User login

HL survivors have long-term risk of cardiovascular disease

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives, according to a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Previous research suggested that HL treatment is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

However, those studies did not determine how long the increased risk persists or pinpoint the risk factors for various cardiovascular diseases.

So Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, and her colleagues decided to investigate.

The team examined the risk for cardiovascular disease in HL survivors up to 40 years after they received treatment and compared that with the risk for cardiovascular disease in the general population. The researchers also studied treatment-related risk factors.

The study included 2524 Dutch patients who were diagnosed with HL when they were younger than 51 years of age. The patients’ median age was 27.3 years.

The patients were treated from 1965 through 1995 and had survived for at least 5 years after diagnosis. In all, 2052 patients (81.3%) had received mediastinal radiotherapy, and 773 (30.6%) had received chemotherapy containing an anthracycline.

At a median of 20.3 years of follow-up, there were 1713 cardiovascular events in 797 patients (31.6%), and 410 of those patients (51.4%) had experienced 2 events or more.

The most frequently occurring cardiovascular disease was coronary heart disease (CHD), with 401 patients developing it as their first event. This was followed by valvular heart disease (VHD, 374 events) and heart failure (HF, 140 events).

HL survivors had a 3.2-fold increased risk of developing CHD and a 6.8-fold increased risk of developing HF compared to the general population.

HL survivors who had been treated before age 25 had a 4.6-fold to 7.5-fold increased risk of CHD and a 10.9-fold to 40.5-fold increased risk of HF, depending on the age they ultimately attained.

HL survivors treated at 35 to 50 years of age had a 2.0-fold to 2.3-fold increased risk of CHD and a 3.1-fold to 5.2-fold increased risk of HF, depending on their attained age.

The risks of CHD and HF remained significantly increased beyond 35 years after HL treatment. The standardized incidence ratios were 3.9 and 5.8, respectively.

The median times between HL treatment and first cardiovascular disease events were 18 years for CHD, 24 years for VHD, and 19 years for HF.

The cumulative risk of any type of cardiovascular disease was 50% at 40 years after HL diagnosis. For patients who were treated for HL before they were 25, the cumulative risk of developing a cardiovascular disease at 60 years of age or older was 20% for CHD, 31% for VHD, and 11% for HF.

The study also suggested that mediastinal radiotherapy increased the risk of CHD, VHD, and HF. But anthracycline-containing chemotherapy only increased the risk of VHD and HF.

Dr van Leeuwen and her colleagues concluded that both physicians and patients should be aware that HL survivors have a persistently increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives. The team also believes the results of their study may direct guidelines for follow-up in HL survivors.

A commentary related to this research is available in JAMA Internal Medicine as well. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives, according to a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Previous research suggested that HL treatment is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

However, those studies did not determine how long the increased risk persists or pinpoint the risk factors for various cardiovascular diseases.

So Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, and her colleagues decided to investigate.

The team examined the risk for cardiovascular disease in HL survivors up to 40 years after they received treatment and compared that with the risk for cardiovascular disease in the general population. The researchers also studied treatment-related risk factors.

The study included 2524 Dutch patients who were diagnosed with HL when they were younger than 51 years of age. The patients’ median age was 27.3 years.

The patients were treated from 1965 through 1995 and had survived for at least 5 years after diagnosis. In all, 2052 patients (81.3%) had received mediastinal radiotherapy, and 773 (30.6%) had received chemotherapy containing an anthracycline.

At a median of 20.3 years of follow-up, there were 1713 cardiovascular events in 797 patients (31.6%), and 410 of those patients (51.4%) had experienced 2 events or more.

The most frequently occurring cardiovascular disease was coronary heart disease (CHD), with 401 patients developing it as their first event. This was followed by valvular heart disease (VHD, 374 events) and heart failure (HF, 140 events).

HL survivors had a 3.2-fold increased risk of developing CHD and a 6.8-fold increased risk of developing HF compared to the general population.

HL survivors who had been treated before age 25 had a 4.6-fold to 7.5-fold increased risk of CHD and a 10.9-fold to 40.5-fold increased risk of HF, depending on the age they ultimately attained.

HL survivors treated at 35 to 50 years of age had a 2.0-fold to 2.3-fold increased risk of CHD and a 3.1-fold to 5.2-fold increased risk of HF, depending on their attained age.

The risks of CHD and HF remained significantly increased beyond 35 years after HL treatment. The standardized incidence ratios were 3.9 and 5.8, respectively.

The median times between HL treatment and first cardiovascular disease events were 18 years for CHD, 24 years for VHD, and 19 years for HF.

The cumulative risk of any type of cardiovascular disease was 50% at 40 years after HL diagnosis. For patients who were treated for HL before they were 25, the cumulative risk of developing a cardiovascular disease at 60 years of age or older was 20% for CHD, 31% for VHD, and 11% for HF.

The study also suggested that mediastinal radiotherapy increased the risk of CHD, VHD, and HF. But anthracycline-containing chemotherapy only increased the risk of VHD and HF.

Dr van Leeuwen and her colleagues concluded that both physicians and patients should be aware that HL survivors have a persistently increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives. The team also believes the results of their study may direct guidelines for follow-up in HL survivors.

A commentary related to this research is available in JAMA Internal Medicine as well. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives, according to a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Previous research suggested that HL treatment is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases.

However, those studies did not determine how long the increased risk persists or pinpoint the risk factors for various cardiovascular diseases.

So Flora E. van Leeuwen, PhD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, and her colleagues decided to investigate.

The team examined the risk for cardiovascular disease in HL survivors up to 40 years after they received treatment and compared that with the risk for cardiovascular disease in the general population. The researchers also studied treatment-related risk factors.

The study included 2524 Dutch patients who were diagnosed with HL when they were younger than 51 years of age. The patients’ median age was 27.3 years.

The patients were treated from 1965 through 1995 and had survived for at least 5 years after diagnosis. In all, 2052 patients (81.3%) had received mediastinal radiotherapy, and 773 (30.6%) had received chemotherapy containing an anthracycline.

At a median of 20.3 years of follow-up, there were 1713 cardiovascular events in 797 patients (31.6%), and 410 of those patients (51.4%) had experienced 2 events or more.

The most frequently occurring cardiovascular disease was coronary heart disease (CHD), with 401 patients developing it as their first event. This was followed by valvular heart disease (VHD, 374 events) and heart failure (HF, 140 events).

HL survivors had a 3.2-fold increased risk of developing CHD and a 6.8-fold increased risk of developing HF compared to the general population.

HL survivors who had been treated before age 25 had a 4.6-fold to 7.5-fold increased risk of CHD and a 10.9-fold to 40.5-fold increased risk of HF, depending on the age they ultimately attained.

HL survivors treated at 35 to 50 years of age had a 2.0-fold to 2.3-fold increased risk of CHD and a 3.1-fold to 5.2-fold increased risk of HF, depending on their attained age.

The risks of CHD and HF remained significantly increased beyond 35 years after HL treatment. The standardized incidence ratios were 3.9 and 5.8, respectively.

The median times between HL treatment and first cardiovascular disease events were 18 years for CHD, 24 years for VHD, and 19 years for HF.

The cumulative risk of any type of cardiovascular disease was 50% at 40 years after HL diagnosis. For patients who were treated for HL before they were 25, the cumulative risk of developing a cardiovascular disease at 60 years of age or older was 20% for CHD, 31% for VHD, and 11% for HF.

The study also suggested that mediastinal radiotherapy increased the risk of CHD, VHD, and HF. But anthracycline-containing chemotherapy only increased the risk of VHD and HF.

Dr van Leeuwen and her colleagues concluded that both physicians and patients should be aware that HL survivors have a persistently increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases throughout their lives. The team also believes the results of their study may direct guidelines for follow-up in HL survivors.

A commentary related to this research is available in JAMA Internal Medicine as well. ![]()

MM drug met accelerated approval requirements

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Celgene Corporation has fulfilled the requirements for accelerated approval of pomalidomide (Pomalyst) in the US, based on results from the phase 3 MM-003 trial.

The trial showed that pomalidomide in combination with dexamethasone can improve survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple

myeloma (MM).

A drug can be granted accelerated approval in the US based on a surrogate endpoint thought to predict clinical benefit.

To retain approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the drug must demonstrate an actual clinical benefit.

In 2013, the FDA granted pomalidomide accelerated approval for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 2 prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and have demonstrated disease progression on or within 60 days of completing their last therapy.

The FDA’s approval was based on results from a phase 2 trial known as MM-002. The trial showed that pomalidomide plus dexamethasone can improve the overall response rate in relapsed/refractory MM patients when compared to pomalidomide alone.

About 29% of patients in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm achieved a partial response or better, compared to about 7% of patients in the pomalidomide-alone arm.

Now, results of the MM-003 trial have shown that pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival and overall survival in relapsed/refractory MM patients, when compared to high-dose dexamethasone alone.

The median progression-free survival was 3.6 months in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm and 1.8 months in the dexamethasone arm (P<0.001). And the median overall survival was 12.4 months and 8 months, respectively (P=0.009).

These outcomes suggest pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, provides a clinical benefit for previously treated MM patients, which fulfills the requirements for accelerated approval. So the drug’s label has been updated to reflect his change.

For more details on pomalidomide, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Celgene Corporation has fulfilled the requirements for accelerated approval of pomalidomide (Pomalyst) in the US, based on results from the phase 3 MM-003 trial.

The trial showed that pomalidomide in combination with dexamethasone can improve survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple

myeloma (MM).

A drug can be granted accelerated approval in the US based on a surrogate endpoint thought to predict clinical benefit.

To retain approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the drug must demonstrate an actual clinical benefit.

In 2013, the FDA granted pomalidomide accelerated approval for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 2 prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and have demonstrated disease progression on or within 60 days of completing their last therapy.

The FDA’s approval was based on results from a phase 2 trial known as MM-002. The trial showed that pomalidomide plus dexamethasone can improve the overall response rate in relapsed/refractory MM patients when compared to pomalidomide alone.

About 29% of patients in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm achieved a partial response or better, compared to about 7% of patients in the pomalidomide-alone arm.

Now, results of the MM-003 trial have shown that pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival and overall survival in relapsed/refractory MM patients, when compared to high-dose dexamethasone alone.

The median progression-free survival was 3.6 months in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm and 1.8 months in the dexamethasone arm (P<0.001). And the median overall survival was 12.4 months and 8 months, respectively (P=0.009).

These outcomes suggest pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, provides a clinical benefit for previously treated MM patients, which fulfills the requirements for accelerated approval. So the drug’s label has been updated to reflect his change.

For more details on pomalidomide, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Celgene Corporation has fulfilled the requirements for accelerated approval of pomalidomide (Pomalyst) in the US, based on results from the phase 3 MM-003 trial.

The trial showed that pomalidomide in combination with dexamethasone can improve survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple

myeloma (MM).

A drug can be granted accelerated approval in the US based on a surrogate endpoint thought to predict clinical benefit.

To retain approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the drug must demonstrate an actual clinical benefit.

In 2013, the FDA granted pomalidomide accelerated approval for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 2 prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor, and have demonstrated disease progression on or within 60 days of completing their last therapy.

The FDA’s approval was based on results from a phase 2 trial known as MM-002. The trial showed that pomalidomide plus dexamethasone can improve the overall response rate in relapsed/refractory MM patients when compared to pomalidomide alone.

About 29% of patients in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm achieved a partial response or better, compared to about 7% of patients in the pomalidomide-alone arm.

Now, results of the MM-003 trial have shown that pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone can improve progression-free survival and overall survival in relapsed/refractory MM patients, when compared to high-dose dexamethasone alone.

The median progression-free survival was 3.6 months in the pomalidomide-dexamethasone arm and 1.8 months in the dexamethasone arm (P<0.001). And the median overall survival was 12.4 months and 8 months, respectively (P=0.009).

These outcomes suggest pomalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, provides a clinical benefit for previously treated MM patients, which fulfills the requirements for accelerated approval. So the drug’s label has been updated to reflect his change.

For more details on pomalidomide, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

TCS Among Children with Pneumonia

National guidelines for the management of childhood pneumonia highlight the need for the development of objective outcome measures to inform clinical decision making, establish benchmarks of care, and compare treatments and interventions.[1] Time to clinical stability (TCS) is a measure reported in adult pneumonia studies that incorporates vital signs, ability to eat, and mental status to objectively assess readiness for discharge.[2, 3, 4] TCS has not been validated among children as it has in adults,[5, 6, 7, 8] although such measures could prove useful for assessing discharge readiness with applications in both clinical and research settings. The objective of our study was to test the performance of pediatric TCS measures among children hospitalized with pneumonia.

METHODS

Study Population

We studied children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia at Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt between January 6, 2010 and May 9, 2011. Study children were enrolled as part of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study, a prospective, population‐based study of community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations. Detailed enrollment criteria for the EPIC study were reported previously.[9] Institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University and the CDC approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from enrolled families.

Data Elements and Study Definitions

Baseline data, including demographics, illness history, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes (eg, length of stay [LOS], intensive care admission), were systematically and prospectively collected. Additionally, data for 4 physiologic parameters, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and use of supplemental oxygen were obtained from the electronic medical record. These parameters were measured at least every 6 hours from admission through discharge as part of routine care. Readmissions within 7 calendar days of discharge were also obtained from the electronic medical record.

Stability for each parameter was defined as follows: normal temperature (36.037.9C), normal respiratory and heart rates in accordance with Pediatric Advanced Life Support age‐based values (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article),[10] and no administration of supplemental oxygen. If the last recorded value for a given parameter was abnormal, that parameter was considered unstable at discharge. Otherwise, the time and date of the last abnormal value for each parameter was subtracted from admission time and date to determine TCS for that parameter in hours.

To determine overall stability, we evaluated 4 combination TCS measures, each incorporating 2 individual parameters. All combinations included respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, as these parameters are the most explicit clinical indicators of pneumonia. Stability for each combination measure was defined as normalization of all included measures.

Clinical Outcomes for the Combined TCS Measures

The 4 combined TCS measures were compared against clinical outcomes including hospital LOS (measured in hours) and an ordinal severity scale. The ordinal scale categorized children into 3 mutually exclusive groups as follows: nonsevere (hospitalization without need for intensive care or empyema requiring drainage), severe (intensive care admission without invasive mechanical ventilation or vasopressor support and no empyema requiring drainage), and very severe (invasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, or empyema requiring drainage).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages and median and interquartile range (IQR) values, respectively. Analyses were stratified by age (2 years, 24 years, 517 years). We also plotted summary statistics for the combined measures and LOS, and computed the median absolute difference between these measures for each level of the ordinal severity scale. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 336 children enrolled in the EPIC study at Vanderbilt during the study period, 334 (99.4%) with complete data were included. Median age was 33 months (IQR, 1480). Median LOS was 56.4 hours (IQR, 41.591.7). There were 249 (74.5%) children classified as nonsevere, 39 (11.7) as severe, and 46 (13.8) as very severe (for age‐based characteristics see Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article). Overall, 12 (3.6%) children were readmitted within 7 days of discharge.

Individual Stability Parameters

Overall, 323 (96.7%) children had 1 parameter abnormal on admission. Respiratory rate (81.4%) was the most common abnormal parameter, followed by abnormal temperature (71.4%), use of supplemental oxygen (63.8%), and abnormal heart rate (54.4%). Overall, use of supplemental oxygen had the longest TCS, followed by respiratory rate (Table 1). In comparison, heart rate and temperature stabilized relatively quickly.

| Parameter | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | |

| ||||||

| Respiratory rate | 97 (74.6) | 38.6 (18.768.9) | 63 (70.0) | 31.6 (9.561.9) | 63 (62.4) | 24.3 (10.859.2) |

| Oxygen | 90 (69.2) | 39.5 (19.273.6) | 58 (64.4) | 44.2 (2477.6) | 61 (60.4) | 38.3 (1870.6) |

| Heart rate | 21 (16.2) | 4.5 (0.318.4) | 73 (81.1) | 21.8 (5.751.9) | 62 (61.4) | 18 (5.842.2) |

| Temperature | 101 (77.7) | 14.5 (4.545.3) | 61 (67.8) | 18.4 (2.842.8) | 62 (61.4) | 10.6 (0.834) |

Seventy children (21.0%) had 1 parameter abnormal at discharge, including abnormal respiratory rate in 13.7%, heart rate in 7.0%, and temperature in 3.3%. One child (0.3%) was discharged with supplemental oxygen. Ten children (3.0%) had 2 parameters abnormal at discharge. There was no difference in 7‐day readmissions for children with 1 parameter abnormal at discharge (1.4%) compared to those with no abnormal parameters at discharge (4.4%, P=0.253).

Combination TCS Measures

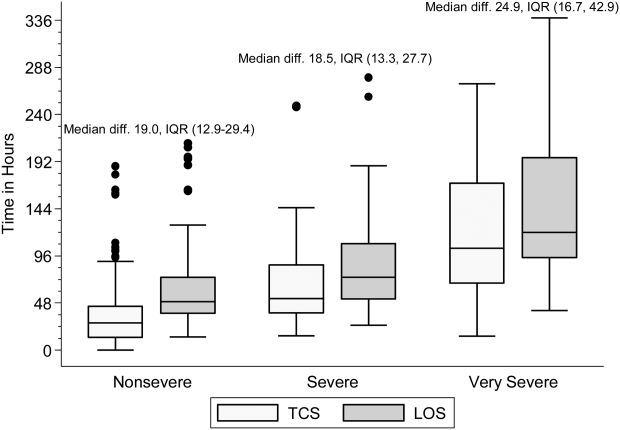

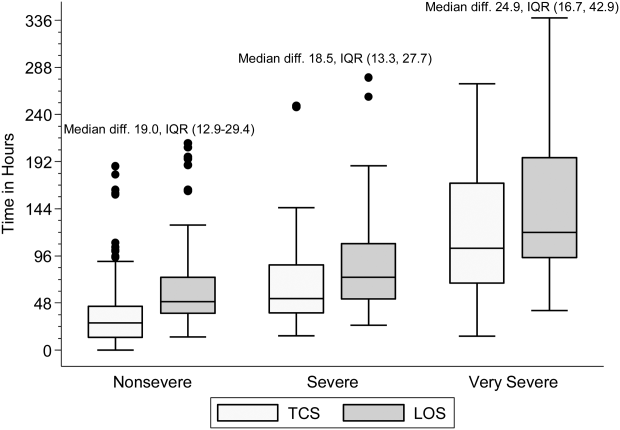

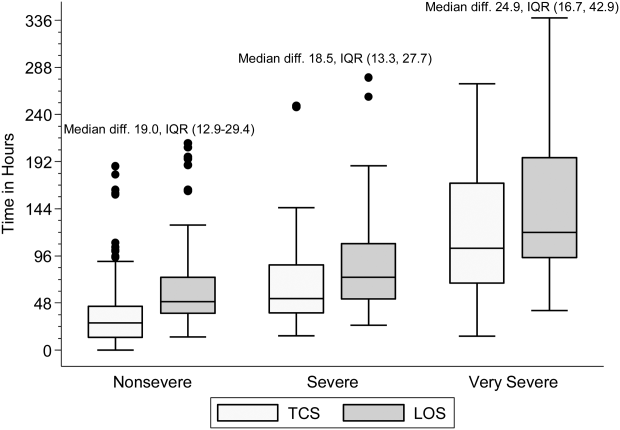

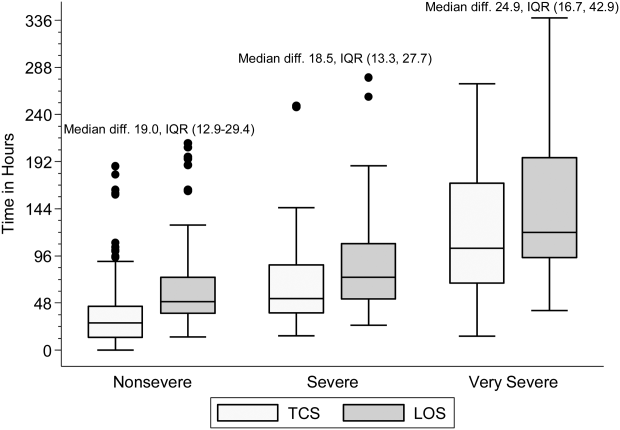

Within each age group, the percentage of children achieving stability was relatively consistent across the 4 combined TCS measures (Table 2); however, more children were considered unstable at discharge (and fewer classified as stable on admission) as the number of included parameters increased. More children 5 years of age reached stability (range, 80.0%85.6%) compared to children 5 years of age (range, 68.3%72.3%). We also noted increasing median TCS with increasing disease severity (Figure 1, P0.01) (see Supporting Fig. 1AC in the online version of this article); TCS was only slightly shorter than LOS across all 3 levels of the severity scale.

| TCS Measures | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | ||

| |||||||

| RR+O2 | 108 (83.1) | 40.5 (20.175.0) | 72 (80.0) | 39.6 (15.679.2) | 69 (68.3) | 30.4 (14.759.2) | 0.08 |

| RR+O2+HR | 109 (83.8) | 40.2 (19.573.9) | 73 (81.1) | 35.9 (15.977.6) | 68 (67.3) | 29.8 (17.256.6) | 0.11 |

| RR+O2+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 77 (85.6) | 39.1 (18.477.6) | 73 (72.3) | 28.2 (14.744.7) | 0.03 |

| RR+O2+HR+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 72 (80.0) | 39.7 (20.177.5) | 71 (70.3) | 29.2 (18.254) | 0.05 |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that longitudinal TCS measures consisting of routinely collected physiologic parameters may be useful for objectively assessing disease recovery and clinical readiness for discharge among children hospitalized with pneumonia. A simple TCS measure incorporating respiratory rate and oxygen requirement performed similarly to the more complex combinations and classified fewer children as unstable at discharge. However, we also note several challenges that deserve additional study prior to the application of a pediatric TCS measure in clinical and research settings.

Vital signs and supplemental oxygen use are used clinically to assess disease severity and response to therapy among children with acute respiratory illness. Because these objective parameters are routinely collected among hospitalized children, the systematization of these data could inform clinical decision making around hospital discharge. Similar to early warning scores used to detect impending clinical deterioration,[11] TCS measures, by signaling normalization of stability parameters in a consistent and objective manner, could serve as an early signal of readiness for discharge. However, maximizing the clinical utility of TCS would require embedding the process within the electronic health record, a tool that could also have implications for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' meaningful use regulations.[12]

TCS could also serve as an outcome measure in research and quality efforts. Increased disease severity was associated with longer TCS for the 4 combined measures; TCS also demonstrated strong agreement with LOS. Furthermore, TCS minimizes the influence of factors unrelated to disease that may impact LOS (eg, frequency of hospital rounds, transportation difficulties, or social impediments to discharge), an advantage when studying outcomes for research and quality benchmarking.

The percentage of children reaching stability and the median TCS for the combined measures demonstrated little variation within each age group, likely because respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, 2 of the parameters with the longest individual time to stability, were also included in each of the combination measures. This suggests that less‐complex measures incorporating only respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen may be sufficient to assess clinical stability, particularly because these parameters are objectively measured and possess a direct physiological link to pneumonia. In contrast, the other parameters may be more often influenced by factors unrelated to disease severity.

Our study also highlights several shortcomings of the pediatric TCS measures. Despite use of published, age‐based reference values,[13] we noted wide variation in the achievement of stability across individual parameters, especially for children 5 years old. Overall, 21% of children had 1 abnormal parameter at discharge. Even the simplest combined measure classified 13.4% of children as unstable at discharge. Discharge with unstable parameters was not associated with 7‐day readmission, although our study was underpowered to detect small differences. Additional study is therefore needed to evaluate less restrictive cutoff values on calculated TCS and the impact of hospital discharge prior to reaching stability. In particular, relaxing the upper limit for normal respiratory rate in adolescents (16 breaths per minute) to more closely approximate the adult TCS parameter (24 breaths per minute) should be explored. Refinement and standardization of age‐based vital sign reference values specific to hospitalized children may also improve the performance of these measures.[14]

Several limitations deserve discussion. TCS parameters and readmission data were abstracted retrospectively from a single institution, and our findings may not be generalizable. Although clinical staff routinely measured these data, measurement variation likely exists. Nevertheless, such variation is likely systematic, limiting the impact of potential misclassification. TCS was calculated based on the last abnormal value for each parameter; prior fluctuations between normal and abnormal periods of stability were not captured. We were unable to assess room air oxygen saturations. Instead, supplemental oxygen use served as a surrogate for hypoxia. At our institution, oxygen therapy is provided for children with pneumonia to maintain oxygen saturations of 90% to 92%. We did not assess work of breathing (a marker of severe pneumonia) or ability to eat (a component of adult TCS measures). We initially considered the evaluation of intravenous fluids as a proxy for ability to eat (addition of this parameter to the 4 parameter TCS resulted in a modest increase in median time to stability, data not shown); however, we felt the lack of institutional policy and subjective nature of this parameter detracted from our study's objectives. Finally, we were not able to determine clinical readiness for discharge beyond the measurement of vital sign parameters. Therefore, prospective evaluation of the proposed pediatric TCS measures in broader populations will be important to build upon our findings, refine stability parameters, and test the utility of new parameters (eg, ability to eat, work of breathing) prior to use in clinical settings.

Our study provides an initial evaluation of TCS measures for assessing severity and recovery among children hospitalized with pneumonia. Similar to adults, such validated TCS measures may ultimately prove useful for improving the quality of both clinical care and research, although additional study to more clearly define stability criteria is needed prior to implementation.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AI104779 to Dr. Williams. The EPIC study was supported by the Influenza Division in the National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through cooperative agreements with each study site and was based on a competitive research funding opportunity. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grijalva serves as a consultant to Glaxo‐Smith‐Kline and Pfizer outside of the scope of this article. Dr. Edwards is supported through grants from Novartis for the conduction of a Group B strep vaccine study and serves as the Chair of the Data Safety and Monitoring Data Committee for Influenza Study outside the scope of this article. Dr. Self reports grants from CareFusion, BioMerieux, Affinium Pharmaceuticals, Astute Medical, Crucell Holland BV, BRAHMS GmbH, Pfizer, Rapid Pathogen Screening, Venaxis, BioAegis Inc., Sphingotec GmbH, and Cempra Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from BioFire Diagnostics and Venaxis, Inc; and patent 13/632,874 (Sterile Blood Culture Collection System) pending; all outside the scope of this article.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/index.html. Accessed February 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–1457.

- , , , et al.; Neumofail Group. Reaching stability in community‐acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783–1790.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization. The pneumonia severity index predicts time to clinical stability in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:739–743.

- , , , , . Efficacy of corticosteroids in community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomized double‐blinded clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:975–982.

- , , , et al. Early administration of antibiotics does not shorten time to clinical stability in patients with moderate‐to‐severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1798–1804.

- , , , . A comparison between time to clinical stability in community‐acquired aspiration pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9:143–150.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. A worldwide perspective of atypical pathogens in community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1086–1093.

- , , , et al.; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835–845.

- American Heart Association. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e989–e1004.

- , , . Development and initial validation of the Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System score. Crit Care. 2009;13:R135.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Regulations and guidance. EHR incentive programs. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations‐and‐Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html. Accessed February 20, 2015

- , , , , , . Development of heart and respiratory rate percentile curves for hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1150–e1157.

- , , , et al. Length of stay after reaching clinical stability drives hospital costs associated with adult community‐acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:219–226.

National guidelines for the management of childhood pneumonia highlight the need for the development of objective outcome measures to inform clinical decision making, establish benchmarks of care, and compare treatments and interventions.[1] Time to clinical stability (TCS) is a measure reported in adult pneumonia studies that incorporates vital signs, ability to eat, and mental status to objectively assess readiness for discharge.[2, 3, 4] TCS has not been validated among children as it has in adults,[5, 6, 7, 8] although such measures could prove useful for assessing discharge readiness with applications in both clinical and research settings. The objective of our study was to test the performance of pediatric TCS measures among children hospitalized with pneumonia.

METHODS

Study Population

We studied children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia at Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt between January 6, 2010 and May 9, 2011. Study children were enrolled as part of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study, a prospective, population‐based study of community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations. Detailed enrollment criteria for the EPIC study were reported previously.[9] Institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University and the CDC approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from enrolled families.

Data Elements and Study Definitions

Baseline data, including demographics, illness history, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes (eg, length of stay [LOS], intensive care admission), were systematically and prospectively collected. Additionally, data for 4 physiologic parameters, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and use of supplemental oxygen were obtained from the electronic medical record. These parameters were measured at least every 6 hours from admission through discharge as part of routine care. Readmissions within 7 calendar days of discharge were also obtained from the electronic medical record.

Stability for each parameter was defined as follows: normal temperature (36.037.9C), normal respiratory and heart rates in accordance with Pediatric Advanced Life Support age‐based values (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article),[10] and no administration of supplemental oxygen. If the last recorded value for a given parameter was abnormal, that parameter was considered unstable at discharge. Otherwise, the time and date of the last abnormal value for each parameter was subtracted from admission time and date to determine TCS for that parameter in hours.

To determine overall stability, we evaluated 4 combination TCS measures, each incorporating 2 individual parameters. All combinations included respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, as these parameters are the most explicit clinical indicators of pneumonia. Stability for each combination measure was defined as normalization of all included measures.

Clinical Outcomes for the Combined TCS Measures

The 4 combined TCS measures were compared against clinical outcomes including hospital LOS (measured in hours) and an ordinal severity scale. The ordinal scale categorized children into 3 mutually exclusive groups as follows: nonsevere (hospitalization without need for intensive care or empyema requiring drainage), severe (intensive care admission without invasive mechanical ventilation or vasopressor support and no empyema requiring drainage), and very severe (invasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, or empyema requiring drainage).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages and median and interquartile range (IQR) values, respectively. Analyses were stratified by age (2 years, 24 years, 517 years). We also plotted summary statistics for the combined measures and LOS, and computed the median absolute difference between these measures for each level of the ordinal severity scale. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 336 children enrolled in the EPIC study at Vanderbilt during the study period, 334 (99.4%) with complete data were included. Median age was 33 months (IQR, 1480). Median LOS was 56.4 hours (IQR, 41.591.7). There were 249 (74.5%) children classified as nonsevere, 39 (11.7) as severe, and 46 (13.8) as very severe (for age‐based characteristics see Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article). Overall, 12 (3.6%) children were readmitted within 7 days of discharge.

Individual Stability Parameters

Overall, 323 (96.7%) children had 1 parameter abnormal on admission. Respiratory rate (81.4%) was the most common abnormal parameter, followed by abnormal temperature (71.4%), use of supplemental oxygen (63.8%), and abnormal heart rate (54.4%). Overall, use of supplemental oxygen had the longest TCS, followed by respiratory rate (Table 1). In comparison, heart rate and temperature stabilized relatively quickly.

| Parameter | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | |

| ||||||

| Respiratory rate | 97 (74.6) | 38.6 (18.768.9) | 63 (70.0) | 31.6 (9.561.9) | 63 (62.4) | 24.3 (10.859.2) |

| Oxygen | 90 (69.2) | 39.5 (19.273.6) | 58 (64.4) | 44.2 (2477.6) | 61 (60.4) | 38.3 (1870.6) |

| Heart rate | 21 (16.2) | 4.5 (0.318.4) | 73 (81.1) | 21.8 (5.751.9) | 62 (61.4) | 18 (5.842.2) |

| Temperature | 101 (77.7) | 14.5 (4.545.3) | 61 (67.8) | 18.4 (2.842.8) | 62 (61.4) | 10.6 (0.834) |

Seventy children (21.0%) had 1 parameter abnormal at discharge, including abnormal respiratory rate in 13.7%, heart rate in 7.0%, and temperature in 3.3%. One child (0.3%) was discharged with supplemental oxygen. Ten children (3.0%) had 2 parameters abnormal at discharge. There was no difference in 7‐day readmissions for children with 1 parameter abnormal at discharge (1.4%) compared to those with no abnormal parameters at discharge (4.4%, P=0.253).

Combination TCS Measures

Within each age group, the percentage of children achieving stability was relatively consistent across the 4 combined TCS measures (Table 2); however, more children were considered unstable at discharge (and fewer classified as stable on admission) as the number of included parameters increased. More children 5 years of age reached stability (range, 80.0%85.6%) compared to children 5 years of age (range, 68.3%72.3%). We also noted increasing median TCS with increasing disease severity (Figure 1, P0.01) (see Supporting Fig. 1AC in the online version of this article); TCS was only slightly shorter than LOS across all 3 levels of the severity scale.

| TCS Measures | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | ||

| |||||||

| RR+O2 | 108 (83.1) | 40.5 (20.175.0) | 72 (80.0) | 39.6 (15.679.2) | 69 (68.3) | 30.4 (14.759.2) | 0.08 |

| RR+O2+HR | 109 (83.8) | 40.2 (19.573.9) | 73 (81.1) | 35.9 (15.977.6) | 68 (67.3) | 29.8 (17.256.6) | 0.11 |

| RR+O2+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 77 (85.6) | 39.1 (18.477.6) | 73 (72.3) | 28.2 (14.744.7) | 0.03 |

| RR+O2+HR+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 72 (80.0) | 39.7 (20.177.5) | 71 (70.3) | 29.2 (18.254) | 0.05 |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that longitudinal TCS measures consisting of routinely collected physiologic parameters may be useful for objectively assessing disease recovery and clinical readiness for discharge among children hospitalized with pneumonia. A simple TCS measure incorporating respiratory rate and oxygen requirement performed similarly to the more complex combinations and classified fewer children as unstable at discharge. However, we also note several challenges that deserve additional study prior to the application of a pediatric TCS measure in clinical and research settings.

Vital signs and supplemental oxygen use are used clinically to assess disease severity and response to therapy among children with acute respiratory illness. Because these objective parameters are routinely collected among hospitalized children, the systematization of these data could inform clinical decision making around hospital discharge. Similar to early warning scores used to detect impending clinical deterioration,[11] TCS measures, by signaling normalization of stability parameters in a consistent and objective manner, could serve as an early signal of readiness for discharge. However, maximizing the clinical utility of TCS would require embedding the process within the electronic health record, a tool that could also have implications for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' meaningful use regulations.[12]

TCS could also serve as an outcome measure in research and quality efforts. Increased disease severity was associated with longer TCS for the 4 combined measures; TCS also demonstrated strong agreement with LOS. Furthermore, TCS minimizes the influence of factors unrelated to disease that may impact LOS (eg, frequency of hospital rounds, transportation difficulties, or social impediments to discharge), an advantage when studying outcomes for research and quality benchmarking.

The percentage of children reaching stability and the median TCS for the combined measures demonstrated little variation within each age group, likely because respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, 2 of the parameters with the longest individual time to stability, were also included in each of the combination measures. This suggests that less‐complex measures incorporating only respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen may be sufficient to assess clinical stability, particularly because these parameters are objectively measured and possess a direct physiological link to pneumonia. In contrast, the other parameters may be more often influenced by factors unrelated to disease severity.

Our study also highlights several shortcomings of the pediatric TCS measures. Despite use of published, age‐based reference values,[13] we noted wide variation in the achievement of stability across individual parameters, especially for children 5 years old. Overall, 21% of children had 1 abnormal parameter at discharge. Even the simplest combined measure classified 13.4% of children as unstable at discharge. Discharge with unstable parameters was not associated with 7‐day readmission, although our study was underpowered to detect small differences. Additional study is therefore needed to evaluate less restrictive cutoff values on calculated TCS and the impact of hospital discharge prior to reaching stability. In particular, relaxing the upper limit for normal respiratory rate in adolescents (16 breaths per minute) to more closely approximate the adult TCS parameter (24 breaths per minute) should be explored. Refinement and standardization of age‐based vital sign reference values specific to hospitalized children may also improve the performance of these measures.[14]

Several limitations deserve discussion. TCS parameters and readmission data were abstracted retrospectively from a single institution, and our findings may not be generalizable. Although clinical staff routinely measured these data, measurement variation likely exists. Nevertheless, such variation is likely systematic, limiting the impact of potential misclassification. TCS was calculated based on the last abnormal value for each parameter; prior fluctuations between normal and abnormal periods of stability were not captured. We were unable to assess room air oxygen saturations. Instead, supplemental oxygen use served as a surrogate for hypoxia. At our institution, oxygen therapy is provided for children with pneumonia to maintain oxygen saturations of 90% to 92%. We did not assess work of breathing (a marker of severe pneumonia) or ability to eat (a component of adult TCS measures). We initially considered the evaluation of intravenous fluids as a proxy for ability to eat (addition of this parameter to the 4 parameter TCS resulted in a modest increase in median time to stability, data not shown); however, we felt the lack of institutional policy and subjective nature of this parameter detracted from our study's objectives. Finally, we were not able to determine clinical readiness for discharge beyond the measurement of vital sign parameters. Therefore, prospective evaluation of the proposed pediatric TCS measures in broader populations will be important to build upon our findings, refine stability parameters, and test the utility of new parameters (eg, ability to eat, work of breathing) prior to use in clinical settings.

Our study provides an initial evaluation of TCS measures for assessing severity and recovery among children hospitalized with pneumonia. Similar to adults, such validated TCS measures may ultimately prove useful for improving the quality of both clinical care and research, although additional study to more clearly define stability criteria is needed prior to implementation.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AI104779 to Dr. Williams. The EPIC study was supported by the Influenza Division in the National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through cooperative agreements with each study site and was based on a competitive research funding opportunity. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grijalva serves as a consultant to Glaxo‐Smith‐Kline and Pfizer outside of the scope of this article. Dr. Edwards is supported through grants from Novartis for the conduction of a Group B strep vaccine study and serves as the Chair of the Data Safety and Monitoring Data Committee for Influenza Study outside the scope of this article. Dr. Self reports grants from CareFusion, BioMerieux, Affinium Pharmaceuticals, Astute Medical, Crucell Holland BV, BRAHMS GmbH, Pfizer, Rapid Pathogen Screening, Venaxis, BioAegis Inc., Sphingotec GmbH, and Cempra Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from BioFire Diagnostics and Venaxis, Inc; and patent 13/632,874 (Sterile Blood Culture Collection System) pending; all outside the scope of this article.

National guidelines for the management of childhood pneumonia highlight the need for the development of objective outcome measures to inform clinical decision making, establish benchmarks of care, and compare treatments and interventions.[1] Time to clinical stability (TCS) is a measure reported in adult pneumonia studies that incorporates vital signs, ability to eat, and mental status to objectively assess readiness for discharge.[2, 3, 4] TCS has not been validated among children as it has in adults,[5, 6, 7, 8] although such measures could prove useful for assessing discharge readiness with applications in both clinical and research settings. The objective of our study was to test the performance of pediatric TCS measures among children hospitalized with pneumonia.

METHODS

Study Population

We studied children hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia at Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt between January 6, 2010 and May 9, 2011. Study children were enrolled as part of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study, a prospective, population‐based study of community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations. Detailed enrollment criteria for the EPIC study were reported previously.[9] Institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University and the CDC approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from enrolled families.

Data Elements and Study Definitions

Baseline data, including demographics, illness history, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes (eg, length of stay [LOS], intensive care admission), were systematically and prospectively collected. Additionally, data for 4 physiologic parameters, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and use of supplemental oxygen were obtained from the electronic medical record. These parameters were measured at least every 6 hours from admission through discharge as part of routine care. Readmissions within 7 calendar days of discharge were also obtained from the electronic medical record.

Stability for each parameter was defined as follows: normal temperature (36.037.9C), normal respiratory and heart rates in accordance with Pediatric Advanced Life Support age‐based values (see Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article),[10] and no administration of supplemental oxygen. If the last recorded value for a given parameter was abnormal, that parameter was considered unstable at discharge. Otherwise, the time and date of the last abnormal value for each parameter was subtracted from admission time and date to determine TCS for that parameter in hours.

To determine overall stability, we evaluated 4 combination TCS measures, each incorporating 2 individual parameters. All combinations included respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, as these parameters are the most explicit clinical indicators of pneumonia. Stability for each combination measure was defined as normalization of all included measures.

Clinical Outcomes for the Combined TCS Measures

The 4 combined TCS measures were compared against clinical outcomes including hospital LOS (measured in hours) and an ordinal severity scale. The ordinal scale categorized children into 3 mutually exclusive groups as follows: nonsevere (hospitalization without need for intensive care or empyema requiring drainage), severe (intensive care admission without invasive mechanical ventilation or vasopressor support and no empyema requiring drainage), and very severe (invasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, or empyema requiring drainage).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages and median and interquartile range (IQR) values, respectively. Analyses were stratified by age (2 years, 24 years, 517 years). We also plotted summary statistics for the combined measures and LOS, and computed the median absolute difference between these measures for each level of the ordinal severity scale. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 336 children enrolled in the EPIC study at Vanderbilt during the study period, 334 (99.4%) with complete data were included. Median age was 33 months (IQR, 1480). Median LOS was 56.4 hours (IQR, 41.591.7). There were 249 (74.5%) children classified as nonsevere, 39 (11.7) as severe, and 46 (13.8) as very severe (for age‐based characteristics see Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article). Overall, 12 (3.6%) children were readmitted within 7 days of discharge.

Individual Stability Parameters

Overall, 323 (96.7%) children had 1 parameter abnormal on admission. Respiratory rate (81.4%) was the most common abnormal parameter, followed by abnormal temperature (71.4%), use of supplemental oxygen (63.8%), and abnormal heart rate (54.4%). Overall, use of supplemental oxygen had the longest TCS, followed by respiratory rate (Table 1). In comparison, heart rate and temperature stabilized relatively quickly.

| Parameter | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | |

| ||||||

| Respiratory rate | 97 (74.6) | 38.6 (18.768.9) | 63 (70.0) | 31.6 (9.561.9) | 63 (62.4) | 24.3 (10.859.2) |

| Oxygen | 90 (69.2) | 39.5 (19.273.6) | 58 (64.4) | 44.2 (2477.6) | 61 (60.4) | 38.3 (1870.6) |

| Heart rate | 21 (16.2) | 4.5 (0.318.4) | 73 (81.1) | 21.8 (5.751.9) | 62 (61.4) | 18 (5.842.2) |

| Temperature | 101 (77.7) | 14.5 (4.545.3) | 61 (67.8) | 18.4 (2.842.8) | 62 (61.4) | 10.6 (0.834) |

Seventy children (21.0%) had 1 parameter abnormal at discharge, including abnormal respiratory rate in 13.7%, heart rate in 7.0%, and temperature in 3.3%. One child (0.3%) was discharged with supplemental oxygen. Ten children (3.0%) had 2 parameters abnormal at discharge. There was no difference in 7‐day readmissions for children with 1 parameter abnormal at discharge (1.4%) compared to those with no abnormal parameters at discharge (4.4%, P=0.253).

Combination TCS Measures

Within each age group, the percentage of children achieving stability was relatively consistent across the 4 combined TCS measures (Table 2); however, more children were considered unstable at discharge (and fewer classified as stable on admission) as the number of included parameters increased. More children 5 years of age reached stability (range, 80.0%85.6%) compared to children 5 years of age (range, 68.3%72.3%). We also noted increasing median TCS with increasing disease severity (Figure 1, P0.01) (see Supporting Fig. 1AC in the online version of this article); TCS was only slightly shorter than LOS across all 3 levels of the severity scale.

| TCS Measures | 2 Years, n=130 | 24 Years, n=90 | 517 Years, n=101 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | No. (%) | Median (IQR) TCS, h | ||

| |||||||

| RR+O2 | 108 (83.1) | 40.5 (20.175.0) | 72 (80.0) | 39.6 (15.679.2) | 69 (68.3) | 30.4 (14.759.2) | 0.08 |

| RR+O2+HR | 109 (83.8) | 40.2 (19.573.9) | 73 (81.1) | 35.9 (15.977.6) | 68 (67.3) | 29.8 (17.256.6) | 0.11 |

| RR+O2+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 77 (85.6) | 39.1 (18.477.6) | 73 (72.3) | 28.2 (14.744.7) | 0.03 |

| RR+O2+HR+T | 110 (84.6) | 40.5 (20.770.1) | 72 (80.0) | 39.7 (20.177.5) | 71 (70.3) | 29.2 (18.254) | 0.05 |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that longitudinal TCS measures consisting of routinely collected physiologic parameters may be useful for objectively assessing disease recovery and clinical readiness for discharge among children hospitalized with pneumonia. A simple TCS measure incorporating respiratory rate and oxygen requirement performed similarly to the more complex combinations and classified fewer children as unstable at discharge. However, we also note several challenges that deserve additional study prior to the application of a pediatric TCS measure in clinical and research settings.

Vital signs and supplemental oxygen use are used clinically to assess disease severity and response to therapy among children with acute respiratory illness. Because these objective parameters are routinely collected among hospitalized children, the systematization of these data could inform clinical decision making around hospital discharge. Similar to early warning scores used to detect impending clinical deterioration,[11] TCS measures, by signaling normalization of stability parameters in a consistent and objective manner, could serve as an early signal of readiness for discharge. However, maximizing the clinical utility of TCS would require embedding the process within the electronic health record, a tool that could also have implications for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' meaningful use regulations.[12]

TCS could also serve as an outcome measure in research and quality efforts. Increased disease severity was associated with longer TCS for the 4 combined measures; TCS also demonstrated strong agreement with LOS. Furthermore, TCS minimizes the influence of factors unrelated to disease that may impact LOS (eg, frequency of hospital rounds, transportation difficulties, or social impediments to discharge), an advantage when studying outcomes for research and quality benchmarking.

The percentage of children reaching stability and the median TCS for the combined measures demonstrated little variation within each age group, likely because respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen, 2 of the parameters with the longest individual time to stability, were also included in each of the combination measures. This suggests that less‐complex measures incorporating only respiratory rate and need for supplemental oxygen may be sufficient to assess clinical stability, particularly because these parameters are objectively measured and possess a direct physiological link to pneumonia. In contrast, the other parameters may be more often influenced by factors unrelated to disease severity.

Our study also highlights several shortcomings of the pediatric TCS measures. Despite use of published, age‐based reference values,[13] we noted wide variation in the achievement of stability across individual parameters, especially for children 5 years old. Overall, 21% of children had 1 abnormal parameter at discharge. Even the simplest combined measure classified 13.4% of children as unstable at discharge. Discharge with unstable parameters was not associated with 7‐day readmission, although our study was underpowered to detect small differences. Additional study is therefore needed to evaluate less restrictive cutoff values on calculated TCS and the impact of hospital discharge prior to reaching stability. In particular, relaxing the upper limit for normal respiratory rate in adolescents (16 breaths per minute) to more closely approximate the adult TCS parameter (24 breaths per minute) should be explored. Refinement and standardization of age‐based vital sign reference values specific to hospitalized children may also improve the performance of these measures.[14]

Several limitations deserve discussion. TCS parameters and readmission data were abstracted retrospectively from a single institution, and our findings may not be generalizable. Although clinical staff routinely measured these data, measurement variation likely exists. Nevertheless, such variation is likely systematic, limiting the impact of potential misclassification. TCS was calculated based on the last abnormal value for each parameter; prior fluctuations between normal and abnormal periods of stability were not captured. We were unable to assess room air oxygen saturations. Instead, supplemental oxygen use served as a surrogate for hypoxia. At our institution, oxygen therapy is provided for children with pneumonia to maintain oxygen saturations of 90% to 92%. We did not assess work of breathing (a marker of severe pneumonia) or ability to eat (a component of adult TCS measures). We initially considered the evaluation of intravenous fluids as a proxy for ability to eat (addition of this parameter to the 4 parameter TCS resulted in a modest increase in median time to stability, data not shown); however, we felt the lack of institutional policy and subjective nature of this parameter detracted from our study's objectives. Finally, we were not able to determine clinical readiness for discharge beyond the measurement of vital sign parameters. Therefore, prospective evaluation of the proposed pediatric TCS measures in broader populations will be important to build upon our findings, refine stability parameters, and test the utility of new parameters (eg, ability to eat, work of breathing) prior to use in clinical settings.

Our study provides an initial evaluation of TCS measures for assessing severity and recovery among children hospitalized with pneumonia. Similar to adults, such validated TCS measures may ultimately prove useful for improving the quality of both clinical care and research, although additional study to more clearly define stability criteria is needed prior to implementation.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AI104779 to Dr. Williams. The EPIC study was supported by the Influenza Division in the National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through cooperative agreements with each study site and was based on a competitive research funding opportunity. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grijalva serves as a consultant to Glaxo‐Smith‐Kline and Pfizer outside of the scope of this article. Dr. Edwards is supported through grants from Novartis for the conduction of a Group B strep vaccine study and serves as the Chair of the Data Safety and Monitoring Data Committee for Influenza Study outside the scope of this article. Dr. Self reports grants from CareFusion, BioMerieux, Affinium Pharmaceuticals, Astute Medical, Crucell Holland BV, BRAHMS GmbH, Pfizer, Rapid Pathogen Screening, Venaxis, BioAegis Inc., Sphingotec GmbH, and Cempra Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from BioFire Diagnostics and Venaxis, Inc; and patent 13/632,874 (Sterile Blood Culture Collection System) pending; all outside the scope of this article.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/index.html. Accessed February 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–1457.

- , , , et al.; Neumofail Group. Reaching stability in community‐acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783–1790.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization. The pneumonia severity index predicts time to clinical stability in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:739–743.

- , , , , . Efficacy of corticosteroids in community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomized double‐blinded clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:975–982.

- , , , et al. Early administration of antibiotics does not shorten time to clinical stability in patients with moderate‐to‐severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1798–1804.

- , , , . A comparison between time to clinical stability in community‐acquired aspiration pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9:143–150.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. A worldwide perspective of atypical pathogens in community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1086–1093.

- , , , et al.; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835–845.

- American Heart Association. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e989–e1004.

- , , . Development and initial validation of the Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System score. Crit Care. 2009;13:R135.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Regulations and guidance. EHR incentive programs. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations‐and‐Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html. Accessed February 20, 2015

- , , , , , . Development of heart and respiratory rate percentile curves for hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1150–e1157.

- , , , et al. Length of stay after reaching clinical stability drives hospital costs associated with adult community‐acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:219–226.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/hcup/index.html. Accessed February 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–1457.

- , , , et al.; Neumofail Group. Reaching stability in community‐acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783–1790.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization. The pneumonia severity index predicts time to clinical stability in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:739–743.

- , , , , . Efficacy of corticosteroids in community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomized double‐blinded clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:975–982.

- , , , et al. Early administration of antibiotics does not shorten time to clinical stability in patients with moderate‐to‐severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1798–1804.

- , , , . A comparison between time to clinical stability in community‐acquired aspiration pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9:143–150.

- , , , et al.; Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. A worldwide perspective of atypical pathogens in community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1086–1093.

- , , , et al.; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835–845.

- American Heart Association. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e989–e1004.

- , , . Development and initial validation of the Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System score. Crit Care. 2009;13:R135.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Regulations and guidance. EHR incentive programs. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations‐and‐Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html. Accessed February 20, 2015

- , , , , , . Development of heart and respiratory rate percentile curves for hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1150–e1157.

- , , , et al. Length of stay after reaching clinical stability drives hospital costs associated with adult community‐acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:219–226.

Drug can prevent bleeding in kids with hemophilia A

A recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein (rFVIIIFc/efmoroctocog alfa, Eloctate/Elocta) can prevent and control bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, results of the phase 3 KIDS A-LONG study suggest.

Children who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis saw their median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) decrease with rFVIIIFc, and close to half of the children on this study did not have any bleeding episodes while they were receiving rFVIIIFc.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to rFVIIIFc. And researchers said adverse events on this trial were typical of a pediatric hemophilia population.

The team reported these results in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. The trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing rFVIIIFc.

The study included 71 boys younger than 12 years of age who had severe hemophilia A. The patients had at least 50 prior exposure days to factor VIII and no history of factor VIII inhibitors.

The children were set to receive twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of rFVIIIFc, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4, but the researchers made adjustments to dosing as needed.

The median average weekly rFVIIIFc prophylactic dose was 88.11 IU kg. About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study. Seventy-four percent of patients were able to reduce their dosing frequency with rFVIIIFc compared to factor VIII prophylaxis.

About 46% of patients did not have any bleeding events on study. The median ABR was 1.96 overall and 0 for spontaneous and traumatic bleeding episodes, as well as for spontaneous joint bleeding episodes.

Among patients who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis, their median ABR decreased with rFVIIIFc. For children younger than 6 years of age, the median ABR fell from 1.50 to 0. For children ages 6 through 11, the median ABR fell from 2.50 to 2.01.

About 86% of patients had at least one adverse event while on rFVIIIFc, but none of them discontinued treatment as a result.

Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were considered related to rFVIIIFc. And 5 patients experienced 7 serious adverse events that were not related to treatment. ![]()

A recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein (rFVIIIFc/efmoroctocog alfa, Eloctate/Elocta) can prevent and control bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, results of the phase 3 KIDS A-LONG study suggest.

Children who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis saw their median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) decrease with rFVIIIFc, and close to half of the children on this study did not have any bleeding episodes while they were receiving rFVIIIFc.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to rFVIIIFc. And researchers said adverse events on this trial were typical of a pediatric hemophilia population.

The team reported these results in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. The trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing rFVIIIFc.

The study included 71 boys younger than 12 years of age who had severe hemophilia A. The patients had at least 50 prior exposure days to factor VIII and no history of factor VIII inhibitors.

The children were set to receive twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of rFVIIIFc, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4, but the researchers made adjustments to dosing as needed.

The median average weekly rFVIIIFc prophylactic dose was 88.11 IU kg. About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study. Seventy-four percent of patients were able to reduce their dosing frequency with rFVIIIFc compared to factor VIII prophylaxis.

About 46% of patients did not have any bleeding events on study. The median ABR was 1.96 overall and 0 for spontaneous and traumatic bleeding episodes, as well as for spontaneous joint bleeding episodes.

Among patients who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis, their median ABR decreased with rFVIIIFc. For children younger than 6 years of age, the median ABR fell from 1.50 to 0. For children ages 6 through 11, the median ABR fell from 2.50 to 2.01.

About 86% of patients had at least one adverse event while on rFVIIIFc, but none of them discontinued treatment as a result.

Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were considered related to rFVIIIFc. And 5 patients experienced 7 serious adverse events that were not related to treatment. ![]()

A recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein (rFVIIIFc/efmoroctocog alfa, Eloctate/Elocta) can prevent and control bleeding in previously treated children with severe hemophilia A, results of the phase 3 KIDS A-LONG study suggest.

Children who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis saw their median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) decrease with rFVIIIFc, and close to half of the children on this study did not have any bleeding episodes while they were receiving rFVIIIFc.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to rFVIIIFc. And researchers said adverse events on this trial were typical of a pediatric hemophilia population.

The team reported these results in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. The trial was sponsored by Biogen Idec and Sobi, the companies developing rFVIIIFc.

The study included 71 boys younger than 12 years of age who had severe hemophilia A. The patients had at least 50 prior exposure days to factor VIII and no history of factor VIII inhibitors.

The children were set to receive twice-weekly prophylactic infusions of rFVIIIFc, 25 IU/kg on day 1 and 50 IU/kg on day 4, but the researchers made adjustments to dosing as needed.

The median average weekly rFVIIIFc prophylactic dose was 88.11 IU kg. About 90% of the patients were on twice-weekly dosing at the end of the study. Seventy-four percent of patients were able to reduce their dosing frequency with rFVIIIFc compared to factor VIII prophylaxis.

About 46% of patients did not have any bleeding events on study. The median ABR was 1.96 overall and 0 for spontaneous and traumatic bleeding episodes, as well as for spontaneous joint bleeding episodes.

Among patients who were previously receiving factor VIII prophylaxis, their median ABR decreased with rFVIIIFc. For children younger than 6 years of age, the median ABR fell from 1.50 to 0. For children ages 6 through 11, the median ABR fell from 2.50 to 2.01.

About 86% of patients had at least one adverse event while on rFVIIIFc, but none of them discontinued treatment as a result.

Two non-serious events (myalgia and erythematous rash) were considered related to rFVIIIFc. And 5 patients experienced 7 serious adverse events that were not related to treatment. ![]()

Chemotherapy drugs recalled in US

Photo by Bill Branson

The pharmaceutical company Mylan is conducting a US-wide recall of several injectable chemotherapy drugs.

Testing of retention samples revealed foreign particulate matter in lots of gemcitabine, carboplatin, methotrexate, and cytarabine. So Mylan issued a

recall of these lots to the hospital/user level.

To date, Mylan has not received any reports of adverse events related to this recall. However, administering injectables that contain foreign particulates can have severe consequences.

Intrathecal administration could result in a life-threatening adverse event or permanent impairment of a body function. Intravenous administration has the potential to damage and/or obstruct blood vessels, which could induce emboli, particularly in the lungs. Intravenous injection can also result in local inflammation, phlebitis, allergic response, and/or embolization in the body and infection.

Intra-arterial administration could result in damage to blood vessels in the distal extremities or organs. And intramuscular administration could result in foreign-body inflammatory response, with local pain, swelling, and possible long-term granuloma formation.

Recall details

The following drugs are included in this recall:

- Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 200 mg; 10 mL; NDC number: 67457-464-20; Lot number: 7801396; Expiration date: 08/2016

- Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 200 mg; 10 mL; NDC number: 67457-464-20; Lot number: 7801401; Expiration date: 08/2016

- Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 200 mg; 10 mL; NDC number: 0069-3857-10; Lot number: 7801089; Expiration date: 07/2015

- Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 2 g; 100 mL; NDC number: 67457-463-02; Lot number: 7801222; Expiration date: 03/2016

- Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 1 g; 50 mL; NDC number: 67457-462-01; Lot number: 7801273; Expiration date: 05/2016

- Carboplatin Injection 10 mg/mL; 100 mL; NDC number: 67457-493-46; Lot number: 7801312; Expiration date: 06/2015

- Methotrexate Injection, USP 25 mg/mL; 2 mL (5 x 2 mL); NDC number: 0069-0146-02; Lot number: 7801082; Expiration date: 07/2015

- Cytarabine Injection 20 mg/mL; 5 mL (10 x 5mL); NDC number: 0069-0152-02; Lot number: 7801050; Expiration date: 05/2015.

Gemcitabine for Injection, USP 200 mg is an intravenously administered product indicated for the treatment of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer. These lots were distributed in the US between February 18, 2014, and December 19, 2014, and were manufactured and packaged by Agila Onco Therapies Limited, a Mylan company. Lot 7801089 is packaged with a Pfizer Injectable label.

Carboplatin Injection 10 mg/mL is an intravenously administered product indicated for the treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma. The lot was distributed in the US between August 11, 2014, and October 7, 2014, and was packaged by Agila Onco Therapies Limited, a Mylan company, with a Mylan Institutional label.

Methotrexate Injection, USP 25 mg/mL can be administered intramuscularly, intravenously, intra-arterially, or intrathecally and is indicated for certain neoplastic diseases, severe psoriasis, and adult rheumatoid arthritis. The lot was distributed in the US between January 16, 2014, and March 25, 2014, and was packaged by Agila Onco Therapies Limited, a Mylan company, with a Pfizer Injectables label.