User login

Transitioning from pediatric to adult care

Airways Disorders Network

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

For young adults with chronic health conditions, the process of transitioning to adult health care is complicated, resulting in frustration for patients and families, and clinicians, as well as increased morbidity and mortality (Varty et al. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;55:201). As such, there have been efforts to determine practices that can minimize risk and improve satisfaction with the transition process.

The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health developed the “Got Transition” program with input from pediatric and adult clinicians, as well as patient advocates (White, et al. Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0. Washington, DC: Got Transition, The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, July 2020). CF R.I.S.E is a similar program aimed specifically at improving the transition to adult care among patients with cystic fibrosis (www.cfrise.com). Got Transition provides the following recommendations pertinent to both pediatric and adult providers.

Pediatric clinics should start to assess transition readiness in early adolescence, and provide training pertinent to any skill gaps identified. This may include knowledge about condition-specific self-care skills, as well as navigation of the health care system. An individualized plan can then be developed, including timing of transition and identification of an appropriate adult provider.

The transfer should include communication between the pediatric and adult care providers prior to and, if needed, after the patient’s first appointment with the adult provider. Adult clinics can enhance the transition process by establishing a method to welcome transitioning young adult patients and orient them to the practice, addressing patient concerns regarding the transition, and assessing the patients’ self-management skills with resources provided, as needed.

Both pediatric and adult providers have a role in helping patients transition safely and smoothly from pediatric to adult care.

Sarah Cohen, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Airways Disorders Network

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

For young adults with chronic health conditions, the process of transitioning to adult health care is complicated, resulting in frustration for patients and families, and clinicians, as well as increased morbidity and mortality (Varty et al. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;55:201). As such, there have been efforts to determine practices that can minimize risk and improve satisfaction with the transition process.

The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health developed the “Got Transition” program with input from pediatric and adult clinicians, as well as patient advocates (White, et al. Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0. Washington, DC: Got Transition, The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, July 2020). CF R.I.S.E is a similar program aimed specifically at improving the transition to adult care among patients with cystic fibrosis (www.cfrise.com). Got Transition provides the following recommendations pertinent to both pediatric and adult providers.

Pediatric clinics should start to assess transition readiness in early adolescence, and provide training pertinent to any skill gaps identified. This may include knowledge about condition-specific self-care skills, as well as navigation of the health care system. An individualized plan can then be developed, including timing of transition and identification of an appropriate adult provider.

The transfer should include communication between the pediatric and adult care providers prior to and, if needed, after the patient’s first appointment with the adult provider. Adult clinics can enhance the transition process by establishing a method to welcome transitioning young adult patients and orient them to the practice, addressing patient concerns regarding the transition, and assessing the patients’ self-management skills with resources provided, as needed.

Both pediatric and adult providers have a role in helping patients transition safely and smoothly from pediatric to adult care.

Sarah Cohen, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Airways Disorders Network

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

For young adults with chronic health conditions, the process of transitioning to adult health care is complicated, resulting in frustration for patients and families, and clinicians, as well as increased morbidity and mortality (Varty et al. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;55:201). As such, there have been efforts to determine practices that can minimize risk and improve satisfaction with the transition process.

The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health developed the “Got Transition” program with input from pediatric and adult clinicians, as well as patient advocates (White, et al. Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0. Washington, DC: Got Transition, The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, July 2020). CF R.I.S.E is a similar program aimed specifically at improving the transition to adult care among patients with cystic fibrosis (www.cfrise.com). Got Transition provides the following recommendations pertinent to both pediatric and adult providers.

Pediatric clinics should start to assess transition readiness in early adolescence, and provide training pertinent to any skill gaps identified. This may include knowledge about condition-specific self-care skills, as well as navigation of the health care system. An individualized plan can then be developed, including timing of transition and identification of an appropriate adult provider.

The transfer should include communication between the pediatric and adult care providers prior to and, if needed, after the patient’s first appointment with the adult provider. Adult clinics can enhance the transition process by establishing a method to welcome transitioning young adult patients and orient them to the practice, addressing patient concerns regarding the transition, and assessing the patients’ self-management skills with resources provided, as needed.

Both pediatric and adult providers have a role in helping patients transition safely and smoothly from pediatric to adult care.

Sarah Cohen, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Mirikizumab performs well in UC, new data show

, according to new findings from the phase 3 LUCENT-1 induction and LUCENT-2 maintenance trials. The findings were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Mirikizumab manufacturer Eli Lilly, which funded the study, is hoping the drug will become the first IL-23 inhibitor to be approved in the United States for ulcerative colitis. The drug targets the p19 subunit that is unique to IL-23. Ustekinumab, which targets the p40 subunit that is shared by IL-12 and IL-23, has been approved for UC and Crohn’s disease. Risankizumab, which targets the IL-23 p19 subunit, has been approved for Crohn’s treatment.

Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration rejected Lilly’s mirikizumab application over manufacturing issues, with no concerns about the clinical data, safety, or labelling. The company said it was working with the FDA to resolve the concerns, and hopes to “launch mirikizumab in the U.S. as soon as possible.” The drug has already been approved in Japan for moderately and severely active ulcerative colitis, and the drug was reviewed favorably by the European Medicines Agency.

Since 2014, the market size of interleukin inhibitors has grown fivefold with the greatest share belonging to IL-23 inhibitors.

The induction trial included 1,281 patients with moderately or severely active ulcerative colitis (UC), and 544 patients who had a response to mirikizumab were randomized again in the maintenance phase.

Significantly more patients in the mirikizumab arm – 24.1% (P < .001) – had clinical remission at week 12, although there was a high placebo remission rate, as is often seen in UC trials, at 13.3%. At week 40 of the maintenance trial, 49.9% of those on mirikizumab had clinical remission, compared to 25.1% for placebo (P < .001).

Mirikizumab also performed better than placebo on the trial’s five secondary endpoints: glucocorticoid-free clinical remission (44.9% to 21.8%), maintenance of clinical remission (63.6% to 36.9%), endoscopic remission (58.6% to 29.1%), histologic-endoscopic mucosal remission (43.3 %), and bowel-urgency remission (42.9% to 25.0%) (P < .001 for all).

Researchers led by Geert D’Haens, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, emphasized the effects on acute inflammatory cell infiltration.

“Current recommendations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis include increasingly rigorous goals beyond symptomatic or endoscopic improvement,” the authors wrote. “Recent literature has recommended the absence of intraepithelial neutrophils as a minimal requirement for remission on the basis of histologic testing. After 1 year of mirikizumab treatment, more than 40% of the patients in the LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 trials had no mucosal neutrophils. “

Urgency NRS (Numeric Rating Scale) – a measure developed by Lilly in which patients report the urgency of bowel movements over the previous 24 hours – was used in the trial.

“Many patients with ulcerative colitis consider control of bowel movements to be more important than rectal bleeding or stool frequency,” the researchers said. “In the induction trial, patients reported reductions in bowel urgency with mirikizumab therapy, which were sustained during the maintenance trial.”

Of the 1,217 patients treated with mirikizumab during the placebo-controlled and non–placebo-controlled periods, opportunistic infections were seen in 15, with 6 herpes zoster infections. One case of an opportunistic infection was seen in a patient receiving placebo in the induction trial.

Cancer was seen in eight of the mirikizumab-treated patients, with adenocarcinoma of the colon in two patients in the induction trial. No cancers were seen in patients receiving placebo in induction.

“Additional and longer trials are ongoing,” the researchers said, “to further assess the efficacy and safety of mirikizumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis.”

The authors disclosed consultancies, or other relationships, with a number of pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the maker of mirikizumab.

, according to new findings from the phase 3 LUCENT-1 induction and LUCENT-2 maintenance trials. The findings were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Mirikizumab manufacturer Eli Lilly, which funded the study, is hoping the drug will become the first IL-23 inhibitor to be approved in the United States for ulcerative colitis. The drug targets the p19 subunit that is unique to IL-23. Ustekinumab, which targets the p40 subunit that is shared by IL-12 and IL-23, has been approved for UC and Crohn’s disease. Risankizumab, which targets the IL-23 p19 subunit, has been approved for Crohn’s treatment.

Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration rejected Lilly’s mirikizumab application over manufacturing issues, with no concerns about the clinical data, safety, or labelling. The company said it was working with the FDA to resolve the concerns, and hopes to “launch mirikizumab in the U.S. as soon as possible.” The drug has already been approved in Japan for moderately and severely active ulcerative colitis, and the drug was reviewed favorably by the European Medicines Agency.

Since 2014, the market size of interleukin inhibitors has grown fivefold with the greatest share belonging to IL-23 inhibitors.

The induction trial included 1,281 patients with moderately or severely active ulcerative colitis (UC), and 544 patients who had a response to mirikizumab were randomized again in the maintenance phase.

Significantly more patients in the mirikizumab arm – 24.1% (P < .001) – had clinical remission at week 12, although there was a high placebo remission rate, as is often seen in UC trials, at 13.3%. At week 40 of the maintenance trial, 49.9% of those on mirikizumab had clinical remission, compared to 25.1% for placebo (P < .001).

Mirikizumab also performed better than placebo on the trial’s five secondary endpoints: glucocorticoid-free clinical remission (44.9% to 21.8%), maintenance of clinical remission (63.6% to 36.9%), endoscopic remission (58.6% to 29.1%), histologic-endoscopic mucosal remission (43.3 %), and bowel-urgency remission (42.9% to 25.0%) (P < .001 for all).

Researchers led by Geert D’Haens, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, emphasized the effects on acute inflammatory cell infiltration.

“Current recommendations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis include increasingly rigorous goals beyond symptomatic or endoscopic improvement,” the authors wrote. “Recent literature has recommended the absence of intraepithelial neutrophils as a minimal requirement for remission on the basis of histologic testing. After 1 year of mirikizumab treatment, more than 40% of the patients in the LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 trials had no mucosal neutrophils. “

Urgency NRS (Numeric Rating Scale) – a measure developed by Lilly in which patients report the urgency of bowel movements over the previous 24 hours – was used in the trial.

“Many patients with ulcerative colitis consider control of bowel movements to be more important than rectal bleeding or stool frequency,” the researchers said. “In the induction trial, patients reported reductions in bowel urgency with mirikizumab therapy, which were sustained during the maintenance trial.”

Of the 1,217 patients treated with mirikizumab during the placebo-controlled and non–placebo-controlled periods, opportunistic infections were seen in 15, with 6 herpes zoster infections. One case of an opportunistic infection was seen in a patient receiving placebo in the induction trial.

Cancer was seen in eight of the mirikizumab-treated patients, with adenocarcinoma of the colon in two patients in the induction trial. No cancers were seen in patients receiving placebo in induction.

“Additional and longer trials are ongoing,” the researchers said, “to further assess the efficacy and safety of mirikizumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis.”

The authors disclosed consultancies, or other relationships, with a number of pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the maker of mirikizumab.

, according to new findings from the phase 3 LUCENT-1 induction and LUCENT-2 maintenance trials. The findings were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Mirikizumab manufacturer Eli Lilly, which funded the study, is hoping the drug will become the first IL-23 inhibitor to be approved in the United States for ulcerative colitis. The drug targets the p19 subunit that is unique to IL-23. Ustekinumab, which targets the p40 subunit that is shared by IL-12 and IL-23, has been approved for UC and Crohn’s disease. Risankizumab, which targets the IL-23 p19 subunit, has been approved for Crohn’s treatment.

Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration rejected Lilly’s mirikizumab application over manufacturing issues, with no concerns about the clinical data, safety, or labelling. The company said it was working with the FDA to resolve the concerns, and hopes to “launch mirikizumab in the U.S. as soon as possible.” The drug has already been approved in Japan for moderately and severely active ulcerative colitis, and the drug was reviewed favorably by the European Medicines Agency.

Since 2014, the market size of interleukin inhibitors has grown fivefold with the greatest share belonging to IL-23 inhibitors.

The induction trial included 1,281 patients with moderately or severely active ulcerative colitis (UC), and 544 patients who had a response to mirikizumab were randomized again in the maintenance phase.

Significantly more patients in the mirikizumab arm – 24.1% (P < .001) – had clinical remission at week 12, although there was a high placebo remission rate, as is often seen in UC trials, at 13.3%. At week 40 of the maintenance trial, 49.9% of those on mirikizumab had clinical remission, compared to 25.1% for placebo (P < .001).

Mirikizumab also performed better than placebo on the trial’s five secondary endpoints: glucocorticoid-free clinical remission (44.9% to 21.8%), maintenance of clinical remission (63.6% to 36.9%), endoscopic remission (58.6% to 29.1%), histologic-endoscopic mucosal remission (43.3 %), and bowel-urgency remission (42.9% to 25.0%) (P < .001 for all).

Researchers led by Geert D’Haens, MD, PhD, professor of gastroenterology at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, emphasized the effects on acute inflammatory cell infiltration.

“Current recommendations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis include increasingly rigorous goals beyond symptomatic or endoscopic improvement,” the authors wrote. “Recent literature has recommended the absence of intraepithelial neutrophils as a minimal requirement for remission on the basis of histologic testing. After 1 year of mirikizumab treatment, more than 40% of the patients in the LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 trials had no mucosal neutrophils. “

Urgency NRS (Numeric Rating Scale) – a measure developed by Lilly in which patients report the urgency of bowel movements over the previous 24 hours – was used in the trial.

“Many patients with ulcerative colitis consider control of bowel movements to be more important than rectal bleeding or stool frequency,” the researchers said. “In the induction trial, patients reported reductions in bowel urgency with mirikizumab therapy, which were sustained during the maintenance trial.”

Of the 1,217 patients treated with mirikizumab during the placebo-controlled and non–placebo-controlled periods, opportunistic infections were seen in 15, with 6 herpes zoster infections. One case of an opportunistic infection was seen in a patient receiving placebo in the induction trial.

Cancer was seen in eight of the mirikizumab-treated patients, with adenocarcinoma of the colon in two patients in the induction trial. No cancers were seen in patients receiving placebo in induction.

“Additional and longer trials are ongoing,” the researchers said, “to further assess the efficacy and safety of mirikizumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis.”

The authors disclosed consultancies, or other relationships, with a number of pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the maker of mirikizumab.

Does private equity ensure survival of GI practices?

CHICAGO – In this age of corporate megamergers, private practice gastroenterologists are increasingly weighing the pros and cons of selling their practices to private equity firms.

It’s becoming more difficult for solo or small group practices to go it alone. While there may be advantages in selling a medical practice to a private equity firm, physicians could be trading a degree of freedom for financial certainty and relief from administrative burdens, according to Klaus Mergener, MD, PhD, MBA, AGAF, a clinical gastroenterologist, affiliate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and chief medical officer of Pentax Medical’s Lifecare Division.

“Over the last decades, and ongoing, there have been massive downward pressures on reimbursements and costs are rising. Practices have tried to compensate, and they’ve added ancillary revenue streams, and they’ve tried to cut costs internally. It’s fair to say that depending on the local market, many practices find that one of the last viable options is essentially to spread overhead costs – meaning you have to get larger and you have to merge into larger entities,” he said on May 6 during a presentation at the annual Digestive Diseases Week® meeting.

The first independent gastroenterology practice was purchased by a private equity firm in 2016. Today, more than 1,000 gastroenterologists have been acquired by private equity firms, which amounts to a total value in excess of $1 billion.

The pace at which private equity firms are buying private medical practices is accelerating. On April 26, Kaiser Permanente – with 39 hospitals and 24,000 physicians – announced that it had acquired Geisinger Health System, a regional health care provider in Pennsylvania with 10 hospitals, forming a new entity called Risant Health.

Dr. Mergener likened the situation to the story of David and Goliath. David famously defeated the much larger and more powerful Goliath, but the metaphor is imperfect, because small private practices are running out of rocks to sling at the big guys.

In some small, rural markets with no significant competition, it may be possible for small practices to survive through mergers, “but in most U.S. markets, it’s fair to say that ... practices have found it hard to merge without external help. There are egos involved, there are many hurdles, and this is where private equity has essentially moved in as catalyst,” Dr. Mergener said.

Employees of large entities

Other physicians, however, say that while acquisition may seem inevitable, private equity is an option for survival.

“I don’t think this means the demise of private practice,“ said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF , chief medical officer at SonarMD, a Chicago-based company that specializes in facilitating managing the care of patients with chronic conditions.

“I think that private equity is just another way of aggregating GI doctors into an employment situation,” he said. “It’s just a different tool, and we can argue all day as to whether it’s the right tool, but it’s a tool no different than employment by a hospital. You can work for a hospital or you can work for a private equity funded group, but in the end, you’re an employee of a large entity.”

Michael Weinstein, MD, AGAF, president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care, a practice in Washington, and managing partner of the Metropolitan Gastroenterology Group Division, a medical group practice in Silver Spring, Md., advised taking a long and hard look before taking the leap into the hands of private equity.

“You have to have a strategy, but you have to know what you have and what you need. Ask yourself whether private equity is what you really need. They’re not in the business of making you a better practice,” he said. “Once you do it, you’re no longer in control of your future. Somebody else is in control of your future.”

Private equity firms sell a bill of goods

“They say, ‘We’re going to improve your services, we’re going to bring you tech, we’re going to negotiate better contracts and do all these things for you.’ Ninety percent of it is a lie, because that’s not what they’re going to do. They’re just going to try to increase the bottom line, bolt down a few more practices, increase the gross revenue, and thereby increase the net profit from where it was before, not necessarily because they’re making better lives for the individual providers. They’re just adding more cows to the field, but every cow is the same as far as they’re concerned. They really don’t care about the production of milk,” Dr. Weinstein said.

A few years ago, his practice considered whether private equity would be a good option. His practice, he said, needed to be bigger and more effective and efficient. Instead, his practice formed a partnership with PE GI Solutions (formerly Physicians Endoscopy), a developer and manager of endoscopic ambulatory surgery centers.

In Dallas, private equity firms have increased reimbursements for Texas Digestive Disease Consultants.

“Our practice went through mergers, acquisitions, and now, with private equity coming onto the scene, it’s completely different,” said Kimberly M. Persley, MD, AGAF, a partner with Texas Digestive Disease Consultants and a member of the GI & Hepatology News board of editors.

“We were a five-person independent group negotiating contracts, getting cut every other year by some payer because they negotiated a better price with someone else. And having to go through that process every year when all we really want to do is take care of patients. Private equity adds to our group practice by having someone dedicated to negotiating these contracts, and getting reimbursed far more than we ever did prior to our involvement with private equity,” she said.

How it works

In the typical model, a private equity partner purchases the practice and creates a management services organization (MSO), which provides nonclinical services to the practice, theoretically freeing the physicians from the administrative burdens of day-to-day practice.

The practice then becomes the care center managed by the MSO, and the physicians in the practice at the time of the acquisition get stock in the MSO. “They sell a portion of their annual income, so going forward they’re making less money initially, until some of that is being recovered by higher efficiencies. They get an upfront check at a multiple of the income they just sold, and that provides the initial incentive. Then the entity is grown by adding other practices through the same mechanism,” Dr. Mergener said.

After about 5 years, the private equity partner typically sells the MSO to another, probably even larger buyer, and the cycle starts again.

In addition to the upfront incentive that makes practice mergers and consolidation work, the arrangement gives the GI practice access to top-notch administrators, as well as access to capital for investments such as information technology infrastructure, digital health, and data analytics.

He cautioned that it’s crucial for practices to enter the marriage with eyes wide open and be very careful in choosing the private equity partner.

“The goal is to find a partner that has values and a vision that matches the practice’s. In theory, they should be pulling on the same side of the rope, because if it’s a high-quality practice and efficiencies are being improved, more practices should be more likely to join,” which will benefit physicians, patients, and the private equity partner alike, Dr. Mergener said.

Although the private equity construct has been successful in the short term for many practices, it’s less clear what will happen long-term. There is a risk that after 5 years there won’t be a buyer for the MSO at the expected price, which may result in complex financial transactions that could leave the MSO in debt. In such a scenario, physician employees would not be personally liable, but might suffer the consequences of a failing or unsuccessful operation, Dr. Mergener said.

Dr. Mergener’s talk was presented as part of a an ASGE Presidential Plenary held during DDW 2023. He disclosed consulting, honoraria, advisory board activity or stock options from various corporations, but reported having no relationships with private equity.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – In this age of corporate megamergers, private practice gastroenterologists are increasingly weighing the pros and cons of selling their practices to private equity firms.

It’s becoming more difficult for solo or small group practices to go it alone. While there may be advantages in selling a medical practice to a private equity firm, physicians could be trading a degree of freedom for financial certainty and relief from administrative burdens, according to Klaus Mergener, MD, PhD, MBA, AGAF, a clinical gastroenterologist, affiliate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and chief medical officer of Pentax Medical’s Lifecare Division.

“Over the last decades, and ongoing, there have been massive downward pressures on reimbursements and costs are rising. Practices have tried to compensate, and they’ve added ancillary revenue streams, and they’ve tried to cut costs internally. It’s fair to say that depending on the local market, many practices find that one of the last viable options is essentially to spread overhead costs – meaning you have to get larger and you have to merge into larger entities,” he said on May 6 during a presentation at the annual Digestive Diseases Week® meeting.

The first independent gastroenterology practice was purchased by a private equity firm in 2016. Today, more than 1,000 gastroenterologists have been acquired by private equity firms, which amounts to a total value in excess of $1 billion.

The pace at which private equity firms are buying private medical practices is accelerating. On April 26, Kaiser Permanente – with 39 hospitals and 24,000 physicians – announced that it had acquired Geisinger Health System, a regional health care provider in Pennsylvania with 10 hospitals, forming a new entity called Risant Health.

Dr. Mergener likened the situation to the story of David and Goliath. David famously defeated the much larger and more powerful Goliath, but the metaphor is imperfect, because small private practices are running out of rocks to sling at the big guys.

In some small, rural markets with no significant competition, it may be possible for small practices to survive through mergers, “but in most U.S. markets, it’s fair to say that ... practices have found it hard to merge without external help. There are egos involved, there are many hurdles, and this is where private equity has essentially moved in as catalyst,” Dr. Mergener said.

Employees of large entities

Other physicians, however, say that while acquisition may seem inevitable, private equity is an option for survival.

“I don’t think this means the demise of private practice,“ said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF , chief medical officer at SonarMD, a Chicago-based company that specializes in facilitating managing the care of patients with chronic conditions.

“I think that private equity is just another way of aggregating GI doctors into an employment situation,” he said. “It’s just a different tool, and we can argue all day as to whether it’s the right tool, but it’s a tool no different than employment by a hospital. You can work for a hospital or you can work for a private equity funded group, but in the end, you’re an employee of a large entity.”

Michael Weinstein, MD, AGAF, president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care, a practice in Washington, and managing partner of the Metropolitan Gastroenterology Group Division, a medical group practice in Silver Spring, Md., advised taking a long and hard look before taking the leap into the hands of private equity.

“You have to have a strategy, but you have to know what you have and what you need. Ask yourself whether private equity is what you really need. They’re not in the business of making you a better practice,” he said. “Once you do it, you’re no longer in control of your future. Somebody else is in control of your future.”

Private equity firms sell a bill of goods

“They say, ‘We’re going to improve your services, we’re going to bring you tech, we’re going to negotiate better contracts and do all these things for you.’ Ninety percent of it is a lie, because that’s not what they’re going to do. They’re just going to try to increase the bottom line, bolt down a few more practices, increase the gross revenue, and thereby increase the net profit from where it was before, not necessarily because they’re making better lives for the individual providers. They’re just adding more cows to the field, but every cow is the same as far as they’re concerned. They really don’t care about the production of milk,” Dr. Weinstein said.

A few years ago, his practice considered whether private equity would be a good option. His practice, he said, needed to be bigger and more effective and efficient. Instead, his practice formed a partnership with PE GI Solutions (formerly Physicians Endoscopy), a developer and manager of endoscopic ambulatory surgery centers.

In Dallas, private equity firms have increased reimbursements for Texas Digestive Disease Consultants.

“Our practice went through mergers, acquisitions, and now, with private equity coming onto the scene, it’s completely different,” said Kimberly M. Persley, MD, AGAF, a partner with Texas Digestive Disease Consultants and a member of the GI & Hepatology News board of editors.

“We were a five-person independent group negotiating contracts, getting cut every other year by some payer because they negotiated a better price with someone else. And having to go through that process every year when all we really want to do is take care of patients. Private equity adds to our group practice by having someone dedicated to negotiating these contracts, and getting reimbursed far more than we ever did prior to our involvement with private equity,” she said.

How it works

In the typical model, a private equity partner purchases the practice and creates a management services organization (MSO), which provides nonclinical services to the practice, theoretically freeing the physicians from the administrative burdens of day-to-day practice.

The practice then becomes the care center managed by the MSO, and the physicians in the practice at the time of the acquisition get stock in the MSO. “They sell a portion of their annual income, so going forward they’re making less money initially, until some of that is being recovered by higher efficiencies. They get an upfront check at a multiple of the income they just sold, and that provides the initial incentive. Then the entity is grown by adding other practices through the same mechanism,” Dr. Mergener said.

After about 5 years, the private equity partner typically sells the MSO to another, probably even larger buyer, and the cycle starts again.

In addition to the upfront incentive that makes practice mergers and consolidation work, the arrangement gives the GI practice access to top-notch administrators, as well as access to capital for investments such as information technology infrastructure, digital health, and data analytics.

He cautioned that it’s crucial for practices to enter the marriage with eyes wide open and be very careful in choosing the private equity partner.

“The goal is to find a partner that has values and a vision that matches the practice’s. In theory, they should be pulling on the same side of the rope, because if it’s a high-quality practice and efficiencies are being improved, more practices should be more likely to join,” which will benefit physicians, patients, and the private equity partner alike, Dr. Mergener said.

Although the private equity construct has been successful in the short term for many practices, it’s less clear what will happen long-term. There is a risk that after 5 years there won’t be a buyer for the MSO at the expected price, which may result in complex financial transactions that could leave the MSO in debt. In such a scenario, physician employees would not be personally liable, but might suffer the consequences of a failing or unsuccessful operation, Dr. Mergener said.

Dr. Mergener’s talk was presented as part of a an ASGE Presidential Plenary held during DDW 2023. He disclosed consulting, honoraria, advisory board activity or stock options from various corporations, but reported having no relationships with private equity.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – In this age of corporate megamergers, private practice gastroenterologists are increasingly weighing the pros and cons of selling their practices to private equity firms.

It’s becoming more difficult for solo or small group practices to go it alone. While there may be advantages in selling a medical practice to a private equity firm, physicians could be trading a degree of freedom for financial certainty and relief from administrative burdens, according to Klaus Mergener, MD, PhD, MBA, AGAF, a clinical gastroenterologist, affiliate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and chief medical officer of Pentax Medical’s Lifecare Division.

“Over the last decades, and ongoing, there have been massive downward pressures on reimbursements and costs are rising. Practices have tried to compensate, and they’ve added ancillary revenue streams, and they’ve tried to cut costs internally. It’s fair to say that depending on the local market, many practices find that one of the last viable options is essentially to spread overhead costs – meaning you have to get larger and you have to merge into larger entities,” he said on May 6 during a presentation at the annual Digestive Diseases Week® meeting.

The first independent gastroenterology practice was purchased by a private equity firm in 2016. Today, more than 1,000 gastroenterologists have been acquired by private equity firms, which amounts to a total value in excess of $1 billion.

The pace at which private equity firms are buying private medical practices is accelerating. On April 26, Kaiser Permanente – with 39 hospitals and 24,000 physicians – announced that it had acquired Geisinger Health System, a regional health care provider in Pennsylvania with 10 hospitals, forming a new entity called Risant Health.

Dr. Mergener likened the situation to the story of David and Goliath. David famously defeated the much larger and more powerful Goliath, but the metaphor is imperfect, because small private practices are running out of rocks to sling at the big guys.

In some small, rural markets with no significant competition, it may be possible for small practices to survive through mergers, “but in most U.S. markets, it’s fair to say that ... practices have found it hard to merge without external help. There are egos involved, there are many hurdles, and this is where private equity has essentially moved in as catalyst,” Dr. Mergener said.

Employees of large entities

Other physicians, however, say that while acquisition may seem inevitable, private equity is an option for survival.

“I don’t think this means the demise of private practice,“ said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF , chief medical officer at SonarMD, a Chicago-based company that specializes in facilitating managing the care of patients with chronic conditions.

“I think that private equity is just another way of aggregating GI doctors into an employment situation,” he said. “It’s just a different tool, and we can argue all day as to whether it’s the right tool, but it’s a tool no different than employment by a hospital. You can work for a hospital or you can work for a private equity funded group, but in the end, you’re an employee of a large entity.”

Michael Weinstein, MD, AGAF, president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care, a practice in Washington, and managing partner of the Metropolitan Gastroenterology Group Division, a medical group practice in Silver Spring, Md., advised taking a long and hard look before taking the leap into the hands of private equity.

“You have to have a strategy, but you have to know what you have and what you need. Ask yourself whether private equity is what you really need. They’re not in the business of making you a better practice,” he said. “Once you do it, you’re no longer in control of your future. Somebody else is in control of your future.”

Private equity firms sell a bill of goods

“They say, ‘We’re going to improve your services, we’re going to bring you tech, we’re going to negotiate better contracts and do all these things for you.’ Ninety percent of it is a lie, because that’s not what they’re going to do. They’re just going to try to increase the bottom line, bolt down a few more practices, increase the gross revenue, and thereby increase the net profit from where it was before, not necessarily because they’re making better lives for the individual providers. They’re just adding more cows to the field, but every cow is the same as far as they’re concerned. They really don’t care about the production of milk,” Dr. Weinstein said.

A few years ago, his practice considered whether private equity would be a good option. His practice, he said, needed to be bigger and more effective and efficient. Instead, his practice formed a partnership with PE GI Solutions (formerly Physicians Endoscopy), a developer and manager of endoscopic ambulatory surgery centers.

In Dallas, private equity firms have increased reimbursements for Texas Digestive Disease Consultants.

“Our practice went through mergers, acquisitions, and now, with private equity coming onto the scene, it’s completely different,” said Kimberly M. Persley, MD, AGAF, a partner with Texas Digestive Disease Consultants and a member of the GI & Hepatology News board of editors.

“We were a five-person independent group negotiating contracts, getting cut every other year by some payer because they negotiated a better price with someone else. And having to go through that process every year when all we really want to do is take care of patients. Private equity adds to our group practice by having someone dedicated to negotiating these contracts, and getting reimbursed far more than we ever did prior to our involvement with private equity,” she said.

How it works

In the typical model, a private equity partner purchases the practice and creates a management services organization (MSO), which provides nonclinical services to the practice, theoretically freeing the physicians from the administrative burdens of day-to-day practice.

The practice then becomes the care center managed by the MSO, and the physicians in the practice at the time of the acquisition get stock in the MSO. “They sell a portion of their annual income, so going forward they’re making less money initially, until some of that is being recovered by higher efficiencies. They get an upfront check at a multiple of the income they just sold, and that provides the initial incentive. Then the entity is grown by adding other practices through the same mechanism,” Dr. Mergener said.

After about 5 years, the private equity partner typically sells the MSO to another, probably even larger buyer, and the cycle starts again.

In addition to the upfront incentive that makes practice mergers and consolidation work, the arrangement gives the GI practice access to top-notch administrators, as well as access to capital for investments such as information technology infrastructure, digital health, and data analytics.

He cautioned that it’s crucial for practices to enter the marriage with eyes wide open and be very careful in choosing the private equity partner.

“The goal is to find a partner that has values and a vision that matches the practice’s. In theory, they should be pulling on the same side of the rope, because if it’s a high-quality practice and efficiencies are being improved, more practices should be more likely to join,” which will benefit physicians, patients, and the private equity partner alike, Dr. Mergener said.

Although the private equity construct has been successful in the short term for many practices, it’s less clear what will happen long-term. There is a risk that after 5 years there won’t be a buyer for the MSO at the expected price, which may result in complex financial transactions that could leave the MSO in debt. In such a scenario, physician employees would not be personally liable, but might suffer the consequences of a failing or unsuccessful operation, Dr. Mergener said.

Dr. Mergener’s talk was presented as part of a an ASGE Presidential Plenary held during DDW 2023. He disclosed consulting, honoraria, advisory board activity or stock options from various corporations, but reported having no relationships with private equity.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

AT DDW 2023

Evidence weighed for suicide/self-harm with obesity drugs

Following reports that the European Medicines Agency is looking into instances of suicide or self-harm after patients took the weight loss drugs semaglutide or liraglutide, the manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, issued a statement to this news organization in which it says it “remains confident in the benefit risk profile of the products and remains committed to ensuring patient safety.”

U.S. experts say they haven’t personally seen this adverse effect in any patients except for one isolated case. An increase in suicidal ideation, particularly among younger people, has been reported following bariatric surgery for weight loss.

In the United States, the two drugs – both GLP-1 agonists – already come with a warning about the potential for these adverse effects on the branded versions approved for weight loss, Wegovy and Saxenda. (Years earlier, both drugs, marketed as Ozempic and Victoza, were also approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes.)

Of more than 1,200 reports of adverse reactions with semaglutide, 60 cases of suicidal ideation and 7 suicide attempts have been reported since 2018, according to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) public database. For liraglutide, there were 71 cases of suicidal ideation, 28 suicide attempts, and 25 completed suicides out of more than 35,000 reports of adverse reactions.

The FAERS website cautions users that the data may be duplicated or incomplete, that rates of occurrence cannot be established using the data, that reports have not been verified, and that the existence of a report cannot establish causation.

The EMA is looking into about 150 reports of possible cases of self-injury and suicidal thoughts, according to a press release from the agency.

“It is not yet clear whether the reported cases are linked to the medicines themselves or to the patients’ underlying conditions or other factors,” it says. The medicines are widely used in the European Union, according to the press release.

The review of Ozempic, Saxenda, and Wegovy, which started on July 3, 2023, has been extended to include other GLP-1 receptor agonists, which include dulaglutide, exenatide, and lixisenatide. This review is expected to conclude in November 2023.

In a statement, Novo Nordisk did not directly dispute a potential link between the drugs and suicidal ideation.

“In the U.S., FDA requires medications for chronic weight management that work on the central nervous system, including Wegovy and Saxenda, to carry a warning about suicidal behavior and ideation,” the statement indicates. “This event had been reported in clinical trials with other weight management products.”

It adds: “Novo Nordisk is continuously performing surveillance of the data from ongoing clinical trials and real-world use of its products and collaborates closely with the authorities to ensure patient safety and adequate information to healthcare professionals.”

Important to know the denominator

“What’s important to know is the denominator,” said Holly Lofton, MD, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine and the director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone, New York. “It needs a denominator with the total population on the medication so we can determine if that’s really a significant risk.”

Dr. Lofton described an isolated, anecdotal case of a patient who had no history of depression or mental health problems but developed suicidal thoughts after taking Saxenda for several months. In that case, the 25-year-old was experiencing problems in a personal relationship and with social media.

Two other weight loss specialists contacted by this news organization had not had patients who had experienced suicidal ideation with the drugs. “These are not very common in practice,” Dr. Lofton said in an interview.

The U.S. prescribing information for Saxenda, which contains liraglutide and has been approved as an adjunct to diet and exercise for chronic weight management, recommends monitoring for the emergence of depression and suicidal thoughts. In the clinical trials, 6 of the 3,384 patients who took the drug reported suicidal ideation; none of the 1,941 patients who received placebo did so, according to the FDA.

Similarly, the U.S. prescribing information for Wegovy, which contains semaglutide, recommends monitoring for the emergence of suicidal thoughts or depression, but this recommendation was based on clinical trials of other weight management products. The prescribing information for Ozempic, the brand name for semaglutide for type 2 diabetes, does not include this recommendation.

Is it the weight loss, rather than the meds? Seen with bariatric surgery too

Speculating what the link, if any, might be, Dr. Lofton suggested dopamine release could be playing a role. Small trials in humans as well as animal studies hint at a blunting of dopamine responses to usual triggers – including addictive substances and possibly food – that may also affect mood.

Young people (aged 18-34) who undergo bariatric surgery are at an increased risk of suicide during follow-up compared to their peers who don’t have surgery. And a study found an increase in events involving self-harm after bariatric surgery, especially among patients who already had a mental health disorder.

For a patient who derives comfort from food, not being able to eat in response to a stressful event may lead that patient to act out in more serious ways, according to Dr. Lofton. “That’s why, again, surgical follow-up is so important and their presurgical psychiatric evaluation is so important.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Following reports that the European Medicines Agency is looking into instances of suicide or self-harm after patients took the weight loss drugs semaglutide or liraglutide, the manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, issued a statement to this news organization in which it says it “remains confident in the benefit risk profile of the products and remains committed to ensuring patient safety.”

U.S. experts say they haven’t personally seen this adverse effect in any patients except for one isolated case. An increase in suicidal ideation, particularly among younger people, has been reported following bariatric surgery for weight loss.

In the United States, the two drugs – both GLP-1 agonists – already come with a warning about the potential for these adverse effects on the branded versions approved for weight loss, Wegovy and Saxenda. (Years earlier, both drugs, marketed as Ozempic and Victoza, were also approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes.)

Of more than 1,200 reports of adverse reactions with semaglutide, 60 cases of suicidal ideation and 7 suicide attempts have been reported since 2018, according to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) public database. For liraglutide, there were 71 cases of suicidal ideation, 28 suicide attempts, and 25 completed suicides out of more than 35,000 reports of adverse reactions.

The FAERS website cautions users that the data may be duplicated or incomplete, that rates of occurrence cannot be established using the data, that reports have not been verified, and that the existence of a report cannot establish causation.

The EMA is looking into about 150 reports of possible cases of self-injury and suicidal thoughts, according to a press release from the agency.

“It is not yet clear whether the reported cases are linked to the medicines themselves or to the patients’ underlying conditions or other factors,” it says. The medicines are widely used in the European Union, according to the press release.

The review of Ozempic, Saxenda, and Wegovy, which started on July 3, 2023, has been extended to include other GLP-1 receptor agonists, which include dulaglutide, exenatide, and lixisenatide. This review is expected to conclude in November 2023.

In a statement, Novo Nordisk did not directly dispute a potential link between the drugs and suicidal ideation.

“In the U.S., FDA requires medications for chronic weight management that work on the central nervous system, including Wegovy and Saxenda, to carry a warning about suicidal behavior and ideation,” the statement indicates. “This event had been reported in clinical trials with other weight management products.”

It adds: “Novo Nordisk is continuously performing surveillance of the data from ongoing clinical trials and real-world use of its products and collaborates closely with the authorities to ensure patient safety and adequate information to healthcare professionals.”

Important to know the denominator

“What’s important to know is the denominator,” said Holly Lofton, MD, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine and the director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone, New York. “It needs a denominator with the total population on the medication so we can determine if that’s really a significant risk.”

Dr. Lofton described an isolated, anecdotal case of a patient who had no history of depression or mental health problems but developed suicidal thoughts after taking Saxenda for several months. In that case, the 25-year-old was experiencing problems in a personal relationship and with social media.

Two other weight loss specialists contacted by this news organization had not had patients who had experienced suicidal ideation with the drugs. “These are not very common in practice,” Dr. Lofton said in an interview.

The U.S. prescribing information for Saxenda, which contains liraglutide and has been approved as an adjunct to diet and exercise for chronic weight management, recommends monitoring for the emergence of depression and suicidal thoughts. In the clinical trials, 6 of the 3,384 patients who took the drug reported suicidal ideation; none of the 1,941 patients who received placebo did so, according to the FDA.

Similarly, the U.S. prescribing information for Wegovy, which contains semaglutide, recommends monitoring for the emergence of suicidal thoughts or depression, but this recommendation was based on clinical trials of other weight management products. The prescribing information for Ozempic, the brand name for semaglutide for type 2 diabetes, does not include this recommendation.

Is it the weight loss, rather than the meds? Seen with bariatric surgery too

Speculating what the link, if any, might be, Dr. Lofton suggested dopamine release could be playing a role. Small trials in humans as well as animal studies hint at a blunting of dopamine responses to usual triggers – including addictive substances and possibly food – that may also affect mood.

Young people (aged 18-34) who undergo bariatric surgery are at an increased risk of suicide during follow-up compared to their peers who don’t have surgery. And a study found an increase in events involving self-harm after bariatric surgery, especially among patients who already had a mental health disorder.

For a patient who derives comfort from food, not being able to eat in response to a stressful event may lead that patient to act out in more serious ways, according to Dr. Lofton. “That’s why, again, surgical follow-up is so important and their presurgical psychiatric evaluation is so important.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Following reports that the European Medicines Agency is looking into instances of suicide or self-harm after patients took the weight loss drugs semaglutide or liraglutide, the manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, issued a statement to this news organization in which it says it “remains confident in the benefit risk profile of the products and remains committed to ensuring patient safety.”

U.S. experts say they haven’t personally seen this adverse effect in any patients except for one isolated case. An increase in suicidal ideation, particularly among younger people, has been reported following bariatric surgery for weight loss.

In the United States, the two drugs – both GLP-1 agonists – already come with a warning about the potential for these adverse effects on the branded versions approved for weight loss, Wegovy and Saxenda. (Years earlier, both drugs, marketed as Ozempic and Victoza, were also approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes.)

Of more than 1,200 reports of adverse reactions with semaglutide, 60 cases of suicidal ideation and 7 suicide attempts have been reported since 2018, according to the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) public database. For liraglutide, there were 71 cases of suicidal ideation, 28 suicide attempts, and 25 completed suicides out of more than 35,000 reports of adverse reactions.

The FAERS website cautions users that the data may be duplicated or incomplete, that rates of occurrence cannot be established using the data, that reports have not been verified, and that the existence of a report cannot establish causation.

The EMA is looking into about 150 reports of possible cases of self-injury and suicidal thoughts, according to a press release from the agency.

“It is not yet clear whether the reported cases are linked to the medicines themselves or to the patients’ underlying conditions or other factors,” it says. The medicines are widely used in the European Union, according to the press release.

The review of Ozempic, Saxenda, and Wegovy, which started on July 3, 2023, has been extended to include other GLP-1 receptor agonists, which include dulaglutide, exenatide, and lixisenatide. This review is expected to conclude in November 2023.

In a statement, Novo Nordisk did not directly dispute a potential link between the drugs and suicidal ideation.

“In the U.S., FDA requires medications for chronic weight management that work on the central nervous system, including Wegovy and Saxenda, to carry a warning about suicidal behavior and ideation,” the statement indicates. “This event had been reported in clinical trials with other weight management products.”

It adds: “Novo Nordisk is continuously performing surveillance of the data from ongoing clinical trials and real-world use of its products and collaborates closely with the authorities to ensure patient safety and adequate information to healthcare professionals.”

Important to know the denominator

“What’s important to know is the denominator,” said Holly Lofton, MD, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine and the director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone, New York. “It needs a denominator with the total population on the medication so we can determine if that’s really a significant risk.”

Dr. Lofton described an isolated, anecdotal case of a patient who had no history of depression or mental health problems but developed suicidal thoughts after taking Saxenda for several months. In that case, the 25-year-old was experiencing problems in a personal relationship and with social media.

Two other weight loss specialists contacted by this news organization had not had patients who had experienced suicidal ideation with the drugs. “These are not very common in practice,” Dr. Lofton said in an interview.

The U.S. prescribing information for Saxenda, which contains liraglutide and has been approved as an adjunct to diet and exercise for chronic weight management, recommends monitoring for the emergence of depression and suicidal thoughts. In the clinical trials, 6 of the 3,384 patients who took the drug reported suicidal ideation; none of the 1,941 patients who received placebo did so, according to the FDA.

Similarly, the U.S. prescribing information for Wegovy, which contains semaglutide, recommends monitoring for the emergence of suicidal thoughts or depression, but this recommendation was based on clinical trials of other weight management products. The prescribing information for Ozempic, the brand name for semaglutide for type 2 diabetes, does not include this recommendation.

Is it the weight loss, rather than the meds? Seen with bariatric surgery too

Speculating what the link, if any, might be, Dr. Lofton suggested dopamine release could be playing a role. Small trials in humans as well as animal studies hint at a blunting of dopamine responses to usual triggers – including addictive substances and possibly food – that may also affect mood.

Young people (aged 18-34) who undergo bariatric surgery are at an increased risk of suicide during follow-up compared to their peers who don’t have surgery. And a study found an increase in events involving self-harm after bariatric surgery, especially among patients who already had a mental health disorder.

For a patient who derives comfort from food, not being able to eat in response to a stressful event may lead that patient to act out in more serious ways, according to Dr. Lofton. “That’s why, again, surgical follow-up is so important and their presurgical psychiatric evaluation is so important.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA clears the Tandem Mobi insulin pump

The product is half the size of the company’s t:slim X2 and is now the smallest of the commercially available durable tubed pumps. It is fully controllable from a mobile app through a user’s compatible iPhone.

Features of the Mobi include a 200-unit insulin cartridge and an on-pump button that can be used instead of the phone for bolusing insulin. The device can be clipped to clothing or worn on-body with an adhesive sleeve that is sold separately.

The Mobi is compatible with all existing Tandem-branded infusion sets manufactured by the Convatec Group, and there is a new 5-inch tubing option made just for the Tandem Mobi.

The Mobi is part of a hybrid-closed loop automated delivery system, along with the current Control-IQ technology and a compatible continuous glucose monitor (CGM). The CGM sensor predicts glucose values 30 minutes ahead and adjusts insulin delivery every 5 minutes to prevent highs and lows. Users must still manually bolus for meals. The system can deliver automatic correction boluses for up to 1 hour to prevent hyperglycemia.

Limited release of the Tandem Mobi is expected in late 2023, followed by full commercial availability in early 2024.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The product is half the size of the company’s t:slim X2 and is now the smallest of the commercially available durable tubed pumps. It is fully controllable from a mobile app through a user’s compatible iPhone.

Features of the Mobi include a 200-unit insulin cartridge and an on-pump button that can be used instead of the phone for bolusing insulin. The device can be clipped to clothing or worn on-body with an adhesive sleeve that is sold separately.

The Mobi is compatible with all existing Tandem-branded infusion sets manufactured by the Convatec Group, and there is a new 5-inch tubing option made just for the Tandem Mobi.

The Mobi is part of a hybrid-closed loop automated delivery system, along with the current Control-IQ technology and a compatible continuous glucose monitor (CGM). The CGM sensor predicts glucose values 30 minutes ahead and adjusts insulin delivery every 5 minutes to prevent highs and lows. Users must still manually bolus for meals. The system can deliver automatic correction boluses for up to 1 hour to prevent hyperglycemia.

Limited release of the Tandem Mobi is expected in late 2023, followed by full commercial availability in early 2024.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The product is half the size of the company’s t:slim X2 and is now the smallest of the commercially available durable tubed pumps. It is fully controllable from a mobile app through a user’s compatible iPhone.

Features of the Mobi include a 200-unit insulin cartridge and an on-pump button that can be used instead of the phone for bolusing insulin. The device can be clipped to clothing or worn on-body with an adhesive sleeve that is sold separately.

The Mobi is compatible with all existing Tandem-branded infusion sets manufactured by the Convatec Group, and there is a new 5-inch tubing option made just for the Tandem Mobi.

The Mobi is part of a hybrid-closed loop automated delivery system, along with the current Control-IQ technology and a compatible continuous glucose monitor (CGM). The CGM sensor predicts glucose values 30 minutes ahead and adjusts insulin delivery every 5 minutes to prevent highs and lows. Users must still manually bolus for meals. The system can deliver automatic correction boluses for up to 1 hour to prevent hyperglycemia.

Limited release of the Tandem Mobi is expected in late 2023, followed by full commercial availability in early 2024.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Genital Ulcerations With Swelling

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

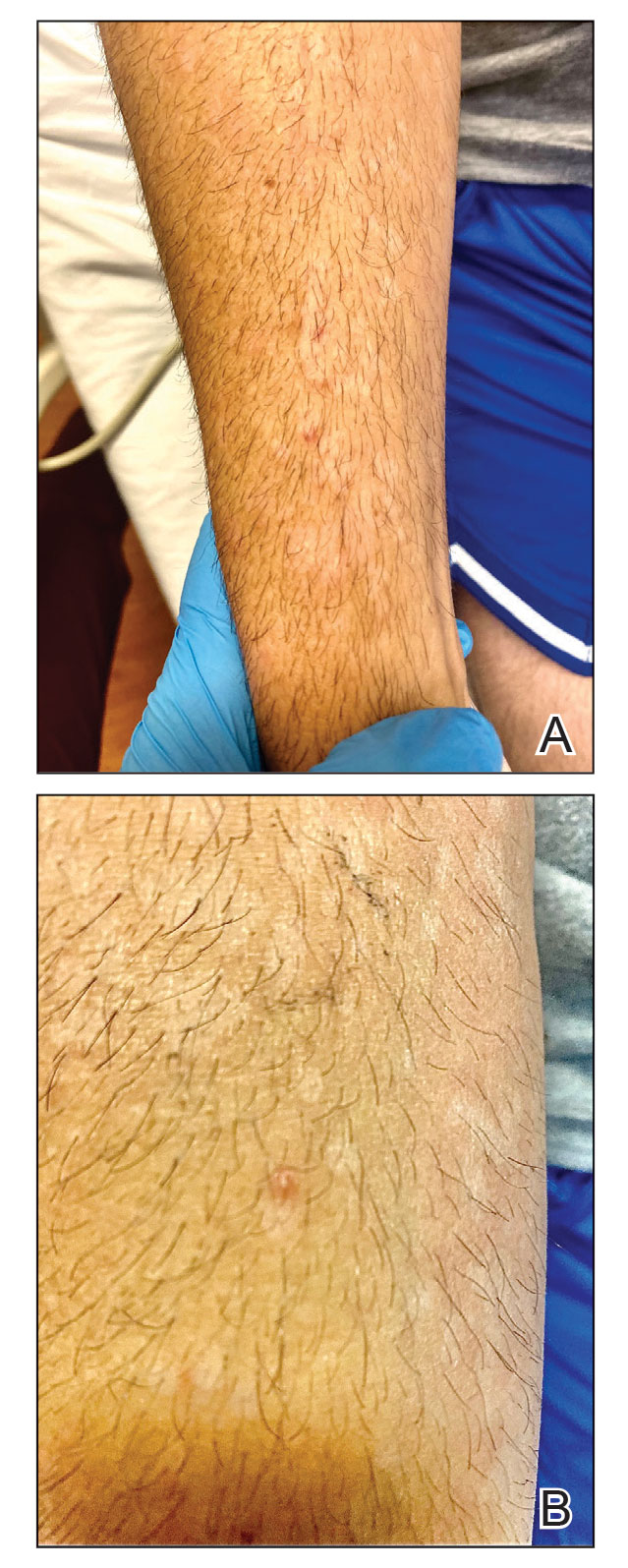

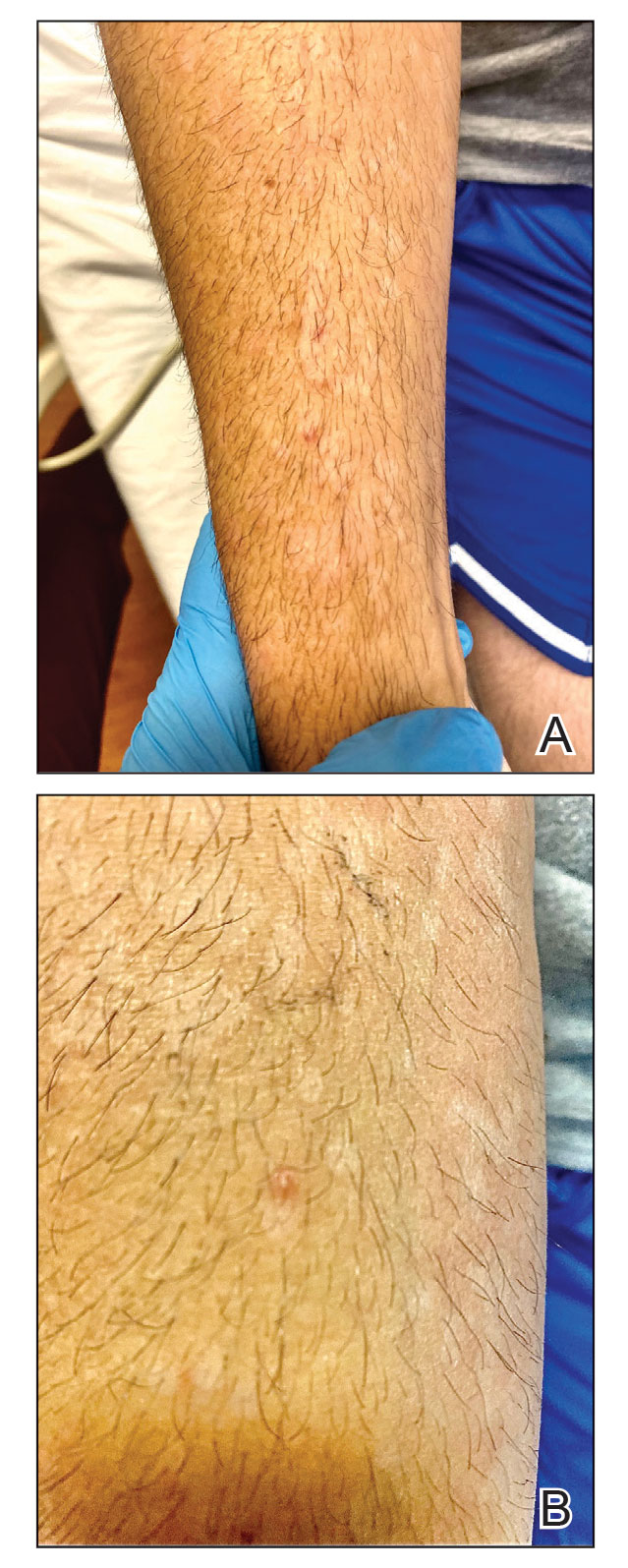

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

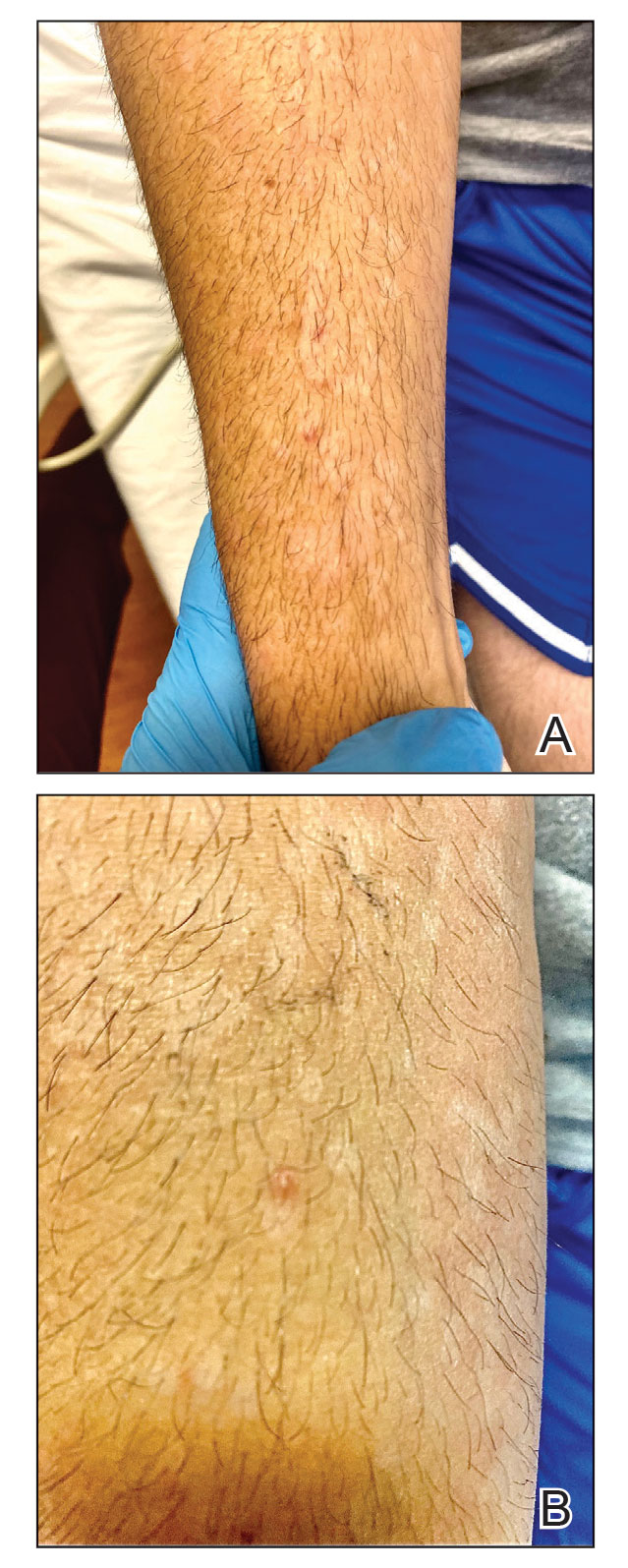

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1