User login

Treating Brain Tumors With Bacteria Gets Neurosurgeons Banned

Are a few animal studies and a handful of human case reports enough to let physicians skirt institutional review boards?

Two neurosurgeons in California did just that when they used Enterobacter aerogenes to infect the surgical wounds of three terminally ill glioblastoma patients. Two of the patients died from the infections.

Dr. J. Paul Muizelaar and Dr. Rudolph J. Schrot of the University of California, Davis, said their attempt to stimulate their patients’ immune response was not research but "a one-time procedure" – exempt from review, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Now both are banned from human research projects and the institutional review board is the subject of its own investigation.

For an account of the scientific thinking behind the deployment of bacteria in these patients and of ongoing efforts to develop immunotherapies against cancer, see the journal Nature (2012 July 27 [doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11080]).

Are a few animal studies and a handful of human case reports enough to let physicians skirt institutional review boards?

Two neurosurgeons in California did just that when they used Enterobacter aerogenes to infect the surgical wounds of three terminally ill glioblastoma patients. Two of the patients died from the infections.

Dr. J. Paul Muizelaar and Dr. Rudolph J. Schrot of the University of California, Davis, said their attempt to stimulate their patients’ immune response was not research but "a one-time procedure" – exempt from review, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Now both are banned from human research projects and the institutional review board is the subject of its own investigation.

For an account of the scientific thinking behind the deployment of bacteria in these patients and of ongoing efforts to develop immunotherapies against cancer, see the journal Nature (2012 July 27 [doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11080]).

Are a few animal studies and a handful of human case reports enough to let physicians skirt institutional review boards?

Two neurosurgeons in California did just that when they used Enterobacter aerogenes to infect the surgical wounds of three terminally ill glioblastoma patients. Two of the patients died from the infections.

Dr. J. Paul Muizelaar and Dr. Rudolph J. Schrot of the University of California, Davis, said their attempt to stimulate their patients’ immune response was not research but "a one-time procedure" – exempt from review, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Now both are banned from human research projects and the institutional review board is the subject of its own investigation.

For an account of the scientific thinking behind the deployment of bacteria in these patients and of ongoing efforts to develop immunotherapies against cancer, see the journal Nature (2012 July 27 [doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11080]).

Rare Brainstem Glioma Doesn't Stop Former Marine

As the men and women who graciously serve our country return home, often times we can easily recognize the associated morbidity that resulted from their service. The physical injuries that can occur are obvious. But people have become more sensitive toward the injuries that are not so easily apparent, such as traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These injuries have been the targets of campaigns to increase awareness not only among practitioners, but also the lay population, particularly as they relate to concussive sports injuries.

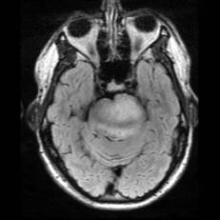

Because these issues are on the forefront of our minds, it’s not hard to understand the misdiagnosis of PTSD in a young marine, Corporal Jordan Mills, who started having difficulty with left ptosis and episodic diplopia in 2008. It wasn’t until he became dysarthric and clumsy on the opposite side that he was transferred out of Afghanistan to a military facility in Germany, where an MRI of the brain revealed a mass raising concern for a brainstem glioma.

Brainstem glioma is a rare brain tumor that occurs mainly in the pediatric population and in young adults. Tissue diagnosis of brainstem glioma often is avoided in an attempt to first do no harm because of the tumor’s diffusely infiltrative nature and the distortion and expansion of the brainstem and its valuable inhabitants. Brainstem glioma is one of the rare instances in oncology when it has been accepted as appropriate to treat based on imaging alone without a tissue diagnosis. Conventional therapy includes radiation with or without the addition of chemotherapy. In spite of aggressive treatment strategies, this fulminating tumor is often fatal within months to years of diagnosis.

Colleagues at the Children’s National Medical Center have developed a protocol to collect serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and tumor tissue of affected patients in an attempt to identify unique molecular abnormalities that would allow practitioners to target therapy more accurately to improve treatment efficacy. Brainstem glioma has been elusive given the lack of tissue to study up to this point, based on only tumor location and biopsy, as opposed to resection options.

In 2010, researchers at the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center reviewed cancer data from 2000-2010 and found that service members have higher rates of melanoma, brain, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and breast, prostate, and testicular cancers than civilians do. The strongest risk factor was associated with age. Interestingly, marines were found to have the lowest rate of cancer overall. Over the time period studied, 904 service members died of cancer, with 101 soldiers succumbing to brain or other nervous system types of cancer.

At the age of 22 years, it was accepted that this was Corp. Mills’s diagnosis and he was honorably discharged from his third and final tour with the marines. He was treated aggressively and went on to receive chemotherapy during his radiation phase and then received an additional 12 months of oral chemotherapy thereafter.

In addition to Jordan’s remarkable physical strength, his mental and emotional strength persevered. His attitude all the while was to continue to live life to the fullest and trust through his faith and his medical team that his tumor would be taken care of.

Jordan went on to marry, start a family, and enroll in the local community college where he graduated with an associate’s degree in accounting with honors. He was accepted into a prestigious school of business and is working to receive his bachelor’s degree in accounting.

Jordan’s tumor progressed in November 2011 and Jordan has reinitiated chemotherapy. His resolve is stronger than ever and he’s working to develop a foundation for marines with brain tumors. The goals of the foundation are to not only provide financial support to the marines and their immediate family, but also to support the education of military personnel on early detection of CNS disorders.

Dr. Porter is a neuro-oncologist in the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

As the men and women who graciously serve our country return home, often times we can easily recognize the associated morbidity that resulted from their service. The physical injuries that can occur are obvious. But people have become more sensitive toward the injuries that are not so easily apparent, such as traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These injuries have been the targets of campaigns to increase awareness not only among practitioners, but also the lay population, particularly as they relate to concussive sports injuries.

Because these issues are on the forefront of our minds, it’s not hard to understand the misdiagnosis of PTSD in a young marine, Corporal Jordan Mills, who started having difficulty with left ptosis and episodic diplopia in 2008. It wasn’t until he became dysarthric and clumsy on the opposite side that he was transferred out of Afghanistan to a military facility in Germany, where an MRI of the brain revealed a mass raising concern for a brainstem glioma.

Brainstem glioma is a rare brain tumor that occurs mainly in the pediatric population and in young adults. Tissue diagnosis of brainstem glioma often is avoided in an attempt to first do no harm because of the tumor’s diffusely infiltrative nature and the distortion and expansion of the brainstem and its valuable inhabitants. Brainstem glioma is one of the rare instances in oncology when it has been accepted as appropriate to treat based on imaging alone without a tissue diagnosis. Conventional therapy includes radiation with or without the addition of chemotherapy. In spite of aggressive treatment strategies, this fulminating tumor is often fatal within months to years of diagnosis.

Colleagues at the Children’s National Medical Center have developed a protocol to collect serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and tumor tissue of affected patients in an attempt to identify unique molecular abnormalities that would allow practitioners to target therapy more accurately to improve treatment efficacy. Brainstem glioma has been elusive given the lack of tissue to study up to this point, based on only tumor location and biopsy, as opposed to resection options.

In 2010, researchers at the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center reviewed cancer data from 2000-2010 and found that service members have higher rates of melanoma, brain, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and breast, prostate, and testicular cancers than civilians do. The strongest risk factor was associated with age. Interestingly, marines were found to have the lowest rate of cancer overall. Over the time period studied, 904 service members died of cancer, with 101 soldiers succumbing to brain or other nervous system types of cancer.

At the age of 22 years, it was accepted that this was Corp. Mills’s diagnosis and he was honorably discharged from his third and final tour with the marines. He was treated aggressively and went on to receive chemotherapy during his radiation phase and then received an additional 12 months of oral chemotherapy thereafter.

In addition to Jordan’s remarkable physical strength, his mental and emotional strength persevered. His attitude all the while was to continue to live life to the fullest and trust through his faith and his medical team that his tumor would be taken care of.

Jordan went on to marry, start a family, and enroll in the local community college where he graduated with an associate’s degree in accounting with honors. He was accepted into a prestigious school of business and is working to receive his bachelor’s degree in accounting.

Jordan’s tumor progressed in November 2011 and Jordan has reinitiated chemotherapy. His resolve is stronger than ever and he’s working to develop a foundation for marines with brain tumors. The goals of the foundation are to not only provide financial support to the marines and their immediate family, but also to support the education of military personnel on early detection of CNS disorders.

Dr. Porter is a neuro-oncologist in the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

As the men and women who graciously serve our country return home, often times we can easily recognize the associated morbidity that resulted from their service. The physical injuries that can occur are obvious. But people have become more sensitive toward the injuries that are not so easily apparent, such as traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These injuries have been the targets of campaigns to increase awareness not only among practitioners, but also the lay population, particularly as they relate to concussive sports injuries.

Because these issues are on the forefront of our minds, it’s not hard to understand the misdiagnosis of PTSD in a young marine, Corporal Jordan Mills, who started having difficulty with left ptosis and episodic diplopia in 2008. It wasn’t until he became dysarthric and clumsy on the opposite side that he was transferred out of Afghanistan to a military facility in Germany, where an MRI of the brain revealed a mass raising concern for a brainstem glioma.

Brainstem glioma is a rare brain tumor that occurs mainly in the pediatric population and in young adults. Tissue diagnosis of brainstem glioma often is avoided in an attempt to first do no harm because of the tumor’s diffusely infiltrative nature and the distortion and expansion of the brainstem and its valuable inhabitants. Brainstem glioma is one of the rare instances in oncology when it has been accepted as appropriate to treat based on imaging alone without a tissue diagnosis. Conventional therapy includes radiation with or without the addition of chemotherapy. In spite of aggressive treatment strategies, this fulminating tumor is often fatal within months to years of diagnosis.

Colleagues at the Children’s National Medical Center have developed a protocol to collect serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and tumor tissue of affected patients in an attempt to identify unique molecular abnormalities that would allow practitioners to target therapy more accurately to improve treatment efficacy. Brainstem glioma has been elusive given the lack of tissue to study up to this point, based on only tumor location and biopsy, as opposed to resection options.

In 2010, researchers at the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center reviewed cancer data from 2000-2010 and found that service members have higher rates of melanoma, brain, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and breast, prostate, and testicular cancers than civilians do. The strongest risk factor was associated with age. Interestingly, marines were found to have the lowest rate of cancer overall. Over the time period studied, 904 service members died of cancer, with 101 soldiers succumbing to brain or other nervous system types of cancer.

At the age of 22 years, it was accepted that this was Corp. Mills’s diagnosis and he was honorably discharged from his third and final tour with the marines. He was treated aggressively and went on to receive chemotherapy during his radiation phase and then received an additional 12 months of oral chemotherapy thereafter.

In addition to Jordan’s remarkable physical strength, his mental and emotional strength persevered. His attitude all the while was to continue to live life to the fullest and trust through his faith and his medical team that his tumor would be taken care of.

Jordan went on to marry, start a family, and enroll in the local community college where he graduated with an associate’s degree in accounting with honors. He was accepted into a prestigious school of business and is working to receive his bachelor’s degree in accounting.

Jordan’s tumor progressed in November 2011 and Jordan has reinitiated chemotherapy. His resolve is stronger than ever and he’s working to develop a foundation for marines with brain tumors. The goals of the foundation are to not only provide financial support to the marines and their immediate family, but also to support the education of military personnel on early detection of CNS disorders.

Dr. Porter is a neuro-oncologist in the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

Skin Flaps Remedy Defects of the Ear

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Michael A. Keefe, 70%-80% of ear defects from auricular cancer treatment can be easily remedied with skin flaps.

The most common locations of auricular cancer are the helix, the posterior auricle skin, and the antihelix, Dr. Keefe said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery.

"More than 70% of lesions are smaller than 3 cm in size, and auricular lesions make up an estimated 8% of all skin cancers," said Dr. Keefe, a plastic surgeon with the division of head and neck surgery at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. "The defects are unique, and the underlying cartilage structure makes it all the more interesting."

And challenging – defects may be located on the skin of the ear only, on the lateral side, or on the posterior side, or they may involve a combination of skin and cartilage. Healing by secondary intention is effective for concave defects, but the size of the defect drives the reconstruction options. "If there is no perichondrium, punch holes through cartilage with a 2-3 mm punch to allow granulation tissue to grow through, and then use a skin graft or allow it to heal with secondary intention," he said. "Keep the area moist with antibiotic ointment."

Options for reconstruction of defects in the middle one-third of the ear include primary closure, full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs), the helical advancement flap, and the retroauricular composite advancement flap, while options for defects in the lower one-third of the ear include primary closure and the preauricular tubed flap. Options for reconstruction of defects in the upper one-third of the ear include primary closure, FTSGs, the helical advancement flap, the retroauricular and preauricular tubed flaps, and constructing an autogenous cartilage framework with FTSGs.

Dr. Keefe said that most small helical rim defects limited to the skin can be closed primarily. "There might be slight rim asymmetry [after closure]," he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic. "Some patients might not care [about this], but you have to advise them of that," he added.

A bilobed advancement flap is another option for helical rim defects limited to the skin. This flap "works well for cutaneous defects 2 cm or smaller in the helical rim or the posterior auricle," he said. "The other thing you can do with these bilobed flaps is advance them over the edge to correct helical rim defects."

The banner flap is another effective flap for helical rim defects, especially those located on the superior helix. It does not replace cartilage, but it conceals the incision well. For small composite helix and anterior defects, Dr. Keefe favors the chondrocutaneous advancement flap.

He said that he favors using FTSGs on the anterior surface of the helix for skin defects whenever possible. "You can use a composite skin graft as well, especially to replace cartilage or skin defects that are smaller than 1 cm in size," he said. "A FTSG is easy to harvest and has minimal contraction. Common donor sites include the preauricular, postauricular, supraclavicular, and clavicular regions. Make sure you trim off the fat." For posterior surface defects, the bilobe or advancement flaps work well.

Grafts must be placed on tissue with an adequate blood supply. Effective grafts establish imbibition in the first 24 hours, inosculation within 48-72 hours, and restoration of circulation within 4-7 days.

Dr. Keefe said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Michael A. Keefe, 70%-80% of ear defects from auricular cancer treatment can be easily remedied with skin flaps.

The most common locations of auricular cancer are the helix, the posterior auricle skin, and the antihelix, Dr. Keefe said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery.

"More than 70% of lesions are smaller than 3 cm in size, and auricular lesions make up an estimated 8% of all skin cancers," said Dr. Keefe, a plastic surgeon with the division of head and neck surgery at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. "The defects are unique, and the underlying cartilage structure makes it all the more interesting."

And challenging – defects may be located on the skin of the ear only, on the lateral side, or on the posterior side, or they may involve a combination of skin and cartilage. Healing by secondary intention is effective for concave defects, but the size of the defect drives the reconstruction options. "If there is no perichondrium, punch holes through cartilage with a 2-3 mm punch to allow granulation tissue to grow through, and then use a skin graft or allow it to heal with secondary intention," he said. "Keep the area moist with antibiotic ointment."

Options for reconstruction of defects in the middle one-third of the ear include primary closure, full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs), the helical advancement flap, and the retroauricular composite advancement flap, while options for defects in the lower one-third of the ear include primary closure and the preauricular tubed flap. Options for reconstruction of defects in the upper one-third of the ear include primary closure, FTSGs, the helical advancement flap, the retroauricular and preauricular tubed flaps, and constructing an autogenous cartilage framework with FTSGs.

Dr. Keefe said that most small helical rim defects limited to the skin can be closed primarily. "There might be slight rim asymmetry [after closure]," he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic. "Some patients might not care [about this], but you have to advise them of that," he added.

A bilobed advancement flap is another option for helical rim defects limited to the skin. This flap "works well for cutaneous defects 2 cm or smaller in the helical rim or the posterior auricle," he said. "The other thing you can do with these bilobed flaps is advance them over the edge to correct helical rim defects."

The banner flap is another effective flap for helical rim defects, especially those located on the superior helix. It does not replace cartilage, but it conceals the incision well. For small composite helix and anterior defects, Dr. Keefe favors the chondrocutaneous advancement flap.

He said that he favors using FTSGs on the anterior surface of the helix for skin defects whenever possible. "You can use a composite skin graft as well, especially to replace cartilage or skin defects that are smaller than 1 cm in size," he said. "A FTSG is easy to harvest and has minimal contraction. Common donor sites include the preauricular, postauricular, supraclavicular, and clavicular regions. Make sure you trim off the fat." For posterior surface defects, the bilobe or advancement flaps work well.

Grafts must be placed on tissue with an adequate blood supply. Effective grafts establish imbibition in the first 24 hours, inosculation within 48-72 hours, and restoration of circulation within 4-7 days.

Dr. Keefe said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Michael A. Keefe, 70%-80% of ear defects from auricular cancer treatment can be easily remedied with skin flaps.

The most common locations of auricular cancer are the helix, the posterior auricle skin, and the antihelix, Dr. Keefe said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery.

"More than 70% of lesions are smaller than 3 cm in size, and auricular lesions make up an estimated 8% of all skin cancers," said Dr. Keefe, a plastic surgeon with the division of head and neck surgery at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego. "The defects are unique, and the underlying cartilage structure makes it all the more interesting."

And challenging – defects may be located on the skin of the ear only, on the lateral side, or on the posterior side, or they may involve a combination of skin and cartilage. Healing by secondary intention is effective for concave defects, but the size of the defect drives the reconstruction options. "If there is no perichondrium, punch holes through cartilage with a 2-3 mm punch to allow granulation tissue to grow through, and then use a skin graft or allow it to heal with secondary intention," he said. "Keep the area moist with antibiotic ointment."

Options for reconstruction of defects in the middle one-third of the ear include primary closure, full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs), the helical advancement flap, and the retroauricular composite advancement flap, while options for defects in the lower one-third of the ear include primary closure and the preauricular tubed flap. Options for reconstruction of defects in the upper one-third of the ear include primary closure, FTSGs, the helical advancement flap, the retroauricular and preauricular tubed flaps, and constructing an autogenous cartilage framework with FTSGs.

Dr. Keefe said that most small helical rim defects limited to the skin can be closed primarily. "There might be slight rim asymmetry [after closure]," he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic. "Some patients might not care [about this], but you have to advise them of that," he added.

A bilobed advancement flap is another option for helical rim defects limited to the skin. This flap "works well for cutaneous defects 2 cm or smaller in the helical rim or the posterior auricle," he said. "The other thing you can do with these bilobed flaps is advance them over the edge to correct helical rim defects."

The banner flap is another effective flap for helical rim defects, especially those located on the superior helix. It does not replace cartilage, but it conceals the incision well. For small composite helix and anterior defects, Dr. Keefe favors the chondrocutaneous advancement flap.

He said that he favors using FTSGs on the anterior surface of the helix for skin defects whenever possible. "You can use a composite skin graft as well, especially to replace cartilage or skin defects that are smaller than 1 cm in size," he said. "A FTSG is easy to harvest and has minimal contraction. Common donor sites include the preauricular, postauricular, supraclavicular, and clavicular regions. Make sure you trim off the fat." For posterior surface defects, the bilobe or advancement flaps work well.

Grafts must be placed on tissue with an adequate blood supply. Effective grafts establish imbibition in the first 24 hours, inosculation within 48-72 hours, and restoration of circulation within 4-7 days.

Dr. Keefe said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON SUPERFICIAL ANATOMY AND CUTANEOUS SURGERY

Early Scar Treatment Is 'Critical'

SAN DIEGO – The future of treating hypertrophic and keloidal scars will involve earlier intervention with new and existing technologies – even at the genesis of scar formation, said Dr. E. Victor Ross.

"I think you’re going to see a lot more in the future about scars, not just in the laser area, but also in the biologic arena, because we’re learning more about the way scars behave," Dr. Ross said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery. "Some physicians are treating scars as early as the time of Mohs surgery, for example, by applying the PDL [pulsed-dye laser] at the time of suture placement. That’s perhaps a bit extreme, but I think you are going to see newer technologies and drugs used synergistically to give us a better fighting chance to prevent and treat scars."

Dr. Ross of Scripps Clinic Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology Center in Carmel Valley, Calif., said that there is a lack of consensus regarding how the two main types of scars hypertrophic and keloidal – are defined. Historically, "we’ve said that hypertrophic scars don’t go beyond the boundary of where the scar tissue was, and keloidal scars go around the perimeter of where the scar boundaries were," he noted. "If the scar is red, even if it’s longstanding, I tend to call it a hypertrophic scar. If it tends to be more flesh colored, and aged like a fine wine, I tend to call it a keloidal scar. The critical thing with these scars is how long it takes the wound to heal. If an open wound takes more than 3-4 weeks to heal, often it will be hypertrophic."

Existing therapies that are commonly used to treat scars include intralesional steroids, intralesional 5-fluorouracil, oral antihistamines, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, lasers, hydrogel sheeting, and compression. "The critical thing is to treat relatively early; you have to use all the weapons that are available to you," Dr. Ross said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic.

He said that when treating scars, a modifiable approach should be taken. "You want to modify the scar. After it’s formed, you want to rehabilitate the scar and make it more like the skin around it."

When using intralesional steroids, Dr. Ross prefers to use very low volumes with a very high concentration of Kenalog, "typically 40 mg/mL in tiny amounts with a 3-gauge, half-inch needle," he said. "You want to keep the needle tip relatively superficial. If the steroid floats into the scar too easily you’re probably too deep or under the scar."

He favors using fractional lasers for scars whenever possible. These devices "create microscopic wounds in the skin," he said. "It turns out that if you fractionate a wound, the reservoirs of normal, undamaged skin act as ‘seeds’ to make the wounds heal quickly. I like to use purpuric settings with the pulsed-dye laser. They tend to give you better results than other settings."

For scars that form after thyroid surgery, Dr. Ross likes to use a PDL or IPL (intense pulsed light) to reduce the redness, followed by a nonablative fractional laser. With that tandem approach "you can almost make the scar go away, which is a complete rehabilitation of the scar," he said.

Innovative scar therapies include topical mitomycin C, which has worked well for postoperative keloids; oral and topical tamoxifen, which helps in the formation of fibroblasts; and oral methotrexate, which has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment and prevention of keloids. Imiquimod has also been used, "but I’m not a believer in it," Dr. Ross said. "We’ve tried it several times and we found that it irritated the skin most of the time. Retinoids are good and bad. They decrease fibroblast activity but also decrease collagenase."

Dr. Ross disclosed that he is a consultant for Cutera, Palomar Medical Technologies, and Lumenis. He has also received research support from Palomar, Sciton, and Syneron Medical.

SAN DIEGO – The future of treating hypertrophic and keloidal scars will involve earlier intervention with new and existing technologies – even at the genesis of scar formation, said Dr. E. Victor Ross.

"I think you’re going to see a lot more in the future about scars, not just in the laser area, but also in the biologic arena, because we’re learning more about the way scars behave," Dr. Ross said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery. "Some physicians are treating scars as early as the time of Mohs surgery, for example, by applying the PDL [pulsed-dye laser] at the time of suture placement. That’s perhaps a bit extreme, but I think you are going to see newer technologies and drugs used synergistically to give us a better fighting chance to prevent and treat scars."

Dr. Ross of Scripps Clinic Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology Center in Carmel Valley, Calif., said that there is a lack of consensus regarding how the two main types of scars hypertrophic and keloidal – are defined. Historically, "we’ve said that hypertrophic scars don’t go beyond the boundary of where the scar tissue was, and keloidal scars go around the perimeter of where the scar boundaries were," he noted. "If the scar is red, even if it’s longstanding, I tend to call it a hypertrophic scar. If it tends to be more flesh colored, and aged like a fine wine, I tend to call it a keloidal scar. The critical thing with these scars is how long it takes the wound to heal. If an open wound takes more than 3-4 weeks to heal, often it will be hypertrophic."

Existing therapies that are commonly used to treat scars include intralesional steroids, intralesional 5-fluorouracil, oral antihistamines, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, lasers, hydrogel sheeting, and compression. "The critical thing is to treat relatively early; you have to use all the weapons that are available to you," Dr. Ross said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic.

He said that when treating scars, a modifiable approach should be taken. "You want to modify the scar. After it’s formed, you want to rehabilitate the scar and make it more like the skin around it."

When using intralesional steroids, Dr. Ross prefers to use very low volumes with a very high concentration of Kenalog, "typically 40 mg/mL in tiny amounts with a 3-gauge, half-inch needle," he said. "You want to keep the needle tip relatively superficial. If the steroid floats into the scar too easily you’re probably too deep or under the scar."

He favors using fractional lasers for scars whenever possible. These devices "create microscopic wounds in the skin," he said. "It turns out that if you fractionate a wound, the reservoirs of normal, undamaged skin act as ‘seeds’ to make the wounds heal quickly. I like to use purpuric settings with the pulsed-dye laser. They tend to give you better results than other settings."

For scars that form after thyroid surgery, Dr. Ross likes to use a PDL or IPL (intense pulsed light) to reduce the redness, followed by a nonablative fractional laser. With that tandem approach "you can almost make the scar go away, which is a complete rehabilitation of the scar," he said.

Innovative scar therapies include topical mitomycin C, which has worked well for postoperative keloids; oral and topical tamoxifen, which helps in the formation of fibroblasts; and oral methotrexate, which has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment and prevention of keloids. Imiquimod has also been used, "but I’m not a believer in it," Dr. Ross said. "We’ve tried it several times and we found that it irritated the skin most of the time. Retinoids are good and bad. They decrease fibroblast activity but also decrease collagenase."

Dr. Ross disclosed that he is a consultant for Cutera, Palomar Medical Technologies, and Lumenis. He has also received research support from Palomar, Sciton, and Syneron Medical.

SAN DIEGO – The future of treating hypertrophic and keloidal scars will involve earlier intervention with new and existing technologies – even at the genesis of scar formation, said Dr. E. Victor Ross.

"I think you’re going to see a lot more in the future about scars, not just in the laser area, but also in the biologic arena, because we’re learning more about the way scars behave," Dr. Ross said at a meeting on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery. "Some physicians are treating scars as early as the time of Mohs surgery, for example, by applying the PDL [pulsed-dye laser] at the time of suture placement. That’s perhaps a bit extreme, but I think you are going to see newer technologies and drugs used synergistically to give us a better fighting chance to prevent and treat scars."

Dr. Ross of Scripps Clinic Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology Center in Carmel Valley, Calif., said that there is a lack of consensus regarding how the two main types of scars hypertrophic and keloidal – are defined. Historically, "we’ve said that hypertrophic scars don’t go beyond the boundary of where the scar tissue was, and keloidal scars go around the perimeter of where the scar boundaries were," he noted. "If the scar is red, even if it’s longstanding, I tend to call it a hypertrophic scar. If it tends to be more flesh colored, and aged like a fine wine, I tend to call it a keloidal scar. The critical thing with these scars is how long it takes the wound to heal. If an open wound takes more than 3-4 weeks to heal, often it will be hypertrophic."

Existing therapies that are commonly used to treat scars include intralesional steroids, intralesional 5-fluorouracil, oral antihistamines, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, lasers, hydrogel sheeting, and compression. "The critical thing is to treat relatively early; you have to use all the weapons that are available to you," Dr. Ross said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and the Scripps Clinic.

He said that when treating scars, a modifiable approach should be taken. "You want to modify the scar. After it’s formed, you want to rehabilitate the scar and make it more like the skin around it."

When using intralesional steroids, Dr. Ross prefers to use very low volumes with a very high concentration of Kenalog, "typically 40 mg/mL in tiny amounts with a 3-gauge, half-inch needle," he said. "You want to keep the needle tip relatively superficial. If the steroid floats into the scar too easily you’re probably too deep or under the scar."

He favors using fractional lasers for scars whenever possible. These devices "create microscopic wounds in the skin," he said. "It turns out that if you fractionate a wound, the reservoirs of normal, undamaged skin act as ‘seeds’ to make the wounds heal quickly. I like to use purpuric settings with the pulsed-dye laser. They tend to give you better results than other settings."

For scars that form after thyroid surgery, Dr. Ross likes to use a PDL or IPL (intense pulsed light) to reduce the redness, followed by a nonablative fractional laser. With that tandem approach "you can almost make the scar go away, which is a complete rehabilitation of the scar," he said.

Innovative scar therapies include topical mitomycin C, which has worked well for postoperative keloids; oral and topical tamoxifen, which helps in the formation of fibroblasts; and oral methotrexate, which has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment and prevention of keloids. Imiquimod has also been used, "but I’m not a believer in it," Dr. Ross said. "We’ve tried it several times and we found that it irritated the skin most of the time. Retinoids are good and bad. They decrease fibroblast activity but also decrease collagenase."

Dr. Ross disclosed that he is a consultant for Cutera, Palomar Medical Technologies, and Lumenis. He has also received research support from Palomar, Sciton, and Syneron Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON SUPERFICIAL ANATOMY AND CUTANEOUS SURGERY

'Weekend Effect' Seen for Diverticulitis Procedures

Patients who were admitted for emergency surgery on a weekend to treat left-sided diverticulitis experience more short-term complications and are markedly more likely to undergo a Hartmann procedure than are those admitted on weekdays, according to results from a large population-based study.

Longer hospital stays, significantly higher treatment costs, and higher rates of reoperations were also associated with weekend admission. However, no differences in mortality were observed between the patient groups.

Previous studies have shown worse outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and intracerebral hemorrhage when they were admitted on weekends. Although the current study, led by Dr. Mathias Worni of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., and Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, was not designed to isolate the cause of the "weekend effect" for left-sided diverticulitis patients, the authors noted that hospital staffing tends to be reduced on weekends – especially among specialists such as colorectal surgeons.

Dr. Worni and his colleagues looked at records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample between January 2002 and December 2008. Of the 31,832 patients who were treated surgically for left-sided diverticulitis, 7,066 (22.2%) were admitted on weekends and 24,766 (77.8%) on weekdays. Patients’ mean age was 60.8 years, and more than half were women.

Among patients who were admitted on a Saturday or Sunday, a Hartmann procedure was performed on 64.8% (n = 4,580), compared with only 53.9% (n = 13,351) for those admitted on a weekday (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:649-55). The Hartmann procedure – which involves formation of a colostomy – has long been the standard surgery for people presenting with left-sided diverticulitis, but is associated with long-term complications and a low rate of reversals.

Primary anastomosis, in which colostomy is avoided, is increasingly preferred, but only 35.2% of patients who were admitted on weekends underwent primary anastomosis, compared with 46.1% of patients admitted on weekdays.

The investigators found that patients admitted on weekends had significantly higher risk for any postoperative complication (odds ratio, 1.10; P = .005), compared with patients admitted on weekdays. Risk of reoperation was also higher among weekend admissions (OR, 1.50; P less than .001).

Furthermore, median total hospital charges were $3,734 higher among patients treated on weekends, and the median length of hospital stay was 0.5 days longer (P less than .001). The authors observed that these findings should motivate improvements in the quality of weekend care.

"Physicians working on weekends are thought to be less experienced than teams working during the week," they wrote. Experienced and specialized colorectal surgeons have been shown to perform more primary anastomoses, compared with trainees or general surgeons (Arch. Surg. 2010;145:79-86; Dis. Colon Rectum 2003;46:1461-8).

Limitations of the study include the fact that it did not capture long-term outcomes or severity of disease at presentation. The latter could be of potential importance: "Some patients, especially those with milder symptoms, may prefer weekend or weekday admission and may time their admission accordingly," the investigators noted.

In an invited critique that accompanied the article, Dr. Juerg Metzger, a surgeon at Lucerne (Switzerland) Cantonal Hospital, wrote that a disparity in experience among weekday and weekend surgical staff likely accounted for the higher rate of Hartmann procedures and complications following weekend admissions.

"Work-hour restrictions do not seem to have a negative influence on mortality and morbidity in surgical patients," Dr. Metzger wrote. "However, reduced experience owing to restricted working hours may negatively influence the practical skills of younger surgeons, resulting in more limited surgery [for example, a Hartmann procedure being performed instead of a primary anastomosis] and an increase in complications related to that surgery."

In the end, Dr. Metzger wrote, "quality is expensive, and our society has to decide if it is desirable and necessary to have the best surgical quality available all the time, especially when considering that health care costs will dramatically increase. It would be relevant to analyze additional large databases, asking similar questions about the outcomes of other common diseases [for example, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and strangulated hernias] and studying the effect of weekend admission on these illnesses."

Dr. Worni’s and colleagues’ was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. None of the investigators declared conflicts of interest. Dr. Metzger declared that he had no conflicts of interest related to his critique.

Patients who were admitted for emergency surgery on a weekend to treat left-sided diverticulitis experience more short-term complications and are markedly more likely to undergo a Hartmann procedure than are those admitted on weekdays, according to results from a large population-based study.

Longer hospital stays, significantly higher treatment costs, and higher rates of reoperations were also associated with weekend admission. However, no differences in mortality were observed between the patient groups.

Previous studies have shown worse outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and intracerebral hemorrhage when they were admitted on weekends. Although the current study, led by Dr. Mathias Worni of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., and Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, was not designed to isolate the cause of the "weekend effect" for left-sided diverticulitis patients, the authors noted that hospital staffing tends to be reduced on weekends – especially among specialists such as colorectal surgeons.

Dr. Worni and his colleagues looked at records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample between January 2002 and December 2008. Of the 31,832 patients who were treated surgically for left-sided diverticulitis, 7,066 (22.2%) were admitted on weekends and 24,766 (77.8%) on weekdays. Patients’ mean age was 60.8 years, and more than half were women.

Among patients who were admitted on a Saturday or Sunday, a Hartmann procedure was performed on 64.8% (n = 4,580), compared with only 53.9% (n = 13,351) for those admitted on a weekday (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:649-55). The Hartmann procedure – which involves formation of a colostomy – has long been the standard surgery for people presenting with left-sided diverticulitis, but is associated with long-term complications and a low rate of reversals.

Primary anastomosis, in which colostomy is avoided, is increasingly preferred, but only 35.2% of patients who were admitted on weekends underwent primary anastomosis, compared with 46.1% of patients admitted on weekdays.

The investigators found that patients admitted on weekends had significantly higher risk for any postoperative complication (odds ratio, 1.10; P = .005), compared with patients admitted on weekdays. Risk of reoperation was also higher among weekend admissions (OR, 1.50; P less than .001).

Furthermore, median total hospital charges were $3,734 higher among patients treated on weekends, and the median length of hospital stay was 0.5 days longer (P less than .001). The authors observed that these findings should motivate improvements in the quality of weekend care.

"Physicians working on weekends are thought to be less experienced than teams working during the week," they wrote. Experienced and specialized colorectal surgeons have been shown to perform more primary anastomoses, compared with trainees or general surgeons (Arch. Surg. 2010;145:79-86; Dis. Colon Rectum 2003;46:1461-8).

Limitations of the study include the fact that it did not capture long-term outcomes or severity of disease at presentation. The latter could be of potential importance: "Some patients, especially those with milder symptoms, may prefer weekend or weekday admission and may time their admission accordingly," the investigators noted.

In an invited critique that accompanied the article, Dr. Juerg Metzger, a surgeon at Lucerne (Switzerland) Cantonal Hospital, wrote that a disparity in experience among weekday and weekend surgical staff likely accounted for the higher rate of Hartmann procedures and complications following weekend admissions.

"Work-hour restrictions do not seem to have a negative influence on mortality and morbidity in surgical patients," Dr. Metzger wrote. "However, reduced experience owing to restricted working hours may negatively influence the practical skills of younger surgeons, resulting in more limited surgery [for example, a Hartmann procedure being performed instead of a primary anastomosis] and an increase in complications related to that surgery."

In the end, Dr. Metzger wrote, "quality is expensive, and our society has to decide if it is desirable and necessary to have the best surgical quality available all the time, especially when considering that health care costs will dramatically increase. It would be relevant to analyze additional large databases, asking similar questions about the outcomes of other common diseases [for example, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and strangulated hernias] and studying the effect of weekend admission on these illnesses."

Dr. Worni’s and colleagues’ was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. None of the investigators declared conflicts of interest. Dr. Metzger declared that he had no conflicts of interest related to his critique.

Patients who were admitted for emergency surgery on a weekend to treat left-sided diverticulitis experience more short-term complications and are markedly more likely to undergo a Hartmann procedure than are those admitted on weekdays, according to results from a large population-based study.

Longer hospital stays, significantly higher treatment costs, and higher rates of reoperations were also associated with weekend admission. However, no differences in mortality were observed between the patient groups.

Previous studies have shown worse outcomes for patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, kidney injury, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and intracerebral hemorrhage when they were admitted on weekends. Although the current study, led by Dr. Mathias Worni of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., and Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, was not designed to isolate the cause of the "weekend effect" for left-sided diverticulitis patients, the authors noted that hospital staffing tends to be reduced on weekends – especially among specialists such as colorectal surgeons.

Dr. Worni and his colleagues looked at records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample between January 2002 and December 2008. Of the 31,832 patients who were treated surgically for left-sided diverticulitis, 7,066 (22.2%) were admitted on weekends and 24,766 (77.8%) on weekdays. Patients’ mean age was 60.8 years, and more than half were women.

Among patients who were admitted on a Saturday or Sunday, a Hartmann procedure was performed on 64.8% (n = 4,580), compared with only 53.9% (n = 13,351) for those admitted on a weekday (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:649-55). The Hartmann procedure – which involves formation of a colostomy – has long been the standard surgery for people presenting with left-sided diverticulitis, but is associated with long-term complications and a low rate of reversals.

Primary anastomosis, in which colostomy is avoided, is increasingly preferred, but only 35.2% of patients who were admitted on weekends underwent primary anastomosis, compared with 46.1% of patients admitted on weekdays.

The investigators found that patients admitted on weekends had significantly higher risk for any postoperative complication (odds ratio, 1.10; P = .005), compared with patients admitted on weekdays. Risk of reoperation was also higher among weekend admissions (OR, 1.50; P less than .001).

Furthermore, median total hospital charges were $3,734 higher among patients treated on weekends, and the median length of hospital stay was 0.5 days longer (P less than .001). The authors observed that these findings should motivate improvements in the quality of weekend care.

"Physicians working on weekends are thought to be less experienced than teams working during the week," they wrote. Experienced and specialized colorectal surgeons have been shown to perform more primary anastomoses, compared with trainees or general surgeons (Arch. Surg. 2010;145:79-86; Dis. Colon Rectum 2003;46:1461-8).

Limitations of the study include the fact that it did not capture long-term outcomes or severity of disease at presentation. The latter could be of potential importance: "Some patients, especially those with milder symptoms, may prefer weekend or weekday admission and may time their admission accordingly," the investigators noted.

In an invited critique that accompanied the article, Dr. Juerg Metzger, a surgeon at Lucerne (Switzerland) Cantonal Hospital, wrote that a disparity in experience among weekday and weekend surgical staff likely accounted for the higher rate of Hartmann procedures and complications following weekend admissions.

"Work-hour restrictions do not seem to have a negative influence on mortality and morbidity in surgical patients," Dr. Metzger wrote. "However, reduced experience owing to restricted working hours may negatively influence the practical skills of younger surgeons, resulting in more limited surgery [for example, a Hartmann procedure being performed instead of a primary anastomosis] and an increase in complications related to that surgery."

In the end, Dr. Metzger wrote, "quality is expensive, and our society has to decide if it is desirable and necessary to have the best surgical quality available all the time, especially when considering that health care costs will dramatically increase. It would be relevant to analyze additional large databases, asking similar questions about the outcomes of other common diseases [for example, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and strangulated hernias] and studying the effect of weekend admission on these illnesses."

Dr. Worni’s and colleagues’ was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. None of the investigators declared conflicts of interest. Dr. Metzger declared that he had no conflicts of interest related to his critique.

FROM ARCHIVES OF SURGERY

Major Finding: Weekend admission to the hospital for diverticulitis posed a significantly higher risk for any postoperative complication (OR, 1.10; P = .005) and risk of reoperation (OR, 1.50; P less than .001), compared with weekday admission.

Data Source: The findings are based on an analysis of NIS records for 31,832 patients who were treated surgically for left-sided diverticulitis.

Disclosures: Dr. Worni’s and colleagues’ study was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. None of the investigators declared conflicts of interest. Dr. Metzger declared that he had no conflicts of interest related to his critique.

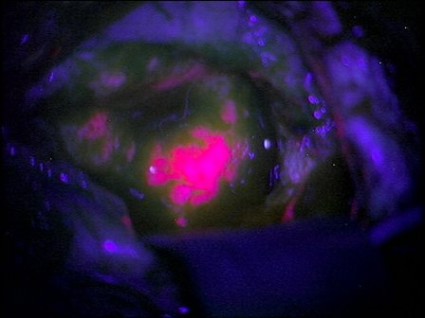

Brain Tumors Glow 'Like Lava' With New Surgical Probe

Neurosurgeons can now follow a glowing road map that points the way to cancerous brain tissue, leading thereby to a more effective surgical excision.

Researchers at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., have developed a probe that uses protoporphyrin IX fluorescence, oxygen saturation, hemoglobin concentration, and cell morphology to differentiate cancerous tissue from normal.

The probe identified 94% of glioma tissue in a small pilot study (J. Biomed. Opt. 2012 May 4 [doi:10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056008]).

Research in Germany 15 years ago suggested that such a tool would identify only highly metabolic primary tumors. But augmenting the fluorescence technique with a computer algorithm that added the other cellular features gave surgeons a "jaw-dropping" view of low-grade tumors.

"The tumor glowed like lava," said Keith Paulsen, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the school of engineering and a member of the cancer imaging and radiobiology research program at Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

The team will next evaluate their technique on lung cancers, with investigations of other tumor types to follow.

Neurosurgeons can now follow a glowing road map that points the way to cancerous brain tissue, leading thereby to a more effective surgical excision.

Researchers at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., have developed a probe that uses protoporphyrin IX fluorescence, oxygen saturation, hemoglobin concentration, and cell morphology to differentiate cancerous tissue from normal.

The probe identified 94% of glioma tissue in a small pilot study (J. Biomed. Opt. 2012 May 4 [doi:10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056008]).

Research in Germany 15 years ago suggested that such a tool would identify only highly metabolic primary tumors. But augmenting the fluorescence technique with a computer algorithm that added the other cellular features gave surgeons a "jaw-dropping" view of low-grade tumors.

"The tumor glowed like lava," said Keith Paulsen, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the school of engineering and a member of the cancer imaging and radiobiology research program at Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

The team will next evaluate their technique on lung cancers, with investigations of other tumor types to follow.

Neurosurgeons can now follow a glowing road map that points the way to cancerous brain tissue, leading thereby to a more effective surgical excision.

Researchers at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., have developed a probe that uses protoporphyrin IX fluorescence, oxygen saturation, hemoglobin concentration, and cell morphology to differentiate cancerous tissue from normal.

The probe identified 94% of glioma tissue in a small pilot study (J. Biomed. Opt. 2012 May 4 [doi:10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056008]).

Research in Germany 15 years ago suggested that such a tool would identify only highly metabolic primary tumors. But augmenting the fluorescence technique with a computer algorithm that added the other cellular features gave surgeons a "jaw-dropping" view of low-grade tumors.

"The tumor glowed like lava," said Keith Paulsen, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the school of engineering and a member of the cancer imaging and radiobiology research program at Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

The team will next evaluate their technique on lung cancers, with investigations of other tumor types to follow.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL OPTICS

Discordant Antibiotics in Pediatric UTI

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalizations.1 Bacterial infections require prompt treatment with appropriate antimicrobial agents. Results from culture and susceptibility testing, however, are often unavailable until 48 hours after initial presentation. Therefore, the clinician must select antimicrobials empirically, basing decisions on likely pathogens and local resistance patterns.2 This decision is challenging because the effect of treatment delay on clinical outcomes is difficult to determine and resistance among uropathogens is increasing. Resistance rates have doubled over the past several years.3, 4 For common first‐line antibiotics, such as ampicillin and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, resistance rates for Escherichia coli, the most common uropathogen, exceed 25%.4, 5 While resistance to third‐generation cephalosporins remains low, rates in the United States have increased from <1% in 1999 to 4% in 2010. International data shows much higher resistance rates for cephalosporins in general.6, 7 This high prevalence of resistance may prompt the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics for patients with UTI. For example, the use of third‐generation cephalosporins for UTI has doubled in recent years.3 Untreated, UTIs can lead to serious illness, but the consequences of inadequate initial antibiotic coverage are unknown.8, 9

Discordant antibiotic therapy, initial antibiotic therapy to which the causative bacterium is not susceptible, occurs in up to 9% of children hospitalized for UTI.10 However, there is reason to believe that discordant therapy may matter less for UTIs than for infections at other sites. First, in adults hospitalized with UTIs, discordant initial therapy did not affect the time to resolution of symptoms.11, 12 Second, most antibiotics used to treat UTIs are renally excreted and, thus, antibiotic concentrations at the site of infection are higher than can be achieved in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid.13 The Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute has acknowledged that traditional susceptibility breakpoints may be too conservative for some non‐central nervous system infections; such as non‐central nervous system infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.14

As resistance rates increase, more patients are likely to be treated with discordant therapy. Therefore, we sought to identify the clinical consequences of discordant antimicrobial therapy for patients hospitalized with a UTI.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Data for this study were originally collected for a study that determined the accuracy of individual and combined International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) discharge diagnosis codes for children with laboratory tests for a UTI, in order to develop national quality measures for children hospitalized with UTIs.15 The institutional review board for each hospital (Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; Monroe Carell Jr Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH; Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA) approved the study.

Data Sources

Data were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and medical records for patients at the 5 participating hospitals. PHIS contains clinical and billing data from hospitalized children at 43 freestanding children's hospitals. Data quality and coding reliability are assured through a joint effort between the Children's Hospital Association (Shawnee Mission, KS) and participating hospitals.16 PHIS was used to identify participants based on presence of discharge diagnosis code and laboratory tests indicating possible UTI, patient demographics, antibiotic administration date, and utilization of hospital resources (length of stay [LOS], laboratory testing).

Medical records for each participant were reviewed to obtain laboratory and clinical information such as past medical history (including vesicoureteral reflux [VUR], abnormal genitourinary [GU] anatomy, use of prophylactic antibiotic), culture data, and fever data. Data were entered into a secured centrally housed web‐based data collection system. To assure consistency of chart review, all investigators responsible for data collection underwent training. In addition, 2 pilot medical record reviews were performed, followed by group discussion, to reach consensus on questions, preselected answers, interpretation of medical record data, and parameters for free text data entry.

Subjects

The initial cohort included 460 hospitalized patients, aged 3 days to 18 years of age, discharged from participating hospitals between July 1, 2008 and June 30, 2009 with a positive urine culture at any time during hospitalization.15 We excluded patients under 3 days of age because patients this young are more likely to have been transferred from the birthing hospital for a complication related to birth or a congenital anomaly. For this secondary analysis of patients from a prior study, our target population included patients admitted for management of UTI.15 We excluded patients with a negative initial urine culture (n = 59) or if their initial urine culture did not meet definition of laboratory‐confirmed UTI, defined as urine culture with >50,000 colony‐forming units (CFU) with an abnormal urinalysis (UA) (n = 77).1, 1719 An abnormal UA was defined by presence of white blood cells, leukocyte esterase, bacteria, and/or nitrites. For our cohort, all cultures with >50,000 CFU also had an abnormal urinalysis. We excluded 19 patients with cultures classified as 10,000100,000 CFU because we could not confirm that the CFU was >50,000. We excluded 30 patients with urine cultures classified as normal or mixed flora, positive for a mixture of organisms not further identified, or if results were unavailable. Additionally, coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus species (n = 8) were excluded, as these are typically considered contaminants in the setting of urine cultures.2 Patients likely to have received antibiotics prior to admission, or develop a UTI after admission, were identified and removed from the cohort if they had a urine culture performed more than 1 day before, or 2 days after, admission (n = 35). Cultures without resistance testing to the initial antibiotic selection were also excluded (n = 16).

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was hospital LOS. Time to fever resolution was a secondary outcome measure. Fever was defined as temperature 38C. Fever duration was defined as number of hours until resolution of fever; only patients with fever at admission were included in this subanalysis.

Main Exposure

The main exposure was initial antibiotic therapy. Patients were classified into 3 groups according to initial antibiotic selection: those receiving 1) concordant; 2) discordant; or 3) delayed initial therapy. Concordance was defined as in vitro susceptibility to the initial antibiotic or class of antibiotic. If the uropathogen was sensitive to a narrow‐spectrum antibiotic (eg, first‐generation cephalosporin), but was not tested against a more broad‐spectrum antibiotic of the same class (eg, third‐generation cephalosporin), concordance was based on the sensitivity to the narrow‐spectrum antibiotic. If the uropathogen was sensitive to a broad‐spectrum antibiotic (eg, third‐generation cephalosporin), concordance to a more narrow‐spectrum antibiotic was not assumed. Discordance was defined as laboratory confirmation of in vitro resistance, or intermediate sensitivity of the pathogen to the initial antibiotic or class of antibiotics. Patients were considered to have a delay in antibiotic therapy if they did not receive antibiotics on the day of, or day after, collection of UA and culture. Patients with more than 1 uropathogen identified in a single culture were classified as discordant if any of the organisms was discordant to the initial antibiotic; they were classified as concordant if all organisms were concordant to the initial antibiotic. Antibiotic susceptibility was not tested in some cases (n = 16).

Initial antibiotic was defined as the antibiotic(s) billed on the same day or day after the UA was billed. If the patient had the UA completed on the day prior to admission, we used the antibiotic administered on the day of admission as the initial antibiotic.

Covariates

Covariates were selected a priori to include patient characteristics likely to affect patient outcomes; all were included in the final analysis. These were age, race, sex, insurance, disposition, prophylactic antibiotic use for any reason (VUR, oncologic process, etc), presence of a chronic care condition, and presence of VUR or GU anatomic abnormality. Age, race, sex, and insurance were obtained from PHIS. Medical record review was used to determine prophylactic antibiotic use, and presence of VUR or GU abnormalities (eg, posterior urethral valves). Chronic care conditions were defined using a previously reported method.20

Data Analysis

Continuous variables were described using median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described using frequencies. Multivariable analyses were used to determine the independent association of discordant antibiotic therapy and the outcomes of interest. Poisson regression was used to fit the skewed LOS distribution. The effect of antibiotic concordance or discordance on LOS was determined for all patients in our sample, as well as for those with a urine culture positive for a single identified organism. We used the KruskalWallis test statistic to determine the association between duration of fever and discordant antibiotic therapy, given that duration of fever is a continuous variable. Generalized estimating equations accounted for clustering by hospital and the variability that exists between hospitals.

RESULTS

Of the initial 460 cases with positive urine culture growth at any time during admission, 216 met inclusion criteria for a laboratory‐confirmed UTI from urine culture completed at admission. The median age was 2.46 years (IQR: 0.27,8.89). In the study population, 25.0% were male, 31.0% were receiving prophylactic antibiotics, 13.0% had any grade of VUR, and 16.7% had abnormal GU anatomy (Table 1). A total of 82.4% of patients were treated with concordant initial therapy, 10.2% with discordant initial therapy, and 7.4% received delayed initial antibiotic therapy. There were no significant differences between the groups for any of the covariates. Discordant antibiotic cases ranged from 4.9% to 21.7% across hospitals.

| Overall | Concordant* | Discordant | Delayed Antibiotics | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| N | 216 | 178 (82.4) | 22 (10.2) | 16 (7.4) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 54 (25.0) | 40 (22.5) | 8 (36.4) | 6 (37.5) | 0.18 |

| Female | 162 (75.0) | 138 (77.5) | 14 (63.64) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Race | |||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 136 (63.9) | 110 (62.5) | 15 (71.4) | 11 (68.8) | 0.83 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 28 (13.2) | 24 (13.6) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Hispanic | 20 (9.4) | 16 (9.1) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Asian | 10 (4.7) | 9 (5.1) | 1 (4.7) | ||

| Other | 19 (8.9) | 17 (9.7) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Payor | |||||

| Government | 97 (44.9) | 80 (44.9) | 11 (50.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.58 |

| Private | 70 (32.4) | 56 (31.5) | 6 (27.3) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Other | 49 (22.7) | 42 (23.6) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Disposition | |||||

| Home | 204 (94.4) | 168 (94.4) | 21 (95.5) | 15 (93.8) | 0.99 |

| Died | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Other | 11 (5.1) | 9 (5.1) | 1 (4.6) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Age | |||||

| 3 d60 d | 40 (18.5) | 35 (19.7) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (12.5) | 0.53 |

| 61 d2 y | 62 (28.7) | 54 (30.3) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (25.0) | |

| 3 y12 y | 75 (34.7) | 61 (34.3) | 8 (36.4) | 6 (37.5) | |

| 13 y18 y | 39 (18.1) | 28 (15.7) | 7 (31.8) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Length of stay | |||||

| 1 d5 d | 171 (79.2) | 147 (82.6) | 12 (54.6) | 12 (75.0) | 0.03 |

| 6 d10 d | 24 (11.1) | 17 (9.6) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| 11 d15 d | 10 (4.6) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| 16 d+ | 11 (5.1) | 9 (5.1) | 2 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Complex chronic conditions | |||||

| Any CCC | 94 (43.5) | 77 (43.3) | 12 (54.6) | 5 (31.3) | 0.35 |

| Cardiovascular | 20 (9.3) | 19 (10.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0.24 | |

| Neuromuscular | 34 (15.7) | 26 (14.6) | 7 (31.8) | 1 (6.3) | 0.06 |

| Respiratory | 6 (2.8) | 6 (3.4) | 0.52 | ||

| Renal | 26 (12.0) | 21 (11.8) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (6.3) | 0.52 |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.7) | 0.72 | ||

| Hematologic/ immunologic | 1 (0.5) | 1 (4.6) | 0.01 | ||

| Metabolic | 8 (3.7) | 6 (3.4) | 1 (4.6) | 1 (6.3) | 0.82 |

| Congenital or genetic | 15 (6.9) | 11 (6.2) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (6.3) | 0.43 |

| Malignancy | 5 (2.3) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (9.1) | 0.08 | |

| VUR | 28 (13.0) | 23 (12.9) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (12.5) | 0.99 |

| Abnormal GU | 36 (16.7) | 31 (17.4) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (6.3) | 0.51 |

| Prophylactic antibiotics | 67 (31.0) | 53 (29.8) | 10 (45.5) | 4 (25.0) | 0.28 |

The most common causative organisms were E. coli (65.7%) and Klebsiella spp (9.7%) (Table 2). The most common initial antibiotics were a third‐generation cephalosporin (39.1%), combination of ampicillin and a third‐ or fourth‐generation cephalosporin (16.7%), and combination of ampicillin with gentamicin (11.1%). A third‐generation cephalosporin was the initial antibiotic for 46.1% of the E. coli and 56.9% of Klebsiella spp UTIs. Resistance to third‐generation cephalosporins but carbapenem susceptibility was noted for 4.5% of E. coli and 7.7% of Klebsiella spp isolates. Patients with UTIs caused by Klebsiella spp, mixed organisms, and Enterobacter spp were more likely to receive discordant antibiotic therapy. Patients with Enterobacter spp and mixed‐organism UTIs were more likely to have delayed antibiotic therapy. Nineteen patients (8.8%) had positive blood cultures. Fifteen (6.9%) required intensive care unit (ICU) admission during hospitalization.

| Organism | Cases | Concordant* No. (%) | Discordant No. (%) | Delayed Antibiotics No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| E. coli | 142 | 129 (90.8) | 3 (2.1) | 10 (7.0) |

| Klebsiella spp | 21 | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| Enterococcus spp | 12 | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| Enterobacter spp | 10 | 5 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Pseudomonas spp | 10 | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

| Other single organisms | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Other identified multiple organisms | 15 | 7 (46.7) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) |

Unadjusted results are shown in Supporting Appendix 1, in the online version of this article. In the adjusted analysis, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly longer LOS, compared with concordant therapy for all UTIs and for all UTIs caused by a single organism (Table 3). In adjusted analysis, discordant therapy was also associated with a 3.1 day (IQR: 2.0, 4.7) longer length of stay compared with concordant therapy for all E. coli UTIs.

| Bacteria | Difference in LOS (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| All organisms | ||

| Concordant vs discordant | 1.8 (2.1, 1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Concordant vs delayed antibiotics | 1.4 (1.7, 1.1) | 0.01 |

| Single organisms | ||

| Concordant vs discordant | 1.9 (2.4, 1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Concordant vs delayed antibiotics | 1.2 (1.6, 1.2) | 0.37 |

Time to fever resolution was analyzed for patients with a documented fever at presentation for each treatment subgroup. One hundred thirty‐six patients were febrile at admission and 122 were febrile beyond the first recorded vital signs. Fever was present at admission in 60% of the concordant group and 55% of the discordant group (P = 0.6). The median duration of fever was 48 hours for the concordant group (n = 107; IQR: 24, 240) and 78 hours for the discordant group (n = 12; IQR: 48, 132). All patients were afebrile at discharge. Differences in fever duration between treatment groups were not statistically significant (P = 0.7).

DISCUSSION

Across 5 children's hospitals, 1 out of every 10 children hospitalized for UTI received discordant initial antibiotic therapy. Children receiving discordant antibiotic therapy had a 1.8 day longer LOS when compared with those on concordant therapy. However, there was no significant difference in time to fever resolution between the groups, suggesting that the increase in LOS was not explained by increased fever duration.

The overall rate of discordant therapy in this study is consistent with prior studies, as was the more common association of discordant therapy with non‐E. coli UTIs.10 According to the Kids' Inpatient Database 2009, there are 48,100 annual admissions for patients less than 20 years of age with a discharge diagnosis code of UTI in the United States.1 This suggests that nearly 4800 children with UTI could be affected by discordant therapy annually.

Children treated with discordant antibiotic therapy had a significantly longer LOS compared to those treated with concordant therapy. However, differences in time to fever resolution between the groups were not statistically significant. While resolution of fever may suggest clinical improvement and adequate empiric therapy, the lack of association with antibiotic concordance was not unexpected, since the relationship between fever resolution, clinical improvement, and LOS is complex and thus challenging to measure.21 These results support the notion that fever resolution alone may not be an adequate measure of clinical response.

It is possible that variability in discharge decision‐making may contribute to increased length of stay. Some clinicians may delay a patient's discharge until complete resolution of symptoms or knowledge of susceptibilities, while others may discharge patients that are still febrile and/or still receiving empiric antibiotics. Evidence‐based guidelines that address the appropriate time to discharge a patient with UTI are lacking. The American Academy of Pediatrics provides recommendations for use of parenteral antibiotics and hospital admission for patients with UTI, but does not address discharge decision‐making or patient management in the setting of discordant antibiotic therapy.2, 21

This study must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, our primary and secondary outcomes, LOS and fever duration, were surrogate measures for clinical response. We were not able to measure all clinical factors that may contribute to LOS, such as the patient's ability to tolerate oral fluids and antibiotics. Also, there may have been too few patients to detect a clinically important difference in fever duration between the concordant and discordant groups, especially for individual organisms. Although we did find a significant difference in LOS between patients treated with concordant compared with discordant therapy, there may be residual confounding from unobserved differences. This confounding, in conjunction with the small sample size, may cause us to underestimate the magnitude of the difference in LOS resulting from discordant therapy. Second, short‐term outcomes such as ICU admission were not investigated in this study; however, the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU in our population was quite small, precluding its use as a meaningful outcome measure. Third, the potential benefits to patients who were not exposed to unnecessary antibiotics, or harm to those that were exposed, could not be measured. Finally, our study was obtained using data from 5 free‐standing tertiary care pediatric facilities, thereby limiting its generalizability to other settings. Still, our rates of prophylactic antibiotic use, VUR, and GU abnormalities are similar to others reported in tertiary care children's hospitals, and we accounted for these covariates in our model.2225

As the frequency of infections caused by resistant bacteria increase, so will the number of patients receiving discordant antibiotics for UTI, compounding the challenge of empiric antimicrobial selection. Further research is needed to better understand how discordant initial antibiotic therapy contributes to LOS and whether it is associated with adverse short‐ and long‐term clinical outcomes. Such research could also aid in weighing the risk of broader‐spectrum prescribing on antimicrobial resistance patterns. While we identified an association between discordant initial antibiotic therapy and LOS, we were unable to determine the ideal empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with UTI. Further investigation is needed to inform local and national practice guidelines for empiric antibiotic selection in patients with UTIs. This may also be an opportunity to decrease discordant empiric antibiotic selection, perhaps through use of antibiograms that stratify patients based on known factors, to lead to more specific initial therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that discordant antibiotic selection for UTI at admission is associated with longer hospital stay, but not fever duration. The full clinical consequences of discordant therapy, and the effects on length of stay, need to be better understood. Our findings, taken in combination with careful consideration of patient characteristics and prior history, may provide an opportunity to improve the hospital care for patients with UTIs.

Acknowledgements