User login

Incident Database

Recognition that healthcare carries considerable risks of patient injury has focused efforts on identifying problems before they occur, and understanding the root causes of those problems that do occur to prevent them from happening again.1 To further these efforts, a Joint Commission (JC) standard requires hospitals to review sentinel events (SE).2 Reviews must develop a timely, thorough, and credible root cause analysis (RCA), implement action plans to reduce risk, and monitor the effectiveness of implemented improvements.3

Ideally, hospitals would summarize their experiences with SE reviews, identify high‐risk activities and patients, institute system changes to prevent SE recurrences, and share their findings with other healthcare organizations to help them avoid similar patient injuries.1 In support of this last goal, the JC maintains a voluntary database system that allows hospitals to report their SE analyses for other facilities to review and institute preventative actions.

Unfortunately, the reality of SE reviews does not match their ideals for improving patient safety.4 Healthcare organizations often describe their review process as less than credible and note a need for ongoing oversight to maintain the reviews' effectiveness.5 The JC voluntary reporting system captures less than 1% of the SEs that occur nationally,2 because hospitals perceive barriers to external reporting.1 If healthcare organizations decide against reporting externally, they can create their own internal systems to aggregate and summarize SEs, but few such systems exist. A major impediment to designing internal systems is the absence of universally endorsed nomenclature for safety‐related events.6, 7 Poorly aligned terminology and subjective conceptualizations for safety incidents impede the aggregation of SEs, comparisons between facilities, and trend analyses for tracking SE patterns.

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) World Alliance for Patient Safety, in collaboration with the JC, began developing an International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) to provide healthcare organizations a consistent conceptual model for safety incidents and promote their classification by a standardized taxonomy.810 Although this system has promise for allowing standardization, data aggregation, analysis, and learning between institutions,11 integration of the ICPS conceptual model into an SE decision support tool with summarizing and reporting features has not been reported.

This report describes our development of an intranet‐based SE reporting system, called Incident Tracker (I‐Tracker), based on the ICPS model. For our SE review groups from the 4 Providence Health Systems (PHS) Portland Service Area (PSA) hospitals, the I‐Tracker system offers a tool to guide efforts in developing RCAs and action plans in alignment with the ICPS framework. The system includes scripts that automatically generate and distribute standardized reports of individual and aggregated SEs. The objectives of this project were to report our experience with developing a flexible and accessible intranet‐based system that assists RCA participants in conforming to the ICPS framework and oversight safety staff in summarizing and reporting root cause analyses.

METHODS

The 4 PSA hospitals have 1083 licensed beds and perform SE reviews with a centralized process that reports results to a Community Governing Board. An ad hoc team for each SE performs the RCAs. The SE groups report RCAs and action plans in an unstructured format that varies for each event. A paper file is maintained for each SE report, but a system for aggregating reports to track trends, disseminating SE trends, or monitoring the completion or effectiveness of action plans is not available.

We designed a system to achieve the following objectives:

-

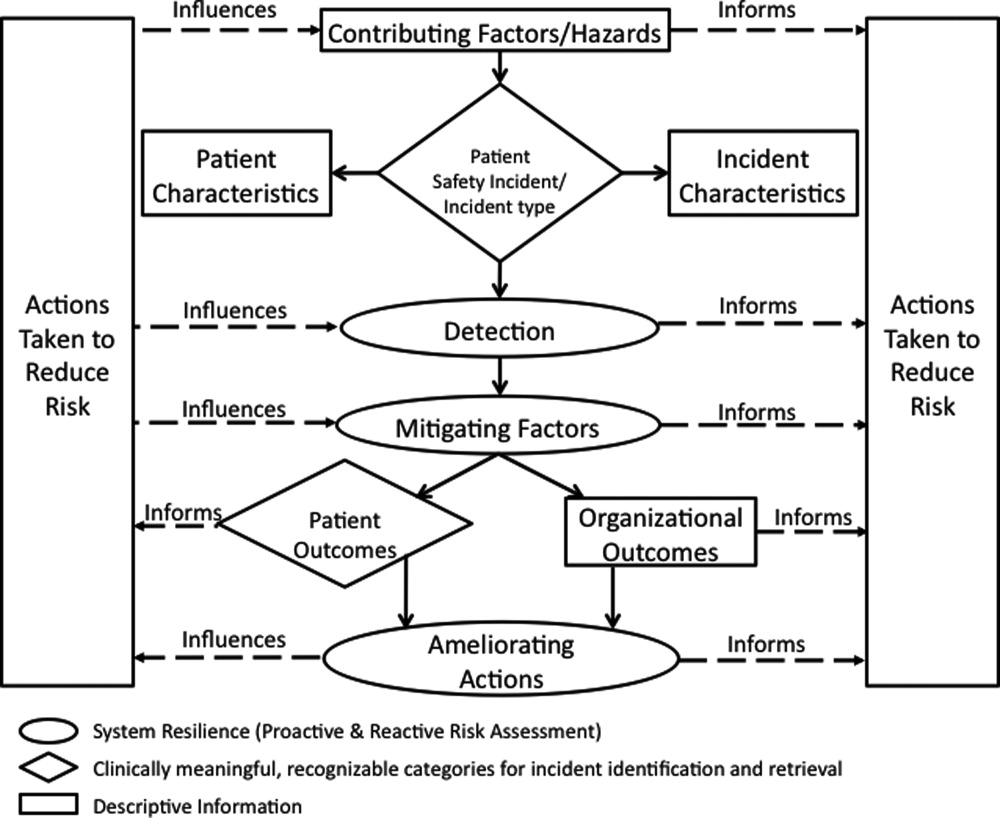

Apply the ICPS framework (Figure 1) and taxonomy of terms to SE analyses;

-

Provide a computer‐based tool to assist review groups and quality staff to perform their SE reviews and data collection in alignment with the ICPS framework;

-

Create an intranet‐based database that captures elements of the reviews, RCAs, and action plans with the use of drop‐down lists, help windows, windows with live access to Internet educational resources and tools, decision support tools, default entries, and audio prompts to streamline data entry;

-

Generate a suite of standardized reports customized for different audiences that can be accessed online and printed from the database with automated scripts;

-

Produce intranet‐based summaries of aggregated events to identify common causes and disseminate observed patterns and action plans to other PSA hospitals.

We selected FileMaker Pro 11 Advanced (FMP11) for authoring and maintaining the decision support tool and database, and FileMaker Pro Server 11 Advanced (FMPS11) (Filemaker, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) for hosting the system, because it provides intranet access and tools for updating the system by personnel with minimal programming experience. End users can view and enter data through layouts that display only the information allowed by the user's login password and access privileges, with external authentication by Active Directory and Open Directory technology. Staff who author and manage the database do so through client FMP11 software loaded on a computer that provides remote server access.

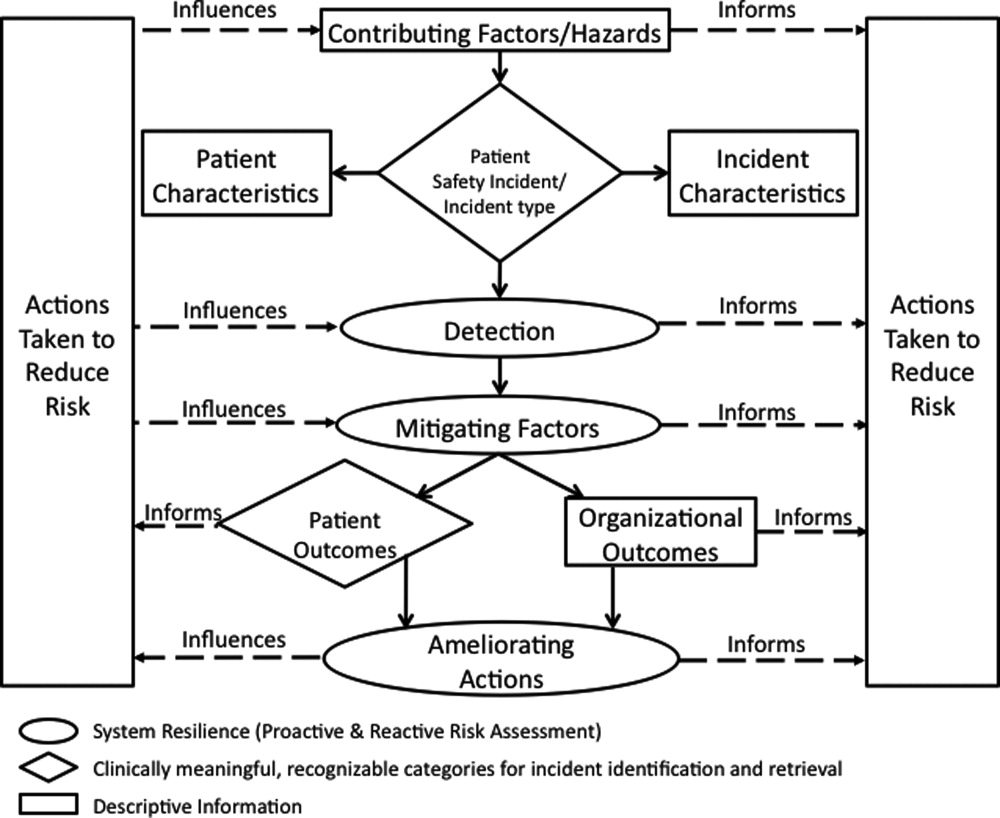

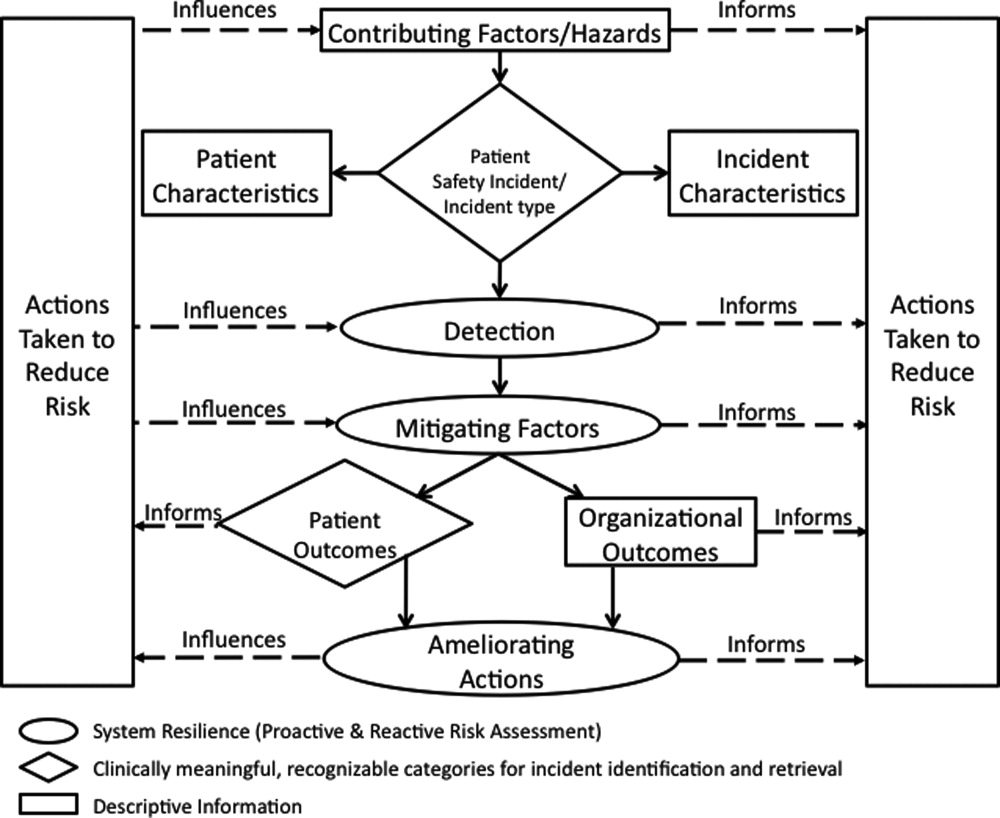

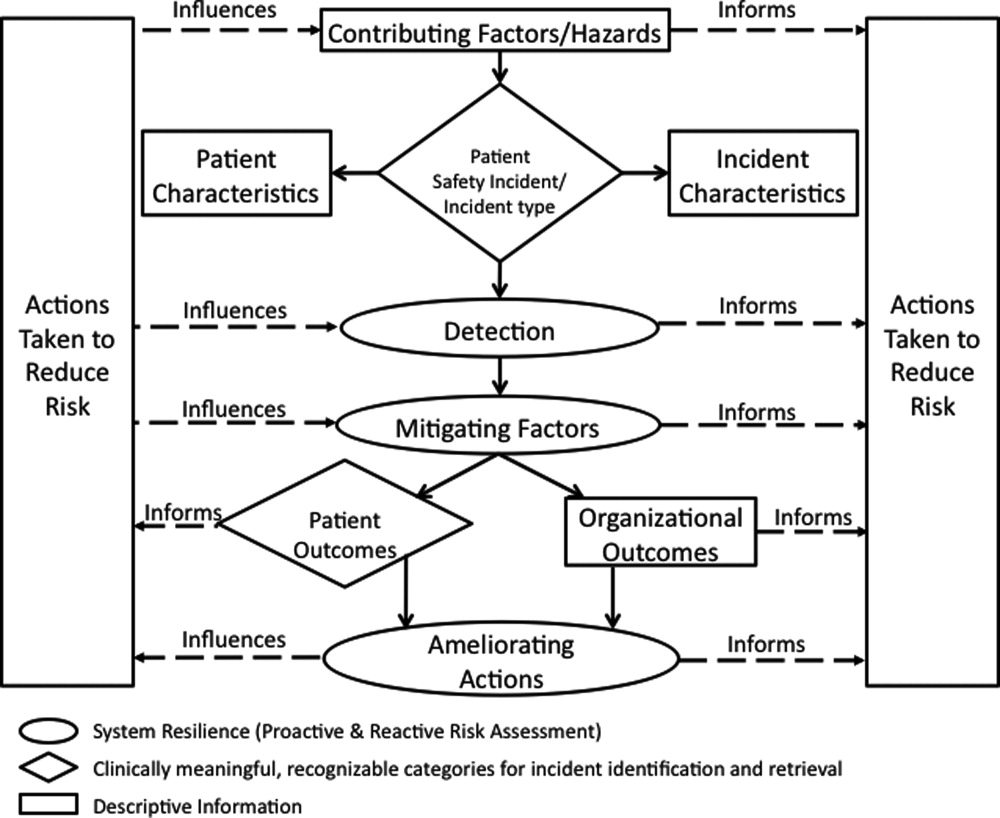

The I‐Tracker system was authored using the ICPS definitions for the 48 preferred terms for safety incidents and the ICPS conceptual framework.8 The conceptual framework consists of 10 major incident domains, that include incident type, patient outcomes, patient characteristics, incident characteristics, contributing factors and hazards, organizational outcomes, detection, mitigating factors, ameliorating actions, and actions taken to reduce risk (Figure 1).11 The framework is applicable to all hospital safety incidents, but we limited I‐Tracker to SEs because our hospitals had completed comprehensive reviews and action plans only for these more serious events. The literature on the ICPS framework812 was carefully reviewed to identify the specific data fields that were recommended by ICPS developers to be included under each of the 10 major classification domains. In most instances, data fields existed only in the body of these reports. Article texts, however, provided sufficient descriptions of these data fields to allow their translation into data entry fields in I‐Tracker with accompanying help windows and explanations to guide I‐Tracker users. Sixty ICPS data fields were programmed into I‐Tracker, with another 120 fields that allowed entry of descriptions and explanations of the ICPS data field entries. For instance, an entry of Yes into an ICPS data field that queried Was there a systems problem of an external organization other than a Providence entity opens a Describe field that allows a brief description of the problem, and an additional Details field that allows a longer explanation of the problem if necessary. The brief Describe field contents populate an automatically generated fishbone diagram.

The authors and quality staff translated the most recent 15 SE reviews into ICPS terms and classifications, and entered the results into I‐Tracker as it was being developed, to assist system design and programming of the system. The authors noted during data entry which of the 10 ICPS major domains had not been analyzed by the previous 15 reviews. Because existing reports were unstructured with considerable variation in style and usage of terms, the authors and quality staff made group decisions regarding how to cross‐walk existing information into the standardized ICPS data fields.

RESULTS

In developing I‐Tracker, the authors and quality staff observed that the ICPS framework and recommended data fields were logical and straightforward to learn. Although it was difficult to find the definitions of specific ICPS data fields within the 10 major domains in the text of retrieved articles, these fields could be readily cross‐walked into I‐Tracker data entry fields. Translating existing SE reports into I‐Tracker classifications, however, presented considerable challenges because of the unstructured, discursive, and variable nature of our SE review and reports. The authors and staff spent 1 to 2 hours conferring over each report to make judgments as to which elements of the review would be entered into which I‐Tracker data fields. Once the authors and staff translated existing reports into ICPS terms, actual data entry into I‐Tracker took typically less than 30 minutes for each review. We found that none of our 15 SE reviews included information on the following ICPS major domains: detection, mitigating factors, and ameliorating actions. We also observed that many ICPS data fields were not assessed, such as patient contributions to errors and external organization's contributions to a safety incident.

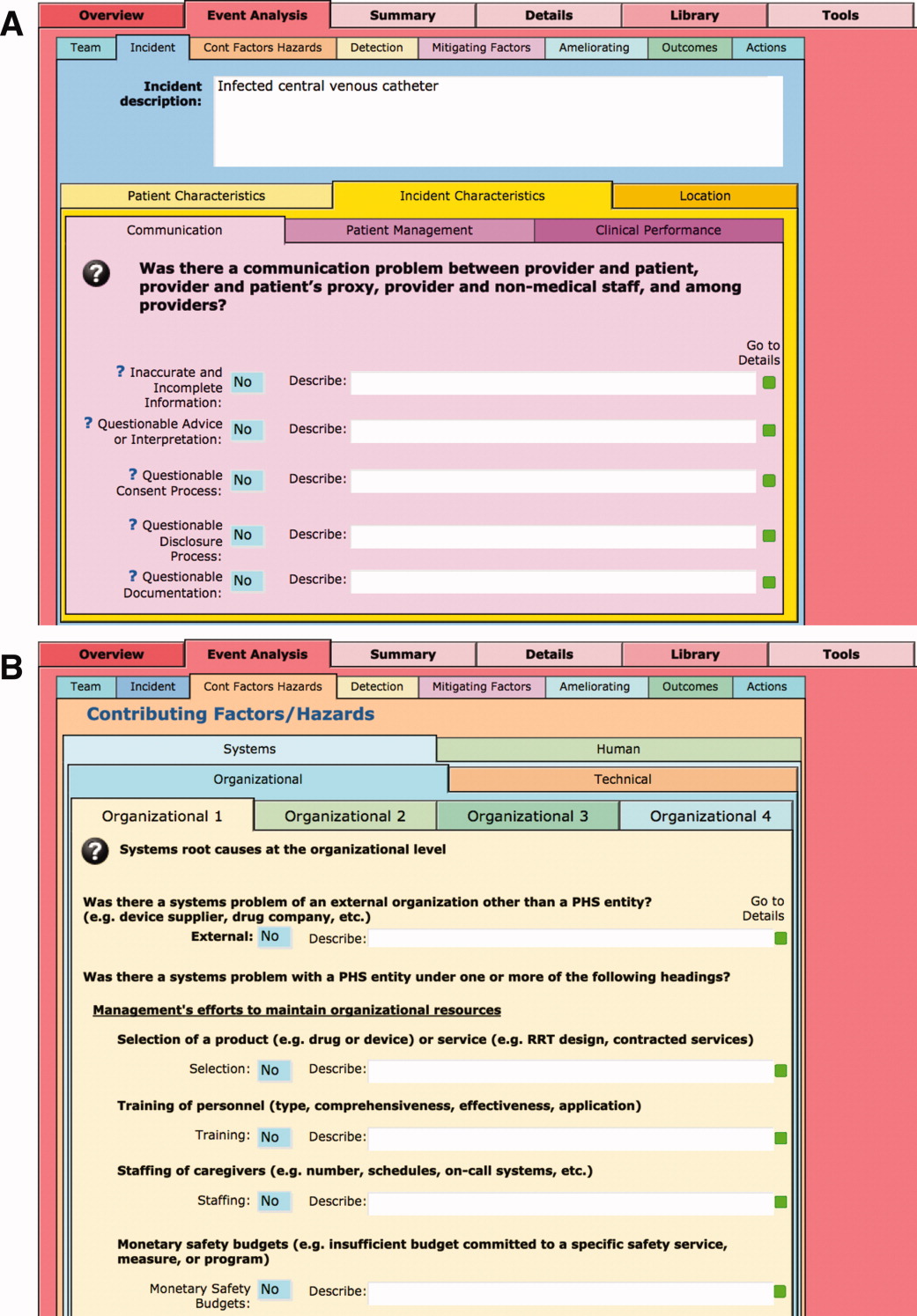

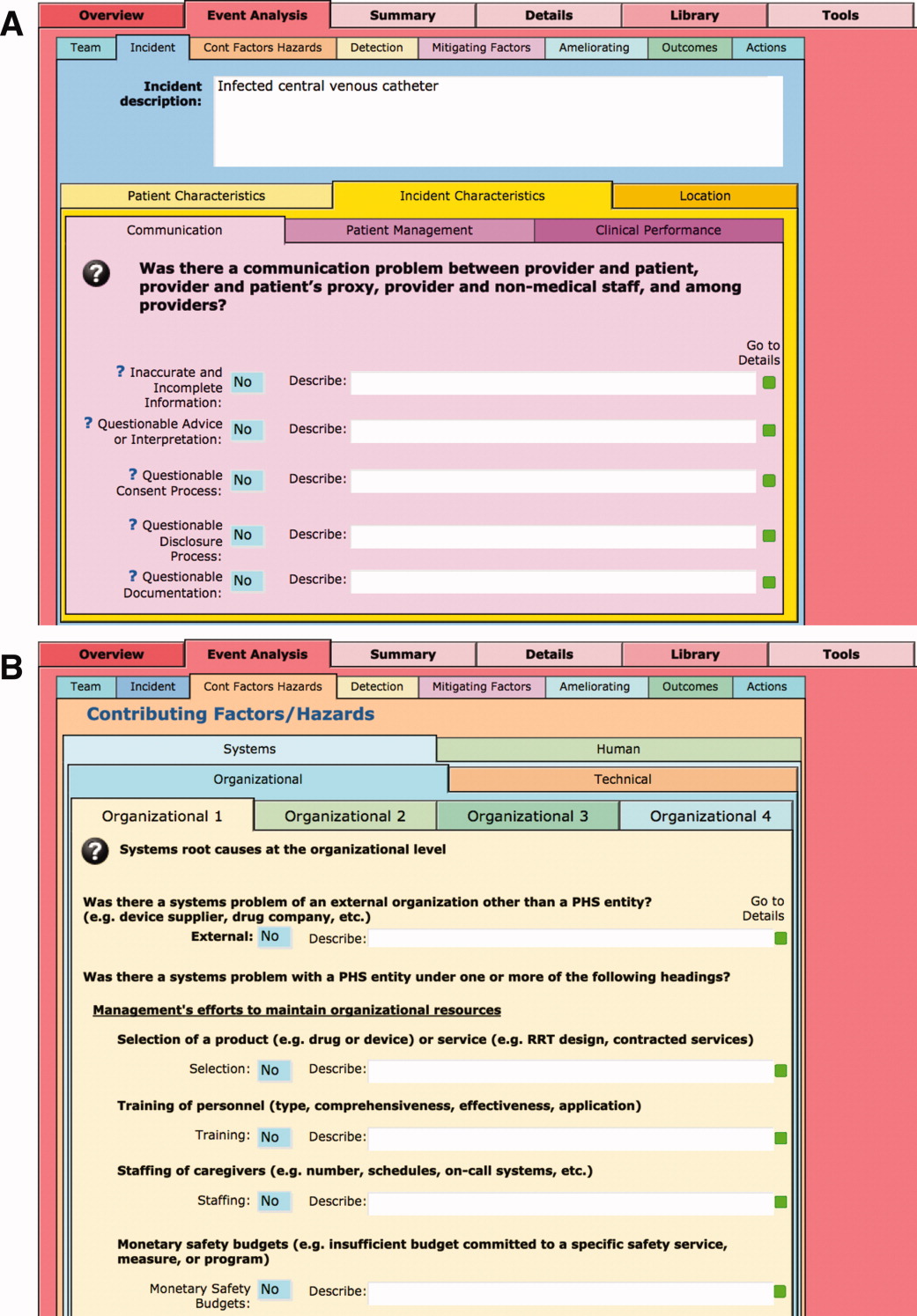

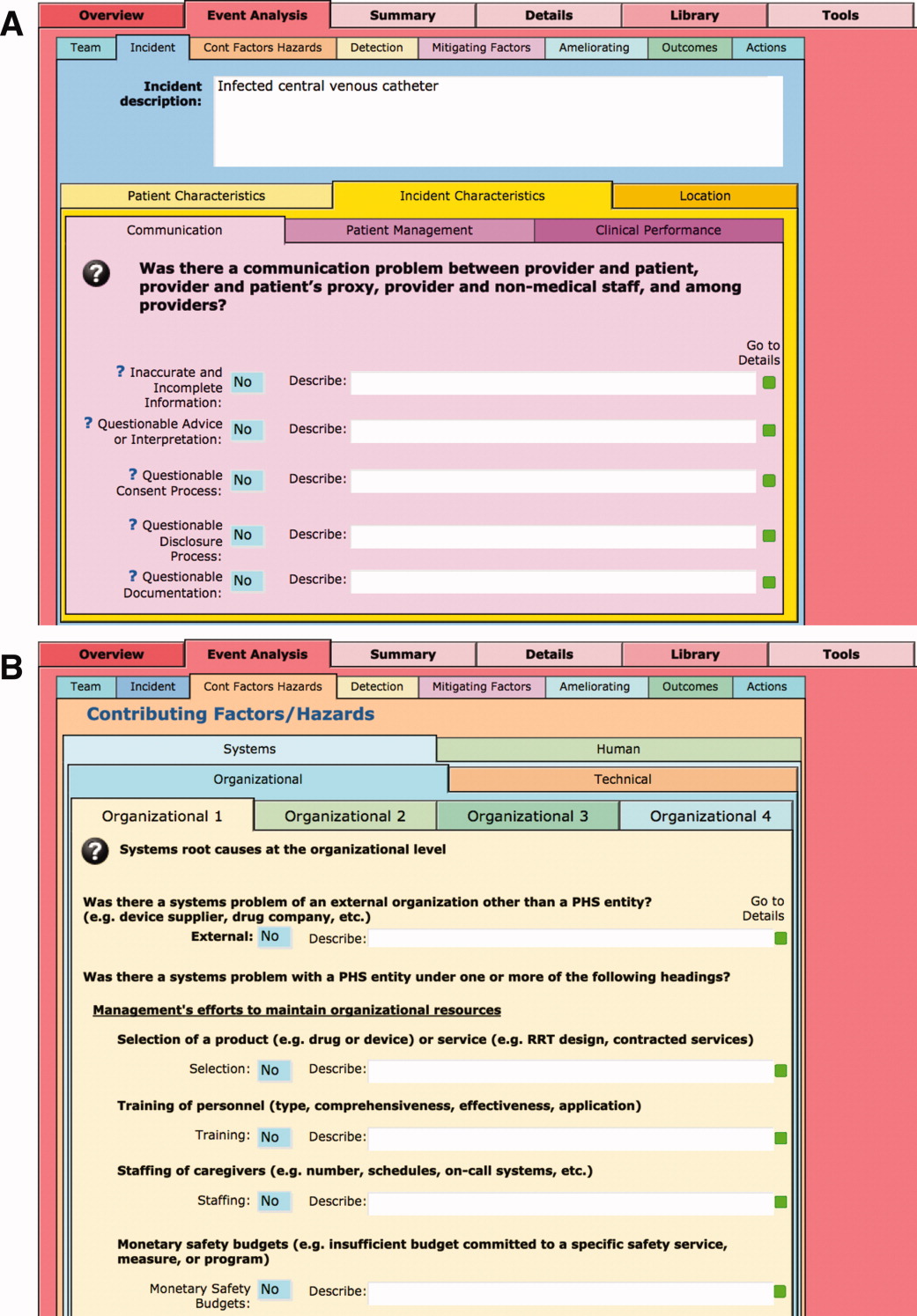

The latest version of I‐Tracker receives and displays information at the individual patient level. Records are shown onscreen with different screen layouts depending on the viewer's login security clearance. Hospital safety staff have full access to view and enter data on the initial layout, which displays patient demographic information and folder tabs that navigate when clicked to other database fields (Figure 2). Viewers with lower security clearance either view the same opening screen, but have limited access to other screens, or view a different opening screen designed to meet their specific needs. All screens provide definitions of terms and information to assist data entry, buttons that navigate to help pages, pop‐up windows that provide tips, and buttons that trigger brief audio explanations. Most fields use drop‐down lists to standardize data entry around the ICPS definitions, with default values entered into many fields to streamline data entry. A list view allows review of all patients and quick access to an individual patient's record. All fields and combinations of fields with Boolean rules are searchable within the database.

I‐Tracker has features that support SE review groups in beginning an SE review by providing them a paper form or electronic interface by way of a portable computer or tablet device, that guides their discussions and analyses toward providing conclusions that can be entered into the database fields, thereby aligning their deliberations with the ICPS conceptual framework. The same resource is available within the database online for those groups who would prefer to use computer prompts and enter data directly into the database as they proceed through their analyses. Some layouts contain windows that port live views from external Web sites (eg, JC RCA resources) that provide participants of RCA groups with tools to assist their work. FMP11 allows users to access the database by portable computers or handheld tablet devices using the hospitals' WiFi network.

A report screen allows automatic generation of different printouts of individual or aggregate summary reports. A Comprehensive Report includes all of the data fields included in the ICPS conceptual framework. Other reports present subsets of data depending on the user's needs and access privileges. The FMPS11 database allows printing the reports to paper or Portable Document Format (pdf), exporting data into an Excel spreadsheet, or e‐mailing reports to recipients from within I‐Tracker.

Additionally, I‐Tracker functionality facilitates follow‐up and monitoring of action items developed during the RCA process in a manner that conforms to the ICPS framework. We are now developing educational resources for RCA team members to investigate the implementation of I‐Tracker into future RCAs.

DISCUSSION

I‐Tracker provides an intranet‐based tool that met the objectives of the present project. The process of entering 15 existing SE reviews and action plans from our healthcare system into I‐Tracker allowed an incremental development of the database and identified gaps in our existing RCA process. For instance, none of the previous RCAs critically appraised detection, mitigating factors, or ameliorating actions; defined the specific nature or quantified severity of patient injuries using standardized terms; distinguished between human errors and negligence; or comprehensively reported the full spectrum of underlying causes of Tracker's use of standardized terms based on the ICPS conceptual framework provided a potential resource for focusing SE reviews and producing more comprehensive RCAs and action plans in the future. I‐Tracker has additional potential to facilitate dissemination of RCAs to other facilities, both as individual incident reports and aggregated summaries as recommended by experts in patient safety.13

The deficiencies in our existing RCA analyses, identified during data entry into I‐Tracker, represent common shortcomings experienced by other healthcare organizations and summarized in a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.4 Considerable hindsight bias and prevailing concerns of the day taint the RCA process, which is time‐consuming and labor intensive, and thereby hinders comprehensive reviews. Also, our SE reviews, like others reviewed in the literature,14 focused on biologic injury to patients and omitted assessment of psychologic, organizational, social, and economic injury domains. Although SE review teams benefit from involvement of quality improvement staff who are trained in techniques and goals of RCA,15 many hospitals like ours have limited resources for fully staffing all SE reviews with trained facilitators. These SE reviews generate both quantitative and qualitative data, the latter of which hinders standardized data entry in the absence of a conceptual framework. A structured database with formative tools to guide RCAs in conformance with the ICPS framework in organizations without sufficient numbers of trained facilitators offers opportunities to produce more comprehensive, standardized, and actionable reports. To date, our quality staff and leadership have responded positively to presentations of the functional features of I‐Tracker (Table 1).

|

| Online availability of the system that allows access both from client database software loaded on Quality Office computers and through intranet browser software (Explorer, Safari, Firefox, etc) |

| Security features of encrypted software that allow full or limited views depending on the user's password security clearance and purpose for reviewing data |

| Software accessibility in authoring and managing the database, which do not require support from information technology data analysts |

| Decision support tools provided in the system to assist RCA analysis |

| System flexibility that allows scripted reporting of single SEs or multiple SE summaries within any selected timeframe |

Limitations of our report include its focus solely on the development and programming phase of I‐Tracker and the absence of information on its actual implementation. We believe, however, the development phase is important to report because it demonstrates that the ICPS framework and specific ICPS data fields are amenable to incorporation into a decision support and reporting tool, which to our knowledge has not been previously reported. We begin implementation of I‐Tracker within our organization this year and will have observations on its feasibility, acceptability, and staff training needs. As an additional limitation, we emphasize that we do not propose I‐Tracker as a solution for other organizations, because we have no plans for its commercial or public domain development. This report is intended to demonstrate, however, that commercially available software, such as FileMaker, can readily support the ICPS Framework and thereby has potential to assist RCAs and SE reporting. Other organizations may develop similar systems on other database platforms that incorporate the ICPS system into their reviews.

To implement I‐Tracker, we are now working with nursing and pharmacy leadership focus groups to develop formative tools, data collection forms, and other resources to assist their RCA efforts and data entry into the database. We also plan to apply the database tool to our residency training program to promote resident involvement in SE reviews by providing standardized, reproducible, and structured processes.16 Our 5‐state healthcare system has funded an evaluation of the implementation phase of I‐Tracker to other Providence facilities. Because the ICPS framework applies to all safety incidents beyond SEs (Table 2), a successful implementation of I‐Tracker for SEs will allow its eventual application to other types of critical incidents.

|

| Clinical administration |

| Clinical process/procedure |

| Documentation |

| Healthcare‐associated infection |

| Medication/IV fluids |

| Blood/blood products |

| Nutrition |

| Oxygen/gas/vapor |

| Medical device/equipment |

| Behavior |

| Patient accidents |

| Infrastructure/building/fixtures |

| Resources/organizational management |

The strength of this project derives from its innovative development of an intranet‐based tool that allows groups to conform their RCAs to the ICPS framework. Because the absence of a standardized classification for patient safety concepts has hindered advances in patient safety,11 we believe I‐Tracker, or decision support tools like it that use the ICPS framework, can standardize RCAs and promote dissemination and adoption of action plans.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of Judy Stenstrom, Lynette Savage, and the Portland Service Area Quality Improvement Office.

- .Reporting of adverse events.N Engl J Med.2002;347:1633–1638.

- The Joint Commission's Sentinel Event Policy: ten years of improving the quality and safety of health care.Jt Comm Perspect.2005;25(1):3–5.

- ,.Root cause analysis and nursing management responsibilities in wrong‐site surgery.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2006;25,221–225.

- ,.Root Cause Analysis.Making Health Care Safer. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/chap5.htm. Accessed May 21,2010.

- Oversight group holds RCA teams accountable.Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv.2008;15:117–118.

- .Shared meanings: preferred terms and definitions for safety and quality concepts.Med J Aust.2006;184:S41–S43.

- ,,.What do family physicians consider an error? A comparison of definitions and physician perception.BMC Fam Pract.2006;7:73.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:18–26.

- ,,,,.The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standardized terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events.Int J Qual Health Care.2005;17:95–105.

- World Health Organization. 2009 Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. Final Technical Report Version 1.1. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf. Accessed April 25,2011.

- ,,, et al.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:2–8.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: a Delphi survey.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:9–17.

- ,,.Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine.JAMA.2008;299:685–687.

- ,,,,.How can clinicians measure safety and quality in acute care?Lancet.2004;363:1061–1067.

- ,,,,.Systematic root cause analysis of adverse drug events in a tertiary referral hospital.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.2000;26:563–575.

- ,,,,,.Educational quality improvement report: outcomes from a revised morbidity and mortality format that emphasised patient safety.Postgrad Med J.2008;84:211–216.

Recognition that healthcare carries considerable risks of patient injury has focused efforts on identifying problems before they occur, and understanding the root causes of those problems that do occur to prevent them from happening again.1 To further these efforts, a Joint Commission (JC) standard requires hospitals to review sentinel events (SE).2 Reviews must develop a timely, thorough, and credible root cause analysis (RCA), implement action plans to reduce risk, and monitor the effectiveness of implemented improvements.3

Ideally, hospitals would summarize their experiences with SE reviews, identify high‐risk activities and patients, institute system changes to prevent SE recurrences, and share their findings with other healthcare organizations to help them avoid similar patient injuries.1 In support of this last goal, the JC maintains a voluntary database system that allows hospitals to report their SE analyses for other facilities to review and institute preventative actions.

Unfortunately, the reality of SE reviews does not match their ideals for improving patient safety.4 Healthcare organizations often describe their review process as less than credible and note a need for ongoing oversight to maintain the reviews' effectiveness.5 The JC voluntary reporting system captures less than 1% of the SEs that occur nationally,2 because hospitals perceive barriers to external reporting.1 If healthcare organizations decide against reporting externally, they can create their own internal systems to aggregate and summarize SEs, but few such systems exist. A major impediment to designing internal systems is the absence of universally endorsed nomenclature for safety‐related events.6, 7 Poorly aligned terminology and subjective conceptualizations for safety incidents impede the aggregation of SEs, comparisons between facilities, and trend analyses for tracking SE patterns.

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) World Alliance for Patient Safety, in collaboration with the JC, began developing an International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) to provide healthcare organizations a consistent conceptual model for safety incidents and promote their classification by a standardized taxonomy.810 Although this system has promise for allowing standardization, data aggregation, analysis, and learning between institutions,11 integration of the ICPS conceptual model into an SE decision support tool with summarizing and reporting features has not been reported.

This report describes our development of an intranet‐based SE reporting system, called Incident Tracker (I‐Tracker), based on the ICPS model. For our SE review groups from the 4 Providence Health Systems (PHS) Portland Service Area (PSA) hospitals, the I‐Tracker system offers a tool to guide efforts in developing RCAs and action plans in alignment with the ICPS framework. The system includes scripts that automatically generate and distribute standardized reports of individual and aggregated SEs. The objectives of this project were to report our experience with developing a flexible and accessible intranet‐based system that assists RCA participants in conforming to the ICPS framework and oversight safety staff in summarizing and reporting root cause analyses.

METHODS

The 4 PSA hospitals have 1083 licensed beds and perform SE reviews with a centralized process that reports results to a Community Governing Board. An ad hoc team for each SE performs the RCAs. The SE groups report RCAs and action plans in an unstructured format that varies for each event. A paper file is maintained for each SE report, but a system for aggregating reports to track trends, disseminating SE trends, or monitoring the completion or effectiveness of action plans is not available.

We designed a system to achieve the following objectives:

-

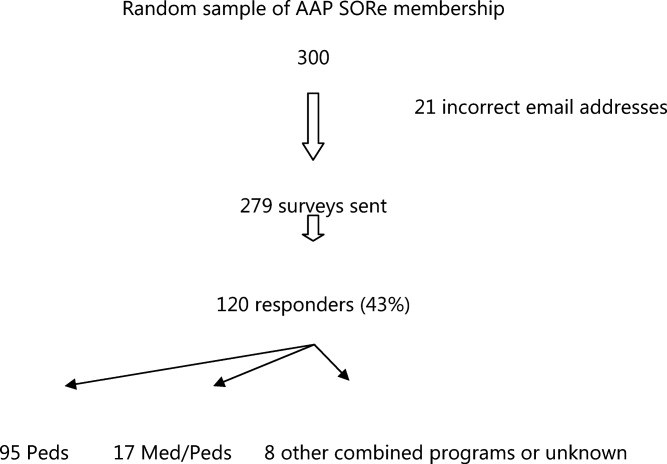

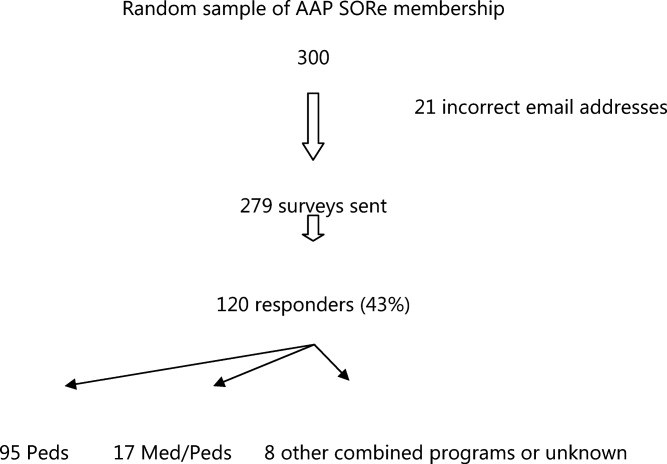

Apply the ICPS framework (Figure 1) and taxonomy of terms to SE analyses;

-

Provide a computer‐based tool to assist review groups and quality staff to perform their SE reviews and data collection in alignment with the ICPS framework;

-

Create an intranet‐based database that captures elements of the reviews, RCAs, and action plans with the use of drop‐down lists, help windows, windows with live access to Internet educational resources and tools, decision support tools, default entries, and audio prompts to streamline data entry;

-

Generate a suite of standardized reports customized for different audiences that can be accessed online and printed from the database with automated scripts;

-

Produce intranet‐based summaries of aggregated events to identify common causes and disseminate observed patterns and action plans to other PSA hospitals.

We selected FileMaker Pro 11 Advanced (FMP11) for authoring and maintaining the decision support tool and database, and FileMaker Pro Server 11 Advanced (FMPS11) (Filemaker, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) for hosting the system, because it provides intranet access and tools for updating the system by personnel with minimal programming experience. End users can view and enter data through layouts that display only the information allowed by the user's login password and access privileges, with external authentication by Active Directory and Open Directory technology. Staff who author and manage the database do so through client FMP11 software loaded on a computer that provides remote server access.

The I‐Tracker system was authored using the ICPS definitions for the 48 preferred terms for safety incidents and the ICPS conceptual framework.8 The conceptual framework consists of 10 major incident domains, that include incident type, patient outcomes, patient characteristics, incident characteristics, contributing factors and hazards, organizational outcomes, detection, mitigating factors, ameliorating actions, and actions taken to reduce risk (Figure 1).11 The framework is applicable to all hospital safety incidents, but we limited I‐Tracker to SEs because our hospitals had completed comprehensive reviews and action plans only for these more serious events. The literature on the ICPS framework812 was carefully reviewed to identify the specific data fields that were recommended by ICPS developers to be included under each of the 10 major classification domains. In most instances, data fields existed only in the body of these reports. Article texts, however, provided sufficient descriptions of these data fields to allow their translation into data entry fields in I‐Tracker with accompanying help windows and explanations to guide I‐Tracker users. Sixty ICPS data fields were programmed into I‐Tracker, with another 120 fields that allowed entry of descriptions and explanations of the ICPS data field entries. For instance, an entry of Yes into an ICPS data field that queried Was there a systems problem of an external organization other than a Providence entity opens a Describe field that allows a brief description of the problem, and an additional Details field that allows a longer explanation of the problem if necessary. The brief Describe field contents populate an automatically generated fishbone diagram.

The authors and quality staff translated the most recent 15 SE reviews into ICPS terms and classifications, and entered the results into I‐Tracker as it was being developed, to assist system design and programming of the system. The authors noted during data entry which of the 10 ICPS major domains had not been analyzed by the previous 15 reviews. Because existing reports were unstructured with considerable variation in style and usage of terms, the authors and quality staff made group decisions regarding how to cross‐walk existing information into the standardized ICPS data fields.

RESULTS

In developing I‐Tracker, the authors and quality staff observed that the ICPS framework and recommended data fields were logical and straightforward to learn. Although it was difficult to find the definitions of specific ICPS data fields within the 10 major domains in the text of retrieved articles, these fields could be readily cross‐walked into I‐Tracker data entry fields. Translating existing SE reports into I‐Tracker classifications, however, presented considerable challenges because of the unstructured, discursive, and variable nature of our SE review and reports. The authors and staff spent 1 to 2 hours conferring over each report to make judgments as to which elements of the review would be entered into which I‐Tracker data fields. Once the authors and staff translated existing reports into ICPS terms, actual data entry into I‐Tracker took typically less than 30 minutes for each review. We found that none of our 15 SE reviews included information on the following ICPS major domains: detection, mitigating factors, and ameliorating actions. We also observed that many ICPS data fields were not assessed, such as patient contributions to errors and external organization's contributions to a safety incident.

The latest version of I‐Tracker receives and displays information at the individual patient level. Records are shown onscreen with different screen layouts depending on the viewer's login security clearance. Hospital safety staff have full access to view and enter data on the initial layout, which displays patient demographic information and folder tabs that navigate when clicked to other database fields (Figure 2). Viewers with lower security clearance either view the same opening screen, but have limited access to other screens, or view a different opening screen designed to meet their specific needs. All screens provide definitions of terms and information to assist data entry, buttons that navigate to help pages, pop‐up windows that provide tips, and buttons that trigger brief audio explanations. Most fields use drop‐down lists to standardize data entry around the ICPS definitions, with default values entered into many fields to streamline data entry. A list view allows review of all patients and quick access to an individual patient's record. All fields and combinations of fields with Boolean rules are searchable within the database.

I‐Tracker has features that support SE review groups in beginning an SE review by providing them a paper form or electronic interface by way of a portable computer or tablet device, that guides their discussions and analyses toward providing conclusions that can be entered into the database fields, thereby aligning their deliberations with the ICPS conceptual framework. The same resource is available within the database online for those groups who would prefer to use computer prompts and enter data directly into the database as they proceed through their analyses. Some layouts contain windows that port live views from external Web sites (eg, JC RCA resources) that provide participants of RCA groups with tools to assist their work. FMP11 allows users to access the database by portable computers or handheld tablet devices using the hospitals' WiFi network.

A report screen allows automatic generation of different printouts of individual or aggregate summary reports. A Comprehensive Report includes all of the data fields included in the ICPS conceptual framework. Other reports present subsets of data depending on the user's needs and access privileges. The FMPS11 database allows printing the reports to paper or Portable Document Format (pdf), exporting data into an Excel spreadsheet, or e‐mailing reports to recipients from within I‐Tracker.

Additionally, I‐Tracker functionality facilitates follow‐up and monitoring of action items developed during the RCA process in a manner that conforms to the ICPS framework. We are now developing educational resources for RCA team members to investigate the implementation of I‐Tracker into future RCAs.

DISCUSSION

I‐Tracker provides an intranet‐based tool that met the objectives of the present project. The process of entering 15 existing SE reviews and action plans from our healthcare system into I‐Tracker allowed an incremental development of the database and identified gaps in our existing RCA process. For instance, none of the previous RCAs critically appraised detection, mitigating factors, or ameliorating actions; defined the specific nature or quantified severity of patient injuries using standardized terms; distinguished between human errors and negligence; or comprehensively reported the full spectrum of underlying causes of Tracker's use of standardized terms based on the ICPS conceptual framework provided a potential resource for focusing SE reviews and producing more comprehensive RCAs and action plans in the future. I‐Tracker has additional potential to facilitate dissemination of RCAs to other facilities, both as individual incident reports and aggregated summaries as recommended by experts in patient safety.13

The deficiencies in our existing RCA analyses, identified during data entry into I‐Tracker, represent common shortcomings experienced by other healthcare organizations and summarized in a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.4 Considerable hindsight bias and prevailing concerns of the day taint the RCA process, which is time‐consuming and labor intensive, and thereby hinders comprehensive reviews. Also, our SE reviews, like others reviewed in the literature,14 focused on biologic injury to patients and omitted assessment of psychologic, organizational, social, and economic injury domains. Although SE review teams benefit from involvement of quality improvement staff who are trained in techniques and goals of RCA,15 many hospitals like ours have limited resources for fully staffing all SE reviews with trained facilitators. These SE reviews generate both quantitative and qualitative data, the latter of which hinders standardized data entry in the absence of a conceptual framework. A structured database with formative tools to guide RCAs in conformance with the ICPS framework in organizations without sufficient numbers of trained facilitators offers opportunities to produce more comprehensive, standardized, and actionable reports. To date, our quality staff and leadership have responded positively to presentations of the functional features of I‐Tracker (Table 1).

|

| Online availability of the system that allows access both from client database software loaded on Quality Office computers and through intranet browser software (Explorer, Safari, Firefox, etc) |

| Security features of encrypted software that allow full or limited views depending on the user's password security clearance and purpose for reviewing data |

| Software accessibility in authoring and managing the database, which do not require support from information technology data analysts |

| Decision support tools provided in the system to assist RCA analysis |

| System flexibility that allows scripted reporting of single SEs or multiple SE summaries within any selected timeframe |

Limitations of our report include its focus solely on the development and programming phase of I‐Tracker and the absence of information on its actual implementation. We believe, however, the development phase is important to report because it demonstrates that the ICPS framework and specific ICPS data fields are amenable to incorporation into a decision support and reporting tool, which to our knowledge has not been previously reported. We begin implementation of I‐Tracker within our organization this year and will have observations on its feasibility, acceptability, and staff training needs. As an additional limitation, we emphasize that we do not propose I‐Tracker as a solution for other organizations, because we have no plans for its commercial or public domain development. This report is intended to demonstrate, however, that commercially available software, such as FileMaker, can readily support the ICPS Framework and thereby has potential to assist RCAs and SE reporting. Other organizations may develop similar systems on other database platforms that incorporate the ICPS system into their reviews.

To implement I‐Tracker, we are now working with nursing and pharmacy leadership focus groups to develop formative tools, data collection forms, and other resources to assist their RCA efforts and data entry into the database. We also plan to apply the database tool to our residency training program to promote resident involvement in SE reviews by providing standardized, reproducible, and structured processes.16 Our 5‐state healthcare system has funded an evaluation of the implementation phase of I‐Tracker to other Providence facilities. Because the ICPS framework applies to all safety incidents beyond SEs (Table 2), a successful implementation of I‐Tracker for SEs will allow its eventual application to other types of critical incidents.

|

| Clinical administration |

| Clinical process/procedure |

| Documentation |

| Healthcare‐associated infection |

| Medication/IV fluids |

| Blood/blood products |

| Nutrition |

| Oxygen/gas/vapor |

| Medical device/equipment |

| Behavior |

| Patient accidents |

| Infrastructure/building/fixtures |

| Resources/organizational management |

The strength of this project derives from its innovative development of an intranet‐based tool that allows groups to conform their RCAs to the ICPS framework. Because the absence of a standardized classification for patient safety concepts has hindered advances in patient safety,11 we believe I‐Tracker, or decision support tools like it that use the ICPS framework, can standardize RCAs and promote dissemination and adoption of action plans.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of Judy Stenstrom, Lynette Savage, and the Portland Service Area Quality Improvement Office.

Recognition that healthcare carries considerable risks of patient injury has focused efforts on identifying problems before they occur, and understanding the root causes of those problems that do occur to prevent them from happening again.1 To further these efforts, a Joint Commission (JC) standard requires hospitals to review sentinel events (SE).2 Reviews must develop a timely, thorough, and credible root cause analysis (RCA), implement action plans to reduce risk, and monitor the effectiveness of implemented improvements.3

Ideally, hospitals would summarize their experiences with SE reviews, identify high‐risk activities and patients, institute system changes to prevent SE recurrences, and share their findings with other healthcare organizations to help them avoid similar patient injuries.1 In support of this last goal, the JC maintains a voluntary database system that allows hospitals to report their SE analyses for other facilities to review and institute preventative actions.

Unfortunately, the reality of SE reviews does not match their ideals for improving patient safety.4 Healthcare organizations often describe their review process as less than credible and note a need for ongoing oversight to maintain the reviews' effectiveness.5 The JC voluntary reporting system captures less than 1% of the SEs that occur nationally,2 because hospitals perceive barriers to external reporting.1 If healthcare organizations decide against reporting externally, they can create their own internal systems to aggregate and summarize SEs, but few such systems exist. A major impediment to designing internal systems is the absence of universally endorsed nomenclature for safety‐related events.6, 7 Poorly aligned terminology and subjective conceptualizations for safety incidents impede the aggregation of SEs, comparisons between facilities, and trend analyses for tracking SE patterns.

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) World Alliance for Patient Safety, in collaboration with the JC, began developing an International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) to provide healthcare organizations a consistent conceptual model for safety incidents and promote their classification by a standardized taxonomy.810 Although this system has promise for allowing standardization, data aggregation, analysis, and learning between institutions,11 integration of the ICPS conceptual model into an SE decision support tool with summarizing and reporting features has not been reported.

This report describes our development of an intranet‐based SE reporting system, called Incident Tracker (I‐Tracker), based on the ICPS model. For our SE review groups from the 4 Providence Health Systems (PHS) Portland Service Area (PSA) hospitals, the I‐Tracker system offers a tool to guide efforts in developing RCAs and action plans in alignment with the ICPS framework. The system includes scripts that automatically generate and distribute standardized reports of individual and aggregated SEs. The objectives of this project were to report our experience with developing a flexible and accessible intranet‐based system that assists RCA participants in conforming to the ICPS framework and oversight safety staff in summarizing and reporting root cause analyses.

METHODS

The 4 PSA hospitals have 1083 licensed beds and perform SE reviews with a centralized process that reports results to a Community Governing Board. An ad hoc team for each SE performs the RCAs. The SE groups report RCAs and action plans in an unstructured format that varies for each event. A paper file is maintained for each SE report, but a system for aggregating reports to track trends, disseminating SE trends, or monitoring the completion or effectiveness of action plans is not available.

We designed a system to achieve the following objectives:

-

Apply the ICPS framework (Figure 1) and taxonomy of terms to SE analyses;

-

Provide a computer‐based tool to assist review groups and quality staff to perform their SE reviews and data collection in alignment with the ICPS framework;

-

Create an intranet‐based database that captures elements of the reviews, RCAs, and action plans with the use of drop‐down lists, help windows, windows with live access to Internet educational resources and tools, decision support tools, default entries, and audio prompts to streamline data entry;

-

Generate a suite of standardized reports customized for different audiences that can be accessed online and printed from the database with automated scripts;

-

Produce intranet‐based summaries of aggregated events to identify common causes and disseminate observed patterns and action plans to other PSA hospitals.

We selected FileMaker Pro 11 Advanced (FMP11) for authoring and maintaining the decision support tool and database, and FileMaker Pro Server 11 Advanced (FMPS11) (Filemaker, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) for hosting the system, because it provides intranet access and tools for updating the system by personnel with minimal programming experience. End users can view and enter data through layouts that display only the information allowed by the user's login password and access privileges, with external authentication by Active Directory and Open Directory technology. Staff who author and manage the database do so through client FMP11 software loaded on a computer that provides remote server access.

The I‐Tracker system was authored using the ICPS definitions for the 48 preferred terms for safety incidents and the ICPS conceptual framework.8 The conceptual framework consists of 10 major incident domains, that include incident type, patient outcomes, patient characteristics, incident characteristics, contributing factors and hazards, organizational outcomes, detection, mitigating factors, ameliorating actions, and actions taken to reduce risk (Figure 1).11 The framework is applicable to all hospital safety incidents, but we limited I‐Tracker to SEs because our hospitals had completed comprehensive reviews and action plans only for these more serious events. The literature on the ICPS framework812 was carefully reviewed to identify the specific data fields that were recommended by ICPS developers to be included under each of the 10 major classification domains. In most instances, data fields existed only in the body of these reports. Article texts, however, provided sufficient descriptions of these data fields to allow their translation into data entry fields in I‐Tracker with accompanying help windows and explanations to guide I‐Tracker users. Sixty ICPS data fields were programmed into I‐Tracker, with another 120 fields that allowed entry of descriptions and explanations of the ICPS data field entries. For instance, an entry of Yes into an ICPS data field that queried Was there a systems problem of an external organization other than a Providence entity opens a Describe field that allows a brief description of the problem, and an additional Details field that allows a longer explanation of the problem if necessary. The brief Describe field contents populate an automatically generated fishbone diagram.

The authors and quality staff translated the most recent 15 SE reviews into ICPS terms and classifications, and entered the results into I‐Tracker as it was being developed, to assist system design and programming of the system. The authors noted during data entry which of the 10 ICPS major domains had not been analyzed by the previous 15 reviews. Because existing reports were unstructured with considerable variation in style and usage of terms, the authors and quality staff made group decisions regarding how to cross‐walk existing information into the standardized ICPS data fields.

RESULTS

In developing I‐Tracker, the authors and quality staff observed that the ICPS framework and recommended data fields were logical and straightforward to learn. Although it was difficult to find the definitions of specific ICPS data fields within the 10 major domains in the text of retrieved articles, these fields could be readily cross‐walked into I‐Tracker data entry fields. Translating existing SE reports into I‐Tracker classifications, however, presented considerable challenges because of the unstructured, discursive, and variable nature of our SE review and reports. The authors and staff spent 1 to 2 hours conferring over each report to make judgments as to which elements of the review would be entered into which I‐Tracker data fields. Once the authors and staff translated existing reports into ICPS terms, actual data entry into I‐Tracker took typically less than 30 minutes for each review. We found that none of our 15 SE reviews included information on the following ICPS major domains: detection, mitigating factors, and ameliorating actions. We also observed that many ICPS data fields were not assessed, such as patient contributions to errors and external organization's contributions to a safety incident.

The latest version of I‐Tracker receives and displays information at the individual patient level. Records are shown onscreen with different screen layouts depending on the viewer's login security clearance. Hospital safety staff have full access to view and enter data on the initial layout, which displays patient demographic information and folder tabs that navigate when clicked to other database fields (Figure 2). Viewers with lower security clearance either view the same opening screen, but have limited access to other screens, or view a different opening screen designed to meet their specific needs. All screens provide definitions of terms and information to assist data entry, buttons that navigate to help pages, pop‐up windows that provide tips, and buttons that trigger brief audio explanations. Most fields use drop‐down lists to standardize data entry around the ICPS definitions, with default values entered into many fields to streamline data entry. A list view allows review of all patients and quick access to an individual patient's record. All fields and combinations of fields with Boolean rules are searchable within the database.

I‐Tracker has features that support SE review groups in beginning an SE review by providing them a paper form or electronic interface by way of a portable computer or tablet device, that guides their discussions and analyses toward providing conclusions that can be entered into the database fields, thereby aligning their deliberations with the ICPS conceptual framework. The same resource is available within the database online for those groups who would prefer to use computer prompts and enter data directly into the database as they proceed through their analyses. Some layouts contain windows that port live views from external Web sites (eg, JC RCA resources) that provide participants of RCA groups with tools to assist their work. FMP11 allows users to access the database by portable computers or handheld tablet devices using the hospitals' WiFi network.

A report screen allows automatic generation of different printouts of individual or aggregate summary reports. A Comprehensive Report includes all of the data fields included in the ICPS conceptual framework. Other reports present subsets of data depending on the user's needs and access privileges. The FMPS11 database allows printing the reports to paper or Portable Document Format (pdf), exporting data into an Excel spreadsheet, or e‐mailing reports to recipients from within I‐Tracker.

Additionally, I‐Tracker functionality facilitates follow‐up and monitoring of action items developed during the RCA process in a manner that conforms to the ICPS framework. We are now developing educational resources for RCA team members to investigate the implementation of I‐Tracker into future RCAs.

DISCUSSION

I‐Tracker provides an intranet‐based tool that met the objectives of the present project. The process of entering 15 existing SE reviews and action plans from our healthcare system into I‐Tracker allowed an incremental development of the database and identified gaps in our existing RCA process. For instance, none of the previous RCAs critically appraised detection, mitigating factors, or ameliorating actions; defined the specific nature or quantified severity of patient injuries using standardized terms; distinguished between human errors and negligence; or comprehensively reported the full spectrum of underlying causes of Tracker's use of standardized terms based on the ICPS conceptual framework provided a potential resource for focusing SE reviews and producing more comprehensive RCAs and action plans in the future. I‐Tracker has additional potential to facilitate dissemination of RCAs to other facilities, both as individual incident reports and aggregated summaries as recommended by experts in patient safety.13

The deficiencies in our existing RCA analyses, identified during data entry into I‐Tracker, represent common shortcomings experienced by other healthcare organizations and summarized in a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.4 Considerable hindsight bias and prevailing concerns of the day taint the RCA process, which is time‐consuming and labor intensive, and thereby hinders comprehensive reviews. Also, our SE reviews, like others reviewed in the literature,14 focused on biologic injury to patients and omitted assessment of psychologic, organizational, social, and economic injury domains. Although SE review teams benefit from involvement of quality improvement staff who are trained in techniques and goals of RCA,15 many hospitals like ours have limited resources for fully staffing all SE reviews with trained facilitators. These SE reviews generate both quantitative and qualitative data, the latter of which hinders standardized data entry in the absence of a conceptual framework. A structured database with formative tools to guide RCAs in conformance with the ICPS framework in organizations without sufficient numbers of trained facilitators offers opportunities to produce more comprehensive, standardized, and actionable reports. To date, our quality staff and leadership have responded positively to presentations of the functional features of I‐Tracker (Table 1).

|

| Online availability of the system that allows access both from client database software loaded on Quality Office computers and through intranet browser software (Explorer, Safari, Firefox, etc) |

| Security features of encrypted software that allow full or limited views depending on the user's password security clearance and purpose for reviewing data |

| Software accessibility in authoring and managing the database, which do not require support from information technology data analysts |

| Decision support tools provided in the system to assist RCA analysis |

| System flexibility that allows scripted reporting of single SEs or multiple SE summaries within any selected timeframe |

Limitations of our report include its focus solely on the development and programming phase of I‐Tracker and the absence of information on its actual implementation. We believe, however, the development phase is important to report because it demonstrates that the ICPS framework and specific ICPS data fields are amenable to incorporation into a decision support and reporting tool, which to our knowledge has not been previously reported. We begin implementation of I‐Tracker within our organization this year and will have observations on its feasibility, acceptability, and staff training needs. As an additional limitation, we emphasize that we do not propose I‐Tracker as a solution for other organizations, because we have no plans for its commercial or public domain development. This report is intended to demonstrate, however, that commercially available software, such as FileMaker, can readily support the ICPS Framework and thereby has potential to assist RCAs and SE reporting. Other organizations may develop similar systems on other database platforms that incorporate the ICPS system into their reviews.

To implement I‐Tracker, we are now working with nursing and pharmacy leadership focus groups to develop formative tools, data collection forms, and other resources to assist their RCA efforts and data entry into the database. We also plan to apply the database tool to our residency training program to promote resident involvement in SE reviews by providing standardized, reproducible, and structured processes.16 Our 5‐state healthcare system has funded an evaluation of the implementation phase of I‐Tracker to other Providence facilities. Because the ICPS framework applies to all safety incidents beyond SEs (Table 2), a successful implementation of I‐Tracker for SEs will allow its eventual application to other types of critical incidents.

|

| Clinical administration |

| Clinical process/procedure |

| Documentation |

| Healthcare‐associated infection |

| Medication/IV fluids |

| Blood/blood products |

| Nutrition |

| Oxygen/gas/vapor |

| Medical device/equipment |

| Behavior |

| Patient accidents |

| Infrastructure/building/fixtures |

| Resources/organizational management |

The strength of this project derives from its innovative development of an intranet‐based tool that allows groups to conform their RCAs to the ICPS framework. Because the absence of a standardized classification for patient safety concepts has hindered advances in patient safety,11 we believe I‐Tracker, or decision support tools like it that use the ICPS framework, can standardize RCAs and promote dissemination and adoption of action plans.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of Judy Stenstrom, Lynette Savage, and the Portland Service Area Quality Improvement Office.

- .Reporting of adverse events.N Engl J Med.2002;347:1633–1638.

- The Joint Commission's Sentinel Event Policy: ten years of improving the quality and safety of health care.Jt Comm Perspect.2005;25(1):3–5.

- ,.Root cause analysis and nursing management responsibilities in wrong‐site surgery.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2006;25,221–225.

- ,.Root Cause Analysis.Making Health Care Safer. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/chap5.htm. Accessed May 21,2010.

- Oversight group holds RCA teams accountable.Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv.2008;15:117–118.

- .Shared meanings: preferred terms and definitions for safety and quality concepts.Med J Aust.2006;184:S41–S43.

- ,,.What do family physicians consider an error? A comparison of definitions and physician perception.BMC Fam Pract.2006;7:73.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:18–26.

- ,,,,.The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standardized terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events.Int J Qual Health Care.2005;17:95–105.

- World Health Organization. 2009 Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. Final Technical Report Version 1.1. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf. Accessed April 25,2011.

- ,,, et al.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:2–8.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: a Delphi survey.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:9–17.

- ,,.Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine.JAMA.2008;299:685–687.

- ,,,,.How can clinicians measure safety and quality in acute care?Lancet.2004;363:1061–1067.

- ,,,,.Systematic root cause analysis of adverse drug events in a tertiary referral hospital.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.2000;26:563–575.

- ,,,,,.Educational quality improvement report: outcomes from a revised morbidity and mortality format that emphasised patient safety.Postgrad Med J.2008;84:211–216.

- .Reporting of adverse events.N Engl J Med.2002;347:1633–1638.

- The Joint Commission's Sentinel Event Policy: ten years of improving the quality and safety of health care.Jt Comm Perspect.2005;25(1):3–5.

- ,.Root cause analysis and nursing management responsibilities in wrong‐site surgery.Dimens Crit Care Nurs.2006;25,221–225.

- ,.Root Cause Analysis.Making Health Care Safer. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/chap5.htm. Accessed May 21,2010.

- Oversight group holds RCA teams accountable.Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv.2008;15:117–118.

- .Shared meanings: preferred terms and definitions for safety and quality concepts.Med J Aust.2006;184:S41–S43.

- ,,.What do family physicians consider an error? A comparison of definitions and physician perception.BMC Fam Pract.2006;7:73.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:18–26.

- ,,,,.The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standardized terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events.Int J Qual Health Care.2005;17:95–105.

- World Health Organization. 2009 Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. Final Technical Report Version 1.1. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf. Accessed April 25,2011.

- ,,, et al.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:2–8.

- ,,,,,.Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: a Delphi survey.Int J Qual Health Care.2009;21:9–17.

- ,,.Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine.JAMA.2008;299:685–687.

- ,,,,.How can clinicians measure safety and quality in acute care?Lancet.2004;363:1061–1067.

- ,,,,.Systematic root cause analysis of adverse drug events in a tertiary referral hospital.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.2000;26:563–575.

- ,,,,,.Educational quality improvement report: outcomes from a revised morbidity and mortality format that emphasised patient safety.Postgrad Med J.2008;84:211–216.

Implementing an RRT

In‐hospital cardiopulmonary arrests are often preceded by signs of clinical instability, such as changes in vital signs or mental status.1 Nearly 85% of patients who suffer from cardiopulmonary arrests have documented observations of deterioration in the 8 hours before arrest.2 A Medical Emergency Team (MET), sometimes known as Rapid Response Team (RRT), can rapidly assess and manage unstable patients, with the goal that early intervention will prevent adverse outcomes. In 2004, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), as part of its 100,000 Lives Campaign, called for hospitals to implement rapid response systems as 1 of 6 strategies to reduce deaths in hospital.3 Since this recommendation, hundreds of hospitals in the United States have invested substantial financial and personnel resources to implement some form of a rapid response system, which is comprised of a varying array of healthcare providers who bring critical care expertise to the patient's bedside.4, 5

Despite the intuitive appeal of the approach, and early observational data which suggested that METs could reduce both codes and unexpected in‐hospital mortality,2, 6 the largest randomized controlled trial found that METs failed to reduce unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, cardiac arrests, or unexpected deaths.7 More recently, in a prospective observational cohort study at 1 US hospital, Chan et al. found that a nurse‐led RRT did not impact hospital‐wide code rates or mortality.4

The study of rapid response systems is further complicated by a lack of standard definition, and the many types of hospitals in which they may be implemented. In 2006, a consensus conference suggested that MET be used to refer to teams led by physicians (usually intensivists), and RRT be used for teams led by nurses.8 Many studies have been conducted at non‐US institutions, and follow‐up periods have generally been 1 year or less. We report on almost 4 years of experience with a hospitalist‐led MET implemented in a major US academic medical center, and examine the subsequent changes in code calls, cardiac arrests, deaths following cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and overall hospital mortality. Because the MET did not operate in the critical care units, and because cardiac arrest may occur without prior signs of deterioration, we hypothesized that implementation of the MET would correspond to a small drop in total code calls, no change in codes called inside of critical care units, no change in cardiac arrest outside of critical care, and a marked drop in other medical crises (mostly respiratory distress) outside critical care. We also hypothesized that there would be no change in the rate of fatal codes, because most deaths occur in patients who were found to be pulseless on arrival of the code team.

METHODS

Setting

Beginning in March 2006, Baystate Medical Center implemented an MET in accordance with the recommendations of the IHI. Baystate is a 670‐bed tertiary care referral center in Springfield, Massachusetts, and a major teaching hospital for Tufts University. Throughout the study period, the hospital had full‐time intensivists and >90% of medical patients were cared for by hospitalists with 24‐hour coverage. As a result, a medical patient's attending physician or corresponding coverage was usually on site. In order to promote acceptance of the team as well as to maximize continuity of care, we constructed our MET to include a critical care nurse, a respiratory therapist, intravenous therapist, and the patient's physician (either attending or resident). Baystate staff members carry alpha‐numeric pagers, so attendings could be alerted to the fact that the MET had been activated by means of a text page. In the event that the patient's physician could not respond, an ICU physician served as a backup team member. The MET was implemented initially in March of 2006 on 2 medical floors, and over a period of 3 months was gradually expanded to cover the entire hospital. For surgical patients, the MET was led by the attending surgeon or appropriate resident. Educational efforts, including meetings, e‐mails, and posters, targeted nurses in particular, but anyone could summon the MET by calling the activation number posted on all ward telephones. Nurses were encouraged to activate the system for any of the following: heart rate (<40 and >130 beats per minute), systolic blood pressure (<90 mmHg), respiratory rate (<8 or >24 per minute), oxygen saturation (<90% despite supplemental oxygen), altered mental status, or simply concern that something is wrong. The MET implementation oversight committee met biweekly and made adjustments to the team composition and protocols using rapid Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles. A full description of the implementation process has been published elsewhere.9

In addition to the MET, Baystate has a separate code team which can be activated for cardiovascular arrests via a call to a designated phone extension, which activates a page to the code team members and an overhead announcement. Code team members include the ICU medical resident and intern, a critical care nurse, an anesthesiologist, a respiratory therapist, a staff nurse, and the house supervisor. In response to the overhead announcement, doctors, nurses and students in the vicinity often respond as well. Prior to implementation of the MET, a code blue was the only level of immediate response available.

Data and Outcomes

The nurse attending a code blue or code completes a report form which becomes part of the permanent medical record. A copy of the report is reviewed by the Division of Healthcare Quality and housed in the Critical Care administrative offices. For this study, we reviewed all code reports from January 2004 through December 2009. For each report, we extracted the following information: the date, location (inside or outside of a critical care unit), whether the patient had a pulse on arrival of the team, and whether the patient survived to discharge. All activations of the code system were included, regardless of the patient's code status (ie, even if the code was called in error) or the reason for the code call. Patients were then aggregated to calculate the rate of codes called per calendar quarter, as well as the rates of codes called in and out of critical care and the rates of two subsets of code calls, namely cardiac arrests and other medical crises (eg, respiratory arrest or seizures).

MET members were also required to collect data on the reason for the MET call, as well as the response time, time of day and unit, duration of the call, whether the physician was present, whether the patient was transferred to critical care, and whether the patient survived to discharge. In addition, we surveyed the nursing staff directly after the call, asking the following questions: 1) Did the team arrive promptly? 2) Were the critical care nurse and respiratory therapist efficient and respectful? 3) Did you feel the patient's needs were addressed appropriately? 4) Did you feel supported by the MET? and 5) Would you call the MET again?

Statistical Analysis

Quarterly event rates per 1000 admissions were calculated for each outcome. Event rates were compared using piecewise Poisson regression10 with robust standard errors.11 We excluded the 2 quarterly periods (2006 Q1 and Q2) during which the MET was implemented. A piecewise Poisson regression model was chosen to facilitate estimation of: 1) change in code calls from immediately before implementation to immediately after; and 2) temporal trends in code calls before and after implementation. Each model was built with 1 pre‐implementation intercept (December 2005), and 1 post‐implementation intercept (July 2006), as well as 2 slopes, with time coded negatively before the intervention (ie, 2, 1, 0), and positively after (ie, 0, 1, 2). Linear contrasts tested for differences in each parameter. A significant difference in intercepts suggests a post‐intervention decrease in code call rates; a significant, negative post‐intervention slope suggests continuing decline in code call rates. Statistical inferences were aided with visual plots of predicted incidence rates for each quarter in the observation period, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each quarterly rate estimated by the delta method.12 Alpha was specified at 0.05 and all significance tests were 2‐sided. Analyses were conducted in Stata 11.1 for Windows ( 2010, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Implementation of the MET

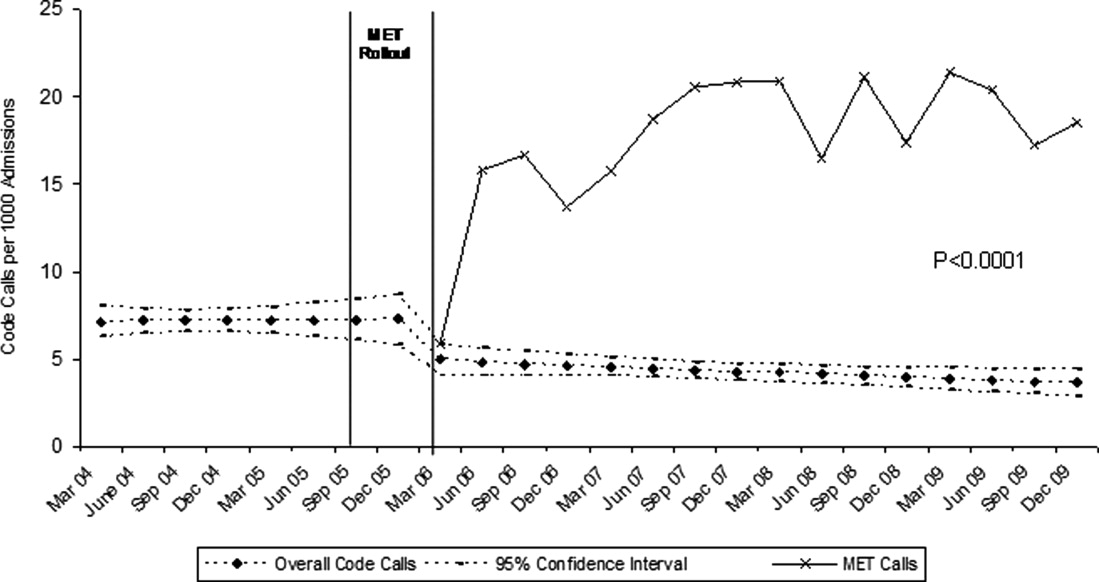

The MET was introduced in the first and second quarters of 2006, with 2717 calls logged through the end of 2009 (out of 154,382 admissions). The rate of MET calls increased during the first 6 months of implementation from 5.95 per 1000 admissions in the first quarter of the intervention, to 15.8 calls per 1000 admissions in the second quarter. Call rates peaked in the first half of 2009, at 20.9 calls per 1000 admissions, leveling off to 17.9 calls per 1000 admissions in the last half of 2009 (Figure 1). Of calls with time recorded, 40% occurred on the day shift, 35% on the evening shift, and 25% on the night shift. The most common reason to call the MET was respiratory distress (33%), followed by cardiovascular instability (25%), and neurological abnormality (20%). In 15% of cases, concern about a patient's condition prompted the nurse to call. Calls came primarily from medical floors (75%) and surgical units (20%). The median response time was 4 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 2.8 to 5.2 minutes) with no meaningful trend during the study period. The median call duration was 50 minutes (IQR, 38 to 72 minutes). Again, there was no trend over time. The most common interventions were arterial blood gas, fluid resuscitation, and electrocardiogram (see Supporting Web Appendix Table 1 in the online version of this article). A physician was present at 52% of the calls in the first year, which rose to 93% of calls in the final year. Approximately 25% of calls resulted in the patient being transferred to a critical care unit. Staff evaluations were overwhelmingly positive. Nurses rated the teams on the following points: whether the critical care nurse and respiratory therapist were efficient and respectful (mean rating 98%, SD 5.6%); promptness (98%, SD 5.6%); whether the patient's needs were addressed appropriately (mean 98%, SD 4.2%); whether the nurse felt supported by the MET (99.5%, SD 1.7%); and whether they would call the MET again (99.7%, SD 1.4%).

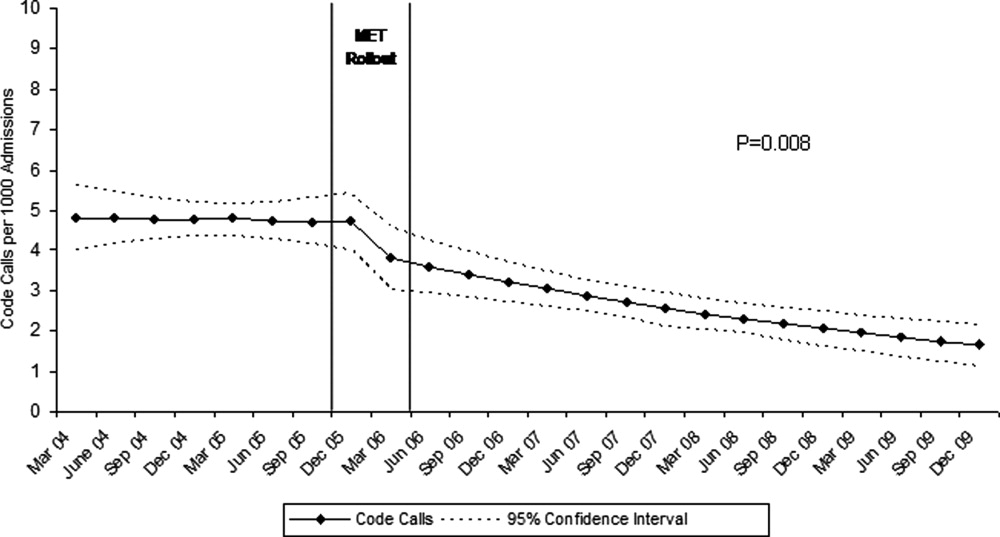

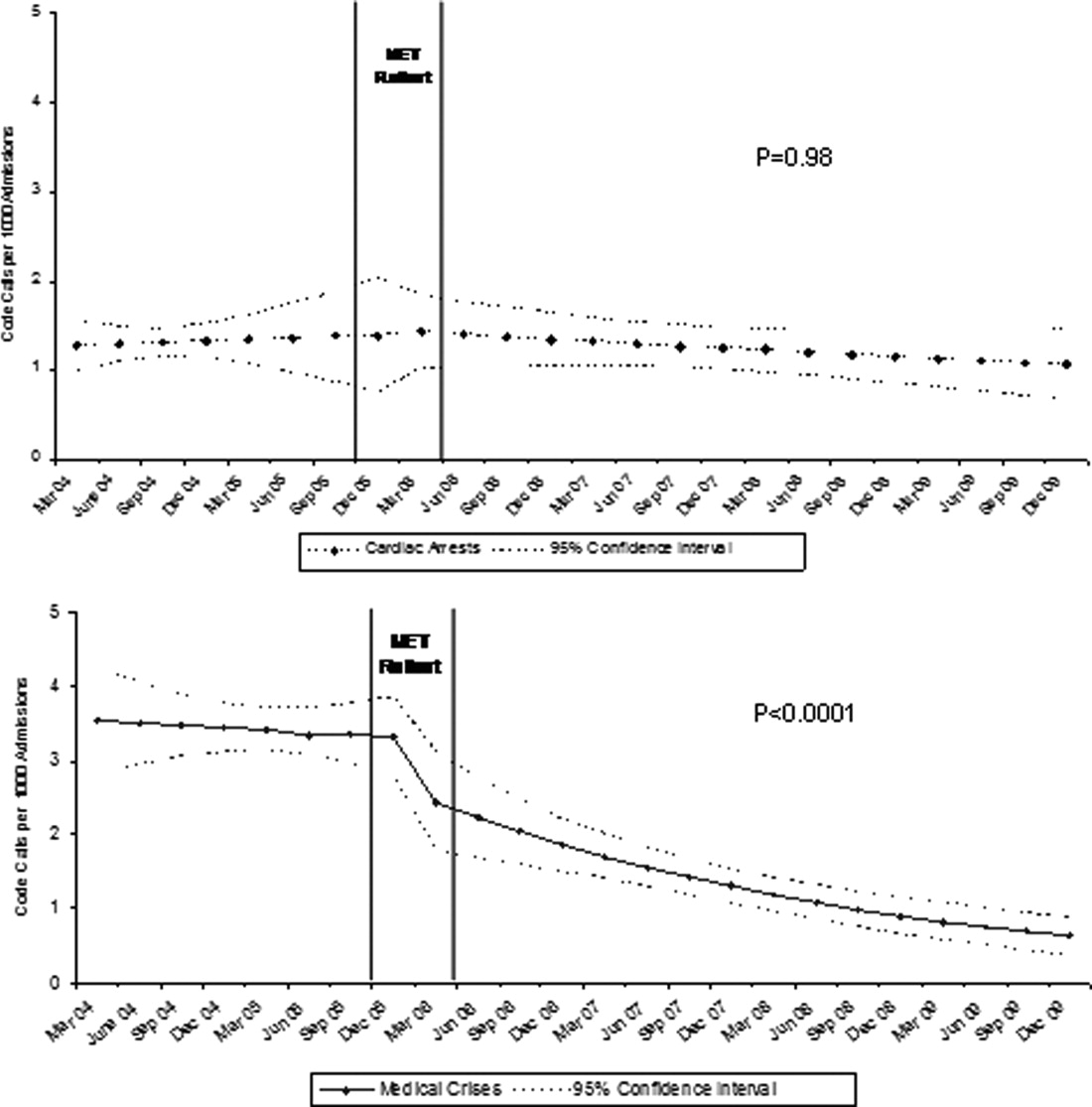

Effect of MET on Code Calls and Mortality

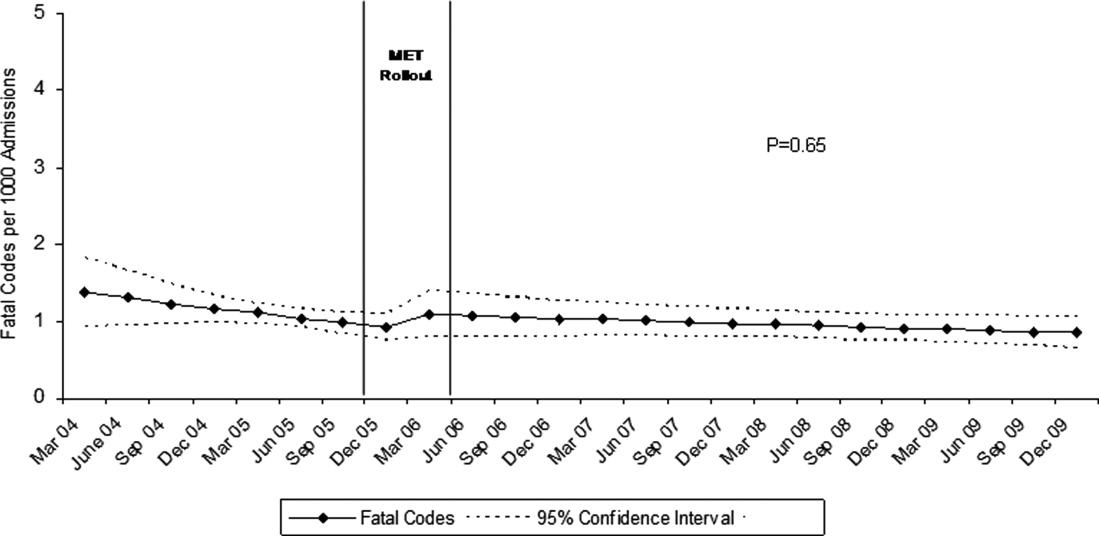

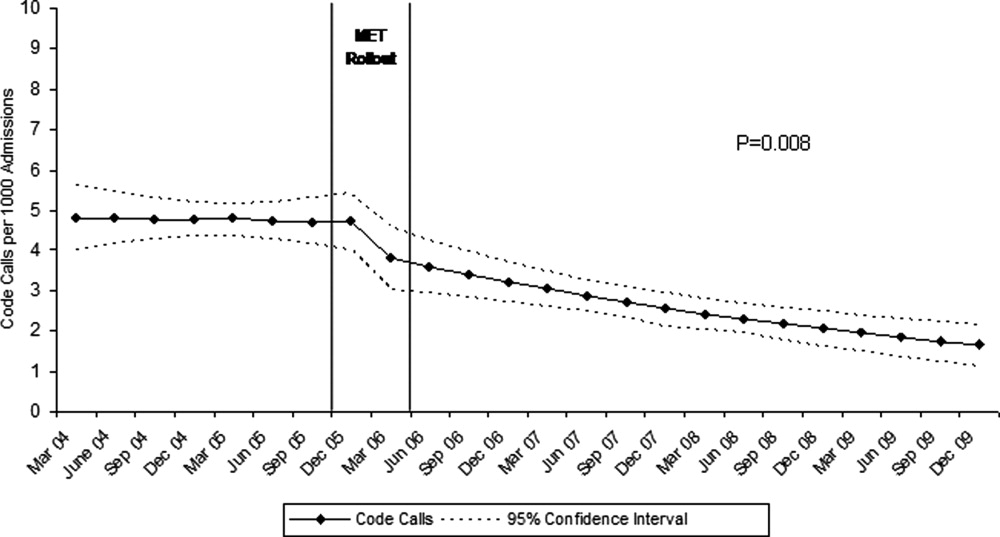

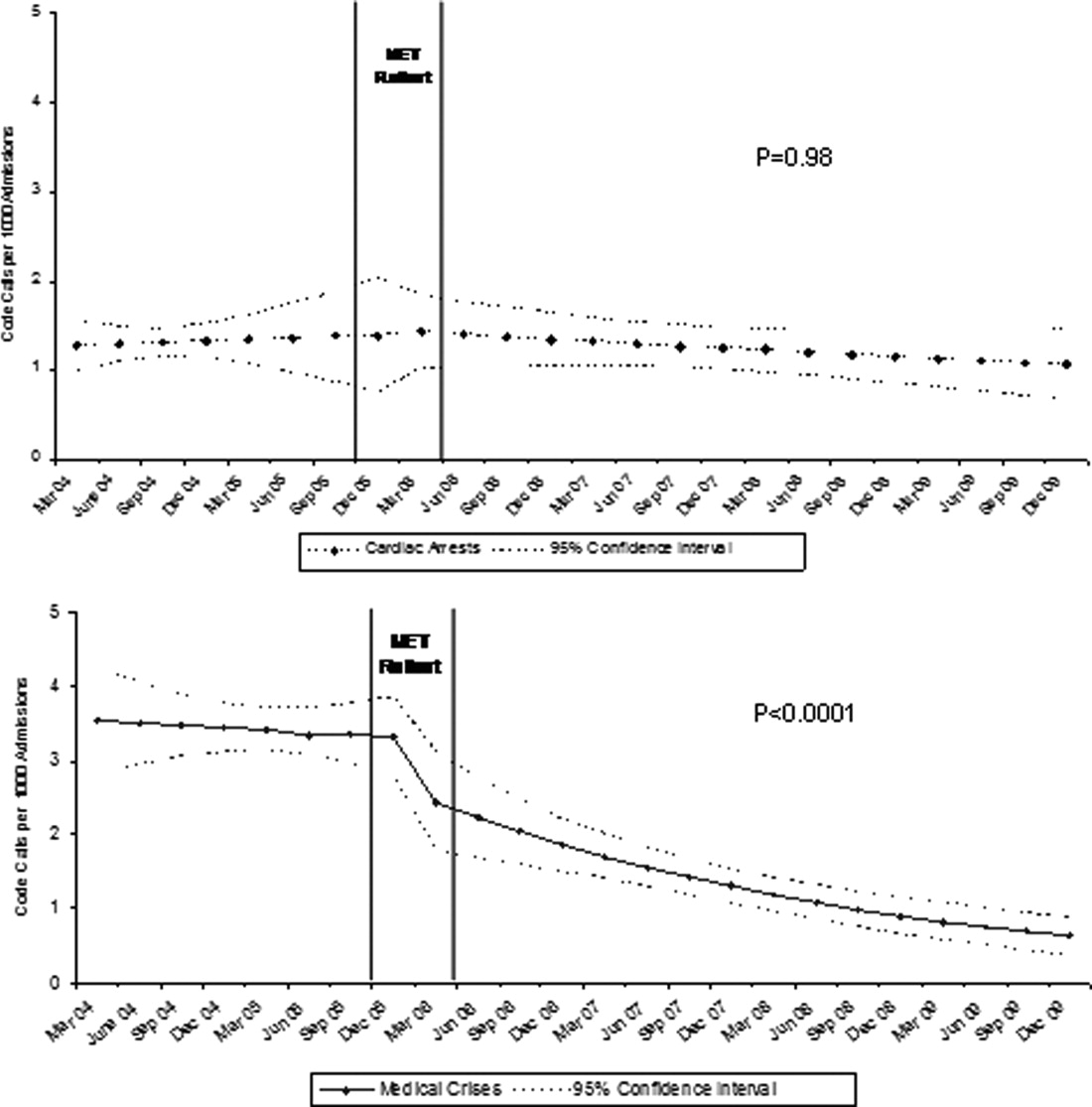

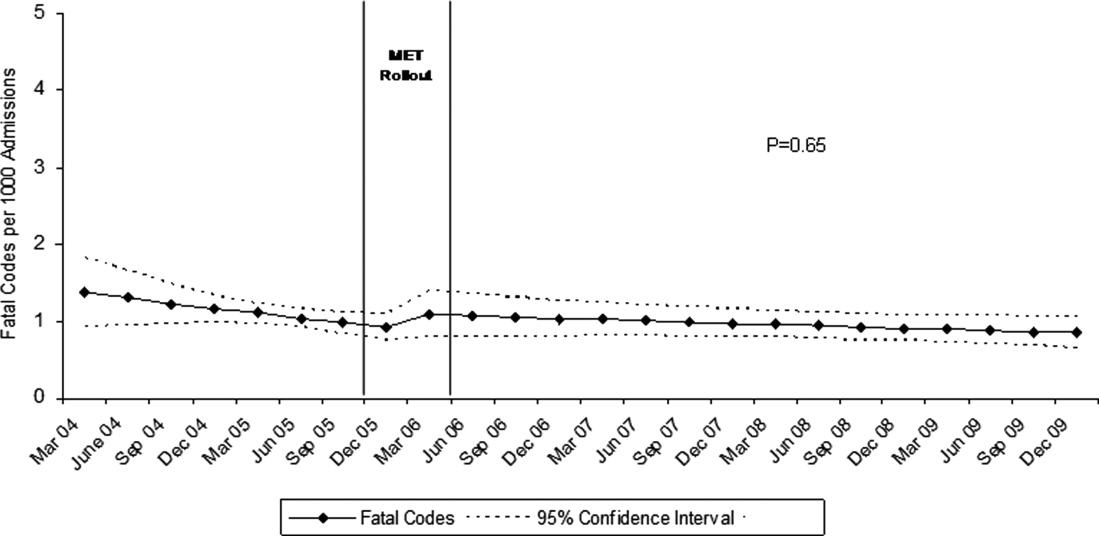

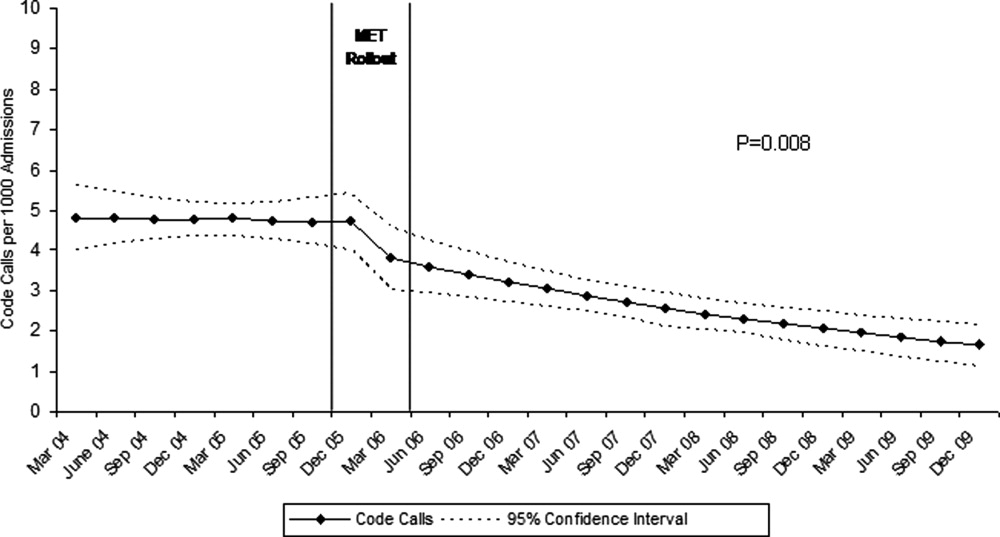

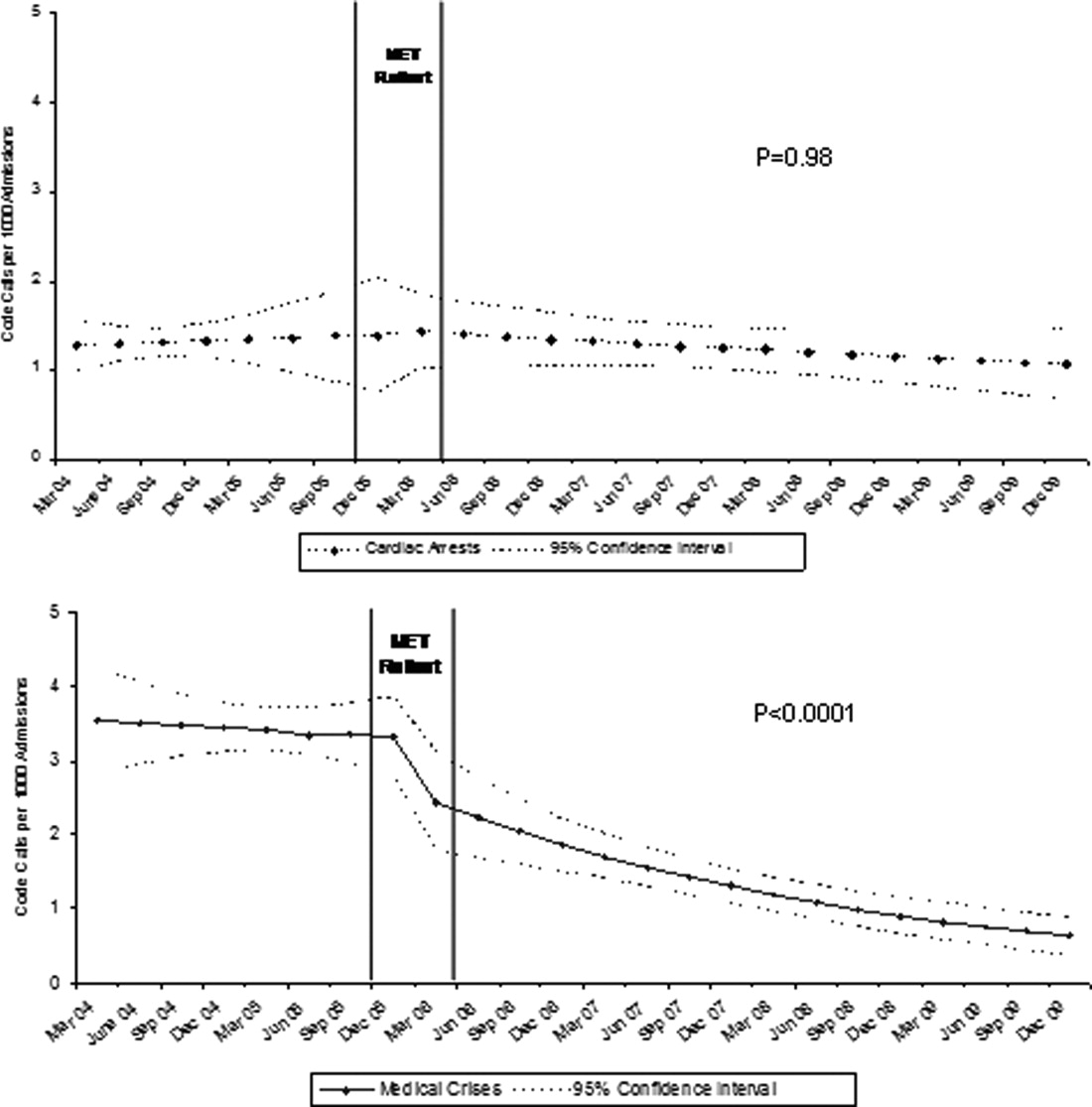

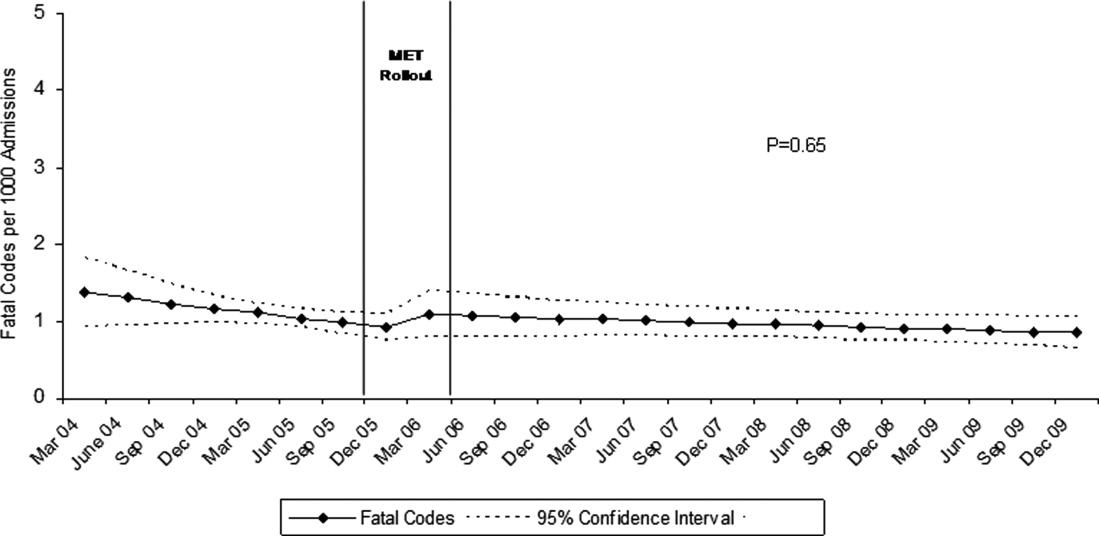

Between January 2004 and December of 2009, the hospital case mix index remained constant, and there were a total of 1202 codes called. The majority (62%) took place outside of critical care units. Linear contrasts of pre‐piecewise and post‐piecewise intercepts revealed that overall code calls declined significantly between pre‐implementation and post‐implementation of the MET from 7.30 (95% CI 5.81, 9.16) codes called per 1000 admissions to 4.21 (95% CI 3.42, 5.18) calls per 1000 admissions (Figure 1; also see Supporting Web Appendix Table 2 in the online version of this article). Outside of critical care, code calls declined from 4.70 (95% CI 3.92, 5.63) before the MET was implemented to 3.11 (95% CI 2.44, 3.97) afterwards (Figure 2); this was due primarily to a decrease in medical crises, which averaged 3.29 events per 1000 admissions (95% CI 2.70, 4.02) before implementation and decreased to 1.72 (95% CI 1.28, 2.31) afterwards, whereas cardiac arrests did not change significantly (Figure 3). Following implementation, code calls within critical care also declined significantly, from 2.59 events per 1000 admissions (95% CI 1.82, 3.69) before to 1.24 events per 1000 admissions (95% CI 0.94, 1.63) afterwards. The change in codes called within critical care was smaller, however, and included reductions in both cardiac arrests ( 0.84 events, P = 0.01) and medical crises ( 0.55, P = 0.08). There was no significant change in the rate of fatal codes per 1000 admissions ( +0.06, P = 0.65) (Figure 4). Overall hospital mortality remained steady at 22.0 deaths per 1000 admissions throughout the study period.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we detail the implementation of a novel hospitalist‐led medical emergency team at a large academic medical center over a period of 4 years. The team, which consisted of the patient's physician, a critical care nurse, a respiratory therapist, and an intravenous therapist, achieved full implementation within 6 months, was well received by the nursing staff, and was associated with a 42% decrease in code calls hospital‐wide. Most of the overall reduction was due to a reduction in codes called for medical crises outside of critical care, accompanied by a lesser reduction in codes called for cardiac arrests and medical crises within critical care units. There was no significant effect on the rate of cardiac arrest outside critical care. More importantly, there was no change in the rate of fatal codes or overall hospital mortality.

The idea of early intervention to prevent deterioration among hospitalized patients appeals to the concept that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Like many other preventive interventions, rapid response systems have not always delivered on this promise. Since several early reports from Australia2 suggested that medical emergency teams could reduce not only cardiopulmonary arrests, but overall hospital mortality, there has been a rapid proliferation in their implementation, spurred on by the IHI's 100,000 Lives Campaign, which incorporated rapid response systems as one of 6 hospital‐wide interventions aimed at reducing harm and mortality.13 Subsequent randomized trials have both reproduced and refuted the early observational results. A ward‐randomized trial within 1 British hospital found a 50% reduction in hospital mortality for wards assigned to have an RRT,14 while a cluster randomized trial conducted at 23 Australian hospitals found no difference in rates of cardiac arrest or mortality between hospitals implementing METs and those continuing with usual care.7 Interestingly, in the Australian trial, the rates of cardiac arrest and mortality declined for both groups compared to historical controls, an important limitation to observational trials. Reports from single‐institution observational trials are also divided between those that found a reduction in mortality following implementation and those that did not. A recent meta‐analysis reported that there was too much heterogeneity among these trials to reach a conclusion about the benefits of rapid response systems.15

Our study adds to this literature in several ways. First, our MET design, which included the patient's physician (as opposed to an intensive care physician), was different from those previously studied. Including the patient's physician increases the team's knowledge of the patient and disease, and may improve physician acceptance of METs. In addition, our study provides 4 full years of follow‐up. Second, our rate of MET activation (18 calls/1000 admissions) was 2 to 3 times higher than that seen in most other studies,16 thus, the lack of mortality benefit was not likely the result of underuse. Third, our hospital employs a large number of hospitalists whose continuous presence might be expected to attenuate the benefits of an MET. Indeed, our initial rate of codes (7.5/1000 admissions) was similar to the post‐intervention rate in other studies.4 Nevertheless, the decrease in the overall rate of code calls following implementation of our MET was similar to that observed by others.17 Finally, our stratification of code calls inside critical care (where the MET was not deployed) and outside critical care, as well as the division of codes into cardiac arrest (where intervention is often unsuccessful) and other medical crises (primarily respiratory distress), gives further insight into how METs might work. As expected, we found that outside critical care only, codes called for medical crises declined, implying that the main effect of the MET was to provide early interventions for patients who were not likely to die anyway (eg, respiratory care for patients with respiratory distress or intravenous fluids for hypotensive patients). Instead of intervening to prevent death, MET may avoid emergent intubation by providing respiratory therapy and/or urgent intubation. In addition, it represents a less‐intense option for responding to nonlife‐threatening emergencies, such as seizures or syncope. As codes were no longer called for these types of crises, the rate of code calls necessarily fell. The reason that code calls declined inside critical care is less clear. It could be that patients transferred to critical care by the MET were less likely to code than those transferred before implementation, or the decline might be due to other factors that were not evaluated. Regardless, it is clear that the MET did not simply relocate codes to critical care units.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is an observational study and cannot account for other confounders relating to temporal trends in the hospital. However, our long time window allowed us to examine trends over several years. For 2 years prior to implementation of the MET, there was no decline at all in the rate of code calls, followed by an immediate and sustained drop after implementation. Other interventions, including ventilator‐associated pneumonia bundles, sepsis bundles, and advanced cardiac life support simulation training were also implemented at different times during the study period. However, the stark demarcation in code call rates coinciding with MET implementation makes it less likely that these other interventions were responsible for the observed decline. Second, our study was limited to a single institution and a single type of MET. Our findings may not apply to other types of institutions with different staffing arrangements or a different hospital culture, nor would they necessarily apply to different types of MET. Third, our nurse surveys were not collected anonymously, and this may have affected the nurses' responses. Finally, we did not collect physiological parameters on our patients, so we cannot state with certainty what the MET intervention accomplished.