User login

Hormonal Contraceptives: Risk or Benefit in Migraine?

SAN DIEGO—Among women with migraine, low-dose combined estrogen–progestin contraceptives do not increase the risk of stroke, and continuous hormonal contraceptive use may reduce menstrual migraine, according to a lecture delivered at the 58th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society.

High doses of combined oral contraceptives do increase stroke risk, and migraine with aura confers an independent increased risk of stroke, said Anne H. Calhoun, MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and partner and cofounder of the Carolina Headache Institute in Durham. Evidence does not suggest, however, that low-dose hormonal contraceptive use together with history of migraine confers additive risk, she said.

Over the last several decades, various combined oral contraceptive regimens (eg, triphasic, extended cycle, and continuous) with a range of estrogen doses have been developed. “They are all over the place, and we really need to know what we are dealing with,” Dr. Calhoun said. Risks of combined oral contraceptives, including myocardial infarction and stroke, are almost exclusively seen with smoking and high-dose pills, she said.

Dr. Calhoun prefers to prescribe pills that inhibit ovulation while using 20 μg or less of the synthetic estrogen ethinyl estradiol (EE) for women at increased risk of stroke. The highest dose pill in the United States contains 50 μg of estrogen. The lowest dose pill contains 10 μg.

Placebo Side Effects

In hormonal contraception, headache often develops during the placebo week. A typical contraceptive regimen includes 21 active pills and seven placebo pills. Sulak et al found that 70% of women taking birth control pills had headache during the placebo week, and peak incidence of headache was on the third day of the placebo week. “When you eliminated the placebo week, it improved mood scores, improved headache scores, there was less dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain,” Dr. Calhoun said.

When estrogen concentrations decrease upon taking placebo, 5HT concentration in the CNS declines, serotonin synthesis declines, monoamine oxidase and calcitonin gene-related peptide concentrations increase, and beta endorphins decline. “All pain is perceived as more intense,” she said. Furthermore, flow-mediated vasodilation parallels estrogen levels.

“You would think looking at all this, in a field where most of the patients are women, and the majority of them have menstrual migraine, and all of these things happen when estrogen falls, that headache specialists would be really interested in preventing estrogen from declining every month,” Dr. Calhoun said.

Reducing Migraine

In 2012, Dr. Calhoun and colleagues published a retrospective database review that identified 23 women in a subspecialty menstrual migraine clinic who had migraine with aura, a confirmed diagnosis of menstrual-related migraine, and who received treatment with extended-cycle dosing of a transvaginal ring contraceptive containing 0.120 mg of etonogestrel and 15 μg of EE for at least a month. The women were treated with the transvaginal ring for the purpose of migraine prevention, and not to prevent pregnancy. Participants were observed for an average of eight months. Women used the ultralow-dose ring contraceptive continuously. Instead of using the ring for three weeks followed by one week without the ring, women replaced the ring every three weeks. “With that, you stop ovulation with a level of estrogen that is lower than your own natural menstrual cycle. You do not have the high ovulatory peaks or even the peaks of the luteal phase,” she said.

At baseline, subjects experienced a median of 3.2 auras per month. With treatment, the median number of auras per month decreased to 0.2. Frequency of aura decreased from baseline for each participant, and menstrual migraine was eliminated in 91.3% of patients. Such use of hormonal contraceptives for the prevention of migraine is off label, Dr. Calhoun noted.

Risk of Stroke

How oral contraceptives affect risk of stroke has been studied for decades. In a 1975 study in JAMA, researchers looked at 140 cases of stroke in young women and compared them with hospital controls. There was a 4.6 times increased risk of stroke if a woman was taking high-dose oral contraceptives.

Hannaford et al in 1994 published a nested case–control analysis using data mainly from the 1970s and 1980s. They found that high-dose oral contraceptive use was associated with a sixfold increased risk of first stroke. Low-dose pills—including 30-μg and 35-μg pills, “which I do not think of as particularly low dose these days”—did not significantly increase risk, Dr. Calhoun said. However, the risk with these moderate-dose pills is usually around 1.2 to 2.5 times greater and is significant in some studies, she noted. Today’s “low-dose” pills (≤ 20 μg EE) are the best for decreasing risk.

In 1996, a study by Petitti et al looked at risk of stroke with “low-dose” (at that time meaning simply < 50 μg EE) hormonal contraceptives in the US. They identified 408 strokes in 3.6 million women-years and concluded that stroke is rare in this population. Low-dose pills did not increase the risk. At that time, 99.4% of prescriptions for hormonal contraception in the US contained less than 50 μg of estrogen.

ACOG Guideline

In 2006, however, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommended against using combination hormonal contraceptives in patients with migraine with aura. This guideline and some of the studies on which the recommendation was based are problematic, Dr. Calhoun said.

The recommendation stemmed in part from a concern that all women with migraine are at increased risk of stroke if they take combined hormonal contraceptives. That concern was based on a 1996 World Health Organization study that had no US sites. In the study, the majority of stroke cases were smokers and the average age was over 35. In the US, 35 tends to be the age at which physicians—in accordance with ACOG recommendations—no longer prescribe combined hormonal contraceptives for smokers, Dr. Calhoun said. In addition, the majority of the stroke cases were using high-dose pills. The authors concluded that migraine of greater than 12 years’ duration, migraine with aura, and frequent migraine with aura increased the risk of stroke. “But the authors concluded themselves, in no case did corrections for oral contraceptive use alter these observations. It was not a factor,” Dr. Calhoun said.

The ACOG guideline also was based on a Danish population-based case–control study by Lidegaard et al that found a threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. In this study, however, they reported that only 6% of the control group had migraine, whereas 16% to 18% of women in Denmark have migraine—a rate similar to what was seen in the cases. That produced the threefold increased risk reported in the study, Dr. Calhoun said. A similar study in France did not find increased risk among migraineurs using oral contraceptives, but in that study, both controls and migraineurs had the normal frequency of migraine in the population.

Finally, the ACOG recommendation was based on a pooled analysis of two large US case–control studies that found a twofold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. This finding by Schwartz et al was based on only four cases. The prevalence of migraine was virtually identical among ischemic stroke cases and controls who were using oral contraceptives (7.8% and 7.7%, respectively), but became significant after adjustment for other factors. But a key factor that was not taken into account was use of high-dose (≥ 50 μg EE) pills, Dr. Calhoun said. They were used by only 11 of the 1,564 ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke cases and controls, but accounted for four of the strokes.

Low Doses Appear Safe

Recent studies have had similar findings. A 15-year prospective population-based study by Lidegaard et al in 2012 analyzed 3,300 thrombotic strokes and 1,700 myocardial infarctions in more than 1.6 million women. The overall risk was low, and the absolute risk of thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction was not increased with 20-μg pills. Pills with doses of 30 μg to 40 μg, however, as much as doubled the risk. “It is still better than the 4.5-times increased risk we had with the 50-μg pills, but we do not want to go there,” Dr. Calhoun said.

A 2013 study by Sidney et al compared a 20-μg oral birth control pill with a 30-μg oral birth control pill, a 20-μg patch birth control product, and a 15-μg ring birth control product. As expected, the 30-μg pill increased risk of thrombotic events, relative to the 20-μg pill, whereas the other products did not, Dr. Calhoun said.

“The argument against using combined hormonal contraceptives in migraine with aura is based on concerns that all women are at increased risk of stroke with oral contraceptives. That is false,” she said. “It is high-dose oral contraceptives that increase the risk.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1453-1472.

Calhoun A, Ford S, Pruitt A. The impact of extended-cycle vaginal ring contraception on migraine aura: a retrospective case series. Headache. 2012;52(8):1246-1253.

Hannaford PC, Croft PR, Kay CR. Oral contraception and stroke. Evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception study. Stroke. 1994;25(5):935-942.

Ischaemic stroke and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1996;348(9026):498-505.

Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65(3):197-205.

Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2257-2266.

MacGregor EA. Contraception and headache. Headache. 2013;53(2):247-276.

Oral contraceptives and stroke in young women. Associated risk factors. JAMA. 1975;231(7):718-722.

Petitti DB, Sidney S, Bernstein A, et al. Stroke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8-15.

Schwartz SM, Petitti DB, Siscovick DS, et al. Stroke and use of low-dose oral contraceptives in young women: a pooled analysis of two US studies. Stroke. 1998;29(11):2277-2284.

Sidney S, Cheetham TC, Connell FA, et al. Recent combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of thromboembolism and other cardiovascular events in new users. Contraception. 2013;87(1):93-100.

Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47(1):27-37.

Sulak PJ, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):261-266.

SAN DIEGO—Among women with migraine, low-dose combined estrogen–progestin contraceptives do not increase the risk of stroke, and continuous hormonal contraceptive use may reduce menstrual migraine, according to a lecture delivered at the 58th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society.

High doses of combined oral contraceptives do increase stroke risk, and migraine with aura confers an independent increased risk of stroke, said Anne H. Calhoun, MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and partner and cofounder of the Carolina Headache Institute in Durham. Evidence does not suggest, however, that low-dose hormonal contraceptive use together with history of migraine confers additive risk, she said.

Over the last several decades, various combined oral contraceptive regimens (eg, triphasic, extended cycle, and continuous) with a range of estrogen doses have been developed. “They are all over the place, and we really need to know what we are dealing with,” Dr. Calhoun said. Risks of combined oral contraceptives, including myocardial infarction and stroke, are almost exclusively seen with smoking and high-dose pills, she said.

Dr. Calhoun prefers to prescribe pills that inhibit ovulation while using 20 μg or less of the synthetic estrogen ethinyl estradiol (EE) for women at increased risk of stroke. The highest dose pill in the United States contains 50 μg of estrogen. The lowest dose pill contains 10 μg.

Placebo Side Effects

In hormonal contraception, headache often develops during the placebo week. A typical contraceptive regimen includes 21 active pills and seven placebo pills. Sulak et al found that 70% of women taking birth control pills had headache during the placebo week, and peak incidence of headache was on the third day of the placebo week. “When you eliminated the placebo week, it improved mood scores, improved headache scores, there was less dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain,” Dr. Calhoun said.

When estrogen concentrations decrease upon taking placebo, 5HT concentration in the CNS declines, serotonin synthesis declines, monoamine oxidase and calcitonin gene-related peptide concentrations increase, and beta endorphins decline. “All pain is perceived as more intense,” she said. Furthermore, flow-mediated vasodilation parallels estrogen levels.

“You would think looking at all this, in a field where most of the patients are women, and the majority of them have menstrual migraine, and all of these things happen when estrogen falls, that headache specialists would be really interested in preventing estrogen from declining every month,” Dr. Calhoun said.

Reducing Migraine

In 2012, Dr. Calhoun and colleagues published a retrospective database review that identified 23 women in a subspecialty menstrual migraine clinic who had migraine with aura, a confirmed diagnosis of menstrual-related migraine, and who received treatment with extended-cycle dosing of a transvaginal ring contraceptive containing 0.120 mg of etonogestrel and 15 μg of EE for at least a month. The women were treated with the transvaginal ring for the purpose of migraine prevention, and not to prevent pregnancy. Participants were observed for an average of eight months. Women used the ultralow-dose ring contraceptive continuously. Instead of using the ring for three weeks followed by one week without the ring, women replaced the ring every three weeks. “With that, you stop ovulation with a level of estrogen that is lower than your own natural menstrual cycle. You do not have the high ovulatory peaks or even the peaks of the luteal phase,” she said.

At baseline, subjects experienced a median of 3.2 auras per month. With treatment, the median number of auras per month decreased to 0.2. Frequency of aura decreased from baseline for each participant, and menstrual migraine was eliminated in 91.3% of patients. Such use of hormonal contraceptives for the prevention of migraine is off label, Dr. Calhoun noted.

Risk of Stroke

How oral contraceptives affect risk of stroke has been studied for decades. In a 1975 study in JAMA, researchers looked at 140 cases of stroke in young women and compared them with hospital controls. There was a 4.6 times increased risk of stroke if a woman was taking high-dose oral contraceptives.

Hannaford et al in 1994 published a nested case–control analysis using data mainly from the 1970s and 1980s. They found that high-dose oral contraceptive use was associated with a sixfold increased risk of first stroke. Low-dose pills—including 30-μg and 35-μg pills, “which I do not think of as particularly low dose these days”—did not significantly increase risk, Dr. Calhoun said. However, the risk with these moderate-dose pills is usually around 1.2 to 2.5 times greater and is significant in some studies, she noted. Today’s “low-dose” pills (≤ 20 μg EE) are the best for decreasing risk.

In 1996, a study by Petitti et al looked at risk of stroke with “low-dose” (at that time meaning simply < 50 μg EE) hormonal contraceptives in the US. They identified 408 strokes in 3.6 million women-years and concluded that stroke is rare in this population. Low-dose pills did not increase the risk. At that time, 99.4% of prescriptions for hormonal contraception in the US contained less than 50 μg of estrogen.

ACOG Guideline

In 2006, however, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommended against using combination hormonal contraceptives in patients with migraine with aura. This guideline and some of the studies on which the recommendation was based are problematic, Dr. Calhoun said.

The recommendation stemmed in part from a concern that all women with migraine are at increased risk of stroke if they take combined hormonal contraceptives. That concern was based on a 1996 World Health Organization study that had no US sites. In the study, the majority of stroke cases were smokers and the average age was over 35. In the US, 35 tends to be the age at which physicians—in accordance with ACOG recommendations—no longer prescribe combined hormonal contraceptives for smokers, Dr. Calhoun said. In addition, the majority of the stroke cases were using high-dose pills. The authors concluded that migraine of greater than 12 years’ duration, migraine with aura, and frequent migraine with aura increased the risk of stroke. “But the authors concluded themselves, in no case did corrections for oral contraceptive use alter these observations. It was not a factor,” Dr. Calhoun said.

The ACOG guideline also was based on a Danish population-based case–control study by Lidegaard et al that found a threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. In this study, however, they reported that only 6% of the control group had migraine, whereas 16% to 18% of women in Denmark have migraine—a rate similar to what was seen in the cases. That produced the threefold increased risk reported in the study, Dr. Calhoun said. A similar study in France did not find increased risk among migraineurs using oral contraceptives, but in that study, both controls and migraineurs had the normal frequency of migraine in the population.

Finally, the ACOG recommendation was based on a pooled analysis of two large US case–control studies that found a twofold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. This finding by Schwartz et al was based on only four cases. The prevalence of migraine was virtually identical among ischemic stroke cases and controls who were using oral contraceptives (7.8% and 7.7%, respectively), but became significant after adjustment for other factors. But a key factor that was not taken into account was use of high-dose (≥ 50 μg EE) pills, Dr. Calhoun said. They were used by only 11 of the 1,564 ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke cases and controls, but accounted for four of the strokes.

Low Doses Appear Safe

Recent studies have had similar findings. A 15-year prospective population-based study by Lidegaard et al in 2012 analyzed 3,300 thrombotic strokes and 1,700 myocardial infarctions in more than 1.6 million women. The overall risk was low, and the absolute risk of thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction was not increased with 20-μg pills. Pills with doses of 30 μg to 40 μg, however, as much as doubled the risk. “It is still better than the 4.5-times increased risk we had with the 50-μg pills, but we do not want to go there,” Dr. Calhoun said.

A 2013 study by Sidney et al compared a 20-μg oral birth control pill with a 30-μg oral birth control pill, a 20-μg patch birth control product, and a 15-μg ring birth control product. As expected, the 30-μg pill increased risk of thrombotic events, relative to the 20-μg pill, whereas the other products did not, Dr. Calhoun said.

“The argument against using combined hormonal contraceptives in migraine with aura is based on concerns that all women are at increased risk of stroke with oral contraceptives. That is false,” she said. “It is high-dose oral contraceptives that increase the risk.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1453-1472.

Calhoun A, Ford S, Pruitt A. The impact of extended-cycle vaginal ring contraception on migraine aura: a retrospective case series. Headache. 2012;52(8):1246-1253.

Hannaford PC, Croft PR, Kay CR. Oral contraception and stroke. Evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception study. Stroke. 1994;25(5):935-942.

Ischaemic stroke and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1996;348(9026):498-505.

Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65(3):197-205.

Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2257-2266.

MacGregor EA. Contraception and headache. Headache. 2013;53(2):247-276.

Oral contraceptives and stroke in young women. Associated risk factors. JAMA. 1975;231(7):718-722.

Petitti DB, Sidney S, Bernstein A, et al. Stroke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8-15.

Schwartz SM, Petitti DB, Siscovick DS, et al. Stroke and use of low-dose oral contraceptives in young women: a pooled analysis of two US studies. Stroke. 1998;29(11):2277-2284.

Sidney S, Cheetham TC, Connell FA, et al. Recent combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of thromboembolism and other cardiovascular events in new users. Contraception. 2013;87(1):93-100.

Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47(1):27-37.

Sulak PJ, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):261-266.

SAN DIEGO—Among women with migraine, low-dose combined estrogen–progestin contraceptives do not increase the risk of stroke, and continuous hormonal contraceptive use may reduce menstrual migraine, according to a lecture delivered at the 58th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society.

High doses of combined oral contraceptives do increase stroke risk, and migraine with aura confers an independent increased risk of stroke, said Anne H. Calhoun, MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and partner and cofounder of the Carolina Headache Institute in Durham. Evidence does not suggest, however, that low-dose hormonal contraceptive use together with history of migraine confers additive risk, she said.

Over the last several decades, various combined oral contraceptive regimens (eg, triphasic, extended cycle, and continuous) with a range of estrogen doses have been developed. “They are all over the place, and we really need to know what we are dealing with,” Dr. Calhoun said. Risks of combined oral contraceptives, including myocardial infarction and stroke, are almost exclusively seen with smoking and high-dose pills, she said.

Dr. Calhoun prefers to prescribe pills that inhibit ovulation while using 20 μg or less of the synthetic estrogen ethinyl estradiol (EE) for women at increased risk of stroke. The highest dose pill in the United States contains 50 μg of estrogen. The lowest dose pill contains 10 μg.

Placebo Side Effects

In hormonal contraception, headache often develops during the placebo week. A typical contraceptive regimen includes 21 active pills and seven placebo pills. Sulak et al found that 70% of women taking birth control pills had headache during the placebo week, and peak incidence of headache was on the third day of the placebo week. “When you eliminated the placebo week, it improved mood scores, improved headache scores, there was less dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain,” Dr. Calhoun said.

When estrogen concentrations decrease upon taking placebo, 5HT concentration in the CNS declines, serotonin synthesis declines, monoamine oxidase and calcitonin gene-related peptide concentrations increase, and beta endorphins decline. “All pain is perceived as more intense,” she said. Furthermore, flow-mediated vasodilation parallels estrogen levels.

“You would think looking at all this, in a field where most of the patients are women, and the majority of them have menstrual migraine, and all of these things happen when estrogen falls, that headache specialists would be really interested in preventing estrogen from declining every month,” Dr. Calhoun said.

Reducing Migraine

In 2012, Dr. Calhoun and colleagues published a retrospective database review that identified 23 women in a subspecialty menstrual migraine clinic who had migraine with aura, a confirmed diagnosis of menstrual-related migraine, and who received treatment with extended-cycle dosing of a transvaginal ring contraceptive containing 0.120 mg of etonogestrel and 15 μg of EE for at least a month. The women were treated with the transvaginal ring for the purpose of migraine prevention, and not to prevent pregnancy. Participants were observed for an average of eight months. Women used the ultralow-dose ring contraceptive continuously. Instead of using the ring for three weeks followed by one week without the ring, women replaced the ring every three weeks. “With that, you stop ovulation with a level of estrogen that is lower than your own natural menstrual cycle. You do not have the high ovulatory peaks or even the peaks of the luteal phase,” she said.

At baseline, subjects experienced a median of 3.2 auras per month. With treatment, the median number of auras per month decreased to 0.2. Frequency of aura decreased from baseline for each participant, and menstrual migraine was eliminated in 91.3% of patients. Such use of hormonal contraceptives for the prevention of migraine is off label, Dr. Calhoun noted.

Risk of Stroke

How oral contraceptives affect risk of stroke has been studied for decades. In a 1975 study in JAMA, researchers looked at 140 cases of stroke in young women and compared them with hospital controls. There was a 4.6 times increased risk of stroke if a woman was taking high-dose oral contraceptives.

Hannaford et al in 1994 published a nested case–control analysis using data mainly from the 1970s and 1980s. They found that high-dose oral contraceptive use was associated with a sixfold increased risk of first stroke. Low-dose pills—including 30-μg and 35-μg pills, “which I do not think of as particularly low dose these days”—did not significantly increase risk, Dr. Calhoun said. However, the risk with these moderate-dose pills is usually around 1.2 to 2.5 times greater and is significant in some studies, she noted. Today’s “low-dose” pills (≤ 20 μg EE) are the best for decreasing risk.

In 1996, a study by Petitti et al looked at risk of stroke with “low-dose” (at that time meaning simply < 50 μg EE) hormonal contraceptives in the US. They identified 408 strokes in 3.6 million women-years and concluded that stroke is rare in this population. Low-dose pills did not increase the risk. At that time, 99.4% of prescriptions for hormonal contraception in the US contained less than 50 μg of estrogen.

ACOG Guideline

In 2006, however, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommended against using combination hormonal contraceptives in patients with migraine with aura. This guideline and some of the studies on which the recommendation was based are problematic, Dr. Calhoun said.

The recommendation stemmed in part from a concern that all women with migraine are at increased risk of stroke if they take combined hormonal contraceptives. That concern was based on a 1996 World Health Organization study that had no US sites. In the study, the majority of stroke cases were smokers and the average age was over 35. In the US, 35 tends to be the age at which physicians—in accordance with ACOG recommendations—no longer prescribe combined hormonal contraceptives for smokers, Dr. Calhoun said. In addition, the majority of the stroke cases were using high-dose pills. The authors concluded that migraine of greater than 12 years’ duration, migraine with aura, and frequent migraine with aura increased the risk of stroke. “But the authors concluded themselves, in no case did corrections for oral contraceptive use alter these observations. It was not a factor,” Dr. Calhoun said.

The ACOG guideline also was based on a Danish population-based case–control study by Lidegaard et al that found a threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. In this study, however, they reported that only 6% of the control group had migraine, whereas 16% to 18% of women in Denmark have migraine—a rate similar to what was seen in the cases. That produced the threefold increased risk reported in the study, Dr. Calhoun said. A similar study in France did not find increased risk among migraineurs using oral contraceptives, but in that study, both controls and migraineurs had the normal frequency of migraine in the population.

Finally, the ACOG recommendation was based on a pooled analysis of two large US case–control studies that found a twofold increased risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs using oral contraceptives. This finding by Schwartz et al was based on only four cases. The prevalence of migraine was virtually identical among ischemic stroke cases and controls who were using oral contraceptives (7.8% and 7.7%, respectively), but became significant after adjustment for other factors. But a key factor that was not taken into account was use of high-dose (≥ 50 μg EE) pills, Dr. Calhoun said. They were used by only 11 of the 1,564 ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke cases and controls, but accounted for four of the strokes.

Low Doses Appear Safe

Recent studies have had similar findings. A 15-year prospective population-based study by Lidegaard et al in 2012 analyzed 3,300 thrombotic strokes and 1,700 myocardial infarctions in more than 1.6 million women. The overall risk was low, and the absolute risk of thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction was not increased with 20-μg pills. Pills with doses of 30 μg to 40 μg, however, as much as doubled the risk. “It is still better than the 4.5-times increased risk we had with the 50-μg pills, but we do not want to go there,” Dr. Calhoun said.

A 2013 study by Sidney et al compared a 20-μg oral birth control pill with a 30-μg oral birth control pill, a 20-μg patch birth control product, and a 15-μg ring birth control product. As expected, the 30-μg pill increased risk of thrombotic events, relative to the 20-μg pill, whereas the other products did not, Dr. Calhoun said.

“The argument against using combined hormonal contraceptives in migraine with aura is based on concerns that all women are at increased risk of stroke with oral contraceptives. That is false,” she said. “It is high-dose oral contraceptives that increase the risk.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1453-1472.

Calhoun A, Ford S, Pruitt A. The impact of extended-cycle vaginal ring contraception on migraine aura: a retrospective case series. Headache. 2012;52(8):1246-1253.

Hannaford PC, Croft PR, Kay CR. Oral contraception and stroke. Evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception study. Stroke. 1994;25(5):935-942.

Ischaemic stroke and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1996;348(9026):498-505.

Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65(3):197-205.

Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2257-2266.

MacGregor EA. Contraception and headache. Headache. 2013;53(2):247-276.

Oral contraceptives and stroke in young women. Associated risk factors. JAMA. 1975;231(7):718-722.

Petitti DB, Sidney S, Bernstein A, et al. Stroke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8-15.

Schwartz SM, Petitti DB, Siscovick DS, et al. Stroke and use of low-dose oral contraceptives in young women: a pooled analysis of two US studies. Stroke. 1998;29(11):2277-2284.

Sidney S, Cheetham TC, Connell FA, et al. Recent combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of thromboembolism and other cardiovascular events in new users. Contraception. 2013;87(1):93-100.

Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47(1):27-37.

Sulak PJ, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):261-266.

Is regional anesthesia safer in CEA?

COLUMBUS, OHIO – General anesthesia during carotid endarterectomy carries almost twice the risk of complications and unplanned intubation as regional anesthesia, but the latter approach, which is not available in all hospitals, has its own issues, an analysis of procedures from a statewide database in Michigan found.

“This study is timely because of CMS [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services] initiatives tying reimbursement to specific quality measures,” Ahmad S Hussain, MD, of Wayne State University in Detroit said in reporting the study results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society.

Regional anesthesia in CEA emerged in the 1990s, Dr. Hussain said, and allows for more reliable neurologic monitoring and more direct evaluation of the need for stenting during CEA than general anesthesia, which requires continuous monitoring of cerebral perfusion with carotid stump pressures, electroencephalogram, and transcranial doppler.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 4,558 patients who had CEA at hospitals participating in the Michigan Surgical Quality Cooperative from 2012 to 2014 – 4,008 of whom had general anesthesia and 550 regional anesthesia.

“Advocates for carotid endarterectomy with regional anesthesia cite a reduction in hemodynamic instability and the ability for neurological monitoring, but many still prefer general anesthesia because the benefits of regional anesthesia have not been clearly demonstrated, allowing that regional anesthesia may not be available in all centers and allowing that a certain amount of patient movement during the procedure may not be uniformly tolerated,” Dr. Hussain said.

General anesthesia patients in the study had more than twice the rate of any morbidity at 30 days than those who had regional, 8.7% vs. 4.2%, and significantly higher rates of unplanned intervention, 2.1% vs. 0.6%. Dr. Hussain said. However, the study could not determine differences in 30-day mortality or other key outcomes, such as rates of pneumonia, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism, becauseof insufficient sample sizes, Dr. Hussain said

The study found less significant differences between general and regional anesthesia techniques, respectively, in rates of extended length of stay, 12.1% vs. 9.5%; readmissions, 9.2% vs. 6.1%; and reoperation, 4.5% vs. 3%.

The retrospective study used two models to analyze odds ratios: Model 1 adjusted for case mix; and model 2 adjusted for case mix as fixed effects and site as a random effect. While the retrospective nature of the study may be a limitation, the findings support the use of regional anesthesia for CEA when available, Dr. Hussain said.

Dr. Hussain had no relationships to disclose.

COLUMBUS, OHIO – General anesthesia during carotid endarterectomy carries almost twice the risk of complications and unplanned intubation as regional anesthesia, but the latter approach, which is not available in all hospitals, has its own issues, an analysis of procedures from a statewide database in Michigan found.

“This study is timely because of CMS [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services] initiatives tying reimbursement to specific quality measures,” Ahmad S Hussain, MD, of Wayne State University in Detroit said in reporting the study results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society.

Regional anesthesia in CEA emerged in the 1990s, Dr. Hussain said, and allows for more reliable neurologic monitoring and more direct evaluation of the need for stenting during CEA than general anesthesia, which requires continuous monitoring of cerebral perfusion with carotid stump pressures, electroencephalogram, and transcranial doppler.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 4,558 patients who had CEA at hospitals participating in the Michigan Surgical Quality Cooperative from 2012 to 2014 – 4,008 of whom had general anesthesia and 550 regional anesthesia.

“Advocates for carotid endarterectomy with regional anesthesia cite a reduction in hemodynamic instability and the ability for neurological monitoring, but many still prefer general anesthesia because the benefits of regional anesthesia have not been clearly demonstrated, allowing that regional anesthesia may not be available in all centers and allowing that a certain amount of patient movement during the procedure may not be uniformly tolerated,” Dr. Hussain said.

General anesthesia patients in the study had more than twice the rate of any morbidity at 30 days than those who had regional, 8.7% vs. 4.2%, and significantly higher rates of unplanned intervention, 2.1% vs. 0.6%. Dr. Hussain said. However, the study could not determine differences in 30-day mortality or other key outcomes, such as rates of pneumonia, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism, becauseof insufficient sample sizes, Dr. Hussain said

The study found less significant differences between general and regional anesthesia techniques, respectively, in rates of extended length of stay, 12.1% vs. 9.5%; readmissions, 9.2% vs. 6.1%; and reoperation, 4.5% vs. 3%.

The retrospective study used two models to analyze odds ratios: Model 1 adjusted for case mix; and model 2 adjusted for case mix as fixed effects and site as a random effect. While the retrospective nature of the study may be a limitation, the findings support the use of regional anesthesia for CEA when available, Dr. Hussain said.

Dr. Hussain had no relationships to disclose.

COLUMBUS, OHIO – General anesthesia during carotid endarterectomy carries almost twice the risk of complications and unplanned intubation as regional anesthesia, but the latter approach, which is not available in all hospitals, has its own issues, an analysis of procedures from a statewide database in Michigan found.

“This study is timely because of CMS [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services] initiatives tying reimbursement to specific quality measures,” Ahmad S Hussain, MD, of Wayne State University in Detroit said in reporting the study results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society.

Regional anesthesia in CEA emerged in the 1990s, Dr. Hussain said, and allows for more reliable neurologic monitoring and more direct evaluation of the need for stenting during CEA than general anesthesia, which requires continuous monitoring of cerebral perfusion with carotid stump pressures, electroencephalogram, and transcranial doppler.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 4,558 patients who had CEA at hospitals participating in the Michigan Surgical Quality Cooperative from 2012 to 2014 – 4,008 of whom had general anesthesia and 550 regional anesthesia.

“Advocates for carotid endarterectomy with regional anesthesia cite a reduction in hemodynamic instability and the ability for neurological monitoring, but many still prefer general anesthesia because the benefits of regional anesthesia have not been clearly demonstrated, allowing that regional anesthesia may not be available in all centers and allowing that a certain amount of patient movement during the procedure may not be uniformly tolerated,” Dr. Hussain said.

General anesthesia patients in the study had more than twice the rate of any morbidity at 30 days than those who had regional, 8.7% vs. 4.2%, and significantly higher rates of unplanned intervention, 2.1% vs. 0.6%. Dr. Hussain said. However, the study could not determine differences in 30-day mortality or other key outcomes, such as rates of pneumonia, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism, becauseof insufficient sample sizes, Dr. Hussain said

The study found less significant differences between general and regional anesthesia techniques, respectively, in rates of extended length of stay, 12.1% vs. 9.5%; readmissions, 9.2% vs. 6.1%; and reoperation, 4.5% vs. 3%.

The retrospective study used two models to analyze odds ratios: Model 1 adjusted for case mix; and model 2 adjusted for case mix as fixed effects and site as a random effect. While the retrospective nature of the study may be a limitation, the findings support the use of regional anesthesia for CEA when available, Dr. Hussain said.

Dr. Hussain had no relationships to disclose.

AT MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2016

Key clinical point: General anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy carries a higher risk of complications and readmissions than regional anesthesia.

Major finding: Any morbidity after CEA with general anesthesia was 8.7% vs. 4.2% for regional anesthesia, and readmissions rates were 9.2% vs. 6.1%.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 4,558 patients who had CEA between 2012 and 2014 at hospitals participating in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative database.

Disclosures: Dr. Hussain reported having no financial disclosures.

Another Zika vaccine heads to Phase I trials

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Low parental confidence in HPV vaccine stymies adolescent vaccination rates

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Key clinical point:

Major finding: HPV vaccine refusal rate was 28% in parents of teens and preteens; the rate of vaccine delay was 8%.

Data source: Online survey conducted in 2014-2015 of 1,484 U.S. parents with children between ages of 11 and 17 years.

Disclosures: Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

Malpractice Counsel: Missed Nodule

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

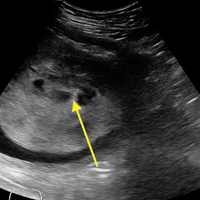

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

Case

A 48-year-old man presented to the ED with a 2-day history of cough and congestion. He described the cough as gradual in onset and, though initially nonproductive, it was now productive of green sputum. He denied fevers or chills, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, and complained of only mild shortness of breath. His medical history was significant for hypertension, which was well managed with daily lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. He admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 25 years, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 112/64 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 98oF. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral breath sounds with scattered, faint expiratory wheezing; the heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered posteroanterior and lateral chest X-rays (CXR), which he interpreted as normal. He also ordered an albuterol handheld nebulizer treatment for the patient. After the albuterol treatment, the patient felt he was breathing more easily. The frequency of his cough had also decreased following treatment and, on re-examination, he exhibited no wheezing and was given azithromycin 500 mg orally in the ED. The EP diagnosed the patient with acute bronchitis and discharged him home with an albuterol metered dose inhaler with a spacer, and a 4-day course of azithromycin. He also encouraged the patient to quit smoking.

The next day the radiologist’s official reading of the patient’s radiographs included the finding of a very small pulmonary nodule, which was seen only on the lateral X-ray. The radiologist recommended a repeat CXR or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest in 6 months.

Unfortunately, the EP never saw this information, and the patient was not contacted regarding the abnormal radiology finding and the need for follow-up. Approximately 20 months later, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis to the thoracic spine and liver. Despite chemotherapy and radiation treatment, he died from the cancer.

The patient’s family brought a malpractice suit against the EP, stating that the cancer could have been successfully treated prior to any metastasis if the patient had been informed of the abnormal radiology findings at his ED visit 20 months prior. The EP argued that he never saw the official radiology report, and therefore had no knowledge of the need for follow-up. At trial, a jury verdict was returned in favor of the defendant.

Discussion

Unfortunately, some version of this scenario occurs on a frequent basis. While imaging studies account for the majority of such cases, the same situation can occur with abnormal laboratory results, body-fluid cultures, or pathology reports in which an abnormality is identified (eg, positive blood culture, missed fracture) but, for a myriad of reasons, the critical information does not get related to the patient.

Because of the episodic nature of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), a process must be in place to ensure any “positive” test results or findings discovered after patient discharge are reviewed and compared to the ED diagnosis, and that any “misses” result in notifying the patient and/or his or her primary care physician and arranging follow-up. In cases such as the one presented here, a system issue existed—one that was not due to any fault or oversight of the EP. Ideally, EM leadership should work closely with leadership from radiology and laboratory services and hospital risk management to develop such a process—one that will be effective every day, including weekends and holidays.

Missed fractures on radiographs are a common cause of malpractice litigation against EPs. In one review by Kachalia et al1 examining malpractice claims involving EPs, missed fractures on radiographs accounted for 19% (the most common) of the 79 missed diagnoses identified in their study.In a similar study by Karcz et al,2 missed fractures ranked second in frequency and dollars lost in malpractice cases against EPs in Massachusetts.

While missed lesions on CXR do not occur with the same frequency as missed fractures, the results are much more devastating when the lesion turns out to be malignant. Three common areas where such lesions are missed on CXR include: the apex of the lung, obscured by overlying clavicle and ribs; the retrocardiac region (as in the patient in this case); and the lung bases obscured by the diaphragm.

Emergency physicians are neither trained nor expected to identify every single abnormality—especially subtle radiographic abnormalities. This is why there are radiology overreads, and a system or process must be in place to ensure patients are informed of any positive findings and to arrange proper follow-up.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

1. Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196-205.

2. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341-345.

Emergency Ultrasound: Ultrasound-Guided Femoral Nerve Block

Case Scenario

A young man presented to the ED for evaluation of a large laceration to the anterior thigh that resulted from an industrial accident (Figure 1).

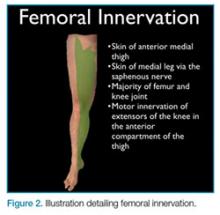

Femoral nerve blocks are useful in a variety of clinical scenarios, including fractures of the femur or hip1 and laceration repairs (Figure 2).

Identifying the Femoral Nerve on Ultrasound

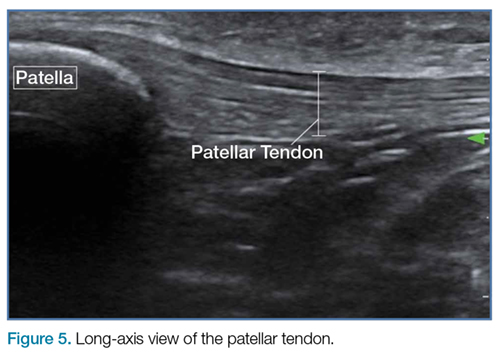

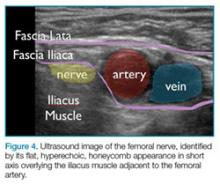

To perform this nerve block, one must recall the anatomy of femoral central-line placement. The femoral nerve lies lateral to the femoral artery and vein. The high-frequency probe should be placed over the femoral crease (Figure 3).

Performing the Block

An ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block can be performed using a 22-gauge blunt tip spinal needle, and an in-plane or out-of-plane technique can be employed. We prefer using an in-plane technique because the entire shaft of the needle can be visualized as it approaches the nerve. Anatomically, the femoral nerve lies in a separate fascial plane from the artery and vein, beneath the fascia iliaca (Figure 4). You can use this anatomic location of the femoral nerve to your advantage when performing the block. The needle can be advanced to a target slightly lateral to the nerve until it pops beneath the fascia iliaca. On the ultrasound, you can monitor the spread of anesthetic as it is injected. If the needle is in the right location, the hypoechoic fluid will spread medially toward the nerve, but will not track around the artery or vein. At least 15 cc to 20 cc of local anesthetic is typically required.2,3 If you prefer, the anesthetic can be diluted in normal saline, in a 1:1 ratio, to achieve adequate volume.

If you do not see the anesthetic spread during the injection, you should stop and check the needle placement, as it may be intravascular. Using a more lateral approach, targeting the injection at the fascial plane, rather than the nerve, helps to avoid direct intraneural injection or contact with the nerve—and it keeps the needle far away from the femoral vascular bundle.

Safety Considerations

As with any technique, prior to the procedure, aseptic measures should be taken, including the use of a sterile probe cover and sterile gloves. All patients undergoing ultrasound-guided nerve blocks proximal to the wrist or ankle should be placed on a cardiac monitor. In addition, intralipid emulsion should be readily available for administration in the unlikely event there is inadvertent intravascular injection of local anesthetic and cardiovascular collapse occurs.

Summary

With practice, ultrasound guidance can improve the procedural success of femoral nerve blocks and decrease the risk of nerve injury compared to blind nerve blocks

1. Dickman E, Pushkar I, Likourezos A, et al. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks for intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3):586-589.

2. Femoral nerve block. In: Hadzic A, Carrera A, Clark T, et al, eds. Hadzic’s Peripheral Nerve Blocks: An Anatomy for Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc; 2012:267-279.

3. Ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block. In: Hadzic A, Carrera A, Clark T, et al, eds. Hadzic’s Peripheral Nerve Blocks: An Anatomy for Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc; 2012:397-404.

Case Scenario

A young man presented to the ED for evaluation of a large laceration to the anterior thigh that resulted from an industrial accident (Figure 1).

Femoral nerve blocks are useful in a variety of clinical scenarios, including fractures of the femur or hip1 and laceration repairs (Figure 2).

Identifying the Femoral Nerve on Ultrasound

To perform this nerve block, one must recall the anatomy of femoral central-line placement. The femoral nerve lies lateral to the femoral artery and vein. The high-frequency probe should be placed over the femoral crease (Figure 3).

Performing the Block

An ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block can be performed using a 22-gauge blunt tip spinal needle, and an in-plane or out-of-plane technique can be employed. We prefer using an in-plane technique because the entire shaft of the needle can be visualized as it approaches the nerve. Anatomically, the femoral nerve lies in a separate fascial plane from the artery and vein, beneath the fascia iliaca (Figure 4). You can use this anatomic location of the femoral nerve to your advantage when performing the block. The needle can be advanced to a target slightly lateral to the nerve until it pops beneath the fascia iliaca. On the ultrasound, you can monitor the spread of anesthetic as it is injected. If the needle is in the right location, the hypoechoic fluid will spread medially toward the nerve, but will not track around the artery or vein. At least 15 cc to 20 cc of local anesthetic is typically required.2,3 If you prefer, the anesthetic can be diluted in normal saline, in a 1:1 ratio, to achieve adequate volume.

If you do not see the anesthetic spread during the injection, you should stop and check the needle placement, as it may be intravascular. Using a more lateral approach, targeting the injection at the fascial plane, rather than the nerve, helps to avoid direct intraneural injection or contact with the nerve—and it keeps the needle far away from the femoral vascular bundle.

Safety Considerations