User login

Utilization of the ICF-CY for the Classification of Therapeutic Objectives in the Treatment of Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy

From the IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy.

Abstract

- Objective: To identify objectives for treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A (BTX) in children with cerebral palsy (CP), standardize the objectives according to typology, and classify them according to the International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY), as well as to analyze treatment goals in relationship to CP clinical type, severity level, and age.

- Methods: 188 children were included in the study (mean age, 12 years; 42% female, 58% male). The diplegic type made up 38% of CP cases, the tetraplegic type 35%, and the hemiplegic type 24%. Children were mainly classified in the lowest and highest levels in the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS 1, 39%; GMFCS 5, 26%). Treatment objectives for individual therapies were discussed, identified, and transcribed in the therapeutic proposals. The objectives were then collected and subjected to an internal audit in order to standardize their denomination. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped the objectives to ICF-CY domains and categories. The objectives were then analyzed in relationship to CP clinical type, GMFCS level, and age.

- Results: Of the objectives, 88% (246) were in the “Body Functions” domain. In this domain, there were 28 typologies of objectives in 6 categories. Only 12% (32) of the objectives were in the “Activity” domain; there were 11 typologies in 5 categories. In diplegic and hemiplegic patients with mild disability (GMFCS 1), objectives were aimed at improving gait pattern. For quadriplegic patients with severe disability (GMFCS 5), objectives were aimed mainly at controlling deformities and improving health care provision. Objectives concerning pain treatment were proposed principally for patients with diplegic and quadriplegic type CP.

- Conclusions: The ICF-CY can be used to categorize treatment objectives proposed for patient improvement in the domains of Body Functions and Activity. Goal setting for BTX injections occurs mainly in the Body Functions domain and aims at finding changes in the gait pattern.

Botulinum toxin type A (BTX) has been used for 20 years for the focal treatment of spasticity in patients with cerebral palsy (CP) [1–3]. While numerous studies have shown the functional benefits of BTX treatment, especially if carried out in combination with other treatments (eg, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, serial casting), studies that focus on the indications for BTX use are limited.

Patients with CP require rehabilitation that involves multiple disciplines and multiprofessional therapeutic programs (eg, pharmacologic, orthotic, physiotherapeutic). The complexity of both the program and the pathology requires choosing the appropriate treatment objectives. The International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) [4] is a unified and standard language and framework for clinical, public health, and research applications to facilitate the documentation and measurement of health and disability in child and youth populations. As such, it can be used to inform clinical thinking, practice and research in the field of cerebral palsy [5], including being used as a tool for developing treatment plans and providing a common language for defining and sharing treatment objectives with patients and families [6]. Thamar et al [7] recently pointed out the value of adopting a standardized method of writing specific and measurable goals. Goals that are specific and clear are important not only for the evaluation of efficacy but also for systematic evaluation of the quality of health services [8,9].

In the literature regarding rehabilitation (especially in adults) and, more recently, in the literature on CP [10], core sets derived from ICF that are condition- and setting-specific are increasingly being used. They are used for the evaluation of the functional profiles of patients and documentation of the results of rehabilitative treatment, and also for defining the objectives of the treatment. Some authors [11–14] have explored in detail the possibility of using the core sets for formulating treatment objectives and assessing outcomes. However, using the core sets is complicated and their use in day-to-day clinical settings is limited. In a recent study, Preston et al [15] sought to define a sub-set of functional goals and outcomes relevant to patients with CP undergoing BTX treatment that could be more appropriate for use. In this retrospective analysis, they used the ICF-CY to classify treatment goals into corresponding domains and categories. The ICF-CY contains 4 major components (Body Structure, Body Function, Activities and Participation, and Environmental Factors), which each contain hierarchically arranged chapters and category levels. The authors found that the goals were mainly in the domain of “Body Functions,” specifically “functions of joint mobility” and “functions of gait pattern.” Those in the “Activity” domain were in the “walking” and “changing body positions” categories. This study was the first to focus on CP as a pathology and on the objectives of the individual therapeutic programs; other reports in the literature deal with the entire articulation of treatment. The authors limited themselves to the identification of the domain and the category of the objectives but did not report in detail their denomination. A greater degree of specificity and standardization in the description of the objectives would be useful from a practical point of view both for comparing results and for improving communication between the health care providers, and between these professionals and the families. The authors also did not assess for the various clinical types of CP.

The aim of the present study involving patients having CP and undergoing BTX injections was to identify the treatment objectives, standardize them according to denomination, classify them according to ICF-CY domains and categories, and establish their relative frequency. A further objective of the study was to analyze treatment goals in relationship to the clinical type (eg, hemiplegia, diplegia, quadriplegia), level of severity according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [16], and age.

Methods

Our center in Bologna, Italy, specializes in the evaluation and advanced treatment of spasticity in neuromotor disability in children and young adults. Between 2010 and the first half of 2012, 217 children were admitted to our center for evaluation and BTX treatment of spasticity in the upper or lower limbs or both. Of these, 188 children who had been diagnosed with spastic CP were included in the prospective study. Twenty-nine patients with other pathologies (epileptic and degenerative encephalopathy, spastic paraparesis) were excluded. The enrolled patients and their families were informed about the study and written informed consent was obtained.

Patients were evaluated from a functional point of view by 3 expert physiatrists and 2 pediatric physiotherapists for eligibility for BTX injection according to the recommendations of Ferrari and Cioni [17]. Functional assessment included evaluation of impairments (spasticity, contractures, deformities), main motor functions (gait pattern, manipulation pattern), and capacity of carrying out the principal motor activities (walking, maintaining and changing body position, rolling, use of upper limbs), thus enabling the identification of specific and realistic objectives for treatment with BTX. The objectives were chosen by a physiatrist and a physiotherapist, shared among the health care providers and the patients and their families, and added to the written treatment proposals. For each child more than 1 treatment objective could be proposed. These proposals were then collected and audited so as to obtain a uniform denomination of the proposed therapeutic objectives. In a series of meetings among all the members of the research group, the descriptions/denominations of the therapeutic goals were standardized and shared, eliminating inexact descriptions or adding new ones as needed. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped these to the ICF-CY domains and categories (up to the 2nd level of categorization). Each interpretative disagreement was resolved by group discussion. Finally, the objectives were analyzed in relationship to clinical type, severity according to GMFCS, and age. The frequency of the individual objectives, domains, and categories was evaluated by means of descriptive statistics.

Results

Body Functions Domain

The most represented category in the “Body Functions” domain was “b770 functions of gait pattern” (50%). There were 123 proposed objectives distributed among 11 typologies of objectives for a total of 123 proposed objectives in the functions of gait pattern category.

In the “b715 functions of joint stability” category, 25 objectives were proposed for controlling hip lateralization while, in the “b720 functions of bone mobility” category, 4 typologies of objectives were identified out of a total of 15 proposed objectives aimed at improving the position of the pelvis. The “b280 pain sensation” category was also used to indicate 15 objectives aiming at alleviating knee, hip and spinal column pain. Finally, 4 objectives were aimed at tone reduction.

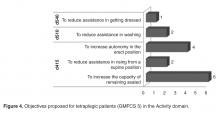

Activity Domain

As concerns the “Activity” domain, 38% of objectives were classified into the “d415 maintain body position” category (3 typologies and a total of 12 proposals), 25% were in the “d540 dress oneself ” category (2 typologies and a total of 8 proposals), 19% were in the “d440 fine use of the hands” category (3 typologies and a total of 6 proposals), 13% were in the “d445 use of hands and arms” category (2 typologies and 4 proposals) and, 6% of cases were classified into the “d510 wash oneself” category (2 proposals) (Table 2).

Analysis by Type, Severity, and Age

Discussion

The results show that in the majority of cases, the objectives of treatment with BTX injections proposed by our group fell within the “Body Functions” domain, in the “b770 gait pattern” and “b710 joint mobility” categories. This focus has also been reported by other authors [18]. Furthermore, these results are analogous to those reported by Preston [15]. The objectives classifiable into the “Activity” domain were more limited in our group. The most represented categories were “d415 maintain body position,” as also reported by Preston, and “d540 dressing oneself.” Preston et al reported many more objectives in the Activity domain, also utilizing the “walking” category. A possible reason is that objectives may reflect more the expectations of professionals and less those of patients. Indeed, when objectives suggested by patients and families are taken into greater consideration, goals proposed in the Activity area notably increase [19]. It is probably necessary to evaluate the objectives relevant to the professionals and those significant to the families and children separately.

The discrepancies between our data and Preston’s also most likely reflect differences in the study population. In our study, those undergoing injections aimed at improving gait pattern are, for the most part, hemiplegic and diplegic patients with mild disabilities (GMFCS 1). Their elevated degree of autonomy in mobility probably accounts for the scarcity of objectives for improving walking autonomy. In the most severe cases, such as quadriplegia, objectives are mainly aimed at controlling deformities and facilitating health care provision. Pain reduction is another important aspect and concerned quadriplegic and diplegic patients with severe disability. In contrast, objectives related to muscle tone reduction were limited, as the main objective was not a reduction but the control of muscle shortening and the subsequent deformities. However, this can become a primary objective in cases of spastic hyperactivation (eg, in adductor muscles) or in the case of dystonia, to improve patient comfort.

From a practical point of view, the use of this methodology provides for a common language that facilitates the communication and sharing of therapeutic objectives between different professionals (physiatrists and physiotherapists) and between health care providers and families and/or patients. This is important, as physiotherapy is often complementary to BTX injections and the objectives must be shared with the family. This methodology can help the clinician in the decision-making process and allows determining with greater specificity what is to be measured to document the achievement of the objectives.

Future research in this field will be aimed at evaluating patient outcomes by means of the adoption of suitable instruments (measurement scales) in order to quantify results which are consistent, according to the ICF-CY classification, with the domain and the category undergoing analysis.

Conclusion

As it has already been pointed out by various authors [10–15], the ICF-CY is a useful instrument for the classification of proposed therapeutic objectives into domains and categories, in order to standardize the language and to increase the sharing of the aims between the health care providers and between providers and families/patients. The most commonly followed approach calls for the use of functional profiles at the beginning of the care planning process, in order to establish the priorities and objectives of the interventions to be carried out. In order to streamline and facilitate procedures in clinical practice, many have proposed the use of core sets, but the validation procedure is complex and not always possible in all centers. Recently, Preston et al were the first to propose using the ICF-CY for classifying the objectives of an individual program. The procedure utilized is simple, easily reproducible, and allows identifying and classifying the objectives into categories using the ICF-CY. Furthermore, it is focused on an individual program and not on the entire articulation of programs, making interpretation of the data more linear. Our proposal is similar because it is focused on the analysis of an individual therapeutic program and because it utilizes the ICF classification system to classify the objectives; however, it achieves a higher degree of detail and standardization of the objectives.

In conclusion, the classification structure of the ICF-CY furnishes a useful and recognized instrument for categorizing the objectives of the interventions to be carried out. The classification of the objectives is specific for each pathology and for each individual program. The standardization of the objectives themselves and the use of the ICF-CY categories only for classification represents a possible methodologic alternative to the use of ICF-CY individual categories and sub-categories for identifying these objectives (core sets), as proposed by other authors. This procedure offers greater detail and a greater degree of standardization, which is important for the successive and systematic evaluation of treatment results.

Corresponding author: Nicoletta Battisti, Via Altura 3, 40139 Bologna, Italy, [email protected].

1. Lukban M, Rosales RL. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin A for upper and lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a summary of evidence. J Neural Transm 2009;116:319–31.

2. Ryll U, Bastianen C, De Bie R, Staal B. Effects of leg muscle botulinum toxin A injections on walking in children with spasticity related cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Devel Med Child Neurol 2011;53:210–6.

3. Hoare BJ, Wallen MA,Villanueva E, et al. Botulinum toxin A as an adjunct to treatment in the management of upper limb in children with spastic cerebral palsy. The Cochraine Library 2010.

4. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children and Youth Version for Children and Youth (ICF-CY). 2007. Available at http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?codlan=1&codcol=15&codcch=716#

5. Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. The World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health: a model to guide clinical thinking, practice, and research. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2004;11:5–10.

6. Steiner W, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther 2002;82:1098–107.

7. Thamar JH, Bovend’Eerdt, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: practical guide. Clin Rehab 2009;23:352–61.

8. Program outcome evaluations. United Way of Winnipeg; 2007.

9. Main K. Program design: a practical guide. Available at www.calgaryunitedway.org.

10. Schiariti V, Selb M, Cieza A, O’Donnel M. International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy: a consensus meeting 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014 Aug 6. Epub ahead of print

11. Huber EO, Tobler A, Gloor-Juzzi T, et al. The ICF as a way to specify goals and assess the outcome of physiotherapeutic interventions in the acute hospitals Rehabil Med 2011;43:174–7.

12. Mittrach R, Grill E, Walchner-Bonjean M, et al. Goals of physiotherapy interventions can be described using the International Classification Of Functioning, Disability and Health Physiotherapy 2008;94:150–7.

13. Muller MJ, Strobl R, Grill E. Goals of patients with rehabilitation needs in acute hospitals: goal achievement is an indicator for improved functioning Rehabil Med 2011;43:145–50.

14. Grill E J, Stucki G. Criteria for validating comprehensive ICF core sets and developing brief ICF core set versions. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:87–91.

15. Preston NJ, Clarke M, Bhakta B. Development of a framework to define the functional goals and outcomes of botulinum toxin A spasticity treatment relevant to the child and family living with cerebral palsy using the international classification of functioning disability and health for children and youth (ICF-CY). J Rehabil Med 2011;43:1010–5.

16. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, et al. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:214–23.

17. Ferrari A, Cioni G. The spastic forms of cerebral palsy: a guide to the assessment of adaptive functions. Springer-Verlag; 2010.

18. Franki I, De Cat J, Deschepper E, et al. A clinical decision framework for the identification of main problems and treatment goals for ambulant children with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil 2014;35:1160–76.

19. Lohmann S, Decker J, Müller M, et al. The ICF forms a useful framework for classifying individual patients goals in post-acute rehabilitation. Rehabil Med 2011;43:151–5.

From the IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy.

Abstract

- Objective: To identify objectives for treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A (BTX) in children with cerebral palsy (CP), standardize the objectives according to typology, and classify them according to the International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY), as well as to analyze treatment goals in relationship to CP clinical type, severity level, and age.

- Methods: 188 children were included in the study (mean age, 12 years; 42% female, 58% male). The diplegic type made up 38% of CP cases, the tetraplegic type 35%, and the hemiplegic type 24%. Children were mainly classified in the lowest and highest levels in the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS 1, 39%; GMFCS 5, 26%). Treatment objectives for individual therapies were discussed, identified, and transcribed in the therapeutic proposals. The objectives were then collected and subjected to an internal audit in order to standardize their denomination. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped the objectives to ICF-CY domains and categories. The objectives were then analyzed in relationship to CP clinical type, GMFCS level, and age.

- Results: Of the objectives, 88% (246) were in the “Body Functions” domain. In this domain, there were 28 typologies of objectives in 6 categories. Only 12% (32) of the objectives were in the “Activity” domain; there were 11 typologies in 5 categories. In diplegic and hemiplegic patients with mild disability (GMFCS 1), objectives were aimed at improving gait pattern. For quadriplegic patients with severe disability (GMFCS 5), objectives were aimed mainly at controlling deformities and improving health care provision. Objectives concerning pain treatment were proposed principally for patients with diplegic and quadriplegic type CP.

- Conclusions: The ICF-CY can be used to categorize treatment objectives proposed for patient improvement in the domains of Body Functions and Activity. Goal setting for BTX injections occurs mainly in the Body Functions domain and aims at finding changes in the gait pattern.

Botulinum toxin type A (BTX) has been used for 20 years for the focal treatment of spasticity in patients with cerebral palsy (CP) [1–3]. While numerous studies have shown the functional benefits of BTX treatment, especially if carried out in combination with other treatments (eg, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, serial casting), studies that focus on the indications for BTX use are limited.

Patients with CP require rehabilitation that involves multiple disciplines and multiprofessional therapeutic programs (eg, pharmacologic, orthotic, physiotherapeutic). The complexity of both the program and the pathology requires choosing the appropriate treatment objectives. The International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) [4] is a unified and standard language and framework for clinical, public health, and research applications to facilitate the documentation and measurement of health and disability in child and youth populations. As such, it can be used to inform clinical thinking, practice and research in the field of cerebral palsy [5], including being used as a tool for developing treatment plans and providing a common language for defining and sharing treatment objectives with patients and families [6]. Thamar et al [7] recently pointed out the value of adopting a standardized method of writing specific and measurable goals. Goals that are specific and clear are important not only for the evaluation of efficacy but also for systematic evaluation of the quality of health services [8,9].

In the literature regarding rehabilitation (especially in adults) and, more recently, in the literature on CP [10], core sets derived from ICF that are condition- and setting-specific are increasingly being used. They are used for the evaluation of the functional profiles of patients and documentation of the results of rehabilitative treatment, and also for defining the objectives of the treatment. Some authors [11–14] have explored in detail the possibility of using the core sets for formulating treatment objectives and assessing outcomes. However, using the core sets is complicated and their use in day-to-day clinical settings is limited. In a recent study, Preston et al [15] sought to define a sub-set of functional goals and outcomes relevant to patients with CP undergoing BTX treatment that could be more appropriate for use. In this retrospective analysis, they used the ICF-CY to classify treatment goals into corresponding domains and categories. The ICF-CY contains 4 major components (Body Structure, Body Function, Activities and Participation, and Environmental Factors), which each contain hierarchically arranged chapters and category levels. The authors found that the goals were mainly in the domain of “Body Functions,” specifically “functions of joint mobility” and “functions of gait pattern.” Those in the “Activity” domain were in the “walking” and “changing body positions” categories. This study was the first to focus on CP as a pathology and on the objectives of the individual therapeutic programs; other reports in the literature deal with the entire articulation of treatment. The authors limited themselves to the identification of the domain and the category of the objectives but did not report in detail their denomination. A greater degree of specificity and standardization in the description of the objectives would be useful from a practical point of view both for comparing results and for improving communication between the health care providers, and between these professionals and the families. The authors also did not assess for the various clinical types of CP.

The aim of the present study involving patients having CP and undergoing BTX injections was to identify the treatment objectives, standardize them according to denomination, classify them according to ICF-CY domains and categories, and establish their relative frequency. A further objective of the study was to analyze treatment goals in relationship to the clinical type (eg, hemiplegia, diplegia, quadriplegia), level of severity according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [16], and age.

Methods

Our center in Bologna, Italy, specializes in the evaluation and advanced treatment of spasticity in neuromotor disability in children and young adults. Between 2010 and the first half of 2012, 217 children were admitted to our center for evaluation and BTX treatment of spasticity in the upper or lower limbs or both. Of these, 188 children who had been diagnosed with spastic CP were included in the prospective study. Twenty-nine patients with other pathologies (epileptic and degenerative encephalopathy, spastic paraparesis) were excluded. The enrolled patients and their families were informed about the study and written informed consent was obtained.

Patients were evaluated from a functional point of view by 3 expert physiatrists and 2 pediatric physiotherapists for eligibility for BTX injection according to the recommendations of Ferrari and Cioni [17]. Functional assessment included evaluation of impairments (spasticity, contractures, deformities), main motor functions (gait pattern, manipulation pattern), and capacity of carrying out the principal motor activities (walking, maintaining and changing body position, rolling, use of upper limbs), thus enabling the identification of specific and realistic objectives for treatment with BTX. The objectives were chosen by a physiatrist and a physiotherapist, shared among the health care providers and the patients and their families, and added to the written treatment proposals. For each child more than 1 treatment objective could be proposed. These proposals were then collected and audited so as to obtain a uniform denomination of the proposed therapeutic objectives. In a series of meetings among all the members of the research group, the descriptions/denominations of the therapeutic goals were standardized and shared, eliminating inexact descriptions or adding new ones as needed. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped these to the ICF-CY domains and categories (up to the 2nd level of categorization). Each interpretative disagreement was resolved by group discussion. Finally, the objectives were analyzed in relationship to clinical type, severity according to GMFCS, and age. The frequency of the individual objectives, domains, and categories was evaluated by means of descriptive statistics.

Results

Body Functions Domain

The most represented category in the “Body Functions” domain was “b770 functions of gait pattern” (50%). There were 123 proposed objectives distributed among 11 typologies of objectives for a total of 123 proposed objectives in the functions of gait pattern category.

In the “b715 functions of joint stability” category, 25 objectives were proposed for controlling hip lateralization while, in the “b720 functions of bone mobility” category, 4 typologies of objectives were identified out of a total of 15 proposed objectives aimed at improving the position of the pelvis. The “b280 pain sensation” category was also used to indicate 15 objectives aiming at alleviating knee, hip and spinal column pain. Finally, 4 objectives were aimed at tone reduction.

Activity Domain

As concerns the “Activity” domain, 38% of objectives were classified into the “d415 maintain body position” category (3 typologies and a total of 12 proposals), 25% were in the “d540 dress oneself ” category (2 typologies and a total of 8 proposals), 19% were in the “d440 fine use of the hands” category (3 typologies and a total of 6 proposals), 13% were in the “d445 use of hands and arms” category (2 typologies and 4 proposals) and, 6% of cases were classified into the “d510 wash oneself” category (2 proposals) (Table 2).

Analysis by Type, Severity, and Age

Discussion

The results show that in the majority of cases, the objectives of treatment with BTX injections proposed by our group fell within the “Body Functions” domain, in the “b770 gait pattern” and “b710 joint mobility” categories. This focus has also been reported by other authors [18]. Furthermore, these results are analogous to those reported by Preston [15]. The objectives classifiable into the “Activity” domain were more limited in our group. The most represented categories were “d415 maintain body position,” as also reported by Preston, and “d540 dressing oneself.” Preston et al reported many more objectives in the Activity domain, also utilizing the “walking” category. A possible reason is that objectives may reflect more the expectations of professionals and less those of patients. Indeed, when objectives suggested by patients and families are taken into greater consideration, goals proposed in the Activity area notably increase [19]. It is probably necessary to evaluate the objectives relevant to the professionals and those significant to the families and children separately.

The discrepancies between our data and Preston’s also most likely reflect differences in the study population. In our study, those undergoing injections aimed at improving gait pattern are, for the most part, hemiplegic and diplegic patients with mild disabilities (GMFCS 1). Their elevated degree of autonomy in mobility probably accounts for the scarcity of objectives for improving walking autonomy. In the most severe cases, such as quadriplegia, objectives are mainly aimed at controlling deformities and facilitating health care provision. Pain reduction is another important aspect and concerned quadriplegic and diplegic patients with severe disability. In contrast, objectives related to muscle tone reduction were limited, as the main objective was not a reduction but the control of muscle shortening and the subsequent deformities. However, this can become a primary objective in cases of spastic hyperactivation (eg, in adductor muscles) or in the case of dystonia, to improve patient comfort.

From a practical point of view, the use of this methodology provides for a common language that facilitates the communication and sharing of therapeutic objectives between different professionals (physiatrists and physiotherapists) and between health care providers and families and/or patients. This is important, as physiotherapy is often complementary to BTX injections and the objectives must be shared with the family. This methodology can help the clinician in the decision-making process and allows determining with greater specificity what is to be measured to document the achievement of the objectives.

Future research in this field will be aimed at evaluating patient outcomes by means of the adoption of suitable instruments (measurement scales) in order to quantify results which are consistent, according to the ICF-CY classification, with the domain and the category undergoing analysis.

Conclusion

As it has already been pointed out by various authors [10–15], the ICF-CY is a useful instrument for the classification of proposed therapeutic objectives into domains and categories, in order to standardize the language and to increase the sharing of the aims between the health care providers and between providers and families/patients. The most commonly followed approach calls for the use of functional profiles at the beginning of the care planning process, in order to establish the priorities and objectives of the interventions to be carried out. In order to streamline and facilitate procedures in clinical practice, many have proposed the use of core sets, but the validation procedure is complex and not always possible in all centers. Recently, Preston et al were the first to propose using the ICF-CY for classifying the objectives of an individual program. The procedure utilized is simple, easily reproducible, and allows identifying and classifying the objectives into categories using the ICF-CY. Furthermore, it is focused on an individual program and not on the entire articulation of programs, making interpretation of the data more linear. Our proposal is similar because it is focused on the analysis of an individual therapeutic program and because it utilizes the ICF classification system to classify the objectives; however, it achieves a higher degree of detail and standardization of the objectives.

In conclusion, the classification structure of the ICF-CY furnishes a useful and recognized instrument for categorizing the objectives of the interventions to be carried out. The classification of the objectives is specific for each pathology and for each individual program. The standardization of the objectives themselves and the use of the ICF-CY categories only for classification represents a possible methodologic alternative to the use of ICF-CY individual categories and sub-categories for identifying these objectives (core sets), as proposed by other authors. This procedure offers greater detail and a greater degree of standardization, which is important for the successive and systematic evaluation of treatment results.

Corresponding author: Nicoletta Battisti, Via Altura 3, 40139 Bologna, Italy, [email protected].

From the IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy.

Abstract

- Objective: To identify objectives for treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A (BTX) in children with cerebral palsy (CP), standardize the objectives according to typology, and classify them according to the International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY), as well as to analyze treatment goals in relationship to CP clinical type, severity level, and age.

- Methods: 188 children were included in the study (mean age, 12 years; 42% female, 58% male). The diplegic type made up 38% of CP cases, the tetraplegic type 35%, and the hemiplegic type 24%. Children were mainly classified in the lowest and highest levels in the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS 1, 39%; GMFCS 5, 26%). Treatment objectives for individual therapies were discussed, identified, and transcribed in the therapeutic proposals. The objectives were then collected and subjected to an internal audit in order to standardize their denomination. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped the objectives to ICF-CY domains and categories. The objectives were then analyzed in relationship to CP clinical type, GMFCS level, and age.

- Results: Of the objectives, 88% (246) were in the “Body Functions” domain. In this domain, there were 28 typologies of objectives in 6 categories. Only 12% (32) of the objectives were in the “Activity” domain; there were 11 typologies in 5 categories. In diplegic and hemiplegic patients with mild disability (GMFCS 1), objectives were aimed at improving gait pattern. For quadriplegic patients with severe disability (GMFCS 5), objectives were aimed mainly at controlling deformities and improving health care provision. Objectives concerning pain treatment were proposed principally for patients with diplegic and quadriplegic type CP.

- Conclusions: The ICF-CY can be used to categorize treatment objectives proposed for patient improvement in the domains of Body Functions and Activity. Goal setting for BTX injections occurs mainly in the Body Functions domain and aims at finding changes in the gait pattern.

Botulinum toxin type A (BTX) has been used for 20 years for the focal treatment of spasticity in patients with cerebral palsy (CP) [1–3]. While numerous studies have shown the functional benefits of BTX treatment, especially if carried out in combination with other treatments (eg, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, serial casting), studies that focus on the indications for BTX use are limited.

Patients with CP require rehabilitation that involves multiple disciplines and multiprofessional therapeutic programs (eg, pharmacologic, orthotic, physiotherapeutic). The complexity of both the program and the pathology requires choosing the appropriate treatment objectives. The International Classification of Functioning for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) [4] is a unified and standard language and framework for clinical, public health, and research applications to facilitate the documentation and measurement of health and disability in child and youth populations. As such, it can be used to inform clinical thinking, practice and research in the field of cerebral palsy [5], including being used as a tool for developing treatment plans and providing a common language for defining and sharing treatment objectives with patients and families [6]. Thamar et al [7] recently pointed out the value of adopting a standardized method of writing specific and measurable goals. Goals that are specific and clear are important not only for the evaluation of efficacy but also for systematic evaluation of the quality of health services [8,9].

In the literature regarding rehabilitation (especially in adults) and, more recently, in the literature on CP [10], core sets derived from ICF that are condition- and setting-specific are increasingly being used. They are used for the evaluation of the functional profiles of patients and documentation of the results of rehabilitative treatment, and also for defining the objectives of the treatment. Some authors [11–14] have explored in detail the possibility of using the core sets for formulating treatment objectives and assessing outcomes. However, using the core sets is complicated and their use in day-to-day clinical settings is limited. In a recent study, Preston et al [15] sought to define a sub-set of functional goals and outcomes relevant to patients with CP undergoing BTX treatment that could be more appropriate for use. In this retrospective analysis, they used the ICF-CY to classify treatment goals into corresponding domains and categories. The ICF-CY contains 4 major components (Body Structure, Body Function, Activities and Participation, and Environmental Factors), which each contain hierarchically arranged chapters and category levels. The authors found that the goals were mainly in the domain of “Body Functions,” specifically “functions of joint mobility” and “functions of gait pattern.” Those in the “Activity” domain were in the “walking” and “changing body positions” categories. This study was the first to focus on CP as a pathology and on the objectives of the individual therapeutic programs; other reports in the literature deal with the entire articulation of treatment. The authors limited themselves to the identification of the domain and the category of the objectives but did not report in detail their denomination. A greater degree of specificity and standardization in the description of the objectives would be useful from a practical point of view both for comparing results and for improving communication between the health care providers, and between these professionals and the families. The authors also did not assess for the various clinical types of CP.

The aim of the present study involving patients having CP and undergoing BTX injections was to identify the treatment objectives, standardize them according to denomination, classify them according to ICF-CY domains and categories, and establish their relative frequency. A further objective of the study was to analyze treatment goals in relationship to the clinical type (eg, hemiplegia, diplegia, quadriplegia), level of severity according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [16], and age.

Methods

Our center in Bologna, Italy, specializes in the evaluation and advanced treatment of spasticity in neuromotor disability in children and young adults. Between 2010 and the first half of 2012, 217 children were admitted to our center for evaluation and BTX treatment of spasticity in the upper or lower limbs or both. Of these, 188 children who had been diagnosed with spastic CP were included in the prospective study. Twenty-nine patients with other pathologies (epileptic and degenerative encephalopathy, spastic paraparesis) were excluded. The enrolled patients and their families were informed about the study and written informed consent was obtained.

Patients were evaluated from a functional point of view by 3 expert physiatrists and 2 pediatric physiotherapists for eligibility for BTX injection according to the recommendations of Ferrari and Cioni [17]. Functional assessment included evaluation of impairments (spasticity, contractures, deformities), main motor functions (gait pattern, manipulation pattern), and capacity of carrying out the principal motor activities (walking, maintaining and changing body position, rolling, use of upper limbs), thus enabling the identification of specific and realistic objectives for treatment with BTX. The objectives were chosen by a physiatrist and a physiotherapist, shared among the health care providers and the patients and their families, and added to the written treatment proposals. For each child more than 1 treatment objective could be proposed. These proposals were then collected and audited so as to obtain a uniform denomination of the proposed therapeutic objectives. In a series of meetings among all the members of the research group, the descriptions/denominations of the therapeutic goals were standardized and shared, eliminating inexact descriptions or adding new ones as needed. Two trained health care providers expert in the use of the ICF-CY classification mapped these to the ICF-CY domains and categories (up to the 2nd level of categorization). Each interpretative disagreement was resolved by group discussion. Finally, the objectives were analyzed in relationship to clinical type, severity according to GMFCS, and age. The frequency of the individual objectives, domains, and categories was evaluated by means of descriptive statistics.

Results

Body Functions Domain

The most represented category in the “Body Functions” domain was “b770 functions of gait pattern” (50%). There were 123 proposed objectives distributed among 11 typologies of objectives for a total of 123 proposed objectives in the functions of gait pattern category.

In the “b715 functions of joint stability” category, 25 objectives were proposed for controlling hip lateralization while, in the “b720 functions of bone mobility” category, 4 typologies of objectives were identified out of a total of 15 proposed objectives aimed at improving the position of the pelvis. The “b280 pain sensation” category was also used to indicate 15 objectives aiming at alleviating knee, hip and spinal column pain. Finally, 4 objectives were aimed at tone reduction.

Activity Domain

As concerns the “Activity” domain, 38% of objectives were classified into the “d415 maintain body position” category (3 typologies and a total of 12 proposals), 25% were in the “d540 dress oneself ” category (2 typologies and a total of 8 proposals), 19% were in the “d440 fine use of the hands” category (3 typologies and a total of 6 proposals), 13% were in the “d445 use of hands and arms” category (2 typologies and 4 proposals) and, 6% of cases were classified into the “d510 wash oneself” category (2 proposals) (Table 2).

Analysis by Type, Severity, and Age

Discussion

The results show that in the majority of cases, the objectives of treatment with BTX injections proposed by our group fell within the “Body Functions” domain, in the “b770 gait pattern” and “b710 joint mobility” categories. This focus has also been reported by other authors [18]. Furthermore, these results are analogous to those reported by Preston [15]. The objectives classifiable into the “Activity” domain were more limited in our group. The most represented categories were “d415 maintain body position,” as also reported by Preston, and “d540 dressing oneself.” Preston et al reported many more objectives in the Activity domain, also utilizing the “walking” category. A possible reason is that objectives may reflect more the expectations of professionals and less those of patients. Indeed, when objectives suggested by patients and families are taken into greater consideration, goals proposed in the Activity area notably increase [19]. It is probably necessary to evaluate the objectives relevant to the professionals and those significant to the families and children separately.

The discrepancies between our data and Preston’s also most likely reflect differences in the study population. In our study, those undergoing injections aimed at improving gait pattern are, for the most part, hemiplegic and diplegic patients with mild disabilities (GMFCS 1). Their elevated degree of autonomy in mobility probably accounts for the scarcity of objectives for improving walking autonomy. In the most severe cases, such as quadriplegia, objectives are mainly aimed at controlling deformities and facilitating health care provision. Pain reduction is another important aspect and concerned quadriplegic and diplegic patients with severe disability. In contrast, objectives related to muscle tone reduction were limited, as the main objective was not a reduction but the control of muscle shortening and the subsequent deformities. However, this can become a primary objective in cases of spastic hyperactivation (eg, in adductor muscles) or in the case of dystonia, to improve patient comfort.

From a practical point of view, the use of this methodology provides for a common language that facilitates the communication and sharing of therapeutic objectives between different professionals (physiatrists and physiotherapists) and between health care providers and families and/or patients. This is important, as physiotherapy is often complementary to BTX injections and the objectives must be shared with the family. This methodology can help the clinician in the decision-making process and allows determining with greater specificity what is to be measured to document the achievement of the objectives.

Future research in this field will be aimed at evaluating patient outcomes by means of the adoption of suitable instruments (measurement scales) in order to quantify results which are consistent, according to the ICF-CY classification, with the domain and the category undergoing analysis.

Conclusion

As it has already been pointed out by various authors [10–15], the ICF-CY is a useful instrument for the classification of proposed therapeutic objectives into domains and categories, in order to standardize the language and to increase the sharing of the aims between the health care providers and between providers and families/patients. The most commonly followed approach calls for the use of functional profiles at the beginning of the care planning process, in order to establish the priorities and objectives of the interventions to be carried out. In order to streamline and facilitate procedures in clinical practice, many have proposed the use of core sets, but the validation procedure is complex and not always possible in all centers. Recently, Preston et al were the first to propose using the ICF-CY for classifying the objectives of an individual program. The procedure utilized is simple, easily reproducible, and allows identifying and classifying the objectives into categories using the ICF-CY. Furthermore, it is focused on an individual program and not on the entire articulation of programs, making interpretation of the data more linear. Our proposal is similar because it is focused on the analysis of an individual therapeutic program and because it utilizes the ICF classification system to classify the objectives; however, it achieves a higher degree of detail and standardization of the objectives.

In conclusion, the classification structure of the ICF-CY furnishes a useful and recognized instrument for categorizing the objectives of the interventions to be carried out. The classification of the objectives is specific for each pathology and for each individual program. The standardization of the objectives themselves and the use of the ICF-CY categories only for classification represents a possible methodologic alternative to the use of ICF-CY individual categories and sub-categories for identifying these objectives (core sets), as proposed by other authors. This procedure offers greater detail and a greater degree of standardization, which is important for the successive and systematic evaluation of treatment results.

Corresponding author: Nicoletta Battisti, Via Altura 3, 40139 Bologna, Italy, [email protected].

1. Lukban M, Rosales RL. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin A for upper and lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a summary of evidence. J Neural Transm 2009;116:319–31.

2. Ryll U, Bastianen C, De Bie R, Staal B. Effects of leg muscle botulinum toxin A injections on walking in children with spasticity related cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Devel Med Child Neurol 2011;53:210–6.

3. Hoare BJ, Wallen MA,Villanueva E, et al. Botulinum toxin A as an adjunct to treatment in the management of upper limb in children with spastic cerebral palsy. The Cochraine Library 2010.

4. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children and Youth Version for Children and Youth (ICF-CY). 2007. Available at http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?codlan=1&codcol=15&codcch=716#

5. Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. The World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health: a model to guide clinical thinking, practice, and research. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2004;11:5–10.

6. Steiner W, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther 2002;82:1098–107.

7. Thamar JH, Bovend’Eerdt, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: practical guide. Clin Rehab 2009;23:352–61.

8. Program outcome evaluations. United Way of Winnipeg; 2007.

9. Main K. Program design: a practical guide. Available at www.calgaryunitedway.org.

10. Schiariti V, Selb M, Cieza A, O’Donnel M. International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy: a consensus meeting 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014 Aug 6. Epub ahead of print

11. Huber EO, Tobler A, Gloor-Juzzi T, et al. The ICF as a way to specify goals and assess the outcome of physiotherapeutic interventions in the acute hospitals Rehabil Med 2011;43:174–7.

12. Mittrach R, Grill E, Walchner-Bonjean M, et al. Goals of physiotherapy interventions can be described using the International Classification Of Functioning, Disability and Health Physiotherapy 2008;94:150–7.

13. Muller MJ, Strobl R, Grill E. Goals of patients with rehabilitation needs in acute hospitals: goal achievement is an indicator for improved functioning Rehabil Med 2011;43:145–50.

14. Grill E J, Stucki G. Criteria for validating comprehensive ICF core sets and developing brief ICF core set versions. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:87–91.

15. Preston NJ, Clarke M, Bhakta B. Development of a framework to define the functional goals and outcomes of botulinum toxin A spasticity treatment relevant to the child and family living with cerebral palsy using the international classification of functioning disability and health for children and youth (ICF-CY). J Rehabil Med 2011;43:1010–5.

16. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, et al. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:214–23.

17. Ferrari A, Cioni G. The spastic forms of cerebral palsy: a guide to the assessment of adaptive functions. Springer-Verlag; 2010.

18. Franki I, De Cat J, Deschepper E, et al. A clinical decision framework for the identification of main problems and treatment goals for ambulant children with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil 2014;35:1160–76.

19. Lohmann S, Decker J, Müller M, et al. The ICF forms a useful framework for classifying individual patients goals in post-acute rehabilitation. Rehabil Med 2011;43:151–5.

1. Lukban M, Rosales RL. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin A for upper and lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a summary of evidence. J Neural Transm 2009;116:319–31.

2. Ryll U, Bastianen C, De Bie R, Staal B. Effects of leg muscle botulinum toxin A injections on walking in children with spasticity related cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Devel Med Child Neurol 2011;53:210–6.

3. Hoare BJ, Wallen MA,Villanueva E, et al. Botulinum toxin A as an adjunct to treatment in the management of upper limb in children with spastic cerebral palsy. The Cochraine Library 2010.

4. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children and Youth Version for Children and Youth (ICF-CY). 2007. Available at http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?codlan=1&codcol=15&codcch=716#

5. Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. The World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health: a model to guide clinical thinking, practice, and research. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2004;11:5–10.

6. Steiner W, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther 2002;82:1098–107.

7. Thamar JH, Bovend’Eerdt, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: practical guide. Clin Rehab 2009;23:352–61.

8. Program outcome evaluations. United Way of Winnipeg; 2007.

9. Main K. Program design: a practical guide. Available at www.calgaryunitedway.org.

10. Schiariti V, Selb M, Cieza A, O’Donnel M. International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy: a consensus meeting 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014 Aug 6. Epub ahead of print

11. Huber EO, Tobler A, Gloor-Juzzi T, et al. The ICF as a way to specify goals and assess the outcome of physiotherapeutic interventions in the acute hospitals Rehabil Med 2011;43:174–7.

12. Mittrach R, Grill E, Walchner-Bonjean M, et al. Goals of physiotherapy interventions can be described using the International Classification Of Functioning, Disability and Health Physiotherapy 2008;94:150–7.

13. Muller MJ, Strobl R, Grill E. Goals of patients with rehabilitation needs in acute hospitals: goal achievement is an indicator for improved functioning Rehabil Med 2011;43:145–50.

14. Grill E J, Stucki G. Criteria for validating comprehensive ICF core sets and developing brief ICF core set versions. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:87–91.

15. Preston NJ, Clarke M, Bhakta B. Development of a framework to define the functional goals and outcomes of botulinum toxin A spasticity treatment relevant to the child and family living with cerebral palsy using the international classification of functioning disability and health for children and youth (ICF-CY). J Rehabil Med 2011;43:1010–5.

16. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, et al. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:214–23.

17. Ferrari A, Cioni G. The spastic forms of cerebral palsy: a guide to the assessment of adaptive functions. Springer-Verlag; 2010.

18. Franki I, De Cat J, Deschepper E, et al. A clinical decision framework for the identification of main problems and treatment goals for ambulant children with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil 2014;35:1160–76.

19. Lohmann S, Decker J, Müller M, et al. The ICF forms a useful framework for classifying individual patients goals in post-acute rehabilitation. Rehabil Med 2011;43:151–5.

Reducing Hospital Readmissions for CHF Patients through Pre-Discharge Simulation-Based Learning

From North Mississippi Health Services, Tupelo, MS (Drs. Greer and Fagan), and the University of Colorado, Denver, CO (Dr. Coleman).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the self-care college, an innovative initiative designed to reduce hospital readmissions for congestive heart failure (CHF) patients.

- Methods: CHF patients at North Mississippi Medical Center are asked to participate in a “self-care college” prior to discharge. Participants rotate through 3 learning stations: weight, diet and medications. At each station, they are asked to perform the tasks they will be required to do at home. By engaging patients in the learning process, they are activated to assume responsibility for their care. This approach has the added advantage of providing a feedback loop, allowing the health care team to “road test” the proposed care plan to determine the likelihood that the patient (and family caregivers) will be able to execute following discharge.

- Results: Since the self-care college was implemented in 2011, the 30-day readmission rate for CHF patients at NMMC has been reduced from 16.8% to 12.85%. There has also been a reduction in the observed to expected CHF readmissions ratio, from 0.90 to 0.71.

- Conclusion: Although the self-care college targets CHF patients, it is likely that this type of initiative could be applied for rural patients with other chronic illnesses, such as asthma, COPD, and diabetes. It is a relatively simple and inexpensive program (approximately $30,000 per year, primarily in personnel expenses, or roughly the cost of 3 hospital readmissions) that does not require sophisticated technology or equipment, and could easily be replicated in health care settings across the country.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a chronic and costly condition that affects approximately 5.1 million people in the United States, with an additional 670,000 diagnosed yearly [1]. Heart failure is the most common cause of hospitalization among adults over 65. Nearly 25% of patients hospitalized with heart failure are readmitted within 30 days [2].

Medical management of people living with CHF and other chronic illnesses presents a challenge for health care providers. Due to their often complex medical conditions and limited opportunities to learn self-management skills, patients in rural areas with CHF are at increased risk for complications and hospital readmission [3]. Many approaches have been considered to reduce heart failure readmissions, including efforts to improve self-management skills. Initiatives that engage patients in the process of learning to self manage their illness may activate them to assume responsibility for their care.

North Mississippi Health Services (NMHS) is an integrated regional health care organization with over 5000 employees that serves more than 700,000 residents of 24 primarily rural counties in north Mississippi and northwest Alabama. The flagship of the NMHS system is North Mississippi Medical Center (NMMC), a 650-bed regional referral center in Tupelo. NMHS is one of the largest rural health systems in the United States, and the statistics for its service area reflect these challenges: the prevalence and age-adjusted mortality rates for most chronic illnesses exceed those for the nation as well as for Mississippi, which itself historically ranks at or near the bottom of almost all health status indicators [4–6]. On average, 800 patients with CHF are discharged annually from NMHS’s hospitals, and more than 2900 patients diagnosed with CHF are active NMMC clinic patients.

NHMS is addressing these challenges through a series of innovative quality improvement initiatives. NMHS’s newest initiative is the CHF self-care college. In this paper, we describe the initiative, its implementation, and evaluation to date.

Self-Care College

Background

The idea for the self-care college grew out of discussions with Nurse Link coaches, registered nurses employed by NMHS, who call CHF patients at their homes following discharge. The first call, within 48 hours following discharge, is to reconcile medications, conduct patient education, and confirm follow-up appointments. Three subsequent weekly calls focus on additional education and recognizing “red flags ” utilizing the IHI “teach back” method, in which patients are asked to restate instructions or concepts in their own words. During regular biweekly meetings with physicians to monitor patient progress, Nurse Link coaches observed that many patients (and in some cases, their caregivers) had difficulty following their discharge instructions. In particular, patients did not understand how to properly weigh themselves, how and when to take their medications, or how to ensure their diet met physicians’ guidelines. Although patients were being provided with written and oral instructions as part of the discharge process and through post-discharge follow-up communications, they did not properly implement those instructions once they returned home.

A multidisciplinary team consisting of NMHS physician leaders and representatives from pharmacy, dietary, physical therapy, cardiac rehabilitation, nursing, and case management met to brainstorm ways to overcome this challenge. What emerged from these discussions was the idea for a simulation-based learning experience for patients prior to discharge.

Simulation-based learning is not a new concept. It has been utilized for many years in aviation, health care, and the military as a way to train people in high-risk professions, using realistic scenarios in a controlled environment, without risk to participants. Participants receive immediate feedback from trained instructors as to whether they are performing critical functions properly, providing an opportunity to practice areas in which there is a need to improve technique, speed, or implementation of actions in the correct order. It has been proven to be a highly effective type of learning experience that results in better retention of skills, both cognitive and procedural, and it reduces preventable adverse events [7]. Simulation-based learning in medicine has traditionally been limited to clinician education, where providers practice on computerized patient simulators or other substitutes for live patients. To our knowledge, the concept of simulation learning has not been extended to patient education initiatives.

Simulation-based learning would actively engage patients in learning the necessary self-care skills rather than being passive recipients of information. As the self-care college team often says, “You don’t learn to ride a bike by reading a book; neither should you be asked how to manage CHF by reading a pamphlet.”

Learning Stations

Participants in the self-care college rotate sequentially through 3 learning stations: weight, diet and medications. The main location for the self-care college is a conference room on the cardiac unit of NMMC. At each station, patients are asked to perform the tasks they will be required to do at home. If they cannot complete the task, the deficit is recognized and addressed. This might include referring the patient to home health care, ensuring that a Nurse Link coach contacts him or his caregiver to reiterate medication instructions or ensuring that his case manager refers him to appropriate social services. Although no formal cognitive assessment is conducted, if the team perceives that the patient has a cognitive impairment that could prevent him from being able to perform self-care activities, this information is relayed to the case manager.

At the weight station, a physical therapist or cardiac rehabilitation professional stresses the importance of weighing daily and has the patient demonstrate weighing himself, providing feedback if necessary, to ensure that each patient knows how to properly weigh himself. If the patient does not own a scale, or needs an adaptive scale (such as one with extra large numbers or one that “talks”) and is financially unable to purchase one, he is given one to take home.

At the diet station, a registered dietitian asks the patient what he eats on a typical day, and he is given helpful dietary choices based on his responses. A display at this station provides sample food labels from some common foods, so that patients can see where and how to locate important nutrition information, such as sodium content. The dietitian also discusses fluid restriction and provides the patient and/or caregiver with a written copy of dietary recommendations. In the words of one self-care college patient, “I had to push that salt shaker away, but I also learned that salt comes in cans and boxes. I learned to read food labels for sodium content and to stay away from processed foods.”

At the medication station, a pharmacist reviews the patient’s heart failure medications, has the patient simulate how he will obtain, organize, and remember to take his medications at home, offers feedback and instruction, and answers questions. The pharmacist also provides the patient with a 7-day medication planner for home use and has the patient demonstrate completing the planner.

After the patient has been through the 3 learning stations, a Nurse Link coach enrolls him in the 4-week call-back program. In addition, home health care representatives are available to discuss the benefits of home health to help manage their CHF at home. Finally, each patient receives a CHF self-care college folder, with educational materials including a weight log/calendar; information on smoking cessation, medications, and prescription assistance; a personal health record; control zones for CHF management; red flags and warning signs/symptoms to report; and when to call the doctor.

When the patient has completed the self-care college, the self-care college team “huddles” to ensure that the patient is adequately prepared to transfer to their next health care destination. If not, recommendations are made to their provider to ensure a smooth transition. Family members and/or caregivers are encouraged to participate in the self-care college experience whenever possible and are included in the huddle.

Implementation

Prior to implementing the self-care college, the team identified 4 major challenges and developed strategies to address them. In many cases, strategies were effective in addressing more than one challenge.

- Coordinating the allocation of resources among different departments: as with any new initiative, finding time in everyone’s schedule to accommodate additional tasks is a challenge. In order to ensure that the self-care college was streamlined into everyone’s schedule, the team determined a set time of day that it would take place.

- Gaining buy-in from referring physicians: because referrals from physicians would be critical to the success of the self-care college, the team spent significant time meeting face-to-face with physicians to explain the reason for the program and how it would be implemented. In almost every case, physicians enthusiastically agreed to refer appropriate patients to the self-care college. Although NMHS operates in a fee-for-service environment (and physicians therefore are not financially incentivized to reduce readmissions), it has a strong culture of compassion and caring, focused on innovation, vision, and performance results. Physician buy-in was also facilitated by rolling out the program one floor at a time, so that the team and the physicians could become comfortable with the process. The nurses and case managers on each unit were educated about the program and could prompt the physician to consider placing a referral to the program if warranted.

- Logistical issues in getting the patients to the self-care college room: many CHF patients have significant mobility challenges, and the team discovered that it was not always possible for the patient to be transported to the room where the self-care college was set up, particularly as the program expanded into different wings of the medical center. As a result of feedback from patients and staff regarding the logistical issues around transporting patients to the college, the team developed a mobile version that is brought directly to the patient’s room. A cart holds scales, patient folders, medication planners, and all the tools necessary to present the program. Each member of the team rotates into the room to present their piece of the program. In addition to ensuring that patient mobility issues were not an obstacle to participation, developing the mobile program made the most efficient use of the team’s time in serving these patients, and no patient has been turned away due to having reached capacity at the stationary self-care college.

- Completing the self-care college in a timely fashion: In order to make most efficient use of time (for both the team and the patient), the content for each station was designed to last no more than 15 minutes on average. We have also worked with physicians to encourage referrals prior to the day of discharge, so that patients can be scheduled efficiently.

Program Evaluation

Because the self-care college is one of several initiatives being implemented by NMHS with a focus on reducing readmissions for CHF patients, it is difficult to identify the specific effect of the self-care college on readmissions. However, since implementation in 2011, we have seen a relative rate reduction in CHF readmissions of approximately 23%, and a reduction in the observed to expected CHF readmissions ratio from 0.90 to 0.70.

In addition, referrals have steadily increased since the program began, which suggests that physicians are confident in the program and its ability to improve outcomes.

Beyond the quantifiable measures available to us, comments from patients indicate that the self-care college is improving the quality of life for many of our patients. Two patients noted the following:

“I felt like I wasn’t just thrown out there by myself...I was scared because I didn’t know anything about this disease. The program let me know I wasn’t alone.”

“I eat much differently. I am learning to eat less and eat the right foods...I check my blood sugar every day now, and I weigh myself every day. I know if I weigh more than 244 pounds, I need to call someone.”

While patient and physician feedback has been very positive as far as the effectiveness in teaching patients important self-care skills, we discovered another benefit: not only does the self-care college give patients hands-on practice with skills they will need and the opportunity to ask questions, the team has an opportunity to observe patients actually performing self-care activities, ask the patient questions about how they will follow their discharge instructions, and evaluate whether they are ready to be discharged. Given the distances that many of these patients travel to receive care in the hospital, having insight into their capability prior to discharge is an important advantage.

For example, a patient completing the weight module was having difficulty reading the numbers on the scales due to poor visual acuity, which had not been otherwise noted in his hospital records. The team was able to fit him for a scale with large numbers. In other cases, we have found patients who are unable to identify low-sodium foods. To help them meet dietary guidelines, the dietitian uses a food prop to show them how to read and understand the Nutrition Facts label and then discusses alternative food choices with them. At the medication station, patients bring in all the medications they are currently taking and are asked to identify when, how, and why they take each medication. Frequently, we find that patients do not understand the instructions on the label or that they have duplicate medications because one is a generic and another is a brand name. We can provide the patient with a medication planner that helps ensure their medications are taken properly.

Lessons Learned

As with any new initiative, the self-care college team learned important lessons throughout the implementation process. Chief among these was that flexibility is critical to success. We listened to feedback from patients, physicians, and hospital staff and modified the program to ensure that it was integrated as seamlessly as possible into everyone’s schedule. Feedback was obtained through a variety of methods, including medical staff meetings, discussions with patients and their family members, and feedback from Nurse Link coaches. Feedback led to a number of changes, including development of the mobile self-care college and changing the timing from the day of discharge to the day prior to avoid conflicts with other day-of-discharge activities.

An additional lesson learned, which was actually a process of learning, was how important it is for self-care college team members to be active listeners. As opposed to the didactic approach, where clinicians provide instructions to patients, the self-care college team learned to ask questions of the patients and to actively listen to the responses, filling in the gaps where necessary. Interestingly, we found that this was also a learning process for the patients, many of whom are unaccustomed to engaging in dialogue with their doctors and to being active participants in their health care. They were not all initially comfortable with the concept of simulation, but our staff learned different ways to introduce patients to it, so that ultimately most seemed to enjoy the program.

Take-Away Points

For health care organizations considering implementing a self-care college or similar initiative, we offer a few key points:

- Consider the benefits beyond reducing readmissions: at NMHS, we have found that the self-care college has positively impacted patient satisfaction. For the past 2 years, our HCAHPS scores have consistently been well above the top performance threshold, a top quartile performer in Premier’s quality database (Premier, Inc., a health care performance improvement alliance of approximately 3000 U.S. hospitals). While it is difficult to correlate patient satisfaction scores with any one initiative, we hear from patients, physicians, and nursing staff that the self-care college greatly increases effective communication between provider and patient. We have also found that some of our biggest advocates are now the cardiologists who refer patients.

- Analyze your operational readiness: this is a low-tech but high-touch program. While it requires a minimal financial investment, it does require strong organizational leadership and staff buy-in to make it successful. Nursing staff are likely to buy into the program because they will not have to deliver discharge education to patients in addition to the many other responsibilities they have. Administrators should see that patient satisfaction will improve and readmissions will decrease. Ultimately, it is up to the program “champion” to make it clear to key stakeholders what the advantages are, and to include them in the process of developing the self-care college.

- This is the future of medicine: The self-care college is just one example of a team-based approach to medicine. Most of the disciplines on our team did not know each other prior to the program. We now have established a line of communication that permeates throughout the hospital to the outpatient setting.

Based on our success with the CHF self-care college, the next logical step will be to create self-care colleges for other common disease states, such as asthma/COPD or diabetes. However, while the value of this model for patient education has clearly been demonstrated, the team has also contemplated its application for staff training. Many large hospitals already use patient simulation manikins in nursing education, but the cost of this high-tech equipment is out of reach for many smaller, community hospitals. The possibility to create low-cost, low-tech simulation training experiences for clinicians similar to that provided by self-care college for patients bears examination.

Corresponding author: Lee Greer, MD, MBA, 830 S. Gloster St., Tupelo, MS 38801, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–239.

2. Hospital compare (Internet). Baltimore: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2014. Available at www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare.

3. Health disparities—a rural-urban chartbook. Columbia, SC: South Carolina Rural Health Research Center; 2008.

4. America’s health rankings [Internet]. Minnetonka: United Health Foundation; 2014. Available at www.americashealthrankings.org/MS.

5. County health profiles 2007 [Internet]. Jackson: Mississippi State Department of Health; 2009. Available at msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/31,0,299,463.html.

6. County Health rankings and roadmaps [Internet]. Madison: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2014. Available at www.countyhealthrankings.org.

7. Aebersold M, Tschannen D. Simulation in nursing practice: the impact on patient care. OJIN: Online J Iss Nurs 2013; 18(2):Manuscript 6.

From North Mississippi Health Services, Tupelo, MS (Drs. Greer and Fagan), and the University of Colorado, Denver, CO (Dr. Coleman).

Abstract