User login

First EDition: News for and about the practice of emergency medicine

Medication for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: For Which Patients Is It Effective?

BY JEFF BAUER

FROM N ENGL J MED

A recent double-blind, randomized trial that compared parenteral amiodarone, lidocaine, and saline placebo for patients who experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that overall, neither medication resulted in a significantly higher survival rate nor better neurological outcomes.1 However, among a subgroup of patients whose cardiac arrest was witnessed by a bystander, the rate of survival to hospital discharge was significantly higher with amiodarone or lidocaine than with placebo.

Researchers studied 3,026 adults who had nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and shock-refractory ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. These patients were treated in accordance with local emergency medical service (EMS) protocols that complied with American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for advanced life support. After one or more shocks failed to end ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, patients were randomly treated with one of three parenteral preparations: lidocaine (993 patients), a recently approved cyclodextrin-based formulation of amiodarone that is designed to reduce hypotensive effects (974 patients), or a normal saline placebo (1,059 patients). The initial treatment consisted of two syringes that were administered by rapid bolus. If the ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia persisted after this initial dose, a supplemental dose (one syringe) of the same drug was administered. The average time to treatment with these drugs was 19 minutes from the initial call to EMS. On arrival at the hospital, patients were treated with usual postcardiac arrest care in accordance with AHA guidelines.

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. The secondary outcome was survival with favorable neurological status at discharge, which was defined as a score of ≤3 on the modified Rankin scale, indicating the ability to conduct daily activities independently or with minimal assistance.

The hospital survival rates were 23.7% for patients who received lidocaine, 24.4% for those who received amiodarone, and 21.0% for those who received placebo. The differences in survival rates for each drug compared to placebo, and one drug compared to the other drug, were not statistically significant. Rates of survival with favorable neurological status were similar among all three groups.

However, among 1,934 patients who experienced a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, each drug was associated with a significantly higher rate of survival (5 percentage points) compared to placebo. In these patients, the survival rate was 27.8% with lidocaine, 27.7% with amiodarone, and 22.7% with placebo. This absolute risk difference was significant for lidocaine versus placebo and for amiodarone versus placebo, but not for lidocaine versus amiodarone.

Researchers said patients who have a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest presumably have “early recognition of cardiac arrest, a short interval between the patient’s collapse from cardiac arrest and the initiation of treatment, and a greater likelihood of therapeutic responsiveness.” In an accompanying editorial, Joglar and Page2 said EMS personnel should consider using lidocaine or amiodarone when a patient’s cardiac arrest is witnessed.

1. Kudenchuk PJ, Brown SP, Daya M, et al; Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Amiodarone, lidocaine, or placebo in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1711-1722.

2. Joglar JA, Page RL. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--are drugs ever the answer? N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1781-1782.

Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Is Honored at Two Medical School Graduations on the Same Day

On Wednesday, May 25, 2016, Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, emergency physician-in-chief (1996-2016) and emergency medical services (EMS) medical director (1996- ) at New York Presbyterian Hospital, professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, was honored at two New York City medical school graduations.

First, at the midday Weill Cornell Medical College commencement exercises in Carnegie Hall, Dr Flomenbaum helped present the second annual “Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Prize for Excellence in Emergency Medicine,” a $50,000 award endowed by a generous gift named for Dr Flomenbaum by Jeanne and Herbert Seigel. A few hours later, at the Lincoln Center commencement exercises of his alma mater, Dr Flomenbaum received the “Albert Einstein College of Medicine 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award,” for, according to Einstein Dean Allen M. Spiegel, MD, his “extraordinary career in emergency medicine and...many contributions to the health and welfare of underserved communities and all populations in New York City.”

Dr Flomenbaum has dedicated his life to ensuring the highest quality emergency care for patients; to educating and training students, residents, and attending physicians; and to helping establish and support the specialty of emergency medicine. Dr Flomenbaum’s accomplishments include coauthoring and coediting eight editions of the leading medical toxicology textbook, two editions of a text on diagnostic testing, and more than 150 research and review papers, book chapters, and editorials. He has served as a senior examiner for the American Board of Emergency Medicine, senior consultant to the NYC Poison Control Center, a fellow and the founding chair of the New York Academy of Medicine Section on Emergency Medicine, and chair of the Medical Advisory Committee to NYC EMS. Prior to joining the Weill Cornell faculty in 1996, Dr Flomenbaum held academic appointments at Einstein, New York University, and SUNY/Downstate Schools of Medicine.

He received his bachelor’s degree from Columbia College in 1969, and his MD from Albert Einstein as an alpha omega alpha member of the class of 1973. Dr Flomenbaum completed an internal medicine residency at Einstein/Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx. In 1996, Dr Flomenbaum arrived at what was then New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical Center after serving as associate director of emergency medicine at Jacobi/Einstein and NYU/Bellevue Hospitals, and then as chairman of emergency medicine at SUNY/Long Island College Hospital.

According to the Dean of Weill Cornell Medical College, its Division of Emergency Medicine “has grown significantly in the last 20 years under the leadership of Dr Neal Flomenbaum and is operating at a scale and scope [of] an academic department.” At Weill Cornell, Dr Flomenbaum created the nation’s first fellowship and division of geriatric emergency medicine (GEM) in 2005, a decade before GEM fellowships were offered at other academic centers around the country; he also created divisions of medical toxicology, EM/critical care, and other traditional EM subspecialties. Dr Flomenbaum most recently embarked on creating a new fellowship and division of Women’s Health Emergencies.

Since 2006, Dr Flomenbaum has also been editor-in-chief of Emergency Medicine, the oldest and one of the most widely read journals for the specialty. His incisive monthly editorials on current concerns in emergency medicine and emergency departments are available at www.emed-journal.com and at www.NYMeDED.org.

Medication for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: For Which Patients Is It Effective?

BY JEFF BAUER

FROM N ENGL J MED

A recent double-blind, randomized trial that compared parenteral amiodarone, lidocaine, and saline placebo for patients who experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that overall, neither medication resulted in a significantly higher survival rate nor better neurological outcomes.1 However, among a subgroup of patients whose cardiac arrest was witnessed by a bystander, the rate of survival to hospital discharge was significantly higher with amiodarone or lidocaine than with placebo.

Researchers studied 3,026 adults who had nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and shock-refractory ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. These patients were treated in accordance with local emergency medical service (EMS) protocols that complied with American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for advanced life support. After one or more shocks failed to end ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, patients were randomly treated with one of three parenteral preparations: lidocaine (993 patients), a recently approved cyclodextrin-based formulation of amiodarone that is designed to reduce hypotensive effects (974 patients), or a normal saline placebo (1,059 patients). The initial treatment consisted of two syringes that were administered by rapid bolus. If the ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia persisted after this initial dose, a supplemental dose (one syringe) of the same drug was administered. The average time to treatment with these drugs was 19 minutes from the initial call to EMS. On arrival at the hospital, patients were treated with usual postcardiac arrest care in accordance with AHA guidelines.

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. The secondary outcome was survival with favorable neurological status at discharge, which was defined as a score of ≤3 on the modified Rankin scale, indicating the ability to conduct daily activities independently or with minimal assistance.

The hospital survival rates were 23.7% for patients who received lidocaine, 24.4% for those who received amiodarone, and 21.0% for those who received placebo. The differences in survival rates for each drug compared to placebo, and one drug compared to the other drug, were not statistically significant. Rates of survival with favorable neurological status were similar among all three groups.

However, among 1,934 patients who experienced a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, each drug was associated with a significantly higher rate of survival (5 percentage points) compared to placebo. In these patients, the survival rate was 27.8% with lidocaine, 27.7% with amiodarone, and 22.7% with placebo. This absolute risk difference was significant for lidocaine versus placebo and for amiodarone versus placebo, but not for lidocaine versus amiodarone.

Researchers said patients who have a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest presumably have “early recognition of cardiac arrest, a short interval between the patient’s collapse from cardiac arrest and the initiation of treatment, and a greater likelihood of therapeutic responsiveness.” In an accompanying editorial, Joglar and Page2 said EMS personnel should consider using lidocaine or amiodarone when a patient’s cardiac arrest is witnessed.

1. Kudenchuk PJ, Brown SP, Daya M, et al; Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Amiodarone, lidocaine, or placebo in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1711-1722.

2. Joglar JA, Page RL. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--are drugs ever the answer? N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1781-1782.

Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Is Honored at Two Medical School Graduations on the Same Day

On Wednesday, May 25, 2016, Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, emergency physician-in-chief (1996-2016) and emergency medical services (EMS) medical director (1996- ) at New York Presbyterian Hospital, professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, was honored at two New York City medical school graduations.

First, at the midday Weill Cornell Medical College commencement exercises in Carnegie Hall, Dr Flomenbaum helped present the second annual “Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Prize for Excellence in Emergency Medicine,” a $50,000 award endowed by a generous gift named for Dr Flomenbaum by Jeanne and Herbert Seigel. A few hours later, at the Lincoln Center commencement exercises of his alma mater, Dr Flomenbaum received the “Albert Einstein College of Medicine 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award,” for, according to Einstein Dean Allen M. Spiegel, MD, his “extraordinary career in emergency medicine and...many contributions to the health and welfare of underserved communities and all populations in New York City.”

Dr Flomenbaum has dedicated his life to ensuring the highest quality emergency care for patients; to educating and training students, residents, and attending physicians; and to helping establish and support the specialty of emergency medicine. Dr Flomenbaum’s accomplishments include coauthoring and coediting eight editions of the leading medical toxicology textbook, two editions of a text on diagnostic testing, and more than 150 research and review papers, book chapters, and editorials. He has served as a senior examiner for the American Board of Emergency Medicine, senior consultant to the NYC Poison Control Center, a fellow and the founding chair of the New York Academy of Medicine Section on Emergency Medicine, and chair of the Medical Advisory Committee to NYC EMS. Prior to joining the Weill Cornell faculty in 1996, Dr Flomenbaum held academic appointments at Einstein, New York University, and SUNY/Downstate Schools of Medicine.

He received his bachelor’s degree from Columbia College in 1969, and his MD from Albert Einstein as an alpha omega alpha member of the class of 1973. Dr Flomenbaum completed an internal medicine residency at Einstein/Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx. In 1996, Dr Flomenbaum arrived at what was then New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical Center after serving as associate director of emergency medicine at Jacobi/Einstein and NYU/Bellevue Hospitals, and then as chairman of emergency medicine at SUNY/Long Island College Hospital.

According to the Dean of Weill Cornell Medical College, its Division of Emergency Medicine “has grown significantly in the last 20 years under the leadership of Dr Neal Flomenbaum and is operating at a scale and scope [of] an academic department.” At Weill Cornell, Dr Flomenbaum created the nation’s first fellowship and division of geriatric emergency medicine (GEM) in 2005, a decade before GEM fellowships were offered at other academic centers around the country; he also created divisions of medical toxicology, EM/critical care, and other traditional EM subspecialties. Dr Flomenbaum most recently embarked on creating a new fellowship and division of Women’s Health Emergencies.

Since 2006, Dr Flomenbaum has also been editor-in-chief of Emergency Medicine, the oldest and one of the most widely read journals for the specialty. His incisive monthly editorials on current concerns in emergency medicine and emergency departments are available at www.emed-journal.com and at www.NYMeDED.org.

Medication for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: For Which Patients Is It Effective?

BY JEFF BAUER

FROM N ENGL J MED

A recent double-blind, randomized trial that compared parenteral amiodarone, lidocaine, and saline placebo for patients who experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that overall, neither medication resulted in a significantly higher survival rate nor better neurological outcomes.1 However, among a subgroup of patients whose cardiac arrest was witnessed by a bystander, the rate of survival to hospital discharge was significantly higher with amiodarone or lidocaine than with placebo.

Researchers studied 3,026 adults who had nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and shock-refractory ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. These patients were treated in accordance with local emergency medical service (EMS) protocols that complied with American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for advanced life support. After one or more shocks failed to end ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, patients were randomly treated with one of three parenteral preparations: lidocaine (993 patients), a recently approved cyclodextrin-based formulation of amiodarone that is designed to reduce hypotensive effects (974 patients), or a normal saline placebo (1,059 patients). The initial treatment consisted of two syringes that were administered by rapid bolus. If the ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia persisted after this initial dose, a supplemental dose (one syringe) of the same drug was administered. The average time to treatment with these drugs was 19 minutes from the initial call to EMS. On arrival at the hospital, patients were treated with usual postcardiac arrest care in accordance with AHA guidelines.

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. The secondary outcome was survival with favorable neurological status at discharge, which was defined as a score of ≤3 on the modified Rankin scale, indicating the ability to conduct daily activities independently or with minimal assistance.

The hospital survival rates were 23.7% for patients who received lidocaine, 24.4% for those who received amiodarone, and 21.0% for those who received placebo. The differences in survival rates for each drug compared to placebo, and one drug compared to the other drug, were not statistically significant. Rates of survival with favorable neurological status were similar among all three groups.

However, among 1,934 patients who experienced a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, each drug was associated with a significantly higher rate of survival (5 percentage points) compared to placebo. In these patients, the survival rate was 27.8% with lidocaine, 27.7% with amiodarone, and 22.7% with placebo. This absolute risk difference was significant for lidocaine versus placebo and for amiodarone versus placebo, but not for lidocaine versus amiodarone.

Researchers said patients who have a witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest presumably have “early recognition of cardiac arrest, a short interval between the patient’s collapse from cardiac arrest and the initiation of treatment, and a greater likelihood of therapeutic responsiveness.” In an accompanying editorial, Joglar and Page2 said EMS personnel should consider using lidocaine or amiodarone when a patient’s cardiac arrest is witnessed.

1. Kudenchuk PJ, Brown SP, Daya M, et al; Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Amiodarone, lidocaine, or placebo in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1711-1722.

2. Joglar JA, Page RL. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--are drugs ever the answer? N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1781-1782.

Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Is Honored at Two Medical School Graduations on the Same Day

On Wednesday, May 25, 2016, Emergency Medicine Editor-in-Chief Neal Flomenbaum, MD, emergency physician-in-chief (1996-2016) and emergency medical services (EMS) medical director (1996- ) at New York Presbyterian Hospital, professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, was honored at two New York City medical school graduations.

First, at the midday Weill Cornell Medical College commencement exercises in Carnegie Hall, Dr Flomenbaum helped present the second annual “Neal Flomenbaum, MD, Prize for Excellence in Emergency Medicine,” a $50,000 award endowed by a generous gift named for Dr Flomenbaum by Jeanne and Herbert Seigel. A few hours later, at the Lincoln Center commencement exercises of his alma mater, Dr Flomenbaum received the “Albert Einstein College of Medicine 2016 Lifetime Achievement Award,” for, according to Einstein Dean Allen M. Spiegel, MD, his “extraordinary career in emergency medicine and...many contributions to the health and welfare of underserved communities and all populations in New York City.”

Dr Flomenbaum has dedicated his life to ensuring the highest quality emergency care for patients; to educating and training students, residents, and attending physicians; and to helping establish and support the specialty of emergency medicine. Dr Flomenbaum’s accomplishments include coauthoring and coediting eight editions of the leading medical toxicology textbook, two editions of a text on diagnostic testing, and more than 150 research and review papers, book chapters, and editorials. He has served as a senior examiner for the American Board of Emergency Medicine, senior consultant to the NYC Poison Control Center, a fellow and the founding chair of the New York Academy of Medicine Section on Emergency Medicine, and chair of the Medical Advisory Committee to NYC EMS. Prior to joining the Weill Cornell faculty in 1996, Dr Flomenbaum held academic appointments at Einstein, New York University, and SUNY/Downstate Schools of Medicine.

He received his bachelor’s degree from Columbia College in 1969, and his MD from Albert Einstein as an alpha omega alpha member of the class of 1973. Dr Flomenbaum completed an internal medicine residency at Einstein/Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx. In 1996, Dr Flomenbaum arrived at what was then New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical Center after serving as associate director of emergency medicine at Jacobi/Einstein and NYU/Bellevue Hospitals, and then as chairman of emergency medicine at SUNY/Long Island College Hospital.

According to the Dean of Weill Cornell Medical College, its Division of Emergency Medicine “has grown significantly in the last 20 years under the leadership of Dr Neal Flomenbaum and is operating at a scale and scope [of] an academic department.” At Weill Cornell, Dr Flomenbaum created the nation’s first fellowship and division of geriatric emergency medicine (GEM) in 2005, a decade before GEM fellowships were offered at other academic centers around the country; he also created divisions of medical toxicology, EM/critical care, and other traditional EM subspecialties. Dr Flomenbaum most recently embarked on creating a new fellowship and division of Women’s Health Emergencies.

Since 2006, Dr Flomenbaum has also been editor-in-chief of Emergency Medicine, the oldest and one of the most widely read journals for the specialty. His incisive monthly editorials on current concerns in emergency medicine and emergency departments are available at www.emed-journal.com and at www.NYMeDED.org.

More Hospitals to Be Replaced by FSEDs

If an ED is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Fueled by continued hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now replacing hospitals in previously well-served urban areas in addition to serving rural areas lacking alternative facilities.

According to The New York Times (http://nyti.ms/1TB8Z44), since 2000, 19 New York City hospitals “have either closed or overhauled how they operate.” As this issue of Emergency Medicine went to press, plans had been announced to replace Manhattan’s Beth Israel and Brooklyn’s Wyckoff Heights hospitals with FSEDs and expanded outpatient facilities. These hospitals and many others that have recently closed, including St Vincent’s (2010) and the Long Island College Hospital (2014), had been part of the health care landscape in New York for over 125 years.

What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs), and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital-based EDs? Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers (UCCs) and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems. (See “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care” at http://bit.ly/1OSrHSA). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDs with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and registered nurses (RNs) provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7—a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized EM has enthusiastically embraced and endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCCs has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I trauma center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Should you think that FSEDs are a new phenomenon, you might be surprised to discover that in 1875, after New York Hospital (now part of New York Presbyterian) closed its original lower Manhattan site to move further uptown, it opened a “House of Relief” in its old neighborhood that contained an emergency treatment center, an operating room, an isolation area, a dispensary, a reception area, examination rooms, an ambulance entrance, and wards to observe and treat patients until they could be safely transported to the new main hospital. FSEDs served 19th-century patients well, and in the 21st century may serve as a reminder that sometimes even in medicine, “everything old is new again!” (See http://bit.ly/1NSPlDG.)

Editor’s Note: Portions of this editorial were previously published in Emergency Medicine.

If an ED is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Fueled by continued hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now replacing hospitals in previously well-served urban areas in addition to serving rural areas lacking alternative facilities.

According to The New York Times (http://nyti.ms/1TB8Z44), since 2000, 19 New York City hospitals “have either closed or overhauled how they operate.” As this issue of Emergency Medicine went to press, plans had been announced to replace Manhattan’s Beth Israel and Brooklyn’s Wyckoff Heights hospitals with FSEDs and expanded outpatient facilities. These hospitals and many others that have recently closed, including St Vincent’s (2010) and the Long Island College Hospital (2014), had been part of the health care landscape in New York for over 125 years.

What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs), and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital-based EDs? Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers (UCCs) and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems. (See “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care” at http://bit.ly/1OSrHSA). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDs with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and registered nurses (RNs) provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7—a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized EM has enthusiastically embraced and endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCCs has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I trauma center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Should you think that FSEDs are a new phenomenon, you might be surprised to discover that in 1875, after New York Hospital (now part of New York Presbyterian) closed its original lower Manhattan site to move further uptown, it opened a “House of Relief” in its old neighborhood that contained an emergency treatment center, an operating room, an isolation area, a dispensary, a reception area, examination rooms, an ambulance entrance, and wards to observe and treat patients until they could be safely transported to the new main hospital. FSEDs served 19th-century patients well, and in the 21st century may serve as a reminder that sometimes even in medicine, “everything old is new again!” (See http://bit.ly/1NSPlDG.)

Editor’s Note: Portions of this editorial were previously published in Emergency Medicine.

If an ED is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Fueled by continued hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now replacing hospitals in previously well-served urban areas in addition to serving rural areas lacking alternative facilities.

According to The New York Times (http://nyti.ms/1TB8Z44), since 2000, 19 New York City hospitals “have either closed or overhauled how they operate.” As this issue of Emergency Medicine went to press, plans had been announced to replace Manhattan’s Beth Israel and Brooklyn’s Wyckoff Heights hospitals with FSEDs and expanded outpatient facilities. These hospitals and many others that have recently closed, including St Vincent’s (2010) and the Long Island College Hospital (2014), had been part of the health care landscape in New York for over 125 years.

What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs), and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital-based EDs? Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers (UCCs) and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems. (See “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care” at http://bit.ly/1OSrHSA). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDs with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and registered nurses (RNs) provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7—a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized EM has enthusiastically embraced and endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCCs has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I trauma center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Should you think that FSEDs are a new phenomenon, you might be surprised to discover that in 1875, after New York Hospital (now part of New York Presbyterian) closed its original lower Manhattan site to move further uptown, it opened a “House of Relief” in its old neighborhood that contained an emergency treatment center, an operating room, an isolation area, a dispensary, a reception area, examination rooms, an ambulance entrance, and wards to observe and treat patients until they could be safely transported to the new main hospital. FSEDs served 19th-century patients well, and in the 21st century may serve as a reminder that sometimes even in medicine, “everything old is new again!” (See http://bit.ly/1NSPlDG.)

Editor’s Note: Portions of this editorial were previously published in Emergency Medicine.

Optical Imaging to Detect Lentigo Maligna

In an article published online on January 26 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, my colleagues and I (Menge et al) reported on the use of reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) for challenging facial lesions. We studied the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM) based on RCM versus the histopathologic diagnosis after biopsy.

In this study 17 patients were seen for evaluation of known or suspected LM at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York). Among these patients, a total of 63 sites on the skin were evaluated using RCM and a presumptive diagnosis was made. These sites were then biopsied to compare the diagnosis using RCM with that made by histopathology. When LM was present as determined by biopsy, RCM also was able to detect it 100% of the time (sensitivity). When LM was absent as determined by biopsy, RCM also indicated it was absent 71% of the time (specificity).

What’s the issue?

Lentigo maligna is a form of melanoma in situ occurring on sun-damaged skin. It can be quite subtle to detect clinically and therefore may go undiagnosed for a while. Lentigo maligna also has been shown to have notable subclinical extension with which traditional surgical margins for truncal melanoma may be too narrow to clear LM on the head and neck. Therefore, presurgical consultation may be difficult due to the amorphous borders. Random blind biopsies also are discouraged because of sampling error.

Additionally, repetitive biopsies over time, which may be frequently needed in individuals with heavy sun exposure, can be costly and cause adverse effects.

This study showed the usefulness and reliability of using RCM for challenging facial lesions that are suspicious for LM. The sensitivity and specificity of RCM in this study indicated that this technology performs well in detecting LM when present; however, false-positives were noted in this study. False-positives included pigmented actinic keratosis and melanocytosis. Dermatologists who are advanced in RCM technology and interpretation also were utilized in this study. More research is needed to understand how to best utilize this technology, but overall the ability of RCM to accurately identify LM without biopsy represents an exciting new development in how dermatologists can better diagnose, manage, and treat melanoma.

How will you adopt advances in cutaneous noninvasive imaging?

In an article published online on January 26 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, my colleagues and I (Menge et al) reported on the use of reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) for challenging facial lesions. We studied the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM) based on RCM versus the histopathologic diagnosis after biopsy.

In this study 17 patients were seen for evaluation of known or suspected LM at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York). Among these patients, a total of 63 sites on the skin were evaluated using RCM and a presumptive diagnosis was made. These sites were then biopsied to compare the diagnosis using RCM with that made by histopathology. When LM was present as determined by biopsy, RCM also was able to detect it 100% of the time (sensitivity). When LM was absent as determined by biopsy, RCM also indicated it was absent 71% of the time (specificity).

What’s the issue?

Lentigo maligna is a form of melanoma in situ occurring on sun-damaged skin. It can be quite subtle to detect clinically and therefore may go undiagnosed for a while. Lentigo maligna also has been shown to have notable subclinical extension with which traditional surgical margins for truncal melanoma may be too narrow to clear LM on the head and neck. Therefore, presurgical consultation may be difficult due to the amorphous borders. Random blind biopsies also are discouraged because of sampling error.

Additionally, repetitive biopsies over time, which may be frequently needed in individuals with heavy sun exposure, can be costly and cause adverse effects.

This study showed the usefulness and reliability of using RCM for challenging facial lesions that are suspicious for LM. The sensitivity and specificity of RCM in this study indicated that this technology performs well in detecting LM when present; however, false-positives were noted in this study. False-positives included pigmented actinic keratosis and melanocytosis. Dermatologists who are advanced in RCM technology and interpretation also were utilized in this study. More research is needed to understand how to best utilize this technology, but overall the ability of RCM to accurately identify LM without biopsy represents an exciting new development in how dermatologists can better diagnose, manage, and treat melanoma.

How will you adopt advances in cutaneous noninvasive imaging?

In an article published online on January 26 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, my colleagues and I (Menge et al) reported on the use of reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) for challenging facial lesions. We studied the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM) based on RCM versus the histopathologic diagnosis after biopsy.

In this study 17 patients were seen for evaluation of known or suspected LM at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York). Among these patients, a total of 63 sites on the skin were evaluated using RCM and a presumptive diagnosis was made. These sites were then biopsied to compare the diagnosis using RCM with that made by histopathology. When LM was present as determined by biopsy, RCM also was able to detect it 100% of the time (sensitivity). When LM was absent as determined by biopsy, RCM also indicated it was absent 71% of the time (specificity).

What’s the issue?

Lentigo maligna is a form of melanoma in situ occurring on sun-damaged skin. It can be quite subtle to detect clinically and therefore may go undiagnosed for a while. Lentigo maligna also has been shown to have notable subclinical extension with which traditional surgical margins for truncal melanoma may be too narrow to clear LM on the head and neck. Therefore, presurgical consultation may be difficult due to the amorphous borders. Random blind biopsies also are discouraged because of sampling error.

Additionally, repetitive biopsies over time, which may be frequently needed in individuals with heavy sun exposure, can be costly and cause adverse effects.

This study showed the usefulness and reliability of using RCM for challenging facial lesions that are suspicious for LM. The sensitivity and specificity of RCM in this study indicated that this technology performs well in detecting LM when present; however, false-positives were noted in this study. False-positives included pigmented actinic keratosis and melanocytosis. Dermatologists who are advanced in RCM technology and interpretation also were utilized in this study. More research is needed to understand how to best utilize this technology, but overall the ability of RCM to accurately identify LM without biopsy represents an exciting new development in how dermatologists can better diagnose, manage, and treat melanoma.

How will you adopt advances in cutaneous noninvasive imaging?

Spontaneous Repigmentation of Silvery Hair in an Infant With Congenital Hydrops Fetalis and Hypoproteinemia

Silvery hair is characteristic of 3 rare autosomal-recessive disorders—Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), Elejalde syndrome (ES), and Griscelli syndrome (GS)—which are associated with mutations in various genes that encode several proteins involved in the intracellular processing and movement of melanosomes. We report the case of a 2-month-old male infant with transient silvery hair and generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes who did not have any genetic mutations associated with the classic syndromes that usually are characterized by transient silvery hair.

Case Report

A 2-month-old male infant presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of silvery hair with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 1) that had developed at 1 month of age. His parents were healthy, nonconsanguineous, and reported no family history of silvery hair. The patient was delivered by cesarean section at 35 weeks’ gestation. His medical history was remarkable for congenital hydrops fetalis with pleuropericardial effusion, ascites, soft-tissue edema, and hydrocele with no signs of any congenital infection. Both the patient and his mother were O Rh +.

Several studies were performed following delivery. A direct Coombs test was negative. Blood studies revealed hypothyroidism and hypoalbuminemia secondary to protein loss associated with fetal hydrops. Cerebral, abdominal, and renal ultrasound; echocardiogram; thoracic and abdominal computed tomography; and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormalities.

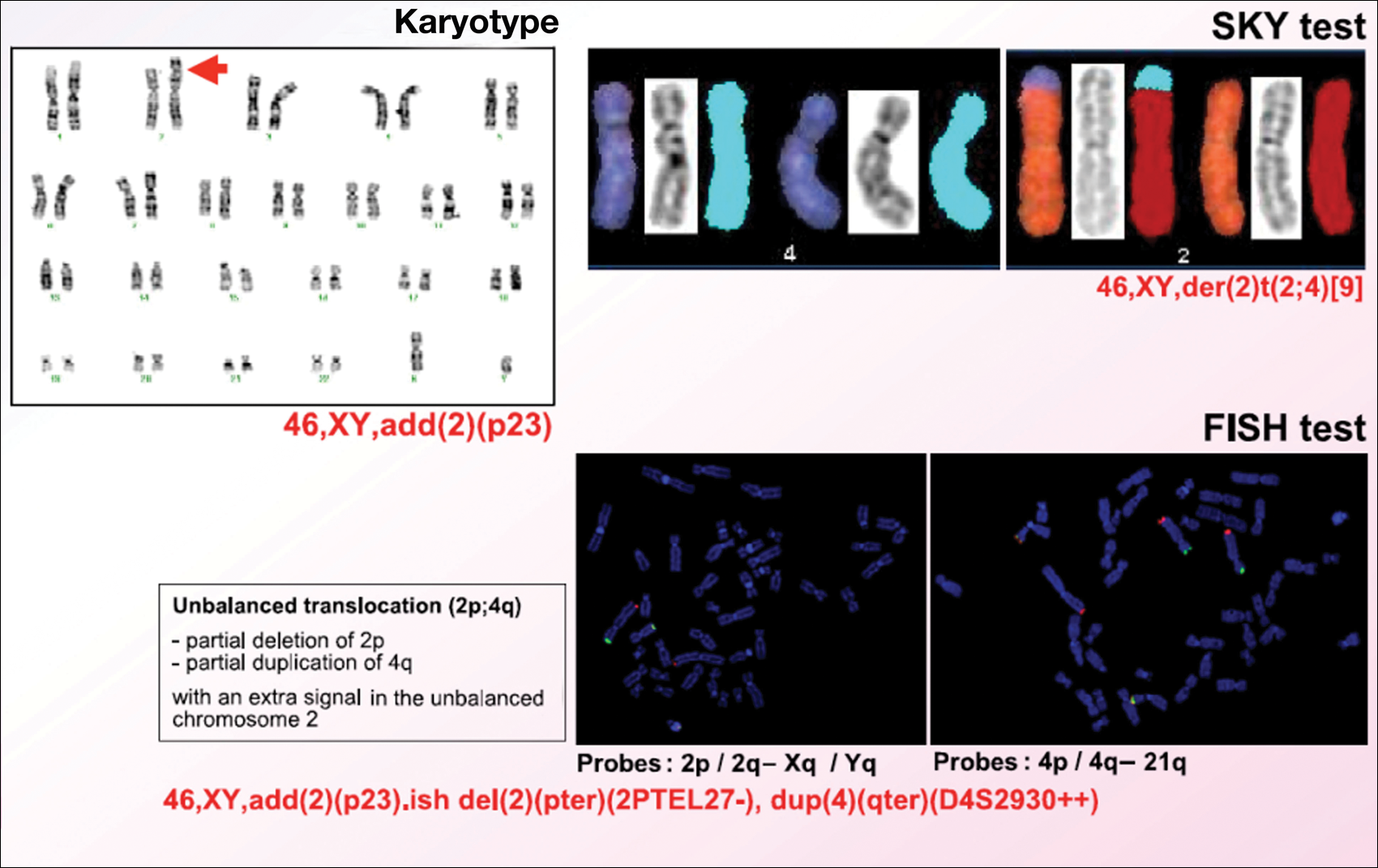

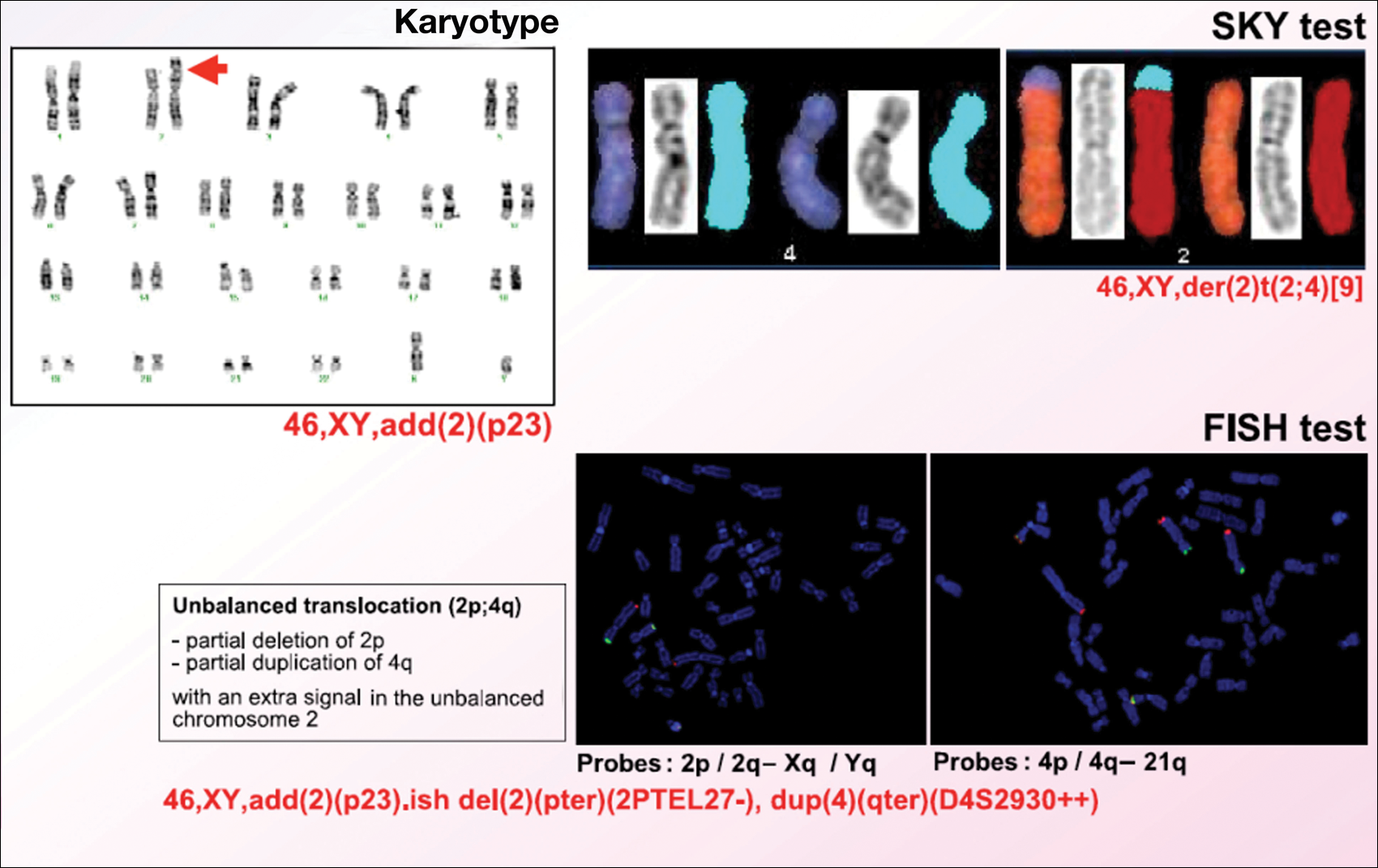

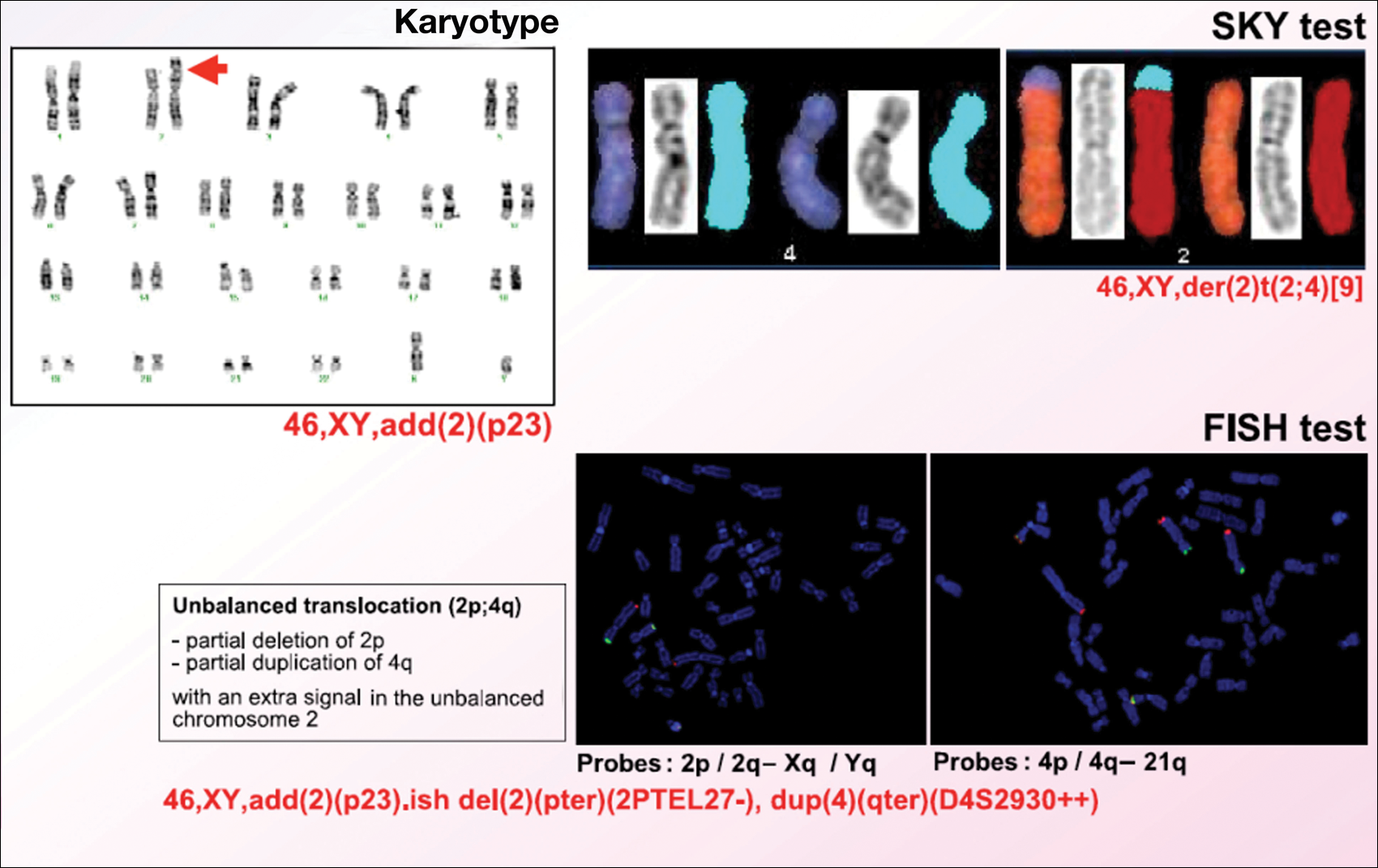

Karyotype results showed 46,XY,add(2)(p23), and subsequent spectral karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization tests identified a chromosomal abnormality (46,XY,add[2][p23].ish del[2][pter][2PTEL27‒], dup[4][qter][D4S2930++])(Figure 2). Parental karyotypes were normal.

After birth, the infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 50 days and received pleural and peritoneal drainages, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, parenteral nutrition with resolution of the hypoalbuminemia, levothyroxine, and intravenous antibiotics for central venous catheter infection. No drugs known to be associated with hypopigmentation of the hair, skin, or eyes were administered.

Two weeks after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit, the patient was referred to our department. Physical examination revealed silvery hair on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes. Abdominal, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic examination revealed no abnormalities, and no hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, nystagmus, or strabismus was noted.

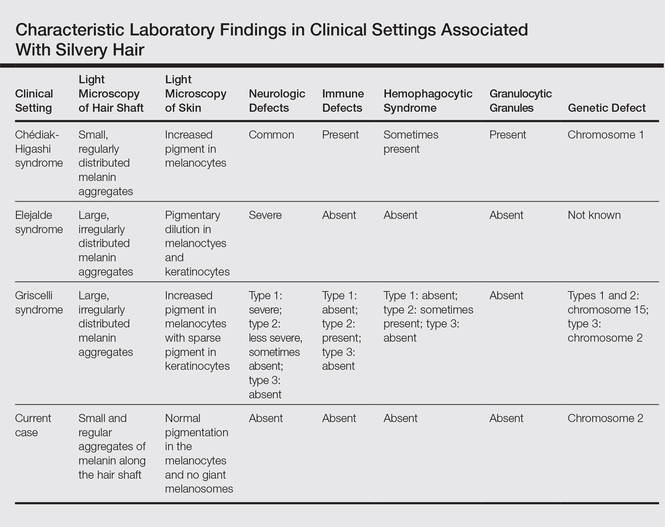

Light microscopy of the hair revealed small and regular aggregates of melanin along the hair shaft, predominantly in the medulla (Figure 3). Light microscopy of a skin biopsy specimen showed normal pigmentation in the melanocytes and no giant melanosomes. The melanocyte count was within reference range. A peripheral blood smear showed no giant granules in the granulocytes. No treatment was administered and the patient was followed closely every month. When the patient returned for follow-up at 9 months of age, physical examination revealed brown hair on the head, eyebrows, and eyelashes, as well as normal pigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 4). Thyroid function was normal and no recurrent infections of any type were noted. At follow-up at the age of 4 years, he showed normal neurological and psychological development with brown hair, no recurrent infections, and normal thyroid function. Given that CHS, ES, and GS had been ruled out, the clinical presentation and the genetic mutation detected may indicate that this case represents a new entity characterized by transient silvery hair.

Comment

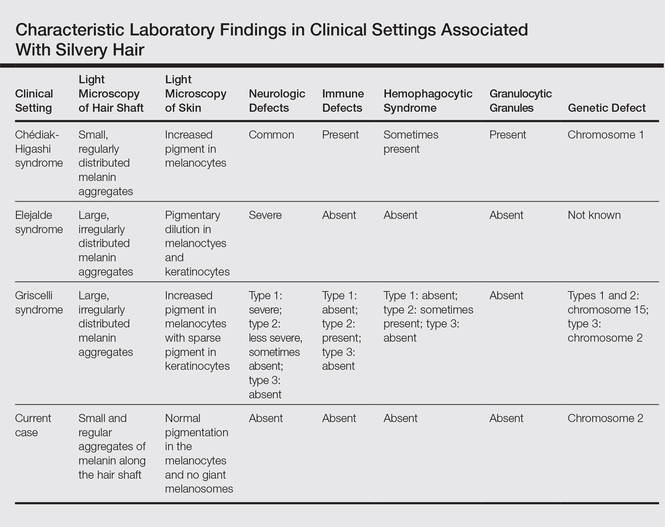

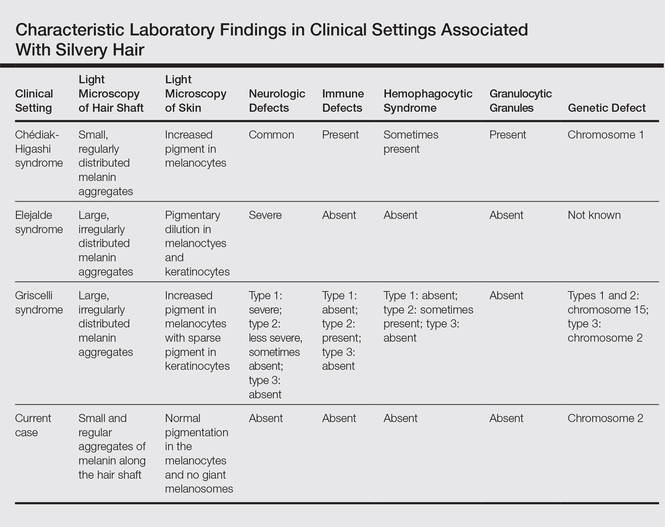

Silvery hair is a known feature of CHS, ES, and GS (Table). The characteristic hypopigmentation associated with these autosomal-recessive disorders is the result of impaired melanosome transport leading to failed transfer of melanin to keratinocytes. These disorders differ from oculocutaneous albinism in that melanin synthesis is unaffected.

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is characterized by generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, silvery hair, neurologic and immune dysfunction, lymphoproliferative disorders, and large granules in granulocytes and other cell types.1-3 A common complication of CHS is hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is characterized by fever, jaundice, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia.4 Pigmentary dilution of the irises also may be present, along with photophobia, strabismus, nystagmus, and impaired visual acuity. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is the result of a genetic defect in the lysosomal trafficking regulator gene, also known as CHS1 (located on chromosome 1q42.1‒q42.2).5 Melanin in the hair shaft is distributed uniformly in multiple small aggregates. Light microscopy of the skin typically shows giant melanosomes in melanocytes and aberrant keratinocyte maturation.

Elejalde syndrome is characterized by silvery hair (eyelashes and eyebrows), neurologic defects, and normal immunologic function.6,7 The underlying molecular basis remains unknown. It appears related to or allelic to GS type 1 and thus associated with mutations in MYO5A (myosin VA); however, the gene mutation responsible has yet to be defined.8 Light microscopy of the hair shaft usually shows an irregular distribution of large melanin aggregates, primarily in the medulla.9,10 Skin biopsy generally shows irregular distribution and irregular size of melanin granules in the basal layer.11 Leukocytes usually show no abnormal cytoplasmic granules. Ocular involvement is common and may present as nystagmus, diplopia, hypopigmented retinas, and/or papilledema.

In GS, hair microscopy generally reveals large aggregates of melanin pigment distributed irregularly along the hair shaft. Granulocytes typically show no giant granules. Light microscopy of the skin usually shows increased pigment in melanocytes with sparse pigment in keratinocytes. Griscelli syndrome is classified into 3 types.12 In GS type 1, patients have silvery gray hair, light-colored skin, severe neurologic defects,13 and normal immune status. This variant is caused by a mutation in the MYO5A gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 2, patients have silvery gray hair, pyogenic infections, an accelerated phase of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and variable neurologic defects in the absence of primary neurologic disease.14,15 This variant is caused by a mutation in the RAB27A (member RAS oncogene family) gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 3, patients exhibit generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and hair with no abnormalities of the nervous or immune systems. There are 2 different mutations associated with GS type 3: the first is located on chromosome 2q37.3, causing a mutation in MLPH (melanophilin), and the second is caused by an F-exon deletion in the MYO5A gene.14

Our patient had silvery hair, generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, and normal central nervous system function with no other ocular involvement and no evidence of recurrent infections of any kind. Light microscopy showed small and regular melanin pigment aggregates in the hair shaft, which differs from the irregular pigment aggregates in GS and ES.

The regular melanin pigment aggregates observed along the hair shaft were consistent with CHS, but other manifestations of this syndrome were absent: ocular, neurologic, hematologic, and immunologic abnormalities with presence of giant intracytoplasmic granules in leukocytes, and giant melanosomes in melanocytes. In our patient, the absence of these features along with the spontaneous repigmentation of the silvery hair, improvement of thyroid function, reversal of hypoalbuminemia, and the chromosomopathy detected make a diagnosis of CHS highly improbable.

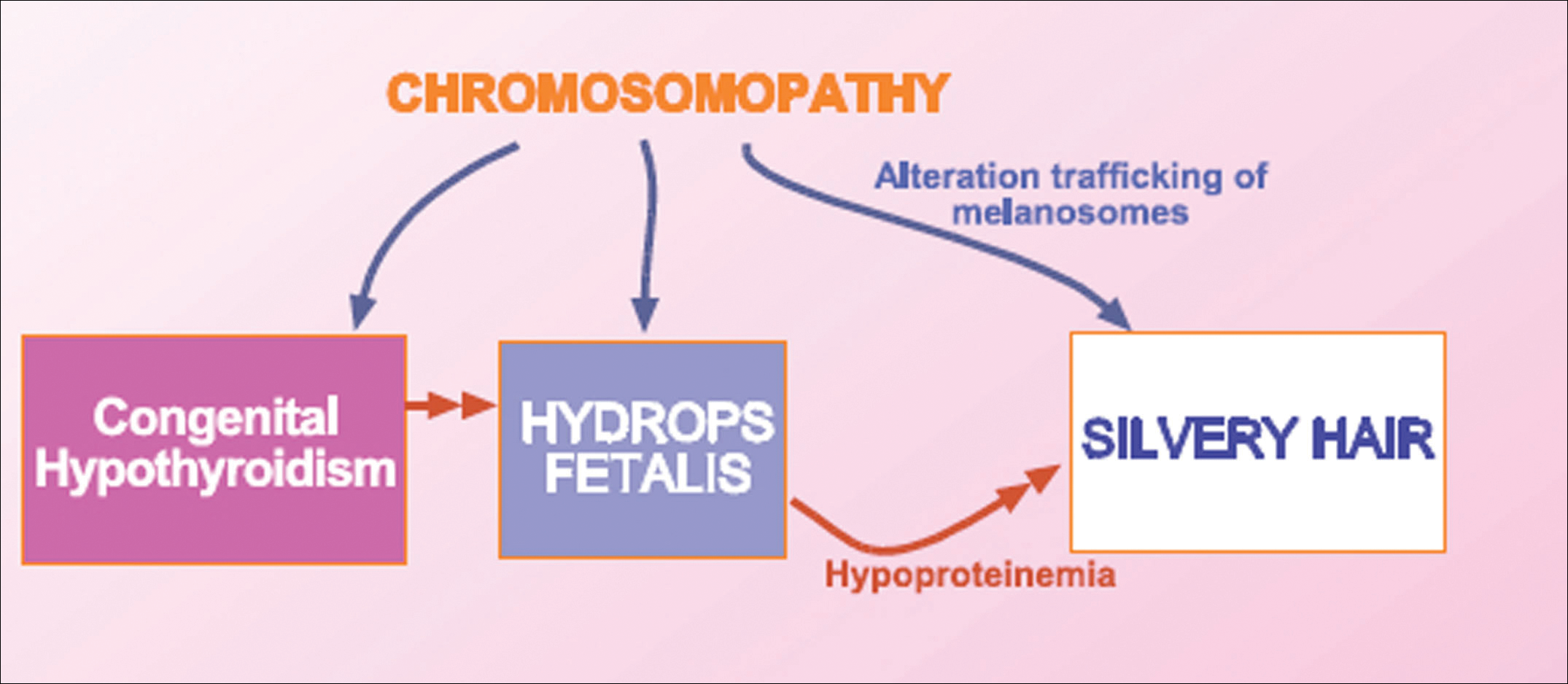

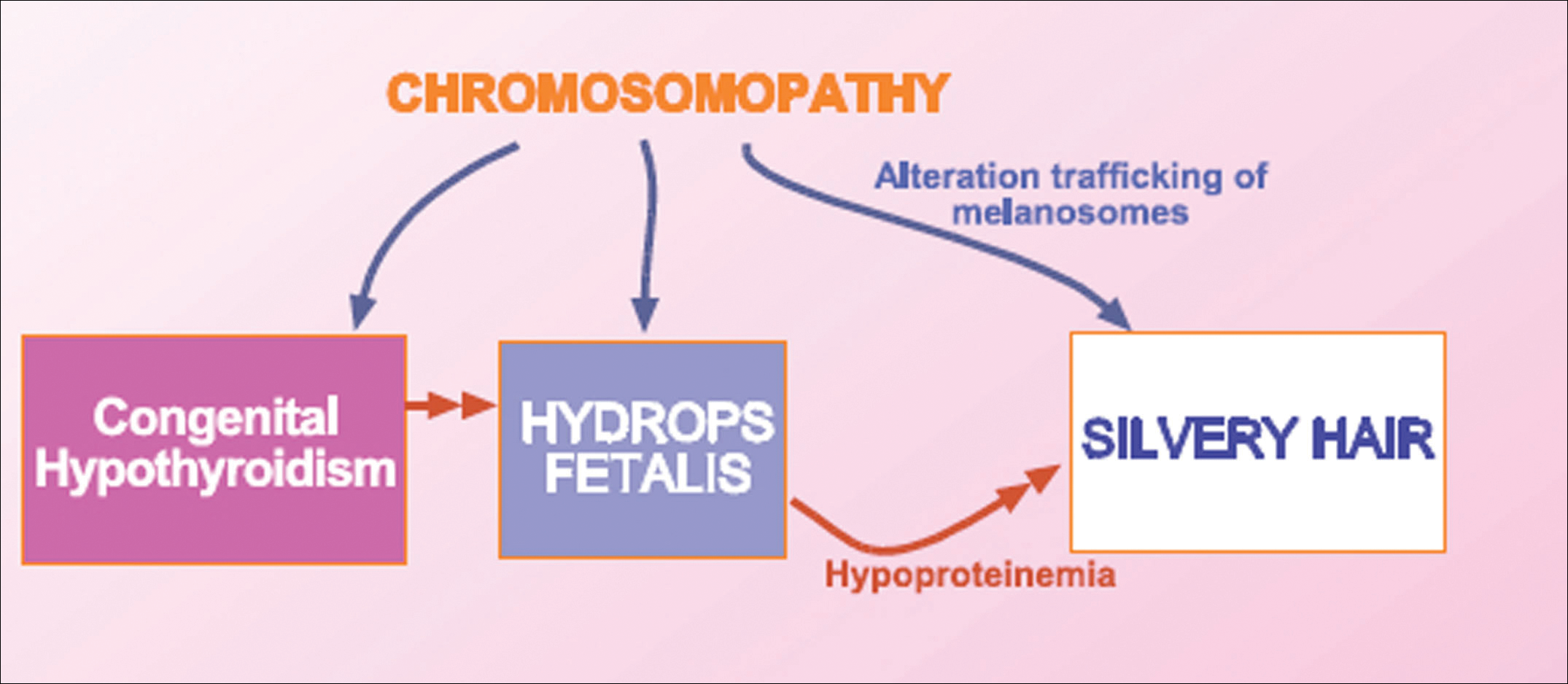

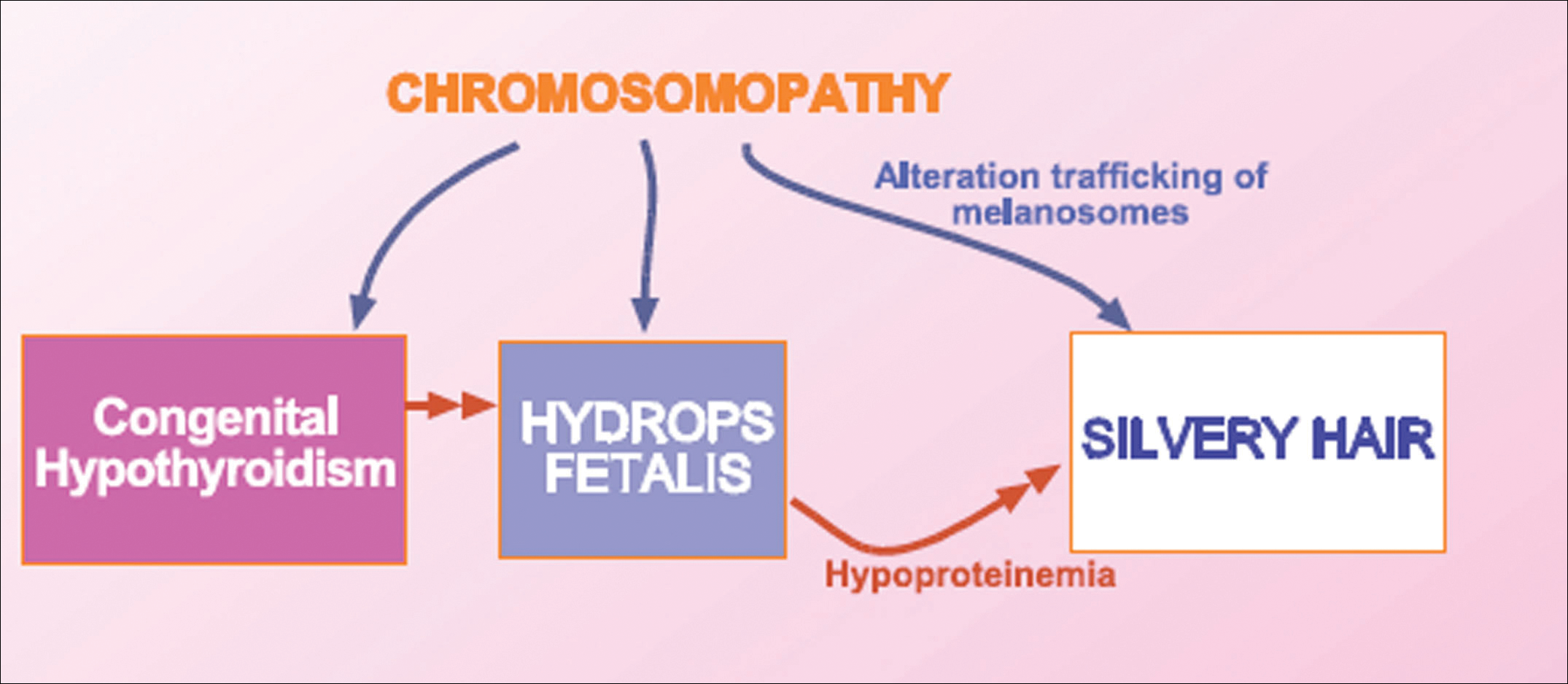

We concluded that the silvery hair noted in our patient resulted from the 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality. This mutation could affect some of the genes that control the trafficking of melanosomes or could induce hypothyroidism and hypoproteinemia associated with congenital hydrops fetalis (Figure 5).

Hydrops fetalis is a potentially fatal condition characterized by severe edema (swelling) in a fetus or neonate. There are 2 types of hydrops fetalis: immune and nonimmune. Immune hydrops fetalis may develop in an Rh+ fetus with an Rh– mother, as the mother’s immune cells begin to break down the red blood cells of the fetus, resulting in anemia in the fetus with subsequent fetal heart failure, leading to an accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the tissues and organs. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis can occur secondary to diseases that interfere with the fetus’s ability to manage fluid (eg, severe anemia; congenital infections; urinary, lymphatic, heart, or thoracic defects; inborn errors of metabolism; chromosomal abnormalities). Case studies have suggested that congenital hypothyroidism could be a cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis.16,17 Thyroid hormone deficiency reduces stimulation of adrenergic receptors in the lymphatic system and lungs, thereby decreasing lymph flow and protein efflux to the lymphatic system and decreasing clearance of liquid from the lungs. The final result is lymph vessel engorgement and subsequent leakage of lymphatic fluid to pleural spaces, causing hydrops fetalis and chylothorax.

The 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality has not been commonly associated with hypothyroidism and hydrops fetalis. The silvery hair in our patient was transient and spontaneously repigmented to brown over the course of follow-up in conjunction with improved physiologic changes. We concluded that the silvery hair in our patient was induced by his hypoproteinemic status secondary to hydrops fetalis and hypothyroidism.

Conclusion

In addition to CHS, ES, and GS, the differential diagnosis for silvery hair with abnormal skin pigmentation in children should include 46,XY,add(2)(p23) mutation, as was detected in our patient. Evaluation should include light microscopy of the hair shaft, skin biopsy, assessment of immune function, peripheral blood smear, and neurologic and eye examinations.

- White JG. The Chédiak-Higashi syndrome: a possible lysosomal disease. Blood. 1966;28:143-156.

- Introne W, Boissy RE, Gahl WA. Clinical, molecular, and cell biological aspects of Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68:283-303.

- Kaplan J, De Domenico I, Ward DM. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:22-29.

- Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [published online December 7, 2006]. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:95-109.

- Morrone K, Wang Y, Huizing M, et al. Two novel mutations identified in an African-American child with Chédiak-Higashi syndrome [published online March 24, 2010]. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:967535.

- Ivanovich J, Mallory S, Storer T, et al. 12-year-old male with Elejalde syndrome (neuroectodermal melanolysosomal disease). Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:313-316.

- Cahali JB, Fernandez SA, Oliveira ZN, et al. Elejalde syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:479-482.

- Bahadoran P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R, et al. Comment on Elejalde syndrome and relationship with Griscelli syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2003;116:408-409.

- Duran-McKinster C, Rodriguez-Jurado R, Ridaura C, et al. Elejalde syndrome—a melanolysosomal neurocutaneous syndrome: clinical and morphological findings in 7 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:182-186.

- Happle R. Neurocutaneous diseases. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:2131-2148.

- Sanal O, Yel L, Kucukali T, et al. An allelic variant of Griscelli disease: presentation with severe hypotonia, mental-motor retardation, and hypopigmentation consistent with Elejalde syndrome (neuroectodermal melanolysosomal disorder). J Neurol. 2000;247:570-572.

- Malhotra AK, Bhaskar G, Nanda M, et al. Griscelli syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:337-340.

- Al-Idrissi E, ElGhazali G, Alzahrani M, et al. Premature birth, respiratory distress, intracerebral hemorrhage, and silvery-gray hair: differential diagnosis of the 3 types of Griscelli syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:494-496.

- Ménasché G, Ho CH, Sanal O, et al. Griscelli syndrome restricted to hypopigmentation results from a melanophilin defect (GS3) or a MYO5A F-exon deletion (GS1). J Clin Invest. 2003;112:450-456.

- Griscelli C, Durandy A, Guy-Grand D, et al. A syndrome associating partial albinism and immunodeficiency. Am J Med. 1978;65:691-702.

- Narchi H. Congenital hypothyroidism and nonimmune hydrops fetalis: associated? Pediatrics. 1999;104:1416-1417.

- Kessel I, Makhoul IR, Sujov P. Congenital hypothyroidism and nonimmune hydrops fetalis: associated? Pediatrics. 1999;103:E9.

Silvery hair is characteristic of 3 rare autosomal-recessive disorders—Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), Elejalde syndrome (ES), and Griscelli syndrome (GS)—which are associated with mutations in various genes that encode several proteins involved in the intracellular processing and movement of melanosomes. We report the case of a 2-month-old male infant with transient silvery hair and generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes who did not have any genetic mutations associated with the classic syndromes that usually are characterized by transient silvery hair.

Case Report

A 2-month-old male infant presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of silvery hair with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 1) that had developed at 1 month of age. His parents were healthy, nonconsanguineous, and reported no family history of silvery hair. The patient was delivered by cesarean section at 35 weeks’ gestation. His medical history was remarkable for congenital hydrops fetalis with pleuropericardial effusion, ascites, soft-tissue edema, and hydrocele with no signs of any congenital infection. Both the patient and his mother were O Rh +.

Several studies were performed following delivery. A direct Coombs test was negative. Blood studies revealed hypothyroidism and hypoalbuminemia secondary to protein loss associated with fetal hydrops. Cerebral, abdominal, and renal ultrasound; echocardiogram; thoracic and abdominal computed tomography; and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormalities.

Karyotype results showed 46,XY,add(2)(p23), and subsequent spectral karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization tests identified a chromosomal abnormality (46,XY,add[2][p23].ish del[2][pter][2PTEL27‒], dup[4][qter][D4S2930++])(Figure 2). Parental karyotypes were normal.

After birth, the infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 50 days and received pleural and peritoneal drainages, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, parenteral nutrition with resolution of the hypoalbuminemia, levothyroxine, and intravenous antibiotics for central venous catheter infection. No drugs known to be associated with hypopigmentation of the hair, skin, or eyes were administered.

Two weeks after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit, the patient was referred to our department. Physical examination revealed silvery hair on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes. Abdominal, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic examination revealed no abnormalities, and no hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, nystagmus, or strabismus was noted.

Light microscopy of the hair revealed small and regular aggregates of melanin along the hair shaft, predominantly in the medulla (Figure 3). Light microscopy of a skin biopsy specimen showed normal pigmentation in the melanocytes and no giant melanosomes. The melanocyte count was within reference range. A peripheral blood smear showed no giant granules in the granulocytes. No treatment was administered and the patient was followed closely every month. When the patient returned for follow-up at 9 months of age, physical examination revealed brown hair on the head, eyebrows, and eyelashes, as well as normal pigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 4). Thyroid function was normal and no recurrent infections of any type were noted. At follow-up at the age of 4 years, he showed normal neurological and psychological development with brown hair, no recurrent infections, and normal thyroid function. Given that CHS, ES, and GS had been ruled out, the clinical presentation and the genetic mutation detected may indicate that this case represents a new entity characterized by transient silvery hair.

Comment

Silvery hair is a known feature of CHS, ES, and GS (Table). The characteristic hypopigmentation associated with these autosomal-recessive disorders is the result of impaired melanosome transport leading to failed transfer of melanin to keratinocytes. These disorders differ from oculocutaneous albinism in that melanin synthesis is unaffected.

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is characterized by generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, silvery hair, neurologic and immune dysfunction, lymphoproliferative disorders, and large granules in granulocytes and other cell types.1-3 A common complication of CHS is hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is characterized by fever, jaundice, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia.4 Pigmentary dilution of the irises also may be present, along with photophobia, strabismus, nystagmus, and impaired visual acuity. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is the result of a genetic defect in the lysosomal trafficking regulator gene, also known as CHS1 (located on chromosome 1q42.1‒q42.2).5 Melanin in the hair shaft is distributed uniformly in multiple small aggregates. Light microscopy of the skin typically shows giant melanosomes in melanocytes and aberrant keratinocyte maturation.

Elejalde syndrome is characterized by silvery hair (eyelashes and eyebrows), neurologic defects, and normal immunologic function.6,7 The underlying molecular basis remains unknown. It appears related to or allelic to GS type 1 and thus associated with mutations in MYO5A (myosin VA); however, the gene mutation responsible has yet to be defined.8 Light microscopy of the hair shaft usually shows an irregular distribution of large melanin aggregates, primarily in the medulla.9,10 Skin biopsy generally shows irregular distribution and irregular size of melanin granules in the basal layer.11 Leukocytes usually show no abnormal cytoplasmic granules. Ocular involvement is common and may present as nystagmus, diplopia, hypopigmented retinas, and/or papilledema.

In GS, hair microscopy generally reveals large aggregates of melanin pigment distributed irregularly along the hair shaft. Granulocytes typically show no giant granules. Light microscopy of the skin usually shows increased pigment in melanocytes with sparse pigment in keratinocytes. Griscelli syndrome is classified into 3 types.12 In GS type 1, patients have silvery gray hair, light-colored skin, severe neurologic defects,13 and normal immune status. This variant is caused by a mutation in the MYO5A gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 2, patients have silvery gray hair, pyogenic infections, an accelerated phase of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and variable neurologic defects in the absence of primary neurologic disease.14,15 This variant is caused by a mutation in the RAB27A (member RAS oncogene family) gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 3, patients exhibit generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and hair with no abnormalities of the nervous or immune systems. There are 2 different mutations associated with GS type 3: the first is located on chromosome 2q37.3, causing a mutation in MLPH (melanophilin), and the second is caused by an F-exon deletion in the MYO5A gene.14

Our patient had silvery hair, generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, and normal central nervous system function with no other ocular involvement and no evidence of recurrent infections of any kind. Light microscopy showed small and regular melanin pigment aggregates in the hair shaft, which differs from the irregular pigment aggregates in GS and ES.

The regular melanin pigment aggregates observed along the hair shaft were consistent with CHS, but other manifestations of this syndrome were absent: ocular, neurologic, hematologic, and immunologic abnormalities with presence of giant intracytoplasmic granules in leukocytes, and giant melanosomes in melanocytes. In our patient, the absence of these features along with the spontaneous repigmentation of the silvery hair, improvement of thyroid function, reversal of hypoalbuminemia, and the chromosomopathy detected make a diagnosis of CHS highly improbable.

We concluded that the silvery hair noted in our patient resulted from the 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality. This mutation could affect some of the genes that control the trafficking of melanosomes or could induce hypothyroidism and hypoproteinemia associated with congenital hydrops fetalis (Figure 5).

Hydrops fetalis is a potentially fatal condition characterized by severe edema (swelling) in a fetus or neonate. There are 2 types of hydrops fetalis: immune and nonimmune. Immune hydrops fetalis may develop in an Rh+ fetus with an Rh– mother, as the mother’s immune cells begin to break down the red blood cells of the fetus, resulting in anemia in the fetus with subsequent fetal heart failure, leading to an accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the tissues and organs. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis can occur secondary to diseases that interfere with the fetus’s ability to manage fluid (eg, severe anemia; congenital infections; urinary, lymphatic, heart, or thoracic defects; inborn errors of metabolism; chromosomal abnormalities). Case studies have suggested that congenital hypothyroidism could be a cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis.16,17 Thyroid hormone deficiency reduces stimulation of adrenergic receptors in the lymphatic system and lungs, thereby decreasing lymph flow and protein efflux to the lymphatic system and decreasing clearance of liquid from the lungs. The final result is lymph vessel engorgement and subsequent leakage of lymphatic fluid to pleural spaces, causing hydrops fetalis and chylothorax.

The 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality has not been commonly associated with hypothyroidism and hydrops fetalis. The silvery hair in our patient was transient and spontaneously repigmented to brown over the course of follow-up in conjunction with improved physiologic changes. We concluded that the silvery hair in our patient was induced by his hypoproteinemic status secondary to hydrops fetalis and hypothyroidism.

Conclusion

In addition to CHS, ES, and GS, the differential diagnosis for silvery hair with abnormal skin pigmentation in children should include 46,XY,add(2)(p23) mutation, as was detected in our patient. Evaluation should include light microscopy of the hair shaft, skin biopsy, assessment of immune function, peripheral blood smear, and neurologic and eye examinations.

Silvery hair is characteristic of 3 rare autosomal-recessive disorders—Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), Elejalde syndrome (ES), and Griscelli syndrome (GS)—which are associated with mutations in various genes that encode several proteins involved in the intracellular processing and movement of melanosomes. We report the case of a 2-month-old male infant with transient silvery hair and generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes who did not have any genetic mutations associated with the classic syndromes that usually are characterized by transient silvery hair.

Case Report

A 2-month-old male infant presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of silvery hair with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 1) that had developed at 1 month of age. His parents were healthy, nonconsanguineous, and reported no family history of silvery hair. The patient was delivered by cesarean section at 35 weeks’ gestation. His medical history was remarkable for congenital hydrops fetalis with pleuropericardial effusion, ascites, soft-tissue edema, and hydrocele with no signs of any congenital infection. Both the patient and his mother were O Rh +.

Several studies were performed following delivery. A direct Coombs test was negative. Blood studies revealed hypothyroidism and hypoalbuminemia secondary to protein loss associated with fetal hydrops. Cerebral, abdominal, and renal ultrasound; echocardiogram; thoracic and abdominal computed tomography; and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormalities.

Karyotype results showed 46,XY,add(2)(p23), and subsequent spectral karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization tests identified a chromosomal abnormality (46,XY,add[2][p23].ish del[2][pter][2PTEL27‒], dup[4][qter][D4S2930++])(Figure 2). Parental karyotypes were normal.

After birth, the infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 50 days and received pleural and peritoneal drainages, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, parenteral nutrition with resolution of the hypoalbuminemia, levothyroxine, and intravenous antibiotics for central venous catheter infection. No drugs known to be associated with hypopigmentation of the hair, skin, or eyes were administered.

Two weeks after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit, the patient was referred to our department. Physical examination revealed silvery hair on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes. Abdominal, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic examination revealed no abnormalities, and no hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, nystagmus, or strabismus was noted.

Light microscopy of the hair revealed small and regular aggregates of melanin along the hair shaft, predominantly in the medulla (Figure 3). Light microscopy of a skin biopsy specimen showed normal pigmentation in the melanocytes and no giant melanosomes. The melanocyte count was within reference range. A peripheral blood smear showed no giant granules in the granulocytes. No treatment was administered and the patient was followed closely every month. When the patient returned for follow-up at 9 months of age, physical examination revealed brown hair on the head, eyebrows, and eyelashes, as well as normal pigmentation of the skin and eyes (Figure 4). Thyroid function was normal and no recurrent infections of any type were noted. At follow-up at the age of 4 years, he showed normal neurological and psychological development with brown hair, no recurrent infections, and normal thyroid function. Given that CHS, ES, and GS had been ruled out, the clinical presentation and the genetic mutation detected may indicate that this case represents a new entity characterized by transient silvery hair.

Comment

Silvery hair is a known feature of CHS, ES, and GS (Table). The characteristic hypopigmentation associated with these autosomal-recessive disorders is the result of impaired melanosome transport leading to failed transfer of melanin to keratinocytes. These disorders differ from oculocutaneous albinism in that melanin synthesis is unaffected.

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is characterized by generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, silvery hair, neurologic and immune dysfunction, lymphoproliferative disorders, and large granules in granulocytes and other cell types.1-3 A common complication of CHS is hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is characterized by fever, jaundice, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia.4 Pigmentary dilution of the irises also may be present, along with photophobia, strabismus, nystagmus, and impaired visual acuity. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is the result of a genetic defect in the lysosomal trafficking regulator gene, also known as CHS1 (located on chromosome 1q42.1‒q42.2).5 Melanin in the hair shaft is distributed uniformly in multiple small aggregates. Light microscopy of the skin typically shows giant melanosomes in melanocytes and aberrant keratinocyte maturation.

Elejalde syndrome is characterized by silvery hair (eyelashes and eyebrows), neurologic defects, and normal immunologic function.6,7 The underlying molecular basis remains unknown. It appears related to or allelic to GS type 1 and thus associated with mutations in MYO5A (myosin VA); however, the gene mutation responsible has yet to be defined.8 Light microscopy of the hair shaft usually shows an irregular distribution of large melanin aggregates, primarily in the medulla.9,10 Skin biopsy generally shows irregular distribution and irregular size of melanin granules in the basal layer.11 Leukocytes usually show no abnormal cytoplasmic granules. Ocular involvement is common and may present as nystagmus, diplopia, hypopigmented retinas, and/or papilledema.

In GS, hair microscopy generally reveals large aggregates of melanin pigment distributed irregularly along the hair shaft. Granulocytes typically show no giant granules. Light microscopy of the skin usually shows increased pigment in melanocytes with sparse pigment in keratinocytes. Griscelli syndrome is classified into 3 types.12 In GS type 1, patients have silvery gray hair, light-colored skin, severe neurologic defects,13 and normal immune status. This variant is caused by a mutation in the MYO5A gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 2, patients have silvery gray hair, pyogenic infections, an accelerated phase of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and variable neurologic defects in the absence of primary neurologic disease.14,15 This variant is caused by a mutation in the RAB27A (member RAS oncogene family) gene located on chromosome 15q21. In GS type 3, patients exhibit generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and hair with no abnormalities of the nervous or immune systems. There are 2 different mutations associated with GS type 3: the first is located on chromosome 2q37.3, causing a mutation in MLPH (melanophilin), and the second is caused by an F-exon deletion in the MYO5A gene.14

Our patient had silvery hair, generalized hypopigmentation of the skin and eyes, and normal central nervous system function with no other ocular involvement and no evidence of recurrent infections of any kind. Light microscopy showed small and regular melanin pigment aggregates in the hair shaft, which differs from the irregular pigment aggregates in GS and ES.

The regular melanin pigment aggregates observed along the hair shaft were consistent with CHS, but other manifestations of this syndrome were absent: ocular, neurologic, hematologic, and immunologic abnormalities with presence of giant intracytoplasmic granules in leukocytes, and giant melanosomes in melanocytes. In our patient, the absence of these features along with the spontaneous repigmentation of the silvery hair, improvement of thyroid function, reversal of hypoalbuminemia, and the chromosomopathy detected make a diagnosis of CHS highly improbable.

We concluded that the silvery hair noted in our patient resulted from the 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality. This mutation could affect some of the genes that control the trafficking of melanosomes or could induce hypothyroidism and hypoproteinemia associated with congenital hydrops fetalis (Figure 5).

Hydrops fetalis is a potentially fatal condition characterized by severe edema (swelling) in a fetus or neonate. There are 2 types of hydrops fetalis: immune and nonimmune. Immune hydrops fetalis may develop in an Rh+ fetus with an Rh– mother, as the mother’s immune cells begin to break down the red blood cells of the fetus, resulting in anemia in the fetus with subsequent fetal heart failure, leading to an accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the tissues and organs. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis can occur secondary to diseases that interfere with the fetus’s ability to manage fluid (eg, severe anemia; congenital infections; urinary, lymphatic, heart, or thoracic defects; inborn errors of metabolism; chromosomal abnormalities). Case studies have suggested that congenital hypothyroidism could be a cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis.16,17 Thyroid hormone deficiency reduces stimulation of adrenergic receptors in the lymphatic system and lungs, thereby decreasing lymph flow and protein efflux to the lymphatic system and decreasing clearance of liquid from the lungs. The final result is lymph vessel engorgement and subsequent leakage of lymphatic fluid to pleural spaces, causing hydrops fetalis and chylothorax.

The 46,XY,add(2)(p23) chromosomal abnormality has not been commonly associated with hypothyroidism and hydrops fetalis. The silvery hair in our patient was transient and spontaneously repigmented to brown over the course of follow-up in conjunction with improved physiologic changes. We concluded that the silvery hair in our patient was induced by his hypoproteinemic status secondary to hydrops fetalis and hypothyroidism.

Conclusion

In addition to CHS, ES, and GS, the differential diagnosis for silvery hair with abnormal skin pigmentation in children should include 46,XY,add(2)(p23) mutation, as was detected in our patient. Evaluation should include light microscopy of the hair shaft, skin biopsy, assessment of immune function, peripheral blood smear, and neurologic and eye examinations.

- White JG. The Chédiak-Higashi syndrome: a possible lysosomal disease. Blood. 1966;28:143-156.

- Introne W, Boissy RE, Gahl WA. Clinical, molecular, and cell biological aspects of Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68:283-303.

- Kaplan J, De Domenico I, Ward DM. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:22-29.

- Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [published online December 7, 2006]. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:95-109.

- Morrone K, Wang Y, Huizing M, et al. Two novel mutations identified in an African-American child with Chédiak-Higashi syndrome [published online March 24, 2010]. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:967535.

- Ivanovich J, Mallory S, Storer T, et al. 12-year-old male with Elejalde syndrome (neuroectodermal melanolysosomal disease). Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:313-316.

- Cahali JB, Fernandez SA, Oliveira ZN, et al. Elejalde syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:479-482.

- Bahadoran P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R, et al. Comment on Elejalde syndrome and relationship with Griscelli syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2003;116:408-409.

- Duran-McKinster C, Rodriguez-Jurado R, Ridaura C, et al. Elejalde syndrome—a melanolysosomal neurocutaneous syndrome: clinical and morphological findings in 7 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:182-186.

- Happle R. Neurocutaneous diseases. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:2131-2148.

- Sanal O, Yel L, Kucukali T, et al. An allelic variant of Griscelli disease: presentation with severe hypotonia, mental-motor retardation, and hypopigmentation consistent with Elejalde syndrome (neuroectodermal melanolysosomal disorder). J Neurol. 2000;247:570-572.

- Malhotra AK, Bhaskar G, Nanda M, et al. Griscelli syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:337-340.