User login

Deer populations pose COVID risk to humans: Study

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which led the research project, humans transmitted the virus to deer at least 100 times. The virus then spread widely among free-ranging deer populations, and there were three possible cases of the deer transmitting the virus to humans.

The data comes from tests done between November 2021 and April 2022 on more than 12,000 deer found across half of the United States. Sequencing of the virus found in the deer showed that deer had been exposed to all of the prominent variants, including Alpha, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron.

Some of the findings about transmission were published in the journal Nature Communications, in which researchers noted that in addition to being identified in deer, the virus has been found in wild and domestic animals, including mink, rats, otters, ferrets, hamsters, gorillas, cats, dogs, lions, and tigers. Animal-to-human transmission has been documented or suspected in mink and domestic cats, in addition to white-tailed deer.

The findings are important because the animal populations can become “reservoirs ... in which the virus circulates covertly, persisting in the population and can be transmitted to other animals or humans potentially causing disease outbreaks,” according to the paper, which was a collaboration among scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CDC, and the University of Missouri–Columbia.

In the three cases of possible deer-to-human transmission, researchers said that mutated versions of the virus previously found only in deer had been found in COVID test samples taken from one person in North Carolina and two people in Massachusetts. Those deer-specific mutated versions of the virus have not been found in any other human samples, lending evidence that the mutations occurred within deer.

“Deer regularly interact with humans and are commonly found in human environments – near our homes, pets, wastewater, and trash,” researcher and University of Missouri–Columbia professor Xiu-Feng “Henry” Wan, PhD, said in a statement. “The potential for SARS-CoV-2, or any zoonotic disease, to persist and evolve in wildlife populations can pose unique public health risks.”

In the Nature Communications paper, the researchers suggested that deer may be exposed to the virus from human food waste, masks, or other waste products. The authors concluded that further study is needed to determine how virus transmission occurs between deer and humans.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which led the research project, humans transmitted the virus to deer at least 100 times. The virus then spread widely among free-ranging deer populations, and there were three possible cases of the deer transmitting the virus to humans.

The data comes from tests done between November 2021 and April 2022 on more than 12,000 deer found across half of the United States. Sequencing of the virus found in the deer showed that deer had been exposed to all of the prominent variants, including Alpha, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron.

Some of the findings about transmission were published in the journal Nature Communications, in which researchers noted that in addition to being identified in deer, the virus has been found in wild and domestic animals, including mink, rats, otters, ferrets, hamsters, gorillas, cats, dogs, lions, and tigers. Animal-to-human transmission has been documented or suspected in mink and domestic cats, in addition to white-tailed deer.

The findings are important because the animal populations can become “reservoirs ... in which the virus circulates covertly, persisting in the population and can be transmitted to other animals or humans potentially causing disease outbreaks,” according to the paper, which was a collaboration among scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CDC, and the University of Missouri–Columbia.

In the three cases of possible deer-to-human transmission, researchers said that mutated versions of the virus previously found only in deer had been found in COVID test samples taken from one person in North Carolina and two people in Massachusetts. Those deer-specific mutated versions of the virus have not been found in any other human samples, lending evidence that the mutations occurred within deer.

“Deer regularly interact with humans and are commonly found in human environments – near our homes, pets, wastewater, and trash,” researcher and University of Missouri–Columbia professor Xiu-Feng “Henry” Wan, PhD, said in a statement. “The potential for SARS-CoV-2, or any zoonotic disease, to persist and evolve in wildlife populations can pose unique public health risks.”

In the Nature Communications paper, the researchers suggested that deer may be exposed to the virus from human food waste, masks, or other waste products. The authors concluded that further study is needed to determine how virus transmission occurs between deer and humans.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which led the research project, humans transmitted the virus to deer at least 100 times. The virus then spread widely among free-ranging deer populations, and there were three possible cases of the deer transmitting the virus to humans.

The data comes from tests done between November 2021 and April 2022 on more than 12,000 deer found across half of the United States. Sequencing of the virus found in the deer showed that deer had been exposed to all of the prominent variants, including Alpha, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron.

Some of the findings about transmission were published in the journal Nature Communications, in which researchers noted that in addition to being identified in deer, the virus has been found in wild and domestic animals, including mink, rats, otters, ferrets, hamsters, gorillas, cats, dogs, lions, and tigers. Animal-to-human transmission has been documented or suspected in mink and domestic cats, in addition to white-tailed deer.

The findings are important because the animal populations can become “reservoirs ... in which the virus circulates covertly, persisting in the population and can be transmitted to other animals or humans potentially causing disease outbreaks,” according to the paper, which was a collaboration among scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CDC, and the University of Missouri–Columbia.

In the three cases of possible deer-to-human transmission, researchers said that mutated versions of the virus previously found only in deer had been found in COVID test samples taken from one person in North Carolina and two people in Massachusetts. Those deer-specific mutated versions of the virus have not been found in any other human samples, lending evidence that the mutations occurred within deer.

“Deer regularly interact with humans and are commonly found in human environments – near our homes, pets, wastewater, and trash,” researcher and University of Missouri–Columbia professor Xiu-Feng “Henry” Wan, PhD, said in a statement. “The potential for SARS-CoV-2, or any zoonotic disease, to persist and evolve in wildlife populations can pose unique public health risks.”

In the Nature Communications paper, the researchers suggested that deer may be exposed to the virus from human food waste, masks, or other waste products. The authors concluded that further study is needed to determine how virus transmission occurs between deer and humans.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

FDA approves new device for enlarged prostate treatment

Designed and marketed by Urotronic (Plymouth, Minn.), the Optilume BPH Catheter System employs mechanical dilation to relieve obstruction of the prostate and then delivers paclitaxel to aid in prostate healing. The device is used in an outpatient setting and is less invasive than other procedures.

“There’s nothing else like Optilume BPH that’s currently available, it’s the only treatment option that requires no cutting, burning, steaming, or implants,” said Urotronic President and CEO David Perry in a press release.

Two randomized trials, EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE, both showed that the Optilume BPH system improved urinary flow rate and decreased the amount of urine stored in the bladder following urination. Men who used the OPTILUME device were able to ejaculate normally and reported no sexual difficulties.

“Optilume BPH is the next generation of minimally invasive technology, creating a new drug device space among BPH therapies,” Steven A. Kaplan, MD, professor of urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in the press release. Dr. Kaplan led the EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE studies, which Urotronic funded.

More than 80% of men older than age 70 have an enlarged prostate, based on autopsy analyses.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Designed and marketed by Urotronic (Plymouth, Minn.), the Optilume BPH Catheter System employs mechanical dilation to relieve obstruction of the prostate and then delivers paclitaxel to aid in prostate healing. The device is used in an outpatient setting and is less invasive than other procedures.

“There’s nothing else like Optilume BPH that’s currently available, it’s the only treatment option that requires no cutting, burning, steaming, or implants,” said Urotronic President and CEO David Perry in a press release.

Two randomized trials, EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE, both showed that the Optilume BPH system improved urinary flow rate and decreased the amount of urine stored in the bladder following urination. Men who used the OPTILUME device were able to ejaculate normally and reported no sexual difficulties.

“Optilume BPH is the next generation of minimally invasive technology, creating a new drug device space among BPH therapies,” Steven A. Kaplan, MD, professor of urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in the press release. Dr. Kaplan led the EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE studies, which Urotronic funded.

More than 80% of men older than age 70 have an enlarged prostate, based on autopsy analyses.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Designed and marketed by Urotronic (Plymouth, Minn.), the Optilume BPH Catheter System employs mechanical dilation to relieve obstruction of the prostate and then delivers paclitaxel to aid in prostate healing. The device is used in an outpatient setting and is less invasive than other procedures.

“There’s nothing else like Optilume BPH that’s currently available, it’s the only treatment option that requires no cutting, burning, steaming, or implants,” said Urotronic President and CEO David Perry in a press release.

Two randomized trials, EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE, both showed that the Optilume BPH system improved urinary flow rate and decreased the amount of urine stored in the bladder following urination. Men who used the OPTILUME device were able to ejaculate normally and reported no sexual difficulties.

“Optilume BPH is the next generation of minimally invasive technology, creating a new drug device space among BPH therapies,” Steven A. Kaplan, MD, professor of urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in the press release. Dr. Kaplan led the EVEREST-1 and PINNACLE studies, which Urotronic funded.

More than 80% of men older than age 70 have an enlarged prostate, based on autopsy analyses.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incidental hepatic steatosis

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Spirometry predicts mortality in type 2 diabetes

Among adults with type 2 diabetes, the presence of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality and both macro- and microvascular complications, as well as increased mortality, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

Guochen Li, MD, of the Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, and colleagues wrote.

“A growing number of studies have demonstrated that impaired lung function and type 2 diabetes could trigger shared pathophysiological injuries, such as microangiopathy and chronic inflammation,” they said, but the potential role of PRISm as an early predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes has not been fully examined.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 20,047 individuals with type 2 diabetes in the UK Biobank, a population-based cohort of adults aged 37-73 years recruited between 2006 and 2010.

The main exposure was lung function based on spirometry. PRISm was defined as predicted forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) less than 80%, with an FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of at least 0.70. Individuals with normal spirometry (defined as predicted FEV1 ≥ 80% with an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.70) served as controls.

The primary outcomes were major complications of type 2 diabetes including macrovascular events (myocardial infarction, unstable angina, coronary heart disease [CHD], ischemic stroke, and any type of stroke), microvascular events (diabetic retinopathy and diabetic kidney disease) and mortality (all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory).

Overall, 16.9% of study participants (3385 patients) had obstructive spirometry and 22.6% (4521 patients) had PRISm. Compared with individuals with normal spirometry, those with PRISm were more likely to be current smokers, obese, and living in economically disadvantaged areas. Individuals with PRISm also were significantly more likely to be long-term patients with diabetes who were taking glucose-lowering or lipid-lowering drugs (P < .001 for all).

The median follow-up for each of the type 2 diabetes complications and mortality was approximately 12 years. Over this time, 5.0% of patients developed incident MI, 1.3% developed unstable angina, 15.6% had CHD, 3.5% had an ischemic stroke, and 4.7% had any type of stroke. As for microvascular events, 7.8% developed diabetic retinopathy and 6.7% developed diabetic kidney disease. A total of 2588 patients died during the study period (15.1%), including 544 from cardiovascular disease and 319 from respiratory disease.

PRISm was significantly associated with increased risk of each of the complications and mortality types. These associations persisted after adjusting for lifestyle and other factors. The fully adjusted hazard ratios for PRISm versus normal spirometry were 1.23 for MI, 1.23 for unstable angina, 1.21 for CHD, 1.38 for ischemic stroke, 1.41 for any type of stroke, 1.31 for diabetic retinopathy, and 1.38 for diabetic kidney disease. Adjusted HRs for mortality were 1.34, 1.60, and 1.56 for all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality, respectively.

The researchers also found that adding PRISm to an office-based risk score significantly improved the risk classification and predictive power for type 2 diabetes complications with the exception of unstable angina and mortality. They found little evidence for an association with sex, smoking, or PRISm duration and any mortality types. However, in subgroup analyses by age, sex, and duration of diabetes, PRISm remained associated with increased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications, as well as mortality.

Potential mechanisms for the association between PRISm and diabetes complications include the role of insulin resistance in the exacerbation of lung damage in patients with type 2 diabetes, the increased rate of supplemental oxygen use among individuals with PRISm, and the increased prevalence of pulmonary artery enlargement in the PRISm subjects, the researchers wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the prospective design, the homogeneous population of individuals primarily of British or Irish ancestry, and the exclusion of diabetic neuropathy from the analysis, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large cohort, use of professional spirometry, and relatively long follow-up. “The findings underscore the relevance of PRISm for prognostic classification in type 2 diabetes and its potential for optimizing prevention strategies in this condition,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Among adults with type 2 diabetes, the presence of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality and both macro- and microvascular complications, as well as increased mortality, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

Guochen Li, MD, of the Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, and colleagues wrote.

“A growing number of studies have demonstrated that impaired lung function and type 2 diabetes could trigger shared pathophysiological injuries, such as microangiopathy and chronic inflammation,” they said, but the potential role of PRISm as an early predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes has not been fully examined.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 20,047 individuals with type 2 diabetes in the UK Biobank, a population-based cohort of adults aged 37-73 years recruited between 2006 and 2010.

The main exposure was lung function based on spirometry. PRISm was defined as predicted forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) less than 80%, with an FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of at least 0.70. Individuals with normal spirometry (defined as predicted FEV1 ≥ 80% with an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.70) served as controls.

The primary outcomes were major complications of type 2 diabetes including macrovascular events (myocardial infarction, unstable angina, coronary heart disease [CHD], ischemic stroke, and any type of stroke), microvascular events (diabetic retinopathy and diabetic kidney disease) and mortality (all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory).

Overall, 16.9% of study participants (3385 patients) had obstructive spirometry and 22.6% (4521 patients) had PRISm. Compared with individuals with normal spirometry, those with PRISm were more likely to be current smokers, obese, and living in economically disadvantaged areas. Individuals with PRISm also were significantly more likely to be long-term patients with diabetes who were taking glucose-lowering or lipid-lowering drugs (P < .001 for all).

The median follow-up for each of the type 2 diabetes complications and mortality was approximately 12 years. Over this time, 5.0% of patients developed incident MI, 1.3% developed unstable angina, 15.6% had CHD, 3.5% had an ischemic stroke, and 4.7% had any type of stroke. As for microvascular events, 7.8% developed diabetic retinopathy and 6.7% developed diabetic kidney disease. A total of 2588 patients died during the study period (15.1%), including 544 from cardiovascular disease and 319 from respiratory disease.

PRISm was significantly associated with increased risk of each of the complications and mortality types. These associations persisted after adjusting for lifestyle and other factors. The fully adjusted hazard ratios for PRISm versus normal spirometry were 1.23 for MI, 1.23 for unstable angina, 1.21 for CHD, 1.38 for ischemic stroke, 1.41 for any type of stroke, 1.31 for diabetic retinopathy, and 1.38 for diabetic kidney disease. Adjusted HRs for mortality were 1.34, 1.60, and 1.56 for all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality, respectively.

The researchers also found that adding PRISm to an office-based risk score significantly improved the risk classification and predictive power for type 2 diabetes complications with the exception of unstable angina and mortality. They found little evidence for an association with sex, smoking, or PRISm duration and any mortality types. However, in subgroup analyses by age, sex, and duration of diabetes, PRISm remained associated with increased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications, as well as mortality.

Potential mechanisms for the association between PRISm and diabetes complications include the role of insulin resistance in the exacerbation of lung damage in patients with type 2 diabetes, the increased rate of supplemental oxygen use among individuals with PRISm, and the increased prevalence of pulmonary artery enlargement in the PRISm subjects, the researchers wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the prospective design, the homogeneous population of individuals primarily of British or Irish ancestry, and the exclusion of diabetic neuropathy from the analysis, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large cohort, use of professional spirometry, and relatively long follow-up. “The findings underscore the relevance of PRISm for prognostic classification in type 2 diabetes and its potential for optimizing prevention strategies in this condition,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Among adults with type 2 diabetes, the presence of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality and both macro- and microvascular complications, as well as increased mortality, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

Guochen Li, MD, of the Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, and colleagues wrote.

“A growing number of studies have demonstrated that impaired lung function and type 2 diabetes could trigger shared pathophysiological injuries, such as microangiopathy and chronic inflammation,” they said, but the potential role of PRISm as an early predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes has not been fully examined.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 20,047 individuals with type 2 diabetes in the UK Biobank, a population-based cohort of adults aged 37-73 years recruited between 2006 and 2010.

The main exposure was lung function based on spirometry. PRISm was defined as predicted forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) less than 80%, with an FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of at least 0.70. Individuals with normal spirometry (defined as predicted FEV1 ≥ 80% with an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.70) served as controls.

The primary outcomes were major complications of type 2 diabetes including macrovascular events (myocardial infarction, unstable angina, coronary heart disease [CHD], ischemic stroke, and any type of stroke), microvascular events (diabetic retinopathy and diabetic kidney disease) and mortality (all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory).

Overall, 16.9% of study participants (3385 patients) had obstructive spirometry and 22.6% (4521 patients) had PRISm. Compared with individuals with normal spirometry, those with PRISm were more likely to be current smokers, obese, and living in economically disadvantaged areas. Individuals with PRISm also were significantly more likely to be long-term patients with diabetes who were taking glucose-lowering or lipid-lowering drugs (P < .001 for all).

The median follow-up for each of the type 2 diabetes complications and mortality was approximately 12 years. Over this time, 5.0% of patients developed incident MI, 1.3% developed unstable angina, 15.6% had CHD, 3.5% had an ischemic stroke, and 4.7% had any type of stroke. As for microvascular events, 7.8% developed diabetic retinopathy and 6.7% developed diabetic kidney disease. A total of 2588 patients died during the study period (15.1%), including 544 from cardiovascular disease and 319 from respiratory disease.

PRISm was significantly associated with increased risk of each of the complications and mortality types. These associations persisted after adjusting for lifestyle and other factors. The fully adjusted hazard ratios for PRISm versus normal spirometry were 1.23 for MI, 1.23 for unstable angina, 1.21 for CHD, 1.38 for ischemic stroke, 1.41 for any type of stroke, 1.31 for diabetic retinopathy, and 1.38 for diabetic kidney disease. Adjusted HRs for mortality were 1.34, 1.60, and 1.56 for all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality, respectively.

The researchers also found that adding PRISm to an office-based risk score significantly improved the risk classification and predictive power for type 2 diabetes complications with the exception of unstable angina and mortality. They found little evidence for an association with sex, smoking, or PRISm duration and any mortality types. However, in subgroup analyses by age, sex, and duration of diabetes, PRISm remained associated with increased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications, as well as mortality.

Potential mechanisms for the association between PRISm and diabetes complications include the role of insulin resistance in the exacerbation of lung damage in patients with type 2 diabetes, the increased rate of supplemental oxygen use among individuals with PRISm, and the increased prevalence of pulmonary artery enlargement in the PRISm subjects, the researchers wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the prospective design, the homogeneous population of individuals primarily of British or Irish ancestry, and the exclusion of diabetic neuropathy from the analysis, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large cohort, use of professional spirometry, and relatively long follow-up. “The findings underscore the relevance of PRISm for prognostic classification in type 2 diabetes and its potential for optimizing prevention strategies in this condition,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

Biologics, thiopurines, or methotrexate doesn’t affect fertility or birth outcomes in men with IBD

published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The effort is the first meta-analysis to assess semen parameters and the risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy for male patients with IBD who have taken biologics, thiopurines or methotrexate for the condition, the researchers said.

“We provide encouraging evidence that biologic, thiopurine, and methotrexate therapy among male patients with IBD are not associated with impairments in male fertility or with increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes,” said the researchers, led in part by John Gubatan, MD, instructor in medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, who worked with investigators in Copenhagen and Toronto. “Taken together, our data support the safety of continuing biologics, thiopurines, or methotrexate across the reproductive spectrum.”

Questions of fertility and pregnancy outcomes are of particular importance in IBD, since patients are often diagnosed around the time of their reproductive years – about 30 years old for Crohn’s disease and 35 years old for ulcerative colitis. There has been far more research attention paid to female than male reproductive considerations, mainly the health of the fetus when the mother takes biologic therapy for IBD during pregnancy, which has generally found to be safe.

Their search found 13 studies with male IBD patients exposed to biologics, 10 exposed to thiopurines and 6 to methotrexate. Researchers extracted data on sperm count, sperm motility, and abnormal sperm morphology – three metrics considered a proxy for male fertility – as well as early pregnancy loss, preterm birth and congenital malformations.

Researchers found no differences between sperm count, motility or morphology between those exposed and not exposed to biologics, thiopurines and methotrexate, with a couple of exceptions. They actually found that sperm count was higher for thiopurine users, compared with nonusers, and there was only one study on methotrexate and abnormal sperm morphology, so there was no data to pool together for that comparison.

In a subgroup analysis, there was a trend toward higher sperm count in thiopurine users, compared with biologic or methotrexate users, but no differences were seen in the other parameters.

Similarly, there were no significant differences for users and nonusers of these medications for early pregnancy loss, preterm births or congenital malformations, the researchers found.

A prior systematic review suggested that azathioprine might be associated with low sperm count, but this new analysis calls that into question.

“Our results, which demonstrated that thiopurine use among male patients with IBD is associated with increased sperm count, refute this prior finding,” the researchers said. The previous finding, they noted, was only qualitative because the authors didn’t do an analysis to calculate effect size or determine statistical significance.

“Furthermore,” the researchers said, “our study included more updated studies and a greater number of patients.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Understanding the impact of inflammatory bowel disease therapies on fertility and pregnancy outcomes is key toward managing patients with IBD. While there is substantial research on the implications of maternal exposure to IBD medications with reassuring safety data, research in the context of paternal exposure to IBD medications is limited.

This study represents the largest report summarizing data across diverse populations on the topic with reassuring results. It carries important implications in clinical practice and provides further evidence in support of continuing IBD therapy among male patients through pregnancy planning. Certainly, active IBD in male patients is associated with adverse effects on sperm quality and conception likelihood, and it is important to achieve remission prior to pregnancy planning.

Further research on the impact of paternal exposure to newer biologics, including small molecule drugs, and additional analyses after adjusting for potential confounders will advance the field and provide further guidance in clinical practice.

Manasi Agrawal, MD, MS, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She is a research associate with the Center for Molecular Prediction of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aalborg University, Copenhagen. She reports no conflicts.

Understanding the impact of inflammatory bowel disease therapies on fertility and pregnancy outcomes is key toward managing patients with IBD. While there is substantial research on the implications of maternal exposure to IBD medications with reassuring safety data, research in the context of paternal exposure to IBD medications is limited.

This study represents the largest report summarizing data across diverse populations on the topic with reassuring results. It carries important implications in clinical practice and provides further evidence in support of continuing IBD therapy among male patients through pregnancy planning. Certainly, active IBD in male patients is associated with adverse effects on sperm quality and conception likelihood, and it is important to achieve remission prior to pregnancy planning.

Further research on the impact of paternal exposure to newer biologics, including small molecule drugs, and additional analyses after adjusting for potential confounders will advance the field and provide further guidance in clinical practice.

Manasi Agrawal, MD, MS, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She is a research associate with the Center for Molecular Prediction of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aalborg University, Copenhagen. She reports no conflicts.

Understanding the impact of inflammatory bowel disease therapies on fertility and pregnancy outcomes is key toward managing patients with IBD. While there is substantial research on the implications of maternal exposure to IBD medications with reassuring safety data, research in the context of paternal exposure to IBD medications is limited.

This study represents the largest report summarizing data across diverse populations on the topic with reassuring results. It carries important implications in clinical practice and provides further evidence in support of continuing IBD therapy among male patients through pregnancy planning. Certainly, active IBD in male patients is associated with adverse effects on sperm quality and conception likelihood, and it is important to achieve remission prior to pregnancy planning.

Further research on the impact of paternal exposure to newer biologics, including small molecule drugs, and additional analyses after adjusting for potential confounders will advance the field and provide further guidance in clinical practice.

Manasi Agrawal, MD, MS, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She is a research associate with the Center for Molecular Prediction of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aalborg University, Copenhagen. She reports no conflicts.

published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The effort is the first meta-analysis to assess semen parameters and the risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy for male patients with IBD who have taken biologics, thiopurines or methotrexate for the condition, the researchers said.

“We provide encouraging evidence that biologic, thiopurine, and methotrexate therapy among male patients with IBD are not associated with impairments in male fertility or with increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes,” said the researchers, led in part by John Gubatan, MD, instructor in medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, who worked with investigators in Copenhagen and Toronto. “Taken together, our data support the safety of continuing biologics, thiopurines, or methotrexate across the reproductive spectrum.”

Questions of fertility and pregnancy outcomes are of particular importance in IBD, since patients are often diagnosed around the time of their reproductive years – about 30 years old for Crohn’s disease and 35 years old for ulcerative colitis. There has been far more research attention paid to female than male reproductive considerations, mainly the health of the fetus when the mother takes biologic therapy for IBD during pregnancy, which has generally found to be safe.

Their search found 13 studies with male IBD patients exposed to biologics, 10 exposed to thiopurines and 6 to methotrexate. Researchers extracted data on sperm count, sperm motility, and abnormal sperm morphology – three metrics considered a proxy for male fertility – as well as early pregnancy loss, preterm birth and congenital malformations.

Researchers found no differences between sperm count, motility or morphology between those exposed and not exposed to biologics, thiopurines and methotrexate, with a couple of exceptions. They actually found that sperm count was higher for thiopurine users, compared with nonusers, and there was only one study on methotrexate and abnormal sperm morphology, so there was no data to pool together for that comparison.

In a subgroup analysis, there was a trend toward higher sperm count in thiopurine users, compared with biologic or methotrexate users, but no differences were seen in the other parameters.

Similarly, there were no significant differences for users and nonusers of these medications for early pregnancy loss, preterm births or congenital malformations, the researchers found.

A prior systematic review suggested that azathioprine might be associated with low sperm count, but this new analysis calls that into question.

“Our results, which demonstrated that thiopurine use among male patients with IBD is associated with increased sperm count, refute this prior finding,” the researchers said. The previous finding, they noted, was only qualitative because the authors didn’t do an analysis to calculate effect size or determine statistical significance.

“Furthermore,” the researchers said, “our study included more updated studies and a greater number of patients.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The effort is the first meta-analysis to assess semen parameters and the risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy for male patients with IBD who have taken biologics, thiopurines or methotrexate for the condition, the researchers said.

“We provide encouraging evidence that biologic, thiopurine, and methotrexate therapy among male patients with IBD are not associated with impairments in male fertility or with increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes,” said the researchers, led in part by John Gubatan, MD, instructor in medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, who worked with investigators in Copenhagen and Toronto. “Taken together, our data support the safety of continuing biologics, thiopurines, or methotrexate across the reproductive spectrum.”

Questions of fertility and pregnancy outcomes are of particular importance in IBD, since patients are often diagnosed around the time of their reproductive years – about 30 years old for Crohn’s disease and 35 years old for ulcerative colitis. There has been far more research attention paid to female than male reproductive considerations, mainly the health of the fetus when the mother takes biologic therapy for IBD during pregnancy, which has generally found to be safe.

Their search found 13 studies with male IBD patients exposed to biologics, 10 exposed to thiopurines and 6 to methotrexate. Researchers extracted data on sperm count, sperm motility, and abnormal sperm morphology – three metrics considered a proxy for male fertility – as well as early pregnancy loss, preterm birth and congenital malformations.

Researchers found no differences between sperm count, motility or morphology between those exposed and not exposed to biologics, thiopurines and methotrexate, with a couple of exceptions. They actually found that sperm count was higher for thiopurine users, compared with nonusers, and there was only one study on methotrexate and abnormal sperm morphology, so there was no data to pool together for that comparison.

In a subgroup analysis, there was a trend toward higher sperm count in thiopurine users, compared with biologic or methotrexate users, but no differences were seen in the other parameters.

Similarly, there were no significant differences for users and nonusers of these medications for early pregnancy loss, preterm births or congenital malformations, the researchers found.

A prior systematic review suggested that azathioprine might be associated with low sperm count, but this new analysis calls that into question.

“Our results, which demonstrated that thiopurine use among male patients with IBD is associated with increased sperm count, refute this prior finding,” the researchers said. The previous finding, they noted, was only qualitative because the authors didn’t do an analysis to calculate effect size or determine statistical significance.

“Furthermore,” the researchers said, “our study included more updated studies and a greater number of patients.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Higher risk of death with endocrine therapy nonadherence

TOPLINE:

a new systematic review found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators conducted a systematic literature search of five databases, looking for studies involving patients with nonmetastatic hormone receptor–positive breast cancer that were published between 2010 and 2020.

- Adequate adherence was defined as a medical possession ratio – the percentage of days the prescribed treatment dose of adjuvant endocrine therapy was available to the patient – of at least 80%.

- Medication nonpersistence was defined as a period in which no new adjuvant endocrine therapy prescriptions were filled before the scheduled end of treatment of 90-180 days, depending on the study.

- The impact of both parameters on event-free survival, which included breast cancer recurrence, disease-free survival, breast cancer–specific survival, and overall survival cancer was calculated.

- Of 2,026 articles retrieved, 14 studies, with sample sizes ranging from 857 to 30,573 patients, met the eligibility and quality criteria; 11 examined patient adherence, and 6 examined patient persistence.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 10 studies that assessed event-free survival, 7 showed significantly worse survival for nonadherent or nonpersistent patients, at hazard ratios of 1.39-2.44.

- Of nine studies that examined overall survival, seven demonstrated a significantly higher risk for mortality in the groups with nonadherence and nonpersistence, at HRs of 1.26-2.18.

- The largest study, which included data on more than 30,000 patients in Taiwan, found that nonadherence and nonpersistence were associated with a significantly increased risk for mortality, at HRs of 1.98 and 2.18, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The available data highlight the dangers of nonadherence and nonpersistence, showing an up to twofold higher risk of relapse or death for patients who do not use endocrine treatment as prescribed,” the researchers said. “Importantly, improving adherence and persistence represents a low-hanging fruit for increasing survival in luminal breast cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Finn Magnus Eliassen, MD, department of surgery, Stavanger (Norway) University Hospital, was published online on July 4 in BMC Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

- The review is limited by the relatively small number of studies that met the eligibility criteria and by their heterogeneity, which ruled out a meta-analysis.

- There are no gold-standard definitions of adherence and persistence.

DISCLOSURES:

- No funding was declared. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

- A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

a new systematic review found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators conducted a systematic literature search of five databases, looking for studies involving patients with nonmetastatic hormone receptor–positive breast cancer that were published between 2010 and 2020.

- Adequate adherence was defined as a medical possession ratio – the percentage of days the prescribed treatment dose of adjuvant endocrine therapy was available to the patient – of at least 80%.

- Medication nonpersistence was defined as a period in which no new adjuvant endocrine therapy prescriptions were filled before the scheduled end of treatment of 90-180 days, depending on the study.

- The impact of both parameters on event-free survival, which included breast cancer recurrence, disease-free survival, breast cancer–specific survival, and overall survival cancer was calculated.

- Of 2,026 articles retrieved, 14 studies, with sample sizes ranging from 857 to 30,573 patients, met the eligibility and quality criteria; 11 examined patient adherence, and 6 examined patient persistence.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 10 studies that assessed event-free survival, 7 showed significantly worse survival for nonadherent or nonpersistent patients, at hazard ratios of 1.39-2.44.

- Of nine studies that examined overall survival, seven demonstrated a significantly higher risk for mortality in the groups with nonadherence and nonpersistence, at HRs of 1.26-2.18.

- The largest study, which included data on more than 30,000 patients in Taiwan, found that nonadherence and nonpersistence were associated with a significantly increased risk for mortality, at HRs of 1.98 and 2.18, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The available data highlight the dangers of nonadherence and nonpersistence, showing an up to twofold higher risk of relapse or death for patients who do not use endocrine treatment as prescribed,” the researchers said. “Importantly, improving adherence and persistence represents a low-hanging fruit for increasing survival in luminal breast cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Finn Magnus Eliassen, MD, department of surgery, Stavanger (Norway) University Hospital, was published online on July 4 in BMC Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

- The review is limited by the relatively small number of studies that met the eligibility criteria and by their heterogeneity, which ruled out a meta-analysis.

- There are no gold-standard definitions of adherence and persistence.

DISCLOSURES:

- No funding was declared. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

- A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

a new systematic review found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators conducted a systematic literature search of five databases, looking for studies involving patients with nonmetastatic hormone receptor–positive breast cancer that were published between 2010 and 2020.

- Adequate adherence was defined as a medical possession ratio – the percentage of days the prescribed treatment dose of adjuvant endocrine therapy was available to the patient – of at least 80%.

- Medication nonpersistence was defined as a period in which no new adjuvant endocrine therapy prescriptions were filled before the scheduled end of treatment of 90-180 days, depending on the study.

- The impact of both parameters on event-free survival, which included breast cancer recurrence, disease-free survival, breast cancer–specific survival, and overall survival cancer was calculated.

- Of 2,026 articles retrieved, 14 studies, with sample sizes ranging from 857 to 30,573 patients, met the eligibility and quality criteria; 11 examined patient adherence, and 6 examined patient persistence.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 10 studies that assessed event-free survival, 7 showed significantly worse survival for nonadherent or nonpersistent patients, at hazard ratios of 1.39-2.44.

- Of nine studies that examined overall survival, seven demonstrated a significantly higher risk for mortality in the groups with nonadherence and nonpersistence, at HRs of 1.26-2.18.

- The largest study, which included data on more than 30,000 patients in Taiwan, found that nonadherence and nonpersistence were associated with a significantly increased risk for mortality, at HRs of 1.98 and 2.18, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The available data highlight the dangers of nonadherence and nonpersistence, showing an up to twofold higher risk of relapse or death for patients who do not use endocrine treatment as prescribed,” the researchers said. “Importantly, improving adherence and persistence represents a low-hanging fruit for increasing survival in luminal breast cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Finn Magnus Eliassen, MD, department of surgery, Stavanger (Norway) University Hospital, was published online on July 4 in BMC Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

- The review is limited by the relatively small number of studies that met the eligibility criteria and by their heterogeneity, which ruled out a meta-analysis.

- There are no gold-standard definitions of adherence and persistence.

DISCLOSURES:

- No funding was declared. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

- A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lower-dose FOLFIRINOX effective, safer for pancreatic cancer

TOPLINE:

Although practice patterns vary widely, and it is less likely to cause febrile neutropenia.

METHODOLOGY:

- No randomized controlled trials have directly compared modified FOLFIRINOX to standard FOLFIRINOX; this meta-analysis aims to fill the evidence gap.

- The investigators winnowed hundreds of first-line FOLFIRINOX studies down to 37 – 11 prospective and 26 retrospective analyses – to assess practice patterns and clinical outcomes.

- Dose information was grouped into four categories: planned dose in the standard FOLFIRINOX group; actual administered dose in the standard group; planned dose in the modified group; actual administered dose in the modified group.

TAKEAWAY:

- There were 12 types of “planned” dose reductions in FOLFIRINOX: 75%-100% oxaliplatin, 75%-100% irinotecan, 0%-100% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) bolus, and 75%-133% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Doses actually delivered fell further to 54%-96% for oxaliplatin, 61%-88% for irinotecan, 0%-92% for 5-FU bolus, and 63%-98% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Despite the variations in dosing, reduced doses of FOLFIRINOX were associated with a slightly but not significantly higher objective response rate: 33.8% versus 28.2% for standard dosing (P = .1).

- The incidence of febrile neutropenia was significantly lower in the reduced-dose groups: 5.5% with modified FOLFIRINOX versus 11.6% with standard (P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study supports reduced-dose regimens, it also shows that there is “still no consensus” on appropriate dose modification, the authors said. “The best dose modification protocol” remains to be determined and standardized for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kwangrok Jung at Seoul (South Korea) National University, and was published June 29 in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

- Only 11 of the 37 studies were prospective.

- The studies often lacked key information, including the reason for dose reductions or detailed dose reduction protocols.

- Studies were also inconsistent in how they reported FOLFIRINOX dose modifications.

DISCLOSURES:

There was no funding for the study, and the investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Although practice patterns vary widely, and it is less likely to cause febrile neutropenia.

METHODOLOGY:

- No randomized controlled trials have directly compared modified FOLFIRINOX to standard FOLFIRINOX; this meta-analysis aims to fill the evidence gap.

- The investigators winnowed hundreds of first-line FOLFIRINOX studies down to 37 – 11 prospective and 26 retrospective analyses – to assess practice patterns and clinical outcomes.

- Dose information was grouped into four categories: planned dose in the standard FOLFIRINOX group; actual administered dose in the standard group; planned dose in the modified group; actual administered dose in the modified group.

TAKEAWAY:

- There were 12 types of “planned” dose reductions in FOLFIRINOX: 75%-100% oxaliplatin, 75%-100% irinotecan, 0%-100% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) bolus, and 75%-133% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Doses actually delivered fell further to 54%-96% for oxaliplatin, 61%-88% for irinotecan, 0%-92% for 5-FU bolus, and 63%-98% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Despite the variations in dosing, reduced doses of FOLFIRINOX were associated with a slightly but not significantly higher objective response rate: 33.8% versus 28.2% for standard dosing (P = .1).

- The incidence of febrile neutropenia was significantly lower in the reduced-dose groups: 5.5% with modified FOLFIRINOX versus 11.6% with standard (P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study supports reduced-dose regimens, it also shows that there is “still no consensus” on appropriate dose modification, the authors said. “The best dose modification protocol” remains to be determined and standardized for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kwangrok Jung at Seoul (South Korea) National University, and was published June 29 in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

- Only 11 of the 37 studies were prospective.

- The studies often lacked key information, including the reason for dose reductions or detailed dose reduction protocols.

- Studies were also inconsistent in how they reported FOLFIRINOX dose modifications.

DISCLOSURES:

There was no funding for the study, and the investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Although practice patterns vary widely, and it is less likely to cause febrile neutropenia.

METHODOLOGY:

- No randomized controlled trials have directly compared modified FOLFIRINOX to standard FOLFIRINOX; this meta-analysis aims to fill the evidence gap.

- The investigators winnowed hundreds of first-line FOLFIRINOX studies down to 37 – 11 prospective and 26 retrospective analyses – to assess practice patterns and clinical outcomes.

- Dose information was grouped into four categories: planned dose in the standard FOLFIRINOX group; actual administered dose in the standard group; planned dose in the modified group; actual administered dose in the modified group.

TAKEAWAY:

- There were 12 types of “planned” dose reductions in FOLFIRINOX: 75%-100% oxaliplatin, 75%-100% irinotecan, 0%-100% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) bolus, and 75%-133% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Doses actually delivered fell further to 54%-96% for oxaliplatin, 61%-88% for irinotecan, 0%-92% for 5-FU bolus, and 63%-98% 5-FU continuous injection.

- Despite the variations in dosing, reduced doses of FOLFIRINOX were associated with a slightly but not significantly higher objective response rate: 33.8% versus 28.2% for standard dosing (P = .1).

- The incidence of febrile neutropenia was significantly lower in the reduced-dose groups: 5.5% with modified FOLFIRINOX versus 11.6% with standard (P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study supports reduced-dose regimens, it also shows that there is “still no consensus” on appropriate dose modification, the authors said. “The best dose modification protocol” remains to be determined and standardized for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kwangrok Jung at Seoul (South Korea) National University, and was published June 29 in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

- Only 11 of the 37 studies were prospective.

- The studies often lacked key information, including the reason for dose reductions or detailed dose reduction protocols.

- Studies were also inconsistent in how they reported FOLFIRINOX dose modifications.

DISCLOSURES:

There was no funding for the study, and the investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Porocarcinoma Development in a Prior Trauma Site

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma, or malignant poroma, is a rare adnexal malignancy of a predominantly glandular origin that comprises less than 0.01% of all cutaneous neoplasms.1,2 Although exposure to UV radiation and immunosuppression have been implicated in the malignant degeneration of benign poromas into porocarcinomas, at least half of all malignant variants will arise de novo.3,4 Patients present with an evolving nodule or plaque and often are in their seventh or eighth decade of life at the time of diagnosis.2 Localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure has been causatively linked to de novo porocarcinoma formation.2,5 These suppressive and traumatic stimuli drive increased genetic heterogeneity along with characteristic gene mutations in known tumor suppressor genes.6

A 62-year-old man presented with a nonhealing wound on the right hand of 5 years’ duration that had previously been attributed to a penetrating injury with a piece of copper from a refrigerant coolant system. The wound initially blistered and then eventually callused and developed areas of ulceration. The patient consulted multiple physicians for treatment of the intensely pruritic and ulcerated lesion. He received prescriptions for cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, clindamycin, and clobetasol cream, all of which offered minimal improvement. Home therapies including vitamin E and tea tree oil yielded no benefit. The lesion roughly quadrupled in size over the last 5 years.

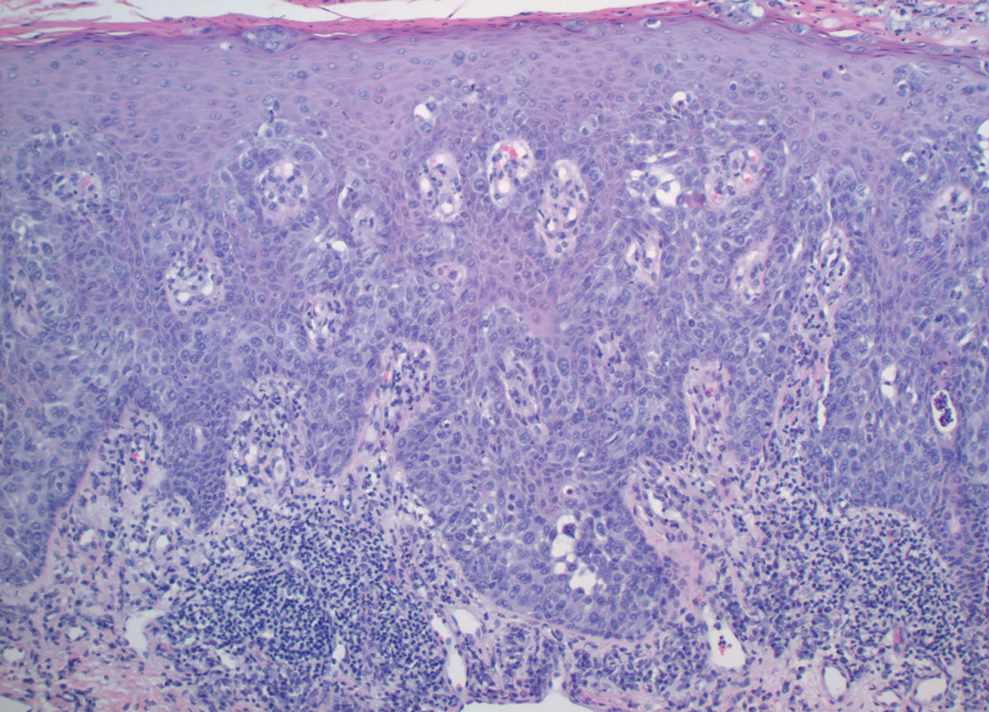

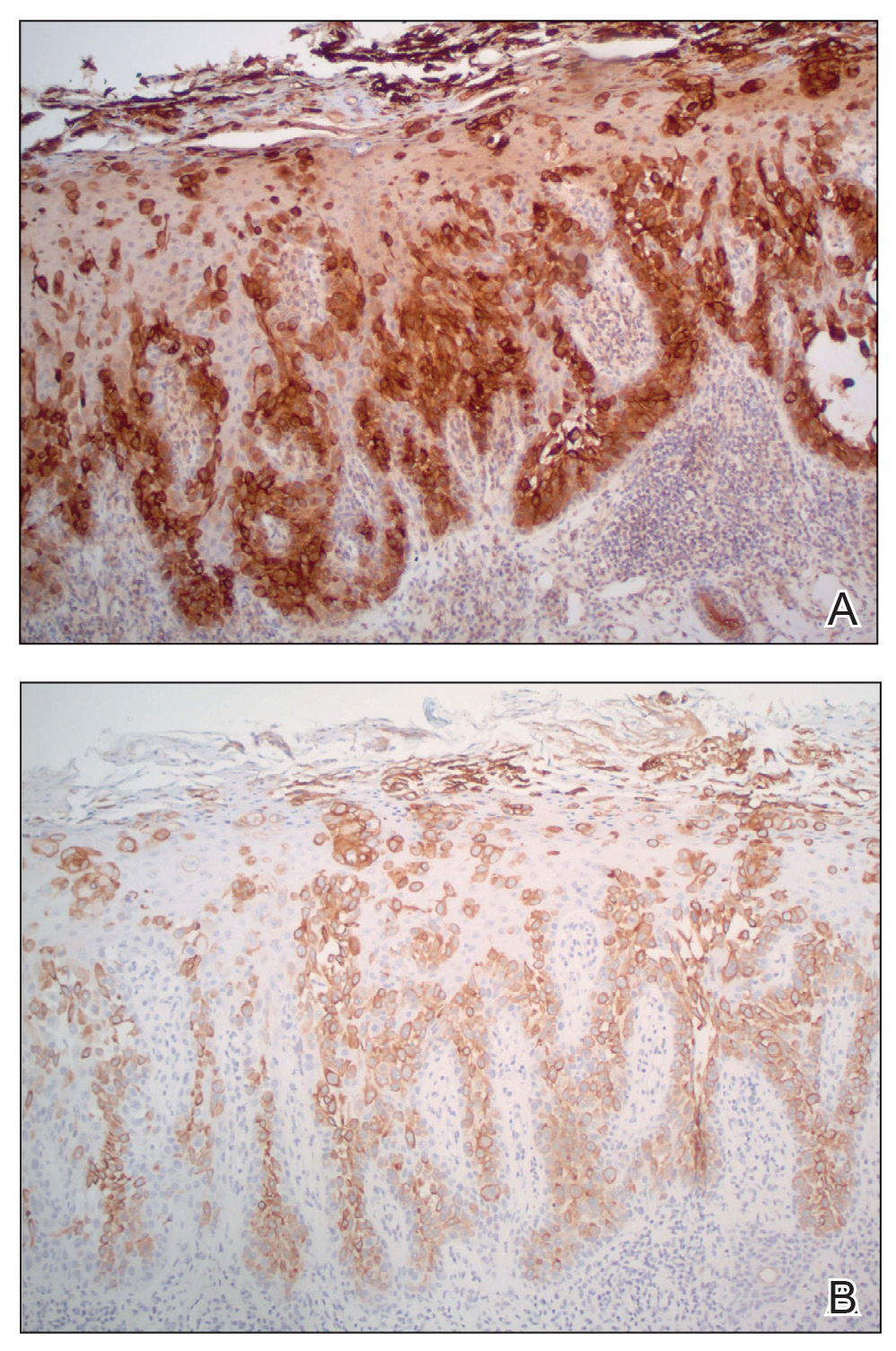

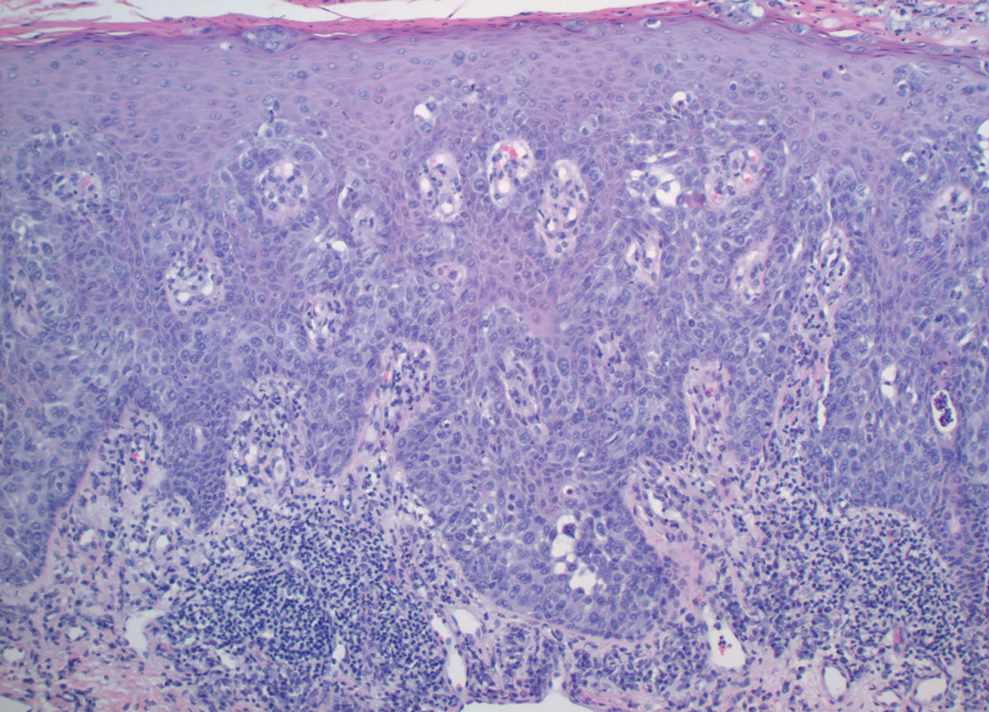

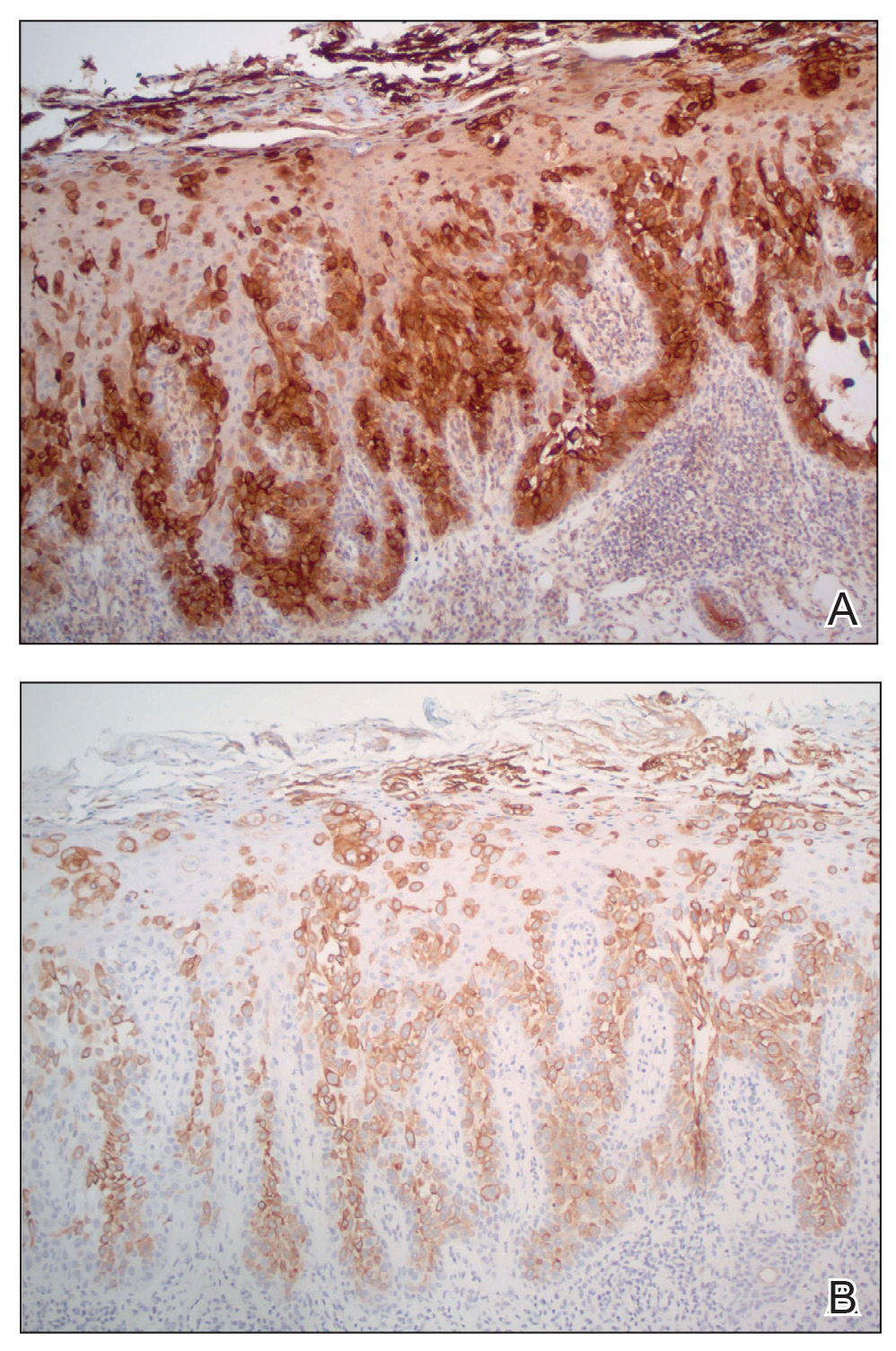

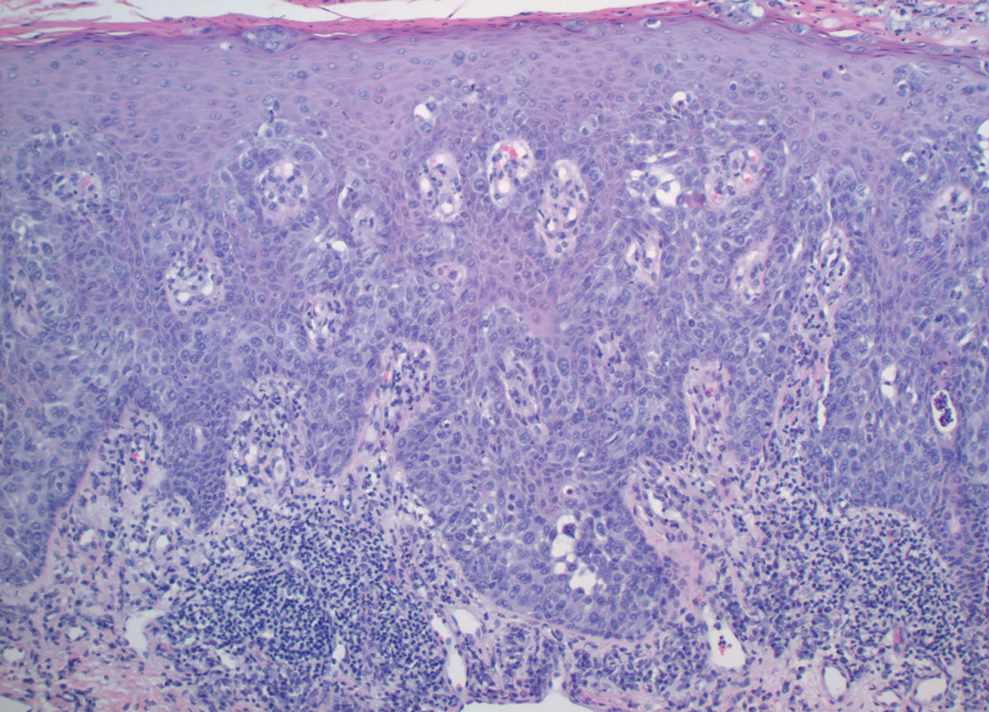

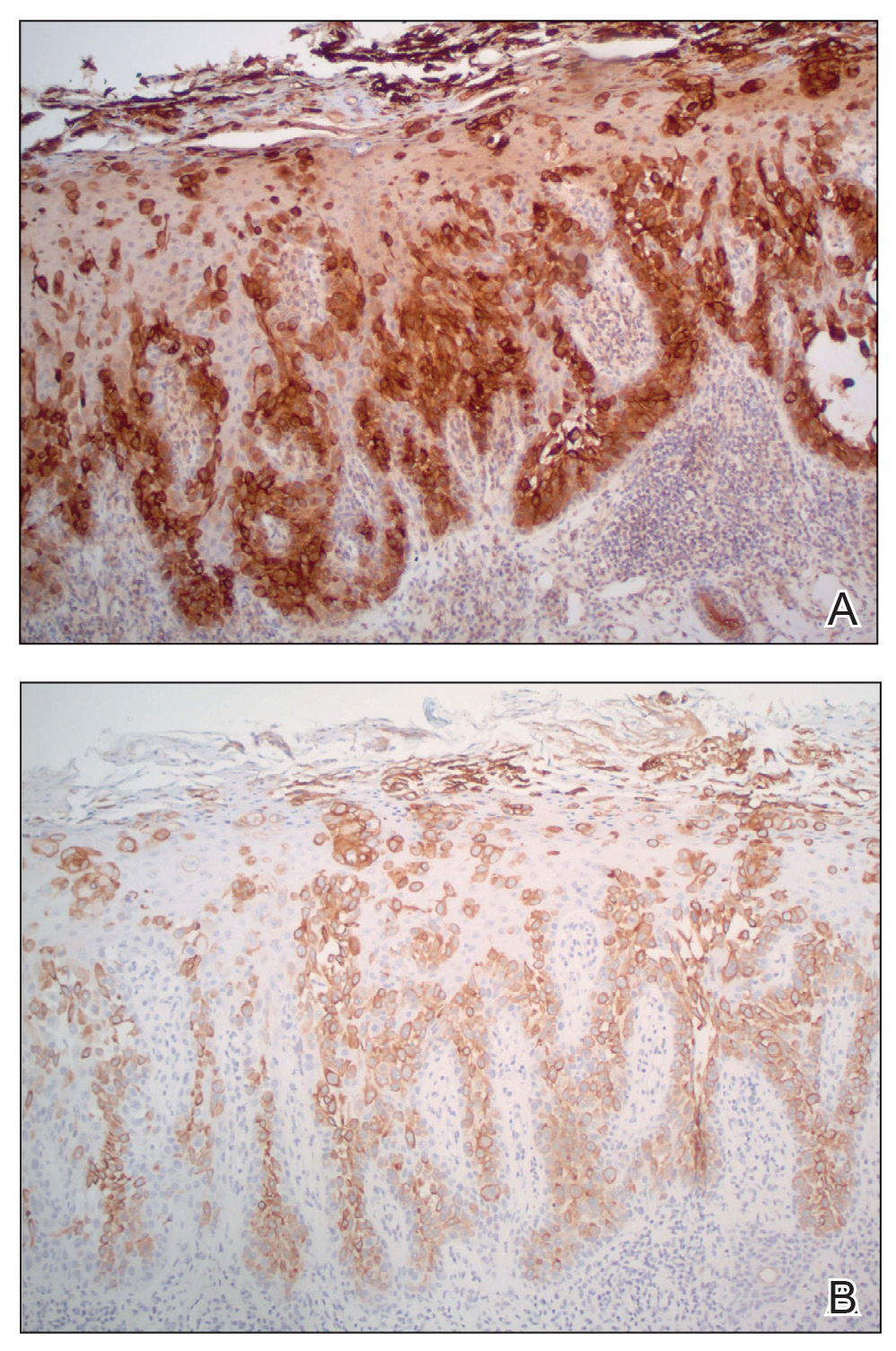

Physical examination revealed a 7.5×4.2-cm ulcerated plaque with ragged borders and abundant central neoepithelialization on the right palmar surface (Figure 1). No gross motor or sensory defects were identified. There was no epitrochlear, axillary, cervical, or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. A shave biopsy of the plaque’s edge was performed, which demonstrated a hyperplastic epidermis comprising atypical poroid cells with frequent mitoses, scant necrosis, and regular ductal structures confined to the epidermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical profiling results were positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2) and Ber-EP4 (Figure 3). When evaluated in aggregate, these findings were consistent with porocarcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for evaluation. At that time, an exophytic mass had developed in the central lesion. Although no lymphadenopathy was identified upon examination, the patient had developed tremoring and a contracture deformity of the right hand. Extensive imaging and urgent surgical resection were recommended, but the patient did not wish to pursue these options, opting instead to continue home remedies. At a 15-month follow-up via telephone, the patient reported that the home therapy had failed and he had moved back to Vietnam. Partial limb amputation had been recommended by a local provider. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up, and his current status is unknown.

Porocarcinomas are rare tumors, comprising just 0.005% to 0.01% of all cutaneous epithelial tumors.1,2,5 They affect men and women equally, with an average age at diagnosis of 60 to 70 years.1,2 At least half of all porocarcinomas develop de novo, while 18% to 50% arise from the degeneration of an existing poroma.2,3 Exposure to UV light and immunosuppression, particularly following organ transplantation, represent 2 commonly suspected catalysts for this malignant transformation.4 De novo porocarcinomas are most causatively linked to localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure.5 Gene mutations in classic tumor suppressor genes—tumor protein p53 (TP53), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), rearranged during transfection (RET), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)—and increased genetic heterogeneity follow these stimuli.6

The morphologic presentation of porocarcinoma is highly variable and may manifest as papules, nodules, or plaques in various states of erosion, ulceration, or excoriation. Diagnoses of basal and squamous cell carcinoma, primary adnexal tumors, seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma must all be considered and methodically ruled out.7 Porocarcinomas may arise nearly anywhere on the body, with a particular predilection for the lower extremities (35%), head/neck (24%), and upper extremities (14%).3,4 Primary lesions arising from the extremities, genitalia, or buttocks herald a higher risk for lymphatic invasion and distant metastasis, while head and neck tumors more commonly remain localized.8 Bleeding, ulceration, or rapid expansion of a preexisting poroma is suggestive of malignant transformation and may portend a more aggressive disease pattern.2,9

Unequivocal diagnosis relies on histological and immunohistochemical studies due to the marked clinical variance of this neoplasm.7 An irregular histologic pattern of poromatous basaloid cells with ductal differentiation and cytologic atypia commonly are seen with porocarcinomas.2,8 Nuclear pleomorphism with cellular necrosis, increased mitotic figures, and abortive ductal formation with a distinct lack of retraction around cellular aggregates often are found. Immunohistochemical staining is needed to confirm the primary tumor diagnosis. Histochemical stains commonly employed include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, p53, p63, Ki67, and periodic acid-Schiff.10 The use of BerEP4 has been reported as efficacious in highlighting sweat structures, which can be particularly useful in cases when basal cell carcinoma is not in the histologic differential.11 These staining profiles afford confirmation of ductal differentiation with CEA, epithelial membrane antigen, and BerEP4, while p63 and Ki67 are used as surrogates for primary cutaneous neoplasia and cell proliferation, respectively.5,11 Porocarcinoma lesions may be most sensitive to CEA and most specific to CK19 (a component of cytokeratin AE1/AE3), though these findings have not been widely reproduced.7

The treatment and prognosis of porocarcinoma vary widely. Surgically excised lesions recur in roughly 20% of cases, though these rates likely include tumors that were incompletely resected in the primary attempt. Although wide local excision with an average 1-cm margin remains the most employed removal technique, Mohs micrographic surgery may more effectively limit recurrence and metastasis of localized disease.7,8,12 Metastatic disease foretells a mortality rate of at least 65%, which is problematic in that 10% to 20% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and another 20% will show metastasis following primary tumor excision.8,10 Neoplasms with high mitotic rates and depths greater than 7 mm should prompt thorough diagnostic imaging, such as positron emission tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. A sentinel lymph node biopsy should be strongly considered and discussed with the patient.10 Treatment options for nodal and distant metastases include a combination of localized surgery, lymphadenectomy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapeutic agents.2,4,5 The response to systemic treatment and radiotherapy often is quite poor, though the use of combinations of docetaxel, paclitaxel, cetuximab, and immunotherapy have been efficacious in smaller studies.8,10 The highest rates of morbidity and mortality are seen in patients with metastases on presentation or with localized tumors in the groin and buttocks.8

The diagnosis of porocarcinoma may be elusive due to its relatively rare occurrence. Therefore, it is critical to consider this neoplasm in high-risk sites in older patients who present with an evolving nodule or tumor on an extremity. Routine histology and astute histochemical profiling are necessary to exclude diseases that mimic porocarcinoma. Once diagnosis is confirmed, management with prompt excision and diagnostic imaging is recommended, including a lymph node biopsy if appropriate. Due to its high metastatic potential and associated morbidity and mortality, patients with porocarcinoma should be followed closely by a multidisciplinary care team.

- Belin E, Ezzedine K, Stanislas S, et al. Factors in the surgical management of primary eccrine porocarcinoma: prognostic histological factors can guide the surgical procedure. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:985-989.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Spencer DM, Bigler LR, Hearne DW, et al. Pedal papule. eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) in association with poroma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:211, 214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Essa RA, et al. Porocarcinoma: a systematic review of literature with a single case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:13-16.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Mosby Elsevier; 2018.

- Bosic M, Kirchner M, Brasanac D, et al. Targeted molecular profiling reveals genetic heterogeneity of poromas and porocarcinomas. Pathology. 2018;50:327-332.

- Mahalingam M, Richards JE, Selim MA, et al. An immunohistochemical comparison of cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 15, cytokeratin 19, CAM 5.2, carcinoembryonic antigen, and nestin in differentiating porocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1265-1272.

- Nazemi A, Higgins S, Swift R, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma: new insights and a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1247-1261.

- Wen SY. Case report of eccrine porocarcinoma in situ associated with eccrine poroma on the forehead. J Dermatol. 2012;39:649-651.

- Gerber PA, Schulte KW, Ruzicka T, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the head: an important differential diagnosis in the elderly patient. Dermatology. 2008;216:229-233.

- Afshar M, Deroide F, Robson A. BerEP4 is widely expressed in tumors of the sweat apparatus: a source of potential diagnostic error. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:259-264.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: the Mayo clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma, or malignant poroma, is a rare adnexal malignancy of a predominantly glandular origin that comprises less than 0.01% of all cutaneous neoplasms.1,2 Although exposure to UV radiation and immunosuppression have been implicated in the malignant degeneration of benign poromas into porocarcinomas, at least half of all malignant variants will arise de novo.3,4 Patients present with an evolving nodule or plaque and often are in their seventh or eighth decade of life at the time of diagnosis.2 Localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure has been causatively linked to de novo porocarcinoma formation.2,5 These suppressive and traumatic stimuli drive increased genetic heterogeneity along with characteristic gene mutations in known tumor suppressor genes.6

A 62-year-old man presented with a nonhealing wound on the right hand of 5 years’ duration that had previously been attributed to a penetrating injury with a piece of copper from a refrigerant coolant system. The wound initially blistered and then eventually callused and developed areas of ulceration. The patient consulted multiple physicians for treatment of the intensely pruritic and ulcerated lesion. He received prescriptions for cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, clindamycin, and clobetasol cream, all of which offered minimal improvement. Home therapies including vitamin E and tea tree oil yielded no benefit. The lesion roughly quadrupled in size over the last 5 years.

Physical examination revealed a 7.5×4.2-cm ulcerated plaque with ragged borders and abundant central neoepithelialization on the right palmar surface (Figure 1). No gross motor or sensory defects were identified. There was no epitrochlear, axillary, cervical, or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. A shave biopsy of the plaque’s edge was performed, which demonstrated a hyperplastic epidermis comprising atypical poroid cells with frequent mitoses, scant necrosis, and regular ductal structures confined to the epidermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical profiling results were positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2) and Ber-EP4 (Figure 3). When evaluated in aggregate, these findings were consistent with porocarcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for evaluation. At that time, an exophytic mass had developed in the central lesion. Although no lymphadenopathy was identified upon examination, the patient had developed tremoring and a contracture deformity of the right hand. Extensive imaging and urgent surgical resection were recommended, but the patient did not wish to pursue these options, opting instead to continue home remedies. At a 15-month follow-up via telephone, the patient reported that the home therapy had failed and he had moved back to Vietnam. Partial limb amputation had been recommended by a local provider. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up, and his current status is unknown.

Porocarcinomas are rare tumors, comprising just 0.005% to 0.01% of all cutaneous epithelial tumors.1,2,5 They affect men and women equally, with an average age at diagnosis of 60 to 70 years.1,2 At least half of all porocarcinomas develop de novo, while 18% to 50% arise from the degeneration of an existing poroma.2,3 Exposure to UV light and immunosuppression, particularly following organ transplantation, represent 2 commonly suspected catalysts for this malignant transformation.4 De novo porocarcinomas are most causatively linked to localized trauma from burns or radiation exposure.5 Gene mutations in classic tumor suppressor genes—tumor protein p53 (TP53), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), rearranged during transfection (RET), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)—and increased genetic heterogeneity follow these stimuli.6

The morphologic presentation of porocarcinoma is highly variable and may manifest as papules, nodules, or plaques in various states of erosion, ulceration, or excoriation. Diagnoses of basal and squamous cell carcinoma, primary adnexal tumors, seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, and melanoma must all be considered and methodically ruled out.7 Porocarcinomas may arise nearly anywhere on the body, with a particular predilection for the lower extremities (35%), head/neck (24%), and upper extremities (14%).3,4 Primary lesions arising from the extremities, genitalia, or buttocks herald a higher risk for lymphatic invasion and distant metastasis, while head and neck tumors more commonly remain localized.8 Bleeding, ulceration, or rapid expansion of a preexisting poroma is suggestive of malignant transformation and may portend a more aggressive disease pattern.2,9

Unequivocal diagnosis relies on histological and immunohistochemical studies due to the marked clinical variance of this neoplasm.7 An irregular histologic pattern of poromatous basaloid cells with ductal differentiation and cytologic atypia commonly are seen with porocarcinomas.2,8 Nuclear pleomorphism with cellular necrosis, increased mitotic figures, and abortive ductal formation with a distinct lack of retraction around cellular aggregates often are found. Immunohistochemical staining is needed to confirm the primary tumor diagnosis. Histochemical stains commonly employed include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, p53, p63, Ki67, and periodic acid-Schiff.10 The use of BerEP4 has been reported as efficacious in highlighting sweat structures, which can be particularly useful in cases when basal cell carcinoma is not in the histologic differential.11 These staining profiles afford confirmation of ductal differentiation with CEA, epithelial membrane antigen, and BerEP4, while p63 and Ki67 are used as surrogates for primary cutaneous neoplasia and cell proliferation, respectively.5,11 Porocarcinoma lesions may be most sensitive to CEA and most specific to CK19 (a component of cytokeratin AE1/AE3), though these findings have not been widely reproduced.7

The treatment and prognosis of porocarcinoma vary widely. Surgically excised lesions recur in roughly 20% of cases, though these rates likely include tumors that were incompletely resected in the primary attempt. Although wide local excision with an average 1-cm margin remains the most employed removal technique, Mohs micrographic surgery may more effectively limit recurrence and metastasis of localized disease.7,8,12 Metastatic disease foretells a mortality rate of at least 65%, which is problematic in that 10% to 20% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and another 20% will show metastasis following primary tumor excision.8,10 Neoplasms with high mitotic rates and depths greater than 7 mm should prompt thorough diagnostic imaging, such as positron emission tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. A sentinel lymph node biopsy should be strongly considered and discussed with the patient.10 Treatment options for nodal and distant metastases include a combination of localized surgery, lymphadenectomy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapeutic agents.2,4,5 The response to systemic treatment and radiotherapy often is quite poor, though the use of combinations of docetaxel, paclitaxel, cetuximab, and immunotherapy have been efficacious in smaller studies.8,10 The highest rates of morbidity and mortality are seen in patients with metastases on presentation or with localized tumors in the groin and buttocks.8