User login

What’s Eating You? Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum)

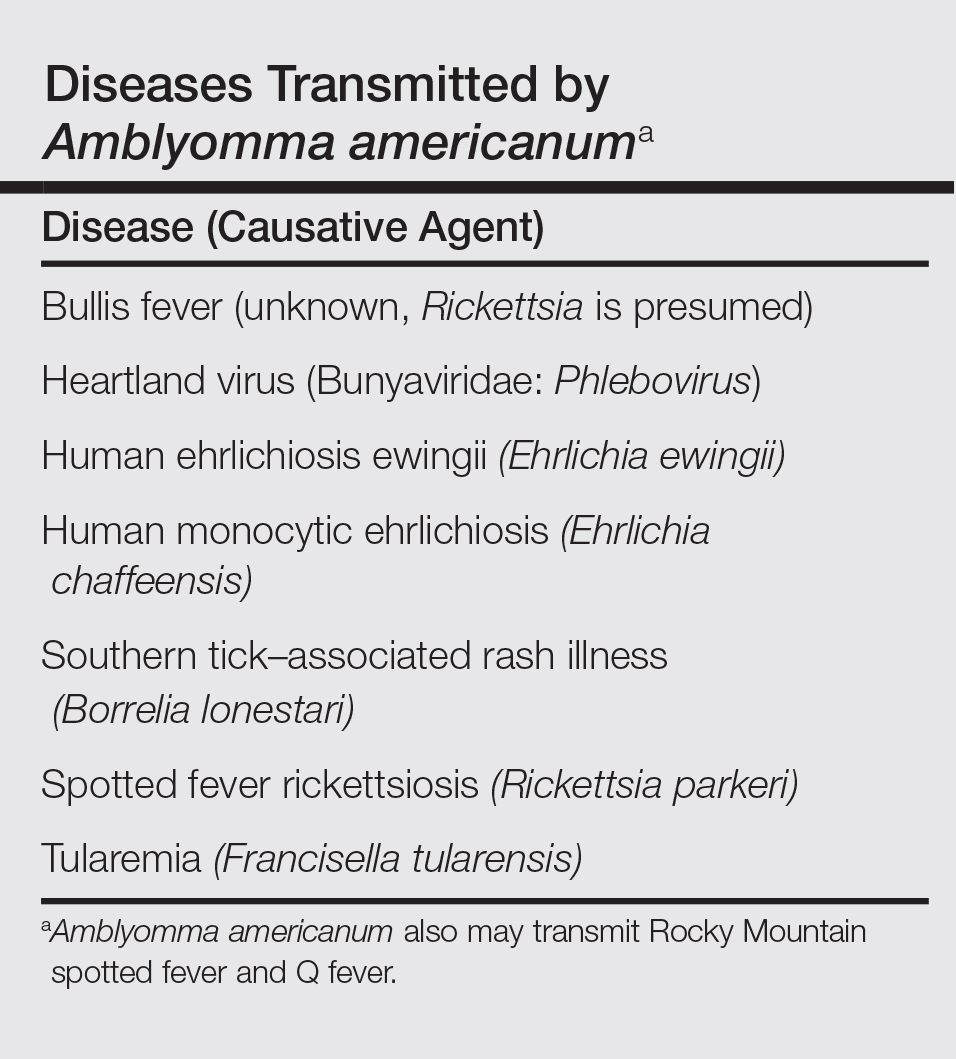

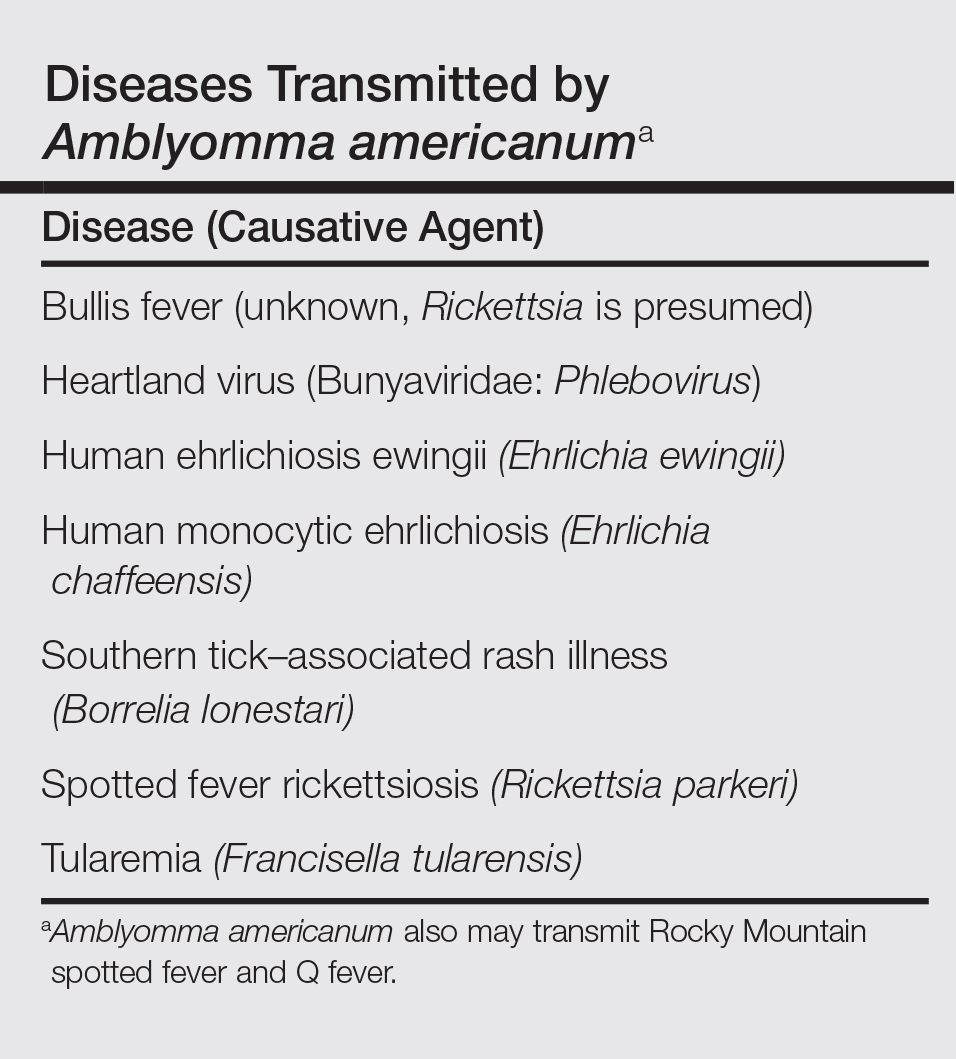

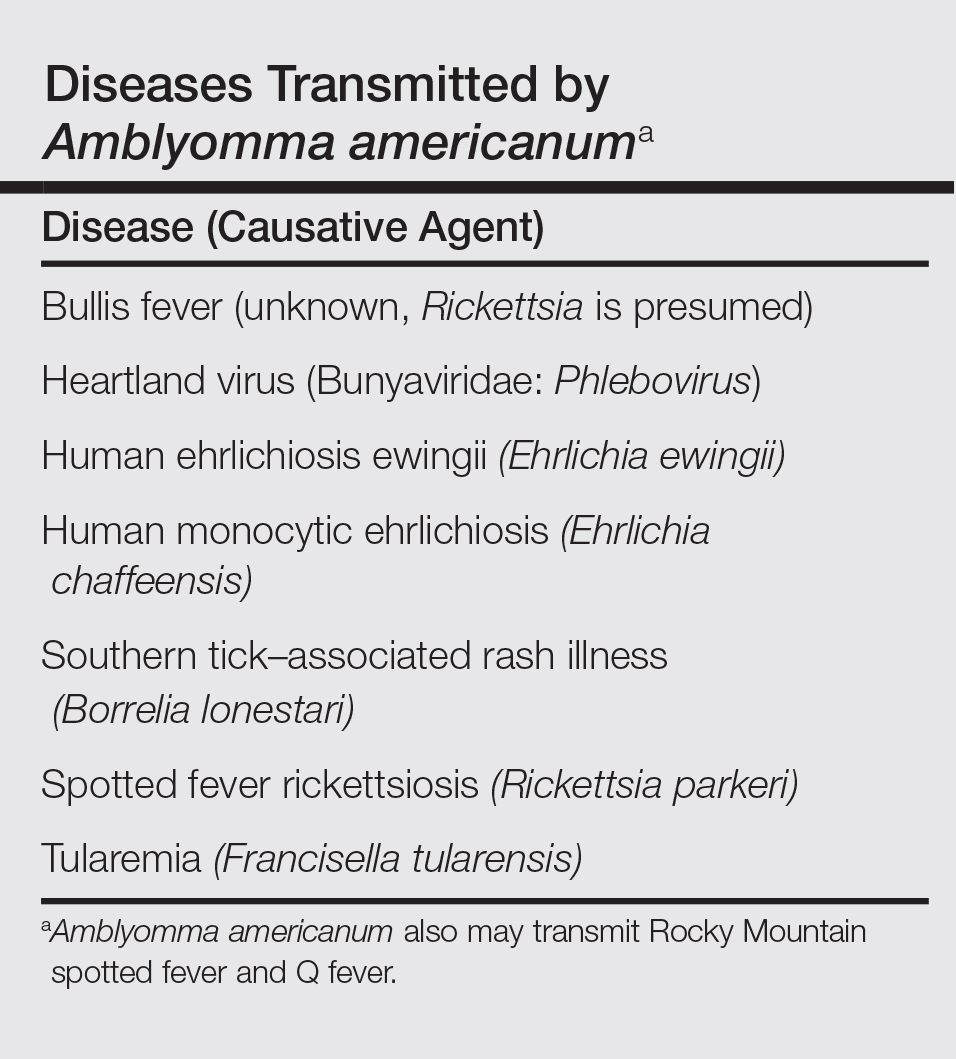

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is distributed throughout much of the eastern United States. It serves as a vector for species of Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Borrelia that are an important cause of tick-borne illness (Table). In addition, the bite of the lone star tick can cause impressive local and systemic reactions. Delayed anaphylaxis to ingestion of red meat has been attributed to the bite of A americanum.1 Herein, we discuss human disease associated with the lone star tick as well as potential tick-control measures.

Tick Characteristics

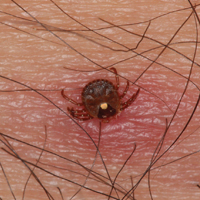

Lone star ticks are characterized by long anterior mouthparts and an ornate scutum (hard dorsal plate). Widely spaced eyes and posterior festoons also are present. In contrast to some other ticks, adanal plates are absent on the ventral surface in male lone star ticks. Amblyomma americanum demonstrates a single white spot on the female’s scutum (Figure 1). The male has inverted horseshoe markings on the posterior scutum. The female’s scutum often covers only a portion of the body to allow room for engorgement.

Patients usually become aware of tick bites while the tick is still attached to the skin, which provides the physician with an opportunity to identify the tick and discuss tick-control measures as well as symptoms of tick-borne disease. Once the tick has been removed, delayed-type hypersensitivity to the tick antigens continues at the attachment site. Erythema and pruritus can be dramatic. Nodules with a pseudolymphomatous histology can occur. Milder reactions respond to application of topical corticosteroids. More intense reactions may require intralesional corticosteroid injection or even surgical excision.

Most hard ticks have a 3-host life cycle, meaning they attach for one long blood meal during each phase of the life cycle. Because they search for a new host for each blood meal, they are efficient disease vectors. The larval ticks, so-called seed ticks, have 6 legs and feed on small animals. Nymphs and adults feed on larger animals. Nymphs resemble small adult ticks with 8 legs but are sexually immature.

Distribution

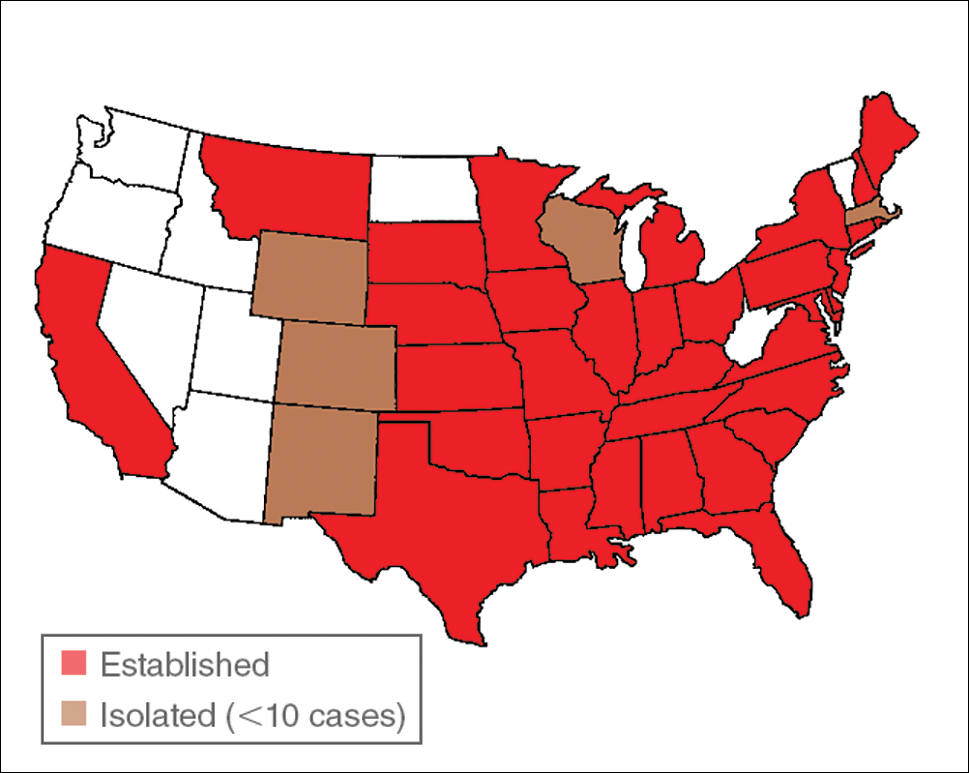

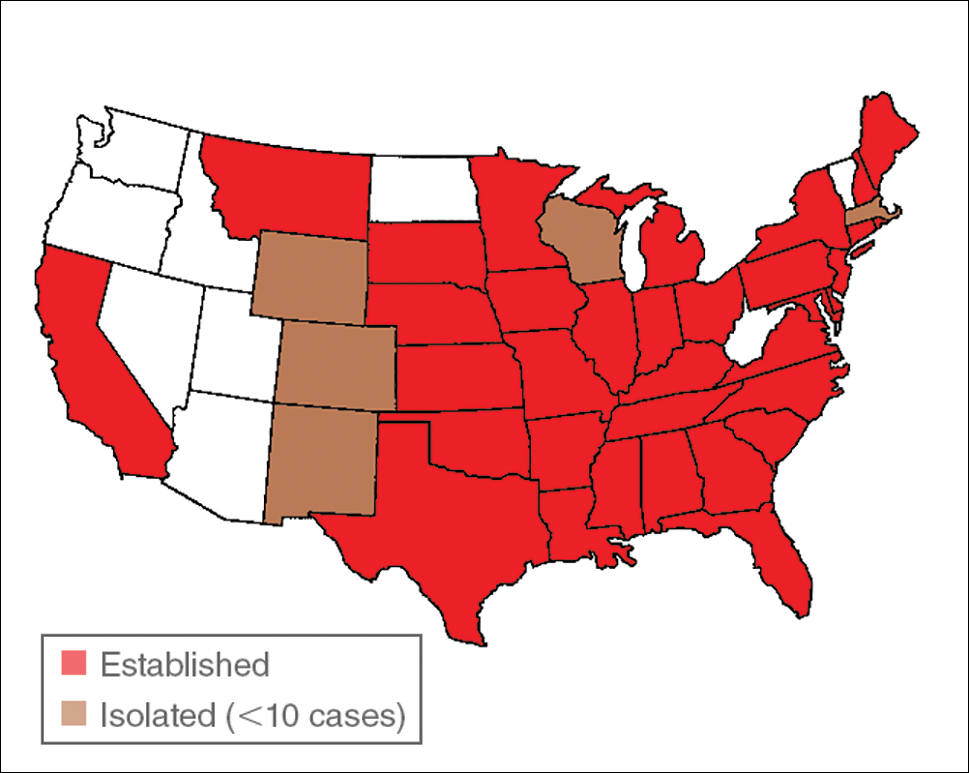

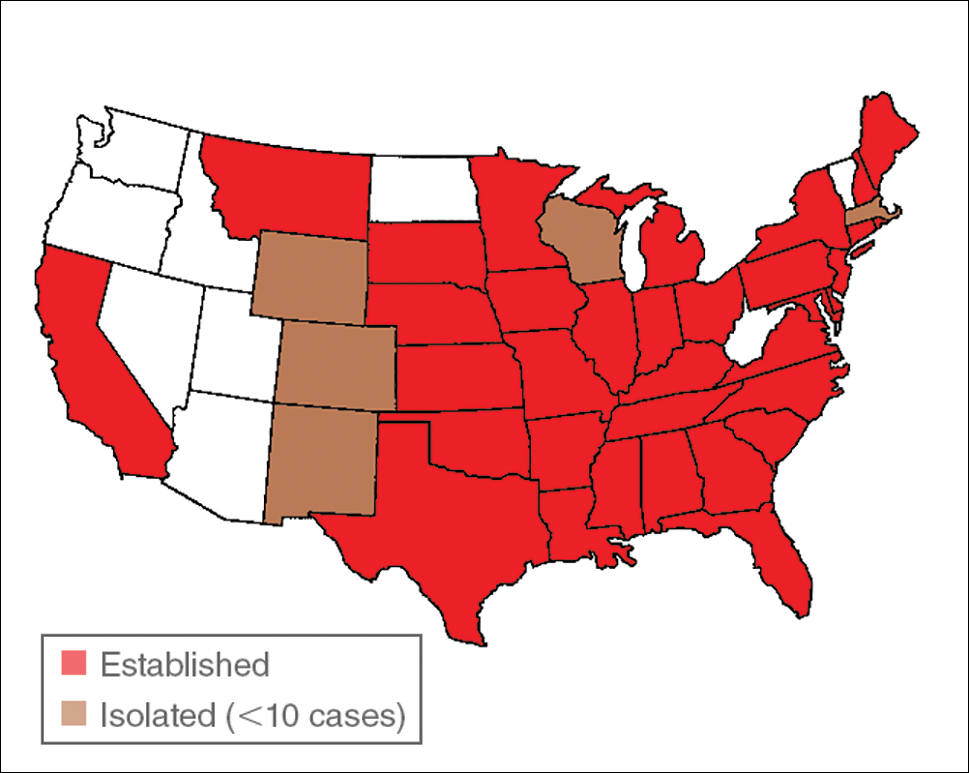

Amblyomma americanum has a wide distribution in the United States from Texas to Iowa and as far north as Maine (Figure 2).2 Tick attachments often are seen in individuals who work outdoors, especially in areas where new commercial or residential development disrupts the environment and the tick’s usual hosts move out of the area. Hungry ticks are left behind in search of a host.

Disease Transmission

Lone star ticks have been implicated as vectors of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME),3 which has been documented from the mid-Atlantic to south-central United States. It may present as a somewhat milder Rocky Mountain spotted fever–like illness with fever and headache or as a life-threatening systemic illness with organ failure. Prompt diagnosis and treatment with a tetracycline has been correlated with a better prognosis.4 Immunofluorescent antibody testing and polymerase chain reaction can be used to establish the diagnosis.5 Two tick species—A americanum and Dermacentor variabilis—have been implicated as vectors, but A americanum appears to be the major vector.6,7

The lone star tick also is a vector for Erlichia ewingii, the cause of human ehrlichiosis ewingii. Human ehrlichiosis ewingii is a rare disease that presents similar to HME, with most reported cases occurring in immunocompromised hosts.8

A novel member of the Phlebovirus genus, the Heartland virus, was first described in 2 Missouri farmers who presented with symptoms similar to HME but did not respond to doxycycline treatment.9 The virus has since been isolated from A americanum adult ticks, implicating them as the major vectors of the disease.10

Rickettsia parkeri, a cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis, is responsible for an eschar-associated illness in affected individuals.11 The organism has been detected in A americanum ticks collected from the wild. Experiments show the tick is capable of transmitting R parkeri to animals in the laboratory. It is unclear, however, what role A americanum plays in the natural transmission of the disease.12

In Missouri, strains of Borrelia have been isolated from A americanum ticks that feed on cottontail rabbits, but it seems unlikely that the tick plays any role in transmission of true Lyme disease13,14; Borrelia has been shown to have poor survival in the saliva of A americanum beyond 24 hours.15 Southern tick–associated rash illness is a Lyme disease–like illness with several reported cases due to A americanum.16 Patients generally present with an erythema migrans–like rash and may have headache, fever, arthralgia, or myalgia.16 The causative organism remains unclear, though Borrelia lonestari has been implicated.17 Lone star ticks also transmit tularemia and may transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Q fever.13

Bullis fever (first reported at Camp Bullis near San Antonio, Texas) affected huge numbers of military personnel from 1942 to 1943.18 The causative organism appears to be rickettsial. During one outbreak of Bullis fever, it was noted that A americanum was so numerous that more than 4000 adult ticks were collected under a single juniper tree and more than 1000 ticks were removed from a single soldier who sat in a thicket for 2 hours.12 No cases of Bullis fever have been reported in recent years,12 which probably relates to the introduction of fire ants.

Disease Hosts

At Little Rock Air Force Base in Arkansas, A americanum has been a source of Ehrlichia infection. During one outbreak, deer in the area were found to have as many as 2550 ticks per ear,19 which demonstrates the magnitude of tick infestation in some areas of the United States. Tick infestation is not merely of concern to the US military. Ticks are ubiquitous and can be found on neatly trimmed suburban lawns as well as in rough thickets.

More recently, bites from A americanum have been found to induce allergies to red meat in some patients.1 IgE antibodies directed against galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha gal) have been implicated as the cause of this reaction. These antibodies cause delayed-onset anaphylaxis occurring 3 to 6 hours after ingestion of red meat. Tick bites appear to be the most important and perhaps the only cause of IgE antibodies to alpha gal in the United States.1

Wild white-tailed deer serve as reservoir hosts for several diseases transmitted by A americanum, including HME, human ehrlichiosis ewingii, and Southern tick–associated rash illness.12,20 Communities located close to wildlife reserves may have higher rates of infection.21 Application of acaricides to corn contained in deer feeders has been shown to be an effective method of decreasing local tick populations, which is a potential method for disease control in at-risk areas, though it is costly and time consuming.22

Tick-Control Measures

Hard ticks produce little urine. Instead, excess water is eliminated via salivation back into the host. Loss of water also occurs through spiracles. Absorption of water from the atmosphere is important for the tick to maintain hydration. The tick produces intensely hygroscopic saliva that absorbs water from surrounding moist air. The humidified saliva is then reingested by the tick. In hot climates, ticks are prone to dehydration unless they can find a source of moist air, usually within a layer of leaf debris.23 When the leaf debris is stirred by a human walking through the area, the tick can make contact with the human. Therefore, removal of leaf debris is a critical part of tick-control efforts, as it reduces tick numbers by means of dehydration. Tick eggs also require sufficient humidity to hatch. Leaf removal increases the effectiveness of insecticide applications, which would otherwise do little harm to the ticks below if sprayed on top of leaf debris.

Some lone star ticks attach to birds and disseminate widely. Attachments to animal hosts with long-range migration patterns complicate tick-control efforts.24 Animal migration may contribute to the spread of disease from one geographic region to another.

Imported fire ants are voracious eaters that gather and consume ticks eggs. Fire ants provide an excellent natural means of tick control. Tick numbers in places such as Camp Bullis have declined dramatically since the introduction of imported fire ants.25

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Tick bites and red meat allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:354-359.

- Springer YP, Eisen L, Beati L, et al. Spatial distribution of counties in the continental United States with records of occurrence of Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51:342-351.

- Yu X, Piesman JF, Olson JG, et al. Geographic distribution of different genetic types of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:679-680.

- Dumler JS, Bakken JS. Human ehrlichiosis: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. An Rev Med. 1998;49:201-213.

- Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, et al. Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 1):S45-S51.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DE, et al. Natural history of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Ricketsiales: Ehrlichiea) in the piedmont physiographic province of Georgia. J Parasitol. 1997;83:887-894.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human ehrlichiosis—Maryland, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:798-802.

- Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:261-292.

- McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:834-841.

- Savage HM, Godsey MS Jr, Panella NA, et al. Surveillance for heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) in Missouri during 2013: first detection of virus in adults of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) [published online March 30, 2016]. J Med Entomol. pii:tjw028.

- Cragun WC, Bartlett BL, Ellis MW, et al. The expanding spectrum of eschar-associated rickettsioses in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:641-648.

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, et al. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:805-811.

- Goddard J, Varela-Stokes AS. Role of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.) in human and animal diseases. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:1-12.

- Oliver JH, Kollars TM, Chandler FW, et al. First isolation and cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from Missouri. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1-5.

- Ledin KE, Zeidner NS, Ribeiro JM, et al. Borreliacidal activity of saliva of the tick Amblyomma americanum. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:90-95.

- Feder HM Jr, Hoss DM, Zemel L, et al. Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) in the North: STARI following a tick bite in Long Island, New York. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e142-e146.

- Varela AS, Luttrell MP, Howerth EW, et al. First culture isolation of Borrelia lonestari, putative agent of southern tick-associated rash illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1163-1169.

- Livesay HR, Pollard M. Laboratory report on a clinical syndrome referred to as “Bullis Fever.” Am J Trop Med. 1943;23:475-479.

- Goddard J. Ticks and tickborne diseases affecting military personnel. US Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine USAFSAM-SR-89-2. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221956.pdf. Published September 1989. Accessed January 19, 2017.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallkneeckt DE, et al. Isolation of Ehrlichia chaffeensis from wild white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) confirms their role as natural reservoir hosts. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1681-1686.

- Standaert SM, Dawson JE, Schaffner W, et al. Ehrlichiosis in a golf-oriented retirement community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:420-425.

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Hung RW, et al. Effectiveness of the 4-Poster passive topical treatment device in the control of Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Jersey. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:389-400.

- Strey OF, Teel PD, Longnecker MT, et al. Survival and water-balance characteristics of unfed Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1996;33:63-73.

- Popham TW, Garris GI, Barre N. Development of a computer model of the population dynamics of Amblyomma variegatum and simulations of eradication strategies for use in the Caribbean. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1996;791:452-465.

- Burns EC, Melancon DG. Effect of important fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) invasion on lone star tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) populations. J Med Entomol. 1977;14:247-249.

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is distributed throughout much of the eastern United States. It serves as a vector for species of Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Borrelia that are an important cause of tick-borne illness (Table). In addition, the bite of the lone star tick can cause impressive local and systemic reactions. Delayed anaphylaxis to ingestion of red meat has been attributed to the bite of A americanum.1 Herein, we discuss human disease associated with the lone star tick as well as potential tick-control measures.

Tick Characteristics

Lone star ticks are characterized by long anterior mouthparts and an ornate scutum (hard dorsal plate). Widely spaced eyes and posterior festoons also are present. In contrast to some other ticks, adanal plates are absent on the ventral surface in male lone star ticks. Amblyomma americanum demonstrates a single white spot on the female’s scutum (Figure 1). The male has inverted horseshoe markings on the posterior scutum. The female’s scutum often covers only a portion of the body to allow room for engorgement.

Patients usually become aware of tick bites while the tick is still attached to the skin, which provides the physician with an opportunity to identify the tick and discuss tick-control measures as well as symptoms of tick-borne disease. Once the tick has been removed, delayed-type hypersensitivity to the tick antigens continues at the attachment site. Erythema and pruritus can be dramatic. Nodules with a pseudolymphomatous histology can occur. Milder reactions respond to application of topical corticosteroids. More intense reactions may require intralesional corticosteroid injection or even surgical excision.

Most hard ticks have a 3-host life cycle, meaning they attach for one long blood meal during each phase of the life cycle. Because they search for a new host for each blood meal, they are efficient disease vectors. The larval ticks, so-called seed ticks, have 6 legs and feed on small animals. Nymphs and adults feed on larger animals. Nymphs resemble small adult ticks with 8 legs but are sexually immature.

Distribution

Amblyomma americanum has a wide distribution in the United States from Texas to Iowa and as far north as Maine (Figure 2).2 Tick attachments often are seen in individuals who work outdoors, especially in areas where new commercial or residential development disrupts the environment and the tick’s usual hosts move out of the area. Hungry ticks are left behind in search of a host.

Disease Transmission

Lone star ticks have been implicated as vectors of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME),3 which has been documented from the mid-Atlantic to south-central United States. It may present as a somewhat milder Rocky Mountain spotted fever–like illness with fever and headache or as a life-threatening systemic illness with organ failure. Prompt diagnosis and treatment with a tetracycline has been correlated with a better prognosis.4 Immunofluorescent antibody testing and polymerase chain reaction can be used to establish the diagnosis.5 Two tick species—A americanum and Dermacentor variabilis—have been implicated as vectors, but A americanum appears to be the major vector.6,7

The lone star tick also is a vector for Erlichia ewingii, the cause of human ehrlichiosis ewingii. Human ehrlichiosis ewingii is a rare disease that presents similar to HME, with most reported cases occurring in immunocompromised hosts.8

A novel member of the Phlebovirus genus, the Heartland virus, was first described in 2 Missouri farmers who presented with symptoms similar to HME but did not respond to doxycycline treatment.9 The virus has since been isolated from A americanum adult ticks, implicating them as the major vectors of the disease.10

Rickettsia parkeri, a cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis, is responsible for an eschar-associated illness in affected individuals.11 The organism has been detected in A americanum ticks collected from the wild. Experiments show the tick is capable of transmitting R parkeri to animals in the laboratory. It is unclear, however, what role A americanum plays in the natural transmission of the disease.12

In Missouri, strains of Borrelia have been isolated from A americanum ticks that feed on cottontail rabbits, but it seems unlikely that the tick plays any role in transmission of true Lyme disease13,14; Borrelia has been shown to have poor survival in the saliva of A americanum beyond 24 hours.15 Southern tick–associated rash illness is a Lyme disease–like illness with several reported cases due to A americanum.16 Patients generally present with an erythema migrans–like rash and may have headache, fever, arthralgia, or myalgia.16 The causative organism remains unclear, though Borrelia lonestari has been implicated.17 Lone star ticks also transmit tularemia and may transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Q fever.13

Bullis fever (first reported at Camp Bullis near San Antonio, Texas) affected huge numbers of military personnel from 1942 to 1943.18 The causative organism appears to be rickettsial. During one outbreak of Bullis fever, it was noted that A americanum was so numerous that more than 4000 adult ticks were collected under a single juniper tree and more than 1000 ticks were removed from a single soldier who sat in a thicket for 2 hours.12 No cases of Bullis fever have been reported in recent years,12 which probably relates to the introduction of fire ants.

Disease Hosts

At Little Rock Air Force Base in Arkansas, A americanum has been a source of Ehrlichia infection. During one outbreak, deer in the area were found to have as many as 2550 ticks per ear,19 which demonstrates the magnitude of tick infestation in some areas of the United States. Tick infestation is not merely of concern to the US military. Ticks are ubiquitous and can be found on neatly trimmed suburban lawns as well as in rough thickets.

More recently, bites from A americanum have been found to induce allergies to red meat in some patients.1 IgE antibodies directed against galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha gal) have been implicated as the cause of this reaction. These antibodies cause delayed-onset anaphylaxis occurring 3 to 6 hours after ingestion of red meat. Tick bites appear to be the most important and perhaps the only cause of IgE antibodies to alpha gal in the United States.1

Wild white-tailed deer serve as reservoir hosts for several diseases transmitted by A americanum, including HME, human ehrlichiosis ewingii, and Southern tick–associated rash illness.12,20 Communities located close to wildlife reserves may have higher rates of infection.21 Application of acaricides to corn contained in deer feeders has been shown to be an effective method of decreasing local tick populations, which is a potential method for disease control in at-risk areas, though it is costly and time consuming.22

Tick-Control Measures

Hard ticks produce little urine. Instead, excess water is eliminated via salivation back into the host. Loss of water also occurs through spiracles. Absorption of water from the atmosphere is important for the tick to maintain hydration. The tick produces intensely hygroscopic saliva that absorbs water from surrounding moist air. The humidified saliva is then reingested by the tick. In hot climates, ticks are prone to dehydration unless they can find a source of moist air, usually within a layer of leaf debris.23 When the leaf debris is stirred by a human walking through the area, the tick can make contact with the human. Therefore, removal of leaf debris is a critical part of tick-control efforts, as it reduces tick numbers by means of dehydration. Tick eggs also require sufficient humidity to hatch. Leaf removal increases the effectiveness of insecticide applications, which would otherwise do little harm to the ticks below if sprayed on top of leaf debris.

Some lone star ticks attach to birds and disseminate widely. Attachments to animal hosts with long-range migration patterns complicate tick-control efforts.24 Animal migration may contribute to the spread of disease from one geographic region to another.

Imported fire ants are voracious eaters that gather and consume ticks eggs. Fire ants provide an excellent natural means of tick control. Tick numbers in places such as Camp Bullis have declined dramatically since the introduction of imported fire ants.25

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is distributed throughout much of the eastern United States. It serves as a vector for species of Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Borrelia that are an important cause of tick-borne illness (Table). In addition, the bite of the lone star tick can cause impressive local and systemic reactions. Delayed anaphylaxis to ingestion of red meat has been attributed to the bite of A americanum.1 Herein, we discuss human disease associated with the lone star tick as well as potential tick-control measures.

Tick Characteristics

Lone star ticks are characterized by long anterior mouthparts and an ornate scutum (hard dorsal plate). Widely spaced eyes and posterior festoons also are present. In contrast to some other ticks, adanal plates are absent on the ventral surface in male lone star ticks. Amblyomma americanum demonstrates a single white spot on the female’s scutum (Figure 1). The male has inverted horseshoe markings on the posterior scutum. The female’s scutum often covers only a portion of the body to allow room for engorgement.

Patients usually become aware of tick bites while the tick is still attached to the skin, which provides the physician with an opportunity to identify the tick and discuss tick-control measures as well as symptoms of tick-borne disease. Once the tick has been removed, delayed-type hypersensitivity to the tick antigens continues at the attachment site. Erythema and pruritus can be dramatic. Nodules with a pseudolymphomatous histology can occur. Milder reactions respond to application of topical corticosteroids. More intense reactions may require intralesional corticosteroid injection or even surgical excision.

Most hard ticks have a 3-host life cycle, meaning they attach for one long blood meal during each phase of the life cycle. Because they search for a new host for each blood meal, they are efficient disease vectors. The larval ticks, so-called seed ticks, have 6 legs and feed on small animals. Nymphs and adults feed on larger animals. Nymphs resemble small adult ticks with 8 legs but are sexually immature.

Distribution

Amblyomma americanum has a wide distribution in the United States from Texas to Iowa and as far north as Maine (Figure 2).2 Tick attachments often are seen in individuals who work outdoors, especially in areas where new commercial or residential development disrupts the environment and the tick’s usual hosts move out of the area. Hungry ticks are left behind in search of a host.

Disease Transmission

Lone star ticks have been implicated as vectors of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME),3 which has been documented from the mid-Atlantic to south-central United States. It may present as a somewhat milder Rocky Mountain spotted fever–like illness with fever and headache or as a life-threatening systemic illness with organ failure. Prompt diagnosis and treatment with a tetracycline has been correlated with a better prognosis.4 Immunofluorescent antibody testing and polymerase chain reaction can be used to establish the diagnosis.5 Two tick species—A americanum and Dermacentor variabilis—have been implicated as vectors, but A americanum appears to be the major vector.6,7

The lone star tick also is a vector for Erlichia ewingii, the cause of human ehrlichiosis ewingii. Human ehrlichiosis ewingii is a rare disease that presents similar to HME, with most reported cases occurring in immunocompromised hosts.8

A novel member of the Phlebovirus genus, the Heartland virus, was first described in 2 Missouri farmers who presented with symptoms similar to HME but did not respond to doxycycline treatment.9 The virus has since been isolated from A americanum adult ticks, implicating them as the major vectors of the disease.10

Rickettsia parkeri, a cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis, is responsible for an eschar-associated illness in affected individuals.11 The organism has been detected in A americanum ticks collected from the wild. Experiments show the tick is capable of transmitting R parkeri to animals in the laboratory. It is unclear, however, what role A americanum plays in the natural transmission of the disease.12

In Missouri, strains of Borrelia have been isolated from A americanum ticks that feed on cottontail rabbits, but it seems unlikely that the tick plays any role in transmission of true Lyme disease13,14; Borrelia has been shown to have poor survival in the saliva of A americanum beyond 24 hours.15 Southern tick–associated rash illness is a Lyme disease–like illness with several reported cases due to A americanum.16 Patients generally present with an erythema migrans–like rash and may have headache, fever, arthralgia, or myalgia.16 The causative organism remains unclear, though Borrelia lonestari has been implicated.17 Lone star ticks also transmit tularemia and may transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Q fever.13

Bullis fever (first reported at Camp Bullis near San Antonio, Texas) affected huge numbers of military personnel from 1942 to 1943.18 The causative organism appears to be rickettsial. During one outbreak of Bullis fever, it was noted that A americanum was so numerous that more than 4000 adult ticks were collected under a single juniper tree and more than 1000 ticks were removed from a single soldier who sat in a thicket for 2 hours.12 No cases of Bullis fever have been reported in recent years,12 which probably relates to the introduction of fire ants.

Disease Hosts

At Little Rock Air Force Base in Arkansas, A americanum has been a source of Ehrlichia infection. During one outbreak, deer in the area were found to have as many as 2550 ticks per ear,19 which demonstrates the magnitude of tick infestation in some areas of the United States. Tick infestation is not merely of concern to the US military. Ticks are ubiquitous and can be found on neatly trimmed suburban lawns as well as in rough thickets.

More recently, bites from A americanum have been found to induce allergies to red meat in some patients.1 IgE antibodies directed against galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha gal) have been implicated as the cause of this reaction. These antibodies cause delayed-onset anaphylaxis occurring 3 to 6 hours after ingestion of red meat. Tick bites appear to be the most important and perhaps the only cause of IgE antibodies to alpha gal in the United States.1

Wild white-tailed deer serve as reservoir hosts for several diseases transmitted by A americanum, including HME, human ehrlichiosis ewingii, and Southern tick–associated rash illness.12,20 Communities located close to wildlife reserves may have higher rates of infection.21 Application of acaricides to corn contained in deer feeders has been shown to be an effective method of decreasing local tick populations, which is a potential method for disease control in at-risk areas, though it is costly and time consuming.22

Tick-Control Measures

Hard ticks produce little urine. Instead, excess water is eliminated via salivation back into the host. Loss of water also occurs through spiracles. Absorption of water from the atmosphere is important for the tick to maintain hydration. The tick produces intensely hygroscopic saliva that absorbs water from surrounding moist air. The humidified saliva is then reingested by the tick. In hot climates, ticks are prone to dehydration unless they can find a source of moist air, usually within a layer of leaf debris.23 When the leaf debris is stirred by a human walking through the area, the tick can make contact with the human. Therefore, removal of leaf debris is a critical part of tick-control efforts, as it reduces tick numbers by means of dehydration. Tick eggs also require sufficient humidity to hatch. Leaf removal increases the effectiveness of insecticide applications, which would otherwise do little harm to the ticks below if sprayed on top of leaf debris.

Some lone star ticks attach to birds and disseminate widely. Attachments to animal hosts with long-range migration patterns complicate tick-control efforts.24 Animal migration may contribute to the spread of disease from one geographic region to another.

Imported fire ants are voracious eaters that gather and consume ticks eggs. Fire ants provide an excellent natural means of tick control. Tick numbers in places such as Camp Bullis have declined dramatically since the introduction of imported fire ants.25

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Tick bites and red meat allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:354-359.

- Springer YP, Eisen L, Beati L, et al. Spatial distribution of counties in the continental United States with records of occurrence of Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51:342-351.

- Yu X, Piesman JF, Olson JG, et al. Geographic distribution of different genetic types of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:679-680.

- Dumler JS, Bakken JS. Human ehrlichiosis: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. An Rev Med. 1998;49:201-213.

- Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, et al. Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 1):S45-S51.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DE, et al. Natural history of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Ricketsiales: Ehrlichiea) in the piedmont physiographic province of Georgia. J Parasitol. 1997;83:887-894.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human ehrlichiosis—Maryland, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:798-802.

- Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:261-292.

- McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:834-841.

- Savage HM, Godsey MS Jr, Panella NA, et al. Surveillance for heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) in Missouri during 2013: first detection of virus in adults of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) [published online March 30, 2016]. J Med Entomol. pii:tjw028.

- Cragun WC, Bartlett BL, Ellis MW, et al. The expanding spectrum of eschar-associated rickettsioses in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:641-648.

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, et al. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:805-811.

- Goddard J, Varela-Stokes AS. Role of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.) in human and animal diseases. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:1-12.

- Oliver JH, Kollars TM, Chandler FW, et al. First isolation and cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from Missouri. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1-5.

- Ledin KE, Zeidner NS, Ribeiro JM, et al. Borreliacidal activity of saliva of the tick Amblyomma americanum. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:90-95.

- Feder HM Jr, Hoss DM, Zemel L, et al. Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) in the North: STARI following a tick bite in Long Island, New York. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e142-e146.

- Varela AS, Luttrell MP, Howerth EW, et al. First culture isolation of Borrelia lonestari, putative agent of southern tick-associated rash illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1163-1169.

- Livesay HR, Pollard M. Laboratory report on a clinical syndrome referred to as “Bullis Fever.” Am J Trop Med. 1943;23:475-479.

- Goddard J. Ticks and tickborne diseases affecting military personnel. US Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine USAFSAM-SR-89-2. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221956.pdf. Published September 1989. Accessed January 19, 2017.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallkneeckt DE, et al. Isolation of Ehrlichia chaffeensis from wild white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) confirms their role as natural reservoir hosts. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1681-1686.

- Standaert SM, Dawson JE, Schaffner W, et al. Ehrlichiosis in a golf-oriented retirement community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:420-425.

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Hung RW, et al. Effectiveness of the 4-Poster passive topical treatment device in the control of Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Jersey. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:389-400.

- Strey OF, Teel PD, Longnecker MT, et al. Survival and water-balance characteristics of unfed Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1996;33:63-73.

- Popham TW, Garris GI, Barre N. Development of a computer model of the population dynamics of Amblyomma variegatum and simulations of eradication strategies for use in the Caribbean. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1996;791:452-465.

- Burns EC, Melancon DG. Effect of important fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) invasion on lone star tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) populations. J Med Entomol. 1977;14:247-249.

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Tick bites and red meat allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:354-359.

- Springer YP, Eisen L, Beati L, et al. Spatial distribution of counties in the continental United States with records of occurrence of Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51:342-351.

- Yu X, Piesman JF, Olson JG, et al. Geographic distribution of different genetic types of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:679-680.

- Dumler JS, Bakken JS. Human ehrlichiosis: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. An Rev Med. 1998;49:201-213.

- Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, et al. Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 1):S45-S51.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallknecht DE, et al. Natural history of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Ricketsiales: Ehrlichiea) in the piedmont physiographic province of Georgia. J Parasitol. 1997;83:887-894.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human ehrlichiosis—Maryland, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:798-802.

- Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:261-292.

- McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:834-841.

- Savage HM, Godsey MS Jr, Panella NA, et al. Surveillance for heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) in Missouri during 2013: first detection of virus in adults of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) [published online March 30, 2016]. J Med Entomol. pii:tjw028.

- Cragun WC, Bartlett BL, Ellis MW, et al. The expanding spectrum of eschar-associated rickettsioses in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:641-648.

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, et al. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:805-811.

- Goddard J, Varela-Stokes AS. Role of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.) in human and animal diseases. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:1-12.

- Oliver JH, Kollars TM, Chandler FW, et al. First isolation and cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from Missouri. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1-5.

- Ledin KE, Zeidner NS, Ribeiro JM, et al. Borreliacidal activity of saliva of the tick Amblyomma americanum. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:90-95.

- Feder HM Jr, Hoss DM, Zemel L, et al. Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) in the North: STARI following a tick bite in Long Island, New York. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e142-e146.

- Varela AS, Luttrell MP, Howerth EW, et al. First culture isolation of Borrelia lonestari, putative agent of southern tick-associated rash illness. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1163-1169.

- Livesay HR, Pollard M. Laboratory report on a clinical syndrome referred to as “Bullis Fever.” Am J Trop Med. 1943;23:475-479.

- Goddard J. Ticks and tickborne diseases affecting military personnel. US Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine USAFSAM-SR-89-2. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221956.pdf. Published September 1989. Accessed January 19, 2017.

- Lockhart JM, Davidson WR, Stallkneeckt DE, et al. Isolation of Ehrlichia chaffeensis from wild white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) confirms their role as natural reservoir hosts. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1681-1686.

- Standaert SM, Dawson JE, Schaffner W, et al. Ehrlichiosis in a golf-oriented retirement community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:420-425.

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Hung RW, et al. Effectiveness of the 4-Poster passive topical treatment device in the control of Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Jersey. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:389-400.

- Strey OF, Teel PD, Longnecker MT, et al. Survival and water-balance characteristics of unfed Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1996;33:63-73.

- Popham TW, Garris GI, Barre N. Development of a computer model of the population dynamics of Amblyomma variegatum and simulations of eradication strategies for use in the Caribbean. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1996;791:452-465.

- Burns EC, Melancon DG. Effect of important fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) invasion on lone star tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) populations. J Med Entomol. 1977;14:247-249.

Practice Points

- Amblyomma americanum (lone star tick) is widely distributed throughout the United States and is an important cause of several tick-borne illnesses.

- Prompt diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne disease improves patient outcomes.

- In some cases, tick bites may cause the human host to develop certain IgE antibodies that result in a delayed-onset anaphylaxis after ingestion of red meat.

Biosimilars in Psoriasis: The Future or Not?

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is “highly similar to an FDA-approved biological product, . . . and has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”1 The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act of 2009 created an expedited pathway for the approval of products shown to be biosimilar to FDA-licensed reference products.2 In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the first biosimilar modeled on infliximab (Remsima [formerly known as CT-P13], Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd) for the same indications as its reference product.3 In 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra (Hospira, a Pfizer Company), an infliximab biosimilar; Erelzi (Sandoz, a Novartis Division), an etanercept biosimilar; and Amjevita (Amgen Inc), an adalimumab biosimilar, all for numerous clinical indications including plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.4-6

There has been a substantial amount of distrust surrounding the biosimilars; however, as the patents for the biologic agents expire, new biosimilars will undoubtedly flood the market. In this article, we provide information that will help dermatologists understand the need for and use of these agents.

Biosimilars Versus Generic Drugs

Small-molecule generics can be made in a process that is relatively inexpensive, reproducible, and able to yield identical products with each lot.7 In contrast, biosimilars are large complex proteins made in living cells. They differ from their reference product because of changes that occur during manufacturing (eg, purification system, posttranslational modifications).7-9 Glycosylation is particularly sensitive to manufacturing and can affect the immunogenicity of the product.9 The impact of manufacturing can be substantial; for example, during phase 3 trials for efalizumab, a change in the manufacturing facility affected pharmacokinetic properties to such a degree that the FDA required a repeat of the trials.10

FDA Guidelines on Biosimilarity

The FDA outlines the following approach to demonstrate biosimilarity.2 The first step is structural characterization to evaluate the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures and posttranslational modifications. The next step utilizes in vivo and/or in vitro functional assays to compare the biosimilar and reference product. The third step is a focus on toxicity and immunogenicity. The fourth step involves clinical studies to study pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy. After the biosimilar has been approved, there must be a system in place to monitor postmarketing safety. If a biosimilar is tested in one patient population (eg, patients with plaque psoriasis), a request can be made to approve the drug for all the conditions that the reference product was approved for, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, even though clinical trials were not performed in all of these patient populations.2 The BPCI Act leaves it up to the FDA to determine how much and what type of data (eg, in vitro, in vivo, clinical) are required.11

Extrapolation and Interchangeability

Once a biosimilar has been approved, 2 questions must be answered: First, can its use be extrapolated to all indications for the reference product? The infliximab biosimilar approved by the European Medicines Agency and the FDA had only been studied in patients with ankylosing spondylitis12 and rheumatoid arthritis,13 yet it was granted all the indications for infliximab, including severe plaque psoriasis.14 As of now, the various regulatory agencies differ on their policies regarding extrapolation. Extrapolation is not automatically bestowed on a biosimilar in the United States but can be requested by the manufacturer.2

Second, can the biosimilar be seamlessly switched with its reference product at the pharmacy level? The BPCI Act allows for the substitution of biosimilars that are deemed interchangeable without notifying the provider, yet individual states ultimately can pass laws regarding this issue.15,16 An interchangeable agent would “produce the same clinical result as the reference product,” and “the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product.”15 Generic drugs are allowed to be substituted without notifying the patient or prescriber16; however, biosimilars that are not deemed interchangeable would require permission from the prescriber before substitution.11

Biosimilars for Psoriasis

In April 2016, an infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra) became the second biosimilar approved by the FDA.4 Inflectra was studied in clinical trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis17 and rheumatoid arthritis,18 and in both trials the biosimilar was found to have similar efficacy and safety profiles to that of the reference product. In August 2016, an etanercept biosimilar (Erelzi) was approved,5 and in September 2016, an adalimumab biosimilar (Amjevita) was approved.6

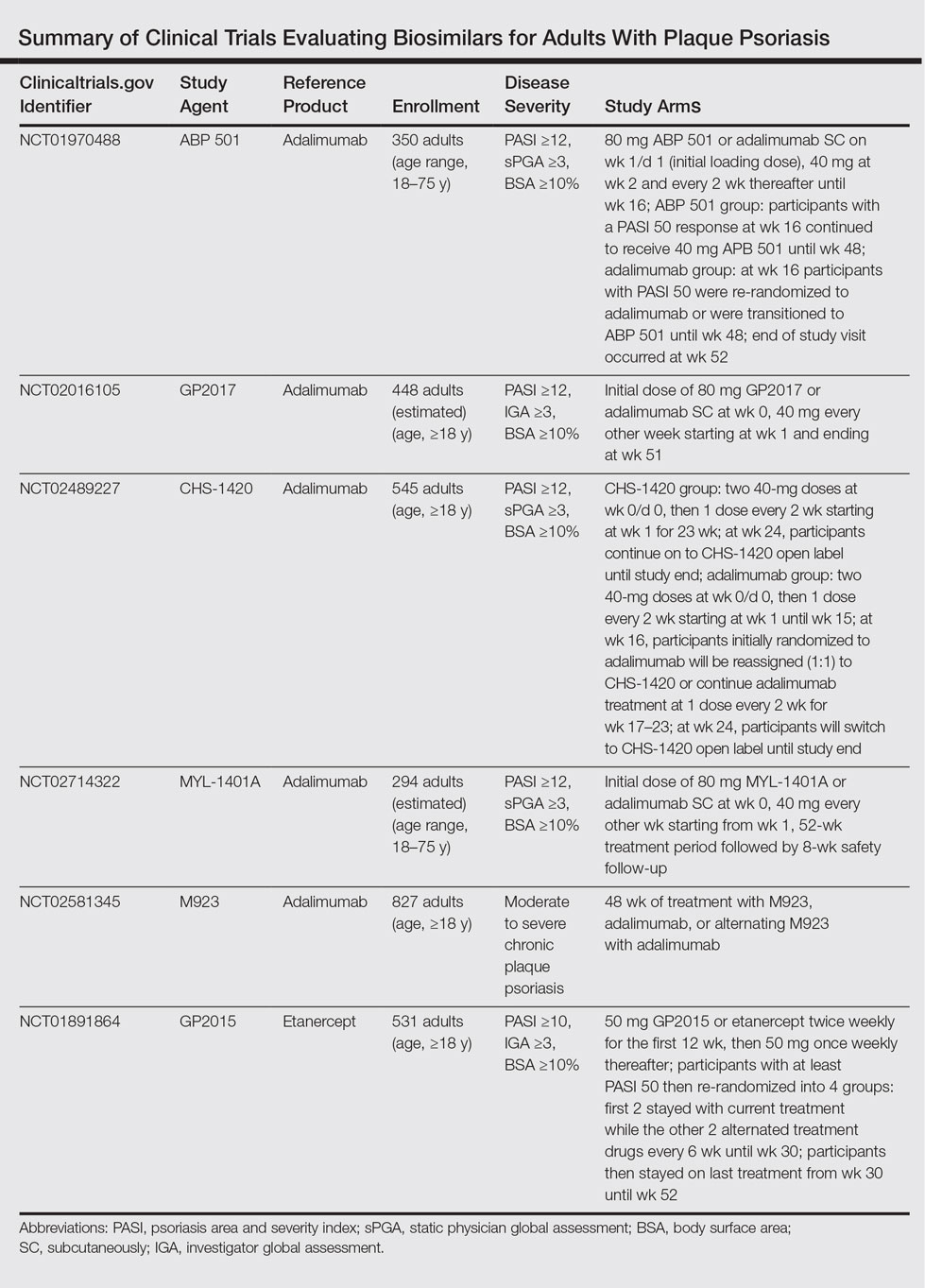

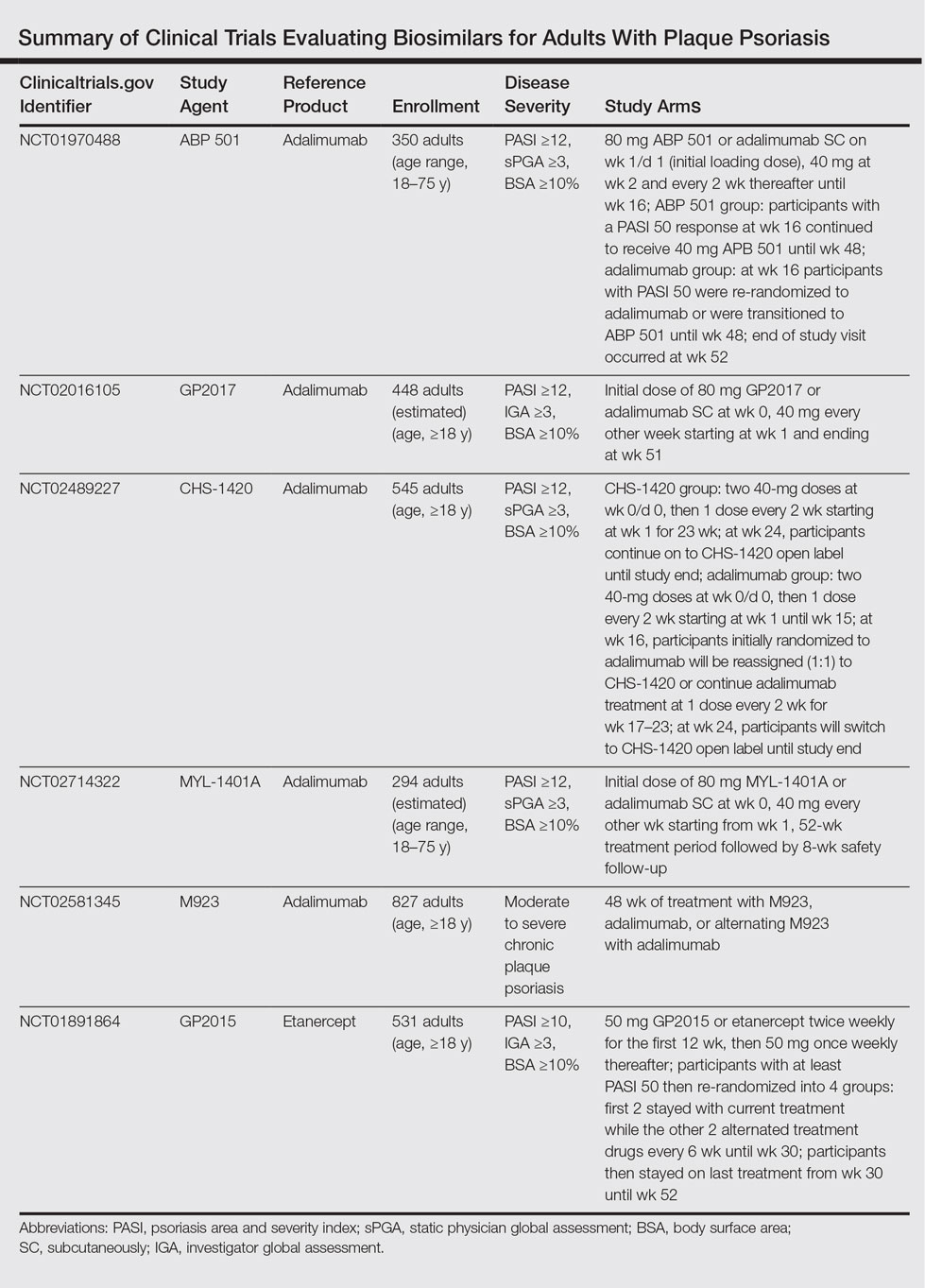

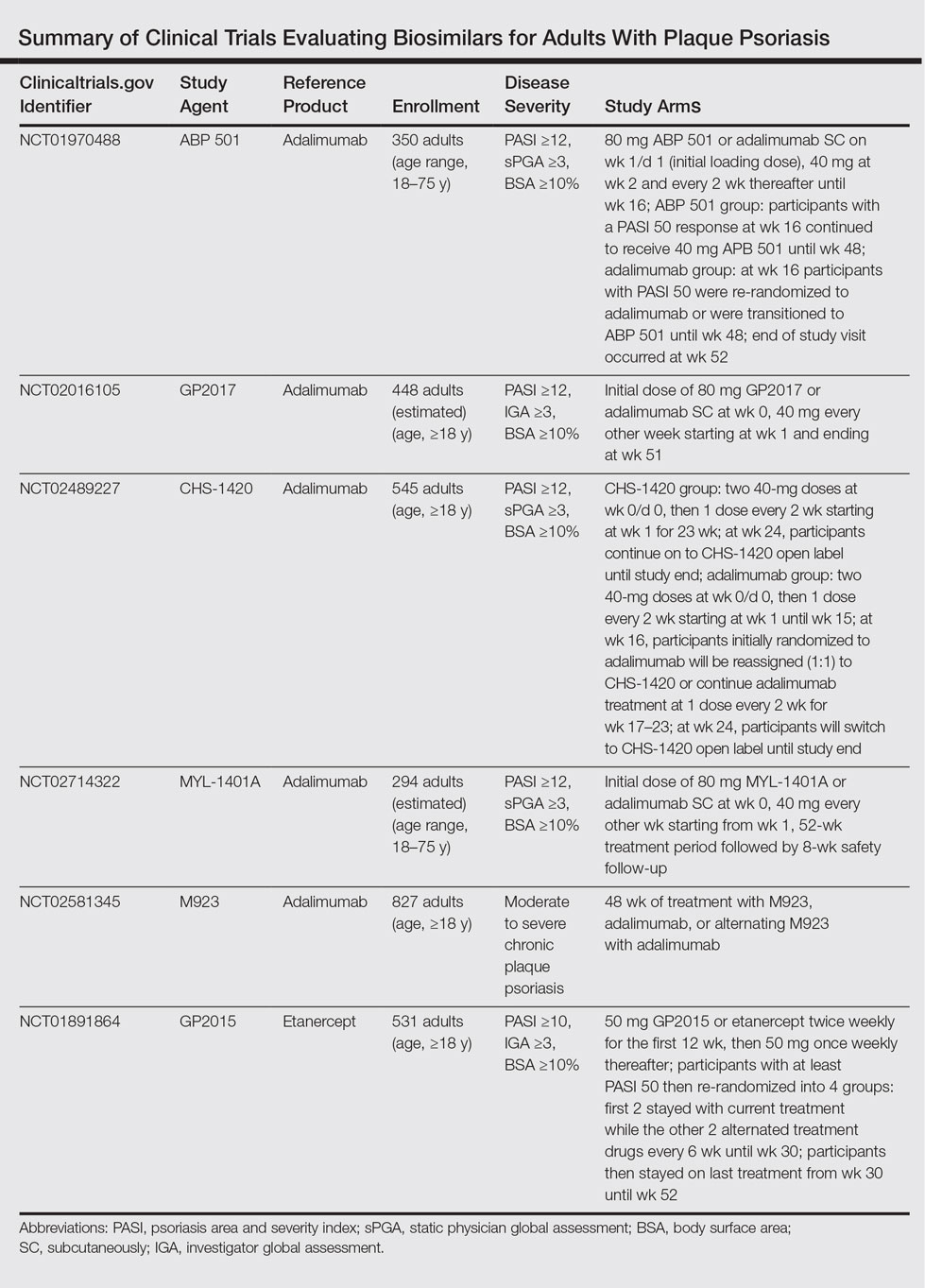

The Table summarizes clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) evaluating biosimilars in adults with plaque psoriasis; thus far, there are 2464 participants enrolled across 5 different studies of adalimumab biosimilars (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01970488, NCT02016105, NCT02489227, NCT02714322, NCT02581345) and 531 participants in an etanercept biosimilar study (NCT01891864).

A phase 3 double-blind study compared adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar (ABP 501) in 350 adults with plaque psoriasis (NCT01970488). Participants received an initial loading dose of adalimumab (n=175) or ABP 501 (n=175) 80 mg subcutaneously on week 1/day 1, followed by 40 mg at week 2 every 2 weeks thereafter. At week 16, participants with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 50 or greater remained in the study for up to 52 weeks; those who were receiving adalimumab were re-randomized to receive either ABP 501 or adalimumab. Participants receiving ABP 501 continued to receive the biosimilar. The mean PASI improvement at weeks 16, 32, and 50 was 86.6, 87.6, and 87.2, respectively, in the ABP 501/ABP 501 group (A/A) compared to 88.0, 88.2, and 88.1, respectively, in the adalimumab/adalimumab group (B/B).19 Autoantibodies developed in 68.4% of participants in the A/A group compared to 74.7% in the B/B group. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 86.2% in the A/A group and 78.5% in the B/B group. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of serious TEAEs was 4.6% in the A/A group compared to 5.1% in the B/B group. Overall, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar was comparable to the reference product.19

A second phase 3 trial (ADACCESS) evaluated the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 (NCT02016105). Participants received an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either GP2017 or adalimumab at week 0, followed by 40 mg every other week starting at week 1 and ending at week 51. The study has been completed but results are not yet available.

The third trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar CHS-1420 (NCT02489227). Participants in the experimental arm receive two 40-mg doses of CHS-1420 at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 for 23 weeks. At week 24, participants continue with an open-label study. Participants in the adalimumab group receive two 40-mg doses at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 to week 15. At week 16, participants will be re-randomized (1:1) to continue adalimumab or start CHS-1420 at one 40-mg dose every 2 weeks during weeks 17 to 23. At week 24, participants will switch to CHS-1420 open label until the end of the study. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

The fourth ongoing trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar MYL-1401A (NCT02714322). Participants receive an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either MYL-1401A or adalimumab (2:1), followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the initial dose. After the 52-week treatment period, there is an 8-week safety follow-up period. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

A fifth adalimumab biosimilar, M923, also is currently being tested in clinical trials (NCT02581345). Participants receive either M923, adalimumab, or alternate between the 2 agents. Although the study is still ongoing, data released from the manufacturer state that the proportion of participants who achieved PASI 75 after 16 weeks of treatment was equivalent in the 2 treatment groups. The proportion of participants who achieved PASI 90, as well as the type, frequency, and severity of adverse events, also were comparable.20

The EGALITY trial, completed in March 2015, compared the etanercept biosimilar GP2015 to etanercept over a 52-week period (NCT01891864). Participants received either GP2015 or etanercept 50 mg twice weekly for the first 12 weeks. Participants with at least PASI 50 were then re-randomized into 4 groups: the first 2 groups stayed with their current treatments while the other 2 groups alternated treatments every 6 weeks until week 30. Participants then stayed on their last treatment from week 30 to week 52. The adjusted PASI 75 response rate at week 12 was 73.4% in the group receiving GP2015 and 75.7% in the group receiving etanercept.21 The percentage change in PASI score at all time points was found to be comparable from baseline until week 52. Importantly, the incidence of TEAEs up to week 52 was comparable and no new safety issues were reported. Additionally, switching participants from etanercept to the biosimilar during the subsequent treatment periods did not cause an increase in formation of antidrug antibodies.21

There are 2 upcoming studies involving biosimilars that are not yet recruiting patients. The first (NCT02925338) will analyze the characteristics of patients treated with Inflectra as well as their response to treatment. The second (NCT02762955) will be comparing the efficacy and safety of an adalimumab biosimilar (BCD-057, BIOCAD) to adalimumab.

Economic Advantages of Biosimilars

The annual economic burden of psoriasis in the United States is substantial, with estimates between $35.2 billion22 and $112 billion.23 Biosimilars can be 25% to 30% cheaper than their reference products9,11,24 and have the potential to save the US health care system billions of dollars.25 Furthermore, the developers of biosimilars could offer patient assistance programs.11 That being said, drug developers can extend patents for their branded drugs; for instance, 2 patents for Enbrel (Amgen Inc) could protect the drug until 2029.26,27

Although cost is an important factor in deciding which medications to prescribe for patients, it should never take precedence over safety and efficacy. Manufacturers can develop new drugs with greater efficacy, fewer side effects, or more convenient dosing schedules,26,27 or they could offer co-payment assistance programs.26,28 Physicians also must consider how the biosimilars will be integrated into drug formularies. Would patients be required to use a biosimilar before a branded drug?11,29 Will patients already taking a branded drug be grandfathered in?11 Would they have to pay a premium to continue taking their drug? And finally, could changes in formularies and employer-payer relationships destabilize patient regimens?30

Conclusion

Preliminary results suggest that biosimilars can have similar safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity data compared to their reference products.19,21 Biosimilars have the potential to greatly reduce the cost burden associated with psoriasis. However, how similar is “highly similar”? Although cost is an important consideration in selecting drug therapies, the reason for using a biosimilar should never be based on cost alone.

- Information on biosimilars. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/. Updated May 10, 2016. Accessed July 5, 2016.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product: Guidance for Industry. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2015.

- McKeage K. A review of CT-P13: an infliximab biosimilar. BioDrugs. 2014;28:313-321.

- FDA approves Inflectra, a biosimilar to Remicade [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 5, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494227.htm. Updated April 20, 2016. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- FDA approves Erelzi, a biosimilar to Enbrel [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; August 30, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518639.htm. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- FDA approves Amjevita, a biosimilar to Humira [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; September 23, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm522243.htm. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- Scott BJ, Klein AV, Wang J. Biosimilar monoclonal antibodies: a Canadian regulatory perspective on the assessment of clinically relevant differences and indication extrapolation [published online June 26, 2014]. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(suppl 3):S123-S132.

- Mellstedt H, Niederwieser D, Ludwig H. The challenge of biosimilars [published online September 14, 2007]. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:411-419.

- Puig L. Biosimilars and reference biologics: decisions on biosimilar interchangeability require the involvement of dermatologists [published online October 2, 2013]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:435-437.

- Strober BE, Armour K, Romiti R, et al. Biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars in psoriasis: what the dermatologist needs to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:317-322.

- Falit BP, Singh SC, Brennan TA. Biosimilar competition in the United States: statutory incentives, payers, and pharmacy benefit managers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:294-301.

- Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605-1612.

- Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613-1620.

- Carretero Hernandez G, Puig L. The use of biosimilar drugs in psoriasis: a position paper. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:249-251.

- Regulation of Biological Products, 42 USC §262 (2013).

- Ventola CL. Evaluation of biosimilars for formulary inclusion: factors for consideration by P&T committees. P T. 2015;40:680-689.

- Park W, Yoo DH, Jaworski J, et al. Comparable long-term efficacy, as assessed by patient-reported outcomes, safety and pharmacokinetics, of CT-P13 and reference infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 54-week results from the randomized, parallel-group PLANETAS study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:25.

- Yoo DH, Racewicz A, Brzezicki J, et al. A phase III randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with reference infliximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: 54-week results from the PLANETRA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;18:82.

- Strober B, Foley P, Philipp S, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of ABP 501 in a phase 3 study in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5, suppl 1):AB249.

- Momenta Pharmaceuticals announces positive top-line phase 3 results for M923, a proposed Humira (adalimumab) biosimilar [news release]. Cambridge, MA: Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Inc; November 29, 2016. http://ir.momentapharma.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=1001255. Accessed January 25, 2017.

- Griffiths CE, Thaci D, Gerdes S, et al. The EGALITY study: a confirmatory, randomised, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of GP2015, a proposed etanercept biosimilar, versus the originator product in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis [published online October 27, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15152.

- Vanderpuye-Orgle J, Zhao Y, Lu J, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States [published online April 14, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:961-967.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

- Menter MA, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: the future. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:161-166.

- Hackbarth GM, Crosson FJ, Miller ME. Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Washington, DC; 2009.

- Lovenworth SJ. The new biosimilar era: the basics, the landscape, and the future. Bloomberg website. http://about.bloomberglaw.com/practitioner-contributions/the-new-biosimilar-era-the-basics-the-landscape-and-the-future. Published September 21, 2012. Accessed July 6, 2016.

- Blackstone EA, Joseph PF. The economics of biosimilars. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:469-478.

- Calvo B, Zuniga L. The US approach to biosimilars: the long-awaited FDA approval pathway. BioDrugs. 2012;26:357-361.

- Lucio SD, Stevenson JG, Hoffman JM. Biosimilars: implications for health-system pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:2004-2017.

- Barriers to access attributed to formulary changes. Manag Care. 2012;21:41.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is “highly similar to an FDA-approved biological product, . . . and has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”1 The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act of 2009 created an expedited pathway for the approval of products shown to be biosimilar to FDA-licensed reference products.2 In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the first biosimilar modeled on infliximab (Remsima [formerly known as CT-P13], Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd) for the same indications as its reference product.3 In 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra (Hospira, a Pfizer Company), an infliximab biosimilar; Erelzi (Sandoz, a Novartis Division), an etanercept biosimilar; and Amjevita (Amgen Inc), an adalimumab biosimilar, all for numerous clinical indications including plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.4-6

There has been a substantial amount of distrust surrounding the biosimilars; however, as the patents for the biologic agents expire, new biosimilars will undoubtedly flood the market. In this article, we provide information that will help dermatologists understand the need for and use of these agents.

Biosimilars Versus Generic Drugs

Small-molecule generics can be made in a process that is relatively inexpensive, reproducible, and able to yield identical products with each lot.7 In contrast, biosimilars are large complex proteins made in living cells. They differ from their reference product because of changes that occur during manufacturing (eg, purification system, posttranslational modifications).7-9 Glycosylation is particularly sensitive to manufacturing and can affect the immunogenicity of the product.9 The impact of manufacturing can be substantial; for example, during phase 3 trials for efalizumab, a change in the manufacturing facility affected pharmacokinetic properties to such a degree that the FDA required a repeat of the trials.10

FDA Guidelines on Biosimilarity

The FDA outlines the following approach to demonstrate biosimilarity.2 The first step is structural characterization to evaluate the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures and posttranslational modifications. The next step utilizes in vivo and/or in vitro functional assays to compare the biosimilar and reference product. The third step is a focus on toxicity and immunogenicity. The fourth step involves clinical studies to study pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy. After the biosimilar has been approved, there must be a system in place to monitor postmarketing safety. If a biosimilar is tested in one patient population (eg, patients with plaque psoriasis), a request can be made to approve the drug for all the conditions that the reference product was approved for, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, even though clinical trials were not performed in all of these patient populations.2 The BPCI Act leaves it up to the FDA to determine how much and what type of data (eg, in vitro, in vivo, clinical) are required.11

Extrapolation and Interchangeability

Once a biosimilar has been approved, 2 questions must be answered: First, can its use be extrapolated to all indications for the reference product? The infliximab biosimilar approved by the European Medicines Agency and the FDA had only been studied in patients with ankylosing spondylitis12 and rheumatoid arthritis,13 yet it was granted all the indications for infliximab, including severe plaque psoriasis.14 As of now, the various regulatory agencies differ on their policies regarding extrapolation. Extrapolation is not automatically bestowed on a biosimilar in the United States but can be requested by the manufacturer.2

Second, can the biosimilar be seamlessly switched with its reference product at the pharmacy level? The BPCI Act allows for the substitution of biosimilars that are deemed interchangeable without notifying the provider, yet individual states ultimately can pass laws regarding this issue.15,16 An interchangeable agent would “produce the same clinical result as the reference product,” and “the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product.”15 Generic drugs are allowed to be substituted without notifying the patient or prescriber16; however, biosimilars that are not deemed interchangeable would require permission from the prescriber before substitution.11

Biosimilars for Psoriasis

In April 2016, an infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra) became the second biosimilar approved by the FDA.4 Inflectra was studied in clinical trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis17 and rheumatoid arthritis,18 and in both trials the biosimilar was found to have similar efficacy and safety profiles to that of the reference product. In August 2016, an etanercept biosimilar (Erelzi) was approved,5 and in September 2016, an adalimumab biosimilar (Amjevita) was approved.6

The Table summarizes clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) evaluating biosimilars in adults with plaque psoriasis; thus far, there are 2464 participants enrolled across 5 different studies of adalimumab biosimilars (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01970488, NCT02016105, NCT02489227, NCT02714322, NCT02581345) and 531 participants in an etanercept biosimilar study (NCT01891864).

A phase 3 double-blind study compared adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar (ABP 501) in 350 adults with plaque psoriasis (NCT01970488). Participants received an initial loading dose of adalimumab (n=175) or ABP 501 (n=175) 80 mg subcutaneously on week 1/day 1, followed by 40 mg at week 2 every 2 weeks thereafter. At week 16, participants with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 50 or greater remained in the study for up to 52 weeks; those who were receiving adalimumab were re-randomized to receive either ABP 501 or adalimumab. Participants receiving ABP 501 continued to receive the biosimilar. The mean PASI improvement at weeks 16, 32, and 50 was 86.6, 87.6, and 87.2, respectively, in the ABP 501/ABP 501 group (A/A) compared to 88.0, 88.2, and 88.1, respectively, in the adalimumab/adalimumab group (B/B).19 Autoantibodies developed in 68.4% of participants in the A/A group compared to 74.7% in the B/B group. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 86.2% in the A/A group and 78.5% in the B/B group. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of serious TEAEs was 4.6% in the A/A group compared to 5.1% in the B/B group. Overall, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar was comparable to the reference product.19

A second phase 3 trial (ADACCESS) evaluated the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 (NCT02016105). Participants received an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either GP2017 or adalimumab at week 0, followed by 40 mg every other week starting at week 1 and ending at week 51. The study has been completed but results are not yet available.

The third trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar CHS-1420 (NCT02489227). Participants in the experimental arm receive two 40-mg doses of CHS-1420 at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 for 23 weeks. At week 24, participants continue with an open-label study. Participants in the adalimumab group receive two 40-mg doses at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 to week 15. At week 16, participants will be re-randomized (1:1) to continue adalimumab or start CHS-1420 at one 40-mg dose every 2 weeks during weeks 17 to 23. At week 24, participants will switch to CHS-1420 open label until the end of the study. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

The fourth ongoing trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar MYL-1401A (NCT02714322). Participants receive an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either MYL-1401A or adalimumab (2:1), followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the initial dose. After the 52-week treatment period, there is an 8-week safety follow-up period. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

A fifth adalimumab biosimilar, M923, also is currently being tested in clinical trials (NCT02581345). Participants receive either M923, adalimumab, or alternate between the 2 agents. Although the study is still ongoing, data released from the manufacturer state that the proportion of participants who achieved PASI 75 after 16 weeks of treatment was equivalent in the 2 treatment groups. The proportion of participants who achieved PASI 90, as well as the type, frequency, and severity of adverse events, also were comparable.20

The EGALITY trial, completed in March 2015, compared the etanercept biosimilar GP2015 to etanercept over a 52-week period (NCT01891864). Participants received either GP2015 or etanercept 50 mg twice weekly for the first 12 weeks. Participants with at least PASI 50 were then re-randomized into 4 groups: the first 2 groups stayed with their current treatments while the other 2 groups alternated treatments every 6 weeks until week 30. Participants then stayed on their last treatment from week 30 to week 52. The adjusted PASI 75 response rate at week 12 was 73.4% in the group receiving GP2015 and 75.7% in the group receiving etanercept.21 The percentage change in PASI score at all time points was found to be comparable from baseline until week 52. Importantly, the incidence of TEAEs up to week 52 was comparable and no new safety issues were reported. Additionally, switching participants from etanercept to the biosimilar during the subsequent treatment periods did not cause an increase in formation of antidrug antibodies.21

There are 2 upcoming studies involving biosimilars that are not yet recruiting patients. The first (NCT02925338) will analyze the characteristics of patients treated with Inflectra as well as their response to treatment. The second (NCT02762955) will be comparing the efficacy and safety of an adalimumab biosimilar (BCD-057, BIOCAD) to adalimumab.

Economic Advantages of Biosimilars

The annual economic burden of psoriasis in the United States is substantial, with estimates between $35.2 billion22 and $112 billion.23 Biosimilars can be 25% to 30% cheaper than their reference products9,11,24 and have the potential to save the US health care system billions of dollars.25 Furthermore, the developers of biosimilars could offer patient assistance programs.11 That being said, drug developers can extend patents for their branded drugs; for instance, 2 patents for Enbrel (Amgen Inc) could protect the drug until 2029.26,27

Although cost is an important factor in deciding which medications to prescribe for patients, it should never take precedence over safety and efficacy. Manufacturers can develop new drugs with greater efficacy, fewer side effects, or more convenient dosing schedules,26,27 or they could offer co-payment assistance programs.26,28 Physicians also must consider how the biosimilars will be integrated into drug formularies. Would patients be required to use a biosimilar before a branded drug?11,29 Will patients already taking a branded drug be grandfathered in?11 Would they have to pay a premium to continue taking their drug? And finally, could changes in formularies and employer-payer relationships destabilize patient regimens?30

Conclusion

Preliminary results suggest that biosimilars can have similar safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity data compared to their reference products.19,21 Biosimilars have the potential to greatly reduce the cost burden associated with psoriasis. However, how similar is “highly similar”? Although cost is an important consideration in selecting drug therapies, the reason for using a biosimilar should never be based on cost alone.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is “highly similar to an FDA-approved biological product, . . . and has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”1 The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act of 2009 created an expedited pathway for the approval of products shown to be biosimilar to FDA-licensed reference products.2 In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the first biosimilar modeled on infliximab (Remsima [formerly known as CT-P13], Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd) for the same indications as its reference product.3 In 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra (Hospira, a Pfizer Company), an infliximab biosimilar; Erelzi (Sandoz, a Novartis Division), an etanercept biosimilar; and Amjevita (Amgen Inc), an adalimumab biosimilar, all for numerous clinical indications including plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.4-6

There has been a substantial amount of distrust surrounding the biosimilars; however, as the patents for the biologic agents expire, new biosimilars will undoubtedly flood the market. In this article, we provide information that will help dermatologists understand the need for and use of these agents.

Biosimilars Versus Generic Drugs

Small-molecule generics can be made in a process that is relatively inexpensive, reproducible, and able to yield identical products with each lot.7 In contrast, biosimilars are large complex proteins made in living cells. They differ from their reference product because of changes that occur during manufacturing (eg, purification system, posttranslational modifications).7-9 Glycosylation is particularly sensitive to manufacturing and can affect the immunogenicity of the product.9 The impact of manufacturing can be substantial; for example, during phase 3 trials for efalizumab, a change in the manufacturing facility affected pharmacokinetic properties to such a degree that the FDA required a repeat of the trials.10

FDA Guidelines on Biosimilarity

The FDA outlines the following approach to demonstrate biosimilarity.2 The first step is structural characterization to evaluate the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures and posttranslational modifications. The next step utilizes in vivo and/or in vitro functional assays to compare the biosimilar and reference product. The third step is a focus on toxicity and immunogenicity. The fourth step involves clinical studies to study pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy. After the biosimilar has been approved, there must be a system in place to monitor postmarketing safety. If a biosimilar is tested in one patient population (eg, patients with plaque psoriasis), a request can be made to approve the drug for all the conditions that the reference product was approved for, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, even though clinical trials were not performed in all of these patient populations.2 The BPCI Act leaves it up to the FDA to determine how much and what type of data (eg, in vitro, in vivo, clinical) are required.11

Extrapolation and Interchangeability

Once a biosimilar has been approved, 2 questions must be answered: First, can its use be extrapolated to all indications for the reference product? The infliximab biosimilar approved by the European Medicines Agency and the FDA had only been studied in patients with ankylosing spondylitis12 and rheumatoid arthritis,13 yet it was granted all the indications for infliximab, including severe plaque psoriasis.14 As of now, the various regulatory agencies differ on their policies regarding extrapolation. Extrapolation is not automatically bestowed on a biosimilar in the United States but can be requested by the manufacturer.2

Second, can the biosimilar be seamlessly switched with its reference product at the pharmacy level? The BPCI Act allows for the substitution of biosimilars that are deemed interchangeable without notifying the provider, yet individual states ultimately can pass laws regarding this issue.15,16 An interchangeable agent would “produce the same clinical result as the reference product,” and “the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product.”15 Generic drugs are allowed to be substituted without notifying the patient or prescriber16; however, biosimilars that are not deemed interchangeable would require permission from the prescriber before substitution.11

Biosimilars for Psoriasis

In April 2016, an infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra) became the second biosimilar approved by the FDA.4 Inflectra was studied in clinical trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis17 and rheumatoid arthritis,18 and in both trials the biosimilar was found to have similar efficacy and safety profiles to that of the reference product. In August 2016, an etanercept biosimilar (Erelzi) was approved,5 and in September 2016, an adalimumab biosimilar (Amjevita) was approved.6

The Table summarizes clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) evaluating biosimilars in adults with plaque psoriasis; thus far, there are 2464 participants enrolled across 5 different studies of adalimumab biosimilars (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01970488, NCT02016105, NCT02489227, NCT02714322, NCT02581345) and 531 participants in an etanercept biosimilar study (NCT01891864).

A phase 3 double-blind study compared adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar (ABP 501) in 350 adults with plaque psoriasis (NCT01970488). Participants received an initial loading dose of adalimumab (n=175) or ABP 501 (n=175) 80 mg subcutaneously on week 1/day 1, followed by 40 mg at week 2 every 2 weeks thereafter. At week 16, participants with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 50 or greater remained in the study for up to 52 weeks; those who were receiving adalimumab were re-randomized to receive either ABP 501 or adalimumab. Participants receiving ABP 501 continued to receive the biosimilar. The mean PASI improvement at weeks 16, 32, and 50 was 86.6, 87.6, and 87.2, respectively, in the ABP 501/ABP 501 group (A/A) compared to 88.0, 88.2, and 88.1, respectively, in the adalimumab/adalimumab group (B/B).19 Autoantibodies developed in 68.4% of participants in the A/A group compared to 74.7% in the B/B group. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 86.2% in the A/A group and 78.5% in the B/B group. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of serious TEAEs was 4.6% in the A/A group compared to 5.1% in the B/B group. Overall, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar was comparable to the reference product.19

A second phase 3 trial (ADACCESS) evaluated the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 (NCT02016105). Participants received an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either GP2017 or adalimumab at week 0, followed by 40 mg every other week starting at week 1 and ending at week 51. The study has been completed but results are not yet available.

The third trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar CHS-1420 (NCT02489227). Participants in the experimental arm receive two 40-mg doses of CHS-1420 at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 for 23 weeks. At week 24, participants continue with an open-label study. Participants in the adalimumab group receive two 40-mg doses at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 to week 15. At week 16, participants will be re-randomized (1:1) to continue adalimumab or start CHS-1420 at one 40-mg dose every 2 weeks during weeks 17 to 23. At week 24, participants will switch to CHS-1420 open label until the end of the study. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

The fourth ongoing trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar MYL-1401A (NCT02714322). Participants receive an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either MYL-1401A or adalimumab (2:1), followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the initial dose. After the 52-week treatment period, there is an 8-week safety follow-up period. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

A fifth adalimumab biosimilar, M923, also is currently being tested in clinical trials (NCT02581345). Participants receive either M923, adalimumab, or alternate between the 2 agents. Although the study is still ongoing, data released from the manufacturer state that the proportion of participants who achieved PASI 75 after 16 weeks of treatment was equivalent in the 2 treatment groups. The proportion of participants who achieved PASI 90, as well as the type, frequency, and severity of adverse events, also were comparable.20

The EGALITY trial, completed in March 2015, compared the etanercept biosimilar GP2015 to etanercept over a 52-week period (NCT01891864). Participants received either GP2015 or etanercept 50 mg twice weekly for the first 12 weeks. Participants with at least PASI 50 were then re-randomized into 4 groups: the first 2 groups stayed with their current treatments while the other 2 groups alternated treatments every 6 weeks until week 30. Participants then stayed on their last treatment from week 30 to week 52. The adjusted PASI 75 response rate at week 12 was 73.4% in the group receiving GP2015 and 75.7% in the group receiving etanercept.21 The percentage change in PASI score at all time points was found to be comparable from baseline until week 52. Importantly, the incidence of TEAEs up to week 52 was comparable and no new safety issues were reported. Additionally, switching participants from etanercept to the biosimilar during the subsequent treatment periods did not cause an increase in formation of antidrug antibodies.21