User login

Making K-Ras cancers druggable

Credit: PNAS

New findings suggest drugs can effectively fight K-Ras-mutant cancers—if they have a little help.

Experiments in human cancer cells showed that K-Ras-mutant tumor growth was highly dependent on the cells’ constant need to check and mend their DNA.

However, inhibiting the activity of H-Ras and N-Ras prevented the DNA damage response. And this made the cells more vulnerable to treatment.

“Our finding suggests that K-Ras cancers can be made more susceptible to existing therapies by interfering with their DNA repair mechanisms,” said Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, of the New York University School of Medicine.

“What some researchers have described as therapeutic ‘mission impossible’ may now become a ‘mission doable.’”

Dr Bar-Sagi and her colleagues reported this discovery in Cancer Cell.

The group’s research began with experiments to determine how Ras signaling leads to the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells. The team found that downregulation of wild-type H-Ras and N-Ras in mutant K-Ras cells caused the buildup of damaged DNA and slowed cell growth.

In the absence of H-Ras and N-Ras, K-Ras-mutant cancer cells failed to repair their DNA at the G2 phase of cell division. And this defect was caused by failure to properly activate Chk1.

With this in mind, the researchers decided to test the effects of H-Ras or N-Ras knockdown on treatment with DNA-damaging agents.

Knockdown of H-Ras or N-Ras sensitized K-Ras-mutant cancer cells to SN38 and oxaliplatin in vitro. But the same effect did not occur when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in K-Ras-wild-type cancer cells.

K-Ras-mutant cancer cells were also sensitive to treatment with the Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor AZD7726 when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in vitro.

To further support these findings, the researchers conducted experiments in mice with K-Ras-mutant tumors. Mice with H-Ras knockdown experienced tumor growth similar to controls.

But when the mice with H-Ras-suppressed tumors received the chemotherapy drug irinotecan, they experienced tumor regression that lasted up to 18 days post-treatment. On the other hand, mice without H-Ras suppression experienced modest tumor growth after treatment with irinotecan.

“Discovering more about how these different forms of Ras act on one another—including how they control DNA damage repair at Chk1 in combination with chemotherapy—could help us design drugs that greatly stall disease progression,” said study author Elda Grabocka, PhD, also of the New York University School of Medicine.

The researchers are now planning additional experiments on the biological interdependency of Ras proteins and what other chemotherapies might be involved in slowing cancer growth. Their goal is to map the Ras signaling pathways and identify as many therapeutic targets as possible. ![]()

Credit: PNAS

New findings suggest drugs can effectively fight K-Ras-mutant cancers—if they have a little help.

Experiments in human cancer cells showed that K-Ras-mutant tumor growth was highly dependent on the cells’ constant need to check and mend their DNA.

However, inhibiting the activity of H-Ras and N-Ras prevented the DNA damage response. And this made the cells more vulnerable to treatment.

“Our finding suggests that K-Ras cancers can be made more susceptible to existing therapies by interfering with their DNA repair mechanisms,” said Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, of the New York University School of Medicine.

“What some researchers have described as therapeutic ‘mission impossible’ may now become a ‘mission doable.’”

Dr Bar-Sagi and her colleagues reported this discovery in Cancer Cell.

The group’s research began with experiments to determine how Ras signaling leads to the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells. The team found that downregulation of wild-type H-Ras and N-Ras in mutant K-Ras cells caused the buildup of damaged DNA and slowed cell growth.

In the absence of H-Ras and N-Ras, K-Ras-mutant cancer cells failed to repair their DNA at the G2 phase of cell division. And this defect was caused by failure to properly activate Chk1.

With this in mind, the researchers decided to test the effects of H-Ras or N-Ras knockdown on treatment with DNA-damaging agents.

Knockdown of H-Ras or N-Ras sensitized K-Ras-mutant cancer cells to SN38 and oxaliplatin in vitro. But the same effect did not occur when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in K-Ras-wild-type cancer cells.

K-Ras-mutant cancer cells were also sensitive to treatment with the Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor AZD7726 when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in vitro.

To further support these findings, the researchers conducted experiments in mice with K-Ras-mutant tumors. Mice with H-Ras knockdown experienced tumor growth similar to controls.

But when the mice with H-Ras-suppressed tumors received the chemotherapy drug irinotecan, they experienced tumor regression that lasted up to 18 days post-treatment. On the other hand, mice without H-Ras suppression experienced modest tumor growth after treatment with irinotecan.

“Discovering more about how these different forms of Ras act on one another—including how they control DNA damage repair at Chk1 in combination with chemotherapy—could help us design drugs that greatly stall disease progression,” said study author Elda Grabocka, PhD, also of the New York University School of Medicine.

The researchers are now planning additional experiments on the biological interdependency of Ras proteins and what other chemotherapies might be involved in slowing cancer growth. Their goal is to map the Ras signaling pathways and identify as many therapeutic targets as possible. ![]()

Credit: PNAS

New findings suggest drugs can effectively fight K-Ras-mutant cancers—if they have a little help.

Experiments in human cancer cells showed that K-Ras-mutant tumor growth was highly dependent on the cells’ constant need to check and mend their DNA.

However, inhibiting the activity of H-Ras and N-Ras prevented the DNA damage response. And this made the cells more vulnerable to treatment.

“Our finding suggests that K-Ras cancers can be made more susceptible to existing therapies by interfering with their DNA repair mechanisms,” said Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, of the New York University School of Medicine.

“What some researchers have described as therapeutic ‘mission impossible’ may now become a ‘mission doable.’”

Dr Bar-Sagi and her colleagues reported this discovery in Cancer Cell.

The group’s research began with experiments to determine how Ras signaling leads to the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells. The team found that downregulation of wild-type H-Ras and N-Ras in mutant K-Ras cells caused the buildup of damaged DNA and slowed cell growth.

In the absence of H-Ras and N-Ras, K-Ras-mutant cancer cells failed to repair their DNA at the G2 phase of cell division. And this defect was caused by failure to properly activate Chk1.

With this in mind, the researchers decided to test the effects of H-Ras or N-Ras knockdown on treatment with DNA-damaging agents.

Knockdown of H-Ras or N-Ras sensitized K-Ras-mutant cancer cells to SN38 and oxaliplatin in vitro. But the same effect did not occur when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in K-Ras-wild-type cancer cells.

K-Ras-mutant cancer cells were also sensitive to treatment with the Chk1/Chk2 inhibitor AZD7726 when H-Ras or N-Ras was knocked down in vitro.

To further support these findings, the researchers conducted experiments in mice with K-Ras-mutant tumors. Mice with H-Ras knockdown experienced tumor growth similar to controls.

But when the mice with H-Ras-suppressed tumors received the chemotherapy drug irinotecan, they experienced tumor regression that lasted up to 18 days post-treatment. On the other hand, mice without H-Ras suppression experienced modest tumor growth after treatment with irinotecan.

“Discovering more about how these different forms of Ras act on one another—including how they control DNA damage repair at Chk1 in combination with chemotherapy—could help us design drugs that greatly stall disease progression,” said study author Elda Grabocka, PhD, also of the New York University School of Medicine.

The researchers are now planning additional experiments on the biological interdependency of Ras proteins and what other chemotherapies might be involved in slowing cancer growth. Their goal is to map the Ras signaling pathways and identify as many therapeutic targets as possible. ![]()

Rare outbreak in cancer clinic tied to saline flush

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella species bloodstream infections was due to improper handling of intravenous saline, according to a report published in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology.

From September 2011 to May 2012, 15 immunocompromised patients treated at an outpatient oncology clinic in West Virginia developed infections with Tsukamurella, which are gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans.

All patients had received a cancer diagnosis and had an indwelling central line, although central line types varied.

A case-control study revealed that the only risk factor for developing Tsukamurella infection was the receipt of a saline flush in September or October 2011, when clinic staff were using a common-source bag of saline.

Investigations by the West Virginia Bureau of Public Health (WVBPH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uncovered several lapses in infection control procedures relating to the care of long-term intravenous catheters and preparation of chemotherapy for patients at the clinic.

However, these investigations also suggested that saline flush syringes were the likely source of infection.

So the WVBPH and the CDC recommended the clinic institute several changes to its infection prevention and control practices, including using pre-packaged, manufactured saline flushes.

After the clinic changed this practice, Tsukamurella bloodstream infections stopped occurring, further supporting the saline flush as the source of infection.

“This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines and medication preparation practices to minimize the risk of infection for patients with weakened immune systems,” said lead study author Isaac See, MD, of the CDC.

To that end, the CDC has developed a basic infection control plan tailored to outpatient oncology facilities.

The plan outlines policies and procedures needed to meet minimal requirements for patient safety, including the proper use and handling of injectable medications and correct procedures for assessing central lines. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella species bloodstream infections was due to improper handling of intravenous saline, according to a report published in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology.

From September 2011 to May 2012, 15 immunocompromised patients treated at an outpatient oncology clinic in West Virginia developed infections with Tsukamurella, which are gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans.

All patients had received a cancer diagnosis and had an indwelling central line, although central line types varied.

A case-control study revealed that the only risk factor for developing Tsukamurella infection was the receipt of a saline flush in September or October 2011, when clinic staff were using a common-source bag of saline.

Investigations by the West Virginia Bureau of Public Health (WVBPH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uncovered several lapses in infection control procedures relating to the care of long-term intravenous catheters and preparation of chemotherapy for patients at the clinic.

However, these investigations also suggested that saline flush syringes were the likely source of infection.

So the WVBPH and the CDC recommended the clinic institute several changes to its infection prevention and control practices, including using pre-packaged, manufactured saline flushes.

After the clinic changed this practice, Tsukamurella bloodstream infections stopped occurring, further supporting the saline flush as the source of infection.

“This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines and medication preparation practices to minimize the risk of infection for patients with weakened immune systems,” said lead study author Isaac See, MD, of the CDC.

To that end, the CDC has developed a basic infection control plan tailored to outpatient oncology facilities.

The plan outlines policies and procedures needed to meet minimal requirements for patient safety, including the proper use and handling of injectable medications and correct procedures for assessing central lines. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella species bloodstream infections was due to improper handling of intravenous saline, according to a report published in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology.

From September 2011 to May 2012, 15 immunocompromised patients treated at an outpatient oncology clinic in West Virginia developed infections with Tsukamurella, which are gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans.

All patients had received a cancer diagnosis and had an indwelling central line, although central line types varied.

A case-control study revealed that the only risk factor for developing Tsukamurella infection was the receipt of a saline flush in September or October 2011, when clinic staff were using a common-source bag of saline.

Investigations by the West Virginia Bureau of Public Health (WVBPH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uncovered several lapses in infection control procedures relating to the care of long-term intravenous catheters and preparation of chemotherapy for patients at the clinic.

However, these investigations also suggested that saline flush syringes were the likely source of infection.

So the WVBPH and the CDC recommended the clinic institute several changes to its infection prevention and control practices, including using pre-packaged, manufactured saline flushes.

After the clinic changed this practice, Tsukamurella bloodstream infections stopped occurring, further supporting the saline flush as the source of infection.

“This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines and medication preparation practices to minimize the risk of infection for patients with weakened immune systems,” said lead study author Isaac See, MD, of the CDC.

To that end, the CDC has developed a basic infection control plan tailored to outpatient oncology facilities.

The plan outlines policies and procedures needed to meet minimal requirements for patient safety, including the proper use and handling of injectable medications and correct procedures for assessing central lines. ![]()

Research clarifies role of Ikaros in B-ALL

Credit: Aaron Logan

Two papers published in Nature Immunology have shed new light on the role of Ikaros in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In one paper, researchers describe experiments in mice that show a defect in Ikaros function can disrupt lymphopoiesis and prevent the development of mature B cells.

The cells stay in an aberrant state, which closely resembles that of cells in human B-ALL.

The other paper provides insight into how pre-B cells transition from a proliferative phase to a differentiation phase.

Investigators found that this process, which is vulnerable to leukemic transformation, is dependent upon Ikaros.

Ikaros defect in mice mimics human B-ALL

In the first sudy, researchers showed that loss of Ikaros function in mice creates an environment that mimics human B-ALL.

“We already know several transcription factors that play a central role in B-cell differentiation,” said study author Meinrad Busslinger, PhD, of the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria.

“Pax5, for example, represents a critical factor which activates the B-cell-specific program in precursor cells and simultaneously suppresses alternative cell fates. For Ikaros, we did not know, until now, what this factor is doing during early B-cell development.”

To find out, he and his colleagues analyzed mice that lacked Ikaros from an early stage of B-cell development on. They found that Ikaros deficiency arrested B-cell development due to a defect in pre-BCR signaling.

The cells remained in an aberrant, pro-B-cell stage and were prevented from further differentiation. They also showed increased cell adhesion and reduced migration compared to normal cells.

The researchers noted that loss of Ikaros function has previously been associated with the development of B-ALL. As in mice with a mutated Ikaros gene, B cells from B-ALL patients are arrested at an early checkpoint of B-cell development.

Loss of Ikaros in pre-B cells

With the second study, investigators provided new insight into pre-B-cell differentiation. They described the cells’ transition from a stroma-adherent proliferative phase to a nonadherent differentiation phase.

The stroma-adherent pre-B cells were highly proliferative and had limited self-renewing potential. But when they transitioned to the nonadherent phase, they exited the cell cycle, lost their capacity for self-renewal, and acquired the expression of genes encoding molecules that support B-cell maturation.

And this transition was dependent upon Ikaros.

“Loss of function in the transcription factor Ikaros appears to create a differentiation block that drives the pre-B cells into an adhesive state, promotes self-renewal, and primes them for malignant potential,” said study author Richard Van Etten, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Irvine.

Furthermore, the survival and proliferation of the Ikaros-deficient pre-B cells appeared to be dependent on cooperation between signaling via integrins and signaling via receptors for growth factors.

The researchers said this discovery points to a new avenue for treating B-ALLs resulting from Ikaros mutations. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

Two papers published in Nature Immunology have shed new light on the role of Ikaros in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In one paper, researchers describe experiments in mice that show a defect in Ikaros function can disrupt lymphopoiesis and prevent the development of mature B cells.

The cells stay in an aberrant state, which closely resembles that of cells in human B-ALL.

The other paper provides insight into how pre-B cells transition from a proliferative phase to a differentiation phase.

Investigators found that this process, which is vulnerable to leukemic transformation, is dependent upon Ikaros.

Ikaros defect in mice mimics human B-ALL

In the first sudy, researchers showed that loss of Ikaros function in mice creates an environment that mimics human B-ALL.

“We already know several transcription factors that play a central role in B-cell differentiation,” said study author Meinrad Busslinger, PhD, of the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria.

“Pax5, for example, represents a critical factor which activates the B-cell-specific program in precursor cells and simultaneously suppresses alternative cell fates. For Ikaros, we did not know, until now, what this factor is doing during early B-cell development.”

To find out, he and his colleagues analyzed mice that lacked Ikaros from an early stage of B-cell development on. They found that Ikaros deficiency arrested B-cell development due to a defect in pre-BCR signaling.

The cells remained in an aberrant, pro-B-cell stage and were prevented from further differentiation. They also showed increased cell adhesion and reduced migration compared to normal cells.

The researchers noted that loss of Ikaros function has previously been associated with the development of B-ALL. As in mice with a mutated Ikaros gene, B cells from B-ALL patients are arrested at an early checkpoint of B-cell development.

Loss of Ikaros in pre-B cells

With the second study, investigators provided new insight into pre-B-cell differentiation. They described the cells’ transition from a stroma-adherent proliferative phase to a nonadherent differentiation phase.

The stroma-adherent pre-B cells were highly proliferative and had limited self-renewing potential. But when they transitioned to the nonadherent phase, they exited the cell cycle, lost their capacity for self-renewal, and acquired the expression of genes encoding molecules that support B-cell maturation.

And this transition was dependent upon Ikaros.

“Loss of function in the transcription factor Ikaros appears to create a differentiation block that drives the pre-B cells into an adhesive state, promotes self-renewal, and primes them for malignant potential,” said study author Richard Van Etten, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Irvine.

Furthermore, the survival and proliferation of the Ikaros-deficient pre-B cells appeared to be dependent on cooperation between signaling via integrins and signaling via receptors for growth factors.

The researchers said this discovery points to a new avenue for treating B-ALLs resulting from Ikaros mutations. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

Two papers published in Nature Immunology have shed new light on the role of Ikaros in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In one paper, researchers describe experiments in mice that show a defect in Ikaros function can disrupt lymphopoiesis and prevent the development of mature B cells.

The cells stay in an aberrant state, which closely resembles that of cells in human B-ALL.

The other paper provides insight into how pre-B cells transition from a proliferative phase to a differentiation phase.

Investigators found that this process, which is vulnerable to leukemic transformation, is dependent upon Ikaros.

Ikaros defect in mice mimics human B-ALL

In the first sudy, researchers showed that loss of Ikaros function in mice creates an environment that mimics human B-ALL.

“We already know several transcription factors that play a central role in B-cell differentiation,” said study author Meinrad Busslinger, PhD, of the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria.

“Pax5, for example, represents a critical factor which activates the B-cell-specific program in precursor cells and simultaneously suppresses alternative cell fates. For Ikaros, we did not know, until now, what this factor is doing during early B-cell development.”

To find out, he and his colleagues analyzed mice that lacked Ikaros from an early stage of B-cell development on. They found that Ikaros deficiency arrested B-cell development due to a defect in pre-BCR signaling.

The cells remained in an aberrant, pro-B-cell stage and were prevented from further differentiation. They also showed increased cell adhesion and reduced migration compared to normal cells.

The researchers noted that loss of Ikaros function has previously been associated with the development of B-ALL. As in mice with a mutated Ikaros gene, B cells from B-ALL patients are arrested at an early checkpoint of B-cell development.

Loss of Ikaros in pre-B cells

With the second study, investigators provided new insight into pre-B-cell differentiation. They described the cells’ transition from a stroma-adherent proliferative phase to a nonadherent differentiation phase.

The stroma-adherent pre-B cells were highly proliferative and had limited self-renewing potential. But when they transitioned to the nonadherent phase, they exited the cell cycle, lost their capacity for self-renewal, and acquired the expression of genes encoding molecules that support B-cell maturation.

And this transition was dependent upon Ikaros.

“Loss of function in the transcription factor Ikaros appears to create a differentiation block that drives the pre-B cells into an adhesive state, promotes self-renewal, and primes them for malignant potential,” said study author Richard Van Etten, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Irvine.

Furthermore, the survival and proliferation of the Ikaros-deficient pre-B cells appeared to be dependent on cooperation between signaling via integrins and signaling via receptors for growth factors.

The researchers said this discovery points to a new avenue for treating B-ALLs resulting from Ikaros mutations. ![]()

Hospital Observation Care

Observation hospitalization is a growing phenomenon in the United States healthcare system.[1] For Medicare beneficiaries, observation encounters increased 33.6% from 2004 to 2011, with inpatient encounters decreasing by 7.8% over the same period.[2]

Observation length of stay has also increased. Medicare states that observation care should typically last <24 hours, and in only rare and exceptional cases exceed 48 hours. We and others have showed that observation stays, on average, do not meet this definition.[1, 3] At our institution, historically less than half of observation encounters discharge in under 24 hours, and 1 in 6 stay longer than 48 hours.[3]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a rules change effective October 1, 2013, in response to concern about recent increases in the length of time that CMS beneficiaries spend as hospital outpatients receiving observation services.[4] These rules shifted observation determination from clinical criteria, such as InterQual,[5] to a time‐based rule that hinges on a 2‐midnight cut point. Patients staying <2 midnights, with few exceptions, are now observation, and those staying 2 midnights are inpatients. This is important, as patients hospitalized as observation are technically outpatients, not covered by Medicare Part A hospital insurance, and ineligible for skilled nursing facility benefits.[3, 6]

Although challenges with observation status in general are well described,[1, 3, 7] the potential impact of the 2‐midnight rule is not fully known. The purpose of our descriptive study was to examine how the new rules, retrospectively applied to recent encounters, would affect our hospital encounters, with a separate analysis of Medicare encounters and adult general medicine encounters. First, as CMS predicted a net shift from outpatient to inpatient stays[8] under the new rule, we attempted to determine whether this rule would actually reduce observation encounter frequency. Second, as CMS has cited persistently large improper payment rates in short‐stay hospital inpatient claims[4] and intends to audit <2‐midnight inpatient encounters under the assumption that many are misclassified observation stays,[4, 8, 9] we sought to determine if short‐stay inpatient and observation encounters were truly the same. Third, as insurance coverage will change based on the 2‐midnight cut point, we sought to determine whether 2 midnights separated distinct clinical populations within observation status, making the rule logical and fair. Finally, we sought to determine whether external factors, such as time of admission, day of week of admission, and transfer to our institution would impact how patients may be classified under the new rule.

METHODS

Study Population

Our methods have been described previously[3] with the exception of the updated dates of inclusion. Briefly, we analyzed all observation and inpatient encounters at University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics (UWHC) and the adjacent American Family Children's Hospital, a tertiary care referral academic medical center in Madison, Wisconsin,[10] with start date between January 1, 2012 and February 28, 2013. Six encounters with length of stay (LOS) >6 months were censored as they were not discharged by the time of data abstraction, and 3 encounters were removed due to erroneous encounter discharge dates. Patients with all insurance types were included in anticipation that commercial payors will follow Medicare rules changes. The University of Wisconsin (UW) Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Data Sources

Data were abstracted from the UW Health Sciences electronic medical record and ancillary data systems by the UWHC Business Planning and Analysis Department. Variables included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity), insurance type, and characteristics of hospitalization (admission service, day of week encounter began, acute/unscheduled presentation, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes, LOS, transfer from other hospital). We considered inpatient admission start time to be departure from the emergency department (ED) or arrival at our hospital if the encounter was a transfer from another facility. Observation start time also hinged on arrival at our hospital if the encounter was transferred from another facility, but for observation encounters arriving from the ED, the ED rooming time was used as the encounter start based on conservative interpretation of CMS rules for observation start time under the 2‐midnight rule.[11] Discharge time for all encounters was considered physical discharge from the ward. Observation status decisions were made by the admitting physician, with as‐needed guidance by case management staff and utilization review physicians using InterQual Criteria (McKesson Corp, San Francisco, CA),[5] a reference historically used by CMS auditors to determine status.

Evaluation of the 2‐Midnight Rule

All encounters were stratified based on a stay of <2 midnights or 2 midnights. Because general medicine patients comprise the bulk of observation patients,[3] the subset of encounters occurring on the hospital's 4 hospitalist medicine services, 3 general medicine resident services, and 1 adult nonobstetrics family medicine service, collectively termed adult general medicine, were also evaluated separately. Medicare encounters were also evaluated separately.

We first specifically compared <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 2‐midnight observation encounters during the study period to determine the net number of encounters that would lose inpatient status (<2‐midnight inpatient encounters) and that would gain inpatient status (2‐midnight observation encounters) under the new rules. Subtracting the absolute number of <2‐midnight inpatient encounters from the 2‐midnight observation encounters results in the net loss or gain of inpatient encounters, assuming LOS does not change. Second, we compared ICD‐9 codes between <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and observation encounters to determine if these 2 groups were clinically distinguishable. Third, we compared diagnosis codes between observation encounters lasting <2 midnights and 2 midnights to establish whether the 2‐midnight cut point defines distinct patient groups within observation. Finally, we evaluated all observation encounters to determine whether the time of admission, the day of admission (weekday vs weekend), or whether the encounter had been transferred from another facility impacted encounter categorization under the new rules.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used in this study, with data largely summarized as number and percent. When appropriate, mean and standard deviation were used to describe central tendency and dispersion.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Inpatient and Observation Encounters

Of the 36,193 total hospital encounters during the study period, 4769 (13.2%) were classified as observation encounters. Of 8510 adult general medicine encounters, 2443 (28.7%) were observation. Adult general medicine observation encounters accounted for 51.2% of all observation encounters for the hospital. A total of 9.0% of our observation encounters were transferred from another institution (Table 1).

| Inpatient, n=31,424 (86.8%) | Observation, n=4,769 (13.2%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 15,083 (48.0%) | 2,321 (48.7%) |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 49.2 (23.6) | 49.4 (25.4) |

| Has primary care provider | 27,378 (87.1%) | 4,152 (87.1%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 27,145 (86.4%) | 3,880 (81.4%) |

| Non‐Caucasian | 3,478 (11.1%) | 739 (15.5%) |

| Unknown | 801 (2.5%) | 150 (3.1%) |

| Characteristics of hospitalization | ||

| Day of admission | ||

| Weekend (SaturdaySunday) | 5,058 (16.1%) | 1,129 (23.7%) |

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 26,360 (83.9%) | 3,640 (76.3%) |

| Transfer from other institution | 6,191 (19.7%) | 427 (9.0%) |

| Acute/unscheduled | 21,150 (67.3%) | 4,479 (93.9%) |

| Service of admission | ||

| Adult general medicine | 6,067 (19.3%) | 2,443 (51.2%) |

| Adult surgery | 13,625 (43.4%) | 856 (17.9%) |

| Adult subspecialty nonsurgery | 7,432 (23.7%) | 802 (16.8%) |

| Pediatrics | 4,300 (13.7%) | 668 (14.0%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 11,719 (37.3%) | 1,846 (38.7%) |

| Medicaid | 3,642 (11.6%) | 658 (13.8%) |

| Commercial | 13,321 (42.4%) | 1,817 (38.1%) |

| Other | 1,665 (5.3%) | 184 (3.9%) |

| None | 1,077 (3.4%) | 264 (5.5%) |

A total of 1442 (4.0%) encounters changed status during the study period, with 606 (42.0%) having changed from inpatient to observation and considered observation, and 836 (58.0%) having changed from observation to inpatient and considered inpatient.

Impact of the 2‐Midnight Rule on Number of Observation and Inpatient Encounters

Among all encounters, the 2‐midnight rule would result in a net transition of 14.9% of inpatient encounters to observation. Considering only Medicare encounters, the net transition would be 7.4% inpatient encounters to observation. Within adult general medicine patients, the parallel changes would be 2.2% (all insurance types) and a gain of 2.4% (Medicare only) (Table 2).

| Inpatient, n=31,424 (86.8%) | Observation, n=4,769 (13.2%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| All encounters, n=36,193 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 6,723* (21.4%) | 3,454 (72.4%) |

| 2 Midnights | 24,701 (78.6%) | 1,315* (27.6%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 5,408 (14.9%) | |

| Medicare encounters, n=13,565 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 1,728* (14.7%) | 1,127 (61.1%) |

| 2 Midnights | 9,991 (85.3%) | 719* (38.9%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 1,009 (7.4%) | |

| All general medicine, n=8,510 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 1,114* (18.4%) | 1,512 (61.9%) |

| 2 Midnights | 4,953 (81.6%) | 931* (38.1%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 183 (2.2%) | |

| Medicare general medicine, n=4,571 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 472* (14.3%) | 690 (54.2%) |

| 2 Midnights | 2,827 (85.7%) | 582* (45.8%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 110 (2.4%) | |

Encounters including surgical procedures on the so‐called inpatient‐only list will remain inpatient regardless of LOS. As we could not identify such encounters, we tested removal of all surgical stays under the overly conservative assumption that all short stay surgical patients would remain inpatient. Of 21,712 nonsurgical encounters that remained, there were 4074 <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 1146 2‐midnight observation encounters, yielding a net transition of 2928 (13.5%) inpatient encounters to observation encounters. Medicare encounters accounted for 8240 of these 21,712 (38.0%) nonsurgical encounters, with 1105 <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 653 2‐midnight observation encounters, yielding a net reclassification of 452 (5.5%) Medicare nonsurgical inpatient encounters to observation encounters.

Length of Stay and Diagnoses After Application of the 2‐Midnight Rule to Inpatient and Observation Encounters

Only 1 of the top 5 ICD‐9 codes (code 427: cardiac dysrhythmias) was shared between the 2‐midnight inpatient encounters and any observation encounter group. When the same criteria were applied to adult general medicine encounters, none of the top 5 ICD‐9 codes were shared (Table 3).

| All Encounters, n=36,193 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=6,723 (21.4%) | Inpatient Stays 2 Midnights, n=24,701 (78.6%) | Observation Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=3,454 (72.4%) | Observation Stays 2 Midnights n=1,315 (27.6%) | |||||

| ||||||||

| Day of admission | ||||||||

| Weekend (Saturday Sunday) | 1,026 (15.3%) | 4,032 (16.3%) | 781 (22.6%) | 348 (26.5%) | ||||

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 5,697 (84.7%) | 20,669 (83.7%) | 2,673 (77.4%) | 967 (73.5%) | ||||

| Transfer from another institution | 986 (14.7%) | 5,205 (21.1%) | 297 (8.6%) | 130 (9.9%) | ||||

| Top diagnosis codes | ||||||||

| ICD‐9 #1 | 996: Complications peculiar to specific procedure | 200 (3.0%) | 996: Complications peculiar to specific procedure | 1,355 (5.5%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 531 (15.4%) | 780: General symptoms | 124 (9.4%) |

| ICD‐9 #2 | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 195 (2.9%) | 715: Osteoarthrosis and allied disorders | 917 (3.7%) | 780: General symptoms | 235 (6.8%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 80 (6.1%) |

| ICD‐9 #3 | 722: Intervertebral disk disorder | 182 (2.7%) | 038: Septicemia | 689 (2.8%) | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 103 (3.0%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 48 (3.7%) |

| ICD‐9 #4 | 540: Acute appendicitis | 179 (2.7%) | 296: Episodic mood disorder | 619 (2.5%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 89 (2.6%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 38 (2.9%) |

| ICD‐9 #5 | V58: Encounter for other and unspecified procedures | 176 (2.6%) | 998: Other complications of procedures not elsewhere classified | 516 (2.1%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 56 (1.6%) | 599: Other disorders of urethra/urinary tract | 35 (2.7%) |

| Adult General Medicine Encounters, n=8,510 | ||||||||

| Inpatient Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=1,114 (18.4%) | Inpatient Stays 2 Midnights, n=4,953 (81.6%) | Observation Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=1,512 (61.9%) | Observation Stays 2 Midnights, n=931 (38.1%) | |||||

| Day of admission | ||||||||

| Weekend (Saturday Sunday) | 253 (22.7%) | 1,189 (24.0%) | 318 (21.0%) | 261 (28.0%) | ||||

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 861 (77.3%) | 3,764 (76.0%) | 1,194 (79.0%) | 670 (72.0%) | ||||

| Transfer from another institution | 89 (8.0%) | 1,193 (24.1%) | 61 (4.0%) | 75 (8.1%) | ||||

| Top diagnosis codes | ||||||||

| ICD‐9 #1 | 415: Acute pulmonary heart disease | 57 (5.1%) | 038: Septicemia | 423 (8.5%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 315 (20.8%) | 780: General symptoms | 99 (10.6%) |

| ICD‐9 #2 | 276: Disorders of fluid/electrolyte, acid/base | 51 (4.6%) | 486: Pneumonia | 206 (4.2%) | 780: General symptoms | 138 (9.1%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 51 (5.5%) |

| ICD‐9 #3 | 682: Other cellulitis and abscess | 47 (4.2%) | 584: Acute kidney failure | 181 (3.7%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 47 (3.1%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 37 (4.0%) |

| ICD‐9 #4 | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 43 (3.9%) | 577: Diseases of the pancreas | 181 (3.7%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 35 (2.3%) | 599: Other disorders of urethra/urinary tract | 30 (3.2%) |

| ICD‐9 #5 | 250: Diabetes mellitus | 40 (3.6%) | 682: Other cellulitis and abscess | 175 (3.5%) | 305: Nondependent abuse of drugs | 32 (2.1%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 28 (3.0%) |

Including all observation encounters across LOS, 4 of the 5 top ICD‐9 codes were the same for stays <2 midnights and 2 midnights. The same was true for short‐ and long‐stay general medicine observation encounters (Table 3).

For all observation encounters, 26.5% (348/1315) of 2‐midnight encounters started on a weekend compared to 22.6% (781/3454) of <2‐midnight encounters. For adult medicine observation, 28.0% (261/931) of 2‐midnight encounters started on a weekend compared to 21.0% (318/1512) of <2‐midnight encounters (Table 3).

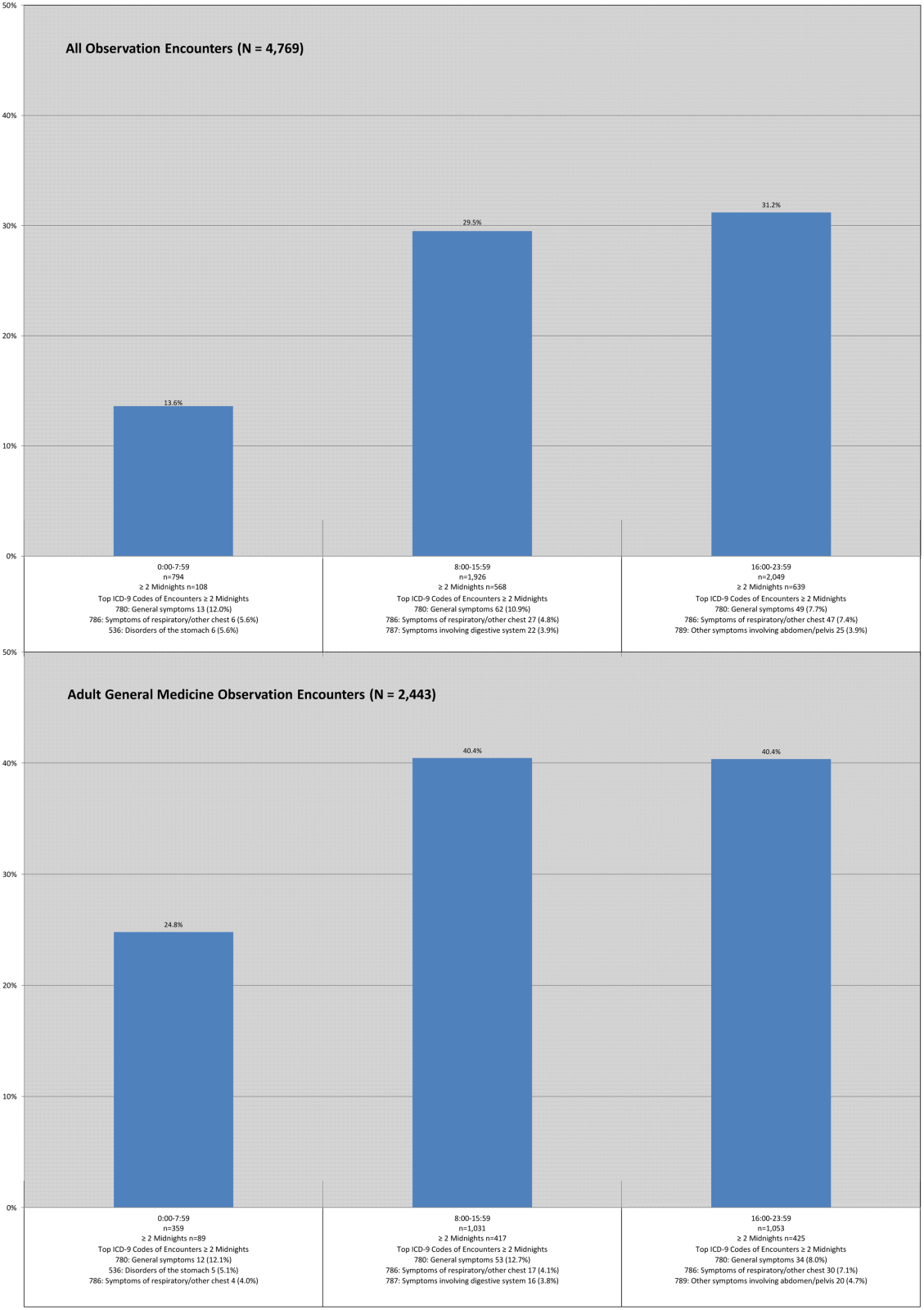

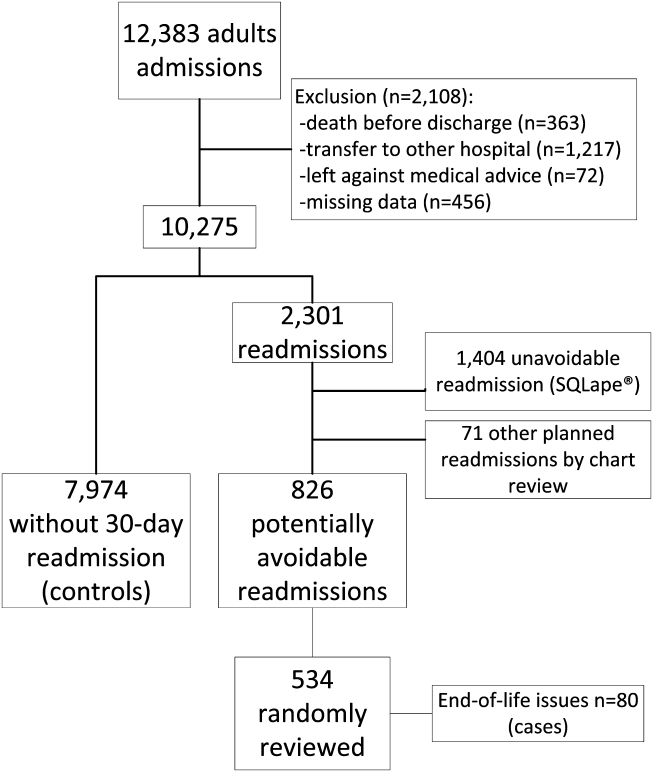

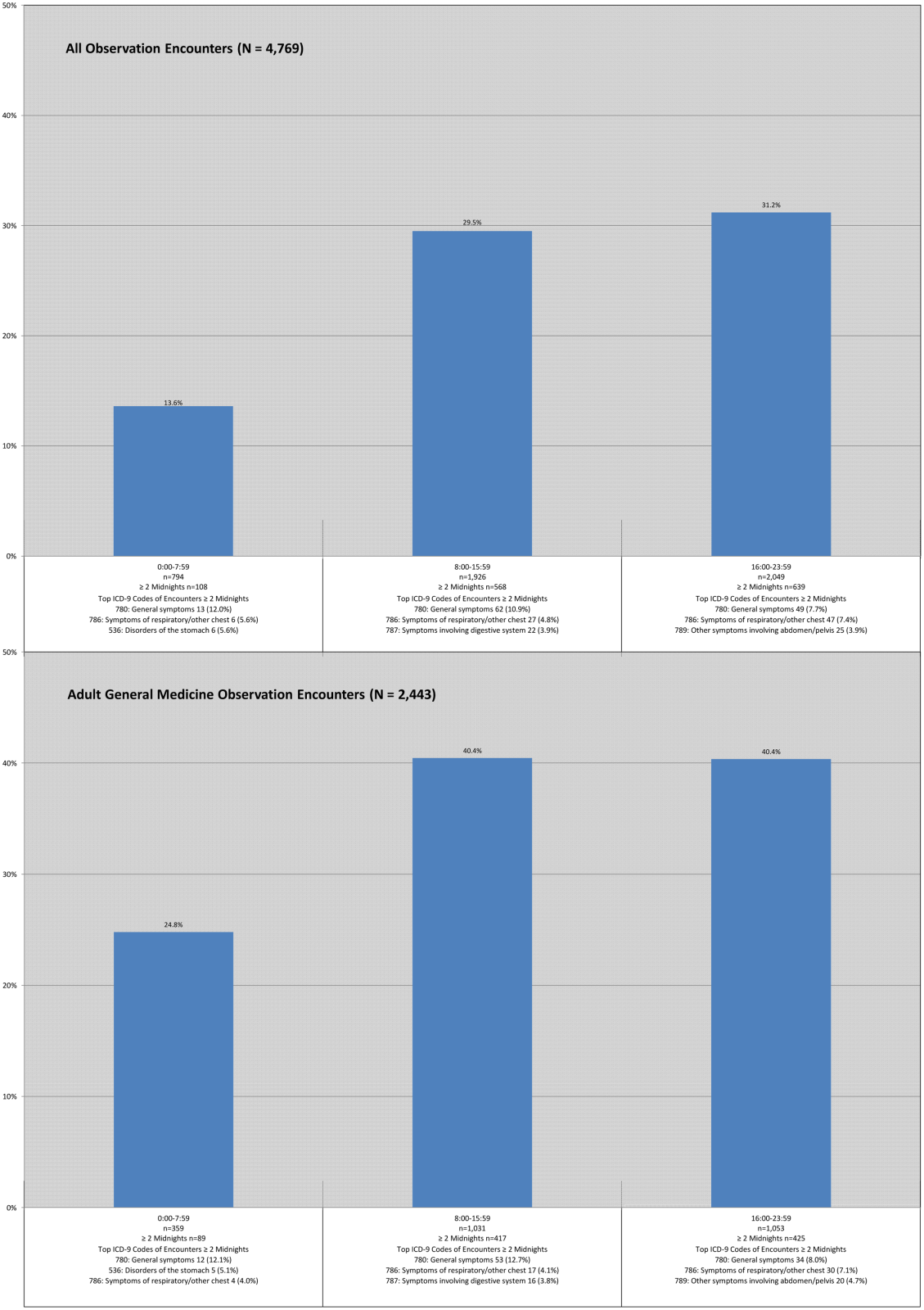

Percentage of Observation Encounters Reaching 2 Midnights Based on Time of Hospitalization

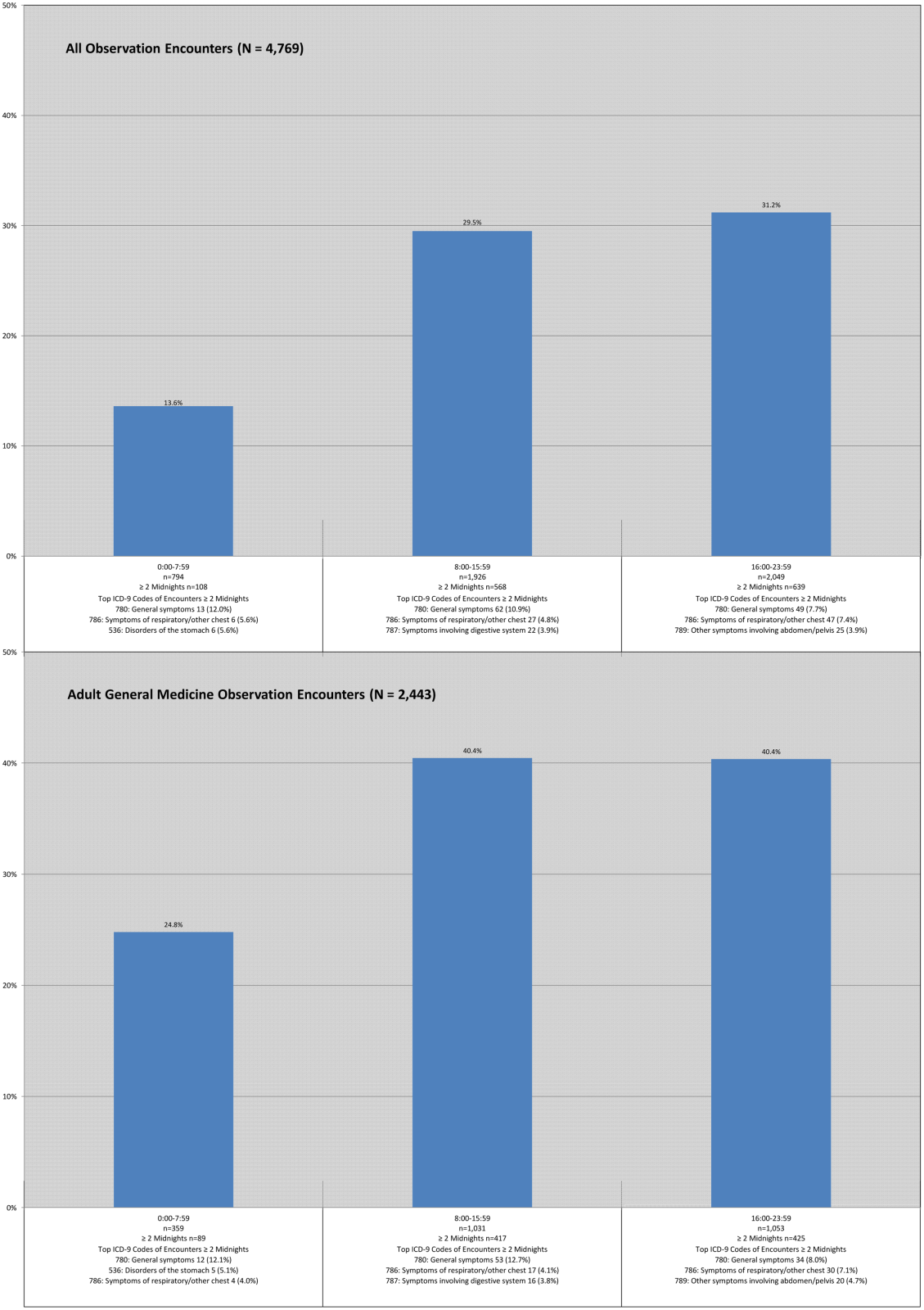

Observation encounters starting before 8:00 am spanned 2 midnights 13.6% of the time, and those encounters starting after 4:00 pm crossed 2 midnights 31.2% of the time. Two of the 3 top ICD‐9 codes were the same across LOS, with similar findings for the adult general medicine‐only group (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Although CMS predicts that more patients will be classified as inpatients under the new rule, we determined the opposite, consistent with a recent report generated by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for 2012 Medicare beneficiaries.[8] Our results did not change when we excluded all surgical encounters to account for possible exclusions based on the surgical inpatient‐only list. Although a small percentage of Medicare adult general medicine patients may be reclassified as inpatients under the new rules, the net effect would be that many more hospital encounters will be billed under observation rather than inpatient status. These findings assume overall length of stay will remain unchanged under these rules, an assumption that may not hold true given the financial losses we predicted hospitals may face under this rule,[12] and potential pressures on individual physicians providing patient care.

Medicare has prioritized auditing <2‐midnight inpatient encounters under the assumption that many short inpatient encounters are actually misclassified observation encounters,[4, 8, 9] prompting us to investigate whether this was the case in our patient population. Although it did not use ICD‐9 diagnosis codes, the OIG report suggested that short‐stay inpatients and observation patients may be clinically similar.[8, 13] Using ICD‐9 codes, we found no overlap between the top ICD‐9 codes for adult general medicine <2‐midnight inpatient and observation encounters, and only 1 of 5 shared codes for these encounters across all service lines. These findings are counter to the OIG report, and suggest that <2‐midnight inpatients are different from observation patients at our institution, and that <2‐midnight inpatients should not be arbitrarily reclassified as observation based solely upon LOS.

We also found that the majority of top ICD‐9 codes within observation were the same regardless of LOS, suggesting that LOS does not reliably differentiate clinically different observation populations that merit different insurance coverage (Medicare Part A for 2‐midnight encounters, Medicare Part B for <2‐midnight encounters). This lack of a clear cut point may drive an overall increase in LOS to achieve 2 midnights, as common diagnosis codes can be justified for both <2‐midnight or 2‐midnight observation stays.

Finally, we found that external factors, such as the time of day and specific day (weekday vs weekend) of hospitalization, impact the likelihood of achieving a 2‐midnight stay. Patients hospitalized earlier in the day were less likely to span 2 midnights compared to later‐day encounters, suggesting that use of a full working day as the day of presentation is harmful to a patient's chance of gaining inpatient status. Observation hospitalizations starting on a weekend day were more likely to achieve 2 midnights, which likely reflects different resource allocation and hospital efficiency on weekends, yet it is unlikely that weekend midnights, if associated with any delay in care, will be counted toward a patient's cumulative 2‐midnight total. The CMS has further indicated that midnights accrued prior to transfer from 1 hospital to another will not count toward a cumulative 2‐midnight stay. Although it would seem likely that patients requiring transfer to a tertiary care center would meet inpatient criteria, 9% of our observation encounters were transferred from other acute care hospitals, and many will have lost attributable midnights accrued prior to transfer to our hospital. Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that issues entirely unrelated to diagnosis or clinical status will impact whether hospitalized patients will be classified as inpatient or observation under the new rule.

This study has several limitations. Our data were limited to a single Midwestern tertiary care academic medical center, and may not be applicable to other healthcare settings. Second, 1.5% (466) of our inpatient stays and 56 (1.2%) of our observation encounters lacked a referral source in our administrative database, although these deficiencies would not likely change the conclusions. Finally, the total number of observation encounters starting before 8:00 am and staying 2 midnights was small and therefore potentially subject to confounding. However, despite the fact that encounters beginning in the early morning hours may be different in ways unable to be measured in this study, encounter ICD‐9 codes were similar regardless of time of day.

Despite these limitations, our study raises concerns about the impact of CMS's new time‐driven observation rules on hospital practice patterns. We found distinctly different <2‐midnight inpatient ICD‐9 codes as compared to those for observation encounters. Reclassifying <2‐midnight inpatients as observation may inappropriately shift the financial burden of acute hospitalizations to patients who were previously eligible to receive Medicare inpatient benefits. We also demonstrated a decrease in billable inpatient encounters under the new rules, which may be countered by changes in hospital and provider practice to drive more admissions over the 2‐midnight threshold to avoid financial losses. These changes should be defensible under audit given the ambiguities of the rule we found in this study surrounding time of day of admission, weekend and transfer hospitalizations, and the fact that common observation ICD‐9 codes are similar across LOS. Ironically, the unintended consequence of the new rule may be to drive up hospital LOS, reduce efficiency, and increase the overall cost of care.

Our findings suggest that CMS should define observation care per its original intent: as a means to determine if a patient can safely return home after a short period of additional care.[6] Patients whose conditions necessitate an intensity and level of service beyond this narrow scope should be classified as full inpatients irrespective of LOS, whether that LOS is <2 midnights or 2 midnights. Policies that fail to reflect the original intent of observation status are unlikely to achieve the intended outcome of defining 2 distinct patient populations that merit different services and reimbursement.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrew LaRocque and Dan Dexter for their assistance with the data. Without their help, this article would not have been possible.

Disclosures: Dr. Graf reports receiving royalties from Smith & Nephew for patents he has assigned to them involving orthopedic implants. This is unrelated to the topic or content of this manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Editor's Note: On February 24, 2014, after this manuscript was published, CMS issued a rules clarification allowing midnights spent at a referral hospital prior to transfer to be counted in the cumulative 2 midnight tally to determine inpatient status.

- , , . Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251–1259.

- MedPAC report to Congress: hospital inpatient and outpatient services. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/chapters/Mar13_Ch03.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2013.

- , , , et al. Hospitalized but not admitted: characteristics of patients with “Observation Status” at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(21):1991–1998.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services inpatient prospective payment system 1599‐F. Fiscal year 2014 final rule. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR‐2013‐08‐19/pdf/2013–18956.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2013.

- McKesson Interqual. Available at: http://www.mckesson.com/en_us/McKesson.com/Payers/Decision%2BManagement/InterQual%2BEvidence‐Based%2BClinical%2BContent/InterQual%2BEvidence‐Based%2BClinical%2BContent.html. Accessed October 3, 2013.

- Medicare benefit policy manual. Chapter 6. Hospital services covered under Part B. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R42BP.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2013.

- . Thinking of admitting this patient? Think again: how observation care is complicating life for you (and your patients). Today's Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read173(21):2004–2006.

- Kaiser Health News. HHS Inspector General scrutinizes Medicare observation care policy. Available at: http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2013/july/30/ig‐report‐observation‐care.aspx. Accessed October 3, 2013.

Observation hospitalization is a growing phenomenon in the United States healthcare system.[1] For Medicare beneficiaries, observation encounters increased 33.6% from 2004 to 2011, with inpatient encounters decreasing by 7.8% over the same period.[2]

Observation length of stay has also increased. Medicare states that observation care should typically last <24 hours, and in only rare and exceptional cases exceed 48 hours. We and others have showed that observation stays, on average, do not meet this definition.[1, 3] At our institution, historically less than half of observation encounters discharge in under 24 hours, and 1 in 6 stay longer than 48 hours.[3]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a rules change effective October 1, 2013, in response to concern about recent increases in the length of time that CMS beneficiaries spend as hospital outpatients receiving observation services.[4] These rules shifted observation determination from clinical criteria, such as InterQual,[5] to a time‐based rule that hinges on a 2‐midnight cut point. Patients staying <2 midnights, with few exceptions, are now observation, and those staying 2 midnights are inpatients. This is important, as patients hospitalized as observation are technically outpatients, not covered by Medicare Part A hospital insurance, and ineligible for skilled nursing facility benefits.[3, 6]

Although challenges with observation status in general are well described,[1, 3, 7] the potential impact of the 2‐midnight rule is not fully known. The purpose of our descriptive study was to examine how the new rules, retrospectively applied to recent encounters, would affect our hospital encounters, with a separate analysis of Medicare encounters and adult general medicine encounters. First, as CMS predicted a net shift from outpatient to inpatient stays[8] under the new rule, we attempted to determine whether this rule would actually reduce observation encounter frequency. Second, as CMS has cited persistently large improper payment rates in short‐stay hospital inpatient claims[4] and intends to audit <2‐midnight inpatient encounters under the assumption that many are misclassified observation stays,[4, 8, 9] we sought to determine if short‐stay inpatient and observation encounters were truly the same. Third, as insurance coverage will change based on the 2‐midnight cut point, we sought to determine whether 2 midnights separated distinct clinical populations within observation status, making the rule logical and fair. Finally, we sought to determine whether external factors, such as time of admission, day of week of admission, and transfer to our institution would impact how patients may be classified under the new rule.

METHODS

Study Population

Our methods have been described previously[3] with the exception of the updated dates of inclusion. Briefly, we analyzed all observation and inpatient encounters at University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics (UWHC) and the adjacent American Family Children's Hospital, a tertiary care referral academic medical center in Madison, Wisconsin,[10] with start date between January 1, 2012 and February 28, 2013. Six encounters with length of stay (LOS) >6 months were censored as they were not discharged by the time of data abstraction, and 3 encounters were removed due to erroneous encounter discharge dates. Patients with all insurance types were included in anticipation that commercial payors will follow Medicare rules changes. The University of Wisconsin (UW) Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Data Sources

Data were abstracted from the UW Health Sciences electronic medical record and ancillary data systems by the UWHC Business Planning and Analysis Department. Variables included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity), insurance type, and characteristics of hospitalization (admission service, day of week encounter began, acute/unscheduled presentation, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes, LOS, transfer from other hospital). We considered inpatient admission start time to be departure from the emergency department (ED) or arrival at our hospital if the encounter was a transfer from another facility. Observation start time also hinged on arrival at our hospital if the encounter was transferred from another facility, but for observation encounters arriving from the ED, the ED rooming time was used as the encounter start based on conservative interpretation of CMS rules for observation start time under the 2‐midnight rule.[11] Discharge time for all encounters was considered physical discharge from the ward. Observation status decisions were made by the admitting physician, with as‐needed guidance by case management staff and utilization review physicians using InterQual Criteria (McKesson Corp, San Francisco, CA),[5] a reference historically used by CMS auditors to determine status.

Evaluation of the 2‐Midnight Rule

All encounters were stratified based on a stay of <2 midnights or 2 midnights. Because general medicine patients comprise the bulk of observation patients,[3] the subset of encounters occurring on the hospital's 4 hospitalist medicine services, 3 general medicine resident services, and 1 adult nonobstetrics family medicine service, collectively termed adult general medicine, were also evaluated separately. Medicare encounters were also evaluated separately.

We first specifically compared <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 2‐midnight observation encounters during the study period to determine the net number of encounters that would lose inpatient status (<2‐midnight inpatient encounters) and that would gain inpatient status (2‐midnight observation encounters) under the new rules. Subtracting the absolute number of <2‐midnight inpatient encounters from the 2‐midnight observation encounters results in the net loss or gain of inpatient encounters, assuming LOS does not change. Second, we compared ICD‐9 codes between <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and observation encounters to determine if these 2 groups were clinically distinguishable. Third, we compared diagnosis codes between observation encounters lasting <2 midnights and 2 midnights to establish whether the 2‐midnight cut point defines distinct patient groups within observation. Finally, we evaluated all observation encounters to determine whether the time of admission, the day of admission (weekday vs weekend), or whether the encounter had been transferred from another facility impacted encounter categorization under the new rules.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used in this study, with data largely summarized as number and percent. When appropriate, mean and standard deviation were used to describe central tendency and dispersion.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Inpatient and Observation Encounters

Of the 36,193 total hospital encounters during the study period, 4769 (13.2%) were classified as observation encounters. Of 8510 adult general medicine encounters, 2443 (28.7%) were observation. Adult general medicine observation encounters accounted for 51.2% of all observation encounters for the hospital. A total of 9.0% of our observation encounters were transferred from another institution (Table 1).

| Inpatient, n=31,424 (86.8%) | Observation, n=4,769 (13.2%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 15,083 (48.0%) | 2,321 (48.7%) |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 49.2 (23.6) | 49.4 (25.4) |

| Has primary care provider | 27,378 (87.1%) | 4,152 (87.1%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 27,145 (86.4%) | 3,880 (81.4%) |

| Non‐Caucasian | 3,478 (11.1%) | 739 (15.5%) |

| Unknown | 801 (2.5%) | 150 (3.1%) |

| Characteristics of hospitalization | ||

| Day of admission | ||

| Weekend (SaturdaySunday) | 5,058 (16.1%) | 1,129 (23.7%) |

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 26,360 (83.9%) | 3,640 (76.3%) |

| Transfer from other institution | 6,191 (19.7%) | 427 (9.0%) |

| Acute/unscheduled | 21,150 (67.3%) | 4,479 (93.9%) |

| Service of admission | ||

| Adult general medicine | 6,067 (19.3%) | 2,443 (51.2%) |

| Adult surgery | 13,625 (43.4%) | 856 (17.9%) |

| Adult subspecialty nonsurgery | 7,432 (23.7%) | 802 (16.8%) |

| Pediatrics | 4,300 (13.7%) | 668 (14.0%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | 11,719 (37.3%) | 1,846 (38.7%) |

| Medicaid | 3,642 (11.6%) | 658 (13.8%) |

| Commercial | 13,321 (42.4%) | 1,817 (38.1%) |

| Other | 1,665 (5.3%) | 184 (3.9%) |

| None | 1,077 (3.4%) | 264 (5.5%) |

A total of 1442 (4.0%) encounters changed status during the study period, with 606 (42.0%) having changed from inpatient to observation and considered observation, and 836 (58.0%) having changed from observation to inpatient and considered inpatient.

Impact of the 2‐Midnight Rule on Number of Observation and Inpatient Encounters

Among all encounters, the 2‐midnight rule would result in a net transition of 14.9% of inpatient encounters to observation. Considering only Medicare encounters, the net transition would be 7.4% inpatient encounters to observation. Within adult general medicine patients, the parallel changes would be 2.2% (all insurance types) and a gain of 2.4% (Medicare only) (Table 2).

| Inpatient, n=31,424 (86.8%) | Observation, n=4,769 (13.2%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| All encounters, n=36,193 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 6,723* (21.4%) | 3,454 (72.4%) |

| 2 Midnights | 24,701 (78.6%) | 1,315* (27.6%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 5,408 (14.9%) | |

| Medicare encounters, n=13,565 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 1,728* (14.7%) | 1,127 (61.1%) |

| 2 Midnights | 9,991 (85.3%) | 719* (38.9%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 1,009 (7.4%) | |

| All general medicine, n=8,510 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 1,114* (18.4%) | 1,512 (61.9%) |

| 2 Midnights | 4,953 (81.6%) | 931* (38.1%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 183 (2.2%) | |

| Medicare general medicine, n=4,571 | ||

| <2 Midnights | 472* (14.3%) | 690 (54.2%) |

| 2 Midnights | 2,827 (85.7%) | 582* (45.8%) |

| Net change inpatient encounters | 110 (2.4%) | |

Encounters including surgical procedures on the so‐called inpatient‐only list will remain inpatient regardless of LOS. As we could not identify such encounters, we tested removal of all surgical stays under the overly conservative assumption that all short stay surgical patients would remain inpatient. Of 21,712 nonsurgical encounters that remained, there were 4074 <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 1146 2‐midnight observation encounters, yielding a net transition of 2928 (13.5%) inpatient encounters to observation encounters. Medicare encounters accounted for 8240 of these 21,712 (38.0%) nonsurgical encounters, with 1105 <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 653 2‐midnight observation encounters, yielding a net reclassification of 452 (5.5%) Medicare nonsurgical inpatient encounters to observation encounters.

Length of Stay and Diagnoses After Application of the 2‐Midnight Rule to Inpatient and Observation Encounters

Only 1 of the top 5 ICD‐9 codes (code 427: cardiac dysrhythmias) was shared between the 2‐midnight inpatient encounters and any observation encounter group. When the same criteria were applied to adult general medicine encounters, none of the top 5 ICD‐9 codes were shared (Table 3).

| All Encounters, n=36,193 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=6,723 (21.4%) | Inpatient Stays 2 Midnights, n=24,701 (78.6%) | Observation Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=3,454 (72.4%) | Observation Stays 2 Midnights n=1,315 (27.6%) | |||||

| ||||||||

| Day of admission | ||||||||

| Weekend (Saturday Sunday) | 1,026 (15.3%) | 4,032 (16.3%) | 781 (22.6%) | 348 (26.5%) | ||||

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 5,697 (84.7%) | 20,669 (83.7%) | 2,673 (77.4%) | 967 (73.5%) | ||||

| Transfer from another institution | 986 (14.7%) | 5,205 (21.1%) | 297 (8.6%) | 130 (9.9%) | ||||

| Top diagnosis codes | ||||||||

| ICD‐9 #1 | 996: Complications peculiar to specific procedure | 200 (3.0%) | 996: Complications peculiar to specific procedure | 1,355 (5.5%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 531 (15.4%) | 780: General symptoms | 124 (9.4%) |

| ICD‐9 #2 | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 195 (2.9%) | 715: Osteoarthrosis and allied disorders | 917 (3.7%) | 780: General symptoms | 235 (6.8%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 80 (6.1%) |

| ICD‐9 #3 | 722: Intervertebral disk disorder | 182 (2.7%) | 038: Septicemia | 689 (2.8%) | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 103 (3.0%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 48 (3.7%) |

| ICD‐9 #4 | 540: Acute appendicitis | 179 (2.7%) | 296: Episodic mood disorder | 619 (2.5%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 89 (2.6%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 38 (2.9%) |

| ICD‐9 #5 | V58: Encounter for other and unspecified procedures | 176 (2.6%) | 998: Other complications of procedures not elsewhere classified | 516 (2.1%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 56 (1.6%) | 599: Other disorders of urethra/urinary tract | 35 (2.7%) |

| Adult General Medicine Encounters, n=8,510 | ||||||||

| Inpatient Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=1,114 (18.4%) | Inpatient Stays 2 Midnights, n=4,953 (81.6%) | Observation Stays Shorter Than 2 Midnights, n=1,512 (61.9%) | Observation Stays 2 Midnights, n=931 (38.1%) | |||||

| Day of admission | ||||||||

| Weekend (Saturday Sunday) | 253 (22.7%) | 1,189 (24.0%) | 318 (21.0%) | 261 (28.0%) | ||||

| Weekday (MondayFriday) | 861 (77.3%) | 3,764 (76.0%) | 1,194 (79.0%) | 670 (72.0%) | ||||

| Transfer from another institution | 89 (8.0%) | 1,193 (24.1%) | 61 (4.0%) | 75 (8.1%) | ||||

| Top diagnosis codes | ||||||||

| ICD‐9 #1 | 415: Acute pulmonary heart disease | 57 (5.1%) | 038: Septicemia | 423 (8.5%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 315 (20.8%) | 780: General symptoms | 99 (10.6%) |

| ICD‐9 #2 | 276: Disorders of fluid/electrolyte, acid/base | 51 (4.6%) | 486: Pneumonia | 206 (4.2%) | 780: General symptoms | 138 (9.1%) | 786: Symptoms involving respiratory/other chest | 51 (5.5%) |

| ICD‐9 #3 | 682: Other cellulitis and abscess | 47 (4.2%) | 584: Acute kidney failure | 181 (3.7%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 47 (3.1%) | 789: Other symptoms involving abdomen/pelvis | 37 (4.0%) |

| ICD‐9 #4 | 427: Cardiac dysrhythmias | 43 (3.9%) | 577: Diseases of the pancreas | 181 (3.7%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 35 (2.3%) | 599: Other disorders of urethra/urinary tract | 30 (3.2%) |

| ICD‐9 #5 | 250: Diabetes mellitus | 40 (3.6%) | 682: Other cellulitis and abscess | 175 (3.5%) | 305: Nondependent abuse of drugs | 32 (2.1%) | 787: Symptoms involving digestive system | 28 (3.0%) |

Including all observation encounters across LOS, 4 of the 5 top ICD‐9 codes were the same for stays <2 midnights and 2 midnights. The same was true for short‐ and long‐stay general medicine observation encounters (Table 3).

For all observation encounters, 26.5% (348/1315) of 2‐midnight encounters started on a weekend compared to 22.6% (781/3454) of <2‐midnight encounters. For adult medicine observation, 28.0% (261/931) of 2‐midnight encounters started on a weekend compared to 21.0% (318/1512) of <2‐midnight encounters (Table 3).

Percentage of Observation Encounters Reaching 2 Midnights Based on Time of Hospitalization

Observation encounters starting before 8:00 am spanned 2 midnights 13.6% of the time, and those encounters starting after 4:00 pm crossed 2 midnights 31.2% of the time. Two of the 3 top ICD‐9 codes were the same across LOS, with similar findings for the adult general medicine‐only group (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Although CMS predicts that more patients will be classified as inpatients under the new rule, we determined the opposite, consistent with a recent report generated by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for 2012 Medicare beneficiaries.[8] Our results did not change when we excluded all surgical encounters to account for possible exclusions based on the surgical inpatient‐only list. Although a small percentage of Medicare adult general medicine patients may be reclassified as inpatients under the new rules, the net effect would be that many more hospital encounters will be billed under observation rather than inpatient status. These findings assume overall length of stay will remain unchanged under these rules, an assumption that may not hold true given the financial losses we predicted hospitals may face under this rule,[12] and potential pressures on individual physicians providing patient care.

Medicare has prioritized auditing <2‐midnight inpatient encounters under the assumption that many short inpatient encounters are actually misclassified observation encounters,[4, 8, 9] prompting us to investigate whether this was the case in our patient population. Although it did not use ICD‐9 diagnosis codes, the OIG report suggested that short‐stay inpatients and observation patients may be clinically similar.[8, 13] Using ICD‐9 codes, we found no overlap between the top ICD‐9 codes for adult general medicine <2‐midnight inpatient and observation encounters, and only 1 of 5 shared codes for these encounters across all service lines. These findings are counter to the OIG report, and suggest that <2‐midnight inpatients are different from observation patients at our institution, and that <2‐midnight inpatients should not be arbitrarily reclassified as observation based solely upon LOS.

We also found that the majority of top ICD‐9 codes within observation were the same regardless of LOS, suggesting that LOS does not reliably differentiate clinically different observation populations that merit different insurance coverage (Medicare Part A for 2‐midnight encounters, Medicare Part B for <2‐midnight encounters). This lack of a clear cut point may drive an overall increase in LOS to achieve 2 midnights, as common diagnosis codes can be justified for both <2‐midnight or 2‐midnight observation stays.

Finally, we found that external factors, such as the time of day and specific day (weekday vs weekend) of hospitalization, impact the likelihood of achieving a 2‐midnight stay. Patients hospitalized earlier in the day were less likely to span 2 midnights compared to later‐day encounters, suggesting that use of a full working day as the day of presentation is harmful to a patient's chance of gaining inpatient status. Observation hospitalizations starting on a weekend day were more likely to achieve 2 midnights, which likely reflects different resource allocation and hospital efficiency on weekends, yet it is unlikely that weekend midnights, if associated with any delay in care, will be counted toward a patient's cumulative 2‐midnight total. The CMS has further indicated that midnights accrued prior to transfer from 1 hospital to another will not count toward a cumulative 2‐midnight stay. Although it would seem likely that patients requiring transfer to a tertiary care center would meet inpatient criteria, 9% of our observation encounters were transferred from other acute care hospitals, and many will have lost attributable midnights accrued prior to transfer to our hospital. Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that issues entirely unrelated to diagnosis or clinical status will impact whether hospitalized patients will be classified as inpatient or observation under the new rule.

This study has several limitations. Our data were limited to a single Midwestern tertiary care academic medical center, and may not be applicable to other healthcare settings. Second, 1.5% (466) of our inpatient stays and 56 (1.2%) of our observation encounters lacked a referral source in our administrative database, although these deficiencies would not likely change the conclusions. Finally, the total number of observation encounters starting before 8:00 am and staying 2 midnights was small and therefore potentially subject to confounding. However, despite the fact that encounters beginning in the early morning hours may be different in ways unable to be measured in this study, encounter ICD‐9 codes were similar regardless of time of day.

Despite these limitations, our study raises concerns about the impact of CMS's new time‐driven observation rules on hospital practice patterns. We found distinctly different <2‐midnight inpatient ICD‐9 codes as compared to those for observation encounters. Reclassifying <2‐midnight inpatients as observation may inappropriately shift the financial burden of acute hospitalizations to patients who were previously eligible to receive Medicare inpatient benefits. We also demonstrated a decrease in billable inpatient encounters under the new rules, which may be countered by changes in hospital and provider practice to drive more admissions over the 2‐midnight threshold to avoid financial losses. These changes should be defensible under audit given the ambiguities of the rule we found in this study surrounding time of day of admission, weekend and transfer hospitalizations, and the fact that common observation ICD‐9 codes are similar across LOS. Ironically, the unintended consequence of the new rule may be to drive up hospital LOS, reduce efficiency, and increase the overall cost of care.

Our findings suggest that CMS should define observation care per its original intent: as a means to determine if a patient can safely return home after a short period of additional care.[6] Patients whose conditions necessitate an intensity and level of service beyond this narrow scope should be classified as full inpatients irrespective of LOS, whether that LOS is <2 midnights or 2 midnights. Policies that fail to reflect the original intent of observation status are unlikely to achieve the intended outcome of defining 2 distinct patient populations that merit different services and reimbursement.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrew LaRocque and Dan Dexter for their assistance with the data. Without their help, this article would not have been possible.

Disclosures: Dr. Graf reports receiving royalties from Smith & Nephew for patents he has assigned to them involving orthopedic implants. This is unrelated to the topic or content of this manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Editor's Note: On February 24, 2014, after this manuscript was published, CMS issued a rules clarification allowing midnights spent at a referral hospital prior to transfer to be counted in the cumulative 2 midnight tally to determine inpatient status.

Observation hospitalization is a growing phenomenon in the United States healthcare system.[1] For Medicare beneficiaries, observation encounters increased 33.6% from 2004 to 2011, with inpatient encounters decreasing by 7.8% over the same period.[2]

Observation length of stay has also increased. Medicare states that observation care should typically last <24 hours, and in only rare and exceptional cases exceed 48 hours. We and others have showed that observation stays, on average, do not meet this definition.[1, 3] At our institution, historically less than half of observation encounters discharge in under 24 hours, and 1 in 6 stay longer than 48 hours.[3]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a rules change effective October 1, 2013, in response to concern about recent increases in the length of time that CMS beneficiaries spend as hospital outpatients receiving observation services.[4] These rules shifted observation determination from clinical criteria, such as InterQual,[5] to a time‐based rule that hinges on a 2‐midnight cut point. Patients staying <2 midnights, with few exceptions, are now observation, and those staying 2 midnights are inpatients. This is important, as patients hospitalized as observation are technically outpatients, not covered by Medicare Part A hospital insurance, and ineligible for skilled nursing facility benefits.[3, 6]

Although challenges with observation status in general are well described,[1, 3, 7] the potential impact of the 2‐midnight rule is not fully known. The purpose of our descriptive study was to examine how the new rules, retrospectively applied to recent encounters, would affect our hospital encounters, with a separate analysis of Medicare encounters and adult general medicine encounters. First, as CMS predicted a net shift from outpatient to inpatient stays[8] under the new rule, we attempted to determine whether this rule would actually reduce observation encounter frequency. Second, as CMS has cited persistently large improper payment rates in short‐stay hospital inpatient claims[4] and intends to audit <2‐midnight inpatient encounters under the assumption that many are misclassified observation stays,[4, 8, 9] we sought to determine if short‐stay inpatient and observation encounters were truly the same. Third, as insurance coverage will change based on the 2‐midnight cut point, we sought to determine whether 2 midnights separated distinct clinical populations within observation status, making the rule logical and fair. Finally, we sought to determine whether external factors, such as time of admission, day of week of admission, and transfer to our institution would impact how patients may be classified under the new rule.

METHODS

Study Population

Our methods have been described previously[3] with the exception of the updated dates of inclusion. Briefly, we analyzed all observation and inpatient encounters at University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics (UWHC) and the adjacent American Family Children's Hospital, a tertiary care referral academic medical center in Madison, Wisconsin,[10] with start date between January 1, 2012 and February 28, 2013. Six encounters with length of stay (LOS) >6 months were censored as they were not discharged by the time of data abstraction, and 3 encounters were removed due to erroneous encounter discharge dates. Patients with all insurance types were included in anticipation that commercial payors will follow Medicare rules changes. The University of Wisconsin (UW) Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Data Sources

Data were abstracted from the UW Health Sciences electronic medical record and ancillary data systems by the UWHC Business Planning and Analysis Department. Variables included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity), insurance type, and characteristics of hospitalization (admission service, day of week encounter began, acute/unscheduled presentation, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] codes, LOS, transfer from other hospital). We considered inpatient admission start time to be departure from the emergency department (ED) or arrival at our hospital if the encounter was a transfer from another facility. Observation start time also hinged on arrival at our hospital if the encounter was transferred from another facility, but for observation encounters arriving from the ED, the ED rooming time was used as the encounter start based on conservative interpretation of CMS rules for observation start time under the 2‐midnight rule.[11] Discharge time for all encounters was considered physical discharge from the ward. Observation status decisions were made by the admitting physician, with as‐needed guidance by case management staff and utilization review physicians using InterQual Criteria (McKesson Corp, San Francisco, CA),[5] a reference historically used by CMS auditors to determine status.

Evaluation of the 2‐Midnight Rule

All encounters were stratified based on a stay of <2 midnights or 2 midnights. Because general medicine patients comprise the bulk of observation patients,[3] the subset of encounters occurring on the hospital's 4 hospitalist medicine services, 3 general medicine resident services, and 1 adult nonobstetrics family medicine service, collectively termed adult general medicine, were also evaluated separately. Medicare encounters were also evaluated separately.

We first specifically compared <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and 2‐midnight observation encounters during the study period to determine the net number of encounters that would lose inpatient status (<2‐midnight inpatient encounters) and that would gain inpatient status (2‐midnight observation encounters) under the new rules. Subtracting the absolute number of <2‐midnight inpatient encounters from the 2‐midnight observation encounters results in the net loss or gain of inpatient encounters, assuming LOS does not change. Second, we compared ICD‐9 codes between <2‐midnight inpatient encounters and observation encounters to determine if these 2 groups were clinically distinguishable. Third, we compared diagnosis codes between observation encounters lasting <2 midnights and 2 midnights to establish whether the 2‐midnight cut point defines distinct patient groups within observation. Finally, we evaluated all observation encounters to determine whether the time of admission, the day of admission (weekday vs weekend), or whether the encounter had been transferred from another facility impacted encounter categorization under the new rules.

Statistical Methods