User login

Diagnosis at a Glance: Debilitating Thigh Mass in an Obese Patient

Case

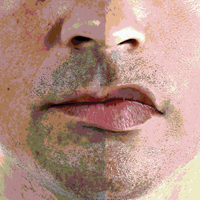

A 60-year-old morbidly obese man presented to the ED with a painless mass on his left thigh (Figure 1), which he stated had formed over a several day period 2 months earlier.

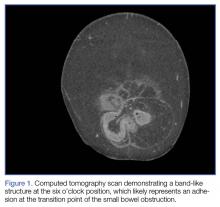

On examination, the patient appeared well, with normal vital signs and a body mass index of 56 kg/m2. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained to further evaluate the mass (Figure 2), and dermatology services were consulted.

Discussion

Massive localized lymphedema is a complication associated with morbid obesity. First described in 1998 by Farshid and Weiss,1 MLL is characterized by a benign pedunculated mass primarily of the lower extremity that slowly enlarges over years.2 The pathogenesis of MLL is currently unknown. Histologically, MLL contains lobules of mature fat with expanded connective tissue septa without the degree of cellular atypia in well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDL). Though similar to WDL, MLL can be differentiated by the clinical history of a slowly growing mass in a morbidly obese patient and examination findings of overlying reactive skin and soft-tissue changes associated with chronic lymphedema (eg, thickened peau d’orange skin).1,2

The diagnosis of MLL may be made clinically, and if there is no evidence of infection, the patient may be referred to a surgeon. If diagnostic uncertainty remains, biopsy and further CT imaging studies should be considered. The treatment for MLL is a direct excision if the mass is interfering with the patient’s gait. If left untreated, MLL can progress to angiosarcoma. Recurrence is possible, even after surgical excision.3

1. Farshid G, Weiss SW. Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese: a histologically distinct reactive lesion simulating liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(10):1277-1283.

2. Evans RJ, Scilley C. Massive localized lymphedema: A case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19(3):e30-e31.

3. Moon Y, Pyon JK. A rare case of massive localized lymphedema in a morbidly obese patient. Arch of Plast Surg. 2016;43(1):125-127. doi:10.5999/aps.2016.43.1.125.

Case

A 60-year-old morbidly obese man presented to the ED with a painless mass on his left thigh (Figure 1), which he stated had formed over a several day period 2 months earlier.

On examination, the patient appeared well, with normal vital signs and a body mass index of 56 kg/m2. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained to further evaluate the mass (Figure 2), and dermatology services were consulted.

Discussion

Massive localized lymphedema is a complication associated with morbid obesity. First described in 1998 by Farshid and Weiss,1 MLL is characterized by a benign pedunculated mass primarily of the lower extremity that slowly enlarges over years.2 The pathogenesis of MLL is currently unknown. Histologically, MLL contains lobules of mature fat with expanded connective tissue septa without the degree of cellular atypia in well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDL). Though similar to WDL, MLL can be differentiated by the clinical history of a slowly growing mass in a morbidly obese patient and examination findings of overlying reactive skin and soft-tissue changes associated with chronic lymphedema (eg, thickened peau d’orange skin).1,2

The diagnosis of MLL may be made clinically, and if there is no evidence of infection, the patient may be referred to a surgeon. If diagnostic uncertainty remains, biopsy and further CT imaging studies should be considered. The treatment for MLL is a direct excision if the mass is interfering with the patient’s gait. If left untreated, MLL can progress to angiosarcoma. Recurrence is possible, even after surgical excision.3

Case

A 60-year-old morbidly obese man presented to the ED with a painless mass on his left thigh (Figure 1), which he stated had formed over a several day period 2 months earlier.

On examination, the patient appeared well, with normal vital signs and a body mass index of 56 kg/m2. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained to further evaluate the mass (Figure 2), and dermatology services were consulted.

Discussion

Massive localized lymphedema is a complication associated with morbid obesity. First described in 1998 by Farshid and Weiss,1 MLL is characterized by a benign pedunculated mass primarily of the lower extremity that slowly enlarges over years.2 The pathogenesis of MLL is currently unknown. Histologically, MLL contains lobules of mature fat with expanded connective tissue septa without the degree of cellular atypia in well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDL). Though similar to WDL, MLL can be differentiated by the clinical history of a slowly growing mass in a morbidly obese patient and examination findings of overlying reactive skin and soft-tissue changes associated with chronic lymphedema (eg, thickened peau d’orange skin).1,2

The diagnosis of MLL may be made clinically, and if there is no evidence of infection, the patient may be referred to a surgeon. If diagnostic uncertainty remains, biopsy and further CT imaging studies should be considered. The treatment for MLL is a direct excision if the mass is interfering with the patient’s gait. If left untreated, MLL can progress to angiosarcoma. Recurrence is possible, even after surgical excision.3

1. Farshid G, Weiss SW. Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese: a histologically distinct reactive lesion simulating liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(10):1277-1283.

2. Evans RJ, Scilley C. Massive localized lymphedema: A case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19(3):e30-e31.

3. Moon Y, Pyon JK. A rare case of massive localized lymphedema in a morbidly obese patient. Arch of Plast Surg. 2016;43(1):125-127. doi:10.5999/aps.2016.43.1.125.

1. Farshid G, Weiss SW. Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese: a histologically distinct reactive lesion simulating liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(10):1277-1283.

2. Evans RJ, Scilley C. Massive localized lymphedema: A case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19(3):e30-e31.

3. Moon Y, Pyon JK. A rare case of massive localized lymphedema in a morbidly obese patient. Arch of Plast Surg. 2016;43(1):125-127. doi:10.5999/aps.2016.43.1.125.

Failure to Reduce: Small Bowel Obstruction Hidden Within a Chronic Umbilical Hernia Sac

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

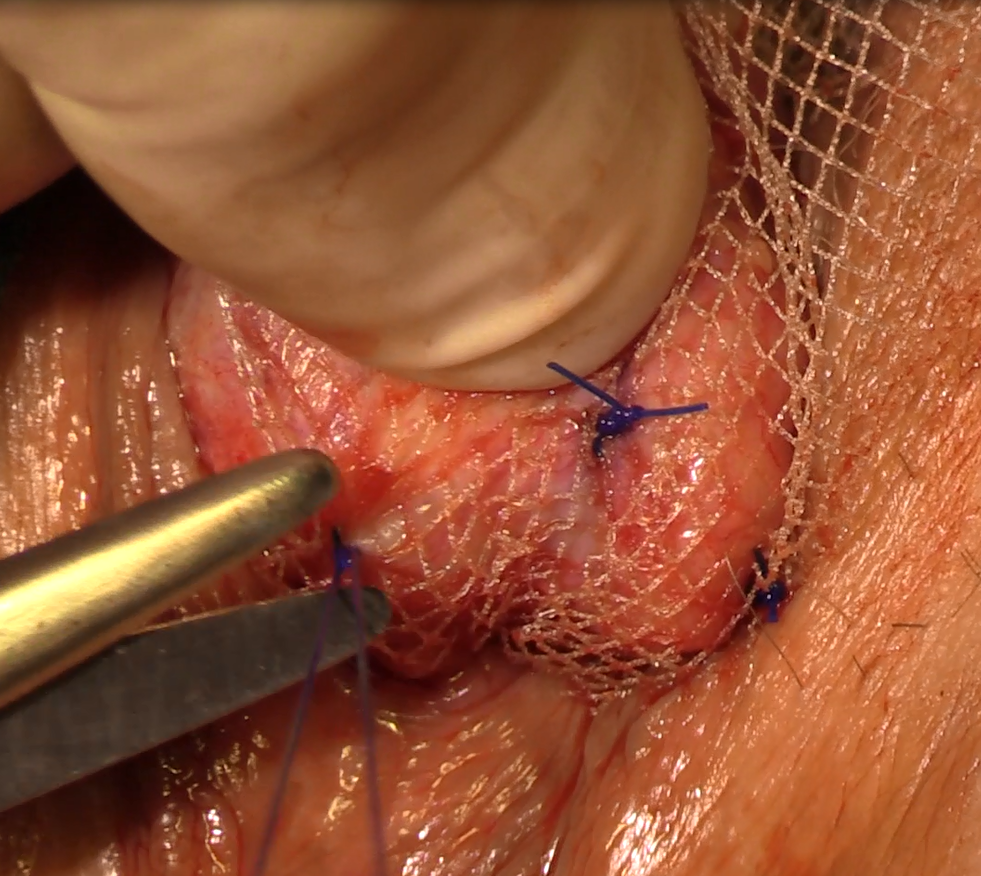

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

Strangulated hernias are a medical emergency that can lead to small bowel obstruction (SBO), bowel necrosis, and death. Practitioners look for signs of strangulation on examination to guide the urgency of management. If the hernia is soft and reducible without overlying skin changes or signs of obstruction, patients may be monitored for years.1 However, there is increasing evidence that even asymptomatic hernias should be repaired rather than monitored to avoid the need for emergent surgical intervention.1

We present a case of a patient with a chronic umbilical hernia who experienced acute worsening of pain at the site of her hernia but with few additional objective signs of strangulation. Prior to this presentation, she had been recently evaluated at our ED for the “same” pain, which included a computed tomography (CT) scan that was negative for an acute surgical emergency. The patient’s second ED visit led to a diagnostic dilemma: Practitioners are encouraged to avoid “unnecessary” radiation—especially in cases of chronic pain—and to rely on history, physical examination findings, and prior recent imaging studies, as appropriate. In this case, repeat imaging ultimately revealed a surgical emergency with an unusual underlying pathology likely related to the chronicity of the patient’s hernia, and explained her repeat presentation to the ED.

Case

A 45-year-old obese woman (body mass index, 46 kg/m2) with a medical history of an umbilical hernia, tubal ligation, and chronic pelvic pain presented a second time to our ED with pain at the site of her hernia, which she stated began 5 hours prior to presentation. Although the pain was associated with nausea and vomiting, the patient said her bowel movements were normal. She first noticed the hernia more than 5 years ago, but experienced her first episode of acute pain related to the hernia with associated nausea and vomiting 3 weeks earlier, which prompted her initial presentation. During this first ED visit, a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis was obtained as part of her evaluation and was significant for umbilical herniation of bowel without evidence of strangulation. Bedside reduction was successful, and the patient was discharged home and informed of the need to follow-up with a surgeon for an elective repair. She returned to the ED prior to her scheduled operation due to recurrent pain of similar character, but increased severity.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her vital signs were: heart rate, 84 beats/min; blood pressure, 113/68 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air.

The abdomen was soft with tenderness to palpation over a 13-cm x 8-cm soft hernia to the left of the umbilicus without overlying skin changes. The patient’s pain was controlled with 1 mg of intravenous hydromorphone, after which bedside reduction was attempted. During reduction attempts, there was palpable bowel within the hernia sac, and a periumbilical defect was appreciated. Although the defect in the abdominal wall was estimated to be large enough to allow reduction, the hernia reduced only partially. Because imaging studies from the patient’s previous ED visit showed no visualized strangulation or obstruction, we deliberated over the need for a repeat CT scan prior to further attempts at reduction by general surgery services. Ultimately, we ordered a repeat CT scan, which was significant for a “mechanical small bowel obstruction with focal transition zone located within the hernia sac itself, not the neck of the umbilical hernia.”

Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by strangulation at the neck of a hernia. In this case, however, the patient had developed an adhesion within the hernia sac itself, which caused the obstruction. This explains why none of the overlying skin changes commonly found in strangulation were visible, and why we were unable to reduce the bowel even though we could palpate the large abdominal wall defect.

Following evaluation by general surgery services, the patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair. Her case was transitioned to an open repair due to extensive intra-abdominal adhesions. The hernia was closed with mesh, and the patient recovered appropriately postoperatively.

Discussion

Abdominal wall hernias are a common pathology, with more than 700,000 repairs performed every year in the United States.2 Patients most commonly present to the ED with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Less frequently, they present with obstruction, incarceration, strangulation, or rupture.3 Umbilical hernias are caused by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. As the incidence of obesity in the United States has continued to increase, the proportion of hernias that are umbilical or periumbilical has also increased.2,4 Unfortunately, even though umbilical hernias are becoming more common, they are often given less attention than other types of hernias.5 The practice of solely monitoring umbilical hernias can lead to serious outcomes. For example, in a case presentation from Spain, a morbidly obese patient died due to a strangulated umbilical hernia that had progressed over a 15-year period without treatment.6

Compared to elective surgery, emergent operative repair is associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications,1 and a growing body of evidence suggests that patients with symptomatic hernias should be encouraged to undergo operative repair.1,6

Conclusion

Umbilical hernias have become more common with increasing rates of obesity. These hernias have the potential to lead to serious medical emergencies, and the common practice of monitoring chronic hernias may increase the patient’s risk of serious complications. Emergency physicians use the physical examination to help determine the urgency of repair; however, imaging should be considered to assess hernias that cannot easily be reduced to evaluate for obstructed, strangulated, or incarcerated bowel and to help determine the urgency of surgical repair.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

1. Davies M, Davies C, Morris-Stiff G, Shute K. Emergency presentation of abdominal hernias: outcome and reasons for delay in treatment-a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):47-50.

2. Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(1):5. doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010071.

3. Rodriguez JA, Hinder RA. Surgical management of umbilical hernia. Operat Tech Gen Surg. 2004;6(3):156-164.

4. Aslani N, Brown CJ. Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia. 2010;14(5):455-462. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.11.015.

5. Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R. Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surgery. 2001;8(10):1321-1323.

6. Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz-Feliú B, Roig-García J, Albiol-Quer M, Planellas-Giné P. Incarcerated umbilical hernia in a super-super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):893-895. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9397-3.

The Burden of COPD

Case Scenario

A 62-year-old man who regularly presented to the ED for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) after running out of his medications presented again for evaluation and treatment. His outpatient care had been poorly coordinated, and he relied on the ED to provide him with the support he needed. This presentation represented his fifth visit to the ED over the past 3 months.

The patient’s medical history was positive for asthma since childhood, tobacco use, hypertension, and a recent diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF). Over the past year, he had four hospital admissions, and was currently unable to walk from his bedroom to another room without becoming short of breath. He also had recently experienced a 20-lb weight loss.

At this visit, the patient complained of chest pain and lightheadedness, which he described as suffocating. Prior to these recent symptoms, he enjoyed walking in his neighborhood and talking with friends. He was an avid reader and sports fan, but admitted that he now had trouble focusing on reading and following games on television. He lived alone, and his family lived across the country. The patient further admitted that although he had attempted to quit cigarette smoking, he was unable to give up his 50-pack per year habit. He had no completed advance health care directive and had significant challenges tending to his basic needs.

The Trajectory of COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a common chronic illness that causes significant morbidity and mortality. A 2016 National Health Services report cited respiratory illness, primarily from COPD, as the third leading cause of death in the United States in 2014.1The trajectory of this disease is marked by frequent exacerbations with partial recovery to baseline function. The burden of those living with COPD is significant and marked by a poor overall health-related quality of life (QOL). The ED has become a staging area for patients seeking care for exacerbations of COPD.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) have defined COPD as a spectrum of diseases including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and chronic obstructive asthma characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases in the airways and lungs.3 Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity of COPD in individual patients.4

The case presented in this article illustrates the common scenario of a patient whose COPD has become severe and highly symptomatic with declining function to the point where he requires home support. His physical decline had been rapid and resulted in many unmet needs. When a patient such as this presents for emergent care, he must first be stabilized; then a care plan will need to be developed prior to discharge.

Management Goals

The overall goals of treating COPD are based on preserving function and are not curative in nature. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive illness that will intensify over time.5 As such, palliative care services are warranted. However, many patients with COPD do not receive palliative care services compared to patients with such other serious and life-limiting disease as cancer and heart disease.

Acute Exacerbations of COPD

Incidence

The frequency of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) increases with age, productive cough, long-standing COPD, previous hospitalizations related to COPD, eosinophilia, and comorbidities (eg, CHF). Patients with moderate to severe COPD and a history of prior exacerbations were found to have a higher likelihood of future exacerbations. From a quality and cost perspective, it may be useful to identify high-risk patients and strengthen their outpatient program to lessen the need for ED care and more intensive support.6,7

In our case scenario, the patient could have been stabilized at home with a well-controlled plan and home support, which would have resulted in an improved QOL and more time free from his high symptom burden.

Causes

Bacterial and viral respiratory infections are the most likely cause of AECOPD. Environmental pollution and pulmonary embolism are also triggers. Typically, patients with AECOPD present to the ED up to several times a year2 and represent the third most common cause of 30-day readmissions to the hospital.8 Prior exacerbations, dyspnea, and other medical comorbidities are also risk factors for more frequent hospital visits.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Each occurrence of AECOPD represents a worsening of a patient’s respiratory symptoms beyond normal variations. This might include increases in cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. The goal in caring for a person with an AECOPD is to stabilize the acute event and provide a treatment plan. The range of acuity for moderate to severe disease makes devising an appropriate treatment plan challenging, and after implementing the best plans, the patient’s course may be characterized by a prolonged cycle of admissions and readmissions without substantial return to baseline.

Management

In practice, ED management of AECOPD in older adults typically differs significantly from published guideline recommendations,9 which may result in pooroutcomes related to shortcomings in quality of care. Better adherence to guideline recommendations when caring for elderly patients with COPD may lead to improved clinical outcomes and better resource usage.

Risk Stratification

Complicating ED management is the challenge of determining the severity of illness and degree of the exacerbation. Airflow obstruction alone is not sufficient to predict outcomes, as any particular measure of obstruction is associated with a spectrum of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and varying performance. Moreover, peak-flow measurements are not useful in the setting of AECOPD, as opposed to their use in acute asthma exacerbations, and are not predictive of changes in clinical status.

GOLD and NICE Criteria

Guidelines have been developed and widely promoted to assist ED and hospital and community clinicians in providing evidence-based management for COPD patients. The GOLD Criteria and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) are both clinical guidelines on management of COPD.10

Although well recognized and commonly used, the original GOLD criteria did not take into account the frequency and importance of the extrapulmonary manifestations of COPD in predicting outcome. Typically, those with severe or very severe COPD have an average of 12 co-occurring symptoms, an even greater number of signs and symptoms than those occurring in patients with cancer or heart or renal disease.11

BODE Criteria

The body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise capacity (BODE) criteria assess and predict the health-related QOL and mortality risk for patients with COPD. Risk is adjusted based on four factors—weight, airway obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (ie, 6-minute walk distance).13

Initial Evaluation and Work-Up

As previously noted, when an AECOPD patient arrives to the ED, the first priority is to stabilize the patient and initiate treatment. In this respect, initial identification of the patient’s pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) is important.

Laboratory Evaluation

In cases of respiratory failure, obtaining arterial blood gas (ABG) values are critical. The ABG test will assist in determining acute exacerbations of chronic hypercapnia and the need for ventilatory support. When considering CHF, a plasma B-type natriuretic peptide is useful to assess for CHF.

Imaging Studies

A chest radiograph may be useful in the initial evaluation to identify abnormalities, including barotrauma (ie, pneumothorax) and infiltrates. Additionally, in patients with comorbidities, it is important to assess cardiac status, and a chest X-ray may assist in identification of pulmonary edema, pleural effusions, and cardiomegaly. If the radiograph does show a pulmonary infiltrate (ie, pneumonia), it will help identify the probable triggers, but even in these instances, a sputum gram stain will not assist in the diagnosis.

Treatment

Relieving airflow obstruction is achieved with inhaled short-acting bronchodilators and systemic glucocorticoids, by treating infection, and by providing supplemental oxygen and ventilatory support.

Bronchodilators

The short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists (eg, albuterol) act rapidly and are effective in producing bronchodilation. Nebulized therapy may be most comfortable for the acutely ill patient. Typical dosing is 2.5 mg albuterol diluted to 3 cc by nebulizer every hour. Higher doses are not more effective, and there is no evidence of a higher response rate from constant nebulized therapy, which can cause anxiety and tachycardia in patients.14 Anticholinergic agents (eg, ipratropium) are often added despite unclear data regarding clinical advantage. In one study evaluating the effectiveness of adding ipratropium to albuterol, patients receiving a combination had the same improvement in FEV1 at 90 minutes.15 Patients receiving ipratropium alone had the lowest rate of reported side effects.15

Systemic Glucocorticoids

Short-course systemic glucocorticoids are an important addition to treatment and have been found to improve spirometry and decrease relapse rate. The oral and intravenous (IV) routes provide the same benefit. For the acutely ill patient with challenges swallowing, the IV route is preferred. The optimal dose is not clear, but hydrocortisone doses of 100 mg to 125 mg every 6 hours for 3 days are effective, as is oral prednisone 30 mg per day for 14 days, or 60 mg per day for 3 days with a taper.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are indicated for patients with moderate to severe AECOPD who are ill enough to be admitted to the hospital. Empiric broad spectrum treatment is recommended. The initial antibiotic regimen should target likely bacterial pathogens (Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae in most patients) and take into account local patterns of antibiotic resistance. Flouroquinolones or third-generation cephalosporins generally provide sufficient coverage. For patients experiencing only a mild exacerbation, antibiotics are not warranted.

Magnesium Sulfate

Other supplemental medications that have been evaluated include magnesium sulfate for bronchial smooth muscle relaxation. Studies have found that while magnesium is helpful in asthma, results are mixed with COPD.16

Supplemental Oxygen

Oxygen therapy is important during an AECOPD episode. Often, concerns arise about decreasing respiratory drive, which is typically driven by hypoxia in patients who have chronic hypercapnia. Arterial blood gas determinations are important in managing a patient’s respiratory status and will assist in determining actual oxygenation and any coexistent metabolic disturbances.

Noninvasive Ventilation. Oxygen can be administered efficiently by a venturi mask, which delivers precise fractions of oxygen, or by nasal cannula. A facemask is less comfortable, but is available for higher oxygen requirements, providing up to 55% oxygen, while a nonrebreather mask delivers up to 90% oxygen.

When necessary, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) improves outcomes for those with severe dyspnea and signs of respiratory fatigue manifested as increased work of breathing. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation can improve clinical outcomes and is the ventilator mode of choice for those patients with COPD. Indications include severe dyspnea with signs of increased work of breathing and respiratory acidosis (arterial pH <7.35) and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) >45 mm Hg.

Whenever possible, NPPV should be initiated with a triggered mode to allow spontaneous breaths. Inspiratory pressure of 8 cm to 12 cm H2O and expiratory pressure of 3 cm to 5 cm of H2 are recommended.

Mechanical Ventilation. Mechanical ventilation is often undesirable because it may be extraordinarily difficult to wean a patient off the device and permit safe extubation. However, if a patient cannot be stabilized with NPPV, intubation and mechanical ventilation must be considered. Typically, this occurs when there is severe respiratory distress, tachypnea >30 breaths/min, accessory muscle use, and altered mentation.

Goals of intubation/mechanical respiration include correcting oxygenation and severe respiratory acidosis as well as reducing the work of breathing. Barotrauma is a significant risk when patients with COPD require mechanical ventilation. Volume-limited modes of ventilation are commonly used, while pressure support or pressure-limited modes are less suitable for patients with airflow limitation. Again, invasive ventilation should only be administered if a patient cannot tolerate NPPV.

Palliative Care in the ED

Palliative care is an approach that improves the QOL of patients and their families facing the issues associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and accurate assessment and treatment of pain and physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.3 This approach to care is warranted for COPD patients given the myriad of burdensome symptoms and functional decline that occurs.17

Palliative care expands traditional treatment goals to include enhancing QOL; helping with medical decision making; and identifying the goals of care. Palliative care is provided by board-certified physicians for the most complex of cases. However, the primary practice of palliative care must be delivered at the bedside by the treating provider. Managing pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel habits, as well as discussing goals of care, are among the basic palliative care skills all providers need to have and apply when indicated.

Palliative Care for Dyspnea

Opioids. Primary palliative care in the ED includes the appropriate use of low-dose oral and parenteral opioids to treat dyspnea in AECOPD. The use of a low-dose opioid, such as morphine 2 mg IV, titrated up to a desired response, is a safe and effective practice.18 Note the 2-mg starting dose is considered low-dose.19

With respect to managing dyspnea in AECOPD patients, nebulized opioids have not been found to be better than nebulized saline. More specific data regarding the use of oral opioids for managing refractory dyspnea in patients with predominantly COPD have been recently published: Long-acting morphine 20 mg once daily provides symptomatic relief in refractory dyspnea in the community setting. For the opioid-naïve patient, a lower dose is recommended.20

Oxygenation. There is no hard evidence of the effectiveness of oxygen in the palliation of breathlessness. Humidified air is effective initially, as is providing a fan at the bedside. Short-burst oxygen therapy should only be considered for episodes of severe breathlessness in patients whose COPD is not relieved by other treatments. Oxygen should continue to be prescribed only if an improvement in breathlessness following therapy has been documented. The American Thoracic Society recommends continuous oxygen therapy in patients with COPD who have severe resting hypoxemia (PaCO2 ≤55 mm Hg or SpO2 ≤88%).21

POLST Form

The Physicians Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form is a set of medical orders, similar to the “do not resuscitate” (allow natural death) order. A POLST form is not an advance directive and does not serve as a substitute for a patient’s assignation of a health care agent or durable power of attorney for health care.22

The POLST form enables physicians to order treatments patients would want, identify those treatments that patients would not want, and not provide those the patient considers “extraordinary” and excessively burdensome. A POLST form does not allow for active euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

Identifying treatment preferences is an important part of the initial evaluation of all patients. When dealing with an airway issue in a COPD patient, management can become complex. Ideally, the POLST form should arrive with the patient in the ED and list preferences regarding possible intensive interventions such as intubation and chest compressions. Discussing these issues with a patient in extreme distress is difficult or impossible, and in these cases, access to pertinent medical records, discussing preferences with family caregivers, and availability of a POLST form are much better ways to determine therapy.

Palliative Home Care

Patient Safety Considerations

Weight loss and associated muscle wasting are common features in patients with severe COPD, creating a high-risk situation for falls and a need for assistance with activities of daily living. The patient who is frail when discharged home from the ED requires a home-care plan before leaving the ED, and strict follow-up with the patient’s primary care provider will typically be needed within 2 to 4 weeks.

Psychological Considerations

Being mindful of the anxiety and depression that accompany the physical limitations of those with COPD is important. Mood disturbances serve as risk factors for re-hospitalization and mortality.13Multiple palliative care interventions provide patients assistance with these issues, including the use of antidepressants that may aid sleep, stabilize mood, and stimulate appetite.

Early referral to the palliative care team will provide improved care for the patient and family. Palliative care referral will provide continued management of the physical symptoms and evaluation and treatment of the psychosocial issues that accompany COPD. Additionally, the palliative care team can assist with safe discharge planning and follow-up, including the provision of the patient’s home needs as well as the family’s ability to cope with the home setting.

Prognosis

Predicting prognosis is difficult for the COPD patient due to the highly variable illness trajectory. Some patients have a low FEV1 and yet are very functional. However, assessment of severity of lung function impairment, frequency of exacerbations, and need for long-term oxygen therapy helps identify those patients who are entering the final 12 months of life. Evaluating symptom burden and impact on activities of daily living for patients with COPD is comparable to those of cancer patients, and in both cases, palliative care approaches are necessary.

Predicting Morbidity and Mortality

A profile developed from observational studies can help predict 6- to 12-month morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced COPD. This profile includes the following criteria:

- Significant dyspnea;

- FEV1 <30%;

- Number of exacerbations;

- Left heart failure or other comorbidities;

- Weight loss or cachexia;

- Decreasing performance status;

- Age older than 70 years; and

- Depression.

Although additional research is required to refine and verify this profile, reviewing these data points can prompt providers to initiate discussions with patients about treatment preferences and end-of-life care.23,24

Palliative Performance Scale

The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) is another scale used to predict prognosis and eligibility for hospice care.25 This score provides a patient’s estimated survival.25 For a patient with a PPS score of 50%, hospice education may be appropriate.

Case Scenario Continued

Both the BODE and GOLD criteria scores assisted in determining prognosis and risk profiles of the patient in our case scenario. By applying the BODE criteria, our patient had a 4-year survival benefit of under 18%. The GOLD criteria results for this patient also were consistent with the BODE criteria and reflected end-stage COPD. Since this patient also had a PPS score of 50%, hospice education and care were discussed and initiated.

Conclusion

Patients with AECOPD commonly present to the ED. Such patients suffer with a high burden of illness and a need for immediate symptom management. However, after these measures have been instituted, strong evidence suggests that these patients typically do not receive palliative care with the same frequency compared to cancer or heart disease patients.

Management of AECOPD in the ED must include rapid treatment of dyspnea and pain, but also a determination of treatment preferences and an understanding of the prognosis. Several criteria are available to guide prognostic awareness and may help further the goals of care and disposition. Primary palliative care should be started by the ED provider for appropriate patients, with early referral to the palliative care team.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2015 With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: US Dept. Health and Human Services; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/. Accessed October 17, 2016.

2. Khialani B, Sivakumaran P, Keijzers G, Sriram KB. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and factors associated with hospitalization. J Res Med Sci . 2014;19(4):297-303.

3. World Health Organization Web site. Chronic respiratory diseases. COPD: Definition. http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/definition/en/. Accessed October 17, 2016.

4. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al; Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2007;176(6):532-555.

5. Fan VS, Ramsey SD, Make BJ, Martinez FJ. Physiologic variables and functional status independently predict COPD hospitalizations and emergency department visits in patients with severe COPD. COPD . 2007;4(1):29-39.

6. Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Clark S, Emerman CL, Camargo CA Jr; MARC Investigators. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly: the Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2003;51(7):908-916.

7. Strassels SA, Smith DH, Sullivan SD, et al. The costs of treating COPD in the United States. Chest . 2001;119:3.

8. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med . 2009;360(14):1418-1428. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0803563.

9. Rowe BH, Bhutani M, Stickland MK, Cydulka R. Assessment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the emergency department and beyond. Expert Rev Respir Med . 2011;5(4):549-559. doi:10.1586/ers.11.43.

10. National Institute for Clinical Excellence Web site. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical Guideline CG101. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/cg101. Published June 2010. Accessed October 17, 2016.

11. Christensen VL, Holm AM, Cooper B, Paul SM, Miaskowski C, Rustøen T. Differences in symptom burden among patients with moderate, severe, or very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2016;51(5):849-859. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.324.

12. GOLD Reports. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. http://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/. Accessed October 17, 2016.

13. Funk GC, Kirchheiner K, Burghuber OC, Hartl S. BODE index versus GOLD classification for explaining anxious and depressive symptoms in patients with COPD—a cross-sectional study. Respir Res . 2009;10:1. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-10-1.

14. Bach PB, Brown C, Gelfand SE, McCrory DC; American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; American College of Chest Physicians. Management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a summary and appraisal of published evidence. Ann Intern Med . 2001;134(7):600-620.

15. McCrory DC, Brown CD. Inhaled short-acting beta 2-agonists versus ipratropium for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2001;(2):CD002984.

16. Shivanthan MC, Rajapakse S. Magnesium for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review of randomised trials. Ann Thorac Med . 2014;9(2):77-80. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.128844.

17. Curtis JR. Palliative and end of life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J . 2008;32(3):796-803.

18. Rocker GM, Simpson AC, Young J, et al. Opioid therapy for refractory dyspnea in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patients’ experiences and outcomes. CMAJ Open . 2013;1(1):E27-E36.

19. Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, Gibbs JS, Broadley KE. A systematic review of the use of opioids in the management of dyspnea. Thorax . 2002;57(11):939-944.

20. Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Frith P, Fazekas BS, McHugh A, Bui C. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial of sustained release morphine for the management of refractory dyspnoea. BMJ . 2003;327(7414):523-528.

21. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med . 2011;155(3):179-191. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008.

22. National POLST Paradigm. http://polst.org/professionals-page/?pro=1. Accessed October 17, 2016.

23. Hansen-Flaschen J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the last year of life. Respir Care. 2004;49(1):90-97; discussion 97-98.

24. Spathis A, Booth S. End of life care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: in search of a good death. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2008;3(1):11-29.

25. Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care . 1996;12(1):5-11.

Case Scenario

A 62-year-old man who regularly presented to the ED for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) after running out of his medications presented again for evaluation and treatment. His outpatient care had been poorly coordinated, and he relied on the ED to provide him with the support he needed. This presentation represented his fifth visit to the ED over the past 3 months.

The patient’s medical history was positive for asthma since childhood, tobacco use, hypertension, and a recent diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF). Over the past year, he had four hospital admissions, and was currently unable to walk from his bedroom to another room without becoming short of breath. He also had recently experienced a 20-lb weight loss.

At this visit, the patient complained of chest pain and lightheadedness, which he described as suffocating. Prior to these recent symptoms, he enjoyed walking in his neighborhood and talking with friends. He was an avid reader and sports fan, but admitted that he now had trouble focusing on reading and following games on television. He lived alone, and his family lived across the country. The patient further admitted that although he had attempted to quit cigarette smoking, he was unable to give up his 50-pack per year habit. He had no completed advance health care directive and had significant challenges tending to his basic needs.

The Trajectory of COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a common chronic illness that causes significant morbidity and mortality. A 2016 National Health Services report cited respiratory illness, primarily from COPD, as the third leading cause of death in the United States in 2014.1The trajectory of this disease is marked by frequent exacerbations with partial recovery to baseline function. The burden of those living with COPD is significant and marked by a poor overall health-related quality of life (QOL). The ED has become a staging area for patients seeking care for exacerbations of COPD.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) have defined COPD as a spectrum of diseases including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and chronic obstructive asthma characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases in the airways and lungs.3 Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity of COPD in individual patients.4

The case presented in this article illustrates the common scenario of a patient whose COPD has become severe and highly symptomatic with declining function to the point where he requires home support. His physical decline had been rapid and resulted in many unmet needs. When a patient such as this presents for emergent care, he must first be stabilized; then a care plan will need to be developed prior to discharge.

Management Goals

The overall goals of treating COPD are based on preserving function and are not curative in nature. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive illness that will intensify over time.5 As such, palliative care services are warranted. However, many patients with COPD do not receive palliative care services compared to patients with such other serious and life-limiting disease as cancer and heart disease.

Acute Exacerbations of COPD

Incidence

The frequency of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) increases with age, productive cough, long-standing COPD, previous hospitalizations related to COPD, eosinophilia, and comorbidities (eg, CHF). Patients with moderate to severe COPD and a history of prior exacerbations were found to have a higher likelihood of future exacerbations. From a quality and cost perspective, it may be useful to identify high-risk patients and strengthen their outpatient program to lessen the need for ED care and more intensive support.6,7

In our case scenario, the patient could have been stabilized at home with a well-controlled plan and home support, which would have resulted in an improved QOL and more time free from his high symptom burden.

Causes

Bacterial and viral respiratory infections are the most likely cause of AECOPD. Environmental pollution and pulmonary embolism are also triggers. Typically, patients with AECOPD present to the ED up to several times a year2 and represent the third most common cause of 30-day readmissions to the hospital.8 Prior exacerbations, dyspnea, and other medical comorbidities are also risk factors for more frequent hospital visits.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Each occurrence of AECOPD represents a worsening of a patient’s respiratory symptoms beyond normal variations. This might include increases in cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. The goal in caring for a person with an AECOPD is to stabilize the acute event and provide a treatment plan. The range of acuity for moderate to severe disease makes devising an appropriate treatment plan challenging, and after implementing the best plans, the patient’s course may be characterized by a prolonged cycle of admissions and readmissions without substantial return to baseline.

Management

In practice, ED management of AECOPD in older adults typically differs significantly from published guideline recommendations,9 which may result in pooroutcomes related to shortcomings in quality of care. Better adherence to guideline recommendations when caring for elderly patients with COPD may lead to improved clinical outcomes and better resource usage.

Risk Stratification

Complicating ED management is the challenge of determining the severity of illness and degree of the exacerbation. Airflow obstruction alone is not sufficient to predict outcomes, as any particular measure of obstruction is associated with a spectrum of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and varying performance. Moreover, peak-flow measurements are not useful in the setting of AECOPD, as opposed to their use in acute asthma exacerbations, and are not predictive of changes in clinical status.

GOLD and NICE Criteria

Guidelines have been developed and widely promoted to assist ED and hospital and community clinicians in providing evidence-based management for COPD patients. The GOLD Criteria and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) are both clinical guidelines on management of COPD.10

Although well recognized and commonly used, the original GOLD criteria did not take into account the frequency and importance of the extrapulmonary manifestations of COPD in predicting outcome. Typically, those with severe or very severe COPD have an average of 12 co-occurring symptoms, an even greater number of signs and symptoms than those occurring in patients with cancer or heart or renal disease.11

BODE Criteria

The body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise capacity (BODE) criteria assess and predict the health-related QOL and mortality risk for patients with COPD. Risk is adjusted based on four factors—weight, airway obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (ie, 6-minute walk distance).13

Initial Evaluation and Work-Up

As previously noted, when an AECOPD patient arrives to the ED, the first priority is to stabilize the patient and initiate treatment. In this respect, initial identification of the patient’s pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) is important.

Laboratory Evaluation

In cases of respiratory failure, obtaining arterial blood gas (ABG) values are critical. The ABG test will assist in determining acute exacerbations of chronic hypercapnia and the need for ventilatory support. When considering CHF, a plasma B-type natriuretic peptide is useful to assess for CHF.

Imaging Studies

A chest radiograph may be useful in the initial evaluation to identify abnormalities, including barotrauma (ie, pneumothorax) and infiltrates. Additionally, in patients with comorbidities, it is important to assess cardiac status, and a chest X-ray may assist in identification of pulmonary edema, pleural effusions, and cardiomegaly. If the radiograph does show a pulmonary infiltrate (ie, pneumonia), it will help identify the probable triggers, but even in these instances, a sputum gram stain will not assist in the diagnosis.

Treatment

Relieving airflow obstruction is achieved with inhaled short-acting bronchodilators and systemic glucocorticoids, by treating infection, and by providing supplemental oxygen and ventilatory support.

Bronchodilators

The short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists (eg, albuterol) act rapidly and are effective in producing bronchodilation. Nebulized therapy may be most comfortable for the acutely ill patient. Typical dosing is 2.5 mg albuterol diluted to 3 cc by nebulizer every hour. Higher doses are not more effective, and there is no evidence of a higher response rate from constant nebulized therapy, which can cause anxiety and tachycardia in patients.14 Anticholinergic agents (eg, ipratropium) are often added despite unclear data regarding clinical advantage. In one study evaluating the effectiveness of adding ipratropium to albuterol, patients receiving a combination had the same improvement in FEV1 at 90 minutes.15 Patients receiving ipratropium alone had the lowest rate of reported side effects.15

Systemic Glucocorticoids

Short-course systemic glucocorticoids are an important addition to treatment and have been found to improve spirometry and decrease relapse rate. The oral and intravenous (IV) routes provide the same benefit. For the acutely ill patient with challenges swallowing, the IV route is preferred. The optimal dose is not clear, but hydrocortisone doses of 100 mg to 125 mg every 6 hours for 3 days are effective, as is oral prednisone 30 mg per day for 14 days, or 60 mg per day for 3 days with a taper.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are indicated for patients with moderate to severe AECOPD who are ill enough to be admitted to the hospital. Empiric broad spectrum treatment is recommended. The initial antibiotic regimen should target likely bacterial pathogens (Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae in most patients) and take into account local patterns of antibiotic resistance. Flouroquinolones or third-generation cephalosporins generally provide sufficient coverage. For patients experiencing only a mild exacerbation, antibiotics are not warranted.

Magnesium Sulfate

Other supplemental medications that have been evaluated include magnesium sulfate for bronchial smooth muscle relaxation. Studies have found that while magnesium is helpful in asthma, results are mixed with COPD.16

Supplemental Oxygen

Oxygen therapy is important during an AECOPD episode. Often, concerns arise about decreasing respiratory drive, which is typically driven by hypoxia in patients who have chronic hypercapnia. Arterial blood gas determinations are important in managing a patient’s respiratory status and will assist in determining actual oxygenation and any coexistent metabolic disturbances.

Noninvasive Ventilation. Oxygen can be administered efficiently by a venturi mask, which delivers precise fractions of oxygen, or by nasal cannula. A facemask is less comfortable, but is available for higher oxygen requirements, providing up to 55% oxygen, while a nonrebreather mask delivers up to 90% oxygen.

When necessary, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) improves outcomes for those with severe dyspnea and signs of respiratory fatigue manifested as increased work of breathing. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation can improve clinical outcomes and is the ventilator mode of choice for those patients with COPD. Indications include severe dyspnea with signs of increased work of breathing and respiratory acidosis (arterial pH <7.35) and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) >45 mm Hg.

Whenever possible, NPPV should be initiated with a triggered mode to allow spontaneous breaths. Inspiratory pressure of 8 cm to 12 cm H2O and expiratory pressure of 3 cm to 5 cm of H2 are recommended.

Mechanical Ventilation. Mechanical ventilation is often undesirable because it may be extraordinarily difficult to wean a patient off the device and permit safe extubation. However, if a patient cannot be stabilized with NPPV, intubation and mechanical ventilation must be considered. Typically, this occurs when there is severe respiratory distress, tachypnea >30 breaths/min, accessory muscle use, and altered mentation.

Goals of intubation/mechanical respiration include correcting oxygenation and severe respiratory acidosis as well as reducing the work of breathing. Barotrauma is a significant risk when patients with COPD require mechanical ventilation. Volume-limited modes of ventilation are commonly used, while pressure support or pressure-limited modes are less suitable for patients with airflow limitation. Again, invasive ventilation should only be administered if a patient cannot tolerate NPPV.

Palliative Care in the ED

Palliative care is an approach that improves the QOL of patients and their families facing the issues associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and accurate assessment and treatment of pain and physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.3 This approach to care is warranted for COPD patients given the myriad of burdensome symptoms and functional decline that occurs.17

Palliative care expands traditional treatment goals to include enhancing QOL; helping with medical decision making; and identifying the goals of care. Palliative care is provided by board-certified physicians for the most complex of cases. However, the primary practice of palliative care must be delivered at the bedside by the treating provider. Managing pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel habits, as well as discussing goals of care, are among the basic palliative care skills all providers need to have and apply when indicated.

Palliative Care for Dyspnea

Opioids. Primary palliative care in the ED includes the appropriate use of low-dose oral and parenteral opioids to treat dyspnea in AECOPD. The use of a low-dose opioid, such as morphine 2 mg IV, titrated up to a desired response, is a safe and effective practice.18 Note the 2-mg starting dose is considered low-dose.19

With respect to managing dyspnea in AECOPD patients, nebulized opioids have not been found to be better than nebulized saline. More specific data regarding the use of oral opioids for managing refractory dyspnea in patients with predominantly COPD have been recently published: Long-acting morphine 20 mg once daily provides symptomatic relief in refractory dyspnea in the community setting. For the opioid-naïve patient, a lower dose is recommended.20

Oxygenation. There is no hard evidence of the effectiveness of oxygen in the palliation of breathlessness. Humidified air is effective initially, as is providing a fan at the bedside. Short-burst oxygen therapy should only be considered for episodes of severe breathlessness in patients whose COPD is not relieved by other treatments. Oxygen should continue to be prescribed only if an improvement in breathlessness following therapy has been documented. The American Thoracic Society recommends continuous oxygen therapy in patients with COPD who have severe resting hypoxemia (PaCO2 ≤55 mm Hg or SpO2 ≤88%).21

POLST Form

The Physicians Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form is a set of medical orders, similar to the “do not resuscitate” (allow natural death) order. A POLST form is not an advance directive and does not serve as a substitute for a patient’s assignation of a health care agent or durable power of attorney for health care.22

The POLST form enables physicians to order treatments patients would want, identify those treatments that patients would not want, and not provide those the patient considers “extraordinary” and excessively burdensome. A POLST form does not allow for active euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

Identifying treatment preferences is an important part of the initial evaluation of all patients. When dealing with an airway issue in a COPD patient, management can become complex. Ideally, the POLST form should arrive with the patient in the ED and list preferences regarding possible intensive interventions such as intubation and chest compressions. Discussing these issues with a patient in extreme distress is difficult or impossible, and in these cases, access to pertinent medical records, discussing preferences with family caregivers, and availability of a POLST form are much better ways to determine therapy.

Palliative Home Care

Patient Safety Considerations

Weight loss and associated muscle wasting are common features in patients with severe COPD, creating a high-risk situation for falls and a need for assistance with activities of daily living. The patient who is frail when discharged home from the ED requires a home-care plan before leaving the ED, and strict follow-up with the patient’s primary care provider will typically be needed within 2 to 4 weeks.

Psychological Considerations

Being mindful of the anxiety and depression that accompany the physical limitations of those with COPD is important. Mood disturbances serve as risk factors for re-hospitalization and mortality.13Multiple palliative care interventions provide patients assistance with these issues, including the use of antidepressants that may aid sleep, stabilize mood, and stimulate appetite.

Early referral to the palliative care team will provide improved care for the patient and family. Palliative care referral will provide continued management of the physical symptoms and evaluation and treatment of the psychosocial issues that accompany COPD. Additionally, the palliative care team can assist with safe discharge planning and follow-up, including the provision of the patient’s home needs as well as the family’s ability to cope with the home setting.

Prognosis

Predicting prognosis is difficult for the COPD patient due to the highly variable illness trajectory. Some patients have a low FEV1 and yet are very functional. However, assessment of severity of lung function impairment, frequency of exacerbations, and need for long-term oxygen therapy helps identify those patients who are entering the final 12 months of life. Evaluating symptom burden and impact on activities of daily living for patients with COPD is comparable to those of cancer patients, and in both cases, palliative care approaches are necessary.

Predicting Morbidity and Mortality

A profile developed from observational studies can help predict 6- to 12-month morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced COPD. This profile includes the following criteria:

- Significant dyspnea;

- FEV1 <30%;

- Number of exacerbations;

- Left heart failure or other comorbidities;

- Weight loss or cachexia;

- Decreasing performance status;

- Age older than 70 years; and

- Depression.

Although additional research is required to refine and verify this profile, reviewing these data points can prompt providers to initiate discussions with patients about treatment preferences and end-of-life care.23,24

Palliative Performance Scale

The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) is another scale used to predict prognosis and eligibility for hospice care.25 This score provides a patient’s estimated survival.25 For a patient with a PPS score of 50%, hospice education may be appropriate.

Case Scenario Continued

Both the BODE and GOLD criteria scores assisted in determining prognosis and risk profiles of the patient in our case scenario. By applying the BODE criteria, our patient had a 4-year survival benefit of under 18%. The GOLD criteria results for this patient also were consistent with the BODE criteria and reflected end-stage COPD. Since this patient also had a PPS score of 50%, hospice education and care were discussed and initiated.

Conclusion

Patients with AECOPD commonly present to the ED. Such patients suffer with a high burden of illness and a need for immediate symptom management. However, after these measures have been instituted, strong evidence suggests that these patients typically do not receive palliative care with the same frequency compared to cancer or heart disease patients.

Management of AECOPD in the ED must include rapid treatment of dyspnea and pain, but also a determination of treatment preferences and an understanding of the prognosis. Several criteria are available to guide prognostic awareness and may help further the goals of care and disposition. Primary palliative care should be started by the ED provider for appropriate patients, with early referral to the palliative care team.

Case Scenario

A 62-year-old man who regularly presented to the ED for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) after running out of his medications presented again for evaluation and treatment. His outpatient care had been poorly coordinated, and he relied on the ED to provide him with the support he needed. This presentation represented his fifth visit to the ED over the past 3 months.

The patient’s medical history was positive for asthma since childhood, tobacco use, hypertension, and a recent diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF). Over the past year, he had four hospital admissions, and was currently unable to walk from his bedroom to another room without becoming short of breath. He also had recently experienced a 20-lb weight loss.

At this visit, the patient complained of chest pain and lightheadedness, which he described as suffocating. Prior to these recent symptoms, he enjoyed walking in his neighborhood and talking with friends. He was an avid reader and sports fan, but admitted that he now had trouble focusing on reading and following games on television. He lived alone, and his family lived across the country. The patient further admitted that although he had attempted to quit cigarette smoking, he was unable to give up his 50-pack per year habit. He had no completed advance health care directive and had significant challenges tending to his basic needs.

The Trajectory of COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a common chronic illness that causes significant morbidity and mortality. A 2016 National Health Services report cited respiratory illness, primarily from COPD, as the third leading cause of death in the United States in 2014.1The trajectory of this disease is marked by frequent exacerbations with partial recovery to baseline function. The burden of those living with COPD is significant and marked by a poor overall health-related quality of life (QOL). The ED has become a staging area for patients seeking care for exacerbations of COPD.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) have defined COPD as a spectrum of diseases including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and chronic obstructive asthma characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases in the airways and lungs.3 Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity of COPD in individual patients.4

The case presented in this article illustrates the common scenario of a patient whose COPD has become severe and highly symptomatic with declining function to the point where he requires home support. His physical decline had been rapid and resulted in many unmet needs. When a patient such as this presents for emergent care, he must first be stabilized; then a care plan will need to be developed prior to discharge.

Management Goals

The overall goals of treating COPD are based on preserving function and are not curative in nature. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive illness that will intensify over time.5 As such, palliative care services are warranted. However, many patients with COPD do not receive palliative care services compared to patients with such other serious and life-limiting disease as cancer and heart disease.

Acute Exacerbations of COPD

Incidence