User login

A decade after first DAA, only one in three are HCV free

In the decade since safe, curative oral treatments were approved for treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, only one in three U.S. patients diagnosed with the disease have been cleared of it, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings indicate that current progress falls far short of the goal of the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States, which calls for eliminating HCV for at least 80% of patients with the virus by 2030.

Lead author Carolyn Wester, MD, with the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, called the low numbers “stunning” and said that the researchers found that patients face barriers to being cured at every step of the way, from being diagnosed to accessing breakthrough direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents.

The article was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Outcomes vary by age and insurance

Using longitudinal data from Quest Diagnostics laboratories, the researchers identified 1.7 million people who had a history of HCV infection from Jan. 1, 2013, to Dec. 31, 2022.

Of those patients, 1.5 million (88%) were categorized as having undergone viral testing.

Among those who underwent such testing, 1 million (69%) were categorized as having an initial infection. Just 356,807 patients with initial infection (34%) were cured or cleared of HCV. Of those found to be cured or cleared, 23,518 (7%) were found to have persistent infection or reinfection.

Viral clearance varied greatly by insurance. While 45% of the people covered under Medicare experienced viral clearance, only 23% of the uninsured and 31% of those on Medicaid did so.

Age also played a role in viral clearance. It was highest (42%) among those aged 60 and older. Clearance was lowest (24%) among patients in the 20-39 age group, the group most likely to be newly infected in light of the surge in HCV cases because of the opioid epidemic, Dr. Wester said. Persistent infection or reinfection was also highest in the 20-39 age group.

With respect to age and insurance type combined, the highest HCV clearance rate (49%) was for patients aged 60 and older who had commercial insurance; the lowest (16%) was for uninsured patients in the 20-39 age group.

The investigators evaluated people who had been diagnosed with HCV, Dr. Wester said. “It’s estimated about 40% of people in the U.S. are unaware of their infection.” Because of this, the numbers reported in the study may vastly underestimate the true picture, she told this news organization.

Barriers to treatment ‘insurmountable’ without major transformation

Increased access to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention services for persons with or at risk for acquiring hepatitis C needs to be addressed to prevent progression of disease and ongoing transmission and to achieve national hepatitis C elimination goals, the authors wrote.

The biggest barriers to improving HCV clearance are the high cost of treatment, widely varying insurance coverage, insurer restrictions, and challenges in diagnosing the disease, Dr. Wester added.

Overcoming these barriers requires implementation of universal HCV screening recommendations, including HCV RNA testing for all persons with reactive HCV antibody results, provision of treatment for all persons regardless of payer, and prevention services for persons at risk for acquiring new HCV infection, the authors concluded.

“The current barriers are insurmountable without a major transformation in our nation’s response,” Dr. Wester noted.

She expressed her support of the National Hepatitis C Elimination Program, offered as part of the Biden Administration’s 2024 budget proposal. She said that the initiative “is what we need to prevent the needless suffering from hepatitis C and to potentially save not only tens of thousands of lives but tens of billions of health care dollars.”

The three-part proposal includes a national subscription model to purchase DAA agents for those most underserved: Medicaid beneficiaries, incarcerated people, the uninsured, and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals treated through the Indian Health Service.

Under this model, the federal government would negotiate with manufacturers to buy as much treatment as needed for all individuals in the underserved groups.

What can physicians do?

Physicians can help improve HCV treatment and outcomes by being aware of the current testing guidelines, Dr. Wester said.

Guidelines now call for hepatitis C screening at least once in a lifetime for all adults, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection is less than 0.1%. They also call for screening during each pregnancy, with the same regional-prevalence exception.

Recommendations include curative treatment “for nearly everybody who is living with hepatitis C,” Dr. Wester added.

These CDC guidelines came out in April 2020, a time when the medical focus shifted to COVID-19, and that may have hurt awareness, she noted.

Physicians can also help by fighting back against non–evidence-based reasons insurance companies give for restricting coverage, Dr. Wester said.

Those restrictions include requiring specialists to prescribe DAA agents instead of allowing primary care physicians to do so, as well as requiring patients to have advanced liver disease or requiring patients to demonstrate sobriety or prove they are receiving counseling prior to their being eligible for treatment, Dr. Wester said.

Prior authorization a problem

Stacey B. Trooskin MD, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told this news organization that prior authorization has been a major barrier for obtaining medications. Prior authorization requirements differ by state.

The paperwork must be submitted by already-stretched physician offices, and appeals are common. In that time, the window for keeping patients with HCV in the health care system may be lost, said Dr. Trooskin, chief medical adviser to the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable.

“We know that about half of all Medicaid programs have removed prior authorization for most patients entirely,” she said, “but there are still half that require prior authorization.”

Action at the federal level is also needed, Dr. Trooskin said.

The countries that are successfully eliminating HCV and have successfully deployed the lifesaving medications provide governmental support for meeting patients where they are, she added.

Support can include inpatient and outpatient substance use disorder treatment programs or support in mental health settings, she noted.

“It’s not enough to want patients to come into their primary care provider and for that primary care provider to screen them,” Dr. Trooskin said. “This is about creating health care infrastructure so that we are finding patients at greatest risk for hepatitis C and integrating hepatitis C treatment into the services they are already accessing.”

Coauthor Harvey W. Kaufman, MD, is an employee of and owns stock in Quest Diagnostics. Coauthor William A. Meyer III, PhD, is a consultant to Quest Diagnostics. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed. Dr. Trooskin oversees C-Change, a hepatitis C elimination program, which receives funding from Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the decade since safe, curative oral treatments were approved for treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, only one in three U.S. patients diagnosed with the disease have been cleared of it, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings indicate that current progress falls far short of the goal of the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States, which calls for eliminating HCV for at least 80% of patients with the virus by 2030.

Lead author Carolyn Wester, MD, with the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, called the low numbers “stunning” and said that the researchers found that patients face barriers to being cured at every step of the way, from being diagnosed to accessing breakthrough direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents.

The article was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Outcomes vary by age and insurance

Using longitudinal data from Quest Diagnostics laboratories, the researchers identified 1.7 million people who had a history of HCV infection from Jan. 1, 2013, to Dec. 31, 2022.

Of those patients, 1.5 million (88%) were categorized as having undergone viral testing.

Among those who underwent such testing, 1 million (69%) were categorized as having an initial infection. Just 356,807 patients with initial infection (34%) were cured or cleared of HCV. Of those found to be cured or cleared, 23,518 (7%) were found to have persistent infection or reinfection.

Viral clearance varied greatly by insurance. While 45% of the people covered under Medicare experienced viral clearance, only 23% of the uninsured and 31% of those on Medicaid did so.

Age also played a role in viral clearance. It was highest (42%) among those aged 60 and older. Clearance was lowest (24%) among patients in the 20-39 age group, the group most likely to be newly infected in light of the surge in HCV cases because of the opioid epidemic, Dr. Wester said. Persistent infection or reinfection was also highest in the 20-39 age group.

With respect to age and insurance type combined, the highest HCV clearance rate (49%) was for patients aged 60 and older who had commercial insurance; the lowest (16%) was for uninsured patients in the 20-39 age group.

The investigators evaluated people who had been diagnosed with HCV, Dr. Wester said. “It’s estimated about 40% of people in the U.S. are unaware of their infection.” Because of this, the numbers reported in the study may vastly underestimate the true picture, she told this news organization.

Barriers to treatment ‘insurmountable’ without major transformation

Increased access to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention services for persons with or at risk for acquiring hepatitis C needs to be addressed to prevent progression of disease and ongoing transmission and to achieve national hepatitis C elimination goals, the authors wrote.

The biggest barriers to improving HCV clearance are the high cost of treatment, widely varying insurance coverage, insurer restrictions, and challenges in diagnosing the disease, Dr. Wester added.

Overcoming these barriers requires implementation of universal HCV screening recommendations, including HCV RNA testing for all persons with reactive HCV antibody results, provision of treatment for all persons regardless of payer, and prevention services for persons at risk for acquiring new HCV infection, the authors concluded.

“The current barriers are insurmountable without a major transformation in our nation’s response,” Dr. Wester noted.

She expressed her support of the National Hepatitis C Elimination Program, offered as part of the Biden Administration’s 2024 budget proposal. She said that the initiative “is what we need to prevent the needless suffering from hepatitis C and to potentially save not only tens of thousands of lives but tens of billions of health care dollars.”

The three-part proposal includes a national subscription model to purchase DAA agents for those most underserved: Medicaid beneficiaries, incarcerated people, the uninsured, and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals treated through the Indian Health Service.

Under this model, the federal government would negotiate with manufacturers to buy as much treatment as needed for all individuals in the underserved groups.

What can physicians do?

Physicians can help improve HCV treatment and outcomes by being aware of the current testing guidelines, Dr. Wester said.

Guidelines now call for hepatitis C screening at least once in a lifetime for all adults, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection is less than 0.1%. They also call for screening during each pregnancy, with the same regional-prevalence exception.

Recommendations include curative treatment “for nearly everybody who is living with hepatitis C,” Dr. Wester added.

These CDC guidelines came out in April 2020, a time when the medical focus shifted to COVID-19, and that may have hurt awareness, she noted.

Physicians can also help by fighting back against non–evidence-based reasons insurance companies give for restricting coverage, Dr. Wester said.

Those restrictions include requiring specialists to prescribe DAA agents instead of allowing primary care physicians to do so, as well as requiring patients to have advanced liver disease or requiring patients to demonstrate sobriety or prove they are receiving counseling prior to their being eligible for treatment, Dr. Wester said.

Prior authorization a problem

Stacey B. Trooskin MD, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told this news organization that prior authorization has been a major barrier for obtaining medications. Prior authorization requirements differ by state.

The paperwork must be submitted by already-stretched physician offices, and appeals are common. In that time, the window for keeping patients with HCV in the health care system may be lost, said Dr. Trooskin, chief medical adviser to the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable.

“We know that about half of all Medicaid programs have removed prior authorization for most patients entirely,” she said, “but there are still half that require prior authorization.”

Action at the federal level is also needed, Dr. Trooskin said.

The countries that are successfully eliminating HCV and have successfully deployed the lifesaving medications provide governmental support for meeting patients where they are, she added.

Support can include inpatient and outpatient substance use disorder treatment programs or support in mental health settings, she noted.

“It’s not enough to want patients to come into their primary care provider and for that primary care provider to screen them,” Dr. Trooskin said. “This is about creating health care infrastructure so that we are finding patients at greatest risk for hepatitis C and integrating hepatitis C treatment into the services they are already accessing.”

Coauthor Harvey W. Kaufman, MD, is an employee of and owns stock in Quest Diagnostics. Coauthor William A. Meyer III, PhD, is a consultant to Quest Diagnostics. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed. Dr. Trooskin oversees C-Change, a hepatitis C elimination program, which receives funding from Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the decade since safe, curative oral treatments were approved for treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, only one in three U.S. patients diagnosed with the disease have been cleared of it, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings indicate that current progress falls far short of the goal of the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States, which calls for eliminating HCV for at least 80% of patients with the virus by 2030.

Lead author Carolyn Wester, MD, with the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, called the low numbers “stunning” and said that the researchers found that patients face barriers to being cured at every step of the way, from being diagnosed to accessing breakthrough direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents.

The article was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Outcomes vary by age and insurance

Using longitudinal data from Quest Diagnostics laboratories, the researchers identified 1.7 million people who had a history of HCV infection from Jan. 1, 2013, to Dec. 31, 2022.

Of those patients, 1.5 million (88%) were categorized as having undergone viral testing.

Among those who underwent such testing, 1 million (69%) were categorized as having an initial infection. Just 356,807 patients with initial infection (34%) were cured or cleared of HCV. Of those found to be cured or cleared, 23,518 (7%) were found to have persistent infection or reinfection.

Viral clearance varied greatly by insurance. While 45% of the people covered under Medicare experienced viral clearance, only 23% of the uninsured and 31% of those on Medicaid did so.

Age also played a role in viral clearance. It was highest (42%) among those aged 60 and older. Clearance was lowest (24%) among patients in the 20-39 age group, the group most likely to be newly infected in light of the surge in HCV cases because of the opioid epidemic, Dr. Wester said. Persistent infection or reinfection was also highest in the 20-39 age group.

With respect to age and insurance type combined, the highest HCV clearance rate (49%) was for patients aged 60 and older who had commercial insurance; the lowest (16%) was for uninsured patients in the 20-39 age group.

The investigators evaluated people who had been diagnosed with HCV, Dr. Wester said. “It’s estimated about 40% of people in the U.S. are unaware of their infection.” Because of this, the numbers reported in the study may vastly underestimate the true picture, she told this news organization.

Barriers to treatment ‘insurmountable’ without major transformation

Increased access to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention services for persons with or at risk for acquiring hepatitis C needs to be addressed to prevent progression of disease and ongoing transmission and to achieve national hepatitis C elimination goals, the authors wrote.

The biggest barriers to improving HCV clearance are the high cost of treatment, widely varying insurance coverage, insurer restrictions, and challenges in diagnosing the disease, Dr. Wester added.

Overcoming these barriers requires implementation of universal HCV screening recommendations, including HCV RNA testing for all persons with reactive HCV antibody results, provision of treatment for all persons regardless of payer, and prevention services for persons at risk for acquiring new HCV infection, the authors concluded.

“The current barriers are insurmountable without a major transformation in our nation’s response,” Dr. Wester noted.

She expressed her support of the National Hepatitis C Elimination Program, offered as part of the Biden Administration’s 2024 budget proposal. She said that the initiative “is what we need to prevent the needless suffering from hepatitis C and to potentially save not only tens of thousands of lives but tens of billions of health care dollars.”

The three-part proposal includes a national subscription model to purchase DAA agents for those most underserved: Medicaid beneficiaries, incarcerated people, the uninsured, and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals treated through the Indian Health Service.

Under this model, the federal government would negotiate with manufacturers to buy as much treatment as needed for all individuals in the underserved groups.

What can physicians do?

Physicians can help improve HCV treatment and outcomes by being aware of the current testing guidelines, Dr. Wester said.

Guidelines now call for hepatitis C screening at least once in a lifetime for all adults, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection is less than 0.1%. They also call for screening during each pregnancy, with the same regional-prevalence exception.

Recommendations include curative treatment “for nearly everybody who is living with hepatitis C,” Dr. Wester added.

These CDC guidelines came out in April 2020, a time when the medical focus shifted to COVID-19, and that may have hurt awareness, she noted.

Physicians can also help by fighting back against non–evidence-based reasons insurance companies give for restricting coverage, Dr. Wester said.

Those restrictions include requiring specialists to prescribe DAA agents instead of allowing primary care physicians to do so, as well as requiring patients to have advanced liver disease or requiring patients to demonstrate sobriety or prove they are receiving counseling prior to their being eligible for treatment, Dr. Wester said.

Prior authorization a problem

Stacey B. Trooskin MD, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told this news organization that prior authorization has been a major barrier for obtaining medications. Prior authorization requirements differ by state.

The paperwork must be submitted by already-stretched physician offices, and appeals are common. In that time, the window for keeping patients with HCV in the health care system may be lost, said Dr. Trooskin, chief medical adviser to the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable.

“We know that about half of all Medicaid programs have removed prior authorization for most patients entirely,” she said, “but there are still half that require prior authorization.”

Action at the federal level is also needed, Dr. Trooskin said.

The countries that are successfully eliminating HCV and have successfully deployed the lifesaving medications provide governmental support for meeting patients where they are, she added.

Support can include inpatient and outpatient substance use disorder treatment programs or support in mental health settings, she noted.

“It’s not enough to want patients to come into their primary care provider and for that primary care provider to screen them,” Dr. Trooskin said. “This is about creating health care infrastructure so that we are finding patients at greatest risk for hepatitis C and integrating hepatitis C treatment into the services they are already accessing.”

Coauthor Harvey W. Kaufman, MD, is an employee of and owns stock in Quest Diagnostics. Coauthor William A. Meyer III, PhD, is a consultant to Quest Diagnostics. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed. Dr. Trooskin oversees C-Change, a hepatitis C elimination program, which receives funding from Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hearing loss tied to more fatigue in middle and older age

Like many stressful chronic conditions, hearing loss appears to foster fatigue, according to an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Study data published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined NHANES data from 2015 to 2016 and 2017 to 2018, including findings on more than 3,000 participants aged 40 and older. Based on the audiometry subset of NHANES data, hearing loss was associated with a higher frequency of fatigue – even after adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, and lifestyle variables such as smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, in a nationally representative sample of adults in middle and older age.

“We wanted to get away from small clinical data and take a look at the population level to see if hearing loss was related to fatigue and, further perhaps, to cognitive decline,” said coauthor Nicholas S. Reed, AuD, PhD, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “We found people with hearing loss had twice the risk of reporting fatigue nearly every day versus those not reporting fatigue.” This cross-sectional study provides needed population-based evidence from a nationally representative sample, according to Dr. Reed and associates, who have been researching the possible connection between age-related hearing loss, physical activity levels, and cognitive decline.

Study details

The 3,031 age-eligible participants had a mean age of 58 years; 48% were male, and 10% were Black. Some hearing loss was reported by 24%.

They responded to the following question: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling tired or having little energy?” Response categories were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.” Those with hearing loss were more likely to report fatigue for more than half the days (relative risk ratio, 2.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.27-3.67) and nearly every day (RRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.16-3.65), compared with not having fatigue. Additional adjustment for comorbidities and depressive symptoms showed similar results.

Hearing loss was defined as > 25 decibels hearing level (dB HL) versus normal hearing of ≤ 25 dB HL, and continuously by every 10 dB HL poorer. Each 10-dB HL of audiometric hearing loss was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting fatigue nearly every day (RRR, 1.24; 95% CI,1.04-1.47), but not for more than half the days.

The association tended to be stronger in younger, non-Hispanic White, and female participants, but statistical testing did not support differential associations by age, sex, race, or ethnicity.

While some might intuitively expect hearing loss to cause noticeably more fatigue in middle-aged people who may be straining to hear during hours in the daily workplace or at home, Dr. Reed said older people probably feel more hearing-related fatigue owing to age and comorbidities. “And higher physical activity levels of middle-aged adults can be protective.”

Dr. Reed advised primary care physicians to be sure to ask about fatigue and hearing status during wellness exams and take appropriate steps to diagnose and correct hearing problems. “Make sure hearing is part of the health equation because hearing loss can be part of the culprit. And it’s very possible that hearing loss is also contributing to cognitive decline.”

Dr. Reed’s group will soon release data on a clinical trial on hearing loss and cognitive decline.

The authors called for studies incorporating fatigue assessments in order to clarify how hearing loss might contribute to physical and mental fatigue and how it could be associated with downstream outcomes such as fatigue-related physical impairment. Dr. Reed reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and stock compensation from the Neosensory Advisory Board outside of the submitted work. Several coauthors reported academic or government research funding as well as fees and honoraria from various private-sector companies.

Like many stressful chronic conditions, hearing loss appears to foster fatigue, according to an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Study data published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined NHANES data from 2015 to 2016 and 2017 to 2018, including findings on more than 3,000 participants aged 40 and older. Based on the audiometry subset of NHANES data, hearing loss was associated with a higher frequency of fatigue – even after adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, and lifestyle variables such as smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, in a nationally representative sample of adults in middle and older age.

“We wanted to get away from small clinical data and take a look at the population level to see if hearing loss was related to fatigue and, further perhaps, to cognitive decline,” said coauthor Nicholas S. Reed, AuD, PhD, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “We found people with hearing loss had twice the risk of reporting fatigue nearly every day versus those not reporting fatigue.” This cross-sectional study provides needed population-based evidence from a nationally representative sample, according to Dr. Reed and associates, who have been researching the possible connection between age-related hearing loss, physical activity levels, and cognitive decline.

Study details

The 3,031 age-eligible participants had a mean age of 58 years; 48% were male, and 10% were Black. Some hearing loss was reported by 24%.

They responded to the following question: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling tired or having little energy?” Response categories were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.” Those with hearing loss were more likely to report fatigue for more than half the days (relative risk ratio, 2.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.27-3.67) and nearly every day (RRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.16-3.65), compared with not having fatigue. Additional adjustment for comorbidities and depressive symptoms showed similar results.

Hearing loss was defined as > 25 decibels hearing level (dB HL) versus normal hearing of ≤ 25 dB HL, and continuously by every 10 dB HL poorer. Each 10-dB HL of audiometric hearing loss was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting fatigue nearly every day (RRR, 1.24; 95% CI,1.04-1.47), but not for more than half the days.

The association tended to be stronger in younger, non-Hispanic White, and female participants, but statistical testing did not support differential associations by age, sex, race, or ethnicity.

While some might intuitively expect hearing loss to cause noticeably more fatigue in middle-aged people who may be straining to hear during hours in the daily workplace or at home, Dr. Reed said older people probably feel more hearing-related fatigue owing to age and comorbidities. “And higher physical activity levels of middle-aged adults can be protective.”

Dr. Reed advised primary care physicians to be sure to ask about fatigue and hearing status during wellness exams and take appropriate steps to diagnose and correct hearing problems. “Make sure hearing is part of the health equation because hearing loss can be part of the culprit. And it’s very possible that hearing loss is also contributing to cognitive decline.”

Dr. Reed’s group will soon release data on a clinical trial on hearing loss and cognitive decline.

The authors called for studies incorporating fatigue assessments in order to clarify how hearing loss might contribute to physical and mental fatigue and how it could be associated with downstream outcomes such as fatigue-related physical impairment. Dr. Reed reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and stock compensation from the Neosensory Advisory Board outside of the submitted work. Several coauthors reported academic or government research funding as well as fees and honoraria from various private-sector companies.

Like many stressful chronic conditions, hearing loss appears to foster fatigue, according to an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Study data published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined NHANES data from 2015 to 2016 and 2017 to 2018, including findings on more than 3,000 participants aged 40 and older. Based on the audiometry subset of NHANES data, hearing loss was associated with a higher frequency of fatigue – even after adjustment for demographics, comorbidities, and lifestyle variables such as smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, in a nationally representative sample of adults in middle and older age.

“We wanted to get away from small clinical data and take a look at the population level to see if hearing loss was related to fatigue and, further perhaps, to cognitive decline,” said coauthor Nicholas S. Reed, AuD, PhD, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “We found people with hearing loss had twice the risk of reporting fatigue nearly every day versus those not reporting fatigue.” This cross-sectional study provides needed population-based evidence from a nationally representative sample, according to Dr. Reed and associates, who have been researching the possible connection between age-related hearing loss, physical activity levels, and cognitive decline.

Study details

The 3,031 age-eligible participants had a mean age of 58 years; 48% were male, and 10% were Black. Some hearing loss was reported by 24%.

They responded to the following question: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling tired or having little energy?” Response categories were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.” Those with hearing loss were more likely to report fatigue for more than half the days (relative risk ratio, 2.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.27-3.67) and nearly every day (RRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.16-3.65), compared with not having fatigue. Additional adjustment for comorbidities and depressive symptoms showed similar results.

Hearing loss was defined as > 25 decibels hearing level (dB HL) versus normal hearing of ≤ 25 dB HL, and continuously by every 10 dB HL poorer. Each 10-dB HL of audiometric hearing loss was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting fatigue nearly every day (RRR, 1.24; 95% CI,1.04-1.47), but not for more than half the days.

The association tended to be stronger in younger, non-Hispanic White, and female participants, but statistical testing did not support differential associations by age, sex, race, or ethnicity.

While some might intuitively expect hearing loss to cause noticeably more fatigue in middle-aged people who may be straining to hear during hours in the daily workplace or at home, Dr. Reed said older people probably feel more hearing-related fatigue owing to age and comorbidities. “And higher physical activity levels of middle-aged adults can be protective.”

Dr. Reed advised primary care physicians to be sure to ask about fatigue and hearing status during wellness exams and take appropriate steps to diagnose and correct hearing problems. “Make sure hearing is part of the health equation because hearing loss can be part of the culprit. And it’s very possible that hearing loss is also contributing to cognitive decline.”

Dr. Reed’s group will soon release data on a clinical trial on hearing loss and cognitive decline.

The authors called for studies incorporating fatigue assessments in order to clarify how hearing loss might contribute to physical and mental fatigue and how it could be associated with downstream outcomes such as fatigue-related physical impairment. Dr. Reed reported grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and stock compensation from the Neosensory Advisory Board outside of the submitted work. Several coauthors reported academic or government research funding as well as fees and honoraria from various private-sector companies.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY – HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Clothing provides Dx clue

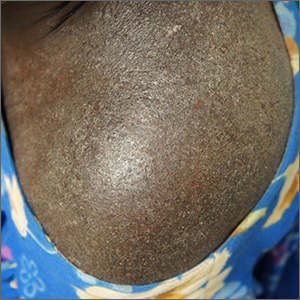

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

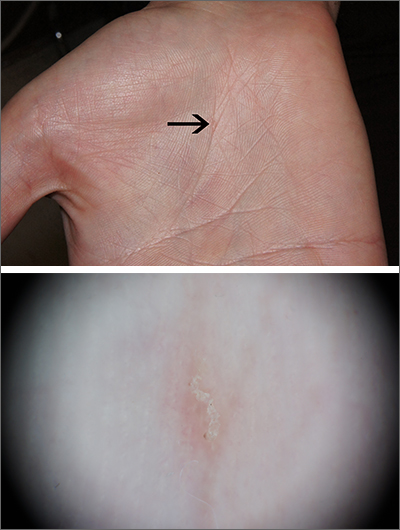

Intensely itchy normal skin

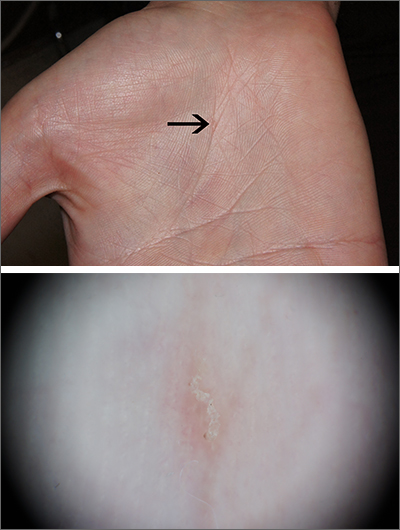

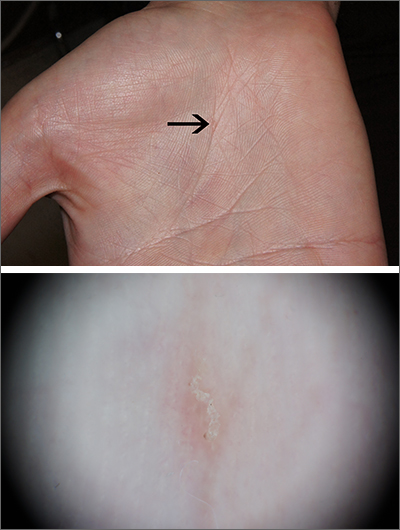

Severe itching should prompt suspicion for scabies and the hands are the highest-yield location. In this patient’s case, there weren’t findings in the web spaces and, in general, skin findings were largely absent; dermoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei, is a parasitic mite that lives and reproduces in and on human skin and is transmitted by very close contact, either skin-to-skin or by living within a household or institution with shared linens and furnishings. After infection, itching develops within days to weeks from both the physical movement and burrowing of mites within the skin and from the allergic and inflammatory response to mite bodies and their waste.1 Symptoms and infections may persist for years in the absence of treatment.

Sometimes (as in this case), burrows are few and very subtle. More often, there are widespread burrows and excoriated papules over the hands, trunk, extremities, and genitals. A burrowed mite is often adjacent to, but not directly in, an excoriation. Dermoscopy has transformed the ability to diagnose this condition quickly by enabling clinicians to visualize the triangular shape of the head and front legs of a mite (called the “delta sign”). This localization allows easy microscopic confirmation by paring the mite from the skin with a small scalpel blade. (A #11 or #15 blade works very well.)

Topical permethrin 5% cream is highly curative. The cream should be applied from the top of the neck to the tips of the patient’s toes and left on for 8 hours; the process should be repeated a week later. Very close contacts (eg, symptomatic household members or sexual partners) should be treated concurrently. A 60 g tube will treat 1 adult twice. (A 60 g tube of permethrin with a refill, therefore, will treat 2 adults twice.) Oral ivermectin 3 mg dosed at 200 mcg/kg in a single dose repeated in 1 to 2 weeks is an alternative.

Outbreaks in an institutional setting present a significant challenge and require population-based control and often the assistance of infection control specialists or local public health officials. Often this involves weekly treatment with ivermectin for all potentially affected individuals for 3 to 4 weeks and surveillance for follow-up. While there is some resistance to ivermectin, many failures relate more to reinfection from unidentified sources.

This patient received topical permethrin 5% cream dosed as noted above. Itching can be expected to persist for 3 to 4 weeks, so topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed as needed for itching on days when permethrin wasn’t applied. At 6 weeks, this patient’s symptoms had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Richards RN. Scabies: diagnostic and therapeutic update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:95-101. doi: 10.1177/1203475420960446

Severe itching should prompt suspicion for scabies and the hands are the highest-yield location. In this patient’s case, there weren’t findings in the web spaces and, in general, skin findings were largely absent; dermoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei, is a parasitic mite that lives and reproduces in and on human skin and is transmitted by very close contact, either skin-to-skin or by living within a household or institution with shared linens and furnishings. After infection, itching develops within days to weeks from both the physical movement and burrowing of mites within the skin and from the allergic and inflammatory response to mite bodies and their waste.1 Symptoms and infections may persist for years in the absence of treatment.

Sometimes (as in this case), burrows are few and very subtle. More often, there are widespread burrows and excoriated papules over the hands, trunk, extremities, and genitals. A burrowed mite is often adjacent to, but not directly in, an excoriation. Dermoscopy has transformed the ability to diagnose this condition quickly by enabling clinicians to visualize the triangular shape of the head and front legs of a mite (called the “delta sign”). This localization allows easy microscopic confirmation by paring the mite from the skin with a small scalpel blade. (A #11 or #15 blade works very well.)

Topical permethrin 5% cream is highly curative. The cream should be applied from the top of the neck to the tips of the patient’s toes and left on for 8 hours; the process should be repeated a week later. Very close contacts (eg, symptomatic household members or sexual partners) should be treated concurrently. A 60 g tube will treat 1 adult twice. (A 60 g tube of permethrin with a refill, therefore, will treat 2 adults twice.) Oral ivermectin 3 mg dosed at 200 mcg/kg in a single dose repeated in 1 to 2 weeks is an alternative.

Outbreaks in an institutional setting present a significant challenge and require population-based control and often the assistance of infection control specialists or local public health officials. Often this involves weekly treatment with ivermectin for all potentially affected individuals for 3 to 4 weeks and surveillance for follow-up. While there is some resistance to ivermectin, many failures relate more to reinfection from unidentified sources.

This patient received topical permethrin 5% cream dosed as noted above. Itching can be expected to persist for 3 to 4 weeks, so topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed as needed for itching on days when permethrin wasn’t applied. At 6 weeks, this patient’s symptoms had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Severe itching should prompt suspicion for scabies and the hands are the highest-yield location. In this patient’s case, there weren’t findings in the web spaces and, in general, skin findings were largely absent; dermoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei, is a parasitic mite that lives and reproduces in and on human skin and is transmitted by very close contact, either skin-to-skin or by living within a household or institution with shared linens and furnishings. After infection, itching develops within days to weeks from both the physical movement and burrowing of mites within the skin and from the allergic and inflammatory response to mite bodies and their waste.1 Symptoms and infections may persist for years in the absence of treatment.

Sometimes (as in this case), burrows are few and very subtle. More often, there are widespread burrows and excoriated papules over the hands, trunk, extremities, and genitals. A burrowed mite is often adjacent to, but not directly in, an excoriation. Dermoscopy has transformed the ability to diagnose this condition quickly by enabling clinicians to visualize the triangular shape of the head and front legs of a mite (called the “delta sign”). This localization allows easy microscopic confirmation by paring the mite from the skin with a small scalpel blade. (A #11 or #15 blade works very well.)

Topical permethrin 5% cream is highly curative. The cream should be applied from the top of the neck to the tips of the patient’s toes and left on for 8 hours; the process should be repeated a week later. Very close contacts (eg, symptomatic household members or sexual partners) should be treated concurrently. A 60 g tube will treat 1 adult twice. (A 60 g tube of permethrin with a refill, therefore, will treat 2 adults twice.) Oral ivermectin 3 mg dosed at 200 mcg/kg in a single dose repeated in 1 to 2 weeks is an alternative.

Outbreaks in an institutional setting present a significant challenge and require population-based control and often the assistance of infection control specialists or local public health officials. Often this involves weekly treatment with ivermectin for all potentially affected individuals for 3 to 4 weeks and surveillance for follow-up. While there is some resistance to ivermectin, many failures relate more to reinfection from unidentified sources.

This patient received topical permethrin 5% cream dosed as noted above. Itching can be expected to persist for 3 to 4 weeks, so topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed as needed for itching on days when permethrin wasn’t applied. At 6 weeks, this patient’s symptoms had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Richards RN. Scabies: diagnostic and therapeutic update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:95-101. doi: 10.1177/1203475420960446

1. Richards RN. Scabies: diagnostic and therapeutic update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:95-101. doi: 10.1177/1203475420960446

Meaningful work

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Community Access to Child Health is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Known by the acronym CATCH, this program provides seed funding to chapters and pediatricians at all stages of their training and practice trajectories to assist in the planing and development of community-based initiatives aimed at increasing children’s access to a variety of health services. While relatively modest in its scale and profile, the CATCH-funded recipients have a strong track record of creating effective and often sustainable projects serving children in historically underserved segments of the community.

In a recent article by Rupal C. Gupta, MD, FAAP, I encountered a quote attributed to Benjamin D. Hoffman, MD, president-elect of the AAP, who served as a chapter CATCH facilitator. Dr. Hoffman observed that “part of the solution to burnout is doing meaningful work, and CATCH allows you to do that.” I couldn’t agree more with Dr. Hoffman’s claim. There is no question that viewing your professional activities as meaningless can be a major contributor to burnout. And, community involvement can certainly provide ample opportunities to do meaningful work.

As a pediatrician who worked, lived, and raised his children in the same small community, I found that seeing and interacting with my patients and their families outside the office in a variety of environments, from the grocery store to the soccer field, and a variety of roles, from coach to school physician, added a richness to my professional life.

I suspect that living in and serving the community where I practiced may have helped provide some meaning on those very rare occasions when I wondered why I was heading off to work in the morning ... or in the middle of the night. But, 90% of the time I felt what I was doing as a physician was somehow making a difference. Nothing earth shaking or worthy of sainthood mind you, but if I were to take the time to look back on my day and weighed the meaningful against the meaningless activities it would almost always tip the scales toward meaningful. But, I seldom had the time to engage in such retrospection.

It seems that many physicians today are not finding that same meaningful versus meaningless balance that I enjoyed. Is it because they are spending too little of their time doing meaningful work? Has the management of the more common illnesses become too routine or so algorithm-driven that it is no longer challenging? One solution to that problem is to shift our focus from the disease to the patient. Diagnosing and managing strep throat is not a terribly challenging intellectual exercise until you realize it is the unique way in which each patient presents and tolerates the illness.

I think the answer is not that there is too little meaningful work for physicians today, and I suspect that you would agree. We are all lucky to have jobs that almost by definition offer an abundance of meaningful activities. There are situations in which it may require a bit of an attitude change to see the meaningfulness, but the opportunities are there. No, the problem seems to be that there is an overabundance of meaningless tasks that confront physicians. Clunky, time-gobbling medical record systems, fighting with insurance companies, chasing down prior authorizations, attending committee meetings in a top-heavy organization with too many meetings, _____________. You can fill in the blank with your favorite.

The CATCH program can offer you a way to rebalance that imbalance, and, by all means, consider applying for a grant. But, where we need to put our energies is in the search for solutions to the glut of meaningless tasks that are burning us out. We shouldn’t have to seek meaningful experiences outside of our offices. They have always been there, hidden under the mountain of meaningless chores.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Community Access to Child Health is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Known by the acronym CATCH, this program provides seed funding to chapters and pediatricians at all stages of their training and practice trajectories to assist in the planing and development of community-based initiatives aimed at increasing children’s access to a variety of health services. While relatively modest in its scale and profile, the CATCH-funded recipients have a strong track record of creating effective and often sustainable projects serving children in historically underserved segments of the community.

In a recent article by Rupal C. Gupta, MD, FAAP, I encountered a quote attributed to Benjamin D. Hoffman, MD, president-elect of the AAP, who served as a chapter CATCH facilitator. Dr. Hoffman observed that “part of the solution to burnout is doing meaningful work, and CATCH allows you to do that.” I couldn’t agree more with Dr. Hoffman’s claim. There is no question that viewing your professional activities as meaningless can be a major contributor to burnout. And, community involvement can certainly provide ample opportunities to do meaningful work.

As a pediatrician who worked, lived, and raised his children in the same small community, I found that seeing and interacting with my patients and their families outside the office in a variety of environments, from the grocery store to the soccer field, and a variety of roles, from coach to school physician, added a richness to my professional life.

I suspect that living in and serving the community where I practiced may have helped provide some meaning on those very rare occasions when I wondered why I was heading off to work in the morning ... or in the middle of the night. But, 90% of the time I felt what I was doing as a physician was somehow making a difference. Nothing earth shaking or worthy of sainthood mind you, but if I were to take the time to look back on my day and weighed the meaningful against the meaningless activities it would almost always tip the scales toward meaningful. But, I seldom had the time to engage in such retrospection.

It seems that many physicians today are not finding that same meaningful versus meaningless balance that I enjoyed. Is it because they are spending too little of their time doing meaningful work? Has the management of the more common illnesses become too routine or so algorithm-driven that it is no longer challenging? One solution to that problem is to shift our focus from the disease to the patient. Diagnosing and managing strep throat is not a terribly challenging intellectual exercise until you realize it is the unique way in which each patient presents and tolerates the illness.

I think the answer is not that there is too little meaningful work for physicians today, and I suspect that you would agree. We are all lucky to have jobs that almost by definition offer an abundance of meaningful activities. There are situations in which it may require a bit of an attitude change to see the meaningfulness, but the opportunities are there. No, the problem seems to be that there is an overabundance of meaningless tasks that confront physicians. Clunky, time-gobbling medical record systems, fighting with insurance companies, chasing down prior authorizations, attending committee meetings in a top-heavy organization with too many meetings, _____________. You can fill in the blank with your favorite.

The CATCH program can offer you a way to rebalance that imbalance, and, by all means, consider applying for a grant. But, where we need to put our energies is in the search for solutions to the glut of meaningless tasks that are burning us out. We shouldn’t have to seek meaningful experiences outside of our offices. They have always been there, hidden under the mountain of meaningless chores.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Community Access to Child Health is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Known by the acronym CATCH, this program provides seed funding to chapters and pediatricians at all stages of their training and practice trajectories to assist in the planing and development of community-based initiatives aimed at increasing children’s access to a variety of health services. While relatively modest in its scale and profile, the CATCH-funded recipients have a strong track record of creating effective and often sustainable projects serving children in historically underserved segments of the community.

In a recent article by Rupal C. Gupta, MD, FAAP, I encountered a quote attributed to Benjamin D. Hoffman, MD, president-elect of the AAP, who served as a chapter CATCH facilitator. Dr. Hoffman observed that “part of the solution to burnout is doing meaningful work, and CATCH allows you to do that.” I couldn’t agree more with Dr. Hoffman’s claim. There is no question that viewing your professional activities as meaningless can be a major contributor to burnout. And, community involvement can certainly provide ample opportunities to do meaningful work.

As a pediatrician who worked, lived, and raised his children in the same small community, I found that seeing and interacting with my patients and their families outside the office in a variety of environments, from the grocery store to the soccer field, and a variety of roles, from coach to school physician, added a richness to my professional life.

I suspect that living in and serving the community where I practiced may have helped provide some meaning on those very rare occasions when I wondered why I was heading off to work in the morning ... or in the middle of the night. But, 90% of the time I felt what I was doing as a physician was somehow making a difference. Nothing earth shaking or worthy of sainthood mind you, but if I were to take the time to look back on my day and weighed the meaningful against the meaningless activities it would almost always tip the scales toward meaningful. But, I seldom had the time to engage in such retrospection.

It seems that many physicians today are not finding that same meaningful versus meaningless balance that I enjoyed. Is it because they are spending too little of their time doing meaningful work? Has the management of the more common illnesses become too routine or so algorithm-driven that it is no longer challenging? One solution to that problem is to shift our focus from the disease to the patient. Diagnosing and managing strep throat is not a terribly challenging intellectual exercise until you realize it is the unique way in which each patient presents and tolerates the illness.

I think the answer is not that there is too little meaningful work for physicians today, and I suspect that you would agree. We are all lucky to have jobs that almost by definition offer an abundance of meaningful activities. There are situations in which it may require a bit of an attitude change to see the meaningfulness, but the opportunities are there. No, the problem seems to be that there is an overabundance of meaningless tasks that confront physicians. Clunky, time-gobbling medical record systems, fighting with insurance companies, chasing down prior authorizations, attending committee meetings in a top-heavy organization with too many meetings, _____________. You can fill in the blank with your favorite.

The CATCH program can offer you a way to rebalance that imbalance, and, by all means, consider applying for a grant. But, where we need to put our energies is in the search for solutions to the glut of meaningless tasks that are burning us out. We shouldn’t have to seek meaningful experiences outside of our offices. They have always been there, hidden under the mountain of meaningless chores.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Liver disease gets new name and diagnostic criteria

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will now be called metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, or MASLD, according to new nomenclature adopted by a global consensus panel composed mostly of hepatology researchers and clinicians.

The new nomenclature, published in the journal Hepatology, includes the umbrella term steatotic liver disease, or SLD, which will cover MASLD and MetALD, a term describing people with MASLD who consume more than 140 grams of alcohol per week for women and 210 grams per week for men.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis, or MASH, will replace the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH.

Mary E. Rinella, MD, of University of Chicago Medicine led the consensus group. The changes were needed, Dr. Rinella and her colleagues argued, because the terms “fatty liver disease” “and nonalcoholic” could be considered to confer stigma, and to better reflect the metabolic dysfunction occurring in the disease. Under the new nomenclature, people with MASLD must have a cardiometabolic risk factor, such as type 2 diabetes. People without metabolic parameters and no known cause will be classed as having cryptogenic SLD.

While the new nomenclature largely conserves existing disease definitions, it allows for alcohol consumption beyond current parameters for nonalcoholic forms of the disease. “There are individuals with risk factors for NAFLD, such as type 2 diabetes, who consume more alcohol than the relatively strict thresholds used to define the nonalcoholic nature of the disease [and] are excluded from trials and consideration for treatments,” the authors wrote.

Moreover, they wrote, “within MetALD there is a continuum where conceptually the condition can be seen to be MASLD or ALD predominant. This may vary over time within a given individual.”

Respondents overwhelmingly agreed, however, that even moderate alcohol use alters the natural history of the disease and that patients with more than minimal alcohol consumption should be analyzed separately in clinical trials.

The new nomenclature reflects a 3-year effort involving some 236 panelists from 56 countries who participated in several rounds of online surveys using a Delphi process. Pediatricians, gastroenterologists, and endocrinologists also participated as well as some patient advocates. Changes were based on a super-majority of opinion (67% or higher), though the consensus on whether the term “fatty” was stigmatizing never reached that threshold. In early rounds of surveys only 44% of respondents considered the word “fatty” to be stigmatizing, while more considered “nonalcoholic” to be problematic.

“Substantial proportions of the respondents deemed terms such as ‘fatty’ stigmatizing, hence its exclusion as part of any new name,” Dr. Rinella and her colleagues wrote. “Although health care professionals may contend that patients have not reported this previously, this likely reflects in part a failure to ask the question in the first place and the power imbalance in the doctor-patient relationship.” The authors noted that the new terminology may help raise awareness at a time when new therapeutics are in sight and it becomes more important to identify at-risk individuals.

Of concern was whether the new definitions would alter the utility of earlier data from registries and trials. However, the authors determined that some 98% of people registered in a European NAFLD cohort would meet the new criteria for MASLD. “Maintenance of the term, and clinical definition, of steatohepatitis ensures retention and validity of prior data from clinical trials and biomarker discovery studies of patients with NASH to be generalizable to individuals classified as MASLD or MASH under the new nomenclature, without impeding the efficiency of research,” they stated.

The effort was spearheaded by three international liver societies: La Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the European Association for the Study of the Liver, as well as the cochairs of the NAFLD Nomenclature Initiative.

Each of the authors disclosed a number of potential conflicts of interest.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will now be called metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, or MASLD, according to new nomenclature adopted by a global consensus panel composed mostly of hepatology researchers and clinicians.

The new nomenclature, published in the journal Hepatology, includes the umbrella term steatotic liver disease, or SLD, which will cover MASLD and MetALD, a term describing people with MASLD who consume more than 140 grams of alcohol per week for women and 210 grams per week for men.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis, or MASH, will replace the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH.

Mary E. Rinella, MD, of University of Chicago Medicine led the consensus group. The changes were needed, Dr. Rinella and her colleagues argued, because the terms “fatty liver disease” “and nonalcoholic” could be considered to confer stigma, and to better reflect the metabolic dysfunction occurring in the disease. Under the new nomenclature, people with MASLD must have a cardiometabolic risk factor, such as type 2 diabetes. People without metabolic parameters and no known cause will be classed as having cryptogenic SLD.

While the new nomenclature largely conserves existing disease definitions, it allows for alcohol consumption beyond current parameters for nonalcoholic forms of the disease. “There are individuals with risk factors for NAFLD, such as type 2 diabetes, who consume more alcohol than the relatively strict thresholds used to define the nonalcoholic nature of the disease [and] are excluded from trials and consideration for treatments,” the authors wrote.

Moreover, they wrote, “within MetALD there is a continuum where conceptually the condition can be seen to be MASLD or ALD predominant. This may vary over time within a given individual.”

Respondents overwhelmingly agreed, however, that even moderate alcohol use alters the natural history of the disease and that patients with more than minimal alcohol consumption should be analyzed separately in clinical trials.

The new nomenclature reflects a 3-year effort involving some 236 panelists from 56 countries who participated in several rounds of online surveys using a Delphi process. Pediatricians, gastroenterologists, and endocrinologists also participated as well as some patient advocates. Changes were based on a super-majority of opinion (67% or higher), though the consensus on whether the term “fatty” was stigmatizing never reached that threshold. In early rounds of surveys only 44% of respondents considered the word “fatty” to be stigmatizing, while more considered “nonalcoholic” to be problematic.

“Substantial proportions of the respondents deemed terms such as ‘fatty’ stigmatizing, hence its exclusion as part of any new name,” Dr. Rinella and her colleagues wrote. “Although health care professionals may contend that patients have not reported this previously, this likely reflects in part a failure to ask the question in the first place and the power imbalance in the doctor-patient relationship.” The authors noted that the new terminology may help raise awareness at a time when new therapeutics are in sight and it becomes more important to identify at-risk individuals.

Of concern was whether the new definitions would alter the utility of earlier data from registries and trials. However, the authors determined that some 98% of people registered in a European NAFLD cohort would meet the new criteria for MASLD. “Maintenance of the term, and clinical definition, of steatohepatitis ensures retention and validity of prior data from clinical trials and biomarker discovery studies of patients with NASH to be generalizable to individuals classified as MASLD or MASH under the new nomenclature, without impeding the efficiency of research,” they stated.

The effort was spearheaded by three international liver societies: La Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the European Association for the Study of the Liver, as well as the cochairs of the NAFLD Nomenclature Initiative.

Each of the authors disclosed a number of potential conflicts of interest.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will now be called metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, or MASLD, according to new nomenclature adopted by a global consensus panel composed mostly of hepatology researchers and clinicians.

The new nomenclature, published in the journal Hepatology, includes the umbrella term steatotic liver disease, or SLD, which will cover MASLD and MetALD, a term describing people with MASLD who consume more than 140 grams of alcohol per week for women and 210 grams per week for men.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis, or MASH, will replace the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH.

Mary E. Rinella, MD, of University of Chicago Medicine led the consensus group. The changes were needed, Dr. Rinella and her colleagues argued, because the terms “fatty liver disease” “and nonalcoholic” could be considered to confer stigma, and to better reflect the metabolic dysfunction occurring in the disease. Under the new nomenclature, people with MASLD must have a cardiometabolic risk factor, such as type 2 diabetes. People without metabolic parameters and no known cause will be classed as having cryptogenic SLD.

While the new nomenclature largely conserves existing disease definitions, it allows for alcohol consumption beyond current parameters for nonalcoholic forms of the disease. “There are individuals with risk factors for NAFLD, such as type 2 diabetes, who consume more alcohol than the relatively strict thresholds used to define the nonalcoholic nature of the disease [and] are excluded from trials and consideration for treatments,” the authors wrote.

Moreover, they wrote, “within MetALD there is a continuum where conceptually the condition can be seen to be MASLD or ALD predominant. This may vary over time within a given individual.”

Respondents overwhelmingly agreed, however, that even moderate alcohol use alters the natural history of the disease and that patients with more than minimal alcohol consumption should be analyzed separately in clinical trials.

The new nomenclature reflects a 3-year effort involving some 236 panelists from 56 countries who participated in several rounds of online surveys using a Delphi process. Pediatricians, gastroenterologists, and endocrinologists also participated as well as some patient advocates. Changes were based on a super-majority of opinion (67% or higher), though the consensus on whether the term “fatty” was stigmatizing never reached that threshold. In early rounds of surveys only 44% of respondents considered the word “fatty” to be stigmatizing, while more considered “nonalcoholic” to be problematic.

“Substantial proportions of the respondents deemed terms such as ‘fatty’ stigmatizing, hence its exclusion as part of any new name,” Dr. Rinella and her colleagues wrote. “Although health care professionals may contend that patients have not reported this previously, this likely reflects in part a failure to ask the question in the first place and the power imbalance in the doctor-patient relationship.” The authors noted that the new terminology may help raise awareness at a time when new therapeutics are in sight and it becomes more important to identify at-risk individuals.

Of concern was whether the new definitions would alter the utility of earlier data from registries and trials. However, the authors determined that some 98% of people registered in a European NAFLD cohort would meet the new criteria for MASLD. “Maintenance of the term, and clinical definition, of steatohepatitis ensures retention and validity of prior data from clinical trials and biomarker discovery studies of patients with NASH to be generalizable to individuals classified as MASLD or MASH under the new nomenclature, without impeding the efficiency of research,” they stated.

The effort was spearheaded by three international liver societies: La Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the European Association for the Study of the Liver, as well as the cochairs of the NAFLD Nomenclature Initiative.

Each of the authors disclosed a number of potential conflicts of interest.

FROM HEPATOLOGY

RAPID updates in pleural infection

Thoracic Oncology & Chest Imaging Network

Interventional Procedures Section

The MIST-2 trial (Rahman, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:518), the first randomized trial to show the benefit of intrapleural enzyme therapy (IET) with tissue plasminogen activator and deoxyribonuclease for the treatment of complicated pleural infection (cPI) is the foundational study for the use of IET. It was from this cohort that the first prospectively validated mortality prediction score for cPI was developed – the RAPID score (Rahman, et al. Chest. 2014;145[4]:848).

The RAPID score, comprised of Renal, Age, Purulence, Infection source, and Dietary factors (albumin) divides patients with cPI into three 3-month mortality groups: low (1.5%), medium (17.8%), and high (47.8%). The score was externally validated in the PILOT trial (Corcoran, et al. Eur Respir J. 2020;56[5]:2000130). Mortality outcomes were separately assessed in 1-, 3-, and 5-year follow-up by White, et al (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12[9]:1310) and found to bear out with an increased OR for mortality of 14.3 and 53.3 in the medium and high risk groups, respectively. Of note, there was a surgical referral rate of only 4% to16% in the study cohort, and the original study did not distinguish between IET use or surgery.

To look at RAPID in a purely surgical cohort, Stüben, et al (Sci Rep. 2023;13[1]:3206) applied the RAPID score to a cohort of patients with empyema all treated with initial surgical drainage. They found the RAPID score to be an accurate predictor of 90-day mortality and improved with the addition of diabetes and renal replacement therapy. Liou, et al (J Thorac Dis. 2023;15[3]:985) showed that patients with a low RAPID score who were taken to surgery early had improved length of stay and organ failure and mortality rates compared with those taken later.

Can the RAPID score differentiate between those who need IET alone, early surgery, or late surgery? Not yet, but several prospective studies are underway to help improve outcomes in this ancient disease. Until then, the RAPID score remains a useful risk-stratification tool for an increasingly broad population of patients with pleural infection.

Max Diddams, MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Thoracic Oncology & Chest Imaging Network

Interventional Procedures Section

The MIST-2 trial (Rahman, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:518), the first randomized trial to show the benefit of intrapleural enzyme therapy (IET) with tissue plasminogen activator and deoxyribonuclease for the treatment of complicated pleural infection (cPI) is the foundational study for the use of IET. It was from this cohort that the first prospectively validated mortality prediction score for cPI was developed – the RAPID score (Rahman, et al. Chest. 2014;145[4]:848).

The RAPID score, comprised of Renal, Age, Purulence, Infection source, and Dietary factors (albumin) divides patients with cPI into three 3-month mortality groups: low (1.5%), medium (17.8%), and high (47.8%). The score was externally validated in the PILOT trial (Corcoran, et al. Eur Respir J. 2020;56[5]:2000130). Mortality outcomes were separately assessed in 1-, 3-, and 5-year follow-up by White, et al (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12[9]:1310) and found to bear out with an increased OR for mortality of 14.3 and 53.3 in the medium and high risk groups, respectively. Of note, there was a surgical referral rate of only 4% to16% in the study cohort, and the original study did not distinguish between IET use or surgery.