User login

New and Noteworthy Information—May 2013

Living in the stroke belt as an adolescent is significantly associated with a high risk of stroke, according to research published online ahead of print April 24 in Neurology. Researchers examined data for 24,544 stroke-free participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke belt exposure was calculated by combinations of stroke belt birthplace, current residence, and proportion of years in the stroke belt during discrete age categories. Risk of stroke was significantly associated with proportion of life in the stroke belt and with all other exposure periods except birth, ages 31 to 45, and current residence. After adjustment for risk factors, the risk of stroke remained significantly associated only with proportion of residence in the stroke belt during adolescence.

Increased levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a proatherosclerotic metabolite, are associated with an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death, according to research published in the April 25 New England Journal of Medicine. Investigators measured TMAO, choline, and betaine levels in patients who had eaten two hard-boiled eggs and deuterium [d9]-labeled phosphatidylcholine before and after suppressing intestinal microbiota with antibiotics. They also examined the relationship between fasting plasma levels of TMAO and major adverse cardiovascular events during three years of follow-up. Increased plasma levels of TMAO were associated with an increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event. An elevated TMAO level predicted an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after adjustment for traditional risk factors, as well as in lower-risk subgroups.

A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the ABCA7 gene was significantly linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease among African Americans, according to research published in the April 10 JAMA. African Americans with this mutation have nearly double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but the SNP is not associated with the disease among Europeans. The effect size for the SNP in ABCA7 was comparable with that of the APOE ε4–determining SNP rs429358. Investigators examined data for 5,896 African Americans (1,968 with Alzheimer’s disease and 3,928 controls) who were 60 or older. Data were collected between 1989 and 2011 at multiple sites. The team assessed the association of Alzheimer’s disease with genotyped and imputed SNPs in case–control and in family-based data sets.

The FDA has approved the Precision Spectra Spinal Cord Stimulator (SCS) System, which is designed to provide improved pain relief to patients with chronic pain. The system, manufactured by Boston Scientific (Natick, Massachusetts), includes Illumina 3D software intended to improve physicians’ control of the stimulation field. It is based on a proprietary computer model that takes into account 3-D anatomical structures, including the conductivity of the spinal cord and surrounding tissue. The physician can select a desired location on the spinal cord and prompt the programming software to create a customized stimulation field to mask the patient’s pain. Previous SCS systems included 16 contacts, but the Precision Spectra system includes 32 contacts and is designed to offer more coverage of the spinal cord.

Framingham risk scores may be better than a dementia risk score for assessing individuals’ risk of cognitive decline and targeting modifiable risk factors, according to research published in the April 2 Neurology. Researchers examined data for participants in the Whitehall II longitudinal cohort study. Subjects’ mean age at baseline was 55.6. The investigators compared the Framingham general cardiovascular disease risk score and the Framingham stroke risk score with the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia risk score. Patients underwent cognitive tests of reasoning, memory, verbal fluency, vocabulary, and global cognition three times over 10 years. Compared with the dementia risk score, cardiovascular and stroke risk scores showed slightly stronger associations with 10-year cognitive decline. The differences were statistically significant for semantic fluency and global cognitive scores.

Children born to women who used valproate during pregnancy may have a significantly increased risk of autism spectrum disorder and childhood autism, according to research published in the April 24 JAMA. Investigators used national registers to identify Danish children exposed to valproate during pregnancy and diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. The researchers analyzed the risks associated with all autism spectrum disorders, as well as childhood autism, and adjusted for potential confounders. The estimated absolute risk after 14 years of follow-up was 1.53% for autism spectrum disorder and 0.48% for childhood autism. The 508 children exposed to valproate had an absolute risk of 4.42% for autism spectrum disorder and an absolute risk of 2.50% for childhood autism. Results changed slightly after considering only the children born to women with epilepsy.

The antisense oligonucleotide ISIS 333611 is a safe treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), according to a trial published online ahead of print March 29 in Lancet Neurology. Investigators studied 32 patients with SOD1-positive ALS in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I trial. The researchers delivered the drug by intrathecal infusion using an external pump over 11.5 hours at increasing doses (0.15 mg, 0.50 mg, 1.50 mg, and 3.00 mg). Approximately 88% of patients in the placebo group had adverse events, compared with 83% in the active group. The most common events were post-lumbar puncture syndrome, back pain, and nausea. The investigators found no dose-limiting toxic effects or safety or tolerability concerns related to ISIS 333611. No serious adverse events occurred in patients given ISIS 333611.

Thalamic atrophy in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is associated with the development of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print April 23 in Radiology. Using MRI, researchers assessed 216 patients with CIS at baseline, six months, one year, and two years. MRI measures of progression included new and enlarged T2 lesions and changes in whole-brain, tissue-specific global, and regional gray matter volumes. In mixed-effect model analysis, the lateral ventricle volume, accumulation of new total T2 and new enlarging T2 lesions increase, and thalamic and whole-brain volume decrease were associated with development of clinically definite MS. In multivariate regression analysis, decrease in thalamic volumes and increase in lateral ventricle volumes were associated with the development of clinically definite MS.

Functional MRI (fMRI) can identify pain caused by heat in healthy persons, according to research published in the April 11 New England Journal of Medicine. In four studies of 114 participants, investigators developed an fMRI-based measure that predicts pain intensity, tested its sensitivity and specificity to pain versus warmth, assessed its specificity relative to social pain, and assessed the responsiveness of the measure to the analgesic remifentanil. The neurologic signature distinguished painful heat from nonpainful warmth, pain anticipation, and pain recall with sensitivity and specificity of 94% or more. The signature discriminated between painful heat and nonpainful warmth with 93% sensitivity and specificity. It also distinguished between physical pain and social pain with 85% sensitivity and 73% specificity. The strength of the signature response was substantially reduced after remifentanil administration.

Family history of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with an increased prevalence of an abnormal cerebral beta-amyloid and tau protein phenotype in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a study published on April 17 in PLOS One. Investigators studied 257 participants (ages 55 to 89) in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Subjects were categorized as cognitively normal, having MCI, or having Alzheimer’s disease. Among patients with MCI, CSF Ab42 was lower, t-tau was higher, and t-tau–Ab42 ratio was higher in patients with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease than in patients without. A significant residual effect of family history on pathologic markers in MCI remained after adjusting for APOE e4. The effect of family history was not significant in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Most potential migraine triggers are so variable that it may not be possible to identify them without formal experimentation, according to a study published in the April issue of Headache. Investigators examined the similarity of day-to-day weather conditions over four years, as well as the similarity of ovarian hormones and perceived stress over a median of 89 days in nine patients with headache and regular menstrual cycles. A threshold of 90% similarity using Gower’s index identified similar days for comparison. The day-to-day variability in the three headache triggers was substantial enough that finding two naturally similar days for which to contrast the effect of a fourth trigger (eg, drinking wine) occurred infrequently. Fluctuations in weather patterns resulted in a median of 2.3 similar days each year.

Elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and altered cholesterol homeostasis may promote neurodegeneration, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease by disrupting chromosome segregation, according to research published on April 12 in PLOS One. In a study of mice, investigators observed that high dietary cholesterol induced aneuploidy. In a separate study, the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol was associated with the accumulation of aneuploid fibroblasts, neurons, and glia in patients with Niemann-Pick C1. The researchers also observed that oxidized LDL, LDL, and cholesterol, but not high-density lipoprotein (HDL), induced chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy in cultured cells, including neuronal precursors. LDL-induced aneuploidy required the LDL receptor, but not Ab. Cholesterol treatment disrupted the structure of the mitotic spindle, providing a cell biologic mechanism for its aneugenic activity, and ethanol or calcium chelation attenuated lipoprotein-induced chromosome mis-segregation.

The incidence of dementia in central Stockholm may have decreased from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, according to research published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Investigators analyzed data from two cross-sectional surveys of people ages 75 or older. One study was conducted from 1987 to 1989 and included 1,700 participants; the other was conducted from 2001 to 2004 and included 1,575 subjects. The team inferred the incidence of dementia according to its relationship with prevalence and survival. The adjusted odds ratio of dementia in the later study versus the earlier study was 1.17. The multiadjusted hazard ratio of death in the later study versus the earlier study was 0.71 in subjects with dementia, 0.68 in those without dementia, and 0.66 in all participants.

—Erik Greb

Senior Associate Editor

Living in the stroke belt as an adolescent is significantly associated with a high risk of stroke, according to research published online ahead of print April 24 in Neurology. Researchers examined data for 24,544 stroke-free participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke belt exposure was calculated by combinations of stroke belt birthplace, current residence, and proportion of years in the stroke belt during discrete age categories. Risk of stroke was significantly associated with proportion of life in the stroke belt and with all other exposure periods except birth, ages 31 to 45, and current residence. After adjustment for risk factors, the risk of stroke remained significantly associated only with proportion of residence in the stroke belt during adolescence.

Increased levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a proatherosclerotic metabolite, are associated with an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death, according to research published in the April 25 New England Journal of Medicine. Investigators measured TMAO, choline, and betaine levels in patients who had eaten two hard-boiled eggs and deuterium [d9]-labeled phosphatidylcholine before and after suppressing intestinal microbiota with antibiotics. They also examined the relationship between fasting plasma levels of TMAO and major adverse cardiovascular events during three years of follow-up. Increased plasma levels of TMAO were associated with an increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event. An elevated TMAO level predicted an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after adjustment for traditional risk factors, as well as in lower-risk subgroups.

A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the ABCA7 gene was significantly linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease among African Americans, according to research published in the April 10 JAMA. African Americans with this mutation have nearly double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but the SNP is not associated with the disease among Europeans. The effect size for the SNP in ABCA7 was comparable with that of the APOE ε4–determining SNP rs429358. Investigators examined data for 5,896 African Americans (1,968 with Alzheimer’s disease and 3,928 controls) who were 60 or older. Data were collected between 1989 and 2011 at multiple sites. The team assessed the association of Alzheimer’s disease with genotyped and imputed SNPs in case–control and in family-based data sets.

The FDA has approved the Precision Spectra Spinal Cord Stimulator (SCS) System, which is designed to provide improved pain relief to patients with chronic pain. The system, manufactured by Boston Scientific (Natick, Massachusetts), includes Illumina 3D software intended to improve physicians’ control of the stimulation field. It is based on a proprietary computer model that takes into account 3-D anatomical structures, including the conductivity of the spinal cord and surrounding tissue. The physician can select a desired location on the spinal cord and prompt the programming software to create a customized stimulation field to mask the patient’s pain. Previous SCS systems included 16 contacts, but the Precision Spectra system includes 32 contacts and is designed to offer more coverage of the spinal cord.

Framingham risk scores may be better than a dementia risk score for assessing individuals’ risk of cognitive decline and targeting modifiable risk factors, according to research published in the April 2 Neurology. Researchers examined data for participants in the Whitehall II longitudinal cohort study. Subjects’ mean age at baseline was 55.6. The investigators compared the Framingham general cardiovascular disease risk score and the Framingham stroke risk score with the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia risk score. Patients underwent cognitive tests of reasoning, memory, verbal fluency, vocabulary, and global cognition three times over 10 years. Compared with the dementia risk score, cardiovascular and stroke risk scores showed slightly stronger associations with 10-year cognitive decline. The differences were statistically significant for semantic fluency and global cognitive scores.

Children born to women who used valproate during pregnancy may have a significantly increased risk of autism spectrum disorder and childhood autism, according to research published in the April 24 JAMA. Investigators used national registers to identify Danish children exposed to valproate during pregnancy and diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. The researchers analyzed the risks associated with all autism spectrum disorders, as well as childhood autism, and adjusted for potential confounders. The estimated absolute risk after 14 years of follow-up was 1.53% for autism spectrum disorder and 0.48% for childhood autism. The 508 children exposed to valproate had an absolute risk of 4.42% for autism spectrum disorder and an absolute risk of 2.50% for childhood autism. Results changed slightly after considering only the children born to women with epilepsy.

The antisense oligonucleotide ISIS 333611 is a safe treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), according to a trial published online ahead of print March 29 in Lancet Neurology. Investigators studied 32 patients with SOD1-positive ALS in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I trial. The researchers delivered the drug by intrathecal infusion using an external pump over 11.5 hours at increasing doses (0.15 mg, 0.50 mg, 1.50 mg, and 3.00 mg). Approximately 88% of patients in the placebo group had adverse events, compared with 83% in the active group. The most common events were post-lumbar puncture syndrome, back pain, and nausea. The investigators found no dose-limiting toxic effects or safety or tolerability concerns related to ISIS 333611. No serious adverse events occurred in patients given ISIS 333611.

Thalamic atrophy in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is associated with the development of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print April 23 in Radiology. Using MRI, researchers assessed 216 patients with CIS at baseline, six months, one year, and two years. MRI measures of progression included new and enlarged T2 lesions and changes in whole-brain, tissue-specific global, and regional gray matter volumes. In mixed-effect model analysis, the lateral ventricle volume, accumulation of new total T2 and new enlarging T2 lesions increase, and thalamic and whole-brain volume decrease were associated with development of clinically definite MS. In multivariate regression analysis, decrease in thalamic volumes and increase in lateral ventricle volumes were associated with the development of clinically definite MS.

Functional MRI (fMRI) can identify pain caused by heat in healthy persons, according to research published in the April 11 New England Journal of Medicine. In four studies of 114 participants, investigators developed an fMRI-based measure that predicts pain intensity, tested its sensitivity and specificity to pain versus warmth, assessed its specificity relative to social pain, and assessed the responsiveness of the measure to the analgesic remifentanil. The neurologic signature distinguished painful heat from nonpainful warmth, pain anticipation, and pain recall with sensitivity and specificity of 94% or more. The signature discriminated between painful heat and nonpainful warmth with 93% sensitivity and specificity. It also distinguished between physical pain and social pain with 85% sensitivity and 73% specificity. The strength of the signature response was substantially reduced after remifentanil administration.

Family history of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with an increased prevalence of an abnormal cerebral beta-amyloid and tau protein phenotype in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a study published on April 17 in PLOS One. Investigators studied 257 participants (ages 55 to 89) in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Subjects were categorized as cognitively normal, having MCI, or having Alzheimer’s disease. Among patients with MCI, CSF Ab42 was lower, t-tau was higher, and t-tau–Ab42 ratio was higher in patients with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease than in patients without. A significant residual effect of family history on pathologic markers in MCI remained after adjusting for APOE e4. The effect of family history was not significant in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Most potential migraine triggers are so variable that it may not be possible to identify them without formal experimentation, according to a study published in the April issue of Headache. Investigators examined the similarity of day-to-day weather conditions over four years, as well as the similarity of ovarian hormones and perceived stress over a median of 89 days in nine patients with headache and regular menstrual cycles. A threshold of 90% similarity using Gower’s index identified similar days for comparison. The day-to-day variability in the three headache triggers was substantial enough that finding two naturally similar days for which to contrast the effect of a fourth trigger (eg, drinking wine) occurred infrequently. Fluctuations in weather patterns resulted in a median of 2.3 similar days each year.

Elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and altered cholesterol homeostasis may promote neurodegeneration, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease by disrupting chromosome segregation, according to research published on April 12 in PLOS One. In a study of mice, investigators observed that high dietary cholesterol induced aneuploidy. In a separate study, the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol was associated with the accumulation of aneuploid fibroblasts, neurons, and glia in patients with Niemann-Pick C1. The researchers also observed that oxidized LDL, LDL, and cholesterol, but not high-density lipoprotein (HDL), induced chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy in cultured cells, including neuronal precursors. LDL-induced aneuploidy required the LDL receptor, but not Ab. Cholesterol treatment disrupted the structure of the mitotic spindle, providing a cell biologic mechanism for its aneugenic activity, and ethanol or calcium chelation attenuated lipoprotein-induced chromosome mis-segregation.

The incidence of dementia in central Stockholm may have decreased from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, according to research published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Investigators analyzed data from two cross-sectional surveys of people ages 75 or older. One study was conducted from 1987 to 1989 and included 1,700 participants; the other was conducted from 2001 to 2004 and included 1,575 subjects. The team inferred the incidence of dementia according to its relationship with prevalence and survival. The adjusted odds ratio of dementia in the later study versus the earlier study was 1.17. The multiadjusted hazard ratio of death in the later study versus the earlier study was 0.71 in subjects with dementia, 0.68 in those without dementia, and 0.66 in all participants.

—Erik Greb

Senior Associate Editor

Living in the stroke belt as an adolescent is significantly associated with a high risk of stroke, according to research published online ahead of print April 24 in Neurology. Researchers examined data for 24,544 stroke-free participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke belt exposure was calculated by combinations of stroke belt birthplace, current residence, and proportion of years in the stroke belt during discrete age categories. Risk of stroke was significantly associated with proportion of life in the stroke belt and with all other exposure periods except birth, ages 31 to 45, and current residence. After adjustment for risk factors, the risk of stroke remained significantly associated only with proportion of residence in the stroke belt during adolescence.

Increased levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a proatherosclerotic metabolite, are associated with an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death, according to research published in the April 25 New England Journal of Medicine. Investigators measured TMAO, choline, and betaine levels in patients who had eaten two hard-boiled eggs and deuterium [d9]-labeled phosphatidylcholine before and after suppressing intestinal microbiota with antibiotics. They also examined the relationship between fasting plasma levels of TMAO and major adverse cardiovascular events during three years of follow-up. Increased plasma levels of TMAO were associated with an increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event. An elevated TMAO level predicted an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after adjustment for traditional risk factors, as well as in lower-risk subgroups.

A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the ABCA7 gene was significantly linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease among African Americans, according to research published in the April 10 JAMA. African Americans with this mutation have nearly double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but the SNP is not associated with the disease among Europeans. The effect size for the SNP in ABCA7 was comparable with that of the APOE ε4–determining SNP rs429358. Investigators examined data for 5,896 African Americans (1,968 with Alzheimer’s disease and 3,928 controls) who were 60 or older. Data were collected between 1989 and 2011 at multiple sites. The team assessed the association of Alzheimer’s disease with genotyped and imputed SNPs in case–control and in family-based data sets.

The FDA has approved the Precision Spectra Spinal Cord Stimulator (SCS) System, which is designed to provide improved pain relief to patients with chronic pain. The system, manufactured by Boston Scientific (Natick, Massachusetts), includes Illumina 3D software intended to improve physicians’ control of the stimulation field. It is based on a proprietary computer model that takes into account 3-D anatomical structures, including the conductivity of the spinal cord and surrounding tissue. The physician can select a desired location on the spinal cord and prompt the programming software to create a customized stimulation field to mask the patient’s pain. Previous SCS systems included 16 contacts, but the Precision Spectra system includes 32 contacts and is designed to offer more coverage of the spinal cord.

Framingham risk scores may be better than a dementia risk score for assessing individuals’ risk of cognitive decline and targeting modifiable risk factors, according to research published in the April 2 Neurology. Researchers examined data for participants in the Whitehall II longitudinal cohort study. Subjects’ mean age at baseline was 55.6. The investigators compared the Framingham general cardiovascular disease risk score and the Framingham stroke risk score with the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia risk score. Patients underwent cognitive tests of reasoning, memory, verbal fluency, vocabulary, and global cognition three times over 10 years. Compared with the dementia risk score, cardiovascular and stroke risk scores showed slightly stronger associations with 10-year cognitive decline. The differences were statistically significant for semantic fluency and global cognitive scores.

Children born to women who used valproate during pregnancy may have a significantly increased risk of autism spectrum disorder and childhood autism, according to research published in the April 24 JAMA. Investigators used national registers to identify Danish children exposed to valproate during pregnancy and diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. The researchers analyzed the risks associated with all autism spectrum disorders, as well as childhood autism, and adjusted for potential confounders. The estimated absolute risk after 14 years of follow-up was 1.53% for autism spectrum disorder and 0.48% for childhood autism. The 508 children exposed to valproate had an absolute risk of 4.42% for autism spectrum disorder and an absolute risk of 2.50% for childhood autism. Results changed slightly after considering only the children born to women with epilepsy.

The antisense oligonucleotide ISIS 333611 is a safe treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), according to a trial published online ahead of print March 29 in Lancet Neurology. Investigators studied 32 patients with SOD1-positive ALS in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I trial. The researchers delivered the drug by intrathecal infusion using an external pump over 11.5 hours at increasing doses (0.15 mg, 0.50 mg, 1.50 mg, and 3.00 mg). Approximately 88% of patients in the placebo group had adverse events, compared with 83% in the active group. The most common events were post-lumbar puncture syndrome, back pain, and nausea. The investigators found no dose-limiting toxic effects or safety or tolerability concerns related to ISIS 333611. No serious adverse events occurred in patients given ISIS 333611.

Thalamic atrophy in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is associated with the development of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a study published online ahead of print April 23 in Radiology. Using MRI, researchers assessed 216 patients with CIS at baseline, six months, one year, and two years. MRI measures of progression included new and enlarged T2 lesions and changes in whole-brain, tissue-specific global, and regional gray matter volumes. In mixed-effect model analysis, the lateral ventricle volume, accumulation of new total T2 and new enlarging T2 lesions increase, and thalamic and whole-brain volume decrease were associated with development of clinically definite MS. In multivariate regression analysis, decrease in thalamic volumes and increase in lateral ventricle volumes were associated with the development of clinically definite MS.

Functional MRI (fMRI) can identify pain caused by heat in healthy persons, according to research published in the April 11 New England Journal of Medicine. In four studies of 114 participants, investigators developed an fMRI-based measure that predicts pain intensity, tested its sensitivity and specificity to pain versus warmth, assessed its specificity relative to social pain, and assessed the responsiveness of the measure to the analgesic remifentanil. The neurologic signature distinguished painful heat from nonpainful warmth, pain anticipation, and pain recall with sensitivity and specificity of 94% or more. The signature discriminated between painful heat and nonpainful warmth with 93% sensitivity and specificity. It also distinguished between physical pain and social pain with 85% sensitivity and 73% specificity. The strength of the signature response was substantially reduced after remifentanil administration.

Family history of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with an increased prevalence of an abnormal cerebral beta-amyloid and tau protein phenotype in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a study published on April 17 in PLOS One. Investigators studied 257 participants (ages 55 to 89) in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Subjects were categorized as cognitively normal, having MCI, or having Alzheimer’s disease. Among patients with MCI, CSF Ab42 was lower, t-tau was higher, and t-tau–Ab42 ratio was higher in patients with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease than in patients without. A significant residual effect of family history on pathologic markers in MCI remained after adjusting for APOE e4. The effect of family history was not significant in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Most potential migraine triggers are so variable that it may not be possible to identify them without formal experimentation, according to a study published in the April issue of Headache. Investigators examined the similarity of day-to-day weather conditions over four years, as well as the similarity of ovarian hormones and perceived stress over a median of 89 days in nine patients with headache and regular menstrual cycles. A threshold of 90% similarity using Gower’s index identified similar days for comparison. The day-to-day variability in the three headache triggers was substantial enough that finding two naturally similar days for which to contrast the effect of a fourth trigger (eg, drinking wine) occurred infrequently. Fluctuations in weather patterns resulted in a median of 2.3 similar days each year.

Elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and altered cholesterol homeostasis may promote neurodegeneration, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease by disrupting chromosome segregation, according to research published on April 12 in PLOS One. In a study of mice, investigators observed that high dietary cholesterol induced aneuploidy. In a separate study, the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol was associated with the accumulation of aneuploid fibroblasts, neurons, and glia in patients with Niemann-Pick C1. The researchers also observed that oxidized LDL, LDL, and cholesterol, but not high-density lipoprotein (HDL), induced chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy in cultured cells, including neuronal precursors. LDL-induced aneuploidy required the LDL receptor, but not Ab. Cholesterol treatment disrupted the structure of the mitotic spindle, providing a cell biologic mechanism for its aneugenic activity, and ethanol or calcium chelation attenuated lipoprotein-induced chromosome mis-segregation.

The incidence of dementia in central Stockholm may have decreased from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, according to research published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Investigators analyzed data from two cross-sectional surveys of people ages 75 or older. One study was conducted from 1987 to 1989 and included 1,700 participants; the other was conducted from 2001 to 2004 and included 1,575 subjects. The team inferred the incidence of dementia according to its relationship with prevalence and survival. The adjusted odds ratio of dementia in the later study versus the earlier study was 1.17. The multiadjusted hazard ratio of death in the later study versus the earlier study was 0.71 in subjects with dementia, 0.68 in those without dementia, and 0.66 in all participants.

—Erik Greb

Senior Associate Editor

Promoting Professionalism

Unprofessional behavior in the inpatient setting has the potential to impact care delivery and the quality of trainee's educational experience. These behaviors, from disparaging colleagues to blocking admissions, can negatively impact the learning environment. The learning environment or conditions created by the patient care team's actions play a critical role in the development of trainees.[1, 2] The rising presence of hospitalists in the inpatient setting raises the question of how their actions impact the learning environment. Professional behavior has been defined as a core competency for hospitalists by the Society of Hospital Medicine.[3] Professional behavior of all team members, from faculty to trainee, can impact the learning environment and patient safety.[4, 5] However, few educational materials exist to train faculty and housestaff on recognizing and ameliorating unprofessional behaviors.

A prior assessment regarding hospitalists' lapses in professionalism identified scenarios that demonstrated increased participation by hospitalists at 3 institutions.[6] Participants reported observation or participation in specific unprofessional behaviors and rated their perception of these behaviors. Additional work within those residency environments demonstrated that residents' perceptions of and participation in these behaviors increased throughout training, with environmental characteristics, specifically faculty behavior, influencing trainee professional development and acclimation of these behaviors.[7, 8]

Although overall participation in egregious behavior was low, resident participation in 3 categories of unprofessional behavior increased during internship. Those scenarios included disparaging the emergency room or primary care physician for missed findings or management decisions, blocking or not taking admissions appropriate for the service in question, and misrepresenting a test as urgent to expedite obtaining the test. We developed our intervention focused on these areas to address professionalism lapses that occur during internship. Our earlier work showed faculty role models influenced trainee behavior. For this reason, we provided education to both residents and hospitalists to maximize the impact of the intervention.

We present here a novel, interactive, video‐based workshop curriculum for faculty and trainees that aims to illustrate unprofessional behaviors and outlines the role faculty may play in promoting such behaviors. In addition, we review the result of postworkshop evaluation on intent to change behavior and satisfaction.

METHODS

A grant from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation supported this project. The working group that resulted, the Chicago Professional Practice Project and Outcomes, included faculty representation from 3 Chicago‐area hospitals: the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and NorthShore University HealthSystem. Academic hospitalists at these sites were invited to participate. Each site also has an internal medicine residency program in which hospitalists were expected to attend the teaching service. Given this, resident trainees at all participating sites, and 1 community teaching affiliate program (Mercy Hospital and Medical Center) where academic hospitalists at the University of Chicago rotate, were recruited for participation. Faculty champions were identified for each site, and 1 internal and external faculty representative from the working group served to debrief and facilitate. Trainee workshops were administered by 1 internal and external collaborator, and for the community site, 2 external faculty members. Workshops were held during established educational conference times, and lunch was provided.

Scripts highlighting each of the behaviors identified in the prior survey were developed and peer reviewed for clarity and face validity across the 3 sites. Medical student and resident actors were trained utilizing the finalized scripts, and a performance artist affiliated with the Screen Actors Guild assisted in their preparation for filming. All videos were filmed at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Clinical Performance Center. The final videos ranged in length from 4 to 7 minutes and included title, cast, and funding source. As an example, 1 video highlighted the unprofessional behavior of misrepresenting a test as urgent to prioritize one's patient in the queue. This video included a resident, intern, and attending on inpatient rounds during which the resident encouraged the intern to misrepresent the patient's status to expedite obtaining the study and facilitate the patient's discharge. The resident stressed that he would be in the clinic and had many patients to see, highlighting the impact of workload on unprofessional behavior, and aggressively persuaded the intern to sell her test to have it performed the same day. When this occurred, the attending applauded the intern for her strong work.

A moderator guide and debriefing tools were developed to facilitate discussion. The duration of each of the workshops was approximately 60 minutes. After welcoming remarks, participants were provided tools to utilize during the viewing of each video. These checklists noted the roles of those depicted in the video, asked to identify positive or negative behaviors displayed, and included questions regarding how behaviors could be detrimental and how the situation could have been prevented. After viewing the videos, participants divided into small groups to discuss the individual exhibiting the unprofessional behavior, their perceived motivation for said behavior, and its impact on the team culture and patient care. Following a small‐group discussion, large‐group debriefing was performed, addressing the barriers and facilitators to professional behavior. Two videos were shown at each workshop, and participants completed a postworkshop evaluation. Videos chosen for viewing were based upon preworkshop survey results that highlighted areas of concern at that specific site.

Postworkshop paper‐based evaluations assessed participants' perception of displayed behaviors on a Likert‐type scale (1=unprofessional to 5=professional) utilizing items validated in prior work,[6, 7, 8] their level of agreement regarding the impact of video‐based exercises, and intent to change behavior using a Likert‐type scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). A constructed‐response section for comments regarding their experience was included. Descriptive statistics and Wilcoxon rank sum analyses were performed.

RESULTS

Forty‐four academic hospitalist faculty members (44/83; 53%) and 244 resident trainees (244/356; 68%) participated. When queried regarding their perception of the displayed behaviors in the videos, nearly 100% of faculty and trainees felt disparaging the emergency department or primary care physician for missed findings or clinical decisions was somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional. Ninety percent of hospitalists and 93% of trainees rated celebrating a blocked admission as somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional (Table 1).

| Behavior | Faculty Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n = 44) | Housestaff Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Disparaging the ED/PCP to colleagues for findings later discovered on the floor or patient care management decisions | 95.6% | 97.5% |

| Refusing an admission that could be considered appropriate for your service (eg, blocking) | 86.4% | 95.1% |

| Celebrating a blocked admission | 90.1% | 93.0% |

| Ordering a routine test as urgent to get it expedited | 77.2% | 80.3% |

The scenarios portrayed were well received, with more than 85% of faculty and trainees agreeing that the behaviors displayed were realistic. Those who perceived videos as very realistic were more likely to report intent to change behavior (93% vs 53%, P=0.01). Nearly two‐thirds of faculty and 67% of housestaff expressed agreement that they intended to change behavior based upon the experience (Table 2).

| Evaluation Item | Faculty Level of Agreement (StronglyAgree or Agree) (n=44) | Housestaff Level of Agreement (Strongly Agree or Agree) (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| The scenarios portrayed in the videos were realistic | 86.4% | 86.9% |

| I will change my behavior as a result of this exercise | 65.9% | 67.2% |

| I feel that this was a useful and effective exercise | 65.9% | 77.1% |

Qualitative comments in the constructed‐response portion of the evaluation noted the effectiveness of the interactive materials. In addition, the need for focused faculty development was identified by 1 respondent who stated: If unprofessional behavior is the unwritten curriculum, there needs to be an explicit, written curriculum to address it. Finally, the aim of facilitating self‐reflection is echoed in this faculty respondent's comment: Always good to be reminded of our behaviors and the influence they have on others and from this resident physician It helps to re‐evaluate how you talk to people.

CONCLUSIONS

Faculty can be a large determinant of the learning environment and impact trainees' professional development.[9] Hospitalists should be encouraged to embrace faculty role‐modeling of effective professional behaviors, especially given their increased presence in the inpatient learning environment. In addition, resident trainees and their behaviors contribute to the learning environment and influence the further professional development of more junior trainees.[10] Targeting professionalism education toward previously identified and prevalent unprofessional behaviors in the inpatient care of patients may serve to affect the most change among providers who practice in this setting. Individualized assessment of the learning environment may aid in identifying common scenarios that may plague a specific learning culture, allowing for relevant and targeted discussion of factors that promote and perpetuate such behaviors.[11]

Interactive, video‐based modules provided an effective way to promote interactive reflection and robust discussion. This model of experiential learning is an effective form of professional development as it engages the learner and stimulates ongoing incorporation of the topics addressed.[12, 13] Creating a shared concrete experience among targeted learners, using the video‐based scenarios, stimulates reflective observation, and ultimately experimentation, or incorporation into practice.[14]

There are several limitations to our evaluation including that we focused solely on academic hospitalist programs, and our sample size for faculty and residents was small. Also, we only addressed a small, though representative, sample of unprofessional behaviors and have not yet linked intervention to actual behavior change. Finally, the script scenarios that we used in this study were not previously published as they were created specifically for this intervention. Validity evidence for these scenarios include that they were based upon the results of earlier work from our institutions and underwent thorough peer review for content and clarity. Further studies will be required to do this. However, we do believe that these are positive findings for utilizing this type of interactive curriculum for professionalism education to promote self‐reflection and behavior change.

Video‐based professionalism education is a feasible, interactive mechanism to encourage self‐reflection and intent to change behavior among faculty and resident physicians. Future study is underway to conduct longitudinal assessments of the learning environments at the participating institutions to assess culture change, perceptions of behaviors, and sustainability of this type of intervention.

Disclosures: The authors acknowledge funding from the American Board of Internal Medicine. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Results from this work have been presented at the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, September 2011; Midwest Society of Hospital Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, October 2011, and Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 2012. The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/functions.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , , , , . Residents' perceptions of their own professionalism and the professionalism of their learning environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:208–215.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- The Joint Commission. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert. 2008;(40):1–3. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_40.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , . A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471.

- , , , et al. Participation in unprofessional behaviors among hospitalists: a multicenter study. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):543–550.

- , , et al. Participation in and perceptions of unprofessional behaviors among incoming internal medicine interns. JAMA. 2008;300:1132–1134.

- , , , et al., Changes in perception of and participation in unprofessional behaviors during internship. Acad Med. 2010;85:S76–S80.

- , , , et al. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , . The role of the student‐teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–S20.

- , , , et al. Evidence for validity of a survey to measure the learning environment for professionalism. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e683–e688.

- . Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

- , . How can physicians' learning style drive educational planning? Acad Med. 2005;80:680–84.

- , . Twenty years of experience using trigger films as a teaching tool. Acad Med. 2001;76:656–658.

Unprofessional behavior in the inpatient setting has the potential to impact care delivery and the quality of trainee's educational experience. These behaviors, from disparaging colleagues to blocking admissions, can negatively impact the learning environment. The learning environment or conditions created by the patient care team's actions play a critical role in the development of trainees.[1, 2] The rising presence of hospitalists in the inpatient setting raises the question of how their actions impact the learning environment. Professional behavior has been defined as a core competency for hospitalists by the Society of Hospital Medicine.[3] Professional behavior of all team members, from faculty to trainee, can impact the learning environment and patient safety.[4, 5] However, few educational materials exist to train faculty and housestaff on recognizing and ameliorating unprofessional behaviors.

A prior assessment regarding hospitalists' lapses in professionalism identified scenarios that demonstrated increased participation by hospitalists at 3 institutions.[6] Participants reported observation or participation in specific unprofessional behaviors and rated their perception of these behaviors. Additional work within those residency environments demonstrated that residents' perceptions of and participation in these behaviors increased throughout training, with environmental characteristics, specifically faculty behavior, influencing trainee professional development and acclimation of these behaviors.[7, 8]

Although overall participation in egregious behavior was low, resident participation in 3 categories of unprofessional behavior increased during internship. Those scenarios included disparaging the emergency room or primary care physician for missed findings or management decisions, blocking or not taking admissions appropriate for the service in question, and misrepresenting a test as urgent to expedite obtaining the test. We developed our intervention focused on these areas to address professionalism lapses that occur during internship. Our earlier work showed faculty role models influenced trainee behavior. For this reason, we provided education to both residents and hospitalists to maximize the impact of the intervention.

We present here a novel, interactive, video‐based workshop curriculum for faculty and trainees that aims to illustrate unprofessional behaviors and outlines the role faculty may play in promoting such behaviors. In addition, we review the result of postworkshop evaluation on intent to change behavior and satisfaction.

METHODS

A grant from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation supported this project. The working group that resulted, the Chicago Professional Practice Project and Outcomes, included faculty representation from 3 Chicago‐area hospitals: the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and NorthShore University HealthSystem. Academic hospitalists at these sites were invited to participate. Each site also has an internal medicine residency program in which hospitalists were expected to attend the teaching service. Given this, resident trainees at all participating sites, and 1 community teaching affiliate program (Mercy Hospital and Medical Center) where academic hospitalists at the University of Chicago rotate, were recruited for participation. Faculty champions were identified for each site, and 1 internal and external faculty representative from the working group served to debrief and facilitate. Trainee workshops were administered by 1 internal and external collaborator, and for the community site, 2 external faculty members. Workshops were held during established educational conference times, and lunch was provided.

Scripts highlighting each of the behaviors identified in the prior survey were developed and peer reviewed for clarity and face validity across the 3 sites. Medical student and resident actors were trained utilizing the finalized scripts, and a performance artist affiliated with the Screen Actors Guild assisted in their preparation for filming. All videos were filmed at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Clinical Performance Center. The final videos ranged in length from 4 to 7 minutes and included title, cast, and funding source. As an example, 1 video highlighted the unprofessional behavior of misrepresenting a test as urgent to prioritize one's patient in the queue. This video included a resident, intern, and attending on inpatient rounds during which the resident encouraged the intern to misrepresent the patient's status to expedite obtaining the study and facilitate the patient's discharge. The resident stressed that he would be in the clinic and had many patients to see, highlighting the impact of workload on unprofessional behavior, and aggressively persuaded the intern to sell her test to have it performed the same day. When this occurred, the attending applauded the intern for her strong work.

A moderator guide and debriefing tools were developed to facilitate discussion. The duration of each of the workshops was approximately 60 minutes. After welcoming remarks, participants were provided tools to utilize during the viewing of each video. These checklists noted the roles of those depicted in the video, asked to identify positive or negative behaviors displayed, and included questions regarding how behaviors could be detrimental and how the situation could have been prevented. After viewing the videos, participants divided into small groups to discuss the individual exhibiting the unprofessional behavior, their perceived motivation for said behavior, and its impact on the team culture and patient care. Following a small‐group discussion, large‐group debriefing was performed, addressing the barriers and facilitators to professional behavior. Two videos were shown at each workshop, and participants completed a postworkshop evaluation. Videos chosen for viewing were based upon preworkshop survey results that highlighted areas of concern at that specific site.

Postworkshop paper‐based evaluations assessed participants' perception of displayed behaviors on a Likert‐type scale (1=unprofessional to 5=professional) utilizing items validated in prior work,[6, 7, 8] their level of agreement regarding the impact of video‐based exercises, and intent to change behavior using a Likert‐type scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). A constructed‐response section for comments regarding their experience was included. Descriptive statistics and Wilcoxon rank sum analyses were performed.

RESULTS

Forty‐four academic hospitalist faculty members (44/83; 53%) and 244 resident trainees (244/356; 68%) participated. When queried regarding their perception of the displayed behaviors in the videos, nearly 100% of faculty and trainees felt disparaging the emergency department or primary care physician for missed findings or clinical decisions was somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional. Ninety percent of hospitalists and 93% of trainees rated celebrating a blocked admission as somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional (Table 1).

| Behavior | Faculty Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n = 44) | Housestaff Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Disparaging the ED/PCP to colleagues for findings later discovered on the floor or patient care management decisions | 95.6% | 97.5% |

| Refusing an admission that could be considered appropriate for your service (eg, blocking) | 86.4% | 95.1% |

| Celebrating a blocked admission | 90.1% | 93.0% |

| Ordering a routine test as urgent to get it expedited | 77.2% | 80.3% |

The scenarios portrayed were well received, with more than 85% of faculty and trainees agreeing that the behaviors displayed were realistic. Those who perceived videos as very realistic were more likely to report intent to change behavior (93% vs 53%, P=0.01). Nearly two‐thirds of faculty and 67% of housestaff expressed agreement that they intended to change behavior based upon the experience (Table 2).

| Evaluation Item | Faculty Level of Agreement (StronglyAgree or Agree) (n=44) | Housestaff Level of Agreement (Strongly Agree or Agree) (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| The scenarios portrayed in the videos were realistic | 86.4% | 86.9% |

| I will change my behavior as a result of this exercise | 65.9% | 67.2% |

| I feel that this was a useful and effective exercise | 65.9% | 77.1% |

Qualitative comments in the constructed‐response portion of the evaluation noted the effectiveness of the interactive materials. In addition, the need for focused faculty development was identified by 1 respondent who stated: If unprofessional behavior is the unwritten curriculum, there needs to be an explicit, written curriculum to address it. Finally, the aim of facilitating self‐reflection is echoed in this faculty respondent's comment: Always good to be reminded of our behaviors and the influence they have on others and from this resident physician It helps to re‐evaluate how you talk to people.

CONCLUSIONS

Faculty can be a large determinant of the learning environment and impact trainees' professional development.[9] Hospitalists should be encouraged to embrace faculty role‐modeling of effective professional behaviors, especially given their increased presence in the inpatient learning environment. In addition, resident trainees and their behaviors contribute to the learning environment and influence the further professional development of more junior trainees.[10] Targeting professionalism education toward previously identified and prevalent unprofessional behaviors in the inpatient care of patients may serve to affect the most change among providers who practice in this setting. Individualized assessment of the learning environment may aid in identifying common scenarios that may plague a specific learning culture, allowing for relevant and targeted discussion of factors that promote and perpetuate such behaviors.[11]

Interactive, video‐based modules provided an effective way to promote interactive reflection and robust discussion. This model of experiential learning is an effective form of professional development as it engages the learner and stimulates ongoing incorporation of the topics addressed.[12, 13] Creating a shared concrete experience among targeted learners, using the video‐based scenarios, stimulates reflective observation, and ultimately experimentation, or incorporation into practice.[14]

There are several limitations to our evaluation including that we focused solely on academic hospitalist programs, and our sample size for faculty and residents was small. Also, we only addressed a small, though representative, sample of unprofessional behaviors and have not yet linked intervention to actual behavior change. Finally, the script scenarios that we used in this study were not previously published as they were created specifically for this intervention. Validity evidence for these scenarios include that they were based upon the results of earlier work from our institutions and underwent thorough peer review for content and clarity. Further studies will be required to do this. However, we do believe that these are positive findings for utilizing this type of interactive curriculum for professionalism education to promote self‐reflection and behavior change.

Video‐based professionalism education is a feasible, interactive mechanism to encourage self‐reflection and intent to change behavior among faculty and resident physicians. Future study is underway to conduct longitudinal assessments of the learning environments at the participating institutions to assess culture change, perceptions of behaviors, and sustainability of this type of intervention.

Disclosures: The authors acknowledge funding from the American Board of Internal Medicine. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Results from this work have been presented at the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, September 2011; Midwest Society of Hospital Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, October 2011, and Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 2012. The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Unprofessional behavior in the inpatient setting has the potential to impact care delivery and the quality of trainee's educational experience. These behaviors, from disparaging colleagues to blocking admissions, can negatively impact the learning environment. The learning environment or conditions created by the patient care team's actions play a critical role in the development of trainees.[1, 2] The rising presence of hospitalists in the inpatient setting raises the question of how their actions impact the learning environment. Professional behavior has been defined as a core competency for hospitalists by the Society of Hospital Medicine.[3] Professional behavior of all team members, from faculty to trainee, can impact the learning environment and patient safety.[4, 5] However, few educational materials exist to train faculty and housestaff on recognizing and ameliorating unprofessional behaviors.

A prior assessment regarding hospitalists' lapses in professionalism identified scenarios that demonstrated increased participation by hospitalists at 3 institutions.[6] Participants reported observation or participation in specific unprofessional behaviors and rated their perception of these behaviors. Additional work within those residency environments demonstrated that residents' perceptions of and participation in these behaviors increased throughout training, with environmental characteristics, specifically faculty behavior, influencing trainee professional development and acclimation of these behaviors.[7, 8]

Although overall participation in egregious behavior was low, resident participation in 3 categories of unprofessional behavior increased during internship. Those scenarios included disparaging the emergency room or primary care physician for missed findings or management decisions, blocking or not taking admissions appropriate for the service in question, and misrepresenting a test as urgent to expedite obtaining the test. We developed our intervention focused on these areas to address professionalism lapses that occur during internship. Our earlier work showed faculty role models influenced trainee behavior. For this reason, we provided education to both residents and hospitalists to maximize the impact of the intervention.

We present here a novel, interactive, video‐based workshop curriculum for faculty and trainees that aims to illustrate unprofessional behaviors and outlines the role faculty may play in promoting such behaviors. In addition, we review the result of postworkshop evaluation on intent to change behavior and satisfaction.

METHODS

A grant from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation supported this project. The working group that resulted, the Chicago Professional Practice Project and Outcomes, included faculty representation from 3 Chicago‐area hospitals: the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and NorthShore University HealthSystem. Academic hospitalists at these sites were invited to participate. Each site also has an internal medicine residency program in which hospitalists were expected to attend the teaching service. Given this, resident trainees at all participating sites, and 1 community teaching affiliate program (Mercy Hospital and Medical Center) where academic hospitalists at the University of Chicago rotate, were recruited for participation. Faculty champions were identified for each site, and 1 internal and external faculty representative from the working group served to debrief and facilitate. Trainee workshops were administered by 1 internal and external collaborator, and for the community site, 2 external faculty members. Workshops were held during established educational conference times, and lunch was provided.

Scripts highlighting each of the behaviors identified in the prior survey were developed and peer reviewed for clarity and face validity across the 3 sites. Medical student and resident actors were trained utilizing the finalized scripts, and a performance artist affiliated with the Screen Actors Guild assisted in their preparation for filming. All videos were filmed at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Clinical Performance Center. The final videos ranged in length from 4 to 7 minutes and included title, cast, and funding source. As an example, 1 video highlighted the unprofessional behavior of misrepresenting a test as urgent to prioritize one's patient in the queue. This video included a resident, intern, and attending on inpatient rounds during which the resident encouraged the intern to misrepresent the patient's status to expedite obtaining the study and facilitate the patient's discharge. The resident stressed that he would be in the clinic and had many patients to see, highlighting the impact of workload on unprofessional behavior, and aggressively persuaded the intern to sell her test to have it performed the same day. When this occurred, the attending applauded the intern for her strong work.

A moderator guide and debriefing tools were developed to facilitate discussion. The duration of each of the workshops was approximately 60 minutes. After welcoming remarks, participants were provided tools to utilize during the viewing of each video. These checklists noted the roles of those depicted in the video, asked to identify positive or negative behaviors displayed, and included questions regarding how behaviors could be detrimental and how the situation could have been prevented. After viewing the videos, participants divided into small groups to discuss the individual exhibiting the unprofessional behavior, their perceived motivation for said behavior, and its impact on the team culture and patient care. Following a small‐group discussion, large‐group debriefing was performed, addressing the barriers and facilitators to professional behavior. Two videos were shown at each workshop, and participants completed a postworkshop evaluation. Videos chosen for viewing were based upon preworkshop survey results that highlighted areas of concern at that specific site.

Postworkshop paper‐based evaluations assessed participants' perception of displayed behaviors on a Likert‐type scale (1=unprofessional to 5=professional) utilizing items validated in prior work,[6, 7, 8] their level of agreement regarding the impact of video‐based exercises, and intent to change behavior using a Likert‐type scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). A constructed‐response section for comments regarding their experience was included. Descriptive statistics and Wilcoxon rank sum analyses were performed.

RESULTS

Forty‐four academic hospitalist faculty members (44/83; 53%) and 244 resident trainees (244/356; 68%) participated. When queried regarding their perception of the displayed behaviors in the videos, nearly 100% of faculty and trainees felt disparaging the emergency department or primary care physician for missed findings or clinical decisions was somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional. Ninety percent of hospitalists and 93% of trainees rated celebrating a blocked admission as somewhat unprofessional or unprofessional (Table 1).

| Behavior | Faculty Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n = 44) | Housestaff Rated as Unprofessional or Somewhat Unprofessional (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Disparaging the ED/PCP to colleagues for findings later discovered on the floor or patient care management decisions | 95.6% | 97.5% |

| Refusing an admission that could be considered appropriate for your service (eg, blocking) | 86.4% | 95.1% |

| Celebrating a blocked admission | 90.1% | 93.0% |

| Ordering a routine test as urgent to get it expedited | 77.2% | 80.3% |

The scenarios portrayed were well received, with more than 85% of faculty and trainees agreeing that the behaviors displayed were realistic. Those who perceived videos as very realistic were more likely to report intent to change behavior (93% vs 53%, P=0.01). Nearly two‐thirds of faculty and 67% of housestaff expressed agreement that they intended to change behavior based upon the experience (Table 2).

| Evaluation Item | Faculty Level of Agreement (StronglyAgree or Agree) (n=44) | Housestaff Level of Agreement (Strongly Agree or Agree) (n=244) |

|---|---|---|

| The scenarios portrayed in the videos were realistic | 86.4% | 86.9% |

| I will change my behavior as a result of this exercise | 65.9% | 67.2% |

| I feel that this was a useful and effective exercise | 65.9% | 77.1% |

Qualitative comments in the constructed‐response portion of the evaluation noted the effectiveness of the interactive materials. In addition, the need for focused faculty development was identified by 1 respondent who stated: If unprofessional behavior is the unwritten curriculum, there needs to be an explicit, written curriculum to address it. Finally, the aim of facilitating self‐reflection is echoed in this faculty respondent's comment: Always good to be reminded of our behaviors and the influence they have on others and from this resident physician It helps to re‐evaluate how you talk to people.

CONCLUSIONS

Faculty can be a large determinant of the learning environment and impact trainees' professional development.[9] Hospitalists should be encouraged to embrace faculty role‐modeling of effective professional behaviors, especially given their increased presence in the inpatient learning environment. In addition, resident trainees and their behaviors contribute to the learning environment and influence the further professional development of more junior trainees.[10] Targeting professionalism education toward previously identified and prevalent unprofessional behaviors in the inpatient care of patients may serve to affect the most change among providers who practice in this setting. Individualized assessment of the learning environment may aid in identifying common scenarios that may plague a specific learning culture, allowing for relevant and targeted discussion of factors that promote and perpetuate such behaviors.[11]

Interactive, video‐based modules provided an effective way to promote interactive reflection and robust discussion. This model of experiential learning is an effective form of professional development as it engages the learner and stimulates ongoing incorporation of the topics addressed.[12, 13] Creating a shared concrete experience among targeted learners, using the video‐based scenarios, stimulates reflective observation, and ultimately experimentation, or incorporation into practice.[14]

There are several limitations to our evaluation including that we focused solely on academic hospitalist programs, and our sample size for faculty and residents was small. Also, we only addressed a small, though representative, sample of unprofessional behaviors and have not yet linked intervention to actual behavior change. Finally, the script scenarios that we used in this study were not previously published as they were created specifically for this intervention. Validity evidence for these scenarios include that they were based upon the results of earlier work from our institutions and underwent thorough peer review for content and clarity. Further studies will be required to do this. However, we do believe that these are positive findings for utilizing this type of interactive curriculum for professionalism education to promote self‐reflection and behavior change.

Video‐based professionalism education is a feasible, interactive mechanism to encourage self‐reflection and intent to change behavior among faculty and resident physicians. Future study is underway to conduct longitudinal assessments of the learning environments at the participating institutions to assess culture change, perceptions of behaviors, and sustainability of this type of intervention.

Disclosures: The authors acknowledge funding from the American Board of Internal Medicine. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Results from this work have been presented at the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, September 2011; Midwest Society of Hospital Medicine Regional Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, October 2011, and Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 2012. The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/functions.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , , , , . Residents' perceptions of their own professionalism and the professionalism of their learning environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:208–215.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- The Joint Commission. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert. 2008;(40):1–3. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_40.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , . A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471.

- , , , et al. Participation in unprofessional behaviors among hospitalists: a multicenter study. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):543–550.

- , , et al. Participation in and perceptions of unprofessional behaviors among incoming internal medicine interns. JAMA. 2008;300:1132–1134.

- , , , et al., Changes in perception of and participation in unprofessional behaviors during internship. Acad Med. 2010;85:S76–S80.

- , , , et al. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , . The role of the student‐teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–S20.

- , , , et al. Evidence for validity of a survey to measure the learning environment for professionalism. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e683–e688.

- . Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

- , . How can physicians' learning style drive educational planning? Acad Med. 2005;80:680–84.

- , . Twenty years of experience using trigger films as a teaching tool. Acad Med. 2001;76:656–658.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/functions.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , , , , . Residents' perceptions of their own professionalism and the professionalism of their learning environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:208–215.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- The Joint Commission. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert. 2008;(40):1–3. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_40.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- , . A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471.

- , , , et al. Participation in unprofessional behaviors among hospitalists: a multicenter study. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):543–550.

- , , et al. Participation in and perceptions of unprofessional behaviors among incoming internal medicine interns. JAMA. 2008;300:1132–1134.

- , , , et al., Changes in perception of and participation in unprofessional behaviors during internship. Acad Med. 2010;85:S76–S80.

- , , , et al. Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , . The role of the student‐teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–S20.

- , , , et al. Evidence for validity of a survey to measure the learning environment for professionalism. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e683–e688.

- . Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

- , . How can physicians' learning style drive educational planning? Acad Med. 2005;80:680–84.

- , . Twenty years of experience using trigger films as a teaching tool. Acad Med. 2001;76:656–658.

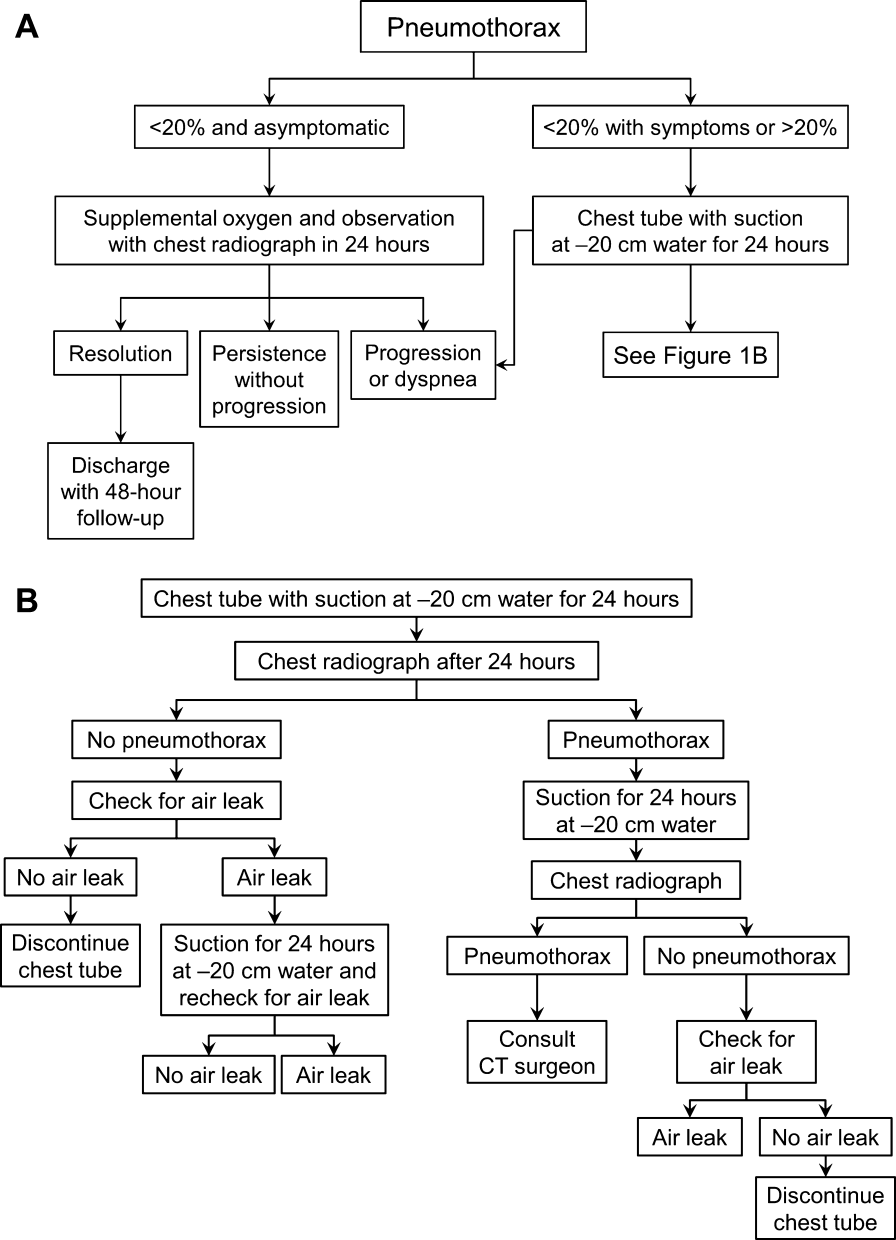

Chest Tube Management

A pneumothorax is a collection of air in the space outside the lungs that is trapped within the thorax. This abnormality can occur spontaneously or as the result of trauma. Traumatic pneumothoraces include those resulting from medical interventions such as a transthoracic and transbronchial needle biopsy, central line placement, and positive‐pressure mechanical ventilation. This group is most accurately described as iatrogenic pneumothorax (IP).[1]

IP can be an expected complication of many routine thoracic procedures, but it can also occur accidentally during procedures near the lung or thoracic cavity. Some IPs may be asymptomatic and go undiagnosed, or their diagnosis may be delayed.[2] The majority of iatrogenic pneumothoraces will resolve without complications, and patients will not require medical attention. A small percentage can, however, expand and have the potential to develop into a tension pneumothorax causing severe respiratory distress and mediastinal shift.[3, 4]