User login

VIDEO: Immune checkpoint inhibitor is efficacious as first-line therapy for advanced bladder cancer

CHICAGO – Atezolizumab, an antibody that targets PD-L1, achieves a median survival of 14.8 months in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, according to findings of the IMvigor210 trial’s cohort 1. Researchers presented the findings this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In an interview at the meeting, lead author Dr. Arjun Vasant Balar of the department of medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center and director of genitourinary medical oncology at the NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center, discussed the study and its implications. In particular, he weighed in on key issues, such as whether PD-L1 status predicts benefit and where atezolizumab may ultimately fit into the treatment armamentarium for this disease.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @OncologyPractic

CHICAGO – Atezolizumab, an antibody that targets PD-L1, achieves a median survival of 14.8 months in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, according to findings of the IMvigor210 trial’s cohort 1. Researchers presented the findings this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In an interview at the meeting, lead author Dr. Arjun Vasant Balar of the department of medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center and director of genitourinary medical oncology at the NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center, discussed the study and its implications. In particular, he weighed in on key issues, such as whether PD-L1 status predicts benefit and where atezolizumab may ultimately fit into the treatment armamentarium for this disease.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @OncologyPractic

CHICAGO – Atezolizumab, an antibody that targets PD-L1, achieves a median survival of 14.8 months in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, according to findings of the IMvigor210 trial’s cohort 1. Researchers presented the findings this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In an interview at the meeting, lead author Dr. Arjun Vasant Balar of the department of medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center and director of genitourinary medical oncology at the NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center, discussed the study and its implications. In particular, he weighed in on key issues, such as whether PD-L1 status predicts benefit and where atezolizumab may ultimately fit into the treatment armamentarium for this disease.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @OncologyPractic

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Study spotlights link between mental illness, gun-related suicide

Enacting risk-based gun removal laws and prohibiting guns from people involuntarily detained in short-term psychiatric hospitalization may have a positive impact on gun-related suicide and violent crime among people with serious mental illnesses.

Those are among the recommendations published June 6 by Jeffrey W. Swanson, Ph.D., and his associates, who studied 81,704 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression in two large Florida counties between 2002 and 2011 (Health Aff. 2016 Jun 6;35[6]:1067-75. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0017).

Dr. Swanson and his associates found that 62% of arrests from gun crimes and 28% of suicides by gun involved individuals who were not legally permitted to have a gun. In addition, they found that suicide was nearly four times as prevalent among adults diagnosed with a serious mental illness, compared with their counterparts in the general population (64.4 vs.17.7 per 100,000 persons).

Also, 20% of suicides among adults with a serious mental illness were by firearm, compared with 48% of adults in the general Florida population, reported Dr. Swanson, a professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Gun violence by suicide claims the lives of 33,000 people each year in the United States, and two-thirds of the country’s gun fatalities are suicides, Dr. Swanson said in a video describing his study.

“We’re focused on laws that restrict access to guns as public health interventions,” Dr. Swanson said. “One of the things that sticks with me is there’s a lost public health opportunity, because people with mental illnesses ... who end their life in suicide often are not going to be prohibited people – they can go and legally buy a gun on the day that they use one to end their life. But many of them actually are known to the mental health care system. That’s the opportunity. States could say, ‘let’s use this as a time to separate that individual from guns.’ ”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program in Public Health Law Research, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Elizabeth K. Dollard Charitable Trust.

Enacting risk-based gun removal laws and prohibiting guns from people involuntarily detained in short-term psychiatric hospitalization may have a positive impact on gun-related suicide and violent crime among people with serious mental illnesses.

Those are among the recommendations published June 6 by Jeffrey W. Swanson, Ph.D., and his associates, who studied 81,704 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression in two large Florida counties between 2002 and 2011 (Health Aff. 2016 Jun 6;35[6]:1067-75. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0017).

Dr. Swanson and his associates found that 62% of arrests from gun crimes and 28% of suicides by gun involved individuals who were not legally permitted to have a gun. In addition, they found that suicide was nearly four times as prevalent among adults diagnosed with a serious mental illness, compared with their counterparts in the general population (64.4 vs.17.7 per 100,000 persons).

Also, 20% of suicides among adults with a serious mental illness were by firearm, compared with 48% of adults in the general Florida population, reported Dr. Swanson, a professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Gun violence by suicide claims the lives of 33,000 people each year in the United States, and two-thirds of the country’s gun fatalities are suicides, Dr. Swanson said in a video describing his study.

“We’re focused on laws that restrict access to guns as public health interventions,” Dr. Swanson said. “One of the things that sticks with me is there’s a lost public health opportunity, because people with mental illnesses ... who end their life in suicide often are not going to be prohibited people – they can go and legally buy a gun on the day that they use one to end their life. But many of them actually are known to the mental health care system. That’s the opportunity. States could say, ‘let’s use this as a time to separate that individual from guns.’ ”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program in Public Health Law Research, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Elizabeth K. Dollard Charitable Trust.

Enacting risk-based gun removal laws and prohibiting guns from people involuntarily detained in short-term psychiatric hospitalization may have a positive impact on gun-related suicide and violent crime among people with serious mental illnesses.

Those are among the recommendations published June 6 by Jeffrey W. Swanson, Ph.D., and his associates, who studied 81,704 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression in two large Florida counties between 2002 and 2011 (Health Aff. 2016 Jun 6;35[6]:1067-75. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0017).

Dr. Swanson and his associates found that 62% of arrests from gun crimes and 28% of suicides by gun involved individuals who were not legally permitted to have a gun. In addition, they found that suicide was nearly four times as prevalent among adults diagnosed with a serious mental illness, compared with their counterparts in the general population (64.4 vs.17.7 per 100,000 persons).

Also, 20% of suicides among adults with a serious mental illness were by firearm, compared with 48% of adults in the general Florida population, reported Dr. Swanson, a professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Gun violence by suicide claims the lives of 33,000 people each year in the United States, and two-thirds of the country’s gun fatalities are suicides, Dr. Swanson said in a video describing his study.

“We’re focused on laws that restrict access to guns as public health interventions,” Dr. Swanson said. “One of the things that sticks with me is there’s a lost public health opportunity, because people with mental illnesses ... who end their life in suicide often are not going to be prohibited people – they can go and legally buy a gun on the day that they use one to end their life. But many of them actually are known to the mental health care system. That’s the opportunity. States could say, ‘let’s use this as a time to separate that individual from guns.’ ”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program in Public Health Law Research, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Elizabeth K. Dollard Charitable Trust.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Ebola research update: May 2016

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

New evidence exists of the persistence of Ebola virus RNA for up to 9 months in the semen of male survivors in Guinea, according to a research letter from the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The investigators said they cannot yet make conclusions about the infectivity of the semen, but warn that in the absence of evidence on noninfectivity, clinicians should reinforce the importance of safe sex practices among Ebola survivors.

Americans traveling to countries affected by Ebola virus disease (EVD) frequently did not use major health precautions, reported a research letter in Emerging Infectious Diseases, despite federal travel warnings for EVD-affected countries and the consequences of a febrile illness developing. The authors said public health agencies should work closely with communities whose members are likely to visit friends or relatives abroad and with medical providers to increase the use of travel health precautions.

Using histories of household members of Ebola virus disease survivors, researchers in London and Sierra Leone calculated the risk of EVD by age and exposure level, adjusting for confounding and clustering. They found a decidedly lower risk for children aged 5-19 years which, after adjustment for exposure, suggests decreased susceptibility in that age group.

Researchers are adopting an increasingly complex view of antibody-mediated immunity to enveloped viruses like Ebola, according to a commentary in Pathogens and Disease. The authors note that with Ebola and other filoviruses, there are multiple discordances in which neutralizing antibodies fail to protect animals, and others in which antibody-mediated protection is observed in the absence of measured virus neutralization.

Patients recovering from EVD who do not meet the case definition for acute disease pose a low infection risk to health care providers 6 weeks after clearance of viremia, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A study of Ebola virus disease (EVD) survivors in Western Area, Sierra Leone, found that late recrudescence of severe EVD appears to be rare. The investigators discovered no evidence for an effect of infecting dose (as measured by exposure level) on the severity of disease.

A study in the journal Virus Evolution showed that linked genomic and epidemiologic data can not only support contact tracing of EVD cases, but also can identify unconventional transmission chains involving body fluids, including semen. The authors said rapid Ebola virus genome sequencing, when linked to epidemiologic information and a comprehensive database of virus sequences across the 2013 Sierra Leone outbreak, provided a powerful tool for public health epidemic control efforts.

A cluster of health care workers with EVD in Sierra Leone is one of the largest ever reported, according to a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases, and most health care workers with EVD had potential virus exposure both inside and outside of hospitals. The authors said prevention measures for health care workers must address a spectrum of infection risks in both formal and informal care settings as well as in the community.

Previously unanticipated, late, severe relapses of Ebola virus can occur, says a report in The Lancet, and fundamentally redefines what is known about the natural history of Ebola virus infection. The authors said vigilance should be maintained in the thousands of Ebola survivors for cases of relapsed infection.

A report in Emerging Infectious Diseases relates the case of an Ebola virus disease survivor who became pregnant and gave birth to her child in the United States, and the implications of the case for infection control practices in obstetric services.

Four global commissions reviewing the recent EVD epidemic response consistently recommended strengthening national health systems, consolidating and strengthening World Health Organization emergency and outbreak response activities, and enhancing research and development in a PLOS Medicine report.

A recent study in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology claimed that implementation of checklists and scheduled pauses could potentially mitigate 76.5% of all risks to health care providers who are providing care to Ebola virus–infected patients while wearing high-level personal protective equipment.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

New evidence exists of the persistence of Ebola virus RNA for up to 9 months in the semen of male survivors in Guinea, according to a research letter from the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The investigators said they cannot yet make conclusions about the infectivity of the semen, but warn that in the absence of evidence on noninfectivity, clinicians should reinforce the importance of safe sex practices among Ebola survivors.

Americans traveling to countries affected by Ebola virus disease (EVD) frequently did not use major health precautions, reported a research letter in Emerging Infectious Diseases, despite federal travel warnings for EVD-affected countries and the consequences of a febrile illness developing. The authors said public health agencies should work closely with communities whose members are likely to visit friends or relatives abroad and with medical providers to increase the use of travel health precautions.

Using histories of household members of Ebola virus disease survivors, researchers in London and Sierra Leone calculated the risk of EVD by age and exposure level, adjusting for confounding and clustering. They found a decidedly lower risk for children aged 5-19 years which, after adjustment for exposure, suggests decreased susceptibility in that age group.

Researchers are adopting an increasingly complex view of antibody-mediated immunity to enveloped viruses like Ebola, according to a commentary in Pathogens and Disease. The authors note that with Ebola and other filoviruses, there are multiple discordances in which neutralizing antibodies fail to protect animals, and others in which antibody-mediated protection is observed in the absence of measured virus neutralization.

Patients recovering from EVD who do not meet the case definition for acute disease pose a low infection risk to health care providers 6 weeks after clearance of viremia, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A study of Ebola virus disease (EVD) survivors in Western Area, Sierra Leone, found that late recrudescence of severe EVD appears to be rare. The investigators discovered no evidence for an effect of infecting dose (as measured by exposure level) on the severity of disease.

A study in the journal Virus Evolution showed that linked genomic and epidemiologic data can not only support contact tracing of EVD cases, but also can identify unconventional transmission chains involving body fluids, including semen. The authors said rapid Ebola virus genome sequencing, when linked to epidemiologic information and a comprehensive database of virus sequences across the 2013 Sierra Leone outbreak, provided a powerful tool for public health epidemic control efforts.

A cluster of health care workers with EVD in Sierra Leone is one of the largest ever reported, according to a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases, and most health care workers with EVD had potential virus exposure both inside and outside of hospitals. The authors said prevention measures for health care workers must address a spectrum of infection risks in both formal and informal care settings as well as in the community.

Previously unanticipated, late, severe relapses of Ebola virus can occur, says a report in The Lancet, and fundamentally redefines what is known about the natural history of Ebola virus infection. The authors said vigilance should be maintained in the thousands of Ebola survivors for cases of relapsed infection.

A report in Emerging Infectious Diseases relates the case of an Ebola virus disease survivor who became pregnant and gave birth to her child in the United States, and the implications of the case for infection control practices in obstetric services.

Four global commissions reviewing the recent EVD epidemic response consistently recommended strengthening national health systems, consolidating and strengthening World Health Organization emergency and outbreak response activities, and enhancing research and development in a PLOS Medicine report.

A recent study in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology claimed that implementation of checklists and scheduled pauses could potentially mitigate 76.5% of all risks to health care providers who are providing care to Ebola virus–infected patients while wearing high-level personal protective equipment.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

New evidence exists of the persistence of Ebola virus RNA for up to 9 months in the semen of male survivors in Guinea, according to a research letter from the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The investigators said they cannot yet make conclusions about the infectivity of the semen, but warn that in the absence of evidence on noninfectivity, clinicians should reinforce the importance of safe sex practices among Ebola survivors.

Americans traveling to countries affected by Ebola virus disease (EVD) frequently did not use major health precautions, reported a research letter in Emerging Infectious Diseases, despite federal travel warnings for EVD-affected countries and the consequences of a febrile illness developing. The authors said public health agencies should work closely with communities whose members are likely to visit friends or relatives abroad and with medical providers to increase the use of travel health precautions.

Using histories of household members of Ebola virus disease survivors, researchers in London and Sierra Leone calculated the risk of EVD by age and exposure level, adjusting for confounding and clustering. They found a decidedly lower risk for children aged 5-19 years which, after adjustment for exposure, suggests decreased susceptibility in that age group.

Researchers are adopting an increasingly complex view of antibody-mediated immunity to enveloped viruses like Ebola, according to a commentary in Pathogens and Disease. The authors note that with Ebola and other filoviruses, there are multiple discordances in which neutralizing antibodies fail to protect animals, and others in which antibody-mediated protection is observed in the absence of measured virus neutralization.

Patients recovering from EVD who do not meet the case definition for acute disease pose a low infection risk to health care providers 6 weeks after clearance of viremia, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A study of Ebola virus disease (EVD) survivors in Western Area, Sierra Leone, found that late recrudescence of severe EVD appears to be rare. The investigators discovered no evidence for an effect of infecting dose (as measured by exposure level) on the severity of disease.

A study in the journal Virus Evolution showed that linked genomic and epidemiologic data can not only support contact tracing of EVD cases, but also can identify unconventional transmission chains involving body fluids, including semen. The authors said rapid Ebola virus genome sequencing, when linked to epidemiologic information and a comprehensive database of virus sequences across the 2013 Sierra Leone outbreak, provided a powerful tool for public health epidemic control efforts.

A cluster of health care workers with EVD in Sierra Leone is one of the largest ever reported, according to a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases, and most health care workers with EVD had potential virus exposure both inside and outside of hospitals. The authors said prevention measures for health care workers must address a spectrum of infection risks in both formal and informal care settings as well as in the community.

Previously unanticipated, late, severe relapses of Ebola virus can occur, says a report in The Lancet, and fundamentally redefines what is known about the natural history of Ebola virus infection. The authors said vigilance should be maintained in the thousands of Ebola survivors for cases of relapsed infection.

A report in Emerging Infectious Diseases relates the case of an Ebola virus disease survivor who became pregnant and gave birth to her child in the United States, and the implications of the case for infection control practices in obstetric services.

Four global commissions reviewing the recent EVD epidemic response consistently recommended strengthening national health systems, consolidating and strengthening World Health Organization emergency and outbreak response activities, and enhancing research and development in a PLOS Medicine report.

A recent study in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology claimed that implementation of checklists and scheduled pauses could potentially mitigate 76.5% of all risks to health care providers who are providing care to Ebola virus–infected patients while wearing high-level personal protective equipment.

On Twitter @richpizzi

Strangulation of Radial Nerve Within Nondisplaced Fracture Component of Humeral Shaft Fracture

A radial nerve injury in association with a humeral shaft fracture is not an infrequent occurrence.1,2 The nerve injury typically is thought to be a neurapraxia caused by a contusion, as spontaneous recovery rates range from 70% to 90%.2-4 In cases in which acute nerve exploration and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are not indicated, patient and clinician wait months for the nerve to recover. In some conservatively treated cases, the nerve is lacerated or entrapped. Patients with a lacerated or entrapped nerve may have better outcomes with early operative management.

We report on a rare case of the radial nerve entrapped within a nondisplaced segment of a closed humeral shaft fracture and describe the clinical outcome of early operative management. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An intoxicated, restrained 18-year-old driver in a motor vehicle collision sustained multiple injuries, including rib fracture, apical pneumothorax with pulmonary contusion, and corneal abrasion. Orthopedic injuries included right subtrochanteric femur fracture and midshaft right humeral shaft fracture (Figure 1).

Initial orthopedic evaluation of the right arm revealed decreased sensation in the radial nerve distribution. Motor function in the radial nerve was absent; the patient was incapable of active wrist extension or finger extension. Median and ulnar nerves were motor- and sensory-intact. Radiographs showed a displaced transverse midshaft humeral shaft fracture with a minimally displaced vertical fracture line extending from the fracture site about 3 cm into the proximal segment. The patient was placed in a coaptation splint. The femur fracture was treated with an antegrade piriformis entry intramedullary nail.

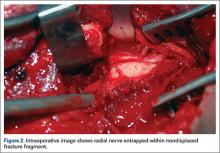

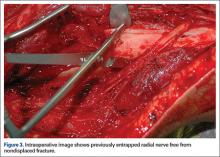

ORIF of the humerus was performed to facilitate mobilization of this polytrauma patient. He was positioned prone on a flat-top table with his right arm over a radiolucent extension. The arm was abducted at the shoulder and the elbow flexed. A posterior midline skin incision was made to reflect the triceps in a lateral-to-medial direction, facilitating dissection of the lateral brachial cutaneous nerve on the lateral aspect of the triceps, with resultant localization of the radial nerve. At that time, the radial nerve was noted to be entrapped in the fracture site (Figure 2). In the proximal segment was a sagittal split, displaced about 1 mm, and it was in this interval the nerve was held. This sagittal fracture appeared incomplete as it was followed more proximally. A unicortical Kirschner wire was placed in a posterior-to-anterior direction in each fragment alongside the nerve. A lamina spreader engaged the wires and distracted the fracture site as the tines were spread apart, releasing the nerve (Figure 3). The nerve was in continuity but was severely contused at that location. After the sagittal split was reduced, two 2.7-mm lag screws were used in lag fashion, and the transverse midshaft component was fixed with a 10-hole, 4.5-mm narrow locking compression plate. The radial nerve lay on the posterior aspect of the plate, between holes 4 and 5 (Figures 4, 5). The wound was closed, and the patient was made weight-bearing as tolerated in the right upper extremity. He was sent to occupational therapy, and static and dynamic splints were made for his wrist and hand.

Two months after injury, radial nerve examination findings were unchanged: decreased sensation on dorsum of hand and no motor function. At 3 months, electrodiagnostic testing showed neurophysiologic evidence of severe right radial neuropathy proximal to the innervation of the right brachioradialis. There were electrodiagnostic signs of ongoing axonal loss and no signs of ongoing reinnervation. At 4 months, only motor strength in wrist extension was improved (2/5). At 5 months, the patient had 4–/5 wrist extension, 3/5 metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension of fingers, and 0/5 MCP/interphalangeal extension of thumb. Sensation in the radial nerve distribution was still decreased. At 7 months, strength in wrist extension and finger MCP extension was 4+/5. The fracture was now well healed, with maintained alignment and no changes in hardware appearance.

Discussion

In most cases, closed treatment of a humeral shaft fracture with an associated radial nerve injury has a successful outcome.5 The etiology of the neurapraxia likely is nerve contusion after the fracture. A neurapraxia is by definition a temporary injury to the myelin sheath with an intact nerve; the nerve function recovers rapidly.

Some humeral shaft fractures, however, have been associated with radial nerve injuries more severe than contusions, resulting in axonotmesis or neurotmesis. These more severe injuries make up 10% to 30% of humeral shaft fractures, including those with a frank laceration of the nerve and those with an entrapped nerve.2,3 Shao and colleagues2 reported a 90% recovery rate for patients who delayed extrication of the entrapped radial nerve. Although there is no consensus on timing of surgical exploration, motor and sensory function of the nerve is temporally related, which may indicate that earlier diagnosis and treatment lead to improved outcome.6,7 Loss of radial nerve function can have devastating effects on upper extremity function. Often, patients lose all or some extension of the wrist and fingers and abduction and extension of the thumb.

In a standard history or physical examination, there are no particular features indicating nerve entrapment. Absolute indications for humeral shaft fractures with radial palsy are limited to open fractures, vascular injuries, and unacceptable fracture alignment. Relative indications are polytrauma and secondary palsy after attempted fracture reduction. For all other humeral shaft fractures with radial nerve palsy, observation is still the mainstay of treatment, with spontaneous recovery occurring in up to 90% of patients.2,8-12 Our patient did not have an absolute indication for operative treatment; surgery was nevertheless performed to address the polytrauma and to facilitate earlier mobilization.

Electromyelogram (EMG) studies typically are not useful after acute injury. EMG studies are better used serially to evaluate reinnervation after the acute phase. Bodner and colleagues13,14 used ultrasonography to identify the radial nerve in a patient with unimproved radial nerve palsy 6 weeks after humeral shaft fracture. They found the nerve within the fracture site, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could not follow its course. Neither ultrasonography nor MRI would likely be used after acute injury. More research is needed to improve evaluation of patients with continued palsy after nonoperative treatment.

In the case of our patient’s humeral shaft fracture, surgery was performed early because of polytrauma and radial nerve entrapment. If left interposed between 2 fracture fragments, the nerve would have been subjected to continued ischemia and likely would not have recovered spontaneously. Ikeda and Osamura7 reported on a case of radial nerve palsy that occurred after humerus shaft fracture. The nerve, entrapped between fracture fragments, was explored later, after function failed to return. As it was found within callus, the nerve was cut and then repaired end-to-end. In our patient’s case, early exploration led to release of the radial nerve from the fracture site—preventing irreversible nerve damage and allowing for spontaneous recovery over subsequent months.

Surgery for polytrauma patients with a humeral shaft fracture and radial nerve palsy may also be beneficial with respect to early nerve exploration and early mobilization. Although our patient’s fracture was well aligned and as an isolated injury would not have required surgery, the polytrauma called for early surgical management, which revealed radial nerve entrapment and led to early recovery of nerve function.

1. Ekholm R, Adami J, Tidermark J, Hansson K, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S. Fractures of the shaft of the humerus. An epidemiological study of 401 fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(11):1469-1473.

2. Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, Limb D, Giannoudis PV. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1647-1652.

3. Shah JJ, Bhatti NA. Radial nerve paralysis associated with fractures of the humerus. A review of 62 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(172):171-176.

4. Ring D, Chin K, Jupiter JB. Radial nerve palsy associated with high-energy humeral shaft fractures. J Hand Surg. 2004;29(1):144-147.

5. Sarmiento A, Zagorski JB, Zych GA, Latta LL, Capps CA. Functional bracing for the treatment of fractures of the humeral diaphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):478-486.

6. Hugon S, Daubresse F, Depierreux L. Radial nerve entrapment in a humeral fracture callus. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(1):118-121.

7. Ikeda K, Osamura N. The radial nerve palsy caused by embedding in the humeral shaft fracture—a case report. Hand Surg. 2014;19(1):91-93.

8. Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Wolfe SW, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 2 vols. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

9. Kettelkamp DB, Alexander H. Clinical review of radial nerve injury. J Trauma. 1967;7(3):424-432.

10. Pollock FH, Drake D, Bovill EG, Day L, Trafton PG. Treatment of radial neuropathy associated with fractures of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(2):239-243.

11. Li Y, Ning G, Wu Q, Wu Q, Li Y, Feng S. Review of literature of radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures—an integrated management strategy. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78576.

12. DeFranco MJ, Lawton JN. Radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures. J Hand Surg. 2006;31(4):655-663.

13. Bodner G, Huber B, Schwabegger A, Lutz M, Waldenberger P. Sonographic detection of radial nerve entrapment within a humerus fracture. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18(10):703-706.

14. Bodner G, Buchberger W, Schocke M, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fracture: evaluation with US—initial experience. Radiology. 2001;219(3):811-816.

A radial nerve injury in association with a humeral shaft fracture is not an infrequent occurrence.1,2 The nerve injury typically is thought to be a neurapraxia caused by a contusion, as spontaneous recovery rates range from 70% to 90%.2-4 In cases in which acute nerve exploration and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are not indicated, patient and clinician wait months for the nerve to recover. In some conservatively treated cases, the nerve is lacerated or entrapped. Patients with a lacerated or entrapped nerve may have better outcomes with early operative management.

We report on a rare case of the radial nerve entrapped within a nondisplaced segment of a closed humeral shaft fracture and describe the clinical outcome of early operative management. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An intoxicated, restrained 18-year-old driver in a motor vehicle collision sustained multiple injuries, including rib fracture, apical pneumothorax with pulmonary contusion, and corneal abrasion. Orthopedic injuries included right subtrochanteric femur fracture and midshaft right humeral shaft fracture (Figure 1).

Initial orthopedic evaluation of the right arm revealed decreased sensation in the radial nerve distribution. Motor function in the radial nerve was absent; the patient was incapable of active wrist extension or finger extension. Median and ulnar nerves were motor- and sensory-intact. Radiographs showed a displaced transverse midshaft humeral shaft fracture with a minimally displaced vertical fracture line extending from the fracture site about 3 cm into the proximal segment. The patient was placed in a coaptation splint. The femur fracture was treated with an antegrade piriformis entry intramedullary nail.

ORIF of the humerus was performed to facilitate mobilization of this polytrauma patient. He was positioned prone on a flat-top table with his right arm over a radiolucent extension. The arm was abducted at the shoulder and the elbow flexed. A posterior midline skin incision was made to reflect the triceps in a lateral-to-medial direction, facilitating dissection of the lateral brachial cutaneous nerve on the lateral aspect of the triceps, with resultant localization of the radial nerve. At that time, the radial nerve was noted to be entrapped in the fracture site (Figure 2). In the proximal segment was a sagittal split, displaced about 1 mm, and it was in this interval the nerve was held. This sagittal fracture appeared incomplete as it was followed more proximally. A unicortical Kirschner wire was placed in a posterior-to-anterior direction in each fragment alongside the nerve. A lamina spreader engaged the wires and distracted the fracture site as the tines were spread apart, releasing the nerve (Figure 3). The nerve was in continuity but was severely contused at that location. After the sagittal split was reduced, two 2.7-mm lag screws were used in lag fashion, and the transverse midshaft component was fixed with a 10-hole, 4.5-mm narrow locking compression plate. The radial nerve lay on the posterior aspect of the plate, between holes 4 and 5 (Figures 4, 5). The wound was closed, and the patient was made weight-bearing as tolerated in the right upper extremity. He was sent to occupational therapy, and static and dynamic splints were made for his wrist and hand.

Two months after injury, radial nerve examination findings were unchanged: decreased sensation on dorsum of hand and no motor function. At 3 months, electrodiagnostic testing showed neurophysiologic evidence of severe right radial neuropathy proximal to the innervation of the right brachioradialis. There were electrodiagnostic signs of ongoing axonal loss and no signs of ongoing reinnervation. At 4 months, only motor strength in wrist extension was improved (2/5). At 5 months, the patient had 4–/5 wrist extension, 3/5 metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension of fingers, and 0/5 MCP/interphalangeal extension of thumb. Sensation in the radial nerve distribution was still decreased. At 7 months, strength in wrist extension and finger MCP extension was 4+/5. The fracture was now well healed, with maintained alignment and no changes in hardware appearance.

Discussion

In most cases, closed treatment of a humeral shaft fracture with an associated radial nerve injury has a successful outcome.5 The etiology of the neurapraxia likely is nerve contusion after the fracture. A neurapraxia is by definition a temporary injury to the myelin sheath with an intact nerve; the nerve function recovers rapidly.

Some humeral shaft fractures, however, have been associated with radial nerve injuries more severe than contusions, resulting in axonotmesis or neurotmesis. These more severe injuries make up 10% to 30% of humeral shaft fractures, including those with a frank laceration of the nerve and those with an entrapped nerve.2,3 Shao and colleagues2 reported a 90% recovery rate for patients who delayed extrication of the entrapped radial nerve. Although there is no consensus on timing of surgical exploration, motor and sensory function of the nerve is temporally related, which may indicate that earlier diagnosis and treatment lead to improved outcome.6,7 Loss of radial nerve function can have devastating effects on upper extremity function. Often, patients lose all or some extension of the wrist and fingers and abduction and extension of the thumb.

In a standard history or physical examination, there are no particular features indicating nerve entrapment. Absolute indications for humeral shaft fractures with radial palsy are limited to open fractures, vascular injuries, and unacceptable fracture alignment. Relative indications are polytrauma and secondary palsy after attempted fracture reduction. For all other humeral shaft fractures with radial nerve palsy, observation is still the mainstay of treatment, with spontaneous recovery occurring in up to 90% of patients.2,8-12 Our patient did not have an absolute indication for operative treatment; surgery was nevertheless performed to address the polytrauma and to facilitate earlier mobilization.

Electromyelogram (EMG) studies typically are not useful after acute injury. EMG studies are better used serially to evaluate reinnervation after the acute phase. Bodner and colleagues13,14 used ultrasonography to identify the radial nerve in a patient with unimproved radial nerve palsy 6 weeks after humeral shaft fracture. They found the nerve within the fracture site, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could not follow its course. Neither ultrasonography nor MRI would likely be used after acute injury. More research is needed to improve evaluation of patients with continued palsy after nonoperative treatment.

In the case of our patient’s humeral shaft fracture, surgery was performed early because of polytrauma and radial nerve entrapment. If left interposed between 2 fracture fragments, the nerve would have been subjected to continued ischemia and likely would not have recovered spontaneously. Ikeda and Osamura7 reported on a case of radial nerve palsy that occurred after humerus shaft fracture. The nerve, entrapped between fracture fragments, was explored later, after function failed to return. As it was found within callus, the nerve was cut and then repaired end-to-end. In our patient’s case, early exploration led to release of the radial nerve from the fracture site—preventing irreversible nerve damage and allowing for spontaneous recovery over subsequent months.

Surgery for polytrauma patients with a humeral shaft fracture and radial nerve palsy may also be beneficial with respect to early nerve exploration and early mobilization. Although our patient’s fracture was well aligned and as an isolated injury would not have required surgery, the polytrauma called for early surgical management, which revealed radial nerve entrapment and led to early recovery of nerve function.

A radial nerve injury in association with a humeral shaft fracture is not an infrequent occurrence.1,2 The nerve injury typically is thought to be a neurapraxia caused by a contusion, as spontaneous recovery rates range from 70% to 90%.2-4 In cases in which acute nerve exploration and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are not indicated, patient and clinician wait months for the nerve to recover. In some conservatively treated cases, the nerve is lacerated or entrapped. Patients with a lacerated or entrapped nerve may have better outcomes with early operative management.

We report on a rare case of the radial nerve entrapped within a nondisplaced segment of a closed humeral shaft fracture and describe the clinical outcome of early operative management. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An intoxicated, restrained 18-year-old driver in a motor vehicle collision sustained multiple injuries, including rib fracture, apical pneumothorax with pulmonary contusion, and corneal abrasion. Orthopedic injuries included right subtrochanteric femur fracture and midshaft right humeral shaft fracture (Figure 1).

Initial orthopedic evaluation of the right arm revealed decreased sensation in the radial nerve distribution. Motor function in the radial nerve was absent; the patient was incapable of active wrist extension or finger extension. Median and ulnar nerves were motor- and sensory-intact. Radiographs showed a displaced transverse midshaft humeral shaft fracture with a minimally displaced vertical fracture line extending from the fracture site about 3 cm into the proximal segment. The patient was placed in a coaptation splint. The femur fracture was treated with an antegrade piriformis entry intramedullary nail.

ORIF of the humerus was performed to facilitate mobilization of this polytrauma patient. He was positioned prone on a flat-top table with his right arm over a radiolucent extension. The arm was abducted at the shoulder and the elbow flexed. A posterior midline skin incision was made to reflect the triceps in a lateral-to-medial direction, facilitating dissection of the lateral brachial cutaneous nerve on the lateral aspect of the triceps, with resultant localization of the radial nerve. At that time, the radial nerve was noted to be entrapped in the fracture site (Figure 2). In the proximal segment was a sagittal split, displaced about 1 mm, and it was in this interval the nerve was held. This sagittal fracture appeared incomplete as it was followed more proximally. A unicortical Kirschner wire was placed in a posterior-to-anterior direction in each fragment alongside the nerve. A lamina spreader engaged the wires and distracted the fracture site as the tines were spread apart, releasing the nerve (Figure 3). The nerve was in continuity but was severely contused at that location. After the sagittal split was reduced, two 2.7-mm lag screws were used in lag fashion, and the transverse midshaft component was fixed with a 10-hole, 4.5-mm narrow locking compression plate. The radial nerve lay on the posterior aspect of the plate, between holes 4 and 5 (Figures 4, 5). The wound was closed, and the patient was made weight-bearing as tolerated in the right upper extremity. He was sent to occupational therapy, and static and dynamic splints were made for his wrist and hand.

Two months after injury, radial nerve examination findings were unchanged: decreased sensation on dorsum of hand and no motor function. At 3 months, electrodiagnostic testing showed neurophysiologic evidence of severe right radial neuropathy proximal to the innervation of the right brachioradialis. There were electrodiagnostic signs of ongoing axonal loss and no signs of ongoing reinnervation. At 4 months, only motor strength in wrist extension was improved (2/5). At 5 months, the patient had 4–/5 wrist extension, 3/5 metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension of fingers, and 0/5 MCP/interphalangeal extension of thumb. Sensation in the radial nerve distribution was still decreased. At 7 months, strength in wrist extension and finger MCP extension was 4+/5. The fracture was now well healed, with maintained alignment and no changes in hardware appearance.

Discussion

In most cases, closed treatment of a humeral shaft fracture with an associated radial nerve injury has a successful outcome.5 The etiology of the neurapraxia likely is nerve contusion after the fracture. A neurapraxia is by definition a temporary injury to the myelin sheath with an intact nerve; the nerve function recovers rapidly.

Some humeral shaft fractures, however, have been associated with radial nerve injuries more severe than contusions, resulting in axonotmesis or neurotmesis. These more severe injuries make up 10% to 30% of humeral shaft fractures, including those with a frank laceration of the nerve and those with an entrapped nerve.2,3 Shao and colleagues2 reported a 90% recovery rate for patients who delayed extrication of the entrapped radial nerve. Although there is no consensus on timing of surgical exploration, motor and sensory function of the nerve is temporally related, which may indicate that earlier diagnosis and treatment lead to improved outcome.6,7 Loss of radial nerve function can have devastating effects on upper extremity function. Often, patients lose all or some extension of the wrist and fingers and abduction and extension of the thumb.

In a standard history or physical examination, there are no particular features indicating nerve entrapment. Absolute indications for humeral shaft fractures with radial palsy are limited to open fractures, vascular injuries, and unacceptable fracture alignment. Relative indications are polytrauma and secondary palsy after attempted fracture reduction. For all other humeral shaft fractures with radial nerve palsy, observation is still the mainstay of treatment, with spontaneous recovery occurring in up to 90% of patients.2,8-12 Our patient did not have an absolute indication for operative treatment; surgery was nevertheless performed to address the polytrauma and to facilitate earlier mobilization.

Electromyelogram (EMG) studies typically are not useful after acute injury. EMG studies are better used serially to evaluate reinnervation after the acute phase. Bodner and colleagues13,14 used ultrasonography to identify the radial nerve in a patient with unimproved radial nerve palsy 6 weeks after humeral shaft fracture. They found the nerve within the fracture site, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could not follow its course. Neither ultrasonography nor MRI would likely be used after acute injury. More research is needed to improve evaluation of patients with continued palsy after nonoperative treatment.

In the case of our patient’s humeral shaft fracture, surgery was performed early because of polytrauma and radial nerve entrapment. If left interposed between 2 fracture fragments, the nerve would have been subjected to continued ischemia and likely would not have recovered spontaneously. Ikeda and Osamura7 reported on a case of radial nerve palsy that occurred after humerus shaft fracture. The nerve, entrapped between fracture fragments, was explored later, after function failed to return. As it was found within callus, the nerve was cut and then repaired end-to-end. In our patient’s case, early exploration led to release of the radial nerve from the fracture site—preventing irreversible nerve damage and allowing for spontaneous recovery over subsequent months.

Surgery for polytrauma patients with a humeral shaft fracture and radial nerve palsy may also be beneficial with respect to early nerve exploration and early mobilization. Although our patient’s fracture was well aligned and as an isolated injury would not have required surgery, the polytrauma called for early surgical management, which revealed radial nerve entrapment and led to early recovery of nerve function.

1. Ekholm R, Adami J, Tidermark J, Hansson K, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S. Fractures of the shaft of the humerus. An epidemiological study of 401 fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(11):1469-1473.

2. Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, Limb D, Giannoudis PV. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1647-1652.

3. Shah JJ, Bhatti NA. Radial nerve paralysis associated with fractures of the humerus. A review of 62 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(172):171-176.

4. Ring D, Chin K, Jupiter JB. Radial nerve palsy associated with high-energy humeral shaft fractures. J Hand Surg. 2004;29(1):144-147.

5. Sarmiento A, Zagorski JB, Zych GA, Latta LL, Capps CA. Functional bracing for the treatment of fractures of the humeral diaphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):478-486.

6. Hugon S, Daubresse F, Depierreux L. Radial nerve entrapment in a humeral fracture callus. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(1):118-121.

7. Ikeda K, Osamura N. The radial nerve palsy caused by embedding in the humeral shaft fracture—a case report. Hand Surg. 2014;19(1):91-93.

8. Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Wolfe SW, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 2 vols. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

9. Kettelkamp DB, Alexander H. Clinical review of radial nerve injury. J Trauma. 1967;7(3):424-432.

10. Pollock FH, Drake D, Bovill EG, Day L, Trafton PG. Treatment of radial neuropathy associated with fractures of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(2):239-243.

11. Li Y, Ning G, Wu Q, Wu Q, Li Y, Feng S. Review of literature of radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures—an integrated management strategy. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78576.

12. DeFranco MJ, Lawton JN. Radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures. J Hand Surg. 2006;31(4):655-663.

13. Bodner G, Huber B, Schwabegger A, Lutz M, Waldenberger P. Sonographic detection of radial nerve entrapment within a humerus fracture. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18(10):703-706.

14. Bodner G, Buchberger W, Schocke M, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fracture: evaluation with US—initial experience. Radiology. 2001;219(3):811-816.

1. Ekholm R, Adami J, Tidermark J, Hansson K, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S. Fractures of the shaft of the humerus. An epidemiological study of 401 fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(11):1469-1473.

2. Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, Limb D, Giannoudis PV. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1647-1652.

3. Shah JJ, Bhatti NA. Radial nerve paralysis associated with fractures of the humerus. A review of 62 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(172):171-176.

4. Ring D, Chin K, Jupiter JB. Radial nerve palsy associated with high-energy humeral shaft fractures. J Hand Surg. 2004;29(1):144-147.

5. Sarmiento A, Zagorski JB, Zych GA, Latta LL, Capps CA. Functional bracing for the treatment of fractures of the humeral diaphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):478-486.

6. Hugon S, Daubresse F, Depierreux L. Radial nerve entrapment in a humeral fracture callus. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(1):118-121.

7. Ikeda K, Osamura N. The radial nerve palsy caused by embedding in the humeral shaft fracture—a case report. Hand Surg. 2014;19(1):91-93.

8. Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Wolfe SW, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 2 vols. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

9. Kettelkamp DB, Alexander H. Clinical review of radial nerve injury. J Trauma. 1967;7(3):424-432.

10. Pollock FH, Drake D, Bovill EG, Day L, Trafton PG. Treatment of radial neuropathy associated with fractures of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(2):239-243.

11. Li Y, Ning G, Wu Q, Wu Q, Li Y, Feng S. Review of literature of radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures—an integrated management strategy. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e78576.

12. DeFranco MJ, Lawton JN. Radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures. J Hand Surg. 2006;31(4):655-663.

13. Bodner G, Huber B, Schwabegger A, Lutz M, Waldenberger P. Sonographic detection of radial nerve entrapment within a humerus fracture. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18(10):703-706.

14. Bodner G, Buchberger W, Schocke M, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fracture: evaluation with US—initial experience. Radiology. 2001;219(3):811-816.

QUIZ: What Is Next Step for Diagnosing Cavitary Lesion with No Improvement after Serial Chest X-Rays, Antibiotics?

[WpProQuiz 9]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 9]

[WpProQuiz 9]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 9]

[WpProQuiz 9]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 9]

Brentuximab vedotin boosted PET-negative rate in Hodgkin

CHICAGO – Brentuximab vedotin appears to be safe and effective in eradicating residual disease after induction chemotherapy and may replace radiation for consolidation in patients with limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Steven I. Park reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

After two cycles of ABVD [doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine], 72% of 40 evaluable patients achieved PET-negative disease. After completing brentuximab vedotin therapy, 90% of patients had PET-negative disease. With a median follow-up of 12 months, the estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate is 91%, and the overall survival rate is 96%.

The current standard therapy for limited stage Hodgkin lymphoma is about 4-6 cycles of chemotherapy with or without consolidative radiation therapy. The goal of the study was to reduce the number of cycles of chemotherapy and avoid radiation therapy, which has an unclear overall survival advantage and risks long-term side effects, noted Dr. Park of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In this phase II multicenter study, 41 patients with previously untreated limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma received ABVD followed by brentuximab vedotin (NCT01578967). Study patients’ median age was 29 years (range 19-67), and 46% presented with unfavorable disease. Over 90% of patients received four or fewer cycles of ABVD, and one patient received radiation due to disease progression.

Grade 3 or higher toxicities associated with brentuximab vedotin included neutropenia in three patients and peripheral neuropathy and rash in one patient each. One patient developed pancreatitis and died due to sepsis and hepatic failure, a rare complication of brentuximab vedotin that cautions regarding its use in patients with hepatic function limitations, Dr. Park said.

According to Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, the drug is an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E, which leads to target cell death when internalized into CD30-expressing tumor cells.

Dr. Park disclosed research funding from Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, as well as Teva.

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Brentuximab vedotin appears to be safe and effective in eradicating residual disease after induction chemotherapy and may replace radiation for consolidation in patients with limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Steven I. Park reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

After two cycles of ABVD [doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine], 72% of 40 evaluable patients achieved PET-negative disease. After completing brentuximab vedotin therapy, 90% of patients had PET-negative disease. With a median follow-up of 12 months, the estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate is 91%, and the overall survival rate is 96%.

The current standard therapy for limited stage Hodgkin lymphoma is about 4-6 cycles of chemotherapy with or without consolidative radiation therapy. The goal of the study was to reduce the number of cycles of chemotherapy and avoid radiation therapy, which has an unclear overall survival advantage and risks long-term side effects, noted Dr. Park of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In this phase II multicenter study, 41 patients with previously untreated limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma received ABVD followed by brentuximab vedotin (NCT01578967). Study patients’ median age was 29 years (range 19-67), and 46% presented with unfavorable disease. Over 90% of patients received four or fewer cycles of ABVD, and one patient received radiation due to disease progression.

Grade 3 or higher toxicities associated with brentuximab vedotin included neutropenia in three patients and peripheral neuropathy and rash in one patient each. One patient developed pancreatitis and died due to sepsis and hepatic failure, a rare complication of brentuximab vedotin that cautions regarding its use in patients with hepatic function limitations, Dr. Park said.

According to Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, the drug is an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E, which leads to target cell death when internalized into CD30-expressing tumor cells.

Dr. Park disclosed research funding from Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, as well as Teva.

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Brentuximab vedotin appears to be safe and effective in eradicating residual disease after induction chemotherapy and may replace radiation for consolidation in patients with limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma, Dr. Steven I. Park reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

After two cycles of ABVD [doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine], 72% of 40 evaluable patients achieved PET-negative disease. After completing brentuximab vedotin therapy, 90% of patients had PET-negative disease. With a median follow-up of 12 months, the estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate is 91%, and the overall survival rate is 96%.

The current standard therapy for limited stage Hodgkin lymphoma is about 4-6 cycles of chemotherapy with or without consolidative radiation therapy. The goal of the study was to reduce the number of cycles of chemotherapy and avoid radiation therapy, which has an unclear overall survival advantage and risks long-term side effects, noted Dr. Park of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In this phase II multicenter study, 41 patients with previously untreated limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma received ABVD followed by brentuximab vedotin (NCT01578967). Study patients’ median age was 29 years (range 19-67), and 46% presented with unfavorable disease. Over 90% of patients received four or fewer cycles of ABVD, and one patient received radiation due to disease progression.

Grade 3 or higher toxicities associated with brentuximab vedotin included neutropenia in three patients and peripheral neuropathy and rash in one patient each. One patient developed pancreatitis and died due to sepsis and hepatic failure, a rare complication of brentuximab vedotin that cautions regarding its use in patients with hepatic function limitations, Dr. Park said.

According to Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, the drug is an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E, which leads to target cell death when internalized into CD30-expressing tumor cells.

Dr. Park disclosed research funding from Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, as well as Teva.

On Twitter @maryjodales

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Brentuximab vedotin appears to eradicate residual disease after induction chemotherapy in a small study of patients with limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma.

Major finding: In 40 evaluable patients, 72% were PET-negative after two cycles of ABVD; brentuximab vedotin consolidation boosted PET-negative status to 90% of patients.

Data source: A phase II multicenter study of 41 patients with previously untreated limited stage non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma.

Disclosures: Dr. Park disclosed research funding from Seattle Genetics, the maker of brentuximab vedotin, as well as Teva.

VIDEO: CPX-351 ‘new standard of care’ for older patients with secondary AML

CHICAGO – The investigational drug CPX-351 (Vyxeos) may become the new standard of care for older patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML), based on data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

CPX-351 significantly improved overall survival, event-free survival, and treatment response without an increase in 60-day mortality or in the frequency and severity of adverse events as compared to the standard 7+3 regimen of cytarabine and daunorubicin.

In a video interview, primary investigator Dr. Jeffrey Lancet of H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Fla., discusses the data to be presented to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of the drug, and why the liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin achieved superior results in these difficult to treat patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – The investigational drug CPX-351 (Vyxeos) may become the new standard of care for older patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML), based on data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

CPX-351 significantly improved overall survival, event-free survival, and treatment response without an increase in 60-day mortality or in the frequency and severity of adverse events as compared to the standard 7+3 regimen of cytarabine and daunorubicin.

In a video interview, primary investigator Dr. Jeffrey Lancet of H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Fla., discusses the data to be presented to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of the drug, and why the liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin achieved superior results in these difficult to treat patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – The investigational drug CPX-351 (Vyxeos) may become the new standard of care for older patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML), based on data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

CPX-351 significantly improved overall survival, event-free survival, and treatment response without an increase in 60-day mortality or in the frequency and severity of adverse events as compared to the standard 7+3 regimen of cytarabine and daunorubicin.

In a video interview, primary investigator Dr. Jeffrey Lancet of H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Fla., discusses the data to be presented to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of the drug, and why the liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin achieved superior results in these difficult to treat patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @maryjodales

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Body Scrubs

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on body scrubs. Consideration must be given to:

- Almond Shower Scrub

- Gently Exfoliating Body Scrub

- Peppermint Body Scrub

- Shea Butter Ultra Rich Body Scrub

- Ultimate Man Body Scrub Soap

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body scrubs, OTC acne treatments, and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on body scrubs. Consideration must be given to:

- Almond Shower Scrub

- Gently Exfoliating Body Scrub

- Peppermint Body Scrub

- Shea Butter Ultra Rich Body Scrub

- Ultimate Man Body Scrub Soap

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body scrubs, OTC acne treatments, and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on body scrubs. Consideration must be given to:

- Almond Shower Scrub

- Gently Exfoliating Body Scrub

- Peppermint Body Scrub

- Shea Butter Ultra Rich Body Scrub

- Ultimate Man Body Scrub Soap

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body scrubs, OTC acne treatments, and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Experience VAM Electronically: Mobile App and Planner

Two tools – the Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App and the Meeting Itinerary Planner – will make VAM 2016 a user-friendly experience.

The App

The SVS Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App puts the entire meeting at attendees’ fingertips. It includes:

• All meeting content, including abstracts, speakers, sessions and more

• A searchable format, letting people locate sessions, abstracts, room locations and more

• Interactivity: People may network with colleagues, share photos and rate programs, take notes and use the activity feed available for each session.

New this year is a link that lets participants access the CME and MOC sites, to take credit exams after a session ends. It also includes links to claim credits.

The Itinerary Planner

The Itinerary Planner is a web-based tool that includes all VAM details, such as full and daily schedules; links to authors, abstracts and speaker bios; special events; programming for fellows/residents/students; registration information, Vascular Live details and all other VAM info.

The detailed Users will be able to build personal schedules with their own “must-attend” events and sessions by bookmarking items of interest, plus:

• View session, faculty and exhibitor information in real time.

• Search for presentations by day, type, individual or keyword.

• Add in personal meetings or events.

• Export and email their calendar to share with others.

• Access the site via mobile and traditional platforms.

Please note that schedules and agendas created on the Itinerary Planner do NOT sync with the schedule in the Mobile App.

Two tools – the Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App and the Meeting Itinerary Planner – will make VAM 2016 a user-friendly experience.

The App

The SVS Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App puts the entire meeting at attendees’ fingertips. It includes:

• All meeting content, including abstracts, speakers, sessions and more

• A searchable format, letting people locate sessions, abstracts, room locations and more

• Interactivity: People may network with colleagues, share photos and rate programs, take notes and use the activity feed available for each session.

New this year is a link that lets participants access the CME and MOC sites, to take credit exams after a session ends. It also includes links to claim credits.

The Itinerary Planner

The Itinerary Planner is a web-based tool that includes all VAM details, such as full and daily schedules; links to authors, abstracts and speaker bios; special events; programming for fellows/residents/students; registration information, Vascular Live details and all other VAM info.

The detailed Users will be able to build personal schedules with their own “must-attend” events and sessions by bookmarking items of interest, plus:

• View session, faculty and exhibitor information in real time.

• Search for presentations by day, type, individual or keyword.

• Add in personal meetings or events.

• Export and email their calendar to share with others.

• Access the site via mobile and traditional platforms.

Please note that schedules and agendas created on the Itinerary Planner do NOT sync with the schedule in the Mobile App.

Two tools – the Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App and the Meeting Itinerary Planner – will make VAM 2016 a user-friendly experience.

The App

The SVS Vascular Annual Meeting Mobile App puts the entire meeting at attendees’ fingertips. It includes:

• All meeting content, including abstracts, speakers, sessions and more

• A searchable format, letting people locate sessions, abstracts, room locations and more

• Interactivity: People may network with colleagues, share photos and rate programs, take notes and use the activity feed available for each session.

New this year is a link that lets participants access the CME and MOC sites, to take credit exams after a session ends. It also includes links to claim credits.

The Itinerary Planner

The Itinerary Planner is a web-based tool that includes all VAM details, such as full and daily schedules; links to authors, abstracts and speaker bios; special events; programming for fellows/residents/students; registration information, Vascular Live details and all other VAM info.

The detailed Users will be able to build personal schedules with their own “must-attend” events and sessions by bookmarking items of interest, plus:

• View session, faculty and exhibitor information in real time.

• Search for presentations by day, type, individual or keyword.

• Add in personal meetings or events.

• Export and email their calendar to share with others.

• Access the site via mobile and traditional platforms.

Please note that schedules and agendas created on the Itinerary Planner do NOT sync with the schedule in the Mobile App.

The 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting – Come early, stay late for invigorating sessions and a dash of fun

Exhibits, speakers, plenaries, hands-on sessions. Networking, dinner with friends, alumni receptions, the Capitol Steps comedy act. All this and much more is on tap during the 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting slated for June 8-11, just outside Washington, D.C. Plenaries and exhibits begin June 9. Registration is open throughout the conference.

Vascular surgeons, specialists, medical professionals in related fields, device manufacturers and others will meet at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland, just minutes away from Washington, D.C.

Thanks to popular demand, each year the annual meeting -- often called VAM -- expands a little more on Wednesday and Saturday to accommodate more events and opportunities. This year Wednesday and Saturday are filled with events and sessions that attendees won’t want to miss. Workshops ($100 fee), international events and a full day of Vascular Quality Initiative sessions will be on Wednesday. Thursday and Friday feature more plenaries, talks by vascular luminaries, receptions, breakfast and evening events. On Saturday the annual SVS business meeting, the exhibit hall and credit-worthy plenaries will be good reasons to stay through the end.

A highlight this year will be a Friday June 10 evening performance by the Capitol Steps, a comedy troupe based in D.C. known for their cutting edge, political humor. It will be open to all attendees, exhibitors and their guests.

2016 VAM offers a variety of postgraduate courses on Wednesday designed for surgeons, physicians in related specialties, trainees, interventional radiologists, physician assistants and vascular nurses, researchers, allied health professionals and medical students. Postgraduate courses are complimentary for SVS members but separate registration is required.

This year’s events offer a maximum of 30.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ with 13.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ counted toward MOC part 2. Each of the seven plenary sessions has individual self-assessments. This year, claiming your credits is easier than ever. A self-assessment exam is available on the meeting app and can be completed immediately following each session.

Registration is open through the end of the event, and may be completed online at www.vsweb.org/RegisterVAM16. There are 10 different registration fees that vary by category. For example, active members pay $650; medical students, $300; non-members $845. In addition, there are still some seats left in the hands-on workshops offered on Wednesday, June 8. Topics include Carotid Stenting, IVC Filters: Techniques in Deployment and Recovery and much more. See all topics.

The conference location, Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, offers sweeping views of the Potomac River, Washington, D.C. and Old Town Alexandria. As the cornerstone of the new National Harbor project in Prince George’s County, Maryland, the resort includes an 18-story glass atrium overlooking the Potomac, three restaurants, including fine dining and casual, a rooftop lounge, express coffee outlet, unique shops, an indoor pool and a 20,000 square-foot spa and fitness center. The 300-acre site also features tree-lined promenades with shops and restaurants, two marinas, a Ferris wheel and much more. For a complete directory as well as an interactive map, please visit the Gaylord National Resort & Conference Center website.

The weather in Washington D.C. in early June averages a high of 83 and low of 65, Fahrenheit. Attire is business casual during the day and resort casual for hospitality events.

Exhibits, speakers, plenaries, hands-on sessions. Networking, dinner with friends, alumni receptions, the Capitol Steps comedy act. All this and much more is on tap during the 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting slated for June 8-11, just outside Washington, D.C. Plenaries and exhibits begin June 9. Registration is open throughout the conference.

Vascular surgeons, specialists, medical professionals in related fields, device manufacturers and others will meet at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland, just minutes away from Washington, D.C.

Thanks to popular demand, each year the annual meeting -- often called VAM -- expands a little more on Wednesday and Saturday to accommodate more events and opportunities. This year Wednesday and Saturday are filled with events and sessions that attendees won’t want to miss. Workshops ($100 fee), international events and a full day of Vascular Quality Initiative sessions will be on Wednesday. Thursday and Friday feature more plenaries, talks by vascular luminaries, receptions, breakfast and evening events. On Saturday the annual SVS business meeting, the exhibit hall and credit-worthy plenaries will be good reasons to stay through the end.

A highlight this year will be a Friday June 10 evening performance by the Capitol Steps, a comedy troupe based in D.C. known for their cutting edge, political humor. It will be open to all attendees, exhibitors and their guests.