User login

What is the best beta-blocker for systolic heart failure?

Three beta-blockers—carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol—reduce mortality equally (by about 30% over one year) in patients with Class III or IV systolic heart failure. Insufficient evidence exists comparing equipotent doses of these medications head-to-head to recommend any one over the others (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review/meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 network meta-analysis compared beta-blockers with placebo or standard treatment by analyzing 21 randomized trials with a total of 23,122 patients.1 Investigators found that beta-blockers as a class significantly reduced mortality after a median of 12 months (odds ratio=0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64-0.80; number needed to treat [NNT]=23).

They also compared atenolol, bisoprolol, bucindolol, carvedilol, metoprolol, and nebivolol with each other and found no significant difference in risk of death, sudden cardiac death, death resulting from pump failure, or tolerability.

Three drugs are more effective and tolerable than others

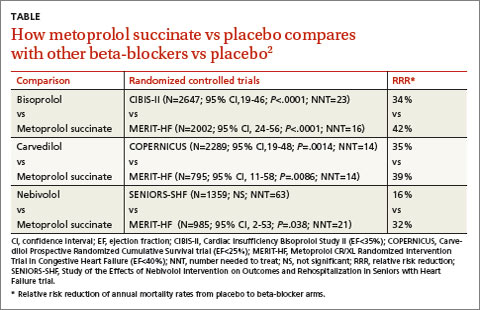

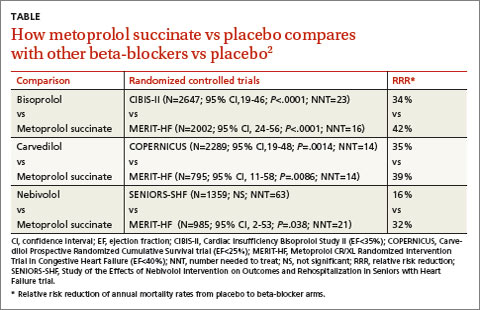

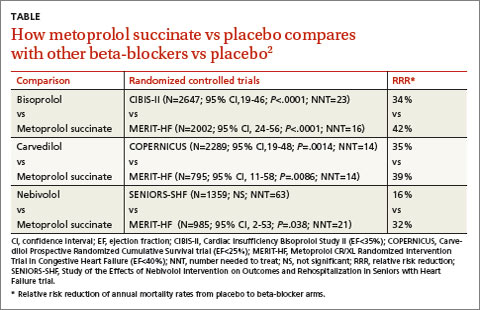

A 2013 stratified subset meta-analysis used data from landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated beta-blockers vs placebo in patients with systolic heart failure to compare metoprolol succinate (MERIT-HF) vs placebo with bisoprolol (CIBIS-II), carvedilol (COPERNICUS), and nebivolol (SENIORS-SHF) vs placebo (TABLE).2

Three of the drugs—bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol succinate—showed similar reductions relative to placebo in all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, and tolerability. Investigators concluded that the 3 drugs have comparable efficacy and tolerability, whereas nebivolol is less effective and tolerable.

Carvedilol vs beta-1-selective beta-blockers

Another 2013 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs with 4563 adult patients 18 years or older with systolic heart failure compared carvedilol with the beta-1-selective beta-blockers atenolol, bisoprolol, nebivolol, and metoprolol.3 Investigators found that carvedilol significantly reduced all-cause mortality (relative risk=0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT=23) compared with beta-1-selective beta-blockers.

However, 4 trials (including COMET, N=3029) compared carvedilol with short-acting metoprolol tartrate, which may have skewed results in favor of carvedilol. Moreover, 2 trials comparing carvedilol with bisoprolol and 2 trials comparing carvedilol with nebivolol found no significant difference in all-cause mortality.3

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2010 Heart Failure Society of America Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline notes that the marked beneficial effects of beta blockade with carvedilol, bisoprolol, and controlled- or extended-release metoprolol have been well-demonstrated in large-scale clinical trials of symptomatic patients with Class II to IV heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.4

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association heart failure guideline recommends the use of one of the 3 beta-blockers proven to reduce mortality (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or sustained-release metoprolol succinate) for all patients with current or previous symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality.5

1. Chatterjee S, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, et al. Benefits of b blockers in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f55.

2. Wikstrand J, Wedel H, Castagno D, et al. The large-scale placebo-controlled beta-blocker studies in systolic heart failure revisited: results from CIBIS-II, COPERNICUS and SENIORS-SHF compared with stratified subsets from MERIT-HF. J Intern Med. 2014;275:134-143.

3. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, et al. Meta-analysis of carvedilol versus beta 1 selective beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:765-769.

4. Heart Failure Society of America. Executive summary: HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16:475-539.

5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327.

Three beta-blockers—carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol—reduce mortality equally (by about 30% over one year) in patients with Class III or IV systolic heart failure. Insufficient evidence exists comparing equipotent doses of these medications head-to-head to recommend any one over the others (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review/meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 network meta-analysis compared beta-blockers with placebo or standard treatment by analyzing 21 randomized trials with a total of 23,122 patients.1 Investigators found that beta-blockers as a class significantly reduced mortality after a median of 12 months (odds ratio=0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64-0.80; number needed to treat [NNT]=23).

They also compared atenolol, bisoprolol, bucindolol, carvedilol, metoprolol, and nebivolol with each other and found no significant difference in risk of death, sudden cardiac death, death resulting from pump failure, or tolerability.

Three drugs are more effective and tolerable than others

A 2013 stratified subset meta-analysis used data from landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated beta-blockers vs placebo in patients with systolic heart failure to compare metoprolol succinate (MERIT-HF) vs placebo with bisoprolol (CIBIS-II), carvedilol (COPERNICUS), and nebivolol (SENIORS-SHF) vs placebo (TABLE).2

Three of the drugs—bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol succinate—showed similar reductions relative to placebo in all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, and tolerability. Investigators concluded that the 3 drugs have comparable efficacy and tolerability, whereas nebivolol is less effective and tolerable.

Carvedilol vs beta-1-selective beta-blockers

Another 2013 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs with 4563 adult patients 18 years or older with systolic heart failure compared carvedilol with the beta-1-selective beta-blockers atenolol, bisoprolol, nebivolol, and metoprolol.3 Investigators found that carvedilol significantly reduced all-cause mortality (relative risk=0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT=23) compared with beta-1-selective beta-blockers.

However, 4 trials (including COMET, N=3029) compared carvedilol with short-acting metoprolol tartrate, which may have skewed results in favor of carvedilol. Moreover, 2 trials comparing carvedilol with bisoprolol and 2 trials comparing carvedilol with nebivolol found no significant difference in all-cause mortality.3

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2010 Heart Failure Society of America Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline notes that the marked beneficial effects of beta blockade with carvedilol, bisoprolol, and controlled- or extended-release metoprolol have been well-demonstrated in large-scale clinical trials of symptomatic patients with Class II to IV heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.4

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association heart failure guideline recommends the use of one of the 3 beta-blockers proven to reduce mortality (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or sustained-release metoprolol succinate) for all patients with current or previous symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality.5

Three beta-blockers—carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol—reduce mortality equally (by about 30% over one year) in patients with Class III or IV systolic heart failure. Insufficient evidence exists comparing equipotent doses of these medications head-to-head to recommend any one over the others (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review/meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 network meta-analysis compared beta-blockers with placebo or standard treatment by analyzing 21 randomized trials with a total of 23,122 patients.1 Investigators found that beta-blockers as a class significantly reduced mortality after a median of 12 months (odds ratio=0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64-0.80; number needed to treat [NNT]=23).

They also compared atenolol, bisoprolol, bucindolol, carvedilol, metoprolol, and nebivolol with each other and found no significant difference in risk of death, sudden cardiac death, death resulting from pump failure, or tolerability.

Three drugs are more effective and tolerable than others

A 2013 stratified subset meta-analysis used data from landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated beta-blockers vs placebo in patients with systolic heart failure to compare metoprolol succinate (MERIT-HF) vs placebo with bisoprolol (CIBIS-II), carvedilol (COPERNICUS), and nebivolol (SENIORS-SHF) vs placebo (TABLE).2

Three of the drugs—bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol succinate—showed similar reductions relative to placebo in all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, and tolerability. Investigators concluded that the 3 drugs have comparable efficacy and tolerability, whereas nebivolol is less effective and tolerable.

Carvedilol vs beta-1-selective beta-blockers

Another 2013 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs with 4563 adult patients 18 years or older with systolic heart failure compared carvedilol with the beta-1-selective beta-blockers atenolol, bisoprolol, nebivolol, and metoprolol.3 Investigators found that carvedilol significantly reduced all-cause mortality (relative risk=0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT=23) compared with beta-1-selective beta-blockers.

However, 4 trials (including COMET, N=3029) compared carvedilol with short-acting metoprolol tartrate, which may have skewed results in favor of carvedilol. Moreover, 2 trials comparing carvedilol with bisoprolol and 2 trials comparing carvedilol with nebivolol found no significant difference in all-cause mortality.3

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2010 Heart Failure Society of America Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline notes that the marked beneficial effects of beta blockade with carvedilol, bisoprolol, and controlled- or extended-release metoprolol have been well-demonstrated in large-scale clinical trials of symptomatic patients with Class II to IV heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.4

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association heart failure guideline recommends the use of one of the 3 beta-blockers proven to reduce mortality (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or sustained-release metoprolol succinate) for all patients with current or previous symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality.5

1. Chatterjee S, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, et al. Benefits of b blockers in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f55.

2. Wikstrand J, Wedel H, Castagno D, et al. The large-scale placebo-controlled beta-blocker studies in systolic heart failure revisited: results from CIBIS-II, COPERNICUS and SENIORS-SHF compared with stratified subsets from MERIT-HF. J Intern Med. 2014;275:134-143.

3. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, et al. Meta-analysis of carvedilol versus beta 1 selective beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:765-769.

4. Heart Failure Society of America. Executive summary: HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16:475-539.

5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327.

1. Chatterjee S, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, et al. Benefits of b blockers in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f55.

2. Wikstrand J, Wedel H, Castagno D, et al. The large-scale placebo-controlled beta-blocker studies in systolic heart failure revisited: results from CIBIS-II, COPERNICUS and SENIORS-SHF compared with stratified subsets from MERIT-HF. J Intern Med. 2014;275:134-143.

3. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, et al. Meta-analysis of carvedilol versus beta 1 selective beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:765-769.

4. Heart Failure Society of America. Executive summary: HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16:475-539.

5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

February 2015 Quiz 1

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cough is considered to be one of the atypical manifestations of reflux disease. The mechanisms include regurgitation with tracheal aspiration of gastric content, but also triggering of reflex bronchial reactivity with small amounts of acid in the distal esophagus in predisposed individuals. However, environmental allergens, postnasal drip, and airway disorders can also trigger chronic cough. Upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies may demonstrate reflux esophagitis, but this does not establish whether cough is triggered by reflux events. A solid bolus barium swallow is useful in the evaluation of esophageal dysphagia. Impedance planimetry assesses biomechanical properties of the esophageal wall, and does not help assess the role of reflux in chronic cough. Esophageal high-resolution manometry will demonstrate esophageal motor patterns, but does not determine causality of chronic cough. Wireless pH testing off PPI therapy has the potential to determine whether cough events correlate with acidic reflux events. Some investigators have combined this with a cough monitor that can precisely time cough events, allowing for more accurate assessments of the association between cough and reflux events.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cough is considered to be one of the atypical manifestations of reflux disease. The mechanisms include regurgitation with tracheal aspiration of gastric content, but also triggering of reflex bronchial reactivity with small amounts of acid in the distal esophagus in predisposed individuals. However, environmental allergens, postnasal drip, and airway disorders can also trigger chronic cough. Upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies may demonstrate reflux esophagitis, but this does not establish whether cough is triggered by reflux events. A solid bolus barium swallow is useful in the evaluation of esophageal dysphagia. Impedance planimetry assesses biomechanical properties of the esophageal wall, and does not help assess the role of reflux in chronic cough. Esophageal high-resolution manometry will demonstrate esophageal motor patterns, but does not determine causality of chronic cough. Wireless pH testing off PPI therapy has the potential to determine whether cough events correlate with acidic reflux events. Some investigators have combined this with a cough monitor that can precisely time cough events, allowing for more accurate assessments of the association between cough and reflux events.

ANSWER: D

Critique

Cough is considered to be one of the atypical manifestations of reflux disease. The mechanisms include regurgitation with tracheal aspiration of gastric content, but also triggering of reflex bronchial reactivity with small amounts of acid in the distal esophagus in predisposed individuals. However, environmental allergens, postnasal drip, and airway disorders can also trigger chronic cough. Upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies may demonstrate reflux esophagitis, but this does not establish whether cough is triggered by reflux events. A solid bolus barium swallow is useful in the evaluation of esophageal dysphagia. Impedance planimetry assesses biomechanical properties of the esophageal wall, and does not help assess the role of reflux in chronic cough. Esophageal high-resolution manometry will demonstrate esophageal motor patterns, but does not determine causality of chronic cough. Wireless pH testing off PPI therapy has the potential to determine whether cough events correlate with acidic reflux events. Some investigators have combined this with a cough monitor that can precisely time cough events, allowing for more accurate assessments of the association between cough and reflux events.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

- Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut 2005;54:449–54.

- Smith J, Woodcock A, Houghton L. New developments in reflux-associated cough. Lung 2010;188(Suppl1)S81-6.

- Sifrim D, Barnes N. GERD related chronic cough: How to identify patients who will respond to antireflux therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44:234-6.

February 2015 Quiz 2

ANSWER: C

Critique

The diagnosis of H. pylori may be made using either invasive or noninvasive methods. Invasive diagnostic methods either detect organisms directly (i.e., histological identification with appropriate stains or bacterial culture) or indirectly (i.e., rapid urease testing of biopsy specimens). Noninvasive methods include serum antibody, stool antigen, and detecting the metabolites of the bacterial enzyme urease (i.e., urea breath testing). It should be noted that serology should not be used to test for eradication as the antibodies may remain elevated for years after successful eradication therapy.

Treatment of H. pylori infection has become problematic recently primarily because of increasing antibiotic resistance. The eradication rate of standard triple therapy consisting of a PPI combined with clarithromycin (500 mg) and amoxicillin (1 g) (or metronidazole (500 mg)), all given b.i.d. for 7-14 days has now declined to unacceptable levels, averaging 70%-80% but reported to be as low as 55%. It is currently recommended that a noninvasive method be used (other than serology) to confirm eradication in patients in whom eradication is deemed necessary.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2012;61:646-64.

- De F, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Lerardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-14.

- Kearney DJ, Brousal A. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice in the United States – Results from 224 patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000;45:265-71.

ANSWER: C

Critique

The diagnosis of H. pylori may be made using either invasive or noninvasive methods. Invasive diagnostic methods either detect organisms directly (i.e., histological identification with appropriate stains or bacterial culture) or indirectly (i.e., rapid urease testing of biopsy specimens). Noninvasive methods include serum antibody, stool antigen, and detecting the metabolites of the bacterial enzyme urease (i.e., urea breath testing). It should be noted that serology should not be used to test for eradication as the antibodies may remain elevated for years after successful eradication therapy.

Treatment of H. pylori infection has become problematic recently primarily because of increasing antibiotic resistance. The eradication rate of standard triple therapy consisting of a PPI combined with clarithromycin (500 mg) and amoxicillin (1 g) (or metronidazole (500 mg)), all given b.i.d. for 7-14 days has now declined to unacceptable levels, averaging 70%-80% but reported to be as low as 55%. It is currently recommended that a noninvasive method be used (other than serology) to confirm eradication in patients in whom eradication is deemed necessary.

ANSWER: C

Critique

The diagnosis of H. pylori may be made using either invasive or noninvasive methods. Invasive diagnostic methods either detect organisms directly (i.e., histological identification with appropriate stains or bacterial culture) or indirectly (i.e., rapid urease testing of biopsy specimens). Noninvasive methods include serum antibody, stool antigen, and detecting the metabolites of the bacterial enzyme urease (i.e., urea breath testing). It should be noted that serology should not be used to test for eradication as the antibodies may remain elevated for years after successful eradication therapy.

Treatment of H. pylori infection has become problematic recently primarily because of increasing antibiotic resistance. The eradication rate of standard triple therapy consisting of a PPI combined with clarithromycin (500 mg) and amoxicillin (1 g) (or metronidazole (500 mg)), all given b.i.d. for 7-14 days has now declined to unacceptable levels, averaging 70%-80% but reported to be as low as 55%. It is currently recommended that a noninvasive method be used (other than serology) to confirm eradication in patients in whom eradication is deemed necessary.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2012;61:646-64.

- De F, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Lerardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-14.

- Kearney DJ, Brousal A. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice in the United States – Results from 224 patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000;45:265-71.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2012;61:646-64.

- De F, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Lerardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-14.

- Kearney DJ, Brousal A. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice in the United States – Results from 224 patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000;45:265-71.

Team touts a new, improved hydrogel

Louis Heiser & Robert Ackland

A new hydrogel improves on previous models by enabling the generation of more mature blood vessels, according to research published in ACS Nano.

The hydrogel also overcomes several other issues that have kept previous hydrogels from reaching their potential to treat injuries and forming new vasculature to treat heart attack, stroke, and ischemic tissue diseases.

Like earlier versions, the new hydrogel can be injected in liquid form and turns into a nanofiber-infused gel at the site of the injury. The difference with this hydrogel, according to researchers, is the quality of the blood vessels that are formed.

This hydrogel is made of self-assembling synthetic peptides that form nanofiber scaffolds. And the peptides incorporate a mimic of vascular endothelial growth factor, a signal protein that promotes angiogenesis.

Furthermore, the hydrogel can be easily delivered by syringe, is quickly infiltrated by hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, and quickly forms a mature vascular network.

“In a lot of the published literature, you see rings that only have the endothelial cell lining, and that indicates a very immature blood vessel,” said study author Jeffrey Hartgerink, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas.

“These types of vessels usually don’t persist and disappear shortly after they show up. In ours, you see that same endothelial cell layer, but surrounding it is a smooth muscle cell layer that indicates a much more mature vessel that’s likely to persist.”

Furthermore, the scaffolds the hydrogel forms show no signs of fibrous encapsulation. After 3 weeks, they are resorbed into the native tissue.

In previous studies, implanted synthetic materials tended to become encapsulated by fibrous barriers that kept cells and blood vessels from infiltrating the scaffold, Dr Hartgerink said.

“That is an extremely common problem in synthetic materials put into the body,” he explained. “Some avoid this problem, but if the body doesn’t like a material and isn’t able to destroy it, the solution is to wall it off.”

“As soon as that happens, the flow of nutrients across that barrier decreases to almost nothing. So the fact that we’ve developed syringe-directed delivery of a material that doesn’t develop fibrous encapsulation is really important.”

Other negative characteristics of earlier hydrogels—unwanted immune responses, surface degradation preceding their integration into biological systems, and the release of artificial degradation byproducts—have been eliminated as well, Dr Hartgerink said.

“There are a lot of features about this hydrogel that come together to make it a unique system,” he added. “If you look through the literature at what other people have done, each concept that is involved in our system probably exists somewhere already. The difference is that we have all these features in one place working together.” ![]()

Louis Heiser & Robert Ackland

A new hydrogel improves on previous models by enabling the generation of more mature blood vessels, according to research published in ACS Nano.

The hydrogel also overcomes several other issues that have kept previous hydrogels from reaching their potential to treat injuries and forming new vasculature to treat heart attack, stroke, and ischemic tissue diseases.

Like earlier versions, the new hydrogel can be injected in liquid form and turns into a nanofiber-infused gel at the site of the injury. The difference with this hydrogel, according to researchers, is the quality of the blood vessels that are formed.

This hydrogel is made of self-assembling synthetic peptides that form nanofiber scaffolds. And the peptides incorporate a mimic of vascular endothelial growth factor, a signal protein that promotes angiogenesis.

Furthermore, the hydrogel can be easily delivered by syringe, is quickly infiltrated by hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, and quickly forms a mature vascular network.

“In a lot of the published literature, you see rings that only have the endothelial cell lining, and that indicates a very immature blood vessel,” said study author Jeffrey Hartgerink, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas.

“These types of vessels usually don’t persist and disappear shortly after they show up. In ours, you see that same endothelial cell layer, but surrounding it is a smooth muscle cell layer that indicates a much more mature vessel that’s likely to persist.”

Furthermore, the scaffolds the hydrogel forms show no signs of fibrous encapsulation. After 3 weeks, they are resorbed into the native tissue.

In previous studies, implanted synthetic materials tended to become encapsulated by fibrous barriers that kept cells and blood vessels from infiltrating the scaffold, Dr Hartgerink said.

“That is an extremely common problem in synthetic materials put into the body,” he explained. “Some avoid this problem, but if the body doesn’t like a material and isn’t able to destroy it, the solution is to wall it off.”

“As soon as that happens, the flow of nutrients across that barrier decreases to almost nothing. So the fact that we’ve developed syringe-directed delivery of a material that doesn’t develop fibrous encapsulation is really important.”

Other negative characteristics of earlier hydrogels—unwanted immune responses, surface degradation preceding their integration into biological systems, and the release of artificial degradation byproducts—have been eliminated as well, Dr Hartgerink said.

“There are a lot of features about this hydrogel that come together to make it a unique system,” he added. “If you look through the literature at what other people have done, each concept that is involved in our system probably exists somewhere already. The difference is that we have all these features in one place working together.” ![]()

Louis Heiser & Robert Ackland

A new hydrogel improves on previous models by enabling the generation of more mature blood vessels, according to research published in ACS Nano.

The hydrogel also overcomes several other issues that have kept previous hydrogels from reaching their potential to treat injuries and forming new vasculature to treat heart attack, stroke, and ischemic tissue diseases.

Like earlier versions, the new hydrogel can be injected in liquid form and turns into a nanofiber-infused gel at the site of the injury. The difference with this hydrogel, according to researchers, is the quality of the blood vessels that are formed.

This hydrogel is made of self-assembling synthetic peptides that form nanofiber scaffolds. And the peptides incorporate a mimic of vascular endothelial growth factor, a signal protein that promotes angiogenesis.

Furthermore, the hydrogel can be easily delivered by syringe, is quickly infiltrated by hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, and quickly forms a mature vascular network.

“In a lot of the published literature, you see rings that only have the endothelial cell lining, and that indicates a very immature blood vessel,” said study author Jeffrey Hartgerink, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas.

“These types of vessels usually don’t persist and disappear shortly after they show up. In ours, you see that same endothelial cell layer, but surrounding it is a smooth muscle cell layer that indicates a much more mature vessel that’s likely to persist.”

Furthermore, the scaffolds the hydrogel forms show no signs of fibrous encapsulation. After 3 weeks, they are resorbed into the native tissue.

In previous studies, implanted synthetic materials tended to become encapsulated by fibrous barriers that kept cells and blood vessels from infiltrating the scaffold, Dr Hartgerink said.

“That is an extremely common problem in synthetic materials put into the body,” he explained. “Some avoid this problem, but if the body doesn’t like a material and isn’t able to destroy it, the solution is to wall it off.”

“As soon as that happens, the flow of nutrients across that barrier decreases to almost nothing. So the fact that we’ve developed syringe-directed delivery of a material that doesn’t develop fibrous encapsulation is really important.”

Other negative characteristics of earlier hydrogels—unwanted immune responses, surface degradation preceding their integration into biological systems, and the release of artificial degradation byproducts—have been eliminated as well, Dr Hartgerink said.

“There are a lot of features about this hydrogel that come together to make it a unique system,” he added. “If you look through the literature at what other people have done, each concept that is involved in our system probably exists somewhere already. The difference is that we have all these features in one place working together.” ![]()

Would a cholesterol medication have made a difference? … More

Would a cholesterol medication have made a difference?

A WOMAN WITH A HISTORY OF HYPERTENSION and hyperlipidemia sought treatment from her family physician (FP) for a protracted, nonproductive cough. The FP diagnosed sinusitis and reactive airway disease and prescribed steroids and antibiotics. The patient returned to the FP 5 more times over the next 9 weeks. The patient’s symptoms waxed and waned, but her cough continued. She reported chest tightness and shortness of breath on exertion. A chest x-ray revealed moderate heart enlargement. An echocardiogram was scheduled.

During the patient’s last visit, her FP noted that she had shortness of breath on exertion, but no chest pain. Three days later she suffered a massive myocardial infarction (MI). Cardiac catheterization found 80% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. She underwent angioplasty and stent placement; after this procedure her ejection fraction was 25% to 30%. One month later, the patient received a pacemaker/defibrillator. The patient’s cardiac symptoms returned 7 months later, and she underwent another angioplasty. She improved and her last echocardiogram showed near-normal heart function.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Although the patient had persistently elevated cholesterol levels, the FP failed to order repeat cholesterol studies and arrange for drug therapy. If the patient’s hyperlipidemia had been medically managed, her coronary artery disease would not have progressed to unstable angina and MI. The FP also failed to obtain routine electrocardiograms or an urgent cardiac consult after a chest x-ray showed an enlarged heart. The FP also failed to send the patient to an emergency department when she complained of shortness of breath on exertion.

THE DEFENSE An urgent cardiac work-up was not indicated and the patient’s cholesterol levels were only mildly elevated and did not require medical management. Her MI was unavoidable since most infarctions are due to plaque rupture in coronary vessels that aren’t occluded enough to require treatment.

VERDICT $1.6 million Michigan verdict.

COMMENT I think the key issue in this difficult diagnostic case is not the lack of prescribing cholesterol medication, but the repeated office visits with no definite diagnosis. If the physician had escalated the evaluation more quickly, the MI might have been avoided.

Narcotic misstep has tragic consequences

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN SOUGHT TREATMENT FOR DRUG ADDICTION. His physician prescribed methadone, despite not being licensed to do so. After 4 days of taking methadone, the patient went to the hospital because he felt dizzy and was having difficulty breathing. Two days after being examined and discharged, he died from methadone toxicity.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The toxicity was caused by simultaneous use of methadone and alprazolam, which the patient also had been prescribed. The physician failed to recognize the potential toxicity and should have performed testing that could have revealed the simultaneous use of other drugs. In addition, the physician was not licensed to prescribe methadone.

THE DEFENSE The physician had recommended a licensed, qualified facility that could have treated the plaintiff, but the plaintiff preferred treatment in a setting that allowed him to remain anonymous.

VERDICT $1.15 million New York settlement.

COMMENT Don’t break the law, even if your patient asks you to. Know your state laws regarding narcotic prescribing. These are getting more stringent due to the rapid rise in prescription narcotic overdose deaths in the United States.

Would a cholesterol medication have made a difference?

A WOMAN WITH A HISTORY OF HYPERTENSION and hyperlipidemia sought treatment from her family physician (FP) for a protracted, nonproductive cough. The FP diagnosed sinusitis and reactive airway disease and prescribed steroids and antibiotics. The patient returned to the FP 5 more times over the next 9 weeks. The patient’s symptoms waxed and waned, but her cough continued. She reported chest tightness and shortness of breath on exertion. A chest x-ray revealed moderate heart enlargement. An echocardiogram was scheduled.

During the patient’s last visit, her FP noted that she had shortness of breath on exertion, but no chest pain. Three days later she suffered a massive myocardial infarction (MI). Cardiac catheterization found 80% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. She underwent angioplasty and stent placement; after this procedure her ejection fraction was 25% to 30%. One month later, the patient received a pacemaker/defibrillator. The patient’s cardiac symptoms returned 7 months later, and she underwent another angioplasty. She improved and her last echocardiogram showed near-normal heart function.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Although the patient had persistently elevated cholesterol levels, the FP failed to order repeat cholesterol studies and arrange for drug therapy. If the patient’s hyperlipidemia had been medically managed, her coronary artery disease would not have progressed to unstable angina and MI. The FP also failed to obtain routine electrocardiograms or an urgent cardiac consult after a chest x-ray showed an enlarged heart. The FP also failed to send the patient to an emergency department when she complained of shortness of breath on exertion.

THE DEFENSE An urgent cardiac work-up was not indicated and the patient’s cholesterol levels were only mildly elevated and did not require medical management. Her MI was unavoidable since most infarctions are due to plaque rupture in coronary vessels that aren’t occluded enough to require treatment.

VERDICT $1.6 million Michigan verdict.

COMMENT I think the key issue in this difficult diagnostic case is not the lack of prescribing cholesterol medication, but the repeated office visits with no definite diagnosis. If the physician had escalated the evaluation more quickly, the MI might have been avoided.

Narcotic misstep has tragic consequences

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN SOUGHT TREATMENT FOR DRUG ADDICTION. His physician prescribed methadone, despite not being licensed to do so. After 4 days of taking methadone, the patient went to the hospital because he felt dizzy and was having difficulty breathing. Two days after being examined and discharged, he died from methadone toxicity.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The toxicity was caused by simultaneous use of methadone and alprazolam, which the patient also had been prescribed. The physician failed to recognize the potential toxicity and should have performed testing that could have revealed the simultaneous use of other drugs. In addition, the physician was not licensed to prescribe methadone.

THE DEFENSE The physician had recommended a licensed, qualified facility that could have treated the plaintiff, but the plaintiff preferred treatment in a setting that allowed him to remain anonymous.

VERDICT $1.15 million New York settlement.

COMMENT Don’t break the law, even if your patient asks you to. Know your state laws regarding narcotic prescribing. These are getting more stringent due to the rapid rise in prescription narcotic overdose deaths in the United States.

Would a cholesterol medication have made a difference?

A WOMAN WITH A HISTORY OF HYPERTENSION and hyperlipidemia sought treatment from her family physician (FP) for a protracted, nonproductive cough. The FP diagnosed sinusitis and reactive airway disease and prescribed steroids and antibiotics. The patient returned to the FP 5 more times over the next 9 weeks. The patient’s symptoms waxed and waned, but her cough continued. She reported chest tightness and shortness of breath on exertion. A chest x-ray revealed moderate heart enlargement. An echocardiogram was scheduled.

During the patient’s last visit, her FP noted that she had shortness of breath on exertion, but no chest pain. Three days later she suffered a massive myocardial infarction (MI). Cardiac catheterization found 80% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. She underwent angioplasty and stent placement; after this procedure her ejection fraction was 25% to 30%. One month later, the patient received a pacemaker/defibrillator. The patient’s cardiac symptoms returned 7 months later, and she underwent another angioplasty. She improved and her last echocardiogram showed near-normal heart function.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Although the patient had persistently elevated cholesterol levels, the FP failed to order repeat cholesterol studies and arrange for drug therapy. If the patient’s hyperlipidemia had been medically managed, her coronary artery disease would not have progressed to unstable angina and MI. The FP also failed to obtain routine electrocardiograms or an urgent cardiac consult after a chest x-ray showed an enlarged heart. The FP also failed to send the patient to an emergency department when she complained of shortness of breath on exertion.

THE DEFENSE An urgent cardiac work-up was not indicated and the patient’s cholesterol levels were only mildly elevated and did not require medical management. Her MI was unavoidable since most infarctions are due to plaque rupture in coronary vessels that aren’t occluded enough to require treatment.

VERDICT $1.6 million Michigan verdict.

COMMENT I think the key issue in this difficult diagnostic case is not the lack of prescribing cholesterol medication, but the repeated office visits with no definite diagnosis. If the physician had escalated the evaluation more quickly, the MI might have been avoided.

Narcotic misstep has tragic consequences

A 47-YEAR-OLD MAN SOUGHT TREATMENT FOR DRUG ADDICTION. His physician prescribed methadone, despite not being licensed to do so. After 4 days of taking methadone, the patient went to the hospital because he felt dizzy and was having difficulty breathing. Two days after being examined and discharged, he died from methadone toxicity.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The toxicity was caused by simultaneous use of methadone and alprazolam, which the patient also had been prescribed. The physician failed to recognize the potential toxicity and should have performed testing that could have revealed the simultaneous use of other drugs. In addition, the physician was not licensed to prescribe methadone.

THE DEFENSE The physician had recommended a licensed, qualified facility that could have treated the plaintiff, but the plaintiff preferred treatment in a setting that allowed him to remain anonymous.

VERDICT $1.15 million New York settlement.

COMMENT Don’t break the law, even if your patient asks you to. Know your state laws regarding narcotic prescribing. These are getting more stringent due to the rapid rise in prescription narcotic overdose deaths in the United States.

Malpractice Counsel

Traumatic Back Pain

An 84-year-old man with low-back pain following a motor vehicle crash was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS). He had been the restrained driver, stopped at a traffic light, when he was struck from behind by a second vehicle.

In the ED, the patient only complained of low-back pain. He denied any radiation of pain or lower-extremity numbness or weakness. He also denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, arthritis, and coronary artery disease.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examination was also normal; specifically, there was no tenderness to palpation of the cervical spine in the posterior midline. Regarding the cardiopulmonary examination, auscultation of the lungs revealed clear, bilateral breath sounds; the heart examination was normal. The patient had a soft abdomen, without tenderness, guarding, or rebound. His pelvis was stable, but he did exhibit some tenderness on palpation of the lower-thoracic and upper-lumbar spine. The neurological examination revealed normal motor strength and sensation in the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine and a urinalysis. The films were interpreted by both the EP and radiologist as normal; the results of the urinalysis were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with a lower back strain secondary to the motor vehicle crash and was discharged home with an analgesic.

The next day, however, the patient began to complain of increased back pain and lower-extremity numbness and weakness. He was brought back to the same hospital ED where he was noted to have severe weakness of both lower extremities and decreased sensation to touch. Additional imaging was performed, which demonstrated a fracture of T11 with spinal cord impingement. He was taken to surgery, but unfortunately the injury was permanent, and the patient was left with lower-extremity paralysis and bowel and bladder incontinence.

The plaintiff sued the EP and the radiologist for not properly interpreting the initial X-rays. The defendants denied liability, asserting the patient’s injury was a result of the collision and that nothing could have prevented it. According to a published account, the jury returned a verdict finding the EP to be 40% at fault and the radiologist 60% at fault.

Discussion

Emergency physicians frequently manage patients experiencing pain or injury following a motor vehicle crash. If the patient is complaining of neck or back pain, the prehospital providers will immobilize the patient with a rigid cervical collar (ie, if neck pain is present) and a long backboard if pain anywhere along the spine is present (ie, cervical, thoracic, or lumbar).

When the initial airway, breathing, circulation, and disability assessment for the trauma patient is performed and found to be normal, a secondary examination should be performed. Trauma patients with back pain should be log-rolled onto their side, with spinal immobilization followed by visual inspection and palpation/percussion of the midline of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The presence of midline tenderness suggests an acute injury and the need to keep the patient immobilized. Patients should be removed off the backboard and onto the gurney mattress while immobilizing the spine. The standard hospital mattress provides acceptable spinal support.1

Historically, plain radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine have been the imaging test of choice in the initial evaluation of suspected traumatic spinal column injury. However, similar to cervical spine trauma, computed tomography (CT) is assuming a larger role in the evaluation of patients with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine injury. When thoracic and abdominal CT scans are performed to evaluate for possible chest or abdominal trauma, those images can be reformatted and used to reconstruct images of the thoracic and lumbar spine, significantly reducing radiation exposure.1 While CT is the gold standard imaging study for evaluation of bony or ligamentous injury of the spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice for patients with neurological deficits or suspected spinal cord injury.

This patient had a completely normal neurological examination at initial presentation, so there was no indication for an MRI. The bony injury to T11 must have been very subtle for both the EP and the radiologist to have missed it. Unfortunately, the jury appears to have used the standard of “perfection,” rather than the “reasonable and prudent physician” in judging that the injury should have been detected. This case serves as a reminder that EPs cannot rely on consulting specialists to consistently and reliably provide accurate information. Moreover, this case emphasizes the need to consider CT imaging of the spine in the evaluation of patients with severe back pain of traumatic origin when plain radiographs appear normal.

Hip-Reduction Problem

A 79-year-old man with left hip pain presented to the ED via EMS. The patient stated that when he had bent over to retrieve his dropped glasses, he experienced the immediate onset of left hip pain and fell to the floor. He was unable to get up on his own and called EMS. The patient had undergone total left hip replacement 1 month prior. At presentation, he complained only of severe pain in his left hip; he denied head injury, neck pain or stiffness, chest pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, he was mildly tachycardic. His vital signs were: heart rate, 102 beats/minute; blood pressure, 156/88 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minutes; and temperature, afebrile. His pulse oximetry was 98% on room air. The HEENT, lung, heart, and abdominal examinations were all normal. Standing at the foot of the bed, the patient had obvious shortening, internal rotation, and adduction of the left leg. The left knee was without tenderness or swelling. The neurovascular examination of the left lower extremity was completely normal.

Plain radiographs of the pelvis and left hip ordered by the EP demonstrated a posterior hip dislocation with intact hardware. The EP consulted the patient’s orthopedic physician, and both agreed the EP should attempt to reduce the dislocation in the ED. Using conscious sedation, the EP was able to reduce the dislocation, but postreduction films demonstrated a new fracture requiring orthopedic surgery. Unfortunately, the patient had a very difficult recovery, ultimately resulting in death.

The patient’s estate sued the EP, stating he should have had the orthopedic physician reduce the dislocation. The defense argued that fracture is a known complication of reduction of a dislocated hip. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Approximately 85% to 90% of hip dislocations are posterior; the remaining 10% are anterior. Posterior hip dislocations are a common complication following total hip-replacement surgery.1 Hip dislocation is a true orthopedic and time-dependent emergency. The longer the hip remains dislocated, the more likely complications are to occur, including osteonecrosis of the femoral head, arthritic degeneration of the hip joint, and long-term neurological sequelae.2 The treatment of posterior hip dislocation (without fracture) is closed reduction as quickly as possible, and preferably within 6 hours.3 As this case demonstrates, minimal forces can result in a hip dislocation following a total hip replacement. In healthy patients, however, significant forces (eg, high-speed motor vehicle crashes) are required to cause posterior hip dislocation.

Patients with a posterior hip dislocation will present in severe pain and an inability to ambulate. In most cases of posterior hip dislocation, the affected lower extremity will be visibly shortened, internally rotated, and adducted. The knee should always be examined for injury, as well as performance of a thorough neurovascular examination of the affected extremity.

Plain X-ray films will usually identify a posterior hip dislocation. On an anteroposterior pelvis X-ray, the femoral head will be seen outside and just superior to the acetabulum. Special attention should be made to the acetabulum to ensure a concomitant acetabular fracture is not missed.

Indications for closed reduction of a posterior hip dislocation include dislocation with or without neurological deficit and no associated fracture, or dislocation with an associated fracture if no neurological deficits are present.2 An open traumatic hip dislocation should only be reduced in the operating room.

It is certainly within the purview of the EP to attempt a closed reduction for a posterior hip dislocation if no contraindications exist. The patient will need to be sedated (ie, procedural sedation, conscious sedation, or moderate sedation) for any chance of success at reduction. While it is beyond the scope of this article to review the various techniques used to reduce a posterior hip dislocation, one of the guiding principles is that after two or three unsuccessful attempts by the EP to reduce the dislocation, no further attempts should be made and orthopedic surgery services should be consulted. This is because the risk of complications increases as the number of failed attempts increase.

It is unclear how many attempts the EP made in this case. Fracture is a known complication when attempting reduction for a hip dislocation, be it an orthopedic surgeon or an EP. It was certainly appropriate for the EP in this case to attempt closed reduction, given the importance of timely reduction.

Reference (Traumatic Back Pain)

- Baron BJ, McSherry KJ, Larson JL, Scalea TM. Spinal and spinal cord trauma In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1709-1730.

(Hip-Reduction Problem)

- Dela Cruz JE, Sullivan DN, Varboncouer E, et al. Comparison of proceduralsedation for the reduction of dislocated total hip arthroplasty.West J Emerg Med. 2014:15(1):76-80.

- Davenport M. Joint reduction, hip dislocation, posterior. Medscape Web site. eMedicine.medscape.com/article/109225. Updated February 11, 2014. Accessed January 27, 2015.

- Steele MT, Stubbs AM. Hip and femur injuries. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1848-1856.

Traumatic Back Pain

An 84-year-old man with low-back pain following a motor vehicle crash was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS). He had been the restrained driver, stopped at a traffic light, when he was struck from behind by a second vehicle.

In the ED, the patient only complained of low-back pain. He denied any radiation of pain or lower-extremity numbness or weakness. He also denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, arthritis, and coronary artery disease.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examination was also normal; specifically, there was no tenderness to palpation of the cervical spine in the posterior midline. Regarding the cardiopulmonary examination, auscultation of the lungs revealed clear, bilateral breath sounds; the heart examination was normal. The patient had a soft abdomen, without tenderness, guarding, or rebound. His pelvis was stable, but he did exhibit some tenderness on palpation of the lower-thoracic and upper-lumbar spine. The neurological examination revealed normal motor strength and sensation in the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine and a urinalysis. The films were interpreted by both the EP and radiologist as normal; the results of the urinalysis were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with a lower back strain secondary to the motor vehicle crash and was discharged home with an analgesic.

The next day, however, the patient began to complain of increased back pain and lower-extremity numbness and weakness. He was brought back to the same hospital ED where he was noted to have severe weakness of both lower extremities and decreased sensation to touch. Additional imaging was performed, which demonstrated a fracture of T11 with spinal cord impingement. He was taken to surgery, but unfortunately the injury was permanent, and the patient was left with lower-extremity paralysis and bowel and bladder incontinence.

The plaintiff sued the EP and the radiologist for not properly interpreting the initial X-rays. The defendants denied liability, asserting the patient’s injury was a result of the collision and that nothing could have prevented it. According to a published account, the jury returned a verdict finding the EP to be 40% at fault and the radiologist 60% at fault.

Discussion

Emergency physicians frequently manage patients experiencing pain or injury following a motor vehicle crash. If the patient is complaining of neck or back pain, the prehospital providers will immobilize the patient with a rigid cervical collar (ie, if neck pain is present) and a long backboard if pain anywhere along the spine is present (ie, cervical, thoracic, or lumbar).

When the initial airway, breathing, circulation, and disability assessment for the trauma patient is performed and found to be normal, a secondary examination should be performed. Trauma patients with back pain should be log-rolled onto their side, with spinal immobilization followed by visual inspection and palpation/percussion of the midline of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The presence of midline tenderness suggests an acute injury and the need to keep the patient immobilized. Patients should be removed off the backboard and onto the gurney mattress while immobilizing the spine. The standard hospital mattress provides acceptable spinal support.1

Historically, plain radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine have been the imaging test of choice in the initial evaluation of suspected traumatic spinal column injury. However, similar to cervical spine trauma, computed tomography (CT) is assuming a larger role in the evaluation of patients with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine injury. When thoracic and abdominal CT scans are performed to evaluate for possible chest or abdominal trauma, those images can be reformatted and used to reconstruct images of the thoracic and lumbar spine, significantly reducing radiation exposure.1 While CT is the gold standard imaging study for evaluation of bony or ligamentous injury of the spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice for patients with neurological deficits or suspected spinal cord injury.

This patient had a completely normal neurological examination at initial presentation, so there was no indication for an MRI. The bony injury to T11 must have been very subtle for both the EP and the radiologist to have missed it. Unfortunately, the jury appears to have used the standard of “perfection,” rather than the “reasonable and prudent physician” in judging that the injury should have been detected. This case serves as a reminder that EPs cannot rely on consulting specialists to consistently and reliably provide accurate information. Moreover, this case emphasizes the need to consider CT imaging of the spine in the evaluation of patients with severe back pain of traumatic origin when plain radiographs appear normal.

Hip-Reduction Problem

A 79-year-old man with left hip pain presented to the ED via EMS. The patient stated that when he had bent over to retrieve his dropped glasses, he experienced the immediate onset of left hip pain and fell to the floor. He was unable to get up on his own and called EMS. The patient had undergone total left hip replacement 1 month prior. At presentation, he complained only of severe pain in his left hip; he denied head injury, neck pain or stiffness, chest pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, he was mildly tachycardic. His vital signs were: heart rate, 102 beats/minute; blood pressure, 156/88 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minutes; and temperature, afebrile. His pulse oximetry was 98% on room air. The HEENT, lung, heart, and abdominal examinations were all normal. Standing at the foot of the bed, the patient had obvious shortening, internal rotation, and adduction of the left leg. The left knee was without tenderness or swelling. The neurovascular examination of the left lower extremity was completely normal.

Plain radiographs of the pelvis and left hip ordered by the EP demonstrated a posterior hip dislocation with intact hardware. The EP consulted the patient’s orthopedic physician, and both agreed the EP should attempt to reduce the dislocation in the ED. Using conscious sedation, the EP was able to reduce the dislocation, but postreduction films demonstrated a new fracture requiring orthopedic surgery. Unfortunately, the patient had a very difficult recovery, ultimately resulting in death.

The patient’s estate sued the EP, stating he should have had the orthopedic physician reduce the dislocation. The defense argued that fracture is a known complication of reduction of a dislocated hip. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Approximately 85% to 90% of hip dislocations are posterior; the remaining 10% are anterior. Posterior hip dislocations are a common complication following total hip-replacement surgery.1 Hip dislocation is a true orthopedic and time-dependent emergency. The longer the hip remains dislocated, the more likely complications are to occur, including osteonecrosis of the femoral head, arthritic degeneration of the hip joint, and long-term neurological sequelae.2 The treatment of posterior hip dislocation (without fracture) is closed reduction as quickly as possible, and preferably within 6 hours.3 As this case demonstrates, minimal forces can result in a hip dislocation following a total hip replacement. In healthy patients, however, significant forces (eg, high-speed motor vehicle crashes) are required to cause posterior hip dislocation.

Patients with a posterior hip dislocation will present in severe pain and an inability to ambulate. In most cases of posterior hip dislocation, the affected lower extremity will be visibly shortened, internally rotated, and adducted. The knee should always be examined for injury, as well as performance of a thorough neurovascular examination of the affected extremity.

Plain X-ray films will usually identify a posterior hip dislocation. On an anteroposterior pelvis X-ray, the femoral head will be seen outside and just superior to the acetabulum. Special attention should be made to the acetabulum to ensure a concomitant acetabular fracture is not missed.

Indications for closed reduction of a posterior hip dislocation include dislocation with or without neurological deficit and no associated fracture, or dislocation with an associated fracture if no neurological deficits are present.2 An open traumatic hip dislocation should only be reduced in the operating room.

It is certainly within the purview of the EP to attempt a closed reduction for a posterior hip dislocation if no contraindications exist. The patient will need to be sedated (ie, procedural sedation, conscious sedation, or moderate sedation) for any chance of success at reduction. While it is beyond the scope of this article to review the various techniques used to reduce a posterior hip dislocation, one of the guiding principles is that after two or three unsuccessful attempts by the EP to reduce the dislocation, no further attempts should be made and orthopedic surgery services should be consulted. This is because the risk of complications increases as the number of failed attempts increase.

It is unclear how many attempts the EP made in this case. Fracture is a known complication when attempting reduction for a hip dislocation, be it an orthopedic surgeon or an EP. It was certainly appropriate for the EP in this case to attempt closed reduction, given the importance of timely reduction.

Traumatic Back Pain

An 84-year-old man with low-back pain following a motor vehicle crash was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS). He had been the restrained driver, stopped at a traffic light, when he was struck from behind by a second vehicle.

In the ED, the patient only complained of low-back pain. He denied any radiation of pain or lower-extremity numbness or weakness. He also denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, arthritis, and coronary artery disease.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examination was also normal; specifically, there was no tenderness to palpation of the cervical spine in the posterior midline. Regarding the cardiopulmonary examination, auscultation of the lungs revealed clear, bilateral breath sounds; the heart examination was normal. The patient had a soft abdomen, without tenderness, guarding, or rebound. His pelvis was stable, but he did exhibit some tenderness on palpation of the lower-thoracic and upper-lumbar spine. The neurological examination revealed normal motor strength and sensation in the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine and a urinalysis. The films were interpreted by both the EP and radiologist as normal; the results of the urinalysis were also normal. The patient was diagnosed with a lower back strain secondary to the motor vehicle crash and was discharged home with an analgesic.

The next day, however, the patient began to complain of increased back pain and lower-extremity numbness and weakness. He was brought back to the same hospital ED where he was noted to have severe weakness of both lower extremities and decreased sensation to touch. Additional imaging was performed, which demonstrated a fracture of T11 with spinal cord impingement. He was taken to surgery, but unfortunately the injury was permanent, and the patient was left with lower-extremity paralysis and bowel and bladder incontinence.

The plaintiff sued the EP and the radiologist for not properly interpreting the initial X-rays. The defendants denied liability, asserting the patient’s injury was a result of the collision and that nothing could have prevented it. According to a published account, the jury returned a verdict finding the EP to be 40% at fault and the radiologist 60% at fault.

Discussion

Emergency physicians frequently manage patients experiencing pain or injury following a motor vehicle crash. If the patient is complaining of neck or back pain, the prehospital providers will immobilize the patient with a rigid cervical collar (ie, if neck pain is present) and a long backboard if pain anywhere along the spine is present (ie, cervical, thoracic, or lumbar).

When the initial airway, breathing, circulation, and disability assessment for the trauma patient is performed and found to be normal, a secondary examination should be performed. Trauma patients with back pain should be log-rolled onto their side, with spinal immobilization followed by visual inspection and palpation/percussion of the midline of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The presence of midline tenderness suggests an acute injury and the need to keep the patient immobilized. Patients should be removed off the backboard and onto the gurney mattress while immobilizing the spine. The standard hospital mattress provides acceptable spinal support.1

Historically, plain radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine have been the imaging test of choice in the initial evaluation of suspected traumatic spinal column injury. However, similar to cervical spine trauma, computed tomography (CT) is assuming a larger role in the evaluation of patients with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine injury. When thoracic and abdominal CT scans are performed to evaluate for possible chest or abdominal trauma, those images can be reformatted and used to reconstruct images of the thoracic and lumbar spine, significantly reducing radiation exposure.1 While CT is the gold standard imaging study for evaluation of bony or ligamentous injury of the spine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice for patients with neurological deficits or suspected spinal cord injury.

This patient had a completely normal neurological examination at initial presentation, so there was no indication for an MRI. The bony injury to T11 must have been very subtle for both the EP and the radiologist to have missed it. Unfortunately, the jury appears to have used the standard of “perfection,” rather than the “reasonable and prudent physician” in judging that the injury should have been detected. This case serves as a reminder that EPs cannot rely on consulting specialists to consistently and reliably provide accurate information. Moreover, this case emphasizes the need to consider CT imaging of the spine in the evaluation of patients with severe back pain of traumatic origin when plain radiographs appear normal.

Hip-Reduction Problem

A 79-year-old man with left hip pain presented to the ED via EMS. The patient stated that when he had bent over to retrieve his dropped glasses, he experienced the immediate onset of left hip pain and fell to the floor. He was unable to get up on his own and called EMS. The patient had undergone total left hip replacement 1 month prior. At presentation, he complained only of severe pain in his left hip; he denied head injury, neck pain or stiffness, chest pain, or abdominal pain. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, he was mildly tachycardic. His vital signs were: heart rate, 102 beats/minute; blood pressure, 156/88 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minutes; and temperature, afebrile. His pulse oximetry was 98% on room air. The HEENT, lung, heart, and abdominal examinations were all normal. Standing at the foot of the bed, the patient had obvious shortening, internal rotation, and adduction of the left leg. The left knee was without tenderness or swelling. The neurovascular examination of the left lower extremity was completely normal.

Plain radiographs of the pelvis and left hip ordered by the EP demonstrated a posterior hip dislocation with intact hardware. The EP consulted the patient’s orthopedic physician, and both agreed the EP should attempt to reduce the dislocation in the ED. Using conscious sedation, the EP was able to reduce the dislocation, but postreduction films demonstrated a new fracture requiring orthopedic surgery. Unfortunately, the patient had a very difficult recovery, ultimately resulting in death.

The patient’s estate sued the EP, stating he should have had the orthopedic physician reduce the dislocation. The defense argued that fracture is a known complication of reduction of a dislocated hip. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Approximately 85% to 90% of hip dislocations are posterior; the remaining 10% are anterior. Posterior hip dislocations are a common complication following total hip-replacement surgery.1 Hip dislocation is a true orthopedic and time-dependent emergency. The longer the hip remains dislocated, the more likely complications are to occur, including osteonecrosis of the femoral head, arthritic degeneration of the hip joint, and long-term neurological sequelae.2 The treatment of posterior hip dislocation (without fracture) is closed reduction as quickly as possible, and preferably within 6 hours.3 As this case demonstrates, minimal forces can result in a hip dislocation following a total hip replacement. In healthy patients, however, significant forces (eg, high-speed motor vehicle crashes) are required to cause posterior hip dislocation.

Patients with a posterior hip dislocation will present in severe pain and an inability to ambulate. In most cases of posterior hip dislocation, the affected lower extremity will be visibly shortened, internally rotated, and adducted. The knee should always be examined for injury, as well as performance of a thorough neurovascular examination of the affected extremity.

Plain X-ray films will usually identify a posterior hip dislocation. On an anteroposterior pelvis X-ray, the femoral head will be seen outside and just superior to the acetabulum. Special attention should be made to the acetabulum to ensure a concomitant acetabular fracture is not missed.

Indications for closed reduction of a posterior hip dislocation include dislocation with or without neurological deficit and no associated fracture, or dislocation with an associated fracture if no neurological deficits are present.2 An open traumatic hip dislocation should only be reduced in the operating room.

It is certainly within the purview of the EP to attempt a closed reduction for a posterior hip dislocation if no contraindications exist. The patient will need to be sedated (ie, procedural sedation, conscious sedation, or moderate sedation) for any chance of success at reduction. While it is beyond the scope of this article to review the various techniques used to reduce a posterior hip dislocation, one of the guiding principles is that after two or three unsuccessful attempts by the EP to reduce the dislocation, no further attempts should be made and orthopedic surgery services should be consulted. This is because the risk of complications increases as the number of failed attempts increase.

It is unclear how many attempts the EP made in this case. Fracture is a known complication when attempting reduction for a hip dislocation, be it an orthopedic surgeon or an EP. It was certainly appropriate for the EP in this case to attempt closed reduction, given the importance of timely reduction.

Reference (Traumatic Back Pain)

- Baron BJ, McSherry KJ, Larson JL, Scalea TM. Spinal and spinal cord trauma In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1709-1730.

(Hip-Reduction Problem)

- Dela Cruz JE, Sullivan DN, Varboncouer E, et al. Comparison of proceduralsedation for the reduction of dislocated total hip arthroplasty.West J Emerg Med. 2014:15(1):76-80.

- Davenport M. Joint reduction, hip dislocation, posterior. Medscape Web site. eMedicine.medscape.com/article/109225. Updated February 11, 2014. Accessed January 27, 2015.

- Steele MT, Stubbs AM. Hip and femur injuries. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1848-1856.

Reference (Traumatic Back Pain)

- Baron BJ, McSherry KJ, Larson JL, Scalea TM. Spinal and spinal cord trauma In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1709-1730.

(Hip-Reduction Problem)

- Dela Cruz JE, Sullivan DN, Varboncouer E, et al. Comparison of proceduralsedation for the reduction of dislocated total hip arthroplasty.West J Emerg Med. 2014:15(1):76-80.

- Davenport M. Joint reduction, hip dislocation, posterior. Medscape Web site. eMedicine.medscape.com/article/109225. Updated February 11, 2014. Accessed January 27, 2015.

- Steele MT, Stubbs AM. Hip and femur injuries. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine—A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011:1848-1856.

Transoral fundoplication can be effective against GERD symptoms

Transoral esophagogastric fundoplication can be an effective treatment for patients seeking to alleviate symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, particularly in individuals with persistent regurgitation despite prior treatment with proton pump inhibitor therapy, according to the results of a new study published in the February issue of Gastroenterology (doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.009).

“Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) remains one of the most common conditions for which Americans take daily medication, and PPI use has more than doubled in the last decade,” wrote lead authors Dr. John G. Hunter of Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and Dr. Peter J. Kahrilas of Northwestern University in Chicago, and their associates. “Despite this, up to 40% of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–dependent GERD patients have troublesome symptoms of GERD, despite PPI therapy.”

In the Randomized EsophyX vs Sham, Placebo-Controlled Transoral Fundoplication (RESPECT) trial, investigators screened 696 patients who were experiencing “troublesome regurgitation” despite daily PPI treatment. These subjects were evaluated via three validated GERD-specific symptom scales, and were either on or off PPI use at the time of trial commencement. Post trial, patients were blinded to therapy and were reassessed at intervals of 2, 12, and 26 weeks. All patients underwent 48-hour esophageal pH monitoring and esophagogastroduodenoscopy at 66 months after the trial ended.

Regurgitation severity was based on the Montreal definition, which was used to measure efficacy of treatments given as part of the study. The Montreal definition of reflux is described by the authors as “either mucosal damage or troublesome symptoms attributable to reflux.” Those with “least troublesome” regurgitation while on PPIs “underwent barium swallow, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, 48-hour esophageal pH monitoring (off PPIs), and high-resolution esophageal manometry analyses.”

Eighty-seven subjects with GERD and hiatal hernias of at least 2 centimeters were randomly assigned to groups that underwent transoral fundoplication (TF) followed by placebo treatment after 6 months, while 42 subjects, who made up the control group, underwent a “sham surgery” and began regimens of once- or twice-daily omeprazole medication for 6 months.