User login

Taking a look at neurologist burnout

There’s a lot in the news these days about doctor burnout. More specifically, neurologist burnout.

In a 2012 survey study, about 53% of neurologists reported burnout, which was third among all specialties surveyed, behind emergency medicine physicians and general internists. Neurologists also reported the fourth lowest job satisfaction with work-life balance, with about 41% satisfied that work leaves enough time for personal or family life. Neurology was the only one out of five specialties with the highest rates of burnout that was also among the five specialties with the lowest work-life balance.

Granted, the term “burnout” can mean a lot, but these days seems to refer to the fall of the American physician: Overworked, with rising costs, and falling reimbursements, sandwiched between patients who want to be cured immediately and those who want to sue us, and even on a good day facing a litany of terrible diseases.

Heck, I’d be burned out, too. Maybe I am.

Some say this is from the worries of solo practice, since we’re usually more pressed for time and money. I disagree, as I’ve seen it on both sides.

Recently, I saw my own internist. Six months ago she closed her own solo practice to join a large, hospital-owned group. She looked exhausted, worse than I’d ever seen her. She told me that she now gets a secure paycheck, but her stress level is worse. The hospital sets her schedule, tells her how much time she can spend with each patient, gives her quotas she has to meet, and has supplied an electronic health record (EHR) system that’s less than user friendly. (Personally, all of the ones I’ve tried are terrible.) When she goes home, she told me that now after dinner she still has to log on and do 2-3 more hours of charting just to catch up.

The grass is always greener. In her, I see a doctor who doesn’t have to watch each penny and worry about whether she’ll get a paycheck next week. In me, she looks at someone who’s free to pick their vacation days and isn’t chained to a quota system and a burdensome EHR.

Who’s right? I suppose it depends on what your life preferences are. Are we both burned out? We probably are, but in different ways.

But why the high rate of burnout for neurologists? Likely because of the issues I mentioned above. For myself, I’ve seen my salary drop 50% since its highest point in 2005. We’re faced with rising costs (like many other businesses). Unlike other professions, however, we don’t have much control over our reimbursement. Peculiar to medicine is the simple fact that what we charge has no bearing on what we get paid. Those rates are set by factors over which we have no control. Worse, they’re often set by politicians and insurance executives, who see us as the enemy.

There’s also the way reimbursements are set-up: they still favor docs who do a lot of procedures. While neurologists have a few, most of our job is thinking. And that’s not compensated nearly as well as jabbing needles and scalpels in people.

Then you get beyond financial issues. Many of us go through the day feeling like we have a target on our backs, in fear of patients becoming plaintiffs. What else? The nature of our field is such that we deal with diseases that are often challenging to diagnose and sometimes difficult, if not impossible, to treat. Yet, we still have to put on our best show and attitude for those afflicted. Part of why they come to us is to have questions answered and be given any glimmer of hope we can find.

In spite of this, the majority of us go on. Even burned out, we came here to help others. It’s part of what makes us tick and drives us to look in the mirror and head to the office. I wouldn’t trade what I do for anything. But I wish I could do it in a less adversarial world where I’m forced to choose between freedom and a (even temporary) sense of security.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

There’s a lot in the news these days about doctor burnout. More specifically, neurologist burnout.

In a 2012 survey study, about 53% of neurologists reported burnout, which was third among all specialties surveyed, behind emergency medicine physicians and general internists. Neurologists also reported the fourth lowest job satisfaction with work-life balance, with about 41% satisfied that work leaves enough time for personal or family life. Neurology was the only one out of five specialties with the highest rates of burnout that was also among the five specialties with the lowest work-life balance.

Granted, the term “burnout” can mean a lot, but these days seems to refer to the fall of the American physician: Overworked, with rising costs, and falling reimbursements, sandwiched between patients who want to be cured immediately and those who want to sue us, and even on a good day facing a litany of terrible diseases.

Heck, I’d be burned out, too. Maybe I am.

Some say this is from the worries of solo practice, since we’re usually more pressed for time and money. I disagree, as I’ve seen it on both sides.

Recently, I saw my own internist. Six months ago she closed her own solo practice to join a large, hospital-owned group. She looked exhausted, worse than I’d ever seen her. She told me that she now gets a secure paycheck, but her stress level is worse. The hospital sets her schedule, tells her how much time she can spend with each patient, gives her quotas she has to meet, and has supplied an electronic health record (EHR) system that’s less than user friendly. (Personally, all of the ones I’ve tried are terrible.) When she goes home, she told me that now after dinner she still has to log on and do 2-3 more hours of charting just to catch up.

The grass is always greener. In her, I see a doctor who doesn’t have to watch each penny and worry about whether she’ll get a paycheck next week. In me, she looks at someone who’s free to pick their vacation days and isn’t chained to a quota system and a burdensome EHR.

Who’s right? I suppose it depends on what your life preferences are. Are we both burned out? We probably are, but in different ways.

But why the high rate of burnout for neurologists? Likely because of the issues I mentioned above. For myself, I’ve seen my salary drop 50% since its highest point in 2005. We’re faced with rising costs (like many other businesses). Unlike other professions, however, we don’t have much control over our reimbursement. Peculiar to medicine is the simple fact that what we charge has no bearing on what we get paid. Those rates are set by factors over which we have no control. Worse, they’re often set by politicians and insurance executives, who see us as the enemy.

There’s also the way reimbursements are set-up: they still favor docs who do a lot of procedures. While neurologists have a few, most of our job is thinking. And that’s not compensated nearly as well as jabbing needles and scalpels in people.

Then you get beyond financial issues. Many of us go through the day feeling like we have a target on our backs, in fear of patients becoming plaintiffs. What else? The nature of our field is such that we deal with diseases that are often challenging to diagnose and sometimes difficult, if not impossible, to treat. Yet, we still have to put on our best show and attitude for those afflicted. Part of why they come to us is to have questions answered and be given any glimmer of hope we can find.

In spite of this, the majority of us go on. Even burned out, we came here to help others. It’s part of what makes us tick and drives us to look in the mirror and head to the office. I wouldn’t trade what I do for anything. But I wish I could do it in a less adversarial world where I’m forced to choose between freedom and a (even temporary) sense of security.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

There’s a lot in the news these days about doctor burnout. More specifically, neurologist burnout.

In a 2012 survey study, about 53% of neurologists reported burnout, which was third among all specialties surveyed, behind emergency medicine physicians and general internists. Neurologists also reported the fourth lowest job satisfaction with work-life balance, with about 41% satisfied that work leaves enough time for personal or family life. Neurology was the only one out of five specialties with the highest rates of burnout that was also among the five specialties with the lowest work-life balance.

Granted, the term “burnout” can mean a lot, but these days seems to refer to the fall of the American physician: Overworked, with rising costs, and falling reimbursements, sandwiched between patients who want to be cured immediately and those who want to sue us, and even on a good day facing a litany of terrible diseases.

Heck, I’d be burned out, too. Maybe I am.

Some say this is from the worries of solo practice, since we’re usually more pressed for time and money. I disagree, as I’ve seen it on both sides.

Recently, I saw my own internist. Six months ago she closed her own solo practice to join a large, hospital-owned group. She looked exhausted, worse than I’d ever seen her. She told me that she now gets a secure paycheck, but her stress level is worse. The hospital sets her schedule, tells her how much time she can spend with each patient, gives her quotas she has to meet, and has supplied an electronic health record (EHR) system that’s less than user friendly. (Personally, all of the ones I’ve tried are terrible.) When she goes home, she told me that now after dinner she still has to log on and do 2-3 more hours of charting just to catch up.

The grass is always greener. In her, I see a doctor who doesn’t have to watch each penny and worry about whether she’ll get a paycheck next week. In me, she looks at someone who’s free to pick their vacation days and isn’t chained to a quota system and a burdensome EHR.

Who’s right? I suppose it depends on what your life preferences are. Are we both burned out? We probably are, but in different ways.

But why the high rate of burnout for neurologists? Likely because of the issues I mentioned above. For myself, I’ve seen my salary drop 50% since its highest point in 2005. We’re faced with rising costs (like many other businesses). Unlike other professions, however, we don’t have much control over our reimbursement. Peculiar to medicine is the simple fact that what we charge has no bearing on what we get paid. Those rates are set by factors over which we have no control. Worse, they’re often set by politicians and insurance executives, who see us as the enemy.

There’s also the way reimbursements are set-up: they still favor docs who do a lot of procedures. While neurologists have a few, most of our job is thinking. And that’s not compensated nearly as well as jabbing needles and scalpels in people.

Then you get beyond financial issues. Many of us go through the day feeling like we have a target on our backs, in fear of patients becoming plaintiffs. What else? The nature of our field is such that we deal with diseases that are often challenging to diagnose and sometimes difficult, if not impossible, to treat. Yet, we still have to put on our best show and attitude for those afflicted. Part of why they come to us is to have questions answered and be given any glimmer of hope we can find.

In spite of this, the majority of us go on. Even burned out, we came here to help others. It’s part of what makes us tick and drives us to look in the mirror and head to the office. I wouldn’t trade what I do for anything. But I wish I could do it in a less adversarial world where I’m forced to choose between freedom and a (even temporary) sense of security.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Cutaneous Side Effects of Chemotherapy in Pediatric Oncology Patients

Pediatric oncology patients can present with various skin lesions related to both their primary disease and immunosuppressive treatments. In the majority of cases, cutaneous findings are associated with the use of chemotherapeutic agents. The toxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents, which generally are associated with treatment of solid organ malignancies (eg, liver, kidneys), can be detected by oncologists using clinical signs and laboratory tests.1-3 However, it also is important for dermatologists to recognize and evaluate cutaneous side effects associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Reports in the literature of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients generally are limited to case studies. This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric oncology patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed through the collaboration of the departments of dermatology and venereology and pediatric oncology in the Faculty of Medicine at Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. Sixty-five pediatric oncology patients who were scheduled to undergo chemotherapy from May 2011 to May 2013 were included in the study. Clinical examination of dermatologic findings was conducted at baseline (prior to beginning chemotherapy) and at months 1, 3, and 6 of treatment. Patients were examined a total of 4 times during the study. Patients with a history of skin disease prior to diagnosis of their malignancy were excluded, as the study aimed to evaluate cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy. Patients who developed cutaneous side effects during the study period were photographed. Skin biopsy was performed to confirm clinical diagnosis. Patients were split into 5 groups according to oncological diagnoses, including hematological malignancies, solid organ tumors, bone and soft tissue tumors, central nervous system tumors, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Data regarding age, gender, treatments administered (ie, chemotherapeutics, antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals), and dermatologic signs were recorded. Mucocutaneous findings were classified as infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal) lesions, bullous lesions, inflammatory dermatoses (eg, diaper dermatitis, asteatotic eczema, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis), xeroderma, petechiae/ecchymoses, nail signs, alopecia, mucositis, cheilitis, oral aphthae, drug reactions confirmed by histopathology, cushingoid signs (eg, striae, acneform eruption, hypertrichosis), and cutaneous hyperpigmentation.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 15.0 and χ2 test was applied to the analysis.

Results

Of 65 patients, 62 completed the study and were included in the analysis. Three patients were excluded from the results, as 2 patients died during treatment and 1 patient withdrew from the study prior to completion. Twenty-seven (43.5%) patients were female and 35 (56.5%) were male ranging in age from 1 to 17 years (mean age, 8.14 years; median age [standard deviation], 7.25 [5.42] years). There were 31 (50%) patients in the hematological malignancies group, 11 (17.7%) in the solid organ tumors group, 10 (16.1%) in the bone and soft tissue tumors group, and 9 (14.5%) in the central nervous system tumors group; Langerhans cell histiocytosis was diagnosed in 1 (1.6%) patient. Hodgkin lymphoma made up 29.0% (n=9) of hematological malignancies. Other hematological malignancies included acute myeloblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), T-cell lymphoma (n=5 [16.1%]), non-Hodgkin lym-phoma (n=1 [3.2%]), anaplastic giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]), and diffuse giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]).

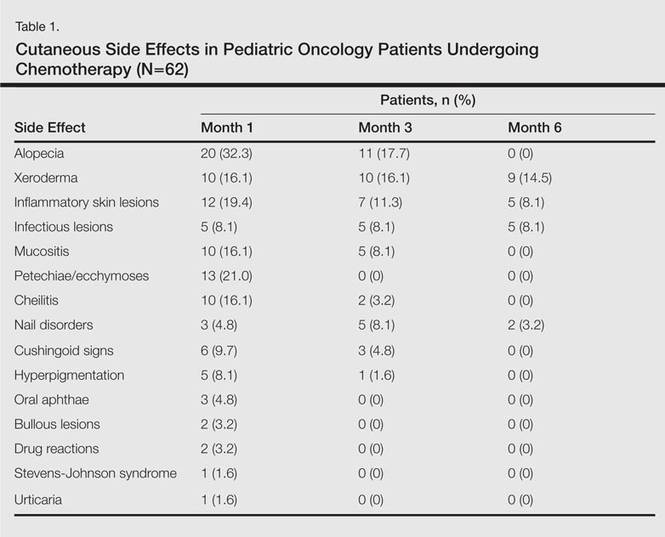

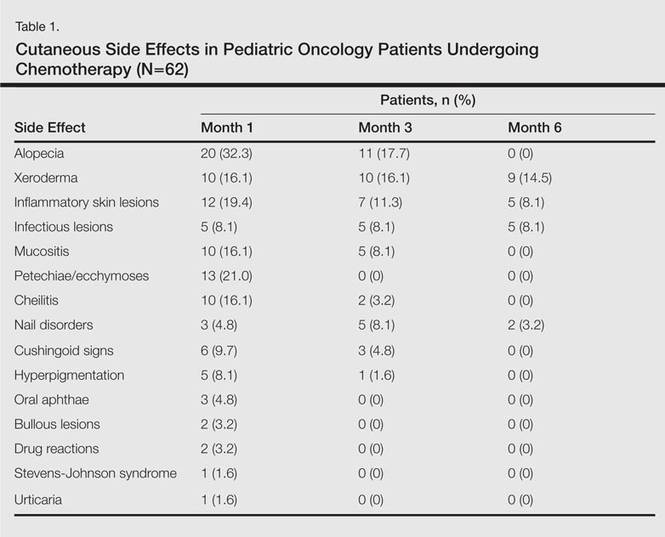

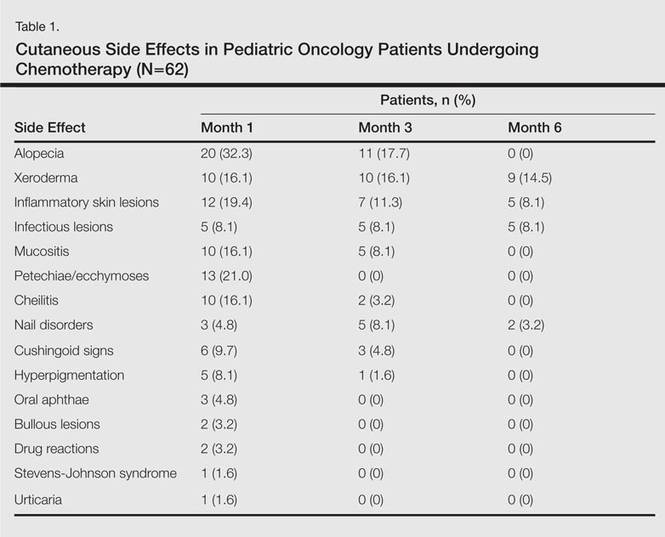

In addition to chemotherapeutic agents, 7 (11.3%) patients in this study also received antibiotics and 3 (4.8%) received antivirals. The most frequently employed chemotherapeutic agents were vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine, etoposide, and dexamethasone. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, asparaginase, carboplatin, procarbazine, daunorubicin, actinomycin D, vinblastine, cisplatin, bleomycin, idarubicin, 6-mercaptopurine, temozolamide, and cyclosporine also were administered. The most commonly encountered dermatological side effects were alopecia, xeroderma, inflammatory skin lesions, infectious lesions, and mucositis, respectively (Table 1). Cutaneous side effects were frequently seen at months 1 and 3 of treatment.

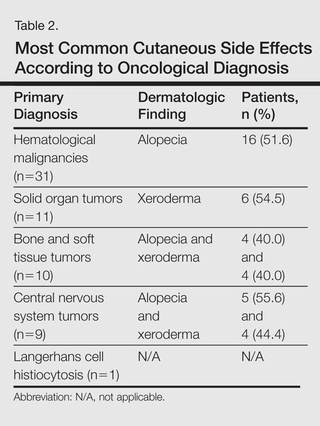

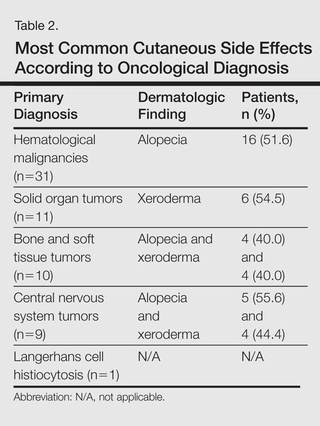

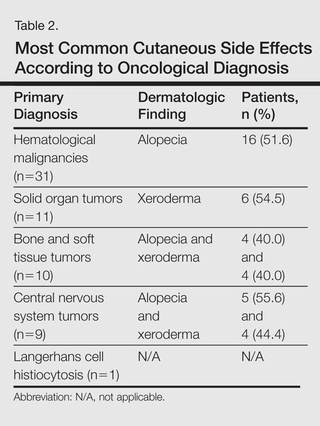

The most commonly encountered dermatologic side effect was alopecia (31/62 [50%]). Anagen effluvium (Figure 1) was detected in half of the cases, while complete scalp hair loss was noted in the rest. Alopecia was encountered more commonly in cases with central nervous system tumors (5/9 [55.6%]) and hematological malignancies (16/31 [51.6%])(Table 2).

The second most commonly encountered side effect was xeroderma (29/62 [46.8%])(Figure 2). This side effect was most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (6/11 [54.5%]) and central nervous system tumors (4/9 [44.4%]), and occurred less frequently with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/10 [40.0%]).

Findings of eczema accounted for the majority of inflammatory lesions, which were the third most commonly encountered side effects. Among 24 cases of inflammatory skin lesions, 8 patients (33.3%) had diaper dermatitis, 7 (29.2%) had asteatotic eczema, 6 (25.0%) had contact dermatitis, and 3 (12.5%) had seborrheic dermatitis. Although inflammatory skin lesions were commonly encountered in patients with hematological malignancies (14/31 [45.2%]), the difference was not statistically significant.

Mucositis and oral aphthous lesions were observed in 15 (24.2%) and 3 (4.8%) patients, respectively. Nail signs were noted in 10 (16.1%) patients; 4 patients had transverse streaks on the nail plates, 3 had linear streaks, 2 had nail plate fragility, and 1 had increased pigmentation at the nail bed and periungual area. Figure 3 shows linear streaks on the nail plate. These side effects were most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (5/11 [45.5%]); however, the difference was not statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups.

Dermatologic signs with infectious origins were detected in 15 (24.2%) patients; 2 patients had herpes labialis, 2 had verruca vulgaris, 3 had bacterial folliculitis, 1 had acute paronychia, 1 had soft tissue infection, 2 had tinea versicolor, and 4 had mucocutaneous candidiasis. Dermatologic side effects due to infectious causes were more commonly encountered in patients with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/11 [36.4%]), and the difference was statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups (P=.04).

Petechiae and ecchymotic lesions were present in 13 (21.0%) patients. These side effects occurred mainly in the first month of chemotherapy, namely when patients were in the pancytopenic phase.

Comment

Variability among the oncological diagnosis and drugs used in treatment as well as increased numbers of chemotherapeutic agents available have led to many side effects and complications in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy.1,2 Comprehensive studies regarding the cutaneous side effects of chemotherapeuticagents in cancer treatment have been conducted in adult patients. Side effects in pediatric patients have only been documented in case reports in the literature. In our study of pediatric oncology patients undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, the most commonly observed dermatologic side effect was alopecia, followed by xeroderma, inflammatory lesions, infectious lesions, mucositis, petechiae/ecchymoses, cheilitis, nail disorders, cushingoid signs, oral aphthae, bullous lesions, and drug reactions confirmed histopathologically (Table 1).

Because the common effects of chemotherapeutic agents used in cancer treatment are greatest in areas of rapidly dividing cells, the skin and skin appendages frequently are affected by these drugs.1-3 Cutaneous signs are frequently observed, especially in regions with increased mitotic activity such as the hair, mucosa, and nails.

Kamil et al1 reported that the incidence of alopecia was 64.3% (74/115) in a study of adult cancer patients who underwent chemotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents that have commonly caused alopecia are vincristine, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cytarabine, and carboplatin.1,2 In our study, alopecia was noted in 31 (50.0%) patients, especially with the use of vincristine (7/31 [22.6%]), daunorubicin (8/31 [25.8%]), doxorubicin (6/31 [19.4%]), and cyclophosphamide (10/31 [32.3%]).

Darkening of the skin and paleness accompanied the majority of cases of xeroderma in our study. Skin dryness was in an ichthyosiform appearance and was severe in 1 patient who was diagnosed with osteosarcoma. Asteatotic eczema and cheilitis were related to skin dryness. It has been reported that acquired paraneoplastic ichthyosis can develop in hematological malignancies, primarily in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.4

The incidence of mucositis has been related to the doses of chemotherapeutic agents. Although it is a commonly encountered side effect, there is no standard treatment of mucositis; therefore, preventive care in patients undergoing chemotherapy is important. It has been reported that practicing good oral hygiene before the treatment period can decrease the incidence of mucositis.5-9 The lower incidence of mucositis in our study compared to the literature (55.6%)5 can be attributed to the lower doses of chemotherapy drugs administered to children due to their weights; they also had active oral mucosa care during chemotherapy.

Another common complication observed in our study was nail disorders. Transverse streaks commonly are encountered due to damage in the nail matrix. Other signs are increased linear streaks, longitudinal melanonychia, nail plate fragility, and onycholysis.10

Cancer patients acquire infections more frequently because of immunosuppression from chemotherapy and malignancy.11,12 In our study, cutaneous side effects with infectious causes were noted in 15 patients. Steroids, which are included in the majority of chemotherapeutic protocols, can cause cushingoid changes. Striae from rapid weight gain, acneform eruptions, hypertrichosis, and atrophy of the skin also have been observed among secondary changes to chemotherapy.1,11

Other skin signs observed in the study were acute urticaria in 1 patient (1.6%) following administration of intrathecal methotrexate; Stevens-Johnson syndrome related to voriconazole was noted in 1 (1.6%) patient.

Hyperpigmentation is a common side effect observed in oncology patients.13-15 It can be observed locally in the skin as well as the mucosa, teeth, hair, and nails, and it generally develops secondary to alkylating agents.16 Moreover, hyperpigmentation may develop in regions with occlusions (eg, electrocardiogram pads, adhesion sites of plasters), and commonly is associated with ifosfamide, etoposide, carboplatin, and cyclosporine. Although the development mechanism of hyperpigmentation related to chemotherapy drugs is not clearly known, it is thought to be due to direct toxicity, melanocyte stimulation, or postinflammatory changes.1,6,17 In our study, xeroderma was noted in some patients with hyperpigmentation; all of them had received cyclosporine and systemic steroid treatments. The other chemotherapeutics were defined as etoposide, cytarabine, dacarbazine, and ifosfamide.1 Our patients with hyperpigmentation were not taking these therapies.

Increased skin malignancies have been reported in adult cases with hematological malignancies.18 None of the patients in our study had a secondary skin malignancy, likely because we evaluated a pediatric population and the follow-up period (6 months) was too short for the development of a secondary malignancy.

Conclusion

A wide range of cutaneous side effects can be observed in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy based on oncological diagnosis and treatment protocol. Although these side effects are not fatal, they may negatively affect morbidity and can lead to emotional distress. Knowing the possible cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients and their causes is important for early diagnosis and minimal treatment.

- Kamil N, Kamil S, Ahmed SP, et al. Toxic effects of multiple anticancer drugs on skin. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:7-14.

- Alley E, Green R, Schuchter L. Cutaneous toxicities of cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:212-216.

- Ozkan A, Apak H, Celkan T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after the use of high-dose cytosine arabinoside. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:38-40.

- Rizos E, Milionis HJ, Pavlidis N, et al. Acquired ichthyosis: a paraneoplastic skin manifestation of Hodgkin’s disease. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:727.

- Otmani N, Alami R, Hessissen L, et al. Determinants of severe oral mucositis in pediatric cancer patients: a prospective study. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2011;21:210-216.

- Mateus C, Robert C. New drugs in oncology and skin toxicity [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:401-410.

- Manji A, Tomlinson D, Ethier MC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire for child self-report and importance of mucositis in children treated with chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1251-1258.

- Keefe DM. Mucositis management in patients with cancer. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;3:154-157.

- Raber-Durlacher JE, Elad S, Barasch A. Oral mucositis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:452-456.

- Utas S, Kulluk P. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:466-474.

- Ott H, Höger PH. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in pediatric cancer patients [in German]. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217(suppl 1):110-119.

- Ramphal R, Grant RM, Dzolganovski B, et al. Herpes simplex virus in febrile neutropenic children undergoing chemotherapy for cancer: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:700-704.

- Yaris N, Cakir M, Kalyoncu M, et al. Bleomycin induced hyperpigmentation with yolk sac tumor. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:505-506.

- Kleynberg RL, Sofi AA, Chaudhary RT. Hand-foot hyperpigmentation skin lesions associated with combination gemcitabine-carboplatin (GemCarbo) therapy. Am J Ther. 2011;18:261-263.

- Blaya M, Saba N. Chemotherapy-induced hyperpigmentation of the tongue. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e20.

- Anandajeya WV, Corrêa ZM, Augsburger JJ. Primary acquired melanosis with atypia treated with mitomycin C. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:285-288.

- Torres C, Wong L, Welsh O, et al. Skin manifestations associated with chemotherapy in children with hematologic malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;2:123-147.

- Mays SR, Cohen PR. Emerging dermatologic issues in the oncology patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:179-189.

Pediatric oncology patients can present with various skin lesions related to both their primary disease and immunosuppressive treatments. In the majority of cases, cutaneous findings are associated with the use of chemotherapeutic agents. The toxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents, which generally are associated with treatment of solid organ malignancies (eg, liver, kidneys), can be detected by oncologists using clinical signs and laboratory tests.1-3 However, it also is important for dermatologists to recognize and evaluate cutaneous side effects associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Reports in the literature of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients generally are limited to case studies. This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric oncology patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed through the collaboration of the departments of dermatology and venereology and pediatric oncology in the Faculty of Medicine at Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. Sixty-five pediatric oncology patients who were scheduled to undergo chemotherapy from May 2011 to May 2013 were included in the study. Clinical examination of dermatologic findings was conducted at baseline (prior to beginning chemotherapy) and at months 1, 3, and 6 of treatment. Patients were examined a total of 4 times during the study. Patients with a history of skin disease prior to diagnosis of their malignancy were excluded, as the study aimed to evaluate cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy. Patients who developed cutaneous side effects during the study period were photographed. Skin biopsy was performed to confirm clinical diagnosis. Patients were split into 5 groups according to oncological diagnoses, including hematological malignancies, solid organ tumors, bone and soft tissue tumors, central nervous system tumors, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Data regarding age, gender, treatments administered (ie, chemotherapeutics, antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals), and dermatologic signs were recorded. Mucocutaneous findings were classified as infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal) lesions, bullous lesions, inflammatory dermatoses (eg, diaper dermatitis, asteatotic eczema, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis), xeroderma, petechiae/ecchymoses, nail signs, alopecia, mucositis, cheilitis, oral aphthae, drug reactions confirmed by histopathology, cushingoid signs (eg, striae, acneform eruption, hypertrichosis), and cutaneous hyperpigmentation.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 15.0 and χ2 test was applied to the analysis.

Results

Of 65 patients, 62 completed the study and were included in the analysis. Three patients were excluded from the results, as 2 patients died during treatment and 1 patient withdrew from the study prior to completion. Twenty-seven (43.5%) patients were female and 35 (56.5%) were male ranging in age from 1 to 17 years (mean age, 8.14 years; median age [standard deviation], 7.25 [5.42] years). There were 31 (50%) patients in the hematological malignancies group, 11 (17.7%) in the solid organ tumors group, 10 (16.1%) in the bone and soft tissue tumors group, and 9 (14.5%) in the central nervous system tumors group; Langerhans cell histiocytosis was diagnosed in 1 (1.6%) patient. Hodgkin lymphoma made up 29.0% (n=9) of hematological malignancies. Other hematological malignancies included acute myeloblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), T-cell lymphoma (n=5 [16.1%]), non-Hodgkin lym-phoma (n=1 [3.2%]), anaplastic giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]), and diffuse giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]).

In addition to chemotherapeutic agents, 7 (11.3%) patients in this study also received antibiotics and 3 (4.8%) received antivirals. The most frequently employed chemotherapeutic agents were vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine, etoposide, and dexamethasone. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, asparaginase, carboplatin, procarbazine, daunorubicin, actinomycin D, vinblastine, cisplatin, bleomycin, idarubicin, 6-mercaptopurine, temozolamide, and cyclosporine also were administered. The most commonly encountered dermatological side effects were alopecia, xeroderma, inflammatory skin lesions, infectious lesions, and mucositis, respectively (Table 1). Cutaneous side effects were frequently seen at months 1 and 3 of treatment.

The most commonly encountered dermatologic side effect was alopecia (31/62 [50%]). Anagen effluvium (Figure 1) was detected in half of the cases, while complete scalp hair loss was noted in the rest. Alopecia was encountered more commonly in cases with central nervous system tumors (5/9 [55.6%]) and hematological malignancies (16/31 [51.6%])(Table 2).

The second most commonly encountered side effect was xeroderma (29/62 [46.8%])(Figure 2). This side effect was most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (6/11 [54.5%]) and central nervous system tumors (4/9 [44.4%]), and occurred less frequently with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/10 [40.0%]).

Findings of eczema accounted for the majority of inflammatory lesions, which were the third most commonly encountered side effects. Among 24 cases of inflammatory skin lesions, 8 patients (33.3%) had diaper dermatitis, 7 (29.2%) had asteatotic eczema, 6 (25.0%) had contact dermatitis, and 3 (12.5%) had seborrheic dermatitis. Although inflammatory skin lesions were commonly encountered in patients with hematological malignancies (14/31 [45.2%]), the difference was not statistically significant.

Mucositis and oral aphthous lesions were observed in 15 (24.2%) and 3 (4.8%) patients, respectively. Nail signs were noted in 10 (16.1%) patients; 4 patients had transverse streaks on the nail plates, 3 had linear streaks, 2 had nail plate fragility, and 1 had increased pigmentation at the nail bed and periungual area. Figure 3 shows linear streaks on the nail plate. These side effects were most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (5/11 [45.5%]); however, the difference was not statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups.

Dermatologic signs with infectious origins were detected in 15 (24.2%) patients; 2 patients had herpes labialis, 2 had verruca vulgaris, 3 had bacterial folliculitis, 1 had acute paronychia, 1 had soft tissue infection, 2 had tinea versicolor, and 4 had mucocutaneous candidiasis. Dermatologic side effects due to infectious causes were more commonly encountered in patients with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/11 [36.4%]), and the difference was statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups (P=.04).

Petechiae and ecchymotic lesions were present in 13 (21.0%) patients. These side effects occurred mainly in the first month of chemotherapy, namely when patients were in the pancytopenic phase.

Comment

Variability among the oncological diagnosis and drugs used in treatment as well as increased numbers of chemotherapeutic agents available have led to many side effects and complications in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy.1,2 Comprehensive studies regarding the cutaneous side effects of chemotherapeuticagents in cancer treatment have been conducted in adult patients. Side effects in pediatric patients have only been documented in case reports in the literature. In our study of pediatric oncology patients undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, the most commonly observed dermatologic side effect was alopecia, followed by xeroderma, inflammatory lesions, infectious lesions, mucositis, petechiae/ecchymoses, cheilitis, nail disorders, cushingoid signs, oral aphthae, bullous lesions, and drug reactions confirmed histopathologically (Table 1).

Because the common effects of chemotherapeutic agents used in cancer treatment are greatest in areas of rapidly dividing cells, the skin and skin appendages frequently are affected by these drugs.1-3 Cutaneous signs are frequently observed, especially in regions with increased mitotic activity such as the hair, mucosa, and nails.

Kamil et al1 reported that the incidence of alopecia was 64.3% (74/115) in a study of adult cancer patients who underwent chemotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents that have commonly caused alopecia are vincristine, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cytarabine, and carboplatin.1,2 In our study, alopecia was noted in 31 (50.0%) patients, especially with the use of vincristine (7/31 [22.6%]), daunorubicin (8/31 [25.8%]), doxorubicin (6/31 [19.4%]), and cyclophosphamide (10/31 [32.3%]).

Darkening of the skin and paleness accompanied the majority of cases of xeroderma in our study. Skin dryness was in an ichthyosiform appearance and was severe in 1 patient who was diagnosed with osteosarcoma. Asteatotic eczema and cheilitis were related to skin dryness. It has been reported that acquired paraneoplastic ichthyosis can develop in hematological malignancies, primarily in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.4

The incidence of mucositis has been related to the doses of chemotherapeutic agents. Although it is a commonly encountered side effect, there is no standard treatment of mucositis; therefore, preventive care in patients undergoing chemotherapy is important. It has been reported that practicing good oral hygiene before the treatment period can decrease the incidence of mucositis.5-9 The lower incidence of mucositis in our study compared to the literature (55.6%)5 can be attributed to the lower doses of chemotherapy drugs administered to children due to their weights; they also had active oral mucosa care during chemotherapy.

Another common complication observed in our study was nail disorders. Transverse streaks commonly are encountered due to damage in the nail matrix. Other signs are increased linear streaks, longitudinal melanonychia, nail plate fragility, and onycholysis.10

Cancer patients acquire infections more frequently because of immunosuppression from chemotherapy and malignancy.11,12 In our study, cutaneous side effects with infectious causes were noted in 15 patients. Steroids, which are included in the majority of chemotherapeutic protocols, can cause cushingoid changes. Striae from rapid weight gain, acneform eruptions, hypertrichosis, and atrophy of the skin also have been observed among secondary changes to chemotherapy.1,11

Other skin signs observed in the study were acute urticaria in 1 patient (1.6%) following administration of intrathecal methotrexate; Stevens-Johnson syndrome related to voriconazole was noted in 1 (1.6%) patient.

Hyperpigmentation is a common side effect observed in oncology patients.13-15 It can be observed locally in the skin as well as the mucosa, teeth, hair, and nails, and it generally develops secondary to alkylating agents.16 Moreover, hyperpigmentation may develop in regions with occlusions (eg, electrocardiogram pads, adhesion sites of plasters), and commonly is associated with ifosfamide, etoposide, carboplatin, and cyclosporine. Although the development mechanism of hyperpigmentation related to chemotherapy drugs is not clearly known, it is thought to be due to direct toxicity, melanocyte stimulation, or postinflammatory changes.1,6,17 In our study, xeroderma was noted in some patients with hyperpigmentation; all of them had received cyclosporine and systemic steroid treatments. The other chemotherapeutics were defined as etoposide, cytarabine, dacarbazine, and ifosfamide.1 Our patients with hyperpigmentation were not taking these therapies.

Increased skin malignancies have been reported in adult cases with hematological malignancies.18 None of the patients in our study had a secondary skin malignancy, likely because we evaluated a pediatric population and the follow-up period (6 months) was too short for the development of a secondary malignancy.

Conclusion

A wide range of cutaneous side effects can be observed in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy based on oncological diagnosis and treatment protocol. Although these side effects are not fatal, they may negatively affect morbidity and can lead to emotional distress. Knowing the possible cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients and their causes is important for early diagnosis and minimal treatment.

Pediatric oncology patients can present with various skin lesions related to both their primary disease and immunosuppressive treatments. In the majority of cases, cutaneous findings are associated with the use of chemotherapeutic agents. The toxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents, which generally are associated with treatment of solid organ malignancies (eg, liver, kidneys), can be detected by oncologists using clinical signs and laboratory tests.1-3 However, it also is important for dermatologists to recognize and evaluate cutaneous side effects associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Reports in the literature of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients generally are limited to case studies. This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics of cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric oncology patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed through the collaboration of the departments of dermatology and venereology and pediatric oncology in the Faculty of Medicine at Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. Sixty-five pediatric oncology patients who were scheduled to undergo chemotherapy from May 2011 to May 2013 were included in the study. Clinical examination of dermatologic findings was conducted at baseline (prior to beginning chemotherapy) and at months 1, 3, and 6 of treatment. Patients were examined a total of 4 times during the study. Patients with a history of skin disease prior to diagnosis of their malignancy were excluded, as the study aimed to evaluate cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy. Patients who developed cutaneous side effects during the study period were photographed. Skin biopsy was performed to confirm clinical diagnosis. Patients were split into 5 groups according to oncological diagnoses, including hematological malignancies, solid organ tumors, bone and soft tissue tumors, central nervous system tumors, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Data regarding age, gender, treatments administered (ie, chemotherapeutics, antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals), and dermatologic signs were recorded. Mucocutaneous findings were classified as infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal) lesions, bullous lesions, inflammatory dermatoses (eg, diaper dermatitis, asteatotic eczema, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis), xeroderma, petechiae/ecchymoses, nail signs, alopecia, mucositis, cheilitis, oral aphthae, drug reactions confirmed by histopathology, cushingoid signs (eg, striae, acneform eruption, hypertrichosis), and cutaneous hyperpigmentation.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 15.0 and χ2 test was applied to the analysis.

Results

Of 65 patients, 62 completed the study and were included in the analysis. Three patients were excluded from the results, as 2 patients died during treatment and 1 patient withdrew from the study prior to completion. Twenty-seven (43.5%) patients were female and 35 (56.5%) were male ranging in age from 1 to 17 years (mean age, 8.14 years; median age [standard deviation], 7.25 [5.42] years). There were 31 (50%) patients in the hematological malignancies group, 11 (17.7%) in the solid organ tumors group, 10 (16.1%) in the bone and soft tissue tumors group, and 9 (14.5%) in the central nervous system tumors group; Langerhans cell histiocytosis was diagnosed in 1 (1.6%) patient. Hodgkin lymphoma made up 29.0% (n=9) of hematological malignancies. Other hematological malignancies included acute myeloblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=7 [22.5%]), T-cell lymphoma (n=5 [16.1%]), non-Hodgkin lym-phoma (n=1 [3.2%]), anaplastic giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]), and diffuse giant cell lymphoma (n=1 [3.2%]).

In addition to chemotherapeutic agents, 7 (11.3%) patients in this study also received antibiotics and 3 (4.8%) received antivirals. The most frequently employed chemotherapeutic agents were vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine, etoposide, and dexamethasone. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, asparaginase, carboplatin, procarbazine, daunorubicin, actinomycin D, vinblastine, cisplatin, bleomycin, idarubicin, 6-mercaptopurine, temozolamide, and cyclosporine also were administered. The most commonly encountered dermatological side effects were alopecia, xeroderma, inflammatory skin lesions, infectious lesions, and mucositis, respectively (Table 1). Cutaneous side effects were frequently seen at months 1 and 3 of treatment.

The most commonly encountered dermatologic side effect was alopecia (31/62 [50%]). Anagen effluvium (Figure 1) was detected in half of the cases, while complete scalp hair loss was noted in the rest. Alopecia was encountered more commonly in cases with central nervous system tumors (5/9 [55.6%]) and hematological malignancies (16/31 [51.6%])(Table 2).

The second most commonly encountered side effect was xeroderma (29/62 [46.8%])(Figure 2). This side effect was most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (6/11 [54.5%]) and central nervous system tumors (4/9 [44.4%]), and occurred less frequently with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/10 [40.0%]).

Findings of eczema accounted for the majority of inflammatory lesions, which were the third most commonly encountered side effects. Among 24 cases of inflammatory skin lesions, 8 patients (33.3%) had diaper dermatitis, 7 (29.2%) had asteatotic eczema, 6 (25.0%) had contact dermatitis, and 3 (12.5%) had seborrheic dermatitis. Although inflammatory skin lesions were commonly encountered in patients with hematological malignancies (14/31 [45.2%]), the difference was not statistically significant.

Mucositis and oral aphthous lesions were observed in 15 (24.2%) and 3 (4.8%) patients, respectively. Nail signs were noted in 10 (16.1%) patients; 4 patients had transverse streaks on the nail plates, 3 had linear streaks, 2 had nail plate fragility, and 1 had increased pigmentation at the nail bed and periungual area. Figure 3 shows linear streaks on the nail plate. These side effects were most commonly encountered in patients with solid organ tumors (5/11 [45.5%]); however, the difference was not statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups.

Dermatologic signs with infectious origins were detected in 15 (24.2%) patients; 2 patients had herpes labialis, 2 had verruca vulgaris, 3 had bacterial folliculitis, 1 had acute paronychia, 1 had soft tissue infection, 2 had tinea versicolor, and 4 had mucocutaneous candidiasis. Dermatologic side effects due to infectious causes were more commonly encountered in patients with bone and soft tissue tumors (4/11 [36.4%]), and the difference was statistically significant when compared with the other diagnostic groups (P=.04).

Petechiae and ecchymotic lesions were present in 13 (21.0%) patients. These side effects occurred mainly in the first month of chemotherapy, namely when patients were in the pancytopenic phase.

Comment

Variability among the oncological diagnosis and drugs used in treatment as well as increased numbers of chemotherapeutic agents available have led to many side effects and complications in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy.1,2 Comprehensive studies regarding the cutaneous side effects of chemotherapeuticagents in cancer treatment have been conducted in adult patients. Side effects in pediatric patients have only been documented in case reports in the literature. In our study of pediatric oncology patients undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, the most commonly observed dermatologic side effect was alopecia, followed by xeroderma, inflammatory lesions, infectious lesions, mucositis, petechiae/ecchymoses, cheilitis, nail disorders, cushingoid signs, oral aphthae, bullous lesions, and drug reactions confirmed histopathologically (Table 1).

Because the common effects of chemotherapeutic agents used in cancer treatment are greatest in areas of rapidly dividing cells, the skin and skin appendages frequently are affected by these drugs.1-3 Cutaneous signs are frequently observed, especially in regions with increased mitotic activity such as the hair, mucosa, and nails.

Kamil et al1 reported that the incidence of alopecia was 64.3% (74/115) in a study of adult cancer patients who underwent chemotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents that have commonly caused alopecia are vincristine, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cytarabine, and carboplatin.1,2 In our study, alopecia was noted in 31 (50.0%) patients, especially with the use of vincristine (7/31 [22.6%]), daunorubicin (8/31 [25.8%]), doxorubicin (6/31 [19.4%]), and cyclophosphamide (10/31 [32.3%]).

Darkening of the skin and paleness accompanied the majority of cases of xeroderma in our study. Skin dryness was in an ichthyosiform appearance and was severe in 1 patient who was diagnosed with osteosarcoma. Asteatotic eczema and cheilitis were related to skin dryness. It has been reported that acquired paraneoplastic ichthyosis can develop in hematological malignancies, primarily in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.4

The incidence of mucositis has been related to the doses of chemotherapeutic agents. Although it is a commonly encountered side effect, there is no standard treatment of mucositis; therefore, preventive care in patients undergoing chemotherapy is important. It has been reported that practicing good oral hygiene before the treatment period can decrease the incidence of mucositis.5-9 The lower incidence of mucositis in our study compared to the literature (55.6%)5 can be attributed to the lower doses of chemotherapy drugs administered to children due to their weights; they also had active oral mucosa care during chemotherapy.

Another common complication observed in our study was nail disorders. Transverse streaks commonly are encountered due to damage in the nail matrix. Other signs are increased linear streaks, longitudinal melanonychia, nail plate fragility, and onycholysis.10

Cancer patients acquire infections more frequently because of immunosuppression from chemotherapy and malignancy.11,12 In our study, cutaneous side effects with infectious causes were noted in 15 patients. Steroids, which are included in the majority of chemotherapeutic protocols, can cause cushingoid changes. Striae from rapid weight gain, acneform eruptions, hypertrichosis, and atrophy of the skin also have been observed among secondary changes to chemotherapy.1,11

Other skin signs observed in the study were acute urticaria in 1 patient (1.6%) following administration of intrathecal methotrexate; Stevens-Johnson syndrome related to voriconazole was noted in 1 (1.6%) patient.

Hyperpigmentation is a common side effect observed in oncology patients.13-15 It can be observed locally in the skin as well as the mucosa, teeth, hair, and nails, and it generally develops secondary to alkylating agents.16 Moreover, hyperpigmentation may develop in regions with occlusions (eg, electrocardiogram pads, adhesion sites of plasters), and commonly is associated with ifosfamide, etoposide, carboplatin, and cyclosporine. Although the development mechanism of hyperpigmentation related to chemotherapy drugs is not clearly known, it is thought to be due to direct toxicity, melanocyte stimulation, or postinflammatory changes.1,6,17 In our study, xeroderma was noted in some patients with hyperpigmentation; all of them had received cyclosporine and systemic steroid treatments. The other chemotherapeutics were defined as etoposide, cytarabine, dacarbazine, and ifosfamide.1 Our patients with hyperpigmentation were not taking these therapies.

Increased skin malignancies have been reported in adult cases with hematological malignancies.18 None of the patients in our study had a secondary skin malignancy, likely because we evaluated a pediatric population and the follow-up period (6 months) was too short for the development of a secondary malignancy.

Conclusion

A wide range of cutaneous side effects can be observed in pediatric oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy based on oncological diagnosis and treatment protocol. Although these side effects are not fatal, they may negatively affect morbidity and can lead to emotional distress. Knowing the possible cutaneous side effects of chemotherapy in pediatric patients and their causes is important for early diagnosis and minimal treatment.

- Kamil N, Kamil S, Ahmed SP, et al. Toxic effects of multiple anticancer drugs on skin. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:7-14.

- Alley E, Green R, Schuchter L. Cutaneous toxicities of cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:212-216.

- Ozkan A, Apak H, Celkan T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after the use of high-dose cytosine arabinoside. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:38-40.

- Rizos E, Milionis HJ, Pavlidis N, et al. Acquired ichthyosis: a paraneoplastic skin manifestation of Hodgkin’s disease. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:727.

- Otmani N, Alami R, Hessissen L, et al. Determinants of severe oral mucositis in pediatric cancer patients: a prospective study. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2011;21:210-216.

- Mateus C, Robert C. New drugs in oncology and skin toxicity [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:401-410.

- Manji A, Tomlinson D, Ethier MC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire for child self-report and importance of mucositis in children treated with chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1251-1258.

- Keefe DM. Mucositis management in patients with cancer. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;3:154-157.

- Raber-Durlacher JE, Elad S, Barasch A. Oral mucositis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:452-456.

- Utas S, Kulluk P. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:466-474.

- Ott H, Höger PH. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in pediatric cancer patients [in German]. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217(suppl 1):110-119.

- Ramphal R, Grant RM, Dzolganovski B, et al. Herpes simplex virus in febrile neutropenic children undergoing chemotherapy for cancer: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:700-704.

- Yaris N, Cakir M, Kalyoncu M, et al. Bleomycin induced hyperpigmentation with yolk sac tumor. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:505-506.

- Kleynberg RL, Sofi AA, Chaudhary RT. Hand-foot hyperpigmentation skin lesions associated with combination gemcitabine-carboplatin (GemCarbo) therapy. Am J Ther. 2011;18:261-263.

- Blaya M, Saba N. Chemotherapy-induced hyperpigmentation of the tongue. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e20.

- Anandajeya WV, Corrêa ZM, Augsburger JJ. Primary acquired melanosis with atypia treated with mitomycin C. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:285-288.

- Torres C, Wong L, Welsh O, et al. Skin manifestations associated with chemotherapy in children with hematologic malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;2:123-147.

- Mays SR, Cohen PR. Emerging dermatologic issues in the oncology patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:179-189.

- Kamil N, Kamil S, Ahmed SP, et al. Toxic effects of multiple anticancer drugs on skin. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:7-14.

- Alley E, Green R, Schuchter L. Cutaneous toxicities of cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:212-216.

- Ozkan A, Apak H, Celkan T, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after the use of high-dose cytosine arabinoside. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:38-40.

- Rizos E, Milionis HJ, Pavlidis N, et al. Acquired ichthyosis: a paraneoplastic skin manifestation of Hodgkin’s disease. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:727.

- Otmani N, Alami R, Hessissen L, et al. Determinants of severe oral mucositis in pediatric cancer patients: a prospective study. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2011;21:210-216.

- Mateus C, Robert C. New drugs in oncology and skin toxicity [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:401-410.

- Manji A, Tomlinson D, Ethier MC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Oral Mucositis Daily Questionnaire for child self-report and importance of mucositis in children treated with chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1251-1258.

- Keefe DM. Mucositis management in patients with cancer. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;3:154-157.

- Raber-Durlacher JE, Elad S, Barasch A. Oral mucositis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:452-456.

- Utas S, Kulluk P. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:466-474.

- Ott H, Höger PH. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in pediatric cancer patients [in German]. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217(suppl 1):110-119.

- Ramphal R, Grant RM, Dzolganovski B, et al. Herpes simplex virus in febrile neutropenic children undergoing chemotherapy for cancer: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:700-704.

- Yaris N, Cakir M, Kalyoncu M, et al. Bleomycin induced hyperpigmentation with yolk sac tumor. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:505-506.

- Kleynberg RL, Sofi AA, Chaudhary RT. Hand-foot hyperpigmentation skin lesions associated with combination gemcitabine-carboplatin (GemCarbo) therapy. Am J Ther. 2011;18:261-263.

- Blaya M, Saba N. Chemotherapy-induced hyperpigmentation of the tongue. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e20.

- Anandajeya WV, Corrêa ZM, Augsburger JJ. Primary acquired melanosis with atypia treated with mitomycin C. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:285-288.

- Torres C, Wong L, Welsh O, et al. Skin manifestations associated with chemotherapy in children with hematologic malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;2:123-147.

- Mays SR, Cohen PR. Emerging dermatologic issues in the oncology patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:179-189.

Practice Points

- Chemotherapeutic agents can cause a variety of cutaneous side effects.

- Pediatric oncology patients should be examined regularly for cutaneous side effects of chemotherapeutics.

FDA approves oral anticoagulant for NVAF, VTE

Credit: FDA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) for use in two patient populations.

The anticoagulant is now approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and to treat venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients who have already received parenteral anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days.

The drug has been approved with a Boxed Warning.

The warning states that edoxaban is less effective in NVAF patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 95 mL/min. Patients with creatinine clearance above this limit have an increased risk of stroke if they receive edoxaban (compared to the risk with warfarin), so these patients should not receive edoxaban.

The warning also states that premature discontinuation of edoxaban increases the risk of stroke. Furthermore, spinal or epidural hematomas may occur in patients on edoxaban who are receiving anesthesia injected around the spine or undergoing spinal puncture.

Edoxaban for VTE

In the Hokusai-VTE trial, researchers evaluated edoxaban in 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with pulmonary embolism. Patients received initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent, symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

Edoxaban in NVAF

In the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial, researchers compared edoxaban and warfarin for the prevention of stroke or systemic embolic events (SEE) in patients with NVAF.

The trial included 21,105 patients who were randomized to receive warfarin (n=7036), edoxaban at 60 mg (n=7035), or edoxaban at 30 mg (n=7034).

Edoxaban was at least non-inferior to warfarin with regard to efficacy. The annual incidence of stroke or SEE was 1.50% with warfarin, 1.18% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001 for non-inferiority), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Annualized rates for the secondary composite endpoint of stroke, SEE, and cardiovascular death were 4.43% with warfarin, 3.85% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.005), and 4.23% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.32).

In addition, edoxaban was associated with a significantly lower rate of major and fatal bleeding. The annual incidence of major bleeding was 3.43% with warfarin, 2.75% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Fatal bleeds occurred at an annual rate of 0.38% with warfarin, 0.21% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.006), and 0.13% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Edoxaban is under development by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. ![]()

Credit: FDA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) for use in two patient populations.

The anticoagulant is now approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and to treat venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients who have already received parenteral anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days.

The drug has been approved with a Boxed Warning.

The warning states that edoxaban is less effective in NVAF patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 95 mL/min. Patients with creatinine clearance above this limit have an increased risk of stroke if they receive edoxaban (compared to the risk with warfarin), so these patients should not receive edoxaban.

The warning also states that premature discontinuation of edoxaban increases the risk of stroke. Furthermore, spinal or epidural hematomas may occur in patients on edoxaban who are receiving anesthesia injected around the spine or undergoing spinal puncture.

Edoxaban for VTE

In the Hokusai-VTE trial, researchers evaluated edoxaban in 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with pulmonary embolism. Patients received initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent, symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

Edoxaban in NVAF

In the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial, researchers compared edoxaban and warfarin for the prevention of stroke or systemic embolic events (SEE) in patients with NVAF.

The trial included 21,105 patients who were randomized to receive warfarin (n=7036), edoxaban at 60 mg (n=7035), or edoxaban at 30 mg (n=7034).

Edoxaban was at least non-inferior to warfarin with regard to efficacy. The annual incidence of stroke or SEE was 1.50% with warfarin, 1.18% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001 for non-inferiority), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Annualized rates for the secondary composite endpoint of stroke, SEE, and cardiovascular death were 4.43% with warfarin, 3.85% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.005), and 4.23% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.32).

In addition, edoxaban was associated with a significantly lower rate of major and fatal bleeding. The annual incidence of major bleeding was 3.43% with warfarin, 2.75% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Fatal bleeds occurred at an annual rate of 0.38% with warfarin, 0.21% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.006), and 0.13% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Edoxaban is under development by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. ![]()

Credit: FDA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) for use in two patient populations.

The anticoagulant is now approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and to treat venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients who have already received parenteral anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days.

The drug has been approved with a Boxed Warning.

The warning states that edoxaban is less effective in NVAF patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 95 mL/min. Patients with creatinine clearance above this limit have an increased risk of stroke if they receive edoxaban (compared to the risk with warfarin), so these patients should not receive edoxaban.

The warning also states that premature discontinuation of edoxaban increases the risk of stroke. Furthermore, spinal or epidural hematomas may occur in patients on edoxaban who are receiving anesthesia injected around the spine or undergoing spinal puncture.

Edoxaban for VTE

In the Hokusai-VTE trial, researchers evaluated edoxaban in 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with pulmonary embolism. Patients received initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent, symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

Edoxaban in NVAF

In the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial, researchers compared edoxaban and warfarin for the prevention of stroke or systemic embolic events (SEE) in patients with NVAF.

The trial included 21,105 patients who were randomized to receive warfarin (n=7036), edoxaban at 60 mg (n=7035), or edoxaban at 30 mg (n=7034).

Edoxaban was at least non-inferior to warfarin with regard to efficacy. The annual incidence of stroke or SEE was 1.50% with warfarin, 1.18% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001 for non-inferiority), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Annualized rates for the secondary composite endpoint of stroke, SEE, and cardiovascular death were 4.43% with warfarin, 3.85% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.005), and 4.23% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P=0.32).

In addition, edoxaban was associated with a significantly lower rate of major and fatal bleeding. The annual incidence of major bleeding was 3.43% with warfarin, 2.75% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P<0.001), and 1.61% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Fatal bleeds occurred at an annual rate of 0.38% with warfarin, 0.21% with edoxaban at 60 mg (P=0.006), and 0.13% with edoxaban at 30 mg (P<0.001).

Edoxaban is under development by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. ![]()

Product gets fast track designation for CTCL

mycosis fungoides

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to SGX301 as a first-line treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. The active ingredient in SGX301 is synthetic hypericin, a photosensitizer that is applied to skin lesions and then activated by fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients. Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

A phase 3 trial of SGX301 is set to begin in the first half of this year. In addition to its new fast track status, SGX301 also has orphan designation from the FDA.

About fast track designation

The FDA grants fast track designation to a drug that is intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition and that demonstrates the potential to address an unmet medical need for the condition.

Fast track designation is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of new drugs. For instance, Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is eligible to submit a new drug application (NDA) for SGX301 on a rolling basis, allowing the FDA to review sections of the NDA prior to receiving the complete submission.

Additionally, NDAs for fast track development programs ordinarily will be eligible for priority review, which imparts an abbreviated review time of approximately 6 months. ![]()

mycosis fungoides

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to SGX301 as a first-line treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. The active ingredient in SGX301 is synthetic hypericin, a photosensitizer that is applied to skin lesions and then activated by fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients. Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

A phase 3 trial of SGX301 is set to begin in the first half of this year. In addition to its new fast track status, SGX301 also has orphan designation from the FDA.

About fast track designation

The FDA grants fast track designation to a drug that is intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition and that demonstrates the potential to address an unmet medical need for the condition.

Fast track designation is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of new drugs. For instance, Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is eligible to submit a new drug application (NDA) for SGX301 on a rolling basis, allowing the FDA to review sections of the NDA prior to receiving the complete submission.

Additionally, NDAs for fast track development programs ordinarily will be eligible for priority review, which imparts an abbreviated review time of approximately 6 months. ![]()

mycosis fungoides

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to SGX301 as a first-line treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. The active ingredient in SGX301 is synthetic hypericin, a photosensitizer that is applied to skin lesions and then activated by fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients. Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

A phase 3 trial of SGX301 is set to begin in the first half of this year. In addition to its new fast track status, SGX301 also has orphan designation from the FDA.

About fast track designation

The FDA grants fast track designation to a drug that is intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition and that demonstrates the potential to address an unmet medical need for the condition.

Fast track designation is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of new drugs. For instance, Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is eligible to submit a new drug application (NDA) for SGX301 on a rolling basis, allowing the FDA to review sections of the NDA prior to receiving the complete submission.

Additionally, NDAs for fast track development programs ordinarily will be eligible for priority review, which imparts an abbreviated review time of approximately 6 months. ![]()

Drug granted orphan designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted selinexor (KPT-330) orphan drug designation to treat multiple myeloma (MM).

Selinexor already has orphan designation from the FDA to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The drug has also received orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to treat MM, AML, DLBCL, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, including Richter’s transformation.

“Orphan drug designation by the FDA for multiple myeloma is another significant milestone in the selinexor development program,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, President and Chief Scientific Officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing selinexor.

In the US, orphan designation qualifies a company for certain benefits, including an accelerated approval process, 7 years of market exclusivity following the drug’s approval, tax credits on US clinical trials, eligibility for orphan drug grants, and a waiver of certain administrative fees.

About selinexor

Selinexor (KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound. The drug functions by inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1).

This leads to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus, which subsequently reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function. This is thought to prompt apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor combos in MM

In a poster presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (4773), researchers reported results observed with selinexor plus dexamethasone in preclinical models and in patients with heavily pretreated, refractory MM.

The study included 9 evaluable patients who received selinexor at 45 mg/m2 twice weekly and dexamethasone at 20 mg twice weekly. The combination prompted an overall response rate of 67%, with one stringent complete response (11%) and 5 partial responses (56%), as well as a clinical benefit rate of 89%.

The combination demonstrated a reduction in nausea grades and very little weight loss compared with selinexor alone. The most common grade 1/2 adverse events were nausea, fatigue, anorexia, and vomiting.

The combination was also associated with an increase in time on study relative to selinexor alone. Sixty-six percent of patients remained on study for at least 16 weeks, including one patient for 28 weeks and one for 43 weeks as of December 1, 2014.

During the dose-evaluation part of the study, the 60 mg/m2 selinexor dose was deemed intolerable in this heavily pretreated patient population. So 45 mg/m2 is the recommended future study dose.

In another poster presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (3443), researchers described the activity of selinexor in combination with carfilzomib. This preclinical study revealed a novel, intracellular, membrane-embedded mechanism of caspase activation.

The results suggested a model of synergy wherein the selinexor-carfilzomib combination promotes caspase activation, likely by induced proximity, cleavage of other caspases, and subsequent apoptosis as well as autophagy. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted selinexor (KPT-330) orphan drug designation to treat multiple myeloma (MM).

Selinexor already has orphan designation from the FDA to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The drug has also received orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to treat MM, AML, DLBCL, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, including Richter’s transformation.

“Orphan drug designation by the FDA for multiple myeloma is another significant milestone in the selinexor development program,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, President and Chief Scientific Officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing selinexor.

In the US, orphan designation qualifies a company for certain benefits, including an accelerated approval process, 7 years of market exclusivity following the drug’s approval, tax credits on US clinical trials, eligibility for orphan drug grants, and a waiver of certain administrative fees.

About selinexor

Selinexor (KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound. The drug functions by inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1).

This leads to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus, which subsequently reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function. This is thought to prompt apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor combos in MM

In a poster presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (4773), researchers reported results observed with selinexor plus dexamethasone in preclinical models and in patients with heavily pretreated, refractory MM.

The study included 9 evaluable patients who received selinexor at 45 mg/m2 twice weekly and dexamethasone at 20 mg twice weekly. The combination prompted an overall response rate of 67%, with one stringent complete response (11%) and 5 partial responses (56%), as well as a clinical benefit rate of 89%.

The combination demonstrated a reduction in nausea grades and very little weight loss compared with selinexor alone. The most common grade 1/2 adverse events were nausea, fatigue, anorexia, and vomiting.

The combination was also associated with an increase in time on study relative to selinexor alone. Sixty-six percent of patients remained on study for at least 16 weeks, including one patient for 28 weeks and one for 43 weeks as of December 1, 2014.

During the dose-evaluation part of the study, the 60 mg/m2 selinexor dose was deemed intolerable in this heavily pretreated patient population. So 45 mg/m2 is the recommended future study dose.