User login

Cystic lung disease: Systematic, stepwise diagnosis

Air-filled pulmonary lesions commonly detected on chest computed tomography. Cystic lung lesions should be distinguished from other air-filled lesions to facilitate diagnosis. Primary care physicians play an integral role in the recognition of cystic lung disease.

The differential diagnosis of cystic lung disease is broad and includes isolated pulmonary, systemic, infectious, and congenital etiologies.

Here, we aim to provide a systematic, stepwise approach to help differentiate among the various cystic lung diseases and devise an algorithm for diagnosis. In doing so, we will discuss the clinical and radiographic features of many of these diseases:

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Interstitial pneumonia (desquamative interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia)

- Congenital cystic lung disease (congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, bronchogenic cyst) Pulmonary infection

- Systemic disease (amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, neurofibromatosis type 1).

STEP 1: RULE OUT CYST-MIMICS

A pulmonary cyst is a round, circumscribed space surrounded by an epithelial or fibrous wall of variable thickness.1 On chest radiography and computed tomography, a cyst appears as a round parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung.1 Cysts vary in wall thickness but usually have a thin wall (< 2 mm) and occur without associated pulmonary emphysema.1 They typically contain air but occasionally contain fluid or solid material.

A pulmonary cyst can be categorized as a bulla, bleb, or pneumatocele.

Bullae are larger than 1 cm in diameter, sharply demarcated by a thin wall, and usually accompanied by emphysematous changes in the adjacent lung.1

Blebs are no larger than 1 cm in diameter, are located within the visceral pleura or the subpleural space, and appear on computed tomography as thin-walled air spaces that are contiguous with the pleura.1 The distinction between a bleb and a bulla is of little clinical importance, and is often unnecessary.

Pneumatoceles are cysts that are frequently caused by acute pneumonia, trauma, or aspiration of hydrocarbon fluid, and are usually transient.1

Mimics of pulmonary cysts include pulmonary cavities, emphysema, loculated pneumothoraces, honeycomb lung, and bronchiectasis (Figure 1).2

Pulmonary cavities differ from cysts in that their walls are typically thicker (usually > 4 mm).3

Emphysema differs from cystic lung disease as it typically leads to focal areas or regions of decreased lung attenuation that do not have defined walls.1

Honeycombing refers to a cluster or row of cysts, 1 to 3 mm in wall thickness and typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter, that are associated with end-stage lung fibrosis.1 They are typically subpleural in distribution and are accompanied by fibrotic features such as reticulation and traction bronchiectasis.1

Bronchiectasis is dilation and distortion of bronchi and bronchioles and can be mistaken for cysts when viewed en face.1

Loculated pneumothoraces can also mimic pulmonary cysts, but they typically fail to adhere to a defined anatomic unit and are subpleural in distribution.

STEP 2: CHARACTERIZE THE CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Clinical signs and symptoms of cystic lung disease play a key role in diagnosis (Table 1). For instance, spontaneous pneumothorax is commonly associated with diffuse cystic lung disease (lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome), while insidious dyspnea, with or without associated pneumothorax, is usually associated with the interstitial pneumonias (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia).

In addition, congenital abnormalities of the lung can lead to cyst formation. These abnormalities, especially when associated with other congenital abnormalities, are often diagnosed in the prenatal and perinatal periods. However, some remain undetected until incidentally found later in adulthood or if superimposing infection develops.

Primary pulmonary infections can also cause parenchymal necrosis, which in turn cavitates or forms cysts.4

Lastly, cystic lung diseases can occur as part of a multiorgan or systemic illness in which the lung is one of the organs involved. Although usually diagnosed before the discovery of cysts or manifestations of pulmonary symptoms, they can present as a diagnostic challenge, especially when lung cysts are the initial presentation.bsence of amyloid fibrils.

In view of the features of the different types of cystic lung disease, adults with cystic lung disease can be grouped according to their typical clinical presentations (Table 2):

- Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

- Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

- Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infection

- Signs and symptoms that are primarily nonpulmonary.

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax can be manifestations of lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, or lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is characterized by abnormal cellular proliferation within the lung, kidney, lymphatic system, or any combination.5 The peak prevalence is in the third to fourth decades of life, and most patients are women of childbearing age.6 In addition to progressive dyspnea on exertion and pneumothorax, other signs and symptoms include hemoptysis, nonproductive cough, chylous pleural effusion, and ascites.7,8

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene.9 It is characterized by skin fibrofolliculomas, pulmonary cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and renal cancer.10

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis is part of the spectrum of Langerhans cell histiocytosis that, in addition to the lungs, can also involve the bone, pituitary gland, thyroid, skin, lymph nodes, and liver.11 It occurs almost exclusively in smokers, affecting individuals in their 20s and 30s, with no gender predilection.12,13 In addition to nonproductive cough and dyspnea, patients can also present with fever, anorexia, and weight loss,13 but approximately 25% of patients are asymptomatic.14

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia is an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia that, like pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is seen almost exclusively in current or former smokers, who account for about 90% of patients with this disease. It affects almost twice as many men as women.15,16 The mean age at onset is 42 to 46.15,16 In addition to insidious cough and dyspnea, digital clubbing develops in 26% to 40% of patients.16,17

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia is another rare idiopathic pneumonia, usually associated with connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome, immunodeficiencies, and viral infections.18–21 It is more common in women, presenting between the 4th and 7th decades of life, with a mean age at diagnosis of 50 to 56.18,22 In addition to progressive dyspnea and cough, other symptoms include weight loss, pleuritic pain, arthralgias, fatigue, night sweats, and fever.23

In summary, in this clinical group, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome should be considered when patients present with spontaneous pneumothorax; those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also present with skin lesions or renal cancer. In patients with progressive dyspnea and cough, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia should be considered in those with a known history of connective tissue disease or immunodeficiency. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically presents at a younger age (20 to 30 years old) than desquamative interstitial pneumonia (smokers in their 40s). Making the distinction, however, will likely require imaging with computed tomography.

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia can be manifestations of congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, or bronchogenic cyst.

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, of which there are five types, is the most common pulmonary congenital abnormality. It accounts for up to 95% of cases of congenital cystic lung disease.24,25 About 85% of cases are detected in the prenatal or perinatal periods.26 Late-onset congenital pulmonary airway malformation (arising in childhood to adulthood) presents with recurrent pneumonia in about 75% of cases and can be misdiagnosed as lung abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis, or bronchiectasis.27

Pulmonary sequestration, the second most common pulmonary congenital abnormality, is characterized by a portion of lung that does not connect to the tracheobronchial tree and has its own systemic arterial supply.24 Intralobar sequestration, which shares the pleural investment with normal lung, accounts for about 80% of cases of pulmonary sequestration.28–30 In addition to signs or symptoms of pulmonary infection, patients with pulmonary sequestration can remain asymp-

tomatic (about 25% of cases), or can present with hemoptysis or hemothorax.28–30 In adults, the typical age at presentation is between 20 and 25.29,30

Bronchogenic cyst is usually life-threatening in children. In adults, it commonly causes cough and chest pain.31 Hemoptysis, dysphagia, hoarseness, and diaphragmatic paralysis can also occur.32,33 The mean age at diagnosis in adults is 35 to 40.31,32

In summary, most cases of recurrent pneumonia with cysts are due to congenital pulmonary airway malformation. Pulmonary sequestration is the second most common cause of cystic lung disease in this group. Bronchogenic cyst is usually fatal in fetal development; smaller cysts can go unnoticed during the earlier years and are later found incidentally as imaging abnormalities in adults.

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections can be due to Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

P jirovecii pneumonia commonly develops in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and low CD4 counts, recipients of hematologic or solid-organ transplants, and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy (eg, glucocorticoids or chemotherapy).

Echinococcal infections (with Echinococcus granulosus or multilocularis species) are more common in less-developed countries such as those in South America or the Middle East, in China, or in patients who have traveled to endemic areas.34

In summary, cystic lung disease in patients with primary pulmonary infections can be diagnosed by the patient’s clinical history and risk factors for infections. Those with human immunodeficiency virus infection and other causes of immunodeficiency are predisposed to P jirovecii pneumonia. Echinococcal infections occur in those with a history of travel to an endemic area.

Primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

If the patient has primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms, think about pulmonary amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Pulmonary amyloidosis has a variety of manifestations, including tracheobronchial disease, nodular parenchymal disease, diffuse or alveolar septal pattern, pleural disease, lymphadenopathy, and pulmonary cysts.4

Light chain deposition disease shares some clinical features with amyloidosis. However, the light chain fragments in this disease do not form amyloid fibrils and therefore do not stain positively with Congo red. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ.4

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is characterized by collections of neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and pigmented hamartomas in the iris (Lisch nodules).35

In summary, patients in this group typically present with complications related to systemic involvement. Those with neurofibromatosis type 1 present with ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and neurologic manifestations. Amyloidosis and light chain deposition disease most commonly involve the renal system; their distinction will likely require tissue biopsy and Congo-red staining.

STEP 3: CHARACTERIZE THE RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Characterization of pulmonary cysts and their distribution plays a key role in the diagnosis. Radiographically, cystic lung diseases can be subclassified into two major categories according to their cystic distribution:

- Discrete (focal or multifocal)

- Diffuse (unilobular or panlobular).2,3

Discrete cystic lung diseases include congenital abnormalities, infectious diseases, and interstitial pneumonias.2,3

Diffuse, panlobular cystic lung diseases include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.7,13,36–39

In addition, other associated radiographic findings play a major role in diagnosis.

Cysts in patients presenting with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cysts are seen in nearly all cases of advanced lymphangioleiomyomatosis, typically in a diffuse pattern, varying from 2 mm to 40 mm in diameter, and uniform in shape (Figure 2A).7,8,40–42

Other radiographic features include vessels located at the periphery of the cysts (in contrast to the centrilobular pattern seen with emphysema), and chylous pleural effusions (in about 22% of patients).40 Nodules are typically not seen with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and if found represent type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Nodules measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter and favoring a centrilobular location are often seen on computed tomography. Pulmonary cysts occur in about 61% of patients.13,43 Cysts are variable in size and shape (Figure 2B), in contrast to their uniform appearance in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Most cysts are less than 10 mm in diameter; however, they can be up to 80 mm.13,43 Early in its course, nodules may predominate in the upper and middle lobes. Over time, diffuse cysts become more common and can be difficult to differentiate from advanced smoking-induced emphysema.44

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Approximately 70% to 100% of patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will have multiple pulmonary cysts detected on computed tomography. These cysts are characteristically basal and subpleural in location, with varying sizes and irregular shapes in otherwise normal lung parenchyma (Figure 2C).36,45,46

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Pulmonary cysts are present on computed tomography in about 32% of patients.47 They are usually round and less than 20 mm in diameter.48 Ground-glass opacity is present in almost all cases of desquamative interstitial pneumonia, with a diffuse pattern in 25% to 44% of patients.16,17,47

Pulmonary cysts occur in up to two-thirds of those with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. Cysts are usually multifocal and perivascular in distribution and have varying sizes and shapes (Figure 2D).22 Ground-glass opacity and poorly defined centrilobular nodules are also frequently seen. Other computed tomographic findings include thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, focal consolidation, interseptal lobular thickening, pleural thickening, and lymph node enlargement.22

In summary, in this group of patients, diffuse panlobular cysts are due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cysts due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis have a diffuse distribution, while those due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be upper-lobe-predominant and in the early stages are associated with stellate centrilobular nodules. Cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome tend to be subpleural and those due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia are perivascular in distribution.

Cysts that are incidentally found or occur in patients with recurrent pneumonia

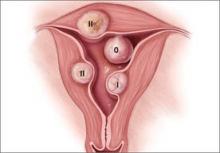

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation types 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 3A, 3B). Cysts are typically discrete and focal or multifocal in distribution, but cases of multilobar and bilateral distribution have also been reported.27,49 The lower lobes are more often involved.49 Cysts vary in size and shape and can contain air, fluid, or both.27,49 Up to 50% of cases can occur in conjunction with pulmonary sequestration.50

Pulmonary sequestration displays an anomalous arterial supply on computed tomography (Figure 3C). Other imaging findings include mass lesions (49%), cystic lesions (29%), cavitary lesions (12%), and bronchiectasis.30 Air trapping can be seen in the adjacent lung. Lower lobe involvement accounts for more than 95% of total cases of sequestration.30 The cysts are usually discrete or focal in distribution. Misdiagnosis of pulmonary sequestration is common, and can include pulmonary abscess, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and lung cancer.30

Bronchogenic cyst. Cyst contents generally demonstrate water attenuation, or higher attenuation if filled with proteinaceous/mucoid material or calcium deposits; air-fluid levels are seen in infected cysts.32 Intrapulmonary cysts have a predilection for the lower lobes and are usually discrete or focal in distribution.31,32 Mediastinal cysts are usually homogeneous, solitary, and located in the middle mediastinum.32 Cysts vary in size from 20 to 90 mm, with a mean diameter of 40 mm.31

In summary, in this group of cystic lung diseases, characteristic computed tomographic findings will suggest the diagnosis—air-filled cysts of varying sizes for congenital pulmonary airway malformation and anomalous vascular supply for pulmonary sequestration. Bronchogenic cysts will tend to have water or higher-than-water attenuation due to proteinaceous-mucoid material or calcium deposits.

Cysts in patients with signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

P jirovecii pneumonia. Between 10% and 15% of patients have cysts, and about 18% present with spontaneous pneumothorax.51 Cysts in P jirovecii pneumonia vary in size from 15 to 85 mm in diameter and tend to occur in the upper lobes (Figure 4A).51,52

Echinococcal infection. Echinococcal pulmonary cysts typically are single and located more often in the lower lobes (Figure 4B).53,54 Cysts can be complicated by air-fluid levels, hydropneumothorax, or pneumothorax, or they can turn into cavitary lesions.

The diagnoses of these pulmonary infections are usually made by clinical and computed tomographic findings and depend less on detecting and characterizing lung cysts. Patients with P jirovecii pneumonia tend to have bilateral perihilar ground-glass opacities, while air-fluid levels suggest echinococcal infections. Cysts in this group of patients tend to be discrete or focal or multifocal in distribution, and vary in size.

Cysts in patients with primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

Amyloidosis. Cyst formation is rare in amyloidosis.4 When present, cysts can be diffuse and scattered in distribution, in varying sizes (usually < 30 mm in diameter) and irregular shapes (Figure 5).55,56

Pulmonary light chain deposition disease usually presents as linear opacities and small nodules on chest computed tomography. Numerous cysts that are diffuse in distribution and have no topographic predominance can also be present. They can progress in number and size and coalesce to form irregular shapes.57

Neurofibromatosis type 1. In neurofibromatosis type 1, the most common radiographic presentations are bibasilar reticular opacities (50%), bullae (50%), and ground glass opacities (37%).58 Well-formed cysts occur in up to 25% of patients and tend to be diffuse and smaller (2 to 18 mm in diameter), with upper lobe predominance.58,59

In summary, in this group of patients, bibasilar reticular and ground-glass opacities suggest neurofibromatosis type 1, while nodules and linear opacities suggest amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease. Cysts tend to be diffuse with varying sizes.

STEP 4: PUT IT ALL TOGETHER

Diagnosis in insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

For patients who present with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax, the diagnosis of cystic lung disease can be made by characterizing the distribution, size, and shape of the cysts (Table 3).

Diffuse, panlobular distribution. Cystic lung diseases with this pattern include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In this group, cysts that are uniform in size and regular in shape are invariably due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Those with variable size and irregular shapes can be due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be smokers and their cysts tend to be upper- lobe-predominant. Those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will likely have renal cancer or skin lesions; their cysts tend to be basilar and subpleural in distribution.

Cysts that are focal or multifocal and unilobular are due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Patients with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia tend to have underlying connective tissue disease; those with desquamative interstitial pneumonia are almost always smokers. The definitive diagnosis for lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia can require a tissue biopsy.

Diagnosis in patients with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

In those who present with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia, suspicion for a congenital lung malformation should be raised. Patients with a type 1, 2, or 4 congenital pulmonary airway malformation typically have air-filled cysts in varying sizes; those with pulmonary sequestration have an anomalous arterial supply in addition to cysts that are usually located in the lower lobes. Bronchogenic cysts tend to be larger, with attenuation equal to or greater than that of water, and distinguishing them from congenital pulmonary airway malformation will likely require surgical examination.

Diagnosis in patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections

Patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections should be investigated according to clinical risk factors for P jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

Diagnosis in patients with primarily nonpulmonary presentations

The distinction between amyloidosis and neurofibromatosis type 1 can be made by the history and the clinical examination. However, a definitive diagnosis of amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease requires tissue examination for the presence or absence of amyloid fibrils.

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008; 246:697–722.

- Cosgrove GP, Frankel SK, Brown KK. Challenges in pulmonary fibrosis. 3: cystic lung disease. Thorax 2007; 62:820–829.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78:744–752.

- Ryu JH, Tian X, Baqir M, Xu K. Diffuse cystic lung diseases. Front Med 2013; 7:316–327.

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest 2008; 133:507–516.

- Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al; Review Panel of the ERS LAM Task Force. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:14–26.

- Taylor JR, Ryu J, Colby TV, Raffin TA. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Clinical course in 32 patients. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:1254–1260.

- Chu SC, Horiba K, Usuki J. Comprehensive evaluation of 35 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 1999; 115:1041–1052.

- Graham RB, Nolasco M, Peterlin B, Garcia CK. Nonsense mutations in folliculin presenting as isolated familial spontaneous pneumothorax in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172:39–44.

- Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol 1977; 113:1674–1677.

- Sundar KM, Gosselin MV, Chung HL, Cahill BC. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: emerging concepts in pathobiology, radiology, and clinical evolution of disease. Chest 2003; 123:1673–1683.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1969–1978.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Limper AH. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:484–490.

- Mendez JL, Nadrous HF, Vassallo R, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Pneumothorax in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Chest 2004; 125:1028–1032.

- Carrington CB, Gaensler EA, Coutu RE, FitzGerald MX, Gupta RG. Natural history and treated course of usual and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1978; 298:801–809.

- Ryu JH, Myers JL, Capizzi SA, Douglas WW, Vassallo R, Decker PA. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005; 127:178–184.

- Lynch DA, Travis WD, Müller NL, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: CT features. Radiology 2005; 236:10–21.

- Strimlan CV, Rosenow EC 3rd, Weiland LH, Brown LR. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis. Review of 13 cases. Ann Intern Med 1978; 88:616–621.

- Arish N, Eldor R, Fellig Y, et al. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia associated with common variable immunodeficiency resolved with intravenous immunoglobulins. Thorax 2006; 61:1096–1097.

- Schooley RT, Carey RW, Miller G, et al. Chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection associated with fever and interstitial pneumonitis. Clinical and serologic features and response to antiviral chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med 1986; 104:636–643.

- Kramer MR, Saldana MJ, Ramos M, Pitchenik AE. High titers of Epstein-Barr virus antibodies in adult patients with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis associated with AIDS. Respir Med 1992; 86:49–52.

- Johkoh T, Müller NL, Pickford HA, et al. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1999; 212:567–572.

- Swigris JJ, Berry GJ, Raffin TA, Kuschner WG. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia: a narrative review. Chest 2002; 122:2150–2164.

- Biyyam DR, Chapman T, Ferguson MR, Deutsch G, Dighe MK. Congenital lung abnormalities: embryologic features, prenatal diagnosis, and postnatal radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2010; 30:1721–1738.

- Cloutier MM, Schaeffer DA, Hight D. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. Chest 1993; 103:761–764.

- Luján M, Bosque M, Mirapeix RM, Marco MT, Asensio O, Domingo C. Late-onset congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. Embryology, clinical symptomatology, diagnostic procedures, therapeutic approach and clinical follow-up. Respiration 2002; 69:148–154.

- Oh BJ, Lee JS, Kim JS, Lim CM, Koh Y. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung in adults: clinical and CT evaluation of seven patients. Respirology 2006; 11:496–501.

- Tsolakis CC, Kollias VD, Panayotopoulos PP. Pulmonary sequestration. Experience with eight consecutive cases. Scand Cardiovasc J 1997; 31:229–232.

- Sauvanet A, Regnard JF, Calanducci F, Rojas-Miranda A, Dartevelle P, Levasseur P. Pulmonary sequestration. Surgical aspects based on 61 cases. Rev Pneumol Clin 1991; 47:126–132. Article in French.

- Wei Y, Li F. Pulmonary sequestration: a retrospective analysis of 2,625 cases in China. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011; 40:e39–e42.

- Patel SR, Meeker DP, Biscotti CV, Kirby TJ, Rice TW. Presentation and management of bronchogenic cysts in the adult. Chest 1994; 106:79–85.

- Limaïem F, Ayadi-Kaddour A, Djilani H, Kilani T, El Mezni F. Pulmonary and mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: a clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Lung 2008; 186:55–61.

- Liu HS, Li SQ, Cao ZL, Zhang ZY, Ren H. Clinical features and treatment of bronchogenic cyst in adults. Chin Med Sci J 2009; 24:60–63.

- Jenkins DJ, Romig T, Thompson RC. Emergence/re-emergence of Echinococcus spp.—a global update. Int J Parasitol 2005; 35:1205–1219.

- Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med 1981; 305:1617–1627.

- Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, et al. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:1044–1053.

- Biko DM, Schwartz M, Anupindi SA, Altes TA. Subpleural lung cysts in Down syndrome: prevalence and association with coexisting diagnoses. Pediatr Radiol 2008; 38:280–284.

- Colombat M, Stern M, Groussard O, et al. Pulmonary cystic disorder related to light chain deposition disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:777–780.

- Ohdama S, Akagawa S, Matsubara O, Yoshizawa Y. Primary diffuse alveolar septal amyloidosis with multiple cysts and calcification. Eur Respir J 1996; 9:1569–1571.

- Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE. Clinical experience of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the UK. Thorax 2000; 55:1052–1057.

- Kitaichi M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Izumi T. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a report of 46 patients including a clinicopathologic study of prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 151:527–533.

- Urban T, Lazor R, Lacronique J, et al. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A study of 69 patients. Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM”O”P). Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78:321–337.

- Schönfeld N, Frank W, Wenig S, et al. Clinical and radiologic features, lung function and therapeutic results in pulmonary histiocytosis X. Respiration 1993; 60:38–44.

- Lacronique J, Roth C, Battesti JP, Basset F, Chretien J. Chest radiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X: a report based on 50 adult cases. Thorax 1982; 37:104–109.

- Kluger N, Giraud S, Coupier I, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: clinical and genetic studies of 10 French families. Br J Dermatol 2010; 162:527–537.

- Tobino K, Gunji Y, Kurihara M, et al. Characteristics of pulmonary cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: thin-section CT findings of the chest in 12 patients. Eur J Radiol 2011; 77:403–409.

- Hartman TE, Primack SL, Swensen SJ, Hansell D, McGuinness G, Müller NL. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1993; 187:787–790.

- Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Chronic cystic lung disease: diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution CT in 92 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180:827–835.

- Patz EF Jr, Müller NL, Swensen SJ, Dodd LG. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation in adults: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995; 19:361–364.

- Conran RM, Stocker JT. Extralobar sequestration with frequently associated congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, type 2: report of 50 cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol 1999; 2:454–463.

- Kennedy CA, Goetz MB. Atypical roentgenographic manifestations of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:1390–1398.

- Sandhu JS, Goodman PC. Pulmonary cysts associated with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with AIDS. Radiology 1989; 173:33–35.

- Doğan R, Yüksel M, Cetin G, et al. Surgical treatment of hydatid cysts of the lung: report on 1,055 patients. Thorax 1989; 44:192–199.

- Salih OK, Topcuoğlu MS, Celik SK, Ulus T, Tokcan A. Surgical treatment of hydatid cysts of the lung: analysis of 405 patients. Can J Surg 1998; 41:131–135.

- Ohdama S, Akagawa S, Matsubara O, Yoshizawa Y. Primary diffuse alveolar septal amyloidosis with multiple cysts and calcification. Eur Respir J 1996; 9:1569–1571.

- Sakai M, Yamaoka M, Kawaguchi M, Hizawa N, Sato Y. Multiple cystic pulmonary amyloidosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92:e109.

- Colombat M, Caudroy S, Lagonotte E, et al. Pathomechanisms of cyst formation in pulmonary light chain deposition disease. Eur Respir J 2008; 32:1399–1403.

- Zamora AC, Collard HR, Wolters PJ, Webb WR, King TE. Neurofibromatosis-associated lung disease: a case series and literature review. Eur Respir J 2007; 29:210–214.

- Oikonomou A, Vadikolias K, Birbilis T, Bouros D, Prassopoulos P. HRCT findings in the lungs of non-smokers with neurofibromatosis. Eur J Radiol 2011; 80:e520–e523.

Air-filled pulmonary lesions commonly detected on chest computed tomography. Cystic lung lesions should be distinguished from other air-filled lesions to facilitate diagnosis. Primary care physicians play an integral role in the recognition of cystic lung disease.

The differential diagnosis of cystic lung disease is broad and includes isolated pulmonary, systemic, infectious, and congenital etiologies.

Here, we aim to provide a systematic, stepwise approach to help differentiate among the various cystic lung diseases and devise an algorithm for diagnosis. In doing so, we will discuss the clinical and radiographic features of many of these diseases:

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Interstitial pneumonia (desquamative interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia)

- Congenital cystic lung disease (congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, bronchogenic cyst) Pulmonary infection

- Systemic disease (amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, neurofibromatosis type 1).

STEP 1: RULE OUT CYST-MIMICS

A pulmonary cyst is a round, circumscribed space surrounded by an epithelial or fibrous wall of variable thickness.1 On chest radiography and computed tomography, a cyst appears as a round parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung.1 Cysts vary in wall thickness but usually have a thin wall (< 2 mm) and occur without associated pulmonary emphysema.1 They typically contain air but occasionally contain fluid or solid material.

A pulmonary cyst can be categorized as a bulla, bleb, or pneumatocele.

Bullae are larger than 1 cm in diameter, sharply demarcated by a thin wall, and usually accompanied by emphysematous changes in the adjacent lung.1

Blebs are no larger than 1 cm in diameter, are located within the visceral pleura or the subpleural space, and appear on computed tomography as thin-walled air spaces that are contiguous with the pleura.1 The distinction between a bleb and a bulla is of little clinical importance, and is often unnecessary.

Pneumatoceles are cysts that are frequently caused by acute pneumonia, trauma, or aspiration of hydrocarbon fluid, and are usually transient.1

Mimics of pulmonary cysts include pulmonary cavities, emphysema, loculated pneumothoraces, honeycomb lung, and bronchiectasis (Figure 1).2

Pulmonary cavities differ from cysts in that their walls are typically thicker (usually > 4 mm).3

Emphysema differs from cystic lung disease as it typically leads to focal areas or regions of decreased lung attenuation that do not have defined walls.1

Honeycombing refers to a cluster or row of cysts, 1 to 3 mm in wall thickness and typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter, that are associated with end-stage lung fibrosis.1 They are typically subpleural in distribution and are accompanied by fibrotic features such as reticulation and traction bronchiectasis.1

Bronchiectasis is dilation and distortion of bronchi and bronchioles and can be mistaken for cysts when viewed en face.1

Loculated pneumothoraces can also mimic pulmonary cysts, but they typically fail to adhere to a defined anatomic unit and are subpleural in distribution.

STEP 2: CHARACTERIZE THE CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Clinical signs and symptoms of cystic lung disease play a key role in diagnosis (Table 1). For instance, spontaneous pneumothorax is commonly associated with diffuse cystic lung disease (lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome), while insidious dyspnea, with or without associated pneumothorax, is usually associated with the interstitial pneumonias (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia).

In addition, congenital abnormalities of the lung can lead to cyst formation. These abnormalities, especially when associated with other congenital abnormalities, are often diagnosed in the prenatal and perinatal periods. However, some remain undetected until incidentally found later in adulthood or if superimposing infection develops.

Primary pulmonary infections can also cause parenchymal necrosis, which in turn cavitates or forms cysts.4

Lastly, cystic lung diseases can occur as part of a multiorgan or systemic illness in which the lung is one of the organs involved. Although usually diagnosed before the discovery of cysts or manifestations of pulmonary symptoms, they can present as a diagnostic challenge, especially when lung cysts are the initial presentation.bsence of amyloid fibrils.

In view of the features of the different types of cystic lung disease, adults with cystic lung disease can be grouped according to their typical clinical presentations (Table 2):

- Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

- Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

- Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infection

- Signs and symptoms that are primarily nonpulmonary.

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax can be manifestations of lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, or lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is characterized by abnormal cellular proliferation within the lung, kidney, lymphatic system, or any combination.5 The peak prevalence is in the third to fourth decades of life, and most patients are women of childbearing age.6 In addition to progressive dyspnea on exertion and pneumothorax, other signs and symptoms include hemoptysis, nonproductive cough, chylous pleural effusion, and ascites.7,8

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene.9 It is characterized by skin fibrofolliculomas, pulmonary cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and renal cancer.10

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis is part of the spectrum of Langerhans cell histiocytosis that, in addition to the lungs, can also involve the bone, pituitary gland, thyroid, skin, lymph nodes, and liver.11 It occurs almost exclusively in smokers, affecting individuals in their 20s and 30s, with no gender predilection.12,13 In addition to nonproductive cough and dyspnea, patients can also present with fever, anorexia, and weight loss,13 but approximately 25% of patients are asymptomatic.14

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia is an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia that, like pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is seen almost exclusively in current or former smokers, who account for about 90% of patients with this disease. It affects almost twice as many men as women.15,16 The mean age at onset is 42 to 46.15,16 In addition to insidious cough and dyspnea, digital clubbing develops in 26% to 40% of patients.16,17

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia is another rare idiopathic pneumonia, usually associated with connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome, immunodeficiencies, and viral infections.18–21 It is more common in women, presenting between the 4th and 7th decades of life, with a mean age at diagnosis of 50 to 56.18,22 In addition to progressive dyspnea and cough, other symptoms include weight loss, pleuritic pain, arthralgias, fatigue, night sweats, and fever.23

In summary, in this clinical group, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome should be considered when patients present with spontaneous pneumothorax; those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also present with skin lesions or renal cancer. In patients with progressive dyspnea and cough, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia should be considered in those with a known history of connective tissue disease or immunodeficiency. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically presents at a younger age (20 to 30 years old) than desquamative interstitial pneumonia (smokers in their 40s). Making the distinction, however, will likely require imaging with computed tomography.

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia can be manifestations of congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, or bronchogenic cyst.

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, of which there are five types, is the most common pulmonary congenital abnormality. It accounts for up to 95% of cases of congenital cystic lung disease.24,25 About 85% of cases are detected in the prenatal or perinatal periods.26 Late-onset congenital pulmonary airway malformation (arising in childhood to adulthood) presents with recurrent pneumonia in about 75% of cases and can be misdiagnosed as lung abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis, or bronchiectasis.27

Pulmonary sequestration, the second most common pulmonary congenital abnormality, is characterized by a portion of lung that does not connect to the tracheobronchial tree and has its own systemic arterial supply.24 Intralobar sequestration, which shares the pleural investment with normal lung, accounts for about 80% of cases of pulmonary sequestration.28–30 In addition to signs or symptoms of pulmonary infection, patients with pulmonary sequestration can remain asymp-

tomatic (about 25% of cases), or can present with hemoptysis or hemothorax.28–30 In adults, the typical age at presentation is between 20 and 25.29,30

Bronchogenic cyst is usually life-threatening in children. In adults, it commonly causes cough and chest pain.31 Hemoptysis, dysphagia, hoarseness, and diaphragmatic paralysis can also occur.32,33 The mean age at diagnosis in adults is 35 to 40.31,32

In summary, most cases of recurrent pneumonia with cysts are due to congenital pulmonary airway malformation. Pulmonary sequestration is the second most common cause of cystic lung disease in this group. Bronchogenic cyst is usually fatal in fetal development; smaller cysts can go unnoticed during the earlier years and are later found incidentally as imaging abnormalities in adults.

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections can be due to Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

P jirovecii pneumonia commonly develops in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and low CD4 counts, recipients of hematologic or solid-organ transplants, and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy (eg, glucocorticoids or chemotherapy).

Echinococcal infections (with Echinococcus granulosus or multilocularis species) are more common in less-developed countries such as those in South America or the Middle East, in China, or in patients who have traveled to endemic areas.34

In summary, cystic lung disease in patients with primary pulmonary infections can be diagnosed by the patient’s clinical history and risk factors for infections. Those with human immunodeficiency virus infection and other causes of immunodeficiency are predisposed to P jirovecii pneumonia. Echinococcal infections occur in those with a history of travel to an endemic area.

Primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

If the patient has primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms, think about pulmonary amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Pulmonary amyloidosis has a variety of manifestations, including tracheobronchial disease, nodular parenchymal disease, diffuse or alveolar septal pattern, pleural disease, lymphadenopathy, and pulmonary cysts.4

Light chain deposition disease shares some clinical features with amyloidosis. However, the light chain fragments in this disease do not form amyloid fibrils and therefore do not stain positively with Congo red. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ.4

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is characterized by collections of neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and pigmented hamartomas in the iris (Lisch nodules).35

In summary, patients in this group typically present with complications related to systemic involvement. Those with neurofibromatosis type 1 present with ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and neurologic manifestations. Amyloidosis and light chain deposition disease most commonly involve the renal system; their distinction will likely require tissue biopsy and Congo-red staining.

STEP 3: CHARACTERIZE THE RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Characterization of pulmonary cysts and their distribution plays a key role in the diagnosis. Radiographically, cystic lung diseases can be subclassified into two major categories according to their cystic distribution:

- Discrete (focal or multifocal)

- Diffuse (unilobular or panlobular).2,3

Discrete cystic lung diseases include congenital abnormalities, infectious diseases, and interstitial pneumonias.2,3

Diffuse, panlobular cystic lung diseases include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.7,13,36–39

In addition, other associated radiographic findings play a major role in diagnosis.

Cysts in patients presenting with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cysts are seen in nearly all cases of advanced lymphangioleiomyomatosis, typically in a diffuse pattern, varying from 2 mm to 40 mm in diameter, and uniform in shape (Figure 2A).7,8,40–42

Other radiographic features include vessels located at the periphery of the cysts (in contrast to the centrilobular pattern seen with emphysema), and chylous pleural effusions (in about 22% of patients).40 Nodules are typically not seen with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and if found represent type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Nodules measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter and favoring a centrilobular location are often seen on computed tomography. Pulmonary cysts occur in about 61% of patients.13,43 Cysts are variable in size and shape (Figure 2B), in contrast to their uniform appearance in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Most cysts are less than 10 mm in diameter; however, they can be up to 80 mm.13,43 Early in its course, nodules may predominate in the upper and middle lobes. Over time, diffuse cysts become more common and can be difficult to differentiate from advanced smoking-induced emphysema.44

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Approximately 70% to 100% of patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will have multiple pulmonary cysts detected on computed tomography. These cysts are characteristically basal and subpleural in location, with varying sizes and irregular shapes in otherwise normal lung parenchyma (Figure 2C).36,45,46

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Pulmonary cysts are present on computed tomography in about 32% of patients.47 They are usually round and less than 20 mm in diameter.48 Ground-glass opacity is present in almost all cases of desquamative interstitial pneumonia, with a diffuse pattern in 25% to 44% of patients.16,17,47

Pulmonary cysts occur in up to two-thirds of those with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. Cysts are usually multifocal and perivascular in distribution and have varying sizes and shapes (Figure 2D).22 Ground-glass opacity and poorly defined centrilobular nodules are also frequently seen. Other computed tomographic findings include thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, focal consolidation, interseptal lobular thickening, pleural thickening, and lymph node enlargement.22

In summary, in this group of patients, diffuse panlobular cysts are due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cysts due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis have a diffuse distribution, while those due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be upper-lobe-predominant and in the early stages are associated with stellate centrilobular nodules. Cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome tend to be subpleural and those due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia are perivascular in distribution.

Cysts that are incidentally found or occur in patients with recurrent pneumonia

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation types 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 3A, 3B). Cysts are typically discrete and focal or multifocal in distribution, but cases of multilobar and bilateral distribution have also been reported.27,49 The lower lobes are more often involved.49 Cysts vary in size and shape and can contain air, fluid, or both.27,49 Up to 50% of cases can occur in conjunction with pulmonary sequestration.50

Pulmonary sequestration displays an anomalous arterial supply on computed tomography (Figure 3C). Other imaging findings include mass lesions (49%), cystic lesions (29%), cavitary lesions (12%), and bronchiectasis.30 Air trapping can be seen in the adjacent lung. Lower lobe involvement accounts for more than 95% of total cases of sequestration.30 The cysts are usually discrete or focal in distribution. Misdiagnosis of pulmonary sequestration is common, and can include pulmonary abscess, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and lung cancer.30

Bronchogenic cyst. Cyst contents generally demonstrate water attenuation, or higher attenuation if filled with proteinaceous/mucoid material or calcium deposits; air-fluid levels are seen in infected cysts.32 Intrapulmonary cysts have a predilection for the lower lobes and are usually discrete or focal in distribution.31,32 Mediastinal cysts are usually homogeneous, solitary, and located in the middle mediastinum.32 Cysts vary in size from 20 to 90 mm, with a mean diameter of 40 mm.31

In summary, in this group of cystic lung diseases, characteristic computed tomographic findings will suggest the diagnosis—air-filled cysts of varying sizes for congenital pulmonary airway malformation and anomalous vascular supply for pulmonary sequestration. Bronchogenic cysts will tend to have water or higher-than-water attenuation due to proteinaceous-mucoid material or calcium deposits.

Cysts in patients with signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

P jirovecii pneumonia. Between 10% and 15% of patients have cysts, and about 18% present with spontaneous pneumothorax.51 Cysts in P jirovecii pneumonia vary in size from 15 to 85 mm in diameter and tend to occur in the upper lobes (Figure 4A).51,52

Echinococcal infection. Echinococcal pulmonary cysts typically are single and located more often in the lower lobes (Figure 4B).53,54 Cysts can be complicated by air-fluid levels, hydropneumothorax, or pneumothorax, or they can turn into cavitary lesions.

The diagnoses of these pulmonary infections are usually made by clinical and computed tomographic findings and depend less on detecting and characterizing lung cysts. Patients with P jirovecii pneumonia tend to have bilateral perihilar ground-glass opacities, while air-fluid levels suggest echinococcal infections. Cysts in this group of patients tend to be discrete or focal or multifocal in distribution, and vary in size.

Cysts in patients with primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

Amyloidosis. Cyst formation is rare in amyloidosis.4 When present, cysts can be diffuse and scattered in distribution, in varying sizes (usually < 30 mm in diameter) and irregular shapes (Figure 5).55,56

Pulmonary light chain deposition disease usually presents as linear opacities and small nodules on chest computed tomography. Numerous cysts that are diffuse in distribution and have no topographic predominance can also be present. They can progress in number and size and coalesce to form irregular shapes.57

Neurofibromatosis type 1. In neurofibromatosis type 1, the most common radiographic presentations are bibasilar reticular opacities (50%), bullae (50%), and ground glass opacities (37%).58 Well-formed cysts occur in up to 25% of patients and tend to be diffuse and smaller (2 to 18 mm in diameter), with upper lobe predominance.58,59

In summary, in this group of patients, bibasilar reticular and ground-glass opacities suggest neurofibromatosis type 1, while nodules and linear opacities suggest amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease. Cysts tend to be diffuse with varying sizes.

STEP 4: PUT IT ALL TOGETHER

Diagnosis in insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

For patients who present with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax, the diagnosis of cystic lung disease can be made by characterizing the distribution, size, and shape of the cysts (Table 3).

Diffuse, panlobular distribution. Cystic lung diseases with this pattern include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In this group, cysts that are uniform in size and regular in shape are invariably due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Those with variable size and irregular shapes can be due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be smokers and their cysts tend to be upper- lobe-predominant. Those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will likely have renal cancer or skin lesions; their cysts tend to be basilar and subpleural in distribution.

Cysts that are focal or multifocal and unilobular are due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Patients with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia tend to have underlying connective tissue disease; those with desquamative interstitial pneumonia are almost always smokers. The definitive diagnosis for lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia can require a tissue biopsy.

Diagnosis in patients with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

In those who present with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia, suspicion for a congenital lung malformation should be raised. Patients with a type 1, 2, or 4 congenital pulmonary airway malformation typically have air-filled cysts in varying sizes; those with pulmonary sequestration have an anomalous arterial supply in addition to cysts that are usually located in the lower lobes. Bronchogenic cysts tend to be larger, with attenuation equal to or greater than that of water, and distinguishing them from congenital pulmonary airway malformation will likely require surgical examination.

Diagnosis in patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections

Patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections should be investigated according to clinical risk factors for P jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

Diagnosis in patients with primarily nonpulmonary presentations

The distinction between amyloidosis and neurofibromatosis type 1 can be made by the history and the clinical examination. However, a definitive diagnosis of amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease requires tissue examination for the presence or absence of amyloid fibrils.

Air-filled pulmonary lesions commonly detected on chest computed tomography. Cystic lung lesions should be distinguished from other air-filled lesions to facilitate diagnosis. Primary care physicians play an integral role in the recognition of cystic lung disease.

The differential diagnosis of cystic lung disease is broad and includes isolated pulmonary, systemic, infectious, and congenital etiologies.

Here, we aim to provide a systematic, stepwise approach to help differentiate among the various cystic lung diseases and devise an algorithm for diagnosis. In doing so, we will discuss the clinical and radiographic features of many of these diseases:

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Interstitial pneumonia (desquamative interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia)

- Congenital cystic lung disease (congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, bronchogenic cyst) Pulmonary infection

- Systemic disease (amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, neurofibromatosis type 1).

STEP 1: RULE OUT CYST-MIMICS

A pulmonary cyst is a round, circumscribed space surrounded by an epithelial or fibrous wall of variable thickness.1 On chest radiography and computed tomography, a cyst appears as a round parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung.1 Cysts vary in wall thickness but usually have a thin wall (< 2 mm) and occur without associated pulmonary emphysema.1 They typically contain air but occasionally contain fluid or solid material.

A pulmonary cyst can be categorized as a bulla, bleb, or pneumatocele.

Bullae are larger than 1 cm in diameter, sharply demarcated by a thin wall, and usually accompanied by emphysematous changes in the adjacent lung.1

Blebs are no larger than 1 cm in diameter, are located within the visceral pleura or the subpleural space, and appear on computed tomography as thin-walled air spaces that are contiguous with the pleura.1 The distinction between a bleb and a bulla is of little clinical importance, and is often unnecessary.

Pneumatoceles are cysts that are frequently caused by acute pneumonia, trauma, or aspiration of hydrocarbon fluid, and are usually transient.1

Mimics of pulmonary cysts include pulmonary cavities, emphysema, loculated pneumothoraces, honeycomb lung, and bronchiectasis (Figure 1).2

Pulmonary cavities differ from cysts in that their walls are typically thicker (usually > 4 mm).3

Emphysema differs from cystic lung disease as it typically leads to focal areas or regions of decreased lung attenuation that do not have defined walls.1

Honeycombing refers to a cluster or row of cysts, 1 to 3 mm in wall thickness and typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter, that are associated with end-stage lung fibrosis.1 They are typically subpleural in distribution and are accompanied by fibrotic features such as reticulation and traction bronchiectasis.1

Bronchiectasis is dilation and distortion of bronchi and bronchioles and can be mistaken for cysts when viewed en face.1

Loculated pneumothoraces can also mimic pulmonary cysts, but they typically fail to adhere to a defined anatomic unit and are subpleural in distribution.

STEP 2: CHARACTERIZE THE CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Clinical signs and symptoms of cystic lung disease play a key role in diagnosis (Table 1). For instance, spontaneous pneumothorax is commonly associated with diffuse cystic lung disease (lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome), while insidious dyspnea, with or without associated pneumothorax, is usually associated with the interstitial pneumonias (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia).

In addition, congenital abnormalities of the lung can lead to cyst formation. These abnormalities, especially when associated with other congenital abnormalities, are often diagnosed in the prenatal and perinatal periods. However, some remain undetected until incidentally found later in adulthood or if superimposing infection develops.

Primary pulmonary infections can also cause parenchymal necrosis, which in turn cavitates or forms cysts.4

Lastly, cystic lung diseases can occur as part of a multiorgan or systemic illness in which the lung is one of the organs involved. Although usually diagnosed before the discovery of cysts or manifestations of pulmonary symptoms, they can present as a diagnostic challenge, especially when lung cysts are the initial presentation.bsence of amyloid fibrils.

In view of the features of the different types of cystic lung disease, adults with cystic lung disease can be grouped according to their typical clinical presentations (Table 2):

- Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

- Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

- Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infection

- Signs and symptoms that are primarily nonpulmonary.

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax can be manifestations of lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, or lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is characterized by abnormal cellular proliferation within the lung, kidney, lymphatic system, or any combination.5 The peak prevalence is in the third to fourth decades of life, and most patients are women of childbearing age.6 In addition to progressive dyspnea on exertion and pneumothorax, other signs and symptoms include hemoptysis, nonproductive cough, chylous pleural effusion, and ascites.7,8

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene.9 It is characterized by skin fibrofolliculomas, pulmonary cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and renal cancer.10

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis is part of the spectrum of Langerhans cell histiocytosis that, in addition to the lungs, can also involve the bone, pituitary gland, thyroid, skin, lymph nodes, and liver.11 It occurs almost exclusively in smokers, affecting individuals in their 20s and 30s, with no gender predilection.12,13 In addition to nonproductive cough and dyspnea, patients can also present with fever, anorexia, and weight loss,13 but approximately 25% of patients are asymptomatic.14

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia is an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia that, like pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is seen almost exclusively in current or former smokers, who account for about 90% of patients with this disease. It affects almost twice as many men as women.15,16 The mean age at onset is 42 to 46.15,16 In addition to insidious cough and dyspnea, digital clubbing develops in 26% to 40% of patients.16,17

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia is another rare idiopathic pneumonia, usually associated with connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome, immunodeficiencies, and viral infections.18–21 It is more common in women, presenting between the 4th and 7th decades of life, with a mean age at diagnosis of 50 to 56.18,22 In addition to progressive dyspnea and cough, other symptoms include weight loss, pleuritic pain, arthralgias, fatigue, night sweats, and fever.23

In summary, in this clinical group, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome should be considered when patients present with spontaneous pneumothorax; those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also present with skin lesions or renal cancer. In patients with progressive dyspnea and cough, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia should be considered in those with a known history of connective tissue disease or immunodeficiency. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically presents at a younger age (20 to 30 years old) than desquamative interstitial pneumonia (smokers in their 40s). Making the distinction, however, will likely require imaging with computed tomography.

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

Incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia can be manifestations of congenital pulmonary airway malformation, pulmonary sequestration, or bronchogenic cyst.

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, of which there are five types, is the most common pulmonary congenital abnormality. It accounts for up to 95% of cases of congenital cystic lung disease.24,25 About 85% of cases are detected in the prenatal or perinatal periods.26 Late-onset congenital pulmonary airway malformation (arising in childhood to adulthood) presents with recurrent pneumonia in about 75% of cases and can be misdiagnosed as lung abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis, or bronchiectasis.27

Pulmonary sequestration, the second most common pulmonary congenital abnormality, is characterized by a portion of lung that does not connect to the tracheobronchial tree and has its own systemic arterial supply.24 Intralobar sequestration, which shares the pleural investment with normal lung, accounts for about 80% of cases of pulmonary sequestration.28–30 In addition to signs or symptoms of pulmonary infection, patients with pulmonary sequestration can remain asymp-

tomatic (about 25% of cases), or can present with hemoptysis or hemothorax.28–30 In adults, the typical age at presentation is between 20 and 25.29,30

Bronchogenic cyst is usually life-threatening in children. In adults, it commonly causes cough and chest pain.31 Hemoptysis, dysphagia, hoarseness, and diaphragmatic paralysis can also occur.32,33 The mean age at diagnosis in adults is 35 to 40.31,32

In summary, most cases of recurrent pneumonia with cysts are due to congenital pulmonary airway malformation. Pulmonary sequestration is the second most common cause of cystic lung disease in this group. Bronchogenic cyst is usually fatal in fetal development; smaller cysts can go unnoticed during the earlier years and are later found incidentally as imaging abnormalities in adults.

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

Signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections can be due to Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

P jirovecii pneumonia commonly develops in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and low CD4 counts, recipients of hematologic or solid-organ transplants, and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy (eg, glucocorticoids or chemotherapy).

Echinococcal infections (with Echinococcus granulosus or multilocularis species) are more common in less-developed countries such as those in South America or the Middle East, in China, or in patients who have traveled to endemic areas.34

In summary, cystic lung disease in patients with primary pulmonary infections can be diagnosed by the patient’s clinical history and risk factors for infections. Those with human immunodeficiency virus infection and other causes of immunodeficiency are predisposed to P jirovecii pneumonia. Echinococcal infections occur in those with a history of travel to an endemic area.

Primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

If the patient has primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms, think about pulmonary amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Pulmonary amyloidosis has a variety of manifestations, including tracheobronchial disease, nodular parenchymal disease, diffuse or alveolar septal pattern, pleural disease, lymphadenopathy, and pulmonary cysts.4

Light chain deposition disease shares some clinical features with amyloidosis. However, the light chain fragments in this disease do not form amyloid fibrils and therefore do not stain positively with Congo red. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ.4

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is characterized by collections of neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and pigmented hamartomas in the iris (Lisch nodules).35

In summary, patients in this group typically present with complications related to systemic involvement. Those with neurofibromatosis type 1 present with ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and neurologic manifestations. Amyloidosis and light chain deposition disease most commonly involve the renal system; their distinction will likely require tissue biopsy and Congo-red staining.

STEP 3: CHARACTERIZE THE RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Characterization of pulmonary cysts and their distribution plays a key role in the diagnosis. Radiographically, cystic lung diseases can be subclassified into two major categories according to their cystic distribution:

- Discrete (focal or multifocal)

- Diffuse (unilobular or panlobular).2,3

Discrete cystic lung diseases include congenital abnormalities, infectious diseases, and interstitial pneumonias.2,3

Diffuse, panlobular cystic lung diseases include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, amyloidosis, light chain deposition disease, and neurofibromatosis type 1.7,13,36–39

In addition, other associated radiographic findings play a major role in diagnosis.

Cysts in patients presenting with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cysts are seen in nearly all cases of advanced lymphangioleiomyomatosis, typically in a diffuse pattern, varying from 2 mm to 40 mm in diameter, and uniform in shape (Figure 2A).7,8,40–42

Other radiographic features include vessels located at the periphery of the cysts (in contrast to the centrilobular pattern seen with emphysema), and chylous pleural effusions (in about 22% of patients).40 Nodules are typically not seen with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and if found represent type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Nodules measuring 1 to 10 mm in diameter and favoring a centrilobular location are often seen on computed tomography. Pulmonary cysts occur in about 61% of patients.13,43 Cysts are variable in size and shape (Figure 2B), in contrast to their uniform appearance in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Most cysts are less than 10 mm in diameter; however, they can be up to 80 mm.13,43 Early in its course, nodules may predominate in the upper and middle lobes. Over time, diffuse cysts become more common and can be difficult to differentiate from advanced smoking-induced emphysema.44

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Approximately 70% to 100% of patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will have multiple pulmonary cysts detected on computed tomography. These cysts are characteristically basal and subpleural in location, with varying sizes and irregular shapes in otherwise normal lung parenchyma (Figure 2C).36,45,46

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Pulmonary cysts are present on computed tomography in about 32% of patients.47 They are usually round and less than 20 mm in diameter.48 Ground-glass opacity is present in almost all cases of desquamative interstitial pneumonia, with a diffuse pattern in 25% to 44% of patients.16,17,47

Pulmonary cysts occur in up to two-thirds of those with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. Cysts are usually multifocal and perivascular in distribution and have varying sizes and shapes (Figure 2D).22 Ground-glass opacity and poorly defined centrilobular nodules are also frequently seen. Other computed tomographic findings include thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, focal consolidation, interseptal lobular thickening, pleural thickening, and lymph node enlargement.22

In summary, in this group of patients, diffuse panlobular cysts are due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cysts due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis have a diffuse distribution, while those due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be upper-lobe-predominant and in the early stages are associated with stellate centrilobular nodules. Cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome tend to be subpleural and those due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia are perivascular in distribution.

Cysts that are incidentally found or occur in patients with recurrent pneumonia

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation types 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 3A, 3B). Cysts are typically discrete and focal or multifocal in distribution, but cases of multilobar and bilateral distribution have also been reported.27,49 The lower lobes are more often involved.49 Cysts vary in size and shape and can contain air, fluid, or both.27,49 Up to 50% of cases can occur in conjunction with pulmonary sequestration.50

Pulmonary sequestration displays an anomalous arterial supply on computed tomography (Figure 3C). Other imaging findings include mass lesions (49%), cystic lesions (29%), cavitary lesions (12%), and bronchiectasis.30 Air trapping can be seen in the adjacent lung. Lower lobe involvement accounts for more than 95% of total cases of sequestration.30 The cysts are usually discrete or focal in distribution. Misdiagnosis of pulmonary sequestration is common, and can include pulmonary abscess, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and lung cancer.30

Bronchogenic cyst. Cyst contents generally demonstrate water attenuation, or higher attenuation if filled with proteinaceous/mucoid material or calcium deposits; air-fluid levels are seen in infected cysts.32 Intrapulmonary cysts have a predilection for the lower lobes and are usually discrete or focal in distribution.31,32 Mediastinal cysts are usually homogeneous, solitary, and located in the middle mediastinum.32 Cysts vary in size from 20 to 90 mm, with a mean diameter of 40 mm.31

In summary, in this group of cystic lung diseases, characteristic computed tomographic findings will suggest the diagnosis—air-filled cysts of varying sizes for congenital pulmonary airway malformation and anomalous vascular supply for pulmonary sequestration. Bronchogenic cysts will tend to have water or higher-than-water attenuation due to proteinaceous-mucoid material or calcium deposits.

Cysts in patients with signs and symptoms of primary pulmonary infections

P jirovecii pneumonia. Between 10% and 15% of patients have cysts, and about 18% present with spontaneous pneumothorax.51 Cysts in P jirovecii pneumonia vary in size from 15 to 85 mm in diameter and tend to occur in the upper lobes (Figure 4A).51,52

Echinococcal infection. Echinococcal pulmonary cysts typically are single and located more often in the lower lobes (Figure 4B).53,54 Cysts can be complicated by air-fluid levels, hydropneumothorax, or pneumothorax, or they can turn into cavitary lesions.

The diagnoses of these pulmonary infections are usually made by clinical and computed tomographic findings and depend less on detecting and characterizing lung cysts. Patients with P jirovecii pneumonia tend to have bilateral perihilar ground-glass opacities, while air-fluid levels suggest echinococcal infections. Cysts in this group of patients tend to be discrete or focal or multifocal in distribution, and vary in size.

Cysts in patients with primarily nonpulmonary signs and symptoms

Amyloidosis. Cyst formation is rare in amyloidosis.4 When present, cysts can be diffuse and scattered in distribution, in varying sizes (usually < 30 mm in diameter) and irregular shapes (Figure 5).55,56

Pulmonary light chain deposition disease usually presents as linear opacities and small nodules on chest computed tomography. Numerous cysts that are diffuse in distribution and have no topographic predominance can also be present. They can progress in number and size and coalesce to form irregular shapes.57

Neurofibromatosis type 1. In neurofibromatosis type 1, the most common radiographic presentations are bibasilar reticular opacities (50%), bullae (50%), and ground glass opacities (37%).58 Well-formed cysts occur in up to 25% of patients and tend to be diffuse and smaller (2 to 18 mm in diameter), with upper lobe predominance.58,59

In summary, in this group of patients, bibasilar reticular and ground-glass opacities suggest neurofibromatosis type 1, while nodules and linear opacities suggest amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease. Cysts tend to be diffuse with varying sizes.

STEP 4: PUT IT ALL TOGETHER

Diagnosis in insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax

For patients who present with insidious dyspnea or spontaneous pneumothorax, the diagnosis of cystic lung disease can be made by characterizing the distribution, size, and shape of the cysts (Table 3).

Diffuse, panlobular distribution. Cystic lung diseases with this pattern include lymphangioleiomyomatosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In this group, cysts that are uniform in size and regular in shape are invariably due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Those with variable size and irregular shapes can be due to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis tend to be smokers and their cysts tend to be upper- lobe-predominant. Those with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome will likely have renal cancer or skin lesions; their cysts tend to be basilar and subpleural in distribution.

Cysts that are focal or multifocal and unilobular are due to lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Patients with lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia tend to have underlying connective tissue disease; those with desquamative interstitial pneumonia are almost always smokers. The definitive diagnosis for lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia or desquamative interstitial pneumonia can require a tissue biopsy.

Diagnosis in patients with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia

In those who present with incidentally found cysts or recurrent pneumonia, suspicion for a congenital lung malformation should be raised. Patients with a type 1, 2, or 4 congenital pulmonary airway malformation typically have air-filled cysts in varying sizes; those with pulmonary sequestration have an anomalous arterial supply in addition to cysts that are usually located in the lower lobes. Bronchogenic cysts tend to be larger, with attenuation equal to or greater than that of water, and distinguishing them from congenital pulmonary airway malformation will likely require surgical examination.

Diagnosis in patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections

Patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary infections should be investigated according to clinical risk factors for P jirovecii pneumonia or echinococcal infections.

Diagnosis in patients with primarily nonpulmonary presentations

The distinction between amyloidosis and neurofibromatosis type 1 can be made by the history and the clinical examination. However, a definitive diagnosis of amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease requires tissue examination for the presence or absence of amyloid fibrils.

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008; 246:697–722.

- Cosgrove GP, Frankel SK, Brown KK. Challenges in pulmonary fibrosis. 3: cystic lung disease. Thorax 2007; 62:820–829.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78:744–752.

- Ryu JH, Tian X, Baqir M, Xu K. Diffuse cystic lung diseases. Front Med 2013; 7:316–327.

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest 2008; 133:507–516.

- Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al; Review Panel of the ERS LAM Task Force. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:14–26.