User login

MM: Newest IKEMA results back isatuximab

Median follow up was 44 months in the new update, about 2 additional years past the earlier report.

As in the earlier analysis, adding the anti-CD38 antibody to carfilzomib and dexamethasone brought substantial benefits, including a median progression free survival (PFS) of 35.7 months versus 19.2 months with placebo, as well as a higher rates of complete response (CR, 44.1% vs. 28.5%), minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (33.5% vs. 15.4%), and MRD negativity CR (26.3% vs. 12.2%).

Although overall survival data are not yet mature, the probability of being alive at 42 months was 66.3% with isatuximab add-on versus 54.5% with placebo.

Investigators led by Thomas G. Martin, MD, director of the University of California, San Francisco, myeloma program, noted that median PFS of nearly 3 years “is the longest PFS reported to date with a PI-based regimen in the relapsed MM [multiple myeloma] setting.” The updated results further support the combination “as a standard of care treatment for patients with relapsed MM.”

Overall, the trial adds “another effective triplet in the treatment of patients with” relapsed/refractory MM, Sergio A. Giralt, MD, head of the division of hematologic malignancies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said when asked for comment. The study was published May 9 in Blood Cancer Journal.

Safety similar to interim analysis

IKEMA randomized 179 patients to isatuximab add-on and 123 to placebo. Patients had relapsed/refractory MM with one to three prior treatment lines. Isatuximab was dosed at10 mg/kg IV in the open-label trial, weekly in the first cycle then biweekly.

The PFS benefit held across various subgroups, including the elderly and others with poor prognoses.

In their write-up, the investigators acknowledged isatuximab’s rival anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex), which is also approved in the United States for use in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory MM after one to three treatment lines.

“Although inter-trial evaluations should be interpreted with caution,” they noted that PFS in the latest analysis of daratumumab’s CANDOR trial in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone was shorter than in IKEMA, 28.6 months versus 15.2 months with placebo.

Like efficacy, safety in latest update of IKEMA was similar to that of the interim analysis. However, while there was no difference in the incidence of all-cause serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the earlier report, the incidence was higher with isatuximab than placebo in the newest findings (70.1% vs. 59.8%).

The investigators said the difference was likely because patients in the isatuximab arm stayed on treatment longer, a median of 94 weeks versus 61.9 weeks in the placebo arm, making adverse events more likely.

The most common, nonhematologic TEAEs were infusion reactions (45.8% in the isatuximab arm vs. 3.3% in the placebo group), diarrhea (39.5% vs. 32%), hypertension (37.9% vs 35.2%), upper respiratory tract infection (37.3% vs 27%), and fatigue (31.6% vs 20.5%).

Grade 3 or higher pneumonia occurred in 18.6% patients in the isatuximab arm versus 12.3% in the placebo group. The incidence of skin cancer was 6.2% with isatuximab versus 3.3%. The incidence of treatment-emergent fatal events remained similar between study arms, 5.6% with isatuximab versus 4.9% with placebo.

The study was funded by Sanofi, maker of isatuximab. Investigators included two Sanofi employees. Others reported a range of ties to the company, including Dr. Martin, who reported research funding and sitting on a Sanofi steering committee.

Median follow up was 44 months in the new update, about 2 additional years past the earlier report.

As in the earlier analysis, adding the anti-CD38 antibody to carfilzomib and dexamethasone brought substantial benefits, including a median progression free survival (PFS) of 35.7 months versus 19.2 months with placebo, as well as a higher rates of complete response (CR, 44.1% vs. 28.5%), minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (33.5% vs. 15.4%), and MRD negativity CR (26.3% vs. 12.2%).

Although overall survival data are not yet mature, the probability of being alive at 42 months was 66.3% with isatuximab add-on versus 54.5% with placebo.

Investigators led by Thomas G. Martin, MD, director of the University of California, San Francisco, myeloma program, noted that median PFS of nearly 3 years “is the longest PFS reported to date with a PI-based regimen in the relapsed MM [multiple myeloma] setting.” The updated results further support the combination “as a standard of care treatment for patients with relapsed MM.”

Overall, the trial adds “another effective triplet in the treatment of patients with” relapsed/refractory MM, Sergio A. Giralt, MD, head of the division of hematologic malignancies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said when asked for comment. The study was published May 9 in Blood Cancer Journal.

Safety similar to interim analysis

IKEMA randomized 179 patients to isatuximab add-on and 123 to placebo. Patients had relapsed/refractory MM with one to three prior treatment lines. Isatuximab was dosed at10 mg/kg IV in the open-label trial, weekly in the first cycle then biweekly.

The PFS benefit held across various subgroups, including the elderly and others with poor prognoses.

In their write-up, the investigators acknowledged isatuximab’s rival anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex), which is also approved in the United States for use in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory MM after one to three treatment lines.

“Although inter-trial evaluations should be interpreted with caution,” they noted that PFS in the latest analysis of daratumumab’s CANDOR trial in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone was shorter than in IKEMA, 28.6 months versus 15.2 months with placebo.

Like efficacy, safety in latest update of IKEMA was similar to that of the interim analysis. However, while there was no difference in the incidence of all-cause serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the earlier report, the incidence was higher with isatuximab than placebo in the newest findings (70.1% vs. 59.8%).

The investigators said the difference was likely because patients in the isatuximab arm stayed on treatment longer, a median of 94 weeks versus 61.9 weeks in the placebo arm, making adverse events more likely.

The most common, nonhematologic TEAEs were infusion reactions (45.8% in the isatuximab arm vs. 3.3% in the placebo group), diarrhea (39.5% vs. 32%), hypertension (37.9% vs 35.2%), upper respiratory tract infection (37.3% vs 27%), and fatigue (31.6% vs 20.5%).

Grade 3 or higher pneumonia occurred in 18.6% patients in the isatuximab arm versus 12.3% in the placebo group. The incidence of skin cancer was 6.2% with isatuximab versus 3.3%. The incidence of treatment-emergent fatal events remained similar between study arms, 5.6% with isatuximab versus 4.9% with placebo.

The study was funded by Sanofi, maker of isatuximab. Investigators included two Sanofi employees. Others reported a range of ties to the company, including Dr. Martin, who reported research funding and sitting on a Sanofi steering committee.

Median follow up was 44 months in the new update, about 2 additional years past the earlier report.

As in the earlier analysis, adding the anti-CD38 antibody to carfilzomib and dexamethasone brought substantial benefits, including a median progression free survival (PFS) of 35.7 months versus 19.2 months with placebo, as well as a higher rates of complete response (CR, 44.1% vs. 28.5%), minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (33.5% vs. 15.4%), and MRD negativity CR (26.3% vs. 12.2%).

Although overall survival data are not yet mature, the probability of being alive at 42 months was 66.3% with isatuximab add-on versus 54.5% with placebo.

Investigators led by Thomas G. Martin, MD, director of the University of California, San Francisco, myeloma program, noted that median PFS of nearly 3 years “is the longest PFS reported to date with a PI-based regimen in the relapsed MM [multiple myeloma] setting.” The updated results further support the combination “as a standard of care treatment for patients with relapsed MM.”

Overall, the trial adds “another effective triplet in the treatment of patients with” relapsed/refractory MM, Sergio A. Giralt, MD, head of the division of hematologic malignancies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said when asked for comment. The study was published May 9 in Blood Cancer Journal.

Safety similar to interim analysis

IKEMA randomized 179 patients to isatuximab add-on and 123 to placebo. Patients had relapsed/refractory MM with one to three prior treatment lines. Isatuximab was dosed at10 mg/kg IV in the open-label trial, weekly in the first cycle then biweekly.

The PFS benefit held across various subgroups, including the elderly and others with poor prognoses.

In their write-up, the investigators acknowledged isatuximab’s rival anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex), which is also approved in the United States for use in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory MM after one to three treatment lines.

“Although inter-trial evaluations should be interpreted with caution,” they noted that PFS in the latest analysis of daratumumab’s CANDOR trial in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone was shorter than in IKEMA, 28.6 months versus 15.2 months with placebo.

Like efficacy, safety in latest update of IKEMA was similar to that of the interim analysis. However, while there was no difference in the incidence of all-cause serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the earlier report, the incidence was higher with isatuximab than placebo in the newest findings (70.1% vs. 59.8%).

The investigators said the difference was likely because patients in the isatuximab arm stayed on treatment longer, a median of 94 weeks versus 61.9 weeks in the placebo arm, making adverse events more likely.

The most common, nonhematologic TEAEs were infusion reactions (45.8% in the isatuximab arm vs. 3.3% in the placebo group), diarrhea (39.5% vs. 32%), hypertension (37.9% vs 35.2%), upper respiratory tract infection (37.3% vs 27%), and fatigue (31.6% vs 20.5%).

Grade 3 or higher pneumonia occurred in 18.6% patients in the isatuximab arm versus 12.3% in the placebo group. The incidence of skin cancer was 6.2% with isatuximab versus 3.3%. The incidence of treatment-emergent fatal events remained similar between study arms, 5.6% with isatuximab versus 4.9% with placebo.

The study was funded by Sanofi, maker of isatuximab. Investigators included two Sanofi employees. Others reported a range of ties to the company, including Dr. Martin, who reported research funding and sitting on a Sanofi steering committee.

FROM BLOOD CANCER JOURNAL

Enlarging Pigmented Lesion on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

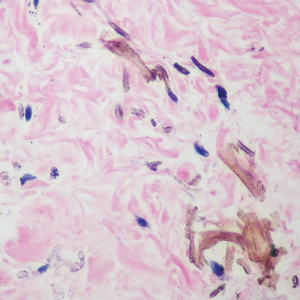

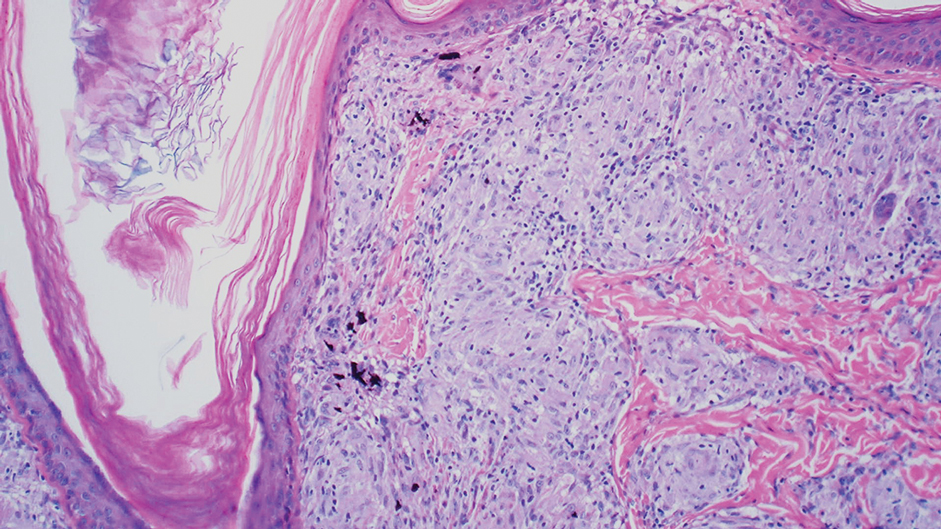

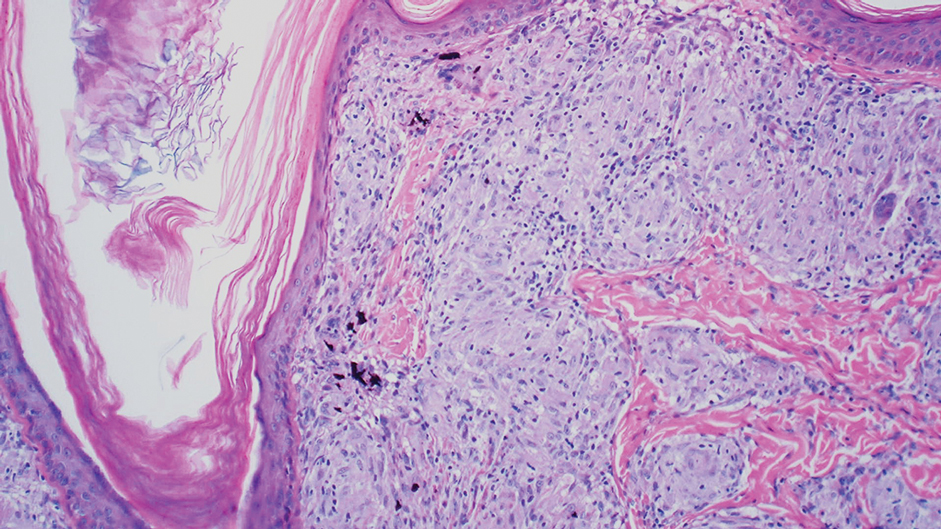

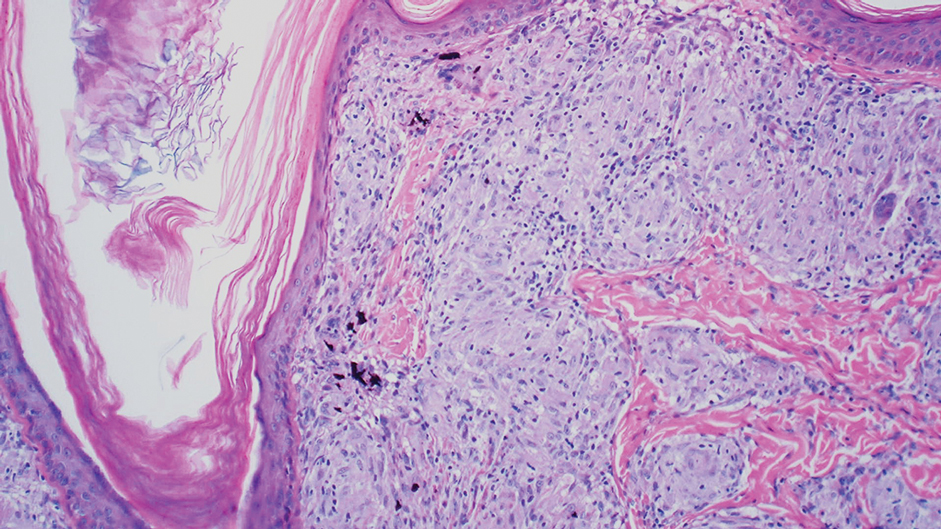

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

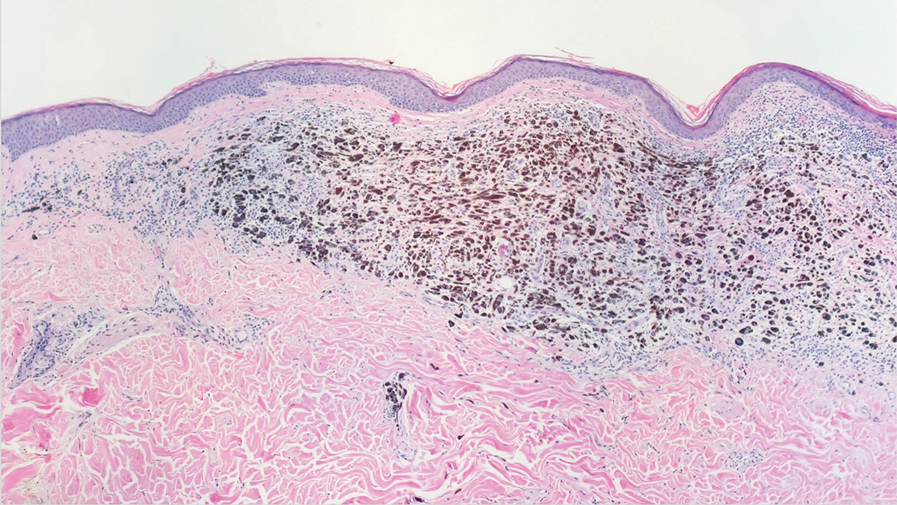

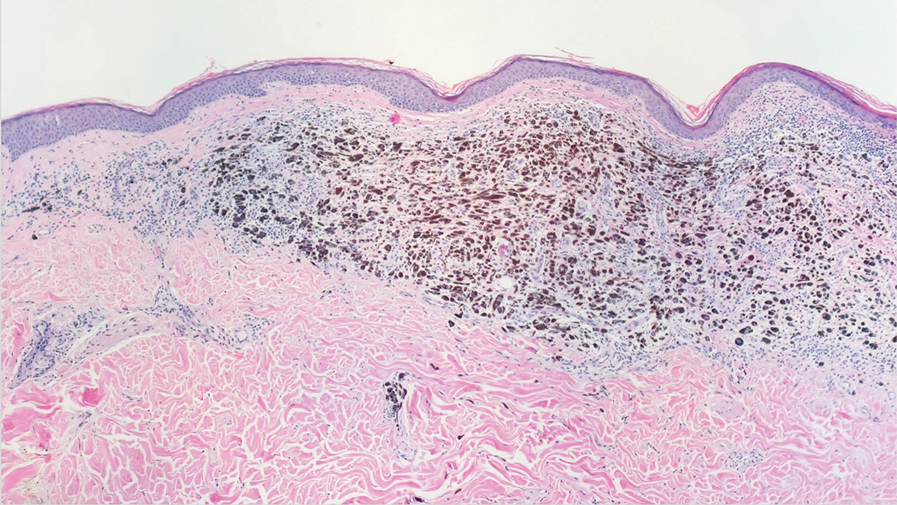

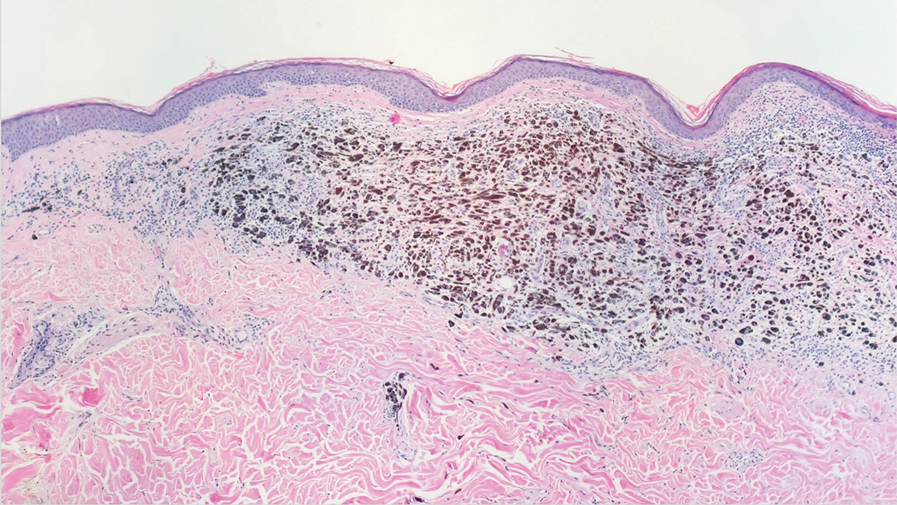

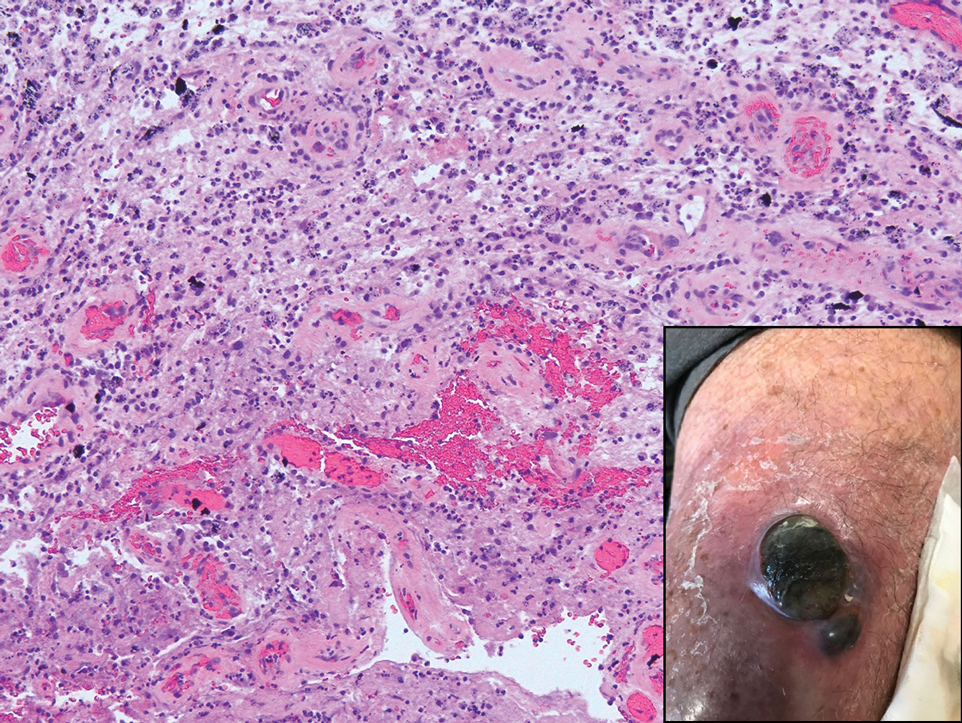

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

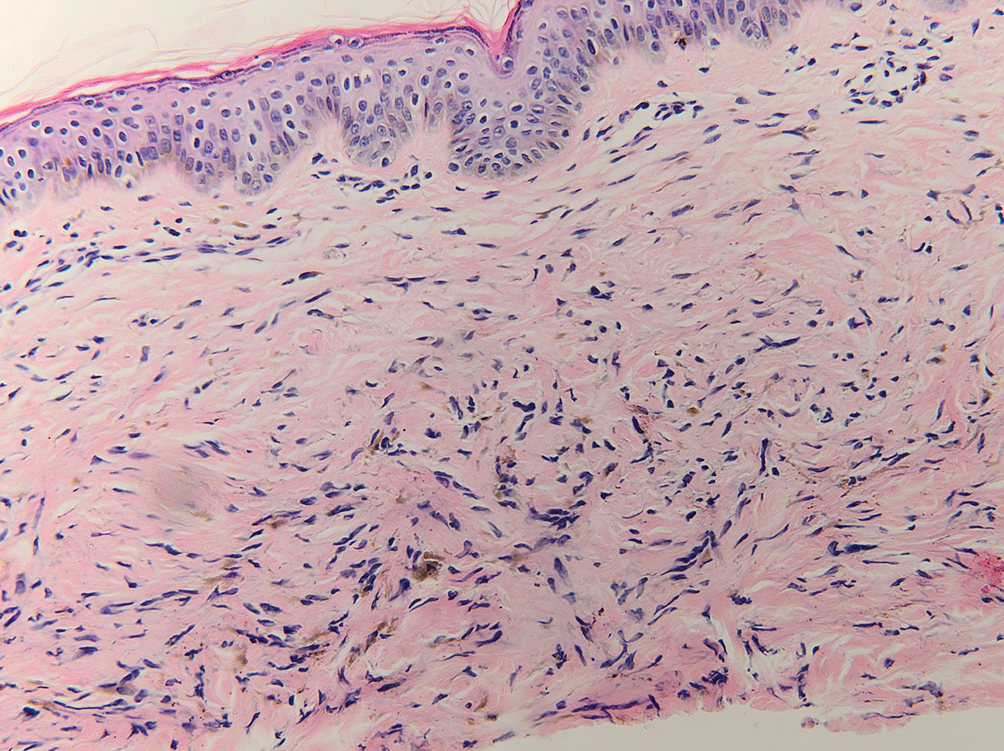

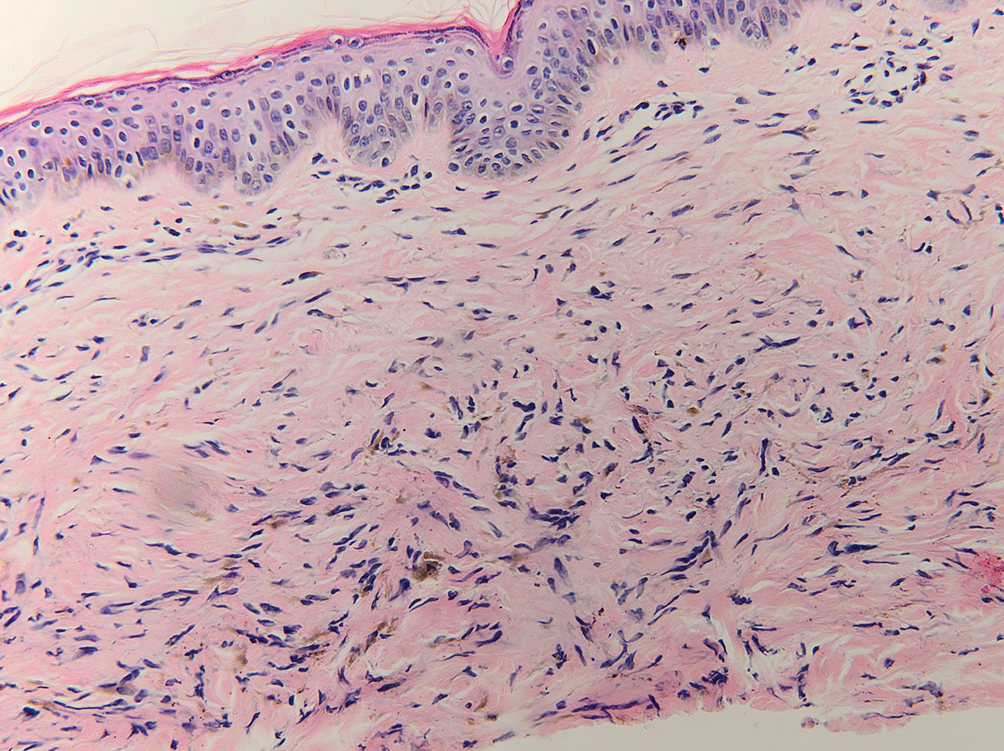

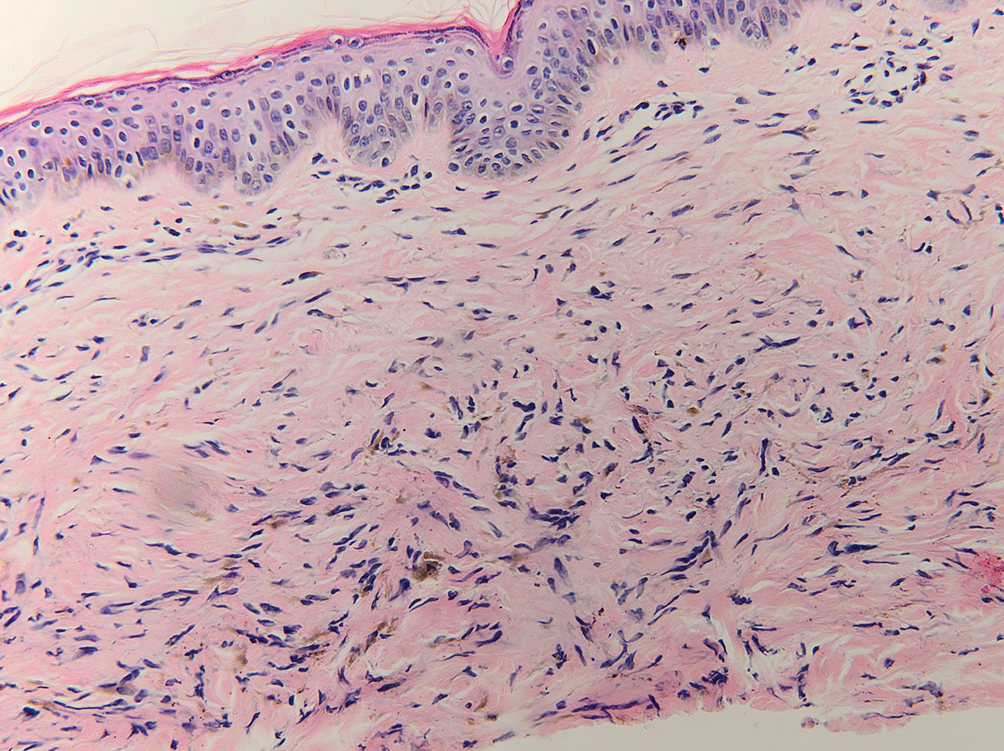

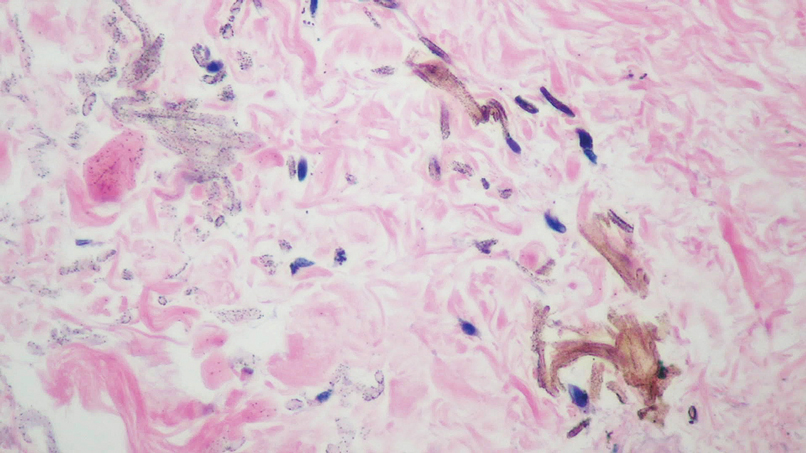

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

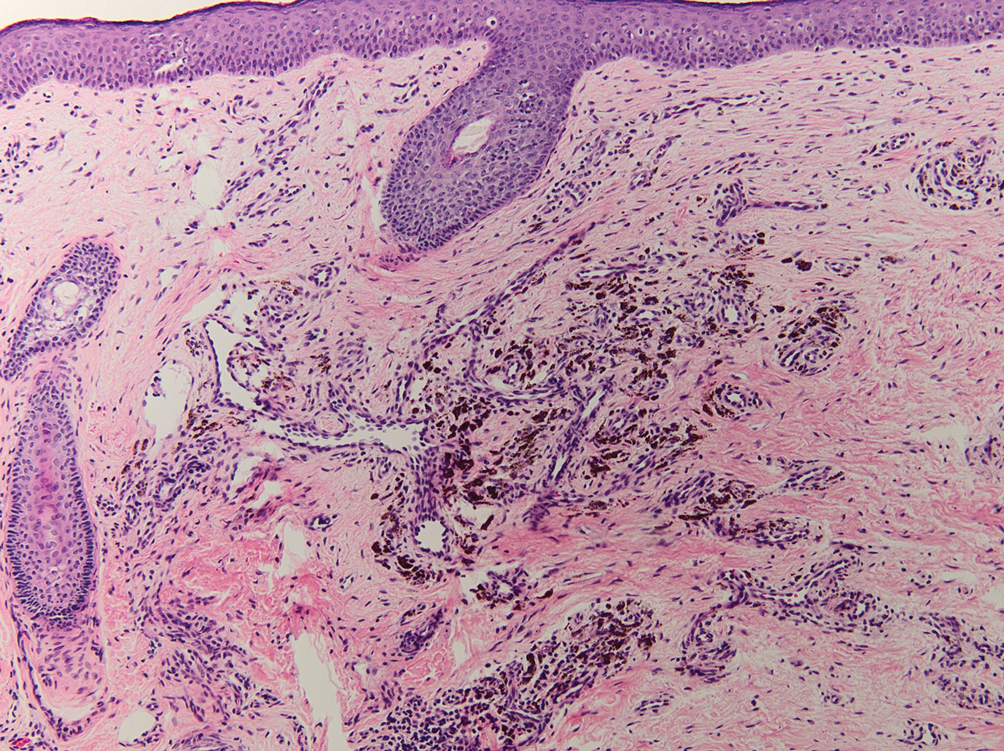

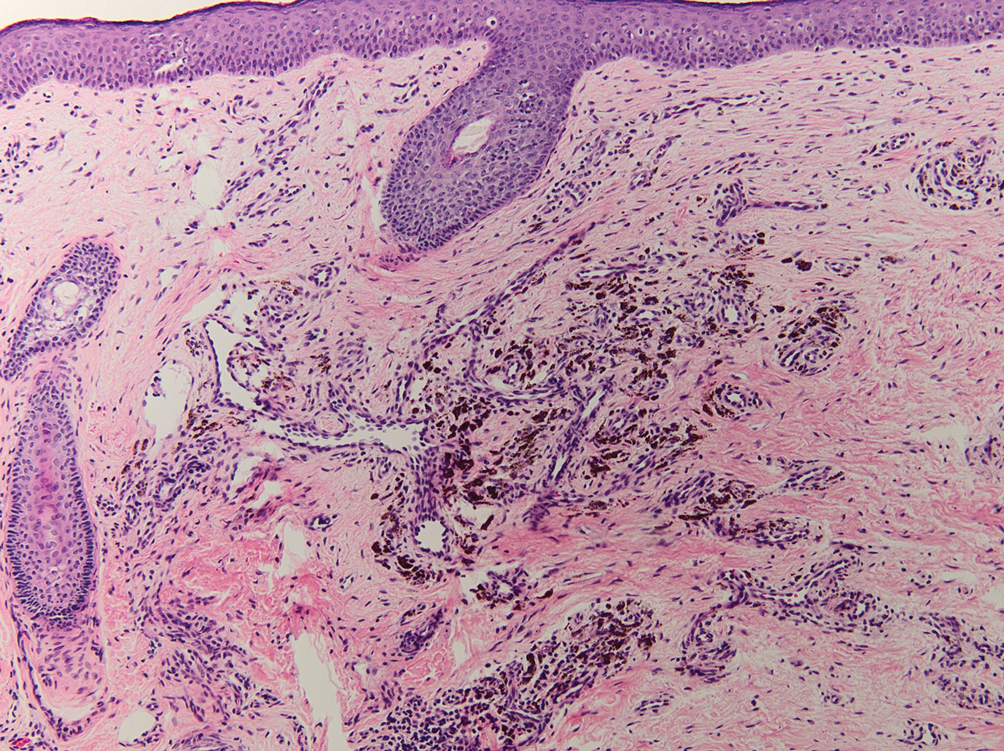

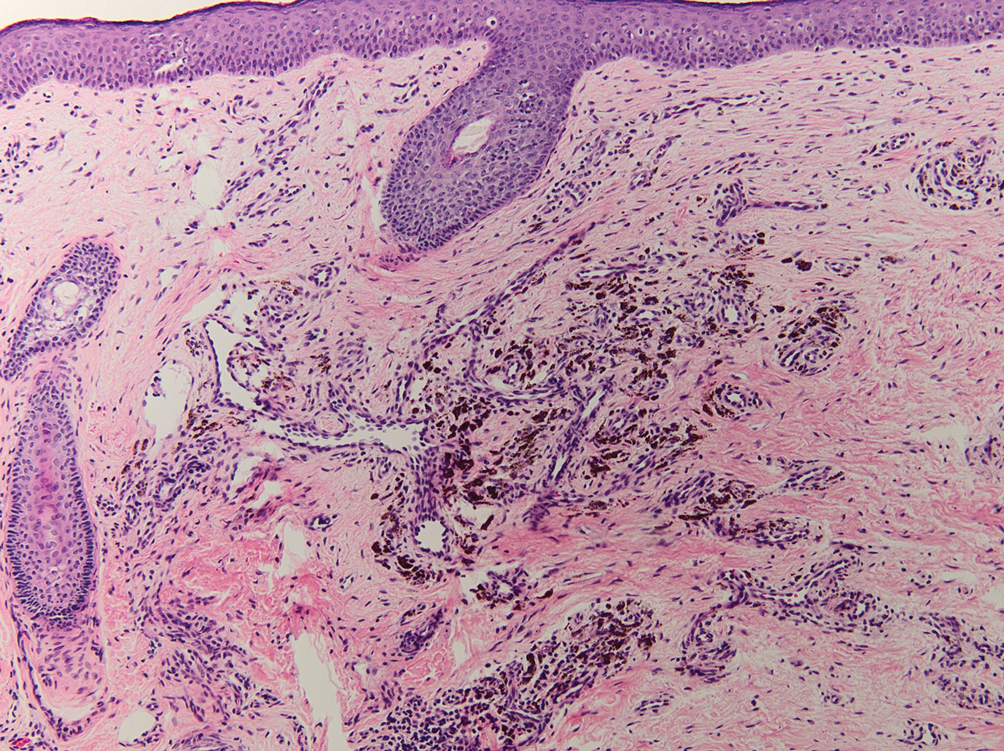

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

An 80-year-old man presented with a pigmented lesion on the left lateral thigh near the knee that had been gradually enlarging over several weeks (top [inset]). He underwent a left knee replacement surgery for advanced osteoarthritis many months prior that was complicated by postoperative Staphylococcus aureus infection with sinus tract formation that was persistent for 6 months and treated with a topical medication. A pigmented lesion developed near the opening of the sinus tract. His medical history was remarkable for extensive actinic damage as well as multiple actinic keratoses treated with cryotherapy but no history of melanoma. An excisional biopsy was performed (top and bottom).

Serum Ferritin Levels: A Clinical Guide in Patients With Hair Loss

Ferritin is an iron storage protein crucial to human iron homeostasis. Because serum ferritin levels are in dynamic equilibrium with the body’s iron stores, ferritin often is measured as a reflection of iron status; however, ferritin also is an acute-phase reactant whose levels may be nonspecifically elevated in a wide range of inflammatory conditions. The various processes that alter serum ferritin levels complicate the clinical interpretation of this laboratory value. In this article, we review the structure and function of ferritin and provide a guide for clinical use.

Overview of Iron

Iron is an essential element of key biologic functions including DNA synthesis and repair, oxygen transport, and oxidative phosphorylation. The body’s iron stores are mainly derived from internal iron recycling following red blood cell breakdown, while 5% to 10% is supplied by dietary intake.1-3 Iron metabolism is of particular importance in cells of the reticuloendothelial system (eg, spleen, liver, bone marrow), where excess iron must be appropriately sequestered and from which iron can be mobilized.4 Sufficient iron stores are necessary for proper cellular function and survival, as iron is a necessary component of hemoglobin for oxygen delivery, iron-sulfur clusters in electron transport, and enzyme cofactors in other cellular processes.

Although labile pools of biologically active free iron exist in limited amounts within cells, excess free iron can generate free radicals that damage cellular proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.5-7 As such, most intracellular iron is captured within ferritin molecules. The excretion of iron is unregulated and occurs through loss in sweat, menstruation, hair shedding, skin desquamation, and enterocyte turnover.8 The lack of regulated excretion highlights the need for a tightly regulated system of uptake, transportation, storage, and sequestration to maintain iron homeostasis.

Overview of Ferritin Structure and Function

Ferritin is a key regulator of iron homeostasis that also serves as an important clinical indicator of body iron status. Ferritin mainly is found as an intracellular cytosolic iron storage and detoxification protein structured as a hollow 24-subunit polymer shell that can sequester up to 4500 atoms of iron within its core.9,10 The 24-mer is composed of both ferritin L (FTL) and ferritin H (FTH) subunits, with dynamic regulation of the H:L ratio dependent on the context and tissue in which ferritin is found.6

Ferritin H possesses ferroxidase, which facilitates oxidation of ferrous (Fe2+) iron into ferric (Fe3+) iron, which can then be incorporated into the mineral core of the ferritin heteropolymer.11 Ferritin L is more abundant in the spleen and liver, while FTH is found predominantly in the heart and kidneys where the increased ferroxidase activity may confer an increased ability to oxidize Fe2+ and limit oxidative stress.6

Regulation of Ferritin Synthesis and Secretion

Ferritin synthesis is regulated by intracellular nonheme iron levels, governed mainly by an iron response element (IRE) and iron response protein (IRP) translational repression system. Both FTH and FTL messenger RNA (mRNA) contain an IRE that is a regulatory stem-loop structure in the 5´ untranslated region. When the IRE is bound by IRP1 or IRP2, mRNA translation of ferritin subunits is suppressed.6 In low iron conditions, IRPs have greater affinity for IRE, and binding suppresses ferritin translation.12 In high iron conditions, IRPs have a decreased affinity for IRE, and ferritin mRNA synthesis is increased.13 Additionally, inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1α transcriptionally induce FTH synthesis, resulting in an increased population of H-rich ferritins.11,14-16 A study using cultured human primary skin fibroblasts demonstrated UV radiation–induced increases in free intracellular iron content.17,18 Pourzand et al18 suggested that UV-mediated damage of lysosomal membranes results in leakage of lysosomal proteases into the cytosol, contributing to degradation of intracellular ferritin and subsequent release of iron within skin fibroblasts. The increased intracellular iron downregulates IRPs and increases ferritin mRNA synthesis,18 consistent with prior findings of increased ferritin synthesis in skin that is induced by UV radiation.19

Molecular analysis of serum ferritin in iron-overloaded mice revealed that extracellular ferritin found in the serum is composed of a greater fraction of FTL and has lower iron content than intracellular ferritin. The low iron content of serum ferritin compared with intracellular ferritin and transferrin suggests that serum ferritin is not a major pathway of systemic iron transport.10 However, locally secreted ferritins may play a greater role in iron transport and release in selected tissues. Additionally, in vitro studies of cell cultures from humans and mice have demonstrated the ability of macrophages to secrete ferritin, suggesting that macrophages are an important cellular source of serum ferritin.10,20 As such, serum ferritin generally may reflect body iron status but more specifically reflects macrophage iron status.10 Although the exact pathways of ferritin release are unknown, it is hypothesized that ferritin secretion occurs through cytosolic autophagy followed by secretion of proteins from the lysosomal compartment.10,18,21

Clinical Utility of Serum Ferritin

Low Ferritin and Iron Deficiency—Although bone marrow biopsy with iron staining remains the gold standard for diagnosis of iron deficiency, serum ferritin is a much more accessible and less invasive tool for evaluation of iron status. A serum ferritin level below 12 μg/L is highly specific for iron depletion,22 with a higher cutoff recommended in clinical practice to improve diagnostic sensitivity.23,24 Conditions independent of iron deficiency that may reduce serum ferritin include hypothyroidism and ascorbate deficiency, though neither condition has been reported to interfere with appropriate diagnosis of iron deficiency.25 Guyatt et al26 conducted a systematic review of laboratory tests used in the diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia and identified 55 studies suitable for inclusion. Based on an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.95, serum ferritin values were superior to transferrin saturation (AUROC, 0.74), red cell protoporphyrin (AUROC, 0.77), red cell volume distribution width (AUROC, 0.62), and mean cell volume (AUROC, 0.76) for diagnosis of IDA, verified by histologic examination of aspirated bone marrow.26 The likelihood ratio of iron deficiency begins to decrease for serum ferritin values of 40 μg/L or greater. For patients with inflammatory conditions—patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, inflammatory disease, infection, rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy—the likelihood of iron deficiency begins to decrease at serum ferritin levels of 70 μg/L or greater.26 Similarly, the World Health Organization recommends that in adults with infection or inflammation, serum ferritin levels lower than 70 μg/L may be used to indicate iron deficiency.24 A serum ferritin level of 41 μg/L or lower was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 98% for discriminating between iron-deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease (diagnosed based on bone marrow biopsy with iron staining), with an AUROC of 0.98.27 As such, we recommend using a serum ferritin level of 40 μg/L or lower in patients who are otherwise healthy as an indicator of iron deficiency.

The threshold for iron supplementation may vary based on age, sex, and race. In women, ferritin levels increase during menopause and peak after menopause; ferritin levels are higher in men than in women.28-30 A multisite longitudinal cohort study of 70 women in the United States found that the mean (SD) ferritin valuewas 69.5 (81.7) μg/L premenopause and 128.8 (125.7) μg/L postmenopause (P<.01).31 A separate longitudinal survey study of 8564 patients in China found that the mean (SE) ferritin value was 201.55 (3.60) μg/L for men and 80.46 (1.64) μg/L for women (P<.0001).32 Analysis of serum ferritin levels of 3554 male patients from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrated that patients who self-reported as non-Hispanic Black (n=1616) had significantly higher serum ferritin levels than non-Hispanic White patients (n=1938)(serum ferritin difference of 37.1 μg/L)(P<.0001).33 The British Society for Haematology guidelines recommend that the threshold of serum ferritin for diagnosing iron deficiency should take into account age-, sex-, and race-based differences.34 Ferritin and Hair—Cutaneous manifestations of iron deficiency include koilonychia, glossitis, pruritus, angular cheilitis, and telogen effluvium (TE).1 A case-control study of 30 females aged 15 to 45 years demonstrated that the mean (SD) ferritin level was significantly lower in patients with TE than those with no hair loss (16.3 [12.6] ng/mL vs 60.3 [50.1] ng/mL; P<.0001). Using a threshold of 30 μg/L or lower, the investigators found that the odds ratio for TE was 21.0 (95% CI, 4.2-105.0) in patients with low serum ferritin.35

Another retrospective review of 54 patients with diffuse hair loss and 55 controls compared serum vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, zinc, ferritin, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels between the 2 groups.36 Exclusion criteria were clinical diagnoses of female pattern hair loss (androgenetic alopecia), pregnancy, menopause, metabolic and endocrine disorders, hormone replacement therapy, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy, vitamin and mineral supplementation, scarring alopecia, eating disorders, and restrictive diets. Compared with controls, patients with diffuse nonscarring hair loss were found to have significantly lower ferritin (mean [SD], 14.72 [10.70] ng/mL vs 25.30 [14.41] ng/mL; P<.001) and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels (mean [SD], 14.03 [8.09] ng/mL vs 17.01 [8.59] ng/mL; P=.01).36

In contrast, a separate case-control study of 381 cases and 76 controls found no increase in the rate of iron deficiency—defined as ferritin ≤15 μg/L or ≤40 μg/L—among women with female pattern hair loss or chronic TE vs controls.37 Taken together, these studies suggest that iron status may play a role in TE, a process that may result from nutritional deficiency, trauma, or physical or psychological stress38; however, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that low iron status impacts androgenetic alopecia, in which its multifactorial pathogenesis implicates genetic and hormonal factors.39 More research is needed to clarify the potential associations between iron deficiency and types of hair loss. Additionally, it is unclear whether iron supplementation improves hair growth parameters such as density and caliber.40

Low serum ferritin (<40 μg/L) with concurrent symptoms of iron deficiency, including fatigue, pallor, dyspnea on exertion, or hair loss, should prompt treatment with supplemental iron.41-43 Generally, ferrous (Fe2+) salts are preferred to ferric (Fe3+) salts, as the former is more readily absorbed through the duodenal mucosa44 and is the more common formulation in commercially available supplements in the United States.45 Oral supplementation with ferrous sulfate 325 mg (65 mg elemental iron) tablets is the first-line therapy for iron deficiency anemia.1 Alternatively, ferrous gluconate 324 mg (38 mg elemental iron) over-the-counter and its liquid form has demonstrated superior absorption compared to ferrous sulfate tablets in a clinical study with peritoneal dialysis patients.1,46 One study suggested that oral iron 40 to 80 mg should be taken every other day to increase absorption.47 Due to improved bioavailability, intravenous iron may be utilized in patients with malabsorption, renal failure, or intolerance to oral iron (including those with gastric ulcers or active inflammatory bowel disease), with the formulation chosen based on underlying comorbidities and potential risks.1,48 The theoretical risk for potentiating bacterial growth by increasing the amount of unbound iron in the blood raises concerns of iron supplementation in patients with infection or sepsis. Although far from definitive, existing data suggest that risk for infection is greater with intravenous iron supplementation and should be carefully considered prior to use.49,50Elevated Ferritin—Elevated ferritin may be difficult to interpret given the multitude of conditions that can cause it.23,51,52 Elevated serum ferritin can be broadly characterized by increased synthesis due to iron overload, increased synthesis due to inflammation, or increased ferritin release from cellular damage.34 Further complicating interpretation is the potential diurnal fluctuations in serum iron levels dependent on dietary intake and timing of laboratory evaluation, choice of assay, differences in reference standards, and variations in calibration procedures that can lead to analytic variability in the measurement of ferritin.23,53,54

Among healthy patients, serum ferritin is directly proportional to iron status.9,51 A study utilizing weekly phlebotomy of 22 healthy participants to measure serum ferritin and calculate mobilizable storage iron found a strong positive correlation between the 2 variables (r=0.83, P<.001), with each 1-μg/L increase of serum ferritin corresponding to approximately an 8-mg increase of storage iron; the initial serum ferritin values ranged from 2 to 83 μg/L in females and 36 to 224 μg/L in males.55 The correlation of ferritin with iron status also was supported by the significant correlation between the number of transfusions received in patients with transfusion-related iron overload and serum ferritin levels (r=0.89, P<.001), with an average increase of 60 μg/L per transfusion.51

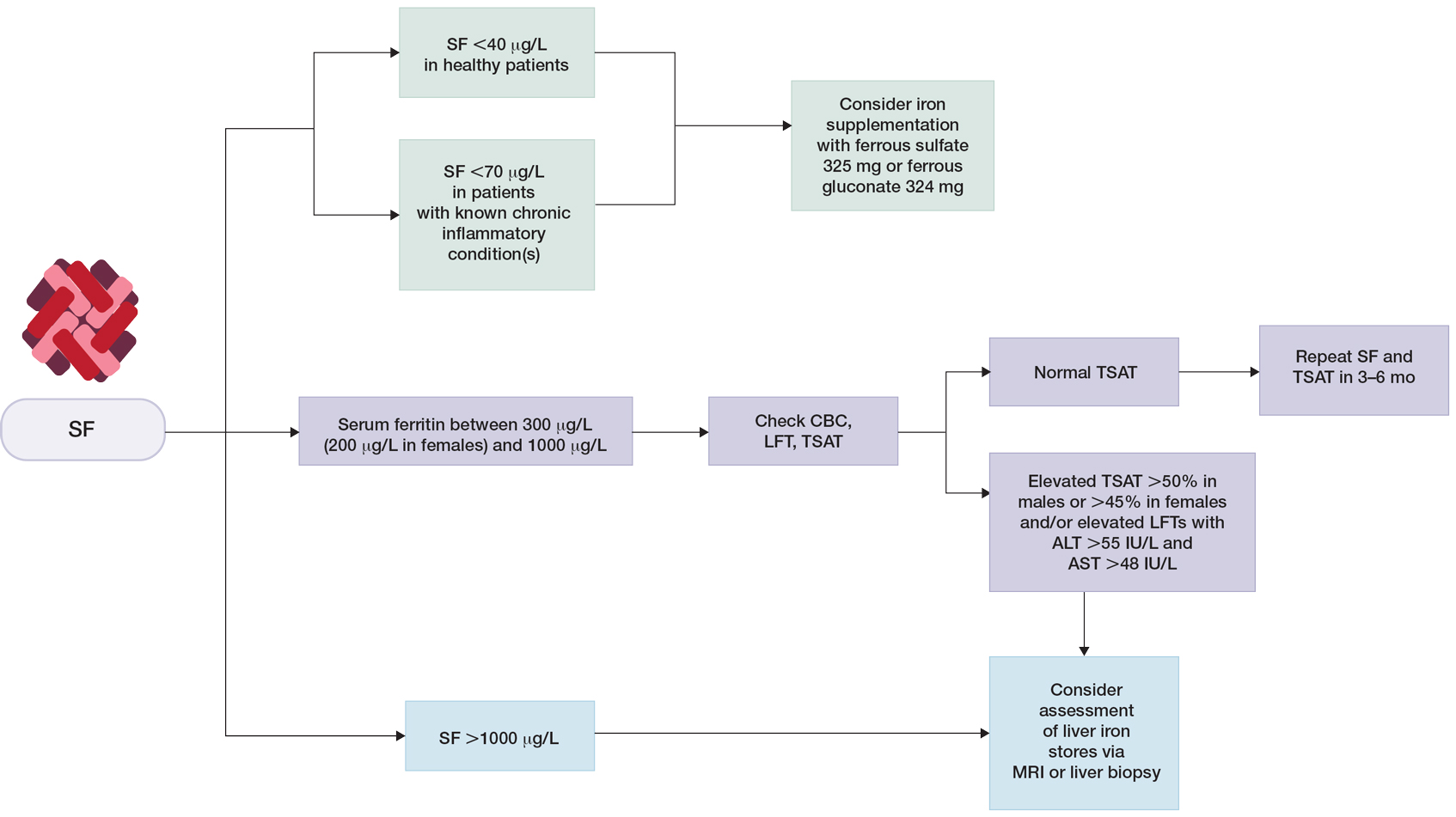

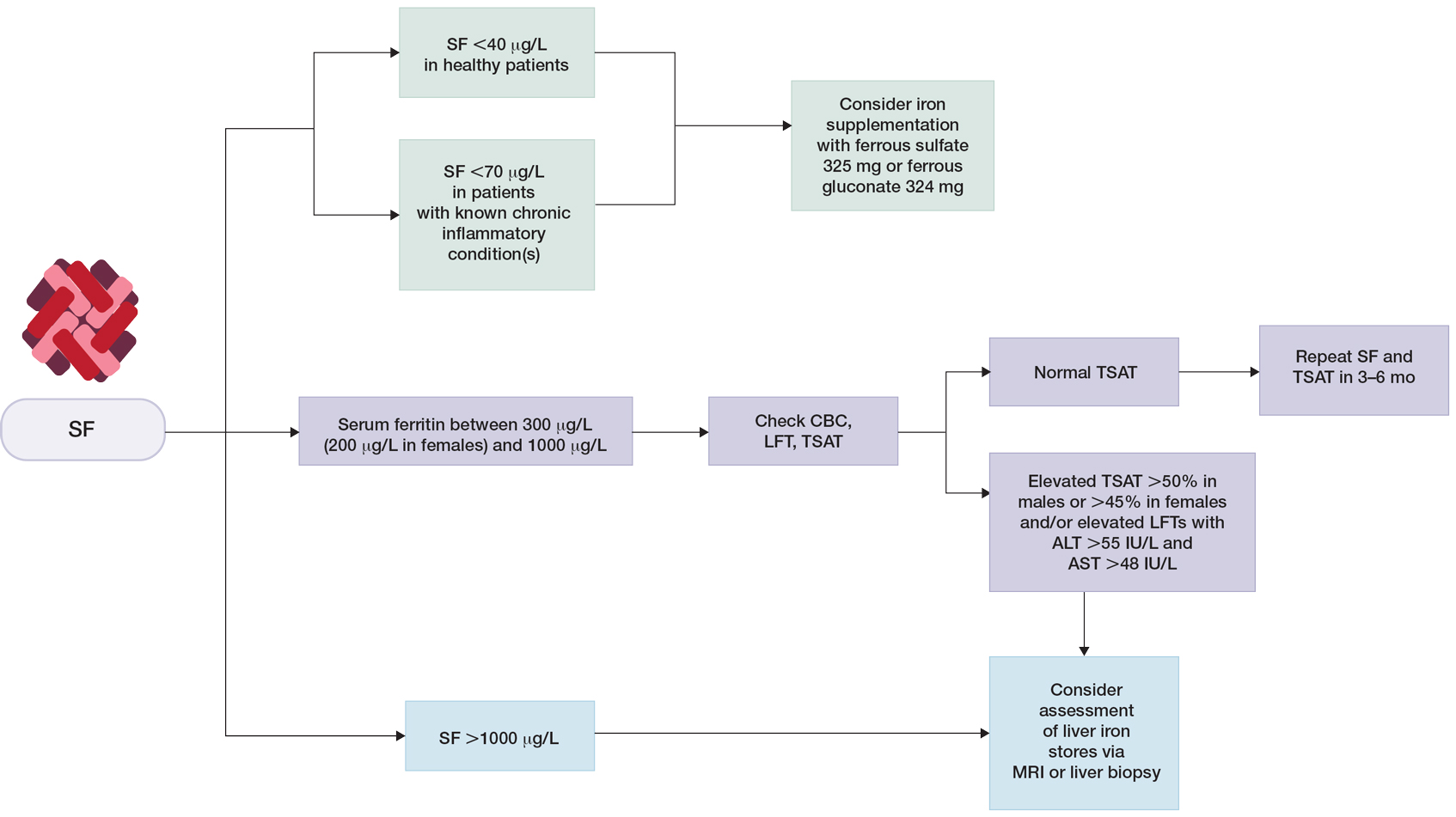

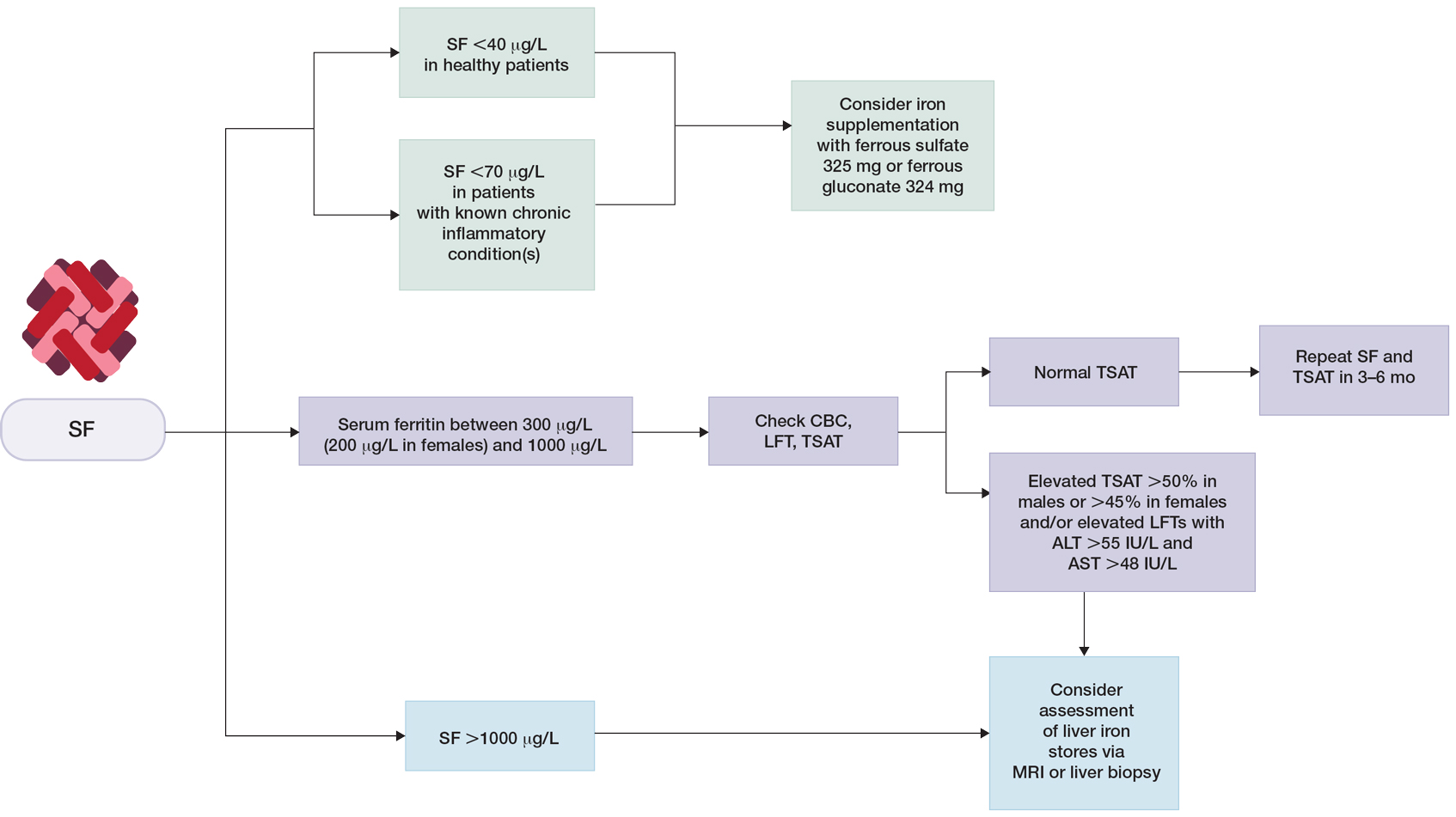

Clinical guidelines on the interpretation of serum ferritin levels by Cullis et al34 recommend a normal upper limit of 200 μg/L for healthy females and 300 μg/L for healthy males. Outside of clinical syndromes associated with iron overload, Lee and Means56 found that serum ferritin of 1000 μg/L or higher was a nonspecific marker of disease, including infection and/or neoplastic disorders. We have adapted these guidelines to propose a workflow for evaluation of serum ferritin levels (Figure). In patients with inflammatory conditions or those affected by metabolic syndrome, elevated serum ferritin does not correlate with body iron status.57,58 It is believed that inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1α, can upregulate ferritin synthesis independent of cellular iron stores.15,16 Several studies have examined the relationship between insulin resistance and/or metabolic syndrome with serum ferritin levels.31,32 Han et al32 found that elevated serum ferritin was significantly associated with higher risk for metabolic syndrome in men (P<.0001) but not in women.

Although cutaneous manifestations of iron overload can be seen as skin hyperpigmentation due to increased iron deposits and increased melanin production,22 the effects of elevated ferritin on the skin and hair are not well known. Iron overload is a known trigger of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT),59 a condition in which reduced or absent enzymatic activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) leads to build up of toxic porphyrins in various organs.60 In the skin, PCT manifests as a blistering photosensitive eruption that may resolve as dyspigmentation, scarring, and milia.61 Phlebotomy is first-line therapy in PCT to reduce serum iron and subsequent formation of UROD inhibitors, with guidelines suggesting discontinuation of phlebotomy when serum ferritin levels reach 20 ng/mL or lower.60 Hyperferritinemia (serum ferritin >500 μg/L) is a common finding in several inflammatory disorders often accompanied by clinically apparent cutaneous symptoms such as adult-onset Still disease,62 hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis,63,64 and anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 dermatomyositis.65 Among these conditions, serum ferritin levels have been reported to correlate with disease activity, raising the question of whether ferritin is a bystander or a driver of the underlying pathology.62,66,67 However, rapid decline of serum ferritin levels with treatment and control of inflammatory cytokines suggest that ferritin is unlikely to contribute to pathology.62,67

Final Thoughts

Many clinical studies have examined the association between hair health and body iron status, the collective findings of which suggest that iron deficiency may be associated with TE. Among commonly measured serum iron parameters, low ferritin is a highly specific and sensitive marker for diagnosing iron deficiency. Serum ferritin may be a clinically useful tool for ruling out underlying iron deficiency in patients presenting with hair loss. Despite advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of ferritin synthesis and regulation, whether ferritin itself contributes to cutaneous pathology is poorly understood.35,36,68-74 For patients who are otherwise healthy with low suspicion for inflammatory disorders, chronic systemic illnesses, or malignancy, serum ferritin can be used as an indicator of body iron status. The workup for slightly elevated serum ferritin should be interpreted in the context of other laboratory findings and should be reassessed over time. Serum ferritin levels above 1000 μg/L warrant further investigation into causes such as iron overload conditions and underlying inflammatory conditions or malignancy.

- Hoffman M, Micheletti RG, Shields BE. Nutritional dermatoses in the hospitalized patient. Cutis. 2020;105:296, 302-308, E1-E5.

- Ganz T. Macrophages and systemic iron homeostasis. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:446-453. doi:10.1159/000336423

- Slusarczyk P, Mandal PK, Zurawska G, et al. Impaired iron recycling from erythrocytes is an early hallmark of aging. eLife. 2023;12:E79196. doi:10.7554/eLife.79196

- Crichton RR. Ferritin: structure, synthesis and function. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1413-1422. doi:10.1056/nejm197106242842506

- Sandnes M, Ulvik RJ, Vorland M, et al. Hyperferritinemia—a clinical overview. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2008. doi:10.3390/jcm10092008

- Kernan KF, Carcillo JA. Hyperferritinemia and inflammation. Int Immunol. 2017;29:401-409. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxx031

- Wright JA, Richards T, Srai SKS. The role of iron in the skin and cutaneous wound healing. review. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:156. doi:10.3389/fphar.2014.00156

- Ems T, St Lucia K, Huecker MR. Biochemistry, iron absorption. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Crichton RR. Ferritin: structure, synthesis and function. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1413-1422. doi:10.1056/nejm197106242842506

- Cohen LA, Gutierrez L, Weiss A, et al. Serum ferritin is derived primarily from macrophages through a nonclassical secretory pathway. Blood. 2010;116:1574-1584. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-11-253815

- Briat JF, Ravet K, Arnaud N, et al. New insights into ferritin synthesis and function highlight a link between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in plants. Ann Bot. 2010;105:811-822. doi:10.1093/aob/mcp128

- Kato J, Kobune M, Ohkubo S, et al. Iron/IRP-1-dependent regulation of mRNA expression for transferrin receptor, DMT1 and ferritin during human erythroid differentiation. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:879-887. doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2007.03.005

- Gozzelino R, Soares MP. Coupling heme and iron metabolism via ferritin H chain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1754-1769. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5666

- Torti FM, Torti SV. Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood. 2002;99:3505-3516. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.10.3505

- Torti SV, Kwak EL, Miller SC, et al. The molecular cloning and characterization of murine ferritin heavy chain, a tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12638-12644.

- Wei Y, Miller SC, Tsuji Y, et al. Interleukin 1 induces ferritin heavy chain in human muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169:289-296. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(90)91466-6

- Bissett DL, Chatterjee R, Hannon DP. Chronic ultraviolet radiation–induced increase in skin iron and the photoprotective effect of topically applied iron chelators. Photochem Photobiol. 1991;54:215-223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb02009.x

- Pourzand C, Watkin RD, Brown JE, et al. Ultraviolet A radiation induces immediate release of iron in human primary skin fibroblasts: the role of ferritin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6751-6756. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.12.6751

- Applegate LA, Scaletta C, Panizzon R, et al. Evidence that ferritin is UV inducible in human skin: part of a putative defense mechanism. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:159-163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00254.x

- Wesselius LJ, Nelson ME, Skikne BS. Increased release of ferritin and iron by iron-loaded alveolar macrophages in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:690-695. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087339

- De Domenico I, Ward DM, Kaplan J. Specific iron chelators determine the route of ferritin degradation. Blood. 2009;114:4546-4551. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-05-224188

- Knovich MA, Storey JA, Coffman LG, et al. Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 2009;23:95-104. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2008.08.001

- Dignass A, Farrag K, Stein J. Limitations of serum ferritin in diagnosing iron deficiency in inflammatory conditions. Int J Chronic Dis. 2018;2018:9394060. doi:10.1155/2018/9394060

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000124

- Finch CA, Bellotti V, Stray S, et al. Plasma ferritin determination as a diagnostic tool. West J Med. 1986;145:657-663.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Ali M, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:145-153. doi:10.1007/BF02598003

- Punnonen K, Irjala K, Rajamäki A. Serum transferrin receptor and its ratio to serum ferritin in the diagnosis of iron deficiency. Blood. 1997;89:1052-1057. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V89.3.1052

- Zacharski LR, Ornstein DL, Woloshin S, et al. Association of age, sex, and race with body iron stores in adults: analysis of NHANES III data. American Heart Journal. 2000;140:98-104. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhj.2000.106646

- Milman N, Kirchhoff M. Iron stores in 1359, 30- to 60-year-old Danish women: evaluation by serum ferritin and hemoglobin. Ann Hematol. 1992;64:22-27. doi:10.1007/bf01811467

- Liu J-M, Hankinson SE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Body iron stores and their determinants in healthy postmenopausal US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1160-1167. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1160

- Kim C, Nan B, Kong S, et al. Changes in iron measures over menopause and associations with insulin resistance. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21:872-877. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.3549

- Han LL, Wang YX, Li J, et al. Gender differences in associations of serum ferritin and diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity in the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:2189-2195. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201400088

- Pan Y, Jackson RT. Insights into the ethnic differences in serum ferritin between black and white US adult men. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:406-416. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20745

- Cullis JO, Fitzsimons EJ, Griffiths WJ, et al. Investigation and management of a raised serum ferritin. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:331-340. doi:10.1111/bjh.15166

- Moeinvaziri M, Mansoori P, Holakooee K, et al. Iron status in diffuse telogen hair loss among women. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:279-284.

- Tamer F, Yuksel ME, Karabag Y. Serum ferritin and vitamin D levels should be evaluated in patients with diffuse hair loss prior to treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37:407-411. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.96251

- Olsen EA, Reed KB, Cacchio PB, et al. Iron deficiency in female pattern hair loss, chronic telogen effluvium, and control groups. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:991-999. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.006

- Asghar F, Shamim N, Farooque U, et al. Telogen effluvium: a review of the literature. Cureus. 2020;12:E8320. doi:10.7759/cureus.8320

- Brough KR, Torgerson RR. Hormonal therapy in female pattern hair loss. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:53-57. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.01.001

- Klein EJ, Karim M, Li X, et al. Supplementation and hair growth: a retrospective chart review of patients with alopecia and laboratory abnormalities. JAAD Int. 2022;9:69-71. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.08.013

- Goksin S. Retrospective evaluation of clinical profile and comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata. North Clin Istanb. 2022;9:451-458. doi:10.14744/nci.2022.78790

- Beatrix J, Piales C, Berland P, et al. Non-anemic iron deficiency: correlations between symptoms and iron status parameters. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022;76:835-840. doi:10.1038/s41430-021-01047-5

- Treister-Goltzman Y, Yarza S, Peleg R. Iron deficiency and nonscarring alopecia in women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:83-92. doi:10.1159/000519952

- Santiago P. Ferrous versus ferric oral iron formulations for the treatment of iron deficiency: a clinical overview. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:846824. doi:10.1100/2012/846824

- Lo JO, Benson AE, Martens KL, et al. The role of oral iron in the treatment of adults with iron deficiency. Eur J Haematol. 2023;110:123-130. doi:10.1111/ejh.13892

- Lausevic´ M, Jovanovic´ N, Ignjatovic´ S, et al. Resorption and tolerance of the high doses of ferrous sulfate and ferrous gluconate in the patients on peritoneal dialysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2006;63:143-147. doi:10.2298/vsp0602143l

- Stoffel NU, Zeder C, Brittenham GM, et al. Iron absorption from supplements is greater with alternate day than with consecutive day dosing in iron-deficient anemic women. Haematologica. 2020;105:1232-1239. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.220830

- Jimenez KM, Gasche C. Management of iron deficiency anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Haematologica. 2019;142:30-36. doi:10.1159/000496728

- Shah AA, Donovan K, Seeley C, et al. Risk of infection associated with administration of intravenous iron: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E2133935-E2133935. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33935

- Ganz T, Aronoff GR, Gaillard CAJM, et al. Iron administration, infection, and anemia management in ckd: untangling the effects of intravenous iron therapy on immunity and infection risk. Kidney Med. 2020/05/01/ 2020;2:341-353. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.01.006

- Lipschitz DA, Cook JD, Finch CA. A clinical evaluation of serum ferritin as an index of iron stores. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:1213-1216. doi:10.1056/nejm197405302902201

- Loveikyte R, Bourgonje AR, van der Reijden JJ, et al. Hepcidin and iron status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing induction therapy with vedolizumab or infliximab [published online February 7, 2023]. Inflamm Bowel Dis. doi:10.1093/ibd/izad010

- Borel MJ, Smith SM, Derr J, et al. Day-to-day variation in iron-status indices in healthy men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:729-735. doi:10.1093/ajcn/54.4.729

- Ford BA, Coyne DW, Eby CS, et al. Variability of ferritin measurements in chronic kidney disease; implications for iron management. Kidney International. 2009;75:104-110. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.526

- Walters GO, Miller FM, Worwood M. Serum ferritin concentration and iron stores in normal subjects. J Clin Pathol. 1973;26:770-772. doi:10.1136/jcp.26.10.770

- Lee MH, Means RT Jr. Extremely elevated serum ferritin levels in a university hospital: associated diseases and clinical significance. Am J Med. Jun 1995;98:566-571. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80015-1

- Theil EC. Ferritin: structure, gene regulation, and cellular function in animals, plants, and microorganisms. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:289-315. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001445

- Chen LY, Chang SD, Sreenivasan GM, et al. Dysmetabolic hyperferritinemia is associated with normal transferrin saturation, mild hepatic iron overload, and elevated hepcidin. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:139-143. doi:10.1007/s00277-010-1050-x

- Sampietro M, Fiorelli G, Fargion S. Iron overload in porphyria cutanea tarda. Haematologica. 1999;84:248-253.

- Singal AK. Porphyria cutanea tarda: recent update. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128:271-281. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.01.004

- Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:735-745. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.002

- Mehta B, Efthimiou P. Ferritin in adult-onset Still’s disease: just a useful innocent bystander? Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:298405. doi:10.1155/2012/298405

- Ma AD, Fedoriw YD, Roehrs P. Hyperferritinemia and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. single institution experience in adult and pediatric patients. Blood. 2012;120:2135-2135. doi:10.1182/blood.V120.21.2135.2135

- Basu S, Maji B, Barman S, et al. Hyperferritinemia in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a single institution experience in pediatric patients. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2018;33:108-112. doi:10.1007/s12291-017-0655-4

- Yamada K, Asai K, Okamoto A, et al. Correlation between disease activity and serum ferritin in clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapidly-progressive interstitial lung disease: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:34. doi:10.1186/s13104-018-3146-7

- Zohar DN, Seluk L, Yonath H, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive dermatomyositis associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and correlation between serum ferritin level and treatment response. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2020;31:75-77. doi:10.31138/mjr.31.1.75

- Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, et al. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:154-155. doi:10.1002/pbc.22774

- Bregy A, Trueb RM. No association between serum ferritin levels >10 microg/l and hair loss activity in women. Dermatology. 2008;217:1-6. doi:10.1159/000118505

- de Queiroz M, Vaske TM, Boza JC. Serum ferritin and vitamin D levels in women with non-scarring alopecia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:2688-2690. doi:10.1111/jocd.14472

- El-Husseiny R, Alrgig NT, Abdel Fattah NSA. Epidemiological and biochemical factors (serum ferritin and vitamin D) associated with premature hair graying in Egyptian population. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1860-1866. doi:10.1111/jocd.13747

- Enitan AO, Olasode OA, Onayemi EO, et al. Serum ferritin levels amongst individuals with androgenetic alopecia in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2022;39:1026-1031.

- I˙bis¸ S, Aksoy Sarac¸ G, Akdag˘ T. Evaluation of MCV/RDW ratio and correlations with ferritin in telogen effluvium patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:E2022151. doi:10.5826/dpc.1203a151

- Kakpovbia E, Ogbechie-Godec OA, Shapiro J, et al. Laboratory testing in telogen effluvium. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:110-111. doi:10.36849/jdd.5771

- Rasheed H, Mahgoub D, Hegazy R, et al. Serum ferritin and vitamin D in female hair loss: do they play a role? Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;26:101-107. doi:10.1159/000346698

Ferritin is an iron storage protein crucial to human iron homeostasis. Because serum ferritin levels are in dynamic equilibrium with the body’s iron stores, ferritin often is measured as a reflection of iron status; however, ferritin also is an acute-phase reactant whose levels may be nonspecifically elevated in a wide range of inflammatory conditions. The various processes that alter serum ferritin levels complicate the clinical interpretation of this laboratory value. In this article, we review the structure and function of ferritin and provide a guide for clinical use.

Overview of Iron

Iron is an essential element of key biologic functions including DNA synthesis and repair, oxygen transport, and oxidative phosphorylation. The body’s iron stores are mainly derived from internal iron recycling following red blood cell breakdown, while 5% to 10% is supplied by dietary intake.1-3 Iron metabolism is of particular importance in cells of the reticuloendothelial system (eg, spleen, liver, bone marrow), where excess iron must be appropriately sequestered and from which iron can be mobilized.4 Sufficient iron stores are necessary for proper cellular function and survival, as iron is a necessary component of hemoglobin for oxygen delivery, iron-sulfur clusters in electron transport, and enzyme cofactors in other cellular processes.

Although labile pools of biologically active free iron exist in limited amounts within cells, excess free iron can generate free radicals that damage cellular proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.5-7 As such, most intracellular iron is captured within ferritin molecules. The excretion of iron is unregulated and occurs through loss in sweat, menstruation, hair shedding, skin desquamation, and enterocyte turnover.8 The lack of regulated excretion highlights the need for a tightly regulated system of uptake, transportation, storage, and sequestration to maintain iron homeostasis.

Overview of Ferritin Structure and Function

Ferritin is a key regulator of iron homeostasis that also serves as an important clinical indicator of body iron status. Ferritin mainly is found as an intracellular cytosolic iron storage and detoxification protein structured as a hollow 24-subunit polymer shell that can sequester up to 4500 atoms of iron within its core.9,10 The 24-mer is composed of both ferritin L (FTL) and ferritin H (FTH) subunits, with dynamic regulation of the H:L ratio dependent on the context and tissue in which ferritin is found.6

Ferritin H possesses ferroxidase, which facilitates oxidation of ferrous (Fe2+) iron into ferric (Fe3+) iron, which can then be incorporated into the mineral core of the ferritin heteropolymer.11 Ferritin L is more abundant in the spleen and liver, while FTH is found predominantly in the heart and kidneys where the increased ferroxidase activity may confer an increased ability to oxidize Fe2+ and limit oxidative stress.6

Regulation of Ferritin Synthesis and Secretion

Ferritin synthesis is regulated by intracellular nonheme iron levels, governed mainly by an iron response element (IRE) and iron response protein (IRP) translational repression system. Both FTH and FTL messenger RNA (mRNA) contain an IRE that is a regulatory stem-loop structure in the 5´ untranslated region. When the IRE is bound by IRP1 or IRP2, mRNA translation of ferritin subunits is suppressed.6 In low iron conditions, IRPs have greater affinity for IRE, and binding suppresses ferritin translation.12 In high iron conditions, IRPs have a decreased affinity for IRE, and ferritin mRNA synthesis is increased.13 Additionally, inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1α transcriptionally induce FTH synthesis, resulting in an increased population of H-rich ferritins.11,14-16 A study using cultured human primary skin fibroblasts demonstrated UV radiation–induced increases in free intracellular iron content.17,18 Pourzand et al18 suggested that UV-mediated damage of lysosomal membranes results in leakage of lysosomal proteases into the cytosol, contributing to degradation of intracellular ferritin and subsequent release of iron within skin fibroblasts. The increased intracellular iron downregulates IRPs and increases ferritin mRNA synthesis,18 consistent with prior findings of increased ferritin synthesis in skin that is induced by UV radiation.19

Molecular analysis of serum ferritin in iron-overloaded mice revealed that extracellular ferritin found in the serum is composed of a greater fraction of FTL and has lower iron content than intracellular ferritin. The low iron content of serum ferritin compared with intracellular ferritin and transferrin suggests that serum ferritin is not a major pathway of systemic iron transport.10 However, locally secreted ferritins may play a greater role in iron transport and release in selected tissues. Additionally, in vitro studies of cell cultures from humans and mice have demonstrated the ability of macrophages to secrete ferritin, suggesting that macrophages are an important cellular source of serum ferritin.10,20 As such, serum ferritin generally may reflect body iron status but more specifically reflects macrophage iron status.10 Although the exact pathways of ferritin release are unknown, it is hypothesized that ferritin secretion occurs through cytosolic autophagy followed by secretion of proteins from the lysosomal compartment.10,18,21

Clinical Utility of Serum Ferritin

Low Ferritin and Iron Deficiency—Although bone marrow biopsy with iron staining remains the gold standard for diagnosis of iron deficiency, serum ferritin is a much more accessible and less invasive tool for evaluation of iron status. A serum ferritin level below 12 μg/L is highly specific for iron depletion,22 with a higher cutoff recommended in clinical practice to improve diagnostic sensitivity.23,24 Conditions independent of iron deficiency that may reduce serum ferritin include hypothyroidism and ascorbate deficiency, though neither condition has been reported to interfere with appropriate diagnosis of iron deficiency.25 Guyatt et al26 conducted a systematic review of laboratory tests used in the diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia and identified 55 studies suitable for inclusion. Based on an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.95, serum ferritin values were superior to transferrin saturation (AUROC, 0.74), red cell protoporphyrin (AUROC, 0.77), red cell volume distribution width (AUROC, 0.62), and mean cell volume (AUROC, 0.76) for diagnosis of IDA, verified by histologic examination of aspirated bone marrow.26 The likelihood ratio of iron deficiency begins to decrease for serum ferritin values of 40 μg/L or greater. For patients with inflammatory conditions—patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, inflammatory disease, infection, rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy—the likelihood of iron deficiency begins to decrease at serum ferritin levels of 70 μg/L or greater.26 Similarly, the World Health Organization recommends that in adults with infection or inflammation, serum ferritin levels lower than 70 μg/L may be used to indicate iron deficiency.24 A serum ferritin level of 41 μg/L or lower was found to have a sensitivity and specificity of 98% for discriminating between iron-deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease (diagnosed based on bone marrow biopsy with iron staining), with an AUROC of 0.98.27 As such, we recommend using a serum ferritin level of 40 μg/L or lower in patients who are otherwise healthy as an indicator of iron deficiency.

The threshold for iron supplementation may vary based on age, sex, and race. In women, ferritin levels increase during menopause and peak after menopause; ferritin levels are higher in men than in women.28-30 A multisite longitudinal cohort study of 70 women in the United States found that the mean (SD) ferritin valuewas 69.5 (81.7) μg/L premenopause and 128.8 (125.7) μg/L postmenopause (P<.01).31 A separate longitudinal survey study of 8564 patients in China found that the mean (SE) ferritin value was 201.55 (3.60) μg/L for men and 80.46 (1.64) μg/L for women (P<.0001).32 Analysis of serum ferritin levels of 3554 male patients from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrated that patients who self-reported as non-Hispanic Black (n=1616) had significantly higher serum ferritin levels than non-Hispanic White patients (n=1938)(serum ferritin difference of 37.1 μg/L)(P<.0001).33 The British Society for Haematology guidelines recommend that the threshold of serum ferritin for diagnosing iron deficiency should take into account age-, sex-, and race-based differences.34 Ferritin and Hair—Cutaneous manifestations of iron deficiency include koilonychia, glossitis, pruritus, angular cheilitis, and telogen effluvium (TE).1 A case-control study of 30 females aged 15 to 45 years demonstrated that the mean (SD) ferritin level was significantly lower in patients with TE than those with no hair loss (16.3 [12.6] ng/mL vs 60.3 [50.1] ng/mL; P<.0001). Using a threshold of 30 μg/L or lower, the investigators found that the odds ratio for TE was 21.0 (95% CI, 4.2-105.0) in patients with low serum ferritin.35

Another retrospective review of 54 patients with diffuse hair loss and 55 controls compared serum vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, zinc, ferritin, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels between the 2 groups.36 Exclusion criteria were clinical diagnoses of female pattern hair loss (androgenetic alopecia), pregnancy, menopause, metabolic and endocrine disorders, hormone replacement therapy, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy, vitamin and mineral supplementation, scarring alopecia, eating disorders, and restrictive diets. Compared with controls, patients with diffuse nonscarring hair loss were found to have significantly lower ferritin (mean [SD], 14.72 [10.70] ng/mL vs 25.30 [14.41] ng/mL; P<.001) and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels (mean [SD], 14.03 [8.09] ng/mL vs 17.01 [8.59] ng/mL; P=.01).36

In contrast, a separate case-control study of 381 cases and 76 controls found no increase in the rate of iron deficiency—defined as ferritin ≤15 μg/L or ≤40 μg/L—among women with female pattern hair loss or chronic TE vs controls.37 Taken together, these studies suggest that iron status may play a role in TE, a process that may result from nutritional deficiency, trauma, or physical or psychological stress38; however, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that low iron status impacts androgenetic alopecia, in which its multifactorial pathogenesis implicates genetic and hormonal factors.39 More research is needed to clarify the potential associations between iron deficiency and types of hair loss. Additionally, it is unclear whether iron supplementation improves hair growth parameters such as density and caliber.40