User login

Smart-bed technology reveals insomnia, flu risk link

The study of smart-bed sleepers found that there was a statistically significant correlation between a higher number of episodes of influenza-like illnesses (ILI) per year with longer duration compared to people without insomnia.

However, more research is needed to determine causality and whether insomnia may predispose to ILI or whether ILI affects long-term sleep behavior, the researchers noted.

“Several lines of evidence make me think that it’s more likely that insomnia makes one more vulnerable to influenza through pathways that involve decreased immune function,” study investigator Gary Garcia-Molina, PhD, with Sleep Number Labs, San Jose, Calif., said in an interview.

Sleep disorders, including insomnia, can dampen immune function and an individual’s ability to fight off illness, he noted.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Smart, connected devices

Pathophysiological responses to respiratory viral infection affect sleep duration and quality in addition to breathing function. “Smart” and “connected” devices that monitor biosignals over time have shown promise for monitoring infectious disease.

In an earlier study presented at SLEEP 2021, Dr. Garcia-Molina and colleagues found that real-world biometric data obtained from a smart bed can help predict and track symptoms of COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. They showed that worsening of COVID-19 symptoms correlated with an increase in sleep duration, breathing rate, and heart rate and a decrease in sleep quality.

In the new study, the researchers evaluated vulnerability to ILI in people with insomnia.

They quantified insomnia over time using the insomnia severity index (ISI). They quantified ILI vulnerability using an established artificial intelligence model they developed that estimates the daily probability of ILI symptoms from a Sleep Number smart bed using ballistocardiograph sensors.

Smart bed data – including daily and restful sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep quality, heart rate, breathing rate and motion level – were queried from 2019 (pre-COVID) and 2021.

A total of 1,680 smart sleepers had nearly constant ISI scores over the study period, with 249 having insomnia and 1,431 not having insomnia.

Data from both 2019 and 2021 show that smart sleepers with insomnia had significantly more and longer ILI episodes per year, compared with peers without insomnia.

For 2019, individuals without insomnia had 1.2 ILI episodes on average, which was significantly less (P < .01) than individuals with insomnia, at 1.5 episodes. The average ILI episode duration for those without insomnia was 4.3 days, which was significantly lower (P < .01) in those with insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The data for 2021 show similar results, with the no-insomnia group having significantly fewer (P < .01) ILI episodes (about 1.2), compared with the insomnia group (about 1.5).

The average ILI episode duration for the no-insomnia group was 5 days, which was significantly less (P < .01) than the insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The researchers said their study adds to other data on the relationship between sleep and overall health and well-being. It also highlights the potential health risk of insomnia and the importance of identifying and treating sleep disorders.

“Sleep has such a profound influence on health and wellness and the ability to capture these data unobtrusively in such an easy way and with such a large number of participants paves the way to investigate different aspects of health and disease,” Dr. Garcia-Molina said.

Rich data source

In a comment, Adam C. Powell, PhD, president of Payer+Provider Syndicate, a management advisory and operational consulting firm, said “smart beds provide a new data source for passively monitoring the health of individuals.”

“Unlike active monitoring methods requiring self-report, passive monitoring enables data to be captured without an individual taking any action. This data can be potentially integrated with data from other sources, such as pedometers, smart scales, and smart blood pressure cuffs, to gain a more holistic understanding of how an individual’s activities and behaviors impact their well-being,” said Dr. Powell, who wasn’t involved in the study.

There are some methodological limitations to the study, he noted.

“While the dependent variables examined were the duration and presence of episodes of influenza-like illness, they did not directly measure these episodes. Instead, they calculated the daily probability of influenza-like illness symptoms using a model that received input from the ballistocardiograph sensors in the smart beds,” Dr. Powell noted.

“The model used to calculate daily probability of influenza-like illness was created by examining associations between individuals’ smart-bed sensor data and population-level trends in influenza-like illness reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” he explained.

Nonetheless, the findings are “consistent with the literature. It has been established by other researchers that impaired sleep is associated with greater risk of influenza, as well as other illnesses,” Dr. Powell said.

Funding for the study was provided by Sleep Number. Dr. Garcia-Molina and five coauthors are employed by Sleep Number. Dr. Powell reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of smart-bed sleepers found that there was a statistically significant correlation between a higher number of episodes of influenza-like illnesses (ILI) per year with longer duration compared to people without insomnia.

However, more research is needed to determine causality and whether insomnia may predispose to ILI or whether ILI affects long-term sleep behavior, the researchers noted.

“Several lines of evidence make me think that it’s more likely that insomnia makes one more vulnerable to influenza through pathways that involve decreased immune function,” study investigator Gary Garcia-Molina, PhD, with Sleep Number Labs, San Jose, Calif., said in an interview.

Sleep disorders, including insomnia, can dampen immune function and an individual’s ability to fight off illness, he noted.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Smart, connected devices

Pathophysiological responses to respiratory viral infection affect sleep duration and quality in addition to breathing function. “Smart” and “connected” devices that monitor biosignals over time have shown promise for monitoring infectious disease.

In an earlier study presented at SLEEP 2021, Dr. Garcia-Molina and colleagues found that real-world biometric data obtained from a smart bed can help predict and track symptoms of COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. They showed that worsening of COVID-19 symptoms correlated with an increase in sleep duration, breathing rate, and heart rate and a decrease in sleep quality.

In the new study, the researchers evaluated vulnerability to ILI in people with insomnia.

They quantified insomnia over time using the insomnia severity index (ISI). They quantified ILI vulnerability using an established artificial intelligence model they developed that estimates the daily probability of ILI symptoms from a Sleep Number smart bed using ballistocardiograph sensors.

Smart bed data – including daily and restful sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep quality, heart rate, breathing rate and motion level – were queried from 2019 (pre-COVID) and 2021.

A total of 1,680 smart sleepers had nearly constant ISI scores over the study period, with 249 having insomnia and 1,431 not having insomnia.

Data from both 2019 and 2021 show that smart sleepers with insomnia had significantly more and longer ILI episodes per year, compared with peers without insomnia.

For 2019, individuals without insomnia had 1.2 ILI episodes on average, which was significantly less (P < .01) than individuals with insomnia, at 1.5 episodes. The average ILI episode duration for those without insomnia was 4.3 days, which was significantly lower (P < .01) in those with insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The data for 2021 show similar results, with the no-insomnia group having significantly fewer (P < .01) ILI episodes (about 1.2), compared with the insomnia group (about 1.5).

The average ILI episode duration for the no-insomnia group was 5 days, which was significantly less (P < .01) than the insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The researchers said their study adds to other data on the relationship between sleep and overall health and well-being. It also highlights the potential health risk of insomnia and the importance of identifying and treating sleep disorders.

“Sleep has such a profound influence on health and wellness and the ability to capture these data unobtrusively in such an easy way and with such a large number of participants paves the way to investigate different aspects of health and disease,” Dr. Garcia-Molina said.

Rich data source

In a comment, Adam C. Powell, PhD, president of Payer+Provider Syndicate, a management advisory and operational consulting firm, said “smart beds provide a new data source for passively monitoring the health of individuals.”

“Unlike active monitoring methods requiring self-report, passive monitoring enables data to be captured without an individual taking any action. This data can be potentially integrated with data from other sources, such as pedometers, smart scales, and smart blood pressure cuffs, to gain a more holistic understanding of how an individual’s activities and behaviors impact their well-being,” said Dr. Powell, who wasn’t involved in the study.

There are some methodological limitations to the study, he noted.

“While the dependent variables examined were the duration and presence of episodes of influenza-like illness, they did not directly measure these episodes. Instead, they calculated the daily probability of influenza-like illness symptoms using a model that received input from the ballistocardiograph sensors in the smart beds,” Dr. Powell noted.

“The model used to calculate daily probability of influenza-like illness was created by examining associations between individuals’ smart-bed sensor data and population-level trends in influenza-like illness reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” he explained.

Nonetheless, the findings are “consistent with the literature. It has been established by other researchers that impaired sleep is associated with greater risk of influenza, as well as other illnesses,” Dr. Powell said.

Funding for the study was provided by Sleep Number. Dr. Garcia-Molina and five coauthors are employed by Sleep Number. Dr. Powell reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study of smart-bed sleepers found that there was a statistically significant correlation between a higher number of episodes of influenza-like illnesses (ILI) per year with longer duration compared to people without insomnia.

However, more research is needed to determine causality and whether insomnia may predispose to ILI or whether ILI affects long-term sleep behavior, the researchers noted.

“Several lines of evidence make me think that it’s more likely that insomnia makes one more vulnerable to influenza through pathways that involve decreased immune function,” study investigator Gary Garcia-Molina, PhD, with Sleep Number Labs, San Jose, Calif., said in an interview.

Sleep disorders, including insomnia, can dampen immune function and an individual’s ability to fight off illness, he noted.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Smart, connected devices

Pathophysiological responses to respiratory viral infection affect sleep duration and quality in addition to breathing function. “Smart” and “connected” devices that monitor biosignals over time have shown promise for monitoring infectious disease.

In an earlier study presented at SLEEP 2021, Dr. Garcia-Molina and colleagues found that real-world biometric data obtained from a smart bed can help predict and track symptoms of COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. They showed that worsening of COVID-19 symptoms correlated with an increase in sleep duration, breathing rate, and heart rate and a decrease in sleep quality.

In the new study, the researchers evaluated vulnerability to ILI in people with insomnia.

They quantified insomnia over time using the insomnia severity index (ISI). They quantified ILI vulnerability using an established artificial intelligence model they developed that estimates the daily probability of ILI symptoms from a Sleep Number smart bed using ballistocardiograph sensors.

Smart bed data – including daily and restful sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep quality, heart rate, breathing rate and motion level – were queried from 2019 (pre-COVID) and 2021.

A total of 1,680 smart sleepers had nearly constant ISI scores over the study period, with 249 having insomnia and 1,431 not having insomnia.

Data from both 2019 and 2021 show that smart sleepers with insomnia had significantly more and longer ILI episodes per year, compared with peers without insomnia.

For 2019, individuals without insomnia had 1.2 ILI episodes on average, which was significantly less (P < .01) than individuals with insomnia, at 1.5 episodes. The average ILI episode duration for those without insomnia was 4.3 days, which was significantly lower (P < .01) in those with insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The data for 2021 show similar results, with the no-insomnia group having significantly fewer (P < .01) ILI episodes (about 1.2), compared with the insomnia group (about 1.5).

The average ILI episode duration for the no-insomnia group was 5 days, which was significantly less (P < .01) than the insomnia group, at 6.1 days.

The researchers said their study adds to other data on the relationship between sleep and overall health and well-being. It also highlights the potential health risk of insomnia and the importance of identifying and treating sleep disorders.

“Sleep has such a profound influence on health and wellness and the ability to capture these data unobtrusively in such an easy way and with such a large number of participants paves the way to investigate different aspects of health and disease,” Dr. Garcia-Molina said.

Rich data source

In a comment, Adam C. Powell, PhD, president of Payer+Provider Syndicate, a management advisory and operational consulting firm, said “smart beds provide a new data source for passively monitoring the health of individuals.”

“Unlike active monitoring methods requiring self-report, passive monitoring enables data to be captured without an individual taking any action. This data can be potentially integrated with data from other sources, such as pedometers, smart scales, and smart blood pressure cuffs, to gain a more holistic understanding of how an individual’s activities and behaviors impact their well-being,” said Dr. Powell, who wasn’t involved in the study.

There are some methodological limitations to the study, he noted.

“While the dependent variables examined were the duration and presence of episodes of influenza-like illness, they did not directly measure these episodes. Instead, they calculated the daily probability of influenza-like illness symptoms using a model that received input from the ballistocardiograph sensors in the smart beds,” Dr. Powell noted.

“The model used to calculate daily probability of influenza-like illness was created by examining associations between individuals’ smart-bed sensor data and population-level trends in influenza-like illness reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” he explained.

Nonetheless, the findings are “consistent with the literature. It has been established by other researchers that impaired sleep is associated with greater risk of influenza, as well as other illnesses,” Dr. Powell said.

Funding for the study was provided by Sleep Number. Dr. Garcia-Molina and five coauthors are employed by Sleep Number. Dr. Powell reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SLEEP 2023

Investing in the future of GI

This leads to promising investigators walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support. Investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit.

Decades of research have revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field – clinicians and researchers alike – have benefited from discoveries made by dedicated investigators, past and present.

Creative young researchers are poised to make groundbreaking discoveries that will shape the future of gastroenterology. Unfortunately, declining government funding for biomedical research puts this potential in jeopardy. We’re at risk of losing an entire generation of researchers if we don’t act now.

To fill this gap, the AGA Research Foundation invites you to support young investigators’ research careers, allowing them to make discoveries that could ultimately improve patient care and even cure diseases.

“We are at the threshold of key research advances that will cure digestive diseases. We have the manpower, we have trained the people, now we need to have the security that they can stay in research and advance these cures,” said Kim Elaine Barrett, PhD, AGAF, AGA legacy society donor and AGA governing board member.

By joining others in supporting the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that young researchers have opportunities to continue their life-saving work.

Learn more or make a contribution at www.foundation.gastro.org.

This leads to promising investigators walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support. Investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit.

Decades of research have revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field – clinicians and researchers alike – have benefited from discoveries made by dedicated investigators, past and present.

Creative young researchers are poised to make groundbreaking discoveries that will shape the future of gastroenterology. Unfortunately, declining government funding for biomedical research puts this potential in jeopardy. We’re at risk of losing an entire generation of researchers if we don’t act now.

To fill this gap, the AGA Research Foundation invites you to support young investigators’ research careers, allowing them to make discoveries that could ultimately improve patient care and even cure diseases.

“We are at the threshold of key research advances that will cure digestive diseases. We have the manpower, we have trained the people, now we need to have the security that they can stay in research and advance these cures,” said Kim Elaine Barrett, PhD, AGAF, AGA legacy society donor and AGA governing board member.

By joining others in supporting the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that young researchers have opportunities to continue their life-saving work.

Learn more or make a contribution at www.foundation.gastro.org.

This leads to promising investigators walking away from GI research frustrated by a lack of support. Investigators in the early stages of their careers are particularly hard hit.

Decades of research have revolutionized the care of many digestive disease patients. These patients, as well as everyone in the GI field – clinicians and researchers alike – have benefited from discoveries made by dedicated investigators, past and present.

Creative young researchers are poised to make groundbreaking discoveries that will shape the future of gastroenterology. Unfortunately, declining government funding for biomedical research puts this potential in jeopardy. We’re at risk of losing an entire generation of researchers if we don’t act now.

To fill this gap, the AGA Research Foundation invites you to support young investigators’ research careers, allowing them to make discoveries that could ultimately improve patient care and even cure diseases.

“We are at the threshold of key research advances that will cure digestive diseases. We have the manpower, we have trained the people, now we need to have the security that they can stay in research and advance these cures,” said Kim Elaine Barrett, PhD, AGAF, AGA legacy society donor and AGA governing board member.

By joining others in supporting the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that young researchers have opportunities to continue their life-saving work.

Learn more or make a contribution at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Long-term Remission of Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa Syndrome

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

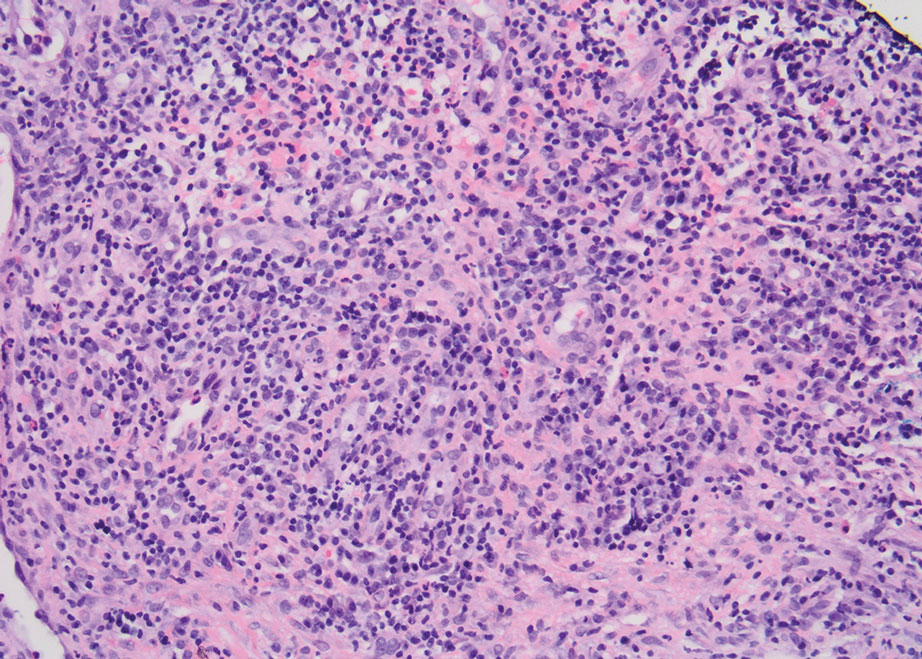

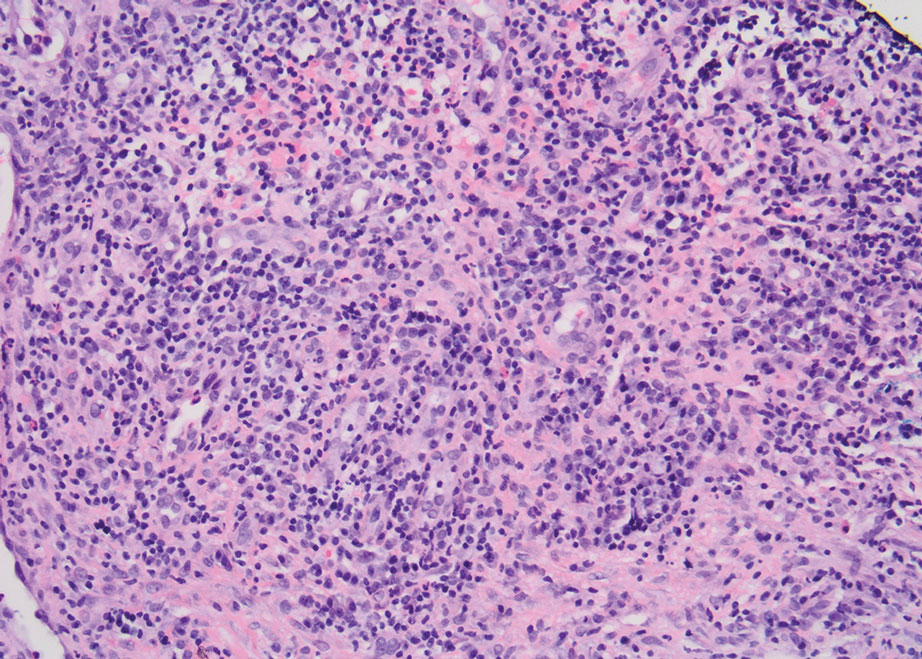

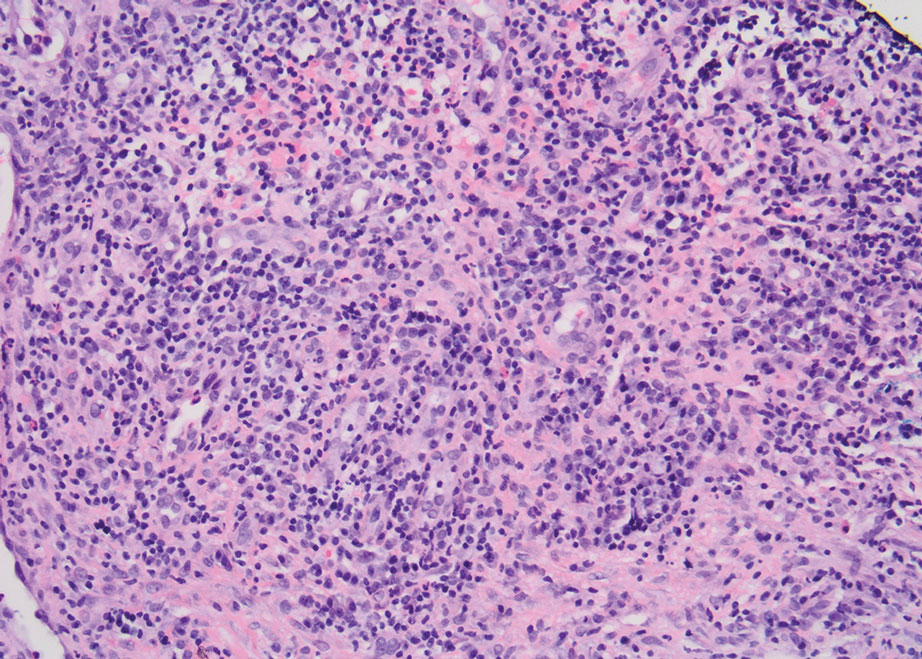

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

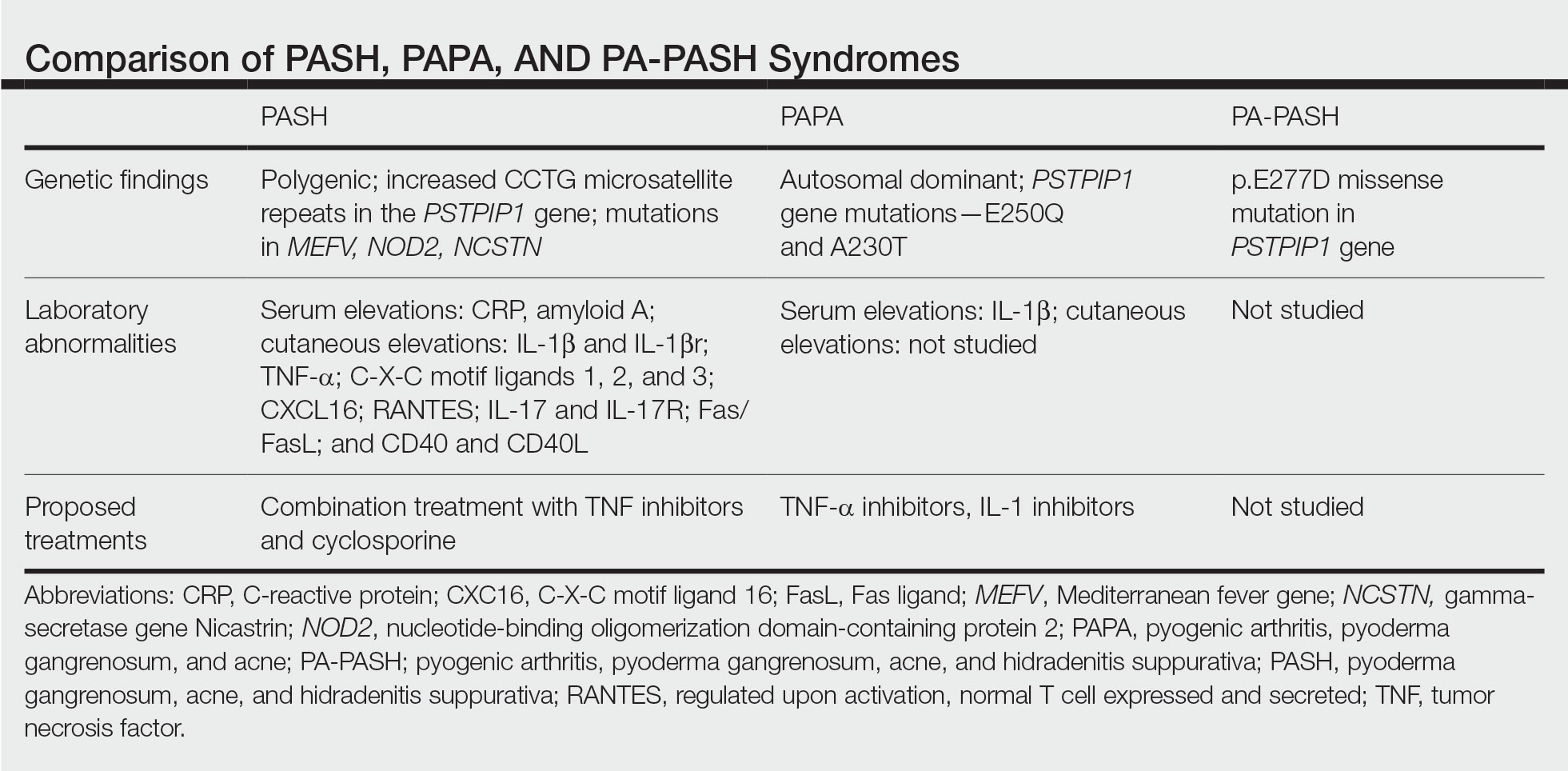

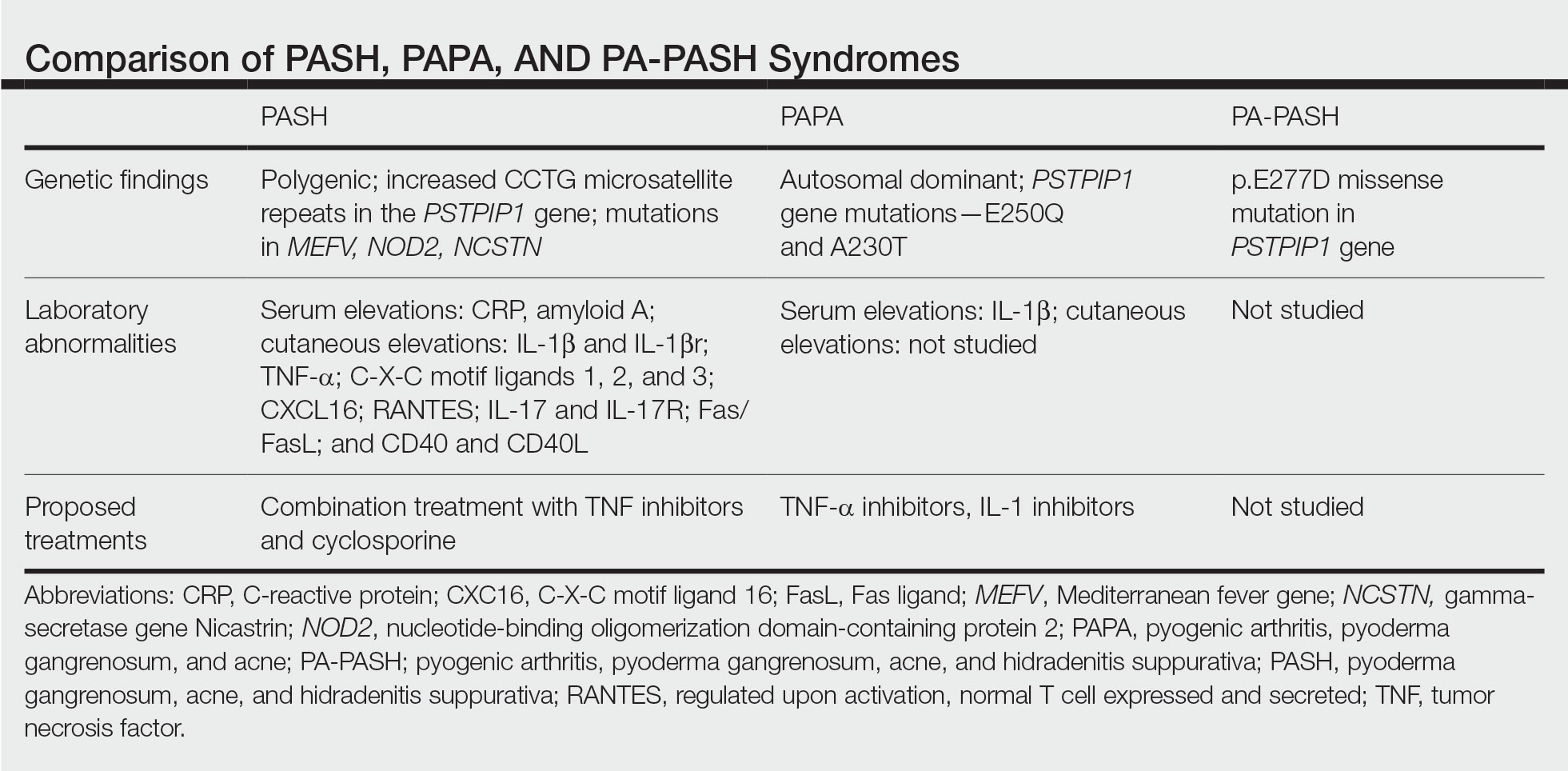

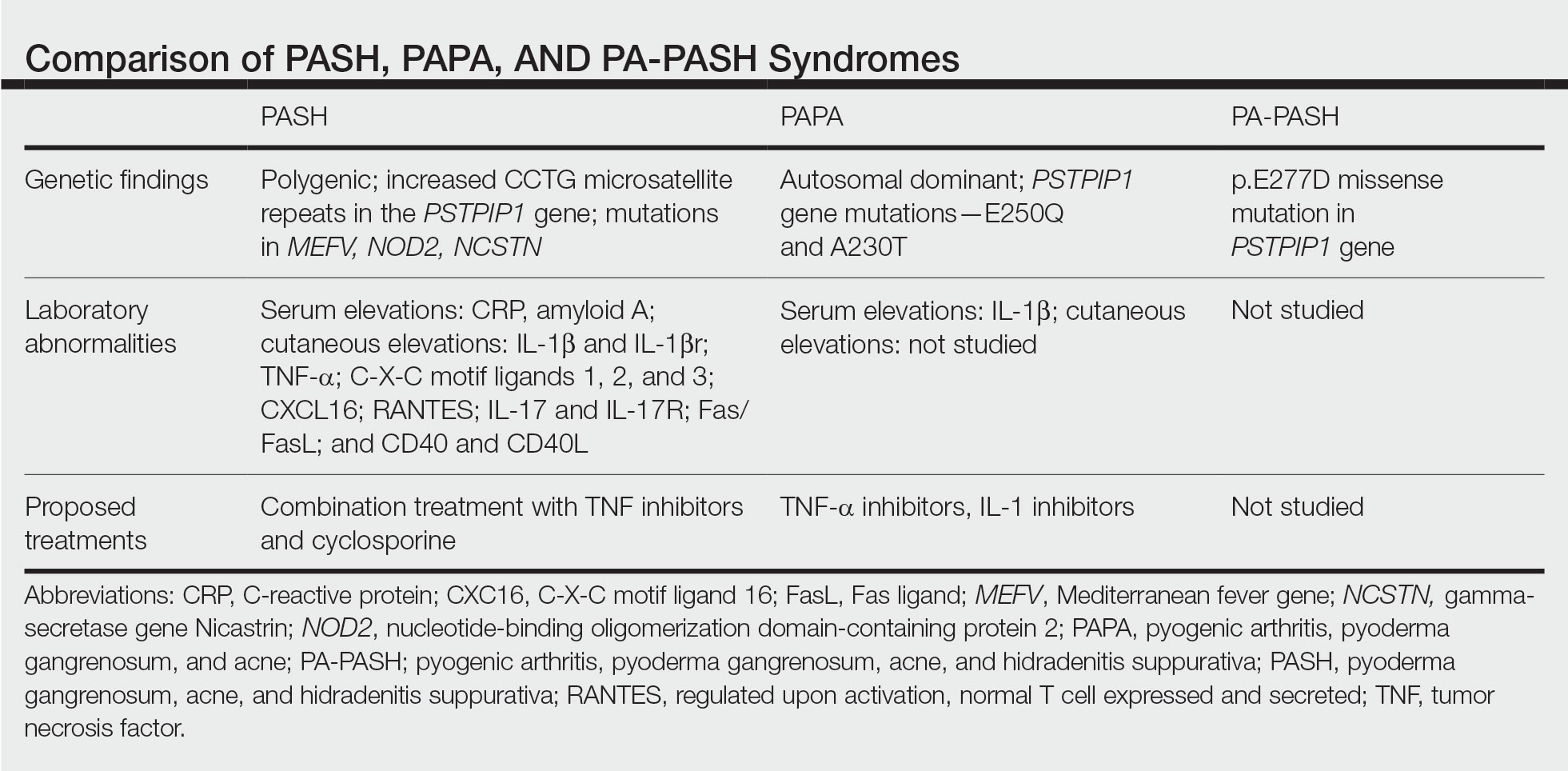

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

Practice Points

- Despite phenotypic similarities among pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PASH) syndrome; pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne syndrome; and pyogenic arthritis–PASH syndrome, there are genotypic differences that contribute to unique inflammatory cytokine patterns and the need for distinct pharmacologic considerations within each entity.

- When formulating therapeutic regimens for patients with PASH syndrome, it is essential for dermatologists to consider the likelihood of hyperactivity in multiple pathways of the innate immune system and utilize a combination of multimodal antiinflammatory therapies.

Trailblazer for women in gastroenterology, Dr. Barbara H. Jung takes over as AGA president

She currently serves as the first woman Robert G. Petersdorf professor and chair of internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and is the fourth woman to lead the American Gastroenterological Association as its president.

Dr. Jung is an international expert in the field of transforming growth factor–beta superfamily signaling in colon cancer and has made significant contributions at AGA prior to becoming president, most recently as a member of the finance and operations committee, chair-elect of the audit committee and vice chair of the AGA Research Foundation.

Born in Portland, Ore., and raised in Munich, Germany, Dr. Jung’s parents provided unconditional support for her career choice in medicine and nurtured her leadership skills throughout her childhood.

Her academic career began at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich followed by postdoctoral studies in colon cancer at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in San Diego and eventually culminating in an internal medicine residency at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Jung joined the AGA Governing Board in June 2021 as vice president and served as president-elect prior to assuming the top leadership role. Over her time as an AGA member (which started during fellowship), Dr. Jung has also served on the AGA Audit Committee, AGA Registry Research and Publications Committee, AGA Research Policy Committee, and AGA Innovation and Technology Task Force. In 2017, she co-organized the AGA Academic Skills Workshop to train the next generation of gastroenterologists.

She currently serves as the first woman Robert G. Petersdorf professor and chair of internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and is the fourth woman to lead the American Gastroenterological Association as its president.

Dr. Jung is an international expert in the field of transforming growth factor–beta superfamily signaling in colon cancer and has made significant contributions at AGA prior to becoming president, most recently as a member of the finance and operations committee, chair-elect of the audit committee and vice chair of the AGA Research Foundation.

Born in Portland, Ore., and raised in Munich, Germany, Dr. Jung’s parents provided unconditional support for her career choice in medicine and nurtured her leadership skills throughout her childhood.

Her academic career began at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich followed by postdoctoral studies in colon cancer at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in San Diego and eventually culminating in an internal medicine residency at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Jung joined the AGA Governing Board in June 2021 as vice president and served as president-elect prior to assuming the top leadership role. Over her time as an AGA member (which started during fellowship), Dr. Jung has also served on the AGA Audit Committee, AGA Registry Research and Publications Committee, AGA Research Policy Committee, and AGA Innovation and Technology Task Force. In 2017, she co-organized the AGA Academic Skills Workshop to train the next generation of gastroenterologists.

She currently serves as the first woman Robert G. Petersdorf professor and chair of internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and is the fourth woman to lead the American Gastroenterological Association as its president.

Dr. Jung is an international expert in the field of transforming growth factor–beta superfamily signaling in colon cancer and has made significant contributions at AGA prior to becoming president, most recently as a member of the finance and operations committee, chair-elect of the audit committee and vice chair of the AGA Research Foundation.

Born in Portland, Ore., and raised in Munich, Germany, Dr. Jung’s parents provided unconditional support for her career choice in medicine and nurtured her leadership skills throughout her childhood.

Her academic career began at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich followed by postdoctoral studies in colon cancer at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in San Diego and eventually culminating in an internal medicine residency at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Jung joined the AGA Governing Board in June 2021 as vice president and served as president-elect prior to assuming the top leadership role. Over her time as an AGA member (which started during fellowship), Dr. Jung has also served on the AGA Audit Committee, AGA Registry Research and Publications Committee, AGA Research Policy Committee, and AGA Innovation and Technology Task Force. In 2017, she co-organized the AGA Academic Skills Workshop to train the next generation of gastroenterologists.

What is new in hepatology in 2023?

CHICAGO – Two landmark phase 2 trials of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, semaglutide, Food and Drug Administration–approved for type 2 diabetes or obesity, demonstrated improvements in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) activity and resolution in stage 2 or 3 fibrosis (F2/F3), but not F4 fibrosis.1,2 The first randomized trial to compare the efficacy and safety of bariatric surgery with lifestyle intervention plus best medical care for histologically confirmed NASH demonstrated the superiority of bariatric surgery.3

There has been a paradigm shift in risk stratification of cirrhosis and targets for prevention and treatment of decompensation. A newer term, advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), represents a shift away from needing a histologic or radiologic diagnosis of cirrhosis while reduction in portal pressure is a therapeutic goal. Evidence supports noninvasive liver stiffness measurement (LSM) using transient elastography to identify those with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) (e.g., hepatic venous pressure gradient ≥ 10 mm Hg) who may benefit from therapy to lower portal pressure. Accordingly, based on landmark studies, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends early utilization of nonselective beta-blocker therapy, with carvedilol as a preferred agent, in CSPH to decrease the risk of decompensation and mortality.4

The definition of hepatorenal syndrome has also substantially evolved.5 Terminology now acknowledges significant renal impairment at lower creatinine levels than previously used and recognizes the contribution of chronic kidney disease. The FDA approved terlipressin, a potent vasoconstrictor, for the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome with acute kidney injury (HRS-AKI, formerly HRS-Type I).