User login

Commentary: Advances in HER2 advanced breast cancer, July 2023

The neoadjuvant setting provides a favorable environment to study de-escalation approaches as treatment response (via pathologic complete response [pCR] assessment) can be used as a surrogate marker for outcome. Studies have shown the effect of HER2-enriched subtype and high ERBB2 expression on pCR rates after receipt of a chemotherapy-free, dual HER2-targeted regimen.2 The prospective, multicenter, neoadjuvant phase 2 WSG-TP-II trial randomly assigned 207 patients with HR+/HER2+ early breast cancer to 12 weeks of endocrine therapy (ET)–trastuzumab-pertuzumab vs paclitaxel-trastuzumab-pertuzumab. The pCR rate was inferior in the ET arm compared with the paclitaxel arm (23.7% vs 56.4%; odds ratio 0.24; 95% CI 0.12-0.46; P < .001). In addition, an immunohistochemistry ERBB2 score of 3 or higher and ERBB2-enriched subtype were predictors of higher pCR rates in both arms (Gluz et al). This study not only supports a deescalated chemotherapy neoadjuvant strategy of paclitaxel + dual HER2 blockade but also suggests that a portion of patients may potentially be spared chemotherapy with very good results. The role of biomarkers is integral to patient selection for these approaches, and the evaluation of response in real-time will allow for the tailoring of therapy to achieve the best outcome.

Systemic staging for locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is important for informing prognosis as well as aiding in development of an appropriate treatment plan for patients. The PETABC study included 369 patients with LABC (TNM stage III or IIB [T3N0]) with random assignment to 18F-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT or conventional staging (bone scan, CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis), and was designed to assess the rate of upstaging with each imaging modality and effect on treatment (Dayes et al). In the PET-CT group, 23% (N = 43) of patients were upstaged to stage IV compared with 11% (N = 21) in the conventional-staging group (absolute difference 12.3%; 95% CI 3.9-19.9; P = .002). Fewer patients in the PET-CT group received combined modality treatment vs those patients in the conventional staging group (81% vs 89.2%; P = .03). These results support the consideration of PET-CT as a staging tool for LABC, and this is reflected in various clinical guidelines. Furthermore, the evolving role of other imaging techniques such as 18F-fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) PET-CT in detection of metastatic lesions related to estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer3 will continue to advance the field of imaging.

Additional References

- Rugo HS, Lerebours F, Ciruelos E, et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): One cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:489-498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00034-6. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):e184. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00194-7

- Prat A, Pascual T, De Angelis C, et al. HER2-enriched subtype and ERBB2 expression in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with dual HER2 blockade. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:46-54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz042

- Ulaner GA, Jhaveri K, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Head-to-head evaluation of 18F-FES and 18F-FDG PET/CT in metastatic invasive lobular breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:326-331. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.247882

The neoadjuvant setting provides a favorable environment to study de-escalation approaches as treatment response (via pathologic complete response [pCR] assessment) can be used as a surrogate marker for outcome. Studies have shown the effect of HER2-enriched subtype and high ERBB2 expression on pCR rates after receipt of a chemotherapy-free, dual HER2-targeted regimen.2 The prospective, multicenter, neoadjuvant phase 2 WSG-TP-II trial randomly assigned 207 patients with HR+/HER2+ early breast cancer to 12 weeks of endocrine therapy (ET)–trastuzumab-pertuzumab vs paclitaxel-trastuzumab-pertuzumab. The pCR rate was inferior in the ET arm compared with the paclitaxel arm (23.7% vs 56.4%; odds ratio 0.24; 95% CI 0.12-0.46; P < .001). In addition, an immunohistochemistry ERBB2 score of 3 or higher and ERBB2-enriched subtype were predictors of higher pCR rates in both arms (Gluz et al). This study not only supports a deescalated chemotherapy neoadjuvant strategy of paclitaxel + dual HER2 blockade but also suggests that a portion of patients may potentially be spared chemotherapy with very good results. The role of biomarkers is integral to patient selection for these approaches, and the evaluation of response in real-time will allow for the tailoring of therapy to achieve the best outcome.

Systemic staging for locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is important for informing prognosis as well as aiding in development of an appropriate treatment plan for patients. The PETABC study included 369 patients with LABC (TNM stage III or IIB [T3N0]) with random assignment to 18F-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT or conventional staging (bone scan, CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis), and was designed to assess the rate of upstaging with each imaging modality and effect on treatment (Dayes et al). In the PET-CT group, 23% (N = 43) of patients were upstaged to stage IV compared with 11% (N = 21) in the conventional-staging group (absolute difference 12.3%; 95% CI 3.9-19.9; P = .002). Fewer patients in the PET-CT group received combined modality treatment vs those patients in the conventional staging group (81% vs 89.2%; P = .03). These results support the consideration of PET-CT as a staging tool for LABC, and this is reflected in various clinical guidelines. Furthermore, the evolving role of other imaging techniques such as 18F-fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) PET-CT in detection of metastatic lesions related to estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer3 will continue to advance the field of imaging.

Additional References

- Rugo HS, Lerebours F, Ciruelos E, et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): One cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:489-498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00034-6. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):e184. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00194-7

- Prat A, Pascual T, De Angelis C, et al. HER2-enriched subtype and ERBB2 expression in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with dual HER2 blockade. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:46-54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz042

- Ulaner GA, Jhaveri K, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Head-to-head evaluation of 18F-FES and 18F-FDG PET/CT in metastatic invasive lobular breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:326-331. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.247882

The neoadjuvant setting provides a favorable environment to study de-escalation approaches as treatment response (via pathologic complete response [pCR] assessment) can be used as a surrogate marker for outcome. Studies have shown the effect of HER2-enriched subtype and high ERBB2 expression on pCR rates after receipt of a chemotherapy-free, dual HER2-targeted regimen.2 The prospective, multicenter, neoadjuvant phase 2 WSG-TP-II trial randomly assigned 207 patients with HR+/HER2+ early breast cancer to 12 weeks of endocrine therapy (ET)–trastuzumab-pertuzumab vs paclitaxel-trastuzumab-pertuzumab. The pCR rate was inferior in the ET arm compared with the paclitaxel arm (23.7% vs 56.4%; odds ratio 0.24; 95% CI 0.12-0.46; P < .001). In addition, an immunohistochemistry ERBB2 score of 3 or higher and ERBB2-enriched subtype were predictors of higher pCR rates in both arms (Gluz et al). This study not only supports a deescalated chemotherapy neoadjuvant strategy of paclitaxel + dual HER2 blockade but also suggests that a portion of patients may potentially be spared chemotherapy with very good results. The role of biomarkers is integral to patient selection for these approaches, and the evaluation of response in real-time will allow for the tailoring of therapy to achieve the best outcome.

Systemic staging for locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is important for informing prognosis as well as aiding in development of an appropriate treatment plan for patients. The PETABC study included 369 patients with LABC (TNM stage III or IIB [T3N0]) with random assignment to 18F-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT or conventional staging (bone scan, CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis), and was designed to assess the rate of upstaging with each imaging modality and effect on treatment (Dayes et al). In the PET-CT group, 23% (N = 43) of patients were upstaged to stage IV compared with 11% (N = 21) in the conventional-staging group (absolute difference 12.3%; 95% CI 3.9-19.9; P = .002). Fewer patients in the PET-CT group received combined modality treatment vs those patients in the conventional staging group (81% vs 89.2%; P = .03). These results support the consideration of PET-CT as a staging tool for LABC, and this is reflected in various clinical guidelines. Furthermore, the evolving role of other imaging techniques such as 18F-fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) PET-CT in detection of metastatic lesions related to estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer3 will continue to advance the field of imaging.

Additional References

- Rugo HS, Lerebours F, Ciruelos E, et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): One cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:489-498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00034-6. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):e184. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00194-7

- Prat A, Pascual T, De Angelis C, et al. HER2-enriched subtype and ERBB2 expression in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with dual HER2 blockade. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:46-54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz042

- Ulaner GA, Jhaveri K, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Head-to-head evaluation of 18F-FES and 18F-FDG PET/CT in metastatic invasive lobular breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:326-331. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.247882

The most important question in medicine

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Today I am going to tell you the single best question you can ask any doctor, the one that has saved my butt countless times throughout my career, the one that every attending physician should be asking every intern and resident when they present a new case. That question: “What else could this be?”

I know, I know – “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” I get it. But sometimes we get so good at our jobs, so good at recognizing horses, that we stop asking ourselves about zebras at all. You see this in a phenomenon known as “anchoring bias” where physicians, when presented with a diagnosis, tend to latch on to that diagnosis based on the first piece of information given, paying attention to data that support it and ignoring data that point in other directions.

That special question: “What else could this be?”, breaks through that barrier. It forces you, the medical team, everyone, to go through the exercise of real, old-fashioned differential diagnosis. And I promise that if you do this enough, at some point it will save someone’s life.

Though the concept of anchoring bias in medicine is broadly understood, it hasn’t been broadly studied until now, with this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Here’s the setup.

The authors hypothesized that there would be substantial anchoring bias when patients with heart failure presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath if the triage “visit reason” section mentioned HF. We’re talking about the subtle difference between the following:

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath

- Visit reason: Shortness of breath/HF

People with HF can be short of breath for lots of reasons. HF exacerbation comes immediately to mind and it should. But there are obviously lots of answers to that “What else could this be?” question: pneumonia, pneumothorax, heart attack, COPD, and, of course, pulmonary embolism (PE).

The authors leveraged the nationwide VA database, allowing them to examine data from over 100,000 patients presenting to various VA EDs with shortness of breath. They then looked for particular tests – D-dimer, CT chest with contrast, V/Q scan, lower-extremity Doppler — that would suggest that the doctor was thinking about PE. The question, then, is whether mentioning HF in that little “visit reason” section would influence the likelihood of testing for PE.

I know what you’re thinking: Not everyone who is short of breath needs an evaluation for PE. And the authors did a nice job accounting for a variety of factors that might predict a PE workup: malignancy, recent surgery, elevated heart rate, low oxygen saturation, etc. Of course, some of those same factors might predict whether that triage nurse will write HF in the visit reason section. All of these things need to be accounted for statistically, and were, but – the unofficial Impact Factor motto reminds us that “there are always more confounders.”

But let’s dig into the results. I’m going to give you the raw numbers first. There were 4,392 people with HF whose visit reason section, in addition to noting shortness of breath, explicitly mentioned HF. Of those, 360 had PE testing and two had a PE diagnosed during that ED visit. So that’s around an 8% testing rate and a 0.5% hit rate for testing. But 43 people, presumably not tested in the ED, had a PE diagnosed within the next 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were present at the ED visit, that means the ED missed 95% of the PEs in the group with that HF label attached to them.

Let’s do the same thing for those whose visit reason just said “shortness of breath.”

Of the 103,627 people in that category, 13,886 were tested for PE and 231 of those tested positive. So that is an overall testing rate of around 13% and a hit rate of 1.7%. And 1,081 of these people had a PE diagnosed within 30 days. Assuming that those PEs were actually present at the ED visit, the docs missed 79% of them.

There’s one other thing to notice from the data: The overall PE rate (diagnosed by 30 days) was basically the same in both groups. That HF label does not really flag a group at lower risk for PE.

Yes, there are a lot of assumptions here, including that all PEs that were actually there in the ED got caught within 30 days, but the numbers do paint a picture. In this unadjusted analysis, it seems that the HF label leads to less testing and more missed PEs. Classic anchoring bias.

The adjusted analysis, accounting for all those PE risk factors, really didn’t change these results. You get nearly the same numbers and thus nearly the same conclusions.

Now, the main missing piece of this puzzle is in the mind of the clinician. We don’t know whether they didn’t consider PE or whether they considered PE but thought it unlikely. And in the end, it’s clear that the vast majority of people in this study did not have PE (though I suspect not all had a simple HF exacerbation). But this type of analysis is useful not only for the empiric evidence of the clinical impact of anchoring bias but because of the fact that it reminds us all to ask that all-important question: What else could this be?

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advances in endohepatology

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

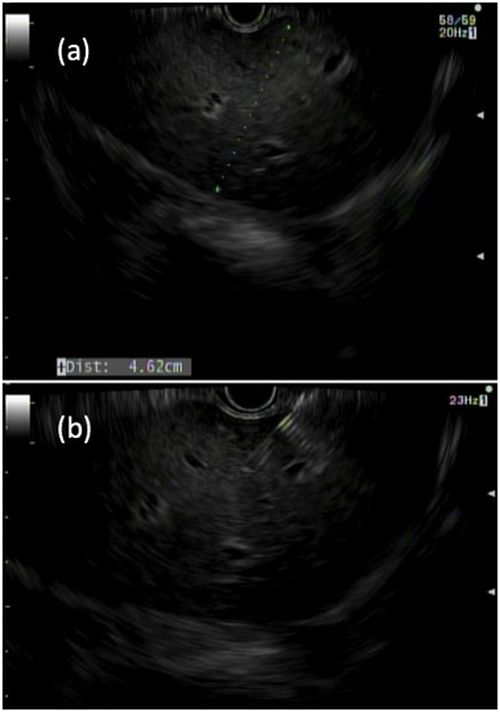

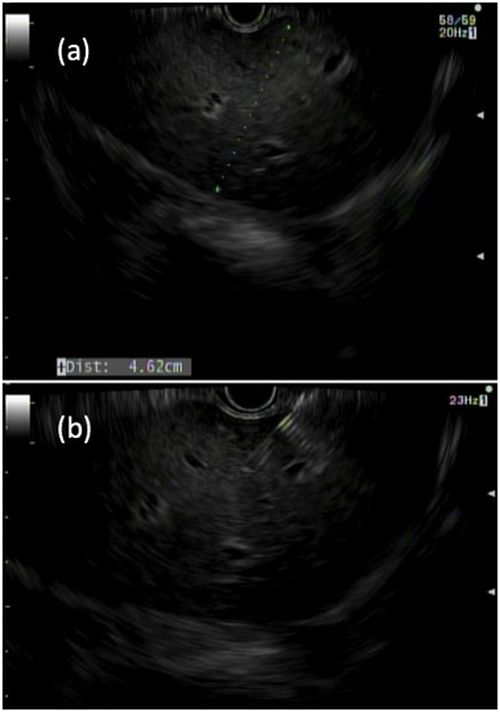

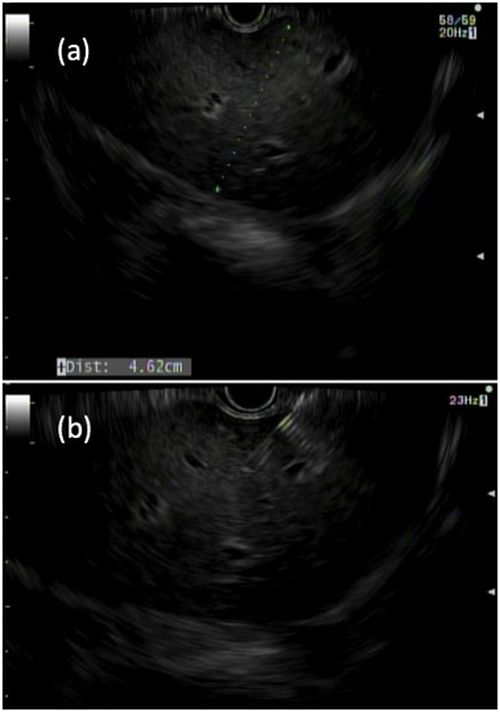

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

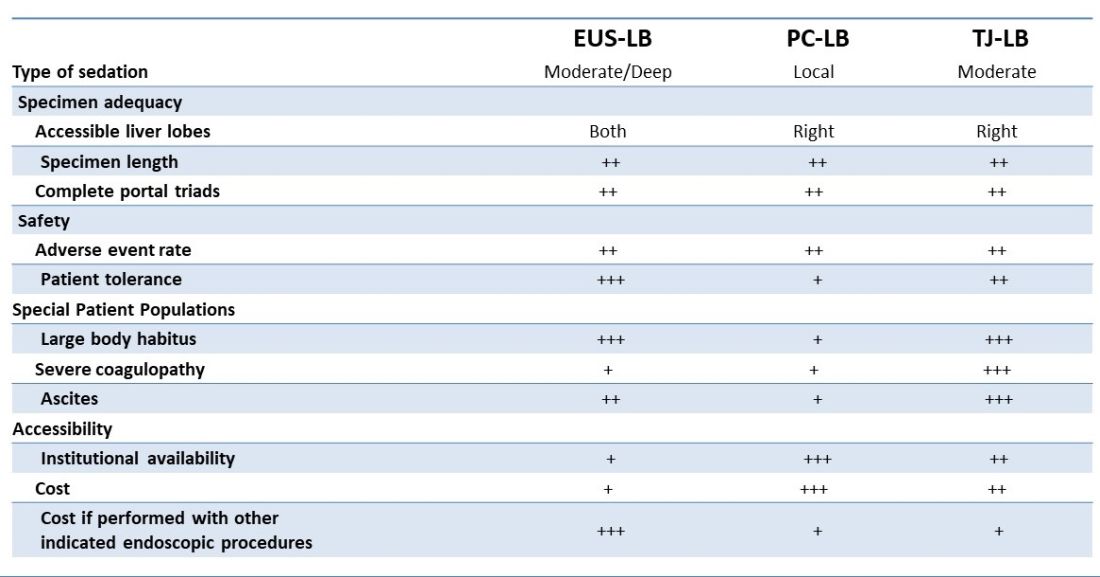

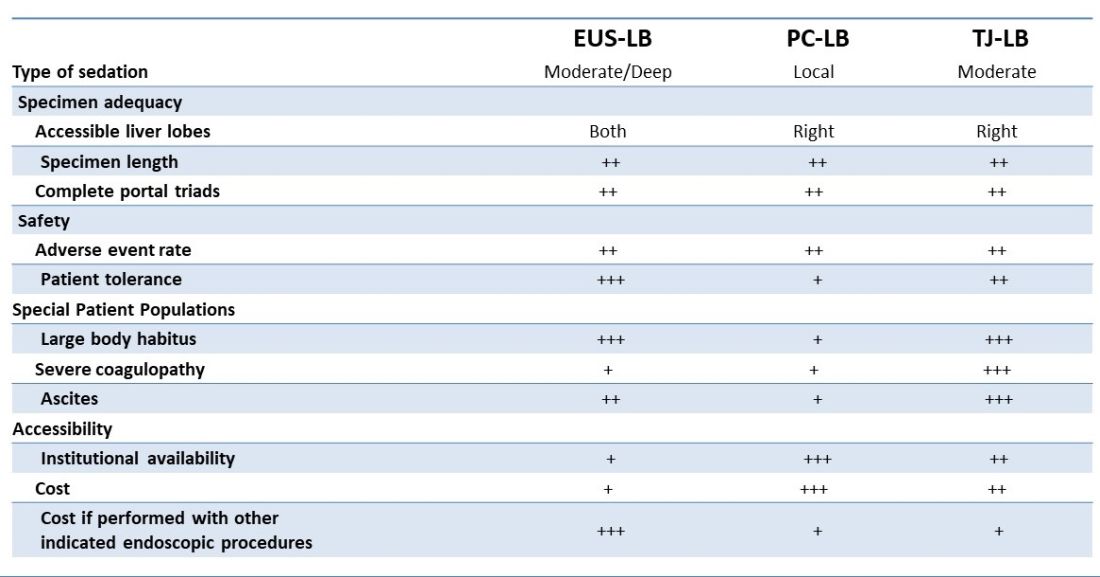

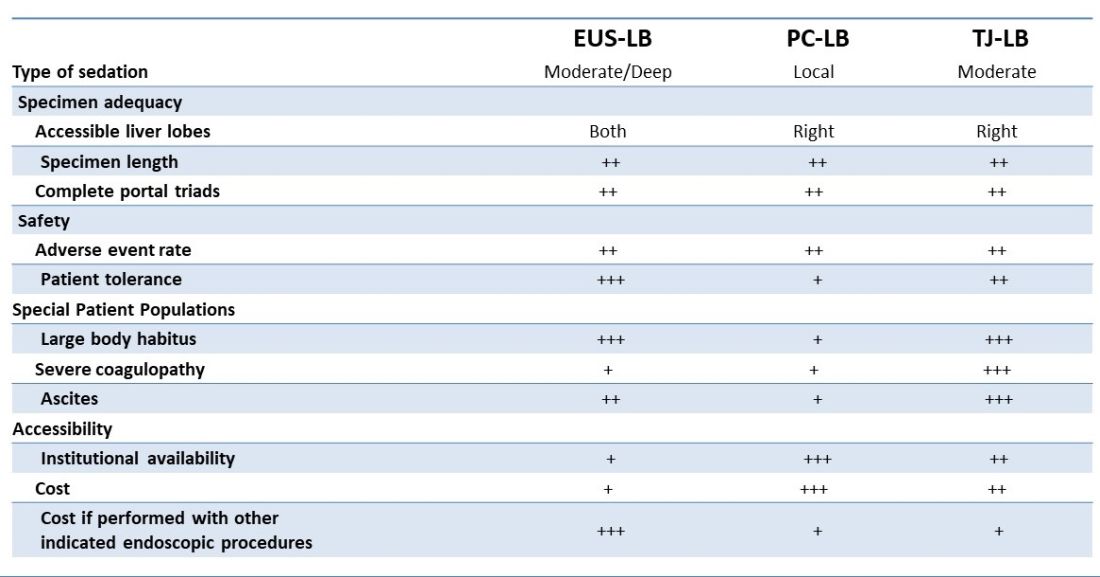

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

Triple-agonist retatrutide hits new weight loss highs

SAN DIEGO – New designer molecules that target weight loss via multiple mechanisms continue to raise the bar of how many pounds people with overweight or obesity can lose.

Retatrutide (Eli Lilly), an investigational agent that combines agonism to three key hormones that influence eating and metabolism into a single molecule, safely produced weight loss at levels never seen before in a pair of phase 2 studies that together randomized more than 600 people with overweight or obesity, with or without type 2 diabetes.

Among 338 randomized people with overweight or obesity and no type 2 diabetes,

Among 281 randomized people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, the same dose of retatrutide produced a nearly 17% cut in weight from baseline after 36 weeks of treatment.

Never before seen weight loss

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, who led the obesity study, said during a press briefing at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The average weight loss by study participants taking high-dose retatrutide in the two studies “is really impressive, way beyond my wildest dreams,” said Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, an obesity and diabetes researcher at University College Dublin, Ireland, who was not involved with the retatrutide studies.

And Robert A. Gabbay, MD, chief scientific and medical officer of the ADA, called the results “stunning,” and added, “we are now witnessing the first triple-hormone combination being highly effective for not only weight loss but liver disease and diabetes.”

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the obesity study showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those with at least 10% of their liver volume as fat at study entry); that figure increased to about 90% of people on these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the meeting.

Adding glucagon agonism ups liver-fat clearance

“When you add glucagon activity,” one of the three agonist actions of retatrutide, “liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” said Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“To my knowledge, no mono-agonist of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor [such as semaglutide or liraglutide] produces more than 50% clearance of liver fat,” added Dr. Kaplan.

The separate, randomized study of people with type 2 diabetes showed that in addition to producing an unprecedented average level of weight loss at the highest retatrutide dose, the agent also produced an average reduction from baseline levels of A1c of about 2 percentage points, an efficacy roughly comparable to maximum doses of the most potent GLP-1 mono-agonist semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk), as well as by tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Eli Lilly), a dual agonist for the GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who presented the results from the type 2 diabetes study of retatrutide.

For the obesity study, people with a body mass index of 27-50 kg/m2 and no diabetes were randomized to placebo or any of four retatrutide target dosages using specified dose-escalation protocols. Participants were an average of 48 years old, and by design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-related pattern. (Weight loss averaged about 2% among the 70 controls who received placebo.)

Twenty-six percent without diabetes lost at least 30% of body weight

Every person who escalated to receive the 8-mg or 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide lost at least 5% of their bodyweight after 48 weeks, 83% of those taking the 12-mg dose lost at least 15%, 63% of those on the 12-mg dose lost at least 20%, and 26% of those on the highest dose lost at least 30% of their starting bodyweight, reported Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The highest dose was also associated with an average 40% relative reduction in triglyceride levels from baseline and an average 22% relative drop in LDL cholesterol levels.

The results were simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The incidence of serious adverse events with retatrutide was low, similar to the rate in those who received placebo, and showed no dose relationship.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal, in as many as 16% of those on the highest dose; these were mild to moderate in severity and usually occurred during dose escalation. In general, adverse events were comparable to what is seen with a GLP-1 agonist or the dual agonist tirzepatide, Dr. Jastreboff said.

A1c normalization in 26% at the highest dose

A similar safety pattern occurred in the study of people with type 2 diabetes, which randomized people with an average A1c of 8.3% and an average BMI of 35.0 kg/m2. After 36 weeks of treatment, the 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide led to normalization of A1c < 5.7% in 27% of people and A1c ≤ 6.5% in 77%.

“The number of people we were able to revert to a normal A1c was impressive,” said Dr. Rosenstock. These results were simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

The additional findings on liver-fat mobilization in people without diabetes enrolled in the obesity study are notable because no agent currently has labeling from the Food and Drug Administration for the indication of reducing excess liver fat, said Dr. Kaplan.

The researchers measured liver fat at baseline and then during treatment using MRI.

“With the level of fat clearance from the liver that we see with retatrutide it is highly likely that we’ll also see improvements in liver fibrosis” in retatrutide-treated patients, Dr. Kaplan predicted.

Next up for retatrutide is testing in pivotal trials, including the TRIUMPH-3 trial that will enroll about 1,800 people with severe obesity and cardiovascular disease, with findings expected toward the end of 2025.

The retatrutide studies are sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Jastreboff, Dr. Rosenstock, Dr. Kaplan, and Dr. Le Roux have reported financial relationships with Eli Lilly as well as other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – New designer molecules that target weight loss via multiple mechanisms continue to raise the bar of how many pounds people with overweight or obesity can lose.

Retatrutide (Eli Lilly), an investigational agent that combines agonism to three key hormones that influence eating and metabolism into a single molecule, safely produced weight loss at levels never seen before in a pair of phase 2 studies that together randomized more than 600 people with overweight or obesity, with or without type 2 diabetes.

Among 338 randomized people with overweight or obesity and no type 2 diabetes,

Among 281 randomized people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, the same dose of retatrutide produced a nearly 17% cut in weight from baseline after 36 weeks of treatment.

Never before seen weight loss

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, who led the obesity study, said during a press briefing at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The average weight loss by study participants taking high-dose retatrutide in the two studies “is really impressive, way beyond my wildest dreams,” said Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, an obesity and diabetes researcher at University College Dublin, Ireland, who was not involved with the retatrutide studies.

And Robert A. Gabbay, MD, chief scientific and medical officer of the ADA, called the results “stunning,” and added, “we are now witnessing the first triple-hormone combination being highly effective for not only weight loss but liver disease and diabetes.”

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the obesity study showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those with at least 10% of their liver volume as fat at study entry); that figure increased to about 90% of people on these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the meeting.

Adding glucagon agonism ups liver-fat clearance

“When you add glucagon activity,” one of the three agonist actions of retatrutide, “liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” said Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“To my knowledge, no mono-agonist of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor [such as semaglutide or liraglutide] produces more than 50% clearance of liver fat,” added Dr. Kaplan.

The separate, randomized study of people with type 2 diabetes showed that in addition to producing an unprecedented average level of weight loss at the highest retatrutide dose, the agent also produced an average reduction from baseline levels of A1c of about 2 percentage points, an efficacy roughly comparable to maximum doses of the most potent GLP-1 mono-agonist semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk), as well as by tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Eli Lilly), a dual agonist for the GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who presented the results from the type 2 diabetes study of retatrutide.

For the obesity study, people with a body mass index of 27-50 kg/m2 and no diabetes were randomized to placebo or any of four retatrutide target dosages using specified dose-escalation protocols. Participants were an average of 48 years old, and by design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-related pattern. (Weight loss averaged about 2% among the 70 controls who received placebo.)

Twenty-six percent without diabetes lost at least 30% of body weight

Every person who escalated to receive the 8-mg or 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide lost at least 5% of their bodyweight after 48 weeks, 83% of those taking the 12-mg dose lost at least 15%, 63% of those on the 12-mg dose lost at least 20%, and 26% of those on the highest dose lost at least 30% of their starting bodyweight, reported Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The highest dose was also associated with an average 40% relative reduction in triglyceride levels from baseline and an average 22% relative drop in LDL cholesterol levels.

The results were simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The incidence of serious adverse events with retatrutide was low, similar to the rate in those who received placebo, and showed no dose relationship.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal, in as many as 16% of those on the highest dose; these were mild to moderate in severity and usually occurred during dose escalation. In general, adverse events were comparable to what is seen with a GLP-1 agonist or the dual agonist tirzepatide, Dr. Jastreboff said.

A1c normalization in 26% at the highest dose

A similar safety pattern occurred in the study of people with type 2 diabetes, which randomized people with an average A1c of 8.3% and an average BMI of 35.0 kg/m2. After 36 weeks of treatment, the 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide led to normalization of A1c < 5.7% in 27% of people and A1c ≤ 6.5% in 77%.

“The number of people we were able to revert to a normal A1c was impressive,” said Dr. Rosenstock. These results were simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

The additional findings on liver-fat mobilization in people without diabetes enrolled in the obesity study are notable because no agent currently has labeling from the Food and Drug Administration for the indication of reducing excess liver fat, said Dr. Kaplan.

The researchers measured liver fat at baseline and then during treatment using MRI.

“With the level of fat clearance from the liver that we see with retatrutide it is highly likely that we’ll also see improvements in liver fibrosis” in retatrutide-treated patients, Dr. Kaplan predicted.

Next up for retatrutide is testing in pivotal trials, including the TRIUMPH-3 trial that will enroll about 1,800 people with severe obesity and cardiovascular disease, with findings expected toward the end of 2025.

The retatrutide studies are sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Jastreboff, Dr. Rosenstock, Dr. Kaplan, and Dr. Le Roux have reported financial relationships with Eli Lilly as well as other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – New designer molecules that target weight loss via multiple mechanisms continue to raise the bar of how many pounds people with overweight or obesity can lose.

Retatrutide (Eli Lilly), an investigational agent that combines agonism to three key hormones that influence eating and metabolism into a single molecule, safely produced weight loss at levels never seen before in a pair of phase 2 studies that together randomized more than 600 people with overweight or obesity, with or without type 2 diabetes.

Among 338 randomized people with overweight or obesity and no type 2 diabetes,

Among 281 randomized people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, the same dose of retatrutide produced a nearly 17% cut in weight from baseline after 36 weeks of treatment.

Never before seen weight loss

“I have never seen weight loss at this level” after nearly 1 year of treatment, Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD, who led the obesity study, said during a press briefing at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The average weight loss by study participants taking high-dose retatrutide in the two studies “is really impressive, way beyond my wildest dreams,” said Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, an obesity and diabetes researcher at University College Dublin, Ireland, who was not involved with the retatrutide studies.

And Robert A. Gabbay, MD, chief scientific and medical officer of the ADA, called the results “stunning,” and added, “we are now witnessing the first triple-hormone combination being highly effective for not only weight loss but liver disease and diabetes.”

A prespecified subgroup analysis of the obesity study showed that at both 8-mg and 12-mg weekly doses, 24 weeks of retatrutide produced complete resolution of excess liver fat (hepatic steatosis) in about 80% of the people eligible for the analysis (those with at least 10% of their liver volume as fat at study entry); that figure increased to about 90% of people on these doses after 48 weeks, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, reported during a separate presentation at the meeting.

Adding glucagon agonism ups liver-fat clearance

“When you add glucagon activity,” one of the three agonist actions of retatrutide, “liver-fat clearance goes up tremendously,” said Dr. Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“To my knowledge, no mono-agonist of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor [such as semaglutide or liraglutide] produces more than 50% clearance of liver fat,” added Dr. Kaplan.

The separate, randomized study of people with type 2 diabetes showed that in addition to producing an unprecedented average level of weight loss at the highest retatrutide dose, the agent also produced an average reduction from baseline levels of A1c of about 2 percentage points, an efficacy roughly comparable to maximum doses of the most potent GLP-1 mono-agonist semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk), as well as by tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Eli Lilly), a dual agonist for the GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors.

“No other medication has shown an average 17% reduction from baseline bodyweight after 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Julio Rosenstock, MD, director of the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City, Texas, who presented the results from the type 2 diabetes study of retatrutide.

For the obesity study, people with a body mass index of 27-50 kg/m2 and no diabetes were randomized to placebo or any of four retatrutide target dosages using specified dose-escalation protocols. Participants were an average of 48 years old, and by design, 52% were men. (The study sought to enroll roughly equal numbers of men and women.) Average BMI at study entry was 37 kg/m2.

Weight loss levels after 24 and 48 weeks of retatrutide treatment followed a clear dose-related pattern. (Weight loss averaged about 2% among the 70 controls who received placebo.)

Twenty-six percent without diabetes lost at least 30% of body weight

Every person who escalated to receive the 8-mg or 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide lost at least 5% of their bodyweight after 48 weeks, 83% of those taking the 12-mg dose lost at least 15%, 63% of those on the 12-mg dose lost at least 20%, and 26% of those on the highest dose lost at least 30% of their starting bodyweight, reported Dr. Jastreboff, director of the Yale Obesity Research Center of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

The highest dose was also associated with an average 40% relative reduction in triglyceride levels from baseline and an average 22% relative drop in LDL cholesterol levels.

The results were simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The incidence of serious adverse events with retatrutide was low, similar to the rate in those who received placebo, and showed no dose relationship.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal, in as many as 16% of those on the highest dose; these were mild to moderate in severity and usually occurred during dose escalation. In general, adverse events were comparable to what is seen with a GLP-1 agonist or the dual agonist tirzepatide, Dr. Jastreboff said.

A1c normalization in 26% at the highest dose

A similar safety pattern occurred in the study of people with type 2 diabetes, which randomized people with an average A1c of 8.3% and an average BMI of 35.0 kg/m2. After 36 weeks of treatment, the 12-mg weekly dose of retatrutide led to normalization of A1c < 5.7% in 27% of people and A1c ≤ 6.5% in 77%.

“The number of people we were able to revert to a normal A1c was impressive,” said Dr. Rosenstock. These results were simultaneously published online in The Lancet.

The additional findings on liver-fat mobilization in people without diabetes enrolled in the obesity study are notable because no agent currently has labeling from the Food and Drug Administration for the indication of reducing excess liver fat, said Dr. Kaplan.