User login

Ticagrelor may reduce brain lesions after carotid stenting

MUNICH – secondary endpoint results of the PRECISE-MRI trial suggest.

More than 200 patients with carotid artery stenosis underwent MRI and were randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel before undergoing CAS. They then had two follow-up MRIs to assess the presence of emergent ischemic lesions.

Although the trial, which was stopped early, failed to show a difference between the two treatments in the primary endpoint – occurrence of at least one ischemic lesion – it did show that ticagrelor was associated with significant reductions in secondary endpoints including the total number and total volume of new lesions.

There were also significantly fewer cases of a composite of adverse clinical events with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, but no difference in rates of hemorrhagic bleeds.

The research was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference .

Highlighting the failure of the trial to meet its primary endpoint, study presenter Leo Bonati, MD, head of the Stroke Center, Rena Rheinfelden, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), pointed out that the proportion of patients with one or more ischemic brain lesions was “much higher than expected.”

Based on the secondary outcomes, the study nevertheless indicates that, “compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor reduces the total burden of ischemic brain lesions occurring during CAS,” he said.

Ticagrelor is therefore a “safe alternative to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin to cover carotid artery stent procedures.”

Dr. Bonati cautioned, however, that the findings are preliminary.

‘Promising’ results

Session cochair Else Charlotte Sandset, MD, PhD, a consultant neurologist in the stroke unit, department of neurology, Oslo University Hospital, called the results “interesting” and “promising.”

She said in an interview that they “also provide us with an additional option” in the management of patients undergoing CAS.

Dr. Sandset suggested that “it may have been a little bit hard to prove the primary endpoint” chosen for the trial, but believes that the secondary endpoint results “are very interesting.”

“Of course, we would need more data and further trials to provide some reassurance that we can use ticagrelor in this fashion,” she said.

Major complication

Dr. Bonati began by noting that the major procedural complication of CAS is embolic stroke, but this may be prevented with optimized antiplatelet therapy.

Previous studies have shown that ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in reducing rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Adding the drug to aspirin is also superior to aspirin alone in preventing recurrent stroke in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack, Dr. Bonati said.

To examine whether ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in preventing ischemic brain lesions during CAS, the team conducted a randomized, open, active-controlled trial.

They recruited patients with ≥ 50% symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis undergoing CAS in line with local guidelines and performed a baseline MRI scan and clinical examination.

The patients were then randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel plus aspirin 1-3 days before undergoing CAS. A second MRI and clinical examination, as well as an ultrasound scan, was performed at 1 to 3 days post-CAS, with a third set of examinations performed at 28-32 days after the procedure.

The study included 14 sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Enrollment was stopped after 209 of the originally planned 370 patients, “due to slow recruitment and a lack of further funding,” Dr. Bonati said.

Of those, 207 patients were included in the intention-to-treat safety analysis, and 172 in the per-protocol efficacy analysis.

The mean age of the patients was 69.0-69.5 years in the two treatment groups, and 67%-71% were male. Dr. Bonati noted that 52%-55% of the patients had symptomatic stenosis, and that in 83%-88% the stenosis was severe.

The majority (79%-82%) of patients had hypertension, alongside hypercholesterolemia, at 76% in both treatment groups.

Dr. Bonati showed that there was no significant difference in the primary efficacy outcome of the presence of at least new ischemic brain lesion on the second or third MRI, at 74.7% for patients given ticagrelor versus 79.8% with clopidogrel, or a relative risk of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.10; P = .43).

However, there was a significant reduction in the number of new ischemic lesions, at a median of 2 (interquartile range, 0.5-5.5) with ticagrelor versus 3 with clopidogrel (IQR, 1-8), or an exponential beta value of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.42-0.95; P = .027).

Ticagrelor was also associated with a significant reduction in the total volume of lesions, at a median of 66 mcL (IQR, 2.5-2.19) versus 91 mcL (IQR, 25-394) for clopidogrel, or an exponential beta value of 0.30 (95% CI, 0.10-0.92; P = .030).

Patients assigned to ticagrelor also had a significantly lower rate of the primary clinical safety outcome, a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, major bleeding, or cardiovascular death, at 2.9% versus 7.8% (relative risk, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.08-1.20). This was driven by a reduction in rates of post-CAS stroke.

Dr. Bonati noted that there was no significant difference in the presence of at least one hemorrhagic lesion after CAS, at 42.7% with ticagrelor and 47.6% in the clopidogrel group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.63-1.26).

There was also a similar rate of microbleeds between the two treatment groups, at 36.6% in patients given ticagrelor and 47.6% in those assigned to clopidogrel.

The study was investigator initiated and funded by an unrestricted research grant from AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MUNICH – secondary endpoint results of the PRECISE-MRI trial suggest.

More than 200 patients with carotid artery stenosis underwent MRI and were randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel before undergoing CAS. They then had two follow-up MRIs to assess the presence of emergent ischemic lesions.

Although the trial, which was stopped early, failed to show a difference between the two treatments in the primary endpoint – occurrence of at least one ischemic lesion – it did show that ticagrelor was associated with significant reductions in secondary endpoints including the total number and total volume of new lesions.

There were also significantly fewer cases of a composite of adverse clinical events with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, but no difference in rates of hemorrhagic bleeds.

The research was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference .

Highlighting the failure of the trial to meet its primary endpoint, study presenter Leo Bonati, MD, head of the Stroke Center, Rena Rheinfelden, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), pointed out that the proportion of patients with one or more ischemic brain lesions was “much higher than expected.”

Based on the secondary outcomes, the study nevertheless indicates that, “compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor reduces the total burden of ischemic brain lesions occurring during CAS,” he said.

Ticagrelor is therefore a “safe alternative to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin to cover carotid artery stent procedures.”

Dr. Bonati cautioned, however, that the findings are preliminary.

‘Promising’ results

Session cochair Else Charlotte Sandset, MD, PhD, a consultant neurologist in the stroke unit, department of neurology, Oslo University Hospital, called the results “interesting” and “promising.”

She said in an interview that they “also provide us with an additional option” in the management of patients undergoing CAS.

Dr. Sandset suggested that “it may have been a little bit hard to prove the primary endpoint” chosen for the trial, but believes that the secondary endpoint results “are very interesting.”

“Of course, we would need more data and further trials to provide some reassurance that we can use ticagrelor in this fashion,” she said.

Major complication

Dr. Bonati began by noting that the major procedural complication of CAS is embolic stroke, but this may be prevented with optimized antiplatelet therapy.

Previous studies have shown that ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in reducing rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Adding the drug to aspirin is also superior to aspirin alone in preventing recurrent stroke in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack, Dr. Bonati said.

To examine whether ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in preventing ischemic brain lesions during CAS, the team conducted a randomized, open, active-controlled trial.

They recruited patients with ≥ 50% symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis undergoing CAS in line with local guidelines and performed a baseline MRI scan and clinical examination.

The patients were then randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel plus aspirin 1-3 days before undergoing CAS. A second MRI and clinical examination, as well as an ultrasound scan, was performed at 1 to 3 days post-CAS, with a third set of examinations performed at 28-32 days after the procedure.

The study included 14 sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Enrollment was stopped after 209 of the originally planned 370 patients, “due to slow recruitment and a lack of further funding,” Dr. Bonati said.

Of those, 207 patients were included in the intention-to-treat safety analysis, and 172 in the per-protocol efficacy analysis.

The mean age of the patients was 69.0-69.5 years in the two treatment groups, and 67%-71% were male. Dr. Bonati noted that 52%-55% of the patients had symptomatic stenosis, and that in 83%-88% the stenosis was severe.

The majority (79%-82%) of patients had hypertension, alongside hypercholesterolemia, at 76% in both treatment groups.

Dr. Bonati showed that there was no significant difference in the primary efficacy outcome of the presence of at least new ischemic brain lesion on the second or third MRI, at 74.7% for patients given ticagrelor versus 79.8% with clopidogrel, or a relative risk of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.10; P = .43).

However, there was a significant reduction in the number of new ischemic lesions, at a median of 2 (interquartile range, 0.5-5.5) with ticagrelor versus 3 with clopidogrel (IQR, 1-8), or an exponential beta value of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.42-0.95; P = .027).

Ticagrelor was also associated with a significant reduction in the total volume of lesions, at a median of 66 mcL (IQR, 2.5-2.19) versus 91 mcL (IQR, 25-394) for clopidogrel, or an exponential beta value of 0.30 (95% CI, 0.10-0.92; P = .030).

Patients assigned to ticagrelor also had a significantly lower rate of the primary clinical safety outcome, a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, major bleeding, or cardiovascular death, at 2.9% versus 7.8% (relative risk, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.08-1.20). This was driven by a reduction in rates of post-CAS stroke.

Dr. Bonati noted that there was no significant difference in the presence of at least one hemorrhagic lesion after CAS, at 42.7% with ticagrelor and 47.6% in the clopidogrel group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.63-1.26).

There was also a similar rate of microbleeds between the two treatment groups, at 36.6% in patients given ticagrelor and 47.6% in those assigned to clopidogrel.

The study was investigator initiated and funded by an unrestricted research grant from AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MUNICH – secondary endpoint results of the PRECISE-MRI trial suggest.

More than 200 patients with carotid artery stenosis underwent MRI and were randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel before undergoing CAS. They then had two follow-up MRIs to assess the presence of emergent ischemic lesions.

Although the trial, which was stopped early, failed to show a difference between the two treatments in the primary endpoint – occurrence of at least one ischemic lesion – it did show that ticagrelor was associated with significant reductions in secondary endpoints including the total number and total volume of new lesions.

There were also significantly fewer cases of a composite of adverse clinical events with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel, but no difference in rates of hemorrhagic bleeds.

The research was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference .

Highlighting the failure of the trial to meet its primary endpoint, study presenter Leo Bonati, MD, head of the Stroke Center, Rena Rheinfelden, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), pointed out that the proportion of patients with one or more ischemic brain lesions was “much higher than expected.”

Based on the secondary outcomes, the study nevertheless indicates that, “compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor reduces the total burden of ischemic brain lesions occurring during CAS,” he said.

Ticagrelor is therefore a “safe alternative to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin to cover carotid artery stent procedures.”

Dr. Bonati cautioned, however, that the findings are preliminary.

‘Promising’ results

Session cochair Else Charlotte Sandset, MD, PhD, a consultant neurologist in the stroke unit, department of neurology, Oslo University Hospital, called the results “interesting” and “promising.”

She said in an interview that they “also provide us with an additional option” in the management of patients undergoing CAS.

Dr. Sandset suggested that “it may have been a little bit hard to prove the primary endpoint” chosen for the trial, but believes that the secondary endpoint results “are very interesting.”

“Of course, we would need more data and further trials to provide some reassurance that we can use ticagrelor in this fashion,” she said.

Major complication

Dr. Bonati began by noting that the major procedural complication of CAS is embolic stroke, but this may be prevented with optimized antiplatelet therapy.

Previous studies have shown that ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in reducing rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Adding the drug to aspirin is also superior to aspirin alone in preventing recurrent stroke in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack, Dr. Bonati said.

To examine whether ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel as an add-on to aspirin in preventing ischemic brain lesions during CAS, the team conducted a randomized, open, active-controlled trial.

They recruited patients with ≥ 50% symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis undergoing CAS in line with local guidelines and performed a baseline MRI scan and clinical examination.

The patients were then randomized to ticagrelor or clopidogrel plus aspirin 1-3 days before undergoing CAS. A second MRI and clinical examination, as well as an ultrasound scan, was performed at 1 to 3 days post-CAS, with a third set of examinations performed at 28-32 days after the procedure.

The study included 14 sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Enrollment was stopped after 209 of the originally planned 370 patients, “due to slow recruitment and a lack of further funding,” Dr. Bonati said.

Of those, 207 patients were included in the intention-to-treat safety analysis, and 172 in the per-protocol efficacy analysis.

The mean age of the patients was 69.0-69.5 years in the two treatment groups, and 67%-71% were male. Dr. Bonati noted that 52%-55% of the patients had symptomatic stenosis, and that in 83%-88% the stenosis was severe.

The majority (79%-82%) of patients had hypertension, alongside hypercholesterolemia, at 76% in both treatment groups.

Dr. Bonati showed that there was no significant difference in the primary efficacy outcome of the presence of at least new ischemic brain lesion on the second or third MRI, at 74.7% for patients given ticagrelor versus 79.8% with clopidogrel, or a relative risk of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.10; P = .43).

However, there was a significant reduction in the number of new ischemic lesions, at a median of 2 (interquartile range, 0.5-5.5) with ticagrelor versus 3 with clopidogrel (IQR, 1-8), or an exponential beta value of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.42-0.95; P = .027).

Ticagrelor was also associated with a significant reduction in the total volume of lesions, at a median of 66 mcL (IQR, 2.5-2.19) versus 91 mcL (IQR, 25-394) for clopidogrel, or an exponential beta value of 0.30 (95% CI, 0.10-0.92; P = .030).

Patients assigned to ticagrelor also had a significantly lower rate of the primary clinical safety outcome, a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, major bleeding, or cardiovascular death, at 2.9% versus 7.8% (relative risk, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.08-1.20). This was driven by a reduction in rates of post-CAS stroke.

Dr. Bonati noted that there was no significant difference in the presence of at least one hemorrhagic lesion after CAS, at 42.7% with ticagrelor and 47.6% in the clopidogrel group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.63-1.26).

There was also a similar rate of microbleeds between the two treatment groups, at 36.6% in patients given ticagrelor and 47.6% in those assigned to clopidogrel.

The study was investigator initiated and funded by an unrestricted research grant from AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESOC 2023

Alcohol may curb stress signaling in brain to protect heart

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

The cardiopulmonary effects of mask wearing

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

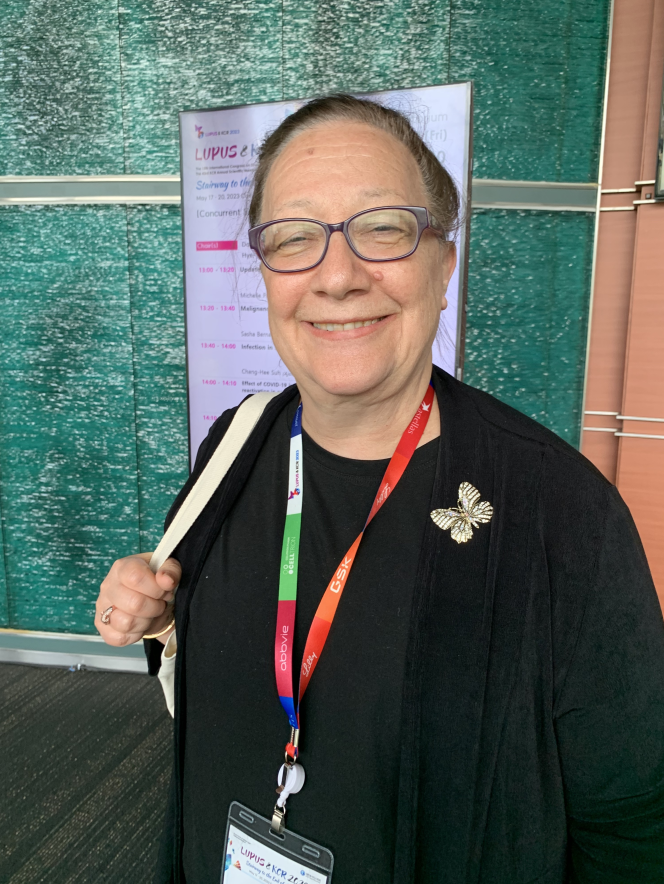

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

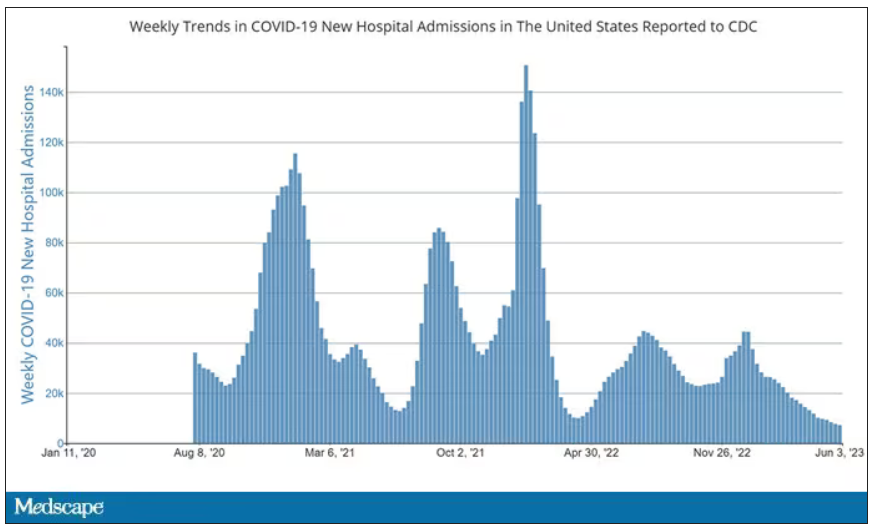

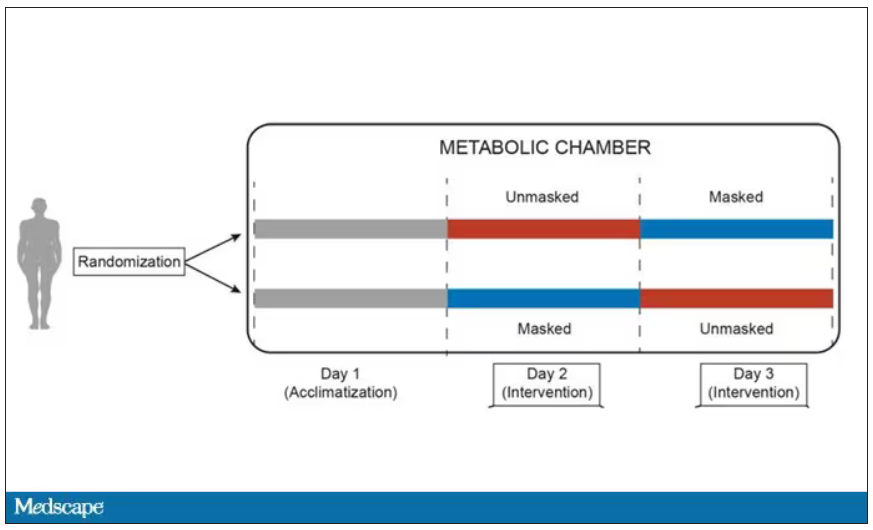

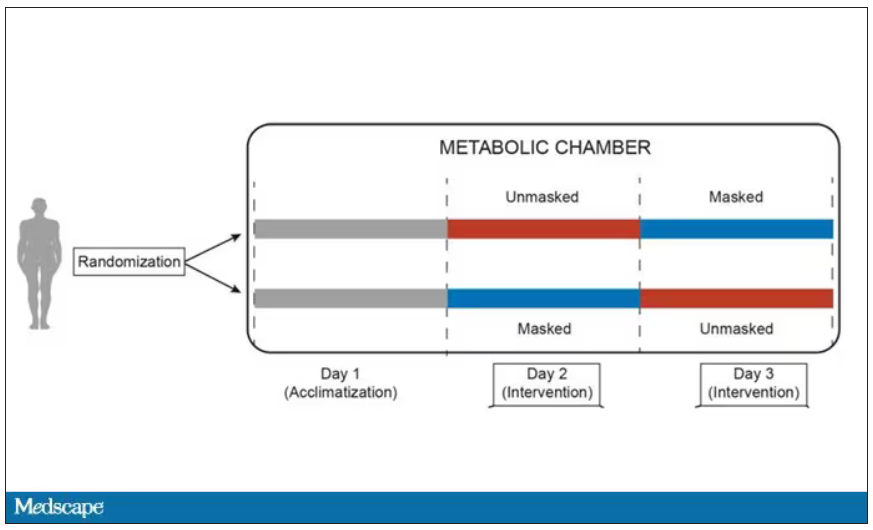

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

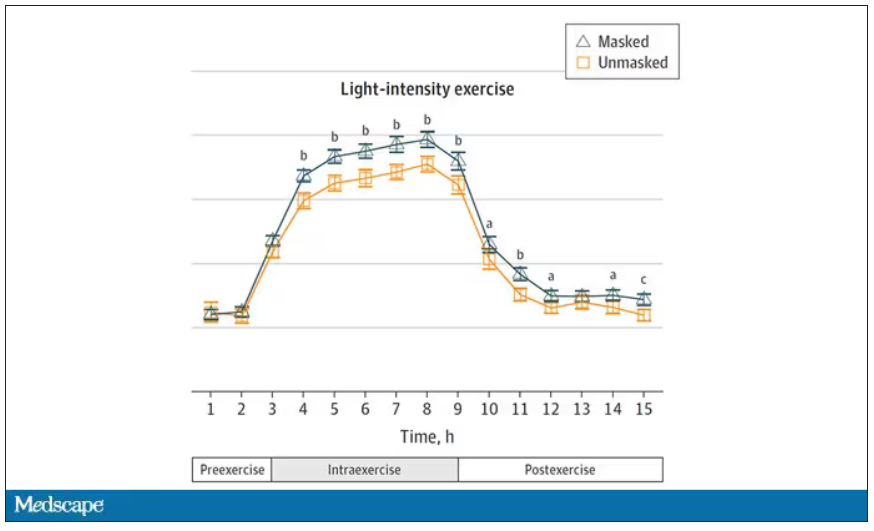

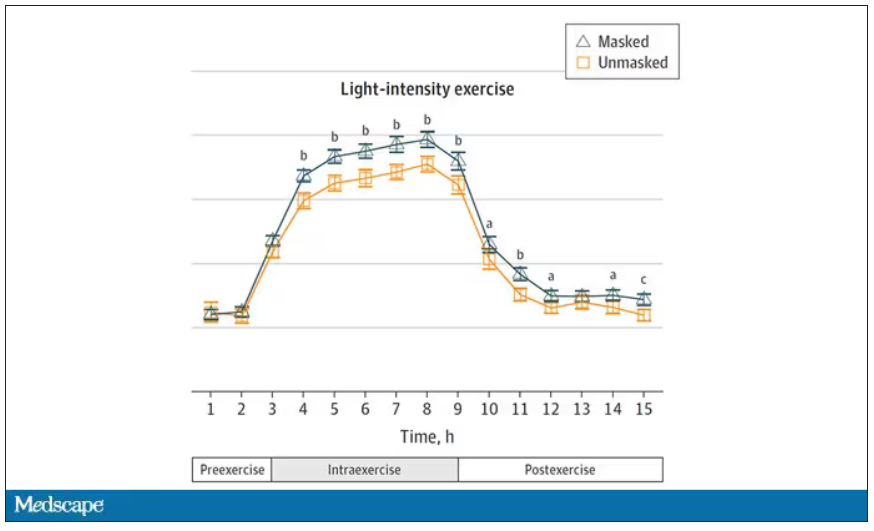

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

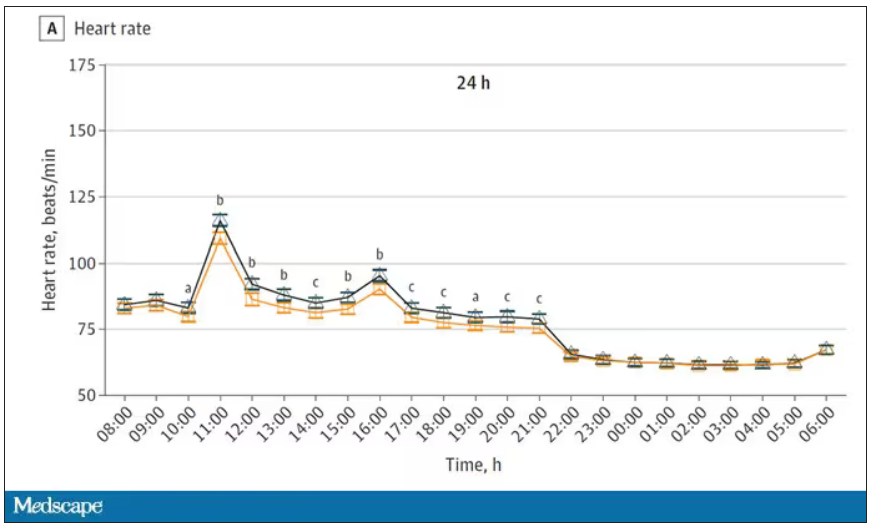

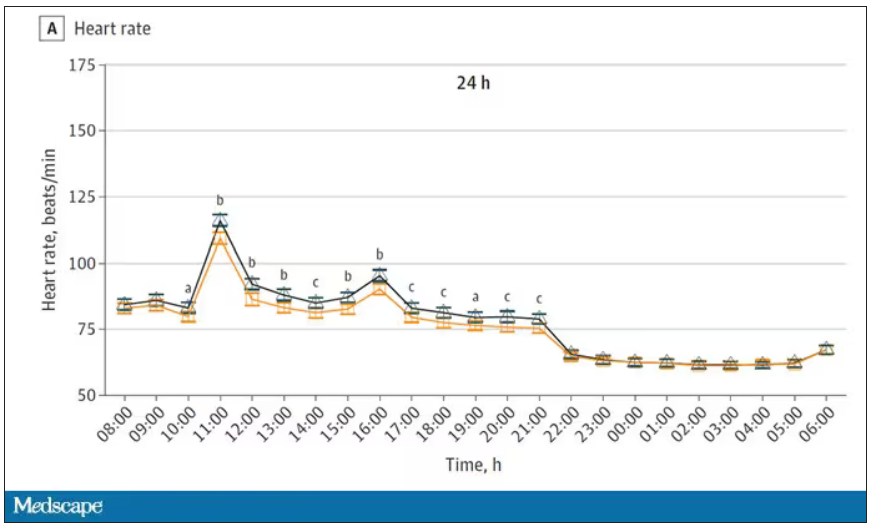

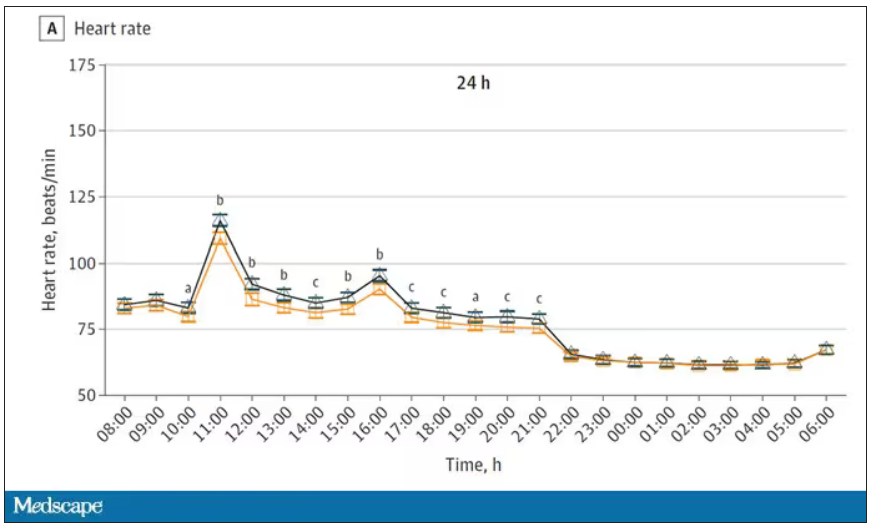

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

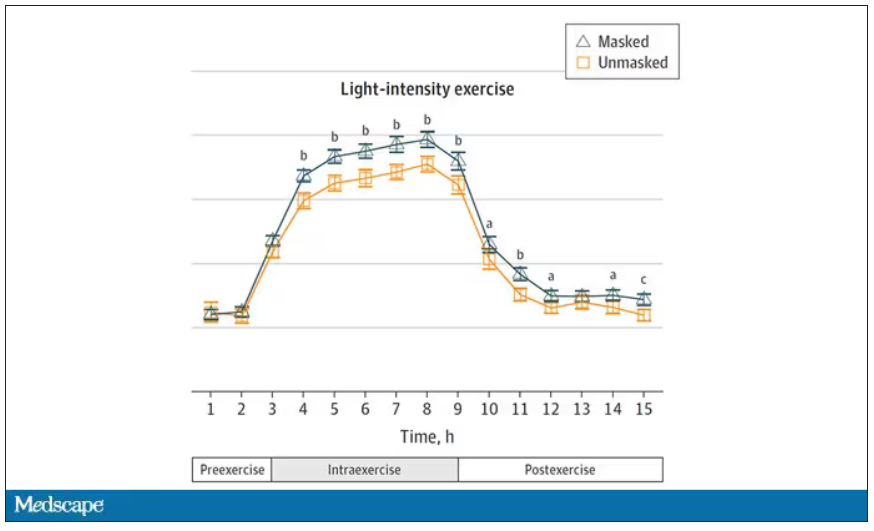

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insurers poised to crack down on off-label Ozempic prescriptions

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Popular weight loss drugs can carry some unpleasant side effects

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

PTSD: Children, adolescents, and all of us may be at risk

Not everyone will suffer an episode of posttraumatic stress disorder, even though everyday American life is characterized by a lot of uncertainty these days, particularly considering the proliferation of gun violence.

Also, everyone who does experience a traumatic event will not suffer an episode of PTSD – just as not everyone develops a heart attack or cancer, nor will everyone get every illness.

The data suggest that of those exposed to trauma, up to 25% of people will develop PTSD, according to Massachusetts General/McLean Hospital, Belmont, psychiatrist Kerry J. Ressler, MD, PhD, chief of the division of depression and anxiety disorders.

As I wrote in December 2022, our “kids” are not all right and psychiatry can help. I would say that many adolescents, and adults as well, may not be all right as we are terrorized not only by mass school shootings, but shootings happening almost anywhere and everywhere in our country: in supermarkets, hospitals, and shopping malls, at graduation parties, and on the streets.

According to a report published in Clinical Psychiatry News, a poll conducted by the American Psychiatric Association showed that most American adults [70%] reported that they were anxious or extremely anxious about keeping themselves or their families safe. APA President Rebecca W. Brendel, MD, JD, pointed out that there is “a lot of worry out there about economic uncertainty, about violence and how we are going to come out of this time period.”

Meanwhile, PTSD is still defined in the DSM-5 as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence experienced directly, witnessing the traumatic event as it occurs to others, learning that a traumatic event occurred to a close family member or friend, or experiencing of traumatic events plus extreme exposure to aversive details of the event.