User login

Expert provides deeper insight into tocilizumab for giant cell arteritis

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The sustained remission rate in patients with giant cell arteritis was three times better with subcutaneous tocilizumab than with long-term prednisone in the landmark GiACTA trial, John H. Stone, MD, reported at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, the serious adverse event rate was significantly lower with the interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab (Actemra). This finding serves to underscore the pronounced, yet sometimes stealthy, toxicity of long-term, high-dose prednisone. Many rheumatologists have underplayed these side effects for lack of a better treatment option, because until the randomized, double-blind GiACTA trial, corticosteroids were the standard of care and only known effective therapy for giant cell arteritis (GCA), observed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“There’s finally something new in giant cell arteritis,” the rheumatologist declared. “The era of unending steroid therapy with no viable alternative is over.”

Dr. Stone was global principal investigator in GiACTA, a 14-country study including 251 GCA patients, roughly evenly divided between newly diagnosed patients and those with previously treated relapsing disease. GiACTA, he noted, was a study of several firsts: the first-ever clinical trial in any disease to utilize a blinded variable-dose steroid regimen, the first to feature a double-blind steroid-tapering regimen, and the first prospective study of 1 full year of tapered-dose prednisone.

The primary outcome was sustained remission as defined by absence of flare during study weeks 12-52 coupled with normalization of the C-reactive protein level to less than 1 mg/dL. This sustained remission endpoint was achieved in 14% of patients on 26 weeks of prednisone plus placebo and 17.6% of those on 52 weeks of prednisone and placebo.

“The results in the two steroid arms are lousy,” the rheumatologist pointed out. “This is I think one of the most astounding things about the trial.”

In sharp contrast, the sustained remission rate was 56% with 162 mg of subcutaneous tocilizumab once weekly plus 26 weeks of prednisone, and 53.1% with 162 mg of the humanized monoclonal antibody every 2 weeks plus 26 weeks of prednisone.

Tocilizumab’s steroid-sparing capability was impressive. The mean cumulative prednisone dose was 4,199 mg in patients on a 52-week prednisone taper plus placebo – a steroid regimen that most closely mimics what most rheumatologists have until now considered standard practice – versus only 2,098 mg in patients on once-weekly tocilizumab plus a 26-week prednisone taper.

Serious adverse events occurred in 24% of patients on prednisone-only, compared with less than 15% of those on tocilizumab. Quality of life scores as measured on the physical component score of the Short Form–36 were significantly better in the tocilizumab recipients.

“I think this speaks again to corticosteroid toxicity,” Dr. Stone said.

Another corticosteroid toxicity underscored in GiACTA was weight gain. At enrollment, patients with newly diagnosed GCA weighed significantly less than did those with previously diagnosed, relapsing disease for which they’d already been on long-term steroids. This body weight disparity was particularly pronounced in men. Men with relapsing GCA weighed a mean of 18.6 pounds more at baseline – nearly three additional body mass index points – than did newly diagnosed men who hadn’t been on aggressive steroid therapy.

“This is a steroid toxicity that I think sneaks up on us,” Dr. Stone observed.

The ongoing GiACTA study is continuing for an additional 2 years of open-label tocilizumab restricted to participants who flared during the initial double-blind phase or thereafter.

Joel M. Kremer, MD, rose from the audience to pronounce GiACTA “a home run.”

“I thought this was the most important study presented at the 2016 ACR annual meeting,” added Dr. Kremer, professor of medicine at the University of Albany (N.Y.) and president and founder of CORRONA, the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America.

The Snowmass symposium afforded Dr. Stone the opportunity to delve into aspects of GiACTA that time didn’t permit him to address at the 2016 ACR annual meeting:

• What’s the best dose of tocilizumab?

Weekly therapy appears to be preferable, although that’s a decision for the regulatory agencies. Time to first relapse post steroid taper was significantly longer with weekly than with biweekly tocilizumab, a result driven primarily by a markedly better result in the baseline relapser group. The pharmacokinetic data also support weekly dosing: Although patients randomized to weekly tocilizumab got twice as much of the biologic over the course of 52 weeks, their serum trough levels were actually six times higher than in those on biweekly therapy.

“This has implications for control of acute phase reactants,” the rheumatologist noted.

• Which patients with GCA should receive tocilizumab, and for how long?

The GiACTA finding that patients on 52 weeks of prednisone were only one-third as likely to be in continuous remission at 1 year is a deal breaker for the traditional therapy so far as Dr. Stone is concerned, he said in response to an audience question.

“I would treat almost everyone with tocilizumab right out of the gate, and I think the goal is to get them off concomitant prednisone fast. I think we can probably achieve that in less than the 6 months we used in GiACTA,” he said.

The ongoing second, open-label phase of the study will be informative regarding optimal treatment duration. In the meantime, the rheumatologist said, “I would treat patients for 12 months and then follow them to see what they need. We treat ANCA-associated vasculitis with rituximab and steroids, and some of them go into remission that lasts 5 years. I think some giant cell arteritis patients will be the same way, and others will flare right after you stop tocilizumab or maybe even while they’re still on it. Tocilizumab is not a cure, and these patients will still need to be followed closely.”

• What about intravenous tocilizumab, the far less costly option under Medicare?

The Food and Drug Administration will consider approval only for subcutaneous tocilizumab in GCA, since that what was used in GiACTA, although Dr. Stone is convinced based upon personal experience that the subcutaneous and intravenous formulations act identically. Roche/Genentech officials have told him they will pursue a separate approval process for the intravenous formulation.

• How about Takayasu’s arteritis?

It looks like a separate approval process, including a new study, will be required for this form of large-vessel vasculitis, Dr. Stone said.

• Intriguing baseline clinical features in GiACTA:

Mouth pain/jaw claudication was present in 34% of the GCA patients at enrollment.

“Jaw claudication is, I think, vastly underestimated as a very important symptom in giant cell arteritis. Of course, patients don’t say, ‘I have jaw claudication today, doc.’ You have to ask about it specifically. It’s not part of the ACR criteria, and I think it should be,” Dr. Stone said.

Also, cranial symptoms were present in only 79% of patients at enrollment.

“I think that’s important for physicians to know: One-fifth of patients had no cranial symptoms when they were enrolled in the study,” he continued.

Another key finding: Only 67% of GCA patients had a new-onset headache at enrollment.

“We think of headache as being so crucial in this disease, and it is important, but only two-thirds of patients in this trial had it,” the rheumatologist said.

Also, 62% of GCA patients had polymyalgia rheumatica at enrollment. More interestingly, 21% of patients with confirmed GCA had only polymyalgia rheumatica, with no cranial symptoms at all.

Dr. Stone reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Roche/Genentech, which sponsored GiACTA and markets tocilizumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The sustained remission rate in patients with giant cell arteritis was three times better with subcutaneous tocilizumab than with long-term prednisone in the landmark GiACTA trial, John H. Stone, MD, reported at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, the serious adverse event rate was significantly lower with the interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab (Actemra). This finding serves to underscore the pronounced, yet sometimes stealthy, toxicity of long-term, high-dose prednisone. Many rheumatologists have underplayed these side effects for lack of a better treatment option, because until the randomized, double-blind GiACTA trial, corticosteroids were the standard of care and only known effective therapy for giant cell arteritis (GCA), observed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“There’s finally something new in giant cell arteritis,” the rheumatologist declared. “The era of unending steroid therapy with no viable alternative is over.”

Dr. Stone was global principal investigator in GiACTA, a 14-country study including 251 GCA patients, roughly evenly divided between newly diagnosed patients and those with previously treated relapsing disease. GiACTA, he noted, was a study of several firsts: the first-ever clinical trial in any disease to utilize a blinded variable-dose steroid regimen, the first to feature a double-blind steroid-tapering regimen, and the first prospective study of 1 full year of tapered-dose prednisone.

The primary outcome was sustained remission as defined by absence of flare during study weeks 12-52 coupled with normalization of the C-reactive protein level to less than 1 mg/dL. This sustained remission endpoint was achieved in 14% of patients on 26 weeks of prednisone plus placebo and 17.6% of those on 52 weeks of prednisone and placebo.

“The results in the two steroid arms are lousy,” the rheumatologist pointed out. “This is I think one of the most astounding things about the trial.”

In sharp contrast, the sustained remission rate was 56% with 162 mg of subcutaneous tocilizumab once weekly plus 26 weeks of prednisone, and 53.1% with 162 mg of the humanized monoclonal antibody every 2 weeks plus 26 weeks of prednisone.

Tocilizumab’s steroid-sparing capability was impressive. The mean cumulative prednisone dose was 4,199 mg in patients on a 52-week prednisone taper plus placebo – a steroid regimen that most closely mimics what most rheumatologists have until now considered standard practice – versus only 2,098 mg in patients on once-weekly tocilizumab plus a 26-week prednisone taper.

Serious adverse events occurred in 24% of patients on prednisone-only, compared with less than 15% of those on tocilizumab. Quality of life scores as measured on the physical component score of the Short Form–36 were significantly better in the tocilizumab recipients.

“I think this speaks again to corticosteroid toxicity,” Dr. Stone said.

Another corticosteroid toxicity underscored in GiACTA was weight gain. At enrollment, patients with newly diagnosed GCA weighed significantly less than did those with previously diagnosed, relapsing disease for which they’d already been on long-term steroids. This body weight disparity was particularly pronounced in men. Men with relapsing GCA weighed a mean of 18.6 pounds more at baseline – nearly three additional body mass index points – than did newly diagnosed men who hadn’t been on aggressive steroid therapy.

“This is a steroid toxicity that I think sneaks up on us,” Dr. Stone observed.

The ongoing GiACTA study is continuing for an additional 2 years of open-label tocilizumab restricted to participants who flared during the initial double-blind phase or thereafter.

Joel M. Kremer, MD, rose from the audience to pronounce GiACTA “a home run.”

“I thought this was the most important study presented at the 2016 ACR annual meeting,” added Dr. Kremer, professor of medicine at the University of Albany (N.Y.) and president and founder of CORRONA, the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America.

The Snowmass symposium afforded Dr. Stone the opportunity to delve into aspects of GiACTA that time didn’t permit him to address at the 2016 ACR annual meeting:

• What’s the best dose of tocilizumab?

Weekly therapy appears to be preferable, although that’s a decision for the regulatory agencies. Time to first relapse post steroid taper was significantly longer with weekly than with biweekly tocilizumab, a result driven primarily by a markedly better result in the baseline relapser group. The pharmacokinetic data also support weekly dosing: Although patients randomized to weekly tocilizumab got twice as much of the biologic over the course of 52 weeks, their serum trough levels were actually six times higher than in those on biweekly therapy.

“This has implications for control of acute phase reactants,” the rheumatologist noted.

• Which patients with GCA should receive tocilizumab, and for how long?

The GiACTA finding that patients on 52 weeks of prednisone were only one-third as likely to be in continuous remission at 1 year is a deal breaker for the traditional therapy so far as Dr. Stone is concerned, he said in response to an audience question.

“I would treat almost everyone with tocilizumab right out of the gate, and I think the goal is to get them off concomitant prednisone fast. I think we can probably achieve that in less than the 6 months we used in GiACTA,” he said.

The ongoing second, open-label phase of the study will be informative regarding optimal treatment duration. In the meantime, the rheumatologist said, “I would treat patients for 12 months and then follow them to see what they need. We treat ANCA-associated vasculitis with rituximab and steroids, and some of them go into remission that lasts 5 years. I think some giant cell arteritis patients will be the same way, and others will flare right after you stop tocilizumab or maybe even while they’re still on it. Tocilizumab is not a cure, and these patients will still need to be followed closely.”

• What about intravenous tocilizumab, the far less costly option under Medicare?

The Food and Drug Administration will consider approval only for subcutaneous tocilizumab in GCA, since that what was used in GiACTA, although Dr. Stone is convinced based upon personal experience that the subcutaneous and intravenous formulations act identically. Roche/Genentech officials have told him they will pursue a separate approval process for the intravenous formulation.

• How about Takayasu’s arteritis?

It looks like a separate approval process, including a new study, will be required for this form of large-vessel vasculitis, Dr. Stone said.

• Intriguing baseline clinical features in GiACTA:

Mouth pain/jaw claudication was present in 34% of the GCA patients at enrollment.

“Jaw claudication is, I think, vastly underestimated as a very important symptom in giant cell arteritis. Of course, patients don’t say, ‘I have jaw claudication today, doc.’ You have to ask about it specifically. It’s not part of the ACR criteria, and I think it should be,” Dr. Stone said.

Also, cranial symptoms were present in only 79% of patients at enrollment.

“I think that’s important for physicians to know: One-fifth of patients had no cranial symptoms when they were enrolled in the study,” he continued.

Another key finding: Only 67% of GCA patients had a new-onset headache at enrollment.

“We think of headache as being so crucial in this disease, and it is important, but only two-thirds of patients in this trial had it,” the rheumatologist said.

Also, 62% of GCA patients had polymyalgia rheumatica at enrollment. More interestingly, 21% of patients with confirmed GCA had only polymyalgia rheumatica, with no cranial symptoms at all.

Dr. Stone reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Roche/Genentech, which sponsored GiACTA and markets tocilizumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The sustained remission rate in patients with giant cell arteritis was three times better with subcutaneous tocilizumab than with long-term prednisone in the landmark GiACTA trial, John H. Stone, MD, reported at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Moreover, the serious adverse event rate was significantly lower with the interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab (Actemra). This finding serves to underscore the pronounced, yet sometimes stealthy, toxicity of long-term, high-dose prednisone. Many rheumatologists have underplayed these side effects for lack of a better treatment option, because until the randomized, double-blind GiACTA trial, corticosteroids were the standard of care and only known effective therapy for giant cell arteritis (GCA), observed Dr. Stone, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“There’s finally something new in giant cell arteritis,” the rheumatologist declared. “The era of unending steroid therapy with no viable alternative is over.”

Dr. Stone was global principal investigator in GiACTA, a 14-country study including 251 GCA patients, roughly evenly divided between newly diagnosed patients and those with previously treated relapsing disease. GiACTA, he noted, was a study of several firsts: the first-ever clinical trial in any disease to utilize a blinded variable-dose steroid regimen, the first to feature a double-blind steroid-tapering regimen, and the first prospective study of 1 full year of tapered-dose prednisone.

The primary outcome was sustained remission as defined by absence of flare during study weeks 12-52 coupled with normalization of the C-reactive protein level to less than 1 mg/dL. This sustained remission endpoint was achieved in 14% of patients on 26 weeks of prednisone plus placebo and 17.6% of those on 52 weeks of prednisone and placebo.

“The results in the two steroid arms are lousy,” the rheumatologist pointed out. “This is I think one of the most astounding things about the trial.”

In sharp contrast, the sustained remission rate was 56% with 162 mg of subcutaneous tocilizumab once weekly plus 26 weeks of prednisone, and 53.1% with 162 mg of the humanized monoclonal antibody every 2 weeks plus 26 weeks of prednisone.

Tocilizumab’s steroid-sparing capability was impressive. The mean cumulative prednisone dose was 4,199 mg in patients on a 52-week prednisone taper plus placebo – a steroid regimen that most closely mimics what most rheumatologists have until now considered standard practice – versus only 2,098 mg in patients on once-weekly tocilizumab plus a 26-week prednisone taper.

Serious adverse events occurred in 24% of patients on prednisone-only, compared with less than 15% of those on tocilizumab. Quality of life scores as measured on the physical component score of the Short Form–36 were significantly better in the tocilizumab recipients.

“I think this speaks again to corticosteroid toxicity,” Dr. Stone said.

Another corticosteroid toxicity underscored in GiACTA was weight gain. At enrollment, patients with newly diagnosed GCA weighed significantly less than did those with previously diagnosed, relapsing disease for which they’d already been on long-term steroids. This body weight disparity was particularly pronounced in men. Men with relapsing GCA weighed a mean of 18.6 pounds more at baseline – nearly three additional body mass index points – than did newly diagnosed men who hadn’t been on aggressive steroid therapy.

“This is a steroid toxicity that I think sneaks up on us,” Dr. Stone observed.

The ongoing GiACTA study is continuing for an additional 2 years of open-label tocilizumab restricted to participants who flared during the initial double-blind phase or thereafter.

Joel M. Kremer, MD, rose from the audience to pronounce GiACTA “a home run.”

“I thought this was the most important study presented at the 2016 ACR annual meeting,” added Dr. Kremer, professor of medicine at the University of Albany (N.Y.) and president and founder of CORRONA, the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America.

The Snowmass symposium afforded Dr. Stone the opportunity to delve into aspects of GiACTA that time didn’t permit him to address at the 2016 ACR annual meeting:

• What’s the best dose of tocilizumab?

Weekly therapy appears to be preferable, although that’s a decision for the regulatory agencies. Time to first relapse post steroid taper was significantly longer with weekly than with biweekly tocilizumab, a result driven primarily by a markedly better result in the baseline relapser group. The pharmacokinetic data also support weekly dosing: Although patients randomized to weekly tocilizumab got twice as much of the biologic over the course of 52 weeks, their serum trough levels were actually six times higher than in those on biweekly therapy.

“This has implications for control of acute phase reactants,” the rheumatologist noted.

• Which patients with GCA should receive tocilizumab, and for how long?

The GiACTA finding that patients on 52 weeks of prednisone were only one-third as likely to be in continuous remission at 1 year is a deal breaker for the traditional therapy so far as Dr. Stone is concerned, he said in response to an audience question.

“I would treat almost everyone with tocilizumab right out of the gate, and I think the goal is to get them off concomitant prednisone fast. I think we can probably achieve that in less than the 6 months we used in GiACTA,” he said.

The ongoing second, open-label phase of the study will be informative regarding optimal treatment duration. In the meantime, the rheumatologist said, “I would treat patients for 12 months and then follow them to see what they need. We treat ANCA-associated vasculitis with rituximab and steroids, and some of them go into remission that lasts 5 years. I think some giant cell arteritis patients will be the same way, and others will flare right after you stop tocilizumab or maybe even while they’re still on it. Tocilizumab is not a cure, and these patients will still need to be followed closely.”

• What about intravenous tocilizumab, the far less costly option under Medicare?

The Food and Drug Administration will consider approval only for subcutaneous tocilizumab in GCA, since that what was used in GiACTA, although Dr. Stone is convinced based upon personal experience that the subcutaneous and intravenous formulations act identically. Roche/Genentech officials have told him they will pursue a separate approval process for the intravenous formulation.

• How about Takayasu’s arteritis?

It looks like a separate approval process, including a new study, will be required for this form of large-vessel vasculitis, Dr. Stone said.

• Intriguing baseline clinical features in GiACTA:

Mouth pain/jaw claudication was present in 34% of the GCA patients at enrollment.

“Jaw claudication is, I think, vastly underestimated as a very important symptom in giant cell arteritis. Of course, patients don’t say, ‘I have jaw claudication today, doc.’ You have to ask about it specifically. It’s not part of the ACR criteria, and I think it should be,” Dr. Stone said.

Also, cranial symptoms were present in only 79% of patients at enrollment.

“I think that’s important for physicians to know: One-fifth of patients had no cranial symptoms when they were enrolled in the study,” he continued.

Another key finding: Only 67% of GCA patients had a new-onset headache at enrollment.

“We think of headache as being so crucial in this disease, and it is important, but only two-thirds of patients in this trial had it,” the rheumatologist said.

Also, 62% of GCA patients had polymyalgia rheumatica at enrollment. More interestingly, 21% of patients with confirmed GCA had only polymyalgia rheumatica, with no cranial symptoms at all.

Dr. Stone reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Roche/Genentech, which sponsored GiACTA and markets tocilizumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

VIDEO: Grading tools help set alopecia treatment expectations and monitor progress

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Two hair loss clinical grading tools can help physicians and their female androgenetic alopecia patients set medical treatment expectations, and make tracking progress both easier and more accurate, according to the dermatologist who developed the scales.

The five-point clinical grading scale helps physicians with diagnosing female pattern hair loss and grading the severity, Rodney Sinclair, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “And you can use that clinical grading scale to monitor the response to treatment” and show patients what to expect with treatment, added Dr. Sinclair, professor and chairman, department of dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne.

He also discussed a validated hair shedding scale, “a really simple and easy test to use,” with six photographs to help patients determine how much hair they are shedding on a daily basis. “Most women don’t know what’s a normal amount of hair to shed,” he said. In the interview, Dr. Sinclair explains more about the two scales, and how they can be used to obtain clinically relevant information to help guide treatment – and shares his tips for how to work with women who are anxious about their hair loss improvement.

Dr. Sinclair owns the copyrights for the Sinclair Severity Scale. He has no other relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AAD 17

Health care costs higher after prolonged ventilation

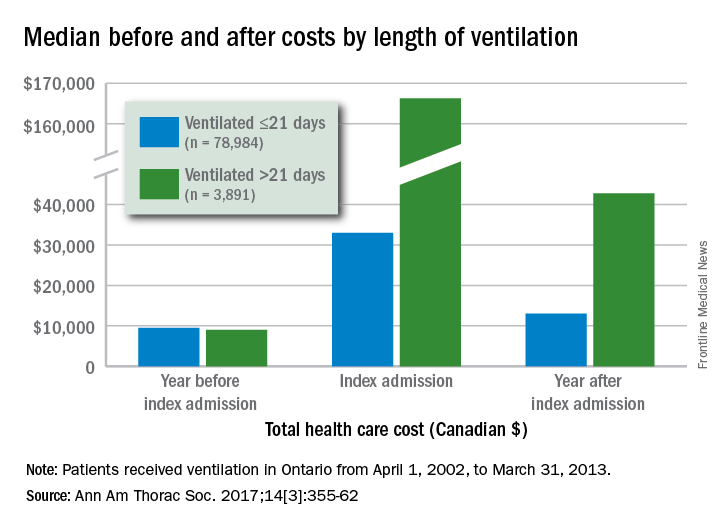

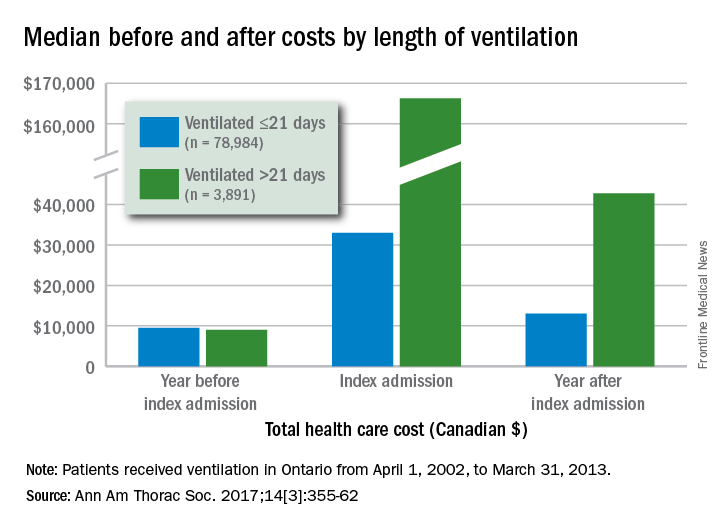

Postadmission health care costs varied considerably by the duration of patients’ in-hospital mechanical ventilation, according to a study of Canadian administrative databases.

Critically ill patients in the province of Ontario who received mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days (n = 3,891) had a median health care cost of $42,784 (all costs are in Canadian dollars) in the year after their discharge, compared with $13,005 for patients who were ventilated for 21 or fewer days (n = 78,984), reported Andrea D. Hill, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and her associates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14[3]:355-62).

Dr. Hill and her associates also found that patients with longer-term ventilation were less likely to be discharged home (15% vs. 57%) and more likely to be readmitted after 6 months (36% vs. 29%) or 1 year (47% vs. 38%), but were not more likely to have an emergency department visit after 6 months (46% vs. 45%).

All patients received ventilation from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2013. The population-based cohort study used four databases: the Canadian Institute of Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database, and the Ontario Registered Persons Database.

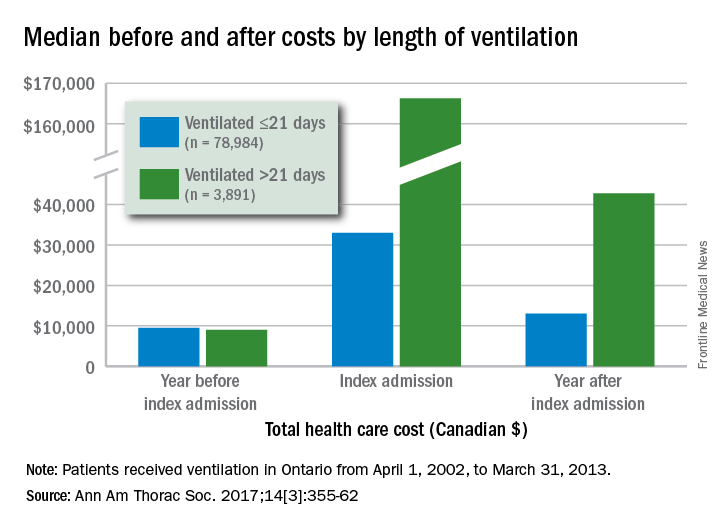

Postadmission health care costs varied considerably by the duration of patients’ in-hospital mechanical ventilation, according to a study of Canadian administrative databases.

Critically ill patients in the province of Ontario who received mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days (n = 3,891) had a median health care cost of $42,784 (all costs are in Canadian dollars) in the year after their discharge, compared with $13,005 for patients who were ventilated for 21 or fewer days (n = 78,984), reported Andrea D. Hill, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and her associates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14[3]:355-62).

Dr. Hill and her associates also found that patients with longer-term ventilation were less likely to be discharged home (15% vs. 57%) and more likely to be readmitted after 6 months (36% vs. 29%) or 1 year (47% vs. 38%), but were not more likely to have an emergency department visit after 6 months (46% vs. 45%).

All patients received ventilation from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2013. The population-based cohort study used four databases: the Canadian Institute of Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database, and the Ontario Registered Persons Database.

Postadmission health care costs varied considerably by the duration of patients’ in-hospital mechanical ventilation, according to a study of Canadian administrative databases.

Critically ill patients in the province of Ontario who received mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days (n = 3,891) had a median health care cost of $42,784 (all costs are in Canadian dollars) in the year after their discharge, compared with $13,005 for patients who were ventilated for 21 or fewer days (n = 78,984), reported Andrea D. Hill, PhD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, and her associates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14[3]:355-62).

Dr. Hill and her associates also found that patients with longer-term ventilation were less likely to be discharged home (15% vs. 57%) and more likely to be readmitted after 6 months (36% vs. 29%) or 1 year (47% vs. 38%), but were not more likely to have an emergency department visit after 6 months (46% vs. 45%).

All patients received ventilation from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2013. The population-based cohort study used four databases: the Canadian Institute of Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database, and the Ontario Registered Persons Database.

FROM ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY

Hydroxychloroquine dosage recommendations often ignored

Evidence continues to mount that some North American rheumatologists are not following practice recommendations for minimizing the retinal toxicity risk of patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine treatment.

An audit of 100 patients seen at any of nine Canadian rheumatology clinics during early 2016 showed that 30% of patients were not on appropriate weight-based hydroxychloroquine dosages, and 13% of patients on the drug had not received a baseline retinal assessment during their first year of treatment, Sahil Koppikar, MD, reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Rheumatology Association in Ottawa in February.

In a second recently reported study, researchers from the Chicago area documented that roughly half of the 554 rheumatology patients on hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a regional health system and seen by an ophthalmologist during 2009-2016 received an excessive dosage of the drug (Ophthalmology. 2017 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.021).

Although his study did not examine reasons for the compliance shortfall, Dr. Koppikar proposed some possible factors.

HCQ comes only as 200-mg tablets, and prescribing intermediate dosages can be a challenge (although veteran clinicians know that a safe and easy way to dial down a dosage is to have the patient periodically skip a dose). Also, “it is more convenient to prescribe 400 mg daily rather than calculate an exact dosage,” Dr. Koppikar said in an interview. In addition, rheumatologists may be unaware that the prevalence of retinopathy in patients on HCQ is fairly common (about 8% in one large recent study), assessment for risk factors that heighten sensitivity to the drug isn’t always done, and appointments for retinal screening can fall through the cracks.

“It behooves rheumatologists to adopt the [HCQ] recommendations of the American Academy of Ophthalmology [AAO] because there is more toxicity than we previously appreciated,” he added. A new version of the AAO’s recommendations came out in March 2016.

The Committee on Rheumatologic Care of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has regularly updated the ACR’s position statement on screening for HCQ retinopathy and appropriate dosages, with the most recent version out in August 2016. The August statement “is very similar” to the AAO’s 2016 recommendations, said Vinicius Domingues, MD, a member of the committee and an ACR spokesman for the revision. The ACR statement acknowledges and cites the AAO 2016 recommendations.

The ACR’s 2016 statement also does not fully endorse the AAO’s 2016 firm statement that “all patients using HCQ keep daily dosage less than 5.0 mg/kg real weight,” aside from “rare instances” when a higher dosage is needed to treat a “life-threatening disease.”

The ACR 2016 statement goes on to note that other authors have recommended a dosage of 6.5 mg/kg of actual body weight but capped at 400 mg/day and adjusted for renal insufficiency, and the ACR statement stops short of specifying which dosage strategy it recommends.

“The AAO recommendations are much more definitive and state more specifically what screening is recommended and what is a safe dosage,” commented Dr. Rosenbaum.

Dr. Domingues agreed that rheumatologist compliance with HCQ best practices has been spotty.

“In the past few years, more studies have used new ways to detect macular abnormalities and have identified a higher-than-expected incidence of maculopathy. Through lectures, CME, and articles, rheumatologists have received a tremendous amount of information with regard to screening and preventing retinal toxicity,” he said in an interview. “There are still gaps, and some rheumatologists still prescribe HCQ without taking into consideration the patient’s weight.”

That was a key finding in the poster presented at the Canadian Rheumatology Association by Dr. Koppikar and his collaborator on the study, Henry Averns, MD. The 100 patients assessed through the nine-clinic audit process averaged 58 years old, 81% were women, and patients had been taking HCQ for an average of just over 6 years, primarily for rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Nearly two-thirds had a high risk for retinal toxicity. Based on the 2011 recommendations from the AAO and ACR, 17% of the patients were receiving an HCQ overdose that was more than 10% above the recommended dosage, and another 13% received a smaller overdose. If the 2016 dosage guidelines were applied, the extent of overdosing might be even greater, Dr. Koppikar said.

Dr. Koppikar and Dr. Averns said they believe that one way to address HCQ overdosing is by giving clinicians a dosing chart to easily find the right dosage for a patient’s weight. They have distributed these charts to the practices they audited and plan to do a follow-up audit to measure the effect of the intervention on HCQ prescribing.

Results from the initial clinical audit showed that “clinicians were not meeting standards, and we needed an intervention [a dosing chart] to implement a change,” Dr. Koppikar said. “Clinical audits are easy to implement, cost effective, and help improve patient care.”

Dr. Koppikar, Dr. Rosenbaum, Dr. Domingues, and Dr. Averns had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence continues to mount that some North American rheumatologists are not following practice recommendations for minimizing the retinal toxicity risk of patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine treatment.

An audit of 100 patients seen at any of nine Canadian rheumatology clinics during early 2016 showed that 30% of patients were not on appropriate weight-based hydroxychloroquine dosages, and 13% of patients on the drug had not received a baseline retinal assessment during their first year of treatment, Sahil Koppikar, MD, reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Rheumatology Association in Ottawa in February.

In a second recently reported study, researchers from the Chicago area documented that roughly half of the 554 rheumatology patients on hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a regional health system and seen by an ophthalmologist during 2009-2016 received an excessive dosage of the drug (Ophthalmology. 2017 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.021).

Although his study did not examine reasons for the compliance shortfall, Dr. Koppikar proposed some possible factors.

HCQ comes only as 200-mg tablets, and prescribing intermediate dosages can be a challenge (although veteran clinicians know that a safe and easy way to dial down a dosage is to have the patient periodically skip a dose). Also, “it is more convenient to prescribe 400 mg daily rather than calculate an exact dosage,” Dr. Koppikar said in an interview. In addition, rheumatologists may be unaware that the prevalence of retinopathy in patients on HCQ is fairly common (about 8% in one large recent study), assessment for risk factors that heighten sensitivity to the drug isn’t always done, and appointments for retinal screening can fall through the cracks.

“It behooves rheumatologists to adopt the [HCQ] recommendations of the American Academy of Ophthalmology [AAO] because there is more toxicity than we previously appreciated,” he added. A new version of the AAO’s recommendations came out in March 2016.

The Committee on Rheumatologic Care of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has regularly updated the ACR’s position statement on screening for HCQ retinopathy and appropriate dosages, with the most recent version out in August 2016. The August statement “is very similar” to the AAO’s 2016 recommendations, said Vinicius Domingues, MD, a member of the committee and an ACR spokesman for the revision. The ACR statement acknowledges and cites the AAO 2016 recommendations.

The ACR’s 2016 statement also does not fully endorse the AAO’s 2016 firm statement that “all patients using HCQ keep daily dosage less than 5.0 mg/kg real weight,” aside from “rare instances” when a higher dosage is needed to treat a “life-threatening disease.”

The ACR 2016 statement goes on to note that other authors have recommended a dosage of 6.5 mg/kg of actual body weight but capped at 400 mg/day and adjusted for renal insufficiency, and the ACR statement stops short of specifying which dosage strategy it recommends.

“The AAO recommendations are much more definitive and state more specifically what screening is recommended and what is a safe dosage,” commented Dr. Rosenbaum.

Dr. Domingues agreed that rheumatologist compliance with HCQ best practices has been spotty.

“In the past few years, more studies have used new ways to detect macular abnormalities and have identified a higher-than-expected incidence of maculopathy. Through lectures, CME, and articles, rheumatologists have received a tremendous amount of information with regard to screening and preventing retinal toxicity,” he said in an interview. “There are still gaps, and some rheumatologists still prescribe HCQ without taking into consideration the patient’s weight.”

That was a key finding in the poster presented at the Canadian Rheumatology Association by Dr. Koppikar and his collaborator on the study, Henry Averns, MD. The 100 patients assessed through the nine-clinic audit process averaged 58 years old, 81% were women, and patients had been taking HCQ for an average of just over 6 years, primarily for rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Nearly two-thirds had a high risk for retinal toxicity. Based on the 2011 recommendations from the AAO and ACR, 17% of the patients were receiving an HCQ overdose that was more than 10% above the recommended dosage, and another 13% received a smaller overdose. If the 2016 dosage guidelines were applied, the extent of overdosing might be even greater, Dr. Koppikar said.

Dr. Koppikar and Dr. Averns said they believe that one way to address HCQ overdosing is by giving clinicians a dosing chart to easily find the right dosage for a patient’s weight. They have distributed these charts to the practices they audited and plan to do a follow-up audit to measure the effect of the intervention on HCQ prescribing.

Results from the initial clinical audit showed that “clinicians were not meeting standards, and we needed an intervention [a dosing chart] to implement a change,” Dr. Koppikar said. “Clinical audits are easy to implement, cost effective, and help improve patient care.”

Dr. Koppikar, Dr. Rosenbaum, Dr. Domingues, and Dr. Averns had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence continues to mount that some North American rheumatologists are not following practice recommendations for minimizing the retinal toxicity risk of patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine treatment.

An audit of 100 patients seen at any of nine Canadian rheumatology clinics during early 2016 showed that 30% of patients were not on appropriate weight-based hydroxychloroquine dosages, and 13% of patients on the drug had not received a baseline retinal assessment during their first year of treatment, Sahil Koppikar, MD, reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Rheumatology Association in Ottawa in February.

In a second recently reported study, researchers from the Chicago area documented that roughly half of the 554 rheumatology patients on hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in a regional health system and seen by an ophthalmologist during 2009-2016 received an excessive dosage of the drug (Ophthalmology. 2017 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.021).

Although his study did not examine reasons for the compliance shortfall, Dr. Koppikar proposed some possible factors.

HCQ comes only as 200-mg tablets, and prescribing intermediate dosages can be a challenge (although veteran clinicians know that a safe and easy way to dial down a dosage is to have the patient periodically skip a dose). Also, “it is more convenient to prescribe 400 mg daily rather than calculate an exact dosage,” Dr. Koppikar said in an interview. In addition, rheumatologists may be unaware that the prevalence of retinopathy in patients on HCQ is fairly common (about 8% in one large recent study), assessment for risk factors that heighten sensitivity to the drug isn’t always done, and appointments for retinal screening can fall through the cracks.

“It behooves rheumatologists to adopt the [HCQ] recommendations of the American Academy of Ophthalmology [AAO] because there is more toxicity than we previously appreciated,” he added. A new version of the AAO’s recommendations came out in March 2016.

The Committee on Rheumatologic Care of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has regularly updated the ACR’s position statement on screening for HCQ retinopathy and appropriate dosages, with the most recent version out in August 2016. The August statement “is very similar” to the AAO’s 2016 recommendations, said Vinicius Domingues, MD, a member of the committee and an ACR spokesman for the revision. The ACR statement acknowledges and cites the AAO 2016 recommendations.

The ACR’s 2016 statement also does not fully endorse the AAO’s 2016 firm statement that “all patients using HCQ keep daily dosage less than 5.0 mg/kg real weight,” aside from “rare instances” when a higher dosage is needed to treat a “life-threatening disease.”

The ACR 2016 statement goes on to note that other authors have recommended a dosage of 6.5 mg/kg of actual body weight but capped at 400 mg/day and adjusted for renal insufficiency, and the ACR statement stops short of specifying which dosage strategy it recommends.

“The AAO recommendations are much more definitive and state more specifically what screening is recommended and what is a safe dosage,” commented Dr. Rosenbaum.

Dr. Domingues agreed that rheumatologist compliance with HCQ best practices has been spotty.

“In the past few years, more studies have used new ways to detect macular abnormalities and have identified a higher-than-expected incidence of maculopathy. Through lectures, CME, and articles, rheumatologists have received a tremendous amount of information with regard to screening and preventing retinal toxicity,” he said in an interview. “There are still gaps, and some rheumatologists still prescribe HCQ without taking into consideration the patient’s weight.”

That was a key finding in the poster presented at the Canadian Rheumatology Association by Dr. Koppikar and his collaborator on the study, Henry Averns, MD. The 100 patients assessed through the nine-clinic audit process averaged 58 years old, 81% were women, and patients had been taking HCQ for an average of just over 6 years, primarily for rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Nearly two-thirds had a high risk for retinal toxicity. Based on the 2011 recommendations from the AAO and ACR, 17% of the patients were receiving an HCQ overdose that was more than 10% above the recommended dosage, and another 13% received a smaller overdose. If the 2016 dosage guidelines were applied, the extent of overdosing might be even greater, Dr. Koppikar said.

Dr. Koppikar and Dr. Averns said they believe that one way to address HCQ overdosing is by giving clinicians a dosing chart to easily find the right dosage for a patient’s weight. They have distributed these charts to the practices they audited and plan to do a follow-up audit to measure the effect of the intervention on HCQ prescribing.

Results from the initial clinical audit showed that “clinicians were not meeting standards, and we needed an intervention [a dosing chart] to implement a change,” Dr. Koppikar said. “Clinical audits are easy to implement, cost effective, and help improve patient care.”

Dr. Koppikar, Dr. Rosenbaum, Dr. Domingues, and Dr. Averns had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A practice audit showed that 30% of rheumatology patients treated with hydroxychloroquine received an excessive dosage.

Data source: An audit of 100 rheumatology patients seen at any of nine rheumatology clinics in Eastern Ontario, Canada.

Disclosures: Dr. Koppikar, Dr. Rosenbaum, Dr. Domingues, and Dr. Averns had no relevant financial disclosures.

High Lead Levels From Old Bullet Fragments

Bullets and bullet fragments are not always removed if they don’t threaten the injured person’s life. But “retained” bullet fragments (RBFs) can lead to nonspecific symptoms of lead toxicity years later, such as, fatigue, abdominal pain, and memory loss.

Routine testing of adults with RBFs is infrequent, the CDC says. Usually, testing for blood levels of lead is done to monitor occupational exposure. But the number of people with RBFs who have toxic blood lead levels (BLLs) may be higher than thought. At BLLs ≥ 10 µg/dL, hypertension, kidney dysfunction, possible subclinical neurocognitive deficits, and adverse reproductive outcomes have been documented.

Related: The Long Legacy of Agent Orange

CDC researchers analyzed data from 41 states for 145,811 adults with elevated BLLs from all causes, reported by the Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance program from 2003 to 2012. Of those reported cases, 349 had levels ≥ 80 µg/dL. RBF-associated cases accounted for 0.3% of adults with elevated BLLs, but 4.9% of adults with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL. The maximum recorded RBF-associated BLL was 306 µg/dL. Further, RBF-associated cases were “overrepresented” among people with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL: 3.7%, compared with 0.2% of people without RBF-related elevated lead levels.

As of 2004, the researchers say, < 100 cases of lead toxicity caused by RBFs had been reported in the medical literature. They advise asking any patient who has elevated BLLs with an unknown lead exposure source about RBFs. A low index of suspicion could delay diagnosis or even contribute to an incorrect diagnosis.

Related: Cutting Down on Dialysis-Related Infections

Moreover, BLLs can fluctuate in people with RBFs, they note. A patient with a low BLL at the time of testing can have an increase in BLL and become symptomatic when RBFs migrate, such as into a joint space. The CDC researchers suggest baseline and intermittent BLL tests for people with a history of RBFs.

Bullets and bullet fragments are not always removed if they don’t threaten the injured person’s life. But “retained” bullet fragments (RBFs) can lead to nonspecific symptoms of lead toxicity years later, such as, fatigue, abdominal pain, and memory loss.

Routine testing of adults with RBFs is infrequent, the CDC says. Usually, testing for blood levels of lead is done to monitor occupational exposure. But the number of people with RBFs who have toxic blood lead levels (BLLs) may be higher than thought. At BLLs ≥ 10 µg/dL, hypertension, kidney dysfunction, possible subclinical neurocognitive deficits, and adverse reproductive outcomes have been documented.

Related: The Long Legacy of Agent Orange

CDC researchers analyzed data from 41 states for 145,811 adults with elevated BLLs from all causes, reported by the Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance program from 2003 to 2012. Of those reported cases, 349 had levels ≥ 80 µg/dL. RBF-associated cases accounted for 0.3% of adults with elevated BLLs, but 4.9% of adults with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL. The maximum recorded RBF-associated BLL was 306 µg/dL. Further, RBF-associated cases were “overrepresented” among people with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL: 3.7%, compared with 0.2% of people without RBF-related elevated lead levels.

As of 2004, the researchers say, < 100 cases of lead toxicity caused by RBFs had been reported in the medical literature. They advise asking any patient who has elevated BLLs with an unknown lead exposure source about RBFs. A low index of suspicion could delay diagnosis or even contribute to an incorrect diagnosis.

Related: Cutting Down on Dialysis-Related Infections

Moreover, BLLs can fluctuate in people with RBFs, they note. A patient with a low BLL at the time of testing can have an increase in BLL and become symptomatic when RBFs migrate, such as into a joint space. The CDC researchers suggest baseline and intermittent BLL tests for people with a history of RBFs.

Bullets and bullet fragments are not always removed if they don’t threaten the injured person’s life. But “retained” bullet fragments (RBFs) can lead to nonspecific symptoms of lead toxicity years later, such as, fatigue, abdominal pain, and memory loss.

Routine testing of adults with RBFs is infrequent, the CDC says. Usually, testing for blood levels of lead is done to monitor occupational exposure. But the number of people with RBFs who have toxic blood lead levels (BLLs) may be higher than thought. At BLLs ≥ 10 µg/dL, hypertension, kidney dysfunction, possible subclinical neurocognitive deficits, and adverse reproductive outcomes have been documented.

Related: The Long Legacy of Agent Orange

CDC researchers analyzed data from 41 states for 145,811 adults with elevated BLLs from all causes, reported by the Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance program from 2003 to 2012. Of those reported cases, 349 had levels ≥ 80 µg/dL. RBF-associated cases accounted for 0.3% of adults with elevated BLLs, but 4.9% of adults with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL. The maximum recorded RBF-associated BLL was 306 µg/dL. Further, RBF-associated cases were “overrepresented” among people with BLLs ≥ 80 µg/dL: 3.7%, compared with 0.2% of people without RBF-related elevated lead levels.

As of 2004, the researchers say, < 100 cases of lead toxicity caused by RBFs had been reported in the medical literature. They advise asking any patient who has elevated BLLs with an unknown lead exposure source about RBFs. A low index of suspicion could delay diagnosis or even contribute to an incorrect diagnosis.

Related: Cutting Down on Dialysis-Related Infections

Moreover, BLLs can fluctuate in people with RBFs, they note. A patient with a low BLL at the time of testing can have an increase in BLL and become symptomatic when RBFs migrate, such as into a joint space. The CDC researchers suggest baseline and intermittent BLL tests for people with a history of RBFs.

Survey: Patients largely unaware of docs’ industry ties

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

Genetic variants linked to HSCT outcomes in ALL

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a genome-wide association study suggest that several genetic variants are associated with outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Investigators identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ALL patients and their unrelated donors that were associated with disease-related death or progression-free survival (PFS) within 1 year of HSCT.

“We believe that these findings will lead to a better understanding of the biology of this disease,” said investigator Theresa Hahn, PhD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York.

“Additionally, we expect that this work will eventually help clinical teams to identify unrelated donors with genotypes that yield better survival in transplant patients and enhance the chances for successful blood and marrow transplants.”

Dr Hahn presented this work as a “Best Abstract” at the 2017 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 1).

For this study, she and her colleagues analyzed data on patients treated at more than 150 US transplant centers between 2000 and 2011. The investigators evaluated data on more than 3000 patients with acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndromes, but Dr Hahn only presented findings in the ALL patients and their donors.

The patients and donors were divided into 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 included 483 ALL patients who underwent HSCT from 2000 to 2008 and 466 unrelated donors who were a 10/10 HLA match for the patients.

Cohort 2 included 94 ALL patients who received a transplant from a 10/10 HLA-matched donor between 2009 and 2011 or from an 8/8 HLA-matched donor between 2000 and 2011. There were 92 donors in this cohort.

The investigators sequenced blood samples from the recipients and donors to identify SNPs. The SNPs were then measured for association with disease-related death and PFS using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for recipient age, disease status at HSCT (early, intermediate, or advanced), graft source (blood or marrow), and year of transplant.

SNPs in donors

The top 2 SNPs in donors that were associated with a significant increase in disease-related death were:

- rs79503405 in LRP2 on chromosome 2.

- rs77618918 in ASIC2 on chromosome 17.

Dr Hahn noted that rs79503405 is in complete linkage disequilibrium (r2=1.0) with a genotyped missense variant (rs17848149) and a synonymous coding variant (rs35114151) in LRP2.

She also pointed out that the other top SNP (rs77618918) associated with disease-related death is not in linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs of functional importance, so the significance of this SNP is unknown.

There were no SNPs in donors that were significantly associated with PFS.

SNPs in recipients

In HSCT recipients, there were 3 linked variants in NRG1 on chromosome 8 (rs79853417, rs6990973, and rs145488394) that were significantly associated with disease-related death.

Another SNP (rs60640657) on chromosome 2 (CTNNA3/LOC101928961/LRRTM3) was also significantly associated with ALL-related death.

In addition, Dr Hahn and her colleagues found that 1 region in recipient genomes contains multiple variants (rs113263921 and others) associated with PFS. The SNPs are located on chromosome 3 in MLH1 and TRANK1.

“The donor and recipient genetic variants contributed independently to death due to ALL,” Dr Hahn said in closing. “Genetic variants for PFS do not overlap with death due to ALL, and this is probably due to the inclusion of both non-fatal disease progression as well as transplant-related mortality in the definition of PFS.”

“Constitutional genetic variants in recipients and donors increase the risk of death due to ALL, and they warrant further study into the impact of these genes on disease and transplant-related biology.” ![]()

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a genome-wide association study suggest that several genetic variants are associated with outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Investigators identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ALL patients and their unrelated donors that were associated with disease-related death or progression-free survival (PFS) within 1 year of HSCT.

“We believe that these findings will lead to a better understanding of the biology of this disease,” said investigator Theresa Hahn, PhD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York.

“Additionally, we expect that this work will eventually help clinical teams to identify unrelated donors with genotypes that yield better survival in transplant patients and enhance the chances for successful blood and marrow transplants.”

Dr Hahn presented this work as a “Best Abstract” at the 2017 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 1).

For this study, she and her colleagues analyzed data on patients treated at more than 150 US transplant centers between 2000 and 2011. The investigators evaluated data on more than 3000 patients with acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndromes, but Dr Hahn only presented findings in the ALL patients and their donors.

The patients and donors were divided into 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 included 483 ALL patients who underwent HSCT from 2000 to 2008 and 466 unrelated donors who were a 10/10 HLA match for the patients.

Cohort 2 included 94 ALL patients who received a transplant from a 10/10 HLA-matched donor between 2009 and 2011 or from an 8/8 HLA-matched donor between 2000 and 2011. There were 92 donors in this cohort.

The investigators sequenced blood samples from the recipients and donors to identify SNPs. The SNPs were then measured for association with disease-related death and PFS using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for recipient age, disease status at HSCT (early, intermediate, or advanced), graft source (blood or marrow), and year of transplant.

SNPs in donors

The top 2 SNPs in donors that were associated with a significant increase in disease-related death were:

- rs79503405 in LRP2 on chromosome 2.

- rs77618918 in ASIC2 on chromosome 17.

Dr Hahn noted that rs79503405 is in complete linkage disequilibrium (r2=1.0) with a genotyped missense variant (rs17848149) and a synonymous coding variant (rs35114151) in LRP2.

She also pointed out that the other top SNP (rs77618918) associated with disease-related death is not in linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs of functional importance, so the significance of this SNP is unknown.

There were no SNPs in donors that were significantly associated with PFS.

SNPs in recipients

In HSCT recipients, there were 3 linked variants in NRG1 on chromosome 8 (rs79853417, rs6990973, and rs145488394) that were significantly associated with disease-related death.

Another SNP (rs60640657) on chromosome 2 (CTNNA3/LOC101928961/LRRTM3) was also significantly associated with ALL-related death.

In addition, Dr Hahn and her colleagues found that 1 region in recipient genomes contains multiple variants (rs113263921 and others) associated with PFS. The SNPs are located on chromosome 3 in MLH1 and TRANK1.

“The donor and recipient genetic variants contributed independently to death due to ALL,” Dr Hahn said in closing. “Genetic variants for PFS do not overlap with death due to ALL, and this is probably due to the inclusion of both non-fatal disease progression as well as transplant-related mortality in the definition of PFS.”

“Constitutional genetic variants in recipients and donors increase the risk of death due to ALL, and they warrant further study into the impact of these genes on disease and transplant-related biology.” ![]()

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a genome-wide association study suggest that several genetic variants are associated with outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Investigators identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ALL patients and their unrelated donors that were associated with disease-related death or progression-free survival (PFS) within 1 year of HSCT.

“We believe that these findings will lead to a better understanding of the biology of this disease,” said investigator Theresa Hahn, PhD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York.

“Additionally, we expect that this work will eventually help clinical teams to identify unrelated donors with genotypes that yield better survival in transplant patients and enhance the chances for successful blood and marrow transplants.”

Dr Hahn presented this work as a “Best Abstract” at the 2017 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 1).

For this study, she and her colleagues analyzed data on patients treated at more than 150 US transplant centers between 2000 and 2011. The investigators evaluated data on more than 3000 patients with acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndromes, but Dr Hahn only presented findings in the ALL patients and their donors.

The patients and donors were divided into 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 included 483 ALL patients who underwent HSCT from 2000 to 2008 and 466 unrelated donors who were a 10/10 HLA match for the patients.

Cohort 2 included 94 ALL patients who received a transplant from a 10/10 HLA-matched donor between 2009 and 2011 or from an 8/8 HLA-matched donor between 2000 and 2011. There were 92 donors in this cohort.

The investigators sequenced blood samples from the recipients and donors to identify SNPs. The SNPs were then measured for association with disease-related death and PFS using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for recipient age, disease status at HSCT (early, intermediate, or advanced), graft source (blood or marrow), and year of transplant.

SNPs in donors

The top 2 SNPs in donors that were associated with a significant increase in disease-related death were:

- rs79503405 in LRP2 on chromosome 2.

- rs77618918 in ASIC2 on chromosome 17.

Dr Hahn noted that rs79503405 is in complete linkage disequilibrium (r2=1.0) with a genotyped missense variant (rs17848149) and a synonymous coding variant (rs35114151) in LRP2.

She also pointed out that the other top SNP (rs77618918) associated with disease-related death is not in linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs of functional importance, so the significance of this SNP is unknown.

There were no SNPs in donors that were significantly associated with PFS.

SNPs in recipients

In HSCT recipients, there were 3 linked variants in NRG1 on chromosome 8 (rs79853417, rs6990973, and rs145488394) that were significantly associated with disease-related death.

Another SNP (rs60640657) on chromosome 2 (CTNNA3/LOC101928961/LRRTM3) was also significantly associated with ALL-related death.

In addition, Dr Hahn and her colleagues found that 1 region in recipient genomes contains multiple variants (rs113263921 and others) associated with PFS. The SNPs are located on chromosome 3 in MLH1 and TRANK1.

“The donor and recipient genetic variants contributed independently to death due to ALL,” Dr Hahn said in closing. “Genetic variants for PFS do not overlap with death due to ALL, and this is probably due to the inclusion of both non-fatal disease progression as well as transplant-related mortality in the definition of PFS.”

“Constitutional genetic variants in recipients and donors increase the risk of death due to ALL, and they warrant further study into the impact of these genes on disease and transplant-related biology.” ![]()

Combo prolongs OS in relapsed/refractory MM

NEW DEHLI—A 2-drug combination previously shown to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM) can prolong overall survival (OS) as well, according to researchers.

Updated results of the phase 3 ENDEAVOR trial showed that patients who received treatment with carfilzomib and dexamethasone had a 7.6-month benefit in median OS when compared to patients who received bortezomib and dexamethasone.

Previous results from this trial showed a 9.3-month benefit in median PFS with carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

“Based on these data, we now know that [carfilzomib] not only significantly extended progression-free survival compared to [bortezomib] but also overall survival, making it a clinically meaningful advance in the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said Meletios A. Dimopoulos, MD, of the University of Athens in Greece.