User login

Formaldehyde probably doesn’t cause leukemia, team says

There is little or no evidence to suggest that exposure to formaldehyde causes leukemia, according to a group of researchers.

The team reanalyzed data from a study published in 2010 that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde exposure and myeloid leukemia.

They also reviewed other recent studies investigating the health effects of formaldehyde.

“The weight of scientific evidence does not support a causal association between formaldehyde and leukemia,” said Kenneth A. Mundt, PhD, of Ramboll Environ, a consulting firm focused on environmental, health, and social issues.

Dr Mundt and his colleagues detailed the evidence in the Journal of Critical Reviews in Toxicology.

The team’s research was supported by the Foundation for Chemistry Research and Initiatives (formerly the Research Foundation for Health and Environmental Effects), an organization established by the American Chemistry Council (an industry trade association for American chemical companies).

The study that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde and myeloid leukemia, particularly acute myeloid leukemia (AML), was published in January 2010 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

In this study, Luoping Zhang, PhD, of the University of California at Berkeley, and her colleagues compared 2 groups of workers in China—43 workers with occupational exposure to formaldehyde and 51 without such exposure.

The researchers looked at complete blood counts and peripheral stem/progenitor cell colony formation. They also cultured myeloid progenitor cells, aiming to determine the level of leukemia-specific chromosome changes, including monosomy 7 and trisomy 8, in these cells.

The team found that workers exposed to formaldehyde had significantly lower peripheral blood cell counts and significantly elevated leukemia-specific chromosome changes in myeloid progenitor cells.

Dr Zhang and her colleagues said these results suggest “formaldehyde exposure can have an adverse effect on the hematopoietic system and that leukemia induction by formaldehyde is biologically plausible.”

Dr Mundt and his colleagues reanalyzed raw data from this study, including previously unavailable data on individual workers’ exposure to formaldehyde. Those data were recently released by the National Cancer Institute, which co-funded Dr Zhang’s study.

The reanalysis indicated that the observed differences in blood cell counts were not dependent on formaldehyde exposure. And the researchers found no association between the individual average formaldehyde exposure estimates and chromosomal abnormalities.

Dr Mundt’s team also reviewed several other publications on the health effects of formaldehyde, and they said the data, as a whole, provide “little if any evidence of a causal association between formaldehyde exposure and AML.” ![]()

There is little or no evidence to suggest that exposure to formaldehyde causes leukemia, according to a group of researchers.

The team reanalyzed data from a study published in 2010 that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde exposure and myeloid leukemia.

They also reviewed other recent studies investigating the health effects of formaldehyde.

“The weight of scientific evidence does not support a causal association between formaldehyde and leukemia,” said Kenneth A. Mundt, PhD, of Ramboll Environ, a consulting firm focused on environmental, health, and social issues.

Dr Mundt and his colleagues detailed the evidence in the Journal of Critical Reviews in Toxicology.

The team’s research was supported by the Foundation for Chemistry Research and Initiatives (formerly the Research Foundation for Health and Environmental Effects), an organization established by the American Chemistry Council (an industry trade association for American chemical companies).

The study that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde and myeloid leukemia, particularly acute myeloid leukemia (AML), was published in January 2010 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

In this study, Luoping Zhang, PhD, of the University of California at Berkeley, and her colleagues compared 2 groups of workers in China—43 workers with occupational exposure to formaldehyde and 51 without such exposure.

The researchers looked at complete blood counts and peripheral stem/progenitor cell colony formation. They also cultured myeloid progenitor cells, aiming to determine the level of leukemia-specific chromosome changes, including monosomy 7 and trisomy 8, in these cells.

The team found that workers exposed to formaldehyde had significantly lower peripheral blood cell counts and significantly elevated leukemia-specific chromosome changes in myeloid progenitor cells.

Dr Zhang and her colleagues said these results suggest “formaldehyde exposure can have an adverse effect on the hematopoietic system and that leukemia induction by formaldehyde is biologically plausible.”

Dr Mundt and his colleagues reanalyzed raw data from this study, including previously unavailable data on individual workers’ exposure to formaldehyde. Those data were recently released by the National Cancer Institute, which co-funded Dr Zhang’s study.

The reanalysis indicated that the observed differences in blood cell counts were not dependent on formaldehyde exposure. And the researchers found no association between the individual average formaldehyde exposure estimates and chromosomal abnormalities.

Dr Mundt’s team also reviewed several other publications on the health effects of formaldehyde, and they said the data, as a whole, provide “little if any evidence of a causal association between formaldehyde exposure and AML.” ![]()

There is little or no evidence to suggest that exposure to formaldehyde causes leukemia, according to a group of researchers.

The team reanalyzed data from a study published in 2010 that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde exposure and myeloid leukemia.

They also reviewed other recent studies investigating the health effects of formaldehyde.

“The weight of scientific evidence does not support a causal association between formaldehyde and leukemia,” said Kenneth A. Mundt, PhD, of Ramboll Environ, a consulting firm focused on environmental, health, and social issues.

Dr Mundt and his colleagues detailed the evidence in the Journal of Critical Reviews in Toxicology.

The team’s research was supported by the Foundation for Chemistry Research and Initiatives (formerly the Research Foundation for Health and Environmental Effects), an organization established by the American Chemistry Council (an industry trade association for American chemical companies).

The study that suggested a possible link between formaldehyde and myeloid leukemia, particularly acute myeloid leukemia (AML), was published in January 2010 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

In this study, Luoping Zhang, PhD, of the University of California at Berkeley, and her colleagues compared 2 groups of workers in China—43 workers with occupational exposure to formaldehyde and 51 without such exposure.

The researchers looked at complete blood counts and peripheral stem/progenitor cell colony formation. They also cultured myeloid progenitor cells, aiming to determine the level of leukemia-specific chromosome changes, including monosomy 7 and trisomy 8, in these cells.

The team found that workers exposed to formaldehyde had significantly lower peripheral blood cell counts and significantly elevated leukemia-specific chromosome changes in myeloid progenitor cells.

Dr Zhang and her colleagues said these results suggest “formaldehyde exposure can have an adverse effect on the hematopoietic system and that leukemia induction by formaldehyde is biologically plausible.”

Dr Mundt and his colleagues reanalyzed raw data from this study, including previously unavailable data on individual workers’ exposure to formaldehyde. Those data were recently released by the National Cancer Institute, which co-funded Dr Zhang’s study.

The reanalysis indicated that the observed differences in blood cell counts were not dependent on formaldehyde exposure. And the researchers found no association between the individual average formaldehyde exposure estimates and chromosomal abnormalities.

Dr Mundt’s team also reviewed several other publications on the health effects of formaldehyde, and they said the data, as a whole, provide “little if any evidence of a causal association between formaldehyde exposure and AML.” ![]()

Company withdraws MAA for vosaroxin in AML

Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. is withdrawing its European Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) for the anticancer quinolone derivative vosaroxin.

The MAA was for vosaroxin as a treatment for relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients age 60 years and older.

Along with the MAA withdrawal, Sunesis has decided to scale back its investment in vosaroxin.

However, the company said it will continue developing the drug.

These decisions were made after Sunesis learned the European Medicine Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) was unlikely to recommend approval for vosaroxin.

“We are disappointed to not achieve approval for vosaroxin’s MAA, given its reported efficacy in a patient population with such poor outcomes,” said Daniel Swisher, president and chief executive officer of Sunesis.

“Although we did not receive a definitive CHMP opinion, we believed that a positive opinion was unlikely. Following our appearances before the committee’s Scientific Advisory Group on Oncology and CHMP, we carefully considered feedback from our rapporteurs and input from retained regulatory experts to make our decision to notify EMA to withdraw vosaroxin’s MAA, as our assessment concluded it was unlikely we could achieve a majority vote of CHMP members at this time or upon an immediate re-examination for our proposed indication based on VALOR data from a subgroup of a single pivotal trial that had missed reaching full statistical significance in its primary analysis.”

“In light of this, we are significantly reducing our investment in the AML program and shifting an increasing portion of resources to our kinase inhibitor pipeline . . . . We expect to continue to advance the development of vosaroxin through a modest investment in investigator-sponsored group trials and will carefully assess business development alternatives to support the conduct of another pivotal trial to achieve future regulatory approval of vosaroxin. We expect that our current cash resources are sufficient to fund the company beyond Q1 2018.” ![]()

Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. is withdrawing its European Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) for the anticancer quinolone derivative vosaroxin.

The MAA was for vosaroxin as a treatment for relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients age 60 years and older.

Along with the MAA withdrawal, Sunesis has decided to scale back its investment in vosaroxin.

However, the company said it will continue developing the drug.

These decisions were made after Sunesis learned the European Medicine Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) was unlikely to recommend approval for vosaroxin.

“We are disappointed to not achieve approval for vosaroxin’s MAA, given its reported efficacy in a patient population with such poor outcomes,” said Daniel Swisher, president and chief executive officer of Sunesis.

“Although we did not receive a definitive CHMP opinion, we believed that a positive opinion was unlikely. Following our appearances before the committee’s Scientific Advisory Group on Oncology and CHMP, we carefully considered feedback from our rapporteurs and input from retained regulatory experts to make our decision to notify EMA to withdraw vosaroxin’s MAA, as our assessment concluded it was unlikely we could achieve a majority vote of CHMP members at this time or upon an immediate re-examination for our proposed indication based on VALOR data from a subgroup of a single pivotal trial that had missed reaching full statistical significance in its primary analysis.”

“In light of this, we are significantly reducing our investment in the AML program and shifting an increasing portion of resources to our kinase inhibitor pipeline . . . . We expect to continue to advance the development of vosaroxin through a modest investment in investigator-sponsored group trials and will carefully assess business development alternatives to support the conduct of another pivotal trial to achieve future regulatory approval of vosaroxin. We expect that our current cash resources are sufficient to fund the company beyond Q1 2018.” ![]()

Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. is withdrawing its European Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) for the anticancer quinolone derivative vosaroxin.

The MAA was for vosaroxin as a treatment for relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients age 60 years and older.

Along with the MAA withdrawal, Sunesis has decided to scale back its investment in vosaroxin.

However, the company said it will continue developing the drug.

These decisions were made after Sunesis learned the European Medicine Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) was unlikely to recommend approval for vosaroxin.

“We are disappointed to not achieve approval for vosaroxin’s MAA, given its reported efficacy in a patient population with such poor outcomes,” said Daniel Swisher, president and chief executive officer of Sunesis.

“Although we did not receive a definitive CHMP opinion, we believed that a positive opinion was unlikely. Following our appearances before the committee’s Scientific Advisory Group on Oncology and CHMP, we carefully considered feedback from our rapporteurs and input from retained regulatory experts to make our decision to notify EMA to withdraw vosaroxin’s MAA, as our assessment concluded it was unlikely we could achieve a majority vote of CHMP members at this time or upon an immediate re-examination for our proposed indication based on VALOR data from a subgroup of a single pivotal trial that had missed reaching full statistical significance in its primary analysis.”

“In light of this, we are significantly reducing our investment in the AML program and shifting an increasing portion of resources to our kinase inhibitor pipeline . . . . We expect to continue to advance the development of vosaroxin through a modest investment in investigator-sponsored group trials and will carefully assess business development alternatives to support the conduct of another pivotal trial to achieve future regulatory approval of vosaroxin. We expect that our current cash resources are sufficient to fund the company beyond Q1 2018.” ![]()

Heavily promoted drugs provide less ‘health value,’ study suggests

Drugs that are promoted most heavily in the US are less likely than the top-selling drugs and the top-prescribed drugs to provide “health value,” according to researchers.

The top-promoted drugs were less likely than either or both of the other drug types to demonstrate safety and effectiveness, be affordable, represent a genuine advance in treating a disease, be included on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of essential medicines, or be recommended as a first-line treatment.

Among the top-promoted drugs were 4 anticoagulants—Eliquis (apixaban), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Brilinta (ticagrelor), and Pradaxa (dabigatran).

Tyler Greenway and Joseph S. Ross, MD, both of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, conducted this research and reported their findings in The BMJ.

The researchers set out to assess the “health value” of the drugs most aggressively promoted to physicians to better understand the implications of pharmaceutical promotion for patient care.

The team identified the 25 medicinal products associated with the largest total payments to physicians and teaching hospitals from August 2013 to December 2014.

This included all direct and indirect payments, such as speaker fees for education lectures, consulting fees, and honoraria, as well as payments in kind, such as the value of food and gifts. However, research payments, royalties, and licensing fees were excluded, as these are typically not promotional.

The researchers also determined the 25 best-selling medicinal products by 2014 US sales and the 25 most-prescribed drugs in the US during 2013.

One of the 25 top-promoted products was excluded because it was used to test for adrenocortical function. And 1 of the 25 top-selling products was a pneumococcal vaccine, which was also excluded.

Four of the 24 top-promoted drugs (17%) were also among the top-selling drugs—adalimumab, glatiramer, aripiprazole, and budesonide-formoterol. But none of the top-promoted drugs were among the top-prescribed drugs.

Among the top-selling drugs were several used in the field of hematology—Rituxan (rituximab), Neulasta (pegfilgrastim), Neupogen (filgrastim), Revlimid (lenalidomide), and Gleevec (imatinib mesylate).

Results

The researchers estimated the drugs’ value to society using 5 proxy measures:

- Innovation—drugs that were first-in-class or provided a “meaningful advance” over existing treatments

- Effectiveness and safety—assessed using the ratings systems of the French drug industry watchdog Prescrire International

- Generic availability—a measure of affordability

- Clinical value—inclusion on the WHO list of essential medicines in 2015

- First-line status—being recommended as a first-line therapy.

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered innovative than the top-selling drugs (33% vs 72%, relative risk [RR]=0.46, P=0.01). However, the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 52%, RR=0.64, P=0.25).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered possibly helpful or advantageous according to Prescrire ratings than the top-prescribed drugs (19% vs 76%, RR=0.25, P<0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-selling drugs (19% vs 44%, RR=0.43, P=0.11).

Generic equivalents were available for 62% of the top-promoted drugs, 32% of the top-selling drugs (RR=1.95, P=0.05), and 100% of the top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.63, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely than either of the other drug types to be on the WHO essential medicines list. One of the top-promoted drugs was on the list, compared to 9 top-selling drugs (RR=0.12, P=0.01) and 14 top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.07, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be recommended as first-line treatments than the top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 80%, RR=0.42, P=0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-selling drugs (33% vs 60%, RR=0.56, P=0.09).

The researchers said these results raise concerns about the purpose of pharmaceutical promotion and its influence on patient care. They believe efforts are needed to better evaluate the value of drugs, ensuring this information is readily available at the point of care so it can inform clinical decision-making and promote the use of higher-value medicines.

The researchers also suggested that clinicians consider taking steps to limit their exposure to industry promotion and consider engaging with non-commercial educational outreach programs that provide evidence-based recommendations about medication choices. ![]()

Drugs that are promoted most heavily in the US are less likely than the top-selling drugs and the top-prescribed drugs to provide “health value,” according to researchers.

The top-promoted drugs were less likely than either or both of the other drug types to demonstrate safety and effectiveness, be affordable, represent a genuine advance in treating a disease, be included on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of essential medicines, or be recommended as a first-line treatment.

Among the top-promoted drugs were 4 anticoagulants—Eliquis (apixaban), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Brilinta (ticagrelor), and Pradaxa (dabigatran).

Tyler Greenway and Joseph S. Ross, MD, both of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, conducted this research and reported their findings in The BMJ.

The researchers set out to assess the “health value” of the drugs most aggressively promoted to physicians to better understand the implications of pharmaceutical promotion for patient care.

The team identified the 25 medicinal products associated with the largest total payments to physicians and teaching hospitals from August 2013 to December 2014.

This included all direct and indirect payments, such as speaker fees for education lectures, consulting fees, and honoraria, as well as payments in kind, such as the value of food and gifts. However, research payments, royalties, and licensing fees were excluded, as these are typically not promotional.

The researchers also determined the 25 best-selling medicinal products by 2014 US sales and the 25 most-prescribed drugs in the US during 2013.

One of the 25 top-promoted products was excluded because it was used to test for adrenocortical function. And 1 of the 25 top-selling products was a pneumococcal vaccine, which was also excluded.

Four of the 24 top-promoted drugs (17%) were also among the top-selling drugs—adalimumab, glatiramer, aripiprazole, and budesonide-formoterol. But none of the top-promoted drugs were among the top-prescribed drugs.

Among the top-selling drugs were several used in the field of hematology—Rituxan (rituximab), Neulasta (pegfilgrastim), Neupogen (filgrastim), Revlimid (lenalidomide), and Gleevec (imatinib mesylate).

Results

The researchers estimated the drugs’ value to society using 5 proxy measures:

- Innovation—drugs that were first-in-class or provided a “meaningful advance” over existing treatments

- Effectiveness and safety—assessed using the ratings systems of the French drug industry watchdog Prescrire International

- Generic availability—a measure of affordability

- Clinical value—inclusion on the WHO list of essential medicines in 2015

- First-line status—being recommended as a first-line therapy.

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered innovative than the top-selling drugs (33% vs 72%, relative risk [RR]=0.46, P=0.01). However, the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 52%, RR=0.64, P=0.25).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered possibly helpful or advantageous according to Prescrire ratings than the top-prescribed drugs (19% vs 76%, RR=0.25, P<0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-selling drugs (19% vs 44%, RR=0.43, P=0.11).

Generic equivalents were available for 62% of the top-promoted drugs, 32% of the top-selling drugs (RR=1.95, P=0.05), and 100% of the top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.63, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely than either of the other drug types to be on the WHO essential medicines list. One of the top-promoted drugs was on the list, compared to 9 top-selling drugs (RR=0.12, P=0.01) and 14 top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.07, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be recommended as first-line treatments than the top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 80%, RR=0.42, P=0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-selling drugs (33% vs 60%, RR=0.56, P=0.09).

The researchers said these results raise concerns about the purpose of pharmaceutical promotion and its influence on patient care. They believe efforts are needed to better evaluate the value of drugs, ensuring this information is readily available at the point of care so it can inform clinical decision-making and promote the use of higher-value medicines.

The researchers also suggested that clinicians consider taking steps to limit their exposure to industry promotion and consider engaging with non-commercial educational outreach programs that provide evidence-based recommendations about medication choices. ![]()

Drugs that are promoted most heavily in the US are less likely than the top-selling drugs and the top-prescribed drugs to provide “health value,” according to researchers.

The top-promoted drugs were less likely than either or both of the other drug types to demonstrate safety and effectiveness, be affordable, represent a genuine advance in treating a disease, be included on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of essential medicines, or be recommended as a first-line treatment.

Among the top-promoted drugs were 4 anticoagulants—Eliquis (apixaban), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Brilinta (ticagrelor), and Pradaxa (dabigatran).

Tyler Greenway and Joseph S. Ross, MD, both of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, conducted this research and reported their findings in The BMJ.

The researchers set out to assess the “health value” of the drugs most aggressively promoted to physicians to better understand the implications of pharmaceutical promotion for patient care.

The team identified the 25 medicinal products associated with the largest total payments to physicians and teaching hospitals from August 2013 to December 2014.

This included all direct and indirect payments, such as speaker fees for education lectures, consulting fees, and honoraria, as well as payments in kind, such as the value of food and gifts. However, research payments, royalties, and licensing fees were excluded, as these are typically not promotional.

The researchers also determined the 25 best-selling medicinal products by 2014 US sales and the 25 most-prescribed drugs in the US during 2013.

One of the 25 top-promoted products was excluded because it was used to test for adrenocortical function. And 1 of the 25 top-selling products was a pneumococcal vaccine, which was also excluded.

Four of the 24 top-promoted drugs (17%) were also among the top-selling drugs—adalimumab, glatiramer, aripiprazole, and budesonide-formoterol. But none of the top-promoted drugs were among the top-prescribed drugs.

Among the top-selling drugs were several used in the field of hematology—Rituxan (rituximab), Neulasta (pegfilgrastim), Neupogen (filgrastim), Revlimid (lenalidomide), and Gleevec (imatinib mesylate).

Results

The researchers estimated the drugs’ value to society using 5 proxy measures:

- Innovation—drugs that were first-in-class or provided a “meaningful advance” over existing treatments

- Effectiveness and safety—assessed using the ratings systems of the French drug industry watchdog Prescrire International

- Generic availability—a measure of affordability

- Clinical value—inclusion on the WHO list of essential medicines in 2015

- First-line status—being recommended as a first-line therapy.

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered innovative than the top-selling drugs (33% vs 72%, relative risk [RR]=0.46, P=0.01). However, the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 52%, RR=0.64, P=0.25).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be considered possibly helpful or advantageous according to Prescrire ratings than the top-prescribed drugs (19% vs 76%, RR=0.25, P<0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-promoted and top-selling drugs (19% vs 44%, RR=0.43, P=0.11).

Generic equivalents were available for 62% of the top-promoted drugs, 32% of the top-selling drugs (RR=1.95, P=0.05), and 100% of the top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.63, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely than either of the other drug types to be on the WHO essential medicines list. One of the top-promoted drugs was on the list, compared to 9 top-selling drugs (RR=0.12, P=0.01) and 14 top-prescribed drugs (RR=0.07, P<0.001).

The top-promoted drugs were significantly less likely to be recommended as first-line treatments than the top-prescribed drugs (33% vs 80%, RR=0.42, P=0.001). But the difference was not significant for the top-selling drugs (33% vs 60%, RR=0.56, P=0.09).

The researchers said these results raise concerns about the purpose of pharmaceutical promotion and its influence on patient care. They believe efforts are needed to better evaluate the value of drugs, ensuring this information is readily available at the point of care so it can inform clinical decision-making and promote the use of higher-value medicines.

The researchers also suggested that clinicians consider taking steps to limit their exposure to industry promotion and consider engaging with non-commercial educational outreach programs that provide evidence-based recommendations about medication choices. ![]()

Demystifying interstitial cystitis

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

The broad picture of interstitial cystitis

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.

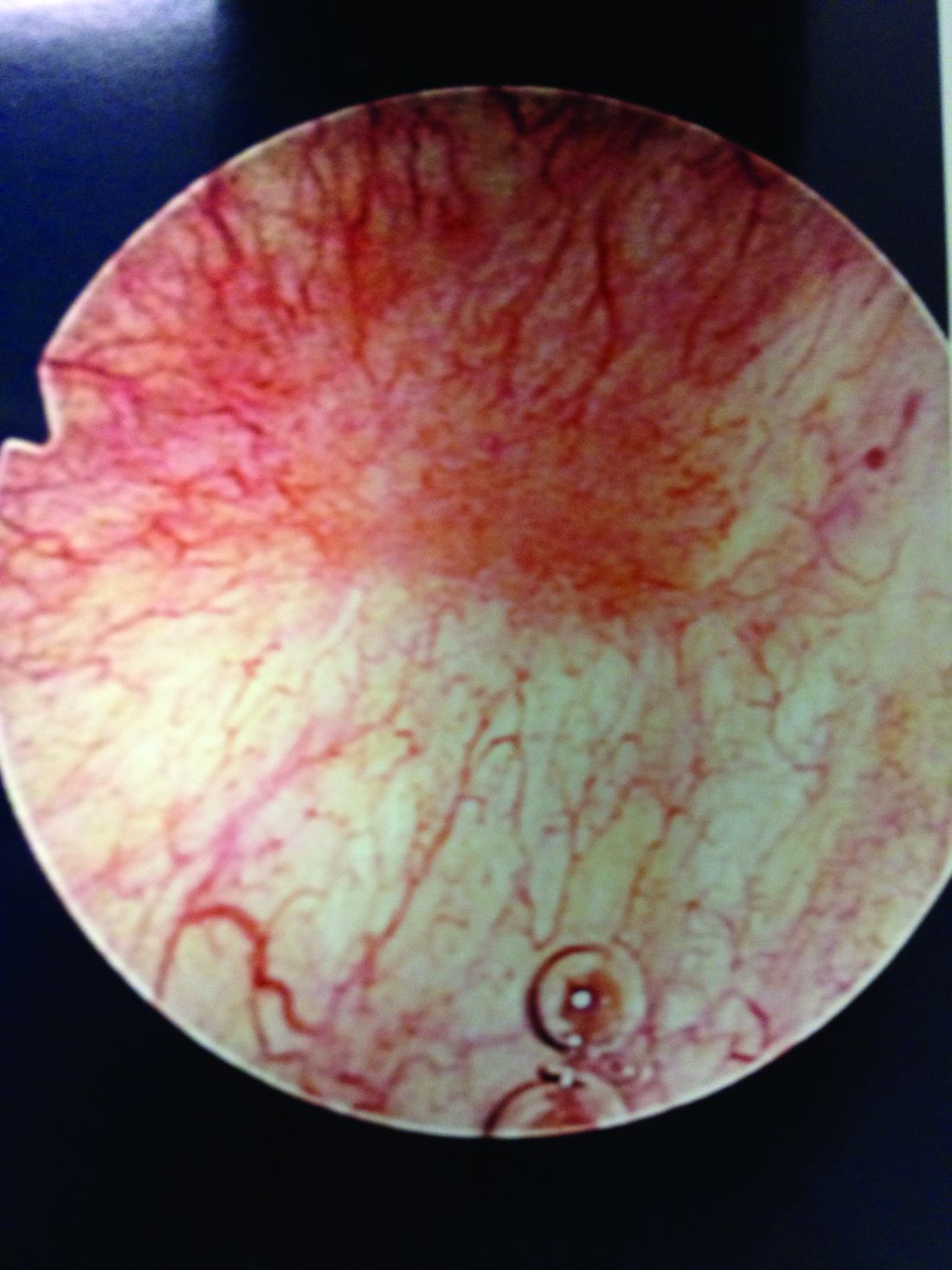

Hunner’s lesions

Patients with Hunner’s lesions have a rapid onset of symptoms, typically are older, and have a visible lesion in their bladder that almost always is on the dome or lateral walls. The lesion is often erythematous with central vascularity and mucosal sloughing.

The bladder is a storage organ and urine is toxic. The exposed ulcer results in severe pain with bladder filling and also pain at the end of voiding as the bladder collapses, causing ulcerated tissue to come into contact with other sections of the bladder wall and sending a “jolt” of pain through the pelvis.

If the initial cystoscopy demonstrates inflammatory-appearing lesions or ulcerations suggestive of Hunner’s lesions, I will still do a hydrodistension. By stretching the bladder, the lesions typically expand, crack, and bleed. This helps define the entire diseased area and shows what areas of the bladder need to be cauterized to seal the ulcers and destroy the exposed nerve endings. If this is a new diagnosis, the lesion should be biopsied after the hydrodistension to rule out carcinoma.

Hunner’s lesions can lead to rapid disease progression due to chronic inflammation and subsequent collagen deposition and scarring. Even on initial diagnosis of Hunner’s lesions, a capacity of 350 cc or less (compared with 1,100 cc in a normal bladder) on hydrodistension under anesthesia is not uncommon. This markedly reduced bladder capacity may lead to end-stage bladder impacting the kidneys and requiring a urinary diversion.

Eradicating the ulcers with resection or cautery often results in marked and immediate improvement in bladder pain, albeit not long-lasting. I will typically place a resectoscope and use a roller ball at 25 watts of current. The entire ulcerated areas are cauterized by rapidly rolling the ball over the area of inflammation and avoiding a deep thermal burn. The goal is to seal the ulcer and destroy the exposed nerve endings so that urine can no longer act as an irritant. Recurrence in 6 months to 1 year is common and retreatment is almost always necessary. We have demonstrated, however, that recurrent cautery of ulcers does not lead to smaller anesthetic bladder capacities (Urology. 2015 Jan;85[1]:74-8).

Low-dose cyclosporine can be very effective at reducing Hunner’s lesion recurrence and improving storage symptoms (Exp Ther Med. 2016 Jul;12[1]:445-50). I use 100 mg twice a day for a month and then 1 pill a day thereafter. This is a relatively low dose, but hypertension can be a side effect and blood pressure should be monitored along with routine labs.

The broader picture

Hunner’s lesion IC is pretty straightforward and clearly a bladder disease. However, in recent years the term IC/BPS has been broadly used to describe women who have symptoms of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, and frequency, but no true bladder pathology to explain their symptoms. One problem: There is no definitive diagnostic test or evidence-based diagnostic process for IC/BPS. In fact, the diagnosis section of the American Urological Association guideline on diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS, last updated in 2015, is almost entirely consensus-based (J Urol. 2015 May;193[5]:1545-53). It largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

As the AUA guidelines state, a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory assessment are all important for documenting symptoms and signs and ruling out significant causes of the symptoms. I frequently see patients who have been diagnosed with IC who have frequency and urgency but no pain (in which case overactive bladder should be considered) or who have pelvic pain but no bladder symptoms, again likely not IC. Pain that worsens with bladder filling and improves after bladder emptying is typical of IC/BPS. This finding in the absence of other confusing symptoms supports the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

It has become too easy for the average clinician to apply a label of IC/BPS to a patient complaining of pelvic pain; this often results in the patient undergoing invasive and nonhelpful therapies such as cystoscopy, hydrodistension, urodynamics, bladder instillations, and other bladder-directed therapies.

More than 20 years of research supported by the National Institutes of Health and industry have failed to show that bladder-directed therapy is superior to placebo. This fact suggests that the bladder may be an innocent bystander in a larger pelvic process. As clinicians, we must be willing to look beyond the bladder and examine for pelvic floor issues and other causes of patient’s symptoms and not be too quick to begin bladder-focused treatments.

A number of disease processes – such as recurrent urinary tract infection, urethral diverticulum, endometriosis, and pudendal neuropathy – can mimic the symptoms of IC/BPS. The most common missed diagnosis in the IC patient is pelvic floor dysfunction that results in a hypertonic contracted state of the levator muscles – a chronic spasm, in essence – that in turn leads to decreased muscle function, increased myofascial pain, and myofascial trigger points (Curr Urol Rep. 2006 Nov;7[6]:450-5).

We and others have reported that up to 85% of patients labeled with IC/BPS have been found on examination to have pelvic floor dysfunction or a diffuse pelvic floor hypersensitivity. The pelvic floor is important in maintaining healthy bladder, bowel, and sexual function. If the pelvic floor is in spasm, this can result in urinary frequency, hesitancy, and pelvic pain.

Many of these patients with contracted pelvic floor muscles report pain with sexual intercourse – often so severe as to cause abstention. In fact, when patients answer no to the question of whether they have pain with intercourse, I know it is unlikely that they have significant pelvic floor dysfunction. This is a key question for history taking.

Other key questions concern the impact of stress on symptoms and a history of any type of abuse. In a study we conducted about 10 years ago, we found that among 76 women who were diagnosed with IC and subsequently evaluated in our clinic, almost half (49%) reported abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual). The vast majority (85%) had levator pain (J Urol. 2007 Sep;178[3 Pt 1]:891-5).

Other types of stress – from past surgeries to traumatic life events – may similarly serve as triggers or precursors to pelvic floor dysfunction in some women. I often tell patients that people put stress in different areas of their bodies. While some get tension headaches or low-back aches, others get pelvic pain from contracting and guarding the levator muscles.

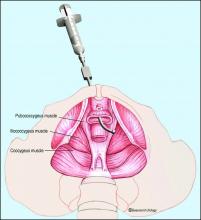

Pelvic floor dysfunction

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.

A holistic approach

Managing patients with voiding dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain can be a challenge, and a multidisciplinary approach is most effective. At Beaumont, we have a Women’s Urology Center that includes urologists, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, pain psychologists, colorectal specialists, sex therapists, and naturopathic and integrative medicine specialists who perform acupuncture, Reiki therapy, medical massage, and guided imagery.

The goal is to break out of our box of specialties and look at the whole patient – mind, body, and soul – while identifying pain triggers and directing therapy toward these triggers using a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. For us, this approach has been very effective for managing complex pelvic pain issues (Transl Androl Urol. 2015 Dec;4[6]:611-9).

Ongoing studies

A number of research studies are ongoing to help treat the symptoms of IC/BPS. We currently have a Department of Defense grant to prospectively assess bladder-directed therapy (instillations) compared to pelvic floor physical therapy. Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS are being randomized into these two treatment arms and we hope to get a better understanding of the role of these modalities in managing IC/BPS.

Allergan is completing a phase II placebo-controlled trial using a lidocaine delivery device that is placed in the bladder and continuously releases lidocaine over 14 days. The LiNKA trial is designed to assess the impact of lidocaine on not only improving bladder symptoms, but also eradicating Hunner’s lesions through the anti-inflammatory effect of lidocaine. Early open-label data were very promising. In addition, a new medication for IC/BPS that modulates the SHIP1 pathway is being studied by Aquinox Pharmaceuticals. The agent, AQX-1125, is an activator of SHIP1, which controls the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cellular signaling pathway. If the PI3K pathway is overactive, immune cells can produce an abundance of proinflammatory signaling molecules and migrate to and concentrate in tissues, resulting in excessive or chronic inflammation. Early data in IC/BPS patients were supportive of the compound’s potential for reducing the pain associated with this condition.

A note from Charles E. Miller, MD, Master Class Medical Editor:

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study by J.C. Nickel, et al., pentosan polysulfate sodium was shown to improve pain, urgency, and frequency over the control group (Urology. 2005 Apr;65[4]:654-8). Also, longer duration of treatment with pentosan polysulfate sodium was associated with greater response rates – 50% improved by 26 weeks (J Urol. 2005 Dec;174[6]:2235-8).

Dr. Peters is professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Mich. He reported serving as a consultant for Taris, Medtronic, StimGuard, and Amphora Medical.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.

Hunner’s lesions

Patients with Hunner’s lesions have a rapid onset of symptoms, typically are older, and have a visible lesion in their bladder that almost always is on the dome or lateral walls. The lesion is often erythematous with central vascularity and mucosal sloughing.

The bladder is a storage organ and urine is toxic. The exposed ulcer results in severe pain with bladder filling and also pain at the end of voiding as the bladder collapses, causing ulcerated tissue to come into contact with other sections of the bladder wall and sending a “jolt” of pain through the pelvis.

If the initial cystoscopy demonstrates inflammatory-appearing lesions or ulcerations suggestive of Hunner’s lesions, I will still do a hydrodistension. By stretching the bladder, the lesions typically expand, crack, and bleed. This helps define the entire diseased area and shows what areas of the bladder need to be cauterized to seal the ulcers and destroy the exposed nerve endings. If this is a new diagnosis, the lesion should be biopsied after the hydrodistension to rule out carcinoma.

Hunner’s lesions can lead to rapid disease progression due to chronic inflammation and subsequent collagen deposition and scarring. Even on initial diagnosis of Hunner’s lesions, a capacity of 350 cc or less (compared with 1,100 cc in a normal bladder) on hydrodistension under anesthesia is not uncommon. This markedly reduced bladder capacity may lead to end-stage bladder impacting the kidneys and requiring a urinary diversion.

Eradicating the ulcers with resection or cautery often results in marked and immediate improvement in bladder pain, albeit not long-lasting. I will typically place a resectoscope and use a roller ball at 25 watts of current. The entire ulcerated areas are cauterized by rapidly rolling the ball over the area of inflammation and avoiding a deep thermal burn. The goal is to seal the ulcer and destroy the exposed nerve endings so that urine can no longer act as an irritant. Recurrence in 6 months to 1 year is common and retreatment is almost always necessary. We have demonstrated, however, that recurrent cautery of ulcers does not lead to smaller anesthetic bladder capacities (Urology. 2015 Jan;85[1]:74-8).

Low-dose cyclosporine can be very effective at reducing Hunner’s lesion recurrence and improving storage symptoms (Exp Ther Med. 2016 Jul;12[1]:445-50). I use 100 mg twice a day for a month and then 1 pill a day thereafter. This is a relatively low dose, but hypertension can be a side effect and blood pressure should be monitored along with routine labs.

The broader picture

Hunner’s lesion IC is pretty straightforward and clearly a bladder disease. However, in recent years the term IC/BPS has been broadly used to describe women who have symptoms of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, and frequency, but no true bladder pathology to explain their symptoms. One problem: There is no definitive diagnostic test or evidence-based diagnostic process for IC/BPS. In fact, the diagnosis section of the American Urological Association guideline on diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS, last updated in 2015, is almost entirely consensus-based (J Urol. 2015 May;193[5]:1545-53). It largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

As the AUA guidelines state, a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory assessment are all important for documenting symptoms and signs and ruling out significant causes of the symptoms. I frequently see patients who have been diagnosed with IC who have frequency and urgency but no pain (in which case overactive bladder should be considered) or who have pelvic pain but no bladder symptoms, again likely not IC. Pain that worsens with bladder filling and improves after bladder emptying is typical of IC/BPS. This finding in the absence of other confusing symptoms supports the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

It has become too easy for the average clinician to apply a label of IC/BPS to a patient complaining of pelvic pain; this often results in the patient undergoing invasive and nonhelpful therapies such as cystoscopy, hydrodistension, urodynamics, bladder instillations, and other bladder-directed therapies.

More than 20 years of research supported by the National Institutes of Health and industry have failed to show that bladder-directed therapy is superior to placebo. This fact suggests that the bladder may be an innocent bystander in a larger pelvic process. As clinicians, we must be willing to look beyond the bladder and examine for pelvic floor issues and other causes of patient’s symptoms and not be too quick to begin bladder-focused treatments.

A number of disease processes – such as recurrent urinary tract infection, urethral diverticulum, endometriosis, and pudendal neuropathy – can mimic the symptoms of IC/BPS. The most common missed diagnosis in the IC patient is pelvic floor dysfunction that results in a hypertonic contracted state of the levator muscles – a chronic spasm, in essence – that in turn leads to decreased muscle function, increased myofascial pain, and myofascial trigger points (Curr Urol Rep. 2006 Nov;7[6]:450-5).

We and others have reported that up to 85% of patients labeled with IC/BPS have been found on examination to have pelvic floor dysfunction or a diffuse pelvic floor hypersensitivity. The pelvic floor is important in maintaining healthy bladder, bowel, and sexual function. If the pelvic floor is in spasm, this can result in urinary frequency, hesitancy, and pelvic pain.

Many of these patients with contracted pelvic floor muscles report pain with sexual intercourse – often so severe as to cause abstention. In fact, when patients answer no to the question of whether they have pain with intercourse, I know it is unlikely that they have significant pelvic floor dysfunction. This is a key question for history taking.

Other key questions concern the impact of stress on symptoms and a history of any type of abuse. In a study we conducted about 10 years ago, we found that among 76 women who were diagnosed with IC and subsequently evaluated in our clinic, almost half (49%) reported abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual). The vast majority (85%) had levator pain (J Urol. 2007 Sep;178[3 Pt 1]:891-5).

Other types of stress – from past surgeries to traumatic life events – may similarly serve as triggers or precursors to pelvic floor dysfunction in some women. I often tell patients that people put stress in different areas of their bodies. While some get tension headaches or low-back aches, others get pelvic pain from contracting and guarding the levator muscles.

Pelvic floor dysfunction

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.

A holistic approach

Managing patients with voiding dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain can be a challenge, and a multidisciplinary approach is most effective. At Beaumont, we have a Women’s Urology Center that includes urologists, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, pain psychologists, colorectal specialists, sex therapists, and naturopathic and integrative medicine specialists who perform acupuncture, Reiki therapy, medical massage, and guided imagery.

The goal is to break out of our box of specialties and look at the whole patient – mind, body, and soul – while identifying pain triggers and directing therapy toward these triggers using a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. For us, this approach has been very effective for managing complex pelvic pain issues (Transl Androl Urol. 2015 Dec;4[6]:611-9).

Ongoing studies

A number of research studies are ongoing to help treat the symptoms of IC/BPS. We currently have a Department of Defense grant to prospectively assess bladder-directed therapy (instillations) compared to pelvic floor physical therapy. Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS are being randomized into these two treatment arms and we hope to get a better understanding of the role of these modalities in managing IC/BPS.

Allergan is completing a phase II placebo-controlled trial using a lidocaine delivery device that is placed in the bladder and continuously releases lidocaine over 14 days. The LiNKA trial is designed to assess the impact of lidocaine on not only improving bladder symptoms, but also eradicating Hunner’s lesions through the anti-inflammatory effect of lidocaine. Early open-label data were very promising. In addition, a new medication for IC/BPS that modulates the SHIP1 pathway is being studied by Aquinox Pharmaceuticals. The agent, AQX-1125, is an activator of SHIP1, which controls the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cellular signaling pathway. If the PI3K pathway is overactive, immune cells can produce an abundance of proinflammatory signaling molecules and migrate to and concentrate in tissues, resulting in excessive or chronic inflammation. Early data in IC/BPS patients were supportive of the compound’s potential for reducing the pain associated with this condition.

A note from Charles E. Miller, MD, Master Class Medical Editor:

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study by J.C. Nickel, et al., pentosan polysulfate sodium was shown to improve pain, urgency, and frequency over the control group (Urology. 2005 Apr;65[4]:654-8). Also, longer duration of treatment with pentosan polysulfate sodium was associated with greater response rates – 50% improved by 26 weeks (J Urol. 2005 Dec;174[6]:2235-8).

Dr. Peters is professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Mich. He reported serving as a consultant for Taris, Medtronic, StimGuard, and Amphora Medical.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.

Hunner’s lesions

Patients with Hunner’s lesions have a rapid onset of symptoms, typically are older, and have a visible lesion in their bladder that almost always is on the dome or lateral walls. The lesion is often erythematous with central vascularity and mucosal sloughing.

The bladder is a storage organ and urine is toxic. The exposed ulcer results in severe pain with bladder filling and also pain at the end of voiding as the bladder collapses, causing ulcerated tissue to come into contact with other sections of the bladder wall and sending a “jolt” of pain through the pelvis.

If the initial cystoscopy demonstrates inflammatory-appearing lesions or ulcerations suggestive of Hunner’s lesions, I will still do a hydrodistension. By stretching the bladder, the lesions typically expand, crack, and bleed. This helps define the entire diseased area and shows what areas of the bladder need to be cauterized to seal the ulcers and destroy the exposed nerve endings. If this is a new diagnosis, the lesion should be biopsied after the hydrodistension to rule out carcinoma.

Hunner’s lesions can lead to rapid disease progression due to chronic inflammation and subsequent collagen deposition and scarring. Even on initial diagnosis of Hunner’s lesions, a capacity of 350 cc or less (compared with 1,100 cc in a normal bladder) on hydrodistension under anesthesia is not uncommon. This markedly reduced bladder capacity may lead to end-stage bladder impacting the kidneys and requiring a urinary diversion.

Eradicating the ulcers with resection or cautery often results in marked and immediate improvement in bladder pain, albeit not long-lasting. I will typically place a resectoscope and use a roller ball at 25 watts of current. The entire ulcerated areas are cauterized by rapidly rolling the ball over the area of inflammation and avoiding a deep thermal burn. The goal is to seal the ulcer and destroy the exposed nerve endings so that urine can no longer act as an irritant. Recurrence in 6 months to 1 year is common and retreatment is almost always necessary. We have demonstrated, however, that recurrent cautery of ulcers does not lead to smaller anesthetic bladder capacities (Urology. 2015 Jan;85[1]:74-8).

Low-dose cyclosporine can be very effective at reducing Hunner’s lesion recurrence and improving storage symptoms (Exp Ther Med. 2016 Jul;12[1]:445-50). I use 100 mg twice a day for a month and then 1 pill a day thereafter. This is a relatively low dose, but hypertension can be a side effect and blood pressure should be monitored along with routine labs.

The broader picture

Hunner’s lesion IC is pretty straightforward and clearly a bladder disease. However, in recent years the term IC/BPS has been broadly used to describe women who have symptoms of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, and frequency, but no true bladder pathology to explain their symptoms. One problem: There is no definitive diagnostic test or evidence-based diagnostic process for IC/BPS. In fact, the diagnosis section of the American Urological Association guideline on diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS, last updated in 2015, is almost entirely consensus-based (J Urol. 2015 May;193[5]:1545-53). It largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

As the AUA guidelines state, a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory assessment are all important for documenting symptoms and signs and ruling out significant causes of the symptoms. I frequently see patients who have been diagnosed with IC who have frequency and urgency but no pain (in which case overactive bladder should be considered) or who have pelvic pain but no bladder symptoms, again likely not IC. Pain that worsens with bladder filling and improves after bladder emptying is typical of IC/BPS. This finding in the absence of other confusing symptoms supports the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

It has become too easy for the average clinician to apply a label of IC/BPS to a patient complaining of pelvic pain; this often results in the patient undergoing invasive and nonhelpful therapies such as cystoscopy, hydrodistension, urodynamics, bladder instillations, and other bladder-directed therapies.

More than 20 years of research supported by the National Institutes of Health and industry have failed to show that bladder-directed therapy is superior to placebo. This fact suggests that the bladder may be an innocent bystander in a larger pelvic process. As clinicians, we must be willing to look beyond the bladder and examine for pelvic floor issues and other causes of patient’s symptoms and not be too quick to begin bladder-focused treatments.

A number of disease processes – such as recurrent urinary tract infection, urethral diverticulum, endometriosis, and pudendal neuropathy – can mimic the symptoms of IC/BPS. The most common missed diagnosis in the IC patient is pelvic floor dysfunction that results in a hypertonic contracted state of the levator muscles – a chronic spasm, in essence – that in turn leads to decreased muscle function, increased myofascial pain, and myofascial trigger points (Curr Urol Rep. 2006 Nov;7[6]:450-5).

We and others have reported that up to 85% of patients labeled with IC/BPS have been found on examination to have pelvic floor dysfunction or a diffuse pelvic floor hypersensitivity. The pelvic floor is important in maintaining healthy bladder, bowel, and sexual function. If the pelvic floor is in spasm, this can result in urinary frequency, hesitancy, and pelvic pain.

Many of these patients with contracted pelvic floor muscles report pain with sexual intercourse – often so severe as to cause abstention. In fact, when patients answer no to the question of whether they have pain with intercourse, I know it is unlikely that they have significant pelvic floor dysfunction. This is a key question for history taking.

Other key questions concern the impact of stress on symptoms and a history of any type of abuse. In a study we conducted about 10 years ago, we found that among 76 women who were diagnosed with IC and subsequently evaluated in our clinic, almost half (49%) reported abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual). The vast majority (85%) had levator pain (J Urol. 2007 Sep;178[3 Pt 1]:891-5).

Other types of stress – from past surgeries to traumatic life events – may similarly serve as triggers or precursors to pelvic floor dysfunction in some women. I often tell patients that people put stress in different areas of their bodies. While some get tension headaches or low-back aches, others get pelvic pain from contracting and guarding the levator muscles.

Pelvic floor dysfunction

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.

A holistic approach

Managing patients with voiding dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain can be a challenge, and a multidisciplinary approach is most effective. At Beaumont, we have a Women’s Urology Center that includes urologists, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, pain psychologists, colorectal specialists, sex therapists, and naturopathic and integrative medicine specialists who perform acupuncture, Reiki therapy, medical massage, and guided imagery.

The goal is to break out of our box of specialties and look at the whole patient – mind, body, and soul – while identifying pain triggers and directing therapy toward these triggers using a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. For us, this approach has been very effective for managing complex pelvic pain issues (Transl Androl Urol. 2015 Dec;4[6]:611-9).

Ongoing studies

A number of research studies are ongoing to help treat the symptoms of IC/BPS. We currently have a Department of Defense grant to prospectively assess bladder-directed therapy (instillations) compared to pelvic floor physical therapy. Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS are being randomized into these two treatment arms and we hope to get a better understanding of the role of these modalities in managing IC/BPS.