User login

FDA: Increased PAH Risk Seen With Dasatinib

Treatment with the leukemia drug dasatinib has been associated with an increased risk for pulmonary arterial hypertension, which can occur at any time after starting treatment, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Oct. 11.

None of the cases was fatal, and PAH "may be reversible" if treatment is discontinued, according to the statement, posted on the agency’s MedWatch site.

Dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb, is approved for treating certain adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). It is an oral therapy, administered once daily.

Since dasatinib was approved in 2006, the BMS global pharmacovigilance database has identified cases of PAH in treated patients, the statement said. In 12 of these cases, right heart catheterization confirmed the diagnosis, and dasatinib was considered "the most likely cause," the FDA said. These patients had developed symptoms at various time intervals after starting treatment, including more than 12 months afterward, and they often were taking other medications or had comorbidities, so "there may be a combination of factors contributing to the development of PAH" in patients taking dasatinib, the FDA said.

Because dyspnea, fatigue, hypoxia, fluid retention, and other PAH symptoms overlap with those of other conditions, "a diagnosis of Sprycel-associated PAH should be considered" if other causes have been ruled out in symptomatic patients, the FDA advises. Health care professionals should also evaluate patients for signs and symptoms of underlying cardiopulmonary disease before starting treatment and during treatment. The drug should be permanently discontinued if a diagnosis of PAH is confirmed.

Improvements in hemodynamic and clinical parameters were observed following discontinuation in some patients, the FDA statement said.

This information has been added to the drug’s prescribing information. Serious adverse events associated with dasatinib should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

Treatment with the leukemia drug dasatinib has been associated with an increased risk for pulmonary arterial hypertension, which can occur at any time after starting treatment, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Oct. 11.

None of the cases was fatal, and PAH "may be reversible" if treatment is discontinued, according to the statement, posted on the agency’s MedWatch site.

Dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb, is approved for treating certain adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). It is an oral therapy, administered once daily.

Since dasatinib was approved in 2006, the BMS global pharmacovigilance database has identified cases of PAH in treated patients, the statement said. In 12 of these cases, right heart catheterization confirmed the diagnosis, and dasatinib was considered "the most likely cause," the FDA said. These patients had developed symptoms at various time intervals after starting treatment, including more than 12 months afterward, and they often were taking other medications or had comorbidities, so "there may be a combination of factors contributing to the development of PAH" in patients taking dasatinib, the FDA said.

Because dyspnea, fatigue, hypoxia, fluid retention, and other PAH symptoms overlap with those of other conditions, "a diagnosis of Sprycel-associated PAH should be considered" if other causes have been ruled out in symptomatic patients, the FDA advises. Health care professionals should also evaluate patients for signs and symptoms of underlying cardiopulmonary disease before starting treatment and during treatment. The drug should be permanently discontinued if a diagnosis of PAH is confirmed.

Improvements in hemodynamic and clinical parameters were observed following discontinuation in some patients, the FDA statement said.

This information has been added to the drug’s prescribing information. Serious adverse events associated with dasatinib should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

Treatment with the leukemia drug dasatinib has been associated with an increased risk for pulmonary arterial hypertension, which can occur at any time after starting treatment, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Oct. 11.

None of the cases was fatal, and PAH "may be reversible" if treatment is discontinued, according to the statement, posted on the agency’s MedWatch site.

Dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb, is approved for treating certain adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). It is an oral therapy, administered once daily.

Since dasatinib was approved in 2006, the BMS global pharmacovigilance database has identified cases of PAH in treated patients, the statement said. In 12 of these cases, right heart catheterization confirmed the diagnosis, and dasatinib was considered "the most likely cause," the FDA said. These patients had developed symptoms at various time intervals after starting treatment, including more than 12 months afterward, and they often were taking other medications or had comorbidities, so "there may be a combination of factors contributing to the development of PAH" in patients taking dasatinib, the FDA said.

Because dyspnea, fatigue, hypoxia, fluid retention, and other PAH symptoms overlap with those of other conditions, "a diagnosis of Sprycel-associated PAH should be considered" if other causes have been ruled out in symptomatic patients, the FDA advises. Health care professionals should also evaluate patients for signs and symptoms of underlying cardiopulmonary disease before starting treatment and during treatment. The drug should be permanently discontinued if a diagnosis of PAH is confirmed.

Improvements in hemodynamic and clinical parameters were observed following discontinuation in some patients, the FDA statement said.

This information has been added to the drug’s prescribing information. Serious adverse events associated with dasatinib should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088.

Age, Location of Bruises Flag Child Abuse

SAN FRANCISCO – The location of bruising and the age of a child can help hone clinical suspicion of child abuse, thanks to a study identifying these predictors.

Because of this study, clinicians now have a better way of raising the topic with parents, which is always a difficult scenario, Dr. Robert Sidbury said.

Instead of physicians having to say that they need to discuss the possibility the bruises might be from nonaccidental trauma, they can now can say, "I’ve got this paper that says bruises in this certain location in a child of this age make me have to check this out," he said at the Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF). "To me, that sounds different."

The study compared the characteristics of bruises on 95 infants aged 0-48 months seen in a pediatric ICU, 53 of whom had accidental trauma and 42 of whom were victims of abuse. Bruising on the torso, ear, or neck ("Think TEN," he suggested) in a child younger than 4 years of age increased the possibility of abuse (Pediatrics 2010;125:67-74).

"Does that mean a child can’t fall and bruise an ear? Of course not," said Dr. Sidbury, chief of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. "It is one thing to add to the list when we’re doing an assessment of the interaction with the parent, interaction with the child, [and] any other signs of trauma – all the things we go through" when considering the possibility of abuse.

"Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise." Also, bruising anywhere on an infant younger than 4 months of age was suggestive of abuse. "Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise," he said. "Is that evidence of abuse? It is not. Is it something we should pay attention to? I think it is."

Bruising on multiple sites was not in the study’s model, but also is suggestive of child abuse, Dr. Sidbury added.

He described seeing a 2-month-old patient with multiple linear, angulated bruises, some of them in the TEN locations. "The index of suspicion was high, and sadly, this was absolutely a case of abuse," he said.

The more data like this that can be gathered, the easier it will make the physician’s job when assessing a child that might be a victim of abuse.

"It is a wrenching issue," he said. "It is wrenching if it is abuse, and it is equally wrenching if you falsely raise the specter of abuse."

Dr. Sidbury said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

SAN FRANCISCO – The location of bruising and the age of a child can help hone clinical suspicion of child abuse, thanks to a study identifying these predictors.

Because of this study, clinicians now have a better way of raising the topic with parents, which is always a difficult scenario, Dr. Robert Sidbury said.

Instead of physicians having to say that they need to discuss the possibility the bruises might be from nonaccidental trauma, they can now can say, "I’ve got this paper that says bruises in this certain location in a child of this age make me have to check this out," he said at the Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF). "To me, that sounds different."

The study compared the characteristics of bruises on 95 infants aged 0-48 months seen in a pediatric ICU, 53 of whom had accidental trauma and 42 of whom were victims of abuse. Bruising on the torso, ear, or neck ("Think TEN," he suggested) in a child younger than 4 years of age increased the possibility of abuse (Pediatrics 2010;125:67-74).

"Does that mean a child can’t fall and bruise an ear? Of course not," said Dr. Sidbury, chief of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. "It is one thing to add to the list when we’re doing an assessment of the interaction with the parent, interaction with the child, [and] any other signs of trauma – all the things we go through" when considering the possibility of abuse.

"Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise." Also, bruising anywhere on an infant younger than 4 months of age was suggestive of abuse. "Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise," he said. "Is that evidence of abuse? It is not. Is it something we should pay attention to? I think it is."

Bruising on multiple sites was not in the study’s model, but also is suggestive of child abuse, Dr. Sidbury added.

He described seeing a 2-month-old patient with multiple linear, angulated bruises, some of them in the TEN locations. "The index of suspicion was high, and sadly, this was absolutely a case of abuse," he said.

The more data like this that can be gathered, the easier it will make the physician’s job when assessing a child that might be a victim of abuse.

"It is a wrenching issue," he said. "It is wrenching if it is abuse, and it is equally wrenching if you falsely raise the specter of abuse."

Dr. Sidbury said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

SAN FRANCISCO – The location of bruising and the age of a child can help hone clinical suspicion of child abuse, thanks to a study identifying these predictors.

Because of this study, clinicians now have a better way of raising the topic with parents, which is always a difficult scenario, Dr. Robert Sidbury said.

Instead of physicians having to say that they need to discuss the possibility the bruises might be from nonaccidental trauma, they can now can say, "I’ve got this paper that says bruises in this certain location in a child of this age make me have to check this out," he said at the Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF). "To me, that sounds different."

The study compared the characteristics of bruises on 95 infants aged 0-48 months seen in a pediatric ICU, 53 of whom had accidental trauma and 42 of whom were victims of abuse. Bruising on the torso, ear, or neck ("Think TEN," he suggested) in a child younger than 4 years of age increased the possibility of abuse (Pediatrics 2010;125:67-74).

"Does that mean a child can’t fall and bruise an ear? Of course not," said Dr. Sidbury, chief of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. "It is one thing to add to the list when we’re doing an assessment of the interaction with the parent, interaction with the child, [and] any other signs of trauma – all the things we go through" when considering the possibility of abuse.

"Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise." Also, bruising anywhere on an infant younger than 4 months of age was suggestive of abuse. "Remember, if they can’t cruise, they can’t bruise," he said. "Is that evidence of abuse? It is not. Is it something we should pay attention to? I think it is."

Bruising on multiple sites was not in the study’s model, but also is suggestive of child abuse, Dr. Sidbury added.

He described seeing a 2-month-old patient with multiple linear, angulated bruises, some of them in the TEN locations. "The index of suspicion was high, and sadly, this was absolutely a case of abuse," he said.

The more data like this that can be gathered, the easier it will make the physician’s job when assessing a child that might be a victim of abuse.

"It is a wrenching issue," he said. "It is wrenching if it is abuse, and it is equally wrenching if you falsely raise the specter of abuse."

Dr. Sidbury said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SDEF WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Cracking the Case

A 43‐year‐old woman presented to an outside hospital with painful plaques and patches on her bilateral lower extremities. Two weeks prior to presentation, she had noticed a single red lesion on her left ankle. Over the next two weeks, the lesion enlarged to involve the lower half of her posterior calf and subsequently turned purple and became exquisitely tender. Similar but smaller purple, tender lesions simultaneously appeared, first over her right shin and then on her bilateral thighs and hips. She also reported fatigue as well as diffuse joint pains in her hands and wrists bilaterally for the past month. She denied any swelling of these joints or functional impairment. She denied fevers, weight loss, headache, sinus symptoms, difficulty breathing, or abdominal pain.

Although we do not yet have a physical exam, the tempo, pattern of spread, and accompanying features allow some early hypotheses to be considered. Distal lower extremity lesions which darkened and spread could be erythema nodosum or erythema induratum. Malignancies rarely have such prominent skin manifestations, although leukemia cutis or an aggressive cutaneous T cell lymphoma might present with disseminated and darkened plaques, and Kaposi's sarcoma is characteristically purple and multifocal. Autoimmune disorders such as sarcoidosis, cutaneous lupus, and psoriasis may similarly present with widespread plaques. Most disseminated infections that start with patches evolve to pustules, ulcers, bullae, or other forms that reflect the invasive nature of the infection; syphilis warrants consideration for any widespread eruption of unknown etiology. Antecedent arthralgias with fatigue suggest an autoimmune condition, although infections such as hepatitis or parvovirus can do the same. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) would be favored initially on account of her demographics and the hand and wrist involvement, and each can be associated with vasculitis.

The significant pain as described is not compatible with most of the aforementioned diagnoses. Its presence, coupled with potential autoimmune symptoms, suggests a vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa (which can have prominent diffuse skin involvement), Henoch Schonlein purpura (with its predilection for the lower extremities, including extension to the hips and buttocks), cryoglobulinemia, or SLE‐ or RA‐associated vasculitis. Calciphylaxis is another ischemic vascular disorder that can cause diffuse dark painful lesions, but this only warrants consideration if advanced renal disease is present.

A skin biopsy ofher right hip was taken at the outside hospital. She was discharged on a two‐week course of prednisone for suspected vasculitis while biopsy results were pending. Over the next two weeks, none of the skin lesions improved, despite compliance with this treatment, and the skin over her left posterior calf and right shin lesions began to erode and bleed. In addition, small purple, tender lesions appeared over the pinnae of both ears. Three weeks after her initial evaluation, she presented to another emergency department for ulcerating skin lesions and worsening pain. At that point, the initial skin biopsy result was available and revealed vasculopathy of the small vessels with thrombi but no vasculitis.

The patient had no children,and denied a history of miscarriages. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She did not report any history of thrombotic events. She started a new job as a software engineer one month ago and was feeling stressed about her new responsibilities. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior and any history of intravenous drug use. She had not traveled recently and did not own any pets. There was no family history of rheumatologic disorders, hypercoagulable states, or thrombotic events.

This picture of occluded but noninflamed vessels shifts the diagnosis away from vasculitis and focuses attention on hypercoagulable states with prominent dermal manifestations, including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLS) and livedoid vasculopathy. In this young woman with arthralgias, consideration of SLE and APLS is warranted. Her recent increase in stress and widespread purpuric and ulcerative lesions could bring to mind a factitious disorder, but the histology results eliminate this possibility.

The patient's temperaturewas 36.5C, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and her heart rate was 65 beats per minute. She was well‐appearing but in moderate pain. She did not have any oral lesions. Her cardiac, respiratory, and abdominal exams were normal. Skin exam revealed a 10‐cm by 4‐cm area of bloody granulation tissue draining serosanguinous fluid, surrounded by stellate palpable netlike purpura on her left posterior calf. There was a similar 4‐cm by 2‐cm ulcerated lesion on her right shin. Both lesions were exquisitely tender to palpation. On her bilateral thighs and hips, there were multiple stellate purpuric patches, all 4 cm in diameter or less, and only minimally tender to palpation. She also had 1‐cm purpuric bullae on the helices of both ears (Figure 1) which were slightly tender to palpation. Splinter hemorrhages were also noted on multiple nail beds bilaterally. Musculoskeletal exam did not reveal any synovitis.

The original purpura on her calf and ear demonstrate a clear demarcation corresponding to cutaneous vascular insufficiency. The development of bullae (ear) and ulceration (calf) are compatible with ischemia. Despite the presence of multiple splinter hemorrhages, the distribution of lesions is very unusual for an embolic phenomenon (eg, endocarditis, cholesterol emboli, or atrial myxoma). The multifocal nature of the skin lesions with progression to well‐demarcated cutaneous necrosis is reminiscent of calciphylaxis or warfarin‐induced skin necrosis, although she lacks the relevant risk factors. A toxin such as cocaine or methamphetamine mediating multifocal vasoconstriction or hypercoagulability should be excluded.

The bilateral ear involvement remains decidedly unusual and makes me wonder if there is something about the ear, such as the nature of its circulation or its potentially lower temperature (as an acral organ) that might render it particularly susceptible, for instance, to cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia‐mediated ischemia.

Laboratory studiesdemonstrated: white blood cell count of 1500/mm3 (37.3% neutrophils, 5.1% lymphocytes, 6.7% monocytes, and 1.3% eosinophils); hemoglobin 9.3 g/dl (mean corpuscular volume 91 fL); platelet count 212/mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 62 mm/hr; C‐reactive protein 14.6 mg/L. Serum electrolytes, liver tests, coagulation studies, and urinalysis were normal. Fecal occult blood test was negative.

Her neutropenia and anemia suggest decreased production in the marrow by infection, malignancy, or toxin, or increased destruction, perhaps from an autoimmune process. The associated infections are usually viral, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), although their linkage with her cutaneous disease is tenuous. It is possible that malignancy could be present in the marrow with resultant dermal hypercoagulability and ischemia, but this seems unlikely. We do not know about any toxins that she has been exposed to, but these hematologic findings would mandate directed inquiry along those lines. In this young woman with cutaneous ulcers secondary to thrombotic vasculopathy, bicytopenia, antecedent arthralgias without synovitis, and elevated inflammatory markers, I favor an autoimmune process such as SLE, which I would evaluate with an antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antiphospholipid antibody studies.

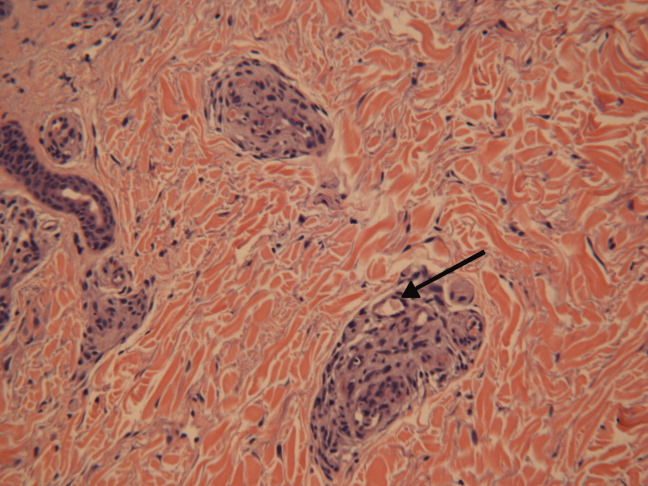

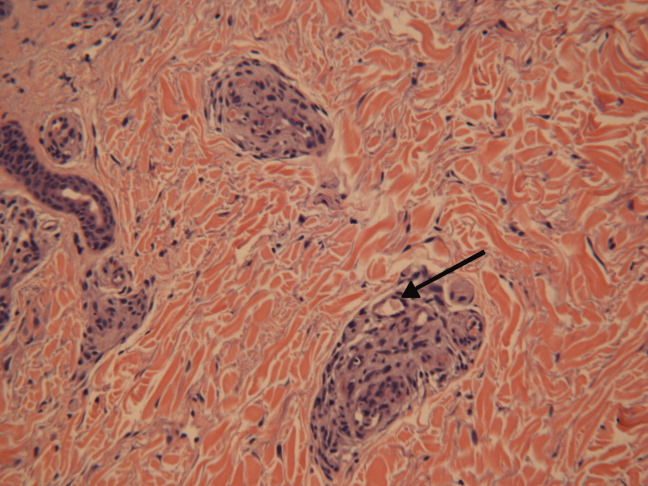

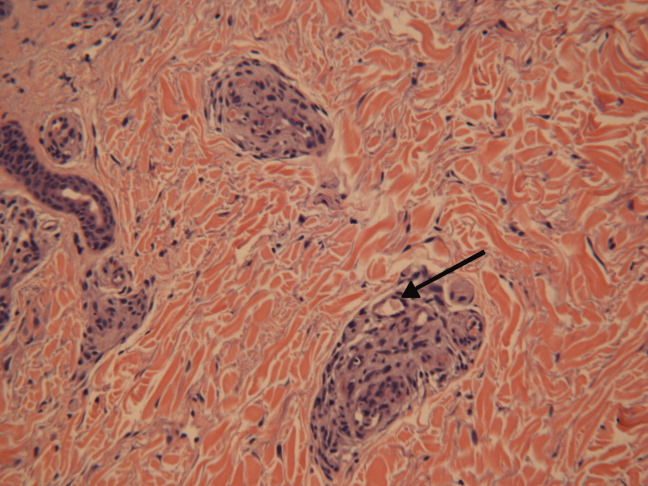

She was admittedto the hospital and received hydromorphone for pain control. Corticosteroids were not administered. Peripheral blood morphology was normal. Antibodies against HIV1 and 2 were negative, as were antibodies against cytomegalovirus, EBV, parvovirus B19, mycoplasma pneumoniae, and hepatitis C virus. Bilateral lower extremity ultrasound was negative for deep vein thrombosis. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. Repeat skin biopsy confirmed small vessel vasculopathy without vasculitis (Figure 2). The results of the following investigations were also negative: ANA, rheumatoid factor, double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA), cyclic citrullinated peptide, ribonucleoprotein (RNP), and anti‐Smith antibodies. C3 and C4 complement levels were normal.

Given how much the histology is driving the clinical reasoning and focusing the differential diagnosis in this case, I agree with the decision to repeat the biopsy. In complex or undiagnosed cases, repeat histology samples allow for confirmation of the original interpretation (often with the perspective of new clinicians and pathologists) and sometimes reveal pathognomonic or additional findings that only appear after the disease has evolved over time. HIV seronegativity helps constrain the differential diagnosis, and parvovirus is another excellent consideration for arthralgias and cytopenias (with the predilection to involve cells lines other than RBCs particularly seen in HIV), although ulcers are not seen with this condition. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is another viral infection that can cause painful skin ulcerations and cytopenias, although the duration and distribution are highly atypical. The negative ANA and dsDNA and normal complement levels make SLE unlikely. The negative lower extremity ultrasound helps frame the thromboses as a local cutaneous process rather than a systemic hypercoagulable state. Although the peripheral blood smear is normal, a bone marrow biopsy will be necessary to exclude a marrow invasive process, such as leukemia or lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy would also provide another opportunity to examine tissue for mycobacteria or fungi which can cause ulcerations and cytopenias, although there is little reason to suspect she is susceptible to those pathogens. As this clinical picture fails to fit clearly with an infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic disorder, I would revisit the possibility of toxinsprescription, complementary, over‐the‐counter, or illegal (eg, cocaine) at this time.

In further discussionwith the patient, she reported using cocaine intranasally for the past three months. Her urine toxicology was positive for cocaine. She was found to have positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p‐ANCA), antimyeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies, anticardiolipin (ACL) antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant (LAC). By hospital day 3, her lesions had significantly improved without any intervention, and her absolute neutrophil count increased to 1080/mm3.

The presence of widespread cutaneous ischemia (with bland thrombosis) and detectable ACL and LAC antibodies is compatible with APLS; the APLS could be deemed primary, because there is no clear associated rheumatologic or other systemic disease. However, neutropenia is not a characteristic of APLS, which has thrombocytopenia as its more frequently associated hematologic abnormality. Livedoid vasculopathy, a related disorder, is also supported by the ACL and LAC results, but also does not feature neutropenia. While the presence of diffuse thrombosis could be attributed to a widespread secondary effect of cocaine vasoconstriction, the appearance of ANCA (which can be drug‐induced, eg, propylthiouracil [PTU]) and the slowly resolving neutropenia during hospitalization without specific treatment is very suggestive of a toxin. The demographic, diffuse skin ulcers, and hematologic and serologic profile is compatible with the recently described toxidrome related to levamisole adulteration of cocaine.

A send‐out studyof a urine sample returned positive for levamisole. Based on purpuric skin lesions with a predilection for the ears, agranulocytosis, and skin biopsy revealing thrombotic vasculopathy, she was diagnosed with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure. One week after discharge, her lower extremity pain and ulcerations were significantly improved. Her absolute neutrophil count increased to 2820/mm.3 Her urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine.

DISCUSSION

Levamisole was initially developed in 1964 as an antihelminthic agent. Its incidentally discovered immunomodulatory effects led to trials for the treatment of chronic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic diseases,1 and nephrotic syndrome in children.2 By 1990, 3 major studies supported levamisole as an adjunctive therapy in melanoma3 and colon cancer.4

Although levamisole appeared to be nontoxic at single or low doses, long‐term use in clinical trials demonstrated that 2.5%‐13% of patients developed life‐threatening agranulocytosis, and up to 10% of those instances resulted in death.5 A distinctive cutaneous pseudovasculitis was noted in children on therapeutic levamisole. They presented with purpura that had a predilection for the ears, cheeks, and thighs,6 and positive serologic markers for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies. Skin biopsies of the purpuric lesions revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, and/or vascular occlusions.

Levamisole was withdrawn from the market in 2000 in the United States due to its side effects,7 but quickly found its way onto the black market. It was first detected in cocaine in 2002, and the percentage of cocaine containing levamisole has steadily been increasing since then. In July 2009, over 70% of cocaine seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration was found to contain levamisole.8 It is unclear exactly why this drug is used as an adulterant in cocaine. Theories include potentiation of the euphoric effects of cocaine, serving as a bulking agent, or functioning as a chemical signature to track distribution.9

The resurgence of levamisole has brought a new face to a problem seen over a decade ago. Current reports of levamisole toxicity describe adults presenting with purpura preferentially involving the ears, neutropenia, positive ANCA, and positive antiphospholipid antibodies.1012 Since 2002, there have been at least 20 confirmed cases of agranulocytosis and two deaths associated with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine.8, 13, 14 In September 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a public health alert warning of an impending increase in levamisole‐related illness.

Levamisole is not detected on routine toxicology screens, but can be tested for using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. Most laboratories do not offer testing for levamisole and send‐out testing is required. Given its half‐life of 5.6 hours, levamisole can only be detected in the blood within 24 hours, and in the urine within 48‐72 hours of exposure.15, 16 Urine samples are preferred over blood samples, since blood levels decline more rapidly and have lower sensitivity. Cocaine can also be sent out to local or state forensics laboratories to be tested for levamisole. The only definitive treatment for levamisole‐induced cutaneous pseudovasculitis and neutropenia is cessation of toxin exposure.

Although the discussant had familiarity with this toxidrome from local and published cases, he was only able to settle on levamisole toxicity after a series of competing hypotheses were ruled out on the basis of irreconcilable features (vasculitis and histology results; APLS and neutropenia; SLE and negative ANA with no visceral involvement) and by using analogical reasoning (eg, to infer the presence of a toxin on the basis of neutropenia [as seen with chemotherapy and other drugs] and ANCA induction [as seen with PTU]). It was a laborious process of hypothesis testing, but one that ultimately allowed him to crack the case.

Key Teaching Points

-

In patients presenting with neutropenia and purpuric skin lesionsparticularly with a predilection for the earsconsider levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure.

-

Tests supporting this diagnosis include positive serologies for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies, and skin biopsies that show leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, or vascular occlusion. Urine studies for levamisole are definitive if sent within 48 to 72 hours of exposure.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

- ,.Levamisole, the story and the lessons.Int J Immunopharmocol.1992;14(3):481–486.

- British Association for Paediatric Nephrology.Levamisole for corticosteroid‐dependent nephrotic syndrome in childhood.Lancet.1991;337:1555–1557.

- ,,,,.Improved survival in patients with poor‐prognosis malignant melanoma treated with adjuvant levamisole: a phase III study by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group.J Clin Oncol.1991;9:729–735.

- ,,.Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma.N Engl J Med.1990;322:352–358.

- ,,.Studies on levamisole‐induced agranulocytosis.Blood.1980;56(3):388–396.

- ,,.Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long‐term treatment with levamisole in children.Br J Dermatol.1999;140:948–951.

- . Janssen Discontinues Ergamisol. Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3374/is_18_22/ai_68536218/. Accessed July 25,2010.

- SAMHSA. Nationwide Public Health Alert Issued Concerning Life‐Threatening Risk Posed by Cocaine Laced with Veterinary Anti‐Parasite Drug. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/090921vet5101.aspx. Accessed July 20,2010.

- .Unusual adulterants in cocaine seized on Italian clandestine market.Forensic Sci Int.2007;172(2–3):e1.

- ,,.Levamisole‐induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Jun 12.

- ,,,.Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.Ann Intern Med.2010;1;152(11):758–759.

- ,,,,.Cocaine‐associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit?J Am Acad Dermatol.2010;Mar 19.

- ,,,.A confirmed case of agranulocytosis after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Apr 1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four States, March 2008–November 2009.MMWR.2009;58(49):1381–1385.

- ,,.Levamisole as a contaminant of illicit cocaine.Journal of the Clandestine Laboratory Investigating Chemists Association.2006;16:6–11. Available at: http://www.tiaft2006.org/proceedings/pdf/PT‐p‐06.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- . Cocaine Cutting Agents—A Discussion. Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Alberta. Available at: http://www.vandu.org/documents/Levamisole_Cocaine.pdf. Accessed July 20,2010.

A 43‐year‐old woman presented to an outside hospital with painful plaques and patches on her bilateral lower extremities. Two weeks prior to presentation, she had noticed a single red lesion on her left ankle. Over the next two weeks, the lesion enlarged to involve the lower half of her posterior calf and subsequently turned purple and became exquisitely tender. Similar but smaller purple, tender lesions simultaneously appeared, first over her right shin and then on her bilateral thighs and hips. She also reported fatigue as well as diffuse joint pains in her hands and wrists bilaterally for the past month. She denied any swelling of these joints or functional impairment. She denied fevers, weight loss, headache, sinus symptoms, difficulty breathing, or abdominal pain.

Although we do not yet have a physical exam, the tempo, pattern of spread, and accompanying features allow some early hypotheses to be considered. Distal lower extremity lesions which darkened and spread could be erythema nodosum or erythema induratum. Malignancies rarely have such prominent skin manifestations, although leukemia cutis or an aggressive cutaneous T cell lymphoma might present with disseminated and darkened plaques, and Kaposi's sarcoma is characteristically purple and multifocal. Autoimmune disorders such as sarcoidosis, cutaneous lupus, and psoriasis may similarly present with widespread plaques. Most disseminated infections that start with patches evolve to pustules, ulcers, bullae, or other forms that reflect the invasive nature of the infection; syphilis warrants consideration for any widespread eruption of unknown etiology. Antecedent arthralgias with fatigue suggest an autoimmune condition, although infections such as hepatitis or parvovirus can do the same. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) would be favored initially on account of her demographics and the hand and wrist involvement, and each can be associated with vasculitis.

The significant pain as described is not compatible with most of the aforementioned diagnoses. Its presence, coupled with potential autoimmune symptoms, suggests a vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa (which can have prominent diffuse skin involvement), Henoch Schonlein purpura (with its predilection for the lower extremities, including extension to the hips and buttocks), cryoglobulinemia, or SLE‐ or RA‐associated vasculitis. Calciphylaxis is another ischemic vascular disorder that can cause diffuse dark painful lesions, but this only warrants consideration if advanced renal disease is present.

A skin biopsy ofher right hip was taken at the outside hospital. She was discharged on a two‐week course of prednisone for suspected vasculitis while biopsy results were pending. Over the next two weeks, none of the skin lesions improved, despite compliance with this treatment, and the skin over her left posterior calf and right shin lesions began to erode and bleed. In addition, small purple, tender lesions appeared over the pinnae of both ears. Three weeks after her initial evaluation, she presented to another emergency department for ulcerating skin lesions and worsening pain. At that point, the initial skin biopsy result was available and revealed vasculopathy of the small vessels with thrombi but no vasculitis.

The patient had no children,and denied a history of miscarriages. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She did not report any history of thrombotic events. She started a new job as a software engineer one month ago and was feeling stressed about her new responsibilities. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior and any history of intravenous drug use. She had not traveled recently and did not own any pets. There was no family history of rheumatologic disorders, hypercoagulable states, or thrombotic events.

This picture of occluded but noninflamed vessels shifts the diagnosis away from vasculitis and focuses attention on hypercoagulable states with prominent dermal manifestations, including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLS) and livedoid vasculopathy. In this young woman with arthralgias, consideration of SLE and APLS is warranted. Her recent increase in stress and widespread purpuric and ulcerative lesions could bring to mind a factitious disorder, but the histology results eliminate this possibility.

The patient's temperaturewas 36.5C, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and her heart rate was 65 beats per minute. She was well‐appearing but in moderate pain. She did not have any oral lesions. Her cardiac, respiratory, and abdominal exams were normal. Skin exam revealed a 10‐cm by 4‐cm area of bloody granulation tissue draining serosanguinous fluid, surrounded by stellate palpable netlike purpura on her left posterior calf. There was a similar 4‐cm by 2‐cm ulcerated lesion on her right shin. Both lesions were exquisitely tender to palpation. On her bilateral thighs and hips, there were multiple stellate purpuric patches, all 4 cm in diameter or less, and only minimally tender to palpation. She also had 1‐cm purpuric bullae on the helices of both ears (Figure 1) which were slightly tender to palpation. Splinter hemorrhages were also noted on multiple nail beds bilaterally. Musculoskeletal exam did not reveal any synovitis.

The original purpura on her calf and ear demonstrate a clear demarcation corresponding to cutaneous vascular insufficiency. The development of bullae (ear) and ulceration (calf) are compatible with ischemia. Despite the presence of multiple splinter hemorrhages, the distribution of lesions is very unusual for an embolic phenomenon (eg, endocarditis, cholesterol emboli, or atrial myxoma). The multifocal nature of the skin lesions with progression to well‐demarcated cutaneous necrosis is reminiscent of calciphylaxis or warfarin‐induced skin necrosis, although she lacks the relevant risk factors. A toxin such as cocaine or methamphetamine mediating multifocal vasoconstriction or hypercoagulability should be excluded.

The bilateral ear involvement remains decidedly unusual and makes me wonder if there is something about the ear, such as the nature of its circulation or its potentially lower temperature (as an acral organ) that might render it particularly susceptible, for instance, to cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia‐mediated ischemia.

Laboratory studiesdemonstrated: white blood cell count of 1500/mm3 (37.3% neutrophils, 5.1% lymphocytes, 6.7% monocytes, and 1.3% eosinophils); hemoglobin 9.3 g/dl (mean corpuscular volume 91 fL); platelet count 212/mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 62 mm/hr; C‐reactive protein 14.6 mg/L. Serum electrolytes, liver tests, coagulation studies, and urinalysis were normal. Fecal occult blood test was negative.

Her neutropenia and anemia suggest decreased production in the marrow by infection, malignancy, or toxin, or increased destruction, perhaps from an autoimmune process. The associated infections are usually viral, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), although their linkage with her cutaneous disease is tenuous. It is possible that malignancy could be present in the marrow with resultant dermal hypercoagulability and ischemia, but this seems unlikely. We do not know about any toxins that she has been exposed to, but these hematologic findings would mandate directed inquiry along those lines. In this young woman with cutaneous ulcers secondary to thrombotic vasculopathy, bicytopenia, antecedent arthralgias without synovitis, and elevated inflammatory markers, I favor an autoimmune process such as SLE, which I would evaluate with an antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antiphospholipid antibody studies.

She was admittedto the hospital and received hydromorphone for pain control. Corticosteroids were not administered. Peripheral blood morphology was normal. Antibodies against HIV1 and 2 were negative, as were antibodies against cytomegalovirus, EBV, parvovirus B19, mycoplasma pneumoniae, and hepatitis C virus. Bilateral lower extremity ultrasound was negative for deep vein thrombosis. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. Repeat skin biopsy confirmed small vessel vasculopathy without vasculitis (Figure 2). The results of the following investigations were also negative: ANA, rheumatoid factor, double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA), cyclic citrullinated peptide, ribonucleoprotein (RNP), and anti‐Smith antibodies. C3 and C4 complement levels were normal.

Given how much the histology is driving the clinical reasoning and focusing the differential diagnosis in this case, I agree with the decision to repeat the biopsy. In complex or undiagnosed cases, repeat histology samples allow for confirmation of the original interpretation (often with the perspective of new clinicians and pathologists) and sometimes reveal pathognomonic or additional findings that only appear after the disease has evolved over time. HIV seronegativity helps constrain the differential diagnosis, and parvovirus is another excellent consideration for arthralgias and cytopenias (with the predilection to involve cells lines other than RBCs particularly seen in HIV), although ulcers are not seen with this condition. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is another viral infection that can cause painful skin ulcerations and cytopenias, although the duration and distribution are highly atypical. The negative ANA and dsDNA and normal complement levels make SLE unlikely. The negative lower extremity ultrasound helps frame the thromboses as a local cutaneous process rather than a systemic hypercoagulable state. Although the peripheral blood smear is normal, a bone marrow biopsy will be necessary to exclude a marrow invasive process, such as leukemia or lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy would also provide another opportunity to examine tissue for mycobacteria or fungi which can cause ulcerations and cytopenias, although there is little reason to suspect she is susceptible to those pathogens. As this clinical picture fails to fit clearly with an infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic disorder, I would revisit the possibility of toxinsprescription, complementary, over‐the‐counter, or illegal (eg, cocaine) at this time.

In further discussionwith the patient, she reported using cocaine intranasally for the past three months. Her urine toxicology was positive for cocaine. She was found to have positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p‐ANCA), antimyeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies, anticardiolipin (ACL) antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant (LAC). By hospital day 3, her lesions had significantly improved without any intervention, and her absolute neutrophil count increased to 1080/mm3.

The presence of widespread cutaneous ischemia (with bland thrombosis) and detectable ACL and LAC antibodies is compatible with APLS; the APLS could be deemed primary, because there is no clear associated rheumatologic or other systemic disease. However, neutropenia is not a characteristic of APLS, which has thrombocytopenia as its more frequently associated hematologic abnormality. Livedoid vasculopathy, a related disorder, is also supported by the ACL and LAC results, but also does not feature neutropenia. While the presence of diffuse thrombosis could be attributed to a widespread secondary effect of cocaine vasoconstriction, the appearance of ANCA (which can be drug‐induced, eg, propylthiouracil [PTU]) and the slowly resolving neutropenia during hospitalization without specific treatment is very suggestive of a toxin. The demographic, diffuse skin ulcers, and hematologic and serologic profile is compatible with the recently described toxidrome related to levamisole adulteration of cocaine.

A send‐out studyof a urine sample returned positive for levamisole. Based on purpuric skin lesions with a predilection for the ears, agranulocytosis, and skin biopsy revealing thrombotic vasculopathy, she was diagnosed with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure. One week after discharge, her lower extremity pain and ulcerations were significantly improved. Her absolute neutrophil count increased to 2820/mm.3 Her urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine.

DISCUSSION

Levamisole was initially developed in 1964 as an antihelminthic agent. Its incidentally discovered immunomodulatory effects led to trials for the treatment of chronic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic diseases,1 and nephrotic syndrome in children.2 By 1990, 3 major studies supported levamisole as an adjunctive therapy in melanoma3 and colon cancer.4

Although levamisole appeared to be nontoxic at single or low doses, long‐term use in clinical trials demonstrated that 2.5%‐13% of patients developed life‐threatening agranulocytosis, and up to 10% of those instances resulted in death.5 A distinctive cutaneous pseudovasculitis was noted in children on therapeutic levamisole. They presented with purpura that had a predilection for the ears, cheeks, and thighs,6 and positive serologic markers for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies. Skin biopsies of the purpuric lesions revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, and/or vascular occlusions.

Levamisole was withdrawn from the market in 2000 in the United States due to its side effects,7 but quickly found its way onto the black market. It was first detected in cocaine in 2002, and the percentage of cocaine containing levamisole has steadily been increasing since then. In July 2009, over 70% of cocaine seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration was found to contain levamisole.8 It is unclear exactly why this drug is used as an adulterant in cocaine. Theories include potentiation of the euphoric effects of cocaine, serving as a bulking agent, or functioning as a chemical signature to track distribution.9

The resurgence of levamisole has brought a new face to a problem seen over a decade ago. Current reports of levamisole toxicity describe adults presenting with purpura preferentially involving the ears, neutropenia, positive ANCA, and positive antiphospholipid antibodies.1012 Since 2002, there have been at least 20 confirmed cases of agranulocytosis and two deaths associated with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine.8, 13, 14 In September 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a public health alert warning of an impending increase in levamisole‐related illness.

Levamisole is not detected on routine toxicology screens, but can be tested for using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. Most laboratories do not offer testing for levamisole and send‐out testing is required. Given its half‐life of 5.6 hours, levamisole can only be detected in the blood within 24 hours, and in the urine within 48‐72 hours of exposure.15, 16 Urine samples are preferred over blood samples, since blood levels decline more rapidly and have lower sensitivity. Cocaine can also be sent out to local or state forensics laboratories to be tested for levamisole. The only definitive treatment for levamisole‐induced cutaneous pseudovasculitis and neutropenia is cessation of toxin exposure.

Although the discussant had familiarity with this toxidrome from local and published cases, he was only able to settle on levamisole toxicity after a series of competing hypotheses were ruled out on the basis of irreconcilable features (vasculitis and histology results; APLS and neutropenia; SLE and negative ANA with no visceral involvement) and by using analogical reasoning (eg, to infer the presence of a toxin on the basis of neutropenia [as seen with chemotherapy and other drugs] and ANCA induction [as seen with PTU]). It was a laborious process of hypothesis testing, but one that ultimately allowed him to crack the case.

Key Teaching Points

-

In patients presenting with neutropenia and purpuric skin lesionsparticularly with a predilection for the earsconsider levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure.

-

Tests supporting this diagnosis include positive serologies for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies, and skin biopsies that show leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, or vascular occlusion. Urine studies for levamisole are definitive if sent within 48 to 72 hours of exposure.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A 43‐year‐old woman presented to an outside hospital with painful plaques and patches on her bilateral lower extremities. Two weeks prior to presentation, she had noticed a single red lesion on her left ankle. Over the next two weeks, the lesion enlarged to involve the lower half of her posterior calf and subsequently turned purple and became exquisitely tender. Similar but smaller purple, tender lesions simultaneously appeared, first over her right shin and then on her bilateral thighs and hips. She also reported fatigue as well as diffuse joint pains in her hands and wrists bilaterally for the past month. She denied any swelling of these joints or functional impairment. She denied fevers, weight loss, headache, sinus symptoms, difficulty breathing, or abdominal pain.

Although we do not yet have a physical exam, the tempo, pattern of spread, and accompanying features allow some early hypotheses to be considered. Distal lower extremity lesions which darkened and spread could be erythema nodosum or erythema induratum. Malignancies rarely have such prominent skin manifestations, although leukemia cutis or an aggressive cutaneous T cell lymphoma might present with disseminated and darkened plaques, and Kaposi's sarcoma is characteristically purple and multifocal. Autoimmune disorders such as sarcoidosis, cutaneous lupus, and psoriasis may similarly present with widespread plaques. Most disseminated infections that start with patches evolve to pustules, ulcers, bullae, or other forms that reflect the invasive nature of the infection; syphilis warrants consideration for any widespread eruption of unknown etiology. Antecedent arthralgias with fatigue suggest an autoimmune condition, although infections such as hepatitis or parvovirus can do the same. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) would be favored initially on account of her demographics and the hand and wrist involvement, and each can be associated with vasculitis.

The significant pain as described is not compatible with most of the aforementioned diagnoses. Its presence, coupled with potential autoimmune symptoms, suggests a vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa (which can have prominent diffuse skin involvement), Henoch Schonlein purpura (with its predilection for the lower extremities, including extension to the hips and buttocks), cryoglobulinemia, or SLE‐ or RA‐associated vasculitis. Calciphylaxis is another ischemic vascular disorder that can cause diffuse dark painful lesions, but this only warrants consideration if advanced renal disease is present.

A skin biopsy ofher right hip was taken at the outside hospital. She was discharged on a two‐week course of prednisone for suspected vasculitis while biopsy results were pending. Over the next two weeks, none of the skin lesions improved, despite compliance with this treatment, and the skin over her left posterior calf and right shin lesions began to erode and bleed. In addition, small purple, tender lesions appeared over the pinnae of both ears. Three weeks after her initial evaluation, she presented to another emergency department for ulcerating skin lesions and worsening pain. At that point, the initial skin biopsy result was available and revealed vasculopathy of the small vessels with thrombi but no vasculitis.

The patient had no children,and denied a history of miscarriages. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She did not report any history of thrombotic events. She started a new job as a software engineer one month ago and was feeling stressed about her new responsibilities. She denied any high‐risk sexual behavior and any history of intravenous drug use. She had not traveled recently and did not own any pets. There was no family history of rheumatologic disorders, hypercoagulable states, or thrombotic events.

This picture of occluded but noninflamed vessels shifts the diagnosis away from vasculitis and focuses attention on hypercoagulable states with prominent dermal manifestations, including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLS) and livedoid vasculopathy. In this young woman with arthralgias, consideration of SLE and APLS is warranted. Her recent increase in stress and widespread purpuric and ulcerative lesions could bring to mind a factitious disorder, but the histology results eliminate this possibility.

The patient's temperaturewas 36.5C, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and her heart rate was 65 beats per minute. She was well‐appearing but in moderate pain. She did not have any oral lesions. Her cardiac, respiratory, and abdominal exams were normal. Skin exam revealed a 10‐cm by 4‐cm area of bloody granulation tissue draining serosanguinous fluid, surrounded by stellate palpable netlike purpura on her left posterior calf. There was a similar 4‐cm by 2‐cm ulcerated lesion on her right shin. Both lesions were exquisitely tender to palpation. On her bilateral thighs and hips, there were multiple stellate purpuric patches, all 4 cm in diameter or less, and only minimally tender to palpation. She also had 1‐cm purpuric bullae on the helices of both ears (Figure 1) which were slightly tender to palpation. Splinter hemorrhages were also noted on multiple nail beds bilaterally. Musculoskeletal exam did not reveal any synovitis.

The original purpura on her calf and ear demonstrate a clear demarcation corresponding to cutaneous vascular insufficiency. The development of bullae (ear) and ulceration (calf) are compatible with ischemia. Despite the presence of multiple splinter hemorrhages, the distribution of lesions is very unusual for an embolic phenomenon (eg, endocarditis, cholesterol emboli, or atrial myxoma). The multifocal nature of the skin lesions with progression to well‐demarcated cutaneous necrosis is reminiscent of calciphylaxis or warfarin‐induced skin necrosis, although she lacks the relevant risk factors. A toxin such as cocaine or methamphetamine mediating multifocal vasoconstriction or hypercoagulability should be excluded.

The bilateral ear involvement remains decidedly unusual and makes me wonder if there is something about the ear, such as the nature of its circulation or its potentially lower temperature (as an acral organ) that might render it particularly susceptible, for instance, to cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia‐mediated ischemia.

Laboratory studiesdemonstrated: white blood cell count of 1500/mm3 (37.3% neutrophils, 5.1% lymphocytes, 6.7% monocytes, and 1.3% eosinophils); hemoglobin 9.3 g/dl (mean corpuscular volume 91 fL); platelet count 212/mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 62 mm/hr; C‐reactive protein 14.6 mg/L. Serum electrolytes, liver tests, coagulation studies, and urinalysis were normal. Fecal occult blood test was negative.

Her neutropenia and anemia suggest decreased production in the marrow by infection, malignancy, or toxin, or increased destruction, perhaps from an autoimmune process. The associated infections are usually viral, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), although their linkage with her cutaneous disease is tenuous. It is possible that malignancy could be present in the marrow with resultant dermal hypercoagulability and ischemia, but this seems unlikely. We do not know about any toxins that she has been exposed to, but these hematologic findings would mandate directed inquiry along those lines. In this young woman with cutaneous ulcers secondary to thrombotic vasculopathy, bicytopenia, antecedent arthralgias without synovitis, and elevated inflammatory markers, I favor an autoimmune process such as SLE, which I would evaluate with an antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antiphospholipid antibody studies.

She was admittedto the hospital and received hydromorphone for pain control. Corticosteroids were not administered. Peripheral blood morphology was normal. Antibodies against HIV1 and 2 were negative, as were antibodies against cytomegalovirus, EBV, parvovirus B19, mycoplasma pneumoniae, and hepatitis C virus. Bilateral lower extremity ultrasound was negative for deep vein thrombosis. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. Repeat skin biopsy confirmed small vessel vasculopathy without vasculitis (Figure 2). The results of the following investigations were also negative: ANA, rheumatoid factor, double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA), cyclic citrullinated peptide, ribonucleoprotein (RNP), and anti‐Smith antibodies. C3 and C4 complement levels were normal.

Given how much the histology is driving the clinical reasoning and focusing the differential diagnosis in this case, I agree with the decision to repeat the biopsy. In complex or undiagnosed cases, repeat histology samples allow for confirmation of the original interpretation (often with the perspective of new clinicians and pathologists) and sometimes reveal pathognomonic or additional findings that only appear after the disease has evolved over time. HIV seronegativity helps constrain the differential diagnosis, and parvovirus is another excellent consideration for arthralgias and cytopenias (with the predilection to involve cells lines other than RBCs particularly seen in HIV), although ulcers are not seen with this condition. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is another viral infection that can cause painful skin ulcerations and cytopenias, although the duration and distribution are highly atypical. The negative ANA and dsDNA and normal complement levels make SLE unlikely. The negative lower extremity ultrasound helps frame the thromboses as a local cutaneous process rather than a systemic hypercoagulable state. Although the peripheral blood smear is normal, a bone marrow biopsy will be necessary to exclude a marrow invasive process, such as leukemia or lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy would also provide another opportunity to examine tissue for mycobacteria or fungi which can cause ulcerations and cytopenias, although there is little reason to suspect she is susceptible to those pathogens. As this clinical picture fails to fit clearly with an infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic disorder, I would revisit the possibility of toxinsprescription, complementary, over‐the‐counter, or illegal (eg, cocaine) at this time.

In further discussionwith the patient, she reported using cocaine intranasally for the past three months. Her urine toxicology was positive for cocaine. She was found to have positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p‐ANCA), antimyeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies, anticardiolipin (ACL) antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant (LAC). By hospital day 3, her lesions had significantly improved without any intervention, and her absolute neutrophil count increased to 1080/mm3.

The presence of widespread cutaneous ischemia (with bland thrombosis) and detectable ACL and LAC antibodies is compatible with APLS; the APLS could be deemed primary, because there is no clear associated rheumatologic or other systemic disease. However, neutropenia is not a characteristic of APLS, which has thrombocytopenia as its more frequently associated hematologic abnormality. Livedoid vasculopathy, a related disorder, is also supported by the ACL and LAC results, but also does not feature neutropenia. While the presence of diffuse thrombosis could be attributed to a widespread secondary effect of cocaine vasoconstriction, the appearance of ANCA (which can be drug‐induced, eg, propylthiouracil [PTU]) and the slowly resolving neutropenia during hospitalization without specific treatment is very suggestive of a toxin. The demographic, diffuse skin ulcers, and hematologic and serologic profile is compatible with the recently described toxidrome related to levamisole adulteration of cocaine.

A send‐out studyof a urine sample returned positive for levamisole. Based on purpuric skin lesions with a predilection for the ears, agranulocytosis, and skin biopsy revealing thrombotic vasculopathy, she was diagnosed with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure. One week after discharge, her lower extremity pain and ulcerations were significantly improved. Her absolute neutrophil count increased to 2820/mm.3 Her urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine.

DISCUSSION

Levamisole was initially developed in 1964 as an antihelminthic agent. Its incidentally discovered immunomodulatory effects led to trials for the treatment of chronic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic diseases,1 and nephrotic syndrome in children.2 By 1990, 3 major studies supported levamisole as an adjunctive therapy in melanoma3 and colon cancer.4

Although levamisole appeared to be nontoxic at single or low doses, long‐term use in clinical trials demonstrated that 2.5%‐13% of patients developed life‐threatening agranulocytosis, and up to 10% of those instances resulted in death.5 A distinctive cutaneous pseudovasculitis was noted in children on therapeutic levamisole. They presented with purpura that had a predilection for the ears, cheeks, and thighs,6 and positive serologic markers for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies. Skin biopsies of the purpuric lesions revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, and/or vascular occlusions.

Levamisole was withdrawn from the market in 2000 in the United States due to its side effects,7 but quickly found its way onto the black market. It was first detected in cocaine in 2002, and the percentage of cocaine containing levamisole has steadily been increasing since then. In July 2009, over 70% of cocaine seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration was found to contain levamisole.8 It is unclear exactly why this drug is used as an adulterant in cocaine. Theories include potentiation of the euphoric effects of cocaine, serving as a bulking agent, or functioning as a chemical signature to track distribution.9

The resurgence of levamisole has brought a new face to a problem seen over a decade ago. Current reports of levamisole toxicity describe adults presenting with purpura preferentially involving the ears, neutropenia, positive ANCA, and positive antiphospholipid antibodies.1012 Since 2002, there have been at least 20 confirmed cases of agranulocytosis and two deaths associated with levamisole‐adulterated cocaine.8, 13, 14 In September 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a public health alert warning of an impending increase in levamisole‐related illness.

Levamisole is not detected on routine toxicology screens, but can be tested for using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. Most laboratories do not offer testing for levamisole and send‐out testing is required. Given its half‐life of 5.6 hours, levamisole can only be detected in the blood within 24 hours, and in the urine within 48‐72 hours of exposure.15, 16 Urine samples are preferred over blood samples, since blood levels decline more rapidly and have lower sensitivity. Cocaine can also be sent out to local or state forensics laboratories to be tested for levamisole. The only definitive treatment for levamisole‐induced cutaneous pseudovasculitis and neutropenia is cessation of toxin exposure.

Although the discussant had familiarity with this toxidrome from local and published cases, he was only able to settle on levamisole toxicity after a series of competing hypotheses were ruled out on the basis of irreconcilable features (vasculitis and histology results; APLS and neutropenia; SLE and negative ANA with no visceral involvement) and by using analogical reasoning (eg, to infer the presence of a toxin on the basis of neutropenia [as seen with chemotherapy and other drugs] and ANCA induction [as seen with PTU]). It was a laborious process of hypothesis testing, but one that ultimately allowed him to crack the case.

Key Teaching Points

-

In patients presenting with neutropenia and purpuric skin lesionsparticularly with a predilection for the earsconsider levamisole‐adulterated cocaine exposure.

-

Tests supporting this diagnosis include positive serologies for ANCA and antiphospholipid antibodies, and skin biopsies that show leukocytoclastic vasculitis, thrombotic vasculitis, or vascular occlusion. Urine studies for levamisole are definitive if sent within 48 to 72 hours of exposure.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

- ,.Levamisole, the story and the lessons.Int J Immunopharmocol.1992;14(3):481–486.

- British Association for Paediatric Nephrology.Levamisole for corticosteroid‐dependent nephrotic syndrome in childhood.Lancet.1991;337:1555–1557.

- ,,,,.Improved survival in patients with poor‐prognosis malignant melanoma treated with adjuvant levamisole: a phase III study by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group.J Clin Oncol.1991;9:729–735.

- ,,.Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma.N Engl J Med.1990;322:352–358.

- ,,.Studies on levamisole‐induced agranulocytosis.Blood.1980;56(3):388–396.

- ,,.Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long‐term treatment with levamisole in children.Br J Dermatol.1999;140:948–951.

- . Janssen Discontinues Ergamisol. Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3374/is_18_22/ai_68536218/. Accessed July 25,2010.

- SAMHSA. Nationwide Public Health Alert Issued Concerning Life‐Threatening Risk Posed by Cocaine Laced with Veterinary Anti‐Parasite Drug. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/090921vet5101.aspx. Accessed July 20,2010.

- .Unusual adulterants in cocaine seized on Italian clandestine market.Forensic Sci Int.2007;172(2–3):e1.

- ,,.Levamisole‐induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Jun 12.

- ,,,.Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.Ann Intern Med.2010;1;152(11):758–759.

- ,,,,.Cocaine‐associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit?J Am Acad Dermatol.2010;Mar 19.

- ,,,.A confirmed case of agranulocytosis after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Apr 1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four States, March 2008–November 2009.MMWR.2009;58(49):1381–1385.

- ,,.Levamisole as a contaminant of illicit cocaine.Journal of the Clandestine Laboratory Investigating Chemists Association.2006;16:6–11. Available at: http://www.tiaft2006.org/proceedings/pdf/PT‐p‐06.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- . Cocaine Cutting Agents—A Discussion. Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Alberta. Available at: http://www.vandu.org/documents/Levamisole_Cocaine.pdf. Accessed July 20,2010.

- ,.Levamisole, the story and the lessons.Int J Immunopharmocol.1992;14(3):481–486.

- British Association for Paediatric Nephrology.Levamisole for corticosteroid‐dependent nephrotic syndrome in childhood.Lancet.1991;337:1555–1557.

- ,,,,.Improved survival in patients with poor‐prognosis malignant melanoma treated with adjuvant levamisole: a phase III study by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group.J Clin Oncol.1991;9:729–735.

- ,,.Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma.N Engl J Med.1990;322:352–358.

- ,,.Studies on levamisole‐induced agranulocytosis.Blood.1980;56(3):388–396.

- ,,.Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long‐term treatment with levamisole in children.Br J Dermatol.1999;140:948–951.

- . Janssen Discontinues Ergamisol. Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3374/is_18_22/ai_68536218/. Accessed July 25,2010.

- SAMHSA. Nationwide Public Health Alert Issued Concerning Life‐Threatening Risk Posed by Cocaine Laced with Veterinary Anti‐Parasite Drug. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/090921vet5101.aspx. Accessed July 20,2010.

- .Unusual adulterants in cocaine seized on Italian clandestine market.Forensic Sci Int.2007;172(2–3):e1.

- ,,.Levamisole‐induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Jun 12.

- ,,,.Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.Ann Intern Med.2010;1;152(11):758–759.

- ,,,,.Cocaine‐associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit?J Am Acad Dermatol.2010;Mar 19.

- ,,,.A confirmed case of agranulocytosis after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole.J Med Toxicol.2010;Apr 1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four States, March 2008–November 2009.MMWR.2009;58(49):1381–1385.

- ,,.Levamisole as a contaminant of illicit cocaine.Journal of the Clandestine Laboratory Investigating Chemists Association.2006;16:6–11. Available at: http://www.tiaft2006.org/proceedings/pdf/PT‐p‐06.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- . Cocaine Cutting Agents—A Discussion. Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Alberta. Available at: http://www.vandu.org/documents/Levamisole_Cocaine.pdf. Accessed July 20,2010.

Treating AWS with Oral Baclofen

In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use affects medical care on several levels. The prevalence of alcohol problems is 7%20% or higher among outpatients,1 30%40% among emergency room patients, and 50% among patients with trauma.13 In 2006, approximately 430,000 hospital discharges in the United States were for persons with a principal (first‐listed) alcohol‐related diagnosis, and 1.7 million discharges listed at least one alcohol‐related diagnosis, representing 1.3% and 5.3% of all hospital discharges, respectively.4 Alcoholic psychosis (34.5%) and alcohol dependence syndrome (29.5%) together accounted for the majority of principal alcohol‐related diagnoses.4 Additionally, many patients hospitalized for other indications are susceptible to withdrawal symptoms due to physiological habituation to alcohol. Abrupt cessation of alcohol intake causes habituated drinkers to experience symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), which significantly increases intensity and cost of care. Trauma patients who develop AWS were found to have increased morbidity, more intensive care and ventilator days, and higher hospital costs than trauma patients without AWS.5 Unfortunately, attempts to develop predictive models to accurately forecast the likelihood of developing severe AWS in an individual case have been modestly successful at best.68

Regimens used to treat AWS have evolved over time, taking advantage of advances in the understanding of addiction neurophysiology. There is no specific ethanol receptor.9 Much of alcohol's acute effects on the central nervous system are mediated by its stimulation of the gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) system, which is neuroinhibitory.10 Chronic alcohol use leads to habituation partly by inducing configuration changes of GABA‐A receptor subunits. This renders the GABA‐A receptor less sensitive to alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines.11 Although both GABA‐A and GABA‐B receptor activation cause increased GABA neuronal output, the GABA‐A receptor is rendered relatively less sensitive by chronic exposure to alcohol. Baclofen is a pure GABA‐B receptor agonist,12 and its GABA‐B stimulatory effect is maintained even in habituated alcoholics.13, 14 The absence of cross‐tolerance between baclofen and ethanol suggests that low doses of baclofen may be helpful in the management of AWS.

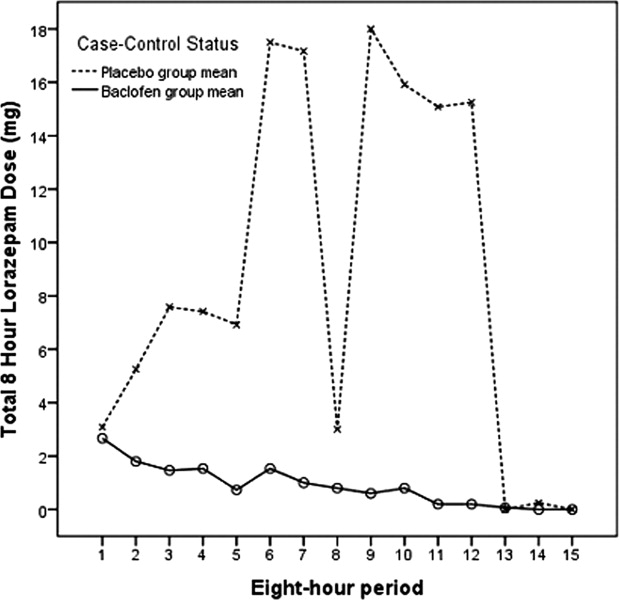

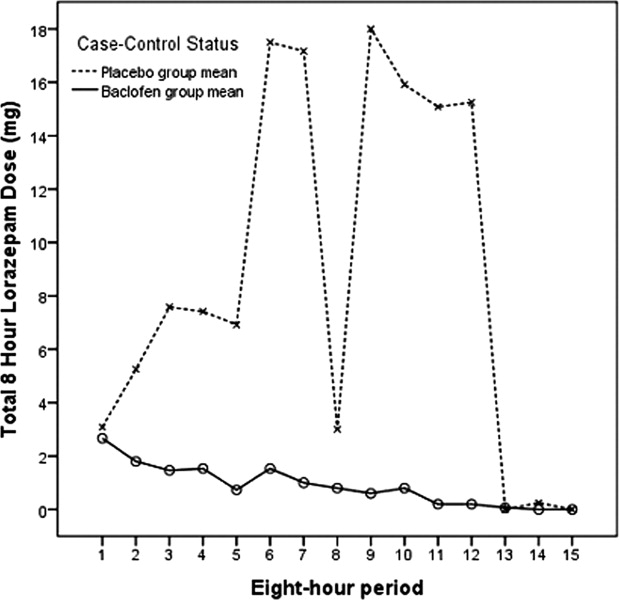

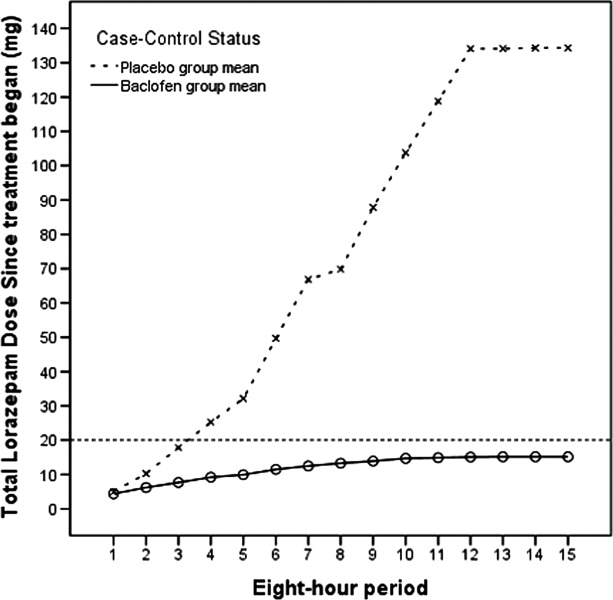

Currently, AWS is usually managed with benzodiazepines, using variable dosing depending on the severity of withdrawal symptoms. Such symptom‐triggered treatment is generally preferred over fixed‐dose regimens,15 in part because when using this method, many cases of AWS can be managed with less medication. Benzodiazepine regimens using high doses have been found to be associated with substantial morbidity and prolonged hospitalizations.16, 17

In a series of small studies, Addolorato's research team has reported decreases in AWS symptoms in association with the use of low doses of baclofen in an outpatient population,18 and has found baclofen to be associated with reduced alcohol craving in the long‐term management of alcohol dependence.11, 19, 20 Addolorato and colleagues' studies of baclofen in relieving AWS symptoms prompted our group to apply the use of baclofen in a larger group of inpatients with AWS.11, 18, 21 We conducted this study to improve understanding of the role of baclofen in the management of acute AWS in an inpatient population of subjects at risk for AWS, drawn from general hospital admissions.

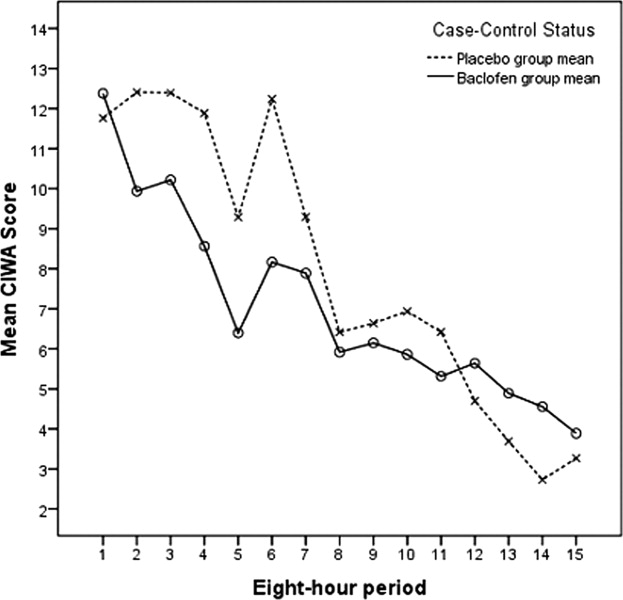

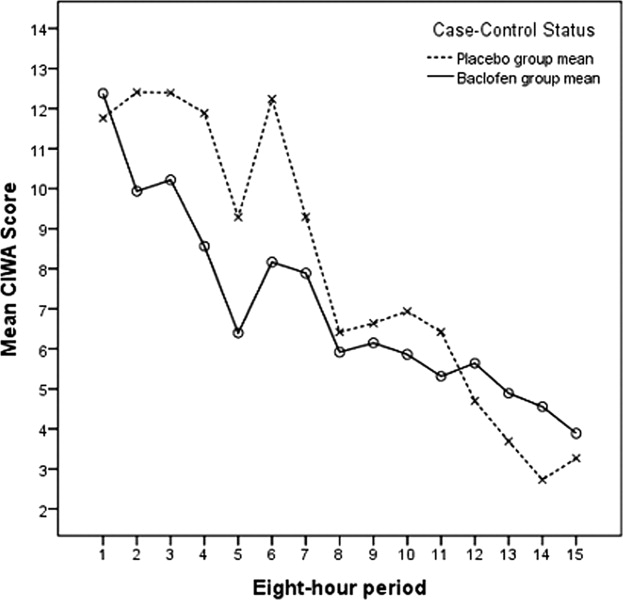

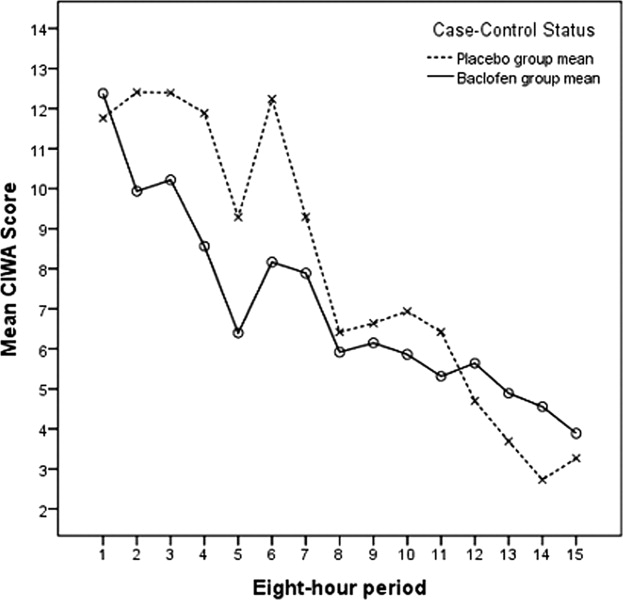

Our primary null hypothesis was that Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA‐Ar) scores in acutely withdrawing alcoholic patients are equal in baclofen‐treated and placebo‐treated subject groups. Our secondary null hypothesis was that benzodiazepine doses used to treat acutely withdrawing alcoholic patients are equal in the baclofen‐treated and placebo‐treated groups.

METHODS

The protocol for this study was approved by the Essentia Health Institutional Review Board, Duluth, Minnesota.

This was a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial. Subjects were recruited from among patients who were admitted to 1 of 2 regional general hospitals in Duluth, Minnesota (St. Mary's Medical Center or Miller‐Dwan Medical Center) and who were identified by clinical staff as being at risk for AWS. Potential subjects were not required to have an alcohol‐related condition as their primary reason for admission, but were required to have a history of AWS or of alcohol use suggestive of significant risk for AWS, and to be able to provide informed consent, as described below.

Patients were not eligible for enrollment in the study if they had other active drug dependence in addition to alcohol; were using baclofen at the time of study enrollment; were using benzodiazepines chronically at the time of study enrollment; had a known baclofen or benzodiazepine sensitivity; were unable to take oral medications; were pregnant or breast‐feeding; had a serum creatinine level 2.0; had a history of non‐alcohol withdrawal seizures; required intravenous benzodiazepines to control their AWS; or were unable to complete the consenting procedures.

Consenting and Enrollment Procedures

Patients who were identified by clinical staff as being at high risk for AWS were approached for possible enrollment in the study. Potential subjects who met other inclusion criteria were screened to assess their mental status with the Mini‐Mental Status Exam (MMSE), using methods developed for subjects with cognitive impairment.22 Potential subjects who scored 24 of a possible score of 30 or higher on the exam were considered capable of providing informed consent. Potential subjects who scored between 20 and 23 were considered to be capable of providing consent if they were able to answer 4 questions about the study (why the study is being done, what will be required of them if they participate, how long they will be in the study, and how it will be determined if they will receive the investigational drug or the placebo).

Patients who met inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Subjects were randomized only if they developed signs of AWS sufficient to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSMIV) criteria for AWS diagnosis, and reached at least a score of 11 (of a possible 67) on the CIWA‐Ar. All subjects received symptom‐triggered benzodiazepine treatment, and also were randomized to receive either baclofen (10 mg) or placebo every 8 hours (q8h) orally as inpatients for 72 hours or until discharge, whichever was shorter. Lorazepam was selected for the symptom‐triggered benzodiazepine treatment, as it has been used for managing AWS in the participating hospitals for several years. The initial research protocol called for 5 days of participation (15 doses of study drug), but we found that many subjects were discharged before the 5 days had elapsed after enrollment, and that compliance with follow‐up outpatient visits was poor. Accordingly, the protocol was amended to shorten the treatment period to 72 hours of participation (9 doses) or until discharge if prior to 72 hours, with the minimum observation period set to 72 hours.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected at the time of enrollment, both from the patient and the medical record. Demographic data (age, gender, race) were obtained, as well as data on alcohol history, including approximate duration and intensity of alcohol use, and prior experience with AWS; data on comorbid conditions and medical history; and history of beta‐blocker use. During the period of observation following randomization, data were obtained on CIWA‐Ar scores; benzodiazepine doses administered; and adverse events, including use of sedatives in addition to benzodiazepines, use of restraints, use of intensive care, and clinical complications during the AWS course.