define associations with race or an SOC population. A discussion of the structural and social determinants of health contributing to disease outcomes should accompany any race-based guidelines to prevent inaccurately pathologizing race or SOC.10

Within the scope of AD, social determinants of health play an important role in contributing to disease morbidity. Environmental factors, including tobacco smoke, climate, pollutants, water hardness, und urban living, are related to AD prevalence and severity.11 Higher socioeconomic status is associated with increased AD rates,12 yet lower socioeconomic status is associated with more severe disease.13 Barriers to health care access and suboptimal care drive worse AD outcomes.14 Underrepresentation in clinical trials prevents the generalizability and safety of AD treatments.15 Disparities in these health determinants associated with AD likely are among the most important drivers of observed differences in disease presentation, severity, burden, and even prevalence—more so than genetics or ancestry alone16—yet this relationship is poorly understood and often presented as a consequence of race. It is critical to redefine the narrative when considering the heterogeneous presentations of AD in patients with SOC and acknowledge the limitations of current terminology when attempting to capture clinical diversity in AD, including in this review, where published findings often are limited by race-based analysis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of AD has been increasing over the last few decades, and rates vary by region. In the United States, the prevalence of childhood and adult AD is 13% and 7%, respectively.17,18 Globally, higher rates of pediatric AD are seen in Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia (SEA), and Latin America compared to South Asia, Northern Europe, and Eastern Europe.19 The prevalence of AD varies widely within the same continent and country; for example, throughout Africa, prevalence was found to be anywhere between 4.7% and 23.3%.20

Lesion Morphology

Although AD lesions often are described as pruritic erythematous papules and plaques, other common morphologies in SOC populations include prurigo nodules, lichenoid papules, perifollicular papules, nummular lesions, and psoriasiform lesions (Table). Instead of applying normative terms such as classic vs atypical to AD morphology, we urge clinicians to be familiar with the full spectrum of AD skin signs.

Prurigo Nodules—Prurigo nodules are hyperkeratotic or erosive nodules with severe pruritus, often grouped symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1).14,21 The skin between lesions usually is unaffected but can be dry or lichenified or display postinflammatory pigmentary changes.14 Prurigo nodules are common. In a study of a cohort of patients with prurigo nodularis (N=108), nearly half (46.3%) were determined to have either an atopic predisposition or underlying AD as a contributing cause of the lesions.21

Prurigo nodules as a phenotype of AD may be more common in certain SOC populations. Studies from SEA have reported a higher prevalence of prurigo nodules among patients with AD.28 Although there are limited formal studies assessing the true prevalence of this lesion type in African American AD patients in the United States, clinical evidence supports more frequent appearance of prurigo nodules in non-White patients.29 Contributing factors include suboptimal care for AD in SOC populations and/or barriers to health care access, resulting in more severe disease that increases the risk for this lesion type.14

Lichenoid Papules—Papular lichenoid lesions often present on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs in AD (Figure 2).22 In a study of Nigerian patients with AD (N=1019), 54.1% had lichenoid papules.24 A systematic review of AD characteristics by region similarly reported an increased prevalence of this lesion type in African studies.28 Lichenoid variants of AD have been well described in SOC patients in the United States.23 In contrast to the lesions of lichen planus, the lichenoid papules of AD usually are round, rarely display koebnerization, do not have Wickham striae, and predominantly are located on extensor surfaces.

Perifollicular Papules—Perifollicular accentuation—dermatitis enhanced around hair follicles—is a well-described lesional morphology of AD that is noted in all racial/ethnic groups (Figure 3).22 In fact, perifollicular accentuation is included as one of the Hanifin and Rajka minor criteria for AD.30 Studies performed in Nigeria and India showed perifollicular accentuation in up to 70% of AD patients.24,31 In a study of adult Thai patients (N=56), follicular lesions were found more frequently in intrinsic AD (29%) compared with extrinsic AD (12%).32

Nummular and Psoriasiform Lesions—Nummular lesions may be red, oozing, excoriated, studded with pustules and/or present on the extensor extremities (Figure 4). In SOC patients, these lesions often occur in areas where hyperpigmentation is noted.22 Studies in the United States and Mexico demonstrated that 15% to 17% of AD patients displayed nummular lesions.23,33 Similar to follicular papules, nummular lesions were linked to intrinsic AD in a study of adult Thai patients.32

Psoriasiform lesions show prominent scaling, lichenification, and clear demarcation.25 It has been reported that the psoriasiform phenotype of AD is more common in Asian patients,25 though this is likely an oversimplification. The participants in these studies were of Japanese and Korean ancestry, which covers a broad geographic region, and the grouping of individuals under a heterogeneous Asian category is unlikely to convey generalizable biologic or clinical information. Unsurprisingly, a systematic review of AD characteristics by region noted considerable phenotypical differences among patients in SEA, East Asia, Iran, and India.28

Disease Severity

Several factors contribute to AD disease severity,34 including objective assessments of inflammation, such as erythema and lichenification (Table), as well as subjective measures of symptoms, such as itch. The severity of AD is exacerbated by the social determinants of health, and a lower socioeconomic status, lower household income, lower parental education level and health, dilapidated housing, and presence of garbage on the street are among factors linked to worse AD disease severity.13,17 Although non-White individuals with AD often are reported to have more severe disease than their White counterparts,35 these types of health determinants may be the most relevant causes of observed differences.

Erythema—Erythema is a feature of inflammation used in the AD severity assessment. Erythema may appear in shades beyond red, including maroon, violaceous, or brown, in patients with darker pigmented skin, which may contribute to diagnosis of AD at a later disease stage.26 Multiple AD severity scoring tools, such as the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis and Eczema Area and Severity Index, include erythema as a measure, which can lead to underestimation of AD severity in SOC populations. After adjusting for erythema score, one study found that Black children with AD had a risk for severe disease that was 6-times higher than White children.36 Dermatological training must adequately teach physicians to recognize erythema across all skin tones.37

Erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis) is rapidly spreading erythema on at least 90% of the total body surface area, often sparing the palms and soles.32 Erythroderma is a potentially life-threatening manifestation of severe AD. Although erythroderma may have many underlying causes, AD has been reported to be the cause in 5% to 24% of cases,38 and compared to studies in Europe, the prevalence of erythroderma was higher in East Asian studies of AD.28

Excoriation and Pruritus—Pruritus is a defining characteristic of AD, and the resulting excoriations often are predominant on physical examination, which is a key part of severity scores. Itch is the most prevalent symptom among patients with AD, and a greater itch severity has been linked to decreased health-related quality of life, increased mental health symptoms, impaired sleep, and decreased daily function.39,40 The burden of itch may be greater in SOC populations. The impact of itch on quality of life among US military veterans was significantly higher in those who identified as non-White (P=.05).41 In another study of US military veterans, African American individuals reported a significantly higher emotional impact from itch (P<.05).42

Lichenification—Lichenification is thickening of the skin due to chronic rubbing and scratching that causes a leathery elevated appearance with exaggerated skin lines.27 Lichenification is included as a factor in common clinical scoring tools, with greater lichenification indicating greater disease severity. Studies from SEA and Africa suggested a higher prevalence of lichenification in AD patients.28 A greater itch burden and thus increased rubbing/scratching in these populations may contribute to some of these findings.42,43

Xerosis—Xerosis (or dry skin) is a common finding in AD that results from increased transepidermal water loss due to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier.44 In a systematic review of AD characteristics by region, xerosis was among the top 5 most reported AD features globally in all regions except SEA.28 Xerosis may be more stigmatizing in SOC populations because of the greater visibility of scaling and dryness on darker skin tones.1

Postinflammatory Dyspigmentation—Postinflammatory pigment alteration may be a consequence of AD lesions, resulting in hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules and patches. Patients with AD with darker skin tones are more likely to develop postinflammatory dyspigmentation.26 A study of AD patients in Nigeria found that 63% displayed postinflammatory dyspigmentation.45 Dyschromia, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, is one of the most common reasons for SOC patients to seek dermatologic care.46 Postinflammatory pigment alteration can cause severe distress in patients, even more so than the cutaneous findings of AD. Although altered skin pigmentation usually returns to normal over weeks to months, skin depigmentation from chronic excoriation may be permanent.26 Appropriately treating hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation in SOC populations can greatly improve quality of life.47

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory disease that presents with many clinical phenotypes. Dermatologists should be trained to recognize the heterogeneous signs of AD present across the diverse skin types in SOC patients. Future research should move away from race-based analyses and focus on the complex interplay of environmental factors, social determinants of health, and skin pigmentation, as well as how these factors drive variations in AD lesional morphology and inflammation.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects individuals worldwide.1 Although AD previously was commonly described as a skin-limited disease of childhood characterized by eczema in the flexural folds and pruritus, our current understanding supports a more heterogeneous condition.2 We review the wide range of cutaneous presentations of AD with a focus on clinical and morphological presentations across diverse skin types—commonly referred to as skin of color (SOC).

Defining SOC in Relation to AD

The terms SOC, race, and ethnicity are used interchangeably, but their true meanings are distinct. Traditionally, race has been defined as a biological concept, grouping cohorts of individuals with a large degree of shared ancestry and genetic similarities,3 and ethnicity as a social construct, grouping individuals with common racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds.4 In practice, both concepts can broadly be envisioned as mixed social, political, and economic constructs, as no one gene or biologic characteristic distinguishes one racial or ethnic group from another.5

The US Census Bureau recognizes 5 racial groupings: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.6 Hispanic or Latinx origin is considered an ethnicity. It is important to note the limitations of these labels, as they do not completely encapsulate the heterogeneity of the US population. Overgeneralization of racial and ethnic categories may dull or obscure true differences among populations.7

From an evolutionary perspective, skin pigmentation represents the product of 2 opposing clines produced by natural selection in response to both need for and protection from UV radiation across lattitudes.8 Defining SOC is not quite as simple. Skin of color often is equated with certain racial/ethnic groups, or even binary categories of Black vs non-Black or White vs non-White. Others may use the Fitzpatrick scale to discuss SOC, though this scale was originally created to measure the response of skin to UVA radiation exposure.9 The reality is that SOC is a complex term that cannot simply be defined by a certain group of skin tones, races, ethnicities, and/or Fitzpatrick skin types. With this in mind, SOC in the context of this article will often refer to non-White individuals based on the investigators’ terminology, but this definition is not all-encompassing.

Historically in medicine, racial/ethnic differences in outcomes have been equated to differences in biology/genetics without consideration of many external factors.10 The effects of racism, economic stability, health care access, environment, and education quality rarely are discussed, though they have a major impact on health and may better define associations with race or an SOC population. A discussion of the structural and social determinants of health contributing to disease outcomes should accompany any race-based guidelines to prevent inaccurately pathologizing race or SOC.10

Within the scope of AD, social determinants of health play an important role in contributing to disease morbidity. Environmental factors, including tobacco smoke, climate, pollutants, water hardness, und urban living, are related to AD prevalence and severity.11 Higher socioeconomic status is associated with increased AD rates,12 yet lower socioeconomic status is associated with more severe disease.13 Barriers to health care access and suboptimal care drive worse AD outcomes.14 Underrepresentation in clinical trials prevents the generalizability and safety of AD treatments.15 Disparities in these health determinants associated with AD likely are among the most important drivers of observed differences in disease presentation, severity, burden, and even prevalence—more so than genetics or ancestry alone16—yet this relationship is poorly understood and often presented as a consequence of race. It is critical to redefine the narrative when considering the heterogeneous presentations of AD in patients with SOC and acknowledge the limitations of current terminology when attempting to capture clinical diversity in AD, including in this review, where published findings often are limited by race-based analysis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of AD has been increasing over the last few decades, and rates vary by region. In the United States, the prevalence of childhood and adult AD is 13% and 7%, respectively.17,18 Globally, higher rates of pediatric AD are seen in Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia (SEA), and Latin America compared to South Asia, Northern Europe, and Eastern Europe.19 The prevalence of AD varies widely within the same continent and country; for example, throughout Africa, prevalence was found to be anywhere between 4.7% and 23.3%.20

Lesion Morphology

Although AD lesions often are described as pruritic erythematous papules and plaques, other common morphologies in SOC populations include prurigo nodules, lichenoid papules, perifollicular papules, nummular lesions, and psoriasiform lesions (Table). Instead of applying normative terms such as classic vs atypical to AD morphology, we urge clinicians to be familiar with the full spectrum of AD skin signs.

Prurigo Nodules—Prurigo nodules are hyperkeratotic or erosive nodules with severe pruritus, often grouped symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1).14,21 The skin between lesions usually is unaffected but can be dry or lichenified or display postinflammatory pigmentary changes.14 Prurigo nodules are common. In a study of a cohort of patients with prurigo nodularis (N=108), nearly half (46.3%) were determined to have either an atopic predisposition or underlying AD as a contributing cause of the lesions.21

Prurigo nodules as a phenotype of AD may be more common in certain SOC populations. Studies from SEA have reported a higher prevalence of prurigo nodules among patients with AD.28 Although there are limited formal studies assessing the true prevalence of this lesion type in African American AD patients in the United States, clinical evidence supports more frequent appearance of prurigo nodules in non-White patients.29 Contributing factors include suboptimal care for AD in SOC populations and/or barriers to health care access, resulting in more severe disease that increases the risk for this lesion type.14

Lichenoid Papules—Papular lichenoid lesions often present on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs in AD (Figure 2).22 In a study of Nigerian patients with AD (N=1019), 54.1% had lichenoid papules.24 A systematic review of AD characteristics by region similarly reported an increased prevalence of this lesion type in African studies.28 Lichenoid variants of AD have been well described in SOC patients in the United States.23 In contrast to the lesions of lichen planus, the lichenoid papules of AD usually are round, rarely display koebnerization, do not have Wickham striae, and predominantly are located on extensor surfaces.

Perifollicular Papules—Perifollicular accentuation—dermatitis enhanced around hair follicles—is a well-described lesional morphology of AD that is noted in all racial/ethnic groups (Figure 3).22 In fact, perifollicular accentuation is included as one of the Hanifin and Rajka minor criteria for AD.30 Studies performed in Nigeria and India showed perifollicular accentuation in up to 70% of AD patients.24,31 In a study of adult Thai patients (N=56), follicular lesions were found more frequently in intrinsic AD (29%) compared with extrinsic AD (12%).32

Nummular and Psoriasiform Lesions—Nummular lesions may be red, oozing, excoriated, studded with pustules and/or present on the extensor extremities (Figure 4). In SOC patients, these lesions often occur in areas where hyperpigmentation is noted.22 Studies in the United States and Mexico demonstrated that 15% to 17% of AD patients displayed nummular lesions.23,33 Similar to follicular papules, nummular lesions were linked to intrinsic AD in a study of adult Thai patients.32

Psoriasiform lesions show prominent scaling, lichenification, and clear demarcation.25 It has been reported that the psoriasiform phenotype of AD is more common in Asian patients,25 though this is likely an oversimplification. The participants in these studies were of Japanese and Korean ancestry, which covers a broad geographic region, and the grouping of individuals under a heterogeneous Asian category is unlikely to convey generalizable biologic or clinical information. Unsurprisingly, a systematic review of AD characteristics by region noted considerable phenotypical differences among patients in SEA, East Asia, Iran, and India.28

Disease Severity

Several factors contribute to AD disease severity,34 including objective assessments of inflammation, such as erythema and lichenification (Table), as well as subjective measures of symptoms, such as itch. The severity of AD is exacerbated by the social determinants of health, and a lower socioeconomic status, lower household income, lower parental education level and health, dilapidated housing, and presence of garbage on the street are among factors linked to worse AD disease severity.13,17 Although non-White individuals with AD often are reported to have more severe disease than their White counterparts,35 these types of health determinants may be the most relevant causes of observed differences.

Erythema—Erythema is a feature of inflammation used in the AD severity assessment. Erythema may appear in shades beyond red, including maroon, violaceous, or brown, in patients with darker pigmented skin, which may contribute to diagnosis of AD at a later disease stage.26 Multiple AD severity scoring tools, such as the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis and Eczema Area and Severity Index, include erythema as a measure, which can lead to underestimation of AD severity in SOC populations. After adjusting for erythema score, one study found that Black children with AD had a risk for severe disease that was 6-times higher than White children.36 Dermatological training must adequately teach physicians to recognize erythema across all skin tones.37

Erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis) is rapidly spreading erythema on at least 90% of the total body surface area, often sparing the palms and soles.32 Erythroderma is a potentially life-threatening manifestation of severe AD. Although erythroderma may have many underlying causes, AD has been reported to be the cause in 5% to 24% of cases,38 and compared to studies in Europe, the prevalence of erythroderma was higher in East Asian studies of AD.28

Excoriation and Pruritus—Pruritus is a defining characteristic of AD, and the resulting excoriations often are predominant on physical examination, which is a key part of severity scores. Itch is the most prevalent symptom among patients with AD, and a greater itch severity has been linked to decreased health-related quality of life, increased mental health symptoms, impaired sleep, and decreased daily function.39,40 The burden of itch may be greater in SOC populations. The impact of itch on quality of life among US military veterans was significantly higher in those who identified as non-White (P=.05).41 In another study of US military veterans, African American individuals reported a significantly higher emotional impact from itch (P<.05).42

Lichenification—Lichenification is thickening of the skin due to chronic rubbing and scratching that causes a leathery elevated appearance with exaggerated skin lines.27 Lichenification is included as a factor in common clinical scoring tools, with greater lichenification indicating greater disease severity. Studies from SEA and Africa suggested a higher prevalence of lichenification in AD patients.28 A greater itch burden and thus increased rubbing/scratching in these populations may contribute to some of these findings.42,43

Xerosis—Xerosis (or dry skin) is a common finding in AD that results from increased transepidermal water loss due to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier.44 In a systematic review of AD characteristics by region, xerosis was among the top 5 most reported AD features globally in all regions except SEA.28 Xerosis may be more stigmatizing in SOC populations because of the greater visibility of scaling and dryness on darker skin tones.1

Postinflammatory Dyspigmentation—Postinflammatory pigment alteration may be a consequence of AD lesions, resulting in hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules and patches. Patients with AD with darker skin tones are more likely to develop postinflammatory dyspigmentation.26 A study of AD patients in Nigeria found that 63% displayed postinflammatory dyspigmentation.45 Dyschromia, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, is one of the most common reasons for SOC patients to seek dermatologic care.46 Postinflammatory pigment alteration can cause severe distress in patients, even more so than the cutaneous findings of AD. Although altered skin pigmentation usually returns to normal over weeks to months, skin depigmentation from chronic excoriation may be permanent.26 Appropriately treating hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation in SOC populations can greatly improve quality of life.47

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory disease that presents with many clinical phenotypes. Dermatologists should be trained to recognize the heterogeneous signs of AD present across the diverse skin types in SOC patients. Future research should move away from race-based analyses and focus on the complex interplay of environmental factors, social determinants of health, and skin pigmentation, as well as how these factors drive variations in AD lesional morphology and inflammation.

- Alexis A, Woolery-Lloyd H, Andriessen A, et al. Insights in skin of color patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of skincare in improving outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:462-470. doi:10.36849/jdd.6609

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. The heterogeneity of atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:172-176. doi:10.36849/JDD.6408

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F. Defining skin of color. Cutis. 2002;69:435-437.

- Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: the essential role of cultural broker programs. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/culturalbroker/8_Definitions/2_Definitions.html#:~:text=ethnic%3A%20Of%20or%20relating%20to,or%20cultural%20origin%20or%20background

- Shoo BA, Kashani-Sabet M. Melanoma arising in African-, Asian-, Latino- and Native-American populations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:96-102. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.005

- US Census Bureau. About the topic of race. Revised March 1, 2022. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

- Williams HC. Have you ever seen an Asian/Pacific Islander? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:673-674. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.5.673

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Colloquium paper: human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(Suppl 2):8962-8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871. doi:10.1001/archderm.124.6.869

- Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race—the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:872-878. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2025768

- Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:15-26. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2016.1212660

- Fu T, Keiser E, Linos E, et al. Eczema and sensitization to common allergens in the United States: a multiethnic, population-based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/pde.12237

- Tackett KJ, Jenkins F, Morrell DS, et al. Structural racism and its influence on the severity of atopic dermatitis in African American children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:142-146. doi:10.1111/pde.14058

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Polcari I, Becker L, Stein SL, et al. Filaggrin gene mutations in African Americans with both ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:489-492. doi:10.1111/pde.12355

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000034

- Hua T, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: epidemiology, association with marital status, and atopy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:622-624. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.019

- Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, et al. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251-8.e23. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009

- Ait-Khaled N, Odhiambo J, Pearce N, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Africa: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. Allergy. 2007;62:247-258. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01325.x

- Iking A, Grundmann S, Chatzigeorgakidis E, et al. Prurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:550-557. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04481.x

- Silverberg NB. Typical and atypical clinical appearance of atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:354-359. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.03.007

- Allen HB, Jones NP, Bowen SE. Lichenoid and other clinical presentations of atopic dermatitis in an inner city practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:503-504. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.033

- Nnoruka EN. Current epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:739-744. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02360.x

- Noda S, Suárez-Fariñas M, Ungar B, et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1254-1264. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Girolomoni G, de Bruin-Weller M, Aoki V, et al. Nomenclature and clinical phenotypes of atopic dermatitis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211002979. doi:10.1177/20406223211002979

- Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:390-401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.035

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01740.x

- Hanifin JM. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Dutta A, De A, Das S, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of the usefulness of the minor features of Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:583-590. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_1046_20

- Kulthanan K, Boochangkool K, Tuchinda P, et al. Clinical features of the extrinsic and intrinsic types of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:80-86. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.2.80

- Julián-Gónzalez RE, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Durán-McKinster C, et al. Less common clinical manifestations of atopic dermatitis: prevalence by age. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:580-583. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01739.x

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Evaluating the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:688-689. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.005

- Kim Y, Blomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- McKenzie S, Brown-Korsah JB, Syder NC, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color. part II: differences in clinical presentation and disparities in cutaneous disorders in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1261-1270. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.067

- Cuellar-Barboza A, Ocampo-Candiani J, Herz-Ruelas ME. A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of adult erythroderma [in English, Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:777-790. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2018.05.011

- Lei DK, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, et al. Validation of patient-reported outcomes information system sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:875-882. doi:10.1111/bjd.18920

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340-347. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006

- Carr CW, Veledar E, Chen SC. Factors mediating the impact of chronic pruritus on quality of life. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:613-620. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7696

- Shaw FM, Luk KMH, Chen KH, et al. Racial disparities in the impact of chronic pruritus: a cross-sectional study on quality of life and resource utilization in United States veterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.016

- Oh CC, Li H, Lee W, et al. Biopsychosocial factors associated with prurigo nodularis in endogenous eczema. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:525. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164451

- Vyumvuhore R, Michael-Jubeli R, Verzeaux L, et al. Lipid organization in xerosis: the key of the problem? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:549-554. doi:10.1111/ics.12496

- George AO. Atopic dermatitis in Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:237-239. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb04811.x

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Dupilumab improves atopic dermatitis and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patient with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:776-778. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4937

- Alexis A, Woolery-Lloyd H, Andriessen A, et al. Insights in skin of color patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of skincare in improving outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:462-470. doi:10.36849/jdd.6609

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. The heterogeneity of atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:172-176. doi:10.36849/JDD.6408

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F. Defining skin of color. Cutis. 2002;69:435-437.

- Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: the essential role of cultural broker programs. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/culturalbroker/8_Definitions/2_Definitions.html#:~:text=ethnic%3A%20Of%20or%20relating%20to,or%20cultural%20origin%20or%20background

- Shoo BA, Kashani-Sabet M. Melanoma arising in African-, Asian-, Latino- and Native-American populations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:96-102. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.005

- US Census Bureau. About the topic of race. Revised March 1, 2022. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

- Williams HC. Have you ever seen an Asian/Pacific Islander? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:673-674. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.5.673

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Colloquium paper: human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(Suppl 2):8962-8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871. doi:10.1001/archderm.124.6.869

- Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race—the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:872-878. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2025768

- Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:15-26. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2016.1212660

- Fu T, Keiser E, Linos E, et al. Eczema and sensitization to common allergens in the United States: a multiethnic, population-based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/pde.12237

- Tackett KJ, Jenkins F, Morrell DS, et al. Structural racism and its influence on the severity of atopic dermatitis in African American children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:142-146. doi:10.1111/pde.14058

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Polcari I, Becker L, Stein SL, et al. Filaggrin gene mutations in African Americans with both ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:489-492. doi:10.1111/pde.12355

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25:107-114. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000034

- Hua T, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: epidemiology, association with marital status, and atopy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:622-624. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.019

- Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, et al. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251-8.e23. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009

- Ait-Khaled N, Odhiambo J, Pearce N, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Africa: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. Allergy. 2007;62:247-258. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01325.x

- Iking A, Grundmann S, Chatzigeorgakidis E, et al. Prurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:550-557. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04481.x

- Silverberg NB. Typical and atypical clinical appearance of atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:354-359. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.03.007

- Allen HB, Jones NP, Bowen SE. Lichenoid and other clinical presentations of atopic dermatitis in an inner city practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:503-504. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.033

- Nnoruka EN. Current epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:739-744. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02360.x

- Noda S, Suárez-Fariñas M, Ungar B, et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1254-1264. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Girolomoni G, de Bruin-Weller M, Aoki V, et al. Nomenclature and clinical phenotypes of atopic dermatitis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211002979. doi:10.1177/20406223211002979

- Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:390-401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.035

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01740.x

- Hanifin JM. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Dutta A, De A, Das S, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of the usefulness of the minor features of Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:583-590. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_1046_20

- Kulthanan K, Boochangkool K, Tuchinda P, et al. Clinical features of the extrinsic and intrinsic types of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:80-86. doi:10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.2.80

- Julián-Gónzalez RE, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Durán-McKinster C, et al. Less common clinical manifestations of atopic dermatitis: prevalence by age. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:580-583. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01739.x

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Evaluating the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:688-689. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.005

- Kim Y, Blomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- McKenzie S, Brown-Korsah JB, Syder NC, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color. part II: differences in clinical presentation and disparities in cutaneous disorders in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1261-1270. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.067

- Cuellar-Barboza A, Ocampo-Candiani J, Herz-Ruelas ME. A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of adult erythroderma [in English, Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:777-790. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2018.05.011

- Lei DK, Yousaf M, Janmohamed SR, et al. Validation of patient-reported outcomes information system sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:875-882. doi:10.1111/bjd.18920

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340-347. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006

- Carr CW, Veledar E, Chen SC. Factors mediating the impact of chronic pruritus on quality of life. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:613-620. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7696

- Shaw FM, Luk KMH, Chen KH, et al. Racial disparities in the impact of chronic pruritus: a cross-sectional study on quality of life and resource utilization in United States veterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.016

- Oh CC, Li H, Lee W, et al. Biopsychosocial factors associated with prurigo nodularis in endogenous eczema. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:525. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164451

- Vyumvuhore R, Michael-Jubeli R, Verzeaux L, et al. Lipid organization in xerosis: the key of the problem? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:549-554. doi:10.1111/ics.12496

- George AO. Atopic dermatitis in Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:237-239. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb04811.x

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Dupilumab improves atopic dermatitis and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patient with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:776-778. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4937

Practice Points

- Social determinants of health play a central role in observed racial and ethnic differences in studies of atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients with skin of color.

- Prurigo nodules, lichenoid papules, perifollicular papules, nummular lesions, and psoriasiform lesions are among the diverse lesion morphologies seen with AD.

- Key signs of cutaneous inflammation and lesional severity, including erythema, may present differently in darker skin tones and contribute to underestimation of severity.

- Postinflammatory dyspigmentation is common among patients with skin of color, and treatment can substantially improve quality of life.

Predictors of prescription opioid overdose

A Canadian systematic review of 28 observational studies has identified 10 strong predictors of fatal and nonfatal prescription opioid overdose.

Published in CMAJ, the analysis found the risk of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose was notably tied to such factors as high-dose and fentanyl prescriptions, multiple opioid prescribers or pharmacies, and several mental health issues. High-certainty evidence from 14 studies involving more than a million patients showed a linear dose-response relationship with opioid overdose.

“Our findings suggest that awareness of, and attention to, several patient and prescription characteristics may help reduce the risk of opioid overdose among people living with chronic pain,” wrote a research team led by Li Wang, PhD, a researcher at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Pain Research and Care and the department of anesthesia at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Predictors of fatal and nonfatal overdose

Reporting on studies of 103 possible predictors in a pooled cohort of almost 24 million patients, the review found moderate- to high-certainty evidence for large relative associations with the following 10 criteria:

- A history of overdose (odds ratio, 5.85; 95% confidence interval, 3.78-9.04).

- A higher opioid dosage (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.08-3.18 per 90-mg increment).

- Three or more prescribers (OR, 4.68; 95% CI, 3.57-6.12).

- Four or more dispensing pharmacies (OR, 4.92; 95% CI, 4.35-5.57).

- Prescription for fentanyl (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.30-3.41).

- Current substance use disorder (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 2.09-3.27).

- Any mental health diagnosis (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.73-2.61).

- Depression (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.57-314).

- Bipolar disorder (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.77-2.41).

- Pancreatitis (OR, 2.00; 95% CI,1.52-2.64).

Absolute risks in patients with the predictor ranged from 2 to 6 per 1,000 for fatal overdose and 4 to 12 per 1,000 for nonfatal overdose.

The authors noted that chronic pain affects 20% of the world’s population worldwide, and a 2021 meta-analysis of 60 observational studies revealed that opioids are prescribed for 27% of adults living with chronic pain, with a higher prevalence of prescribing in North America than in Europe.

International review

A total of 28 observational studies comprising 23,963,716 patients (52% female) with mean age of 52 years were enrolled. All used administrative databases. Twenty-four studies were conducted in the United States, three in Canada, and one in the United Kingdom. Twenty-one studies included only patients with noncancer chronic pain, while seven included patients with either cancer-related or noncancer chronic pain. Twenty-two studies accepted patients with previous or current substance use disorder and three excluded patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Twenty-three studies included patients with comorbid mental illness and five exclusively recruited veterans.

The median sample size was 43,885. As a limitation, 25 studies (89%) were at high risk of bias for at least one criterion, the authors acknowledged. Moderate-certainty evidence showed the pooled prevalence of fatal opioid overdose after prescription for chronic pain was 1.3 per 1,000 (95% CI, 0.6-2.3 per 1,000) for fatal overdose and 3.2 per 1,000 (95% CI, 2.0-4.7 per 1,000) for nonfatal overdose.

“Awareness of these predictors may facilitate shared decision-making regarding prescribing opioids for chronic pain and may inform harm-reduction strategies,” Dr. Wang and associates wrote.

This study was supported by a grant from Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program. Coauthor Dr. Corey Hayes was supported by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Dr. Jason Busse is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. David Juurlink has received travel support for presentations from the CIHR, Stanford University, and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

A Canadian systematic review of 28 observational studies has identified 10 strong predictors of fatal and nonfatal prescription opioid overdose.

Published in CMAJ, the analysis found the risk of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose was notably tied to such factors as high-dose and fentanyl prescriptions, multiple opioid prescribers or pharmacies, and several mental health issues. High-certainty evidence from 14 studies involving more than a million patients showed a linear dose-response relationship with opioid overdose.

“Our findings suggest that awareness of, and attention to, several patient and prescription characteristics may help reduce the risk of opioid overdose among people living with chronic pain,” wrote a research team led by Li Wang, PhD, a researcher at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Pain Research and Care and the department of anesthesia at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Predictors of fatal and nonfatal overdose

Reporting on studies of 103 possible predictors in a pooled cohort of almost 24 million patients, the review found moderate- to high-certainty evidence for large relative associations with the following 10 criteria:

- A history of overdose (odds ratio, 5.85; 95% confidence interval, 3.78-9.04).

- A higher opioid dosage (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.08-3.18 per 90-mg increment).

- Three or more prescribers (OR, 4.68; 95% CI, 3.57-6.12).

- Four or more dispensing pharmacies (OR, 4.92; 95% CI, 4.35-5.57).

- Prescription for fentanyl (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.30-3.41).

- Current substance use disorder (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 2.09-3.27).

- Any mental health diagnosis (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.73-2.61).

- Depression (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.57-314).

- Bipolar disorder (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.77-2.41).

- Pancreatitis (OR, 2.00; 95% CI,1.52-2.64).

Absolute risks in patients with the predictor ranged from 2 to 6 per 1,000 for fatal overdose and 4 to 12 per 1,000 for nonfatal overdose.

The authors noted that chronic pain affects 20% of the world’s population worldwide, and a 2021 meta-analysis of 60 observational studies revealed that opioids are prescribed for 27% of adults living with chronic pain, with a higher prevalence of prescribing in North America than in Europe.

International review

A total of 28 observational studies comprising 23,963,716 patients (52% female) with mean age of 52 years were enrolled. All used administrative databases. Twenty-four studies were conducted in the United States, three in Canada, and one in the United Kingdom. Twenty-one studies included only patients with noncancer chronic pain, while seven included patients with either cancer-related or noncancer chronic pain. Twenty-two studies accepted patients with previous or current substance use disorder and three excluded patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Twenty-three studies included patients with comorbid mental illness and five exclusively recruited veterans.

The median sample size was 43,885. As a limitation, 25 studies (89%) were at high risk of bias for at least one criterion, the authors acknowledged. Moderate-certainty evidence showed the pooled prevalence of fatal opioid overdose after prescription for chronic pain was 1.3 per 1,000 (95% CI, 0.6-2.3 per 1,000) for fatal overdose and 3.2 per 1,000 (95% CI, 2.0-4.7 per 1,000) for nonfatal overdose.

“Awareness of these predictors may facilitate shared decision-making regarding prescribing opioids for chronic pain and may inform harm-reduction strategies,” Dr. Wang and associates wrote.

This study was supported by a grant from Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program. Coauthor Dr. Corey Hayes was supported by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development and the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Dr. Jason Busse is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. David Juurlink has received travel support for presentations from the CIHR, Stanford University, and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

A Canadian systematic review of 28 observational studies has identified 10 strong predictors of fatal and nonfatal prescription opioid overdose.

Published in CMAJ, the analysis found the risk of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose was notably tied to such factors as high-dose and fentanyl prescriptions, multiple opioid prescribers or pharmacies, and several mental health issues. High-certainty evidence from 14 studies involving more than a million patients showed a linear dose-response relationship with opioid overdose.